The Grubbs catalyst – dichlorido(1-(2,6-diethylphenyl)-3,5,5-trimethyl-3-phenylpyrrolidin-2-ylidene)-({5-nitro-2-[(propan-2-yl)oxy]phenyl}methylidene)ruthenium(II) – some observations on the crystallography and stereochemistry of a racemic mimic pair

Abstract

The title species has been studied in two crystalline forms resulting from reports describing (1) a centrosymmetric form [P21/n, Z′ = 1.0] and (2) a Sohncke form [P21, Z′ = 2.0; Flack parameter = −0.04(2)]. They are related by the fact that (a) the two have, approximately, the same cell constants, while (b) Z′ is doubled in the latter in the course of losing the n-glide plane. The existence of species displaying such a remarkable relationship was noted approximately 75 years ago, but, ignored probably because the discoverers (see below) never completed the necessary experimental work to fully document the phenomenon, inasmuch as (1) crystallography was in its infancy then and (2) synthesizing the necessary, pure, chiral species and growing the necessary high-quality crystals was a major challenge which has, not even yet, been accomplished. Moreover, O. Hassel, the major player in this field, was distracted by his work on the chair-boat equilibrium in cyclohexane and related rings systems for which he eventually won the Nobel Prize (1969). Herein, we have attempted to contribute a chapter to this curious crystallographic phenomenon, which has been made even more fascinating by the observation that a ruthenium Grubbs catalyst belongs in the racemic mimic class.

1 Introduction

At the moment, awareness of the existence of Racemic Mimic pairs is limited, probably because the members of such pairs are frequently reported by different authors (as is the case here) or the same authors at different times, and miss the correlation, probably because of the difference in Z′. Be as it may, even in cases in which CCDC 1 directs the reader to the existence of the pair, it may not attract the searching authors’ attentions to examine both the papers in the detail sufficient to notice such subtle correlations, which are based on comparison of cell constants; and which, in fact differ by small amounts but large enough to distract the reader’s attention, resulting in missing the correlation-unless, of course, you are already looking for it.

Moreover, curiosity as to whether a clear definition of the concept is available in Internet searches, leads to nothing of value and to a lot of responses having nothing to do with the subject at hand. It is also pertinent to mention that two masterful compendiums on the range of crystallization behaviors, such as Bernstein 2 and Jacques et al. 3 have no entries in their indices for this topic.

This state of affairs is not surprising since its discovery (see below) took place a long time ago and, as we shall see, finding examples of the phenomenon requires substances that can produce high quality crystals of two kinds: racemic and Sohncke, meeting very demanding conditions described in detail in what follows. Therefore, in order to acquaint the reader with the material in print relevant to this discussion, we begin with the question.

2 What is a meant by racemic mimic crystals?

A “racemic mimic” in the context of crystals, described in more detail below, refers to a crystal structure where molecules of a single enantiomer arrange themselves in a crystal lattice in a way that closely resembles the pattern of a true racemic mixture. This effectively mimics the symmetry and packing of a 50:50 mixture of enantiomers; essentially, they create a pseudo-racemic arrangement within a Sohncke crystal structure. Racemic mimics are broadly related to quasi-racemates or pseudo racemates referred to by Wu et al. 4 and Brock. 5 Brock 5 recently documented the approximate periodic symmetry in molecular crystals for Z′ > 1 in the low-symmetry space groups P2 and C2, previously referred to as either pseudo symmetry or hyper symmetry by Zorky. 6 These included many cases where an approximate inversion center in the non-centrosymmetric crystals was recognized. Other terms sometimes used are “pseudo-racemates” or “quasi-racemates”. 4

N.B.: A substance is said to crystallize in the class of Racemic Mimics, if:

It crystallizes with Z = an even number of constituents, consisting of pairs of enantiomers. As such, the space group must be centrosymmetric.

It must also crystallize in a Sohncke space group such that all the chiral centers must be the same; however, dissymmetric fragments do not have to be identical in magnitude; but they must have opposite sign. This is necessary because they are located at semi- or pseudo, or nearly-centers of inversion.

and absolutely necessary, the cell constants must be close to identical; thus, requiring that the Z′(Sohncke) = 2 Z′(centrosymmetric).

3 On racemic mimics from Wood et al. 7 (paraphrased)

A recent study by Wood et al., 7 suggests that Erdmann’s salts of cocaine and methamphetamine display the characteristics of racemic mimics. In this paper, they give a clear and concise explanation of the early recognition of this type of crystalline material, where they direct the reader to four papers that represent some of the earliest modern descriptions of what is now understood as a racemic mimic. Those papers, presented in chronological order, include studies by Furberg and Hassel, 8 who investigated the crystal structure of phenyl glyceric acid grown slowly from water, Schouwstra, 9 , 10 who examined crystals of dl-methylsuccinic acid grown by sublimation and from water solution, and Mostad, 11 who analyzed o-tyrosine crystals grown from methanol with small amounts of ammonia to enhance solubility. In all of these cases, both the racemic and optically pure crystals exhibited nearly identical cell constants. The racemic crystals (P21/n) had Z′ = 1.0, while the pure enantiomers (P21) had Z′ = 2.0. The lattice of the racemic crystals contained racemic pairs, while the pure enantiomers formed pairs of enantiomers. Crystals grown from racemic material contained racemic pairs, while those from the pure enantiomers formed pairs of enantiomers, which is not an oxymoron inasmuch as the former could have crystallized as either conglomerates or kryptoracemates; and, the latter as simple cases of Sohncke crystals with Z′ = 1.0. In a remarkably clear and straightforward answer to the question of “why” and “how”, Furberg and Hassel 8 suggested that the pure chiral material seemed to crystallize as a “twin” that resembled the packing of the true racemate – which they termed a “racemic twin.” They also proposed that substances with flexible (dissymmetric) fragments and low torsional barriers would be ideal candidates for this phenomenon, documenting additional examples. This was an exceptionally advanced concept for its time, and it aligns with the concept we discuss in this report, where we have an example of a racemic mimic pair. Serendipitously, the Erdmann salts of cocaine and methamphetamine fall in the categories just described above; e.g., the nitro ligands of Erdmann’s anion are flexible, low-barrier sources of dissymmetry; e.g., see Bernal. 12

