Abstract

A new uranyl silicate [(K,Na)4Cl2][(UO2)6(Si2O7)2F2] (1) was obtained from melt in evacuated silica tubes. The crystal structure of 1 is orthorhombic, Pnma, a = 36.8677(7), b = 7.7946(2), c = 19.1931(4) Å, V = 5,515.5(2) Å3. It represents a microporous framework comprised of UrO5 and UrO4F pentagonal bipyramids and Si2O7 disilicate groups. The framework contains two types of channels with the size of 8.14 × 8.66 and 6.38 × 4.42 Å2; the smaller ones host the potassium cations while the larger ones contain more complex alkali-chloride species.

1 Introduction

The interest to the compounds of uranium is supported by their formation as minerals upon oxidation and weathering of uranium deposits 1 , 2 and upon processing and storage of spent nuclear fuel. 3 , 4 As demonstrated by some model experiments, 5 some of these compounds can absorb and/or incorporate various radionuclides. 6 In contrast to the majority of uranium compounds containing tetrahedral anions like sulfates, selenates, chromates, etc., silicates are chemically and thermally stable in a wide range of conditions, considering both physical and chemical factors. As we had demonstrated earlier, 7 , 8 framework uranyl silicates commonly behave akin to zeolites and participate in ion exchange and hydration-dehydration reactions without losing crystallinity and structural integrity which suggests their possible future use as molecular sieves. 9

Among the uranium compounds containing tetrahedral anions TO4 n- , uranyl silicates form a yet relatively small family which however exhibits a vast structural diversity. 7 While some uranyl silicates and germanates are isostructural, 10 the topological variability is more common for the former due to hardly limited possibilities for condensation of the silicate tetrahedra leading to formation of various, frequently unique uranyl-silicate architectures.

In the inorganic compounds, hexavalent uranium commonly forms a linear dioxocation, or uranyl (Ur) which is coordinated, in the equatorial plane, by four to six ligands forming the respective bipyramids. Less common is the formation of distorted octahedral coordination 11 or the so-called “tetraoxide core”. 12 The equatorial sites can be occupied by a variety of ligands including OH−, H2O, as well as F, Cl, and Br, commonly with formation of mixed-ligand coordination. 13 The UO2F n O 5-n bipyramids (n = 1–4), compared to the UO2O5, are more prone to condensation via vertex- and edge-sharing with formation of various structural architectures. 14

A number of synthetic approaches has been reported for preparation or uranyl silicates, including hydrothermal 15 , 16 , 17 and solid state. 18 Many microporous uranyl silicates were prepared using (reactive) flux technologies. 10 , 19 Recently, 7 , 8 , 20 we developed a new variation of flux synthesis using reactive melts and sealed silica tubes which serve as the source of silicon. Not only the chemical composition, but also the pressure may be varied until the “tolerance limit” of the silica tube.

Hereby we report the preparation and structural features of a new complex uranyl silicate, [(K,Na)4Cl2][(UO2)6(Si2O7)2F2], obtained via the reactive flux – silica tube technique; this compound represents a unique structure type.

2 Experimental

2.1 Synthesis

Previously lead oxide and alkali halides were used as the components of the reactive flux and the silica tube was “activated” by adding traces of hydrogen fluoride. An alternative was the use of mixture of Bi2O3 and BiF3. These syntheses resulted in formation of hexavalent uranium compounds. In this case, a SbIII-based medium was used. 2 mmol U3O8, 1 mmol Sb2O3, 1 mmol SbF3, and 20 mmol KCl were pre-dried and placed in a silica tube (inner diameter 8 mm, wall thickness 1.5 mm, length 150 mm) which was evacuated to 3 × 10−2 mm Hg and flame-sealed. The tube was placed in a vertical furnace so that its upper end protruded out and could collect volatile products, to avoid possible pressure buildup and tube destruction. The tube was heated to 825 °C within one day, soaked for 60 h, and slowly cooled to 625 °C after which it cooled naturally when the furnace was switched off. The inner surface of the tube was essentially attacked but the tube retained its integrity; the sample was a dark solidified melt with crystals found on the top and just above on the walls. The tiny needle-like yellowish crystals were found to belong to the targeted uranyl silicate 1 (Figure 1); they also were found to incorporate some sodium, most likely from the tube material. Crystals of more intense hue were found to contain antimony but not silicon; their structure will be reported elsewhere.

![Figure 1:

Photo and a SEM image of the [(K,Na)4Cl2][(UO2)6(Si2O7)2F2] crystals.](/document/doi/10.1515/zkri-2024-0121/asset/graphic/j_zkri-2024-0121_fig_001.jpg)

Photo and a SEM image of the [(K,Na)4Cl2][(UO2)6(Si2O7)2F2] crystals.

