Abstract

Temper embrittlement induced by segregation of metalloid solutes to grain boundary (GB) was evaluated by a shift of the ductile-brittle transition temperature (DBTT). DBTT was found to be linearly correlated with the amount of metalloid on the GB (Xgb) for both dynamic and static displacement rates (dδ/dt) in high and medium hardness steels. Recent first-principles calculations have determined the GB embrittling potency (Δep) of segregated Sb, Sn and P. In both high and medium hardness steels, the slope (α) of DBTT vs. Xgb was found to be linearly dependent on Δep regardless of the segregated solutes. In high hardness steels, the slope is independent of dδ/dt, while in medium hardness steels the α is dependent on dδ/dt. An Arrhenius plot of dδ/dt vs. the reciprocal DBTT was used to drive the thermal activation energy (Eact), which represents a barrier to plasticity. It was found that Eact correlates to a reduction in the GB fracture surface energy. The Eact depends strongly on GB decohesion in high hardness steels but only weakly depends on it in medium hardness steels.

1 Introduction

Classical structural problems of temper embrittlement are evaluated in terms of the change in the ductile-brittle transition temperature (DBTT). The development of scanning Auger electron spectroscopy (scanning AES) enabled the detection of several types and amounts of metalloid elements (Xgb) at grain boundaries (GBs). Based on interfacial thermodynamic theory (Rice, 1976; Hirth & Rice, 1980; Rice & Wang, 1989), first-principles calculations provide an atomistic view of the effects of immobile solutes (Sb, Sn and P) on the GB decohesion. The fracture surface (FS) energy linearly deceases with the amount of embrittling solutes. The embrittling potency Δep (eV) is ranked as Δep for 1.36 for Sb, 0.99 for Sn and 0.38 for P (Wu et al., 1994; Yamaguchi, 2011; Yamaguchi & Kameda, 2014). The GB decohesion (2γint) is given by

where

The relationship between the slope (α) of DBTT vs. Xgb, and Δep is a function of displacement rate (dδ/dt) and hardness. An Arrhenius plot of the dδ/dt and the reciprocal DBTT is analyzed to derive the activation energy (Eact). High hardness steel has a stronger dependence on GB decohesion than medium hardness steels.

This study reanalyzes the effect on temper embrittlement in 3.5Ni-1.7Cr steels doped individually with Sb, Sn and P undertaken by McMahon’s group of the University of Pennsylvania (Mulford et al., 1976a,b; Cianelli et al., 1977; Kameda & McMahon, 1980; Takayama et al., 1980). The temper embrittlement induced by solute segregation was investigated in light of the GB decohesion and Eact.

2 Materials and methods

These steels were thermally treated by austenitizing, oil-quenching and tempering. Samples were aged between 10 and 1000 h at about 753 K to achieve a wide range of GB segregation without softening. The solute compositions of the steels studied are listed in Table 1. GB FSs broken in an ultra-high vacuum chamber were analyzed by (scanning AES), the results of which were converted to the GB coverage Xgb of the segregated solute. The DBTT values of these differently embrittled samples were measured by Charpy dynamic and cantilever static notched tests under dynamic (5.25 m/s) and static (8.27×10−6 m/s) dδ/dt. The DBTT was defined by the midpoints between the upper and lower shelf energy or the ductile/brittle fracture mode. Some samples doped with weaker embrittling solutes in medium hardness steels with slow dδ/dt exhibited a mixture of GB and cleavage fracture. Cleavage DBTT of pure Ni-Cr steels is lower than Ni with less alloy steels.

