Abstract

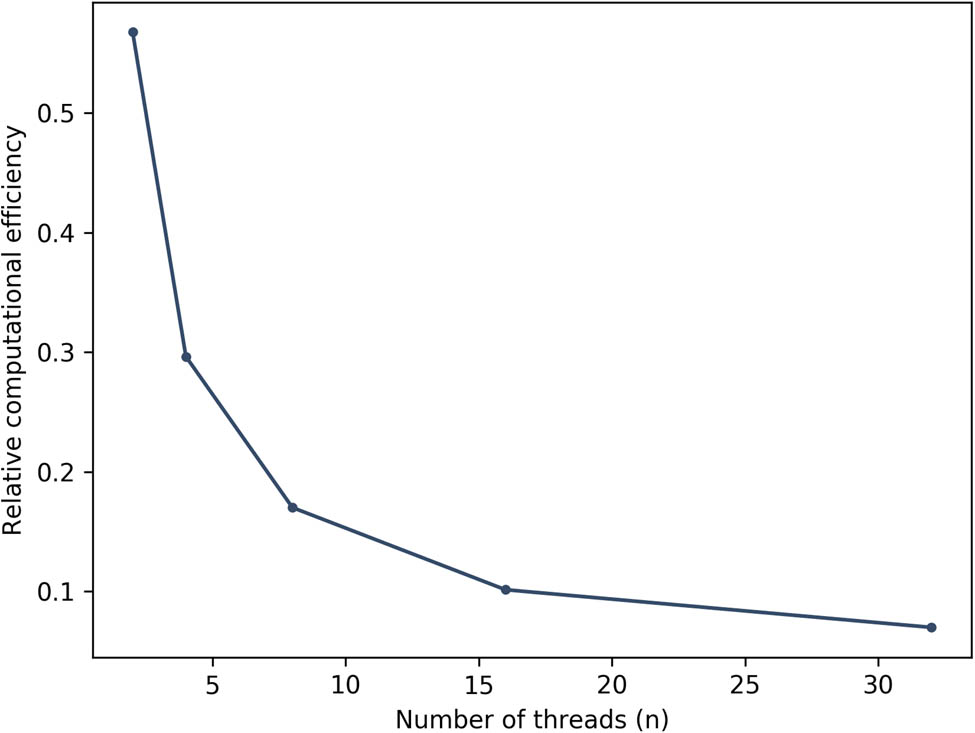

To meet various requirements of the future deep space missions of China, State Key Laboratory of Astronautic Dynamics constructs a new orbit determinatin software with parallel observations process. By using 32 threads, the computational efficiency per iteration (including spacecraft’s integration) could be promoted to 10 times as that of single-threaded orbit determination. Suppose the number of observations is

1 Introduction

Mars has a very close orbit to Earth in the solar system. The similarities and differences between Mars and Earth give Mars high scientific values such as searching for water and life, detecting dust ring of Mars (Liu and Jürgen 2020). Mars has always been a hot spot in deep space. There are continuous Mars exploration missions in the last two decades, and it reaches a small climax in 2020. The United Arab Emirates, China and the United States (US) choose a very close launch window to start their Mars exploration missions, and all the three missions succeed in the end. Tianwen-1, including an orbiter, a lander and rover, is the first attempt of China to explore Mars. Apart from the scientific goals, Tianwen-1 also tries to answer three ultimate questions: 1) investigating life activities on Mars; 2) investigating the evolution of Mars and comparing it with other terrestrial planets; 3) investigating the prospects of terraform Mars and immigrating to Mars.

Since tracking, maneuver calculation and many applications of spacecraft rely on accurate positions and velocities, orbit determination has been indispensable to space missions. According to requirements of space missions, different space mission centers develop their own orbit determination software. Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) developed Orbit Determination Program (ODP) in 1960s (Moyer 1971), Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) developed NASA’s state-of-the-art parameter estimation and precision orbit determination system (GEODYN) in 1970s and Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES) developed Géodésie par Intégrations Numériques Simultanées (GINS) in 1960s (Marty 2013). With the development of space missions, some space mission centers reframe or even rewrite their orbit determination softwares based on new computer technologies to meet the new needs of space missions. GEODYN was redesigned and updated to GEODYN-II in 1980s (Pavlis et al. 2013). JPL started to construct the Mission analysis, Operation and Navigation Toolkit Environment (MONTE) by the end of 20th century (Flanagan et al. 2001, Sunseri et al. 2012). MONTE has been successfully applied to Cassini and MESSENGER missions. Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) initiated the development of the Deep-space Multi-Object Orbit Determination System (DMOODS) in 2006, and it was applied in Hayabusa2’s asteroid proximity mission (Hiroshi et al. 2020).

Xi’an Satellite Control Center (XSCC) built its first-generation orbit determination software in 1970s. The first generation orbit determination software is based on analytical solutions of perturbations. However, the complexity of codes is high, but the accuracy and efficiency is not enough. Since 1990s, Jisheng Li started the construction of the second-generation orbit determination software of XSCC, Xi’an Satellite Control Center Precise Orbit Determination System (XPODS), which has supported almost all the earth satellite missions in XSCC. XPODS is programmed in Fortran and based on numerical integration of accurate dynamic models. Observations include Ranging, Doppler, azimuth and elevation.

Considering the demands of the future deep space missions of China, State Key Laboratory of Astronautic Dynamics started to reframe and construct a new orbit calculation software in 2016. All the algorithm modules are rewritten in C and only rely on C standard library. The software adopts a complete modular design. Not only the dynamic models for the same perturbation is selectable but also the integrator and almost all the functional modules are selectable and easily extensible.

In the following sections of this article, orbit determination for the Earth-Mars transfer phase and the Mars-orbiting phase are discussed. A parallel observation process algorithm based on Givens transformation (Givens 1958) and the calculation of the best parallel computation parameter are introduced. Then two comparisons are mainly discussed, (1) orbit determination accuracies of the Earth-Mars transfer phase, the Mars-orbiting phase and the former Chang’E missions and (2) orbit determination accuracies under different tracking modes.

2 Data description

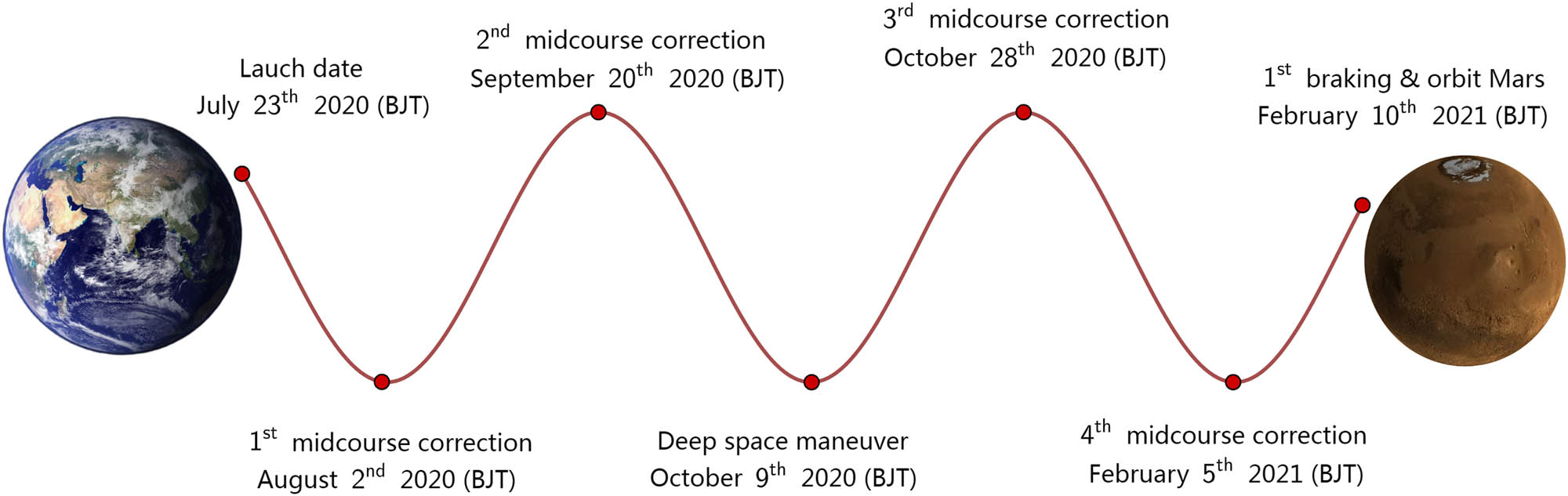

Tianwen-1 was launched on July 23, 2020, and arrived at Mars on February 10, 2021. Before arriving at Mars, four midcourse trajectory corrections and one deep space maneuver were performed. The flight from Earth to Mars is shown in Figure 1.

