Abstract

In planetary surfaces, oblique impact events are commonplace, and their study holds significant importance for understanding planetary impact processes and aiding in the design of landers and impactors. Current research predominantly focuses on simplified models to study the force and motion under vertical impact craters in terms of scale and impact loading. For oblique impacts, investigations have primarily concentrated on the final crater shape. However, the specific influence of impact load motion on particle bed movement and the precise impact angle’s effect on the ultimate crater shape during the impact process remain unclear. In this study, we used a custom-built oblique impact experimental setup to analyze changes in the velocity field of the particle bed and the horizontal movement of the impact load. Using quasi-static region to assess ellipticity, we aimed to reveal the state of particle movement during oblique impacts and explore the impact of impact angles and energies on crater formation. The results indicate that under large impact angles, the obliquely acquired kinetic energy is minimal, leading to a predominant static point source movement of the particle bed. At higher energy levels, the impact load primarily excavates downward, resulting in the formation of circular impact craters. These findings underscore the sensitivity of particle bed motion to impact angles, making it a crucial metric for assessing the impact of oblique angles on final crater morphology.

1 Introduction

From the photographs sent back by probes such as Chang’e-1, the lunar surface is evidently covered with craters of various sizes resulting from asteroid impacts. Their sizes and morphologies document moments from the distant past when celestial bodies were impacted. Many researchers use these features to trace the evolutionary history of celestial bodies, providing valuable information for planetary exploration and landing missions conducted by various countries. However, the process of crater formation is extremely complex. Since the study of impact loads colliding with particle beds can help humanity gain a more effective understanding of the fundamental dynamics involved in asteroid impacts on planetary surfaces, research on the fundamental dynamics of crater formation and the relationship between the motion of impacting objects and the resulting craters has gradually become a hot topic in the study of granular material mechanics (Ruizsuarez 2013, Hiroaki 2016, Van 2017).

In the majority of natural impact events, meteorites collide with a target surface at an oblique angle. From the perspective of celestial mechanics, moderately inclined impacts are considered common (Gilbert 1893). However, in the early stages of research, scholars initially simplified impacts to simple vertical collisions, focusing on the dynamics of impact loads and the description of crater morphology (Uehara et al., 2003, Walsh et al., 2003, Ambroso et al., 2004, Zheng et al., 2004, De Vet and De Bruyn 2007, Umbanhowar and Goldman 2010, Arakawa et al., 2020). Under conditions of vertical impact experiments, researchers, through experiments and simulations, divided the impact process into three stages, each dominated by different physical processes. The impact load strikes the surface of the particle bed during the first stage, with a short duration. The impact load penetrates the particle bed during the excavation stage, causing the impact crater to continuously expand outward. Finally, the impact crater undergoes a collapse stage under the influence of gravity, forming the ultimate impact crater (Melosh and Ivanov 1999, Pica et al., 2004).

The variation in impact angles significantly influences the trajectory of impact loads, the morphology and scale of impact craters, as well as the fundamental dynamic processes (Wang et al., 2012, Wang and Zheng 2013, Elbeshausen et al., 2013, Ye et al., 2015, 2016, Takizawa and Katsuragi 2023). In studies involving oblique impacts, Nishida et al., proposed through experiments and simulations that the post-oblique impact motion of impact loads primarily comprises three processes: penetration, sliding, and bouncing (Nishida et al., 2010, 2011). The penetration process involves the impact load making localized collisions with the particle bed surface, transferring a substantial amount of impact kinetic energy to the particle bed, causing splashing of bed particles, and penetrating through, resembling a fixed-point explosion source. In the penetration process, the primary motion mode of the impact load is downward penetration. The most typical model describing this process is a single, stationary point-source model proposed by Holsapple and Schmidt (1987), with the Maxwell Z model being the most commonly used point-source model. This model, resembling a fixed-point explosion, exhibits a circular flow center below the particle bed surface, moving only vertically as the impact crater grows (Maxwell 1976). In the sliding process, the impact load moves horizontally on the particle bed surface, transferring impact energy to the target surface. This leads to significant variations in the particle bed around the impact load, potentially elongating the shape of the impact crater and causing asymmetry. Anderson and Schultz (2006) proposed a moving point-source model to describe the sliding process in oblique impacts, as the impact point and the center of the impact crater mutually shift, resulting in the flow center simultaneously shifting both horizontally and vertically. Regarding the bouncing phenomenon, Soliman et al., (1976) conducted experimental studies indicating that impact loads on sand beds below 100 m/s do not exhibit rebound.

Furthermore, due to oblique impacts, it is necessary to consider the influence of the rotation of the impacting load on the dynamics and evolution of impact craters. Ye et al., conducted a study on the dynamics of a rotating impacting load obliquely impacting a two-dimensional granular medium using the discrete element method. They particularly investigated the influence of the rotational angular velocity on the penetration depth. Simulation results indicate that the incident rotation speed not only affects the velocity distribution characteristics of the impacted granular bed but also qualitatively influences the trajectory of the projectile. However, this angular velocity is critical, and regardless of the rotation direction, the rotation of the projectile always promotes its vertical movement without involving horizontal movement (Ye et al., 2012).

However, the aforementioned studies have only focused on the motion of the impact load itself. The influence of the impact load on the motion state of the particle bed and the determination of whether the particle bed changes conform to a point-source model or a moving point-source model remain unclear. Additionally, the specific effects of impact angles on the final shape of the impact crater are not well established.

In this article, the impact angle is above medium angle (≤30°), and the impact speed is 2–3 m/s, which is much lower than the critical velocity of about 6 m/s mentioned in Ye et al.’s article, and so there was no bouncing. This quasi-stationary zone serves as a transitional area between outward-expanding particles and inward-collapsing particles. Acting as a distinguishing marker for outward expansion and inward collapse, this zone effectively reveals the particle motion patterns during the impact process. Additionally, the quasi-stationary zone exhibits the characteristics of stable propagation, remaining unaffected by impact velocity and particle bed thickness. Therefore, it serves as a robust tool for observing changes in particle bed motion. The moment of cessation of the quasi-stationary zone corresponds to the instance when the collapse extent of the entire particle system reaches its maximum, signifying the ultimate formation of the impact crater (Yang et al., 2023, Zeng et al., 2022).

Building upon this discovery, this study employs the quasi-stationary zone as a powerful tool for observing changes in particle bed particle motion. It is used to assess the impact of impact loads on particle motion post-collision, investigate the influence of impact angles on crater formation, and explore the effects of energy on the formation process.

2 Experimental design and methods

2.1 Experimental system

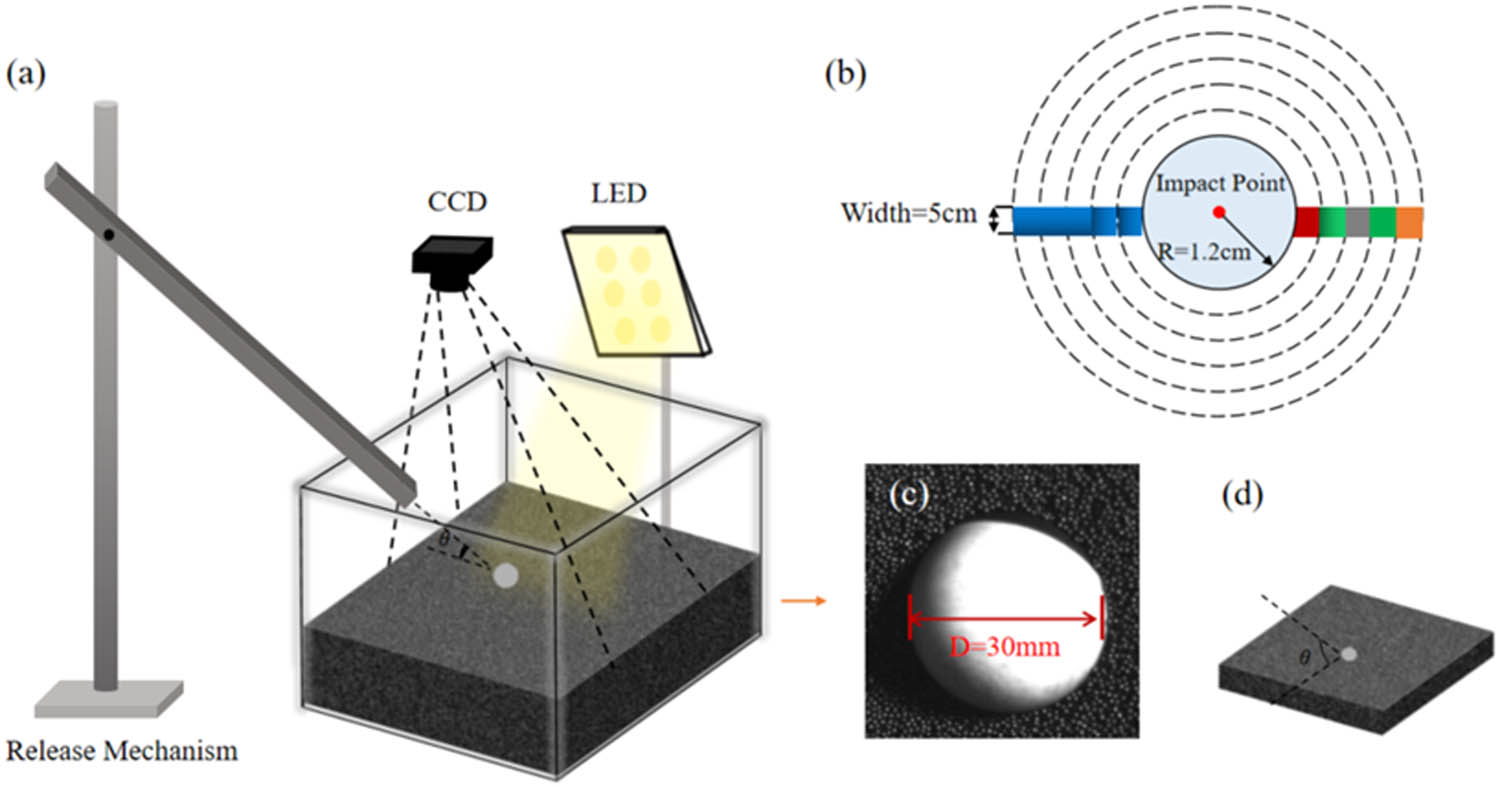

The experimental setup is shown in Figure 1, which consists of two main components: the impact device system and the imaging device system.

