Abstract

We report the Korean records for comet C/1652 Y1, which have not been introduced in previous studies on historical comets. According to Korean historical documents, this comet, described as bai xing (white star, in literal) or ke xing (guest star, in literal), was observed with the naked eye for 22 days from December 19, 1652 to January 9, 1653. In this study, we first cross-checked the records of comet C/1652 Y1 among Korean documents and presented the translations in the Appendix for future reference. We then compared the Korean observations with the orbital path determined from calculations using the orbital elements provided by Marsden (1983. Catalog of cometary orbit. Hillside: Enslow Publishers). We also compared the illustrations depicted by Weigelius and Schiltero (1653. Commentatio astronomica de cometa novo qui sub finem anni 1652 lumine sub obscuro nobis illuxit. Jenae: Typis Georgii Sengenvvaldi) and by Hevelius (1668. Cometographia, Totam Naturam Cometarum; Exhibens. Gedani: Typis Auctoris, & Sumptibus, Simon Reiniger). We found that the Korean observations show discrepancies with the orbital path calculated by Marsden and the illustration of Weigelius and Schiltero, particularly near the end of the observation period. In conclusion, we believe that this study will contribute to improving the orbital path calculation of comet C/1652 Y1.

1 Introduction

Historical astronomical records are invaluable for studying the long-term behavior of celestial bodies, such as meteors, comets, and novae. A notable example is Halley’s (1656–1742) discovery that the comet 1P/Halley, later named in his honor, is periodic. By calculating the orbital elements of 24 comets from historical observations he identified three comets with strikingly similar orbital paths (Halleio 1704). He also predicted the comet’s return in late 1758; it reappeared a year later, at the end of 1759 (refer to the study by Lee et al. 2014).

Comet appearances have historically garnered significant attention due to their prominent appearance in the sky, with records of such events preserved worldwide. East Asian nations, notably such as China, Korea, and Japan, have performed systematic and detailed astronomical observations under state auspices since ancient times, chronicling these in historical texts, typically within the annals of history. Drawing on these accounts, Kiang (1972) calculated the long-term orbital paths of comet Halley (Yeomans and Kiang 1981), while Hasegawa and Nakano (1995) identified three periodic comets (Hasegawa and Nakano 2003). More recently, Choi et al. (2018) confirmed that the Korean record of comet Halley’s return in 1222 described it as being sufficiently bright to be seen during daylight, not merely at twilight.

The comet records in East Asian historical texts have been compiled by numerous authors, such as Williams (1871), Sekiguchi (1917), Kanda (1935), Ho (1962), Hasegawa (1979, 1980), Kronk (1999), Park and Chae (2007), and Pankenier et al. (2008). In the context of Korean history, the primary source often cited is the Jeungbo-Munheon-Bigo (The Revised and Enlarged Edition of the Comparative Review of Records and Documents, hereafter referred to as Bigo), which encompasses the whole period of Korean history. For the Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), the astronomical records are contained in the Joseonwangjo-Sillok (The Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty, hereafter referred to as Sillok) and Seungjeongwon-Ilgi (The Daily Records of the Royal Secretariat of the Joseon Dynasty, hereafter referred to as Silgi) both of which are available online. Most recently, Lee (2023) identified the Donggung-Ilgi (The Daily Records of the Royal Educational Office of the Crown Prince of the Joseon Dynasty, hereafter referred to as Dilgi) as another significant source of Korean historical astronomical records.

In this study, we analyze Korean records of comet C/1652 Y1, a subject not previously studied in historical comet research. The structure of this article is as follows: Section 2 provides a concise introduction to the Korean historical documents consulted in this research, the astronomical terminologies related to the observations, and the distinct characteristics of the Korean records. Section 3 is dedicated to analyzing the Korean observations and comparing them with the orbital paths obtained from established orbital elements. We then deliberate on the implications of the Korean records and draw conclusions in Section 4.

2 Korean records

2.1 Historical documents

For the Korean records of comet C/1652 Y1, we consulted four historical documents: Sillok, Silgi, Dilgi, and Bigo. Sillok is the official chronicle of the Joseon dynasty, meticulously documented over 500 years. Meanwhile, Silgi is a daily record maintained by the Seungjeongwon (Royal Secretariat), with extant records dating back to 1623, though it is estimated to have originated at the dynasty’s outset. Hence, Silgi covers half the period of Sillok but is four times greater in volume. Dilgi, akin to Silgi, is a daily log produced by the Sigangwon (Royal Educational Office of the Crown Prince). As Lee (2023) highlighted, Dilgi contains a great number of records on astronomical phenomena, including meteorological ones such as solar and lunar halos and unusual clouds (Bahk et al. 2022). According to the Seoungwan-Ji (Treatise on the Royal Astronomical Bureau) compiled by Ju-Deok Seong in 1818, astronomical observations were reported to both the Seungjeongwon and Sigangwon (Jeon 1974). This could explain the abundance of astronomical records in both Silgi and Dilgi, and why their contents are nearly identical. While Sillok and Silgi underwent one or two compilations (though not comprehensively), Dilgi is known as the original manuscript. However, Dilgi’s chronology is incomplete, as its creation commenced only with the nomination of a crown prince. The series of 13 crown princes is preserved at the Kyujanggak Institute for Korean Studies. Dilgi, like Silgi, was handwritten in Chinese characters; recently, portions of the series have been translated into Korean and published in print. In this research, we reference Hyeonjong’s Dilgi, pertaining to the era when King Hyeonjong was crown prince (i.e., 1650–1659). Lastly, Bigo spans from the Three Kingdoms Period (54 BC–AD 918) to the Joseon dynasty in Korea, cataloging a diverse array of astronomical events. Despite being a frequently cited resource in the study of Korean astronomical records, Bigo is noted for its brevity and occasional inaccuracies.

