Abstract

High strength-to-weight ratio Ti-6Al-4V alloy is used in many engineering applications. Its surface oxide film can protect the substrate from interaction with a lot of corrosive environments. Unfortunately, this surface layer can be damaged under mechanical and chemical actions with a consequent reduction in corrosion resistance. A characterization of the untreated alloy under quasi-static loading is here provided. Inert and aggressive environments have been investigated and the influence of the notch geometry of the alloy has also been analyzed.

1 Introduction

Ti-6Al-4V titanium alloy is widespread in aerospace, automotive, maritime, and biomedical applications thanks to its high strength, low density, bioinertness, and corrosion resistance due to its TiO2 surface oxide (Donachie, 1982).

The influence of the tensile strain rate on the mechanical properties of Ti-6Al-4V was highlighted by Wojtaszek et al. (2013). The quasi-static tests performed by Zhou and Chew (2002) in ambient environment pointed out that the strength of the alloy is higher and the ductility is lower with high strain rate because of the transition of the plastic deformation mechanism from dislocation slip to twinning. Strain rate sensitivity gradually decreases during plastic deformation for low strain rate, whereas it is quite constant for the majority of the plastic deformation for high strain rate.

The interesting corrosion performance of Ti-6Al-4V can decrease in some conditions.

Fretting-corrosion is one of the most common causes, for instance, in case of implant loosening. The protective surface layer can be lacerated by the motion of bone or debris against the implant. The implantation of iridium carried out by Meassick and Champaign (1997) can guarantee a continuous passivated state.

Zhou and Bahadur (1995) investigated solution-treated and aged (STA) and annealed Ti-6Al-4V. Their analysis pointed out that above 650°C the alloy produces a porous and slightly adherent surface oxide that decreases the corrosion and erosion resistance in air environment.

In seawater, the laceration of the protective surface layer is due to wear and corrosion. Li et al. (2017) deposited Ti/TiCN coatings by arc ion plating. Higher carbon content gives an increased density of the coating but also a reduction in the friction coefficient and wear rate. However, the last two features have a small decrement while the carbon content is equal or more than 10% at. in Ti/TiCN coatings, in saline solution, or in the atmosphere.

Lee et al. (1999) investigated the effects of the preparation of the material (as-polished or brazed), passivation (nitric acid passivation, heating in air, or aging in deionized water), and immersion time on trace element release in Hank’s ethylenediaminetetraacetic solution. The heated air specimens showed a considerable decrease in release probably due to a very thick oxide. For acid-passivated and water-aged treatments, the brazed specimens had a significant decrease in constituent element release against the as-polished specimens. Furthermore, the release rate dropped throughout 0–8 days.

Titanium is not susceptible to stress corrosion cracking (SCC) in hot saline solution or seawater, whereas its alloy can be. VVAA (1969) and Blackburn et al. (1973) stated that SCC can occur under tensile and not compressive state because tensile stresses open the crack and make possible the contact of the substrate with the aggressive environment, SCC occurs for alloys that produce a passivation layer (like TiO2 for Ti-6Al-4V), some alloying elements such as palladium can decrease the SCC susceptibility of titanium alloys, and the SCC susceptibility of titanium alloys increases in the 500°C–800°C range. Barella et al. (2004) tested precracked specimens in two different NaCl concentrations to simulate maritime conditions. It was observed that a different crack propagation direction depends on the NaCl concentration and strain rate. A 10−6/10−7 s−1 strain rate is needed to promote SCC in artificial seawater. The authors also underlined that the use of synthetic seawater does not take into account the presence of biological species, thermal variations, and motion in the actual sea.

As stated by Bursle and Pugh (1977), the slip-dissolution (film-rupture) model is suitable for the SCC of different alloys in passivating solutions. According to this mechanism, a protective surface layer is locally destroyed by plastic deformation at the crack tip. The unprotected metal is now a small anode, whereas the surface layer is the cathode. For this reason, the strain rate, repassivation rate, corrosive environment, and nature of the dissolving metal are very important points (Sarioglu & Doruk, 1989).

In the Sanderson and Scully (1968) study, SCC susceptibility was observed for Ti-6Al-4V alloy in methanol and methanol-HCl solutions. The consequences of methanol on two Ti-6Al-4V Apollo service propulsion system pressurized fuel tanks were observed by Johnston et al. (1967). Fatigue, constant load, ultimate tensile strength, and cathodic protection tests were carried out. According to this report, the STA alloy is highly notch sensitive if under stress in methanol. Johnston et al. (1967), however, stated also that as little as 1% of water in methanol or cathodic protection is enough to prevent SCC.