Schematic diagram of the oblique impact experimental setup: (a) schematic diagram of the impact system, (b) enlarged view of the characteristic region, (c) photograph showing the parameters of the impact loading and the granular particles in the bed, and (d) magnified view illustrating the angle of impact formed with the surface of the granular bed below the figure.

The impact device system primarily includes a stainless steel inclined chute (1 m), a glass box (with dimensions of 400 mm in length, 400 mm in width, and 300 mm in height), a protractor, and an adjustable stand for controlling the angle and height. In the experiment, black electroplated glass beads with an average diameter of 1 mm were used as the particles inside the glass box. The thickness of the particle bed (e) ranged from 2–4 cm. The impact load consisted of a high-strength POMM spherical shell with a diameter of 30 mm and a mass of 20 g. The range of impact heights was 50–80 cm, and the range of impact angles was from 30° to 90°. During the experiments, the impact load was released freely from the inclined chute at different heights and angles to impact the particle bed. A high-speed camera was positioned perpendicular to the surface of the particle bed to capture the entire process of the small ball impacting the particle bed surface.

To obtain higher-quality photos for better analysis, an light-emitting diode (LED) light source (SL-200 W) and a high-speed charge-coupled devices camera (Revealer 5F04M) were used in the imaging system. The camera had a frame rate of 317 fps and an exposure time of

Granular bed, impacting particle, and technical parameters

| Type | Parameter name | Data |

|---|---|---|

| Particle bed parameters | Volume fraction | 0.6 |

| Particle bed size |

|

|

| Particle bed thickness | 2–4 cm | |

| Particle density |

|

|

| Particle diameter | 1 mm (

|

|

| Impact load parameters | Impact load mass | 20 g |

| Impact load diameter | 30 mm | |

| Initial velocity at impact |

|

|

| Technical parameters | Time resolution | 317 fps (camera frame rate) |

| Spatial resolution |

|

The selection of the impact load’s velocity is based on measurements in real natural conditions, defined by the Froude number, where

where

2.2 Particle image velocimetry (PIV)

PIV is a transient, multipoint, non-contact fluid mechanics measurement technique. It involves continuously capturing images of particles exposed to multiple exposures using an imaging-recording system. Subsequently, the captured PIV images are analyzed using image cross-correlation methods to determine the average displacement of particle images in each small region. This information is then used to establish the two-dimensional fluid velocity distribution across the entire area of the flow field plane.

By analyzing consecutive pairs of exposed images, the velocity vector distribution of the specified velocity field can be obtained. Assuming that tracer particle A undergoes displacements

PIV technology is relatively simple to implement in experiments, requiring only a light source to illuminate the particles and a high-speed camera for image capture, which can then be analyzed (Thielicke and Stamhuis 2014).

The velocities obtained through PIV represent projections on the coordinate plane. Our research primarily focuses on the surface flow characteristics and particle dynamics within a two-dimensional plane. The two-dimensional velocity field also discloses pertinent features of particle motion on the surface of the particle bed, encompassing flow characteristics, particle dynamics, and interactions.

Our emphasis is on observing the trend changes within the quasi-static region on the surface of the particle bed. Simultaneously, we follow the experimental approach outlined by Yang et al., (2023).

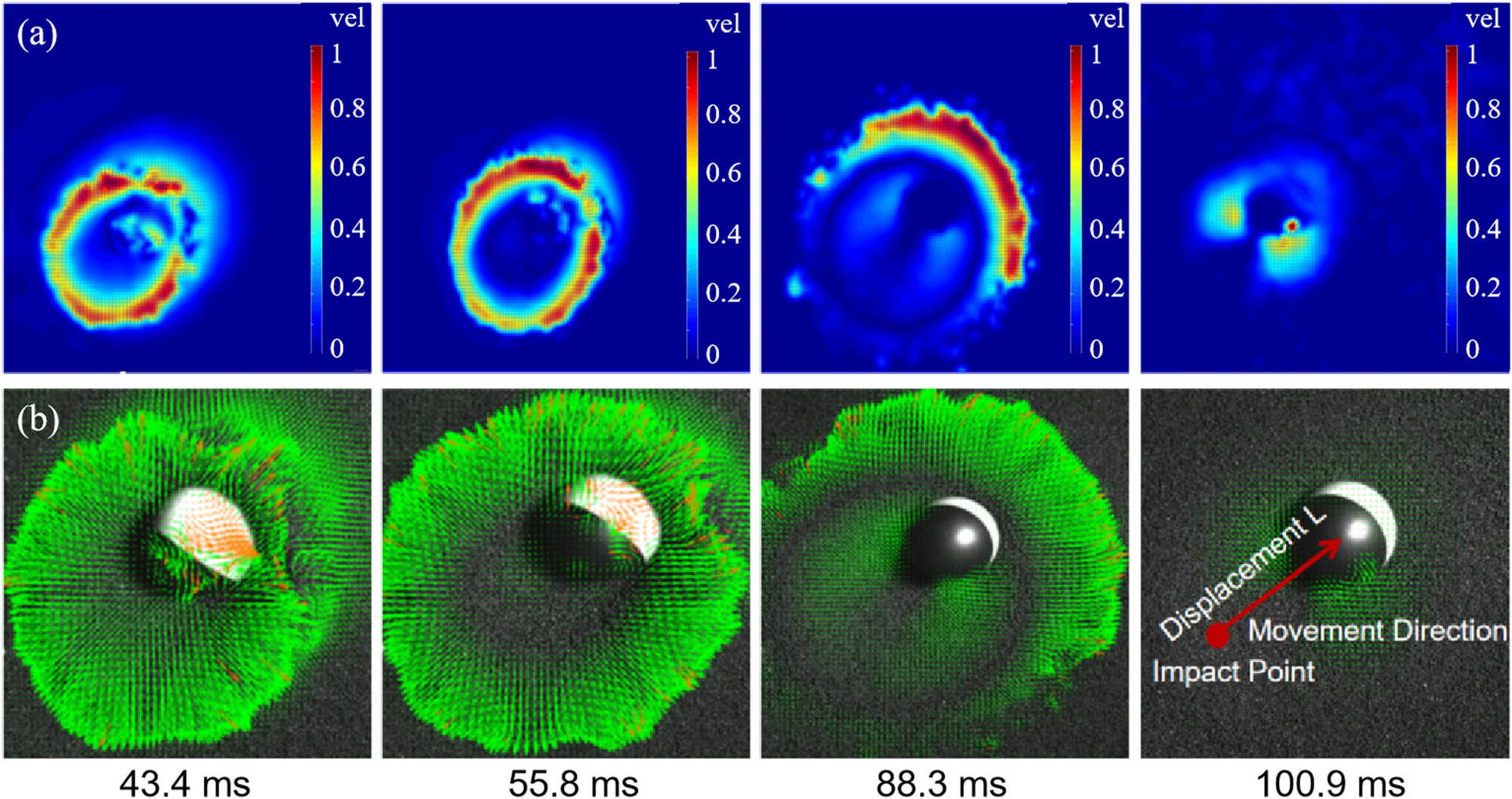

Figure 2(a) depicts the process of impact crater formation, showing the evolution of an impact crater over time. The center of the impact crater continuously shifts. This is due to the presence of additional motion components in the collision direction during the oblique impact process, causing the center of the flow field to shift toward the oblique impact direction. As a result of the oblique angle, the flow field undergoes lateral expansion. With the migration of the flow field center, a circular impact crater is formed.

A series of consecutive process images of oblique impact on the granular bed at a 30° angle from a height of 50 cm. The red arrow indicates the direction of motion of the impact loading on the surface of the granular bed: (a) image captured by a high-speed camera, after processing, is rendered as a color image and (b) image after PIV processing figure (0.11 mm/pixel).

Processing the captured images using PIV, the flow field vector map reveals the dispersion and collapse processes of the particle bed after impact, along with changes in velocity and direction across the entire particle bed. In Figure 2(b), it is observed that before 43.4 ms, the particle bed primarily exhibits outward radial expansion, displaying a trend of dispersion. When the particle medium is impacted by an object, it gains sufficient kinetic energy to expand radially and splatter vertically due to oblique impact. At this point, particles on the bed surface are ejected in all directions, and the ejected particles continue to expand outward, with smaller expansion velocities closer to the impact point. Additionally, there is a noticeable difference in velocity between the front and rear directions of the impact load’s movement. The front end of the impact load’s movement exhibits greater divergence in velocity during this stage, mainly due to the excavation effect of the impact crater. After 43.4 ms, the stable state of the side walls is disrupted, with the rear end collapsing first. As more expanding particles lose velocity, the number of collapsing particles gradually increases, and the collapse area continues to expand. When the collapse area reaches its maximum, the particle system enters a slow collapse phase, and the area gradually shrinks until all particles come to a standstill.