Composition of 3.5Ni-1.7Cr steels individually doped with Sb, Sn or P and tested under static dδ/dt.a

| C | Sb | Sn | P | S | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sb-doped | 0.29 0.31a |

0.056 0.06a |

0.0004 | 0.0035 | |

| Sn-doped | 0.3 0.39a |

0.061 0.04a |

|||

| P-doped | 0.29 0.39 |

0.061 0.04a |

0.07 0.061a |

||

| Undoped | 0.3 | 0.006 |

-

Resulting microstructures (i) ASTM grain code from 2.8 to 4; (ii) Vickers high (302~285) and medium (210~238) hardness; (iii); aging at 753 K for 10–1000 h controlling the different degrees of segregated solutes, while sustaining hardness. Note that Sn-doped steels tested under static dδ/dt were corrected into coverage based on the same α in the high hardness.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 DBTT relevance to GB decohesion

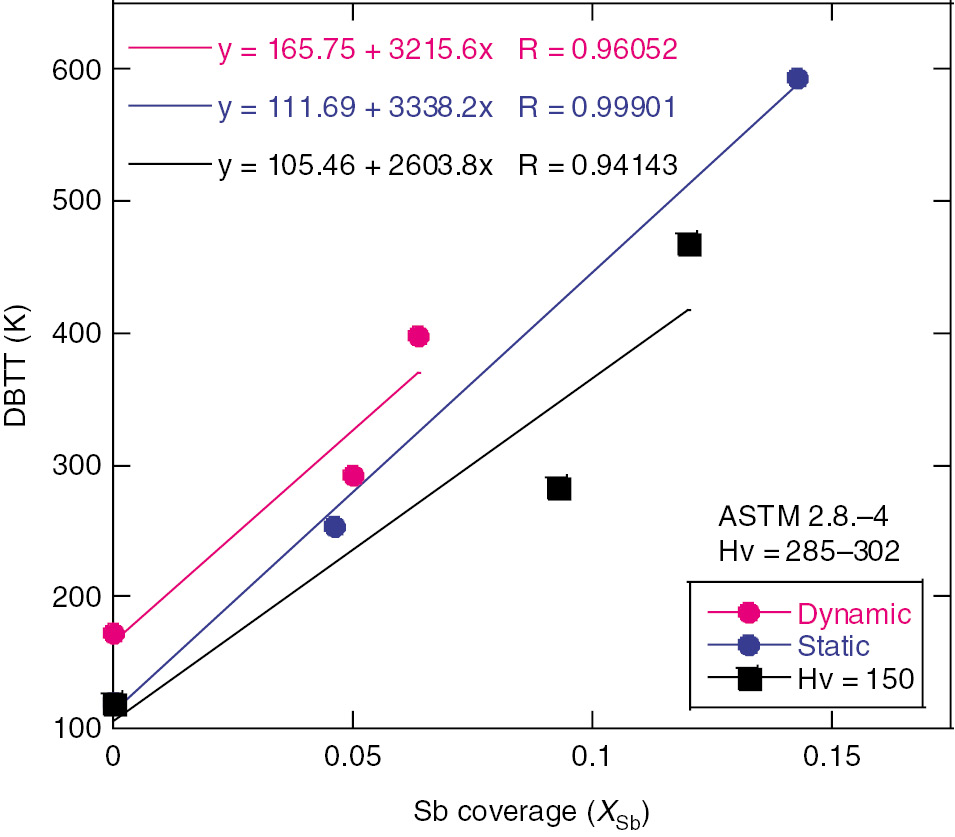

The previously obtained experimental data were reanalyzed in terms of the GB decohesion and their relationships with the effects of dδ/dt and hardness on the DBTT in Ni-Cr steels. It was found that the DBTT has a linear relationship with Xgb. Figure 1 shows the effects of segregated Sb in high, medium and low hardness steels, under dynamic and static loading. The linear relationship between DBTT and Xgb is in Equation (1) where the values of DBTTtg for cleavage fracture were identified from the baseline as indicated in Figure 1 for segregated Sb for Xgb=0.

Linear dependence of DBTT on segregated Sb for dynamic and static displacement rates dδ/dt in high hardness steels together with low hardness steels tested under slow dδ/dt.

