Abstract

Background and purpose

Depression is a frequent co-morbid diagnosis in chronic pain, and has been shown to predict poor outcome. Several reviews have described the difficulty in accurate and appropriate measurement of depression in pain patients, and have proposed a distinction between pain-related distress and clinical depression. Aims of the current study were to compare (a) the overlap and differential categorisation of pain patients as depressed, and (b) the relationship to disability between the Structured Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-Depression module) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-D).

Methods

Seventy-eight chronic back pain patients were administered the SCID-D, the HADS-D and the Pain Disability Index (PDI).

Results

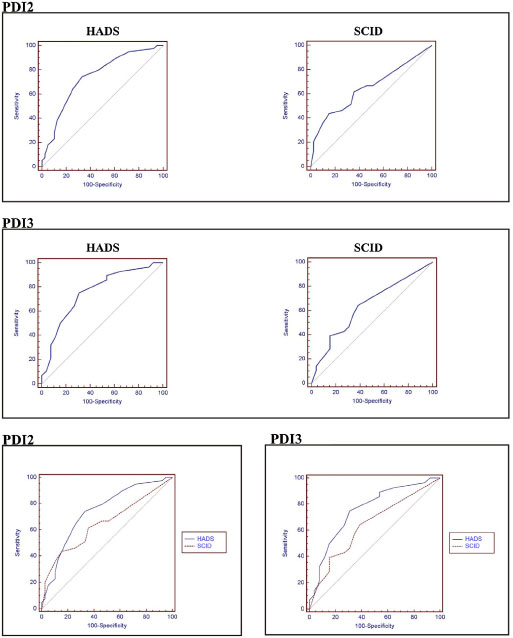

Significantly more patients were categorised with possible and probable depression by the HADS than the SCID-D. Results from Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis suggested that the HADS-D provided better discriminatory ability to detect disability, demonstrating a better balance between sensitivity and specificity compared to the SCID-D, although a direct comparison between the two measurements showed no difference.

Conclusions

The HADS-D is a reasonably accurate indicator of pain-related distress in chronic pain patients, and captures the link between disability and mood.

Implications

It is likely that the SCID-D is better suited to identifying sub-groups with more pronounced psychiatric disturbance.

Perspective

Several reviews have proposed a distinction between pain-related distress and clinical depression. This study compared the overlap and differential categorisation of pain patients as depressed and the relationship to disability between the Structured Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-D; Depression module) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-D).

© 2016 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain. Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1 Introduction

Chronic back pain and depression are two of the most common health problems that health professionals encounter and depression is a particularly frequent co-morbid diagnosis in chronic pain [17, 21, 31]. Research on the relationship between pain and depression addresses conceptual issues as well as issues of measurement [1, 13]. However, the nature of the relationship between concepts, models and measurement of depression in people with pain is still unclear [3, 19, 24]. Studies have demonstrated that the kind of depression experienced by people with chronic pain differs qualitatively from people who suffer from clinical depression. Low mood in chronic pain patients has been found to be closely related to disability, and to incorporate features that are different from those typical of psychiatric groups with depression [22, 29]. Researchers have therefore suggested conceptualising depression in pain as ‘pain-related distress’ in order to distinguish between traditionally conceptualised clinical depression and the complex features of suffering, anger, worry and pre-occupation with health that seem to be experienced by patients with chronic pain [15, 16, 23, 24, 36, 37]

The ambiguity surrounding measurement of depression in people with pain is reflected even in basic health information such as prevalence: the wide variability in estimated rates of depression in chronic pain samples, ranging from 16.4% to 73.3% [7, 16, 18], may be accounted for by methodological problems. Specifically, the choice of measurement is important, as many measurements are limited by criterion contamination [23, 34]: i.e. they include somatic items, such as loss of appetite, weight change and sleep disturbance, which may reflect levels of pain and disability rather than depression [8, 26]. This study focuses on two commonly used measures: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis 1 disorders (SCID [6, 38]) - Depression module, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS [39]). Although assumed to be a ‘gold standard’, little research has been done to investigate the validity and appropriateness of the SCID interview for use with patients who have chronic pain. Some investigators argue that the use of the SCID interview is as confounded by criterion contamination as self-report measures [8, 24]. In contrast, the HADS was developed specifically for use with patients from a range of medical conditions and includes less somatic items, and therefore should be relatively free of criterion contamination. The two measurements differ in their objectives: while the SCID was developed to diagnose people with depression, conceptualised as a psychiatric disorder, the HADS aims to identify low mood which may or may not indicate a stand-alone psychiatric diagnosis. They may therefore have different utilities for populations with chronic pain.

If pain-related distress is characterised by a cyclical relationship with disability, as proposed by some models [24, 35], while clinical depression is a mood disorder that is less entrenched in pain experiences, it is important to establish which measures best capture each of these distinct constructs. This study aims to investigate the overlap between the measurements in indication of depression, and how each measure relates to disability in general (correlation analysis), and in their sensitivity and specificity discrimination of disability levels.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Participants

Seventy eight adults with chronic back pain participated in this cross-sectional study (23 male, 55 female) and were consecutively recruited from participating general practices and pain clinics from July 2005 until June 2006. Primary complaints were pain localized in the lower back (79.5%), cervical back pain (18%), and thoracic back pain (2.5%).

