Racemic and unusual enantiomeric crystal forms of N-cycloalkyl-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamides and their biological activity

-

Svitlana V. Shishkina

, Igor V. Ukrainets

Abstract

The absence of a stereogenic center in N-cycloalkyl-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamides (cycloalkyl moiety is cyclopropyl, cyclobutyl, cyclopentyl, cyclohexyl, cycloheptyl, cyclooctyl) does not interfere with their ability to be crystallized from the ethanol solution into a centrosymmetric or a non-centrosymmetric space group. The non-centrosymmetric crystals containing opposite conformer of a molecule were obtained using aqueous acetic acid as another solvent. Pairs of enantiomorphic crystals have the same crystal shape and unit cell parameters and can only be recognized by X-ray diffraction study due to anomalous dispersion. The formation of such unusual enantiomers may be caused by the ability of the sulfur atom to become a stereogenic center due to the different participation of the oxygen atoms of the sulfonyl group in hydrogen bonds formation. Similar to classical polymorphic modifications, the enantiomorphic crystals may differ in their biological activity. Analgesic activity does not depend on the type of conformation of 1,2-benzothiazine, while the diuretic effect is much stronger in the case of the crystals containing one type of conformer. This property of 1,2-benzothiazines is to be expected of great importance in future drug developments.

1 Introduction

Being a well-known phenomenon, the frequent occurrence of polymorphism in the solids of several classes of compounds remains not completely understood. Despite a large number of studies of various polymorphic modifications and their properties, as well as some generalizations of these data are reported, 1 , 2 the crystallization process is unpredictable in many cases and thus can be surprising. McCrone provocatively stated that the number of polymorphic forms is proportional to the time and money spent in research on the compound, 3 which still proves to be correct. The task of polymorph search has become especially important for biologically and medically active organic compounds that can be applied as drugs. 4 , 5 Different crystalline forms such as polymorphs, salts, solvates (solvatomorphs 5 ) and co-crystals are capable to exhibit different physicochemical properties (melting point, plasticity, solubility, hygroscopicity, chemical reactivity), which may affect the technological and biopharmaceutical properties of active ingredients (compactibility, dissolution rate, bioavailability, pharmacological activity, stability). 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 Taking into account this fact, the capability to form different crystal forms should be studied thoroughly for each organic compound possessing biological activity. The absence of information about polymorphic modifications of a drug does not necessarily mean its incapability to form various crystal structures. The truth of the matter is that this drug should be studied more thoroughly.

The development of computational chemistry methods encourages many groups to solve crystal structure prediction tasks. 10 The application of crystal structure prediction general principles to organic compounds 11 , 12 allows also to predict polymorphic modifications. 13 Nevertheless, experimental studies with various crystallization conditions of organic compounds can give some unexpected results.

Hydrohlorothiazide has been used since 1959 in the field of cardiovascular diseases. It was reported that it exists as a true racemic form with the space group P21/c. 14 The recent Pasteur-style study showed that this drug can be crystallized as a mixture of two enantiomeric crystal forms in the Sohncke space group P21, despite the absence of any stereogenic atom in the molecule. 15

The N-benzyl-4-hydroxy-1-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamide (I) and N-(2,6-dimethylphenyl)-4-hydroxy-2,2-dioxo-1Н-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamide (II) also do not have any stereogenic atom but they are crystalized in the Sohncke space group P212121 (compound I) or P31/P32 (compound II), respectively. 16 , 17 We have found the solvent and the crystallization conditions to obtain the pure enantiomorphic forms, which contain molecules with different conformations (IA and IB or IIA and IIB) counterposed to each other in relation to the plane. Being structural analogues of piroxicam, 2,1-benzothiazines possess high analgesic, anti-inflammatory and diuretic activity. 18 , 19 , 20 The testing of the enantiomorphic pair IA-IB revealed a much stronger analgesic effect of one pure enantiomorph as compared to the other crystal form as well as piroxicam. 16 Form IIA displayed three times stronger analgesic activity than form IIB but acted much weaker as anti-inflammatory agent. 17

In this study we performed the systematic study of a series of new N-cycloalkyl-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamides. The crystallization, molecular and crystal structures as well as analgesic and diuretic properties are the main subjects of this investigation.

2 Experimental part

2.1 Materials and equipment

1Н NMR (proton nuclear magnetic resonance) spectra were recorded on a Varian Mercury-400 (Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA) instrument (400 MHz) in hexadeuterodimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO‑d6) with tetramethylsilane as internal standard. The chemical shift values were recorded on a δ scale and the coupling constants (J) in hertz. The following abbreviations were used in reporting spectra: s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, m = multiplet.

The ESI-LC/MS (electrospray ionization liquid chromato-mass) spectra were recorded on a modular Agilent Technologies 1260 Infinity system with 6530 Accurate-Mass Q-TOF LC/MS (G6530B#200 ESI) mass-spectrometric detector (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). The chromatography conditions were: Agilent Extend-С18 column of 2.1 × 50 mm; the sorbent particle size – 1.8 μm; the mobile phase flow rate – 0.25 mL/min; the column temperature – 30°С; the injection volume – 1.0 μL; the mobile phase composition – 0.1 % formic acid in methanol.

The elemental analysis was performed on a Euro Vector EA-3000 (Eurovector SPA, Redavalle, Italy) microanalyzer. The melting points were determined in a capillary using a electrothermal IA9100X1 (Bibby Scientific Limited, Stone, UK) digital melting point apparatus.

2.2 Synthesis

The corresponding cycloalkylamine (0.011 mol) was added to a solution of 4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxylic acid imidazolide (2) (2.89 g, 0.01 mol) in anhydrous DMF (5 mL) and kept for 10 h at the temperature of 80 °С in a tightly closed bottle made of thick glass. The reaction mixture was cooled, diluted by adding cold water, and adjusted to pH ∼3 by adding dilute (1:1) hydrochloric acid. The precipitate formed was filtered, washed with cold water, dried, and recrystallized from corresponding solvent.

2.3 Physical data

N-(Cyclopropyl)-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ 6 ,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamide (3a, 3b). The yield was: 2.50 g (90 %); colorless crystals of 3a crystallized from an ethanol solution, colorless crystals of 3b crystallized from a mixture AcOH/H2O in the ratio 3:1; m.p. 223–225 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δ 11.62 (br. s, 1H; SO2NH), 8.63 (d, 3JH,H = 4.1 Hz, 1H; CONH), 7.67 (d, 3JH,H = 8.0 Hz, 1H; Н-5), 7.43 (t, 3JH,H = 7.7 Hz, 1H; H-7), 7.16 (t, 3JH,H = 7.7 Hz, 1H; H-6), 7.08 (d, 3JH,H = 8.0 Hz, 1H; H-8), 2.82–2.74 (m, 1H; NСН), 2.22 (s, 3H; 4-СН3), 0.70–0.64 (m, 2H; CH2), 0.51–0.46 (m, 2H; CH2); ESI-LC/MS: m/z (%): 279 (100) [M+H]+, 222 (91), 130 (11); elemental analysis calcd. for C13H14N2O3S (in %): C 56.10, H 5.07, N 10.06, S 11.52; found: C 56.16, H 5.14, N 10.11, S 11.45.

N-(Cyclobutyl)-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ 6 ,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamide (4). The yield was: 2.60 g (89 %); colorless crystals crystallized from an ethanol solution; m.p. 211–213 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δ 11.65 (br. s, 1H; SO2NH), 8.84 (d, 3JH,H = 7.5 Hz, 1H; CONH), 7.68 (d, 3JH,H = 7.9 Hz, 1H; Н-5), 7.44 (t, 3JH,H = 7.6 Hz, 1H; H-7), 7.18 (t, 3JH,H = 7.7 Hz, 1H; H-6), 7.08 (d, 3JH,H = 7.9 Hz, 1H; H-8), 4.35–4.21 (m, 1H; NСН), 2.24 (s, 3H; 4-СН3), 2.20–2.12 (m, 2H; 2-CH2), 2.04–1.90 (m, 2H; 4-CH2), 1.71–1.58 (m, 2H; 3-CH2); ESI-LC/MS: m/z (%): 293 (100) [M+H]+, 222 (82), 130 (15); elemental analysis calcd. for C14H16N2O3S (in %): C 57.52, H 5.52, N 9.58, S 10.97; found: C 57.45, H 5.57, N 9.66, S 11.05.

N-(Cyclopenttyl)-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ 6 ,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamide (5). The yield was: 2.66 g (87 %); colorless crystals crystallized from an ethanol solution; m.p. 192–194 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δ 11.59 (br. s, 1H; SO2NH), 8.54 (d, 3JH,H = 7.2 Hz, 1H; CONH), 7.67 (d, 3JH,H = 8.1 Hz, 1H; Н-5), 7.43 (t, 3JH,H = 7.5 Hz, 1H; H-7), 7.17 (t, 3JH,H = 7.6 Hz, 1H; H-6), 7.08 (d, 3JH,H = 8.0 Hz, 1H; H-8), 4.16–4.06 (m, 1H; NСН), 2.24 (s, 3H; 4-СН3), 1.88–1.77 (m, 2H; 2-CH2), 1.67–1.58 (m, 2H; 5-CH2), 1.54–1.42 (m, 4H; 3,4-CH2); ESI-LC/MS: m/z (%): 307 (100) [M+H]+, 222 (57), 130 (8); elemental analysis calcd. for C15H18N2O3S (in %): C 58.80, H 5.92, N 9.14, S 10.47; found: C 58.73, H 5.84, N 9.21, S 10.55.