The flight of Tianwen-1 from Earth to Mars.

The landing phase of Tianwen-1 started with a parachute separation and ended with a soft touchdown (Huang et al. 2022, Guo et al. 2022). Tianwen-1 accomplished the landing successfully on May 15, 2021. A hybrid-matching between the optical obstacle avoidance sensor and the digital orthophoto map was used for the precise positioning of the lander (Wang et al. 2022).

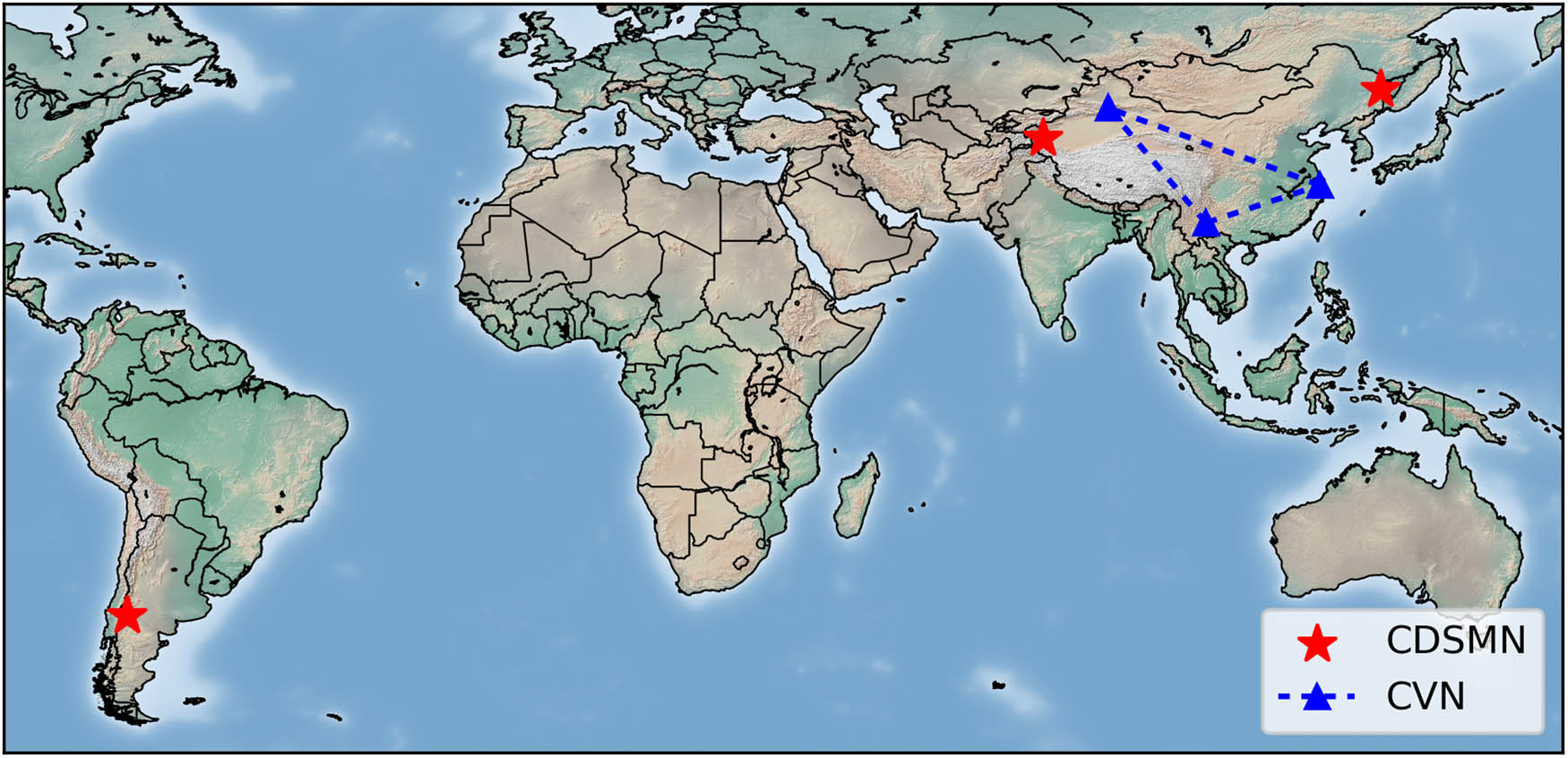

There are four types of observations in Tianwen-1 mission, including 2-way Ranging, 2-way Doppler, Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI) delay and delay rate. Two-way Ranging and 2-way Doppler are generated from China’s deep space monitoring network (CDSMN), which is operated by Xi’an Satellite Control Center (XSCC). VLBI delay and delay rate are generated from China’s VLBI network (CVN), which is operated by Shanghai Astronomical Observatory. The geographical distribution of the stations of CDSMN and CVN is shown in Figure 2.

The geographical distribution of CDSMN and CVN.

CDSMN consists of three monitoring stations. One in Kashgar of northwest China (KS, 35 m antenna), one in Jiamusi of northeast China (JMS, 66 m antenna) and one in Argentina of South America (AGT, 35 m antenna). Three VLBI stations of CVN are used for tracking and measuring Tianwen-1. One in Shanghai Tianma of southeast China (SHAN, 65 m antenna), one in Urumqi of northwest China (ULMQ, 25 m antenna) and one in Kunming of southwest China (KUNM, 40 m antenna).

To evaluate the accuracy of orbit determination, two data samples are selected, one for the Earth-Mars transfer phase and one for the Mars-orbiting phase. For the transfer phase, observations of 6 days are selected, from October 13, 2020 to October 19, 2020. At that time, Tianwen-1 has just finished the deep space maneuver and prepared for the third midcourse trajectory correction. For the Mars orbit, observations of 4 days are selected, from May 1, 2021 to May 5, 2021. At that time, the imaging of the landing area was just completed, and Zhurong (the lander of Tianwen-1) was preparing for landing on the Mars.

The calculation of light time follows the algorithms described by Moyer (2000). The time tag of observation is recorded as UTC time by the CDSMN and the CVN. Meanwhile the input of planetary ephemeris is barycentric dynamic time (TDB). The transformation between TDB and UTC follows the algorithms described by Petit and Luzum (2010).

3 Dynamic models

The flight of Tianwen-1 can be roughly divided into three phases: (1) cislunar space phase, (2) Earth-Mars transfer phase and (3) Mars-orbiting phase. Since Tianwen-1 leaves the earth at very high speed, the first phase of the flight is short. The dynamic models of the transfer phase and the Mars-orbiting phase will be mainly discussed in this section.