The main inclusion criteria were the ability to read and write English fluently. All patients had persistent pain for more than 3 months. Pain patients were only included if they rated their current level of pain, and the level of pain that they had experienced in the past few months as 3 or above on an 11-point Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), where 0 was ‘no pain’ and 10 was ‘extremely painful’ [12]. General practitioners and clinicians excluded patients with signs and symptoms of more severe pathology [33] or progressive disorders such as cancer.

2.2 Procedure

Pain patients attending general practices and pain clinics in London, United Kingdom, who consented to take part in the study were interviewed face to face by a qualified consultant clinical psychologist with over 4 years experience of treating pain populations. Participants were administered consecutively the SCID interview, a semi-structured interview that included affective, cognitive and neurovegetative questions designed to diagnose affective disorders according to DSM-IV criteria, followed by the questionnaires.

Of those who left their details with the researcher, only 5% (n = 5) of potential participants did not take part due to difficulties in attending the appointment (because of work deadlines; unexpected family issues; personal demands or illness), and 2.2% (n = 3) were not able to be contacted. Altogether of the 78 patients who came to the appointment with the researcher, there were no refusals to participate in the study. All participants provided informed consent. The University Ethics Committee and LREC (London Research Ethics Committee) approved this study.

2.3 Measures

In addition to obtaining basic demographic and clinically relevant descriptive data (age, gender, education, main clinical diagnosis, duration of pain and pain intensity), the following measures were obtained.

2.3.1 The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS [39])

The HADS is a self-report measure that consists of 14 items grouped into two subscales, seven measuring anxiety and seven depression. Ratings are made on four point scales (0-3) representing the degree of distress during the previous week. Scores of 7 or less indicates non-cases, 8-10 possible cases, and 11+ probable cases [39]. Both subscales have shown good reliability and validity when used as a psychological screening tool in hospital settings and are sensitive to changes in patients’ emotional state in longitudinal assessments [11]. Severe psychopathological symptoms (guilt, suicidal thoughts) are not included, improving its acceptability and making the scale more sensitive to mild forms of psychiatric disorders and avoiding the “floor effect” which is frequently observed when psychiatric questionnaires are used with general medical patients [11]. For this study only the depression subscale was included in the analyses (HADS-D).

2.3.2 Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis 1 disorders (SCID [6]) - depression module

The section of the SCID evaluating current major depressive disorder was used to detect the presence of depressive disorder (SCID-1 NP [6]). Investigations of the test-retest reliability of the SCID have shown that for most of the major categories, kappa’s for current and lifetime diagnoses in the patient samples were above .60 [38]. The SCID depression module provides 9 items with an individual score, and a final dichotomised classification that identifies individuals with present or absent depression (SCID-D).

2.3.3 Pain Disability Index (PDI [26])

The PDI is a brief 7-item self-report measure of the extent of pain interfering with different domains of an individual’s life [26, 33]. The seven domains are family, recreation, social activities, occupation, sexual behaviour, self-care and life support activities. Each item is rated on an 11-point Likert-type scale (0 = no disability; 10 = total disability) and the PDI total score can range from 0 to 70. The PDI has established reliability and validity [2, 9, 14, 32, 33]. Factor analytic studies have reported one and two factor solutions [2, 32]. The single factor scoring method was used in this study, i.e. sum of all seven domains.

2.4 Statistical analyses

The following statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS for Windows, version 16.0) and the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) software programme (MedCalc Version 9.5). Missing values in the data set were replaced by means in SPSS. The detection of disability by the HADS-D and the SCID-D was assessed by reference of two standard criteria: sensitivity (the probability of a chronic back pain patient testing positively for depression when the patient scores high on disability/dysfunction) and specificity (the probability of a chronic back pain patient testing negatively for depression when the patient scores low on disability/dysfunction), using the formulae suggested by Hennekes and Buring [10]. The relationship between the two depression measures and disability was investigated by Pearson and Spearman (as a non-parametric alternative) correlation coefficients. Correlations were interpreted according to the definitions provided byTabachnick& Fidell [32] (≤.30 = weak correlation; ≤.60 = moderate correlation; ≤.80 = strong correlation). A P value of 0.05 was set as the critical level at or below which the results would be considered statistically significant.

Coding of the questionnaires was as follows: The HADS-D was coded both for the 8 cut-off point (HADS-D8) and the 11 cut-off point (HADS-D11) to diagnose possible and probable depression. In the absence of published cut-off scores, the PDI was coded in two ways: (a) PDI2 - a median split was performed to divide the patients into high and low disability groups; and (b) PDI3 - a tercile split was performed; patients that scored below the 33rd percentile and above the 66th were classified as having low and high disability, respectively. The SCID-D final dichotomous classification (depression absent vs. present), and the total amount of symptoms scored present (range 0-9) were used [6].