To gain a deeper understanding of the motion characteristics of the particle bed, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of the continuous five-frame velocity vector field data before and after the movement of the impact load. Specifically, as depicted in Figure 1(b), with the impact center as the reference point, five rectangular regions, each measuring 0.5 cm in length and 0.5 cm in width, were selected on both sides of the impact load. The average velocity within each region was calculated using the method outlined in Formula (4):

where

In oblique impact experiments, it is essential not only to focus on the movement characteristics of the particle bed but also to consider the post-impact motion of the impact load itself. Therefore, it is necessary to measure the sliding displacement of the load. By calibrating the pixel size in the images with the actual distance, the actual sliding distance (

2.3 Impact results

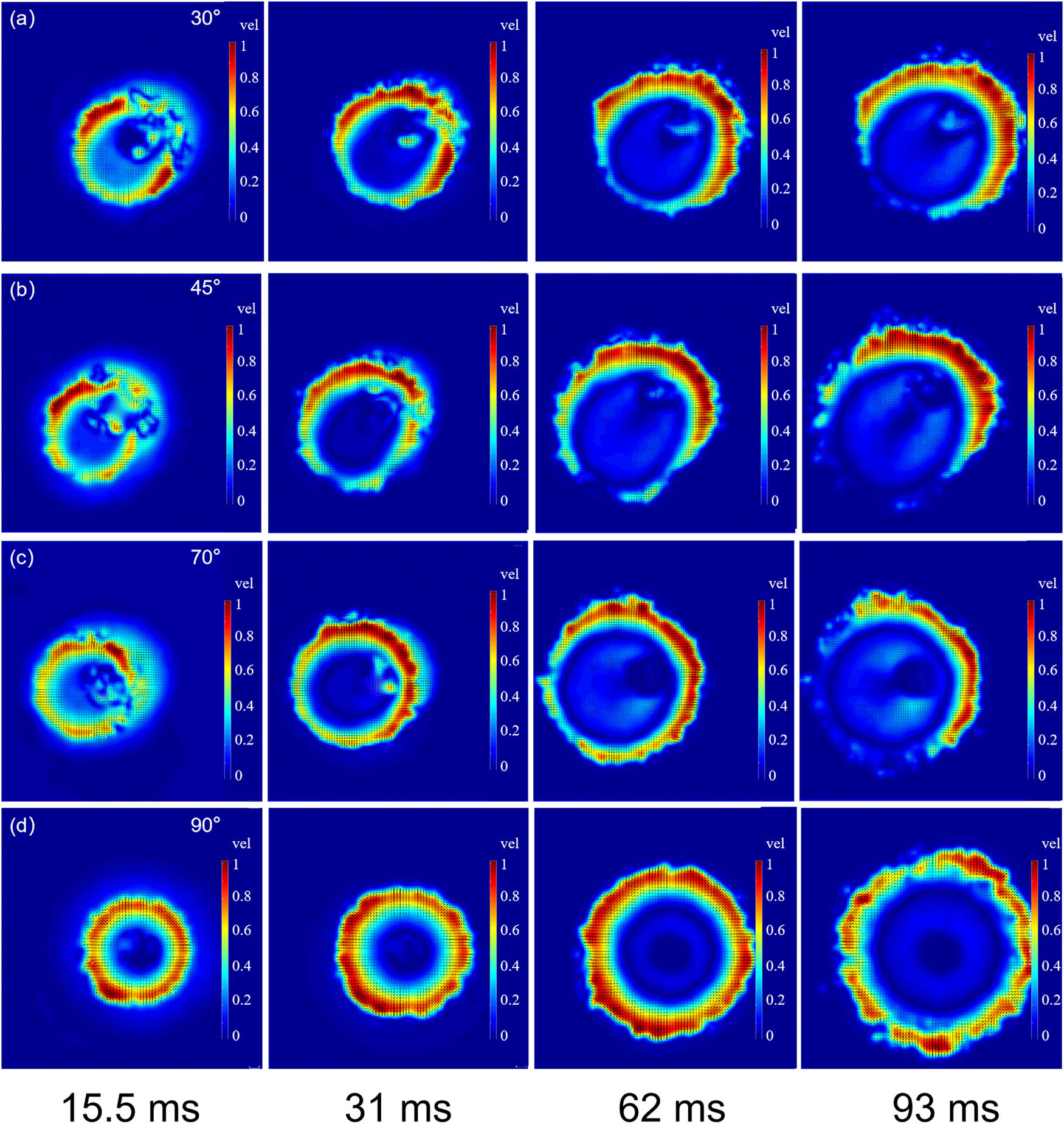

Figure 3 displays a set of color images processed from a series of shots captured by a high-speed camera. These images depict the entire impact-collapse process experienced by a bed of contacting particles subjected to oblique impact loads from different angles. The duration of the entire process lasts approximately 150 ms. Following the oblique collision of the impact load with the particle bed, a symmetric impact crater forms around the impact point and continuously enlarges over time. After the outward expansion phase, the sidewall regions begin to collapse under the influence of gravity, and the center of the impact crater migrates horizontally with the movement of the impact load.

At a height of 80 cm, images capture the entire process of impact-collapse experienced by a bed of particles subjected to impact loads: (a) impact angle of 30°, (b) 45°, (c) 70°, and (d) 90° (0.11 mm/pixel).

At an impact angle of 90° (Figure 3(d)), the crater walls collapse symmetrically in all directions, resulting in noticeable symmetry around the edges of the impact crater. For angles below 90°, before 62 ms, the collapse in the forward and backward directions of the impact load’s movement is significantly asymmetric. Particles in the front end of the particle bed in the direction of impact load movement continue to expand outward, while the rear end has already started collapsing (Figures 3(a)–(c)). In the later stages, beyond 93 ms, the collapse of impact craters at all angles gradually becomes more symmetric.

Due to the relatively small impact velocity in our experiments, far from reaching the bouncing phenomenon observed in the experiments conducted by Soliman et al., 1976. Therefore, in our experiments, the two primary motion states of the impact load resulted in the formation of impact craters. During the impact and penetration phases, a portion of the energy of the impact load drives it to penetrate and excavate, while another portion of the energy propels the impact load to slide horizontally along the surface of the particle bed, leading to the early formation of elliptical impact craters.

To better understand the relationship between the motion patterns of impact loads in the particle bed under oblique impacts and the surface of the particle bed, it is essential to describe the geometric and kinematic features in the particle flow field and their significance. By employing PIV technology for analyzing characteristic regions within the particle medium, one can observe a transitional region during the impact process where particles are spreading outward and collapsing inward. This region is referred to as the quasi-static region. The propagation of the quasi-static region reveals the motion patterns of particles during the impact process. Hence, using the changes in the shape of the quasi-static region can be a viable method for determining the motion of the impact load.

