Abstract

Single crystals of two new calcium perrhenates, anhydrous Ca(ReO4)2 (1) and K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O (2), were prepared during solid-state and solution attempts to prepare the potassium analog of NaCa(ReO4)3. Both structures can be regarded as frameworks comprised of vertex-sharing CaO8 and ReO4 polyhedra. 1 is a complete structural analog of Sr(ReO4)2 while 2 corresponds to its own structure type. It is also the first hydrated binary perrhenate to date. We discuss the similarities and differences in the structures of alkaline earth perrhenates and pertechnetates; existence of more complex and elegant metal-perrhenate architectures is predicted.

1 Introduction

The interest to the compounds of rhenium has a complex background: they serve as model non-radioactive systems for further targeting compounds of technetium, 1 , 2 are involved in the separation of rhenium per se; 3 , 4 in addition, these are relatively sparsely studied and remain a “blank spot” when analyzing general trends in the chemistry of transition metals, particularly in higher oxidation states. For instance, inorganic perrhenates exhibit essential structural similarities evidently to pertechnates, but also to chromates, molybdates, sometimes tungstates and perruthenates; less common are analogies to sulfates, selenates, perchlorates, etc. This mostly concerns the compounds of simple compositions, e.g. those corresponding to the scheelite or barite structures – which, amongst perrhenates, are adopted by compounds of univalent cations like alkali, thallium (I), and silver. Essentially less is known about double perrhenates or compounds of higher-valence cations. For instance, a small series of trigonal MIMII(ReO4)3 compounds (MI = Na, K, Ag; MII = Ca, Sr, Pb) 5 , 6 adopt the structure also observed for CdTh(MoO4)3 7 and (Cu,Mn)U(MoO4)3; 8 yet, not all combinations of MI and MII are possible. Just a single pertechnetate representative, NaCa(TcO4)3, is also known. 9 Several cation-deficient representatives, MILn(ReO4)4 (MI = Na, Ag), 10 , 11 as well as a single alumohydride, LiCa(AlH4)3, 12 have also been reported for the trigonal structure type. Among others, dihydrates of Sr(ReO4)2, 13 Pb(TcO4)2, and Pb(ReO4)2 9 were reported to be isostructural yet the data for the latter are missing. Among perrhenates of alkaline earths, just a few compounds have been structurally characterized: Ca(ReO4)2·2H2O, 14 Sr(ReO4)2·2H2O, 13 Ba(ReO4)2·H2O, 15 and Ba(ReO4)2·4H2O, 16 as well as a single anhydrous compound Sr(ReO4)2. 17 , 18

As we reported in 5 , attempts to prepare KCa(ReO4)3 via solution and high-temperature approaches were not successful. However, these preparations resulted in formation of some new calcium perrhenates. Hereby we report the preparation and structural features of two new compounds, Ca(ReO4)2 (1) and K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O (2), obtained via these synthesis techniques.

2 Preparation of single crystals of Ca(ReO4)2 and K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O

The KReO4, Ca(ReO4)2 and Ba(ReO4)2 precursors were obtained during reaction of HReO4 (prepared from 99.97 % Re powder and hydrogen peroxide) and analytically pure K, Ca, and Ca carbonates. KReO4 was dried in air while Ca(ReO4)2·2H2O and Ba(ReO4)2·4H2O were slowly heated to 140 °C and kept at this temperature for several hours. At higher temperatures, the color of the off-while powders thus obtained changes to yellow of gray which indicates loss or reduction of small amounts of rhenium and should be avoided.

Strongly hygroscopic single crystals of Ca(ReO4)2 were obtained during the search for new CaTh(MoO4)2-like perrhenates. In the solid-state experiments, 1 mmol KReO4 and 1 mmol dehydrated Ca(ReO4)2 or Ba(ReO4)2, respectively, were placed into silica-jacketed alumina crucibles, rapidly ground, evacuated to 30 mTorr (ca. 4 Pa), sealed, and annealed in a programmable furnace to 560–750 °C with slow cooling (within 50 h) to room temperature. Single crystals could be picked out of the solidified melt which were identified as KReO4 and anhydrous Ca(ReO4)2 (1). Formation of ternary perrhenates was observed indicating that no reaction took place and the system is probably eutectic. In the case of Ba-containing sample, good quality crystals were not formed. Attempts to crystallize pure dehydrated Ca(ReO4)2 and Ba(ReO4)2 in the same manner were not successful. The samples turned dark due to partial reduction of ReVII, and the quality of crystals was too low for structural studies.

In the wet approach, an aqueous solution containing 2 mmol KReO4 and 2 mmol Ca(ReO4)2 was evaporated on a hotplate until ca. 80 % of water was removed and a thick polycrystalline crust was formed. It was broken and the crystals separated from the slurry by vacuum filtration. Upon searching the polycrystalline sample, a crystal with relatively large cell dimensions was picked out (2). Subsequent structure determination (vide infra) revealed a rather complex calcium perrhenate framework containing large voids which were assumed to contain disordered potassium cations.

