Abstract

The use of liquid bismuth as reactive or inert flux medium for the growth of intermetallic phases is reviewed. Besides systematic phase analytical studies with respect to discovery of new phases, large, mm-sized single crystals allow direction dependent physical property studies.

1 Introduction

Reactions in low-melting metal fluxes are one of the important synthesis’s techniques for intermetallic phases. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 Depending on the reaction pathway, both reactive (the so-called self-flux technique) and inert flux growth have been intensively used. The most prominent low-melting flux media are tin, aluminum, gallium, indium, lead and zinc; also, eutectic mixtures have been used. The growth of mm sized single crystals is important for direction dependent physical property studies, since crystalline intermetallic solids are inherently anisotropic.

Experimental prerequisites for an efficient use of a metal as flux medium are a sufficient solubility of the reactants, good wettability (this is especially the case for tin, thus its broad use as solder material) and complete removal of the excess flux after the growth procedure. The common techniques are high-temperature centrifugation and etching with an appropriate solvent (diluted hydrochloric acid, acetic acid or glacial acetic acid/hydrogen peroxide mixtures). The different experimental facets are summarized in a review article. 3

In the early reviews, 1 , 2 , 3 only few flux growth experiments with bismuth have been summarized. This was a bit astonishing, since the low melting temperature of bismuth (544 K 12 ) and the good solubility of many metals are promising for flux growth experiments. Although most of the T-Bi (T = transition metal) and RE-Bi (RE = rare earth element) phase diagrams are reported in the relevant Handbooks, 13 , 14 several binaries have only recently been synthesized (bismuth flux growth or high-pressure syntheses) and structurally characterized. Selected examples are MnBi2, 15 FeBi2, 16 , 17 CoBi3, 18 NiBi3, 19 , 20 the NiAs superstructure variants Ni0.6Pt0.4Bi, Ni0.7Pd0.2Bi, Mn0.99Pd0.01Bi, Ni0.9Bi, and Ni0.79Pd0.08Bi, 21 CuBi and Cu11Bi7, 22 , 23 MoBi2, 24 Rh3Bi14, 25 IrBi3 26 and IrBi4, 27 PtBi2, 28 Nd3Bi7, Sm3Bi7 29 and HoBi. 30 During the whole article we keep the classical formula of the compounds, although in many cases the transition metals are more electronegative and carry a negative charge, e.g., the iridide character of Bi4Ir. 27

Besides the supplementary work on the binary phase diagrams, many ternary intermetallic bismuthides have been synthesized in a manifold of exploratory experiments, especially in the many RE-T-Bi phase diagrams. 31 The flux-assisted syntheses of intermetallics have large advantages as compared to simple arc-melting synthesis, since the low boiling temperature of bismuth of 1,883 K 12 can result in severe evaporation losses, thus changing the starting composition of the sample, often leading to multi-phase mixtures. This is especially the problem when introducing the high-melting transition metals (e.g., iridium with a melting point of 2,683 K 12 ) and this might result in multi-phase products.

Besides pure bismuth, eutectic mixtures find application. This is mostly the case for low-melting tin/bismuth alloys that can be used for soldering applications 32 or as fusible alloy fluxes for fire alarms and sprinkler systems. The most prominent textbook example for low-melting alloys is Wood’s metal (50 % Bi, 25 % Pb, 12.5 % Sn, 12.5 % Cd) with a melting temperature around 70 °C. 33 These materials are not in the scope of this micro review. We solely focus on the synthesis of intermetallic phases.

Meanwhile many examples for bismuth flux synthesis are known for compounds (binaries and ternaries) forming with many metals of the whole Periodic Table. The present overview gives a broader list of feasible synthesis and demonstrates the large success of bismuth flux growth experiments. The relevant literature was carefully reviewed; however, should a reference be missing, it is unintentional.

2 Experimental conditions

For the exact experimental conditions, we refer to the original work. Herein we summarize the most important experimental parameters for bismuth flux synthesis. Table 1 gives an overview on many bismuth flux growth experiments listing the starting compositions, the temperature sequence for the flux growth procedure and the crucible material used. Not all crystal growth conditions are documented in detail in the original works. Sometimes, work on physical properties only mentions that the crystals were obtained from flux experiments and the experimental conditions remain unclear. 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97

Examples of binary and ternary compounds grown in liquid bismuth. RT = room temperature. In those cases where cooling rates stopped at high temperature, the flux was decanted, removed in a centrifuge or the sample was quenched; for details see the original work. In some cases, heating and cooling rates were only given as slow and fast. In cases were only an excess of bismuth is mentioned for the starting composition, this is marked by + x.

| Compounds | Sample composition (atomic ratio) |

Typical preparation conditions (T in K, time in h) |

Crucible material |

Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-flux syntheses (bismuth as reactive flux) – binaries | |||||

| NiBi3 | Ni:Bi 1:10 | RT → 1,423 (fast), 2 h at 1,423, 1,423 → 673 (5 K h−1) |

SiO2 | 19 | |

| Rh3Bi14 | Rh:Bi 3:20 | RT→870 (10 K h−1), 24 h at 870, 870 → 590 (6 K h−1), 120 h at 590 |

SiO2 | 25 | |

| PtBi2 | Pt:Bi 1:20 | RT → 673 (100 K h−1), 96 h at 673, 673 → 573 (0.25 K h−1) |

Canfield type | 28 | |

| RE3Bi7 (RE = Nd, Sm) | RE:Bi 1:100 | RT → 1,273 (200 K h−1), 5 h at 1,273, 1,273 → 973 (50 K h−1), 973 → 673 (5 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 29 | |

| HoBi | Ho:Bi 1:9 | RT → 1,273 (fast), 3 h at 1,273, 1,273 → 1,173 (33 K h−1), 1,173 → 673 (5 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 30 | |

| Self-flux syntheses (bismuth as reactive flux) – ternaries | |||||

| MgNi2Bi4 | Mg:Ni:Bi 1:2:10 | RT → 1,073 (65 K h−1), 30 h at 1,073, 1,073 → 773 (8 K h−1), 24 h at 773, 773 → 623 (5 K h−1), |

Al2O3 | 34 | |

| AE5Ti12Bi19+x (AE = Sr, Ba) | AE:Ti:Bi 1:1:10 | RT → 1,273 (200 K h−1), 48 h at 1,273, 1,273 → 773 (5 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 35 | |

| Mn8Zn1.8Bi7.4 | Mn:Zn:Bi 1:0.5:10 | RT → 1,173 (293 K h−1), 24 h at 1,173, 1,173 → 623 (6 K h−1) |

SiO2 | 36 | |

| RMg2Bi2 (R = Ca, Eu, Yb) | R:Mg:Bi 1:4:6 | RT → 1,173 (110 K h−1), 1,173 → 1,123 (50 K h−1), 1,123 → 1,023 (10 K h−1), 1,023 → 923 (4 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 37 | |

| SrNi0.17Bi2 | Sr:Ni:Bi 1:1:3 | RT → 1,273 (200 K h−1), 48 h at 1,273, 1,273 → 773 (5 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 38 | |

| CaTi3Bi4 | Ca:Ti:Bi 1:1:20 | RT → 1,273 (200 K h−1), 48 h at 1,273, 1,273 → 773 (5 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 38 | |

| BaMn2Bi2 | Ba:Mn:Bi 1:2:10 | RT → 1,273 (200 K h−1), 15 h at 1,273, 1,273 → 688 (5 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 39 | |

| EuMg2Bi2 | Eu:Mg:Bi 1:4:12 | RT → 1,173 (180 K h−1), 5 h at 1,173, 1,173 → 1,073 (100 K h−1), 1,073 → 923 (3 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 40 | |

| REMg2Bi2 (RE = Sm, Eu, Yb) | RE:Mg:Bi 1:25:5 | RT → 1,273 (98 K h−1), 20 h at 1,273, 1,223 → 973 (2 K h−1) |

stainless-steel | 41 | |

| REGe2−xBi

x

(RE = Y, Pr, Nd, Sm, Gd–Tm, Lu) |

RE:Ge:Bi 1:2:8 | RT → 1,273 (200 K h−1), 20 h at 1,273, 1,273 → 873 (10 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 42 | |

| TbTi3Bi4 | Tb:Ti:Bi 2:3:20 | RT → 1,373 (200 K h−1), 12 h at 1,373, furnace change, 873 → 673 (1 K h−1) |

Canfield type | 43 | |

| RE2–xTi6+xBi9 (RE = Tb–Tm, Lu) | RE:Ti:Bi 2:3:20 | RT → 1,373 (200 K h−1), 12 h at 1,373, 1,373 → 873 (2 K h−1) |

Canfield type | 43 | |

| CaTBi2 (T = Mn, Cu) | Ca:T:Bi 1:1:6 | RT → 1,173 (fast), 1,173 → 673 (4 K h−1) | Al2O3 | 44 | |

| SmMnBi2 | Sm:Mn:Bi 1:1:10 | RT → 1,373 (108 K h−1), 10 h at 1,373, 1,373 → 773 (5 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 45 | |

| AMnBi2 (A = Sr, Eu) | A:Mn:Bi 1:1:9 | RT → 1,273 (fast), 10 h at 1,273, 1,273 → 673 (2 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 46 | |

| CaMn2Bi2 | Ca:Mn:Bi 1:2:10 | RT → 1,273 (180 K h−1), 48 h at 1,273, 1,273 → 673 (6 K h−) |

Al2O3 | 47 | |

| EuZnBi2 | Eu:Zn:Bi 1:5:10 | RT → 1,273 (fast), 10 h at 1,273, 1,273 → 673 (2 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 46 , 48 , 49 | |

| ScNiBi | Sc:Ni:Bi 1:1:12 | RT → 1,420 (113 K h−1), 72 h at 1,420, 1,420 → 920 (2 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 50 | |

| RENi1−xBi2+y (RE = La–Nd, Sm, Gd–Dy) |

RE:Ni:Bi 1:0.8:2 + x | RT → 1,273 (fast), 1,273 → 773 (7 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 51 | |

| CeTBi2 (T = Ni, Cu, Ag) | Ce:T:Bi 1:1:2 + x | RT → 1,273 (fast), 48 h at 1,273, 1,273 → 923 (0.5 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 52 | |

| U3T3Bi4 (T = Ni, Rh) | U:T:Bi 1:2:10 | RT → 1,423 (fast), 4 h at 1,423, 1,423 → 923 (5 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 53 | |

| Ca3T4Bi8 (T = Pd, Pt) | Ca:T:Bi 3:4:12 | RT → 1,173 (100 K h−1), 5 h at 1,173, 1,173 → 1,023 (3 K h−1), 1,023 → 1,073 (50 K h−1), 1 h at 1,073, 1,073 → 923 (3 K h−1), 923 → 973 (50 K h−1), 1 h at 973, 973 → 823 (3 K h−1), 823 → 873 (50 K h−1), 1 h at 873, 873 → 723 (3 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 54 | |

| LaPd1−xBi2 | La:Pd:Bi 1:1:12 | RT → 1,170 (fast), 10 h at 1,170, 1,170 → 770 (slow) |

