Genetic susceptibility to postherniotomy pain. The influence of polymorphisms in the Mu opioid receptor, TNF-α, GRIK3, GCH1, BDNF and CACNA2D2 genes

-

Maija-Liisa Kalliomäki

, Gabriel Sandblom

Abstract

Background and aims

Despite improvements in surgical technique, 5%-8% of patients undergoing herniorrhaphy still suffer from clinically relevant persistent postherniotomy pain. This is a problem at both individual and society levels. The aim of this study was to determine whether or not a single nucleotide polymorphism in a specific gene contributes to the development of persistent pain after surgery.

Methods

One hundred individuals with persistent postherniotomy pain, along with 100 without pain matched for age, gender and type of surgery were identified in a previous cohort study on patients operated for groin hernia. All patients underwent a thorough sensory examination and blood samples were collected. DNA was extracted and analysed for single nucleotide polymorphism in the Mu opioid receptor, TNF-α, GRIK3, GCH1, BDNF and CACNA2D2 genes.

Results

Patients with neuropathic pain were found to have a homozygous single nucleotide polymorph in the TNF-α gene significantly more often than pain-free patients (P =0.036, one-tailed test).

Conclusions

SNP in the TNF-α gene has a significant impact on the risk for developing PPSP.

Implications

The result suggests the involvement of genetic variance in the development of pain and this requires further investigation.

1 Introduction

Persistent postoperative pain (PPSP) is a debilitating problem affecting almost a third of all patients undergoing surgery to some degree [1]. It is seen after most surgical procedures, including hernia surgery [2], thoracic surgery [3], breast surgery [4] and gynaecologic surgery [5]. The underlying pathophysiology of PPSP comprises prolonged inflammation, nerve damage and genetic susceptibility to persistent pain, as described in many reviews, most recently by Reddi and Curran [6]. The inter-individual variability in susceptibility to PPSP may be explained by several factors influencing pain sensation including surgical trauma, gender, age, personality and comorbidity. According to previous studies open techniques reduce the risk of PPSP after herniotomy [7] as does younger age and female gender [2, 8]. Identification of genetic factors involved in the development of PPSP is crucial if we are to improve our understanding of the pathogenesis of pain, and define strategies for systematic treatment of acute postoperative pain in order to diminish the risk for PPSP [9].

Genes studied.

| Gene | SNP | Relation to pain? | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| GRIK3 | rs6691840 | Regulates glutamate release | [12, 13] |

| Ser310Ala, coding region | |||

| CACNA2D2 | rs5030977 G845C, intron2 |

Induced after peripheral nerve injury, development ofallodynia |

[37, 38] |

| OPMR | rs1799971 | SNP-decrease of receptor mRNA, 3-fold | [11, 39] |

| Asn40Asp, exon1 | stronger β-endorphin binding | ||

| BDNF | rs6265 | Pain modulation | [17] |

| Val66Met, exon5 | |||

| TNF-α | rs1800629 | Hyperalgesia: the inflammatory pathway and | [26] |

| G308A, promoter | by direct action on A and C fibres | ||

| GCH1 | rs8007267G > A | Enzyme catalysing NO, serotonin and | [15, 23] |

| rs3783641A > T | catecholamine synthesis | ||

| rs10483639C > G |

-

Abbreviations: GRIK3, glutamate ionotropic receptor 3; CACNA2D2, Voltage-dependent calcium channel subunit alpha-2/delta-2; OPMR, opioid Mu receptor; BDNF, brain derived neurotrophic factor; TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor α; GCH1, guanylate cyclohydrase 1-enzyme; NO, nitric oxide.

In a previous Swedish study, the estimated prevalence of PPSP was found to be 30% [8]. As herniorrhaphy is a relatively uniform procedure for a benign condition with few side-effects, it is an ideal model to investigate PPSP. In Sweden, data on all inguinal hernia repairs are registered in the Swedish Hernia Register (available at http://www.svensktbrackregister.se [accessed May 23, 2015]), including details on the patient, surgery, method of anaesthesia and adverse outcomes. The Inguinal Pain Questionnaire (IPQ) is a validated tool to measure postoperative pain after inguinal hernia repair [10].

By linking gene variance with clinical outcome, an association between genotype and phenotype can be assumed. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in one or both alleles may represent genetic variance, indicating an association between gene and phenotype. In the case of PPSP following hernia repair, the clinical outcome may be assessed with the IPQ and related to SNP in the genes hypothesised to be involved in the development of PPSP.

We chose six different genes for the following reasons: an SNP in the Mu opioid receptor (OPMR1) results in threefold stronger beta endorphin-binding than the wild receptor type [11]; the SNP in the coding region of glutamate ionotropic receptor 3 (GRIK3) has a potential impact on glutamate release [12, 13]; expression of calcium channels is induced in the dorsal root ganglions after peripheral nerve injury and may be involved in the development of allodynia [14]; guanylate cyclohydrase (GCH1) is an enzyme involved in the tetrahydrobiopterin pathway, thus affecting nitric oxide, serotonin and catecholamine synthesis [15]; the Val66Met genotype of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is associated with unstable angina and neuropsychiatric disorders [16, 17], but has not been studied in postoperative pain in humans; tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) polymorphism are associated with irritable bowel syndrome [18] and prolonged pain in lung cancer patients [19]. Details on the SNPs chosen are presented in Table 1.

The aim of this study was to see if known single nucleotide polymorphisms in these relevant pain-related genes are associated with PPSP.

