Abstract

Psychological variables are a key component of the general outcome of students. In this sense, their complementary role in the academic lives of students is not doubtful. Therefore, this study examined the interrelationship among curiosity, creativity, and academic motivation of students in high school. A total of 568 students were surveyed using the correlational design (purposive, simple random, stratified-proportionate, and systematic sampling techniques). Adapted and confirmed curiosity, creativity, and academic motivation scales were used to gather the data for the study. Multiple linear regression was used to test the interrelationships. The study found that curiosity, creativity, and academic motivation predicted among themselves, where curiosity predicted higher, followed by creativity, and academic motivation. In this, curious behaviours, creative abilities, and motivation of students are related. It is recommended among others that the Ghana Education Service, in collaboration with the Ministry of Education and Curriculum Developers, should harmonise curiosity, creativity, and motivation in the High School syllabus so that teachers can guide students to become curious, creative, and motivated.

1 Introduction

Learning requires curiosity, creativity, and motivation on the part of students. Surprisingly, curiosity, creativity, and motivation are not only a feature of students’ learning but also parts of the instructional practices of teachers in the learning environment. By nature, students are curious and through curiosity, students can be creative and become motivated in learning situations. According to Kashdan and Silvia (2009), curiosity is the appreciation, quest, and strong need to discover unique, stimulating, and undefined situations. When people become curious, they become conscious and approach situations with zeal and might engage in their current phenomenon. Curiosity as a psychological construct has an internal underpinning but manifested externally by people. The internal nature of curiosity becomes evident when the innate push makes visible signs of exploration in people (e.g., performance). Curiosity is an indispensable construct in teaching and learning. For instance, Coleman (2014), Litman and Jimerson (2004), and Pekrun (2019, 2011) indicated that curiosity allows students to own their expeditions, which closely correlates with the magnitude and worth of their learning processes.

Creativity is noted to be a psychological construct, which is a pathway of inheritances that regulate progress, opens human competence, and allows it to succeed (Alfuhaigi, 2015). Creativity, according to Dineen, Samuel, and Livesey (2005), is a process of generating a consequence that is innovative or unique and applicable or appreciated. Hoffman and Holzhuter (2012) posited that creativity looks like a modification, where organisms advance to strive for sustenance. It has been argued that when institutions accept, encourage, and support creativity with a course of action, it may serve as a response to employment-related problems and the struggle for superiority (Lucas, Claxton, & Spencer, 2013). This argument suggests that for an individual, a nation, and humankind to survive and progress, the growth of creativity is indispensable. According to Serdyukov (2017), the call for educational creativity has developed tremendously because many countries hold the view that social and economic well-being depends on the extent of quality education among their citizens. McWilliam (2007) noted that the current mainstream teaching methodological practices in education focus on retrieving information and exhausting them in explaining expected difficulties or comprehensive foreseeable and repetitive relations of one kind absorbed, instead of understanding the areas of concern in education. This development remains for more than a decade despite the narrow lifespan of disciplinary knowledge.

Motivation as a hypothetical construct is used to describe the start, path, force, and persistence of behaviour, especially goal-directed behaviour (Maehr & Meyer as cited in Dramanu & Mohammed, 2017). Likewise, in the classroom situation, motivation is used to elucidate the degree to which students devote attention and effort to various pursuits that may or may not be the ones desired by teachers (Brophy as cited in Dramanu & Mohammed, 2017). Researchers such as Bandalos, Geske, and Finney (2003), Chemers, Hu, and Garcia (2001), and Senko and Harackiewicz (2005) argued that students’ desired goals, concern for subjects, and feat prospects as components of motivation that are linked to students’ academic performance. According to Sharma and Sharma (2018), motivation is about engagements, wishes, and desires because it helps in directing behaviour towards a goal. Academically, motivation concerns itself with the process towards achievement rather than the results. In explaining the value of motivation in education, Adamma, Ekwutosim, and Unamba (2018), Elliot and Dweck (2005), and Muola (2010) indicated that nurturing learning and maintaining motivation among students should be a prime area for every teacher because it is an integral part in the overall performance of students. Akhtar, Iqbal, and Tatlah (2017) indicated that motivated students are those who take charge of knowledge development and serve as the fulcrum through which learning is enhanced. Students’ urge to learn is possible due to how motivated they are, as this becomes an aspirational push for academic excellence (Gupta & Mili, 2016).

In exploring constellation factors of success in learning situations, it is clear that curiosity, creativity, and motivation are complementary in nature and bring to bear positive learning outcomes among students. These factors are argued to bring about high imagination and novel outcomes among learners. For instance, Akhtar, Tatlah, and Iqbal (2018) alleged that curious, creative, and motivated students are those who perform better academically. According to Sansone and Smith (2000), as students’ become curious, creative, and motivated, they pay more attention to the learning process, exert a deeper level of understanding, retain information better, and can persevere in diverse learning tasks until the goals they set are met.

A sense of curiosity has been suggested as a necessary but not sufficient condition for creativity, in that, curiosity may enhance the desire to engage in creative behaviours but creativity cannot be more visible in learners than a sense of curiosity (Collins, Litman, & Spielberger, 2004). Recently, it has been discovered that curiosity has an impact on the generation stage of the creative process (Harrison & Dossinger, 2017). Researchers appear to establish a positive link between curiosity and intrinsic motivation (Hong-Keung, Man-Shan, & Lai-Fong, 2012). For example, Litman (2005) and Shroff, Vogel, and Coombes (2008) revealed that curiosity was positively related to intrinsic motivation. In this regard, curiosity can be labelled as a driving force behind the desire to explore and engage with new ideas or challenges. When students become curious, they are naturally more inclined to invest time and effort in an activity. In the context of creativity, this could mean that curious students are more likely to persist in the face of challenges, explore different avenues, and derive satisfaction from the act of generating ideas itself. This intrinsic motivation, fuelled by curiosity could lead to a more productive and innovative generation stage in the creative process. The findings of Hon-Keung et al. (2012) study were similar to a study conducted in Shiraz by Zare, Jamshidi, Rastegar, and Jahromi (2011) concerning the relationship between creativity and achievement motivation in entrepreneurship. The study revealed that a significant positive relationship existed between creativity and achievement motivation. The findings further showed that creativity predicted 93% of the variance of achievement-motivation in entrepreneurship of high school students in Shiraz.

Ainley, Hidi, and Berndorff (2002) noted that curiosity and creativity have been established to inspire learners and eventually result in better academic performance. Durik and Harackiewicz (2007) found a positive relationship between curiosity, creativity, and motivational concepts such as engagement, perceived competence, and cognitive processing. Shin and Kim (2019) indicated that the link between curiosity and creativity has long been acknowledged. For instance, Day and Langevin (as cited in Shin & Kim, 2019) projected that curiosity and intelligence power creativity, and Maw and Maw (as cited in Shin & Kim, 2019) similarly established that there exists a significant relationship between curiosity and creativity among students. Shin and Kim (2019) explained that highly curious students exhibit adaptive and creative thinking abilities than those who are less curious. By exploring the role of curiosity in creative abilities of students, Karwowski (2012) study revealed a strong association between curiosity and creativity. Assertions and empirical evidence presented by Shin and Kim (2019) buttressed the findings of Kashdan and Fincham (2002). In their efficient examination of curiosity’s role in developing creative mental processes, creative personalities, and the production of creative works, Kashdan and Fincham (2002) noted that there was an urgent need to provoke and nurture curiosity in students because it could propel them to greater heights in their scholastic endeavours. In a similar manner, the study was conducted among 480 participants, and the results indicated that individual work-related curiosity was a positive predictor of worker creativity in terms of innovation and that creative divergent thinking mediated this relationship (Celik, Storme, Davila, & Myszkowski, 2016).