Having clarified the issue of racemic versus racemic mimic, we now define the term “kryptoracemic crystallization” in order to avoid any confusion with that polymorphic class since there may have been some confusion in the past, given that racemic mimics and kryptoracemates are both characterized by having Z′ = 2.0 while belonging to the Sohncke class.

4 The concept of kryptoracemic crystallization

During the 1995 meeting in Montreal, celebrating the 100th Anniversary of the discovery of X-rays by Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, a heretofore un-noticed form of crystallization was described, within the Sohncke class, whose asymmetric unit Z′ = 2.0 which consists of a racemic pair . 13 Given that such crystallization mode was novel and, heretofore never before been described , it was then baptized “kryptoracemic” from the Greek for hidden 13 – e.g., a racemate hidden within a Sohncke space group where, till then, the normal expectation was that both components would be iso-chiral. The substance in question being (±)[Co(en)3]I3·H2O, for which a very detailed structural analysis, including the experimental methods used to ascertain its belonging to the kryptoracemic class (e.g., Second Order Harmonics) were described. 14 We recommend the readers peruse this report.

Soon, it became clear that the phenomenon was not so rare – merely that it had been overlooked. For example, between 1995 and 1998, three new examples of coordination compounds were published appearing in the CCDC 1 as GAPHUA01, 15 NIXGIK, 16 and FILGIQ; 17 eventually, reviews started appearing e.g. 18 , 19 By now, the readers should have enough information to understand what follows, which is a description of our interpretation of the X-ray crystallographic data of one of Grubbs’ catalysts – a ruthenium compound that is the subject of our current inquiry.

5 Ruthenium coordination compounds in the CCDC

There are 1,104 ruthenium coordination compounds reported in the CCDC 1 where the metal has four or more ligands and that crystallize in the space group P21. Of these, 303 (27 %) crystallize in the space group P21 with Z′ = 2. These numbers reduce to 698 and 179 (26 %) respectively if one only includes structures with 3D coordinates, R < 0.075, no disorder or errors, and are not polymeric. Only one of the 303 crystal structures has a racemic structure reported of the same molecule. It is the latter complex, REPTIT 20 that we discuss in this paper.

6 Some background on Grubbs catalysts

A Grubbs catalyst is a transition metal carbene complex used to catalyze olefin metathesis reactions, see Vougioukalakis & Grubbs 21 and Antonova & Zubkov. 22 New cyclic alkyl amino carbene (CAAC) ruthenium complexes that promote macrocyclization and cross metathesis with acrylonitrile reactions at low loadings have recently been reported. 23 The ruthenium compound of interest here (see Scheme 1) was synthesized by Gawin et al. as a racemic mixture and crystallized in the space group P21/n in QEGBUC. 23 In a subsequent study, Morvan et al. 20 the two enantiomers were separated and crystallized as chiraly pure crystals in space group P21 with Z′ = 2 (REPTIT). REPTIT and QEGBUC form a racemic mimic pair, as we now describe.

![Scheme 1:

The structure of the ruthenium coordination compound considered in this study, with * indicating the chiral center: dichlorido[1-(2,6-diethylphenyl)-3,5,5-trimethyl-3-phenylpyrrolidin-2-ylidene]-({5-nitro-2-[(propan-2-yl)oxy]phenyl}methylidene)ruthenium(II).](/document/doi/10.1515/zkri-2025-0001/asset/graphic/j_zkri-2025-0001_scheme_001.jpg)

The structure of the ruthenium coordination compound considered in this study, with * indicating the chiral center: dichlorido[1-(2,6-diethylphenyl)-3,5,5-trimethyl-3-phenylpyrrolidin-2-ylidene]-({5-nitro-2-[(propan-2-yl)oxy]phenyl}methylidene)ruthenium(II).

7 Discussion

As indicated above, we shall now compare the unit cells, stereochemistry and packing features of the two components of the Grubbs catalysts whose REFCODES in the CCDC 1 are QEGBUC 23 and REPTIT, 20 respectively characterized by (a) space group = P21/n, Z′ = 1.0 and (b) P21, Z′ = 2.0. Table 1 compares the unit cell data for the two structures. The similarity between the unit cells is immediately apparent.