2.2 Astronomical terminologies

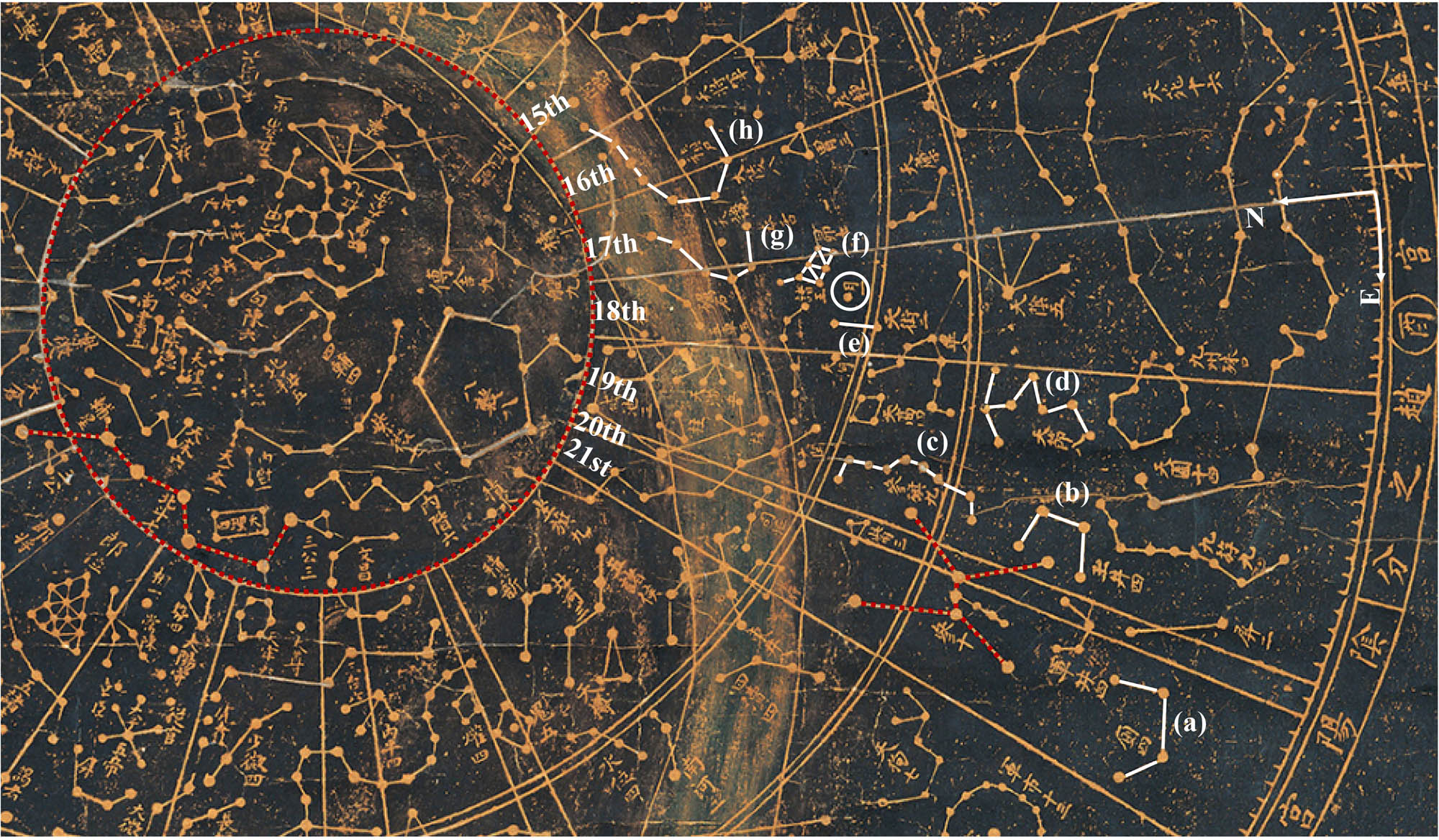

Korean historical astronomy closely mirrors that of China. For an in-depth understanding of the terminology related to astronomical and night-hour systems, refer to the study by Lee (2012, 2023) and Lee et al. (2012). Here, we provided a brief overview of the celestial sphere system and its angular units. The celestial sphere was divided into three yuan (hereafter, enclosure) surrounding the North Pole and four cardinal directions (East, West, South, and North) including each seven Su (i.e., lunar mansion); hence, it comprises a structure of three enclosures and 28 lunar mansions. These enclosures and lunar mansions comprise multiple constellations, including a namesake constellation for each enclosure and lunar mansion. For example, the mao (18th) lunar mansion in the West includes nine constellations, such as yue, juanshe, and tianyin, in addition to the mao constellation itself. Notably, the term xing was employed to denote various entities: constellations (e.g., can xing, i.e., Orion), stars (e.g., hegu da xing, i.e., Altair), and planets (e.g., shui xing, i.e., Mercury). As an example, Figure 1 presents a segment of the Cheonsang-Yeolcha-Bunyaji-Do, a traditional Korean star chart engraved in stone in 1395 (Rufus 1913). This star chart centers on the North Pole, with radial lines demarcating the 28 lunar mansions, and utilizes an equidistant projection method to depict stars. Particularly, a star located at the radial boundary of a lunar mansion is termed suju xing, serving as a determinative star for that mansion. For example, the determinative star for the can (twenty-first) lunar mansion is

A part of Cheonsang-Yeolcha-Bunyaji-Do (source: Kyujanggak Institute for Korean Studies) showing constellations referred to this study: (a) (tian)ce, (b) yujing, (c) canqi, (d) tianjie (Cheonjeol in Korean pronunciation, hereafter refer to tianjie A), (e) tianjie (Cheonga in Korean pronunciation, hereafter refer to tianjie B), (f) mao, (g) juanshe, and (h) daling constellations. The fifteenth, sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth, nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first indicate the regions of the kui, lou, wei, mao, bi, zi, and can lunar mansions, respectively. The constellation marked with a white circle in the eighteenth lunar mansion is yue constellation consisting of one star. For reference, the red dotted circle represents the circumpolar circle, and the constellations marked with red dotted lines are the beidou (Big Dipper) and can (Orion) constellations on the left- and right-hand sides, respectively.

The units xiao (small, in literal; 1/4 du), ban (half, in literal; 2/4 du), tai (large, in literal; 3/4 du), qiang (strong, in literal; +1/12 du), and ruo (weak, in literal; −1/12 du) represent fractions of du, an angular unit. For example, 7 du and qiang equals 85/12 du (which is 7 + 1/12 du), and 1 du is roughly equivalent to 0.9856° (= 360°/365.2575 du) before 1654 in Korea. Lastly, we determined the night length (i.e., from evening twilight time to morning twilight time the next day), equally divided into five intervals, and obtained the duration of each interval, named the geng (hereafter referred to as watch). We found that the mean duration of each watch was approximately 2.6 h for the period from December 19, 1652 to January 9, 1653. Assuming the observation time to be the midpoint of the watch recorded in the historical texts, unless indicated otherwise, the uncertainty in time estimation is approximately