2.2 Single-crystal X-ray diffraction

Single-crystal X-ray data were collected using a Bruker APEX 2 Duo diffractometer operating with MoKα radiation at 50 kV and 0.6 mA. A single crystal of each phase was chosen and more than a hemisphere of data collected with a frame width of 0.5° in ω, and 50 s spent counting for each frame. Different experimental conditions were used for the tiny 4 μm width crystals, including data collection at ambient conditions, and in nitrogen flow at 100 and 150 K. Yet, only moderate quality of diffraction data could be attained.

The structure of 1 was successfully refined with the use of SHELX software package. 21 Atom coordinates and thermal displacement parameters for each atom are collected in the corresponding cif file; experimental parameters are provided in Table 1.

Crystallographic parameters and refinement parameters for [(K,Na)4Cl2][(UO2)6(Si2O7)2F2].

| Compound | 1 |

|---|---|

| Crystal system | Orthorhombic |

| Space group | Pnma |

| a, Å | 36.8677(7) |

| b, Å | 7.7946(2) |

| с, Å | 19.1931(4) |

| V, Å3 | 5,515.5(2) |

| F(000) | 7,449 |

| Density | 5.289 |

| Radiation, wavelength, Å | MoKα |

| Ranges of h, k, l | −42 ≤ h ≤ 48, |

| −10 ≤ k ≤ 9, | |

| −25 ≤ l ≤ 24 | |

| Number of reflections | 7,126 |

| Number of unique reflections | 6,535 |

| R int/ R sigma | 0.144/0.335 |

| R1 [F > 4σ(F)]/wR1 | 0.087/0.206 |

| R2/wR 2 | 0.093/0.210 |

| GOF | 1.025 |

2.3 Elemental analysis

Semi-quantitative elemental analyses were measured using a field emission scanning electron microprobe (LEO EVO 50) equipped with an Oxford INCA Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectrometer (EDX). EDX data were collected from several crystals and demonstrate that confirming the presence of all the elements reported in the compounds.