Al2O3 | 55 | |

| CePd1−xBi2 | Ce:Pd:Bi 1:1:12 | RT → 1,173 (fast), 10 h at 1,173, 1,173 → 773 (5 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 56 | |

| REPd1−xBi2 (RE = La, Ce, Nd) | RE:Pd:Bi 1:1:10 | RT → 1,273 (fast), 10 h at 1,273, 1,273 → 973 (5 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 57 | |

| HoPdBi | Ho:Pd:Bi 1:1:15 | RT → 1,373 (slow), 24 h at 1,373, 1,373 → 1,173 (1 K h−1), 12 h at 1,173, 1,173 → 823 (1 K h−1), |

Al2O3 | 58 | |

| HoPdBi | Ho:Pd:Bi 1:1:1 + x | RT → 1,423 (fast), 36 h at 1,423, 1,423 → 773 (3 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 59 | |

| ErPdBi | Er:Pd:Bi 1:1:1 + x | RT → 1,423 (fast), 36 h at 1,423, 1,423 → 773 (3 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 60 | |

| ScPtBi | Sc:Pt:Bi 1:1:15 | RT → 1,420 (50 K h−1), 24 h at 1,420, 1,420 → 970 (1 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 61 | |

| NdPtBi | Nd:Pt:Bi 1:1:15 | RT → 1,473 (fast), 48 h at 1,473, 1,473 → 823 (4 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 62 | |

| GdPtBi | Gd:Pt:Bi 1:1:9 | RT → 1,473 (100 K h−1), 12 h at 1,473, 1,473 → 873 (2 K h−1) |

Ta | 63 | |

| TbPtBi | Tb:Pt:Bi 1:1:9 | RT → 1,273 (fast), 12 h at 1,273, 1,273 → 873 (5 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 64 | |

| LuPtBi | Lu:Pt:Bi 1:1:10 | RT → 1,423 (75 K h−1), 24 h at 1,423, 1,423 → 923 (2 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 65 | |

| CaAuBi | Ca:Au:Bi 1:1:10 | RT → 1,223 (fast), 5 h at 1,223, 1,223 → 673 (2.5 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 66 | |

| REAuBi2 (RE = La–Nd, Sm) | RE:Au:Bi 1:1:20 | RT → 1,123 (fast), 12 h at 1,123, 1,123 → 823 (3 K h−1), 24 h at 823 |

Al2O3 | 67 | |

| AnAuBi2 (An = U, Th) | An:Au:Bi 1:3:20 | RT → 1,323 (fast), 8 h at 1,323, 1,323 → 1,073 (83 K h−1), 1,073 → 723 (5 K h−1) |

Al2O3 | 68 | |

| Bismuth as inert flux medium for binaries | |||||

| GeP | Ge:P:Bi 1:2:2 | RT → 1,223 (fast), 96 h at 1,223, 1,223 → 773 (4 K h−1), 773 → 573 (fast), 24 h at 573 |

SiO2 | 69 | |

| GaSe | Ga:Se:Bi 1:1:4 | RT → 1,173 (fast), 12 h at 1,173, 1,173 → 720 (3 K h−1) |

SiO2 | 70 | |

| Mn2Au | Mn:Au:Bi 7:1:12 | RT → 1,023 (fast), 12 h at 1,023, 1,023 → 923 (fast), 24 h at 923, 923 → 743 (slowly) |

Al2O3 | 71 | |

| Bismuth as inert flux medium for ternary phosphides | |||||

| ScRh6P4 | Sc:Rh:P:Bi 1:2:2:30 | RT → 770 (20 K h−1), 24 h at 770, 770 → 1,320 (50 K h−1), 100 h at 1,320, 1,320 → 970 (2 K h−1), 970 → 570 (4 K h−1) |

SiO2 | 72 | |

| YbRh6P4 | Yb:Rh:P:Bi 1:2:2:60 | RT → 770 (20 K h−1), 24 h at 770, 770 → 1,320 (50 K h−1), 100 h at 1,320, 1,320 → 970 (2 K h−1), 970 → 570 (4 K h−1) |

SiO2 | 72 , 73 | |

| LuRh6P4 | Lu:Rh:P:Bi 3:2:2:30 | RT → 770 (20 K h−1), 24 h at 770, 770 → 1,320 (50 K h−1), 100 h at 1,320, 1,320 → 970 (2 K h−1), 970 → 570 (4 K h−1) |

SiO2 | 72 | |

| ScIrP | Sc:Ir:P:Bi 1:1:1:30 | RT → 770 (50 K h−1), 24 h at 770, 770 → 1,370 (50 K h−1), 100 h at 1,370, 1,370 → 970 (2 K h−1), 970 → 570 (4 K h−1) |

SiO2 | 74 | |

| La4Rh8P9 | La:Rh:P:Bi 4:8:9:30 | RT → 770 (50 K h−1), 24 h at 770, 770 → 1,370 (50 K h−1), 100 h at 1,370, 1,370 → RT (2 K h−1) |

SiO2 | 75 | |

| Sm4Rh13P9 | Sm:Rh:P:Bi 1:2:2:30 | RT → 770 (50 K h−1), 24 h at 770, 770 → 1,270 (2 K h−1), 168 h at 1,270, 1,270 → RT (2 K h−1) |

SiO2 | 76 | |

| Sm4Ir13P9 | Sm:Ir:P:Bi 1:1:1:30 | RT → 770 (50 K h−1), 24 h at 770, 770 → 1,370 (2 K h−1), 168 h at 1,370, 1,370 → RT (2 K h−1) |

SiO2 | 76 | |

| Gd4Ir13P9 | Gd:Ir:P:Bi 1.3:2:2:30 | RT → 770 (50 K h−1), 24 h at 770, 770 → 1,370 (2 K h−1), 168 h at 1,370, 1,370 → RT (2 K h−1) |

SiO2 | 76 | |

| Yb4Ir13P9 | Yb:Ir:P:Bi 3:1:3:30 | RT → 770 (50 K h−1), 24 h at 770, 770 → 1,370 (2 K h−1), 168 h at 1,370, 1,370 → RT (2 K h−1) |

SiO2 | 76 | |

| RE7Ir17P12 (RE = Y, Gd, Tb, Dy, Ho) |

RE:Ir:P:Bi 1:2:2:60 | RT → 770 (20 K h−1), 24 h at 770, 770 → 1,320 (50 K h−1), 100 h at 1,320, 1,320 → 970 (2 K h−1), 970 → 570 (4 K h−1) |

SiO2 | 77 | |

| RE5Ir19P12 (RE = Sc, Y, La–Nd, Sm–Lu) |

RE:Ir:P:Bi 1:2:2:60 | RT → 770 (20 K h−1), 24 h at 770, 770 → 1,320 (50 K h−1), 100 h at 1,320, 1,320 → 970 (2 K h−1), 970 → 570 (4 K h−1) |

SiO2 | 78 | |

| Lu3Ir7P5 | Lu:Ir:P:Bi 1:2:2:60 | RT → 770 (50 K h−1), 24 h at 770, 770 → 1,370 (50 K h−1), 100 h at 1,370, 1,370 → 970 (2 K h−1), 970 → 570 (4 K h−1) |

SiO2 | 79 | |

| Bismuth as inert flux medium for ternary arsenides | |||||

| Mg3Si6As8 | Mg:Si:As:Bi 3:6:8:50 | RT → 1,123 (50 K h−1), 140 h at 1,123 | carbonized SiO2 | 80 | |

| EuCo2As2 | Eu:Co:As:Bi 2:2:2:30 | RT → 1,223 (fast), 192 h at 1,223 | carbonized SiO2 | 81 | |

| RECo2As2 (RE = La, Ce, Pr, Nd) | RE:Co:As:Bi 1:2:2:30 | RT → 1,173 (fast), 240 h at 1,173 | SiO2 | 82 | |

| LaCo2As2 | La:Co:As:Bi 1:2:2:30 | RT → 1,173 (fast), 240 h at 1,173 | SiO2 | 83 | |

| RECo2−xAs2 (RE = Pr, Nd) | RE:Co:As:Bi 1:2:2:30 | RT → 1,173 (fast), 240 h at 1,173 | SiO2 | 84 | |

| R2Co12As7 (R = Ca, Y, Ce–Nd, Sm–Yb) | R:Co:As:Bi 2:12:7:30 | RT → 1,223 (fast), 192 h at 1,223 | SiO2 | 85 | |

| CeRh2As2 | Ce:Rh:As:Bi 1:2:2:30 | RT → 1,423 (113 K h−1), 1,423 → 973 (2.7 K h−1) | SiO2 | 86 | |

| REIr2As2 (R = La–Nd) | RE:Ir:As:Bi 1:2:2:30 | RT → 770 (20 K h−1), 24 h at 770, 770 → 1,320 (20 K h−1), 1,320 → RT (2 K h−1) |

SiO2 | 87 | |

| Bismuth as inert flux medium for ternary tetrelides | |||||

| CeRh2Ge2 | Ce:Rh:Ge:Bi 1:2:2:25 | RT → 1,320 (520 K h−1), 1 h at 1,320, 1,320 → 570 (8 K h−1), 570 → 530 (2 K h−1) |

SiO2 | 88 | |

| CeRh6Ge4 | Ce:Rh:Ge:Bi 1:5:4:50 | RT → 1,320 (520 K h−1), 4 h at 1,320, 1,320 → 770 (6 K h−1), 770 → 520 (7 K h−1) |

SiO2 | 88 | |

| Ce2Rh3Ge5 | Ce:Rh:Ge:Bi 2:1:2:25 | RT → 1,320 (520 K h−1), 1 h at 1,320, 1,320 → 570 (8 K h−1), 570 → 530 (2 K h−1) |

SiO2 | 89 | |

The most important prerequisite for the synthesis of intermetallic compounds 98 concerns the purity of the starting elements as well as pure inert gas (e.g., dry argon) and inert crucible materials. Since bismuth (as oxophilic element) is used as majority component in the flux experiments, its potential surface oxidation/hydrolysis might be a source for oxygen contamination. Thus, bulk bismuth pieces should be used instead of bismuth powder. Also, crucible materials should not strictly be considered as totally inert; e.g., under special conditions, silica tubes and also alumina crucibles can be a possible oxygen source. 99 , 100

The standard crucible material used for the bismuth flux experiments is alumina. Besides, also silica tubes, carbonized silica tubes (usually the carbon coating is obtained by thermal decomposition of acetone), hexagonal boron nitride and tantalum have been used (see Table 1). BeO was used as crucible material for the growth of UPt3 single crystals. 1

After the applied annealing sequence, removal of the excess flux is essential in order to harvest the grown crystals. Two different separation techniques are possible. Liquid bismuth can be separated from the product crystals via centrifugation. This requires a separator. In a simple setup, the elemental mixture within the alumina crucible is usually topped with a piece of quartz wool as barrier and then sealed in an evacuated quartz tube. After the final cooling step, the hot ampoules (for the final temperatures see Table 1) are turned over and rapidly placed into a centrifuge. After mechanically breaking the tube, the crystals can be separated from the quartz wool.