2.3 Korean records

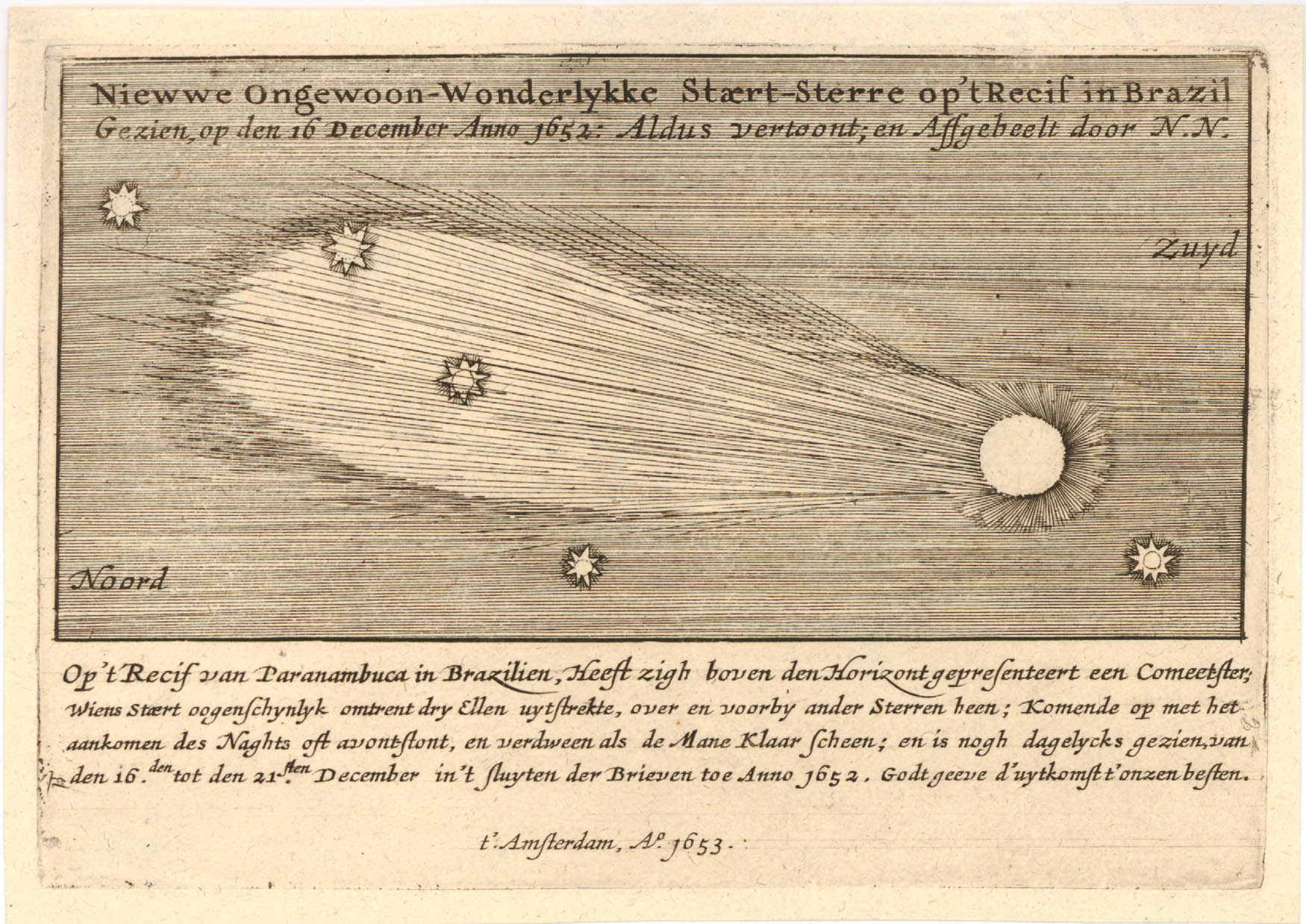

According to Pienaar (1948), comet C/1652 Y1 was first sighted by Jan van Riebeeck on the evening of December 17, 1652 in Cape Town, South Africa. As illustrated in Figure 2, this comet was observed by a Dutch on the evening of December 16, 1652 in Recife, Brazil. On the other hand, Silgi records indicate that observations of comet C/1652 Y1 spanned 22 days from December 19, 1652 (the 22nd day in China, according to Kronk (1999)) to January 9, 1653 (the twentieth day in Europe, according to Knobel (1897, 1918)). The absence of Korean records in previous studies, such as the work of Kronk (1999), may be attributed to the comet being termed bai xing (white star, in literal) in Sillok, Silgi, and Dilgi, and classified as a ke xing (guest star, in literal) in Bigo. We provide English translations of the records on comet C/1652 Y1 primarily from Silgi and Dilgi, which offer more detail than Sillok and Bigo, in the Appendix. We also provide Korean original texts, which are written in traditional Chinese characters. These records are presented in consecutive order, starting with the letter A. In the Appendix, dates are converted to the Gregorian calendar following Han (2001), yet the angles and night hours retain their original measurements in du and watch, as documented.

Drawing of comet C/1652 Y1 observed by a Dutch on December 16, 1652 at Recife in Brazil (source: British Museum).

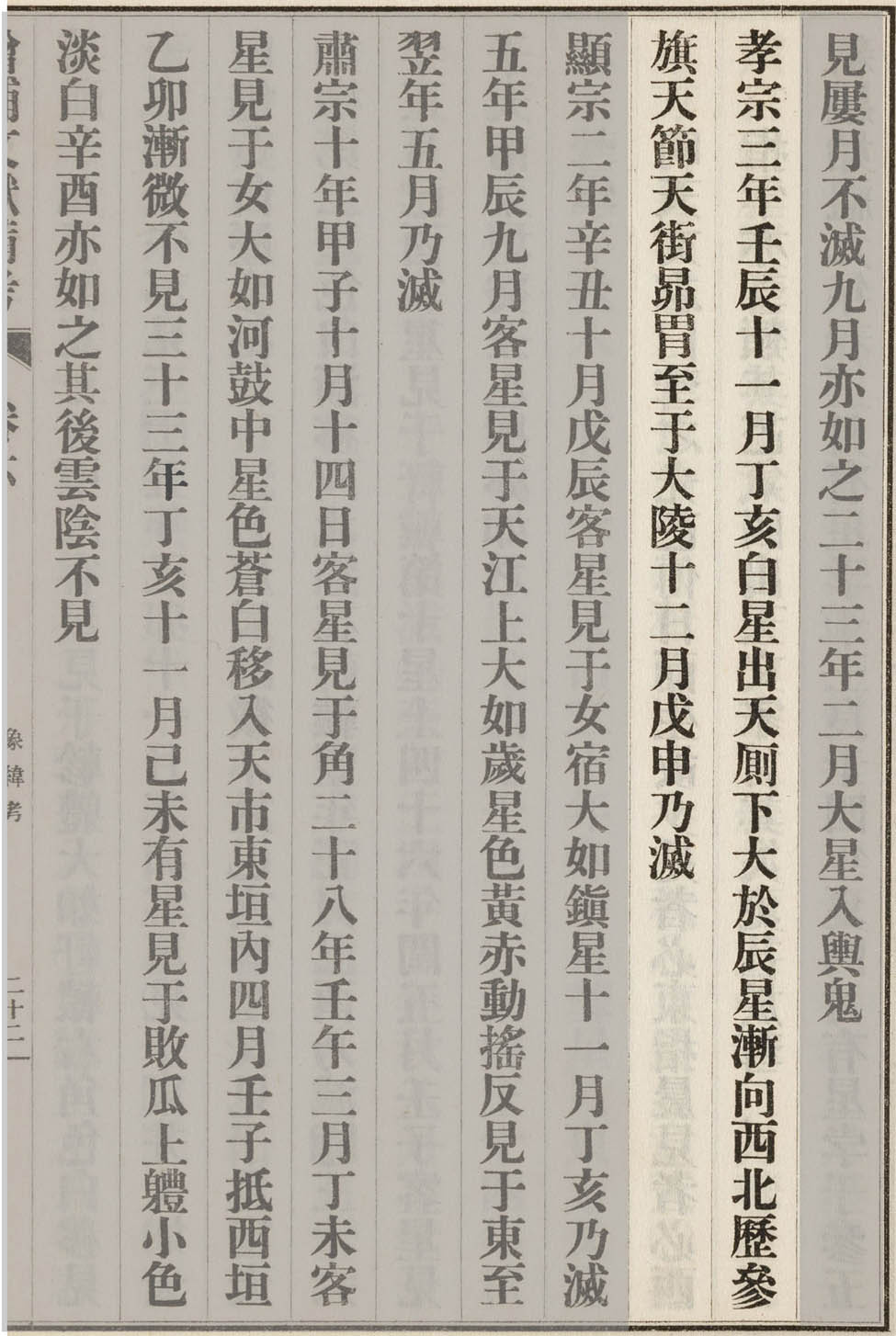

The remarkable characteristics of Korean documentation of comet C/1652 Y1 within each historical source are as follows. Sillok is characterized by a smaller number (14) of records and less detailed content compared to Silgi and Dilgi. Notably, Sillok lacks observation times. For example, Sillok’s record on December 26, 1652 simply notes that the comet moved to 1 du west of the juanshe constellation (A08). Dilgi, on the contrary, does not include any records for the period from January 1 to February 28, 1653; hence, there are no subsequent records regarding comet C/1652 Y1 from January 1, 1653 (A14–A21). In addition, Dilgi has no records of when the comet was unobservable (A04, A05, A09, and A11). Discrepancies are present between the documents; for instance, Sillok and Dilgi report that the comet trespassed the second and fifth stars of the daling constellation, respectively, on December 30, 1652, while Silgi has no record itself on this day (A12). In addition, Dilgi’s account on December 24, 1652 describes the comet’s size (i.e., brightness); as big (in literal) as the shui xing (i.e., Mercury), a detail not recorded in Sillok and Silgi (A06). On the contrary, Silgi’s account on December 31, stating, “At the 5th watch, the white star was still situated within the daling constellation and was 4 du away from the fifth star of the constellation,” is not recorded in Dilgi (A13). The records of Bigo are the most succinct of the four documents, and the last observed date differs, noting January 9, 1653 unlike Silgi, which records the last sighting on the eighth day. Specifically, Bigo merely reports, “On the dinghai day, the eleventh month, during the third year of King Hyojong’s reign (i.e., December 19, 1652), a white star appeared below the tiance constellation.” Its size was as big as the chen xing (also known as Mercury). It then gradually moved toward the northwest and reached the daling constellation, passing through the canqi, tianjie A, and tianjie B constellations (refer to Figure 1), as well as the mao and wei lunar mansions. It disappeared on the wushen day in the twelfth month (i.e., January 9, 1653)” (see Figure 3). Lastly, none of the documents mention observations of tail length, which is in contrast to other European records (e.g., Weigelius and Schiltero 1653; hereafter WS53). The comet C/1652 Y1 might be described as a white star (or classified as a guest star) in Korean documents because its tail was not visible to the naked eye. It is known that telescopes were not used during the Joseon dynasty, although they were first introduced in 1631 (Ahn 2009). In contrast, European observers may have used telescopes, as Arcieri did (Kronk 1999). For reference, the tail of the comet was reported to be at its longest on December 20, 1652 measuring 5° or 6° (Zolotova et al. 2018).