We also performed several Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analyses to evaluate sensitivity and specificity in detecting disability by the HADS-D and the SCID-D. ROC curves express the relationship between true positives (sensitivity) and false negatives (specificity) over the full range of possible cut-off points providing an assessment of the accuracy of the measurements in discriminative positive from negative cases [20, 25]. The diagnostic power of a test is estimated by the area under the ROC curve which ranges from 0.5 to 1 (from no discriminatory power to total discriminatory power [5]). The HADS depression subscale and the SCID depression module were analysed separately to compare their discrimination accuracy for disability, and together to allow a direct comparison between the measures. The optimal cut-off point criteria chosen for the HADS-D and SCID-D was selected according to the maximum specificity, without allowing it to exceed sensitivity criteria as it places the same priority on avoiding false positives as on avoiding false negative classifications.

3 Results

3.1 Demographic variables

Table 1 presents basic demographic information.

A mean score of 8.08 (SD = 4.2) was found for the Depression subscale of the HADS, a mean score of 33.82 (SD =15.4) for the PDI, and a mean score of 3.14 (SD = 3.2) for the total amount of symptoms scored present on the SCID depression module (range 0-9).

Demographic information.

| Variables | N = 78 |

|---|---|

| Gender N (male/female) | 23/55 |

| Mean age (SD) | 45.26 (13.39) |

| Educational status (none/degree) | 20/16 |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 27 |

| Married/living with partner | 40 |

| Divorced/separated | 8 |

| Other | 3 |

| Employment status | |

| Full-time | 25 |

| Part-time | 4 |

| Unemployed | 33 |

| Other | 16 |

| Present pain intensity | 5.42 (2.09) |

| Average pain intensity over past week | 5.94 (1.97) |

| Worst pain intensity in past 6 months | 8.86 (1.42) |

| Pain interference | 6.76 (2.21) |

| Pain duration (months) | 78.54 (93.11) |

| HADS - Anxiety score | 9.71 (3.99) |

| HADS - Depression score | 8.08 (4.20) |

| PDI - Disability score | 33.82 (15.42) |

| SCID - Depression score | 3.14 (3.23) |

-

Note SCID = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Depression module;

-

HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, PDI = Pain Disability Index.

The HADS-D and the SCID-D indication of depression in chronic back pain patients(N = 78).

| SCID-D | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absent | Present | |||

| N | % | N | % | |

| HADS-D 8 | ||||

| Absent depression | 33 | 42.3 | 3 | 3.8 |

| Present depression | 17 | 21.8 | 25 | 32.1 |

| HADS-D11 | ||||

| Absent depression | 33 | 42.3 | 3 | 3.8 |

| Indication for depression | 12 | 15.4 | 10 | 12.8 |

| Present depression | 5 | 6.4 | 15 | 19.2 |

-

Note SCID-D = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Depression module; HADS- D = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, only the Depression scale was used for analyses.

3.2 Levels of agreement on detecting depression between the HADS-D and the SCID-D

Table 2 shows the levels of agreement and disagreement for both measures in defining patients as depressed. When the HADS- D8 cut-off was used, there was an agreement between the measures for exclusion of depression on 42% of the patients and for inclusion on 32% of the patients. For 21% of the patients the SCID-D provided an indication for exclusion of depression whereas the HADS-D provided an indication for inclusion. Only in 4% of the patients did the SCID-D provide an indication for depression whereas the HADS-D provided an indication for exclusion. When using the HADS-D11, the agreement for inclusion between the measures decreased to 19%. Furthermore for 15% of the patients the SCID-D provided an indication for exclusion of depression whereas the HADS-D provided an indication for possible inclusion. These differences were statistically significant: in sum, the HADS-D defined overall more patients as depressed compared to the SCID-D.

3.3 Relationship between the measures of depression and pain disability

A moderately strong Pearson’s correlation was found between the HADS-D and the PDI total score (r =.551, p≤ .0001) and a weak Spearman’s correlation was found between the SCID-D and the PDI total score (r =.227, p≤.05).

ROC curves for all measures used in the analyses. The further the curve extends into the upper left quadrant of the plots, the higher the sensitivity/ specificity of the measure. Note. SCID = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Depression module; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, only the Depression scale was used for analyses; PDI = Pain Disability Index;PDI2 = median split; PDI3 = upper and lower terciles.