A short analysis on the literature about the corrosion fatigue (CF) behavior points out the crack size influence. Gangloff (1985) found that a small crack size accelerates CF growth of 4130 steel in aqueous 3% NaCl solution. The crack geometry, as the author stated, influences the localized transport and reactions for brittle environment-assisted propagation. In general, during short crack propagation, the plastic zone dimensions nearby the crack tips are comparable to crack length. For this reason, linear elastic fracture mechanics cannot explain the phenomenon but it is mandatory an elastic-plastic approach. Wang et al. (2014) suggested a model that takes account of this aspect and Kitagawa effect (the short crack propagation rate depends on the range of cyclic stress rather than the range of the stress intensity factor, which is the driving force in long crack propagation). This model was adopted by the authors to predict the short fatigue crack propagation of Ti-6Al-4V under different stress ratios and stress levels in good agreement with the experimental data.

The Structural Mechanics Laboratory (SMLab) research group of the University of Bergamo has already investigated and is still investigating the SCC and CF behavior of Ti-6Al-4V in air, seawater (3.5% wt. NaCl), and water-methanol solutions (Baragetti & Medolago, 2013; Baragetti et al., 2013; Baragetti, 2014; Baragetti & Villa, 2014, 2015a,b, 2016; Baragetti & Arcieri, 2018). The work presented here is the extension of the study described by Baragetti et al. (2018) and focuses on the quasi-static behavior of untreated Ti-6Al-4V in inert and aggressive environments. The influence of the notch geometry on the strength has been also analyzed.

This paper is based on the addition of a single replicate data point to the publication of Baragetti et al. (2018). In the Baragetti et al. (2018) study, an investigation about the behavior of the untreated alloy in inert and aggressive environments was carried out. In particular, a further notched specimen in pure methanol was tested in this paper to compare the outcomes with those of Baragetti et al. (2018) and more deeply understand the influence of the strain rate and contamination of the moisture, whose contribution in corrosion phenomena was pointed out by Johnston et al. (1967) for methanol.

2 Materials and methods

This study is the extension of the analysis shown by Baragetti et al. (2018). Here, all the tested specimens were produced from a Ti-6Al-4V raw plate supply and were not subjected to any treatment. The mechanical properties of the specimens are summarized in Table 1.

Mechanical properties (Baragetti et al., 2018).

| Ultimate tensile strength (MPa) | Yield stress (MPa) | Young’s modulus (MPa) | Elongation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1000–1100 | 958–1050 | 110,000 | 16 |