The unit cell information for the structures REPTIT and QECBUC discussed in this paper. The Flack parameter was obtained from the deposited data.

| REFCODE | REPTIT 20 | QEGBUC 23 |

|---|---|---|

| Crystal system | Monoclinic | Monoclinic |

| Space group | P21 | P21/n |

| a/Å | 17.3665(11) | 16.3803(14) |

| b/Å | 11.5707(6) | 12.7318(8) |

| c/Å | 17.4342(11) | 17.4287(17) |

| β/° | 115.407(2) | 114.581(11) |

| Unit cell volume/Å3 | 3,164.45(s.u.) | 3,305.36(s.u.) |

| Z | 4 | 4 |

| Z′ | 2 | 1 |

| Flack parameter | −0.04(2) | – |

| T/K | 150 | 273 |

| Density | 1.437 | 1.376 |

| Crystal color | Bronze | Green |

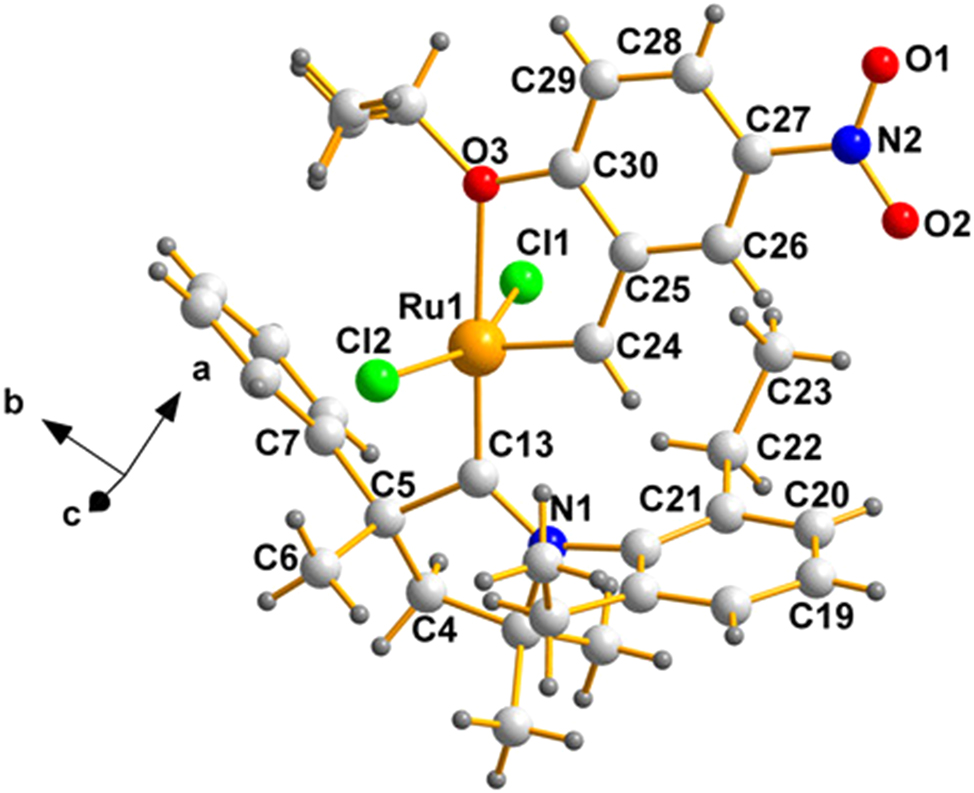

As for the stereochemistry, beginning with the QEGBUC, Figure 1 pictures the molecule present in the asymmetric unit.

A labelled view of the pentacoordinated ruthenium(II) species (QEGBUC) whose C5 is (S), produced using the program, DIAMOND. 24 Crystallizing in a centrosymmetric group, its enantiomer is also present in the lattice.