3.4 Sensitivity/specificity of detecting disability by the HADS-D and the SCID-D

To investigate whether the HADS-D and the SCID-D can detect reduced function in chronic pain patients, the sensitivity (probability of a chronic back patient testing positively for depression when the patient is high on disability/dysfunction) and specificity (probability of a chronic back pain patient testing negatively for depression when the patient is low on disability/dysfunction) of the two measures were studied. The performance of the HADS- D8, HADS-D11 and the SCID-D for sensitivity and specificity are shown in Table 3, using PDI2 and PDI3 disability as the classification variables. For the HADS-D8, HADS-D11 and SCID-D (dichotomous classification) the sensitivity and specificity were calculated using the formulae suggested by Hennekes and Buring [10]. When using the HADS-D and the SCID-D scores as a continuous variable, several Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analyses were performed to evaluate their diagnostic prediction of dysfunction. Using the PDI2 as the criteria for case definition and the HADS-D scores, the area under the curve of 0.74 with a standard error of 0.05 (95% CI: 0.63-0.83; p = 0.0001), and for the SCID-D an area under the curve of 0.65 with a standard error of 0.06 (95% CI: 0.53-0.75; p = 0.017). The optimal cut-off points were >7 for the HADS-D and >5 for the SCID. Using the PDI3 as the criteria for case definition and the HADS-D scores the area under the curve was 0.76 with a standard error of 0.06 (95% CI: 0.62-0.86; p = 0.0001) and for the SCID-D there was an area under the curve of 0.64 with a standard error of 0.07 (95% CI: 0.49-0.76; p = 0.063). The optimal cut-off points were > 7 for the HADS-D and ? 1 for the SCID-D. The results from the ROC analyses showed that the HADS-D provided the better discriminatory ability overall, demonstrating a better balance between sensitivity and specificity than the SCID-D. When a more demanding criterion for disability was used (through the PDI3) the results were similar. When the HADS-D and the SCID-D were compared simultaneously using the PDI2, the difference between the areas was 0.093 with a standard error of 0.06 (95% CI: -0.02 to 0.21; p = 0.105). When using the PDI3, the difference between the areas was 0.117 with a standard error of 0.06 (95% CI: -0.005 to 0.24; p = 0.06) (see Table 3 and Fig. 1). In sum, both analyses show no statistically significant differences between the areas, but indicating that there was a borderline effect for significance regarding the prediction quality between the two measures for the PDI3 classification.

Results of the ROC analyses for both PDI2 and PDI3, discriminating between HADS-D and SCID-D.

| Calculations | ROC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HADS-D8 | HADS-D11 | SCID-D | HADS-D | SCID-D | |

| PDI2 | |||||

| Sensitivity | 0.74 | 0.60 | 0.46 | 0.74 | 0.44 |

| Specificity | 0.66 | 0.84 | 0.74 | 0.67 | 0.85 |

| AUC | 0.74 | 0.65 | |||

| P | 0.0001 | 0.017 | |||

| > | 7 | 5 | |||

| PDI3 | |||||

| Sensitivity | 0.75 | 0.61 | 0.43 | 0.75 | 0.64 |

| Specificity | 0.69 | 0.86 | 0.73 | 0.69 | 0.62 |

| AUC | 0.76 | 0.64 | |||

| P | 0.0001 | 0.063 | |||

| > | 7 | 0 | |||

-

Note SCID-D = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-1V, Depression module; HADS- D = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, only the Depression scale was used for analyses; PDI = Pain Disability Index; PDI2 = median split; PDI3 = upper and lower terciles.

4 Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first study to explore how closely the HADS-D and the SCID-D relate to disability in chronic pain patients. In the absence of an objective gold standard measure to identify distress and depression in chronic pain it is important to examine how measurements perform in relation to theoretical models. This study was informed by the hypothesis that a large proportion of pain patients experience low mood, but that this affect does not imply clinical depression. Pain-related distress differs qualitatively from clinical depression in that it is closely related to pain, suffering and disability. In contrast, clinical depression is characterised by hopelessness, helplessness and negative cognitions about the self, the world and future [22]. Currently it is not known how measurements of depression perform in reference to the two concepts: this study is a first attempt to explore this, however, it should be noted that it was not aimed to directly test different models of depression against each other. In order to test hypotheses linked to different models of depression future prospective studies with reliable and valid measures of possible predictors are needed. The findings from this study suggest that the HADS-D is a better measure of pain-related distress in pain populations, in that it is more closely related to disability scores, and better able to detect disability than the SCID-D. 1t is likely that many more patients with chronic pain experience pain-related distress than clinical depression: the findings reflect this in terms of the number of patients categorised as possible and probable depression by the HADS-D, which were considerably higher than those suggested by the SCID-D. This notion is in line with actual changes in the classification of pain disorders in the DSM-5 classification of disorders, which regards chronic pain no longer as a psychiatric disorder, but highlights the importance of the interaction between pain and pain-related distress and secondary mood changes as consequence of having a chronic pain condition [4].

While the study provides evidence that the two methods differ in their identification of depression, the explanation for this difference cannot be extrapolated from the data: The methodologies may measure different constructs, as proposed by the models described above, but equally, one measure maybe superior in detecting ‘true’ depression. A divergence between the SCID-D and the HADS-D was to be expected as the inclusion criteria for a current episode of Major Depression in the SCID-D are more conservative compared to the HADS-D, which was specifically designed for use with patients with physical or chronic illness and focuses predominantly on the cognitive state of anhedonia [39]. Our findings highlight the fact that if exclusive reliance were placed only on one or two assessment approaches, significant “false-positives” and “false-negatives” would accrue to the assessment process, thus highlighting the value of multi-method assessment strategies in depressed chronic back pain patients.