1.1 The Present Study

Extant literature shows that curious abilities of people are favourable for their creative ideas and motivation to engage in a purposeful activity (Dahmen-Wassenberg, Kämmerle, Unterrainer, & Fink, 2016; Ding, Tang, Deng, Tang, & Posner, Tang, 2015; Horng, Tsai, Yang, & Liu, 2016). According to Ivcevic and Brackett (2015), Van Tilburg, Sedikides, and Wildschut (2015), curious behaviours of students influence their creative and motivational reactions and performance in many academic fields. These views are supported by other scholarly positions. For example, curiosity, creativity, and motivation are noted to be intertwined (Batey, Furnham, & Safiullina, 2010; Grosul & Feist, 2014; Jauk, Benedek, & Neubauer, 2014; Silvia et al., 2014; Zhang & Bartol, 2010). The dynamic interplay among curiosity, creativity, and motivation has captivated the attention of researchers and educators alike. These psychological constructs wield substantial influence over human behaviour, particularly within the realm of learning and academic achievement. Silvia et al. (2014) orchestrated an intricate research design meticulously structured to unearth the multifaceted connections between curiosity, creativity, and motivation. In this study, they found curiosity, creativity, and motivation related as curiosity predicted strongly on creativity-related activities of students (Silvia et al., 2014). The findings corroborated with Tan, Lau, Kung, and Kailsan (2019) study’s finding, as they opined that curious students are inspired and are inclined to creative actions. The preceding evidence indicate that creative production requires a high level of motivation, while several theories show that creative persons engage in tasks when they feel they are satisfying and enjoyable. Therefore, students can exert their creative potentials only when they are curious and motivated.

It is worthy of note that the interplay among curiosity, creativity, and academic motivation in high school students is a multifaceted and dynamic area of research that holds significant implications for educational psychology and student success. While existing literature has explored each of these constructs individually, there is a notable gap in understanding the intricate interrelationships among them. Addressing this gap and conducting comprehensive research in this area is crucial for several reasons. With respect to research focus, previous research has primarily focused on studying curiosity, creativity, and academic motivation in isolation, lacking a cohesive framework that comprehensively examines how these factors interact and influence each other. A deeper exploration is required to unravel the complex ways in which curiosity fuels creativity and how both impact academic motivation and vice versa. In establishing causal relationships, the existing literature often lacks a clear understanding of the causal relationships among curiosity, creativity, and academic motivation. While some studies suggest that curiosity and creativity drive academic motivation, others propose reverse or bidirectional causality. Unraveling the causal pathways can provide valuable insights into designing effective interventions to enhance student engagement and performance. Developmentally, there is a scarcity of research exploring how the interplay between these constructs evolves over time during high school years. Adolescence is a period of significant cognitive and emotional development, making it crucial to investigate how curiosity, creativity, and academic motivation change and interact throughout this period. Contextually, most research has been conducted within specific cultural and contextual settings, limiting the generalisability of findings. Exploring these interrelationships across diverse, high school populations and educational systems can shed light on potential cultural variations and inform more inclusive educational practices. Therefore, the need to investigate interrelationships among these variables using students in High Schools in the Central Region of Ghana. Based on the over-arching purpose, the study was guided by a multi-focus research hypothesis.

There will be predictions among (a) curiosity, (b) creativity, and (c) motivation of students in High Schools.

2 Methods

2.1 Research Design, Sampling, and Participants

As an extraction from a larger study, the correlational research design was employed. The design was appropriate for this study because it enabled relationships to be established between or among variables without determining the cause and effect of those related variables. The population for the study comprised two high school students of 25 schools with a total of 32,233. The population comprised students in mixed and single sex schools with an average age of 16 years. Curiosity, creativity, and motivation are major parts of a child’s developmental process. In this regard, the use of high school students for this study is justified. For example, Lyons and Beilock (2011), indicated that students habitually express emotions and inspirations towards their learning; hence, they are well-thought-out to understand curiosity, creativity, and motivation as potentials for effective learning and performance. The sample size for the study was 568 (female = 288 [50.7%] while male = 280 [49.3%]) respondents based on Gay, Mills, and Airasian’s (2012) suggestion that a population greater than 5,000 must have at least 400 respondents as a sample. The average age of the students was 16.80 ± 0.98. The sample was appropriate for the study because it exceeded the minimum sample size of 30 respondents for correlational research as suggested by Gay et al. (2012) and equally met the criterion that 30 and above sample size was good for quantitative studies (Boddy, 2016). The selection of respondents was based on a multiple sampling approach, where purposive sampling procedure, simple random sampling (lottery method with replacement), stratified-proportionate sampling procedure, and systematic sampling procedure were applied.

2.2 Instrumentation and Analysis

The curious abilities of the students were measured with an adapted scale named 5-Dimensions of Curiosity (5DC) with a composite reliability coefficient of 0.71 (Kashdan et al., 2018). Also, the creative abilities of students were assessed with an adapted scale named Kaufman Domains of Creativity Scale (K-DOCS) with a composite reliability coefficient of 0.86 (Kaufman, 2012). Academic motivation of students was determined with an adapted scale named Academic Motivation Scale (AMS-28) with a composite reliability coefficient of 0.79 (Vallerand et al., 1992). Table 1 shows the adapted scales, their dimensions, and reliability coefficients.

Internal consistencies for (reliability) the adapted scales

| Construct | Pilot-testing of data results | Final data collection results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Items | Reliability | Items | Reliability |

| Curiosity | 25 | 0.842 | 25 | 0.764 |

| Joyous exploration | 5 | 0.834 | 5 | 0.770 |

| Deprivation sensitivity | 5 | 0.815 | 5 | 0.731 |

| Stress tolerance | 5 | 0.904 | 5 | 0.854 |

| Social curiosity | 5 | 0.829 | 5 | 0.724 |

| Thrill seeking | 5 | 0.830 | 5 | 0.740 |

| Creativity | 50 | 0.817 | 49 | 0.786 |

| Everyday creativity | 11 | 0.815 | 11 | 0.758 |

| Scholarly creativity | 10 | 0.817 | 10 | 0.793 |

| Performance creativity | 9 | 0.804 | 9 | 0.765 |

| Mechanical/science creativity | 10 | 0.826 | 10 | 0.789 |

| Artistic creativity | 10 | 0.822 | 9 | 0.824 |

| Motivation | 28 | 0.828 | 28 | 0.822 |

| Intrinsic motivation knowledge | 4 | 0.810 | 4 | 0.830 |

| Intrinsic motivation accomplishment | 4 | 0.819 | 4 | 0.818 |

| Intrinsic motivation stimulation | 4 | 0.822 | 4 | 0.827 |

| Extrinsic motivation identified regulation | 4 | 0.807 | 4 | 0.824 |

| Extrinsic motivation introjected regulation | 4 | 0.829 | 4 | 0.717 |

| Extrinsic motivation extrinsic | 4 | 0.826 | 4 | 0.839 |

| Amotivation | 4 | 0.876 | 4 | 0.900 |

Bold figures indicate total number of statements under each construct and composite scores of internal consistencies/reliability values.

After satisfying this process, it was prudent to further test the assumptions appropriately using descriptive statistics before running the individual tests for the research questions and hypotheses. This included the skewness of data, kurtosis data, means, and standard deviations of the variables used in the study. Table 2 presents the results.