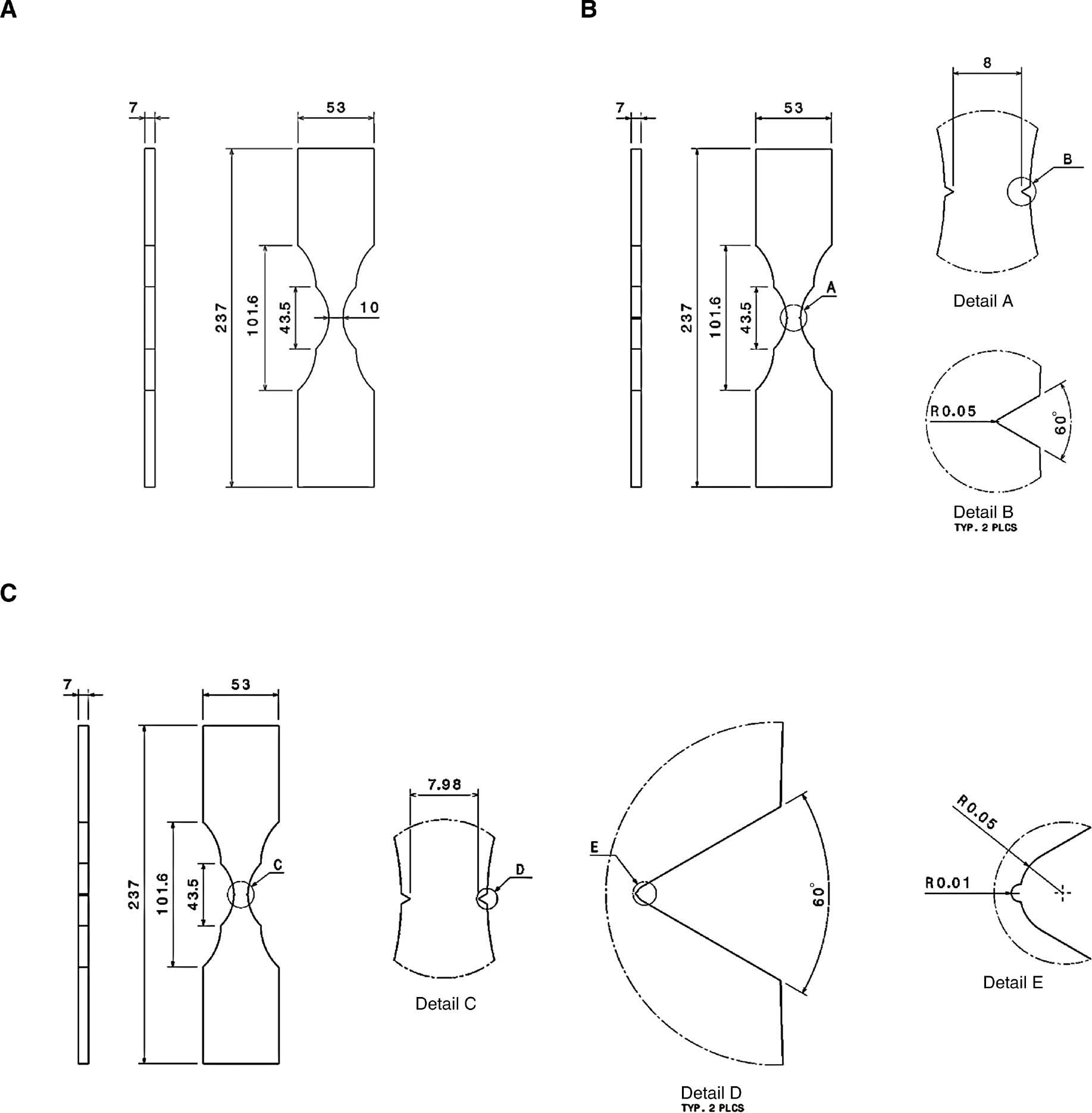

In the Baragetti et al. (2018) study, three different types of specimens were investigated: “smooth specimen” (unnotched; Figure 1A), “electrical discharge machining (EDM)-notched specimen” (Figure 1B), and “EDM+sharp knife-notched specimen” (Figure 1C). For the EDM-notched specimen, two notches (one left and one right) were carried out by means of EDM. For the EDM+sharp knife-notched specimen, two further notches (one left and one right) were carried out by means of a sharp knife on the previously described EDM notches. The surface nearby the central zone of the specimen was polished with grit paper from 600 to 1200 grit. Polishing with 3 μm diamond paste followed by cleaning with acetone was carried out. Abrasive blasting operations on the gripping points of the specimens were carried out to reach more friction. Aluminum tape pieces were placed so that they inhibit the sliding of the specimen in the machine. Some strain gauges were placed during testing to monitor the stress on the specimen (a load cell was also used). The strain gauges were not placed in the central zone during the tests in aggressive environments to avoid contamination.

Dimensions of the specimens: (A) smooth specimen, (B) EDM-notched specimen, and (C) EDM+sharp knife-notched specimen (Baragetti et al., 2018).

A tank for the containment of the aggressive environment was designed and modified by Baragetti et al. (2018).

The local stress concentration factors (SCF) were calculated (Table 2) by means of linear elastic finite-element modeling. The model consists of plane-stress elements and the maximum principal stress was used during the calculation of SCF.

The quasi-static tests were carried out by means of a testing machine designed by the SMLab research group. The machine was made of a threaded rod tensile system and rolling bearing hinge grips, which avoid parasite bending stresses. The load was applied by means of a hydraulic jack.

Now, a further EDM-notched specimen with the mechanical properties in Table 2 was tested in pure methanol with a completely filled and sealed tank. The objective is to compare the result of this test with the experiment of Baragetti et al. (2018) and to understand the effects of immersion time, strain rate, and contamination by moisture.