In the transfer phase, Tianwen-1 circles the barycenter of the solar system. The main forces are the solar radiation pressure and the gravity of the Sun and eight major planets. Tianwen-1 keeps getting away from the Sun in the transfer phase, and the solar radiation pressure is inversely proportional to the square of distance between the spacecraft and the Sun. The semi-major axis of Mars circling the barycenter of the solar system is about 1.5 AU, and the solar radiation pressure gradually drops to as half strong as that at the cislunar space phase.

After entering the Mars orbit, at least another two perturbations should be taken into consideration: (1) the non-spherical gravitational perturbation of the Mars and (2) n-body perturbation of the Phobos and the Deimos. Since the atmosphere density of the Mars is about 100 times thinner than that of Earth and the semi-axis of Tianwen-1 is over 32,000 km, the atmospheric drag is negligible.

Working Group on Cartographic Coordinates and Rotational Elements of International Astronomical Union (IAU) provides orientation model and parameters for major planets in the solar system (Seidelmann et al. 2007),

With Pathfinder data, periodic variations in spin, nutation for a free core wobble and polar motion are added to Mars orientation (Folkner et al. 1997),

Supposed that the node of the Mars mean orbit and ICRF x–y plane is A, the node of the Mars mean orbit and the Mars true equator of date is B,

By using different Mars orientation model and parameters, different Mars gravity fields are estimated with different observations. Therefore, the cross use of the Mars gravity fields and the Mars orientation models would lead to an error in the calculation of non-spherical perturbation. Several Mars gravity fields and their corresponding orientation models are listed in Table 1.

Mars gravity fields and their corresponding Mars orientation models

| Gravity model | Data | Mars orientation | Maximum order |

|---|---|---|---|

| GMM-1 (Smith et al. 1993) | Mariner-9, Viking Orbiter-1, Viking Orbiter-2 | IAU model |

|

| MGS75b (Smith et al. 1999) | Mariner-9, Viking Orbiter-1 | IAU model |

|

| Viking Orbiter-2, Mars Global Surveyor | |||

| GMM-2 | Mars Global Surveyor | IAU model |

|

| MGS95J (Konopliv et al. 2006) | Mars Global Surveyor, Mars Odyssey | Pathfinder model |

|

| Pathfinder, Viking Lander | |||

| JGMRO120D (Konopliv et al. 2016) | Mars Global Surveyor, Mars Odyssey | Pathfinder model |

|

| Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, Pathfinder | |||

| Viking Lander, MER Opportunity | |||

| GMM-3 (Genova et al. 2016) | Mars Global Surveyor, Mars Odyssey | Pathfinder model |

|

| Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter |

4 Parallel observations process

4.1 Designs and algorithms of parallel observations process

For traditional Earth satellites, parallel computing is not necessary since the computation requirements are not heavy for current computers. However, a longer tracking duration is needed for the Earth-Mars transfer phase to avoid that the arc around the barycenter of the solar system is too short. In addition, the complexity of observation model for deep space is much higher than that for Earth satellites. Thus, parallel computing is a solution to the low computational efficiency of single-threaded deep space orbit determination. To realize the parallel computing and data compression, Givens transformation is used. Taking careful consideration of load balancing and synchronization among different threads, parallel observations process is designed as follows.

Supposed that

The correction of state

Divide

The Givens transformation is selected to deal with the process of observations. Suppose that

By allocating the calculation of

The amount of computation in each thread is roughly the same if the entire observations are divided equally into different data blocks. The information of observations is compressed into a smaller upper matrix

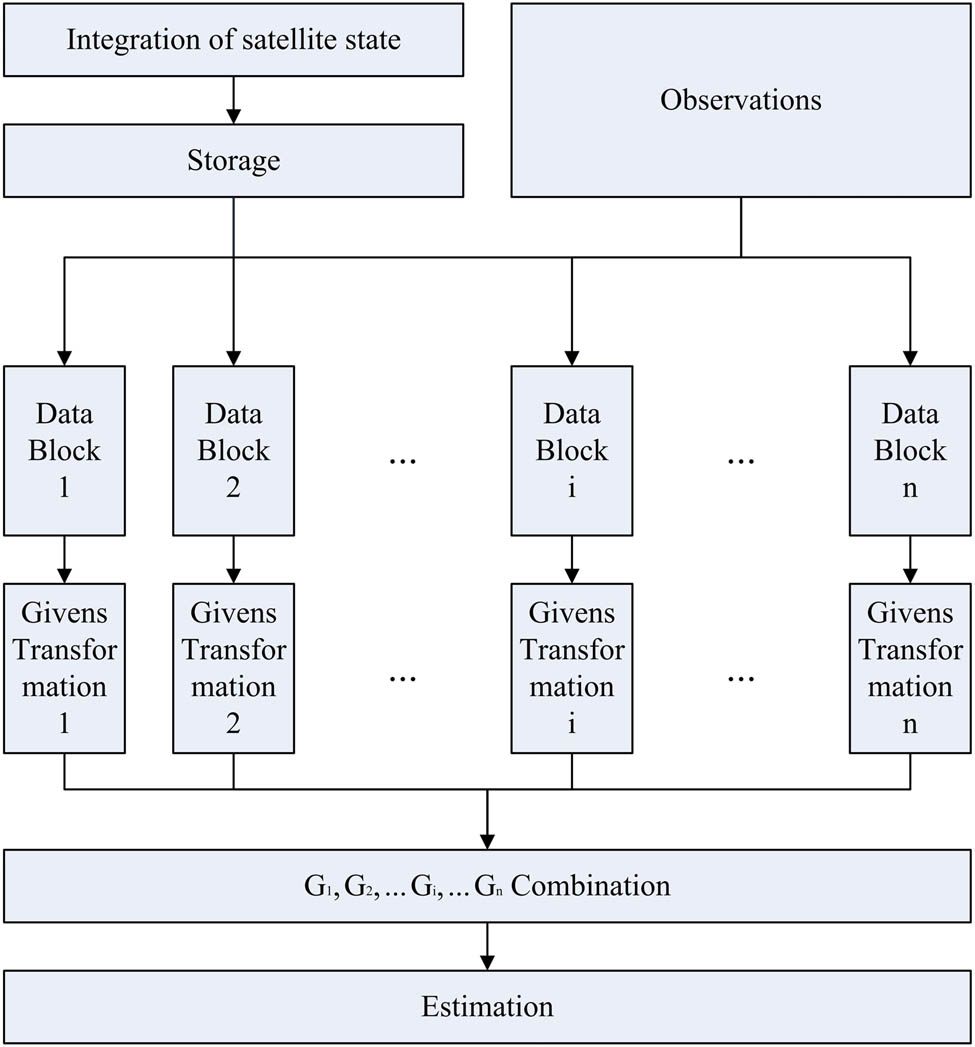

Since parallel observations process divides the entire observations into data blocks and puts different data blocks into different threads, threads will need spacecraft’s states at different time points. To fulfill this requirement, state series cover the entire observation time period should be integrated and stored in memory before the observation process. In each thread, a small matrix is calculated, and matrices from different threads should be fused. The architecture of parallel observations process with one-step fusion is shown in Figure 3.

Parallel observations process with one-step fusion of matrices.