Future research should investigate whether pain-distress and clinical depression are distinct constructs, or whether clinical depression is merely a more extreme manifestation of mood along a continuum of a single construct. Interpreting the current findings should be carried out with caution, due to the small sample size, and replication of the findings in larger samples is necessary to further test the utility of the two measures in detecting distress and depression. Further, the results of the current study are limited to patients with chronic back pain. Our tentative interpretation of the results is that the HADS-D is probably an adequate measure to establish which pain patients require interventions on psychosocial factors in addition to pain-related factors, but may result in extensive false- positives if used to diagnose clinical depression. Conversely, the SCID-D’s utility is in the identification of affective disorder, but may fail to identify pain patients who have mood-related psychological problems that interact with their disability.

With regard to the limitations of the study, the issue of criterion contamination continues to be an important issue in the measurement of depression in pain populations. Recent research has indicated that psychometric properties such as responsiveness alter significantly when somatic items are removed from commonly used instruments [24]: the inclusion of such items in trials’ outcomes that aim to affect mood but not pain may distort findings. Despite the inclusion of more somatic items in the SCID-D than the HADS-D, the interview-based measure did not result in inflated number of patients diagnosed with depression. This may have been because the interviewer had extensive experience in research with pain patients and was familiar with the literature surrounding criterion contamination. Although we attempted to control for experimenter effects by blinding the coding of the HADS questionnaires, it is possible that this researcher was less likely to endorse somatic responses in the SCID-D as mood related. This highlights the need for replication with naive clinical interviewers, and for comparison between clinical interviewers experienced with pain populations and with those whose experience is in psychiatric non-pain groups. Most importantly, future studies should include additional double ratings from a second rater to examine the rate of agreement for the SCID-D. This also serves as a reminder that the SCID-D, which is considered a gold standard for the diagnosis of depression, is more vulnerable to experimenter bias than self-report measures, which are often considered inferior. However, semi-structured interviews account for the need to allow patients to describe in their own language the processes they experience and enable us to understand the individual responses in relation to established theoretical concepts and models of depression, and for depression in the presence of chronic pain [3]. Finally, due to the cross-sectional design of the current study, we would like to highlight that the present results might represent a first step towards a more comprehensive understanding of co-morbid depression in the context of chronic pain and longitudinal studies are warranted. We believe that a promising new area of research is to employ qualitative analyses to the responses of depressed chronic back patients to the SCID interview in contrast to clinically depressed patients in order to enhance our understanding of content specificity [30]. Apart from one qualitative study [12], there are at present no studies available which investigated with qualitative methodology the area of com-morbid depression in the context of chronic pain, which currently represents a neglected area of study. Accumulating evidence that the quality and content of depression in the context of persistent back pain is different compared to clinical depression [27, 28], may advocate the development of new treatment modalities for this specific group of back pain patients [12].

Highlights

Accurate and appropriate measurement of depression in pain patients is difficult.

Depression as frequent co-morbid diagnosis in chronic pain predicts poor outcome.

HADS-D provides better discriminatory ability to detect disability than SCID-D.

HADS-D captures the link between disability and mood.

-

Conflict of interest:The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Disclosures

This research was supported by a grant from Back Care, The Charity for Healthier Backs and the Central Research Fund of the University of London. The first author was supported by a postgraduate scholarship by the Friedrich-Ebert Foundation, Germany.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Charles Pither, Dr Johannes van der Merwe and Dr. Dylan Morrissey for their support throughout the process of this study and Dr Rob Froud for his advice on statistical issues. We would like to thank all patients for participating in this study.