Highlighted text is the accounts on comet C/1652 Y1 recorded in Jeungbo-Munheon-Bigo (source: Kyujanggak Institute for Korean Studies). For translations, refer to the text.

3 Analysis of Korean observations

3.1 List of observations

Table 1 summarizes the positions of comet C/1652 Y1 as extracted from Korean historical documents. The first three columns present sequential numbers (No.), the date of the record (Date) in the Gregorian calendar, and the observation hour (Hour) in watch units, respectively. The fourth column provides the reference point used to measure the comet’s position. For the identification of stars in Chinese constellations, as mentioned in the records, with modern stars, we referred to the study by Kim (2020). The fifth column lists the angular distances (Ang. Dist.) in units of du, measured from the reference point. If the direction (Dir.) is specified in relation to the angular distance, it is included in the sixth column. Our inferences based on the analysis are presented in parentheses in columns 4, 5, and 6. The final column notes the corresponding records from the Appendix. The symbol T in the parentheses indicates the record of a fan (trespass, in literal) event. According to the Seoungwan-Ji, such an event is recognized when the separation between two celestial bodies is 0.1 du, as noted in column 5.

Summary of positions of comet C/1652 Y1 recorded in Korean historical documents

| No. | Date (Greg. Cal.) | Hour (watch) | Reference point | Ang. Dist. (du) | Dir. | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dec. 19, 1652 | 1st | tiance constellation |

|

xun | A01 |

| 2 | Dec. 20, 1652 | 4th |

|

0.1(0.87°) | A02(T) | |

| 3(a) | Dec. 24, 1652 | 1st |

|

0.1(0.89°) | A06(T) | |

| 3(b) | 16 Tau3 | 3 | A06 | |||

| 3(c) | North pole | 67 | A06 | |||

| 3(d) | E. P.4 | 43 | A06 | |||

| 4 | Dec. 24, 1652 | 4th | 16 Tau3 | 4 | NE | A06 |

| 5 | Dec. 25, 1652 | 1st | 16 Tau3 | 7(3.38°) | N | A07 |

| 6 | Dec. 25, 1652 | 4th |

juanshe Constellation (

|

3 | S | A07 |

| 7 | Dec. 26, 1652 | 1st |

juanshe Constellation (

|

1 | W | A08 |

| 8(a) | Dec. 28, 1652 | 1st |

daling Constellation (

|

3 | S(E) | A10 |

| 8(b) |

juanshe Constellation (

|

6 | ||||

| 9 | Dec. 28, 1652 | 5th |

daling Constellation (

|

3 | E | A10 |

| 10 | Dec. 30, 1652 | 1st |

|

0.1(0.70°) | A12(T) | |

| 11 | Dec. 31, 1652 | 1st |

|

3 | A13 | |

| 12 | Dec. 31, 1652 | 5th |

|

4 | A13 | |

| 13 | Jan. 1, 1653 | 1st |

|

5 | A14 | |

| 14 | Jan. 1, 1653 | 5th |

|

71/12 | A14 | |

| 15 | Jan. 2, 1653 | 1st |

|

83/12 | A15 | |

| 16 | Jan. 2, 1653 | 5th |

|

85/12 | A15 | |

| 17 | Jan. 3, 1653 | 1st |

|

35/12 | S | A16 |

| 18 | Jan. 3, 1653 | 5th |

|

25/12 | S | A16 |

| 19 | Jan. 4, 1653 | 1st |

|

35/12 | S | A17 |

| 20 | Jan. 4, 1653 | 5th |

|

25/12 | S | A17 |

| 21 | Jan. 5, 1653 | 1st–5th |

|

0.5–0.6 | S | A18 |

1The third star of the yujing constellation, 2the upper star in the tianjie B constellation, 3determinative star of the mao lunar mansion, 4emerged place, 5the fifth star of the daling constellation, and 6the second star of the daling constellation.

The Korean observations offer several distinctive features. First, the initial observation on December 19, 1652 (No. 1) does not provide numerical data, simply notating the comet’s position in the southeast direction, referred to as xun. Second, the observations on December 20, 24, and 30, 1652 (Nos. 2, 3(a), and 10) documented fan events, where comet C/1652 Y1 was reported to trespass the third star of the yujing constellation (

3.2 Comparison with known orbital path

To scrutinize the Korean records of comet C/1652 Y1, we compared them with modern computational results, using the astronomical algorithms of Meeus (1998) and the DE406 ephemeris of Standish et al. (1997). We disregarded the value of

We calculated the trajectories of comet C/1652 Y1 using Marsden’s (1983) orbital elements initially set to the B1950.0 equinox and compared them with the comet positions summarized in Table 1. Recently, several studies, such as Neuhäuser et al. (2021) and Martínez et al. (2022), showed that Keplerian orbits for comets can be determined just from historical observations using the software find_orb (https://projectpluto.com/find_orb.htm). We also attempted to obtain a Keplerian orbit from Korean observations using the same software. However, we could not obtain reasonable orbital elements, presumably because of uncertainties in the observation hour, measured angular separation, direction, etc. Hence, as an alternative approach, we obtained the orbital elements giving minimum residuals with Korean observations by adjusting each element in the study by Marsden’s (1983) orbital elements by up to 20%. Table 2 summarizes the orbital elements determined by Marsden (1983) and in this study. In the table, symbols

Orbital elements of comet C/1652 Y1 reduced to the equinox of J2000.0

|

|

e | q (AU) |

|

|

i (

|

Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2324757.653 (1652 Nov. 13.153) | 1.0000 | 0.84750 | 300.19 | 93.001 | 79.461 | Marsden (1983) |

| 2324758.000 (1652 Nov. 13.500) | 0.9393 | 0.87959 | 302.64 | 93.193 | 75.065 | This study |