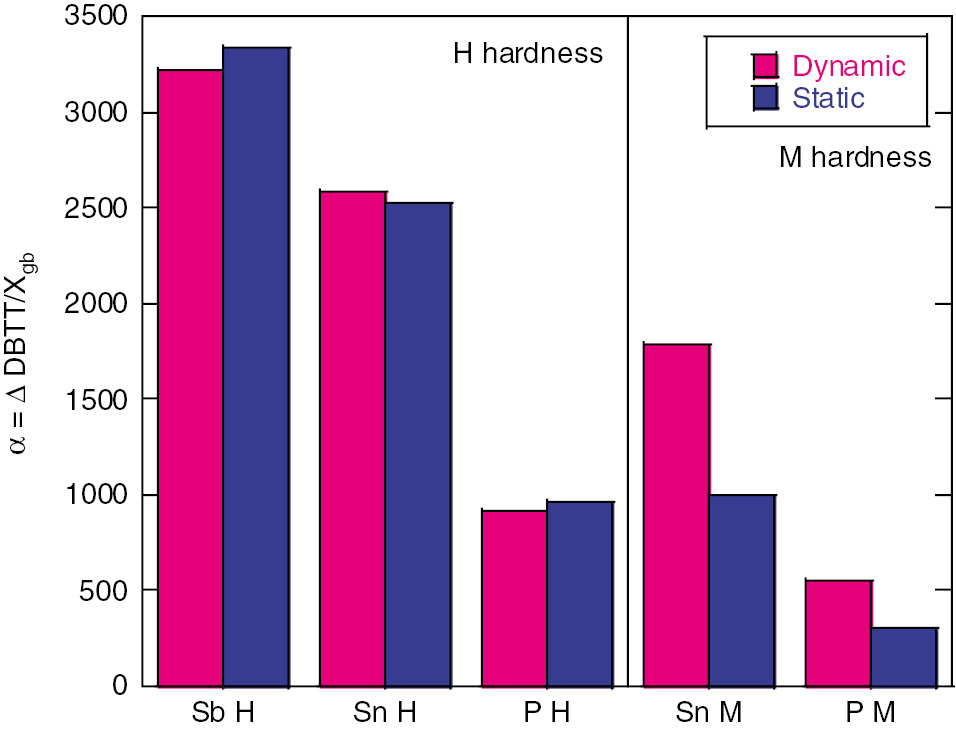

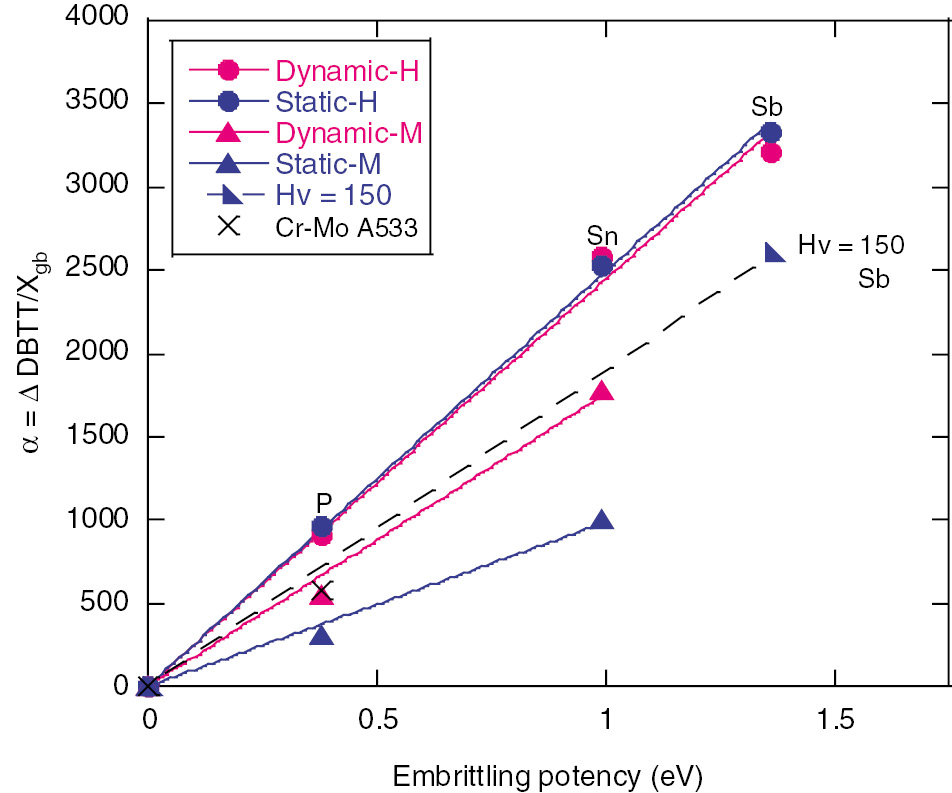

Figure 2 shows the slope in terms of increases in the order of the potency of segregated solutes, Sb, Sn and P. The value of α remains the same regardless of the dδ/dt in the high hardness steels. Sn- and P-doped medium hardness steels exhibited a similar order potency. However, the dynamic dδ/dt produces higher values of α than the static dδ/dt in medium hardness steels. Figure 3 depicts the linear relations between α and Δep for all three dopants at both dδ/dt. The medium hardness steels clearly are affected by the dδ/dt; this is not true for high hardness steels where there is no dependence on dδ/dt. The value of α for Sb-doped steel with lower hardness in slow dδ/dt was observed to be close to that of segregated Sn with the medium hardness.

Relationship between slope (α) for dynamic and static dδ/dt and high and medium hardness steels.

Relationship between slope (α) and Δep for all dδ/dt and high and medium hardness steels.

3.2 Relation of activated energy to GB decohesion

dδ/dt is related to the Eact. The mode change between ductile and GB fracture is characterized with the DBTT. The dδ/dt is an experimental parameter that is related to DBTT through Equation (3). dδ/dt drives dislocation motion, overcoming the energy barrier Eact. kB is the Boltzmann constant (Magnusson & Baldwin, 1957; Giannattasio et al., 2007; Kameda & Nishiyama, 2011).

The Eact is calculated from the slope of an Arrhenius plot of the natural log of dδ/dt vs. the reciprocal of DBTT. An example of such plots for Sb in high hardness steels is shown in Figure 4 for a range of Xgb. Eact was calculated for the three metalloids at varying Xgb using Equation (4).

Reciprocal plot of DBTT on natural log (displacement rate) for various segregated Sb and high hardness.

