Abstract

Single crystal specimens of lead phosphate oxyapatite, Pb10(PO4)6O, were prepared and the structure was refined in

1 Introduction

Most of the apatite-type compounds (hereafter referred to as ‘apatites’) with general formula A12A23(BO4)3X (Z = 2; A1, A2, B and X are designated also as atomic sites) crystallize in the hexagonal space group P63/m with the X site at (0, 0, z) [aristotype structure; z = 0 (Wyckoff position 2b with site symmetry

Occurrence of commensurate modulation along the c-axis on apatite structure was first reported in 1960 as c-double superstructure on lead phosphate oxyapatite, Pb10(PO4)6O, likely be due to an orderly incorporation of the oxide anion in the channel.

8

Soon after that some possible ordering schemes of incorporated oxide anions in

The authors had been paying attention on Pb10(PO4)6O mainly due to highly prolate displacement ellipsoid at the X site position [z = 0.134(9)] under P63/m refinement. 11 This feature implied that the compound might be a potential oxide-ion conductor for migration of X site oxide anion through the channel. 12 Assessment of host-guest interaction, attraction, repulsion or both, in the channel is needed on correct superstructure for further considerations.

For the above reasons the authors prepared Pb10(PO4)6O (hereafter referred to as PPO) single crystals and explored host-guest interaction in the c-double superstructure. Structural models with space groups

2 Experimental methods

2.1 Sample preparation and characterization

PPO single crystals were grown from melt of a mixture of PbO (99.5 %; FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Co., Japan) and NH4H2PO4 (99.0 %; FUJIFILM Wako) reagents with a molar ratio of 2:1. The mixture was ground in an agate mortar and wrapped with a platinum foil to suppress evaporation of P2O5 component. The wrapping was then put in a latex balloon and hydrostatically pressed in water for several hours (500–600 kgf/cm2). The wrapping was encased in an alumina crucible with a lid, set inside a saggar and heated in air in an electric furnace. Preparation conditions were optimized by referring to thermogravimetry/differential thermal analysis (TG/DTA) and powder X-ray diffraction (pXRD) profiles. An association of Pb4O(PO4)2 with PPO 11 was allowed for the product.

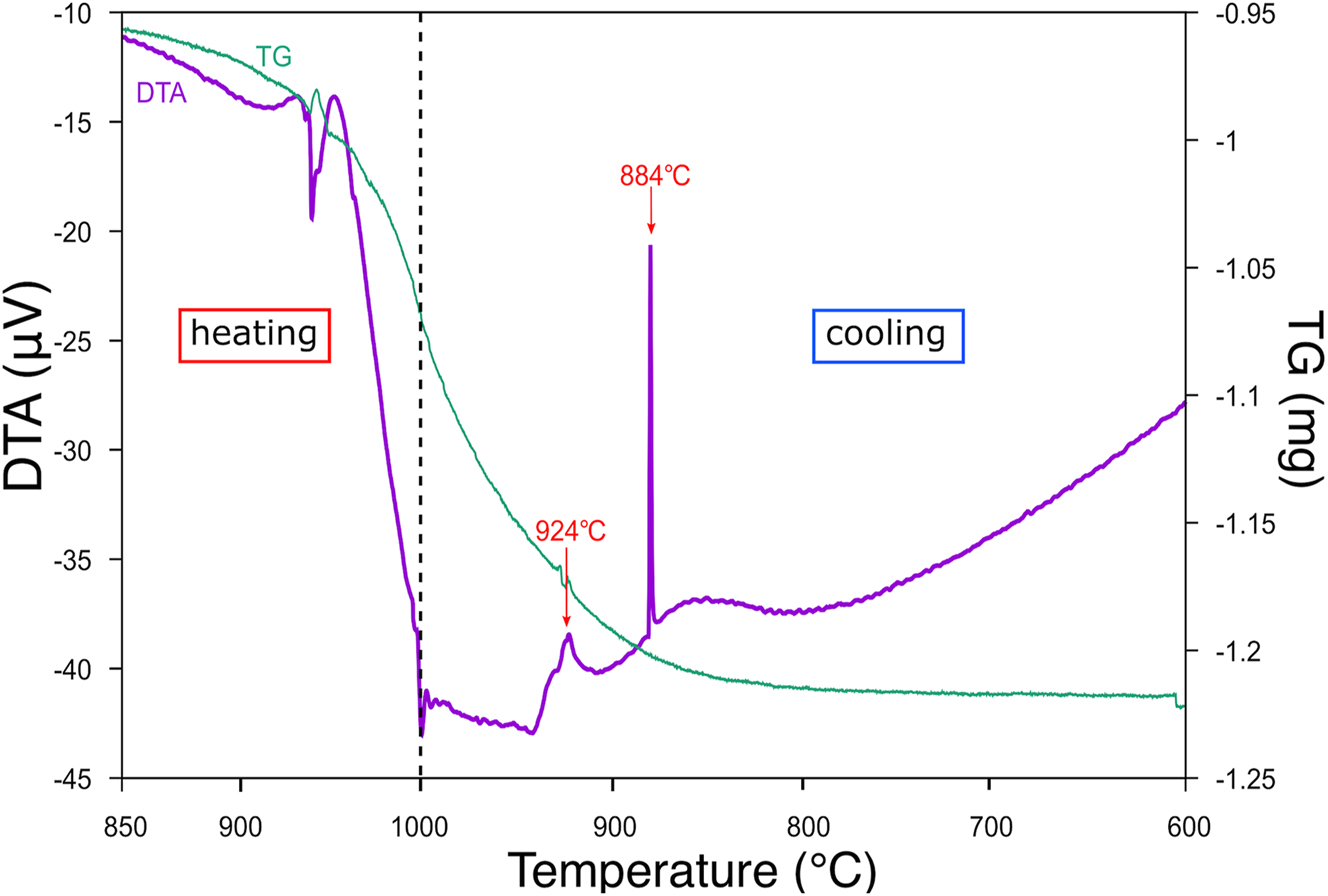

TG/DTA data of the mixture were collected with a Rigaku ThermoPlus TG 8120 on both heating and consecutive cooling cycles (ΔT/min = 7 °C on both cycles) operated under air atmosphere. No inert gas-flow was applied to prevent unnecessary evaporation of P2O5 component. Maximum temperature was set at 1000 °C. TG/DTA profiles showed an endothermic peak at 945 °C on the heating cycle and consecutive weight loss (Figure 1). This weight loss lasted until T ≈ 800 °C on the cooling cycle. Exothermic peaks at 924 °C and 884 °C were apparent on the cooling cycle. The samples with various cooling conditions were examined with pXRD, and Pb4O(PO4)2 predominated in most of the samples. Since the target compound was the majority phase only in the sample quenched from 920 °C, exothermic peaks at 924 °C and 884 °C correspond to crystallization of PPO and Pb4O(PO4)2, respectively.