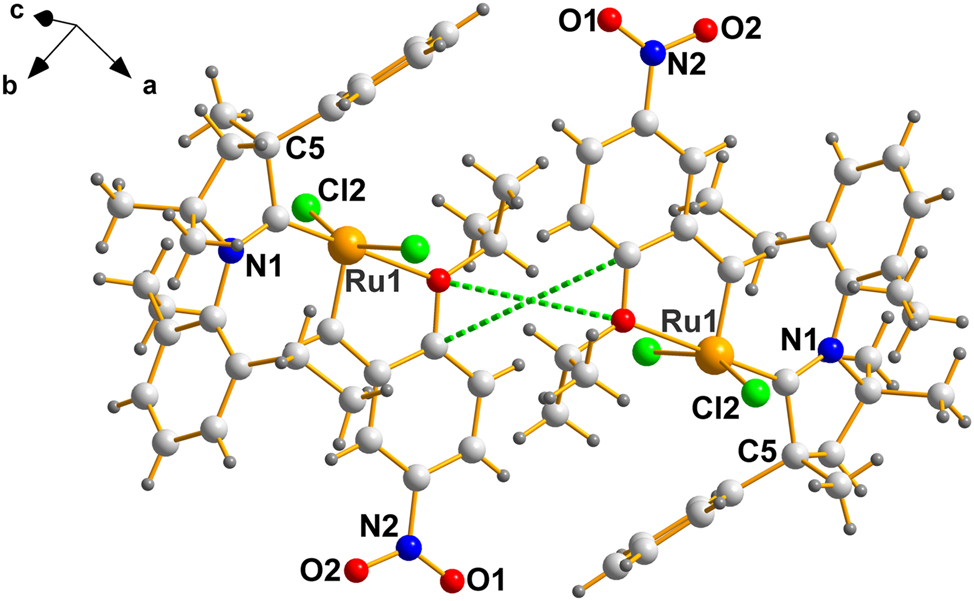

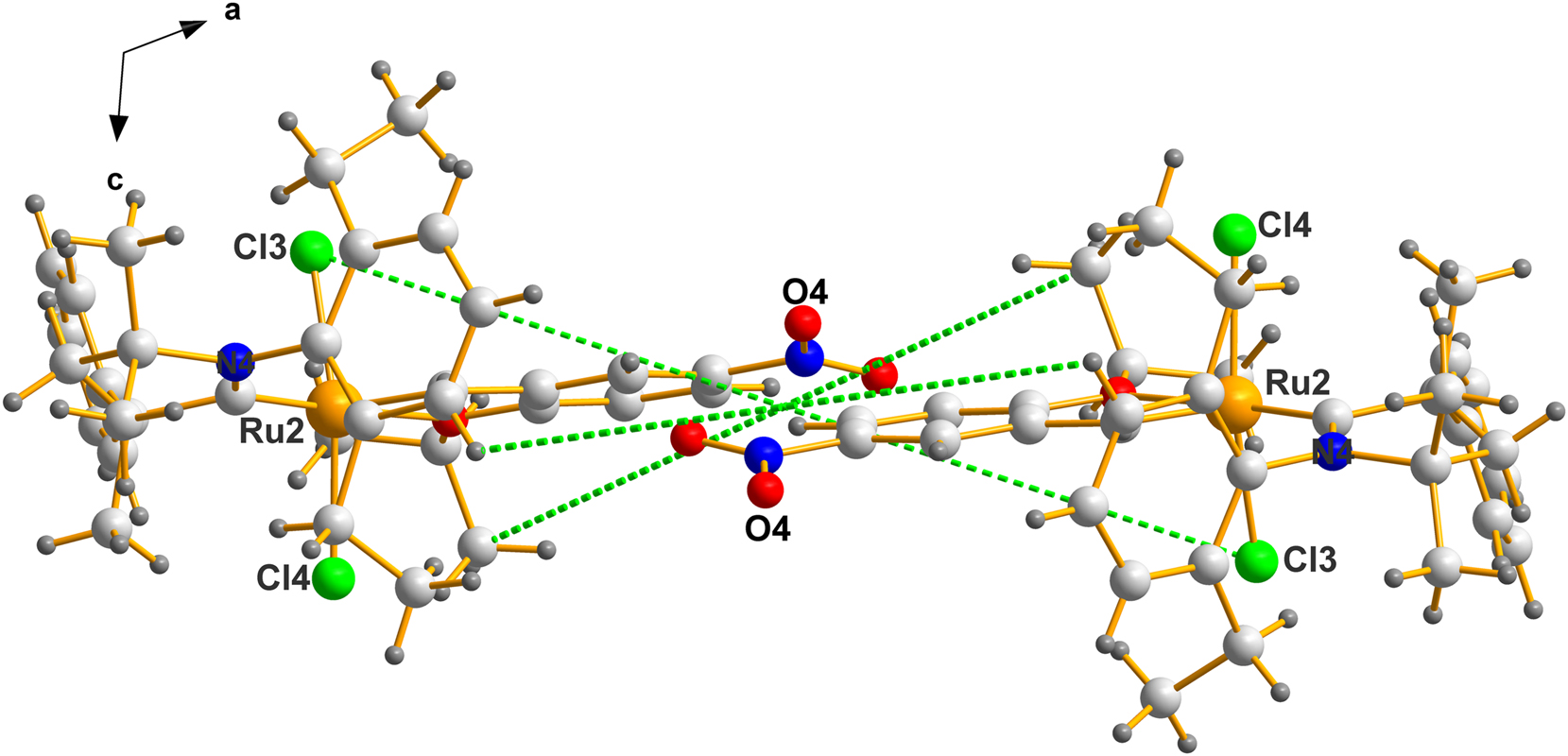

Since QEGBUC 23 is racemic, the mirror image of that in Figure 1 is automatically present in its lattice and C5 will, in that case be (R). The pair should then appear in the lattice as an inverted pair, related by a lattice inversion center – such is the case, as shown in Figure 2.

A labelled view of a centrosymmetrically related pair in QEGBUC. The center of symmetry is located at the intersection of the dotted green lines – (½, 0, 0).