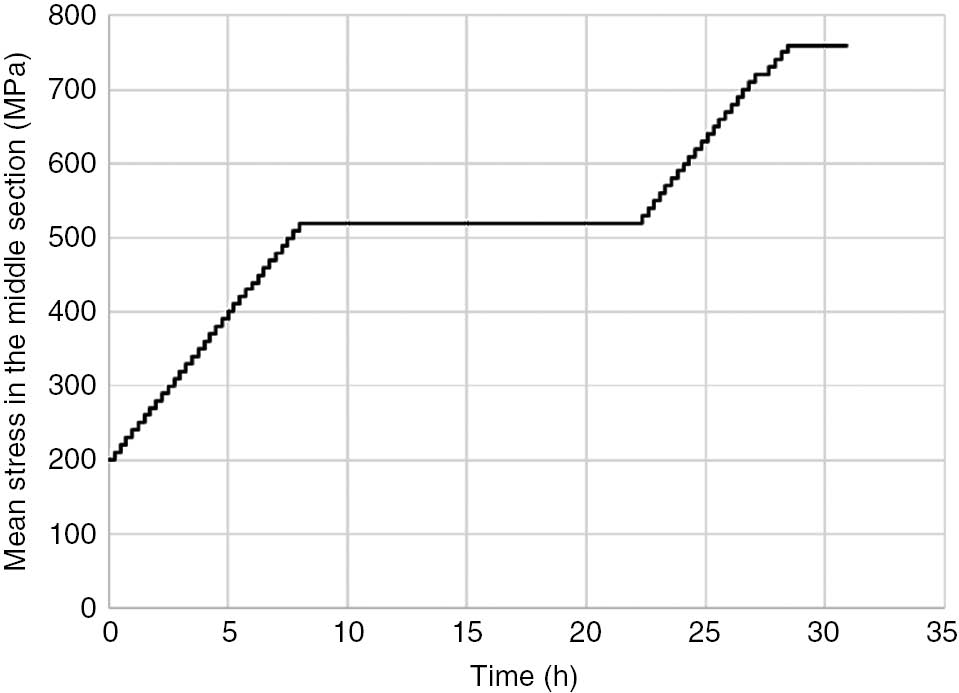

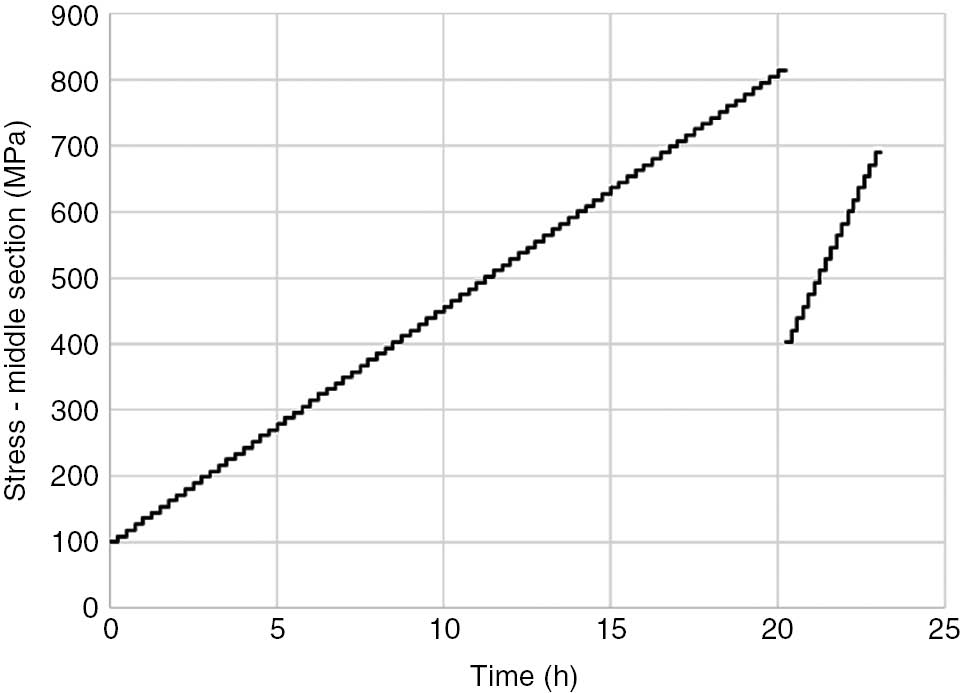

The loading history is reported in Figure 2. Each load block was set to 15 min with some exceptions. The load block 520 MPa took 14 h 20 min (the specimen was under stress all night). Actually, after this period, the stress read in the middle section was 440 MPa. The load block 720 MPa took 35 min and the load block 760 MPa took 2 h 30 min. At this time, the rupture occurred.

Loading history.