TG/DTA profiles of mixture of PbO and NH4H2PO4 over 120−200 min. Purple line: DTA profile; green line: TG profile.

On preparations of the single crystal specimens used in the following experiments, the temperature was raised from room temperature to 1000 °C in 1 h. Temperature was slowly lowered to 920 °C at a rate of 1.2 °C/h, held at this temperature for 25 h, and then the crucible was taken out from the furnace and the wrapping was quenched by dropping it into water (batch 12). Preservation of a high temperature state of PPO was expected since the specimen was quenched together with a platinum foil within 15 s after opening the saggar. Slowly cooled specimens were also prepared for comparisons with cooling rate of 3 °C/h to 800 °C and then 20 °C/h to 500 °C (batch 9) or 6 °C/h from 1000 °C to 500 °C (batch 8). After that the furnace was cooled down by turning the power off. Quantitative chemical analyses (a JEOL JSM-6010LV with integrated EDS) showed no sign of Pb-deficiency and thus the empirical chemical formula of the specimens was Pb10(PO4)6O.

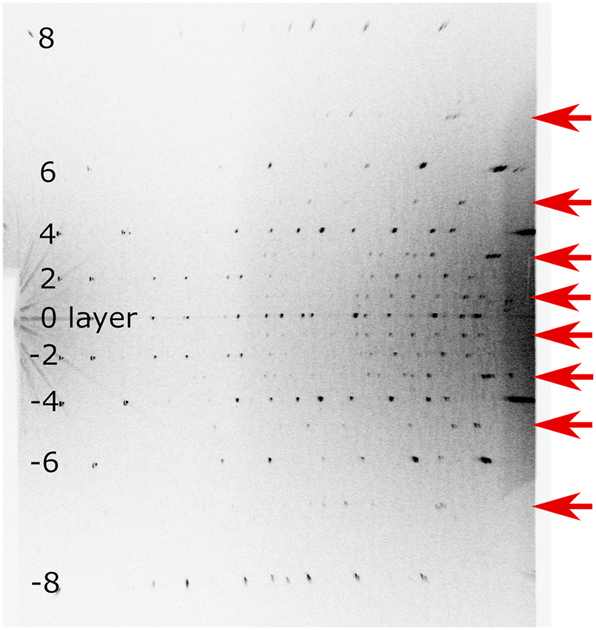

Single-crystal specimens were picked out under polarizing optical microscope and examined with a Weissenberg camera and Cu Kα radiation (Figure 2). Ni-foil was used as a β-filter. On all the specimens there were apparent c-double superstructure reflections on the rotation photographs (rotated around c), and presence of mirror symmetry normal to the rotation axis was also apparent. On the other hand, diffraction spots on the 1st-layer Weissenberg photograph of a specimen from batch 8 could be successfully indexed with a and γ of the parent structure.

Rotation photograph of specimen from batch12 (rotated 20° around c) using a Weissenberg camera. Cu Kα radiation and Ni-filter was used. Superstructure reflections were indicated by red arrows.

2.2 Data collection and data processing

High absorbance of Pb for X-ray and thus low diffraction intensities are intrinsic problem on X-ray investigations of Pb-bearing compounds. Therefore, complete data sets were collected on two specimens of different thermal histories to check if there was noteworthy difference on two refined structures. Specimens used on the following measurements were ground into spheres (d = 170 μm and 140 μm for specimens from batches 12 and 9, hereafter referred to as b12s2 and b9s1, respectively). The intensities of Bragg reflections and values of θ were measured on a Rigaku AFC-5S automated four-circle diffractometer. Graphite-monochromatized Mo Kα radiation and the ω-2θ scan method were employed for the data collection with scan width 1.5° + 0.35 tanθ and scan speed of 4° min−1. Diffraction intensities of three standard reflections were monitored after every 200 reflections. Totals of 41092 reflections up to 2θ = 90° (b12s2) and 30861 reflections up to 2θ = 80° (b9s1) were measured for the full sphere of reciprocal space. Relationships found among Bragg positions and observed intensities from the parent lattice suggested Laue group 6/m. Possible space groups for superstructure will be discussed more rigorously in the next chapter. The least-squares fitting of the peak positions of 25 intense reflections in the range 43.2° < 2θ < 47.5° resulted in the cell dimensions a = 9.8151(15) Å and c = 14.8458(11) Å for b12s2 after calibration with Si. 15 Cell dimensions for b9s1, a = 9.8178(12) Å and c = 14.8478(10) Å, matched to the values within their combined standard uncertainties (s.u.s) (σ). See Table 1 for further crystallographic details and experimental conditions.

Crystallographic data (b9s1, b12s2).

| b9s1 | b12s2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Crystal data | ||

| Formula | Pb10(PO4)6O | Pb10(PO4)6O |

| M r | 2657.8 | 2657.8 |

| a, c (Å) | 9.8178(12), 14.8478(10) | 9.8151(15), 14.8458(11) |

| Volume (Å3) | 1239.4(4) | 1238.6(5) |

| Z | 2 | 2 |

| D x (g/cm3) | 7.1217 | 7.1266 |

| μ (mm−1) | 68.2618 | 68.3086 |

| Crystal shape | Sphere | Sphere |

| Crystal size (mm3) | 0.14 × 0.14 × 0.14 | 0.17 × 0.17 × 0.17 |

| Data collection | ||

| Radiation type, wavelength (Å) | Mo Kα, 0.71069 | Mo Kα, 0.71069 |

| Diffractometer | Rigaku AFC-5S | Rigaku AFC-5S |

| Data collection method, | ω-2θ scan | ω-2θ scan |

| Scan speed (° min−1) | 4 | 4 |

| 2θ (°) range collected | 2θ ≤ 80 | 2θ ≤ 90 |

| μr for spherical absorption correction | 4.7697 | 5.8062 |

| Data truncation criteria | |F̄obs| > 3σ(F̄obs) | |F̄obs| > 3σ(F̄obs) |

| |Fobs|max ≤ 2|Fobs|min among equivalents | |Fobs|max ≤ 2|Fobs|min among equivalents |