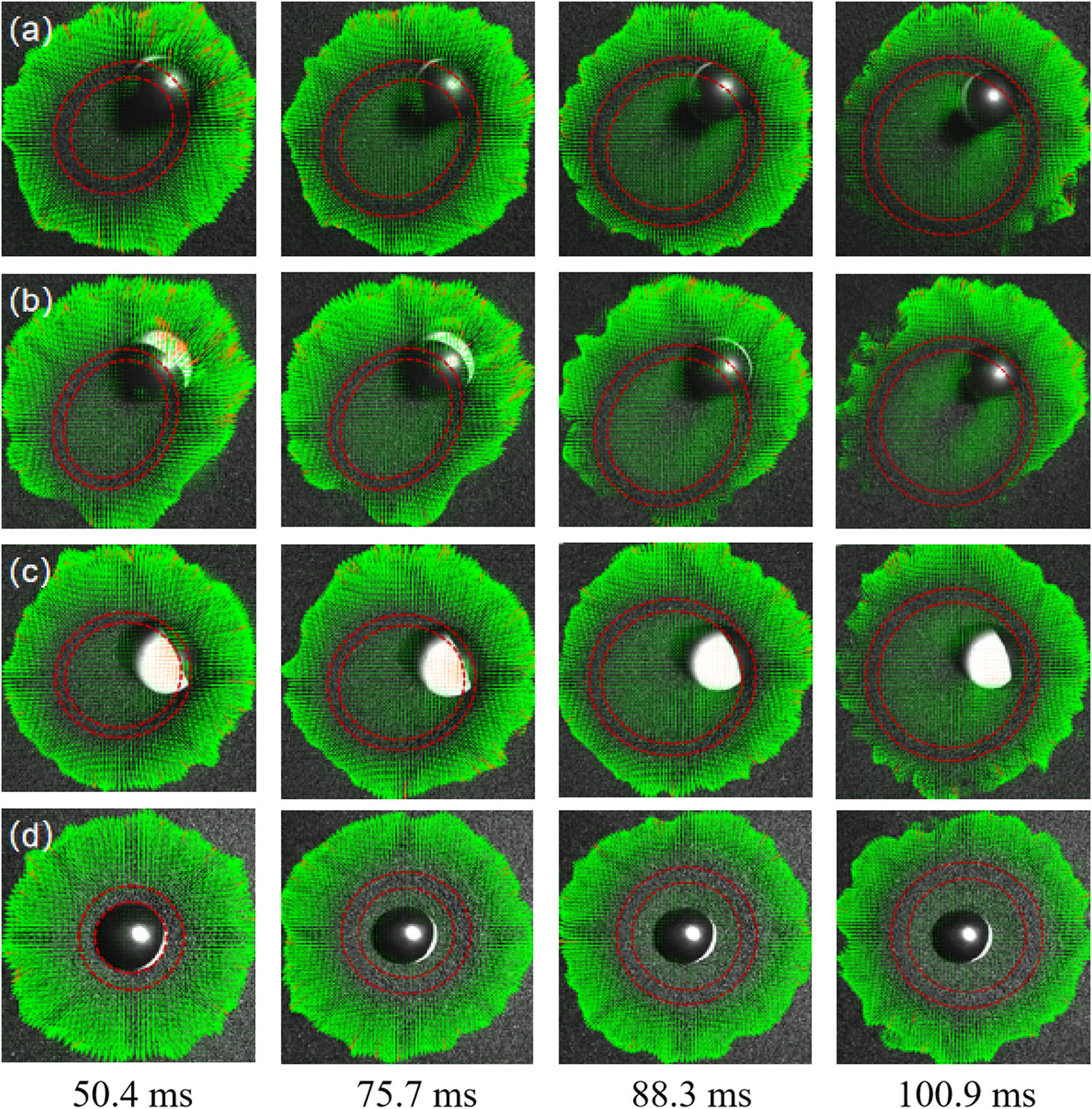

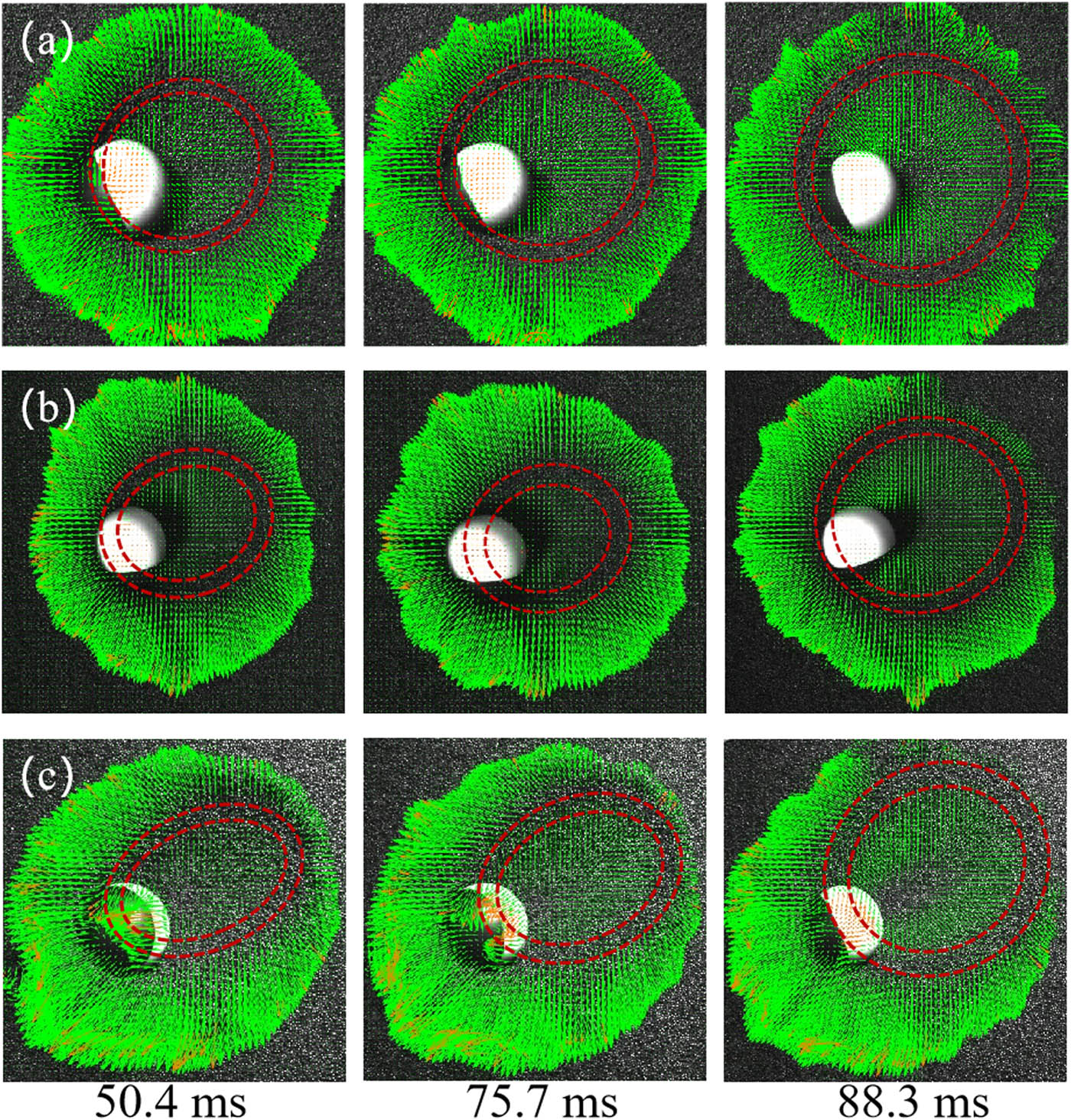

Figure 4 displays the velocity vector maps obtained through PIV analysis of the impact crater surface at the same height (50 cm) for (a) 30°, (b) 45°, (c) 75°, and (d) 90° (vertical) impact angles. Figure 5 provides the velocity vector maps obtained for different thicknesses. The quasi-static zone is then delineated with red dashed lines, showing distinct shapes at different angles and gradually evolving into a circular shape over time. Describing the shapes of the quasi-static region at different time intervals and angles can provide a powerful tool for understanding the motion state of impact loads after striking the particle bed and for characterizing the final impact crater.

Impact crater formation process when the impact load is released freely at a height of 50 cm and impacts the particle bed. The images show the velocity field evolution planar graph at different angles after PIV processing: (a) 30°, (b) 45°, (c) 70°, and (d) 90°. The red dotted line is the quasi-static region (0.11 mm/pixel).

Schematic diagrams showing the evolution of the quasi-static region over time, after undergoing PIV processing, for the impact loading at the same height (50 cm), same angle (45°), and varying granular bed thicknesses of (a) 2 cm, (b) 3 cm, and (c) 4 cm (0.11 mm/pixel).

3 Experimental results and discussion

3.1 Kinematic measurements

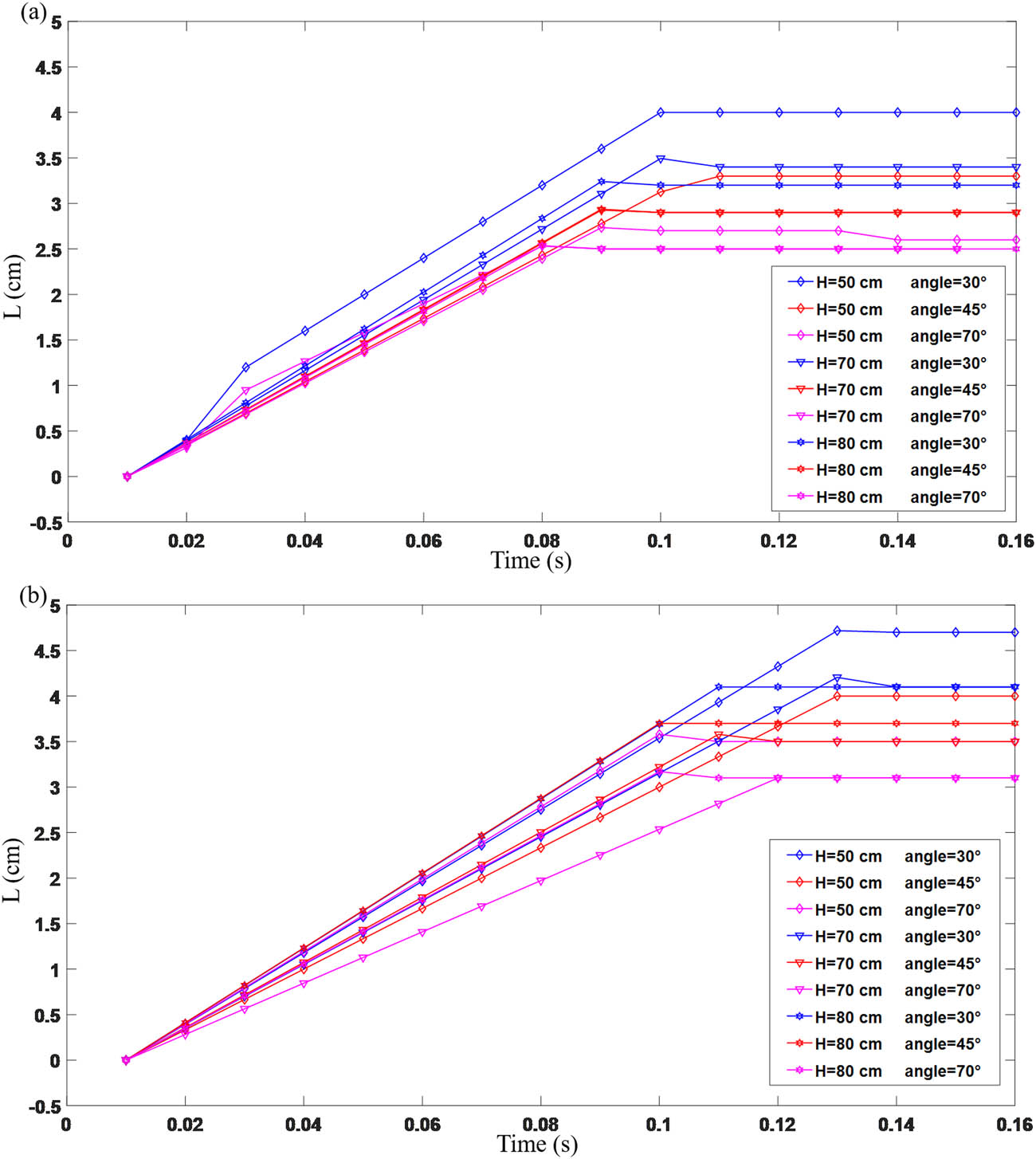

The post-impact motion states can be distinguished by analyzing the overall trajectory of the impact load. Figure 6(a) and (b) depicts the variations of the horizontal displacement, denoted as

Horizontal sliding distance of the impact loading after impact at various heights and angles: (a) for a granular bed thickness of 3 cm and (b) for a granular bed thickness of 4 cm.