Suppose that the number of observations is

the best

If the number of the estimated parameters is large, and the model of observation is simple,

If the number of threads

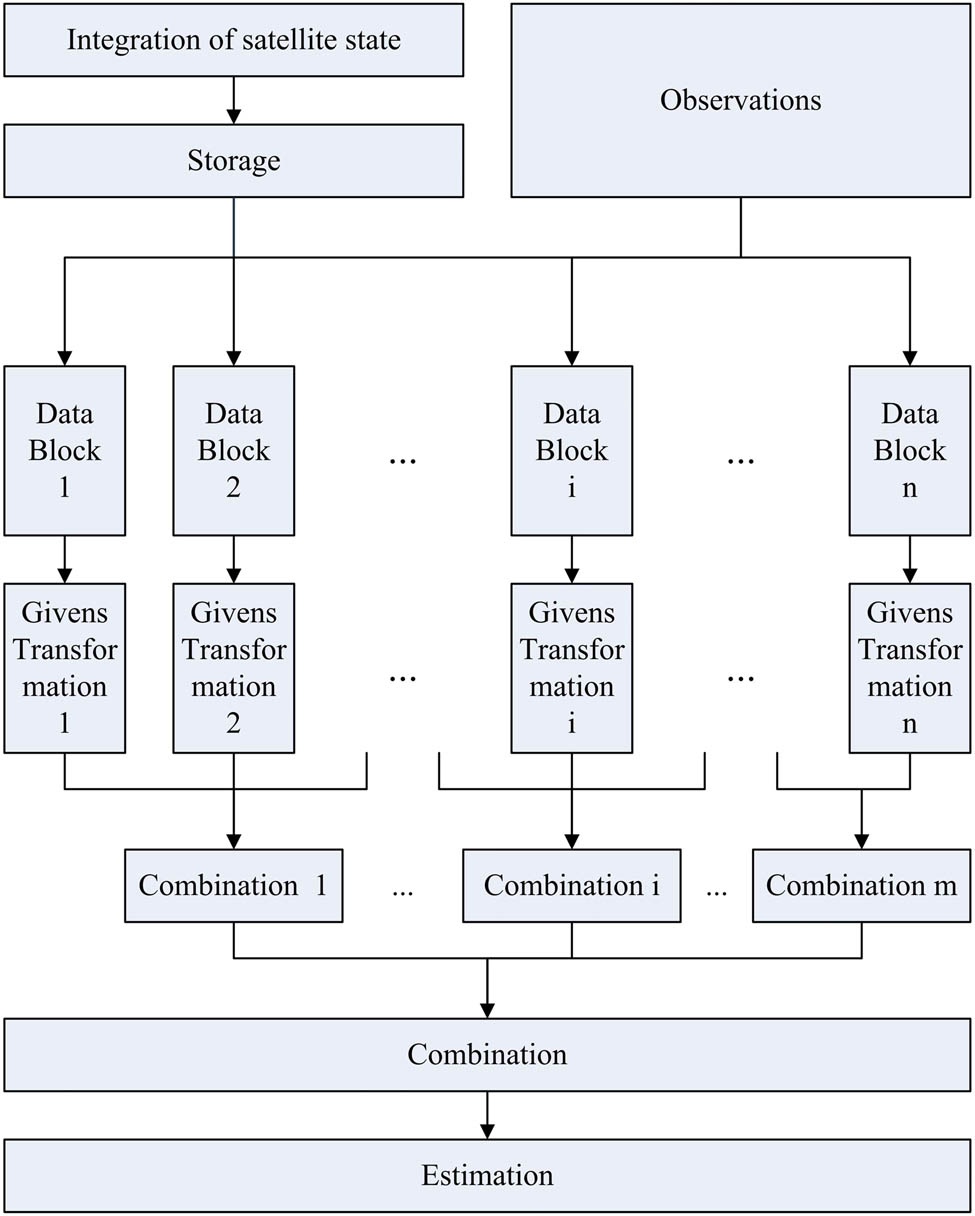

Parallel observations process with two-step matrices fusion.

Suppose that

it has

The best

With the most proper parameters, the computation amount

When

4.2 Tests of parallel observations process

Except the high performance computers, the number of cores for most computers is very limited, and

The configuration of the test environment

| Item | Content |

|---|---|

| CPU | Intel Xeon Gold 6130 |

| Frequency | 2.10 GHz |

| Memory | 128 GB |

| Number of processors | 2 |

| Cores per processor | 16 |

| Number of observations (

|

6,522 |

| Number of estimated parameters (

|

6 |

To reduce the differences caused by the random fluctuations of CPU performance, for each setting value of

The elapsed time per iteration with parallel orbit determination (including spacecraft’s state integration), setting the elapsed time per iteration with single-threaded orbit determination as 1.

It can be found that the elapsed time drops less with the increase of the number of threads. When the number of threads reaches 32, the elapsed time reduced to about 0.1 times as that of the single-threaded orbit determination.

5 Results and analysis

The accuracy of orbit determination is mainly analyzed in this section, and the root mean square (RMS) of the postfit residuals is used to assess the quality of different observations. The orbit determination strategies for the Earth-Mars transfer phase and the Mars-orbiting phase are presented in Table 3. Apart from the differences of dynamic models, the weight of observations changes a little. The effect of Doppler is stronger for the Mars-orbiting phase, while the effect of VLBI is stronger for the Earth-Mars transfer phase.

Strategies of Tianwen-1 orbit determination

| Phases of flight | Item | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Transfer phase | Reference system | Barycentric Celestial Reference System (BCRS) |

| N-body perturbation | Sun and eight major planets from DE430 (Willimas et al. 2013) | |

| Solar radiation pressure | Fixed area-mass-ratio | |

| Earth tropospheric correction | Saastamoinen (Saastamoinen 1972) with NMF mapping function | |

| Parameters to solve | State of Tianwen-1 | |

| Solar radiation pressure coefficient | ||

| Systematic error of ranging for each tracking arc | ||

| Weight of observations | 1 m for ranging | |

| 1 mm/s for Doppler | ||

| 3 cm for VLBI delay | ||

| 1 mm/s for VLBI delay rate | ||

| Mars-orbiting phase | Inertial reference system | Mars-centered ICRS (MCRS) |

| Mars body-fixed reference system | Pathfinder model with updated parameters (Konopliv et al. 2006, 2011) | |

| Martian gravity field | MRO120D (Konopliv et al. 2016) | |

| Mars solid tidal perturbation |

|

|

| N-body perturbation | Sun and eight major planets from DE430 (Willimas et al. 2013) | |

| Phobos and Deimos from SPICE (Semenov and Acton 2007) | ||

| Solar radiation pressure | Fixed area–mass ratio | |

| Earth tropospheric correction | Saastamoinen (Saastamoinen 1972) with NMF mapping function | |

| Parameters to solve | State of Tianwen-1 | |

| Solar radiation pressure coefficient | ||

| Systematic error of Ranging for each tracking arc | ||

| Weight of observations | 1 m for ranging | |

| 0.8 mm/s for Doppler | ||

| 5 cm for VLBI delay | ||

| 1 mm/s for VLBI delay rate |

To test the capabilities of orbit determination under different tracking modes and test the effectiveness of certain observation, three tracking modes are designed. In the Earth-Mars transfer phase, the dynamics of Tianwen-1 varies slowly and the arc is short relative to the barycenter of the solar system. To obtain as high accuracy of orbit determination as possible, all the four types of observations are needed. It corresponds to CDSMN + CVN tracking mode. The planetary radio interferometry and Doppler experiment (PRIDE) operated by the Joint Institute for VLBI in Europe (JIVE) raises the deep space state vector estimation with VLBI and Doppler measurements (Duev et al. 2012). It corresponds to PRIDE-like tracking mode. Considering CDSMN + CVN tracking mode occupies the equipments a lot and the effectiveness of VLBI drops with the distance of the spacecraft increasing, the capability of only the CDSMN needs to be tested. It corresponds to the CDSMN-only tracking mode.

CDSMN + CVN tracking mode includes Ranging, Doppler, VLBI delay and VLBI delay rate;

PRIDE-like tracking mode includes VLBI delay and Doppler;

CDSMN-only tracking mode includes Ranging and Doppler.