A more sophisticated technique for separation is the so-called Canfield crucible setup 101 , 102 , 103 where the quartz wool is replaced by a frit-disc (www.lspceramics.com). In the commercial setup, the frit-disc separates two cylindrical crucibles. This assembled system can then be sealed in evacuated silica or tantalum ampoules. The Canfield crucible setup has meanwhile also been adapted to the synthesis of amalgams and experimental details are well documented in the original publication. 104

If the samples are completely cooled to room temperature, dissolution of the remaining flux proceeds chemically. The flux can be acid etched with diluted hydrochloric acid, with nitric acid or mixtures with hydrogen peroxide. For pnictides, also 1:1 mixtures of H2O2 (35 %)/glacial acetic acid were used. The degree of acidity that can be used depends on the stability of the product crystals.

The experimental conditions for the growth of Rh3Bi14 crystals were slightly different. 25 Rhodium and bismuth were mixed in an atomic ratio of 3:20 and pressed to a pellet. The latter was arc-melted under argon for homogenization and subsequently sealed in an evacuated quartz tube. The ingot was topped with a quartz wool filter. The experimental setup was similar to the one reported by Boström and Hovmöller 105 for the growth of Mn3Ga5 crystals. For the annealing sequence we refer to Table 1.

Crystals that have been separated from the flux by centrifugation might contain a residual bismuth coating on the surface. In those cases, acid etching for cleaning the surface is mandatory. A bismuth coating might hamper contact formation for resistivity measurements. Furthermore, bismuth is the element with the highest intrinsic diamagnetism (−280 × 10−6 emu mol−1). 106 Residual bismuth coatings on crystals might thus falsify the property measurements.

Some of the bismuthides listed in Table 1 contain a second metal with a low melting temperature, e.g., Mg/Bi, Zn/Bi or Cd/Bi. In such cases, an alloy instead of the pure metals might serve as fluxing agent.

Table 2 gives a short overview on the crystal size (edge lengths) of selected compounds grown in liquid bismuth. The comparatively large size of some crystals allows reliable direction dependent physical property studies. Although well shaped single crystals have minimum surface when compared to polycrystalline pieces or powders, several of the grown bismuthide crystals are still moisture sensitive and were mostly kept under inert conditions.

Crystal sizes (mm) obtained for some selected bismuthides and related phases under bismuth flux conditions. Some crystal sizes were estimated from the photos made on graph paper.

| Compound | Size | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| GaSe | 15 × 5 × 0.5 | 70 |

| NiBi3 | 2 × 0.2 × 0.2 | 19 |

| PtBi2 | 7 × 5 × 5 | 28 |

| HoBi | 4 × 3 × 3 | 30 |

| ScNiBi | 1.2 × 1.0 × 0.8 | 50 |

| LaNi0.84Bi2.04 | 10 × 10 × 1.5 | 51 |

| LaPd0.85Bi2 | 5 × 5 × 0.5 | 55 |

| ScPtBi | 6 × 3 × 3 | 61 |

| YbRh6P4 | 0.04 × 0.04 × 0.75 | 72 |

3 Selected examples

Metal flux growth of intermetallic compounds is an important topic when searching for new materials. The enormous potential for different classes of functional materials has recently been reviewed in an article worth reading by Paul Canfield. 102 Bismuth fluxes are another piece of the mosaic in this field. The recent results are summarized in the following.

3.1 Element crystals

The growth of black phosphorus crystals has been known for a long time; however, the reported experimental conditions were manifold, i.e., high-pressure application, reactions in the presence of mercury and also the bismuth flux. 107 , 108 , 109 , 110 , 111 , 112 An experimental hindrance is the non-solubility of red phosphorus in liquid bismuth. Baba et al. developed a completely closed bismuth flux setup which allows conversion of red to white phosphorus and finally the crystallization of black phosphorus. Crystals were obtained in needle-, film- and platelet-shape. The film-shaped ones had edge lengths of up to 500 µm. The availability of high-quality crystals of black phosphorus initiated broad studies on its physical properties and potential applications (transistors, photonics, optoelectronics, catalysis or batteries). 113 , 114

3.2 Ternary bismuthides grown under self-flux conditions

The largest family of compounds discussed in the present micro review concerns ternary phases of the A-T-Bi systems (A = alkaline earth, rare earth or actinoid metal; T = transition metal) which were prepared under self-flux conditions, i.e., bismuth acts as a reactive flux and is incorporated in the product phase. The known phases and their experimental conditions for crystal growth are summarized in Table 1; some selected crystal sizes are given in Table 2. In the following we shortly summarize the most remarkable properties of the A x T y Biz phases.

Crystals of MgNi2Bi4 form as a kind of matted agglomerate. 34 Selected needles form with 1 mm length. Resistivity measurements of MgNi2Bi4 show metallic behavior and this is corroborated by its Pauli paramagnetism.

Self-flux conditions were used for the ternary calcium bismuthides CaMnBi2, 44 CaMn2Bi2, 47 equiatomic CaAuBi 66 and Ca3T4Bi8 with T = Pd and Pt. 54 Of all flux experiments summarized herein, the growth of the Ca3T4Bi8 crystals had the most complex temperature profile. A sawtooth-shaped profile with four steps was chosen for the cooling process with slow cooling rates of 3 K h−1 and re-annealing by 50 K (at 50 K h−1) after each 150 K cooling step (the complete annealing sequence is given in Table 1).

Titanium forms a broader series of bismuth-rich phases A5Ti12Bi19+x with A = Sr, Ba and Eu. 35 The x values range from 0.5 to 1.0. The most interesting phase in this family is the solid solution Sr5−δEu δ Ti12Bi19+x, where strontium is partially substituted by divalent europium. Samples were obtained for δ = 2.4 and 4.0. The divalent ground state of europium (4f 7 configuration) was confirmed by magnetic susceptibility measurements.

Mn8Zn1.8Bi7.4 is a bit unique in the family of ternary bismuthides. 36 It forms with two different transition metals and was discovered during explorative phase analytical work in the Mn–Zn–Bi system. Mn8Zn1.8Bi7.4 crystallizes in the form of long (up to 1 mm) intergrown needles. The manganese substructure shows long-range ferromagnetic ordering with a sharp transition at TC = 185 K.

Single crystals of EuMg2Bi2 were studied with respect to their magnetic properties. 37 , 40 , 41 The direction dependent susceptibility measurements show an antiferromagnetic transition at TN = 8.2 K. The 1.9 K magnetization isotherms exhibit a notable anisotropy. Saturation of the europium magnetic moment with H parallel to the c axis deserves a larger external field. The saturation moment in both directions is close to the expected value of 7 µB for Eu2+.

BaMn2Bi2 crystals were grown as large platelets with up to 1 cm edge length. 39 Resistivity measurements show semiconducting behavior with a small band gap of 6 meV. The magnetic substructure of BaMn2Bi2 exhibits antiferromagnetic ordering at the comparatively high Néel temperature of TN ≈ 400 K. The c axis is the easy axis of magnetization. Single crystals were also grown for the potassium substituted solid solution Ba1−xK x Mn2Bi2. Due to the high volatility of potassium, the maximum reaction temperature was 100 K lower than for the parent compound. The potassium-for-barium substitution induces a semiconductor-metal transition.

The ternary compounds REBi x Ge2−x (RE = Y, Pr, Nd, Sm, Gd–Tm, Lu) structurally derive from the ZrSi2 type structure. 42 The Bi/Ge mixed occupancies classify them as solid solutions. The bismuth content in these phases is only low. A typical composition refined from single crystal X-ray diffractometer data is PrBi0.31Ge1.63. The germanides REBi x Ge2−x with the paramagnetic rare earth elements all order antiferromagnetically at low temperatures with the highest Néel temperature of TN = 23 K observed for the gadolinium compound.

TbTi3Bi4 is a really remarkable bismuthide. 43 The titanium atoms form kagome networks. Precise direction dependent magnetic susceptibility measurements show antiferromagnetic ordering below 24 K. The Néel temperature is well expressed in the measurement parallel to [100]. The magnetization isotherm at 1.8 K fully corroborates the antiferromagnetic ground state. A pronounced metamagnetic transition with a first saturation plateau at around 1/3Msat is observed for H parallel [100] along with substantial hysteresis. Rotation of the crystal to align the three crystallographic axes with the external magnetic field shows a shift of the critical field.

The bismuthides RET1−xBi2 with ZrCuSi2 related structures have thoroughly been studied. 51 , 52 The cerium containing members are the most interesting ones in this series. The highest magnetic ordering temperature was observed for CeCuBi2 (TN = 11.3 K). 52 The magnetization isotherm at 2 K shows a pronounced anisotropy. The c axis is the easy axis of magnetization. Above a critical field of ∼27 kOe CeCuBi2 shows multistep metamagnetism and reaches a saturation moment of 1.75 µB Ce atom−1 above 43 kOe. CePd1−xBi2 and NdPd1−xBi2 order antiferromagnetically at the lower Néel temperatures of TN = 6 and 4 K, respectively, but again with strongly anisotropic behavior. 56 , 57 LaPd1−xBi2 shows a superconducting transition below 2.1 K. 55

Single crystals of the MgAgAs type phases (so-called half-Heusler phases) HoPdBi, 58 , 59 ErPdBi, 60 ScPtBi, 61 NdPtBi, 62 GdPtBi, 63 TbPtBi 64 and LuPtBi 65 were obtained by self-flux reactions and thoroughly studied with respect to their magnetic and transport properties. An interesting feature of these phases is the interplay of long-range magnetic ordering and superconductivity, e.g., TN = 1.9 K and TC = 0.7 K for HoPdBi. 58 The magnetic structure of HoPdBi was determined from neutron diffraction data and revealed a propagation vector 1/2 1/2 1/2. Similar behavior was observed for ErPdBi (TN = 1.06 K and TC = 1.22 K). 60 Magnetotransport studies of ScPtBi show signature of a chiral magnetic anomaly in agreement with the non-centrosymmetric crystal structure. 61

The NdPtBi magnetic structure was determined from single-crystal (2 × 1 × 1 mm3) neutron diffraction data. 62 The Néel temperature is TN = 2.18 K and an ordered magnetic moment of 1.78 µB Nd atom−1 was determined. The magnetic structure is of the AFM-I type with ferromagnetically ordered planes that are alternating antiferromagnetically along [100]. GdPtBi is a 9 K antiferromagnet which shows a sharp transition in the muon-spin resonance data. 63 Contrarily, the antiferromagnetic transition for TbPtBi (TN = 3.4 K) is broad, although single crystalline material was used. 64

Crystals of the REAuBi2 bismuthides were grown for the RE = La, Ce, Pr, Nd and Sm members. 67 The paramagnetic ones order antiferromagnetically at low temperatures with the highest Néel temperature of TN = 13.6 K observed for CeAuBi2. The remarkable feature is the 2 K magnetization behavior of CeAuBi2 which is highly anisotropic. The easy magnetization is along the c axis. In c direction CeAuBi2 shows a pronounced metamagnetic transition which sets in at a critical field of ∼60 kOe. CeAuBi2 exhibits a narrow hysteresis and saturates at the comparatively high value of 1.85 µB Ce atom−1, comparable to CeCuBi2 discussed above. Also, PrAuBi2 and NdAuBi2 show metamagnetic transitions, but less pronounced. UAuBi2 orders ferromagnetically at TC = 22.5 K. 68 Again, the c axis is the easy axis of magnetization and UAuBi2 shows a large magnetocrystalline anisotropy. Such details can only be deduced from precise single crystal data.