For instance, under an impact angle of 45° at a height of 70 cm, with a particle bed thickness of 3 cm, the impact load slid a distance of 3.4 cm and came to a stop in 0.08 s. Under the same conditions, with a particle bed thickness of 4 cm, the impact load slid a distance of 4.1 cm and stopped in 0.1 s.

These findings suggest a clear correlation between the impact angle, particle bed thickness, and the horizontal motion of the impact load. As the angle decreases and the particle bed thickness increases, the impact load tends to travel a greater distance before coming to a halt. These results are crucial for understanding the dynamics of impact loads and their effects on the particle bed.

Increasing the thickness of the particle bed provides greater lateral constraint to the impact load, resulting in a longer stopping time for the impact load. The increased lateral constraint allows the impact load to slide more smoothly on the particle bed surface, thus extending the sliding distance. This is because when the particle bed thickens, it usually increases the force chains between particles. The particles within the particle bed are interconnected by force chains, forming a network structure within the bed. Increasing the thickness of the particle bed involves more particles in this network structure, thereby enhancing the overall internal connectivity of the entire particle bed. This can increase the overall stiffness and stability of the particle bed. This allows the impact load to maintain a longer motion on the particle bed surface. In addition, the gaps in the sand created by the ball as it passes through further fluidize the sand, effectively reducing the resistance to the ball. The trajectory of the impact load is strongly influenced by the surrounding environment. The air around the impact load suspends particles in the particle bed, thereby effectively reducing the resistance on the ball. As a result, the impact load can slide a greater distance on the particle bed surface. This is why, the ellipse in Figure 5(c) is more elongated compared to Figure 5(a) and (b). Additionally, in the later stages, when the particle bed thickness is lower (Figure 5(a)), the quasi-static region has already transitioned into a circular shape, whereas in thicker particle beds (Figure 5(b) and (c)), the quasi-static region is still in the process of transitioning from an ellipse to a circular shape.

Measuring the forces acting on the impact load after impact is challenging. Surface roughness at different positions on the particle bed and the unevenness of the particle fill can often lead to changes in the velocity and trajectory of the impact load. Furthermore, the final size of the impact crater cannot be directly correlated with the kinetic energy of the impact load. Typically, the collapse of the transient impact crater further increases the crater’s diameter while reducing its volume and depth. Therefore, analyzing the impact load alone is insufficient to fully understand the post-impact motion state. The subsequent motion of the load is influenced by various factors. Analyzing the particle bed and examining the motion of particles within the bed after impact are essential for gaining a deeper understanding of the post-impact motion of the impact load.

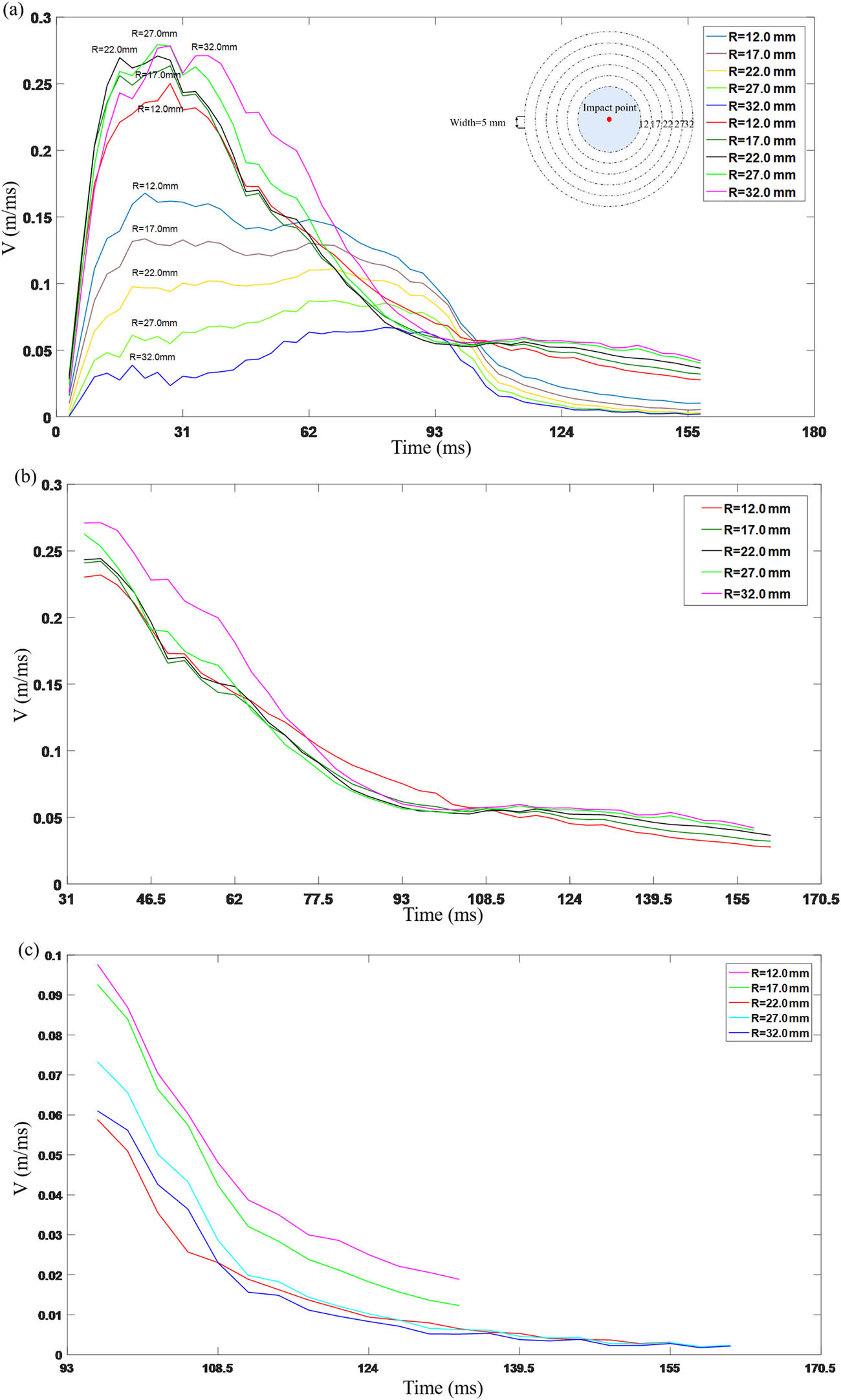

Figure 7 illustrates the variation in velocity over time for a fixed region on the particle bed throughout the entire impact-collapse process. The data shown in the figure are obtained under the experimental conditions of an impact height of 50 cm, particle bed thickness of 3 cm, impact angle of 45°, and a region located 12 mm away from the center point, with each rectangular region measuring 5 mm in length and 5 mm in width, as shown in Figure 1(b). In the figure, the colored curves represent the horizontal movement direction of the impact load (with the front end being the impact load’s moving direction).

(a) Variation of velocities over time in the fixed region of the granular bed during the impact-crumbling process. Subsequently, in (b), the velocity curve illustrates the collapsing speed at the front end of the impact point, while in (c), the velocity curve showcases the collapsing speed at the rear end of the impact point.

According to Figure 7, it is evident that both the front and rear velocities undergo two processes: velocity increase and velocity decay in the horizontal movement direction of the impact load. It can be observed that during the collision phase, the front-end velocity experiences a significantly greater increase than the rear-end. This is attributed to the proximity of the front-end to the impact load, where the impact energy is concentrated in the oblique direction, resulting in a higher energy level in this region. The energy transfer from the impact load to the particle bed accelerates particles, causing a larger acceleration for the front-end velocity. This corresponds to the early elliptical state as shown in Figure 5.

Furthermore, it is observed that different particles at various positions reach their maximum velocities at the same moment during the entire impact-collapse process, which is approximately the moment when particle collapse begins. However, the velocity decay of the front and rear collapse is not uniform. It is found in Figure 7(b) that at the front of the impact point, the velocity decay of the particles follows a linear process with a constant decay rate, given by:

At approximately 102.3 ms, the particle collapse begins to enter a slow phase. However, in the rear regions around the impact point, there is a period of gradual collapse phase, and after 93 ms, the velocities at various points on the particle bed start to undergo a steady decay process with a constant decay rate, as shown in Figure 7(c):

Due to the significant difference in growth and decay rates between the two, during the collapse phase, intersection points are observed in Figure 7 at the front and rear of the impact point. This is because during the oblique impact crater formation process, the outward excavation flow and the inward correction flow do not occur simultaneously in every direction. The oblique impact process leads to different velocity changes in the bed surface particles on either side of the impact point. The velocity change of the particles on the bed surface in front of the impact point is more severe than that of the particles at the rear, and the collapse of the particles on one side of the impact point occurs only after the impact load slides a certain distance in the horizontal direction of impact.

Because the front end is closer to the impact load, it receives more impact energy, allowing the bed of particles to gain more energy for splashing and collapsing. As time progresses, some energy is still being supplied to the bed of particles near the impact load, leading to a slow collapse phase. In the rear direction, far from the impact load, the energy received is smaller, resulting in a much slower growth rate than in the front region. In the later stages, collapse occurs only under the influence of gravity, and after a certain period, the rate reaches zero. The collapse at the front covers the portion that was elongated by the impact load earlier, resulting in the circular formation observed in Figures 4 and 5 in the later stages.