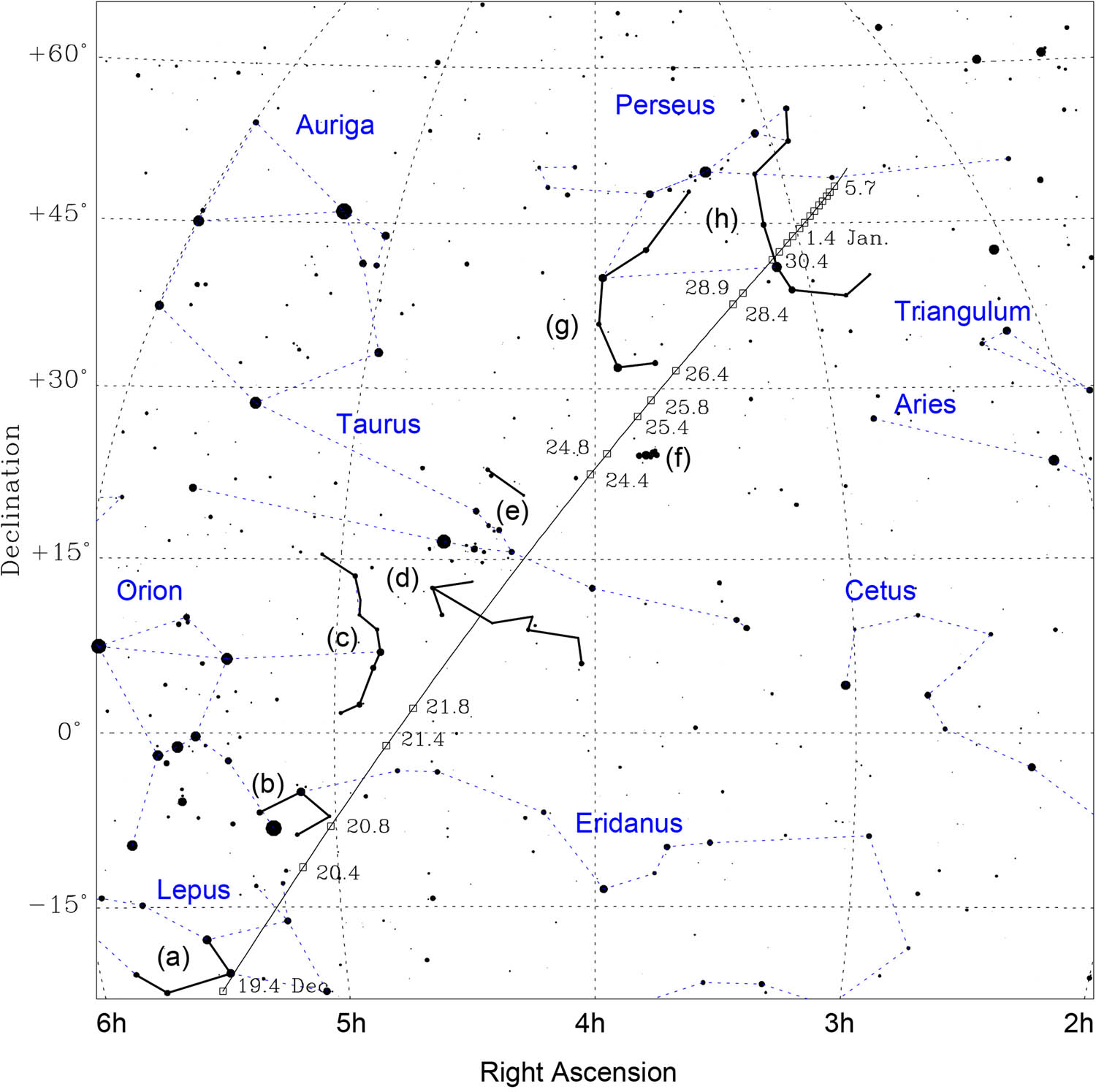

Orbital path of comet C/1652 Y1 calculated on the basis of the orbital elements of Marsden (1983). Horizontal and vertical axes are right ascension and declination in the equinox of J2000.0. Black rectangle symbols in the path are the positions of comet C/1652 on dates given in Table 1 but notated in units of UT. The Chinese constellations (black solid line) are (a) tiance, (b) yujing, (c) canqi, (d) tianjie A, (e) tianjie B, (f) mao, (g) juanshe, and (h) daling.

The record on December 19, 1652 states that at night the first watch, a white star was spotted below the tiance constellation, located at xun (No. 1). The term xun corresponds to a cardinal direction, specifically southeast within the octagonal compass system, or at an azimuth range of 112.5–157.5° when measured clockwise from true north. We determined the azimuth and altitude of the comet at the midpoint of the first watch (i.e., the 1.5th watch) on that date by transforming the apparent right ascension and declination obtained from orbital elements of Marsden (1983). The azimuth was approximately 119.6°, which corroborated the historical account, and the altitude was just above the horizon at approximately 0.7°. For reference, the azimuth and altitude of the comet at the end of the first watch are 132.7° and 14.0°, respectively. Directions associated with stars or constellations are deduced to correspond to positions on the celestial sphere as follows: north is directed toward the North Pole, and east refers to the clockwise rotation relative to each reference star or constellation, as depicted in Figure 1.

The account on December 24, 1652 indicates that the comet was located “below” and “above” the tianjie B constellation within the mao lunar mansion, as per Dilgi (and also Sillok) and Silgi, respectively (A06). The data represented in Figure 4 supports the description provided by Silgi, which places the comet “above” the tianjie B constellation. However, it is difficult to verify the observation from December 24, which reports the comet’s angular distance from the point of emergence as 43 du (No. 3(d)), because the reference point is ambiguous. The record on December 28 states that the comet had moved to 3 du east of the daling constellation according to Silgi (and also Sillok), and 2 du according to Dilgi, at the fifth watch (refer to A10). Upon analysis, the positioning at 3 du aligns more closely with the orbital path as outlined in Table 1 than 2 du positioning does, as demonstrated in Figure 5. In addition, the record on December 30 describes the comet as trespassing against the second and fifth stars of the daling constellation (