3 Results

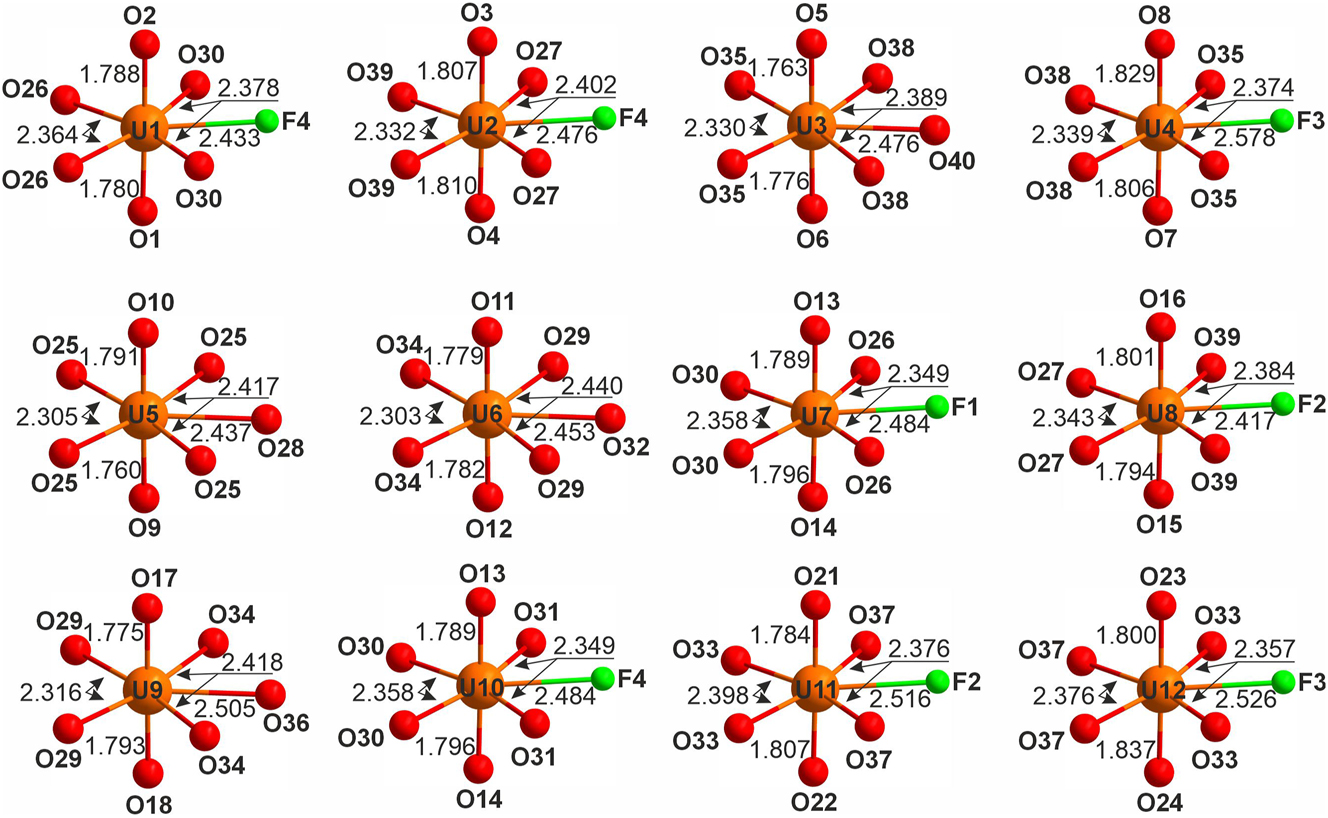

There are 12 symmetrically unique U sites in the structure of 1. The UVI forms typical uranyl ions with <U-Oap> in the range 1.765–1.820 Å (Table S1) whereof four are equatorially coordinated by five oxygens (<Ur-Oeq> = 2.376–2.393 Å) with formation of UrO5, while eight, by four oxygens (<Ur-Oeq> = 2.355–2.385 Å) and one fluorine (<Ur-F> = 2.420–2.580 Å) with formation of UrO4F (Figure 2).

Coordination of the uranyl ions in the structure of 1.