N-(Cyclohexyl)-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ 6 ,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamide (6a, 6b). The yield was: 2.88 g (90 %); colorless crystals 6a crystallized from a mixture AcOH/H2O in the ratio 3:1, colorless crystals 6b crystallized from an ethanol solution; m.p. 258–260 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δ 11.58 (br. s, 1H; SO2NH), 8.45 (d, 3JH,H = 7.9 Hz, 1H; CONH), 7.67 (d, 3JH,H = 7.8 Hz, 1H; Н-5), 7.43 (t, 3JH,H = 7.6 Hz, 1H; H-7), 7.14 (t, 3JH,H = 7.7 Hz, 1H; H-6), 7.09 (d, 3JH,H = 7.9 Hz, 1H; H-8), 3.71–3.60 (m, 1H; NСН), 2.25 (s, 3H; 4-СН3), 1.81–1.73 (m, 2H; 2-CH2), 1.72–1.63 (m, 2H; 6-CH2), 1.32–1.17 (m, 6H; 3,4,5-CH2); ESI-LC/MS: m/z (%): 321 (100) [M+H]+, 222 (75), 130 (6); elemental analysis calcd. for C16H20N2O3S (in %): C 59.98, H 6.29, N 8.74, S 10.01; found: C 60.06, H 6.34, N 8.66, S 9.95.

N-(Cycloheptyl)-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ 6 ,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamide (7a, 7b). The yield was: 3.00 g (90 %); colorless crystals 7a crystallized from an ethanol solution, colorless crystals 7b crystallized from a mixture AcOH/H2O in the ratio 3:1; m.p. 234–236 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δ 11.57 (br. s, 1H; SO2NH), 8.50 (d, 3JH,H = 7.7 Hz, 1H; CONH), 7.67 (d, 3JH,H = 8.0 Hz, 1H; Н-5), 7.43 (t, 3JH,H = 7.7 Hz, 1H; H-7), 7.17 (t, 3JH,H = 7.7 Hz, 1H; H-6), 7.08 (d, 3JH,H = 8.0 Hz, 1H; H-8), 3.90–3.81 (m, 1H; NСН), 2.24 (s, 3H; 4-СН3), 1.86–1.75 (m, 2H; 2-CH2), 1.66–1.56 (m, 2H; 7-CH2), 1.54–1.32 (m, 8H; 3,4,5,6-CH2); ESI-LC/MS: m/z (%): 335 (100) [M+H]+, 222 (82), 130 (13); elemental analysis calcd. for C17H22N2O3S (in %): C 61.05, H 6.63, N 8.38, S 9.59; found: C 61.10, H 6.55, N 8.47, S 9.67.

N-(Cyclooctyl)-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ 6 ,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamide (8). The yield was: 3.31 g (95 %); colorless crystals crystallized from an ethanol solution; m.p. 240–242 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δ 11.57 (br. s, 1H; SO2NH), 8.49 (d, 3JH,H = 7.7 Hz, 1H; CONH), 7.67 (d, 3JH,H = 7.7 Hz, 1H; Н-5), 7.43 (t, 3JH,H = 7.5 Hz, 1H; H-7), 7.17 (t, 3JH,H = 7.6 Hz, 1H; H-6), 7.08 (d, 3JH,H = 8.0 Hz, 1H; H-8), 3.96–3.85 (m, 1H; NСН), 2.24 (s, 3H; 4-СН3), 1.78–1.67 (m, 2H; 2-CH2), 1.66–1.56 (m, 2H; 2-CH2), 1.54–1.37 (m, 10H; 3,4,5,6,7-CH2); ESI-LC/MS: m/z (%): 349 (100) [M+H]+, 222 (71), 130 (12), elemental analysis calcd. for C18H24N2O3S (in %): C 62.04, H 6.94, N 8.04, S 9.20; found: C 62.13, H 7.02, N 7.95, S 9.14.

3 Spectral characterization

3.1 NMR spectra

The 1Н NMR spectra of the studied compounds are very similar. The protons of the cyclic sulfamide groups reveal themselves as widened singlet at 11.65–11.57 ppm. The doublet signals of carbamide protons are shifted to an upfield (8.84–8.45 ppm). The benzene protons of the bicyclic fragment show signals in “aromatic” area which represent a pattern typical for benzothiazines unsubstituted in position 1. It contains four well separated signals with intensity of 1H: H5 – doublet (7.68–7.67 ppm), Н7 – triplet (7.44–7.43 ppm), Н6 – triplet (7.18–7.14 ppm), and Н8 – doublet (7.09–7.08 ppm). Then there are multiplets of CONCH-methine protons (4.35–2.74 ppm) and singlets of 4-methyl groups (2.25–2.22 ppm). The protons of two cycloalkyl CH2 groups, which are located next to the methine fragment, in most cases are manifested by two multiplets of intensity 2H each at 2.20–1.73 and 2.04–1.57 ppm. Finally, there are multiplets of the corresponding intensity due to all other cycloalkyl CH2 units in the strongest field (1.71–1.17 ppm). Cyclopropylamide 3 is the only exception to the series. Due to the negative magnetic anisotropy of the three-membered cycle, 21 the protons of the two CH2 groups of the cyclopropane ring resonate in an even higher field – 0.70–0.64 and 0.51–0.46 ppm.

3.2 Chromato-mass spectra

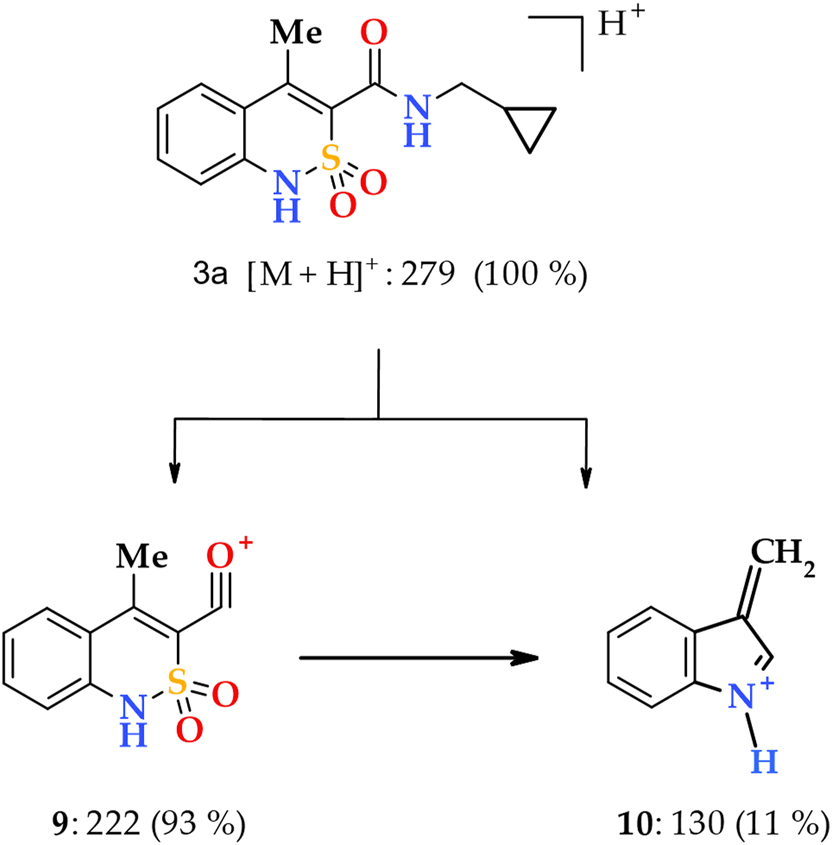

The electrospray ionization liquid chromato-mass spectra of N-cycloalkylamides 3–8 are similar to the ones described earlier for N-hetarylalkyl-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamides. 22 The highly intense peaks of protonated molecular ions [M+H]+ are present in all spectra (Scheme S1). The primary fragmentation pathways of the protonated molecular ions are completely identical. The fragmentation begins with the cleavage of the CO‒NHCycloalkyl terminal amide bond, as evidenced by the peaks of the most massive fragment of the acylium cation 9 with m/z 222. However, even a trace of the second fragment, which corresponds to [cycloalkyl amine + H] + ion, was not detected as a result of this decay. The low-intensive peak with m/z 130 should be noted as a distinctive feature of the N-cycloalkylamides 3–8 mass spectra due to the fact that such a peak has never been observed for other 4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamides. The presence of this peak indicates a relatively easy destruction of the acylium cation 9, which undergoes decarbonylation and SO2 extrusion with the formation of 3-methyleneindol-1-ium 10 (Scheme 1). However, 3-methyleneindol-1-ium 10 may be formed due to a primary decay of the molecular ion.

The primary fragmentation of the N-cyclopentylamide 3a protonated molecular ion.

3.3 X-ray diffraction study

Crystal data and reflections were measured on an “Xcalibur-3” diffractometer (graphite monochromated MoKα radiation, CCD detector, ω-scaning). The structures were solved using the Shelxtl package. 23 Positions of the hydrogen atoms were located from electron density difference maps and refined by different “riding” models with Uiso = nUeq (n = 1.5 for methyl groups and n = 1.2 for other hydrogen atoms) of the carrier atom. The hydrogen atoms of amino groups were refined isotropically. All experimental data and structure refinement details are summarized in Table 1.