References

[1] Banks SM, Kerns RD. Explaining high rates of depression in chronic pain: a diathesis-stress framework. Psychol Bull 1996;119:95-110.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] ChibnallJT, Tait RC. The Pain Disability Index: factor structure and normative data. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1994;75:1082-6.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Clyde Z, Williams AC. Depression and mood. In: Linton SJ, editor. New avenues for the prevention of chronic musculoskeletal pain and disability. Pain research and clinical management. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2002. p. 105-21.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th edition). American Psychiatric Association; 2013.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Erdreich L, Lee E. Use of relative operating characteristics analysis in epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 1981;114:649-62.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, WilliamsJBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorder, Research Version, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P). New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Fishbain DA, Goldberg M, Meagher BR, Steele R, Rosomoff H. Male and female chronic pain patients categorized by DSM-III psychiatric diagnostic criteria. Pain 1986;26:181-97.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Gallagher RM, Moore P, Chernoff I. The reliability of depression diagnosis in chronic low back pain. A pilot study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1995;17:399-413.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Gronblad M, Hupli M, Wennerstrand P, Jarvinen E, Lukinmaa A, Kouri JP, Karaharju EO. Intercorrelation and test-retest reliability oft he Pain Disability Index (PDI) and the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire (ODQ) and their correlation with pain intensity in low back pain patients. Clin J Pain 1993;9:189-95.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Epidemiology in medicine. Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 1987.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Herrmann C. International experiences with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale - a review of validation data and clinical results. J Psychosom Res 1997;42:17-41.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Hopton A, Eldres J, MacPherson H. Patients’ experiences of acupuncture and counselling for depression and comorbid pain: a qualitative study nested within a randomized controlled trial. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005144.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Huijnen IPJ, Rusu AC, Scholich S, Meloto C, Diatchenko L. Subgrouping of low back pain patients for targeting treatments: evidence from genetic, psychological and activity-related behavioural approaches. Clin J Pain 2015;31: 123-32.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Jensen MP, Karoly P, Braver S. The measurement of clinical pain intensity: a comparison of six methods. Pain 1986;27:117-26.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Jerome A, Gross RT. Pain disability index: construct and discriminant validity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1991;72:920-2.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Kessler M, Kronstorfer R, Traue HC. Depressive symptoms and disability inacute and chronic back pain patients. Int J Behav Med 1996;3:91-103.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Krishnan KR, France RD, Pelton S, McCann S. Chronic pain and depression. I. Classification of depression in chronic low back pain patients. Pain 1985;22:279-87.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Linton SJ, Bergbom S. Understanding the link between depression and pain. Scand J Pain 2011;2:47-54.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Magni G, Marchetti M, Moreschi C, Merskey H, Rigatti-Luchini S. Chronic musculoskeletal pain and depressive symptoms in the National Health and Nutrition Examination. I. Epidemiologic follow-up study. Pain 1993;53:163-8.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Metz CE. Basic principles of ROC analysis. Semin Nucl Med 1978;8:283-98.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Ohayon MM, Schatzberg AF. Using chronic pain to predict depressive morbidity in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:39-47.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Pincus T, Morley S. Cognitive biases in chronic pain. Psychol Bull 2001;127:599-617.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Pincus T, Pearce S, McClelland A, Isenberg D. Endorsement and memory bias of self-referential pain stimuli in depressed pain patients. Br J Clin Psychol 1995;34:267-77.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Pincus T, Rusu A, Santos R. Responsiveness and construct validity of the Depression: Anxiety and Positive Outlook Scale (DAPOS). Clin J Pain 2008;24:431-7.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Pincus T, Williams A. Models and measurements of depression inchronic pain. J Psychosom Res 1999;47:211-9.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Pollard CA. Preliminary validity study of the pain disability index. Percept Mot Skills 1984;59:974.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Romano JM, Turner JA. Chronic pain and depression: does the evidence support a relationship? Psychol Bull 1985;97:18-34.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Turk DC, Boersma K, Rusu AC. Reviewing the concept of subgroups in subacute and chronic pain and the potential of customizing treatments. In: Hasenbring MI, Rusu AC, Turk DC, editors. From acute to chronic pain: risk factors, mechanisms and clinical implications. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012. p. 485-512.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Rusu AC, Pincus T, Morley S. Depressed pain patients differ from other depressed groups: examination of cognitive content in a sentence completion task. Pain 2012;153:1898-904.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Rusu AC, Pincus T (in preparation) Qualitative differences in patients with chronic pain and depression; 2016.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Sullivan MJ, Edgley K, Mikail S, Dehoux E, Fisher R. Psychological correlates of health care utilization in chronic illness. Canad J Rehabilitation 1992;6: 13-21.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 2001.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Tait RC, Chibnall JT, Krause S. The Pain Disability Index: psychometric properties. Pain 1990;40:171-82.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Tait RC, Pollard CA, Margolis RB, Duckro PN, Krause SJ. The Pain Disability Index: psychometric and validity data. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1987;68:438-41.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Turk DC, Okifuji A. Psychological factors in chronic pain: evolution and revolution. J Consult Clin Psychol 2002;70:678-90.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Waddell G. Back pain revolution. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1998.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Williams AC, Richardson PH. What does the BDI measure in chronic pain? Pain 1993;55:259-66.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB, Spitzer RL, Davies M, Borus J, Howes MJ, Kane J, Pope HG, Rounsaville B, Wittchen HU. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). II. Multisite test-retest reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992;49:630-6.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361-70.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2016 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Scandinavian Journal of Pain

- Editorial comment

- Depressive symptoms associated with poor outcome after lumbar spine surgery: Pain and depression impact on each other and aggravate the burden of the sufferer

- Clinical pain research

- Depressive symptoms are associated with poor outcome for lumbar spine surgery

- Editorial comment

- Chronic compartment syndrome is an under-recognized cause of leg-pain

- Observational study

- Prevalence of chronic compartment syndrome of the legs: Implications for clinical diagnostic criteria and therapy

- Editorial comment

- Genetic susceptibility to postherniotomy pain. The influence of polymorphisms in the Mu opioid receptor, TNF-α, GRIK3, GCH1, BDNF and CACNA2D2 genes

- Clinical pain research

- Genetic susceptibility to postherniotomy pain. The influence of polymorphisms in the Mu opioid receptor, TNF-α, GRIK3, GCH1, BDNF and CACNA2D2 genes

- Editorial comment

- Important development: Extended Acute Pain Service for patients at high risk of chronic pain after surgery

- Observational study

- New approach for treatment of prolonged postoperative pain: APS Out-Patient Clinic

- Editorial comment

- Working memory, optimism and pain: An elusive link

- Original experimental

- The effects of experimental pain and induced optimism on working memory task performance

- Editorial comment

- A surgical treatment for chronic neck pain after whiplash injury?