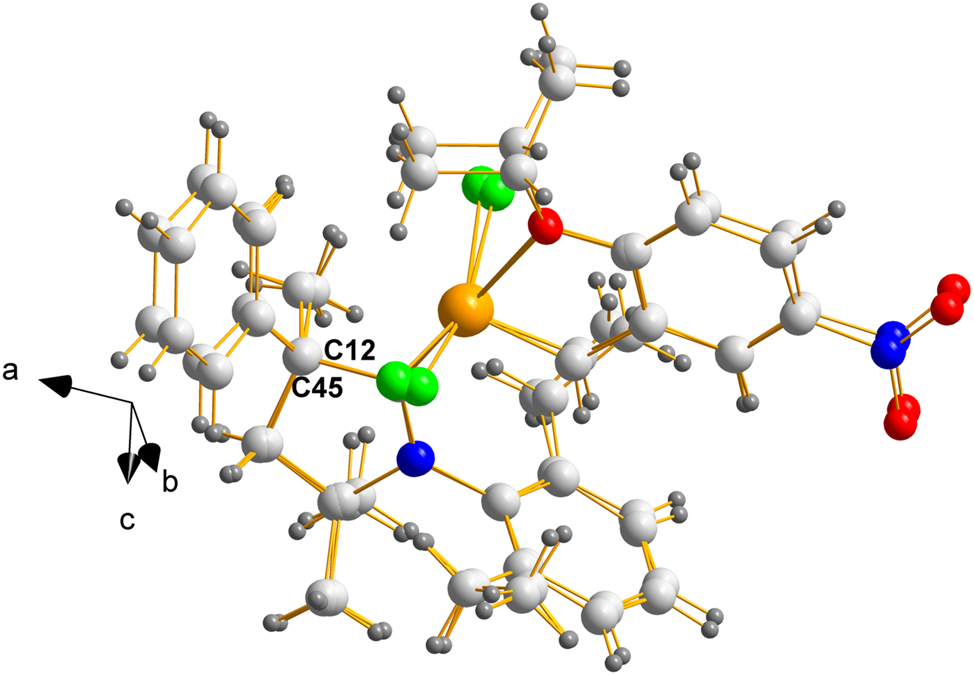

In REPTIT, case (b), where Z′ = 2.0, both enantiomers will have stereochemistry at position 5 will be either (S) or (R), depending on the ligand used, which in this case (C12 and C45) are also (S); thus, identical with the molecule on Figure 1, except for minor variations on torsional angles cause by differences in molecular packing.

With respect to stereochemical differences caused by molecular packing, how similar or different are the pair in case (b)? The answer is displayed Figure 3 which was drawn using MERCURY. 25

Overlay of mol2 on mol1 of REPTIT displaying the chiral (S) carbons labelled C12 and C45. The fit is remarkably good given the large dangling groups, held to the central portion by single bonds.