Crystallographic data and experimental parameters for compounds 3–8.

| 3a | 3b | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical formula | C13H14N2O3S | C13H14N2O3S | C14H16N2O3S | C15H18N2O3S |

| M r | 278.32 | 278.32 | 292.35 | 306.37 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic | Monoclinic | Trigonal | Monoclinic |

| a, Ǻ | 7.7876(9) | 7.7967(7) | 28.250(3) | 15.4919(16) |

| b, Ǻ | 4.9271(5) | 4.9380(3) | 28.250(3) | 15.6858(13) |

| c, Ǻ | 16.9214(14) | 16.9353(16) | 9.2799(17) | 13.5489(14) |

| α, deg | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| β, deg | 101.693(10) | 101.666(9) | 90 | 110.266(12) |

| γ, deg | 90 | 90 | 120 | 90 |

| Unit cell volume/Å3 | 635.80(11) | 638.54(9) | 6,413.9(19) | 3,088.6(6) |

| Temperature/K | 293 | 293 | 293 | 293 |

| Space group | P21 | P21 | R3c | P21/c |

| Z/Z′ | 2 | 2 | 18 | 8 |

| 2Θmax, deg | 60 | 60 | 50 | 50 |

| μ (mm−1) | 0.260 | 0.259 | 0.236 | 0.221 |

| No. of reflections measured | 5,832 | 5,704 | 14,950 | 25,547 |

| No. of ndependent reflections | 3,545 | 2,890 | 2,354 | 5,437 |

| R int | 0.0678 | 0.0541 | 0.1141 | 0.0792 |

| Final R1 values (I > 2σ(I)) | 0.0593 | 0.0570 | 0.0571 | 0.0569 |

| Final wR(F2) values (I > 2σ(I)) | 0.1073 | 0.1395 | 0.1150 | 0.1354 |

| Final R1 values (all data) | 0.1013 | 0.0687 | 0.0854 | 0.0826 |

| Final wR(F2) values (all data) | 0.1331 | 0.1566 | 0.1272 | 0.1514 |

| Goodness of fit on F2 | 0.973 | 1.049 | 1.010 | 1.049 |

| Flack parameter | −0.14(12) | −0.04(11) | 0.05(13) | |

| CCDC | 1995753 | 1995754 | 1995755 | 1995760 |

| 6a | 6b | 7a | 7b | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical formula | C16H20N2O3S | C16H20N2O3S | C17H22N2O3S | C17H22N2O3S | C18H24N2O3S |

| M r | 320.40 | 320.40 | 334.42 | 334.42 | 348.45 |

| Crystal system | Orthorhombic | Orthorhombic | Orthorhombic | Orthorhombic | Monoclinic |

| a, Ǻ | 4.8946(3) | 4.8984(10) | 4.9659(12) | 4.9684(7) | 14.236(3) |

| b, Ǻ | 17.4251(9) | 17.420(2) | 17.659(2) | 17.646(3) | 9.316(1) |

| c, Ǻ | 18.4005(17) | 18.390(3) | 18.747(3) | 18.711(4) | 14.848(3) |

| α, deg | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| β, deg | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 115.71(2) |

| γ, deg | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| Unit cell volume/Å3 | 1,569.36(19) | 1,569.2(4) | 1,643.9(5) | 1,640.4(5) | 1774.3(5) |

| Temperature/K | 293 | 293 | 293 | 293 | 293 |

| Space group | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P21/c |

| Z/Z′ | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 2Θmax, deg | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| μ (mm−1) | 0.221 | 0.221 | 0.214 | 0.214 | 0.201 |

| No. of reflections measured | 10,246 | 11,024 | 10,458 | 11,096 | 14,780 |

| No. of ndependent reflections | 2,753 | 2,751 | 2,878 | 2,873 | 3,119 |

| R int | 0.0754 | 0.1559 | 0.0799 | 0.1570 | 0.0981 |

| Final R1 values (I > 2σ(I)) | 0.0488 | 0.0676 | 0.0603 | 0.0819 | 0.0870 |

| Final wR(F2) values (I > 2σ(I)) | 0.0924 | 0.0838 | 0.1425 | 0.1573 | 0.2551 |

| Final R1 values (all data) | 0.0767 | 0.1620 | 0.0794 | 0.1665 | 0.1373 |

| Final wR(F2) values (all data) | 0.1051 | 0.1064 | 0.1601 | 0.1882 | 0.2847 |

| Goodness of fit on F2 | 1.007 | 0.928 | 1.061 | 0.976 | 1.063 |

| Flack parameter | −0.01(11) | 0.1(2) | −0.08(10) | 0.0(2) | |

| CCDC | 1995756 | 1995757 | 1995758 | 1995761 | 1995759 |

The final atomic coordinates, and crystallographic data for the studied molecule have been deposited to The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center, 12 Union Road, CB2 1EZ, UK (fax: +44-1223-336033; e-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk). The deposition numbers are given in Table 1.

3.4 Pharmacological tests

All pharmacological experiments were performed in accordance with the European Convention on the Protection of Vertebrate Animals Used for Experimental and Other Scientific Purposes.

The analgesic activity was studied on white Wistar male rats weighing 160–190 g (10 animals for each test substance) using the “hot plate” model. 24 First, the experimental animals received the test samples orally (20 mg/kg) in the form of thin water suspension stabilized by Tween-80. The threshold of pain sensitivity was determined at 56.4 °C. The animals’ response to thermal irritation was considered to be bouncing, licking or shaking their paws. The time of the onset of pain reaction was recirded in seconds from the beginning of contact of the extremities of the animal with the surface of the plate. The analgesic effect (in %) was assessed by the change of the latent period in 1.0, 1.5 and 2.0 h after introduction of the test substances and reference drug compared to the initial level taken as a control.

The effect of cycloalkylamides 3–8 on the excretory function of the kidneys was studied in white outbred rats of both genders with weights of 180–200 g by the standard method. 25 All experimental animals were given a water load calculated in 25 mL/kg via a gastric tube. The control group was given only a similar amount of water with Tween-80. The tested cycloalkylamides 3–8 were introduced per os in the form of thin water suspension stabilized by Tween-80. Then the animals were placed in “metabolic cages”. The primary screening was carried out in the dose of 10 mg/kg. The values of excretion were registered after 4 h and compared with the control, as well as a known diuretic, Hydrochlorothiazide, used in its effective dose of 40 mg/kg.

Ten experimental animals were involved to obtain statistically reliable results. The significance level of the confidence interval accepted in this work was p ≤ 0.05 in testing each of cycloalkylamides 3–8, the reference drugs and control.

4 Results and discussion

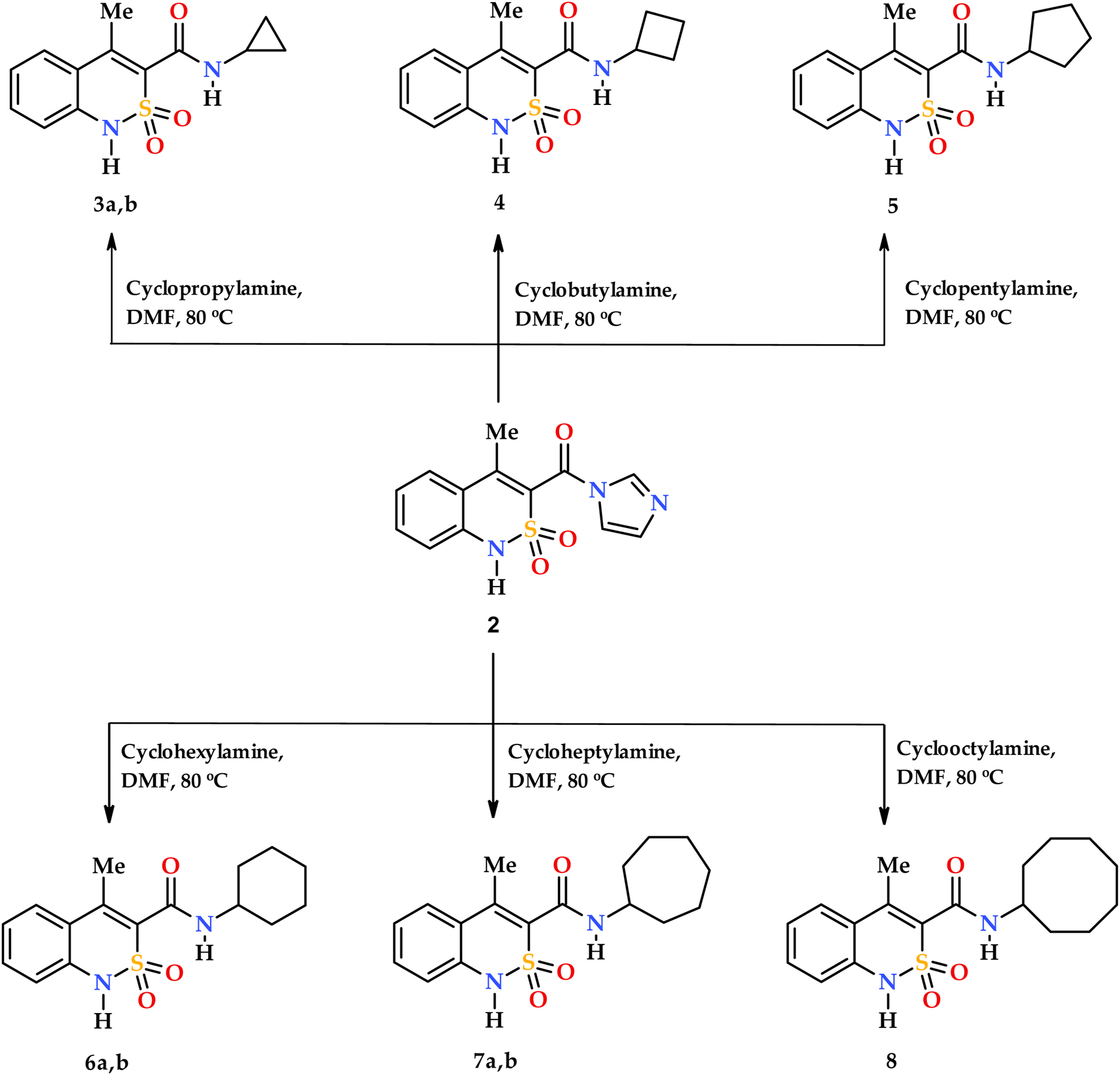

The 4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxylic acid (1) as well as its imidazolide derivative (2) can be used as precursors (starting materials) for the synthesis of N-cycloalkyl-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamides 3–8. 22 , 26 Both methods give a good result concerning the yield and differ only by the fact that the synthesis from the acid 1 provides for imidazolide 2 acquisition on the first stage without its separation out in pure form. In the present study all the compounds were synthesized from imidazolide 2 due to reaction with the primary cycloalkylamines (Scheme 2). The corresponding N-R-amides 3–8 have been obtained with a high yield.

Synthesis of N-cycloalkyl-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamides 3–8.