3.3 Ternary rare earth phosphides

Besides the use of iodine as mineralizer and salt fluxes, tin is the standard flux agent for the crystal growth of phosphides, especially for the large family of ternary rare earth transition metal phosphides. 3 , 11 , 115 , 116 A detailed summary of experimental details (starting compositions, annealing sequences etc.) is given in reference 3. Besides tin also lead is frequently used as flux. A change of the flux agent can pave the way to unusual compounds. A recent example is PbP7. 117 , 118

So far, only few examples of bismuth flux grown phosphides are known. 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 The examples (Table 1) all comprise ternary phosphides of the high melting inert transition metals rhodium and iridium. These are easily activated within the flux and well-shaped single crystals of many phosphides can be grown. ScRh6P4 forms larger blocks while isotypic YbRh6P4 forms large rods with up to 750 µm length. 72 , 73

The probably most remarkable flux grown phosphide is La4Rh8P9 which exhibits the unusual diphosphenide unit P22− with 208 pm P–P distance besides P3− phosphide anions. 75 La4Rh8P9 is Pauli paramagnetic. The differently charged phosphorus species were well resolved in the 31P solid state NMR spectrum. The P22− units show side-on coordination to the rhodium atoms within the complex [Rh8P9]δ− polyanionic network.

Three parameters need to be considered for the flux growth experiments of the phosphides: (i) due to the high reactivity and vapor pressure of phosphorus, the sample annealing proceeds in two steps (Table 1) in order to avoid a two vigorous reaction and bursting of the tubes, (ii) the samples with the less reactive iridium often have slightly higher maximal annealing temperatures and (iii) care should be taken, since the product sample can contain trace amounts of white phosphorus (complete workup in a hood is recommended).

3.4 Ternary rare earth and related arsenides

One of the early examples for the growth of ternary arsenide single crystals from liquid bismuth is DyNi4As2. 119 The starting sample composition was Dy:Ni:As:Bi = 2:6:2:10. The reaction was performed in a silica tube (RT→1,143 K at 10 K h−1; 120 h at 1,143 K followed by cooling to 873 K at 2 K h−1). The DyNi4As2 crystals were simply isolated mechanically from the bismuth flux. The detailed reaction conditions of many other arsenide flux growth experiments are summarized in Table 1.

The recent flux growth experiments on arsenides all focused on high crystal quality for physical property studies. The ternary system Mg–Si–As was unexplored. Bismuth flux growth experiments yielded the new arsenide Mg3Si6As8 which crystallizes with a new non-centrosymmetric structure type. 80 Mg3Si6As8 is a semiconductor with a direct band gap around 2 eV. Unfortunately, Mg3Si6As8 shows no nonlinear optical activity.

The arsenides RECo2As2 (RE = La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Eu) 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 were thoroughly studied with respect to their magnetic properties. Larger single crystals allowed for direction dependent measurements. The bismuth flux growth experiments revealed some remarkable features. The flux is not completely inert. Precise single-crystal X-ray diffraction experiments revealed the refined compositions La0.97Bi0.03Co1.91As2 and Ce0.95Bi0.05Co1.83As2 for the lanthanum and cerium containing crystals. 82 It seems that the rare earth sites in the ThCr2Si2 type structure for the larger rare earth elements can partially be substituted by bismuth. Thus, any flux grown crystal should be studied at least by EDX, in order to check for a potential inclusion of the flux. Another important feature of the RECo2–xAs2 arsenides concerns the formation of vacancies on the cobalt sites. 82 , 84

LaCo2As2 is a good example for the importance of the correctly chosen flux medium for crystal growth. LaCo2As2 can easily be prepared in polycrystalline form from the elements by a diffusion-controlled synthesis at high temperature (1,250 K). Standard flux growth experiments with tin were not successful. 120 The bismuth flux growth works, however, small quantities of bismuth were detected on the lanthanum site. 83 The cobalt substructure of the bismuth flux grown samples shows ferromagnetic ordering at TC = 200 K.

The whole series of RE2Co12As7 arsenides is accessible by bismuth flux growth experiments. 85 The striking representatives are Ce2Co12As7, Eu2Co12As7 and Yb2Co12As7 which exhibit mixed valence behavior. The cobalt substructures of the RE2Co12As7 arsenides show ferromagnetic ordering at comparatively high Curie temperatures in the range of 100–140 K, while the rare earth magnetic ordering proceeds in the low-temperature regime.

The standard flux growth synthesis of CeRh2As2 showed small compositional differences in the product crystals that influence the physical properties. Most recently a new horizontal configuration for a bismuth-based flux growth of CeRh2As2 crystals was proposed by Chajewski et al. 86 This really remarkable experiment runs with a three-part ampoule in a two-zone horizontal furnace with three different temperature regimes: (i) high-temperature regime (1,423–1,293 K), (ii) medium-temperature regime (1,273–1,163 K) and (iii) low-temperature regime (1,133–1,043 K). The growth process lasts 15 days and produces the so far best quality CeRh2As2 crystals. For further examples of flux growth in horizontal configuration we refer to a review by Yan et al. 121

3.5 Rare earth transition metal tetrelides

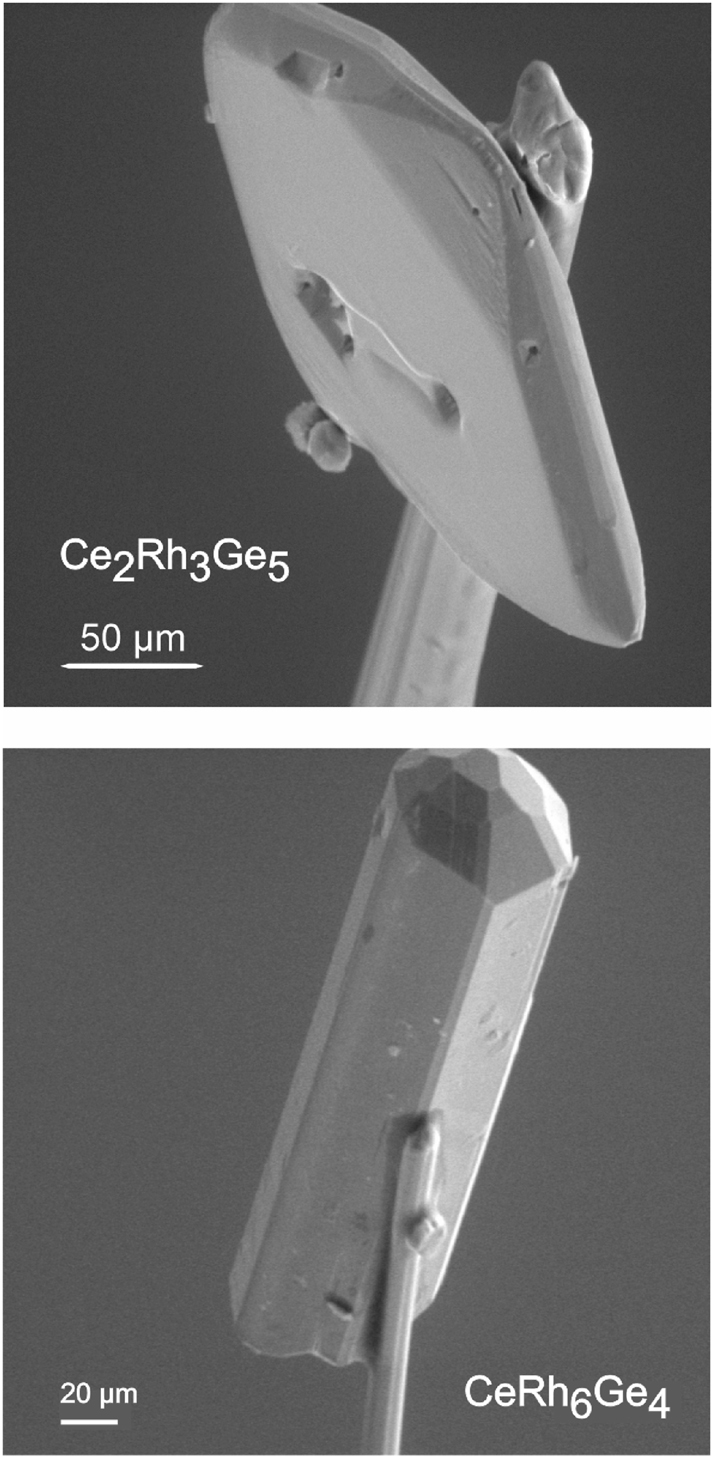

The classical bismuth flux synthesis starting from the elements was successful for the germanides CeRh6Ge4, CeRh2Ge2 88 and Ce2Rh3Ge5 89 (for the annealing sequence we refer to Table 1). Selected single crystals of Ce2Rh3Ge5 89 and CeRh6Ge4 88 mounted on glass fibers are shown in Figure 1.

All other tetrelides were obtained from arc-melted precursor compounds that were recrystallized from liquid bismuth. The flux growth experiments were performed in evacuated silica ampoules. Although bismuth acts as an inert flux during these experiments, severe attack of the silica ampoules was observed for some of the syntheses. Reacting powder of a precursor sample with the initial composition ‘HoRh6Sn4’ in liquid bismuth resulted in well-shaped crystals of Ho3Rh9Si2Sn3, a quaternary compound that adopts a new structure type. 122 Later on, the targeted syntheses from the elements via arc-melting led to the complete series of silicide stannides RE3Rh9Si2Sn3 with RE = Y, Sm and Gd–Lu in quantitative yield.

Similar phase analytical studies with a sample of the initial composition ‘SmRh6Sn4’ in liquid bismuth yielded the quaternary compound SmRh4SiSn. 123 Again, later targeted syntheses produced the series RERh4SiSn with RE = Y, Nd, Sm and Gd–Lu. Attack of the ampoule under bismuth flux conditions led to the silicon incorporation. These quaternary phases can be considered as ordered version of the YRh4Ge2 type (space group Pnma). In extension to the work on the quaternary phases, also ScIr4Si2 and the series of RERh4Si2 silicides with RE = Sc, Y and Tb–Lu was synthesized. Summing up, experiments that went wrong due to ampoule attack led to the discovery of three larger series of new intermetallic compounds.