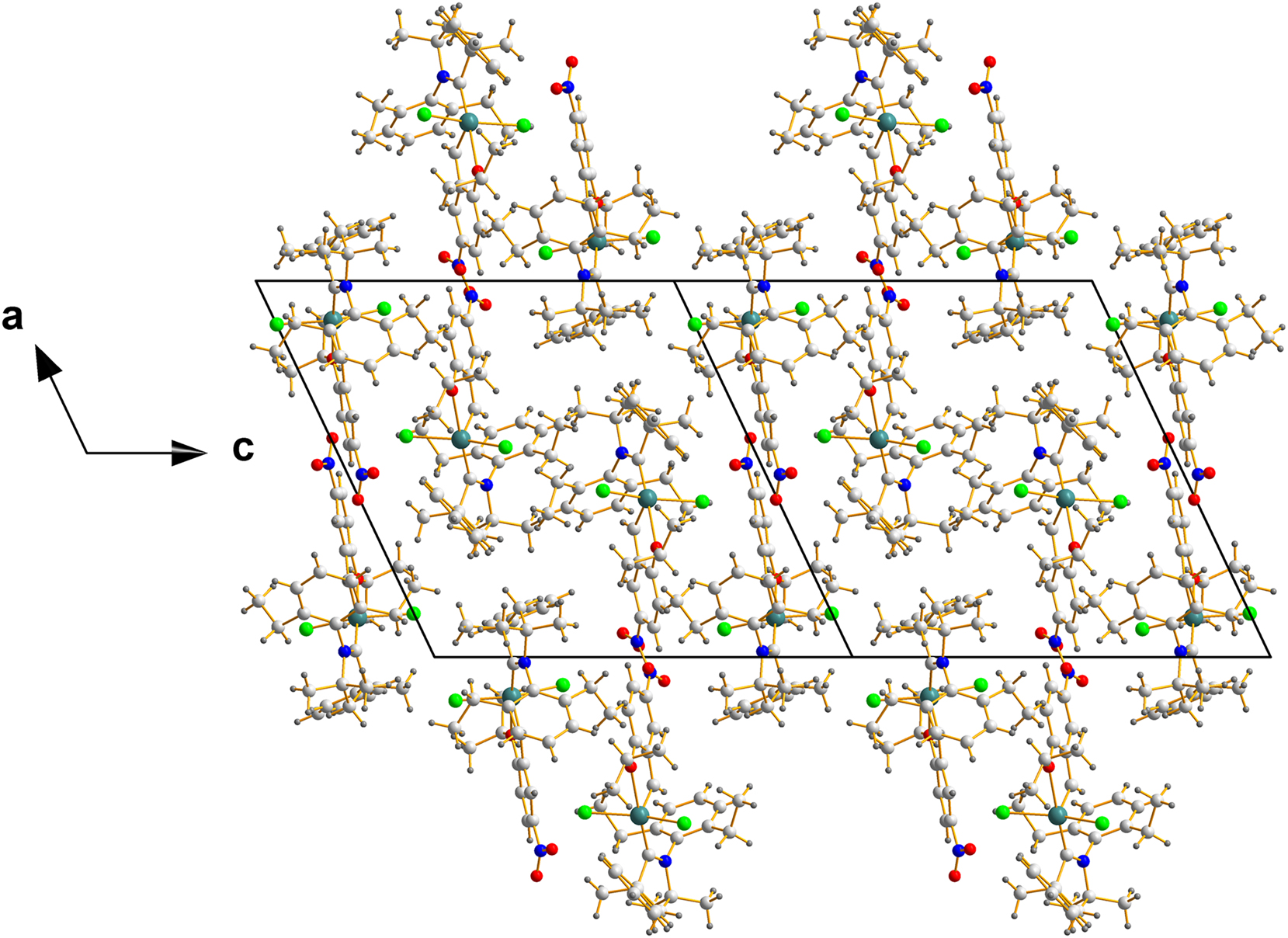

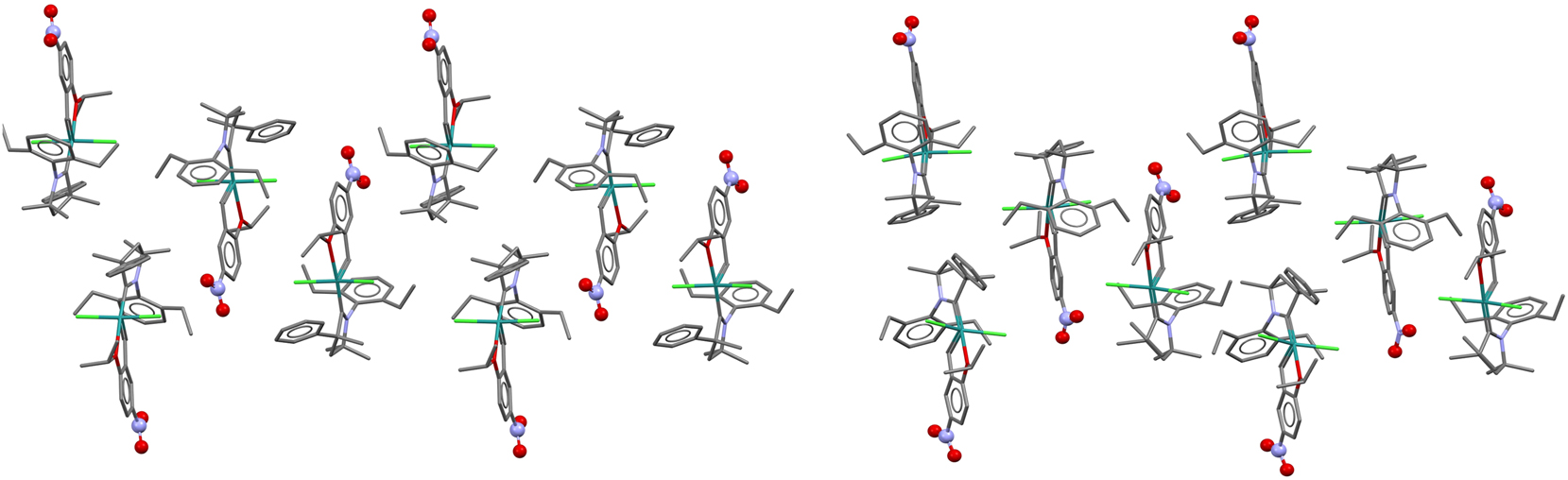

Now, as to the question of mimicking a racemate, Figure 4 shows the packing of the molecules of REPTIT 20 in their unit cell.

Packing of two unit cells in REPTIT along the c-direction – a view chosen to display the center of mass of that array, located in the middle of this ensemble and located at coordinates (0.5000, 0.4802, 0.0000), which are nearly (½, ½, 0).

In order to emphasize the point concerning the degree to which the mimic imitates the racemate , we use Figure 5, which is a small fraction of Figure 4 and showing an expanded region near the center.

The center of mass of this fragment is located at (0.5000, 0.4741, 0.0000). Note the labels of the atoms selected above. The molecules crystallize in a fashion close to being a true racemic pair.

This can also be seen in Figure 6, which compares the packing in QEGBUC and REPTIT. The packing diagram was drawn using MERCURY. 25 The view is approximately down the b-axis for both structures, but with the unit cell for REPTIT rotated by 180° about the z-axis. The packing diagram was then constructed by finding short contacts between molecules and selecting neighboring molecules that were similar in the P21/n and P21, Z′ = 2 structures. The origin of the P21 structure differs to that of the P21/n structure. Note: the “Search, Crystal Packing Similarity…” feature in MERCURY was not suitable for comparing the Z’ = 1 and Z’ = 2 structures.

A comparison showing the similarity of packing in QEGBUC (P21/n) left and pseudo-racemic REPTIT (P21, Z′ = 2) right.

8 Conclusions

This study delves into the intriguing phenomenon of racemic mimicry, a crystallization behavior where a single enantiomer arranges itself in a lattice that closely resembles a true racemic mixture. We were fortunate to discover in the published literature a fine pair of crystallographic reports describing the structures of a Grubb ruthenium(II) catalyst which, at the same time, constitute a racemic mimic pair. The two crystalline forms are a centrosymmetric structure (P21/n, Z′ = 1.0) and a structure in Sohncke space group (P21, Z′ = 2.0).