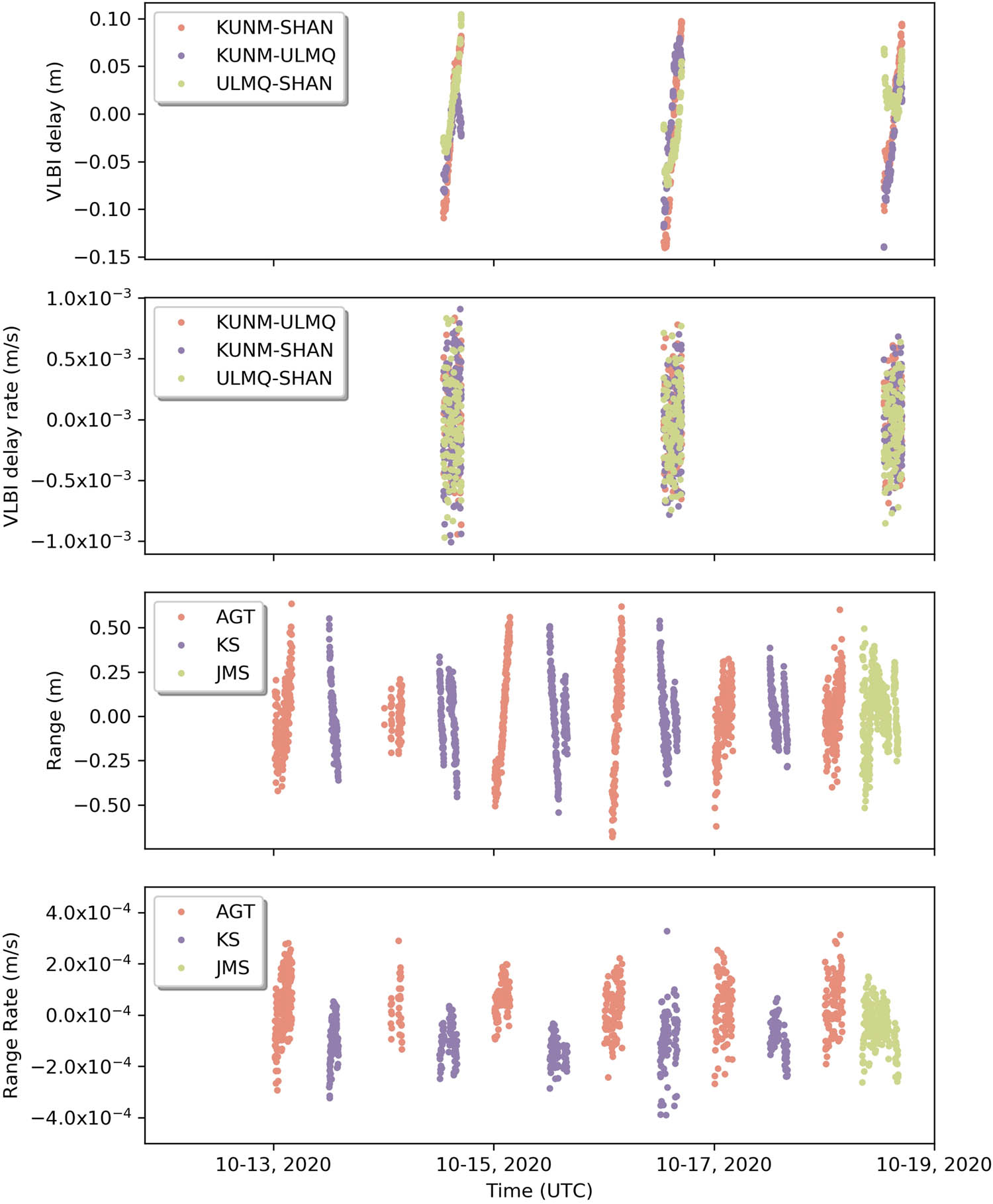

5.1 Transfer orbit

The Earth-Mars transfer orbit is a ellipse with the semi-major axis of about 1.33AU and the eccentricity of 0.23 after the deep space maneuver. Figure 6 shows the residuals of all the observations in the transfer phase under CDSMN + CVN tracking mode. For the data sample selected, the residual RMS of ranging is 0.205 m, the residual RMS of Doppler is 0.117 mm/s, the residual RMS of VLBI delay is 5.31 cm and the residual RMS of VLBI delay rate is 0.329 mm/s.

The postfit residuals of observations from October 13, 2020, to October 19, 2020.

Table 4 presents a comparison of the residual RMS after orbit determination during the transfer phase between Chang’E-4 Relay Satellite mission (Songhe et al. 2019) and Tianwen-1 mission. It is found that accuracies of the four types of observations are at the same level and not affected by distance. The small improvement of Ranging and Doppler might be the result of the CDSMN upgrade.

Comparison of the residual RMS of the observations in Chang’E-4 Relay Satellite mission and Tianwen-1 mission

| Mission | Ranging (m) | Doppler (mm/s) | VLBI delay (cm) | VLBI delay rate (mm/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chang’E-4 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 3.6 | 0.2 |