Descriptive statistics for all the scales

| Measures | N | Min. | Max. | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stat. | Stat. | Stat. | Stat. | Stat. | Stat. | Std. E | Stat. | Std. E | |

| Curiosity total | 568 | 51.00 | 90.00 | 71.54 | 7.30 | −0.255 | 0.103 | −0.098 | 0.205 |

| Creativity total | 568 | 92.00 | 200.00 | 143.75 | 16.50 | 0.209 | 0.103 | 0.438 | 0.205 |

| Motivation total | 568 | 51.00 | 112.00 | 86.31 | 9.11 | −0.654 | 0.103 | 0.483 | 0.205 |

Table 2 indicates the skewness of data based on custom rule values ranged between +1 and −1 and kurtosis custom rule values ranged between +1 and −1. Referring to curiosity, it produced a skewness statistic of −0.255 and a kurtosis statistic of −0.098. This implies that the distribution for curiosity was skewed to the left while kurtosis produced a negative value, making the data leptokurtic (negative kurtosis shows a distribution that does not peak and has lighter tails). This explained that the majority of responses or cases are falling above the average/midpoint in the normal curve (mean and median less than the mode). Referring to creativity, it produced a skewness statistic of 0.209 and a kurtosis statistic of 0.438. This implied that the distribution for creativity was skewed to the right while kurtosis produced a positive value, making it platykurtic kurtosis (positive kurtosis shows a distribution that is peaked and possessed thick tails). This explained that the majority of responses or cases are falling below the average/midpoint in the normal curve (mean and median greater than the mode). Referring to motivation, it produced a skewness statistic of −0.654 and a kurtosis statistic of 0.483. This implied that the distribution for motivation was skewed to the left while kurtosis showed a positive value, making the data leptokurtic (a negative kurtosis value indicates that the distribution has lighter tails than the normal distribution). This explained that the majority of responses or cases are falling above the average/midpoint in the normal curve (mean and median less than the mode). As Hair, Hult, Ringle, Sarstedt, and Thiele (2017) indicate, if the distribution of responses for a variable stretches towards the right or left tail of the distribution, then the distribution is referred to as skewed while kurtosis measures the extent to which the distribution becomes too peaked or light at the tail of the distribution. A custom rule for skewness says that if the number is greater than +1 or less than −1, it shows a considerably skewed distribution. For kurtosis, the custom rule says that if the number is greater than +1, the distribution is too peaked. Likewise, a kurtosis of less than −1 indicates a distribution that is too flat (Hair et al., 2017).

2.3 Data Analysis Procedure

Multivariate regression was employed to investigate the relationships among curiosity, creativity, and motivation. The choice of this tool accounted for the potential effects of the multiple predictors simultaneously. Again, the choice of multivariate regression analysis in this study was both strategic and methodologically robust because the researchers explored how variations in curiosity scores predict not only variations in creativity but also account for the potential influence of motivation. In this sense, creativity was paired with curiosity; curiosity was paired with motivation; and motivation was paired with creativity. With this, each variable served both as a predictor and a criterion.

3 Results

3.1 Research Hypothesis 1: There will be Predictions Among (a) Curiosity, (b) Creativity, and (c) Motivation of Students in High Schools

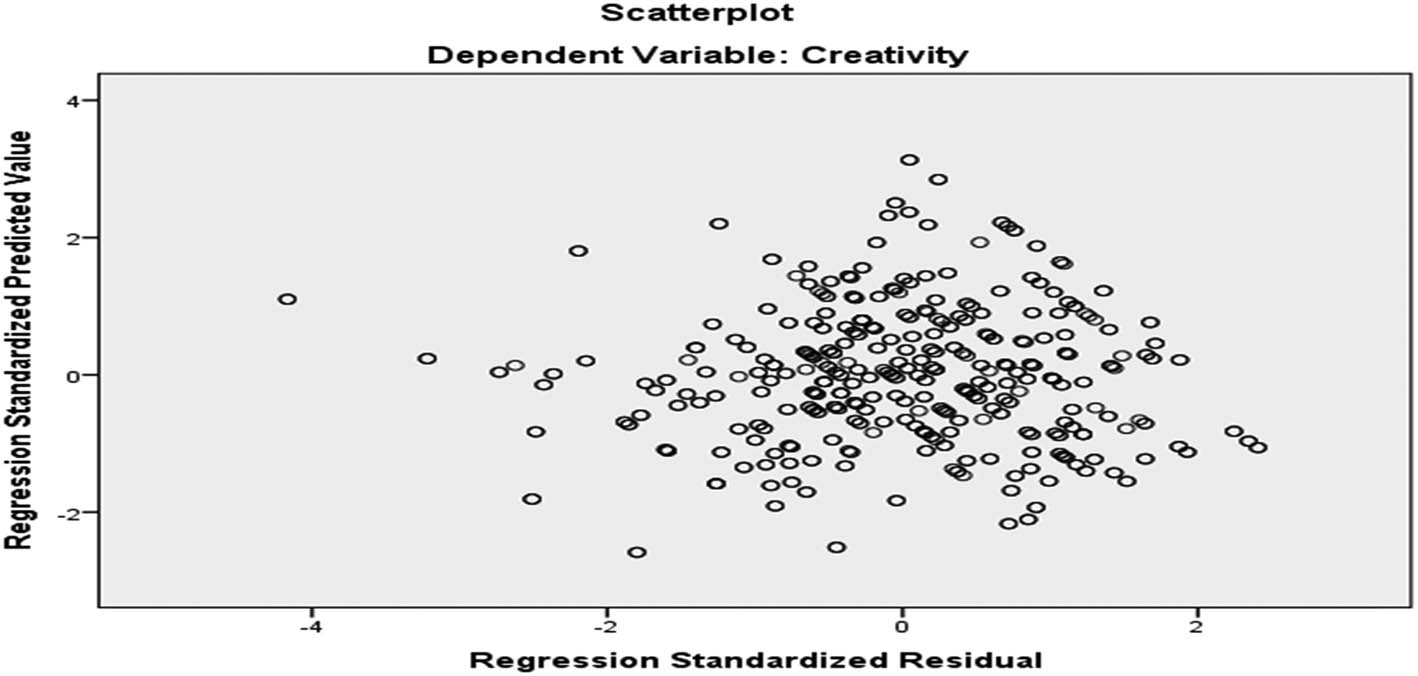

The objective of testing this hypothesis was to establish a non-recursive statistical relationship among (a) curiosity, (b) creativity, and (c) motivation using regression. Multivariate regression was used for the prediction because it has the power to produce correlations and predictions among the variables, where each variable predicts the other. Before performing the regression test, the normality test, linearity, homoscedasticity, multicollinearity, and collinearity assumptions were certified as preliminary tests.

From Table 3, concerning the multicollinearity and collinearity assumption test, correlation coefficients of 0.385–0.546 were produced, while collinearity statistics produced variance inflation factors (VIFs) between 1 and 10 for all variable pairings, and this signifies that there were fewer issues regarding collinearity and multicollinearity (Pallant, 2016). After satisfying the assumptions, the regression test results are presented in Table 4.

Multicollinearity and collinearity assumptions for curiosity, creativity, and motivation

| Variable | Collinearity statistics | |

|---|---|---|

| First test | Tolerance | Variance inflation factor |

| Curiosity | 0.770 | 1.299 |

| Creativity | 0.770 | 1.299 |

| Second test | Tolerance | Variance inflation factor |

| Curiosity | 0.677 | 1.477 |

| Motivation | 0.677 | 1.477 |

| Third test | Tolerance | Variance inflation factor |

| Creativity | 0.634 | 1.575 |

| Motivation | 0.634 | 1.575 |

First dependent = motivation; Second dependent = Creativity; Third dependent = Curiosity.

Regression results on curiosity, creativity, and motivation pairings

| Variable | B | SE | β | R | T | R 2 | AdR 2 | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First pairing test | |||||||||

| Creativity | 0.218 | 0.048 | 0.199 | 0.385 | 4.51 | 0.230 | 0.227 | 84.45 | 0.000 |

| Curiosity | 0.315 | 0.041 | 0.341 | 0.450 | 7.45 | 0.230 | 0.227 | 84.45 | 0.000 |

| Second pairing test | |||||||||

| Curiosity | 0.393 | 0.033 | 0.468 | 0.546 | 13.1 | 0.323 | 0.320 | 134.6 | 0.000 |

| Motivation | 0.159 | 0.035 | 0.175 | 0.385 | 4.51 | 0.323 | 0.320 | 134.6 | 0.000 |

| Third pairing test | |||||||||

| Motivation | 0.305 | 0.039 | 0.281 | 0.450 | 7.75 | 0.366 | 0.363 | 162.9 | 0.000 |

| Creativity | 0.520 | 0.043 | 0.438 | 0.546 | 12.1 | 0.366 | 0.363 | 162.9 | 0.000 |

*First dependent = Motivation; *Second dependent = Creativity; *Third dependent = Curiosity.