The two 2,1-benzothiazines (Figure 1) studied earlier contain hydroxyl and carbamide groups in vicinal position. 16 , 17 It results in the formation of one O–H⋯O intramolecular hydrogen bond, which stabilizes the coplanarity of the carbamide fragment to the endocyclic double bond. The rigid position of the NH fragment causes its participation in the intramolecular hydrogen bond with one of the oxygen atoms of the sulfonyl group. As a result, the sulfur atom takes on stereogenic properties.

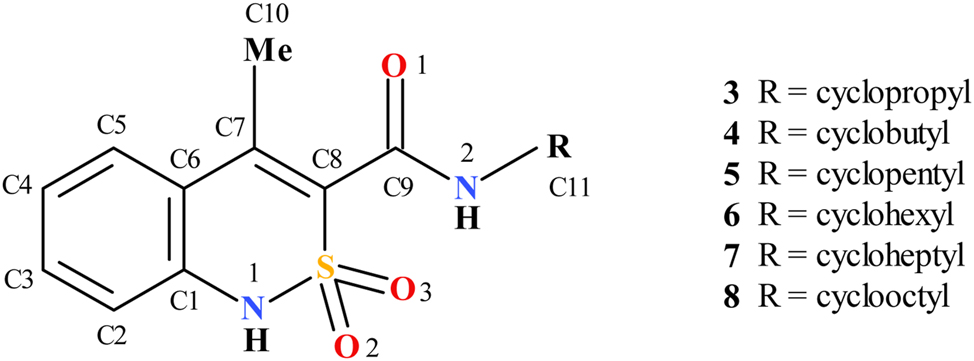

The replacement of the hydroxyl group by the methyl substituent in the molecules 3–8 (Scheme 3) creates pre-conditions for carbamide group rotation around the C8–C9 bond. Its rotation in relation to the C7–C8 double bond is a result of two opposite factors: a) steric repulsion between methyl and carbonyl groups, which promotes a stronger turn; b) conjugation between endocyclic double bond and carbonyl group as well as a possible N–H⋯O intramolecular hydrogen bond with an oxygen atom of the sulfonyl group, which promotes a weaker rotation. Earlier it was shown that the molecular conformation detected in a crystal may influence the biological properties. 27

Studied compounds with atom numeration scheme.

At the room temperature the N-cycloalkylamides 3–8 are well soluble in DMSO and DMF, poorly soluble in lower alcohols and non-soluble in water. All the synthesized N-cycloalkyl-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1- benzothiazine-3-carboxamides were crystallized primarily from ethanol solution as colorless crystals.

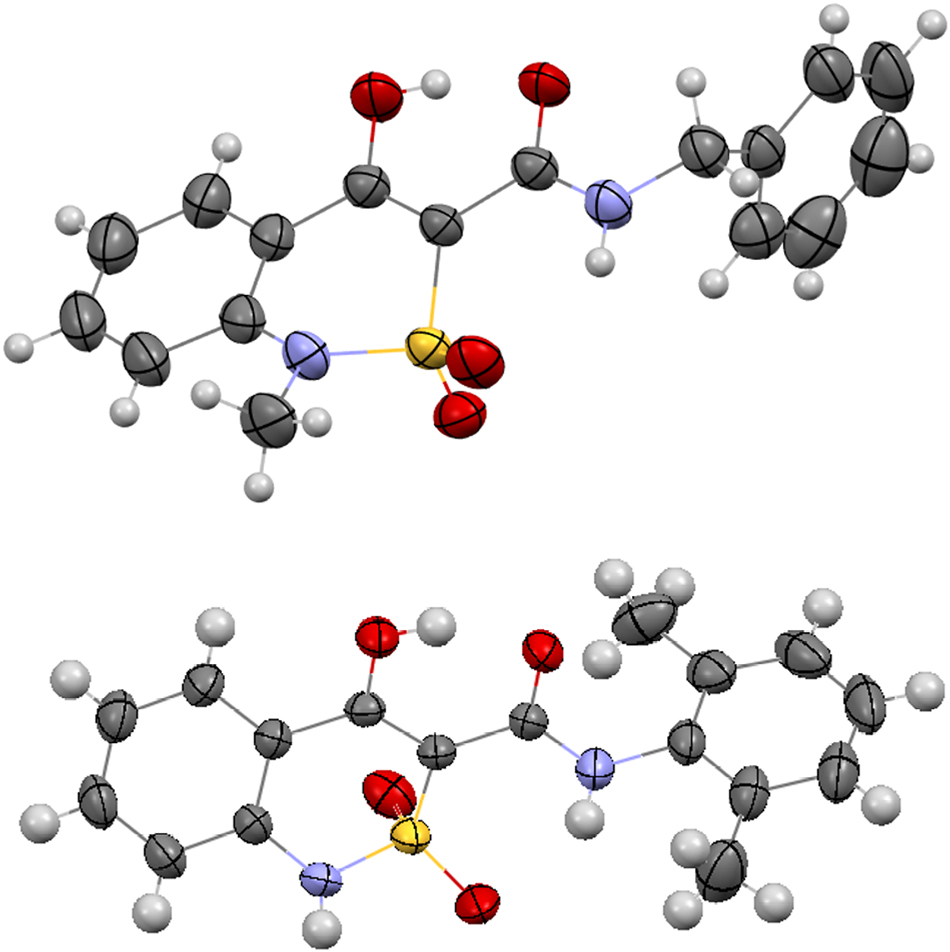

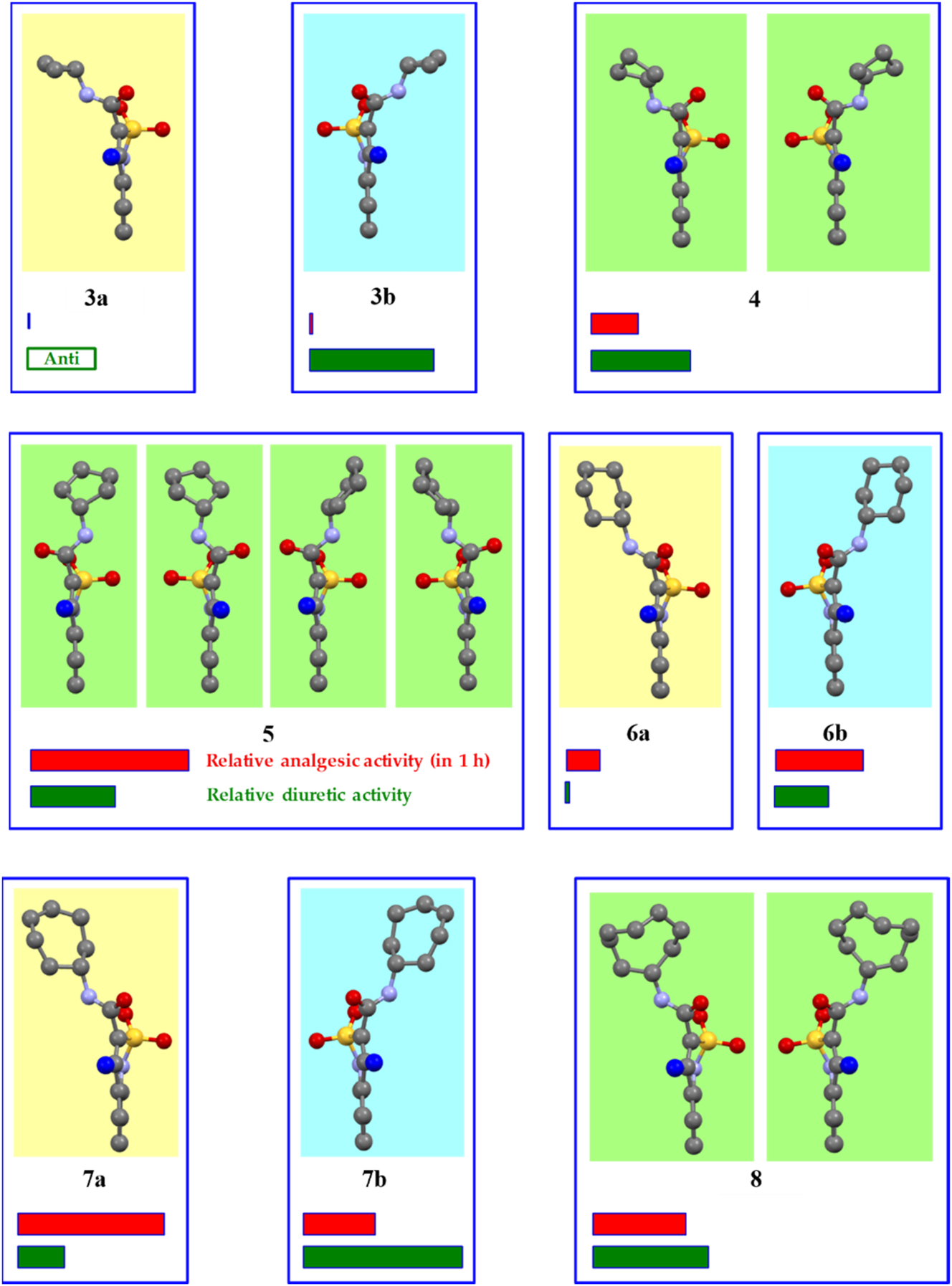

The cyclobutylamide 4 was found in the non-centrosymmetric space group R3c with two conformers symmetrical in relation to a plane present in the crystal phase (Figure 2). Cyclopentylamide 5 and cyclooctylamide 8 were crystallized in the centrosymmetric space group P21/c with two (structure 5) or one (structure 8) crystallographically independent molecules in the asymmetric part of the unit cell. As a result, four conformers of molecule 5 and two conformers of molecule 8 were found in the corresponding crystal structures (Figure 2).

Crystal forms of N-cycloalkyl-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamides 3–8 according to the X-ray diffraction data, their relative analgesic (red stripe) and diuretic (green stripe) activity. Conformations revealed in the same crystal are shown with the same background in one box. The atoms of different types are represented in different colors. The hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. The C-atom of the 4-methyl group faces the viewer and is highlighted blue for a better perception.