3 Results and discussion

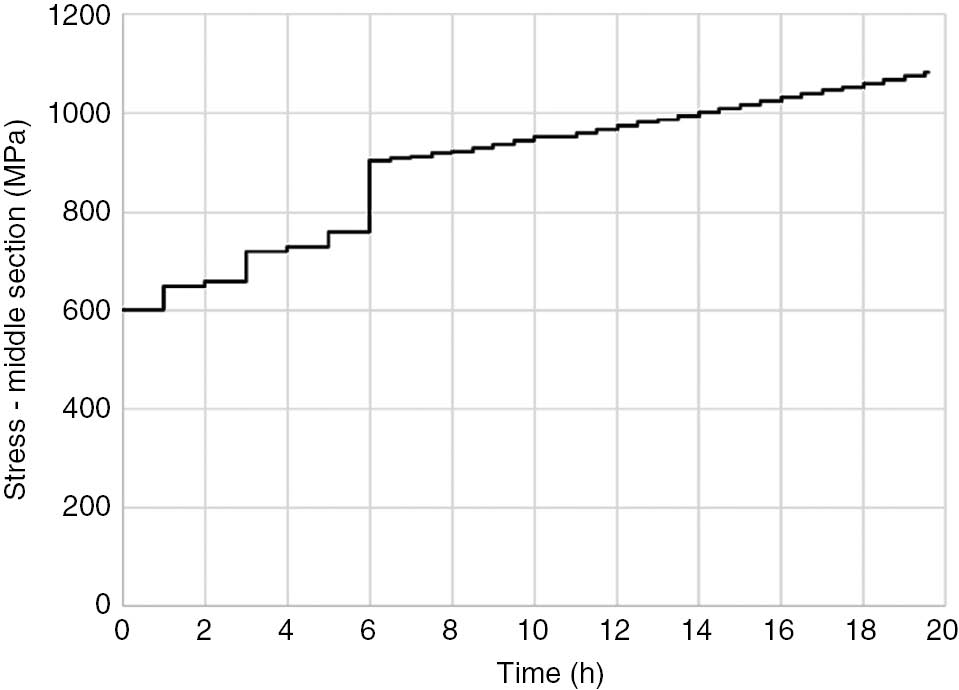

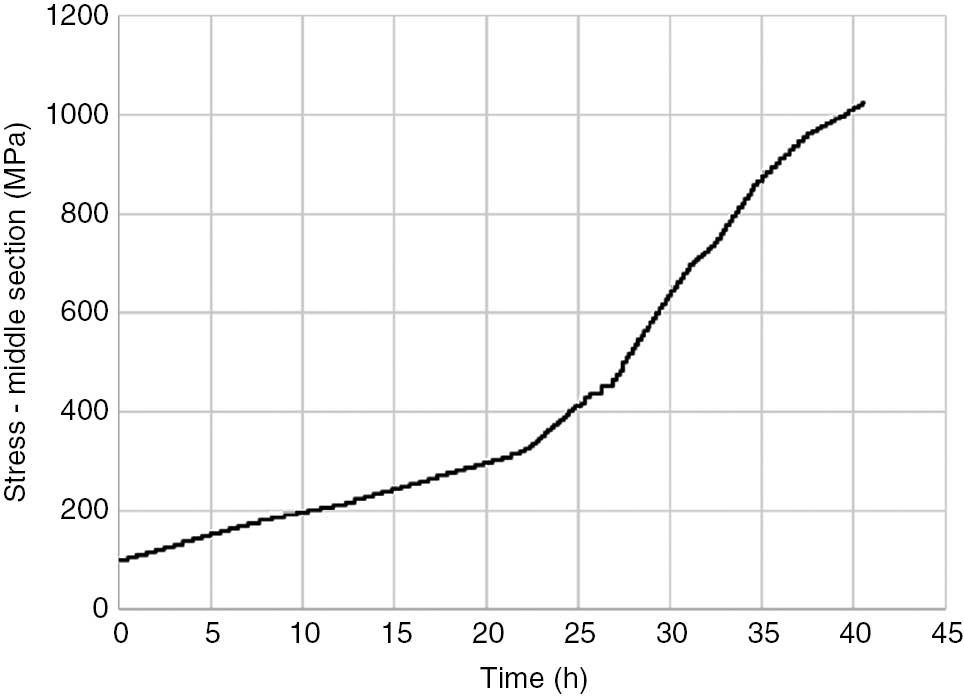

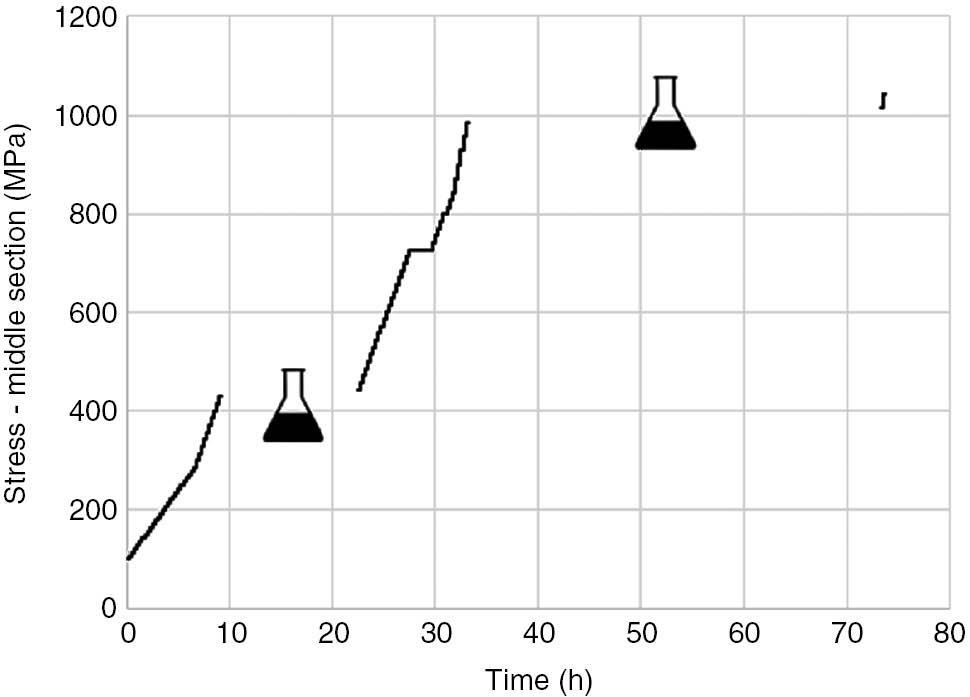

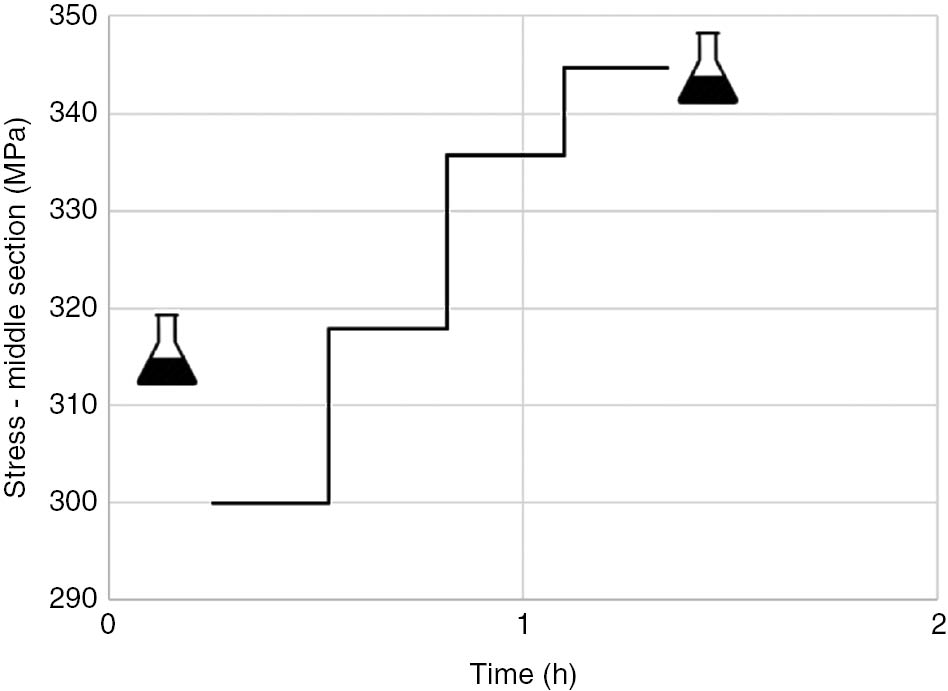

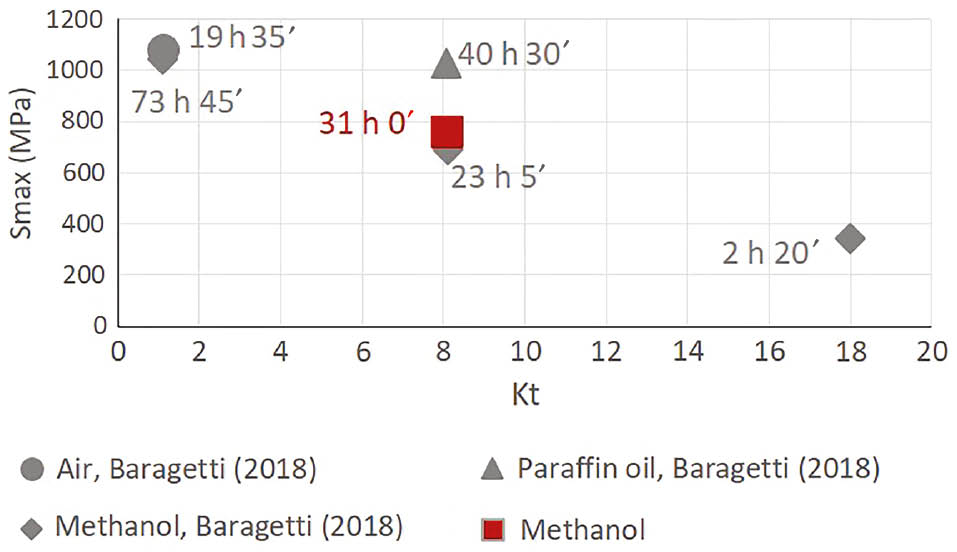

Quasi-static tests on untreated Ti-6Al-4V are presented by Baragetti et al. (2018). Table 3 summarizes the results. The loading history for each specimen can be seen in Figures 3–7. In the tests of Figures 6 and 7, the specimen was immersed in the environment during the pauses in unloaded conditions. Figure 8 summarizes the results.

Results of Baragetti et al. (2018).

| No. | Type | Environment | Experimental stress to failure (MPa) | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Smooth | Air | 1083 | Equal to ultimate tensile strength |

| 2 | EDM | Paraffin oil | 1025 | Equal to ultimate tensile strength |

| 3 | EDM | Pure methanol | 689 | Two phases (two different tanks for the containment of the environment) |

| Methanol removed whenever the test was paused | ||||

| 4 | Smooth | Pure methanol | 1042 | Immersion in methanol also during the stops |

| 5 | EDM+sharp knife | Pure methanol | 345 | Completely sealed and filled tank (no contamination with air) |

Loading history, test 1 of Table 3, from Baragetti et al. (2018).

Loading history, test 2 of Table 3, from Baragetti et al. (2018).

Loading history, test 3 of Table 3, from Baragetti et al. (2018).

Loading history, test 4 of Table 3, from Baragetti et al. (2018).

Loading history, test 5 of Table 3, from Baragetti et al. (2018).

Results.

From these results, it could be concluded that there are no appreciable differences for smooth and EDM-notched specimens in inert environment, SCF Kt=1.1 and 8.1. Furthermore, methanol is not aggressive on smooth specimens of untreated Ti-6Al-4V. Only the combination of methanol/very sharp notch seems to be harmful.

As consequence of the test of the EDM-notched specimen in methanol (third test in Table 3), the authors made the following considerations:

The immersion time of the specimen in methanol is an important point because the environment has more time to corrode the alloy.