The intensity data were converted to |Fobs| and their s.u.s after applying Lorentz, polarization and spherical absorption corrections (μr = 5.81 for b12s2). These structure amplitudes were averaged for the Laue group to be assumed at respective structure refinement. Some weak [|F̄obs| < 3σ(F̄obs)] and ill-behaved (|Fobs|max > 2.0|Fobs|min among equivalents) reflections were removed from the data sets for respective point group to be assumed.

3 Structure refinement

The following examinations had done on both b12s2 and b9s1 data sets individually. We refined the parent structure first with subset of the data and then examined possible long-range order in superstructure with

Details of structure refinements (b12s2).

| Refinement | Parent structure | Superstructure | |

| Crystal system, space group | Hexagonal, P63/m (#176) | Trigonal,

|

Hexagonal,

|

| Refinement method | Full-matrix least-squares on F | Full-matrix least-squares on F | Full-matrix least-squares on F |

| 2θ(°) range used | 20.57 ∼ 90 | 20.57 ∼ 90 | 20.57 ∼ 90 |

| No. of measured, independent and used reflections | 20520, 1802, 538 | 41092, 6868, 1589 | 41092, 7040, 1705 |

| Rint (%) for used reflections | 4.13 | 5.43 | 5.46 |

| Partial (no X site) structure | |||

| No. of parameters | 64 | 70 | |

| R(F), R(F2), wR(F), S(F) | 0.0930, 0.0984, 0.1169, 1.97 | 0.0291, 0.0397, 0.0282, 0.48 | |

| Δρmax, Δρmin (e Å−3) | 13.99, −14.64 | 18.73, −5.08 | |

| Full structure | |||

| No. of parameters | 41 | 67 | 74 |

| R(F), R(F2), wR(F), S(F) | 0.0264, 0.0366, 0.0292, 0.62 | 0.0930, 0.0981, 0.1166, 1.97 | 0.0279, 0.0371, 0.0266, 0.45 |

| Δρmax, Δρmin (e Å−3) | 4.39, −3.10 | 14.17, −14.45 | 4.51, −4.94 |

3.1 P63/m refinement of the parent structure

The structure was refined firstly in aristotype apatite structure with reindexed diffraction data as a foundation of the superstructure models. The least-squares program LSGCEX 16 was used for structure refinements with variables including one scale and one isotropic extinction factor (type I with the Lorentzian mosaic spread). 17 A simple weighting scheme with weights proportional to σ−2 was employed. Conditions for structure refinements, such as choice of form factors, application of low-angle threshold for diffraction data, and applicable restraints in the superstructure refinements were also examined at this step. The refinement started from the atomic coordinates and anisotropic displacement parameters (ADPs) given for Pb5(PO4)3Cl (OP-4 in ref. 5]) for the host structure and the z-coordinate of the X site with ADPs given in ref. 11]. Neutral form factors and low-angle threshold for diffraction data (0.25 ≤ sinθ/λ) were employed after examinations noted in ref. 5]. Neutral form factors for respective atoms and their anomalous dispersion terms were taken from International Tables for Crystallography, Vol. C. In the final iterations the occupation factor at the X site was fixed at 1/4 and all the other atomic sites were assumed fully occupied by respective elements. The least-squares calculation converged at R(F), R(F2) and wR(F) = 0.026, 0.037 and 0.029, respectively, for 538 independent reflections with 41 parameters. Minimum and maximum of Δρ were −3.10 e Å−3 at (0.01, 0.23, 0.75) and 4.39 e Å−3 at (0.99, 0.79, 0.81), respectively. Selected structural parameter values are listed in Table 3.

Extinction factor, atomic coordinates, and anisotropic displacement parameters (Å2) of the parent structure with re-indexed dataset (P63/m, b12s2).

| Extinction factor | 0.037(6) | |

| Site and site symmetry | ||

| A1 4f 3.. | Occupancy | 1 |

| Pb | x | 1/3 |

| y | 2/3 | |

| z | 0.00299(12) | |

| U 11 | 0.01769(16) | |

| U 33 | 0.0128(2) | |

| A2 6h m.. | Occupancy | 1 |

| Pb | x | 0.00169(8) |

| y | 0.24288(8) | |

| z | 1/4 | |

| U 11 | 0.0116(2) | |

| U 22 | 0.0247(3) | |

| U 33 | 0.0312(3) | |

| U 12 | 0.0032(2) | |

| B 6h m.. | Occupancy | 1 |

| P | x | 0.4010(4) |

| y | 0.3752(4) | |

| z | 1/4 | |

| U 11 | 0.0078(12) | |

| U 22 | 0.0069(11) | |

| U 33 | 0.0143(14) | |

| U 12 | 0.0037(10) | |

| O1 6h m.. | Occupancy | 1 |

| O | x | 0.3348(17) |

| y | 0.4864(15) | |

| z | 1/4 | |

| U 11 | 0.038(7) | |

| U 22 | 0.019(5) | |

| U 33 | 0.026(6) | |

| U 12 | 0.023(5) | |

| O2 6h m.. | Occupancy | 1 |

| O | x | 0.5267(18) |

| y | 0.1106(17) | |

| z | 1/4 | |

| U 11 | 0.033(7) | |

| U 22 | 0.031(6) | |

| U 33 | 0.035(7) | |

| U 12 | 0.027(6) | |

| O3 12i 1 | Occupancy | 1 |

| O | x | 0.3483(12) |

| y | 0.2676(10) | |

| z | 0.0815(14) | |

| U 11 | 0.040(5) | |

| U 22 | 0.021(3) | |

| U 33 | 0.028(5) | |

| U 12 | 0.019(4) | |

| U 13 | −0.018(4) | |

| U 23 | −0.016(3) | |

| X 4e 3.. | Occupancy | 1/4 |

| O | x | 0 |

| y | 0 | |

| z | 0.181(14) | |

| U 11 | 0.010(9) | |

| U 33 | 0.13(10) |

-

U22 = U11 and U12 = 1/2U11 at A1 and O4 sites, U13 = U23 = 0 at A1, A2, B, O1, O2, and X sites.