| Tianwen-1 | 0.205 | 0.117 | 5.31 | 0.329 |

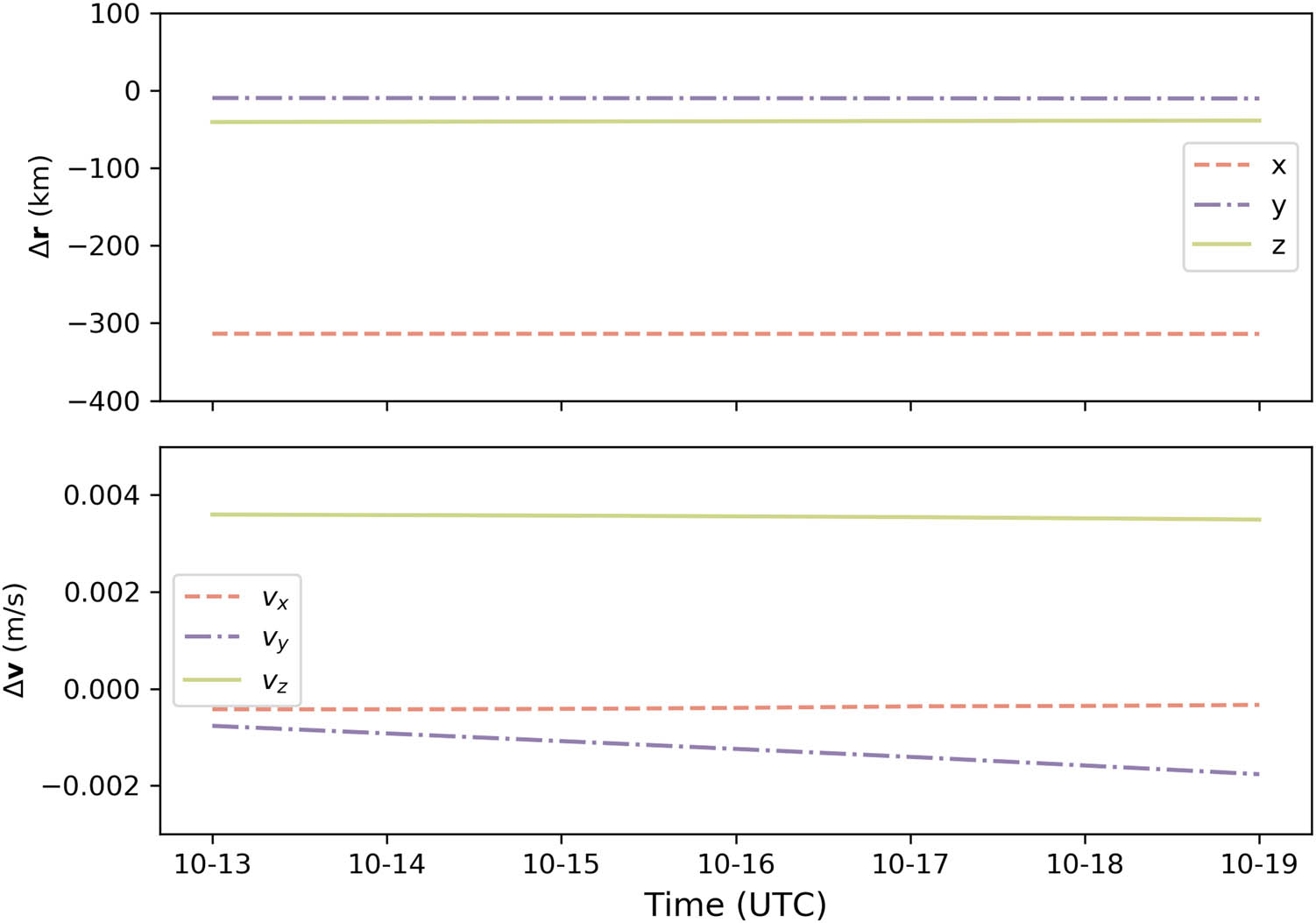

Under PRIDE-like tracking mode, the residual RMS of Doppler is 0.113 mm/s and the residual RMS of VLBI delay is 5.31 cm. The postfit residuals under the two tracking modes are at the same level. However, the differences of positions are over 300 km, while the maximum difference of velocities reaches 5 mm/s. The differences of positions and velocities vary small in 6 days since it is a short arc for the interplanetary transfer orbit. Figure 7 shows the positions and velocity differences of Tianwen-1 between CDSMN + CVN tracking mode and PRIDE-like tracking mode in the Mars-Earth transfer phase.

The differences of the position and velocity between CDSMN + CVN tracking mode and PRIDE-like tracking mode in the Mars-Earth transfer orbit.

Table 5 presents the comparison of the orbit determination errors under CDSMN + CVN tracking mode and PRIDE-like tracking mode. It is found that the error of the estimated positions under PRIDE-like tracking mode is over 100 times as that under CDSMN + CVN tracking mode. Taking both the error of orbit determination and the differences of positions into consideration, the position error under PRIDE-like tracking mode is larger than 100 km.

Comparison of the orbit determination errors under CDSMN + CVN tracking mode and PRIDE-like tracking mode in the Earth-Mars transfer phase

| State | CDSMN + CVN | PRIDE-like |

|---|---|---|

|

|

7.422 | 43309.389 |

|

|

36.420 | 1341.149 |

|

|

51.328 | 5610.685 |

|

|

0.0000 | 0.0001 |

|

|

0.0001 | 0.0001 |

|

|

0.0110 | 0.0005 |

Orbit determination under CDSMN-only tracking mode is hard to converge in the transfer phase. Orbit determination under PRIDE-like tracking mode can obtain the convergence, but the accuracy of position is over 100 km.

5.2 Orbiting Mars

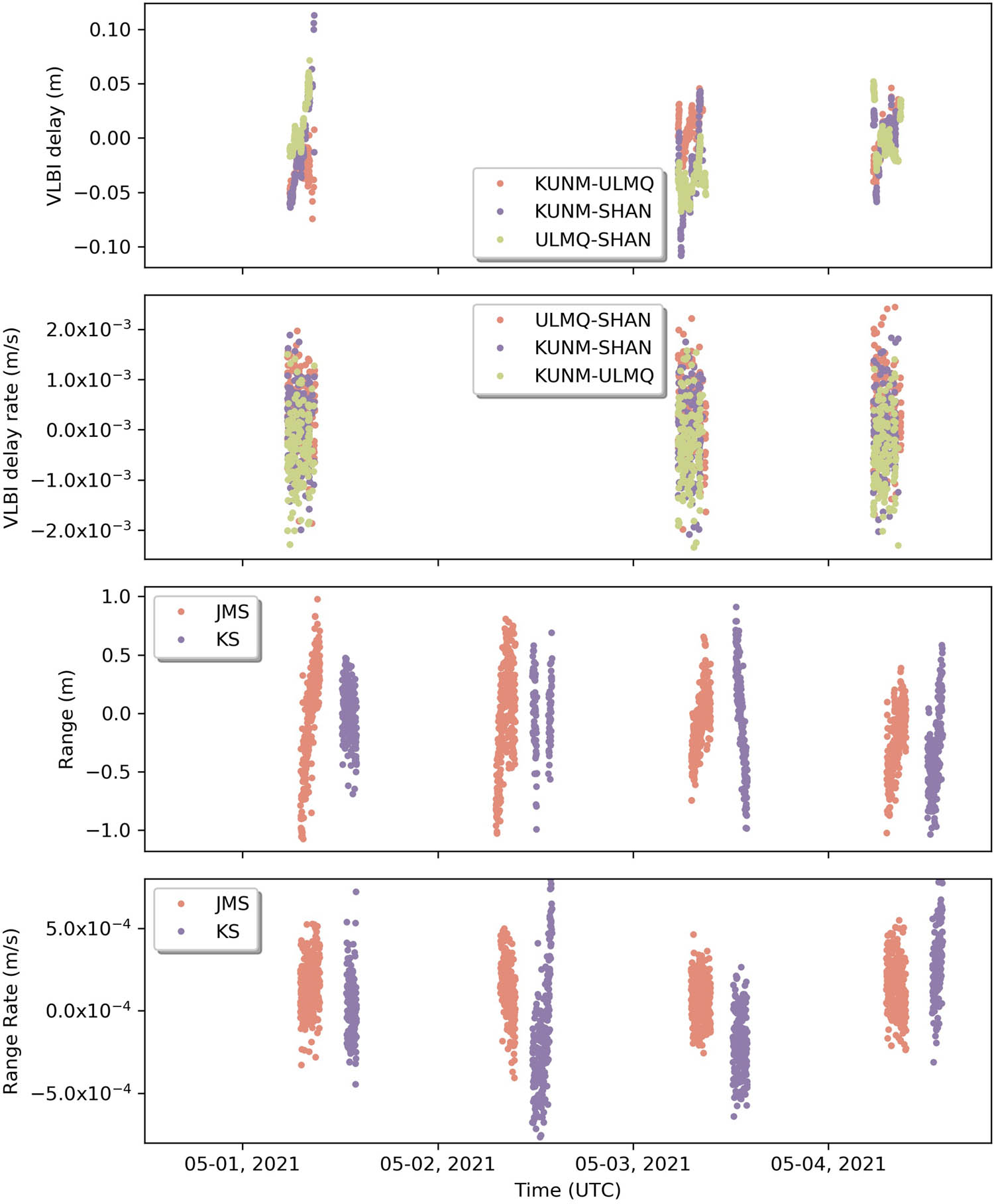

After Tianwen-1 orbiting Mars successfully, detection and imaging of the landing area were conducted immediately. Before the orbit control for the orbiter-lander separation, the Tianwen-1 moved on the parking orbit for a few days without any maneuvers. Figure 8 shows the residuals of all the observations in the Mars-orbiting phase. For the data sample selected under CDSMN + CVN tracking mode, the residual RMS of ranging is 0.381 m, the residual RMS of Doppler is 0.543 mm/s, the residual RMS of VLBI delay is 3.29 cm and the residual RMS of VLBI delay rate is 0.791 mm/s.

The postfit residuals of observations from May 1st 2021 to May 5th 2021.