In both cases, the crystals were picked out of multiphase polycrystalline samples. Therefore, herein we restrict ourselves to the discussion and comparisons of the crystal structures of the new compounds.

3 Single-crystal X-ray experiments

Single crystals of studied compounds selected for X-ray diffraction analysis were glued onto glass filaments and arranged in a Rigaku XtaLAB Synergy-S diffractometer equipped with a PhotonJet-S detector operating with MoKα radiation at 50 kV and 1 mA. A single crystal of each compound was chosen and more than a hemisphere of data collected with a frame width of 0.5° in ω, and 10–50 s spent counting for each frame. The data were integrated and corrected for absorption applying a multiscan type model using the Rigaku Oxford Diffraction programs CrysAlis Pro. The unit cell parameters were calculated by the least-squares method. The cell metrics indicated close similarity to the low-tempertaure poymorph of Sr(ReO4)2; hence, the initial atomic coordinates from 17 were used to refine the structure of 1. The structure of 2 was solved by direct methods. The parameters of the X-ray diffraction experiment and structure refinement are given in Table 1. The final model of compounds selected includes the coordinates and anisotropic thermal parameters of atoms. Selected interatomic distances are collected in Tables 2 and 3. Bond valence sums for K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O (Table 4) were calculated using the parameters from Ref. 19].

Crystallographic data and refinement parameters for Ca(ReO4)2 and K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O.

| Ca(ReO4)2 | K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O | |

| Crystal data: | ||

| Temperature (K) | 293 | 100 |

| Radiation | MoKα | MoKα |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic | Tetragonal |

| Space group | P21/n | P4/ncc |

| a (Å) | 6.0874(3) | 12.7047(2) |

| b (Å) | 9.8178(5) | |

| c (Å) | 12.3120(6) | 21.5501(7) |

| β (°) | 95.343(4) | |

| V (Å3) | 732.63(6) | 3,478.39(16) |

| Z | 4 | 4 |

| D calc (g/cm3) | 4.900 | 4.325 |

| μ (mm−1) | 33.714 | 28.512 |

|

|

||

| Data collection: | ||

|

|

||

| θ Range (°) | 3.324–27.998 | 3.709–27.995 |

| h, k, l ranges | −7 → 8, −12 → 10, −16 → 16 | −14 → 11, −16 → 13, −25 → 28 |

| Total reflections collected | 7,809 | 15,719 |

| Unique reflections (R int ) | 1,619 (0.0494) | 2,005 (0.0304) |

|

|

||

| Structure refinement: | ||

|

|

||

| Weighting scheme a, b | 0.0409, 62.7534 | 0.0, 73.2729 |

| R 1[F > 4σF], wR 1[F > 4σF] | 0.0450, 0.1175 | 0.0277, 0.0546 |

| R all , wR all | 0.0482, 0.1187 | 0.0300, 0.0552 |

| Goodness-of-fit | 1.143 | 1.268 |

| CCDC | 2415241 | 2415242 |

Selected interatomic distances (Å) in Ca(ReO4)2.

| Ca1–O7 | 2.351(12) | Re1–O2 | 1.704(13) |

| Ca1–O2 | 2.373(14) | Re1–O3 | 1.707(12) |

| Ca1–O1 | 2.401(14) | Re1–O4 | 1.720(12) |

| Ca1–O3 | 2.407(12) | Re1–O1 | 1.724(13) |

| Ca1–O4 | 2.423(12) | <Re1–O> | 1.714 |

| Ca1–O5 | 2.430(14) | ||

| Ca1–O6 | 2.457(14) | Re2–O8 | 1.715(13) |

| Ca1–O8 | 2.758(14) | Re2–O5 | 1.722(14) |

| <Ca1–O> | 2.450 | Re2–O6 | 1.729(13) |

| Re2–O7 | 1.739(12) | ||

| <Re2–O> | 1.726 |

Selected interatomic distances (Å) in K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O.

| K1A–O6 | 2.86(2) | Ca1–Ow1 | 2.395(5) | × 4 | Re1–O8 | 1.702(7) |

| K1A–Ow1 | 2.99(2) | Ca1–O4 | 2.488(5) | × 4 | Re1–O6 | 1.717(6) |

| K1A–O8 | 3.07(2) | <Ca1–O> | 2.442 | Re1–O2 | 1.723(5) | |

| K1A–O4 | 3.16(2) | Re1–O3 | 1.733(5) | |||

| K1A–Ow1 | 3.36(2) | Ca2–O2 | 2.430(6) | × 4 | <Re1–O> | 1.719 |

| K1A–O6 | 3.47(2) | Ca2–O5 | 2.460(7) | × 4 | ||

| <K1A–O> | 3.15 | <Ca2–O> | 2.445 | Re2–O7Aa | 1.657(10) | |

| Re2–O7Bb | 1.843(10) | |||||

| K1B–O8 | 2.69(1) | Ca3–O7Aa | 2.383(10) | × 4 | Re2–O5 | 1.709(7) |

| K1B–O6 | 2.88(1) | Ca3–O3 | 2.434(6) | × 4 | Re2–O4 | 1.710(6) |

| K1B–O8 | 3.13(1) | Ca3–O7Ba | 2.457(11) | × 4 | Re2–O1 | 1.717(6) |

| K1B–O5 | 3.21(1) | <Ca3–O> | 2.425 | <Re2–O> | 1.727 | |

| K1B–O2 | 3.23(1) | |||||

| K1B–O4 | 3.35(1) | |||||

| K1B–O6 | 3.39(1) | |||||

| <K1B–O> | 3.13 |

-

aO7A s.o.f. = 0.5; bO7B s.o.f. = 0.5.