2 Patients and methods

2.1 Study population

Assembly of the study cohort in which our patients were identified has been described in a previous report [20]. From the Swedish Hernia Register, patients residing in Uppsala County who had undergone hernia repair 1998-2004 were requested to fill in the Inguinal Pain Questionnaire (IPQ). In the Inguinal Pain Questionnaire [10] pain intensity is rated on a 7-step scale with each step linked restrictions from pain. In a validation of the questionnaire, it was shown to have a high reliability and validity for assessment of postherniotomy pain [10]. The IPQ also includes an item on preoperative pain. The group suffering from postherniotomy pain in the present study was selected based on patients stating pain of grade 3 (i.e. pain that could not be ignored but did not interfere with everyday activities) the past week. One hundred patients were included in each group. At the clinical examination, sensory testing was made according to a standardised procedure [20]. Neuropathic pain was defined as persisting pain in combination with sensory disturbance.

Written informed consent was obtained after detailed information about the study. Consent was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden. The study was not registered in any centralised database, but the study procedures followed the original protocol as approved from the ethics committee.

2.2 SNP genotyping

The genes studied are shown in Table 1.

2.3 Extraction of DNA

Blood samples from all participants in the study were collected in tubes containing EDTA and kept frozen at -20°C pending analysis. Genomic DNA was extracted from each sample using the Magtration 12 GC system (Precision System Science, Chiba, Japan) and the Magazorb® DNA Common Kit-200 (Precision System Science, Chiba, Japan) as described previously [21].

The DNA concentration was determined using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA).

2.4 Handy Bio-Strand

BDNF (rs6265), calcium channel, voltage dependent, subunit alpha 2/delta subunit 2 (CACNA2D2) (rs5030977), OPRM1 A118G (rs1799971) and TNF-α (rs1800629) were genotyped using the Handy Bio-Strand technique [21]. Briefly, DNA fragments containing the SNP site were amplified using two polymerase chain reaction (PCR) steps in a reaction mixture on a Mastercycler EP Gradient S (Eppendorf AG, Germany). The first PCR was carried out using the TaKaRa LA Taq (TaKaRam Shiga, Japan) at 95°C for 3 min, then 30 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 1 min. The second PCR was conducted with an identical programme with the addition of a HotGoldStar DNA polymerase (Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium). The PCR product was purified with a PCR CleanUp Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using the Magtration 12GC system, and the concentration was determined using NanoDrop (Long beach, CA, USA). Primers for the first and second PCR are shown in Table 2.

Primers and probes.

| Forward | Reverse | |

|---|---|---|

| Primers forthe first PCR | ||

| BDNF | CCGGTGAAAGAAAGCCCTA | CGCCGTTACCCACTCACTAATA |

| CACNA2D2 | AAGACGGATGGCCTCGTTA | ACATATGGATGGCCAGTTGAA |

| OPRM1 | GAAAAGTCTCGGTGCTCCTG | GCACACGATGGAGTAGAGGG |

| TNF-α | GGCTTGTCCCTGCTACCC | AATCATTCAACCAGCGGAAA |

| Primers for the second PCR | ||

| BDNF | TTC CTC CAG CAG AAA GAG AAG A | GAAGCAAACATCCGAGGACA |

| CACNA2D2 | TCC AAC ATC ACT CGG GCC AAC T | TTGTTGGCACAGGCCATCCACT |

| OPRM1 | GAA AAG TCT CGG TGC TCC TG | GCACACGATGGAGTAGAGGG |

| TNF-α | CAA CGG ACT CAG CTT TCT GAA | TGGAGAAACCCATGAGCTCATC |

| Sequences of positive controls for Handy Bio-Strand | ||

| BDNF | GCTCCTCTATCATGTGTTCGAAAGT | GCTCTTCTATCACGTGTTCGAAAGT |

| CACNA2D2 | GGTCAGGGTAGCTCCTGCCTCGGTT | GGTCAGGGTAGCCCCTGCCTCGGTT |

| OPRM1 | GTCGGACAGGTTGCCATCTAAGT | GTCGGACAGGTCGCCATCTAAGT |

| TNF-α | TGAACCCCGTCCTCATGCCCCTCAA | TGAACCCCGTCCCCATCGCCCTCAA |

| Probe sequences used for hybridisation in Handy Bio-Strand | ||

| BDNF | Cy5-GAACACATGATAG | Cy5-AACACGTGATA |

| CACNA2D2 | Cy5-CAGGAGCTACC | Cy5-CAGGGGCTACC |

| OPRM1 | Cy5-ATGGCGACCTG | Cy5-ATGGCAACCTG |

| TNF-α | CY5-GCATGAGGACG | Cy5-GCATGGGGACG |

| Non-labelled competitors for hybridisation in Handy Bio-Strand | ||

| BDNF | AACACATGATA | GCATGAGGACG |

| CACNA2D2 | CAGGAGCTACC | CAGGGGCTACC |

| OPRM1 | ATGGCAACCTG | ATGGCGACCTG |

| TNF-α | GCATGGGGACG | CGATGAGGACG |

The SNP analyses for BDNF, CACNA2D2, OPRM1 and TNF-α were performed with Handy Bio-Strand, where the amplified PCR product was spotted on the Bio-Strand, a micro-porous nylon thread. The product on the Bio-Strand was then hybridised with allele-specific oligonucleotide competitive hybridisation (ASOCH) using the Magtration 12 GC. Cy5-Tag1 with a Cy5 oligonucleotide used as a reference. The fluorescent signal was scanned and analysed with Hysoft software (Precision System Science, Chiba, Japan). The sequences of the positive controls used to confirm the genotyping, the Cy5-labelled probes and the non-labelled competitors are shown in Table 2.