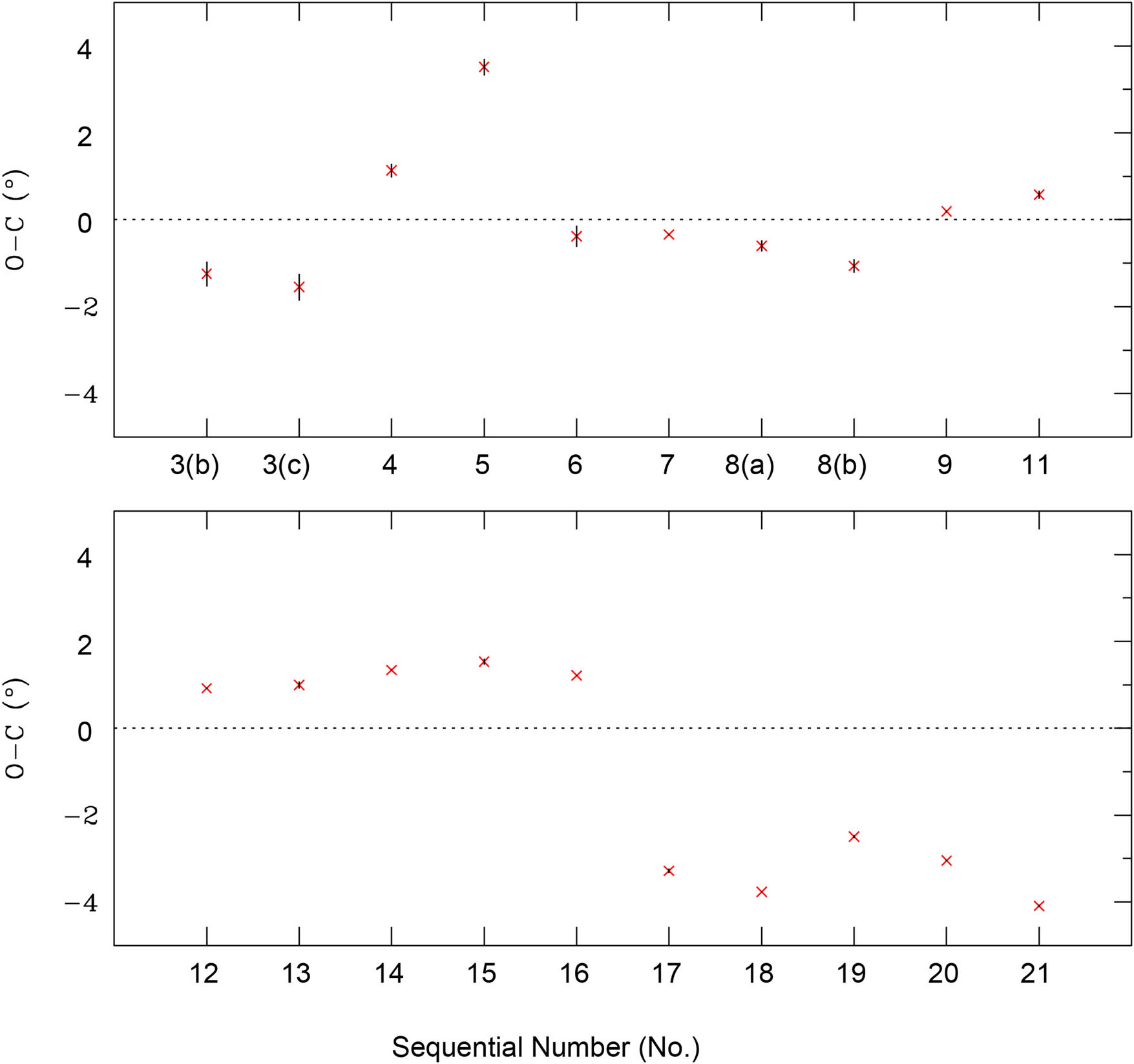

Differences of angular separation between observation values (O) recorded in Korean historical documents and calculated ones (C) using orbital elements of Marsden (1983). Horizontal axis represents sequential numbers given in Table 1 and vertical axis represents O–C. Black thick vertical lines are O–C values for the duration of each watch and red cross symbols are mean values in each O–C.

Regarding the trespass events, on December 20, 1652 (No. 2), the angular separation between the comet and the third star of the yujing constellation,

In analyzing the differences between observed values (O) in Korean historical documents and calculated values (C) using Marsden’s (1983) orbital elements, we tabulated the O–C values for all relevant observations. These are illustrated in Figure 5, where the horizontal axis is indexed by the sequence numbers from Table 1, and the vertical axis represents the O–C values. The bold black vertical lines denote the range of O–C values calculated over each watch, in increments of 0.001 d, provided the comet and reference star were above the horizon. The red crosses mark the average of these O–C values for each observation. It is noteworthy that O–C values are positive when measured from the fifth star (Nos. 11–16) and negative from the second star (Nos. 17–21) of the daling constellation. The observations from January 5, 1653 (No. 21) and December 25, 1652 (No. 5) display the most substantial deviations at −4.09° ± 0.02 and +3.51° ± 0.12, respectively. These significant discrepancies could be attributed to potential misidentifications of the second star in the daling constellation, transcription errors within the historical documents, or inaccuracies within the assumed orbital elements provided by Marsden (1983).

4 Discussion and conclusion

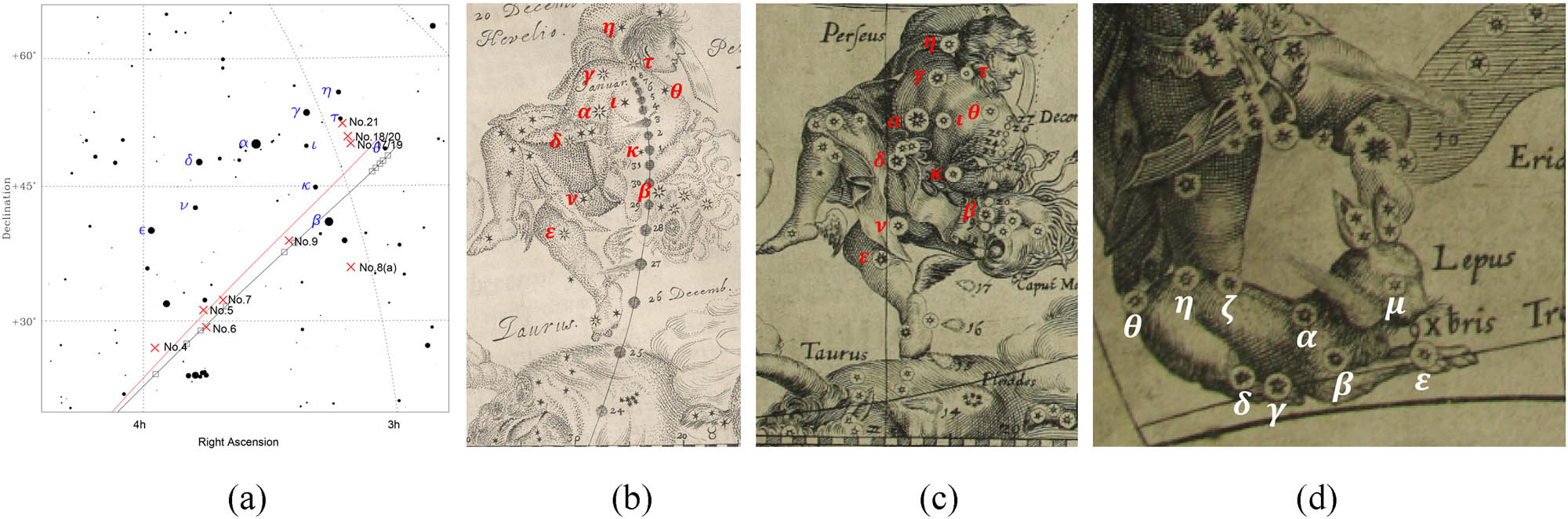

To estimate the cause of the significant discrepancies in observations where |O–C| > 2° (specifically for Nos. 5 and 17–21), we determined the locations of the comet using the accounts that detailed both angular separation and direction relative to a fixed reference point (recorded in Nos. 4–9 and 17–21). We then juxtaposed these findings against the illustrations from WS53 and Hevelius (1668). Figure 6 shows (a) the same as in Figure 4, alongside the positions of comet C/1652 Y1 based on Korean historical observations (red crosses) and the orbital path as deduced from the orbital elements in this study (red solid line) presented in Table 1, (b) a segment of the illustration by Hevelius (1668), and (c) and (d) sections of the illustration by WS53. It is crucial to note that the dates in Figure 6(c) and (d) are the Julian calendar ones, which lag by 10 days behind the Gregorian calendar dates. Hence, the date of (1652 December) 9 indicated in Figure 6(d) corresponds to (1652 December) 19 on the Gregorian calendar.

(a) Positions of comet C/1652 Y1 derived from Korean observations (red cross symbols) and the orbital path in our study (red solid line). (b) Part of the illustration of the comet drawn by (b) Hevelius (1668) (source: Library of Congress). (c) and (d) Parts of the illustration by WS53 (source: SLUB Dresden).

First, the recorded angular separation of 7 du on 1652 December 25 (No. 5) likely represents a typographical error, with 3 or 4 du being more plausible. Additionally, the southward direction mentioned for December 28, 1652 (No. 8a(a)) seems to be a mistaken notation for the east. Furthermore, while Silgi’s account on January 8, 1653 notes that the Moon trespassed the mao constellation at night on the first watch, modern calculations align this event with the early evening of the following day, the ninth day, as recorded in Sillok. Second, the orbital path of the comet, as derived from Marsden’s (1983) orbital elements (black rectangles in Figure 6(a)), correlates with WS53’s illustration (Figure 6(c)) where the comet passed to the right of

Acknowledgments

Bahk and Lee were supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the NRF funded by the Ministry of Education (No. 2019R1I1A3A01055211). Mihn and Kim were supported by the Dissemination on Astronomy and Space Science Information and Knowledge Project operated by the Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute (No. 2023187000).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

Appendix

A01. 1652 December 19: At night the first geng (watch), a bai xing (white star, in literal) emerged the tiance [below the tiance in Dilgi and Sillok] constellation (

A02. 1652 December 20: At night the first watch, the tai bai xing [bai xing in Dilgi and Sillok] moved into below the yujing constellation (

A03. 1652 December 21: At night the first watch, the white star moved into below the canqi constellation (11,

A04. 1652 December 22: At night from the first to fifth watches, the position of the white star was unobservable because it was cloudy all night [Silgi]. (夜自一更至五更終夜雲陰, 白星所在不得看候).