Bond-valence values (in vu) in the crystal structure of K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O.

| O1 | O2 | O3 | O4 | O5 | O6 | O7A s.o.f. = 0.5 |

O7B s.o.f. = 0.5 |

O8 | Ow1 | ∑ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca1 | 0.24 × 4→ | 0.30 × 4→ | 2.16 | ||||||||

| Ca2 | 0.28 × 4→ | 0.26 × 4→ | 2.16 | ||||||||

| Ca3 | 0.28 × 4→ | 0.16 × 4→ 0.31 × 4↓ |

0.13 × 4→ 0.26 × 4↓ |

2.28 | |||||||

| Re1 | 1.73 | 1.69 | 1.73 | 1.82 | 6.97 | ||||||

| Re2 | 1.73 | 1.78 | 1.78 | 1.01 | 0.65 | 6.95 | |||||

| K1A s.o.f. = 0.2 |

0.06→ 0.01↓ |

0.13→ 0.03→ 0.03↓ 0.01↓ |

0.08→ 0.02↓ |

0.09→ 0.04→ 0.02↓ 0.01↓ |

0.43 | ||||||

| K1B s.o.f. = 0.3 |

0.05→ 0.02↓ |

0.04→ 0.01↓ |

0.05→ 0.02↓ |

0.12→ 0.03→ 0.04↓ 0.01↓ |

0.19→ 0.07→ 0.06↓ 0.02↓ |

0.55 | |||||

| ∑ | 1.73 | 2.03 | 1.97 | 2.04 | 2.06 | 1.82 | 2.25 | 1.69 | 1.92 | 0.33 |

4 Elemental analysis

Qualitative electron microprobe analysis of two compounds reported herein (LINK AN-10000 EDS system) revealed no other elements, except Ca and Re in Ca(ReO4)2 and K, Ca and Re in K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O with atomic number greater than 11 (Na).