2.5 TaqMan SNP genotyping assay

GRIK 3 (rs6691840) and the three GCH1 SNPs (rs8007267; rs3783641; rs10483639) were determined using the TaqMan SNP genotyping assay numbers C_25956068.20; C_25800745; C_1545138 and C_3044867 respectively (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Briefly, target-specific PCR primers and TaqMan MGB probes labelled with two special dyes were included in the assay. The primers and allele-specific probes were designed by Applied Biosystems. Genomic DNA (5 ng), water, TaqMan Universal PCR master mix and TaqMan genotyping assay mix were mixed to a total volume of 5 μl in each well on a 384-well plate. Genotyping was carried out using the ABI7900HT genetic detection system (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and with the following amplification protocol: 10min at 95°C and 40 cycles of 15s at 92°C and 1 min at 60°C.

2.6 PCR direct sequencing

In order to confirm data from TaqMan and Handy Bio-Strand genotyping, the OPRM1, TNF-alpha, CACNA2D2 and GRIK3 were also analysed using PCR direct sequencing. In short, amplification was conducted with one PCR at 94°C 2 min, 94°C 30 s, 60°C 30 s, 68 °C 1 min 30 cycles, 4 °C hold using the AccuPrime Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The PCR products were mixed with Exo-SAP-IT (USB, Cleveland, OH, USA) and diluted (1:20) in water. The dilution was incubated for 30 min at 37°C, following which Exo-SAP-IT was inactivated by heating for 20 min at 80 °C. Direct sequencing was performed at Macrogen (Seoul, South Korea).

2.7 Statistics

Comparison was made between the pain-free group and the group with persistent pain on an intention to analysis base.

A subgroup analysis was performed on patients who were found to have probable neuropathic pain at clinical examination [22].

Associations between SNP and PPSP were tested using the chi-square test by grouping patients with heterozygous SNP together with the smallest homozygous group. Tests for interaction were made between the genes by performing logistic regression analysis with PPSP as dependent variable and the genes as independent variables, testing also for interaction between SNP in BDNF and OPRM1 genes.

ANOVA was used to compare differences between multiple groups comparing GCH haplotypes.

3 Results

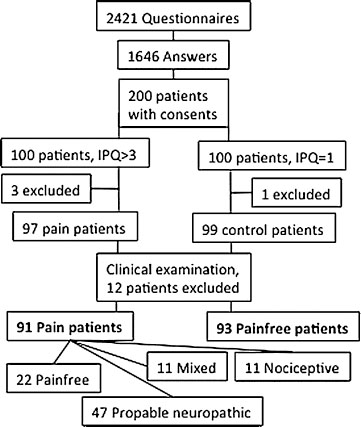

Patient recruitment is presented in the flow-chart (Fig. 1). One participant withdrew from the study, one could not be traced back to the original patient cohort since the personal registration number was not correctly recorded and two participants were excluded because of incoherent answers in the questionnaire. The distribution of men to women was 83 to 8 in the pain group and 87 to 6 in the control group. Mean age was 57.7 years (Standard Deviation [SD] 14.8 years) in the pain group and 58.0 years (SD 14.6 years) in the control group.

Flow chart showing patient recruitment. IPQ = inguinal pain questionnaire.

Median age was 58.8 years, range 21-85 years in the pain group and 59.7 years, range 21-85 years in the control group. Mean time since surgery was 49.1 months (SD 23.1 months) in the pain group and 56.5 years (21.8 years) in the control group. Laparoscopic techniques had been used in 11 cases (12.0%) in the pain group and 14 (15.0%) in the control group.

As part of the clinical examination the participants underwent sensory testing [20]. Through the sensory testing, patients with neuropathic pain were identified (Table 3). In the clinical examination, twelve participants with other causes for their pain were identified and excluded from further analysis [20].

The nature of pain was classified as probable neuropathic in more than half of the patients with pain. Demographics of the patients included are presented in Table 3. The time from operation to examination was significantly shorter in the pain group than in the pain-free group (P=0.027). Forty-two controls and 74 patients with pain had disturbances in sensory qualities.

The distribution of SNPs between the pain and the pain-free group is shown in Table 4.

Odds ratios (OR) for developing PPSP are shown in Table 4. We did not detect significant differences between the SNP carriers in the pain-free and pain groups.

78.7% of the patients in the probable neuropathic pain group carried the TNF-α G308A SNP, compared to 58.8% in the pain-free group (P = 0.036). There were no statistically significant differences in the distribution of the other SNPs studied between the pain-free and probable neuropathic pain groups (Table 5).

Interaction between the BDNF and OPRM1 SNPs did not reveal a significant odds ratio (data not shown). In the subgroup with probable neuropathic pain, the mean BDNF levels were higher in the OPRM1 A→A-group (24.52, SD 4.38) than in other OPRM1-SNP groups (22.91, SD 3.02), but significant difference was not reached (P = 0.217).

GCH haplotypes were analysed according to Lötsch et al. [23] (Tables 6 and 7). No significant differences were found between the groups pain/no pain (P=0.41) and neuropathic pain/other pain/no pain (P = 0.945). Risk ratio for developing pain (vs no pain) with “pain protective haplotype absent”-haplotype was 1.06 and for developing neuropathic pain (vs other pain or no pain) was 1.185.

4 Discussion

The present study shows a clear relationship between a specific single nucleotide polymorph on the TNF-α gene and the risk for PPSP following inguinal hernia surgery. Although the development of PPSP is multifactorial, the impact of genetic susceptibility was large enough to be identified even when obscured by other factors.