Despite the difference in space groups, the two forms exhibit remarkably similar unit cell parameters. The Sohncke structure, with its doubled Z′ value, effectively mimics the racemic arrangement through the formation of pseudo-inversion centers between Ru1–Ru1 and Ru2–Ru2 pairs, propagating throughout the lattice. This observation highlights the subtle interplay between molecular symmetry, crystal packing, and intermolecular interactions.

The discovery of racemic mimicry in this ruthenium complex adds to the growing body of evidence for this phenomenon. It underscores the importance of careful crystallographic analysis and the potential for unexpected structural motifs in chiral compounds.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: DCL and IB conceptualized the project and wrote the manuscript. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

-

Research funding: Funding from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, is gratefully acknowledged.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Groom, C. R.; Bruno, I. J.; Lightfoot, M. P.; Ward, S. C. The Cambridge Structural Database. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B: Struct. Sci. Cryst. Eng. Mater. 2016, 72, 171–179; https://doi.org/10.1107/S2052520616003954.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Bernstein, J. Polymorphism in Molecular Crystals, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 2020. ISBN 0-19-965544-8.Suche in Google Scholar

3. Jacques, J.; Collet, A.; Wilen, S. Enantiomers, Racemates and Resolutions; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1981. ISBN 0471080586.Suche in Google Scholar

4. Wu, X.; Malinčík, J.; Prescimone, A.; Sparr, C. X-Ray Crystallographic Studies of Quasi-Racemates for Absolute Configuration Determinations. Helv. Chim. Acta 2022, 105, e202200117; https://doi.org/10.1002/hlca.202200117.Suche in Google Scholar

5. Brock, C. P. Approximate Symmetry in Low-Symmetry Space Groups: P2 and C2. Cryst. Growth Des. 2024, 24, 6211–6217; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.cgd.4c00361.Suche in Google Scholar

6. Zorky, P. M. Symmetry, Pseudosymmetry and Hypersymmetry of Organic Crystals. J. Molec. Struct. 1996, 374, 9–28; https://doi.org/10.1016/s0166-1280(96)80058-3.Suche in Google Scholar

7. Wood, M. R.; Mikhael, S.; Bernal, I.; Lalancette, R. A. Erdmann’s Anion – an Inexpensive and Useful Species for the Crystallization of Illicit Drugs after Street Confiscations. Chemistry 2021, 3, 598–611; https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry3020042.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Furberg, S.; Hassel, O.; Webb, M.; Rottenberg, M. Remarks on the Crystal Structure of Asymmetric Molecules – The Beta-Phenylglyceric Acids. Acta Chem. Scand. 1950, 4, 1020–1023; https://doi.org/10.3891/acta.chem.scand.04-1020.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Schouwstra, Y. Crystal and Molecular Structures of Dl-Methylsuccinic Acid. I. A Modification Obtained by Sublimation at 70° C in Vacuo. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B: Struct. Crystallogr. Cryst. Chem. 1973, 29, 1–4; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0567740873001871.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Schouwstra, Y. The Crystal and Molecular Structures of Dl-Methylsuccinic Acid. II. Two Modifications Obtained by Slow Evaporation of Aqueous Solutions. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B: Struct. Crystallogr. Cryst. Chem. 1973, 29, 1636–1641; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0567740873005170.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Mostad, A.; Rømming, C.; Tressum, L. The Crystal and Molecular Structure of (2-Hydroxyphenyl) Alanine (O-Tyrosine). Acta Chem. Scand. B 1975, 29, 171–176; https://doi.org/10.3891/acta.chem.scand.29b-0171.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Bernal, I. The Phenomenon of Conglomerate Crystallization. VIII. Spontaneous Resolution in Coordination Compounds. VI. The Chiral Behaviour of [Trans-(P, or M)-Co (NH3)2(NO2)4]− Anions, Dissymmetric by Virtue of Their Propeller Conformation. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1986, 121, 1–4; https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-1693(00)87730-0.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Bernal, I. Kryptoracemic Crystal Structures. ACA Annual Meeting, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, 1995, Abstract 4a.1.e.Suche in Google Scholar

14. Sohail, K.; Lalancette, R. A.; Bernal, I.; Guo, X.; Zhao, L. Revisiting the Structure of (±)-[Co(en)3]I3·H2O – X-ray Crystallographic and Second-Harmonic Results. Z. Kristallogr. 2022, 237, 393–402; https://doi.org/10.1515/zkri-2022-0044.Suche in Google Scholar

15. Bernal, I.; Cai, J.; Myrczek, J. The Phenomenon of Kryptoracemic Crystallization. 2. Counterion Control of Crystallization Pathway Selection. 5. The Crystallization of (+/−)[Co(en)3][oxalato]Cl3H2O (I), (+/−)-[Co(en)3][oxalato]Br3H2O (II) and (+/−)-([Co(en)3](oxalato)I)2·3H2O (III). Acta Chim. Hung. 1995, 132, 451–474.Suche in Google Scholar