The initial crystal growth study on CeRh6Ge4 88 started from the elements. Further phase analytical work resulted in the isotypic compounds RERh6Si4 (RE = La, Nd, Tb, Dy, Er, Yb) 124 and RERh6Ge4 (RE = Y, La, Pr, Nd, Sm–Lu). 125 All these tetrelides were obtained as polycrystalline samples via arc-melting of the elements. The crystal growth procedure for the silicides (with RE = La, Nd and Yb 124 ) was different from CeRh6Ge4. Here, arc-melted RERh6Si4 pellets were ground, mixed with 2 g of bismuth shot and sealed in evacuated silica ampoules. The latter were heated to 1,220 K within 2 h and the temperature was kept for 12 days, followed by cooling to room temperature at a rate of 3 K h−1. The germanide crystals (with RE = La, Pr, Sm, Gd and Ho 125 ) were grown similar to the cerium compound. The most interesting tetrelide of this family is CeRh6Ge4 88 which orders ferromagnetically below 2.5 K. This initiated further work, 126 , 127 classifying CeRh6Ge4 as a quantum critical heavy-fermion ferromagnet.

Ongoing crystal growth experiments also helped to crystallize quite complex silicides. The new phases RE12Rh60Si39 (RE = Nd, Tb, Yb) 128 are isotypic with the silicide Ce6Rh30Si19.3 (space group P63/m, Pearson code hP112). 129 The crystal growth process started with arc-melted ingots of the starting compositions ‘RERh4Si2’ (around 300 mg) which were powdered and mixed with 2 g of bismuth shot. The educts were sealed in carbonized silica tubes and subjected to the following annealing sequence: (i) RT→1,220 K within 2 h, (ii) 12 h at 1,220 K and (iii) cooling to room temperature at a rate of 3 K h−1. The flux was finally dissolved in a 1:1 mixture of glacial acetic acid and H2O2 (35 %).

Nd16Rh73Ge49 crystals (new structure type) 130 were obtained from an arc-melted ‘NdRh6Ge4’ precursor sample that was powdered and mixed with a six-fold molar amount of bismuth. The experimental conditions were: (i) carbonized silica tube, (ii) RT→1,320 K within 2 h, (iii) 20 h at 1,320 K, (iv) cooling to 720 K at a rate of 3 K h−1 and (v) 1:1 HOAc/H2O2. The complex germanide Ce9Ir37Ge25 131 was grown under comparable conditions: (i) ‘CeIr4Ge3’ precursor sample (∼500 mg + 3 g Bi), (ii) SiO2 tube, (iii) RT→1,300 K within 2 h, (iv) 10 d at 1,300 K, (v) quenching and (vi) 1:1 HOAc/H2O2. These are first examples for a presumably large family of complex tetrelides.

3.6 Binaries under inert flux conditions

Single crystals of semiconducting GeP can be grown from liquid bismuth (Table 1). 69 After the crystal growth procedure a final annealing step for 24 h at 573 K is important in order to convert the remaining white phosphorus to red phosphorus (!). While residual red phosphorus sublimes from the crystal surfaces, remaining bismuth traces can be dissolved by a treatment with a dilute HCl/H2O2 mixture. GeP crystals form on the larger µm scale allowing high-quality data collections for structure determination.

Liquid bismuth also served as inert flux for the growth of GaSe crystals (Table 1). 70 The sizes of the obtained crystals are strongly depending on the temperature profile. While most studies use a linear decrease of temperature in the final crystal growth step, for GaSe, an oscillating temperature profile (similar to the temperature profile discussed above for the Ca3T4Bi8 phases 54 ) helped to strongly increase the crystal size. The decisive parameter influencing the number and size of crystals is the number of crystal nuclei formed during the cooling process. It seems that the oscillating temperature profile can minimize the nucleus number. Thus, many crystal growth procedures might be optimized using modified temperature profiles in the cooling regime.

Single crystals of antiferromagnetic Mn2Au were grown from a starting composition Mn: Au: Bi = 7:1:12 (Table 1). 71 Larger block-shaped crystals with edge lengths up to 3 mm were obtained. Mn2Au shows hydrolysis resistance. Bismuth flux residues on the crystal surface were acid etched with a 2:1 mixture of HNO3/HCl for less than 2 min.

3.7 Suboxides

Besides pure bismuth intermetallics, also some suboxides (still with metal-metal bonding) were grown from reactions in a bismuth flux. The ɛ-TiO polymorph, 132 which is isotypic with ɛ-TaN is one of the striking examples. For single crystal growth Bi, Bi2O3 and Ti were mixed with a Ti:O molar ratio of 1.0:0.9 and elemental bismuth was used in excess as fluxing agent. The elements were placed in a h-BN crucible which was subsequently sealed in a stainless-steel tube. The sample was heated to 1,173 K at a rate of 7.5 K min−1 and kept at that temperature for 2 h followed by cooling to 773 K at a rate of 10 K h−1. After furnace cooling, the excess bismuth flux was removed by treatment with 4 M HNO3. The needle-shaped ɛ-TiO crystals had edge lengths up to 900 µm.

Ti8Bi9O0.25 133 was obtained from Ti (0.85 mmol), TiO2 (0.125 mmol) and Bi (1.5 mmol) using a tantalum crucible that was inserted into a stainless-steel ampoule (sealed with a stainless-steel cap). After rapid heating (400 K h−1) to 1,073 K, the temperature was kept for 10 h and subsequently lowered to 723 K at a rate of 10 K h−1, followed by quenching. Ti8Bi9O0.25 single crystals could be isolated from the crushed sample. The oxygen is located in a tetrahedral Ti4 site.

Comparable reaction conditions were applied for the syntheses of Ti3Zn3O x with x = 1.07 and 1.23. 134 The two different starting compositions Ti: Zn: ZnO: Bi of 0.8:0.4:0.8:2.0 and 0.45:0.3:0.75:1.95 and a slightly different temperature profile for the crystal growth procedure led to the crystals with different oxygen content. The obtained crystals have edge lengths around 60 µm. Further flux growth experiments led to incorporation of small amounts of bismuth into the product crystals, Ti8BiO7, 135 and the solid solutions Ti12−δGa x Bi3–xO10, 136 Ti8(Sn x Bi1–x)O7 and Ti11.17(Sn0.85Bi0.15)3O10. 137

3.8 Binaries as flux medium

The use of binary Ni2Bi is at first sight an unusual flux medium, however, it is bismuth based. The Ni2Bi has repeatedly been used for crystal growth experiments of the rare earth-based quaternary boride carbides RENi2B2C. 138 , 139 , 140 , 141 , 142 , 143 This flux has several advantages: (i) its melting temperature of ∼1,373 K is well below the decomposition temperature of the RENi2B2C phases and (ii) Ni2Bi is a self-flux and does not introduce further elements into the synthesis. In a typical experiment for crystal growth of YNi2B2C, 138 a polycrystalline sample is prepared by arc-melting. The product button is then placed into an alumina crucible and covered with an equal mass of Ni2Bi. The flux growth proceeds under flowing argon: (i) fast heating to 1,763 K and subsequent slow cooling to 1473 K at a rate of 10 K h−1. Platelets of YNi2B2C can finally be broken out of the solidified melt. The family of RENi2B2C boride carbides has intensively been studied with respect to the interplay of superconductivity and long-range magnetic ordering.

3.9 Miscellaneous

The bismuthides Ca11Ga x Bi10−x (x ≈ 0.8), Ca11Ga x Bi10−x (x ≈ 1.1), Yb11Ga x Bi10−x (x ≈ 0.7) and Yb11In x Bi10−x (x ≈ 1.8) 144 derive from the tetragonal Ho11Ge10 type structure 145 and can be considered as solid solutions with partially mixed occupied sites. The crystal growth experiments start with Ca(Yb):Bi:In(Ga) atomic ratios of 1:1:4 using alumina as crucible material. The heating sequence was: (i) RT→1,073 K at 100 K h−1, (ii) 24 h at 1,073 K and (iii) 1,073 K→773 K at 5 K h−1. Although gallium (303 K) and indium (429 K) both have lower melting points than bismuth (544 K), 12 during the first heating step, all three elements melt and one can assume a mixed flux situation.

The metastable fibrous phase Bi21.1Mn20–xCo x was crystallized under bismuth self-flux conditions. 146 Crystal growth attempts with starting compositions Mn:Co:Bi 10–x:x:90 with x values of 0, 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 were performed using alumina as crucible material. The mixtures were rapidly heated to 1,423 K, kept at 1,423 K for 5 h and then cooled to 663 K at a rate of 152 K h−1. After dwelling for 1 h at 663 K, the samples were cooled to 553 K at a rate of 1 K h−1 followed by centrifugation. The product was an agglomerate of matted needles with up to 2.5 mm length. The striking crystal chemical feature of Bi21.1Mn20–xCo x is the pseudo-pentagonal symmetry. This is structurally closely related to Ni25Bi28 147 and Ni8Bi8S. 148

The bismuth self-flux technique is not limited to intermetallics. An interesting example concerns the topological insulator Bi2TeI. 149 Although broad property studies were performed for this telluride iodide, high-quality single crystals were not available. Ryu et al. systematically investigated the crystal growth conditions for Bi2TeI and obtained good results with the bismuth self-flux technique. The starting composition for flux growth was Bi2+xTeI with x ≥ 0.5. The elements were sealed in a quartz tube under 2 mbar argon pressure. The ampoule was heated to 1,123 K, kept at that temperature for 72 h followed by cooling to 823 K at rates between 0.5 and 2 K h−1. Single crystals up to 5 mm edge lengths could be obtained. The grown crystals were exfoliated with 3 M Scotch® tape to remove surface contaminations prior to the property studies.

A final example concerns indium arsenide quantum dots. 150 This is not a classical crystal growth experiment. For those systems bismuth can serve as surfactant for modifying the morphology and optical properties. Such surface layers are grown using bismuth fluxes.

4 Summary and outlook

The present micro review underpins the powerful use of bismuth fluxes for the crystal growth of different intermetallic compounds. A manifold of new phases has been discovered in the last 20 years. Although many phases are known, there is still work to do. Many of the ternary systems are far from being completely understood with respect to the phase relations; only few complete isothermal sections known. Besides the help in phase analytical work, crystal growth is indispensable for direction dependent property studies. Especially the really rarely used sawtooth-shaped temperature profiles hold great potential. Another scarcely used topic concerns mixed metal fluxes. A recent example is EuZnBi2, 46 , 48 , 49 where an excess of zinc and bismuth (Eu:Zn:Bi 1:5:10) is used for flux growth.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The author has accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved the submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: Not relevant. The corresponding author is able to think and act independently.

-

Conflict of interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: All data is listed within the manuscript or available from the cited references.