As small contamination of the environment by moisture or components of the sealant of the tank is sufficient to decrease the aggressiveness of the methanol as stated also by Johnston et al. (1967).

The test of the sharply notched specimen in methanol (fifth test in Table 3) pointed out the aggressiveness of the methanol combined to a sharp notch but also a possible contribution of the strain rate as the rupture occurred after a very long load block (1 h). At the end of this load block, the load on the specimen was 0 MPa, and when an increment of load was attempted, failure occurred. This consideration was also in accordance with the Zhou and Chew (2002) study.

For the further test presented in this paper, the rupture occurred at 760 MPa after 31 h. The tank was completely sealed and filled with methanol so no contamination by moisture occurred. The stress was comparable to the third test of Table 3 of Baragetti et al. (2018). The time to failure was instead higher. The reason could be that in the Baragetti et al. (2018) study the tank for the containment of the methanol was substituted during the test. During the time necessary for the substitution of the tank, the specimen and in particular the notch was in contact with methanol because no cleaning operations were carried out. Unfortunately, the authors did not measure this time.

The rupture of the specimen occurred during a very long load step and after a long immersion time so we conclude that the considerations made for the experiments of Baragetti et al. (2018) could be valid.

4 Conclusions

An EDM-notched specimen was again tested in pure methanol by quasi-static loading. Unlike the corresponding test presented by Baragetti et al. (2018), the tank was completely filled and sealed. The result of the test was similar to the previous test in stress but not in time. The specimen tested by Baragetti et al. (2018) was not cleaned during the tank substitution so the specimen remained in contact with methanol. The way in which the rupture occurred could imply the influence of the strain rate, immersion time, and possible contamination on the quasi-static behavior.

References

Baragetti S. Notch corrosion fatigue behavior of Ti-6Al-4V. Materials 2014; 7: 4349–4366.10.3390/ma7064349Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Baragetti S, Arcieri EV. Corrosion fatigue behavior of Ti-6Al-4V: chemical and mechanical driving forces. Int J Fatigue 2018; 112: 301–307.10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2018.02.033Search in Google Scholar

Baragetti S, Medolago A. Load and environmental effects on the corrosion behavior of a Ti-6Al-4V. Key Eng Mater 2013; 525–526: 501–504.10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.525-526.501Search in Google Scholar

Baragetti S, Villa F. SCC and corrosion fatigue characterization of a Ti-6Al-4V alloy in a corrosive environment – experiments and numerical models. Fract Int Struct 2014; 8: 84–94.10.3221/IGF-ESIS.30.12Search in Google Scholar

Baragetti S, Villa F. Corrosion fatigue of high-strength titanium alloys under different stress gradients. J Miner Met Mater S 2015a; 67: 1154–1161.10.1007/s11837-015-1360-5Search in Google Scholar

Baragetti S, Villa F. Quasi-static behavior of notched Ti-6Al-4V specimens in water-methanol solution. Corros Rev 2015b; 33: 477–485.10.1515/corrrev-2015-0041Search in Google Scholar

Baragetti S, Villa F. Crack propagation models: numerical and experimental results on Ti-6Al-4V notched specimens. Fatigue Fract Eng Struct 2016; 40: 1276–1283.10.1111/ffe.12561Search in Google Scholar

Baragetti S, Foglia C, Gerosa R. Fatigue crack nucleation and growth mechanisms for Ti-6Al-4V in different environments. Key Eng Mater 2013; 525–526: 505–508.10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.525-526.505Search in Google Scholar

Baragetti S, Borzini E, Arcieri EV. Effects of environment and stress concentration factor on Ti-6Al-4V specimens subjected to quasi-static loading. Proc Struct Int 2018; 12: 173–182.10.1016/j.prostr.2018.11.097Search in Google Scholar

Barella S, Mapelli C, Venturini R. Investigation about the stress corrosion cracking of Ti-6Al-4V. Metall Sci Technol 2004; 22: 19–26.Search in Google Scholar

Blackburn MJ, Feeney JA, Beck TR. Stress-corrosion cracking of titanium alloys. In: Advances in Corrosion Science and Technology, vol. 3. New York: Plenum Press, 1973: 67–292.10.1007/978-1-4615-8258-8_2Search in Google Scholar

Bursle AJ, Pugh EN. An evaluation of current models for the propagation of stress-corrosion cracks. TMS Paper Selection, 1977: 18–47.Search in Google Scholar

Donachie MJ. Titanium and titanium alloys source book. Metals Park: American Society of Metals, 1982.Search in Google Scholar

Gangloff RP. Crack size effects on the chemical driving force for aqueous corrosion fatigue. Metall Trans A 1985; 16: 953–969.10.1007/BF02814848Search in Google Scholar

Johnston RL, Johnson RE, Ecord GM, Castner WL. Stress-corrosion cracking of Ti-6Al-4V alloy in methanol. NASA Technical Note TN D-3868, 1967.Search in Google Scholar