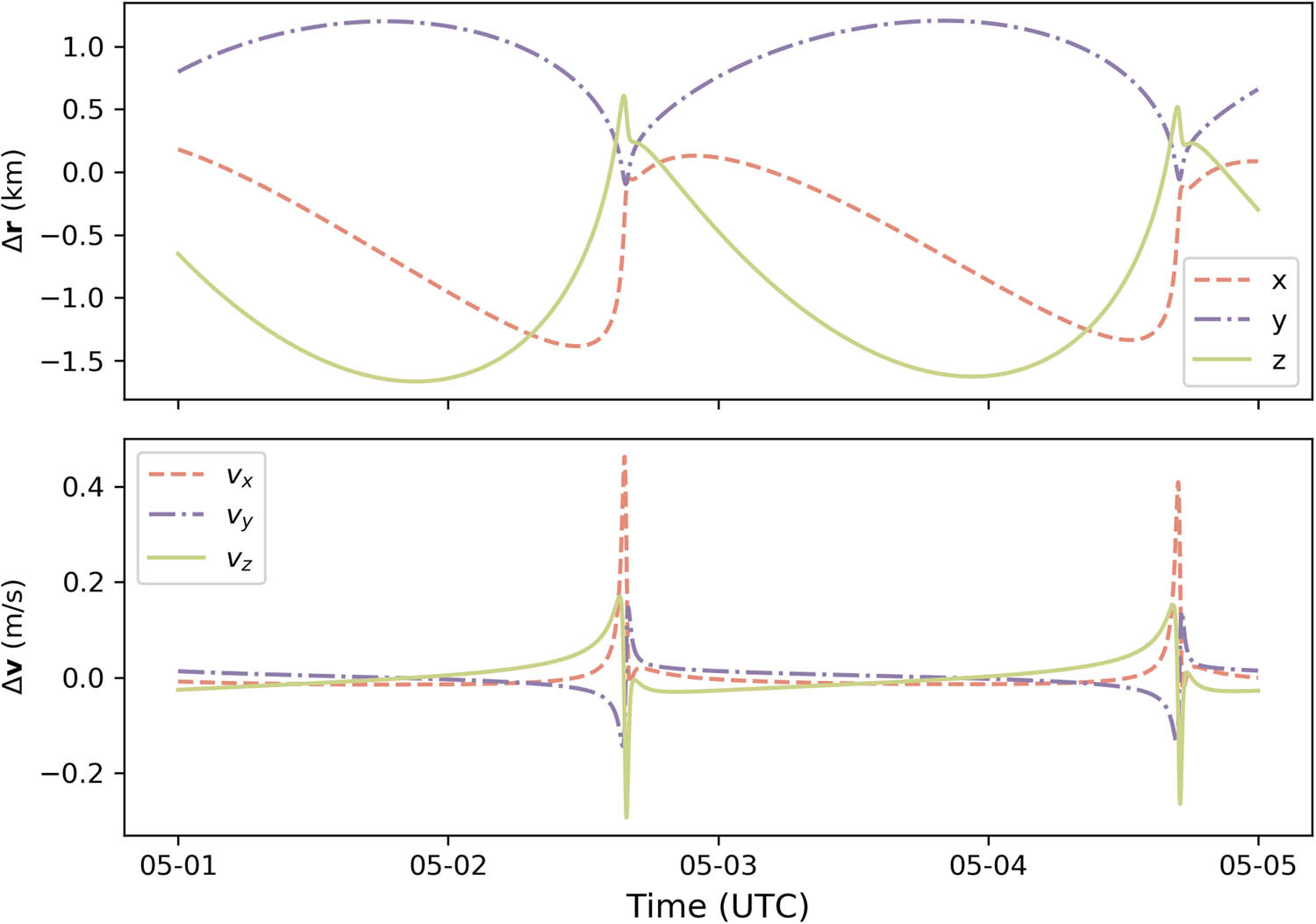

Under CDSMN-only tracking mode, the residual RMS of ranging is 0.384 m and the residual RMS of Doppler is 0.230 mm/s. The postfit residuals under the two tracking modes are at the same level. Figure 9 shows the positions and velocity differences of Tianwen-1 between CDSMN + CVN tracking mode and CDSMN-only tracking mode in the Mars-orbiting phase. The maximum difference of positions is smaller than 2.5 km, and the maximum difference of velocities is smaller than 0.5 m/s.

The difference of the position and velocity between CDSMN + CVN tracking mode and CDSMN-only tracking mode in the Mars-orbiting phase.

Table 6 presents the comparison of the orbit determination error under CDSMN + CVN tracking mode and CDSMN-only tracking mode. It is found that the error of the estimated positions under CDSMN-only tracking mode is roughly 10 times as that under CDSMN + CVN tracking mode, so is the error of the estimated velocities. Taking both the error of orbit determination and the differences of positions into consideration, the position accuracy under CDSMN-only tracking mode is about 1 km.

Comparison of the orbit determination errors under CDSMN + CVN tracking mode and CDSMN-only tracking mode in the Mars-orbiting phase

| State | CDSMN + CVN | CDSMN-only |

|---|---|---|

|

|

3.903 | 31.248 |

|

|

16.340 | 163.244 |

|

|

35.284 | 360.744 |

|

|

0.0003 | 0.0030 |

|

|

0.0002 | 0.0019 |

|

|

0.0005 | 0.0046 |

The CDSMN-only tracking mode is much more accurate in the Mars-orbiting phase than the mode in the transfer phase. The effectiveness improvement of CDSMN-only tracking mode is a result of the dynamics characteristics of the Mars space.

6 Conclusion

Three Mars exploration missions are executed in 2020, and all the three succeeded. China accomplished orbiting, landing and rovering in its first Mars exploration. To support this mission, State Key Laboratory of Astronautic Dynamics started the construction of a new orbit determination software in 2016.

A parallel observation process architecture is designed to promote the computational efficiency of deep space orbit determination. By dividing the entire observations into data blocks and putting different data blocks into different threads, the observations process can be paraleled. With 6522 deep space observations, the parallel orbit determination is tested, and the result shows that the computational efficiency per iteration (including spacecraft’s integration) could be 10 times as that of single-threaded orbit determination by using 32 threads. Supposed that the number of observations is

The residual RMS of CDSMN and CVN observations in the Earth-Mars transfer phase and the Mars-orbiting phase are almost the same: about 0.3 m for ranging, about 0.3 mm/s for Doppler, about 3 cm for VLBI delay and about 0.5 mm/s for VLBI delay rate. The accuracy of observations is also at the same level with that of Chang’E-4 mission. The small improvement of ranging and Doppler might be the result of the CDSMN upgrade.

Besides orbit determination with all the four types of observations, orbit determination under PRIDE-like tracking mode (with VLBI delay and Doppler) and under CDSMN-only tracking mode (with ranging and Doppler) are also calculated. It is found that CDSMN-only tracking mode easily leads to divergence for orbit determination, and PRIDE-like tracking mode might not quite fit the orbit accuracy requirements in the transfer phase. In the Mars-orbiting phase, the position accuracy under CDSMN-only tracking mode can reach about 1 km.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Z.B. Huyan, P.B. Ma, D.P. Zhang and H.N. Li designed the architecture of the new orbit determination software of State Key Laboratory of Astronautic Dynamics, Z.B. Huyan and D.P. Zhang programmed the software, P.B. Ma was in charge of the validation of the software, H.N. Li was in charge of the supervision of the development. The idea of parallel observations process grew out of the discussion between Z.B. Huyan and D.P. Zhang. The best number of threads was derived by Z.B. Huyan. The Tianwen-1 data was prepared by M. Zhai. The experiment was conducted by Z.B. Huyan and D.P. Zhang. The article was written by Z.B. Huyan. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

Duev DA, Calvés GM, Pogrebenko SV, Gurvits LI, Cimó G, Bahamon TB. 2012. Spacecraft VLBI and Doppler tracking: algorithms and implementation. A&A 541(A43):9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201218885. 10.1051/0004-6361/201218885Suche in Google Scholar

Flanagan S, Ely T. 2001. Navigation and mission analysis software for the next generation of JPL missions. In: Proceedings of the 16th International Symposium on Space Flight Dynamics. Pasadena. Suche in Google Scholar