3.2 Ellipticity of the quasi-static region

The dissipation of impact energy pathways is influenced by the proximity of particles or the influence of the impact load. For instance, loose particle packing may lead to compaction between particles, gradually dissipating energy through friction, resulting in an overall cushioning effect on the impact load. On the other hand, denser particle packing may allow forces to be directly transmitted along force chains, resulting in a harder impact behavior, similar to solid impacts. These factors affect the post-impact motion of the impact load and the formation of impact craters.

We investigate the post-impact motion state of the particle bed after oblique impact for various target thicknesses and impact energies (primarily influenced by impact load height). The performance of the impact load and the characteristics of the impact target can influence the motion state of the impact load, thus affecting the efficiency of impact crater formation. In this study, we consider only two initial conditions (impact angle and impact height) and one system variable (particle bed thickness) to explore post-impact motion states.

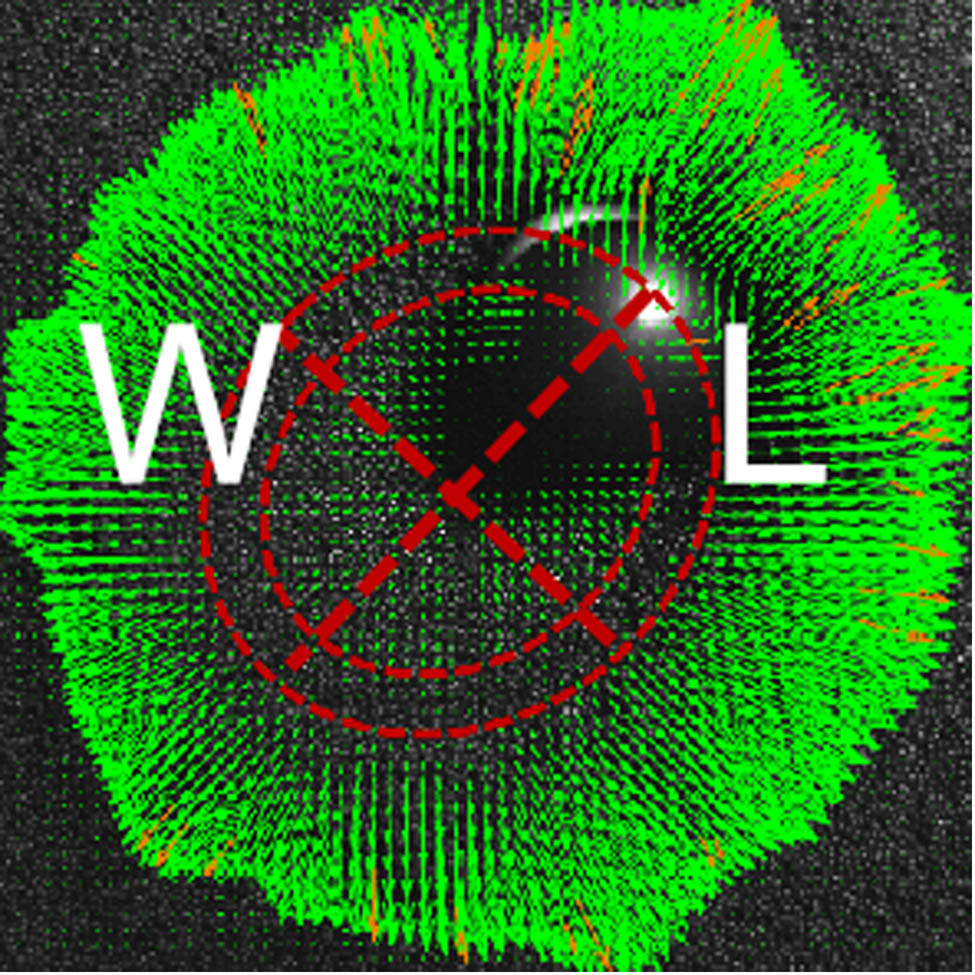

The shape analysis of the quasi-static region is used to understand how different factors affect the particle bed after impact. To better distinguish between circular and elliptical shapes of the quasi-static region, we analyze their ellipticity, defined as the length divided by their width. A threshold must be defined for ellipticity, and this is arbitrary choice, in Figure 8. To remain consistent with previous work, we follow the definition by Bottke et al., (2000) that considers it an ellipse if the length-to-width ratio is greater than or equal to 1.1.

Diagram illustrating the quasi-static region, where W represents the width of the quasi-static region, and L represents the length of the quasi-static region (0.11 mm/pixel).

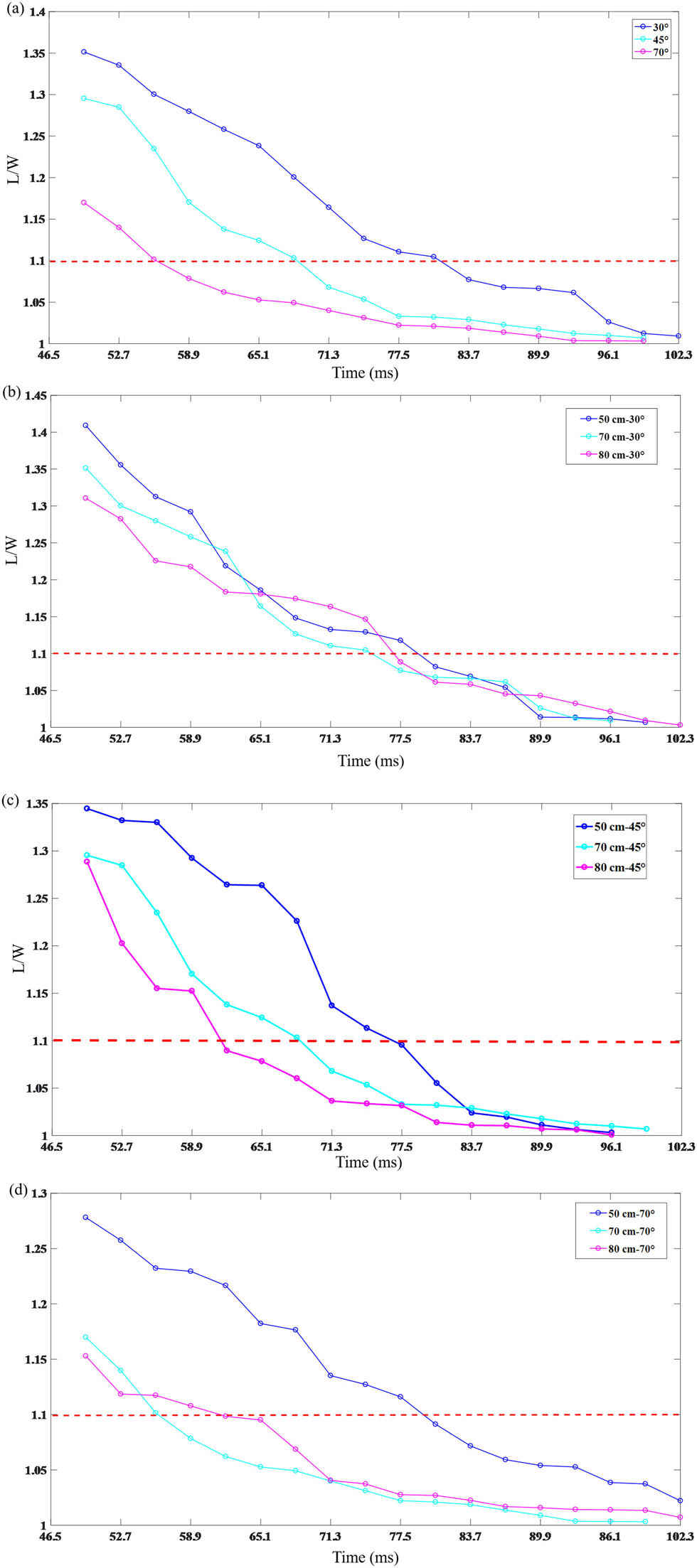

Figure 9 depicts the evolution of ellipticity of the quasi-static region over time for different impact angles. In all cases (except for vertical impact at 90°), elliptical cavities form in the early stages, consistent with the early elliptical shape observed in Figure 4. Smaller impact angles result in larger maximum ellipticities, and they reach an ellipticity of 1.1 later in time. As the impact crater further forms, the ellipticity of the quasi-static region decreases over time.

Variation of ellipticity of the quasi-stationary region with time: (a) Impact load is released freely at a height of 80 cm, and the angle is 30°, 45°, and 70°. (b), (c), and (d) are the results of 50, 70, and 80 cm shock at 30°, 45°, and 70°, respectively, where the red dotted line is the demarcation line between the defined ellipse and the circle with an ellipticity of 1.1.

For example, in Figure 9(a) depicting impacts at various angles at a height of 80 cm, early in the impact crater formation, the ellipticity is around 1.35 for a 30° impact and around 1.17 for a 70° impact. Moreover, the time interval for both cases to reach an ellipticity of 1.1 is relatively large, approximately 30 ms.

Simultaneously, it is observed that at the same angle, with increasing height, the ellipticity becomes smaller than at the same lower height at the same moment and reaches 1.1 more quickly, transitioning to a circular shape. Additionally, at larger angles (70°), it is found that ellipticity is more affected by height, as shown in Figure 9(d).