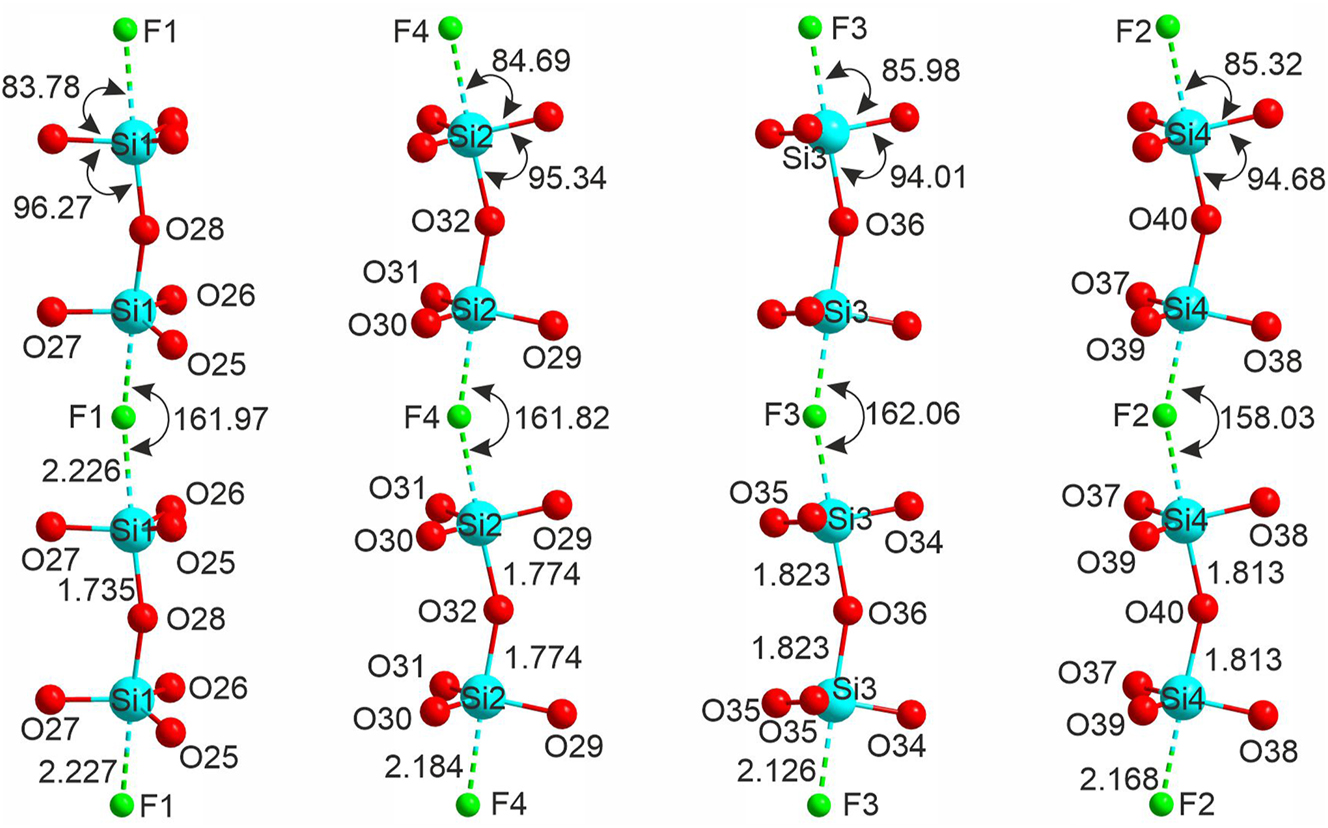

Four symmetrically independent silicon atoms are tetrahedrally coordinated (Table S1) with the respective <Si–O> distances in the range of 1.630 and 1.658 Å. Two silicate polyhedra share a single vertex forming the Si2O7 groups (Figure 3), linked into chains via weak additional Si–F interactions. The respective Si–F separations range from 2.127(14) to 2.227(11) Å. In fact, the coordination of the silicon atoms can be considered intermediate between tetrahedral SiO4 and trigonal bipyramidal SiO4F. Three out of the four oxygen atoms are nearly coplanar forming a pseudo-equatorial plane; the silicon atoms are shifted noticeably from the “classical” center of the oxygen tetrahedron. The lengths of the “bridging” Si-Obr bonds vary between 1.734(12) and 1.823(14) Å. The O–Si–O very in the range of 94.01(11)–96.27(5)°. In the SiO4F bipyramid, the Si–F bonds are essentially longer than Si–O (by ca. 0.5 Å), while the O–Si–F angles are in the range of 83.78(7)–85.98(7)° which is ca. 10° smaller compared to O–Si–O. These silicate-fluoride chains are wavy with the corrugation angle of 158.03–162.06°.

The silicate-fluoride chains formed by fluorine-linked Si2O7 groups in the structure of 1.

In addition to the U and Si sites, there are six M-sites occupied by the sodium and potassium cations (Table S1). The M1 (100 % K) is coordinated by ten oxygen atoms (<M-O> = 2.744 Å), which belong to the uranyl moieties, Ur1–Ur9. The M2, M3, and M5 contain some sodium cations and are coordinated by both oxygen and chlorine atoms. The M2 contains 66 % K and 34 % Na; it is coordinated by four oxygen (<M2-O> = 3.801 Å) and six chlorine atoms (<M2-Cl> = 3.149 Å). The M3 site (61 % K, 39 % Na) is coordinated by three oxygen (<M3-O> = 3.780 Å) and seven chlorine atoms (<M3-Cl> = 3.117 Å). The M4-M6 positions are half occupied, M4 by K, M5 by K and Na (28 and 22 %) and M6 by Na (Na5A and Na5B). The M5 is coordinated by six oxygen (<M5-O> = 3.035 Å) and one chlorine atom (<M5-Cl> = 2.344 Å), the M4 is coordinated by seven oxygen (<M4-O> = 3.005 Å) and three chlorine (<M4-Cl> = 3.006 Å) atoms.

The bond valence sums, calculated using the parameters from 22 for the SiIV–O, SiIV–F, K+ –O, Na+ –O, K+–Cl, Na+–Cl, UVI–F bonds, the parameters from 23 for the UVI–O bonds and the parameters from 24 for UVI–F bonds. The bond-valence sums (BVS) vary between 5.89 and 6.14 valence unit (vu) for U6+ cations in UrO5 coordination and between 5.58 and 5.94 vu for UVI cations in UrO4F coordination. As yet, the number of entries for the UVI–F is relatively small so the used parameters are not statistically verified which lowers the precision of calculations. The BVS for SiIV vary between 3.95 and 4.13 valence units (vu) which correlates fairly to the formal valences of the atoms. The BVS for the cations located in the channels are 0.79 vu for the M1 (K1) site, and 1.16, 1.22, 0.71 and 0.60 vu for the M2–M5 sites. The BVS for oxygen atoms vary between 1.70 and 2.20 vu, for F and Cl atoms, between 0.63–1.01 and 0.39–0.81, respectively. The latter low sums for the chlorine atoms are due to their low occupancies. The BVS results confirm the oxidation states for U, Si, Na and K, as well as the distribution of F and Cl in the crystal structures.