- Clinical pain research

- A small group Whiplash-Associated-Disorders (WAD) patients with central neck pain and movement induced stabbing pain, the painful segment determined by mechanical provocation: Fusion surgery was superior to multimodal rehabilitation in a randomized trial

- Editorial comment

- Social anxiety and pain-related fear impact each other and aggravate the burden of chronic pain patients: More individually tailored rehabilitation need

- Clinical pain research

- Characteristics and consequences of the co-occurrence between social anxiety and pain-related fear in chronic pain patients receiving multimodal pain rehabilitation treatment

- Editorial comment

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation, paravertebral muscles training, and postural control in chronic low back pain

- Original experimental

- Influence of paravertebral muscles training on brain plasticity and postural control in chronic low back pain

- Editorial comment

- Is there a place for pulsed radiofrequency in the treatment of chronic pain?

- Clinical pain research

- Pulsed radiofrequency in clinical practice – A retrospective analysis of 238 patients with chronic non-cancer pain treated at an academic tertiary pain centre

- Editorial comment

- More postoperative pain reported by women than by men – Again

- Observational study

- Females report higher postoperative pain scores than males after ankle surgery

- Editorial comment

- The relationship between pain and perceived stress in a population-based sample of adolescents – Is the relationship gender specific?

- Observational study

- Pain is prevalent among adolescents and equally related to stress across genders

- Editorial comment

- The Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) – Revisited and rejuvenated?

- Clinical pain research

- Confirmatory factor analysis of 2 versions of the Brief Pain Inventory in an ambulatory population indicates that sleep interference should be interpreted separately

- Editorial comment

- Pain research reported at the 40th scientific meeting of the Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain in Reykjavik, Iceland May 26–27, 2016

- Abstracts

- Pain management strategies for effective coping with Sickle Cell Disease: The perspective of patients in Ghana

- Abstracts

- PEARL – Pain in early life. A new network for research and education

- Abstracts

- Searching for protein biomarkers in pain medicine – Mindless dredging or rational fishing?

- Abstracts

- Effectiveness of smart tablets as a distraction during needle insertion amongst children with port catheter: Pre-research with pre-post test design

- Abstracts

- Postoperative oxycodone in breast cancer surgery: What factors associate with analgesic plasma concentrations?

- Abstracts

- Sport participation and physical activity level in relation to musculoskeletal pain in a population-based sample of adolescents: The Young-HUNT Study

- Abstracts

- “Tears are also included” - women’s experience of treatment for painful endometriosis at a pain clinic

- Abstracts

- Predictors of long-term opioid use among chronic nonmalignant pain patients: A register-based national open cohort study

- Abstracts

- Coupled cell networks of astrocytes and chondrocytes are target cells of inflammation

- Abstracts

- Changes in opioid prescribing behaviour in Denmark, Sweden and Norway - 2006-2014

- Abstracts

- Opioid usage in Denmark, Norway and Sweden - 2006-2014 and regulatory factors in the society that might influence it

- Abstracts

- ADRB2, pain and opioids in mice and man

- Abstracts

- Retrospective analysis of pediatric patients with CRPS

- Abstracts

- Activation of epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFRs) following disc herniation induces hyperexcitability in the pain pathways

- Abstracts

- Pain rehabilitation with language interpreter, a multicenter development project

- Abstracts

- Trait-anxiety and pain intensity predict symptoms related to dysfunctional breathing (DB) in patients with chronic pain

- Abstracts

- Emla®-cream as pain relief during pneumococcal vaccination

- Abstracts

- Use of Complimentary/Alternative therapy for chronic pain

- Abstracts

- Effect of conditioned pain modulation on long-term potentiation-like pain amplification in humans

- Abstracts

- Biomarkers for neuropathic pain – Is the old alpha-1-antitrypsin any good?

- Abstracts

- Acute bilateral experimental neck pain: Reorganise axioscapular and trunk muscle activity during slow resisted arm movements

- Abstracts

- Mast cell proteases protect against histaminergic itch and attenuate tissue injury pain responses

- Abstracts

- The impact of opioid treatment on regional gastrointestinal transit

- Abstracts

- Genetic variation in P2RX7 and pain

- Abstracts

- Reversal of thermal and mechanical allodynia with pregabalin in a mouse model of oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy

- Clinical pain research

- Pain-related distress and clinical depression in chronic pain: A comparison between two measures

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Scandinavian Journal of Pain

- Editorial comment

- Depressive symptoms associated with poor outcome after lumbar spine surgery: Pain and depression impact on each other and aggravate the burden of the sufferer

- Clinical pain research

- Depressive symptoms are associated with poor outcome for lumbar spine surgery

- Editorial comment

- Chronic compartment syndrome is an under-recognized cause of leg-pain

- Observational study

- Prevalence of chronic compartment syndrome of the legs: Implications for clinical diagnostic criteria and therapy

- Editorial comment

- Genetic susceptibility to postherniotomy pain. The influence of polymorphisms in the Mu opioid receptor, TNF-α, GRIK3, GCH1, BDNF and CACNA2D2 genes

- Clinical pain research

- Genetic susceptibility to postherniotomy pain. The influence of polymorphisms in the Mu opioid receptor, TNF-α, GRIK3, GCH1, BDNF and CACNA2D2 genes

- Editorial comment

- Important development: Extended Acute Pain Service for patients at high risk of chronic pain after surgery

- Observational study

- New approach for treatment of prolonged postoperative pain: APS Out-Patient Clinic

- Editorial comment

- Working memory, optimism and pain: An elusive link

- Original experimental

- The effects of experimental pain and induced optimism on working memory task performance

- Editorial comment

- A surgical treatment for chronic neck pain after whiplash injury?