Over the last two decades, focus on pain as an outcome measure in both surgery and anaesthesia has increased [24]. Despite multimodal pain treatment, many patients still develop PSPP. PPSP constitutes a considerable financial burden for society [25]. Even if the surgical trauma and environmental factors are most important in the pathogenesis behind PPSP, genetic factors must also be considered [26]. Since genetic polymorphism has been linked to susceptibility to painful conditions, such as fibromyalgia, and response to analgesia, it has been suggested that genetic factors may explain why some patients develop chronic pain and others do not [27]. The results from recent studies have provided contradictory results. In a large study of patients undergoing hernia repair, hysterectomy and thoracotomy, no significant genetic difference were seen between patients perceiving persisting pain and controls [27]. On the other hand, functional variations in the COMT and GCH1 have been associated to postherniotomy pain and related impairment [28]. More studies confirming or negating these associations are needed before definite conclusions can be drawn.

Demographics of the patients.

| Pain-free group | Pain group | Neuropathic pain | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 93 | 91 | 47 |

| Men:women, N:N | 87:6 | 83:8 | 41:6 |

| Mean age, years±SD | 58.0±14.6 | 57.7±14.8 | 55.4±14.4 |

| Laparoscopic repairs, N (%) | 14(15.0) | 11 (12.0) | 7(14.9) |

| Mean time since surgery, months±SD | 56.5±21.8 | 49.1±23.1 | 52.2±26.1 |

| Preoperative pain, N (%) | 58 (62.4) | 73 (80.3) | 37 (78.7) |

Incidence (%) and risk ratios for developing PPSP by SNP. Associations between SNP and PPSP were tested using the chi-square test by grouping patients with heterozygous SNP together with the smallest homozygous group.

| Pain-free group (N = 93) | Pain group (N = 91) | P | RR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α (GG), N (%) rs1800629 | 55(59.1) | 66(72.5) | 0.056 | 1.38 (0.97-1.94) |

| CACNA2D2 (GG), N (%) rs5030977 | 65 (69.9) | 63 (69.2) | 0.922 | 0.98 (0.72-1.35) |

| GRIK (TT), N (%) rs6691840 | 47 (50.5) | 56(61.5%) | 0.133 | 1.26(0.93-1.71) |

| BDNF (GG), N (%) rs6265 | 60 (64.5) | 59 (64.8) | 0.964 | 1.01 (0.74-1.37) |

| OPRM1 (AA), N (%) rs1799971 | 65 (69.9) | 65 (71.4) | 0.819 | 1.04(0.75-1.45) |

-

CI = confidence interval.

Incidence (%) and risk for developing neuropathic pain according to SNP.

| No (more) pain (N = 114) | Neuropathic pain (N = 47) | Other type of pain(N = 23) | Pearson Chi2 (P) | RR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α (GG), N (%) rs1800629 | 67 (58.8) | 37(78.7) | 17(73.9) | 0.036 | 1.93(1.03-3.61) |

| CACNA2D2 (GG), N (%) rs5030977 | 80 (70.2) | 34(72.3) | 14(60.9) | 0.603 | 1.14(0.66-2.00) |

| GRIK (TT), N (%) rs6691840 | 59 (51.8) | 28(59.6) | 16(69.6) | 0.247 | 1.16(0.70-1.92) |

| BDNF (GG), N (%) rs6265 | 71 (62.3) | 30(63.8) | 18(78.3) | 0.340 | 0.96 (0.58-1.61) |

| OPRM1 (AA), N (%) rs1799971 | 80 (70.2) | 33(70.2) | 17(73.9) | 0.935 | 0.98(0.57-1.68) |

-

In the group "No more pain" are included all patients who did not have pain at the time of the clinical examination, i.e. initial pain-free group, and those from the initial pain group

Incidence (%) of GCH haplotypes and PPSP.

| GCH haplotype | Pain-free group (N = 93) | Pain group (N = 91) |

|---|---|---|

| Pain protective: absent, | 67 (72.0) | 67(73.6) |

| N (%) | ||

| Pain protective: | 22 (23.7) | 23(25.3) |

| heterozygous, N (%) | ||

| Pain protective: | 4 (4.3) | 1(1.1) |

| homozygous, N (%) |

TNF-α is an inflammatory cytokine that plays a crucial role in the development of PPSP both at the central and peripheral level [29]. Plasma TNF-α levels increase after surgery. Many attempts have been made to diminish the inflammatory cascade and consequent oedema, both by indirect anti-inflammatory drugs [30, 31] and cytokine antibodies [32]. Whether this reduces the risk of developing PPSP is, however still not determined. Our study shows that a single nucleotide polymorph in the TNF-alpha gene has a significant impact on the risk for developing neuropathic PPSP. It cannot, however, be excluded that the other genes studied are also involved in the development of PPSP since sufficient statistical power to detect the impact of those SNPs may have been lacking. A possible synergistic interaction between BDNF and OPMR was taken into account. A combination of SNPs on these genes was not associated with PPSP in the population studied. In this sample of 200 patients we could not confirm the relationship between PPSP (neuropathic pain in particular) and the GCH haplotypes.This, however, has recently been confirmed by Belfer et al. [28] in a larger study on 429 caucasian males.

Most patients in this study suffered from neuropathic pain [20]. Microglia are activated in neuropathic pain states and excrete cytokines, complement components and other transmission substances [33]. TNF-α is one of the cytokines known to be involved in the development of hyperalgesia and allodynia, features typical of neuropathic pain.

4.1 Strengths of the study

The follow-up time was more than one year for all patients, which is sufficient to define the pain as PPSP [34]. The study sample was drawn from a well-controlled cohort, with a high coverage. The clinical outcome was based on a validated patient-reported outcome measure.

4.2 Limitations of the study

Although the present study included some of the genes suggested to be involved in the pathogenesis, there are other genes that may play even more important, e.g. the catechol-O-methyl transferase/opioid receptor μ-1, which may be crucial for the Mu opioid receptor binding potential [35].

For each gene, only one or three SNP were analysed. Although more SNP could have been analysed, the SNPs with the greatest prevalence of polymorphism and assumed to have the strongest association with PPSP were selected.