3.3 Activation energy relevance to GB decohesion

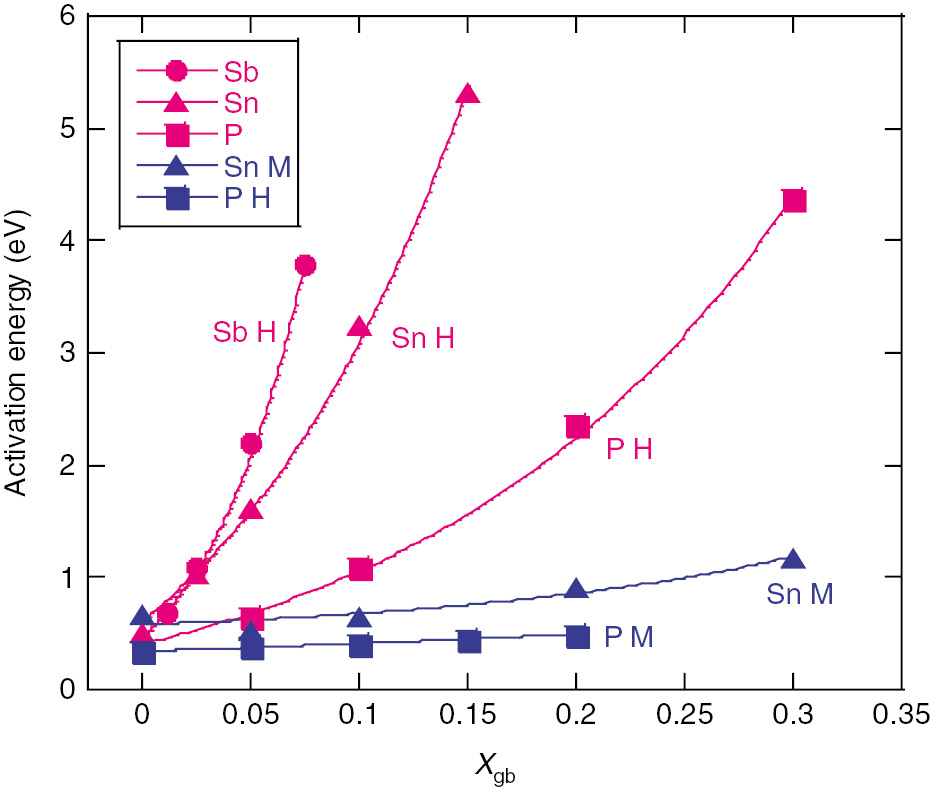

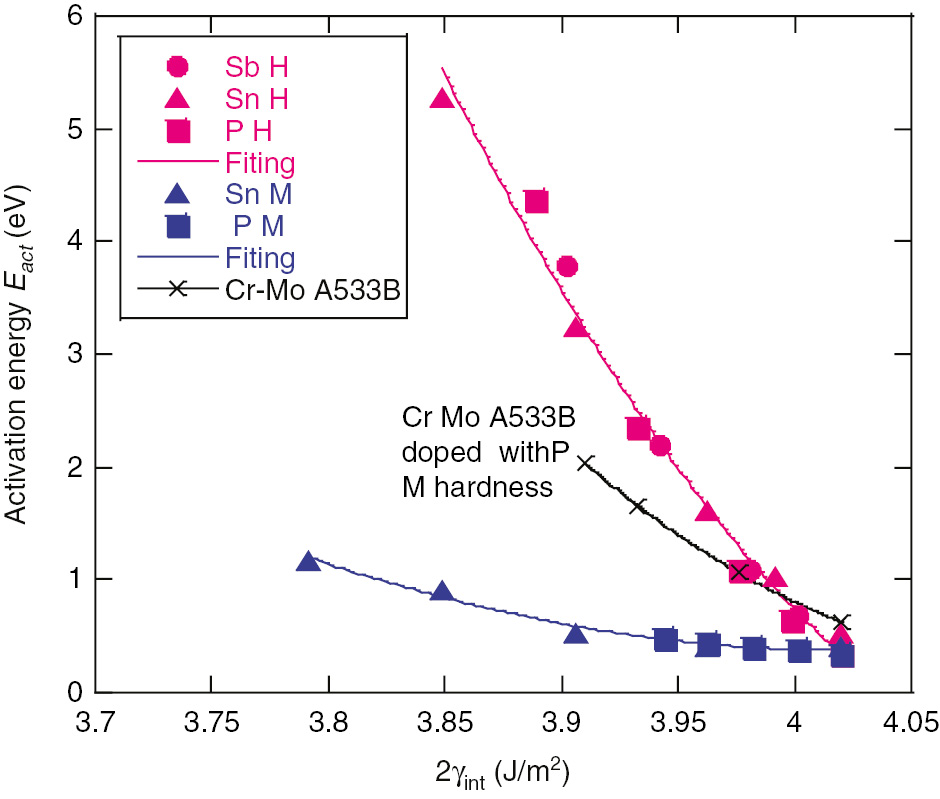

Equation (4) was applied to selected values of Xgb for both the high and medium hardness steels (using Figure 1: for examples for segregated Sb with high hardness). In Figure 5, Eact exponentially increases with Xgb for all three solutes in high and medium hardness steels. Eact is much higher in the high hardness steels than in the medium hardness steels. As indicated clearly in Figure 6, Eact is correlated with 2γint regardless of the type of segregated solute. The Eact with high hardness depends strongly and approximately linearly on 2γint, but the dependence is weak for medium hardness steels.