There was no notable difference between our structure and previously reported one for the parent structure. 11 As can be seen in Table 3, mean square displacements (MSDs, <u2> Å2) of P5+ at B site were small and even smaller than those of Pb2+ at A sites in spite of their weights. Displacement ellipsoid at A2 site [at (0.00169(8), 0.24288(8), 1/4)] was larger and more anisotropic than that in OP-4; MSDs at the site were 1.3 and 3.2 times larger along <001> and <010>, respectively, in PPO and as a result the ellipsoid was flat in the yz-plane. These larger displacements, particularly along <010>, implies that the 2 × c modulation occurred in sizes of A2 triangles.

3.2 P

3

‾

refinement of superstructure

The

In the next step oxide anions were introduced in the channel (at Wyckoff positions 1a, 1b and 2c) and refined the positions, ADPs, and their partitioning when necessary. Total number of channel site oxide anions was restrained to be 2.0. ADP values at X sites were taken from SrPr4(SiO4)3O 18 and refined at final iterations. We examined all the possible X site positions and their combinations, and a structure with fully occupied X site at z = 0.192(15) was the only structure which yielded convergence of least-squares calculations with ADPs. The ADP ellipsoid at the X site was highly elongated along <001> as it was seen after P63/m refinement.

Sizes of A2 triangles in the refined

The structure was refined also with S helxl 19 to check if the specimen had been twinned. Two X sites with fixed ADP values from ref. 18] were set inside the channel to make the model topologically the same as the structure in ref. 10]. Only 0.25 ≤ sinθ/λ and |F̄obs| > 3σ(F̄obs) thresholds were applied for data truncation. Least-squares cycles converged at R1 = 0.055 without twin for 66 parameters and 1770 data. R1 reduced to 0.027 by applying [100/010/001̄] twin matrix with fractions of 0.50:0.50. Volumes of two BO4 tetrahedra got closer (1.884 and 1.853 Å3) but they were still highly distorted (O–B–O bond-angle variances were 32° and 34° with quadratic elongation indices 1.010 on both).

3.3 P

6

‾

refinement of superstructure

We continued structure refinement, hereafter with

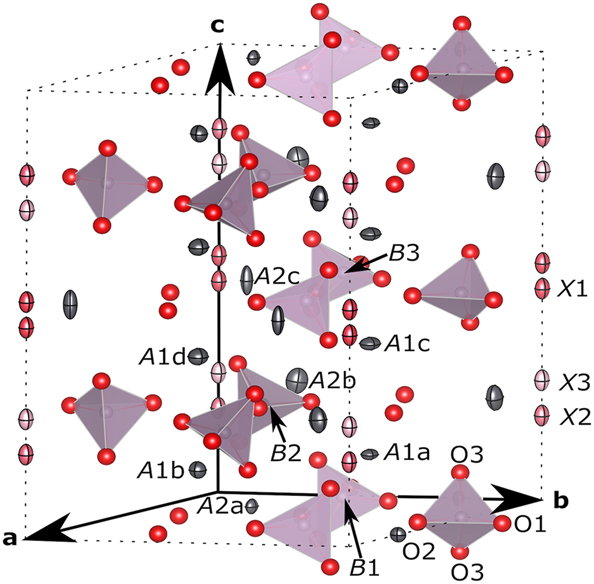

Next, we refined the structure with oxide anions in the channel. Oxide anions were introduced on the c-axis at z = 0.47 (X1), 0.19 (X2) and 0.27 (X3), in other words pairs of positions near the faces of A2b and A2c triangles, after results of difference Fourier synthesis. The same considerations applied on the structure refinement as noted in §3.2. Least-squares calculation with positions and occupation factors at three X sites as free variables resulted in unreasonably large occupancy at X1 site [72(13)%] in spite of small separation between two equivalent positions connected by a mirror plane at z = 1/2. Occupancies at X2 and X3 sites were approximately 1/3 and 1/6 of the value at X1 site after this calculation. Least-squares calculation became unstable when one more oxide anion site was introduced wherever possible in the channel: occupancy of one out of X2, X3 and X4 (additional) sites became negative and they moved across the border of cells. Therefore we limited number of X sites in the model to three, and occupancy at the X1 site was set at 1/2 in consecutive iterations. The total number of oxide anions exceeded 2.0 per cell in all the cases whenever possible, and therefore further restraint was applied on the total of occupancies at X2 and X3 sites to be 1/2. This calculation converged at R(F), R(F2) and wR(F) = 0.028, 0.037 and 0.027, respectively, for 1705 reflections with 74 parameters. Minimum and maximum of Δρ were −4.94 e Å−3 at (0.0, 0.74, 0.01) and 4.51 e Å−3 at (0.30, 0.10, 0.51), respectively. Δρ at (0, 0, 0.47) was reduced to 3.92 e Å−3. Any attempt to refine ADPs at X sites, however, was unsuccessful and therefore we employed the ADP values in ref. 18] in the final structure. In addition, ratios among occupancies at X sites [1/2, 30(2) % and 20 % at X1, X2 and X3 sites, respectively] after final iterations apparently differed from those without restraints. Occurrence of these minor inconsistencies indicated difficulty to picture a projection of various local structures by using three distinct X site positions even with ADPs. This also indicated potential ambiguities on positions and occupancies of X2 and X3 sites more than their s.u.s. Convergence of structure refinement with b9s1 data set was virtually the same with 1307 reflections and so was the structure: 28 out of 47 positional parameters (including z-coordinates of three X sites) matched to each other within their combined s.u.s and only two positional parameters (x of O3c and y of O3d) differed more than 3 times of combined s.u.s. These two specimens have different thermal histories but essentially the same structure, suggesting that the target compound crystallizes from melt in the superstructure and an occurrence of order-disorder phase transition is not likely. Crystal structure of PPO is shown in Figure 3. Structural parameter values for b12s2 are listed in Table 4. Selected bond distances and bond-valence sums are listed in Table 5. CIF file can be obtained from CCDC website on quoting the deposition number CSD 2363464.