5 Results

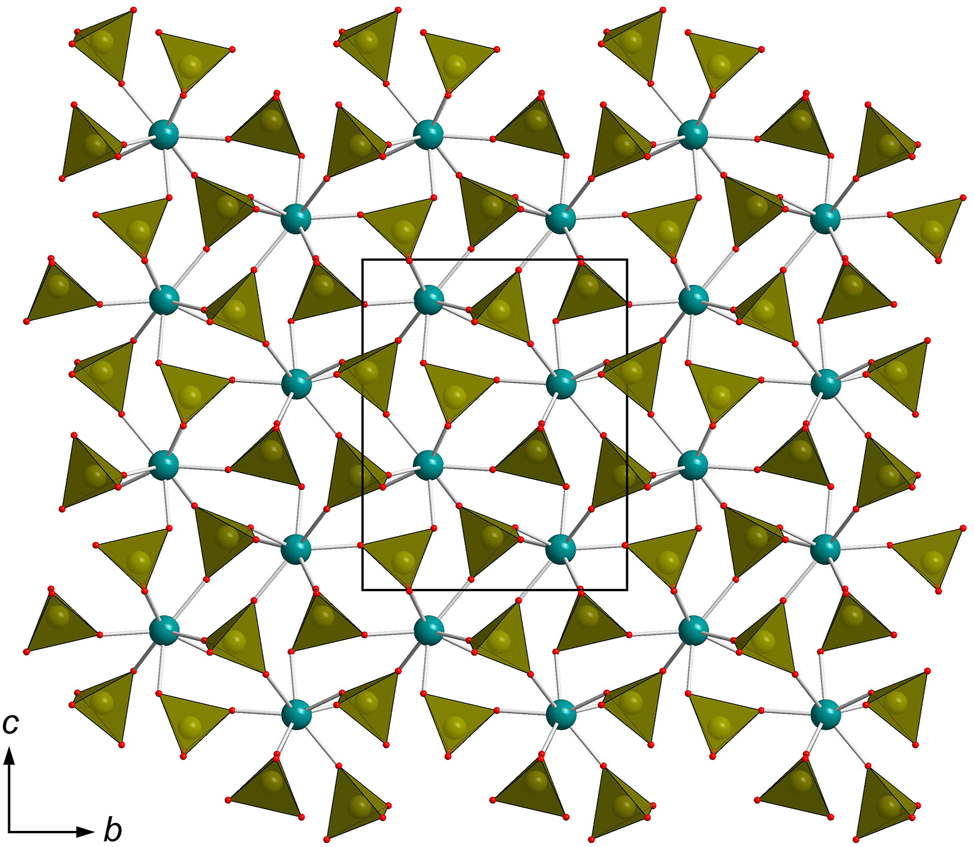

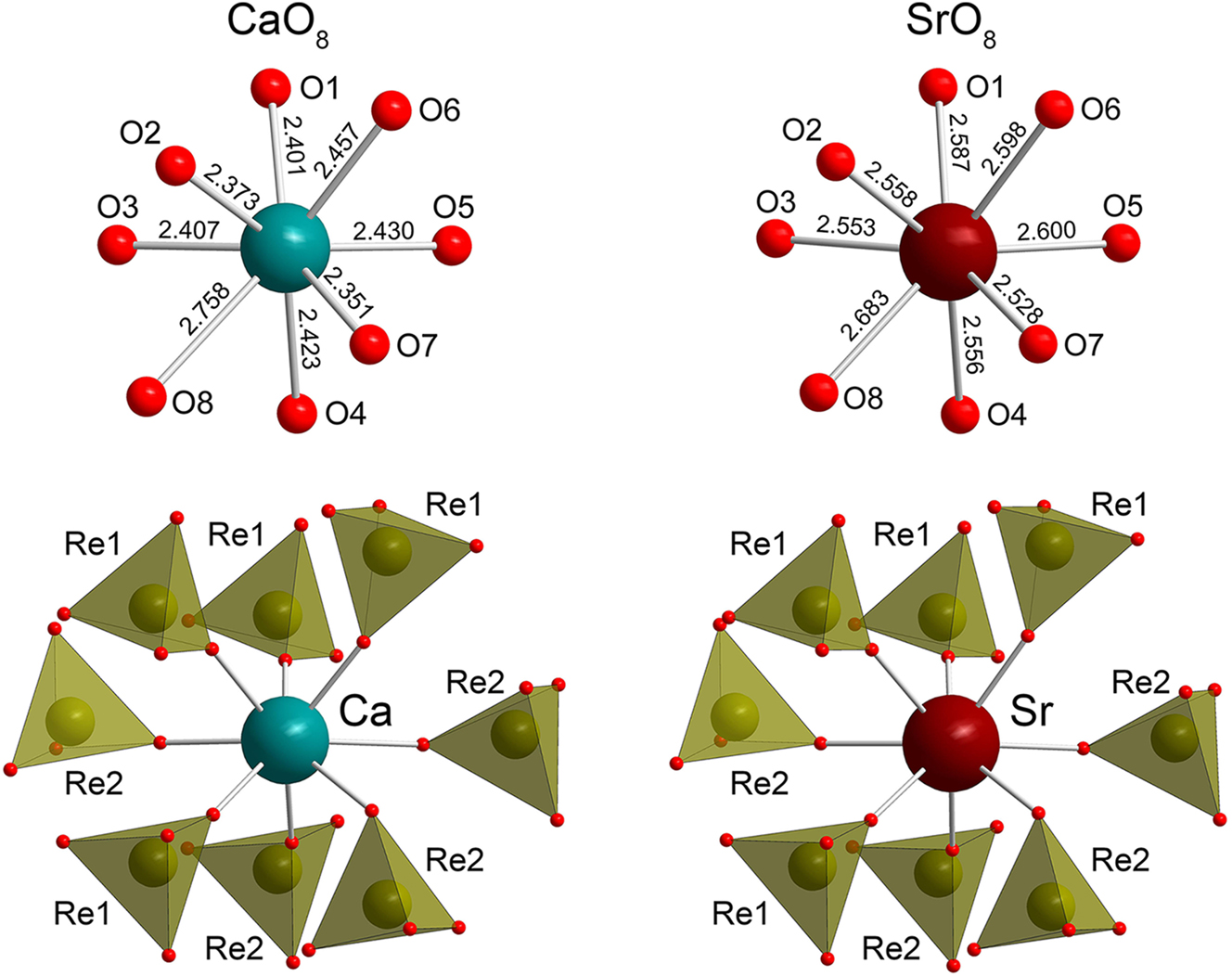

Anhydrous Ca(ReO 4 ) 2 . The structure of anhydrous calcium perrhenate is shown in Figure 1. It contains one Ca, two Re, and eight O sites (Figure 2). The compound is isostructural to the monoclinic polymorph or Sr(ReO4)2. 17 Ca2+ adopts a coordination number of eight with formation of a polyhedron which can be regarded as a bicapped trigonal prism. The Ca–O distances range from 2.353(2) Å to 2.758(5) Å all except the longest one lie between 2.353(2) Å and 2.457(1) Å. The environment of Sr2+ in Sr(ReO4)2 is essentially more regular (d(Sr – O) = 2.59(2) – 2.68(2) Å). The Re–O bonds lie within 1.706(3)–1.723(3) Å for Re1 and 1.716(1)–1.735(1) Å for Re2. The distortions of the ReO4 tetrahedra are relatively small and comparable to those in Sr(ReO4)2: d(Re1–O) = 1.66(1) – 1.74(1) Å, d(Re2–O) = 1.68(1) – 1.73(1) Å. The angles are in the range 109.1(9)° – 110.2(7)° and 108.4(6)° – 110.9(6)° for Re1O4 and Re2O4 tetrahedra, respectively. The CaO8 and ReO4 polyhedra form a 3D framework (Figure 1).