Relationship of activation energy (Eact) to segregated solute (Xgb) for all test conditions.

Activation energy vs. 2γint for all test conditions. Red curve, high hardness; blue, medium hardness; black, A533B and Cr-Mo.

3.4 DBTT affected by mixture of GB and cleavage fracture

It has been noted (Kameda & Nishiyama, 2011) that DBTT in A533B and Cr-Mo steels doped with P and medium hardness do not correlate with Xgb. Therefore, the effective P segregation,

4 Summary

Temper embrittlement is affected not only by segregated metalloid solutes but also by dδ/dt and hardness. It is important to relate changes in the FS energy, and the energy barrier to dislocation motion, Eact, to the transition from ductile to brittle GB fracture. GB metalloid segregation leads to an increase in Eact, a decrease in FS energy, and leads to the transition from ductile to brittle GB fracture.

The slope of DBTT vs. Xgb, (α) is linearly related to Δep under dynamic and static dδ/dt states in high hardness steels, but it depends on dδ/dt in medium hardness steels.

An Arrhenius plot is plotted to the reciprocal DBTT to derive Eact.

The value of Eact increases exponentially with Xgb in both the high and medium hard steels, while it is more strongly related to 2γint in the hard steels than in the medium steels.

The dependence of Eact on 2γint is much stronger in high hardness steel than in medium hardness steels.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate Dr. Yamaguchi M at Japan Atomic Energy Agency for contributions to first-principles calculations.

References

Chen YT, Atteridge DG, Gerberich WW. Plastic flow of Fe-binary alloys – I. A description at low temperatures. Acta Metall 1981; 29: 1171–1186.10.1016/0001-6160(81)90068-7Search in Google Scholar

Cianelli AK, Feng HC, Ucisk AH, McMahon Jr CJ. Temper embrittlement of Ni-Cr steel by Sn. Metall Mater Trans 1977; A7: 1059–1061.10.1007/BF02667390Search in Google Scholar

Giannattasio A, Tanaka M, Joseph TD, Roberts SG. An empirical correlation between temperature and activation energy for brittle-to-ductile transitions in single-phase materials. Phy Scripta 2007; T128: 87–90.10.1088/0031-8949/2007/T128/017Search in Google Scholar

Hirth JP, Rice JR. On the thermodynamics of adsorption at interfaces as it influences decohesion. Metall Mater Trans 1980; 11A: 1501–1511.10.1007/BF02654514Search in Google Scholar

Kameda J, McMahon Jr CJ. Solute segregation and brittle fracture in an alloy steel. Metall Mater Trans 1980; A11: 91–101.10.1007/BF02700442Search in Google Scholar

Kameda J, Nishiyama Y. Combined effects of phosphorus segregation and partial intergranular fracture on the ductile-brittle temperature in structural alloy steels. Mater Sci Eng 2011; A528: 3705–3713.10.1016/j.msea.2011.01.018Search in Google Scholar

Magnusson AW, Baldwin Jr WM. Low temperature brittlement. J Mech Phys Solids 1957; 5: 172–181.10.1016/0022-5096(57)90003-0Search in Google Scholar

Mulford RA, McMahon Jr CJ, Pope DP, Feng HC. Temper embrittlement of Ni-Cr steel by phosphorus. Metall Mater Trans 1976a; A7: 1183–1195.10.1007/BF02656602Search in Google Scholar

Mulford RA, McMahon Jr CJ, Pope DP, Feng H. Temper embrittlement of Ni-Cr steel by antimony: III. Effects of Ni and Cr. Metall Mater Trans 1976b; A7: 1269–1274.10.1007/BF02658810Search in Google Scholar