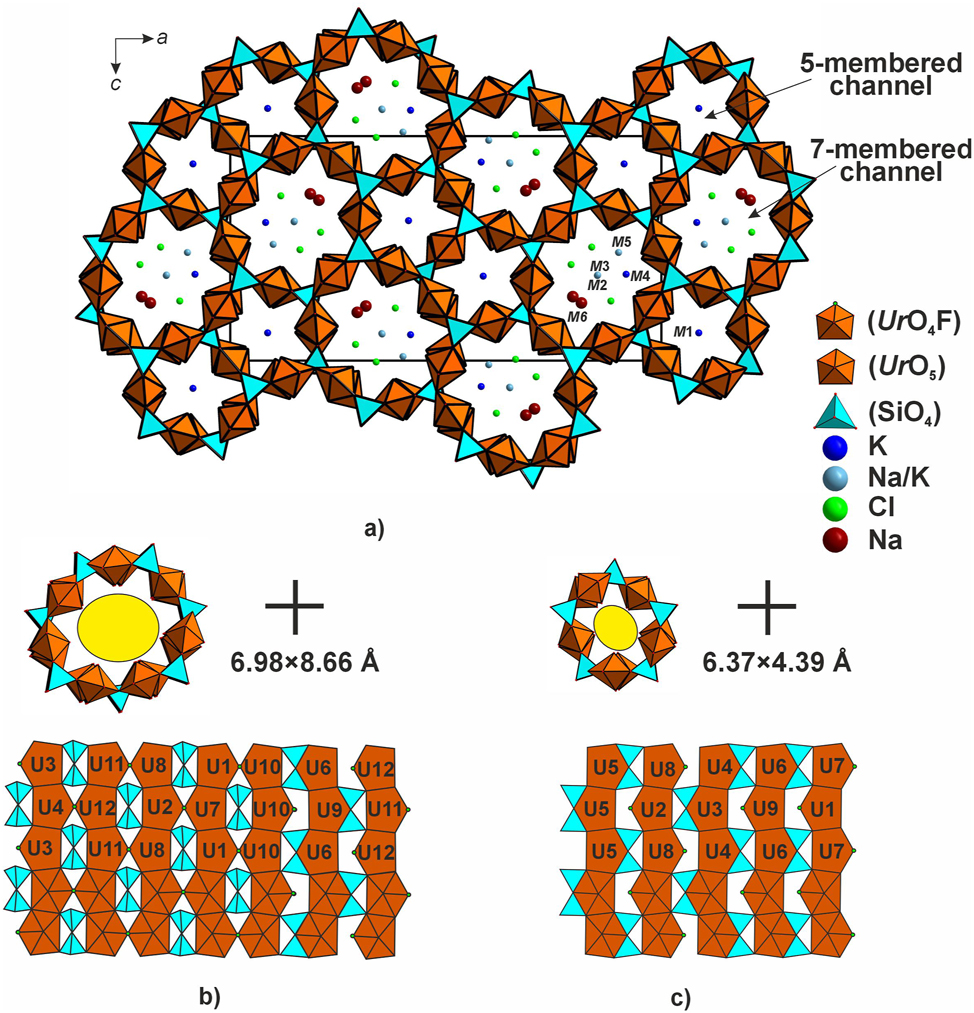

In the structure of 1, the uranyl polyhedra share edges to form chains (Figure 4) commonly observed among uranyl silicate minerals, e.g. sklodowskite, Mg[(UO2)2(SiO3OH)2](H2O)6, kasolite, Pb[(UO2)(SiO4)](H2O)2, and haiweeite, Ca[(UO2)2Si5O12(OH)2](H2O)36. Overall, there are twelve types of these chains whereof ten are formed from two symmetry-dissimilar polyhedra while two, exclusively from those of Ur5 and Ur10, respectively. These chains share vertices with the Si2O7 groups forming a microporous framework (Figure 4). In the ac plane, there are two channel systems. The larger (seven-membered) ones are filled by Na+, K+, and Cl− while the smaller (five-membered), only by K+. Hence, the cations in the formed channels adopt a mixed-anion (O + Cl) coordination while those in the latter are coordinated only by oxygen atoms. The size of the 7-membered channels (calculated from O8–O13 and O18–O23 separations) is 6.98 × 8.66 Å while that of the 5-membered channels (calculated from O6–O14 and O17–O4 separations) is 6.37 × 4.39 Å.

Projection of the structure of 1 onto ac (a), and the 7- (b) and 5- membered channels (c) and development of their walls.

To describe the topology of the channel walls, develop them onto the plane. The 7-membered channels are comprised of seven chains which are linked by equatorial fluorine vertices. The voids are filled by the Si2O7 groups. There are two ways of their linkage: the disilicate groups share edges with Ur6O5 and Ur9O5 and vertices with the remaining polyhedra. The topology of the 5-membered channels is slightly different. These are comprised of five uranyl chains which share only edges with the disilicate groups.

4 Discussion and concluding remarks

As noted above, various synthetic approaches to uranyl silicates and germanates, particularly employing reactive fluxes, commonly result in formation of microporous frameworks 10 and salt-inclusion structures. 25 In most cases, these are formed from silicate/germanate chains or layers linked together by the uranium polyhedra. The structures of the minerals weeksite 26 and soddyite 27 present relatively rare examples of zeolite-like frameworks wherein the uranium polyhedra share edges. Note that the chains of edge-sharing UrO5 may be considered as common building blocks for a variety of natural and synthetic uranyl silicates. 27 In the minerals noted above, these chains are linked by isolated silicate tetrahedra while in 1, by the Si2O7 groups.

Though uranyl silicate minerals are widespread and common in oxidation areas of deposits, no minerals containing diorthosilicate groups have been reported to date. These groups have been observed in the structures of seven synthetic compounds (Figure 5). In the structure of [CsF](UO6)2(UO2)9(Si2O7) 20 the Si2O7 groups are also linked by fluoride anions into the chains topologically identical to those in 1; however, these are perfectly linear. The silicon atoms reside very close to the geometrical centers of the SiO4 tetrahedra; the O–Si–O angle is also nearly ideal, i.e. 108.29(4), while O–Si–F equals 71.70(7)°. The Si–O bond length is 1.639(5) Å (against 1.786(3) Å in 1) Å, and the Si–F separations are as long as 2.643(7) Å (against 2.126(5)–2.26(4) Å in 1).