Table 4 indicates the results of the regression analysis of curiosity, creativity, and motivation pairings. In the first pairing of curiosity and creativity as predictors of motivation, the results show that there were moderate positive relationships between students’ creativity and motivation (r = 0.385) and students’ curiosity and motivation (r = 0.450). The results of the regression indicated that students’ creativity and curiosity explained 23.0% of the variance in their motivation (R 2 = 0.230, F (2, 565) = 84.45, p < 0.000). It was found that students’ creativity significantly predicted students’ motivation (β = 0.199, p < 0.000), and students’ curiosity significantly predicted students’ motivation (β = 0.341, p < 0.000). Looking at these findings, it was evident that students’ curiosity predicted their motivation more than students’ creativity. The results imply that a unit increase in either students’ curiosity or creativity will lead to an increase in their motivation, but this increase will be more for curiosity against motivation than creativity against motivation. For the effect size contribution of students’ creativity and curiosity to their motivation, the results revealed an effect size of 0.30, which was moderate using Cohen’s (1988) formula. For example, f 2 = R 2/1 – R 2 = 0.230/1 – 0.230 = 0.230/0.77 = 0.30. These imply that the strength of the relationship among students’ curiosity, creativity, and motivation was average.

In the second pairing of curiosity and motivation as predictors of creativity, the results show that there were moderate positive relationships between students’ curiosity and creativity (r = 0.546) and students’ motivation and creativity (r = 0.385). The results of the regression indicated that students’ curiosity and motivation explained 32.3% of the variance in their creativity (R 2 = 0.323, F (2, 565) = 134.61, p < 0.000). It was found that students’ curiosity significantly predicted students’ creativity (β = 0.468, p < 0.000), and students’ motivation significantly predicted students’ creativity (β = 0.175, p < 0.000). Looking at these findings, it was evident that students’ curiosity predicted their creativity more than students’ motivation. The results mean that a unit increase in either students’ curiosity or motivation will lead to an increase in their creativity, but this increase will be more for curiosity against creativity than motivation against creativity. For the effect size contribution of students’ curiosity and motivation to their creativity, the results revealed an effect size of 0.48, which was large using Cohen’s (1988) formula. For example, f 2 = R 2/1 – R 2 = 0.323/1 – 0.323 = 0.323/0.68 = 0.48. These imply that the strength of the relationship among students’ curiosity, motivation, and creativity was high.

In the third pairing of creativity and motivation as predictors of curiosity, the results show that there was a moderate positive relationship between students’ creativity and curiosity (r = 0.546) and students’ motivation and curiosity (r = 0.450). The results of the regression indicated that students’ creativity and motivation explained 36.6% of the variance in their curiosity (R 2 = 0.366, F (2, 565) = 162.89, p < 0.000). It was found that students’ creativity significantly predicted students’ curiosity (β = 0.438, p < 0.000), and students’ motivation significantly predicted students’ curiosity (β = 0.281, p < 0.000). Based on these findings, it was evident that students’ creativity predicted their curiosity more than students’ motivation. The results mean that a unit increase in students’ creativity or motivation will lead to an increase in their curiosity, but this increase will be more for creativity against curiosity than motivation against curiosity. For the effect size contribution of students’ curiosity and motivation to their creativity, the results revealed an effect size of 0.58, which was large using Cohen’s (1988) formula. For example, f 2 = R 2/1 – R 2 = 0.366/1 – 0.366 = 0.366/0.63 = 0.58. These imply that the strength of the relationship among students’ curiosity, motivation, and creativity was high. The findings are presented with a conceptual model in Figure 1.

Curiosity, creativity, and motivation model.

Figure 1 indicates the predictive ability among the latent constructs. It revealed that curiosity predicted better on creativity and motivation. It means that curiosity can propel students to become creative and motivated in school work. The implication is that curiosity is an important component of students’ academic lives as it could invoke their ability to become creative and motivated in their academic work.

4 Discussion

The hypothesis aimed at testing the predictive abilities among curiosity, creativity, and motivation as innate potentials of students. In the testing process, curiosity and creativity were paired against motivation (test 1), curiosity and motivation were paired against creativity (test 2), and creativity and motivation were paired against curiosity. In test 1, the study revealed that curiosity predicted motivation better than creativity. This suggests that curious ability in students can lead them to become more motivated than their creative ability. Presumably, nurturing curiosity among students will help them to become motivated in their academic pursuits because the more curious they are, the more motivated they become. This finding suggests that curiosity is a major aspect of students’ success. When students are presented with the opportunity to investigate their environment through teachers’ guide, they are likely to uncover the knowledge that was hidden and use such knowledge for their academic and social lives.

With creativity and its prediction on motivation, students can be inspired by their creative products (innovation). Once they are able to produce novel things, the tendency for them to be motivated to pursue other areas of their academic work would be high. Both curiosity and creativity finding produced a moderate effect size for motivation. This confirms the assertion that curiosity and creativity work directly or indirectly to motivate students in academic surroundings (Shin & Kim, 2019). Also, the finding buttresses the view by Ainley et al. (2002) that curiosity and creativity inspire learners to perform better academically. With this effect size, it means that the relationship between creativity and motivation was never low nor high but appreciable (Cohen, 1988).

In the second test, the study revealed that curiosity significantly predicted students’ creativity and students’ motivation significantly predicted students’ creativity; however, curiosity was a better predictor of creativity than motivation. This means that as students become curious, they are likely to become creative and eventually become innovative than they become motivated. Unsurprisingly, students’ quest for knowledge is a natural and necessary condition for success. So, when students are given the opportunity to explore or investigate their academic environments purposely, it will help them to be creative way, where they could come up with novel products. Comparing the roles of curiosity and motivation in the creative abilities of students, curiosity is a major construct to be considered more than motivation because motivation can only be realised after students’ purposeful exploration produces creative behaviours that may be appreciated by students themselves or their teachers. Both curiosity and motivation produced a large effect size. With this effect size, it means that the relationship was strong. The finding of the current study supports the finding of a study conducted by Collins et al. (2004). In this study, creative behaviours and creative personality qualities were found to be associated with both forms of curiosity. A sense of curiosity has been suggested as a necessary but not sufficient condition for creativity in that curiosity may enhance the desire to engage in creative behaviours, but creativity cannot be more visible in learners than a sense of curiosity (Collins et al., 2004). Also, the finding of the current study confirms the finding of a study conducted by Celik et al. (2016). In this study, the researchers found that there was a correlation between curiosity and creativity exhibited by students.

In the third test, the study revealed that students’ creativity significantly predicted their curiosity and motivation, where creativity was a better predictor of curious abilities than students’ motivation. Presumably, it means that creativity can influence curiosity and as well motivation. Among students, it is possible that students’ ability to come up with new ideas that are helpful in their academic environment could improve upon their quest to search for new ideas. Again, students who are inspired from within or external sources are likely to engage in purposeful explorative behaviours, which may in turn help in their academic pursuits. It is important to note that both creativity and motivation have various roles to play in students’ quest to search for knowledge. However, such roles vary based on the immediate mental state of students. At a time where creativity is present, they may engage in curious behaviours more often, while at a time where motivation is present, they may engage in curious behaviours but less than when creativity was present. The finding of the current study confirmed the findings of Litman (2005) and Shroff et al. (2008). In their studies, students’ curiosity significantly predicted their motivation positively. Furthermore, the finding of the current study confirmed the findings of Hon-Keung et al. (2012). They found significant and positive predictions between curiosity and motivation of students, where higher levels of curiosity related positively to higher levels of motivation. Also, the finding of the current study confirmed the findings of Shin and Kim (2019), as they found highly curious students exhibiting creative thinking abilities, implying that curiosity predicts creativity in students. Furthermore, the finding supports that of Karwowski’s (2012), which revealed a strong positive relationship between curiosity and creativity: curiosity significantly predicted creativity among students. More so, the finding of the current study corroborates the findings of Kashdan and Fincham (2002), where they established that curiosity positively predicts creativity, where the nurturing curiosity in students could propel them to become creative in their lives. Again, the finding of the current study was congruent with the finding of Zare et al. (2011). They found that creativity positively and significantly predicted students’ achievement: creativity predicted 93% of the variance of achievement-motivation.