16. Bernal, I.; Cai, J.; Massoud, S. S.; Watkins, S. F.; Fronczek, F. R. The Phenomenon of Kryptoracemic Crystallization. Part 1. Counterion Control of Crystallization Pathway Selection. Part 4. The Crystallization Behavior of (+/−)-[Co(Tren)(NO2)2] Br (I), (+/−)-[Co(Tren)(NO2)2]2Br (ClO4)·H2O (II),(+/(−)-[Co(Tren)(NO2)2] ClO4 (III) and Attempts to Solve the Structure of (+/−)-[Co(Tren)(NO2)2] NO3 (IV). J. Coord. Chem. 1996, 38, 165–181; https://doi.org/10.1080/00958979608022702.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Cai, J.; Myrczek, J.; Chun, H.; Bernal, I. The Crystallization Behavior of (±)-Cis-α-[Co(Dmtrien)(NO2)2] Cl·0.5H2O 1 and (±)-Cis-α-[Co(Dmtrien)(NO2)2]I 2†(Dmtrien= 3, 6-Dimethyl-3, 6-Diazaoctane-1, 8-Diamine). J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1998, 4155–4160; https://doi.org/10.1039/a806094k.Suche in Google Scholar

18. Bernal, I.; Watkins, S. A List of Organometallic Kryptoracemates. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C: Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 216–221; https://doi.org/10.1107/S2053229615002636.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Fábián, L.; Brock, C. P. A List of Organic Kryptoracemates. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B: Struct. Sci. 2010, 66, 94–103; https://doi.org/10.1107/S0108768109053610.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Morvan, J.; Vermersch, F.; Lorkowski, J.; Talcik, J.; Vives, T.; Roisnel, T.; Crévisy, C.; Vanthuyne, N.; Bertrand, G.; Jazzar, R.; Mauduit, M. Cyclic(Alkyl)(Amino)Carbene Ruthenium Complexes for Z-Stereoselective (Asymmetric) Olefin Metathesis. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2023, 13, 381–388; https://doi.org/10.1039/D2CY01795D.Suche in Google Scholar

21. Vougioukalakis, G. C.; Grubbs, R. H. Ruthenium-Based Heterocyclic Carbene-Coordinated Olefin Metathesis Catalysts. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 1746–1787; https://doi.org/10.1021/cr9002424.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Antonova, A. S.; Zubkov, F. I. Hoveyda-Grubbs Type Complexes with Ruthenium-Pnictogen/Halcogen/Halogen Coordination Bond. Synthesis, Catalytic Activity, Applications. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2024, 93, RCR5132; https://doi.org/10.59761/RCR5132.Suche in Google Scholar

23. Gawin, R.; Tracz, A.; Chwalba, M.; Kozakiewicz, A.; Trzaskowski, B.; Skowerski, K. Cyclic Alkyl Amino Ruthenium Complexes – Efficient Catalysts for Macrocyclization and Acrylonitrile Cross Metathesis. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 5443–5449; https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.7b00597.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Brandenburg, K.; Putz, H. Diamond-Crystal and Molecular Structure Visualization (Version 4.6. 0); Crystal Impact GbR-Bonn: Germany, 2019.Suche in Google Scholar

25. Macrae, C. F.; Bruno, I. J.; Chisholm, J. A.; Edgington, P. R.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Rodriguez-Monge, L.; Taylor, R.; Streek, J. V. D.; Wood, P. A. Mercury CSD 2.0 – New Features for the Visualization and Investigation of Crystal Structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2008, 41, 466–470; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0021889807067908.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Obituary

- Obituary for Hartmut Bärnighausen

- Micro Review

- Bismuth as reactive and non-reactive flux medium for the synthesis and crystal growth of intermetallics

- Organic and Metalorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Racemic and unusual enantiomeric crystal forms of N-cycloalkyl-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamides and their biological activity

- Inorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Lead phosphate oxyapatite, Pb10(PO4)6O, with c-double superstructure

- A novel microporous uranyl silicate prepared by high temperature flux technique

- The Grubbs catalyst – dichlorido(1-(2,6-diethylphenyl)-3,5,5-trimethyl-3-phenylpyrrolidin-2-ylidene)-({5-nitro-2-[(propan-2-yl)oxy]phenyl}methylidene)ruthenium(II) – some observations on the crystallography and stereochemistry of a racemic mimic pair

- Thermal decomposition of copper(II) hydroxide and hydroxocarbonates according to X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy in operando

- New calcium perrhenates: synthesis and crystal structures of Ca(ReO4)2 and K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Obituary

- Obituary for Hartmut Bärnighausen

- Micro Review

- Bismuth as reactive and non-reactive flux medium for the synthesis and crystal growth of intermetallics

- Organic and Metalorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Racemic and unusual enantiomeric crystal forms of N-cycloalkyl-4-methyl-2,2-dioxo-1H-2λ6,1-benzothiazine-3-carboxamides and their biological activity

- Inorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Lead phosphate oxyapatite, Pb10(PO4)6O, with c-double superstructure

- A novel microporous uranyl silicate prepared by high temperature flux technique

- The Grubbs catalyst – dichlorido(1-(2,6-diethylphenyl)-3,5,5-trimethyl-3-phenylpyrrolidin-2-ylidene)-({5-nitro-2-[(propan-2-yl)oxy]phenyl}methylidene)ruthenium(II) – some observations on the crystallography and stereochemistry of a racemic mimic pair

- Thermal decomposition of copper(II) hydroxide and hydroxocarbonates according to X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy in operando

- New calcium perrhenates: synthesis and crystal structures of Ca(ReO4)2 and K2Ca3(ReO4)8·4H2O