2(UO2)9(Si2O7) (a), Rb2(PtO4)(UO2)5(Si2O7) (b), K2Ca4[(UO2)(Si2O7)2] (c), K3(U3O6)(Si2O7) (d), K3Cs4F(UO2)3(Si2O7)2 (e), NaRb6F(UO2)3(Si2O7)2 (f), and (Na9F2)((UO2)(UO2)2(Si2O7)2) (g).](/document/doi/10.1515/zkri-2024-0121/asset/graphic/j_zkri-2024-0121_fig_005.jpg)

Disilcate groups in the structures of [CsF](UO6)2(UO2)9(Si2O7) (a), Rb2(PtO4)(UO2)5(Si2O7) (b), K2Ca4[(UO2)(Si2O7)2] (c), K3(U3O6)(Si2O7) (d), K3Cs4F(UO2)3(Si2O7)2 (e), NaRb6F(UO2)3(Si2O7)2 (f), and (Na9F2)((UO2)(UO2)2(Si2O7)2) (g).

The trigonal pyramidal coordination of silicon, rare as it is commonly assumed to be, has also been reported in the structure of Rb2(PtO4)(UO2)5(Si2O7). Therein, the silicon atoms are coordinated by five oxygen atoms with formation of a SiO5 moiety with one semi-occupied vertex. The Si atom is coordinated, in the equatorial plane, by three oxygen atoms with the Oap–Si–Oeq bond angle of 89.87°. The Si–Oap distance is 1.962 Å.

The diortho Si2O7 groups are the only silicate-bearing species in the frameworks of K2Ca4[(UO2)(Si2O7)2], 28 K3(U3O6)(Si2O7), 29 K3Cs4F(UO2)3(Si2O7)2 and NaRb6F(UO2)3(Si2O7)2, 25 as well as (Na9F2)((UO2)(UO2)2(Si2O7)2). 30

In contrast to the compounds discussed above, in the latter structures the Si2O7 groups do not align into chains though their axes are parallel. These groups adopt a typical geometry of two vertex-sharing tetrahedra (d(Si–O) = 1.607–1.665 Å, φ(Si–O–Si) = 101.85–108.77°) with different conformations. When only vertices are shared to the uranyl polyhedra, the Si–O–Si angle is nearly 180°; in case of edge sharing, the Si–O–Si tends to the value between the equatorial edhes of the uranyl polyhedron (136.72–153.76°). Both conformations are observed in the structure of 1: the former, upon condensation of Si2O7 and chains comprised of Ur8O4F and Ur2O4F, and the second, with the chains comprised of Ur6O5 and Ur9O5.

Acknowledgments

Technical support by the X-Ray Diffraction Resource Center of Saint-Petersburg State University is gratefully acknowledged. This work was financially supported by the Russian Science Foundation through the grant 23-27-00153.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Competing interests: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: Russian Science Foundation 23-27-00153.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

1. Belova, L. N.; Doynikova, O. A. Conditions of Formation of Uranium Minerals in the Oxidation Zone of Uranium Deposits. Geol. Ore Deposit. 2003, 45, 130–132.Search in Google Scholar

2. Baik, M. H.; Cho, H. R. Roles of Uranyl Silicate Minerals in the Long-Term Mobility of Uranium in Fractured Granite. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2022, 331, 451–459; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-021-08084-1.Search in Google Scholar

3. Baker, R. J. Uranium Minerals and Their Relevance to Long Term Storage of Nuclear Fuels. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2014, 266–267.10.1016/j.ccr.2013.10.004Search in Google Scholar

4. Finch, R. J.; Buck, E. C.; Finn, P. A.; Bates, J. K. Scientific Basis for Nuclear Waste Management. In XXII, Materials Research Society Symposium Proceeding, Materials Research Society, Warrendale. PA., Vol. 556, 1999; pp 431–438.Search in Google Scholar

5. Burns, P. C.; Olson, R. A.; Finch, R. J.; Hanchar, J. M.; Thibault, Y. KNa3(UO2)2(Si4O10)2(H2O)4, a New Compound Formed during Vapor Hydration of an Actinide-Bearing Borosilicate Waste Glass. J. Nucl. Mater. 2000, 278, 290–300; https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3115(99)00247-0.Search in Google Scholar

6. Oji, L. N.; Martin, K. B.; Stallings, M. E.; Duff, M. C. Conditions Conducive to Forming Crystalline Uranyl Silicates in High Caustic Nuclear Waste Evaporators. Nucl. Technol. 2006, 154, 237–246; https://doi.org/10.13182/nt06-a3731.Search in Google Scholar