Cyclopropyl-, cyclohexyl- and cycloheptyl-amides were crystallized from the ethanol solution in the Sohncke space groups P21 (compound 3) or P212121 (compounds 6 and 7) revealing the property to form enantiopure crystals similar to N-R-4-hydroxy-2,2-dioxo-1Н-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamides, which were studied earlier. 16 , 17 The opposite enantiomophic crystal forms of compounds 3, 6 and 7 containing the mirrored conformers were obtained from the aqueous acetic acid.

Two mirrored conformations were signed as A and B according to a deviation of the sulfonyl group from the mean plane of the benzothiazine bicycle. This group deviates to the right in conformer A or to the left in conformer B if the benzothiazine fragment is positioned with the methyl group adjusted to the viewer (Figure 2). According to such a signing, cyclopropyl-3 and cycloheptyl-7 amides have the conformation A in the crystals 3a and 7a obtained from the ethanol solution while the cyclohexyl amide 6 was crystallized from the ethanol as conformer B (structure 6b). In accordance, the crystal structures 3b and 7b containing conformers B as well as the structure 6a containing the conformer A were crystallized from the aqueous acetic acid.

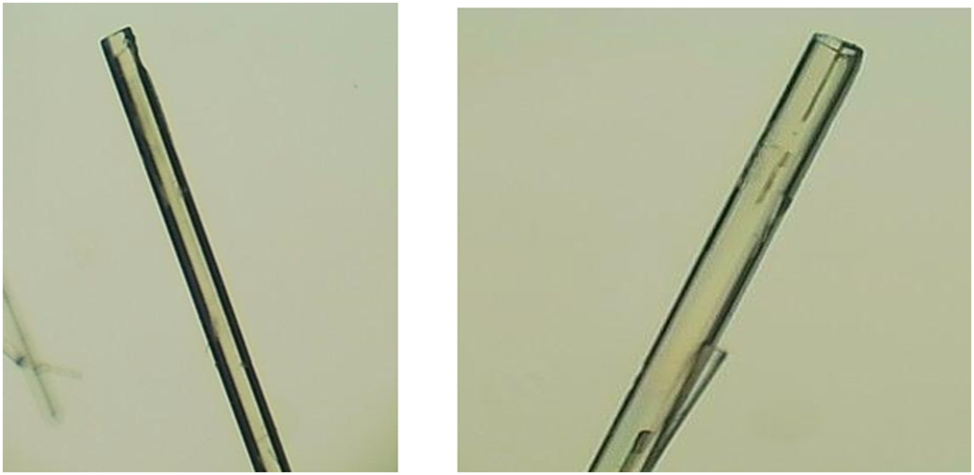

The two different enantiomorphic crystals of N-cycloheptyl-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamide have the same habit (Figure 3) and can’t be distinguished visually. Their NMR spectra and powder diffractograms are also the same. The enantiomorphic crystals have the same unit cell parameters (Table 1). Their absolute structures can be recognized only by the single crystal X-ray diffraction method using the so-called Flack parameter, which is calculated based on anomalous dispersion effect in the presence of heavy atoms to medium large atoms depending on the used X-ray radiation wavelength. 28 It should be noted that all the studied samples contain crystals of only one type. It was proved as a result of a large number of experiments with the crystals obtained from the same crystallization.

The crystals of N-cycloheptyl-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamide enantiomers 7a (on the left) and 7b (on the right).

The analysis of the molecular structures of the compounds 3–8 for all the studied crystals revealed that the dihydrothiazine ring adopts a conformation which is intermediate between a twist-boat and sofa according to Zefirov’s puckering parameters (Table 2). 29 The S1 and C8 atoms deviate by almost equal amounts but in opposite directions in relation to the planar part of the bicyclic fragment in enantiomorphic pairs 3a-3b, 6a-6b and 7a-7b. The crystals 4, 5 and 8 contain two mirrored conformers with significantly opposite deviations of the S1 and C8 atoms. The steric repulsion between the vicinal methyl group and the N-cycloalkylcarboxamide substituent results in the elongation of the C7–C8 endocyclic double bond (Table 2) as compared to its mean value 1.326 Å. 30 Another demonstration of this repulsion is also the significant rotation of the carbamide fragment in relation to the C7–C8 bond (the C7–C8–C9–O1 torsion angle in Table 2) despite the conjugation between π-orbitals. The rotation of the carbamide fragment causes the absence of any N–H⋯O intramolecular hydrogen bond, where one of the oxygen atoms of the sulfonyl group acts as hydrogen bond acceptor in all the studied crystals. So, the different of participation of the oxygen atoms of the sulfonyl group in intermolecular interactions can be the only reason of the S atom asymmetry in enantiopure crystals 3a-3b, 6a-6b, 7a-7b.

Selected geometric parameters for molecules 3–8 in the studied crystal forms.

| Structure | Molecule | Puckering parameters | Atom deviation, A˚ | Bond length, A˚ | Torsion angles, deg | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | Θ, deg | Ψ, deg | S1 | C8 | С7–С8 | С7–С8–С9–О1 | C9–N2–C11–H11 | ||

| 3a | 0.51 | 51.9 | 10.7 | 0.65 | 0.11 | 1.345(7) | 74.2(7) | 48 | |

| 3b | 0.51 | 51.9 | 12.2 | −0.66 | −0.12 | 1.361(6) | −75.4(5) | −48 | |

| 4 | 0.62 | 46.7 | 27.8 | ±0.82 | ±0.26 | 1.348(9) | −122.5(9) | −42 | |

| 5 | A | 0.56 | 51.6 | 22.5 | ±0.76 | ±0.22 | 1.346(4) | 64.0(4) | 24 |

| B | 0.51 | 50.5 | 23.2 | ±0.70 | ±0.20 | 1.348(4) | −60.3(4) | 51 | |

| 6a | 0.58 | 50.4 | 13.8 | 0.74 | 0.14 | 1.342(7) | 64.8(7) | 1 | |

| 6b | 0.58 | 48.6 | 12.8 | −0.74 | −0.13 | 1.344(9) | −62(1) | 0 | |

| 7a | 0.57 | 53.1 | 13.5 | 0.75 | 0.16 | 1.346(7) | 68.8(8) | −7 | |

| 7b | 0.55 | 55.4 | 13.6 | −0.74 | −0.16 | 1.325(9) | −71(1) | 8 | |

| 8 | 0.62 | 58.4 | 16.0 | ±0.86 | ±0.23 | 1.356(8) | 75.2(8) | −48 | |

Indeed, the two N–H⋯O intermolecular hydrogen bonds where the cyclic and carbamide amino groups are hydrogen bond donors and the carbonyl group oxygen atom and sulfonyl group oxygen atom act as hydrogen bond acceptors are revealed in all the studied crystals (Table 3). The geometric characteristics of these hydrogen bonds allows to consider them as medium to strong. However, these hydrogen bonds bind different fragments of neighboring molecules in different crystal structures (Table 3).

Geometric characteristics of the intermolecular hydrogen bonds in the studied crystals.

| Structure | Hydrogen bond | Symmetry operation | Geometrical characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H⋯A, Ǻ | D⋯A, Ǻ | D–H⋯A, deg | |||