The analysis was based on one-tailed tests, without correction for multiple testing, since the SNP a priori were assumed to be associated with increased risk of PPSP. Two-tailed tests or correction for multiple testing would have eliminated the statistical significance seen in this study.

The results from this study have not been replicated in other study groups. The present study was based on a limited sample, which may not be representative of other groups with PPSP. Future extended studies are necessary to confirm the findings of this study.

Incidence (%) of GCH haplotypes and type of pain.

| GCH haplotype | No(more) pain(N = 114) | Neuropathic pain(N = 47) | Othertype of pain(N = 23) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain protective absent, N (%) | 82(71.9) | 36(76.6) | 16(69.6) |

| Pain protective heterozygous, N (%) | 28(24.6) | 11(23.4) | 6(26.1) |

| Pain protective homozygous, N (%) | 4(3.5) | 0(0) | 1(4.3) |

-

There were no significant differences between the groups (ANOVA, P = 0.945).

5 Conclusions

The role of a single nucleotide polymorph on the TNF-α gene was found to be associated with neuropathic PPSP in this study on herniorrhaphy patients. The findings of this study should be corroborated by further studies including patients with neuropathic pain of causes other than trauma inflicted by hernia repair. Furthermore there are a considerable number of genes that have been hypothesised as influencing pain, of which we have analysed only six [35, 36]. Nevertheless, our results confirm the fact that genetic variance may play a role in the development of PPSP.

Highlights

We studied the association of genetic variation with persistent postoperative pain (PPSP).

We included six essential genes in the analysis.

A homozygous SNP in the TNF-α gene was associated with probable neuropathic PPSP.