This indicates that in cases of higher energy, most of the momentum of the impact load rapidly transfers to the particle bed during the collision phase, resulting in intense motion of the particle bed, primarily downward excavation. Consequently, it can only obtain a smaller amount of energy for horizontal movement on the particle bed surface. The flow field within the particle bed is mainly dominated by motion originating from a static point source. Therefore, it is observed that under the same impact angle, higher impact heights result in symmetrically circular quasi-static region. This also demonstrates that under high-angle impacts, the kinetic energy acquired obliquely is relatively low, and the particle bed flow field is dominated by motion originating from a static point source. Hence, the quasi-static region appears circular. In the experiments, all formed impact craters are influenced by gravity. The impact height can be used to study how energy affects the formation of impact craters dominated by gravity. Figure 9(c) shows the evolution of ellipticity of the quasi-static region with time for impacts at a

When the impact height is higher, at the same moment, the ellipticity is smaller, and the time it takes to reach an ellipticity of 1.1 is shorter. Therefore, with a higher impact height, the quasi-static region becomes closer to a circular shape earlier. This also indicates that when the energy is higher, at the moment, the impact load contacts the particle bed, a large amount of energy is transferred to the particle bed, causing significant changes in the particle bed, mainly in the form of downward excavation and penetration. The impact load itself retains only a small amount of energy for horizontal sliding. The quasi-stationary region is less affected by the horizontal motion of the impact load; hence, it reaches a circular shape more quickly.

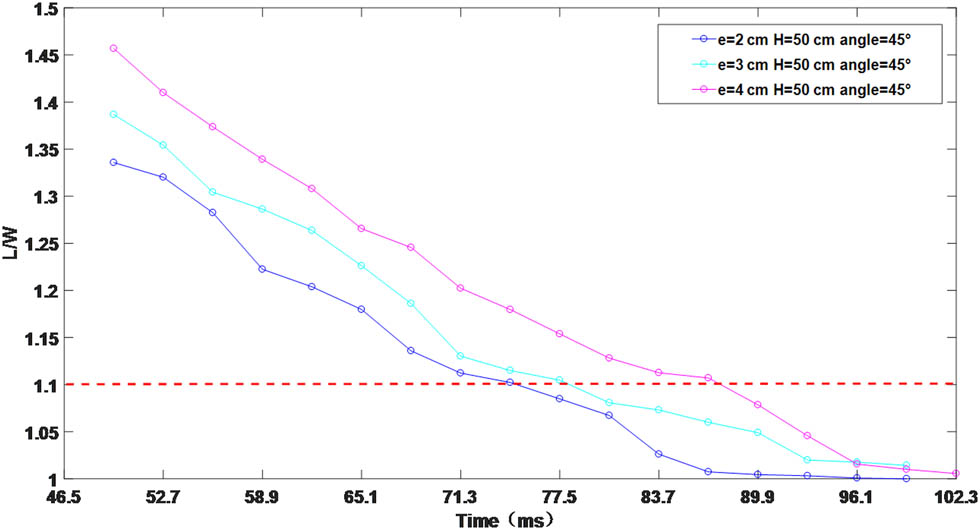

To discuss the impact of the characteristics of the target on the post-impact motion, the thickness of the particle bed varied. Figure 10 shows the change in the ellipticity of the quasi-stationary region over time for particle bed thicknesses of 2, 3, and 4 cm. The results indicate that the post-impact motion of the quasi-stationary region is significantly different at different thicknesses. For example, early on, when the particle bed thickness is 2, 3, and 4 cm, the ellipticity of the quasi-stationary region is 1.33, 1.39, and 1.46, respectively.

Variation of ellipticity of the quasi-static region over time for impact loading at an angle of 45° on granular beds with thicknesses of 2, 3, and 4 cm at an impact height of 50 cm.

As the thickness of the granular bed increases, the ellipticity of the quasi-static region becomes greater. This indicates that in thicker granular beds, the range of horizontal movement of the impact load on the surface is broader.

3.3 Discussion of regularities

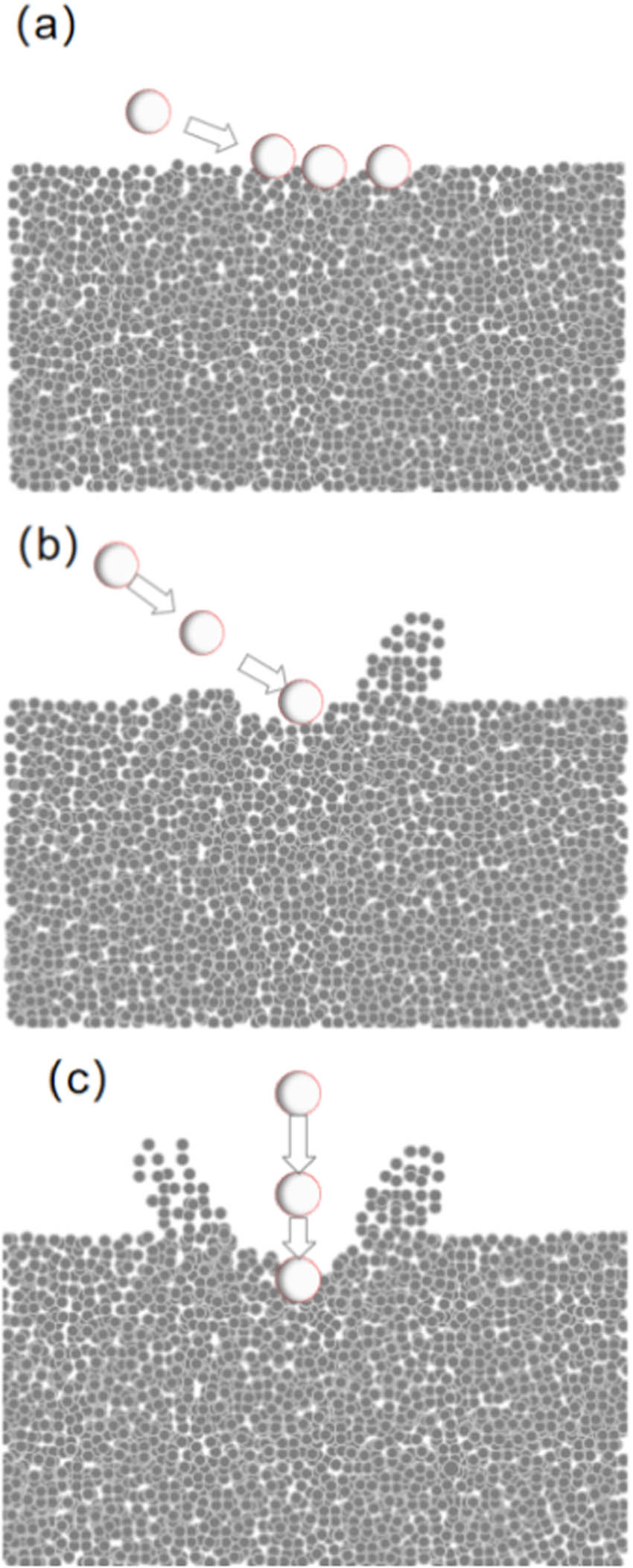

Figure 11 illustrates various post-impact motion states of the impact load within the granular bed at different impact angles, specifically θ = 30°, θ = 70°, and θ = 90°.When the impact angle is θ = 30° (Figure 11(a)), the penetration depth of the impact load is minimal, and it moves almost horizontally along the surface of the granular bed. The impact load cannot penetrate the target deeply, and only a small portion of the impact energy is transferred to the target. This results in the early formation of an elliptical impact crater, with later collapse gradually covering the initial shape.

Post-impact motion of the load: (a) motion state at 30°, (b) motion state at 70°, and (c) motion state at 90°.

At a larger angle (θ = 70°), as shown in Figure 11(b), the impact load penetrates the granular bed while sliding horizontally, but the sliding distance is relatively short. Finally, in the case of a vertical impact (θ = 90°) depicted in Figure 11(c), the impact load penetrates the granular bed vertically, forming a symmetrical impact crater.

Based on the aforementioned analysis, we utilize a characteristic region within the granular bed – the quasi-static region – to determine the primary motion state of the impact load within the granular bed based on its shape variations under various conditions. We have established that the key parameters affecting the efficiency of impact crater formation are the thickness of the granular bed and the impact energy of the load. These parameters not only affect the impact load but also have a profound influence on the motion state of the granular bed.

While the timing of the appearance of the quasi-static region remains unaffected by changes in impact velocity and granular bed thickness, the size and shape of the quasi-static region are correlated with granular bed thickness, impact energy, and impact angle. Through an analysis of how impact height and granular bed thickness influence the post-impact motion of the impact load, it is evident that both factors significantly affect the shape variations of the quasi-static region, thereby revealing substantial changes in the motion state of the impact load. It is found that with thicker granular beds, the horizontal sliding range is larger, whereas higher impact heights result in deeper penetration of the impact load and a smaller horizontal sliding range.

The transition in the shape of the quasi-static region from elliptical to circular suggests that during oblique impacts, the initial release of shock waves near the impact point is strongly asymmetric and elongated. Only after the impact load has moved a certain distance from the initial contact point does the collapse progress toward greater symmetry. This is because the initiation of impact crater formation is initially dominated by a moving point source model, and as the impact load comes to rest and transitions into the later stage of granular bed excavation, the impact crater gradually becomes dominated by a static point source. Therefore, it can be observed that the overall shape of the impact craters generated in the experiments remains circular in the plane.

Clearly, in oblique impacts at moderate angles (≥30°), horizontal momentum does not play a significant role in determining the overall shape of the impact crater. Energy is transferred symmetrically and nearly instantaneously, primarily dominated by the static point source model, ultimately forming a circular impact crater shape.

4 Conclusion

In the study of the impact load’s motion state and its influence on granular bed changes following impact, we sought to determine whether the granular bed change process aligns more closely with a point source model or a moving point source model. This, in turn, allowed us to investigate its impact on the ultimate formation of impact crater morphology.