| 3a | N1–H⋯O3 | x, y − 1, z | 2.00(7) | 2.849(6) | 175(6) |

| N2–H⋯O1 | x, y − 1, z | 2.11(5) | 2.958(6) | 174(5) | |

| 3b | N1–H⋯O2 | x, 1 + y, z | 1.93(8) | 2.865(5) | 174(7) |

| N2–H⋯O1 | x, 1 + y, z | 2.15(5) | 2.966(5) | 170(5) | |

| 4 | N1–H⋯O2 | 4/3 − y, 2/3 + x − y, z − 1/3 | 2.19(6) | 3.032(6) | 165(6) |

| N2–H⋯O1 | x, 1 + x − y, z − 1/2 | 2.21(7) | 3.003(8) | 174(8) | |

| 5 | N1A–H…O1A | x, 3/2 − y, 1/2 + z | 1.99(3) | 2.772(4) | 165(3) |

| N2A–H…O2A | −x, 2 − y, 1 − z | 2.25(3) | 3.030(3) | 161(3) | |

| N1B–H⋯O1B | x, 3/2 − y, 1/2 + z | 1.95(4) | 2.755(4) | 165(3) | |

| N2B–H⋯O2B | 1 − x, 1 − y, 2 − z | 2.24(3) | 3.029(3) | 165(3) | |

| 6a | N1–H⋯O3 | 1 + x, y, z | 2.13(4) | 2.879(5) | 164(4) |

| N2–H⋯O1 | 1 + x, y, z | 2.14(5) | 2.923(5) | 166(5) | |

| 6b | N1–H⋯O2 | 1 + x, y, z | 2.04(7) | 2.875(9) | 170(7) |

| N2–H⋯O1 | 1 + x, y, z | 2.09(8) | 2.914(9) | 158(7) | |

| 7a | N1–H⋯O3 | 1 + x, y, z | 2.03(5) | 2.909(7) | 170(5) |

| N2–H⋯O1 | 1 + x, y, z | 2.11(5) | 2.964(7) | 176(5) | |

| 7b | N1–H⋯O2 | 1 + x, y, z | 1.92(9) | 2.903(9) | 167(10) |

| N2–H⋯O1 | 1 + x, y, z | 2.11(9) | 2.971(9) | 175(9) | |

| 8 | N1–H⋯O1 | 1 − x, 1/2 + y, 3/2 − z | 1.85(8) | 2.711(6) | 171(8) |

| N2–H⋯O3 | 1 − x, 1/2 + y, 3/2 − z | 2.17(5) | 3.069(6) | 173(5) | |

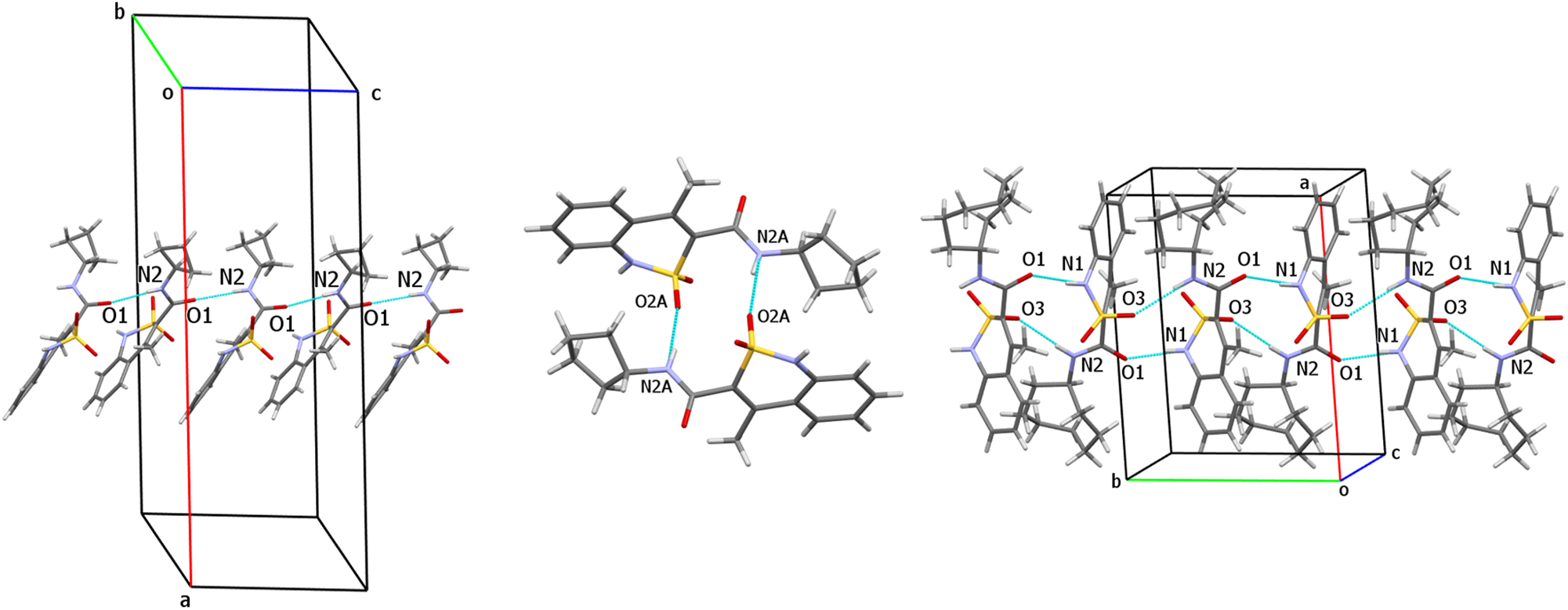

Thus, molecules of cyclobutylamide 4 form chains along the crystallographic c direction due to the N2–H⋯O1′ hydrogen bonds between carbamide fragments (Figure 4). The neighboring molecules within a chain have a “head-to-head” orientation and are slightly rotated to each other. The molecules belonging to neighboring chains are bound by the N1–H⋯O2′ hydrogen bonds.

Hydrogen bonded structural fragments in crystals 4 (on the left), 5 (in the middle) and 8 (on the right).

The N2–H⋯O2 hydrogen bonds between carbamide aminogroup and sulfonyl group oxygen atom form two types of centrosymmetric dimers (5A–5A and 5B–5B) in the crystal of cyclopentyl amide 5 (Figure 4). The dimers are bound by the almost linear N1–H⋯O1 hydrogen bonds between cyclic amino group and carbonyl group oxygen atom.

The molecules of cyclooctyl amide 8 form chains with a “head-to-tail” orientation of neighboring molecules (Figure 4) due to both intermolecular hydrogen bonds: N1–H⋯O1 (between cyclic amino group and carbonyl group oxygen atom) and N2–H⋯O3 (between carbamide amino group and sulfonyl group oxygen atom).