DOI of refers to article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2016.02.007.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Johansen A, Romundstad L, Nielsen CS, Schirmer H, Stubhaug A. Persistent post-surgical pain inageneral population: prevalence and predictors inthe Tromso study. Pain 2012;153:1390-6.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Franneby U, Sandblom G, Nordin P, Nyren O, Gunnarsson U. Risk factors for long-term pain after hernia surgery. Ann Surg 2006;244:212-9.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Guastella V, Mick G, Soriano C, Vallet L, Escande G, Dubray C, Eschalier A. A prospective study of neuropathic pain induced by thoracotomy: incidence, clinical description, and diagnosis. Pain 2011;152:74-81.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Fecho K, Miller NR, Merritt SA, Klauber De More N, Hultman SC, Blau WS. Acute persistent postoperative pain after breast surgery. Pain Med 2009;10:708-15.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Brandsborg B, Nikolajsen L, Kehlet H, Jensen TS. Chronic pain after hysterectomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2008;52:327-31.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Reddi D, Curran N. Chronic pain after surgery: pathophysiology, risk factors and prevention. Postgrad Med J 2014;90:222-7.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Westin L, Wollert S, Ljungdahl M, Sandblom G, Gunnarsson U, Dahlstrand U. Less pain 1 year after TEP compared with lichtenstein using local anesthesia: data from a randomized controlled clinical trial. Ann Surg 2015.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Kalliomaki ML, Meyerson J, Gunnarsson U, Gordh T, Sandblom G. Long-term pain after inguinal hernia repair in a population-based cohort; risk factors and interferencewith daily activities. Eur J Pain 2008;12:214-25.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Oertel B, Lotsch J. Genetic mutations that prevent pain: implications for future pain medication. Pharmacogenomics 2008;9:179-94.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Franneby U, Gunnarsson U, Andersson M, Heuman R, Nordin P, Nyren O, Sandblom G. Validation of an Inguinal Pain Questionnaire for assessment of chronic pain aftergroin hernia repair. BrJ Surg 2008;95:488-93.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Bond C, LaForge KS, Tian M, Melia D, Zhang S, Borg L, Gong J, Schluger J, Strong JA, Leal SM, Tischfield JA, Kreek MJ, Yu L. Single-nucleotide polymorphism in the human Mu opioid receptor gene alters beta-endorphin binding and activity: possible implications for opiate addiction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998;95:9608-13.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Delorme RCA, Krebs M, Chabane N, Roy I, Millet B, MourenSimeoni MC, Maier W, Bourgeron T, Leboyer M. Frequency and transmission of glutamate receptors GRIK2 and GRIK3 polymorphisms in patients with obsessive compulsive disorder. Neuroreport 2004;15:699-702.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Begni S, Popoli M, Moraschi S, Bignotti S, Tura GB, Gennarelli M. Association between the ionotropic glutamate receptor kainate 3 (GRIK3) ser310ala polymorphism and schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 2002;7:416-8.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Luo ZD, Chaplan SR, Higuera ES, Sorkin LS, Stauderman KA, Williams ME, Yaksh TL. Upregulation of dorsal root ganglion (alpha)2(delta) calcium channel subunit and its correlation with allodynia in spinal nerve-injured rats. J Neurosci 2001;21:1868-75.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Tegeder I, Costigan M, Griffin RS, Abele A, Belfer I, Schmidt H, Ehnert C, Nejim J, Marian C, Scholz J, Wu T, Allchorne A, Diatchenko L, Binshtok AM, Goldman D, Adolph J, Sama S, Atlas SJ, Carlezon WA, Parsegian A, Lotsch J, Fillingim RB, Maixner W, Geisslinger G, Max MB, Woolf CJ. GTP cyclohydrolase and tetrahydrobiopterin regulate pain sensitivity and persistence. Nat Med 2006;12:1269-77.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Harrisberger F, Smieskova R, Schmidt A, Lenz C, Walter A, Wittfield K, Grabe HJ, Lang UE, Fusar-Poli P, Borgwart S. BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and hippocampal volume in neuropsychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2015;55:107-18.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Merighi A, Salio C, Ghirri A, Lossi L, Ferrini F, Betelli C, Bardoni R. BDNF as a pain modulator. Prog Neurobiol 2008;85:297-317.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Barkhordari E, Rezaei N, Ansaripour B, Larki P, Alighardashi M, AhmadiAshtiani HR, Mahmoudi M, Keramati MR, Habibollahi P, Bashashati M, EbrahimiDaryani N, AmirzargarAA. Proinflammatory cytokine gene polymorphisms in irritable bowel syndrome.J Clin Immunol 2010;30:74-9.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Reyes-Gibby CC, El Osta B, Spitz MR, Parsons H, Kurzrock R, Wu X, Shete S, Bruera E. The influence of tumor necrosis factor-alpha -308 G/A and IL-6-174 G/Con pain and analgesia response in lung cancerpatients receiving supportive care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2008;17:3262-7.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Kalliomaki ML, Sandblom G, Gunnarsson U, GordhT. Persistent pain after groin hernia surgery: a qualitative analysis of pain and its consequences for quality oflife. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2009;53:236-46.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Ginya H, Asahina J, Yoshida M, Segawa O, Asano T, Ikeda H, Hatano YM, Shishido M, Johansson BM, Zhou Q, Hallberg M, Takahashi M, Nyberg F, Tajima H, Yohda M. Development ofthe Handy Bio-Strand and its application to genotyping of OPRM1 (A118G). Anal Biochem 2007;367:79-86.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Haroutiunian S, Nikolajsen L, Finnerup NB, Jensen TS. The neuropathic component in persistent postsurgical pain: a systematic literature review. Pain 2013;154:95-102.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Lötsch J, Belfer I, Kirchhof A, Mishra BK, Max MB, Doehring A, Costigan M, Woolf CJ, Geisslinger G, Tegeder I. Reliable screening for a pain-protective haplotype in the GTP cyclohydrolase 1 gene (GCH1) through the use of 3 or fewer single nucleotide polymorphisms. Clin Chem 2007;53:1010-5.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Macrae WA. Chronic post-surgical pain: 10 years on. Br J Anaesth 2008;101:77-86.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Gustavsson A, Bjorkman J, Ljungcrantz C, Rhodin A, RivanoFischer M, Sjolund KF, Mannheimer C. Socio-economic burden of patients with a diagnosis related to chronic pain - register data of 840, 000 Swedish patients. Eur J Pain 2012;16:289-99.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Belfer IMD, Wu TPD, Kingman APD, Krishnaraju RKPD, Goldman D, Max M. Candidate gene studies of human pain mechanisms: methods for optimizing choice of polymorphisms and sample size. Anesthesiology 2004;100:1562-72.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Montes A, Roca G, Sabate S, Lao JI, Navarro A, Cantillo J, Canet J. GENDOLCAT study group. genetic and clinical factors associated with chronic postsurgical pain after hernia repair, hysterectomy, and thoracotomy: a two-year multicenter cohort study. Anesthesiology 2015;122:1123-41.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Belfer I, Dai F, Kehlet H, Finelli P, Qin L, Bittner R, Aasvang EK. Association of functional variations in COMT and GCH1 genes with postherniotomy pain and related impairment. Pain 2015;156:273-9.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Leung L, Cahill CM. TNF-alpha and neuropathic pain - a review.J Neuroinflammation 2010;7:27.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Esme H, Kesli R, Apiliogullari B, Duran FM, Yoldas B. Effects of flurbiprofen on CRP, TNF-alpha IL-6, and postoperative pain of thoracotomy. Int J Med Sci 2011;8:216-21.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Martin FMD, Martinez VMD, Mazoit JXMD, Bouhassira DMD, Cherif K, Gentili ME, Piriou P, Chauvin M, Fletcher D. Antiinflammatory effect of peripheral nerve blocks after knee surgery: clinical and biologic evaluation. Anesthesiology 2008;109:484-90.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Koninckx PR, Craessaerts M, Timmerman D, Cornillie F, Kennedy S. Anti-TNF-[alpha] treatment for deep endometriosis-associated pain: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Hum Reprod 2008;23:2017-23.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Colburn RW, Rickman AJ, DeLeo JA. The effect of site and type of nerve injury on spinal glial activation and neuropathic pain behavior. Exp Neurol 1999;157:289-304.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Werner MU, Kongsgaard UEI. Defining persistent post-surgical pain: is an update required? Br J Anaesth 2014;113:1-4.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Kolesnikov Y, Gabovits B, Levin A, Veske A, Qin L, Dai F, Belfer I. Chronic pain after lower abdominal surgery: do catechol-O-methyl transferase/opioid receptor Mu-1 polymorphisms contribute? Mol Pain 2013;9:19, 8069 9-19.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Stamer UM, Stuber F. Genetic factors in pain and its treatment. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2007;20:478-84.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Angeloni D, Duh FM, Wei MF, Johnson BE, Lerman MI.AG-to-Asingle nucleotide polymorphism in intron 2 of the human CACNA2D2 gene that maps at 3p21.3. Mol Cell Probes 2001;15:125-7.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Gao B, Sekido Y, Maximov A, Saad M, Forgacs E, Latif F, Wei MH, Lerman M, Lee JH, Perez-Reyes E, Bezprozvanny I, Minna JD. Functional properties of a new voltage-dependent calcium channel alpha(2)delta auxiliary subunit gene (CACNA2D2).J Biol Chem 2000;275:12237-42.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Zhang Y, Wang D, Johnson AD, Papp AC, Sadee W. Allelic expression imbalance of human Mu opioid receptor (OPRM1) caused by variant A118G. J Biol Chem 2005;280:32618-24.Search in Google Scholar