This research focused on a characteristic region during the impact process, namely, the quasi-static region, to examine the effects of impact angle and impact energy on impact crater formation. The experimental results have demonstrated that the thickness of the granular bed and the impact energy not only affect the impact load but also significantly influence the motion state of the granular bed. The size and shape of the quasi-static region are correlated with granular bed thickness, impact energy, and impact angle. All three factors have a notable impact on the shape variations of the quasi-static region and bring about significant changes in the primary motion state of the impact load.

Through the study of the transition in the shape of the quasi-static region from elliptical to circular, the results indicate that during oblique impact processes, the impact energy released in the first stage is strongly asymmetrical near the impact point during oblique impact. Only after the impact load has moved a certain distance from the initial contact point does the collapse progress toward greater symmetry. This phenomenon arises because the initial stages of impact crater formation conform to a moving point source model, while in the later stages of granular bed collapse, as the impact load comes to a stop, the impact crater gradually conforms to a static point source model. It is evident that the overall shape of the impact craters generated in the experiments remains circular.

This suggests that in oblique impacts at moderate angles (≥30°), horizontal momentum does not play a significant role in determining the overall shape of the impact crater. Energy is transferred symmetrically and almost instantaneously, resembling a fixed-point explosion, consistent with the static point source model, ultimately resulting in a circular impact crater.

-

Funding information: This work has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (12072200, 12002213).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. YW: experimental design – experimental operation – data analysis – writing original draft; RL: writing review and editing; ZC: writing review and editing; HY: funding acquisition, resources and writing-review and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Ambroso MA, Santore CR, Abate AR, et al. 2004. Penetration depth for shallow impact cratering. Phys Rev E. 71(5 Pt 1):051305. 10.1103/PhysRevE.71.051305Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Anderson JLB, Schultz PH. 2006. Flow-field center migration during vertical and oblique impacts. Int J Impact Eng. 33(12):35–44. 10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2006.09.022Search in Google Scholar

Arakawa M, Saiki T, Wada K, Ogawa K, et al. 2020. An artificial impact on the asteroid (162173) Ryugu formed a crater in the gravity-dominated regime. Science. 368(6486):67–71. 10.1126/science.aaz1701Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Bottke WF, Love SG, Tytell D, et al. 2000. Interpreting the elliptical crater populations on Mars, Venus, and the Moon. Icarus. 145(1):108–121. 10.1006/icar.1999.6323Search in Google Scholar

De Vet SD, De Bruyn JR. 2007. Shape of impact craters in granular media. Phys Rev. E. 76(4 Pt 1):041306–041312. 10.1103/PhysRevE.76.041306Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Elbeshausen D, Kai W, Collins GS. 2013. The transition from circular to elliptical impact craters. JGR Planets. 118(11):2295–2309. 10.1002/2013JE004477Search in Google Scholar

Gilbert GK. 1893. The moonas face: a study of the origin of its feature. Massachusetts, Cambridge: Harvard University. pp. 80–87. Search in Google Scholar

Hiroaki K. 2016. Physics of soft impact and cratering. Berlin Springer Verlag. V. 910. Search in Google Scholar

Holsapple KA, Schmidt RM. 1987. Point source solutions and coupling parameters in cratering mechanics. J Geophys Res Solid Earth. 92(B7):6350–6357. 10.1029/JB092iB07p06350Search in Google Scholar

Maxwell DE. 1976. Simple Z model for cratering, ejection, and the overturned flap. Impact Explosion Cratering. 1(1):1003–1008. Search in Google Scholar

Melosh HJ, Ivanov BA. 1999. Impact crater collapse. Science. 6314(354):878–882. Search in Google Scholar

Nishida M, Okumura M, Tanaka K. 2010. Effects of density ratio and diameter ratio on critical incident angles of projectiles impacting granular media. Granular Matter. 12(4):337–344. 10.1007/s10035-010-0186-7Search in Google Scholar

Nishida M, Nagamatsu J, Tanaka K. 2011. Discrete element method analysis of ejection and penetration of projectile impacting granular media. J Solid Mechanics Materials Eng. 5(4):164–178. 10.1299/jmmp.5.164Search in Google Scholar

Pica CM, Lara AH, Lee AT, et al. 2004. Dynamics of drag and force distributions for projectile impact in a granular medium. Phys Rev Lett. 92(19):194301–194305. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.194301Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Ruizsuarez CJ. 2013. Penetration of projectiles into granular targets. Reports on Progress in Physics. 76(6):066601–06662010.1088/0034-4885/76/6/066601Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Soliman AS, Reid SR, Johnson W. 1976. The effect of spherical projectile speed in ricochet off water and sand. Int J Mech Sci. 18(6):279–284. 10.1016/0020-7403(76)90029-1Search in Google Scholar

Takizawa S, Katsuragi H. 2023. Scaling laws for the oblique impact cratering on an inclined granular surface. Icarus. 335(1):113409–113421. 10.1016/j.icarus.2019.113409Search in Google Scholar

Thielicke W, Stamhuis EJ. 2014. PIV lab-towards user-friendly, affordable and accurate digital particle image velocimetry in MATLAB. J Open Res Softw. 2(1):115730–115745. 10.5334/jors.blSearch in Google Scholar

Uehara JS, Ambroso MA, Ojha RP, Durian DJ. 2003. Low-speed impact craters in loose granular media. Phys Rev Lett. 90(19):194301. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.194301Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Umbanhowar P, Goldman DI. 2010. Granular impact and the critical packing state. Phys Rev E. 82(1):010301–010305. 10.1103/PhysRevE.82.010301Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Van D M. 2017. Impact on granular beds. Annual Reviews. 49(1):463–484. 10.1146/annurev-fluid-010816-060213Search in Google Scholar

Walsh AM, Holloway KE, Habdas P, et al. 2003. Morphology and scaling of impact craters in granular media-art. Phys Rev Lett. 91(10):104301–10430410.1103/PhysRevLett.91.104301Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Wang DM, Ye XY, Zheng XJ. 2012. The scaling and dynamics of a projectile obliquely impacting a granular medium. Europ Phys J E Soft Matter. 35(1):1–12. 10.1140/epje/i2012-12007-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Wang DM, Zheng XJ. 2013. Experimental study of morphology scaling of a projectile obliquely impacting into loose granular media. Granular Matter. 15(6):725–734. 10.1007/s10035-013-0446-4Search in Google Scholar

Yang MY, Li R, Xiu YN, et al. 2023. The propagation of Quasi-static region during granular impact. Particuology. 83(12):1–7. 10.1016/j.partic.2023.02.003Search in Google Scholar

Ye X, Wang D, Zheng X. 2012. Influence of particle rotation on the oblique penetration in granular media. Phys Rev E. 86:061304.10.1103/PhysRevE.86.061304Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Ye XY, Wang DM, Zheng XJ. 2015. Effects of density ratio and diameter ratio on penetration of rotation projectile obliquely impacting a granular medium. Eng Comput. 32(4):1025–1040. 10.1108/EC-04-2014-0091Search in Google Scholar

Ye XY, Wang DM, Zheng XJ. 2016. Criticality of post-impact motions of a projectile obliquely impacting a granular medium. Powder Technol. 301(7):1044–1053. 10.1016/j.powtec.2016.07.043Search in Google Scholar

Zeng Q, Li R, Li YM. 2022. Recognition of a quasi-static region in a granular bed impacted with a sphere. Powder Technol. 407(10):117612–117624. 10.1016/j.powtec.2022.117612Search in Google Scholar

Zheng XJ, Wang ZT, Qiu ZG. 2004. Impact craters in loose granular media. Europ Phys J E. 13:321–324. 10.1140/epje/i2004-10002-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- A generalized super-twisting algorithm-based adaptive fixed-time controller for spacecraft pose tracking

- Retrograde infall of the intergalactic gas onto S-galaxy and activity of galactic nuclei

- Application of SDN-IP hybrid network multicast architecture in Commercial Aerospace Data Center

- Observations of comet C/1652 Y1 recorded in Korean histories

- Computing N-dimensional polytrope via power series

- Stability of granular media impacts morphological characteristics under different impact conditions

- Intelligent collision avoidance strategy for all-electric propulsion GEO satellite orbit transfer control

- Asteroids discovered in the Baldone Observatory between 2017 and 2022: The orbits of asteroid 428694 Saule and 330836 Orius

- Light curve modeling of the eclipsing binary systems V0876 Lyr, V3660 Oph, and V0988 Mon

- Modified Jeans instability and Friedmann equation from generalized Maxwellian distribution

- Special Issue: New Progress in Astrodynamics Applications - Part II

- Multidimensional visualization analysis based on large-scale GNSS data

- Parallel observations process of Tianwen-1 orbit determination

- A novel autonomous navigation constellation in the Earth–Moon system

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- A generalized super-twisting algorithm-based adaptive fixed-time controller for spacecraft pose tracking

- Retrograde infall of the intergalactic gas onto S-galaxy and activity of galactic nuclei

- Application of SDN-IP hybrid network multicast architecture in Commercial Aerospace Data Center

- Observations of comet C/1652 Y1 recorded in Korean histories

- Computing N-dimensional polytrope via power series

- Stability of granular media impacts morphological characteristics under different impact conditions

- Intelligent collision avoidance strategy for all-electric propulsion GEO satellite orbit transfer control

- Asteroids discovered in the Baldone Observatory between 2017 and 2022: The orbits of asteroid 428694 Saule and 330836 Orius

- Light curve modeling of the eclipsing binary systems V0876 Lyr, V3660 Oph, and V0988 Mon

- Modified Jeans instability and Friedmann equation from generalized Maxwellian distribution

- Special Issue: New Progress in Astrodynamics Applications - Part II

- Multidimensional visualization analysis based on large-scale GNSS data

- Parallel observations process of Tianwen-1 orbit determination

- A novel autonomous navigation constellation in the Earth–Moon system