5 Conclusion

Students’ curious behaviours, creative abilities, and motivational orientations are related and complement one another in pursuit of academic goals, as revealed by the current study. The direction of the findings has created a platform for the paradigm. In this, the traditional studies that have often focused on exploring curiosity, creativity, and motivation as discrete entities, each offering valuable insights into students’ cognitive and affective dimensions, have been debunked for a good reason. While these studies have provided valuable foundational knowledge, they paint an incomplete picture of the complex dynamics at play within the educational landscape. The recent findings that students’ curious behaviours, creative abilities, and motivational orientations are interrelated and synergistically contribute to their academic endeavours mark a paradigm shift in how we perceive and investigate these constructs.

As students become curious, their creative abilities are energised, and they become motivated when creative products are realised. For this reason, it is important that their students’ curiosity is provoked; at the same time, their creative abilities are honed while their efforts are being reinforced so that they can achieve success in learning endeavours. Specifically, teachers and parents need to find appropriate pedagogical strategies that give room for students’ explorative behaviours to be exhibited, where students could be engaged in independent activities to realise their creativity and making an effort to reward the successes of the students in the process of acquiring knowledge.

6 Implication for Policy and Practice

It is recommended that organisations responsible for educational development collaborate with curriculum developers so that latent learner skills such as curiosity, creativity, and motivation can be harmonised with the required syllabus. In this direction, teachers can guide students to become curious, creative, and motivated in their learning expeditions without necessarily teaching the concepts to students as separate subject areas. Again, training programmes for in-service teachers and trainee teachers should be geared towards the inclusion of curiosity, creativity, and motivation to make it comprehensive for teachers as they engage students in teaching and learning activities in future. With this, teachers can become curious behaviours of their students through open-ended discussions that allow students to share their wonderings and curiosities, promoting a culture of inquiry in the classroom, develop their creative potential through project works where they choose an aspect of a subject that interests them, and inspire them by providing opportunities for self-assessment and reflection, allowing students to track their progress and celebrate milestones.

Furthermore, management of high schools should make efforts to develop holistic students to become more curious, creative, and motivated in pursuit of their academic goals. As psychologically oriented abilities, students need to be taught by their teachers how to improve their concentration; they should be allowed enough sleep to improve memory retention, taught how to be self-disciplined, encourage exercise, engage students in active learning, and teach meditation so that their general mental system can be enhanced. Also, schools can help develop students’ abilities in curiosity, creativity, and motivation by giving them less non-academic activities after school so that their minds can be engaged. Students on their part can be asked to engage in mental and physical exercises as these can help make every part of their brains active. Exercises allow the free flow of oxygen to vital parts of the brain and contribute to the improvement of cognitive skills, which are responsible for curiosity, creativity, and motivation (Lin & Kuo, 2013; Mikkelsen, Stojanovska, Polenakovic, Bosevski, & Apostolopoulos, 2017).

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the School of Graduate Studies, University of Cape Coast, Ghana, for giving us a research grant of GHS 3, 800 for the data collection. Without their timely support, we would have delayed the process of data collection.

-

Funding information: However, the publication of this work does not need any approval from any source except the authors.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

Appendix A1 Results of Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Goodness-of-fit indicators of the curiosity model

| Fit indices | Data value | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Chi square (χ 2) | CMIN = 454.7; df = 265; p = 000 | ≥0.000 |

| RMR | 0.019 | ≤0.09 |

| RMSEA | 0.065 | 0.05–0.10 |

| GFI | 0.93 | ≥0.90 |

| AGFI | 0.89 | ≥0.80 |

| CFI | 0.90 | ≥0.80 |

Goodness-of-fit indicators of the creativity model

| Fit indices | Data value | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Chi square (χ 2) | CMIN = 2192.1; df = 1,165; p = 000 | ≥0.000 |

| RMR | 0.064 | ≤0.09 |

| RMSEA | 0.072 | 0.05–0.10 |

| GFI | 0.90 | ≥0.90 |

| AGFI | 0.87 | ≥0.80 |

| CFI | 0.89 | ≥0.80 |

Goodness-of-fit indicators of the motivation model

| Fit indices | Data value | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Chi square (χ 2) | CMIN = 604.8; df = 329; p = 000 | ≥0.000 |

| RMR | 0.041 | ≤0.09 |

| RMSEA | 0.051 | 0.05–0.10 |

| GFI | 0.91 | ≥0.90 |

| AGFI | 0.86 | ≥0.80 |

| CFI | 0.98 | ≥0.80 |

A2 Linearity for Curiosity, Creativity, and Motivation

Scatterplot for curiosity.

Scatterplot for creativity.

Scatterplot for motivation.

References

Adamma, O. N., Ekwutosim, O. P., & Unamba, E. C. (2018). Influence of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation on pupil’s academic performance in mathematics. Supremum Journal of Mathematics Education (SJME), 2(2), 52–59.10.35706/sjme.v2i2.1322Search in Google Scholar

Ainley, M., Hidi, S., & Berndorff, D. (2002). Interest, learning, and the psychological processes that mediate their relationship. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94, 545–561. doi: 10.1037//0022-0663.94.3.545.Search in Google Scholar

Akhtar, S. N., Iqbal, M., & Tatlah, I. A. (2017). Relationship between intrinsic motivation and students’ academic achievement: A secondary level evidence. Bulletin of Education and Research, 39(2), 19–29.Search in Google Scholar

Akhtar, S. N., Tatlah, I. A., & Iqbal, M. (2018). Relationship between extrinsic motivation and students’ academic achievement: A secondary level study. Journal of Research and Reflections in Education, 12(1), 93–101.Search in Google Scholar

Alfuhaigi, S. S. (2015). School environment and creativity development: A review of literature. Journal of Educational and Instructional Studies in the World, 5(2), 33–40.Search in Google Scholar

Bandalos, D. L., Geske, J. A., & Finney, S. J. (2003). A model of statistic performance based on achievement goal theory. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(3), 604–616.10.1037/0022-0663.95.3.604Search in Google Scholar

Batey, M., Furnham, A., & Safiullina, X. (2010). Intelligence, general knowledge and personality as predictors of creativity. Learning and Individual Differences, 20(5), 532–535.10.1016/j.lindif.2010.04.008Search in Google Scholar

Boddy, C. R. (2016). Sample size for qualitative research. Qualitative Market Research, 19(4), 426–432. doi: 10.1108/QMR-06-2016-0053.Search in Google Scholar

Celik, P., Storme, M., Davila, A., & Myszkowski, N. (2016). Work-related curiosity positively predicts worker innovation. Journal of Management Development, 35, 1184–1194.10.1108/JMD-01-2016-0013Search in Google Scholar

Chemers, M. M., Hu, L., & Garcia, B. F. (2001). Academic self-efficacy and first-year college student performance and adjustment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(1), 55–64.10.1037//0022-0663.93.1.55Search in Google Scholar

Cohen, J. (1988). Set correlation and contingency tables. Applied Psychological Measurement, 12(4), 425–434.10.1177/014662168801200410Search in Google Scholar

Coleman, T. C. (2014). Positive emotion in nature as a precursor to learning. Online Submission, 2(3), 175–190.10.18404/ijemst.72106Search in Google Scholar

Collins, R. P., Litman, J. A., & Spielberger, C. D. (2004). The measurement of perceptual curiosity. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(5), 1127–1141. doi: 10.1016/s0191-8869(03)00205-8.Search in Google Scholar

Dahmen-Wassenberg, P., Kämmerle, M., Unterrainer, H. F., & Fink, A. (2016). The relation between different facets of creativity and the dark side of personality. Creativity Research Journal, 28(1), 60–66.10.1080/10400419.2016.1125267Search in Google Scholar