© 2015 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain

Articles in the same Issue

- Scandinavian Journal of Pain

- Editorial comment

- Depressive symptoms associated with poor outcome after lumbar spine surgery: Pain and depression impact on each other and aggravate the burden of the sufferer

- Clinical pain research

- Depressive symptoms are associated with poor outcome for lumbar spine surgery

- Editorial comment

- Chronic compartment syndrome is an under-recognized cause of leg-pain

- Observational study

- Prevalence of chronic compartment syndrome of the legs: Implications for clinical diagnostic criteria and therapy

- Editorial comment

- Genetic susceptibility to postherniotomy pain. The influence of polymorphisms in the Mu opioid receptor, TNF-α, GRIK3, GCH1, BDNF and CACNA2D2 genes

- Clinical pain research

- Genetic susceptibility to postherniotomy pain. The influence of polymorphisms in the Mu opioid receptor, TNF-α, GRIK3, GCH1, BDNF and CACNA2D2 genes

- Editorial comment

- Important development: Extended Acute Pain Service for patients at high risk of chronic pain after surgery

- Observational study

- New approach for treatment of prolonged postoperative pain: APS Out-Patient Clinic

- Editorial comment

- Working memory, optimism and pain: An elusive link

- Original experimental

- The effects of experimental pain and induced optimism on working memory task performance

- Editorial comment

- A surgical treatment for chronic neck pain after whiplash injury?

- Clinical pain research

- A small group Whiplash-Associated-Disorders (WAD) patients with central neck pain and movement induced stabbing pain, the painful segment determined by mechanical provocation: Fusion surgery was superior to multimodal rehabilitation in a randomized trial

- Editorial comment

- Social anxiety and pain-related fear impact each other and aggravate the burden of chronic pain patients: More individually tailored rehabilitation need

- Clinical pain research

- Characteristics and consequences of the co-occurrence between social anxiety and pain-related fear in chronic pain patients receiving multimodal pain rehabilitation treatment

- Editorial comment

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation, paravertebral muscles training, and postural control in chronic low back pain

- Original experimental

- Influence of paravertebral muscles training on brain plasticity and postural control in chronic low back pain

- Editorial comment

- Is there a place for pulsed radiofrequency in the treatment of chronic pain?

- Clinical pain research

- Pulsed radiofrequency in clinical practice – A retrospective analysis of 238 patients with chronic non-cancer pain treated at an academic tertiary pain centre

- Editorial comment

- More postoperative pain reported by women than by men – Again

- Observational study

- Females report higher postoperative pain scores than males after ankle surgery

- Editorial comment

- The relationship between pain and perceived stress in a population-based sample of adolescents – Is the relationship gender specific?

- Observational study

- Pain is prevalent among adolescents and equally related to stress across genders

- Editorial comment

- The Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) – Revisited and rejuvenated?

- Clinical pain research

- Confirmatory factor analysis of 2 versions of the Brief Pain Inventory in an ambulatory population indicates that sleep interference should be interpreted separately

- Editorial comment

- Pain research reported at the 40th scientific meeting of the Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain in Reykjavik, Iceland May 26–27, 2016

- Abstracts

- Pain management strategies for effective coping with Sickle Cell Disease: The perspective of patients in Ghana

- Abstracts

- PEARL – Pain in early life. A new network for research and education

- Abstracts

- Searching for protein biomarkers in pain medicine – Mindless dredging or rational fishing?

- Abstracts

- Effectiveness of smart tablets as a distraction during needle insertion amongst children with port catheter: Pre-research with pre-post test design

- Abstracts

- Postoperative oxycodone in breast cancer surgery: What factors associate with analgesic plasma concentrations?

- Abstracts

- Sport participation and physical activity level in relation to musculoskeletal pain in a population-based sample of adolescents: The Young-HUNT Study

- Abstracts

- “Tears are also included” - women’s experience of treatment for painful endometriosis at a pain clinic

- Abstracts

- Predictors of long-term opioid use among chronic nonmalignant pain patients: A register-based national open cohort study

- Abstracts

- Coupled cell networks of astrocytes and chondrocytes are target cells of inflammation

- Abstracts

- Changes in opioid prescribing behaviour in Denmark, Sweden and Norway - 2006-2014

- Abstracts

- Opioid usage in Denmark, Norway and Sweden - 2006-2014 and regulatory factors in the society that might influence it

- Abstracts

- ADRB2, pain and opioids in mice and man

- Abstracts

- Retrospective analysis of pediatric patients with CRPS

- Abstracts

- Activation of epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFRs) following disc herniation induces hyperexcitability in the pain pathways

- Abstracts

- Pain rehabilitation with language interpreter, a multicenter development project

- Abstracts

- Trait-anxiety and pain intensity predict symptoms related to dysfunctional breathing (DB) in patients with chronic pain

- Abstracts

- Emla®-cream as pain relief during pneumococcal vaccination

- Abstracts

- Use of Complimentary/Alternative therapy for chronic pain

- Abstracts

- Effect of conditioned pain modulation on long-term potentiation-like pain amplification in humans

- Abstracts

- Biomarkers for neuropathic pain – Is the old alpha-1-antitrypsin any good?