Lee TM, Chang E, Yang CY. Effect of passivation on the dissolution behavior of Ti6Al4V and vacuum-brazed Ti6Al4V in Hank’s ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid solution. Part I. Ion release. J Mater Sci Mater Med 1999; 10: 541–548.10.1023/A:1008916314329Search in Google Scholar

Li JL, Cai GY, Zhong HS, Wang YX, Chen JM. Tribological properties in seawater for Ti/TiCN coatings on Ti6Al4V alloy by arc ion plating with different carbon contents. Rare Met 2017; 36: 858–864.10.1007/s12598-016-0802-8Search in Google Scholar

Meassick S, Champaign H. Noble metal cathodic arc implantation for corrosion control of Ti-6Al-4V. Surf Coat Technol 1997; 93: 292–296.10.1016/S0257-8972(97)00063-7Search in Google Scholar

Sanderson G, Scully JC. The stress-corrosion cracking of Ti alloys in methanolic solutions. Corros Sci 1968; 8: 541–548.10.1016/S0010-938X(68)80008-3Search in Google Scholar

Sarioglu F, Doruk M. Elastic-plastic fracture mechanics analysis of SCC in a low strength steel. In: Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Fracture, Houston, TX, March 20–24, 1989: 259–265.10.1016/B978-0-08-034341-9.50037-1Search in Google Scholar

VVAA. Proceedings of Conference – Fundamental Aspects on Stress Corrosion Cracking, September 11–15, 1967, Ohio, USA, ed. NACE, 1969.Search in Google Scholar

Wang K, Wang F, Cui W, Hayat T, Ahmad B. Prediction of short fatigue crack growth of Ti-6Al-4V. Fatigue Fract Eng M 2014; 37: 1075–1086.10.1111/ffe.12177Search in Google Scholar

Wojtaszek M, Sleboda T, Czulak A, Weber G, Hufenbach WA. Quasi-static and dynamic tensile properties of Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Arch Metall Mater 2013; 58: 1261–1265.10.2478/amm-2013-0145Search in Google Scholar

Zhou J, Bahadur S. Erosion-corrosion of Ti-6Al-4V in elevated temperature air environment. J Wear 1995; 186–187: 332–339.10.1016/0043-1648(95)07161-XSearch in Google Scholar

Zhou W, Chew KG. The rate dependent response of a titanium alloy subjected to quasi-static loading in ambient environment. J Mater Sci 2002; 37: 5159–5165.10.1023/A:1021085026220Search in Google Scholar

©2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Editorial

- International Conference on Stress-Assisted Corrosion Damage V (Hernstein, Austria, July 15–20, 2018)

- General topics

- Building environmental history for Naval aircraft

- Discussion of some recent literature on hydrogen-embrittlement mechanisms: addressing common misunderstandings

- When do small fatigue cracks propagate and when are they arrested?

- Computational modeling of pitting corrosion

- Hydrogen-assisted cracking

- Hydrogen effects on mechanical performance of nodular cast iron

- Ductile-brittle transition temperature shift controlled by grain boundary decohesion and thermally activated energy in Ni-Cr steels

- Hydrogen diffusion in low alloy steels under cyclic loading

- Aluminum alloys

- Initiation and short crack growth behaviour of environmentally induced cracks in AA5083 H131 investigated across time and length scales

- Residual stress affecting environmental damage in 7075-T651 alloy

- Estimation of environment-induced crack growth rate as a function of stress intensity factors generated during slow strain rate testing of aluminum alloys

- Applied topics

- Corrosion modified fatigue analysis for next-generation damage-tolerant management

- Effect of confined electrolyte volumes on galvanic corrosion kinetics in statically loaded materials

- Quasi-static crack propagation in Ti-6Al-4V in inert and aggressive media

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Editorial

- International Conference on Stress-Assisted Corrosion Damage V (Hernstein, Austria, July 15–20, 2018)

- General topics

- Building environmental history for Naval aircraft

- Discussion of some recent literature on hydrogen-embrittlement mechanisms: addressing common misunderstandings

- When do small fatigue cracks propagate and when are they arrested?

- Computational modeling of pitting corrosion

- Hydrogen-assisted cracking

- Hydrogen effects on mechanical performance of nodular cast iron

- Ductile-brittle transition temperature shift controlled by grain boundary decohesion and thermally activated energy in Ni-Cr steels

- Hydrogen diffusion in low alloy steels under cyclic loading

- Aluminum alloys

- Initiation and short crack growth behaviour of environmentally induced cracks in AA5083 H131 investigated across time and length scales

- Residual stress affecting environmental damage in 7075-T651 alloy

- Estimation of environment-induced crack growth rate as a function of stress intensity factors generated during slow strain rate testing of aluminum alloys

- Applied topics

- Corrosion modified fatigue analysis for next-generation damage-tolerant management

- Effect of confined electrolyte volumes on galvanic corrosion kinetics in statically loaded materials

- Quasi-static crack propagation in Ti-6Al-4V in inert and aggressive media