Dineen, R., Samuel, E., & Livesey, K. (2005). The promotion of creativity in learners: Theory and practice. Art, Design and Communication in Higher Education, 4(3), 155–172.10.1386/adch.4.3.155/1Search in Google Scholar

Ding, X., Tang, Y. Y., Deng, Y., Tang, R., & Posner, M. I. (2015). Mood and personality predict improvement in creativity due to meditation training. Learning and Individual Differences, 37, 217–221.10.1016/j.lindif.2014.11.019Search in Google Scholar

Dramanu, B. Y., & Mohammed, A. I. (2017). Academic motivation and performance of junior high school students in Ghana. European Journal of Educational and Development Psychology, 5(1), 1–11.Search in Google Scholar

Durik, A. M., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (2007). Different strokes for different folks: How individual interest moderates the effects of situational factors on task interest. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99, 597–610. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.99.3.597.Search in Google Scholar

Elliot, A. J., & Dweck, C. S. (2005). Handbook of competence and motivation. New York: Guilford Press.Search in Google Scholar

Gay, L. R., Mills, G. E., & Airasian, P. W. (2012). Educational research: Competencies for analysis and application (10th ed.). New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc.Search in Google Scholar

Grosul, M., & Feist, G. J. (2014). The creative person in science. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 8(1), 30–38.10.1037/a0034828Search in Google Scholar

Gupta, P. K., & Mili, R. (2016). Impact of academic motivation on academic achievement: A study on high school students. European Journal of Education Studies, 2(1), 1–8.Search in Google Scholar

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., & Thiele, K. O. (2017). Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modelling methods. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(5), 616–632.10.1007/s11747-017-0517-xSearch in Google Scholar

Harrison, S. H., & Dossinger, K. (2017). Pliable guidance: A multilevel model of curiosity, feedback-seeking, and feedback-giving in creative work. Academy of Management Journal, 60(6), 2051–2072.10.5465/amj.2015.0247Search in Google Scholar

Hoffman, A. & Holzhuter, J. (2012). The evolution of higher education: Innovation as natural selection. Lanham, MD: American Council on Education, Rowman & Litttlefield Publishers Inc.Search in Google Scholar

Hong-Keung, Y., Man-Shan, K., & Lai-Fong, C. A. (2012). The impact of curiosity and external regulation on intrinsic motivation: An empirical study in Hong Kong Education. Psychology Research, 2(5), 295–307.10.17265/2159-5542/2012.05.003Search in Google Scholar

Horng, J. S., Tsai, C. Y., Yang, T. C., & Liu, C. H. (2016). Exploring the relationship between proactive personality, work environment and employee creativity among tourism and hospitality employees. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 54, 25–34.10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.01.004Search in Google Scholar

Ivcevic, Z., & Brackett, M. A. (2015). Predicting creativity: Interactive effects of openness to experience and emotion regulation ability. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 9(4), 480.10.1037/a0039826Search in Google Scholar

Jauk, E., Benedek, M., & Neubauer, A. C. (2014). The road to creative achievement: A latent variable model of ability and personality predictors. European Journal of Personality, 28(1), 95–105.10.1002/per.1941Search in Google Scholar

Karwowski, M. (2012). Did curiosity kill the cat? Relationship between trait curiosity, creative self-efficacy and creative personal identity. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 8(4), 547–558. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v 8i4.513.Search in Google Scholar

Kashdan, T. B., & Fincham, F. D. (2002). Facilitating creativity by regulating curiosity: Comment. American Psychologist, 57(5), 373–374. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.57.5.373.Search in Google Scholar

Kashdan, T. B., & Silvia, P. (2009). Curiosity and interest: The benefits of thriving on novelty and challenge. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195187243.013.0034Search in Google Scholar

Kashdan, T. B., Stiksma, M. C., Disabato, D., McKnight, P. E., Bekier, J., Kaji, J., & Lazarus, R. (2018). The five-dimensional curiosity scale: Capturing the bandwidth of curiosity and identifying four unique subgroups of curious people. Journal of Research in Personality, 73, 130–149.10.1016/j.jrp.2017.11.011Search in Google Scholar

Kaufman, J. C. (2012). Development of the Kaufman Domains of Creativity Scale (K-DOCS). Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 6, 1–11.10.1037/a0029751Search in Google Scholar

Lin, T. W., & Kuo, Y. M. (2013). Exercise benefits brain function: The monoamine connection. Brain Sciences, 3(1), 39–53.10.3390/brainsci3010039Search in Google Scholar

Litman, J. (2005). Curiosity and the pleasures of learning: Wanting and liking new information. Cognition and Emotion, 19(6), 793–814.10.1080/02699930541000101Search in Google Scholar

Litman, J. A., & Jimerson, T. L. (2004). The measurement of curiosity as a feeling of deprivation. Journal of Personality Assessment, 82(2), 147–157. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8202.Search in Google Scholar

Lucas, B., Claxton, G. & Spencer, E. (2013). Progression in student creativity in school: First steps towards new forms of formative assessments. OECD Education Working Papers, No. 86. OECD Publishing. doi: 10.1787/5k4dp59msdwk-en.Search in Google Scholar

Lyons, I. M., & Beilock, S. L. (2011). Numerical ordering ability mediates the relation between number-sense and arithmetic competence. Cognition, 121(2), 256–261.10.1016/j.cognition.2011.07.009Search in Google Scholar

McWilliam, E. (2007). Teaching for creativity: Towards sustainable and replicable pedagogical practice. Higher Education, 56(6), 633–643.10.1007/s10734-008-9115-7Search in Google Scholar

Mikkelsen, K., Stojanovska, L., Polenakovic, M., Bosevski, M., & Apostolopoulos, V. (2017). Exercise and mental health. Maturitas, 106, 48–56.10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.09.003Search in Google Scholar

Muola, J. M. (2010). A study of the relationship between academic achievement motivation and home environment among standard eight pupils. Educational Research and Reviews, 5(5), 213–217.Search in Google Scholar

Pallant, J. (2016). SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS version 18 (6th ed.). Maidenhead, Berkshire: Open University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Pekrun, R. (2011). Emotions as drivers of learning and cognitive development. In New perspectives on affect and learning technologies (pp. 23–39). New York, NY: Springer New York.10.1007/978-1-4419-9625-1_3Search in Google Scholar

Pekrun, R. (2019). The murky distinction between curiosity and interest: State of the art and future prospects. Educational Psychology Review, 31(4), 905–914.10.1007/s10648-019-09512-1Search in Google Scholar

Sansone, C., & Smith, J. L. (2000). The “how” of goal pursuit: Interest and self-regulation. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 306–309.Search in Google Scholar

Senko, C., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (2005). Regulation of achievement goals: The role of competence feedback. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(3), 320–336.10.1037/0022-0663.97.3.320Search in Google Scholar

Serdyukov, P. (2017). Innovation in education: What works, what doesn’t, and what to do about it? Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching and Learning, 10(1), 4–33.10.1108/JRIT-10-2016-0007Search in Google Scholar

Sharma, D., & Sharma, S. (2018). Relationship between motivation and academic achievement. International Journal of Advances in Scientific Research, 4(246), 1–5. doi: 10.7439/iiasr.Search in Google Scholar

Shin, D. D., & Kim, S. I. (2019). Homo curious: Curious or interested? Educational Psychology Review, 31, 1–22.10.1007/s10648-019-09497-xSearch in Google Scholar

Shroff, R. H., Vogel, D. R., & Coombes, J. (2008). Assessing individual-level factors supporting student intrinsic motivation in online discussions: A qualitative study. Journal of Information Systems Education, 19(1), 111–126.Search in Google Scholar

Silvia, P. J., Beaty, R. E., Nusbaum, E. C., Eddington, K. M., Levin-Aspenson, H., & Kwapil, T. R. (2014). Everyday creativity in daily life: An experience-sampling study of “little c” creativity. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 8(2), 183.10.1037/a0035722Search in Google Scholar