Orthographic view of the

Extinction factor, atomic coordinates, and atomic displacement parameters (Å2) of the superstructure (

| Extinction factor | 0.039(4) | |

| Site and site symmetry | ||

| A1a 2h 3.. | Occupancy | 1 |

| Pb | x | 1/3 |

| y | 2/3 | |

| z | 0.1306(3) | |

| U 11 | 0.0148(6) | |

| U 33 | 0.0056(12) | |

| A1b 2h 3.. | Occupancy | 1 |

| Pb | x | 2/3 |

| y | 1/3 | |

| z | 0.1252(3) | |

| U 11 | 0.0146(6) | |

| U 33 | 0.0152(15) | |

| A1c 2h 3.. | Occupancy | 1 |

| Pb | x | 1/3 |

| y | 2/3 | |

| z | 0.3778(3) | |

| U 11 | 0.0217(7) | |

| U 33 | 0.0084(11) | |

| A1d 2h 3.. | Occupancy | 1 |

| Pb | x | 2/3 |

| y | 1/3 | |

| z | 0.3779(3) | |

| U 11 | 0.0206(7) | |

| U 33 | 0.0150(16) | |

| A2a 3j m.. | Occupancy | 1 |

| Pb | x | 0.2561(2) |

| y | 0.2568(2) | |

| z | 0 | |

| U 11 | 0.0095(6) | |

| U 22 | 0.0061(5) | |

| U 33 | 0.0116(7) | |

| U 12 | 0.0026(5) | |

| A2b 6l 1 | Occupancy | 1 |

| Pb | x | 0.0018(3) |

| y | 0.2437(3) | |

| z | 0.25319(14) | |

| U 11 | 0.0135(6) | |

| U 22 | 0.0181(6) | |

| U 33 | 0.0366(10) | |

| U 12 | 0.0051(5) | |

| U 13 | −0.0002(5) | |

| U 23 | 0.0019(5) | |

| A2c 3k m.. | Occupancy | 1 |

| Pb | x | 0.2247(2) |

| y | 0.2200(2) | |

| z | 1/2 | |

| U 11 | 0.0084(6) | |

| U 22 | 0.0075(5) | |

| U 33 | 0.0476(12) | |

| U 12 | 0.0038(5) | |

| B1 3j m.. | Occupancy | 1 |

| P | x | 0.0229(10) |

| y | 0.3999(10) | |

| z | 0 | |

| U iso | 0.0094(3) | |

| B2 6l 1 | Occupancy | 1 |

| P | x | 0.4007(8) |

| y | 0.3751(8) | |

| z | 0.2446(5) | |

| B3 3k m.. | Occupancy | 1 |

| P | x | 0.0287(11) |

| y | 0.4016(11) | |

| z | 1/2 | |

| O1a 3j m.. | Occupancy | 1 |

| O | x | 0.476(3) |

| y | 0.162(3) | |

| z | 0 | |

| U iso | 0.0167(7) | |

| O1b 6l 1 | Occupancy | 1 |

| O | x | 0.3340(19) |

| y | 0.485(2) | |

| z | 0.2451(15) | |

| O1c 3k m.. | Occupancy | 1 |

| O | x | 0.497(3) |

| y | 0.145(3) | |

| z | 1/2 | |

| O2a 3j m.. | Occupancy | 1 |

| O | x | 0.419(3) |

| y | 0.510(3) | |

| z | 0 | |

| O2b 6l 1 | Occupancy | 1 |

| O | x | 0.5292(18) |

| y | 0.1119(17) | |

| z | 0.2569(13) | |

| O2c 3k m.. | Occupancy | 1 |

| O | x | 0.416(3) |

| y | 0.550(3) | |

| z | 1/2 | |

| O3a 6l 1 | Occupancy | 1 |

| O | x | 0.089(2) |

| y | 0.362(2) | |

| z | 0.0875(14) | |

| O3b 6l 1 | Occupancy | 1 |

| O | x | 0.363(2) |

| y | 0.2796(19) | |

| z | 0.1563(14) | |

| O3c 6l 1 | Occupancy | 1 |

| O | x | 0.339(2) |

| y | 0.261(2) | |

| z | 0.3267(16) | |

| O3d 6l 1 | Occupancy | 1 |

| O | x | 0.0678(19) |

| y | 0.3281(19) | |

| z | 0.4220(15) | |

| X1 2g 3.. | Occupancy | 1/2 |

| O | x | 0 |

| y | 0 | |

| z | 0.471(5) | |

| U 11 | 0.0107a | |

| U 33 | 0.0242a | |

| U 12 | 0.00537a | |

| X2 2g 3.. | Occupancy | 0.30(2) |

| O | x | 0 |

| y | 0 | |

| z | 0.188(6) | |

| X3 2g 3.. | Occupancy | 0.20 |

| O | x | 0 |

| y | 0 | |

| z | 0.267(10) |

-

U22 = U11 and U12 = 1/2U11 at A1 sites, U13 = U23 = 0 at A1, A2a, A2c sites. Common U values were used over B sites, over O1, O2, O3 sites, and over X sites. aTaken from ref. 18].