A05. 1652 December 23: Same as the record on December 22, 1662 [Silgi].

A06. 1652 December 24: At night the first watch, the white star [white cloud in Silgi] moved into above the tianjie B [below the tianjie B in Dilgi and Sillok] constellation (

A07. 1652 December 25: At night the first watch, the white star moved into 7 du north from the mao constellation [lunar mansion in Dilgi] [Silgi, Dilgi]. Its appearance was the same as the night before [Silgi]. It gradually moved northwards. At the fourth watch, it moved into 3 du south from the juanshe constellation (

A08. 1652 December 26: At night the first watch, the white star moved into 1 du west from the juanshe constellation within the angular range of the wei (the 17th) lunar mansion [the wei constellation in Dilgi] and gradually moved northwards. Its movement progressively became slower and the appearance [color in Silgi] gradually became smaller [Dilgi, Silgi]. At the third and fourth watches, it was unobservable because of wandering Gi (vapors) [Silgi]. (夜一更, 白星移在胃宿[星]度內卷舌星西一度, 漸移向北. 行度稍緩, 形色[色]漸微. 三四更, 以遊氣不得詳細測候).

A09. 1652 December 27: It was cloudy from the evening twilight to the fourth watch; hence, the position of the white star was unobservable [Silgi]. (初昏至四更, 雲陰, 白星所在, 不得看候).

A10. 1652 December 28: At night the first watch, the white star moved into 3 du south from the daling constellation (

A11. 1652 December 29: It was cloudy at night from the first to fifth watches; hence, the position of the white star was unobservable [Silgi]. (夜一更至五更, 雲陰, 白星所在, 不得看候).

A12. 1652 December 30: At night of the first watch, the white star trespassed the fifth star [the second star in Sillok] of the daling constellation. Its appearance was very small. At the fifth watch, it gradually moved northwards but was still situated within the daling constellation [Dilgi]. (夜一更, 白星觸犯大陵第五[二]星. 形色甚微. 五更, 漸離向北, 猶在大陵星內).

A13. 1652 December 31: At night the first watch, the white star was situated within the daling constellation and there was no change in its appearance as before. It was 3 du away from the fifth star [Dilgi, Silgi]. At the fifth watch, the white star was still situated within the daling constellation and was 4 du away from the fifth star [Silgi]. (夜一更, 白星在大陵星內, 形色與前無異. 離第五星三度. 五更, 白星猶在大陵星內, 離第五星四度).

A14. 1653 January 1: At night the first watch, the white star was situated within the daling constellation and the angular distance from the fifth star was 5 du. There was no change in its appearance as before. At the fifth watch, it was still situated within the daling constellation and the angular distance from the fifth star was 6 du and rou. Its movement had gradually slowed down [Silgi]. (夜一更, 白星在大陵星內, 距第五星五度. 形色與前無異. 五更, 猶在大陵星內, 距第五星六度弱. 行度漸遲).

A15. 1653 January 2: At night the first watch, the white star was situated within the daling constellation and the angular distance from the fifth star was 7 du and rou. At the fifth watch, the white star was still situated within the daling constellation and the angular distance from the fifth star was 7 du and qiang. There was still no change in its appearance as before. Its movement was the slowest [Silgi]. (夜一更, 白星在大陵星內, 距第五星七度弱. 五更, 白星猶在大陵星內, 距第五星七度强. 形色與前無異. 行度最緩).

A16. 1653 January 3: At night the first watch, the white star moved into 3 du and rou south from the second star of the daling constellation within the angular range of the lou (the 16th) lunar mansion. At the fifth watch, it was still situated within the daling constellation and the angular distance was 2 du and qiang south from the second star. The appearance became fainter compared to before. Its movement was the slowest [Silgi]. (夜一更, 白星移在婁宿度內, 大陵第二星南三度弱. 五更, 猶在大陵第二星南二度强. 形色比前稍微. 行度最緩).

A17. 1653 January 4: At night the first watch, the white star was still situated within the lou lunar mansion, which was 3 du and rou south from the second star of the daling constellation. At the fifth watch, it was still situated within the daling constellation and the angular distance was 2 du and qiang south from the second star. Because there were wandering vapors and the appearance was faint, it was hard to observe the details [Silgi]. (夜一更, 白星猶在婁宿內, 大陵第二星南三度弱. 五更, 猶在大陵第二星南二度强. 有遊氣, 白星形色熹微, 不得詳細窺測).

A18. 1653 January 5: At night from the first to fifth watches, the white star was approximately situated 5 or 6 cun south of the second star of the daling constellation. The body was very small, so it was unobservable by means of the kui guan (a sighting tube) [Silgi]. (夜一更至五更, 白星在大陵第二星南五六寸許. 體甚微, 以窺管不得測候).

A19. 1653 January 6: At night from the first to third watches, the white star was unobservable due to the moonlight. At the fourth and fifth watches, its shape and body (form) were extremely faint so could not be observed [Silgi]. (夜一更至三更, 白星爲月光所射, 不得看候. 四五更, 形體極熹微, 不得測候).

A20. 1653 January 7: At night from the first to third watches, the white star was unobservable due to the moonlight. At the fourth and fifth watches, its form was unobservable in detail because it had almost disappeared although it was not extinct [Silgi]. (夜一更至三更, 白星爲月光所射, 不得看候. 四更五更, 形體幾盡, 不得消滅, 不得詳候).

A21. 1653 January 8: At night the first watch, the Moon trespassed the mao constellation. The white star was unseen because its form had already disappeared [Silgi]. ((夜一更, 月犯昴星). 白星形體已盡不見).

References

Ahn SH. 2009. The first telescope in the Korean History I. Translation of Jeong’s report. J Astron Space Sci. 26(2):237–266 (in Korean).10.5140/JASS.2009.26.2.237Search in Google Scholar

Bahk UM, Mihn BH, Lee KW, Kim SH, Hyun JY, Kim YG. 2022. Statistical analysis for astronomical records of the Hyeonjong-Donggung-Ilgi (1649–1659). Publ Korean Astron Soc. 37(3):59–79 (in Korean).Search in Google Scholar

Choi GE, Lee KW, Mihn BH. 2018. Daylight observation of 1P/Halley in 1222. Planet Space Sci. 161:1–4.10.1016/j.pss.2018.06.003Search in Google Scholar

Halleio E. 1704. Astronomiae cometicae synopsis, autore Edmundo Halleio apud oxonienses. geometriae professore Saviliano, & Reg. Soc. S. Philos Trans. 24:1882–1899.10.1098/rstl.1704.0064Search in Google Scholar

Han BS. 2001. Arrangement of chronological tables on Korea. Gyeongsan: Yeungnam University Press (in Korean).Search in Google Scholar

Hasegawa I. 1979. Orbits of ancient and medieval comets. Publ Astron Soc Jpn. 31:257–270.Search in Google Scholar

Hasegawa I. 1980. Catalogue of ancient and naked-eye comets. Vistas Astron. 24:59–102.10.1016/0083-6656(80)90005-7Search in Google Scholar

Hasegawa I, Nakano S. 1995. Periodic comets found in historical records. Publ Astron Soc Jpn. 47:699–710.Search in Google Scholar

Hasegawa I, Nakano S. 2003. Orbit of periodic comet 153P/Ikeya-Zhang. Mon Not R Astron Soc. 345:883–888.10.1046/j.1365-8711.2003.07009.xSearch in Google Scholar