Tan, C. S., Lau, X. S., Kung, Y. T., & Kailsan, R. A. L. (2019). Openness to experience enhances creativity: The mediating role of intrinsic motivation and the creative process engagement. The Journal of Creative Behaviour, 53(1), 109–119.10.1002/jocb.170Search in Google Scholar

Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., Blais, M. R., Briere, N. M., Senecal, C., & Vallieres, E. F. (1992). The Academic Motivation Scale: A measure of intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivation in education. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 52(4), 1003–1017.10.1177/0013164492052004025Search in Google Scholar

Van Tilburg, W. A., Sedikides, C., & Wildschut, T. (2015). The mnemonic muse: Nostalgia fosters creativity through openness to experience. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 59, 1–7.10.1016/j.jesp.2015.02.002Search in Google Scholar

Zare, G., Jamshidi, A., Rastegar, A., & Jahromi, R. G. (2011). Presenting a model of predicting competitive anxiety based on intelligence beliefs and achievement goals. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30, 1127–1132.10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.220Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, X., & Bartol, K. M. (2010). The influence of creative process engagement on employee creative performance and overall job performance: A curvilinear assessment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 862.10.1037/a0020173Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Building Bridges in STEAM Education in the 21st Century - Part II

- The Flipped Classroom Optimized Through Gamification and Team-Based Learning

- Method and New Doctorate Graduates in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics of the European Innovation Scoreboard as a Measure of Innovation Management in Subdisciplines of Management and Quality Studies

- Impact of Gamified Problem Sheets in Seppo on Self-Regulation Skills

- Special Issue: Disruptive Innovations in Education - Part I

- School-Based Education Program to Solve Bullying Cases in Primary Schools

- The Project Trauma-Informed Practice for Workers in Public Service Settings: New Strategies for the Same Old Objective

- Regular Articles

- Limits of Metacognitive Prompts for Confidence Judgments in an Interactive Learning Environment

- “Why are These Problems Still Unresolved?” Those Pending Problems, and Neglected Contradictions in Online Classroom in the Post-COVID-19 Era

- Potential Elitism in Selection to Bilingual Studies: A Case Study in Higher Education

- Predicting Time to Graduation of Open University Students: An Educational Data Mining Study

- Risks in Identifying Gifted Students in Mathematics: Case Studies

- Technology Integration in Teacher Education Practices in Two Southern African Universities

- Comparing Emergency Remote Learning with Traditional Learning in Primary Education: Primary School Student Perspectives

- Pedagogical Technologies and Cognitive Development in Secondary Education

- Sense of Belonging as a Predictor of Intentions to Drop Out Among Black and White Distance Learning Students at a South African University

- Gender Sensitivity of Teacher Education Curricula in the Republic of Croatia

- A Case Study of Biology Teaching Practices in Croatian Primary Schools

- The Impact of “Scratch” on Student Engagement and Academic Performance in Primary Schools

- Examining the Structural Relationships Between Pre-Service Science Teachers’ Intention to Teach and Perceptions of the Nature of Science and Attitudes

- Validation of the Undesirable Behavior Strategies Questionnaire: Physical Educators’ Strategies within the Classroom Ecology

- Economics Education, Decision-Making, and Entrepreneurial Intention: A Mediation Analysis of Financial Literacy

- Deconstructing Teacher Engagement Techniques for Pre-service Teachers through Explicitly Teaching and Applying “Noticing” in Video Observations

- Influencing Factors of Work–Life Balance Among Female Managers in Chinese Higher Education Institutions: A Delphi Study

- Examining the Interrelationships Among Curiosity, Creativity, and Academic Motivation Using Students in High Schools: A Multivariate Analysis Approach

- Teaching Research Methodologies in Education: Teachers’ Pedagogical Practices in Portugal

- Normrank Correlations for Testing Associations and for Use in Latent Variable Models

- “The More, the Merrier; the More Ideas, the Better Feeling”: Examining the Role of Creativity in Regulating Emotions among EFL Teachers

- Principals’ Demographic Qualities and the Misuse of School Material Capital in Secondary Schools

- Enhancing DevOps Engineering Education Through System-Based Learning Approach

- Uncertain Causality Analysis of Critical Success Factors of Special Education Mathematics Teaching

- Novel Totto-Chan by Tetsuko Kuroyanagi: A Study of Philosophy of Progressivism and Humanism and Relevance to the Merdeka Curriculum in Indonesia

- Global Education and Critical Thinking: A Necessary Symbiosis to Educate for Critical Global Citizenship

- The Mediating Effect of Optimism and Resourcefulness on the Relationship between Hardiness and Cyber Delinquent Among Adolescent Students

- Enhancing Social Skills Development in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Evaluation of the “Power of Camp Inclusion” Program

- The Influence of Student Learning, Student Expectation and Quality of Instructor on Student Perceived Satisfaction and Student Academic Performance: Under Online, Hybrid and Physical Classrooms

- Household Size and Access to Education in Rural Burundi: The Case of Mutaho Commune

- The Impact of the Madrasati Platform Experience on Acquiring Mathematical Concepts and Improving Learning Motivation from the Point of View of Mathematics Teachers

- The Ideal Path: Acquiring Education and Gaining Respect for Parents from the Perspective of Arab-Bedouin Students

- Exploring Mentor Teachers’ Experiences and Practices in Japan: Formative Intervention for Self-Directed Development of Novice Teachers

- Research Trends and Patterns on Emotional Intelligence in Education: A Bibliometric and Knowledge Mapping During 2012–2021

- Openness to Change and Academic Freedom in Jordanian Universities

- Digital Methods to Promote Inclusive and Effective Learning in Schools: A Mixed Methods Research Study

- Translation Competence in Translator Training Programs at Saudi Universities: Empirical Study

- Self-directed Learning Behavior among Communication Arts Students in a HyFlex Learning Environment at a Government University in Thailand

- Unveiling Connections between Stress, Anxiety, Depression, and Delinquency Proneness: Analysing the General Strain Theory

- The Expression of Gratitude in English and Arabic Doctoral Dissertation Acknowledgements

- Subtexts of Most Read Articles on Social Sciences Citation Index: Trends in Educational Issues

- Experiences of Adult Learners Engaged in Blended Learning beyond COVID-19 in Ghana

- The Influence of STEM-Based Digital Learning on 6C Skills of Elementary School Students

- Gender and Family Stereotypes in a Photograph: Research Using the Eye-Tracking Method

- ChatGPT in Teaching Linear Algebra: Strides Forward, Steps to Go

- Partnership Quality, Student’s Satisfaction, and Loyalty: A Study at Higher Education Legal Entities in Indonesia

- SEA’s Science Teacher Voices Through the Modified World Café

- Construction of Entrepreneurship Coaching Index: Based on a Survey of Art Design Students in Higher Vocational Colleges in Guangdong, China

- The Effect of Audio-Assisted Reading on Incidental Learning of Present Perfect by EFL Learners

- Comprehensive Approach to Training English Communicative Competence in Chemistry

- The Collaboration of Teaching at The Right Level Approach with Problem-Based Learning Model

- Effectiveness of a Pop-Up Story-Based Program for Developing Environmental Awareness and Sustainability Concepts among First-Grade Elementary Students

- Effect of Computer Simulation Integrated with Jigsaw Learning Strategy on Students’ Attitudes towards Learning Chemistry

- Unveiling the Distinctive Impact of Vocational Schools Link and Match Collaboration with Industries for Holistic Workforce Readiness

- Students’ Perceptions of PBL Usefulness

- Assessing the Outcomes of Digital Soil Science Curricula for Agricultural Undergraduates in the Global South

- The Relationship between Epistemological Beliefs and Assessment Conceptions among Pre-Service Teachers

- Review Articles

- Fostering Creativity in Higher Education Institution: A Systematic Review (2018–2022)

- The Effects of Online Continuing Education for Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Scoping Review

- The Impact of Job Satisfaction on Teacher Mental Health: A Call to Action for Educational Policymakers