Selected interatomic distances (Å), bond angles (°), polyhedral volumes (Å3) and bond-valence sums in

| A1 sites | |

| A1a‒O1b [ × 3] | 2.47(2) |

| A1a‒O2a [ × 3] | 2.85(3) |

| A1a‒O3a [ × 3] | 2.82(2) |

| Mean value | 2.71(2) |

| BVS | 2.09, 20 2.10 21 |

| A1b‒O1a [ × 3] | 2.56(2) |

| A1b‒O2b [ × 3] | 2.726(19) |

| A1b‒O3b [ × 3] | 2.80(2) |

| Mean value | 2.70(2) |

| BVS | 2.04, 20 2.03 21 |

| A1c‒O1b [ × 3] | 2.66(2) |

| A1c‒O2c [ × 3] | 2.49(2) |

| A1c‒O3d [ × 3] | 3.10(2) |

| Mean value | 2.75(2) |

| BVS | 2.04, 20 2.05 21 |

| A1d‒O1c [ × 3] | 2.53(2) |

| A1d‒O2b [ × 3] | 2.616(19) |

| A1d‒O3c [ × 3] | 3.03(2) |

| Mean value | 2.72(2) |

| BVS | 2.08, 20 2.09 21 |

| A2 sites | |

| A2a‒O1a | 2.74(4) |

| A2a‒O2a | 2.18(2) |

| A2a‒O3a [ × 2] | 2.67(2) |

| A2a‒O3b [ × 2] | 2.51(2) |

| Mean value | 2.55(2) |

| BVS | 1.97, 20 2.07 21 |

| A2b‒O1b | 2.921(15) |

| A2b‒O2b | 2.46(3) |

| A2b‒O3a | 2.67(2) |

| A2b‒O3b | 2.798(17) |

| A2b‒O3c | 2.509(19) |

| A2b‒O3d | 2.62(2) |

| A2b‒O4b | 2.57(4) |

| A2b‒O4c | 2.393(13) |

| Mean value | 2.62(2) |

| BVS | 1.68, 20 1.71 21 |

| A2c‒O1c | 3.10(4) |

| A2c‒O2c | 2.81(2) |

| A2c‒O3c [ × 2] | 2.75(2) |

| A2c‒O3d [ × 2] | 2.54(2) |

| A2c‒O4a [ × 2] | 2.224(15) |

| Mean value | 2.62(2) |

| BVS | 1.87, 20 1.93 21 |

| B Sites | |

| B1O4 tetrahedra | |

| B1–O1a | 1.58(3) |

| B1–O2a | 1.55(3) |

| B1–O3a [ × 2] | 1.58(2) |

| Mean value | 1.57(3) |

| BVS | 4.52 22 |

| O1a‒B1‒O2a | 109.5(19) |

| O1a‒B1‒O3a [ × 2] | 112.0(9) |

| O2a‒B1‒O3a [ × 2] | 106.2(10) |

| O3a‒B1‒O3a | 110.7(19) |

| Volume (Å3) | 1.99(5) |

| B2O4 tetrahedra | |

| B2–O1b | 1.52(3) |

| B2–O2b | 1.56(2) |

| B2–O3b | 1.54(2) |

| B2–O3c | 1.56(2) |

| Mean value | 1.54(2) |

| BVS | 4.87 22 |

| O1b‒B2‒O2b | 110.1(9) |

| O1b‒B2‒O3b | 112.2(13) |

| O1b‒B2‒O3c | 110.8(13) |

| O2b‒B2‒O3b | 108.8(11) |

| O2b‒B2‒O3c | 105.0(11) |

| O3b‒B2‒O3c | 109.8(11) |

| Volume (Å3) | 1.89(4) |

| B3O4 tetrahedra | |

| B3–O1c | 1.52(3) |

| B3–O2c | 1.55(3) |

| B3–O3d [ × 2] | 1.51(2) |

| Mean value | 1.52(3) |

| BVS | 5.14 22 |

| O1c‒B3‒O2c | 111(2) |

| O1c‒B3‒O3d [ × 2] | 110.9(11) |

| O2c‒B3‒O3d [ × 2] | 111.7(9) |

| O3d‒B3‒O3d | 100.0(19) |

| Volume (Å3) | 1.80(4) |

| X Sites | |

| BVS for O2− at X1 | 1.81, 20 1.98 21 |

| BVS for O2− at X2 | 0.95, 20 0.95 21 |

| BVS for O2− at X3 | 1.29, 20 1.36 21 |

Further least-squares cycles had done with SHELXL to compare convergence of iterations with twinned

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Space group

Refined

4.2 Long-range order in superstructure

Sizes of A2 triangles in the refined

![Figure 4:

Geometry of coordination polyhedra around A2 sites and their sequence. For presentation of atoms please refer to the caption on Figure 3. (a) A2- and B-site atoms in the region 0 ≤ x ≤ 0.5, 0 ≤ y ≤ 0.5, 0 ≤ z ≤ 1 and their first neighbors. (b) Projection of A2aO6 – B2O4 – A2cO6 array approximately in [

2

‾

$\overline{2}$

1 0]. Tilt of B2O4 around direction normal to c and difference in sizes of A2O6 pentagonal pyramids are visible. Dotted lines are for eye-guide.](/document/doi/10.1515/zkri-2024-0103/asset/graphic/j_zkri-2024-0103_fig_004.jpg)

Geometry of coordination polyhedra around A2 sites and their sequence. For presentation of atoms please refer to the caption on Figure 3. (a) A2- and B-site atoms in the region 0 ≤ x ≤ 0.5, 0 ≤ y ≤ 0.5, 0 ≤ z ≤ 1 and their first neighbors. (b) Projection of A2aO6 – B2O4 – A2cO6 array approximately in [

Formation of bond with X1 site O2− reduced charge of A2c site Pb2+ for the other Pb2+ – O2− bonds and caused expansion of the pentagonal pyramid. This effect lengthened A2c – O2c distance more than the others since this elongation only rotated B3O4 tetrahedron and had no effect on cell-edge lengths of the host structure. For this reason, B3O4 tetrahedron was rotated 13° (approx.) on mirror normal to c with respect to B1O4 tetrahedron (Figure 5).

![Figure 5:

[0 0

1

‾

$\overline{1}$

] projection of the A2 and O3 triangles with X sites and BO4 tetrahedra on xy-plane. For presentation of atoms please refer to the caption on Figure 3. The unit cell boundaries are shown as dashed lines. Red and gray triangles are for eye-guide.](/document/doi/10.1515/zkri-2024-0103/asset/graphic/j_zkri-2024-0103_fig_005.jpg)

[0 0

Since no superstructure had been reported on apatite-type Pb9(PO4)6 which had no channel anion, 25 occurrence of the long-range order should be attributed to a fractional number on X in the formula A12A23(BO4)3X0.5. No superstructure is necessary for the composition when channel site oxide anions are located on every other A2 layers whether the site is split or not. In such a case sizes of A2 triangles will have a ‘ – large – small – ’ sequence no matter how different they are. This sequence did not occur in the real structure, probably because the host structure with such order can not be accomplished without large distortions of (PO4)3− complex anions. Long-range periodicity was necessary to vary the sizes of A2 triangles in the host structure only by rotations of rigid BO4 units with least distortion.