References

1. Canfield, P. C.; Fisk, Z. Phil. Mag. B 1992, 65, 1117–1123; https://doi.org/10.1080/13642819208215073.Search in Google Scholar

2. Canfield, P. C.; Fisher, I. R. J. Cryst. Growth 2001, 225, 155–161; https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-0248(01)00827-2.Search in Google Scholar

3. Kanatzidis, M. G.; Pöttgen, R.; Jeitschko, W. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 6996–7023; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.200462170.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Thomas, E. L.; Millican, J. N.; Okudzeto, E. K.; Chan, J. Y. Comm. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 27, 1–39; https://doi.org/10.1080/02603590600666215.Search in Google Scholar

5. Canfield, P. C. Solution Growth of Intermetallic Single Crystals: A Beginner’s Guide. In Properties and Applications of Complex Intermetallics; Belin-Ferré, E., Ed.; World Scientific: Singapore, 2009; pp. 93–112. Chapter 2.10.1142/9789814261647_0002Search in Google Scholar

6. Canfield, P. C. Phil. Mag 2012, 92, 2398–2400; https://doi.org/10.1080/14786435.2012.694675.Search in Google Scholar

7. Phelan, W. A.; Menard, M. C.; Kangas, M. J.; McCandless, G. T.; Drake, B. L.; Chan, J. Y. Chem. Mater. 2012, 24 (3), 409–420; https://doi.org/10.1021/cm2019873.Search in Google Scholar

8. Gille, P.; Grin, Yu., Eds. Crystal Growth of Intermetallics; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2018.10.1515/9783110496789Search in Google Scholar

9. Latturner, S. E. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 40–48; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00483.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Kliemt, K.; Peters, M.; Feldmann, F.; Kraiker, A.; Tran, D.-M.; Rongstock, S.; Hellwig, J.; Witt, S.; Bolte, M.; Krellner, C. Crystal Res. Techn. 2020, 55, 1900116 (9 pages); https://doi.org/10.1002/crat.201900116.Search in Google Scholar

11. Wang, J.; Yox, P.; Kovnir, K. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 186 (7 pages); https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2020.00186.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Emsley, J. The Elements; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1999.Search in Google Scholar

13. Moffat, W. G., Ed. The Handbook of Binary Phase Diagrams; Genium Publishing Corporation: New York, 1984.Search in Google Scholar

14. Massalski, T. B. Binary Alloy Phase Diagrams, Vols. 1 and 2; American Society for Metals: Ohio, 1986.Search in Google Scholar

15. Walsh, J. P. S.; Clarke, S. M.; Puggioni, D.; Tamerius, A. D.; Meng, Y.; Rondinelli, J. M.; Jacobsen, S. D.; Freedman, D. E. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 3083–3088; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.9b00385.Search in Google Scholar

16. Fredrickson, D. C. ACS Cent. Sci. 2016, 2, 773–774; https://doi.org/10.1021/acscentsci.6b00332.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Walsh, J. P. S.; Clarke, S. M.; Meng, Y.; Jacobsen, S. D.; Freedman, D. E. ACS Cent. Sci. 2016, 2, 867–871; https://doi.org/10.1021/acscentsci.6b00287.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Tencé, S.; Janson, O.; Krellner, C.; Rosner, H.; Schwarz, U.; Grin, Yu.; Steglich, F. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2014, 26, 396701 (6 pages).10.1088/0953-8984/26/39/395701Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Zhu, X.; Lei, H.; Petrovic, C.; Zhang, Y. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 86, 024527 (5 pages); https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.86.024527.Search in Google Scholar

20. Silva, B.; Luccas, R. F.; Nemes, N. M.; Hanko, J.; Osorio, M. R.; Kulkarni, P.; Mompean, F.; García-Hernández, M.; Ramos, M. A.; Vieira, S.; Suderow, H. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 88, 184508 (5 pages); https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.88.184508.Search in Google Scholar

21. Gibson, Q. D.; Wen, D.; Lin, H.; Zanella, M.; Daniels, L. M.; Robertson, C. M.; Claridge, J. B.; Alaria, J.; Dyer, M. S.; Rosseinsky, M. J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202403670 (8 pages); https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202403670.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Clarke, S. M.; Amsler, M.; Walsh, J. P. S.; Yu, T.; Wang, Y.; Meng, Y.; Jacobsen, S. D.; Wolverton, C.; Freedman, D. E. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 5276–5285; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b01418.Search in Google Scholar

23. Guo, K.; Akselrud, L.; Bobnar, M.; Burkhardt, U.; Schmidt, M.; Zhao, J. T.; Schwarz, U.; Grin, Y. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 5620–5624; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201700712.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Altman, A. B.; Tamerius, A. D.; Koocher, N. Z.; Meng, Y.; Pickard, C. J.; Walsh, J. P. S.; Rondinelli, J. M.; Jacobsen, S. D.; Freedman, D. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 214–222; https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.0c09419.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Gu, Q. F.; Krauss, G.; Grin, Yu.; Steurer, W. J. Solid State Chem. 2007, 180, 940–948; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2006.12.020.Search in Google Scholar

26. Heise, M.; Rasche, B.; Isaeva, A.; Baranov, A. I.; Ruck, M.; Schäfer, K.; Pöttgen, R.; Eufinger, J. P.; Janek, J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 7344–7348; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201402244.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Isaeva, A.; Ruck, M.; Schäfer, K.; Rodewald, U.C.; Pöttgen, R. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 885–889; https://doi.org/10.1021/ic502205k.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Shipunov, G.; Kovalchuk, I.; Piening, B. R.; Labracherie, V.; Veyrat, A.; Wolf, D.; Lubk, A.; Subakti, S.; Giraud, R.; Dufouleur, J.; Shokri, S.; Caglieris, F.; Hess, C.; Efremov, D. V.; Büchner, B.; Aswartham, S. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2020, 4, 124202 (8 pages); https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevmaterials.4.124202.Search in Google Scholar

29. Ovchinnikov, A.; Makongo, J. P. A.; Bobev, S. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 7089–7092; https://doi.org/10.1039/c8cc02563k.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Fente, A.; Suderow, H.; Vieira, S.; Nemes, N. M.; García-Hernández, M.; Bud’ko, S. L.; Canfield, P. C. Solid State Commun. 2013, 171, 59–63; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssc.2013.07.027.Search in Google Scholar

31. Mar, A. Bismuthides. In Handbook On the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths; Gschneidner, K. A.Jr; Bünzli, J. C. G.; Pecharsky, V. K., Eds.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, Vol. 36, 2006; pp. 1–82. Chapter 227; https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-1273(06)36001-1.Search in Google Scholar

32. Trodler, J. Solder Materials in Electronics. In Applied Inorganic Chemistry; Pöttgen, R.; Jüstel, T.; Strassert, C. A., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Vol. 1, 2023; pp. 192–206. Chapter 2.5; https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110733143-012.Search in Google Scholar

33. Riedel, E.; Janiak, C. Anorganische Chemie, 10th ed.; De Gruyter: Berlin, 2022.10.1515/9783110694444Search in Google Scholar

34. Hertz, M. B.; Baumbach, R. E.; Latturner, S. E. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 3452–3458; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b03196.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Ovchinnikov, A.; Bobev, S. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 1266–1274.Search in Google Scholar

36. Marzano, L.; Uddin, M. S.; Larson, J. T.; Latturner, S. E. Cryst. Growth Des. 2024, 24, 2462–2467; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.cgd.3c01416.Search in Google Scholar

37. May, A. F.; McGuire, M. A.; Singh, D. J.; Custelcean, R.; JellisonJr.G. E. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 11127–11133; https://doi.org/10.1021/ic2016808.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Ovchinnikov, A.; Bobev, S. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 3459–3470; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b02881.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

39. Saparov, B.; Sefat, A. S. J. Solid State Chem. 2013, 204, 32–39; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2013.05.010.Search in Google Scholar

40. Marshall, M.; Pletikosić, I.; Yahyavi, M.; Tien, H. J.; Chang, T. R.; Cao, H.; Xie, W. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 129, 035106 (10 pages); https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0035703.Search in Google Scholar

41. Ramirez, D.; Gallagher, A.; Baumbach, R.; Siegrist, T. J. Solid State Chem. 2015, 231, 217–222; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2015.08.039.Search in Google Scholar

42. Zhang, J.; Hmiel, B.; Antonelli, A.; Tobash, P. H.; Bobev, S.; Saha, S.; Kirshenbaum, K.; Greene, R. L.; Paglione, J. J. Solid State Chem. 2012, 196, 586–595; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2012.07.031.Search in Google Scholar

43. Ortiz, B. R.; Zhang, H.; Górnicka, K.; Parker, D. S.; Samolyuk, G. D.; Yang, F.; Miao, H.; Lu, Q.; Moore, R. G.; May, A. F.; McGuire, M. A. Chem. Mater. 2024, 36 (16), 8002–8014.Search in Google Scholar

44. Zhang, Z.; Guo, Z.; Lin, J.; Sun, F.; Han, X.; Wang, G.; Yuan, W. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 4592–4597; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.1c03410.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

45. Krishnan, S.; Besara, T. Acta Crystallogr. B 2021, 77, 577–583; https://doi.org/10.1107/s2052520621005849.Search in Google Scholar

46. Masuda, H.; Sakai, H.; Tokunaga, M.; Yamasaki, Y.; Miyake, A.; Shiogai, J.; Nakamura, S.; Awaji, S.; Tsukazaki, A.; Nakao, H.; Murakami, Y.; Arima, T. H.; Tokura, Y.; Ishiwata, S. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1501117 (6 pages); https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1501117.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

47. Gui, X.; Finkelstein, G. J.; Chen, K.; Yong, T.; Dera, P.; Cheng, J.; Xie, W. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 8933–8937; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b01362.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

48. He, J.; Liu, B.; Ma, S.; Jin, S.; Zheng, C.; Fu, Y.; Zhu, W.; Cheng, J.; Liu, C.; Li, L.; Ji, X.; Luo, Y.; Shi, H. J. Supercond. Novel Magn. 2024, 37, 579–585; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10948-024-06704-x.Search in Google Scholar

49. Ryan, D. H. J. Supercond. Novel Magn. 2025, 38, 5 (5 pages); https://doi.org/10.1007/s10948-024-06887-3.Search in Google Scholar

50. Deng, L.; Liu, Z. H.; Ma, X. Q.; Hou, Z. P.; Liu, E. K.; Xi, X. K.; Wang, W. H.; Wu, G. H.; Zhang, X. X. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 121, 105106 (4 pages); https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4978015.Search in Google Scholar

51. Lin, X.; Straszheim, W. E.; Bud’ko, S. L.; Canfield, P. C. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 554, 304–311; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2012.11.138.Search in Google Scholar

52. Thamizhavel, A.; Galatanu, A.; Yamamoto, E.; Okubo, T.; Yamada, M.; Tabata, K.; Kobayashi, T. C.; Nakamura, N.; Sugiyama, K.; Kindo, K.; Takeuchi, T.; Settai, R.; Ōnuki, Y. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2003, 72, 2632–2639; https://doi.org/10.1143/jpsj.72.2632.Search in Google Scholar

53. Klimczuk, T.; Lee, H.-O.; Ronning, F.; Durakiewicz, T.; Kurita, N.; Volz, H.; Bauer, E. D.; McQueen, T.; Movshovich, R.; Cava, R. J.; Thompson, J. D. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 77, 245111 (6 pages); https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.77.245111.Search in Google Scholar

54. Ovchinnikov, A.; Mudring, A. V. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 9756–9766; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.2c01248.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

55. Han, F.; Malliakas, C. D.; Stoumpos, C. C.; Sturza, M.; Claus, H.; Chung, D. Y.; Kanatzidis, M. G. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 88, 144511 (6 pages); https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.88.144511.Search in Google Scholar

56. Han, F.; Wan, X.; Phelan, D.; Stoumpos, C. C.; Sturza, M.; Malliakas, C. D.; Li, Q.; Han, T. H.; Zhao, Q.; Chung, D. Y.; Kanatzidis, M. G. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 045112 (8 pages); https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.92.045112.Search in Google Scholar