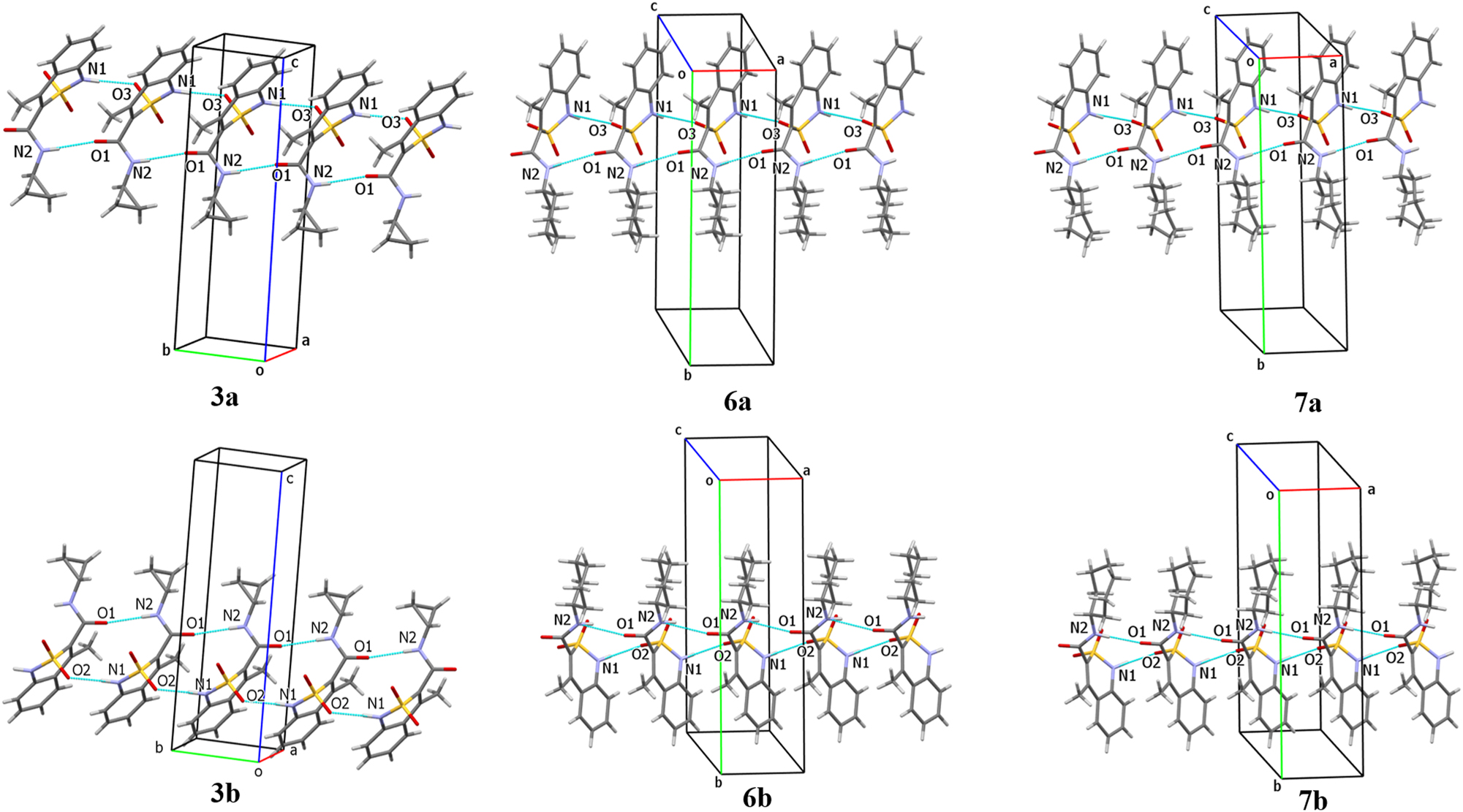

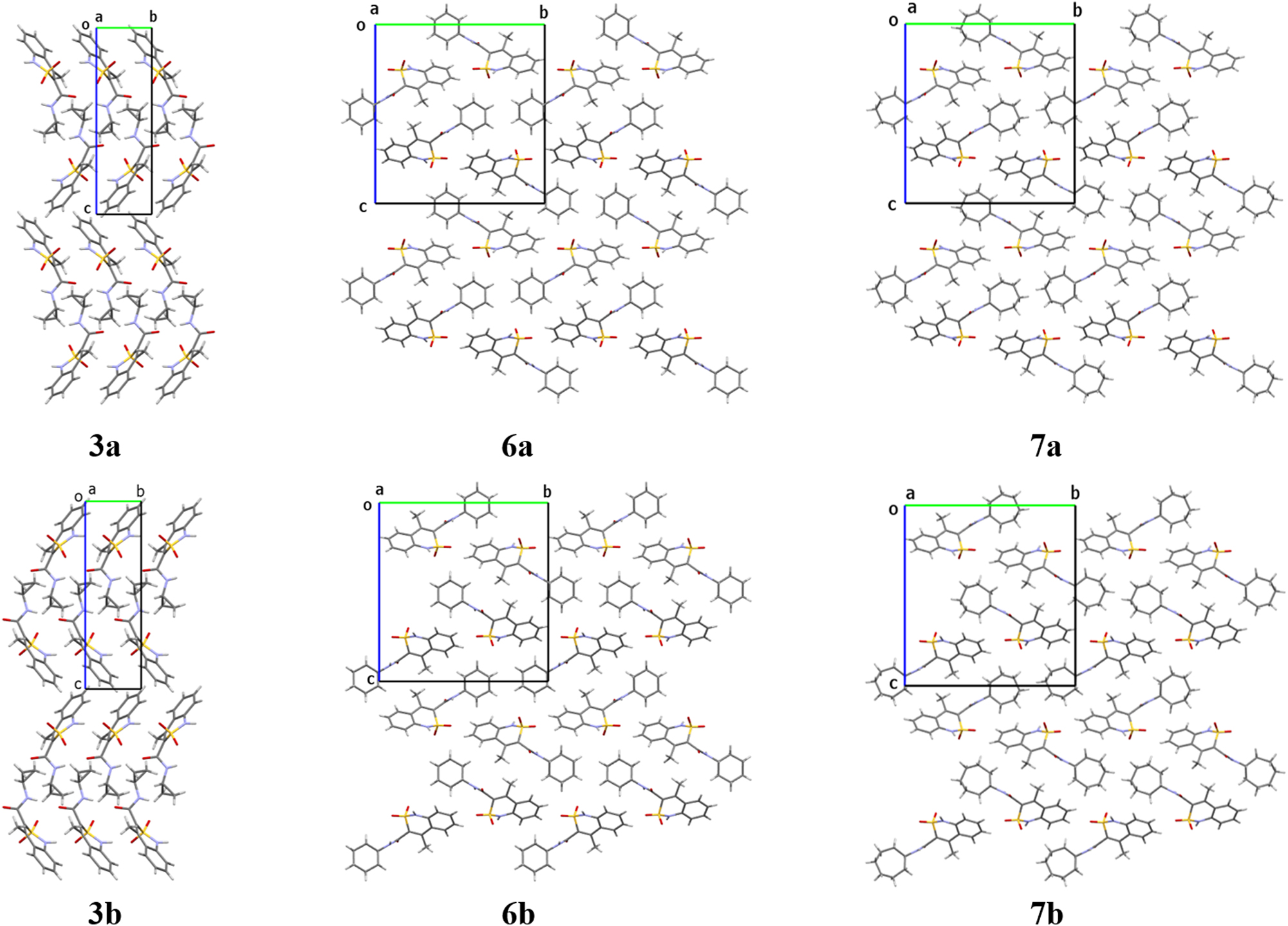

The crystal structures of enantiomorphic pairs 3, 6 and 7 are very similar (Figure 5). In all these crystals the molecules are oriented in a “head-to-head” mode and form well-ordered chains due to formation of both the N2–H⋯O1 hydrogen bond (the carbamide fragments of neighboring molecules act as hydrogen bond donor and hydrogen bond acceptor) and the N1–H⋯O3 hydrogen bond between cyclic amino group and the oxygen atom of the sulfonyl group.

Hydrogen bonded structural fragments in enantiomorphic crystals of compounds 3 (on the left), 6 (in the middle) and 7 (on the right).

The crystals of opposite enantiomers are mirrored to each other (Figure 6) and different oxygen atoms of the sulfonyl group participate in hydrogen bond formation in all the enantiomorphic pairs. It should be also noted that crystals of the cyclohexyl amide 6 and cycloheptyl amide 7 are homeotypic (Figure 6). They have very similar unit cell parameters (Table 1) and the hydrogen bonded structural fragments of a crystal packing (Figure 5).

Crystal packing of the enantiomorphic structures 3a-3b, 6a-6b, 7a-7b. Projection along the crystallographic a direction.

As mentioned above, N-R-4-hydroxy-2,2-dioxo-1Н-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamides can exhibit analgesic, anti-inflammatory or diuretic activities. 18 , 19 , 20 Therefore, activities of two types were studied for all the crystal forms of the compounds 3–8.

The analgesic properties of all the studied crystals were compared with Meloxicam (systematic name is 4-hydroxy-2-methyl-N-(5-methyl-2-thiazolyl)-2H-1,2-benzothiazine-3-carboxamide-1,1-dioxide) as the reference drug (Table 4). The racemic crystals 5 possess the strongest analgesic activity. It should be noted that all the conformers revealed in this crystal structure differ from molecules 3, 4 and 6–8 by the deviation of the sulfur atom and orientation of the carbonyl group in different directions in relation to planar part of the bicyclic fragment (Figure 2). Another possible reason of higher analgesic activity may be some peculiarities of crystal destruction caused by the presence of strongly bound centrosymmetric dimers, which are linked by weaker linear hydrogen bond. Thus, crystal structure 5 differs from all other studied ones by both molecular and crystal structures. Analgesic activity of cyclopentylamide 5 achieved the highest value by the first hour of the experiment (Table 4). Then the influence of cyclopentylamide begins to decline. This fact may indicate a relatively short biological half-life of the substance and a relatively low degree of binding to plasma proteins. Based on the above data, cyclopentylamide 5 can be recommended for the relief of acute pain syndrome of traumatic origin. Cyclooctylamide 8 is noticeably weaker as compared to cyclopentylamide 5 but the analgesic properties of 8 are similar to well-known reference drug Meloxicam (Table 4) and even stronger in the first hour. The racemic crystal form of the cyclobutylamide 4 possesses twice as weaker analgesic activity than the cyclooctylamide 8.

The analgesic activity of cycloalkylamides 3–8, and meloxicam on the “hot plate” model in rats.

| Entry | Product | Latent period | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial level (s) | In 1 h | In 1.5 h | In 2 h | |||||

| (s) | (%) | (s) | (%) | (s) | (%) | |||

| 1 | 3a | 6.37 ± 0.73 | 6.48 ± 0.60a | 1.7 | 6.42 ± 0.53a | 0.8 | 6.38 ± 0.42a | 0.2 |

| 2 | 3b | 5.56 ± 0.78 | 5.75 ± 0.62a | 3.4 | 5.80 ± 0.51a | 4.3 | 5.58 ± 0.45a | 0.3 |

| 3 | 4 | 5.72 ± 0.66 | 7.10 ± 0.41a | 24.1 | 7.32 ± 0.33a | 28.0 | 7.16 ± 0.38a | 25.2 |

| 4 | 5 | 6.04 ± 0.92 | 13.21 ± 0.95a | 118.5 | 11.62 ± 0.46a | 92.1 | 9.12 ± 0.98a | 50.9 |

| 5 | 6a | 5.60 ± 0.98 | 6.30 ± 0.52a | 12.5 | 6.72 ± 0.74a | 20.0 | 6.54 ± 0.59a | 16.7 |

| 6 | 6b | 5.86 ± 0.44 | 7.72 ± 0.49a | 31.7 | 8.88 ± 0.42a | 51.5 | 8.02 ± 0.21a | 36.9 |

| 7 | 7a | 5.82 ± 0.58 | 10.38 ± 0.59a | 78.4 | 10.74 ± 0.48a | 84.5 | 8.76 ± 0.36a | 50.5 |

| 8 | 7-B | 5.84 ± 0.90 | 7.64 ± 0.28a | 30.8 | 8.24 ± 0.75a | 41.1 | 7.98 ± 0.78a | 36.6 |

| 9 | 8 | 5.68 ± 0.77 | 8.36 ± 0.47a | 47.2 | 8.74 ± 0.17a | 53.9 | 8.00 ± 0.36a | 40.8 |

| 10 | Meloxicam | 6.26 ± 0.61 | 8.44 ± 0.49a | 34.8 | 9.62 ± 0.41a | 53.7 | 9.20 ± 0.40a | 46.9 |

-

aDifferences statistically significant for p ≤ 0.05 versus the initial level.

Taking into account our previous study, the enantiomorphic pairs of the compounds 3, 6 and 7 seem to be of the most interest as biologically active substances. Surprisingly, it was revealed that both enantiomorphic crystal forms of N-cyclopropyl-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamide 3 do not possess analgesic activity at all (Table 4). But the enantiomorphic crystal forms of cyclohexylamide 6 and cycloheptylamide 7 appeared to be effective enough in pain suppression with significant differences between mirrored enantiomers. Thus, 6b exhibits a much stronger analgesic activity than the enantiomeric form 6a. Per os administering of 6b results in sharp bouncing of all experimental animals due to reaction to a thermal pain stimulus. That indicates a significant suppression of peripheral pain signal transmission mechanisms alongside with almost no effect on supraspinal mechanisms of pain innervation. For this reason, enantiomeric crystal form 6b is suitable for the relief of pain syndromes of various etiologies excepting rheumatoid and polyneuritis. The enantiomers 7a and 7b act in a different way. The crystal form 7a appeared to be much more active than the opposite enantiomeric form. Enantiomer 7a inhibits the pain response even more effectively than cyclohexylamide 6b or Meloxicam and is similar to the racemic cyclopentylamide 5 in terms of the therapeutic influence on the studied animals.

In general, the analysis of the analgesic activity of all the studied crystal forms did not reveal definite correlation with their molecular and crystal structures.

In contrast to analgesic effect, the influence of enantiomorphic forms of compounds 3, 6 and 7 on the urinary function of the kidneys seems to represent clear structural-biological correlation. In all the cases enantiomeric form B is much stronger than the mirror form A in terms of the exerted diuretic effect (Table 5). The racemic crystals of 4, 5 and 8 are more active as compared to reference drug Hydrochlorothiazide (systematic name is 6-chloro-3,4-dihydro-2H-1,2,4-benzothiadiazine-7-sulfonamide-1,1-dioxide). The activity level of the racemic crystal forms correlates to the size of cycloalkyl fragments (Table 5). It should be noted that the reference drug Hydrochlorothiazide was used as racemic crystal form. Unfortunately, two enantiomorphic forms obtained from the same alcohol solution were not separated as pure enantiomorphs and tested on the biological activity.

The diuretic activity of cycloalkylamides 3–8, and Hydrochlorothiazide.

| Entry | Product | Diuresis in 4 h | |

|---|---|---|---|

| mla | %b | ||

| 1 | 3a | 1.25 ± 0.11a | −86 |

| 2 | 3b | 13.49 ± 2.42a | +158 |

| 3 | 4 | 8.89 ± 1.76a | +70 |

| 4 | 5 | 8.99 ± 1.87a | +72 |

| 5 | 6a | 5.54 ± 0.30a | +6 |

| 6 | 6b | 8.78 ± 1.03a | +68 |

| 7 | 7a | 8.16 ± 0.92a | +56 |

| 8 | 7b | 15.58 ± 2.54a | +198 |

| 9 | 8 | 12.76 ± 1.85a | +144 |

| 10 | Hydrochlorothiazide | 8.21 ± 0.20a | +57 |

| 11 | Control | 5.23 ± 0.21 | – |

-

aDifferences statistically significant for p ≤ 0.05 versus control. b“+” Indicates increase and “–” inhibition of diuresis when compared with the control taken as 100 %.