- Developing Multilingual Competence in Future Educators: Approaches, Challenges, and Best Practices

- Using Virtual Reality to Enhance Twenty-First-Century Skills in Elementary School Students: A Systematic Literature Review

- State-of-the-Art of STEAM Education in Science Classrooms: A Systematic Literature Review

- Integration of Project-Based Learning in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics to Improve Students’ Biology Practical Skills in Higher Education: A Systematic Review

- Teaching Work and Inequality in Argentina: Heterogeneity and Dynamism in Educational Research

- Case Study

- Teachers’ Perceptions of a Chatbot’s Role in School-based Professional Learning

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Building Bridges in STEAM Education in the 21st Century - Part II

- The Flipped Classroom Optimized Through Gamification and Team-Based Learning

- Method and New Doctorate Graduates in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics of the European Innovation Scoreboard as a Measure of Innovation Management in Subdisciplines of Management and Quality Studies

- Impact of Gamified Problem Sheets in Seppo on Self-Regulation Skills

- Special Issue: Disruptive Innovations in Education - Part I

- School-Based Education Program to Solve Bullying Cases in Primary Schools

- The Project Trauma-Informed Practice for Workers in Public Service Settings: New Strategies for the Same Old Objective

- Regular Articles

- Limits of Metacognitive Prompts for Confidence Judgments in an Interactive Learning Environment

- “Why are These Problems Still Unresolved?” Those Pending Problems, and Neglected Contradictions in Online Classroom in the Post-COVID-19 Era

- Potential Elitism in Selection to Bilingual Studies: A Case Study in Higher Education

- Predicting Time to Graduation of Open University Students: An Educational Data Mining Study

- Risks in Identifying Gifted Students in Mathematics: Case Studies

- Technology Integration in Teacher Education Practices in Two Southern African Universities

- Comparing Emergency Remote Learning with Traditional Learning in Primary Education: Primary School Student Perspectives

- Pedagogical Technologies and Cognitive Development in Secondary Education

- Sense of Belonging as a Predictor of Intentions to Drop Out Among Black and White Distance Learning Students at a South African University

- Gender Sensitivity of Teacher Education Curricula in the Republic of Croatia

- A Case Study of Biology Teaching Practices in Croatian Primary Schools

- The Impact of “Scratch” on Student Engagement and Academic Performance in Primary Schools

- Examining the Structural Relationships Between Pre-Service Science Teachers’ Intention to Teach and Perceptions of the Nature of Science and Attitudes

- Validation of the Undesirable Behavior Strategies Questionnaire: Physical Educators’ Strategies within the Classroom Ecology

- Economics Education, Decision-Making, and Entrepreneurial Intention: A Mediation Analysis of Financial Literacy

- Deconstructing Teacher Engagement Techniques for Pre-service Teachers through Explicitly Teaching and Applying “Noticing” in Video Observations

- Influencing Factors of Work–Life Balance Among Female Managers in Chinese Higher Education Institutions: A Delphi Study

- Examining the Interrelationships Among Curiosity, Creativity, and Academic Motivation Using Students in High Schools: A Multivariate Analysis Approach

- Teaching Research Methodologies in Education: Teachers’ Pedagogical Practices in Portugal

- Normrank Correlations for Testing Associations and for Use in Latent Variable Models

- “The More, the Merrier; the More Ideas, the Better Feeling”: Examining the Role of Creativity in Regulating Emotions among EFL Teachers

- Principals’ Demographic Qualities and the Misuse of School Material Capital in Secondary Schools

- Enhancing DevOps Engineering Education Through System-Based Learning Approach

- Uncertain Causality Analysis of Critical Success Factors of Special Education Mathematics Teaching

- Novel Totto-Chan by Tetsuko Kuroyanagi: A Study of Philosophy of Progressivism and Humanism and Relevance to the Merdeka Curriculum in Indonesia

- Global Education and Critical Thinking: A Necessary Symbiosis to Educate for Critical Global Citizenship

- The Mediating Effect of Optimism and Resourcefulness on the Relationship between Hardiness and Cyber Delinquent Among Adolescent Students

- Enhancing Social Skills Development in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Evaluation of the “Power of Camp Inclusion” Program

- The Influence of Student Learning, Student Expectation and Quality of Instructor on Student Perceived Satisfaction and Student Academic Performance: Under Online, Hybrid and Physical Classrooms

- Household Size and Access to Education in Rural Burundi: The Case of Mutaho Commune

- The Impact of the Madrasati Platform Experience on Acquiring Mathematical Concepts and Improving Learning Motivation from the Point of View of Mathematics Teachers

- The Ideal Path: Acquiring Education and Gaining Respect for Parents from the Perspective of Arab-Bedouin Students

- Exploring Mentor Teachers’ Experiences and Practices in Japan: Formative Intervention for Self-Directed Development of Novice Teachers

- Research Trends and Patterns on Emotional Intelligence in Education: A Bibliometric and Knowledge Mapping During 2012–2021

- Openness to Change and Academic Freedom in Jordanian Universities

- Digital Methods to Promote Inclusive and Effective Learning in Schools: A Mixed Methods Research Study

- Translation Competence in Translator Training Programs at Saudi Universities: Empirical Study

- Self-directed Learning Behavior among Communication Arts Students in a HyFlex Learning Environment at a Government University in Thailand

- Unveiling Connections between Stress, Anxiety, Depression, and Delinquency Proneness: Analysing the General Strain Theory

- The Expression of Gratitude in English and Arabic Doctoral Dissertation Acknowledgements

- Subtexts of Most Read Articles on Social Sciences Citation Index: Trends in Educational Issues

- Experiences of Adult Learners Engaged in Blended Learning beyond COVID-19 in Ghana

- The Influence of STEM-Based Digital Learning on 6C Skills of Elementary School Students

- Gender and Family Stereotypes in a Photograph: Research Using the Eye-Tracking Method

- ChatGPT in Teaching Linear Algebra: Strides Forward, Steps to Go

- Partnership Quality, Student’s Satisfaction, and Loyalty: A Study at Higher Education Legal Entities in Indonesia

- SEA’s Science Teacher Voices Through the Modified World Café

- Construction of Entrepreneurship Coaching Index: Based on a Survey of Art Design Students in Higher Vocational Colleges in Guangdong, China

- The Effect of Audio-Assisted Reading on Incidental Learning of Present Perfect by EFL Learners

- Comprehensive Approach to Training English Communicative Competence in Chemistry

- The Collaboration of Teaching at The Right Level Approach with Problem-Based Learning Model

- Effectiveness of a Pop-Up Story-Based Program for Developing Environmental Awareness and Sustainability Concepts among First-Grade Elementary Students

- Effect of Computer Simulation Integrated with Jigsaw Learning Strategy on Students’ Attitudes towards Learning Chemistry

- Unveiling the Distinctive Impact of Vocational Schools Link and Match Collaboration with Industries for Holistic Workforce Readiness

- Students’ Perceptions of PBL Usefulness

- Assessing the Outcomes of Digital Soil Science Curricula for Agricultural Undergraduates in the Global South

- The Relationship between Epistemological Beliefs and Assessment Conceptions among Pre-Service Teachers

- Review Articles

- Fostering Creativity in Higher Education Institution: A Systematic Review (2018–2022)

- The Effects of Online Continuing Education for Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Scoping Review

- The Impact of Job Satisfaction on Teacher Mental Health: A Call to Action for Educational Policymakers

- Developing Multilingual Competence in Future Educators: Approaches, Challenges, and Best Practices

- Using Virtual Reality to Enhance Twenty-First-Century Skills in Elementary School Students: A Systematic Literature Review

- State-of-the-Art of STEAM Education in Science Classrooms: A Systematic Literature Review

- Integration of Project-Based Learning in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics to Improve Students’ Biology Practical Skills in Higher Education: A Systematic Review

- Teaching Work and Inequality in Argentina: Heterogeneity and Dynamism in Educational Research

- Case Study

- Teachers’ Perceptions of a Chatbot’s Role in School-based Professional Learning