57. Zhang, F. M.; Zhou, W.; Xu, C. Q.; Liu, S. W.; Zhang, J. Y.; Xia, M.; Xu, X.; Qian, B. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 782, 170–175; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.12.076.Search in Google Scholar

58. Pavlosiuk, O.; Kaczorowski, D.; Fabreges, X.; Gukasov, A.; Wiśniewski, P. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 18797 (9 pages); https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18797.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

59. Nikitin, A. M.; Pan, Y.; Mao, X.; Jehee, R.; Araizi, G. K.; Huang, Y. K.; Paulsen, C.; Wu, S. C.; Yan, B. H.; de Visser, A. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2015, 27, 275701 (7 pages); https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/27/27/275701.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

60. Pan, Y.; Nikitin, A. M.; Bay, T. V.; Huang, Y. K.; Paulsen, C.; Yan, B. H.; de Visser, A. Europhys. Lett. 2013, 104, 27001 (6 pages); https://doi.org/10.1209/0295-5075/104/27001.Search in Google Scholar

61. Pavlosiuk, O.; Jezierski, A.; Kaczorowski, D.; Wiśniewski, P. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 205127 (9 pages); https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.103.205127.Search in Google Scholar

62. Müller, R. A.; Desilets-Benoit, A.; Gauthier, N.; Lapointe, L.; Bianchi, A. D.; Maris, T.; Zahn, R.; Beyer, R.; Green, E.; Wosnitza, J.; Yamani, Z.; Kenzelmann, M. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 184432 (7 pages); https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.92.184432.Search in Google Scholar

63. Shekhar, C.; Kumar, N.; Grinenko, V.; Singh, S.; Sarkar, R.; Luetkens, H.; Wu, S. C.; Zhang, Y.; Komarek, A. C.; Kampert, E.; Skourski, Yu.; Wosnitza, J.; Schnelle, W.; McCollam, A.; Zeitler, U.; Kübler, J.; Yan, B.; Klauss, H. H.; Parkin, S. S. P.; Felser, C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2018, 115, 9140–9144; https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1810842115.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

64. Singha, R.; Roy, S.; Pariari, A.; Satpati, B.; Mandal, P. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 99, 035110 (6 pages); https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.99.035110.Search in Google Scholar

65. Hou, Z.; Wang, W.; Xu, G.; Zhang, X.; Wei, Z.; Shen, S.; Liu, E.; Yao, Y.; Chai, Y.; Sun, Y.; Xi, X.; Wang, W.; Liu, Z.; Wu, G.; Zhang, X.-X. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 235134 (9 pages); https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.92.235134.Search in Google Scholar

66. Xie, L. S.; Schoop, L. M.; Medvedev, S. A.; Felser, C.; Cava, R. J. Solid State Sci. 2014, 30, 6–10; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2014.02.001.Search in Google Scholar

67. Seibel, E. M.; Xie, W.; Gibson, Q. D.; Cava, R. J. J. Solid State Chem. 2015, 230, 318–324; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2015.07.013.Search in Google Scholar

68. Rosa, P. F. S.; Luo, Y.; Bauer, E. D.; Thompson, J. D.; Pagliuso, P. G.; Fisk, Z. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 104425 (7 pages); https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.92.104425.Search in Google Scholar

69. Lee, K.; Synnestvedt, S.; Bellard, M.; Kovnir, K. J. Solid State Chem. 2015, 224, 62–70; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2014.04.021.Search in Google Scholar

70. Chu, W.; Yang, J.; Li, L.; Zhu, X.; Tian, M. J. Cryst. Growth 2021, 562, 126088 (5 pages); https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2021.126088.Search in Google Scholar

71. Gebre, M. S.; Banner, R. K.; Kang, K.; Qu, K.; Cao, H.; Schleife, A.; Shoemaker, D. P. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2024, 8, 084413 (9 pages); https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevmaterials.8.084413.Search in Google Scholar

72. Pfannenschmidt, U.; Rodewald, U.C.; Pöttgen, R. Monatsh. Chem. 2011, 142, 219–224; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00706-011-0450-5.Search in Google Scholar

73. Ivanshin, V. A.; Gataullin, E. M.; Sukhanov, A. A.; Pfannenschmidt, U.; Pöttgen, R. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2012, 391 (4pp), 012024; https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/391/1/012024.Search in Google Scholar

74. Pfannenschmidt, U.; Rodewald, U.Ch.; Pöttgen, R. Z. Naturforsch. 2011, 66b, 205–208.10.1515/znb-2011-0214Search in Google Scholar

75. Pfannenschmidt, U.; Johrendt, D.; Behrends, F.; Eckert, H.; Eul, M.; Pöttgen, R. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 3044–3051; https://doi.org/10.1021/ic102570x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

76. Voßwinkel, D.; Pfannenschmidt, U.; Fieberg, L.; Baldauf, J. A.; Block, T.; Kösters, J.; Pöttgen, R. Z. Naturforsch. 2025, 80b. submitted for publication.Search in Google Scholar

77. Pfannenschmidt, U.; Pöttgen, R. Intermetallics 2011, 19, 1052–1058; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intermet.2011.03.016.Search in Google Scholar

78. Pfannenschmidt, U.; Rodewald, U.C.; Hoffmann, R.-D.; Pöttgen, R. J. Solid State Chem. 2011, 184, 2731–2737; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2011.07.045.Search in Google Scholar

79. Pfannenschmidt, U.; Rodewald, U. C.; Pöttgen, R. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2010, 636, 314–319; https://doi.org/10.1002/zaac.200900331.Search in Google Scholar

80. Woo, K. E.; Wang, J.; Wu, K.; Lee, K.; Dolyniuk, J. A.; Pan, S.; Kovnir, K. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1801589 (10 pages); https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201870209.Search in Google Scholar

81. Tan, X.; Fabbris, G.; Haskel, D.; Yaroslavtsev, A. A.; Cao, H.; Thompson, C. M.; Kovnir, K.; Menushenkov, A. P.; Chernikov, R. V.; Ovidiu Garlea, V.; Shatruk, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 2724–2731; https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.5b12659.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

82. Thompson, C. M.; Tan, X.; Kovnir, K.; Ovidiu Garlea, V.; Gippius, A. A.; Yaroslavtsev, A. A.; Menushenkov, A. P.; Chernikov, R. V.; Büttgen, N.; Krätschmer, W.; Zubavichus, Y. V.; Shatruk, M. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 3825–3837; https://doi.org/10.1021/cm501522v.Search in Google Scholar

83. Thompson, C. M.; Kovnir, K.; Eveland, S.; Herring, M. J.; Shatruk, M. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 5563–5565; https://doi.org/10.1039/c1cc10578g.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

84. Tan, X.; Tener, Z. P.; Shatruk, M. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 230–239; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00533.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

85. Tan, X.; Ovidiu Garlea, V.; Chai, P.; Geongzhian, A. Y.; Yaroslavtsev, A. A.; Xin, Y.; Menushenkov, A. P.; Chernikov, R. V.; Shatruk, M. J. Solid State Chem. 2016, 236, 147–158; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2015.08.038.Search in Google Scholar

86. Chajewski, G.; Szymański, D.; Daszkiewicz, M.; Kaczorowski, D. Mater. Horiz. 2024, 11, 855–861; https://doi.org/10.1039/d3mh01351k.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

87. Pfannenschmidt, U.; Behrends, F.; Lincke, H.; Eul, M.; Schäfer, K.; Eckert, H.; Pöttgen, R. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 14188–14196; https://doi.org/10.1039/c2dt31874a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

88. Voßwinkel, D.; Niehaus, O.; Rodewald, U.C.; Pöttgen, R. Z. Naturforsch. 2012, 67b, 1241–1247.10.5560/znb.2012-0265Search in Google Scholar

89. Voßwinkel, D.; Pöttgen, R. Z. Naturforsch. 2013, 68b, 301–305.10.5560/znb.2013-3015Search in Google Scholar

90. Canfield, P. C.; Thompson, J. D.; Beyermann, W. P.; Lacerda, A.; Hundley, M. F.; Peterson, E.; Fisk, Z.; Ott, H. R. J. Appl. Phys. 1991, 70, 5800–5802; https://doi.org/10.1063/1.350141.Search in Google Scholar

91. Severing, A.; Thompson, J. D.; Canfield, P. C.; Fisk, Z.; Riseborough, P. Phys. Rev. B 1991, 44, 6832–6837; https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.44.6832.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

92. Kwei, G. H.; Lawrence, J. M.; Canfield, P. C.; Beyermann, W. P.; Thompson, J. D.; Fisk, Z.; Lawson, A. C.; Goldstone, J. A. Phys. Rev. B 1992, 46, 8067–8072; https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.46.8067.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

93. Robinson, R. A.; Purwanto, A.; Kohgi, M.; Canfield, P. C.; Kamiyama, T.; Ishigaki, T.; Lynn, J. W.; Erwin, R.; Peterson, E.; Movshovich, R. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 50, 9595–9598; https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.50.9595.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

94. Ye, J.; Huang, Y. K.; Kadowaki, K.; Matsumoto, T. Acta Crystallogr. C 1996, 52, 1323–1325; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0108270195016738.Search in Google Scholar

95. Tafti, F. F.; Fujii, T.; Juneau-Fecteau, A.; René de Cotret, S.; Doiron-Leyraud, N.; Asamitsu, A.; Taillefer, L. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 87, 184504 (5 pages); https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.87.184504.Search in Google Scholar

96. Xiao, H.; Hu, T.; Liu, W.; Zhu, Y. L.; Li, P. G.; Mu, G.; Su, J.; Li, K.; Mao, Z. Q. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 97, 224511 (5 pages); https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.97.224511.Search in Google Scholar

97. Chen, J.; Li, H.; Ding, B.; Hou, Z.; Liu, E.; Xi, X.; Wu, G.; Wang, W. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2020, 116, 101902 (4 pages); https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5143990.Search in Google Scholar

98. Pöttgen, R.; Johrendt, D. Intermetallics, 2nd ed.; De Gruyter: Berlin, 2019.10.1515/9783110636727Search in Google Scholar

99. Yan, J. Q. J. Cryst. Growth 2015, 416, 62–65; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2015.01.017.Search in Google Scholar

100. Baranets, S.; Darone, G. M.; Bobev, S. Z. Kristallogr. 2022, 237, 1–26; https://doi.org/10.1515/zkri-2021-2079.Search in Google Scholar

101. Canfield, P. C.; Kong, T.; Kaluarachchi, U. S.; Jo, N. H. Phil. Mag. 2016, 96, 84–92; https://doi.org/10.1080/14786435.2015.1122248.Search in Google Scholar

102. Canfield, P. C. Rep. Progr. Phys. 2020, 83, 016501 (36 pages); https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6633/ab514b.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

103. Slade, T. J.; Canfield, P. C. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2022, 648, e202200145 (12 pages).10.1002/zaac.202200145Search in Google Scholar