Folkner WM, Yoder CF, Yuan DN, Standish EM, Preston RA. 1997. Interior structure and seasonal mass redistribution of mars from radio tracking of mars pathfinder. Science. 278(5344):1749–1752. 10.1126/science.278.5344.1749Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Hiroshi T, Kent Y, Yuto T, Yusuke O, Shota K, Hitoshi I. 2020. The deep-space multi-object orbit determination system and its application to Hayabusa2’s asteroid proximity operations, Astrodynamics. 4(4):377–392. 10.1007/s42064-020-0084-7Suche in Google Scholar

Genova A, Goossens S, Lemoine FG, Mazarico E, Neumann GA, Smith DE, et al. 2016. Seasonal and static gravity field of mars from mgs, mars odyssey and mro radio science. Icarus. 272:228–245. 10.1016/j.icarus.2016.02.050Suche in Google Scholar

Givens JW. 1958. Computation of plane unitary rotations transforming a general matrix to triangular form. SIAMJ Appl Math. 6:26–50. 10.1137/0106004Suche in Google Scholar

Guo M, Huang X, Li M, Hu J, Xu C. 2022. Adaptive entry guidance for the Tianwen-1 mission. Astrodynamics. 6:17–26. 10.1007/s42064-021-0120-2Suche in Google Scholar

Huang X, Xu C, Hu J, Li M, Guo M, Wang X, et al. 2022. Powered-descent landing GNC system design and flight results for Tianwen-1 mission. Astrodynamics. 6:3–16. 10.1007/s42064-021-0118-9Suche in Google Scholar

Konopliv AS, Yoder CF, Standish EM, Yuan DN, Sjogren WL. 2006. A global solution for the Mars static and seasonal gravity, Mars orientation, Phobos and Deimos masses, and Mars ephemeris. Icarus. 182:23–50. 10.1016/j.icarus.2005.12.025Suche in Google Scholar

Konopliv AS, Asmar SW, Folkner WM, Karatekin Ö, Nunes DC, Smrekar SE, et al. 2011. Mars high resolution gravity fields from MRO, Mars seasonal gravity, and other dynamical parameters. Icarus. 211:401–428. 10.1016/j.icarus.2010.10.004Suche in Google Scholar

Konopliv AS, Park RS, Folkner WM. 2016. An improved jpl mars gravity field and orientation from mars orbiter and lander tracking data. Icarus. 274:253–260. 10.1016/j.icarus.2016.02.052Suche in Google Scholar

Liu X, Jürgen S. 2020. Configuration of the martian dust rings: shapes, densities, and size distributions from direct integrations of particle trajectories. MNRAS. 500(3):2979–2985. 10.1093/mnras/staa3084Suche in Google Scholar

Marty JC. 2013. Algorithmic documentation of the GINS software. Paris, France: CNES. Suche in Google Scholar

Moyer TD. 1971. Mathematical formulation of the double-precision orbit determination program (DPODP). Pasadena, Calif: Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Suche in Google Scholar

Moyer TD. 2000. Formulation for observed and computed values of deep space network data types for navigation. Pasadena, Calif: Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Suche in Google Scholar

Pavlis DE, Wimert J, McCarthy J. 2013. GEODYN II system description. Greenbelt, U.S: SGT Inc. Suche in Google Scholar

Petit G, Luzum B. 2010. IERS Technical Note No. 36, IERS Conventions. Verlag des Bundesamts für Kartographie und Geodäsie, Frankfurt am Main. Suche in Google Scholar

Saastamoinen J. 1972. Atmospheric correction for the troposphere and stratosphere in radio ranging satellites. The Use of Artificial Satellites for Geodesy. 15:247–251. 10.1029/GM015p0247Suche in Google Scholar

Seidelmann PK, Archinal BA, A’hearn MF, Conrad A, Consolmagno GJ, Hestroffer D, et al. 2007. Report of the IAU/IAG Working Group on cartographic coordinates and rotational elements: 2006. Celestial Mech Dyn Astr. 98:155–180. 10.1007/s10569-007-9072-ySuche in Google Scholar

Semenov BV, Acton CH. 2007. Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter Spice Kernels V1.0. NASA Planetary Data System. Suche in Google Scholar

Smith DE, Lerch FJ, Nerem RS, Zuber MT, Patel GB, Fricke SK, et al. 1993. An improved gravity model for Mars: Goddard Mars model 1. J Geophys Res. 98(E11):20871–20889. 10.1029/93JE01839. Suche in Google Scholar

Smith DE, Sjogren WL, Tyler GL, Balmino G, Lemoine FG, Konopliv AS. 1999. The gravity field of Mars: results from Mars global surveyor. Science, 286:94–97. 10.1126/science.286.5437.94Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Songhe Q, Yong H, Peijia L, Quan S, Min F, Xiaogong H, et al. 2019. Orbit and tracking data evaluation of Chang’E-4 relay satellite. Adv Space Res. 64(4):836–846. 10.1016/j.asr.2019.05.028. Suche in Google Scholar

Sunseri RF, Wu HC, Evans SE. 2012. Mission analysis, operations, and navigation toolkit environment (MONTE) Version 040. Pasadena, U.S.: Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Suche in Google Scholar

Wang A, Wang L, Zhang Y, Hua B, Li T, Liu Y, et al. 2022. Landing site positioning and descent trajectory reconstruction of Tianwen-1 on Mars. Astrodynamics. 6:69–79. 10.1007/s42064-021-0121-1Suche in Google Scholar

Willimas JG, Boggs DH, Folkner WM. 2013. DE430 lunar orbit, physical librations, and surface coordinates. Pasadena, Calif: Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 Zongbo Huyan et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- A generalized super-twisting algorithm-based adaptive fixed-time controller for spacecraft pose tracking

- Retrograde infall of the intergalactic gas onto S-galaxy and activity of galactic nuclei

- Application of SDN-IP hybrid network multicast architecture in Commercial Aerospace Data Center

- Observations of comet C/1652 Y1 recorded in Korean histories

- Computing N-dimensional polytrope via power series

- Stability of granular media impacts morphological characteristics under different impact conditions

- Intelligent collision avoidance strategy for all-electric propulsion GEO satellite orbit transfer control

- Asteroids discovered in the Baldone Observatory between 2017 and 2022: The orbits of asteroid 428694 Saule and 330836 Orius

- Light curve modeling of the eclipsing binary systems V0876 Lyr, V3660 Oph, and V0988 Mon

- Modified Jeans instability and Friedmann equation from generalized Maxwellian distribution

- Special Issue: New Progress in Astrodynamics Applications - Part II

- Multidimensional visualization analysis based on large-scale GNSS data

- Parallel observations process of Tianwen-1 orbit determination

- A novel autonomous navigation constellation in the Earth–Moon system

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- A generalized super-twisting algorithm-based adaptive fixed-time controller for spacecraft pose tracking

- Retrograde infall of the intergalactic gas onto S-galaxy and activity of galactic nuclei

- Application of SDN-IP hybrid network multicast architecture in Commercial Aerospace Data Center

- Observations of comet C/1652 Y1 recorded in Korean histories

- Computing N-dimensional polytrope via power series

- Stability of granular media impacts morphological characteristics under different impact conditions

- Intelligent collision avoidance strategy for all-electric propulsion GEO satellite orbit transfer control

- Asteroids discovered in the Baldone Observatory between 2017 and 2022: The orbits of asteroid 428694 Saule and 330836 Orius

- Light curve modeling of the eclipsing binary systems V0876 Lyr, V3660 Oph, and V0988 Mon

- Modified Jeans instability and Friedmann equation from generalized Maxwellian distribution

- Special Issue: New Progress in Astrodynamics Applications - Part II

- Multidimensional visualization analysis based on large-scale GNSS data

- Parallel observations process of Tianwen-1 orbit determination

- A novel autonomous navigation constellation in the Earth–Moon system