Hevelius J. 1668. Cometographia, Totam Naturam Cometarum; ··· Exhibens. Gedani: Typis Auctoris, & Sumptibus, Simon Reiniger.Search in Google Scholar

Hilton JL. 2005. Improving the visual magnitudes of the planets in the astronomical almanac. I. Mercury and Venus. Astron J. 129:2902–2906.10.1086/430212Search in Google Scholar

Ho PY. 1962. Ancient and Medieval observations of comets and novae in Chinese sources. Vistas Astron. 5:127–225.10.1016/0083-6656(62)90007-7Search in Google Scholar

Jeon SW. 1974. Science and technology in Korea: Traditional instruments and techniques. Cambridge: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Kanda S. 1935. Astronomical materials in Japanese history. Tokyo: Maruzen (in Japanese).Search in Google Scholar

Kiang T. 1972. The past orbit of Halley’s comet. Mem R Astron Soc. 76:27–66.10.1093/mnras/157.4.477Search in Google Scholar

Kim D. 2020. Analysis of Korean traditional planisphere, Cheonsang yeolcha bunya jido. MSc thesis. Seoul: Seoul National University, p. 39–127 (in Korean).Search in Google Scholar

Kronk GW. 1999. Cometography: A catalog of comets: Volume 1: Ancient – 1799. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Knobel EB. 1897. On some original unpublished observations of the comet of 1652. Mon Not R Astron Soc. 57:434–438.10.1093/mnras/57.6.434Search in Google Scholar

Knobel EB. 1918. The comet of 1652. Observatory. 41:139.Search in Google Scholar

Lee KW. 2012. Analysis of Korean records with Chinese equatorial coordinates. Astronomische Nachrichten. 333:648–659.10.1002/asna.201111700Search in Google Scholar

Lee KW. 2023. Astronomical phenomenon records from Sukjong’s Chunbang-Ilgi. J Korean Astron Soc. 56:75–89.Search in Google Scholar

Lee KW, Ahn YS, Yang HJ. 2012. Study on the system of night hours for decoding Korean astronomical records of 1625–1787. Adv Space Res. 48:592–600.10.1016/j.asr.2011.04.002Search in Google Scholar

Lee KW, Mihn BH, Ahn YS. 2014. Korean historical records on Halley’s comet revisited. J Astron Space Sci. 31(3):215–223.10.5140/JASS.2014.31.3.215Search in Google Scholar

Marsden GB. 1983. Catalog of cometary orbit. Hillside: Enslow Publishers.Search in Google Scholar

Martínez MJ, Marco FJ, Sicoli P, Gorelli R. 2022. New and improved orbits of historical comets: Late 4th and 5th century. Icarus. 384:11511210.1016/j.icarus.2022.115112Search in Google Scholar

Meeus J. 1998. Astronomical algorithms. Richmond: Willmann-Bell, Inc.Search in Google Scholar

Morrison LV, Stephenson FR. 2004. Historical values of the Earth’s clock error ΔT and the calculation of eclipses. J History Astron. 35:327–336.10.1177/002182860403500305Search in Google Scholar

Neuhäuser DL, Neuhäuser R, Mugrauer M, Harrak A, Chapman J. 2021. Orbit determination just from historical observations? Test case: The comet of AD 760 is identified as 1P/Halley. Icarus. 364:1141278.10.1016/j.icarus.2020.114278Search in Google Scholar

Pankenier DW, Xu Z, Jiang Y. 2008. Archaeoastronomy in East Asia: Historical observational records of comets and meteor showers from China, Japan, and Korea. Amherst: Cambria Press.Search in Google Scholar

Park SY, Chae JC. 2007. Analysis of Korean historical comet records. Publ Korean Astron Soc. 22(4):151–168 (in Korean).10.5303/PKAS.2007.22.4.151Search in Google Scholar

Pienaar WJB. 1948. Observations of the comet of 1652 recorded in the Journal of Van Riebeeck. Mon Notes Astron Soc South Afr. 7:10.Search in Google Scholar

Rufus WC. 1913. The celestial planisphere of King Yi Tai Jo. Trans Korea Branch R Asiatic Soc. 4:23–72.Search in Google Scholar

Sekiguchi R. 1917. Comets among ancient records of the Yi Dynasty of Joseon. Astron Her. 10:85–88 (in Japanese).Search in Google Scholar

Standish EM, Newhall XX, Williams JG, Folkner WF. 1997. JPL planetary and lunar ephemeris (CD-ROM). Richmond: Willmann-Bell, Inc.Search in Google Scholar

Weigelius ME, Schiltero JB. 1653. Commentatio astronomica de cometa novo qui sub finem anni 1652 lumine sub obscuro nobis illuxit. Jenae: Typis Georgii Sengenvvaldi.Search in Google Scholar

Williams J. 1871. Observations of comets from B.C. 611 to A.D. 1640, Extracted from the Chinese annals, translated, with introductory remarks, and an Appendix comprising tables for reducing Chinese time to European reckoning, and a Chinese celestial atlas. London: Strangeways and Walden.10.1093/mnras/32.1.32Search in Google Scholar

Yeomans DK, Kiang T. 1981. The long-term motion of comet Halley. Mon Not R Astron Soc. 197:633–646.10.1093/mnras/197.3.633Search in Google Scholar

Zolotova N, Sizonenko Y, Vokhmyanin M, Veselovsky I. 2018. Indirect solar wind measurements using archival cometary tail observations. Sol Phys. 293:85.10.1007/s11207-018-1307-4Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- A generalized super-twisting algorithm-based adaptive fixed-time controller for spacecraft pose tracking

- Retrograde infall of the intergalactic gas onto S-galaxy and activity of galactic nuclei

- Application of SDN-IP hybrid network multicast architecture in Commercial Aerospace Data Center

- Observations of comet C/1652 Y1 recorded in Korean histories

- Computing N-dimensional polytrope via power series

- Stability of granular media impacts morphological characteristics under different impact conditions

- Intelligent collision avoidance strategy for all-electric propulsion GEO satellite orbit transfer control

- Asteroids discovered in the Baldone Observatory between 2017 and 2022: The orbits of asteroid 428694 Saule and 330836 Orius

- Light curve modeling of the eclipsing binary systems V0876 Lyr, V3660 Oph, and V0988 Mon

- Modified Jeans instability and Friedmann equation from generalized Maxwellian distribution

- Special Issue: New Progress in Astrodynamics Applications - Part II

- Multidimensional visualization analysis based on large-scale GNSS data

- Parallel observations process of Tianwen-1 orbit determination

- A novel autonomous navigation constellation in the Earth–Moon system

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- A generalized super-twisting algorithm-based adaptive fixed-time controller for spacecraft pose tracking

- Retrograde infall of the intergalactic gas onto S-galaxy and activity of galactic nuclei

- Application of SDN-IP hybrid network multicast architecture in Commercial Aerospace Data Center

- Observations of comet C/1652 Y1 recorded in Korean histories

- Computing N-dimensional polytrope via power series

- Stability of granular media impacts morphological characteristics under different impact conditions

- Intelligent collision avoidance strategy for all-electric propulsion GEO satellite orbit transfer control

- Asteroids discovered in the Baldone Observatory between 2017 and 2022: The orbits of asteroid 428694 Saule and 330836 Orius

- Light curve modeling of the eclipsing binary systems V0876 Lyr, V3660 Oph, and V0988 Mon

- Modified Jeans instability and Friedmann equation from generalized Maxwellian distribution

- Special Issue: New Progress in Astrodynamics Applications - Part II

- Multidimensional visualization analysis based on large-scale GNSS data

- Parallel observations process of Tianwen-1 orbit determination

- A novel autonomous navigation constellation in the Earth–Moon system