General projection of the crystal structure of Ca(ReO4)2.

Coordination environments of Ca and Sr atoms in Ca(ReO4)2 (this work) and Sr(ReO4)2 (Conrad and Schleid, 2020).

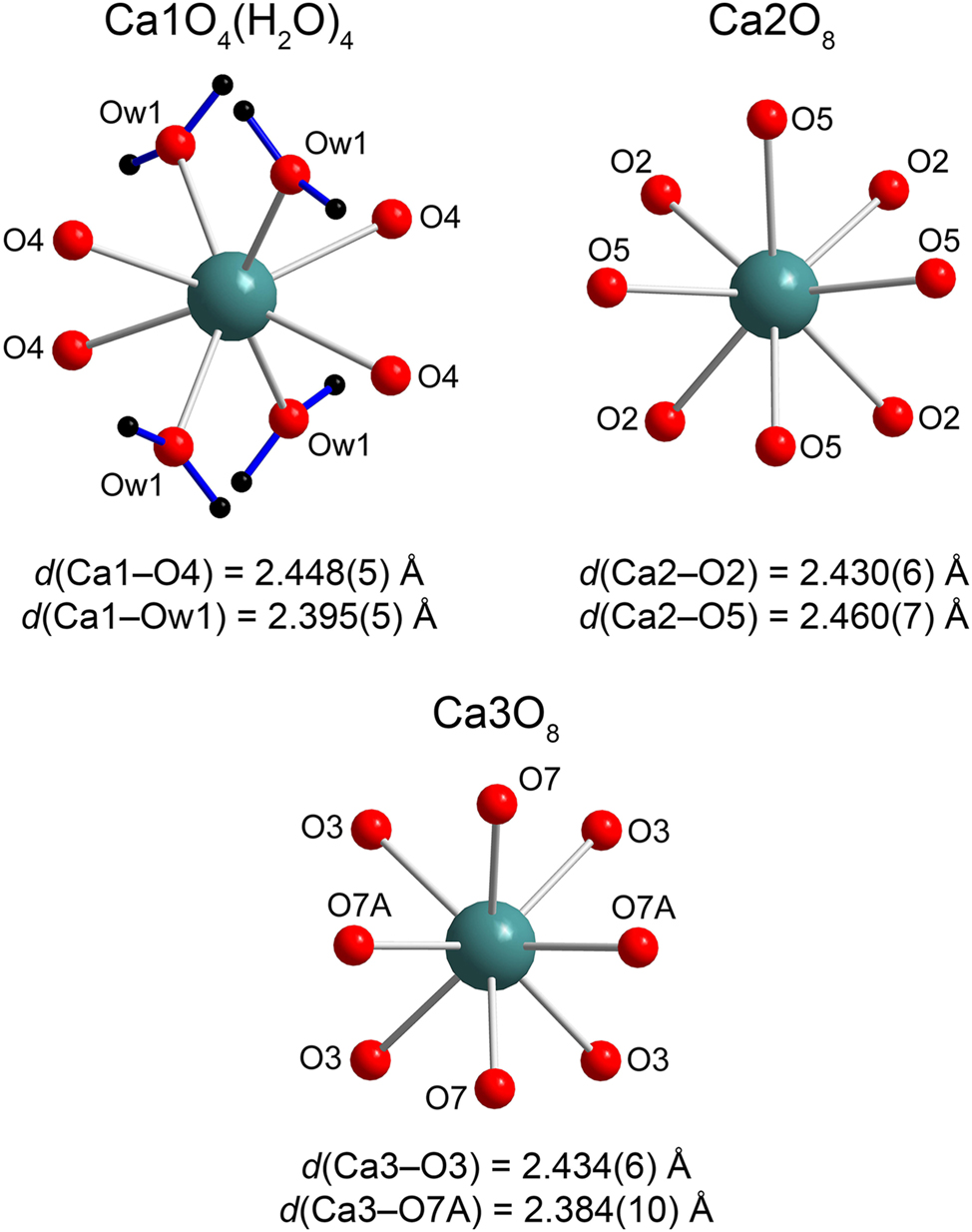

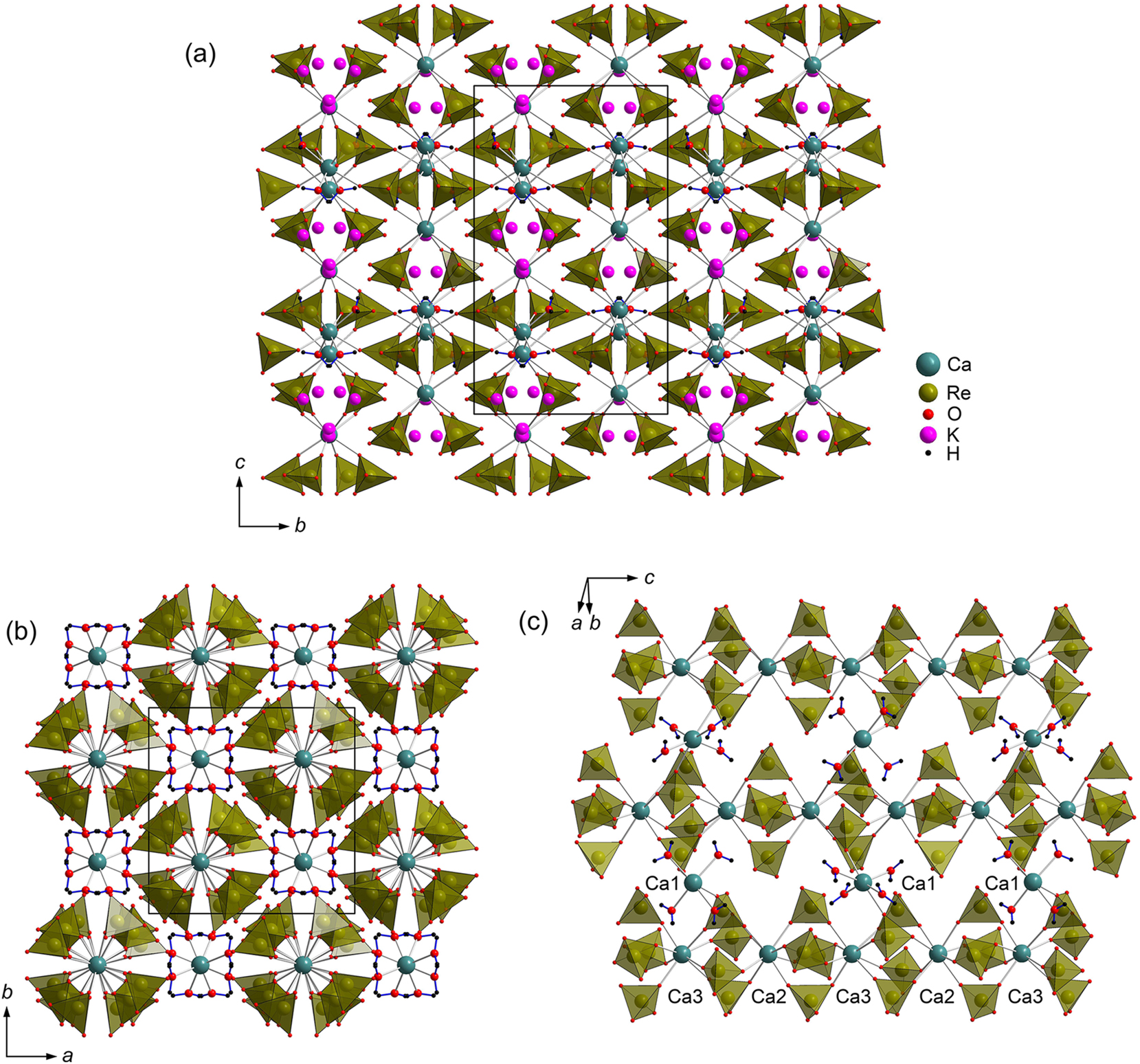

K 2 Ca 3 (ReO 4 ) 8 · 4H 2 O . This structure is symmetrical and complex and features three Ca, two Re, nine O sites one of which (O7) is split over O7A and O7B (50 %/50 % occupancy) and two weakly occupied K sites (20 and 30 %). The coordination polyhedra of all Ca2+ cations can be regarded as square antiprisms. Ca1 is coordinated by oxygen atoms from four perrhenate groups and from four water molecules (d(Ca1–O4) = 2.488(5) Å, d(Ca–Ow) = 2.395(5) Å, Figure 3) while Ca2 (d(Ca2–O2) = 2.430(6) Å, d(Ca2–O5) = 2.460(7) Å) and Ca3 (d(Ca3–O3) = 2.434(6) Å, d(Ca3–O7A) = 2.384(10) Å, d(Ca–O7B) = 2.457(11) Å), only by the perrhenate groups. The range of these bond distances is very similar to that for anhydrous Ca(ReO4)2 (vide supra) and CaCl(ReO4)·2H2O (2.359(2) Å and 2.531(2) Å). 20 The rhenium atoms center somewhat distorted tetrahedra (d(Re1–O) = 1.702(7) – 1.733(5) Å; d(Re2–O) = 1.657(10) – 1.843(10) Å). A large dissimilarity and lower precision in the bond distances for Re2 is due to orientational disorder of the Re2O4 − tetrahedron, most likely caused by the partial occupancy of the neighboring K sites. The CaO8 antiprisms and ReO4 tetrahedra share vertices to form a holey heteropolyhedral framework with relatively large cavities gilled by disordered potassium cations (Figure 4). There is one symmetrically independent Ow1 water molecule in the structure of K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O. Ow1–H1⋯O1 and Ow1–H2⋯O6 hydrogen bonds with D⋯A distances 2.814(8) and 3.110(9) Å and <DHA angles 165.83° and 165.16°, respectively, are formed.

Coordination environments of Ca in the crystal structure of K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O.