7. Nazarchuk, E. V.; Siidra, O. I.; Charkin, D. O.; Tagirova, Y. G. Framework Uranyl Silicates: Crystal Chemistry and а New Route for the Synthesis. Materials 2023, 16, 4153; https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16114153.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Nazarchuk, E. V.; Siidra, O. I.; Charkin, D. O.; Tagirova, Y. G. Uranyl Silicate Nanotubules in Rb2[(UO2)2O(Si3O8)]: Synthesis and Crystal Structure. Z. Kristallogr. 2023, 238, 349; https://doi.org/10.1515/zkri-2023-0019.Search in Google Scholar

9. Chen, F.; Burns, P. C.; Ewing, R. C. Near-Field Behaviour of 99Tc during the Oxidative Alteration of Spent Nuclear Fuel. J. Nucl. Mater. 2000, 278, 225–232; https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3115(99)00264-0.Search in Google Scholar

10. Li, H.; Langer, E. M.; Kegler, P.; Alekseev, E. V. Structural and Spectroscopic Investigation of Novel 2D and 3D Uranium Oxo-Silicates/Germanates and Some Statistical Aspects of Uranyl Coordination in Oxo-Salts. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 10333–10345; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b01523.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Morrison, J. M.; Moore-Shay, L. J.; Burns, P. C. U(VI) Uranyl Cation-Cation Interactions in Framework Germanates. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 2272–2277; https://doi.org/10.1021/ic1019444.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Zadoya, A. I.; Siidra, O. I.; Bubnova, R. S.; Nazarchuk, E. V.; Bocharov, S. N. Tellurites of Hexavalent Uranium: First Observation of Polymerized (UO4)2– Tetraoxido Cores. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 2016, 4083; https://doi.org/10.1002/ejic.201600624.Search in Google Scholar

13. Nazarchuk, E. V.; Siidra, O. I.; Krivovichev, S. V. Crystal Chemistry of Uranyl Halides Containing Mixed (UO2)(XmOn)5 Bipyramids (X = Cl, Br): Synthesis and Crystal Structure of Cs2(UO2)(NO3)C13. Z. Naturforsch. 2011, 66b, 142–146.10.5560/ZNB.2011.66b0142Search in Google Scholar

14. Attfield, M. P.; Catlow, R. R. A.; Sokol, A. A. True Structure of Trigonal Bipyramidal SiO4F – Species in Siliceous Zeolites. Chem. Mater. 2001, 13, 4708–4713; https://doi.org/10.1021/cm011141i.Search in Google Scholar

15. Chen, Y.-H.; Liu, H.-K.; Chang, W.-J.; Tzou, D.-L.; Lii, K.-H. High-temperature, High-Pressure Hydrothermal Synthesis, Characterization, and Structural Relationships of Mixed-Alkali Metals Uranyl Silicates. J. Solid State Chem. 2016, 236, 55–60; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2015.07.034.Search in Google Scholar

16. Huang, J.; Wang, X.; Jacobson, A. J. Hydrothermal Synthesis and Structures of the New Open-Framework Uranyl Silicates Rb4(UO2)2(Si8O20) (USH-2Rb), Rb2(UO2)(Si2O6)·H2O (USH-4Rb) and A2(UO2)(Si2O6)·0.5H2O (USH-5A; A = Rb, Cs). J. Mater. Chem. 2003, 13, 191–196; https://doi.org/10.1039/b208787c.Search in Google Scholar

17. Liu, H. K.; Peng, C. C.; Chang, W. J.; Lii, K. H. Tubular Chains, Single Layers, and Multiple Chains in Uranyl Silicates: A2[(UO2)Si4O10] (A = Na, K, Rb, Cs). Cryst. Growth Des. 2016, 9, 5268–5272; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.cgd.6b00817.Search in Google Scholar

18. Babo, J. M.; Albrecht-Schmitt, T. E. High Temperature Synthesis of Two Open-Framework Uranyl Silicates with Ten-Ring Channels: Cs2(UO2)2Si8O19 and Rb2(UO2)2Si5O13. J. Solid State Chem. 2013, 197, 186–190; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2012.07.048.Search in Google Scholar

19. Juillerat, C. A.; Klepov, V. V.; Morrison, G.; Pace, K. A.; Zur Loye, H. C. Flux Crystal Growth: A Versatile Technique to Reveal the Crystal Chemistry of Complex Uranium Oxides. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 3162–3181; https://doi.org/10.1039/c8dt04675a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Nazarchuk, E. V.; Siidra, O. I.; Charkin, D. O.; Tagirova, Y. G. U(VI) Coordination Modes in Complex Uranium Silicates: Cs[(UO6)2(UO2)9(Si2O7)F] and Rb2[(PtO4)(UO2)5(Si2O7)]. Chemistry 2022, 4, 1515–1523; https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry4040100.Search in Google Scholar