Rice JR. Hydrogen and interfacial decohesion. In: Thompson AW, Bernstein IM, editors. Effect of hydrogen on behavior of materials. New York, USA: Metallurgical Society of AIME, 1976: 455466.Search in Google Scholar

Rice RJ, Wang JS. Embrittlement interfaces by solute segregation. Mater Sci Eng 1989; A107: 23–40.10.1016/0921-5093(89)90372-9Search in Google Scholar

Takayama S, Ogura T, Shin-chung Fu, McMahon Jr CJ. The calculation of transition temperature changes in steels due to temper embrittlement. Metall Mater Trans 1980; A11: 1513–1530.10.1007/BF02654515Search in Google Scholar

Wu R, Freeman AJ, Olson GB. First principles determination of the effects of phosphorus and boron on iron grain boundary cohesion. Science 1994; 265: 376–380.10.1126/science.265.5170.376Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Yamaguchi M. First-principles study on the grain boundary embrittlement of metals by solute segregation: Part I. Iron (Fe)-solute (B, C, P and S) systems. Metall Mater Trans 2011; A42: 319–329.10.1007/s11661-010-0381-5Search in Google Scholar

Yamaguchi M, Kameda J. Multiscale thermodynamic analysis on fracture toughness loss induced by solute segregation in steel. Phil Mag 2014; 94: 2131–2150.10.1080/14786435.2014.906757Search in Google Scholar

©2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Editorial

- International Conference on Stress-Assisted Corrosion Damage V (Hernstein, Austria, July 15–20, 2018)

- General topics

- Building environmental history for Naval aircraft

- Discussion of some recent literature on hydrogen-embrittlement mechanisms: addressing common misunderstandings

- When do small fatigue cracks propagate and when are they arrested?

- Computational modeling of pitting corrosion

- Hydrogen-assisted cracking

- Hydrogen effects on mechanical performance of nodular cast iron

- Ductile-brittle transition temperature shift controlled by grain boundary decohesion and thermally activated energy in Ni-Cr steels

- Hydrogen diffusion in low alloy steels under cyclic loading

- Aluminum alloys

- Initiation and short crack growth behaviour of environmentally induced cracks in AA5083 H131 investigated across time and length scales

- Residual stress affecting environmental damage in 7075-T651 alloy

- Estimation of environment-induced crack growth rate as a function of stress intensity factors generated during slow strain rate testing of aluminum alloys

- Applied topics

- Corrosion modified fatigue analysis for next-generation damage-tolerant management

- Effect of confined electrolyte volumes on galvanic corrosion kinetics in statically loaded materials

- Quasi-static crack propagation in Ti-6Al-4V in inert and aggressive media

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Editorial

- International Conference on Stress-Assisted Corrosion Damage V (Hernstein, Austria, July 15–20, 2018)

- General topics

- Building environmental history for Naval aircraft

- Discussion of some recent literature on hydrogen-embrittlement mechanisms: addressing common misunderstandings

- When do small fatigue cracks propagate and when are they arrested?

- Computational modeling of pitting corrosion

- Hydrogen-assisted cracking

- Hydrogen effects on mechanical performance of nodular cast iron

- Ductile-brittle transition temperature shift controlled by grain boundary decohesion and thermally activated energy in Ni-Cr steels

- Hydrogen diffusion in low alloy steels under cyclic loading

- Aluminum alloys

- Initiation and short crack growth behaviour of environmentally induced cracks in AA5083 H131 investigated across time and length scales

- Residual stress affecting environmental damage in 7075-T651 alloy

- Estimation of environment-induced crack growth rate as a function of stress intensity factors generated during slow strain rate testing of aluminum alloys

- Applied topics

- Corrosion modified fatigue analysis for next-generation damage-tolerant management

- Effect of confined electrolyte volumes on galvanic corrosion kinetics in statically loaded materials

- Quasi-static crack propagation in Ti-6Al-4V in inert and aggressive media