General projection of the crystal structure of K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O along the a axis with voids filled by partially occupied K cations (a). K sites are omitted in two structure projections below for clarity (b,c).

6 Discussion and concluding remarks

As noted above, the sparsity of data on “simple” inorganic perrhenates permits yet little to conclude about the structural relationships between these and other compounds of d-metal-centered tetrahedral anions. The anhydrous calcium and strontium perrhenates are isostructural but not their dihydrates, 13 , 21 despite the essential difference in the ionic radii of Ca2+ and Sr2+. 22 This structure is totally different from that of anhydrous Pb(ReO4)2 14 while the radii of Sr2+ and Pb2+ are similar and NaPb(ReO4)3 and NaSr(ReO4)3 are again isostructural. 5 Ca(TcO4)2·2H2O is isostructural to its perrhenate analog; 9 the same applies to the iso-formula compounds of strontium and, probably, lead. Again, Ba(ReO4)2·4H2O is isostructural to the corresponding pertechnetate while the anhydrous compounds adopt different structures. 9 Unfortunately, the structures of anhydrous Ca(TcO4)2 and Sr(TcO4)2 are as yet unknown.

The structures of NaCa(ReO4)3 and Ca(ReO4)2 contain relatively simple heteropolyhedral frameworks. An essentially more complex architecture is observed in that of K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O (2) which also exhibits relatively high symmetry. Contrary to hygroscopic Ca(ReO4)2 with the same coordination number of Ca2+, this compound crystalizes from aqueous solutions. This is partially in line with the behavior of hydrated alkaline earth perrhenates which effloresce, rather than deliquesce, in air. 23 It is also very likely that formation of such complex and elegant frameworks, exemplified by the structure of K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O, will, upon further studies, be observed in a variety of perrhenate-, and possible pertechnetate-based systems.

Acknowledgments

Technical support (project # 118201839) by the SPbSU X-ray Diffraction Centre is gratefully acknowledged.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: Not applicable.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

1. Deutsch, E.; Libson, K.; Vanderheyden, J.-L.; Ketring, A. R.; Maxon, H. R. The Chemistry of Rhenium and Technetium as Related to the Use of Isotopes of These Elements in Therapeutic and Diagnostic Nuclear Medicine. Int. J. Radiat. Appl. Instrum. 1986, B13, 465–467; https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-2897(86)90027-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Kim, E.; Boulègue, J. Chemistry of Rhenium as an Analogue of Technetium: Experimental Studies of the Dissolution of Rhenium Oxides in Aqueous Solutions. Radiochim. Acta. 2003, 91, 211–216.10.1524/ract.91.4.211.19968Search in Google Scholar

3. Ye, L.; Ouyang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liu, S. Recovery of Rhenium from Tungsten-Rhenium Wire by Alkali Fusion in KOH-K2CO3 Binary Molten Salt. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2020, 87, 105148; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2019.105148.Search in Google Scholar

4. Shen, L.; Tesfaye, F.; Li, X.; Lindberg, D.; Taskinen, P. Review of Rhenium Extraction and Recycling Technologies from Primary and Secondary Resources. Min. Eng. 2021, 161, 106719; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mineng.2020.106719.Search in Google Scholar

5. Charkin, D. O.; Chachin, P. A.; Nazarchuk, E. V.; Siidra, O. I. A Contribution to the Perrhenate Crystal Chemistry: the Crystal Structures of New CdTh[MoO4]3-type Compounds. Z. Kristallogr. 2023, 238, 1–5; https://doi.org/10.1515/zkri-2022-0043.Search in Google Scholar

6. Conrad, M.; Schleid, Th. Single Crystals of CaNa[ReO4]3: Serendipitous Formation and Systematic Characterization. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2019, 645, 1255–1261; https://doi.org/10.1002/zaac.201900189.Search in Google Scholar

7. Launay, S.; Rimsky, A. Structure du tris (tétraoxomolybdate) de cadmium et de thorium. Acta Crystallogr. 1980, B36, 910–912.10.1107/S0567740880004815Search in Google Scholar

8. Sedello, O.; Müller-Buschbaum, K. Zur Kristallstruktur von (Cu,Mn)UMo3O12. Z. Naturforsch. 1996, 51b, 450–452.10.1515/znb-1996-0326Search in Google Scholar

9. Strub, E.; Grödler, D.; Zaratti, D.; Yong, C.; Dünnebier, L.; Bazhenova, S.; Roca, J. M.; Breugst, M.; Zegke, M. Pertechnetates – a Structural Study across the Periodic Table. Chem. Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202400131; https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.202400131.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Silvestre, J. P. Crystal Chemistry of the Lanthanide-Alkaline or Alkaline-Earth Perrhenates and Some Related Compounds with Ag, Pb and Actinides. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1984, 94, 78–79; https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-1693(00)94544-4.Search in Google Scholar

11. Müller-Buschbaum, H. Zur Kristallchemie der Oxometallate des Thoriums. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2009, 635, 1065–1082.10.1002/zaac.200900039Search in Google Scholar