4.3 Positions of X anions

The X1 site was located near the small A2c triangle, and either one of two X1 site positions [at z = 0.471(7) & 0.529(7)] was occupied by oxide anion in every unit cell. The X2 and X3 sites were close to the middle-size A2b triangle with similarly low occupancy factors, they were not equidistant from the A2b triangle though. Remaining two positions equivalent to the X1 site in the parent structure (near A2a at z = 0) were vacant. The edge length (Å) of the largest A2a triangle in PPO [4.359(3)] was close to those in Pb9(PO4)6 [4.311(3)] and Pb5(PO4)3Cl [OP-4; 4.3493(11)], indicating that the A2a-site Pb2+ were enough separated from each other to stand for repulsion among themselves including clouds of presumable 6s2 lone electron pairs. Estimated bond-valence sum (BVS) for O2− at the center of the A2a triangle (1.0) is, as expected, far smaller than its formal valence. In contrast, the A2c triangle was far smaller (−25 % in areas) and have an appropriate size to accommodate O2− near its center. Estimated BVS values for O2− at the X1 site position were 1.8 20 or 2.0, 21 in other words the X1 site position suite to O2− in the channel. So we consider shrinkage of A2c triangle due to attraction from X1 site O2− as the main cause of the superstructure in the following discussion.

Calculated BVS values for O2− at the center of A2c triangle were 1.9 20 or 2.1. 21 Based on the BVS values after ref. 20] and discussions on spatial distribution of stereoactive 6s2 electron orbitals of Pb2+ 13 , 14 we can deduce a consideration as follows. Stereoactive 6s2 electron orbitals of Pb2+ are pointing inside of the channel and these orbitals push O2− apart from the triangle along <001>. Directions of 6s2 orbitals might be canted toward the opposite side, but their repulsion is still strong enough to compete against a demand to make the A2c triangle further smaller to accomplish ideal Pb2+ – O2− bond lengths. In this sense size of the A2c triangle is the possible minimum in the structure and the BVS values for O2− are still smaller than 2.0 at both the X1 site and the center of the triangle. On the other hand, the BVS values after ref. 21] implies that an arrangement of atoms around the X1 site position is quite reasonable. However, we have to notice that the A2c triangle had no reason to shrink other than attraction from the X1-site O2−. This implies that the ideal position for O2− is a center of regular A2c triangle and that the A2c triangle is a little smaller than necessary. This leads a consideration such that the O2− is pushed out from the triangle plane but keep Pb2+ – O2− distance ideal to use up its charge. In other words, repulsion among 6s2 orbitals is not strong enough to compete against a demand to make Pb2+ – O2− distance ideal. We can not conclude whether the size of the A2c triangle is a possible minimum for Pb2+ triangle or not, but presence of repulsion between 6s2 electron clouds and outer shell electrons of O2− in the channel is very likely. This repulsion also explains the positions of X2 and X3 sites. Calculated BVS for O2− at the center of A2b triangle was 1.3 but both X2 and X3 sites were located out from the triangle plane due to repulsion from 6s2 orbitals at A2b site.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nittetsu Mining Co., Japan for their continuous financial support over the years.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author. CIF file can be obtained from CCDC website on quoting the deposition number CSD 2363464.

References

1. Elliott, J. C.; Wilson, R. M.; Dowker, S. E. P. Apatite Structures. Adv. X-Ray Anal. 2002, 45, 172–181.Search in Google Scholar

2. White, T. J.; ZhiLi, D. Structural Derivation and Crystal Chemistry of Apatites. Acta Crystallogr. B 2003, 59, 1–16; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0108768102019894.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Baikie, T.; Mercier, P. H. J.; Elcombe, M. M.; Kim, J.; Le Page, Y.; Mitchell, L. D.; White, T. J.; Whitfield, P. S. Triclinic Apatites. Acta Crystallogr. B 2007, 63, 251–256; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0108768106053316.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Pasero, M.; Kampf, A. R.; Ferraris, C.; Pekov, I. V.; Rakovan, J.; White, T. J. Nomenclature of the Apatite Supergroup Minerals. Eur. J. Mineral. 2010, 22, 163–179; https://doi.org/10.1127/0935-1221/2010/0022-2022.Search in Google Scholar

5. Okudera, H. Relationships Among Channel Topology and Atomic Displacements in the Structures of Pb5(BO4)3Cl with B = P (Pyromorphite), V (Vanadinite), and as (Mimetite). Am. Mineral. 2013, 98, 1573–1579; https://doi.org/10.2138/am.2013.4417.Search in Google Scholar

6. Matsuura, M.; Okudera, H. Structures of Ca5(VO4)3Cl and Ca4.78(1)Na0.22(PO4)3Cl0.78: Positions of Channel Anions and Repulsion on the Anion in Apatite-type Compounds. Acta Crystallogr. B 2022, 78, 789–797; https://doi.org/10.1107/s2052520622008095.Search in Google Scholar

7. Mackie, P. E.; Elliott, J. C.; Young, R. A. Monoclinic Structure of Synthetic Ca5(PO5)5Cl, Chlorapatite. Acta Crystallogr. B 1972, 28, 1840–1848; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0567740872005114.Search in Google Scholar

8. Merker, v. L.; Wondratschek, H. Der Oxypyromorphit Pb10(PO4)6O und der Ausschnitt Pb4P2O9-Pb3(PO4)2 des Systems PbO-P2O5. Z. Anorg. Allgem. Chem. 1960, 306, 25–29; https://doi.org/10.1002/zaac.19603060105.Search in Google Scholar

9. Wondratschek, H. Untersuchungen zur Kristallchemie der Blei-Apatite (Pyromorphite). Neues Jahrbuch Miner. Abh. 1963, 99, 113–160.Search in Google Scholar

10. Krivovichev, S. V.; Engel, G. The Crystal Structure of Pb10(PO4)6O Revisited: the Evidence of Superstructure. Crystals 2023, 13, 1371–1383; https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst13091371.Search in Google Scholar