- Abstracts

- Acute bilateral experimental neck pain: Reorganise axioscapular and trunk muscle activity during slow resisted arm movements

- Abstracts

- Mast cell proteases protect against histaminergic itch and attenuate tissue injury pain responses

- Abstracts

- The impact of opioid treatment on regional gastrointestinal transit

- Abstracts

- Genetic variation in P2RX7 and pain

- Abstracts

- Reversal of thermal and mechanical allodynia with pregabalin in a mouse model of oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy

- Clinical pain research

- Pain-related distress and clinical depression in chronic pain: A comparison between two measures

Articles in the same Issue

- Scandinavian Journal of Pain

- Editorial comment

- Depressive symptoms associated with poor outcome after lumbar spine surgery: Pain and depression impact on each other and aggravate the burden of the sufferer

- Clinical pain research

- Depressive symptoms are associated with poor outcome for lumbar spine surgery

- Editorial comment

- Chronic compartment syndrome is an under-recognized cause of leg-pain

- Observational study

- Prevalence of chronic compartment syndrome of the legs: Implications for clinical diagnostic criteria and therapy

- Editorial comment

- Genetic susceptibility to postherniotomy pain. The influence of polymorphisms in the Mu opioid receptor, TNF-α, GRIK3, GCH1, BDNF and CACNA2D2 genes

- Clinical pain research

- Genetic susceptibility to postherniotomy pain. The influence of polymorphisms in the Mu opioid receptor, TNF-α, GRIK3, GCH1, BDNF and CACNA2D2 genes

- Editorial comment

- Important development: Extended Acute Pain Service for patients at high risk of chronic pain after surgery

- Observational study

- New approach for treatment of prolonged postoperative pain: APS Out-Patient Clinic

- Editorial comment

- Working memory, optimism and pain: An elusive link

- Original experimental

- The effects of experimental pain and induced optimism on working memory task performance

- Editorial comment

- A surgical treatment for chronic neck pain after whiplash injury?

- Clinical pain research

- A small group Whiplash-Associated-Disorders (WAD) patients with central neck pain and movement induced stabbing pain, the painful segment determined by mechanical provocation: Fusion surgery was superior to multimodal rehabilitation in a randomized trial

- Editorial comment

- Social anxiety and pain-related fear impact each other and aggravate the burden of chronic pain patients: More individually tailored rehabilitation need

- Clinical pain research

- Characteristics and consequences of the co-occurrence between social anxiety and pain-related fear in chronic pain patients receiving multimodal pain rehabilitation treatment

- Editorial comment

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation, paravertebral muscles training, and postural control in chronic low back pain

- Original experimental

- Influence of paravertebral muscles training on brain plasticity and postural control in chronic low back pain

- Editorial comment

- Is there a place for pulsed radiofrequency in the treatment of chronic pain?

- Clinical pain research

- Pulsed radiofrequency in clinical practice – A retrospective analysis of 238 patients with chronic non-cancer pain treated at an academic tertiary pain centre

- Editorial comment

- More postoperative pain reported by women than by men – Again

- Observational study

- Females report higher postoperative pain scores than males after ankle surgery

- Editorial comment

- The relationship between pain and perceived stress in a population-based sample of adolescents – Is the relationship gender specific?

- Observational study

- Pain is prevalent among adolescents and equally related to stress across genders

- Editorial comment

- The Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) – Revisited and rejuvenated?

- Clinical pain research

- Confirmatory factor analysis of 2 versions of the Brief Pain Inventory in an ambulatory population indicates that sleep interference should be interpreted separately

- Editorial comment

- Pain research reported at the 40th scientific meeting of the Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain in Reykjavik, Iceland May 26–27, 2016

- Abstracts

- Pain management strategies for effective coping with Sickle Cell Disease: The perspective of patients in Ghana

- Abstracts

- PEARL – Pain in early life. A new network for research and education

- Abstracts

- Searching for protein biomarkers in pain medicine – Mindless dredging or rational fishing?

- Abstracts

- Effectiveness of smart tablets as a distraction during needle insertion amongst children with port catheter: Pre-research with pre-post test design

- Abstracts

- Postoperative oxycodone in breast cancer surgery: What factors associate with analgesic plasma concentrations?

- Abstracts

- Sport participation and physical activity level in relation to musculoskeletal pain in a population-based sample of adolescents: The Young-HUNT Study

- Abstracts

- “Tears are also included” - women’s experience of treatment for painful endometriosis at a pain clinic

- Abstracts

- Predictors of long-term opioid use among chronic nonmalignant pain patients: A register-based national open cohort study

- Abstracts

- Coupled cell networks of astrocytes and chondrocytes are target cells of inflammation

- Abstracts

- Changes in opioid prescribing behaviour in Denmark, Sweden and Norway - 2006-2014

- Abstracts

- Opioid usage in Denmark, Norway and Sweden - 2006-2014 and regulatory factors in the society that might influence it

- Abstracts

- ADRB2, pain and opioids in mice and man

- Abstracts

- Retrospective analysis of pediatric patients with CRPS

- Abstracts

- Activation of epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFRs) following disc herniation induces hyperexcitability in the pain pathways

- Abstracts

- Pain rehabilitation with language interpreter, a multicenter development project

- Abstracts

- Trait-anxiety and pain intensity predict symptoms related to dysfunctional breathing (DB) in patients with chronic pain

- Abstracts

- Emla®-cream as pain relief during pneumococcal vaccination

- Abstracts

- Use of Complimentary/Alternative therapy for chronic pain

- Abstracts

- Effect of conditioned pain modulation on long-term potentiation-like pain amplification in humans

- Abstracts

- Biomarkers for neuropathic pain – Is the old alpha-1-antitrypsin any good?

- Abstracts

- Acute bilateral experimental neck pain: Reorganise axioscapular and trunk muscle activity during slow resisted arm movements

- Abstracts

- Mast cell proteases protect against histaminergic itch and attenuate tissue injury pain responses

- Abstracts

- The impact of opioid treatment on regional gastrointestinal transit

- Abstracts

- Genetic variation in P2RX7 and pain

- Abstracts

- Reversal of thermal and mechanical allodynia with pregabalin in a mouse model of oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy

- Clinical pain research

- Pain-related distress and clinical depression in chronic pain: A comparison between two measures