12. Liu, D. M.; Qian, Z. H.; Zhang, Q. A. Synthesis, Crystal Structure, and Thermal Decomposition of LiCa(AlH4)3. J. Alloys Compd. 2012, 520, 202–206.10.1016/j.jallcom.2012.01.011Search in Google Scholar

13. Todorov, T.; Angelova, O.; Macíček, J. The Covert Water in the Structure of Sr(ReO4)2.2H2O: a Revision of the Sesquihydrate Model. Acta Crystallogr. 1996, C52, 1319–1323.10.1107/S0108270195016362Search in Google Scholar

14. Picard, J. P.; Besse, J. P.; Chevalier, R.; Gasperin, M. J. Structure Cristalline du Perrhénate de Plomb Pb(ReO4)2. Solid State Chem. 1987, 69, 380–384; https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4596(87)90097-1.Search in Google Scholar

15. Todorov, T.; Macicek, J. Barium Perrhenate Monohydrate. Acta Crystallogr. 1995, C51, 1034–1038; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0108270194013909.Search in Google Scholar

16. Macíček, J.; Todorov, T. Structure of a Barium Perrhenate Tetrahydrate. Acta Crystallogr. 1992, C49, 599–603.10.1107/S0108270191011125Search in Google Scholar

17. Conrad, M.; Russ, P. L.; Schleid, Th. Sr[ReO4]2: The First Single Crystals of an Anhydrous Alkaline-Earth Metal Meta-Perrhenate. Z. Anorg. Allgem. Chem. 2020, 646, 1872–1875; https://doi.org/10.1002/zaac.202000312.Search in Google Scholar

18. Conrad, M.; Bette, S.; Dinnebier, R. E.; Schleid, Th. On the Thermal Dimorphy of the Strontium Perrhenate Sr[ReO4]2. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2024, 650, e202400045; https://doi.org/10.1002/zaac.202400045.Search in Google Scholar

19. Gagné, O. C.; Hawthorne, F. C. Comprehensive Derivation of Bond-Valence Parameters for Ion Pairs Involving Oxygen. Acta Crystallogr. 2015, B71, 562–578; https://doi.org/10.1107/S2052520615016297.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Jarek, U.; Holyńska, M.; Ślepokura, K.; Lis, T. Calcium Chloride Rhenate(VII) Dihydrate. Acta Crystallogr. 2007, C63, i77–i79.10.1107/S0108270107037456Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Picard, J. P. P.; Baud, G.; Besse, J.-P.; Chevalier, R.; Gasperin, M. Structure Cristalline de Ca(ReO4)2·2H2O. J. Less-Common Met. 1984, 96, 171–176; https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5088(84)90192-9.Search in Google Scholar

22. Shannon, R. D. Revised Effective Ionic Radii and Systematic Studies of Interatomic Distances in Halides and Chalcogenides. Acta Crystallogr. 1976, A32, 751–767; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0567739476001551.Search in Google Scholar

23. Smith, W. T.Jr.; Maxwell, G. E. The Salts of Perrhenic Acid. IV. The Group II Cations, Copper(II) and Lead(II). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 658–660; https://doi.org/10.1021/ja01146a047.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/zkri-2025-0008).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Obituary

- Obituary for Hartmut Bärnighausen

- Micro Review

- Bismuth as reactive and non-reactive flux medium for the synthesis and crystal growth of intermetallics

- Organic and Metalorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Racemic and unusual enantiomeric crystal forms of N-cycloalkyl-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamides and their biological activity

- Inorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Lead phosphate oxyapatite, Pb10(PO4)6O, with c-double superstructure

- A novel microporous uranyl silicate prepared by high temperature flux technique

- The Grubbs catalyst – dichlorido(1-(2,6-diethylphenyl)-3,5,5-trimethyl-3-phenylpyrrolidin-2-ylidene)-({5-nitro-2-[(propan-2-yl)oxy]phenyl}methylidene)ruthenium(II) – some observations on the crystallography and stereochemistry of a racemic mimic pair

- Thermal decomposition of copper(II) hydroxide and hydroxocarbonates according to X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy in operando

- New calcium perrhenates: synthesis and crystal structures of Ca(ReO4)2 and K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Obituary

- Obituary for Hartmut Bärnighausen

- Micro Review

- Bismuth as reactive and non-reactive flux medium for the synthesis and crystal growth of intermetallics

- Organic and Metalorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Racemic and unusual enantiomeric crystal forms of N-cycloalkyl-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamides and their biological activity

- Inorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Lead phosphate oxyapatite, Pb10(PO4)6O, with c-double superstructure

- A novel microporous uranyl silicate prepared by high temperature flux technique

- The Grubbs catalyst – dichlorido(1-(2,6-diethylphenyl)-3,5,5-trimethyl-3-phenylpyrrolidin-2-ylidene)-({5-nitro-2-[(propan-2-yl)oxy]phenyl}methylidene)ruthenium(II) – some observations on the crystallography and stereochemistry of a racemic mimic pair

- Thermal decomposition of copper(II) hydroxide and hydroxocarbonates according to X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy in operando

- New calcium perrhenates: synthesis and crystal structures of Ca(ReO4)2 and K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O