11. Krivovichev, S. V.; Burns, P. C. Crystal Chemistry of Lead Oxide Phosphates: Crystal Structures of Pb4O(PO4)2, Pb8O5(PO4)2 and Pb10(PO4)6O. Z. Kristallogr. 2003, 218, 357–365; https://doi.org/10.1524/zkri.218.5.357.20732.Search in Google Scholar

12. Okudera, H.; Masubuchi, Y.; Kikkawa, S.; Yoshiasa, A. Structure of Oxide Ion-Conducting Lanthanum Oxyapatite, La9.33(SiO4)6O2. Solid State Ionics 2005, 176, 1473–1478; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssi.2005.02.014.Search in Google Scholar

13. Kim, J. Y.; Fenton, R. R.; Hunter, B. A.; Kennedy, B. J. Powder Diffraction Studies of Synthetic Calcium and Lead Apatites. Aust. J. Chem. 2000, 53, 679–686; https://doi.org/10.1071/ch00060.Search in Google Scholar

14. Kampf, A. R.; Housley, R. M. Fluorphosphohedyphane, Ca2Pb3(PO4)3F, the First Apatite Supergroup Mineral with Essential Pb and F. Am. Mineral. 2011, 96, 423–429.10.2138/am.2011.3586Search in Google Scholar

15. Okada, Y.; Tokumaru, Y. Precise Determination of Lattice Parameters and Thermal Expansion Coefficient of Silicon between 300 and 1500 K. J. Appl. Phys. 1984, 56, 314–320; https://doi.org/10.1063/1.333965.Search in Google Scholar

16. Kihara, K. An X-Ray Study of the Temperature Dependence of the Quartz Structure. Eur. J. Mineral. 1990, 2, 63–77; https://doi.org/10.1127/ejm/2/1/0063.Search in Google Scholar

17. Becker, P. J.; Coppens, P. Extinction within the Limit of Validity of the Darwin Transfer Equations. I. General Formalisms for Primary and Secondary Extinction and Their Application to Spherical Crystals. Acta Crystallogr. A 1974, 30, 129–147; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0567739474000337.Search in Google Scholar

18. Sakakura, T.; Kamoshita, M.; Iguchi, H.; Wang, J.; Ishizawa, N. Apatite-type SrPr4(SiO4)3O. Acta Crystallogr. E 2010, 66, i68; https://doi.org/10.1107/s1600536810033349.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Sheldrick, G. M. Crystal Structure Refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. C 2015, 71, 3–8; https://doi.org/10.1107/s2053229614024218.Search in Google Scholar

20. Krivovichev, S. V.; Brown, I. D. Are the Compressive Effects of Encapsulation an Artifact of the Bond Valence Parameters? Z. Kristallogr. 2001, 216, 245–247; https://doi.org/10.1524/zkri.216.5.245.20378.Search in Google Scholar

21. Gagné, O. C.; Hawthorne, F. C. Comprehensive Derivation of Bond-Valence Parameters for Ion Pairs Involving Oxygen. Acta Crystallogr. B 2015, 71, 562–578; https://doi.org/10.1107/s2052520615016297.Search in Google Scholar

22. Brown, I. D.; Altermatt, D. Bond-valence Parameters Obtained from a Systematic Analysis of the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database. Acta Crystallogr. B 1985, 41, 244–247; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0108768185002063.Search in Google Scholar

23. Momma, K.; Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for Three-Dimensional Visualization of Crystal, Volumetric and Morphology Data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2011, 44, 1272–1276; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0021889811038970.Search in Google Scholar

24. Sudarsanan, K.; Young, R. A.; Wilson, A. J. C. The Structures of Some Cadmium ‘apatites’ Cd5(MO4)3X. I. Determination of the Structures of Cd5(VO4)3I, Cd5(PO4)3Br, Cd5(AsO4)3Br and Cd5(VO4)3Br. Acta Crystallogr. B 1977, 33, 3136–3142; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0567740877010413.Search in Google Scholar

25. Hata, M.; Marumo, F.; Iwai, S.; Aoki, H. Structure of a Lead Apatite Pb9(PO4)6. Acta Crystallogr. B 1980, 36, 2128–2130; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0567740880008096.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Obituary

- Obituary for Hartmut Bärnighausen

- Micro Review

- Bismuth as reactive and non-reactive flux medium for the synthesis and crystal growth of intermetallics

- Organic and Metalorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Racemic and unusual enantiomeric crystal forms of N-cycloalkyl-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamides and their biological activity

- Inorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Lead phosphate oxyapatite, Pb10(PO4)6O, with c-double superstructure

- A novel microporous uranyl silicate prepared by high temperature flux technique

- The Grubbs catalyst – dichlorido(1-(2,6-diethylphenyl)-3,5,5-trimethyl-3-phenylpyrrolidin-2-ylidene)-({5-nitro-2-[(propan-2-yl)oxy]phenyl}methylidene)ruthenium(II) – some observations on the crystallography and stereochemistry of a racemic mimic pair

- Thermal decomposition of copper(II) hydroxide and hydroxocarbonates according to X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy in operando

- New calcium perrhenates: synthesis and crystal structures of Ca(ReO4)2 and K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Obituary

- Obituary for Hartmut Bärnighausen

- Micro Review

- Bismuth as reactive and non-reactive flux medium for the synthesis and crystal growth of intermetallics

- Organic and Metalorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Racemic and unusual enantiomeric crystal forms of N-cycloalkyl-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamides and their biological activity

- Inorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Lead phosphate oxyapatite, Pb10(PO4)6O, with c-double superstructure

- A novel microporous uranyl silicate prepared by high temperature flux technique

- The Grubbs catalyst – dichlorido(1-(2,6-diethylphenyl)-3,5,5-trimethyl-3-phenylpyrrolidin-2-ylidene)-({5-nitro-2-[(propan-2-yl)oxy]phenyl}methylidene)ruthenium(II) – some observations on the crystallography and stereochemistry of a racemic mimic pair

- Thermal decomposition of copper(II) hydroxide and hydroxocarbonates according to X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy in operando

- New calcium perrhenates: synthesis and crystal structures of Ca(ReO4)2 and K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O