- Clinical pain research

- A small group Whiplash-Associated-Disorders (WAD) patients with central neck pain and movement induced stabbing pain, the painful segment determined by mechanical provocation: Fusion surgery was superior to multimodal rehabilitation in a randomized trial

- Editorial comment

- Social anxiety and pain-related fear impact each other and aggravate the burden of chronic pain patients: More individually tailored rehabilitation need

- Clinical pain research

- Characteristics and consequences of the co-occurrence between social anxiety and pain-related fear in chronic pain patients receiving multimodal pain rehabilitation treatment

- Editorial comment

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation, paravertebral muscles training, and postural control in chronic low back pain

- Original experimental

- Influence of paravertebral muscles training on brain plasticity and postural control in chronic low back pain

- Editorial comment

- Is there a place for pulsed radiofrequency in the treatment of chronic pain?

- Clinical pain research

- Pulsed radiofrequency in clinical practice – A retrospective analysis of 238 patients with chronic non-cancer pain treated at an academic tertiary pain centre

- Editorial comment

- More postoperative pain reported by women than by men – Again

- Observational study

- Females report higher postoperative pain scores than males after ankle surgery

- Editorial comment

- The relationship between pain and perceived stress in a population-based sample of adolescents – Is the relationship gender specific?

- Observational study

- Pain is prevalent among adolescents and equally related to stress across genders

- Editorial comment

- The Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) – Revisited and rejuvenated?

- Clinical pain research

- Confirmatory factor analysis of 2 versions of the Brief Pain Inventory in an ambulatory population indicates that sleep interference should be interpreted separately

- Editorial comment

- Pain research reported at the 40th scientific meeting of the Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain in Reykjavik, Iceland May 26–27, 2016

- Abstracts

- Pain management strategies for effective coping with Sickle Cell Disease: The perspective of patients in Ghana

- Abstracts

- PEARL – Pain in early life. A new network for research and education

- Abstracts

- Searching for protein biomarkers in pain medicine – Mindless dredging or rational fishing?

- Abstracts

- Effectiveness of smart tablets as a distraction during needle insertion amongst children with port catheter: Pre-research with pre-post test design

- Abstracts

- Postoperative oxycodone in breast cancer surgery: What factors associate with analgesic plasma concentrations?

- Abstracts

- Sport participation and physical activity level in relation to musculoskeletal pain in a population-based sample of adolescents: The Young-HUNT Study

- Abstracts

- “Tears are also included” - women’s experience of treatment for painful endometriosis at a pain clinic

- Abstracts

- Predictors of long-term opioid use among chronic nonmalignant pain patients: A register-based national open cohort study

- Abstracts

- Coupled cell networks of astrocytes and chondrocytes are target cells of inflammation

- Abstracts

- Changes in opioid prescribing behaviour in Denmark, Sweden and Norway - 2006-2014

- Abstracts

- Opioid usage in Denmark, Norway and Sweden - 2006-2014 and regulatory factors in the society that might influence it

- Abstracts

- ADRB2, pain and opioids in mice and man

- Abstracts

- Retrospective analysis of pediatric patients with CRPS

- Abstracts

- Activation of epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFRs) following disc herniation induces hyperexcitability in the pain pathways

- Abstracts

- Pain rehabilitation with language interpreter, a multicenter development project

- Abstracts

- Trait-anxiety and pain intensity predict symptoms related to dysfunctional breathing (DB) in patients with chronic pain

- Abstracts

- Emla®-cream as pain relief during pneumococcal vaccination

- Abstracts

- Use of Complimentary/Alternative therapy for chronic pain

- Abstracts

- Effect of conditioned pain modulation on long-term potentiation-like pain amplification in humans

- Abstracts

- Biomarkers for neuropathic pain – Is the old alpha-1-antitrypsin any good?

- Abstracts

- Acute bilateral experimental neck pain: Reorganise axioscapular and trunk muscle activity during slow resisted arm movements

- Abstracts

- Mast cell proteases protect against histaminergic itch and attenuate tissue injury pain responses

- Abstracts

- The impact of opioid treatment on regional gastrointestinal transit

- Abstracts

- Genetic variation in P2RX7 and pain

- Abstracts

- Reversal of thermal and mechanical allodynia with pregabalin in a mouse model of oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy

- Clinical pain research

- Pain-related distress and clinical depression in chronic pain: A comparison between two measures