5 Conclusions

The studied N-cycloalkyl-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamides (cycloalkyl moiety = cyclopropyl, cyclobutyl, cyclopentyl, cyclohexyl, cycloheptyl, cyclooctyl) are not chiral molecules, but they can crystalize as a true racemic form as well as an enantiomorphic crystal pairs. The racemic crystals contain molecules of two conformation types, which are symmetric to each other with respect to an inversion center or a mirror plane. The appropriate choice of a solvent and crystallization conditions allows to obtain pure enantiomeric crystals containing molecules of one conformational type only. Enantiomorphic crystal pairs differ in the type of molecule conformations found in them. Being enantiomeric, such crystals have the same unit cell parameters and can be recognized only using the single crystal X-ray diffraction study due to anomalous dispersion. We were able to show that it is the most plausible that the ability of 1,2-benzothiazines to form chiral crystals is caused by the fact that two oxygen atoms of the sulfonyl group are non-equivalent in their hydrogen bonds formation ability. Such a non-equivalence of formally equal oxygen atoms results in a asymmetry of the sulfur atom. Thus, the formation of intermolecular interactions turns the sulfur atom into a stereogenic center.

Similar to chiral molecules, the enantiomorphic crystals revealed a significant difference in their biological properties. Our study showed that the analgesic activity is independent on the molecular or crystal structure. In contrary, the diuretic activity proved to depend on the size of the cycloalkyl substituent in the case of racemic crystal forms. In all the enantiomorphic pairs, the crystals containing conformer B have a much stronger diuretic effect as compared to the crystals containing the mirrored conformer A. Thus, knowledge of the exact crystal form proves to be of a great importance for all developments and improvements of drugs that contain the sulfonyl group.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: S.V. Shishkina: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft. I.V. Ukrainets: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft. I.S. Konovalova: Investigation, Visualization. G.J. Reiss: Writing – review & editing. N.I. Voloshchuk: Investigation, Formal analysis.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Data will be made available on request.

References

1. Bernstein, J. Polymorphism in Molecular Crystals; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2007.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199236565.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

2. Aitipamula, S. Polymorphism in Molecular Crystals and Cocrystals. In Advances in Organic Crystal Chemistry; Tamura, R.; Miyata, M., Eds.; Springer: Tokyo, 2015.10.1007/978-4-431-55555-1_14Suche in Google Scholar

3. McCrone, W. C. Polymorphism. In Physics and Chemistry of the Organic Solid State; Fox, D.; Labes, M. M.; Weissberger, A., Eds.; Interscience: London, Vol. 2, 1965; p. 725.Suche in Google Scholar

4. Brittain, H. G. Polymorphism in Pharmaceutical Solids; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2009.Suche in Google Scholar

5. Hilfiker, F. Polymorphism in the Pharmaceutical Industry; John Wiley & Sons: Weinheim, 2006.10.1002/3527607889Suche in Google Scholar

6. Morissette, S. L.; Almarsson, Ö.; Peterson, M. L.; Remenar, J. F.; Read, M. J.; Lemmo, A. V.; Ellis, S.; Cima, M. J.; Gardner, C. R. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2004, 56, 275.Suche in Google Scholar

7. Bauer, M. Ann. Pharm. Fr. 2002, 60 (3), 152.10.1301/00296640260093832Suche in Google Scholar

8. Almarsson, Ö.; Zaworotko, M. J. Chem. Commun. 2004, 17, 1889; https://doi.org/10.1039/b402150a.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Raza, K.; Kumar, P.; Ratan, S.; Malik, R.; Arora, S. SOJ Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 1, 10.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Oganov, A. R. Modern Methods of Crystal Structure Prediction; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2011.10.1002/9783527632831Suche in Google Scholar

11. Neumann, M. A.; Leusen, F. J. J.; Kendrick, J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 2427; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.200704247.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. LeBlanc, L. M.; Otero-de-la-Roza, A.; Johnson, E. R. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2018, 14 (4), 2265; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jctc.7b01179.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Price, S. L. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 15, 1996.10.1039/b719351cSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Leech, C. K.; Fabbiani, F. P. A.; Shankland, K.; David, W. I. F.; Ibberson, R. Acta Crystallogr. 2008, B64, 101.10.1107/S010876810705687XSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Thomas, S. P.; Grosjean, A.; Flematti, G. R.; Karton, A.; Sobolev, A. N.; Edwards, A. J.; Piltz, R. O.; Iversen, B. B.; Koutsantonis, G. A.; Spackman, M. A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 10255; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201905085.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Ukrainets, I. V.; Shishkina, S. V.; Baumer, V. N.; Gorokhova, O. V.; Petrushova, L. A.; Sim, G. Acta Cryst. 2016, C72, 411.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Shishkina, S. V.; Ukrainets, I. V.; Vashchenko, O. V.; Voloshchuk, N. I.; Bondarenko, P. S.; Petrushova, L. A.; Sim, G. Acta Crystallogr. 2020, C76, 69.Suche in Google Scholar

18. Ukrainets, I. V.; Petrushova, L. A.; Sidorenko, L. V.; Davidenko, A. A.; Duchenko, M. A. Sci. Pharm. 2016, 84, 497; https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm84030497.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Ukrainets, I. V.; Burian, A. A.; Baumer, V. N.; Shishkina, S. V.; Sidorenko, L. V.; Tugaibei, I. A.; Voloshchuk, N. I.; Bondarenko, P. S. Sci. Pharm. 2018, 86, 21; https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm86020021.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Ukrainets, I. V.; Hamza, G. M.; Burian, A. A.; Shishkina, S. V.; Voloshchuk, N. I.; Malchenko, O. V. Sci. Pharm. 2018, 86, 9; https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm86010009.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Günther, H. NMR Spectroscopy: Basic Principles, Concepts and Applications in Chemistry; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2013; p. 113.Suche in Google Scholar

22. Ukrainets, I. V.; Hamza, G. M.; Burian, A. A.; Voloshchuk, N. I.; Malchenko, O. V.; Shishkina, S. V.; Grinevich, L. A.; Grynenko, V. V.; Sim, G. Sci. Pharm. 2018, 86, 50; https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm86040050.Suche in Google Scholar

23. Sheldrick, G. M. Acta Cryst. 2008, A64, 112.10.1107/S0108767307043930Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Vogel, H. G. Drug Discovery and Evaluation: Pharmacological Assays; Springer: Berlin, 2008; p. 983.Suche in Google Scholar

25. Vogel, H. G. Drug Discovery and Evaluation: Pharmacological Assays; Springer: Berlin, 2008; p. 459.10.1007/978-3-540-70995-4Suche in Google Scholar

26. Ukrainets, I. V.; Burian, A. A.; Hamza, G. M.; Voloshchuk, N. I.; Malchenko, O. V.; Shishkina, S. V.; Sidorenko, L. V.; Burian, K. O.; Sim, G. Sci. Pharm. 2019, 87, 12; https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm87020012.Suche in Google Scholar

27. Ukrainets, I. V.; Hamza, G. M.; Burian, A. A.; Voloshchuk, N. I.; Malchenko, O. V.; Shishkina, S. V.; Danilova, I. A.; Sim, G. Sci. Pharm. 2019, 87, 10; https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm87020010.Suche in Google Scholar

28. Parson, S.; Flack, H. D.; Wagner, T. Acta Crystallogr. 2013, B69, 249.10.1107/S2052519213010014Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Zefirov, N. S.; Palyulin, V. A.; Dashevskaya, E. E. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 1990, 3 (3), 147; https://doi.org/10.1002/poc.610030304.Suche in Google Scholar

30. Orpen, A. G.; Brammer, L.; Allen, F. H.; Kennard, O.; Watson, D. G.; Taylor, R.; Bürgi, H.-B.; Dunitz, J. D., Eds. Structure Correlation; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 1994; p. 767.Suche in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/zkri-2025-0005).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Obituary

- Obituary for Hartmut Bärnighausen

- Micro Review

- Bismuth as reactive and non-reactive flux medium for the synthesis and crystal growth of intermetallics

- Organic and Metalorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Racemic and unusual enantiomeric crystal forms of N-cycloalkyl-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamides and their biological activity

- Inorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Lead phosphate oxyapatite, Pb10(PO4)6O, with c-double superstructure

- A novel microporous uranyl silicate prepared by high temperature flux technique

- The Grubbs catalyst – dichlorido(1-(2,6-diethylphenyl)-3,5,5-trimethyl-3-phenylpyrrolidin-2-ylidene)-({5-nitro-2-[(propan-2-yl)oxy]phenyl}methylidene)ruthenium(II) – some observations on the crystallography and stereochemistry of a racemic mimic pair

- Thermal decomposition of copper(II) hydroxide and hydroxocarbonates according to X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy in operando

- New calcium perrhenates: synthesis and crystal structures of Ca(ReO4)2 and K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Obituary

- Obituary for Hartmut Bärnighausen

- Micro Review

- Bismuth as reactive and non-reactive flux medium for the synthesis and crystal growth of intermetallics

- Organic and Metalorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Racemic and unusual enantiomeric crystal forms of N-cycloalkyl-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamides and their biological activity

- Inorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Lead phosphate oxyapatite, Pb10(PO4)6O, with c-double superstructure

- A novel microporous uranyl silicate prepared by high temperature flux technique

- The Grubbs catalyst – dichlorido(1-(2,6-diethylphenyl)-3,5,5-trimethyl-3-phenylpyrrolidin-2-ylidene)-({5-nitro-2-[(propan-2-yl)oxy]phenyl}methylidene)ruthenium(II) – some observations on the crystallography and stereochemistry of a racemic mimic pair

- Thermal decomposition of copper(II) hydroxide and hydroxocarbonates according to X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy in operando

- New calcium perrhenates: synthesis and crystal structures of Ca(ReO4)2 and K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O