104. Witthaut, K.; Prots, Yu.; Zaremba, N.; Krnel, M.; Leithe-Jasper, A.; Grin, Y.; Svanidze, E. ACS Org. Inorg. Au 2023, 3, 143–150; https://doi.org/10.1021/acsorginorgau.2c00048.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

105. Boström, M.; Hovmöller, S. J. Solid State Chem. 2000, 153, 398–403; https://doi.org/10.1006/jssc.2000.8790.Search in Google Scholar

106. Weast, R. C., Ed. Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 57th ed.; CRC Press: Cleveland, Ohio, 1974; p. 44128. Table E-122.Search in Google Scholar

107. Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, E.; Wiberg, N. Anorganische Chemie, 103 ed.; De Gruyter: Berlin, 2017.Search in Google Scholar

108. Lange, S.; Schmidt, P.; Nilges, T. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 4028–4035; https://doi.org/10.1021/ic062192q.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

109. Brown, A.; Rundqvist, S. Acta Crystallogr. 1965, 19, 684–685; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0365110x65004140.Search in Google Scholar

110. Maruyama, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Kobayashi, K.; Tanuma, S. Physica B 1981, 105, 99–102; https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4363(81)90223-0.Search in Google Scholar

111. Iwasaki, N.; Maruyama, Y.; Kurita, S.; Shirotani, I.; Kinoshita, M. Chem. Lett. 1985, 14, 119–122.10.1246/cl.1985.119Search in Google Scholar

112. Baba, M.; Izumida, F.; Takeda, Y.; Morita, A. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1989, 28, 1019–1022; https://doi.org/10.1143/jjap.28.1019.Search in Google Scholar

113. Gusmão, R.; Sofer, Z.; Pumera, M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 8052–8072; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201610512.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

114. Xu, Y.; Shi, Z.; Shi, X.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, H. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 14491–14527; https://doi.org/10.1039/c9nr04348a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

115. Pöttgen, R.; Hönle, W.; Von Schnering, H. G. Phosphides: Solid State Chemistry. In Encyclopedia of Inorganic Chemistry; King, R. B., Ed.; Wiley: New York, 2005, 2nd ed., VII; pp. 4255–4308.10.1002/0470862106.ia184Search in Google Scholar

116. Shatruk, M. Synthesis of Phosphides; Ji, H. F., Ed.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 2019, pp. 103–134. Chapter 6.Fundamentals and Applications of Phosphorus Nanomaterials, ACS Symposium Series10.1021/bk-2019-1333.ch006Search in Google Scholar

117. Schäfer, K.; Benndorf, C.; Eckert, H.; Pöttgen, R. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 12706–12710; https://doi.org/10.1039/c4dt01539h.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

118. Benndorf, C.; Hohmann, A.; Schmidt, P.; Eckert, H.; Johrendt, D.; Schäfer, K.; Pöttgen, R. J. Solid State Chem. 2016, 235, 139–144; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2015.12.028.Search in Google Scholar

119. Jeitschko, W.; Terbüchte, L. J.; Reinbold, E. J.; Pollmeier, P.; Vomhof, T. J. Less-Common Met. 1990, 161, 125–134; https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5088(90)90321-a.Search in Google Scholar

120. Marchand, R.; Jeitschko, W. J. Solid State Chem. 1978, 24, 351–357; https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4596(78)90026-9.Search in Google Scholar

121. Yan, J. Q.; Sales, B. C.; Susner, M. A.; McGuire, M. A. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2017, 1, 023402 (11 pages); https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevmaterials.1.023402.Search in Google Scholar

122. Voßwinkel, D.; Niehaus, O.; Gerke, B.; Benndorf, C.; Eckert, H.; Pöttgen, R. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2015, 641, 238–246.10.1002/zaac.201400458Search in Google Scholar

123. Voßwinkel, D.; Benndorf, C.; Eckert, H.; Matar, S. F.; Pöttgen, R. Z. Kristallogr. 2016, 231, 475–486.10.1515/zkri-2016-1957Search in Google Scholar

124. Voßwinkel, D.; Pöttgen, R. Z. Naturforsch. 2017, 72b, 775–780.10.1515/znb-2017-0073Search in Google Scholar

125. Voßwinkel, D.; Niehaus, O.; Pöttgen, R. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2013, 639, 2623–2630.10.1002/zaac.201300369Search in Google Scholar

126. Shu, J. W.; Adroja, D. T.; Hillier, A. D.; Zhang, Y. J.; Chen, Y. X.; Shen, B.; Orlandi, F.; Walker, H. C.; Liu, Y.; Cao, C.; Steglich, F.; Yuan, H. Q.; Smidman, M. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 104, L140411 (6 pages); https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.104.l140411.Search in Google Scholar

127. Thomas, S. M.; Seo, S.; Asaba, T.; Ronning, F.; Rosa, P. F. S.; Bauer, E. D.; Thompson, J. D. Phys. Rev. B 2024, 109, L121105 (6 pages); https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.109.l121105.Search in Google Scholar

128. Voßwinkel, D.; Block, T.; Pöttgen, R. Z. Naturforsch. 2025, 80b. submitted for publication.Search in Google Scholar

129. Lipatov, A.; Gribanov, A.; Grytsiv, A.; Safronov, S.; Rogl, P.; Rousnyak, J.; Seropegin, Y.; Giester, G. J. Solid State Chem. 2010, 183, 829–843; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2010.01.029.Search in Google Scholar

130. Voßwinkel, D.; Block, T.; Pöttgen, R. Z. Kristallogr. NCS 2025, 240. submitted for publication.Search in Google Scholar

131. Block, T.; Voßwinkel, D.; Pöttgen, R. Z. Kristallogr. NCS 2025, 240. submitted for publication.10.1515/ncrs-2025-0068Search in Google Scholar

132. Amano, S.; Bogdanovski, D.; Yamane, H.; Terauchi, M.; Dronskowski, R. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 1652–1657; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201680561.Search in Google Scholar

133. Yamane, H.; Hiraka, K. Acta Crystallogr. E 2018, 74, 1366–1368; https://doi.org/10.1107/s205698901801188x.Search in Google Scholar

134. Yamane, H.; Hiraka, K. Acta Crystallogr. C 2018, 74, 917–922; https://doi.org/10.1107/s2053229618009634.Search in Google Scholar

135. Amano, S.; Yamane, H. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 675, 377–380; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.03.096.Search in Google Scholar

136. Amano, S.; Yamane, H. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 11610–11618; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b01538.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

137. Yamane, H.; Amano, S. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 701, 967–974; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.01.068.Search in Google Scholar

138. Xu, M.; Canfield, P. C.; Ostenson, J. E.; Finnemore, D. K.; Cho, B. K.; Wang, Z. R.; Johnston, D. C. Physica C 1994, 227, 321–326; https://doi.org/10.1016/0921-4534(94)90088-4.Search in Google Scholar

139. Xu, M.; Cho, B. K.; Canfield, P. C.; Finnemore, D. K.; Johnston, D. C.; Farrell, D. E. Physica C 1994, 235-240, 2533–2534.10.1016/0921-4534(94)92487-2Search in Google Scholar

140. Canfield, P. C.; Cho, B. K.; Dennis, K. W. Physica B 1995, 215, 337–343; https://doi.org/10.1016/0921-4526(95)00421-2.Search in Google Scholar

141. Cho, B. K.; Canfield, P. C.; Miller, L. L.; Johnston, D. C.; Beyermann, W. P.; Yatskar, A. Phys. Rev. B 1995, 52, 3684–3695; https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.52.3684.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

142. Cho, B. K.; Xu, M.; Canfield, P. C.; Miller, L. L.; Johnston, D. C. Phys. Rev. B 1995, 52, 3676–3683; https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.52.3676.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

143. Johnston-Halperin, E.; Fiedler, J.; Farrell, D. E.; Xu, M.; Cho, B. K.; Canfield, P. C.; Finnemore, D. K.; Johnston, D. C. Phys. Rev. B 1995, 51, 12852–12853; https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.51.12852.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

144. Ovchinnikov, A.; Bobev, S. Acta Crystallogr. C 2018, 74, 269–273; https://doi.org/10.1107/s2053229618001596.Search in Google Scholar

145. Smith, G. S.; Johnson, Q.; Tharp, A. G. Acta Crystallogr. 1967, 23, 640–644; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0365110x67003329.Search in Google Scholar

146. Thimmaiah, S.; Taufour, V.; Saunders, S.; March, S.; Zhang, Y.; Kramer, M. J.; Canfield, P. C.; Miller, G. J. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 8484–8488; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b04505.Search in Google Scholar

147. Kaiser, M.; Isaeva, A.; Ruck, M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 6178–6180; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201101248.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

148. Kaiser, M.; Isaeva, A.; Skrotzki, R.; Schwarz, U.; Ruck, M. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2011, 637, 2026–2032; https://doi.org/10.1002/zaac.201100286.Search in Google Scholar

149. Ryu, G.; Son, K.; Schütz, G. J. Cryst. Growth 2016, 440, 26–30; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2016.01.018.Search in Google Scholar

150. Bailey, N. J.; Carr, M. R.; David, J. P. R.; Richards, R. D. J. Nanomater. 2022, 5108923 (9 pages).10.1155/2022/5108923Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Obituary

- Obituary for Hartmut Bärnighausen

- Micro Review

- Bismuth as reactive and non-reactive flux medium for the synthesis and crystal growth of intermetallics

- Organic and Metalorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Racemic and unusual enantiomeric crystal forms of N-cycloalkyl-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamides and their biological activity

- Inorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Lead phosphate oxyapatite, Pb10(PO4)6O, with c-double superstructure

- A novel microporous uranyl silicate prepared by high temperature flux technique

- The Grubbs catalyst – dichlorido(1-(2,6-diethylphenyl)-3,5,5-trimethyl-3-phenylpyrrolidin-2-ylidene)-({5-nitro-2-[(propan-2-yl)oxy]phenyl}methylidene)ruthenium(II) – some observations on the crystallography and stereochemistry of a racemic mimic pair

- Thermal decomposition of copper(II) hydroxide and hydroxocarbonates according to X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy in operando

- New calcium perrhenates: synthesis and crystal structures of Ca(ReO4)2 and K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Obituary

- Obituary for Hartmut Bärnighausen

- Micro Review

- Bismuth as reactive and non-reactive flux medium for the synthesis and crystal growth of intermetallics

- Organic and Metalorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Racemic and unusual enantiomeric crystal forms of N-cycloalkyl-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamides and their biological activity

- Inorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Lead phosphate oxyapatite, Pb10(PO4)6O, with c-double superstructure

- A novel microporous uranyl silicate prepared by high temperature flux technique

- The Grubbs catalyst – dichlorido(1-(2,6-diethylphenyl)-3,5,5-trimethyl-3-phenylpyrrolidin-2-ylidene)-({5-nitro-2-[(propan-2-yl)oxy]phenyl}methylidene)ruthenium(II) – some observations on the crystallography and stereochemistry of a racemic mimic pair

- Thermal decomposition of copper(II) hydroxide and hydroxocarbonates according to X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy in operando

- New calcium perrhenates: synthesis and crystal structures of Ca(ReO4)2 and K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O