21. Sheldrick, G. M. Crystal Structure Refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. 2015, C71, 3–8, https://doi.org/10.1107/s2053229614024218.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Gagné, O. C.; Hawthorne, F. C. Bond-Length Distributions for Ions Bonded to Oxygen: Results for the Transition Metals and Quantification of the Factors Underlying Bond-Length Variation in In-Organic Solids. Acta Crystallogr. 2016, B72, 602–625.Search in Google Scholar

23. Burns, P. C.; Ewing, R. C.; Hawthorne, F. C. The Crystal Chemistry of Hexavalent Uranium; Polyhedron Geometries, Bond-Valence Parameters, and Polymerization of Polyhedral. Can. Miner. 1997, 35, 1551–1570.Search in Google Scholar

24. Zachariasen, W. H. Bond Lengths in Oxygen and Halogen Compounds of D and F Elements. J. Less-Common Met. 1978, 62, 1–7; https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5088(78)90010-3.Search in Google Scholar

25. Li, C.-S.; Wang, S.-L.; Chen, Y.-H.; Lii, K.-H. Flux Synthesis of Salt-Inclusion Uranyl Silicates: [K3Cs4F] [(UO2)3(Si2O7)2] and [NaRb6F] [(UO2)3(Si2O7)2]. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 8357–8361; https://doi.org/10.1021/ic901001n.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Fejfarová, K.; Plášil, J.; Yang, H.; Čejka, J.; Dušek, M.; Downs, R. T.; Barkley, M. C.; Škoda, R. Revision of the Crystal Structure and Chemical Formula of Weeksite, K2(UO2)2(Si5O13)·4H2O. Amer. Miner. 2012, 97, 750–754.10.2138/am.2012.4025Search in Google Scholar

27. Plášil, J. Mineralogy, Crystallography and Structural Complexity of Natural Uranyl Silicates. Minerals 2018, 8, 551–566; https://doi.org/10.3390/min8120551.Search in Google Scholar

28. Liu, C.-L.; Liu, H.-K.; Chang, W.-J.; Lii, K.-H. K2Ca4[(UO2)(Si2O7)2]: A Uranyl Silicate with a One-Dimensional Chain Structure. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54 (17), 8165–8167; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b01390.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Lin, C.-H.; Chen, C.-S.; Shiryaev, A. A.; Zubavichus, Ya. V.; Lii, K.-H. K3(U3O6)(Si2O7) and Rb3(U3O6)(Ge2O7): A Pentavalent-Uranium Silicate and Germanate. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47 (11), 4445–4447; https://doi.org/10.1021/ic800300v.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Chang, Y.-С.; Chang, W.-J.; Boudin, S.; Lii, K.-H. High-Temperature, High-Pressure Hydrothermal Synthesis and Characterization of a Salt-Inclusion Mixed-Valence Uranium(V, VI) Silicate: [Na9F2] [(UVO2)(UVIO2)2(Si2O7)2]. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52 (12), 7230–7235; https://doi.org/10.1021/ic400854j.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/zkri-2024-0121).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Obituary

- Obituary for Hartmut Bärnighausen

- Micro Review

- Bismuth as reactive and non-reactive flux medium for the synthesis and crystal growth of intermetallics

- Organic and Metalorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Racemic and unusual enantiomeric crystal forms of N-cycloalkyl-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamides and their biological activity

- Inorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Lead phosphate oxyapatite, Pb10(PO4)6O, with c-double superstructure

- A novel microporous uranyl silicate prepared by high temperature flux technique

- The Grubbs catalyst – dichlorido(1-(2,6-diethylphenyl)-3,5,5-trimethyl-3-phenylpyrrolidin-2-ylidene)-({5-nitro-2-[(propan-2-yl)oxy]phenyl}methylidene)ruthenium(II) – some observations on the crystallography and stereochemistry of a racemic mimic pair

- Thermal decomposition of copper(II) hydroxide and hydroxocarbonates according to X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy in operando

- New calcium perrhenates: synthesis and crystal structures of Ca(ReO4)2 and K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Obituary

- Obituary for Hartmut Bärnighausen

- Micro Review

- Bismuth as reactive and non-reactive flux medium for the synthesis and crystal growth of intermetallics

- Organic and Metalorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Racemic and unusual enantiomeric crystal forms of N-cycloalkyl-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamides and their biological activity

- Inorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Lead phosphate oxyapatite, Pb10(PO4)6O, with c-double superstructure

- A novel microporous uranyl silicate prepared by high temperature flux technique

- The Grubbs catalyst – dichlorido(1-(2,6-diethylphenyl)-3,5,5-trimethyl-3-phenylpyrrolidin-2-ylidene)-({5-nitro-2-[(propan-2-yl)oxy]phenyl}methylidene)ruthenium(II) – some observations on the crystallography and stereochemistry of a racemic mimic pair

- Thermal decomposition of copper(II) hydroxide and hydroxocarbonates according to X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy in operando

- New calcium perrhenates: synthesis and crystal structures of Ca(ReO4)2 and K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O