Abstract

In this study, it is argued that a microhistorical perspective applied to historical archaeologies provides intelligibility to certain mechanisms of exercise of power and forms of resistance in the local sphere. Adopting a microhistorical approach, two primary mechanisms of social order consensus creation and contestation are explored through the creation and negotiation of symbolic capital. Micropolitics are understood as a set of poorly formalised but meaningful practices that define, model, and negotiate forms of social domination by integrating different communicative languages. Infrapolitics shape the forms of resistance and agency of subaltern groups and, by definition, are not easy to track and identify. Through the study of small empirical illustrations from the medieval period in the Basque Country, the aim is to argue that there is a correlation between the intensity and complexity of the political practices that develop in local societies and the forms of contestation of rights and cohesion mechanisms. To carry out this analysis, material, textual, mnemonic, and oral records are used.

1 Introduction

A few years ago, the Swedish archaeologist Anders Andrén published an influential book devoted to Historical Archaeology, in which he stated what he defined as the paradox of archaeology.

On one hand, the presence of written sources is seen as a great advantage since archaeology is always dependent on analogies in order to translate material culture into texts. Many people working in the prehistoric archaeologies look favourably on… “text-aided” archaeology. On the other hand, the presence of text can be seen as a great disadvantage, as it appears to leave little scope for archaeology by hampering the potential of archaeological analysis and interpretation. There is a constantly overhanging risk of tautology… to put it in extreme terms, the paradox is that those who lack texts want them and those who have texts would like to avoid them. (Andrén, 1998, p. 3)

In reality, an enormous literature has explored the complex relationship between texts and objects and, consequently, between history and archaeology (Delogu, 2012; Lucas, 2012). In ontological terms, the world of words, memories, objects, and places are not comparable to each other and cannot be juxtaposed in a simple and uncritical way. It is not possible to resort to one record to make up for the shortcomings of the other, to confirm the assumptions made by one speciality with respect to another, or to adjust the reports made by each discipline based on partial data or “models” generated by others (Moreland, 2010). Furthermore, this panorama has become more complex with the availability of new information provided by the experimental sciences, which opens up new epistemological and methodological scenarios (Haldon et al., 2018).

The “linguistic turn” has provided new conceptual tools to address these dialogues and problems. One of the most fruitful and innovative proposals to address these conflicts has been to overcome the notion of “source” to understand the processes of creation and elaboration of the different testimonies of the past in terms of acts and social practices endowed with decodable contextual meaning (Moreland, 2001). Likewise, the complex mechanisms that explain the preservation, destruction, oblivion, and transmission of these testimonies have been analysed, considering the long-term cultural biography of texts, memories, places, and things (Brown, Costambeys, Innes, & Kosto, 2013). In other words, one of the main challenges faced by historical archaeology is not to manage different types of information but to understand the contextual density that has given rise to the creation, transformation, omission, and preservation of those testimonies.

These reflections acquire maximum importance when attempting to analyse certain historical phenomena such as forms of domination, the creation of consensus, the management of dissent, and conflicts in everyday social life. Generations of historians have made political history and the history of politics by turning to public and private documents that were written for the purpose of regulating and constructing social order. Likewise, social archaeology has analysed these themes using top-down approaches, placing emphasis on the agency of the elites and the mechanisms of social display deployed by the powerful. However, a growing number of studies reveal that local settings are often more relevant to understanding collective behaviour and social practice than the models created from the agency of higher powers, or the normative frameworks preserved in the written evidence. The dialogue between local practices and global processes is a major issue for the analysis of sociopolitical domination, legitimation practices, and forms of masking social inequality (Smith, 2009).

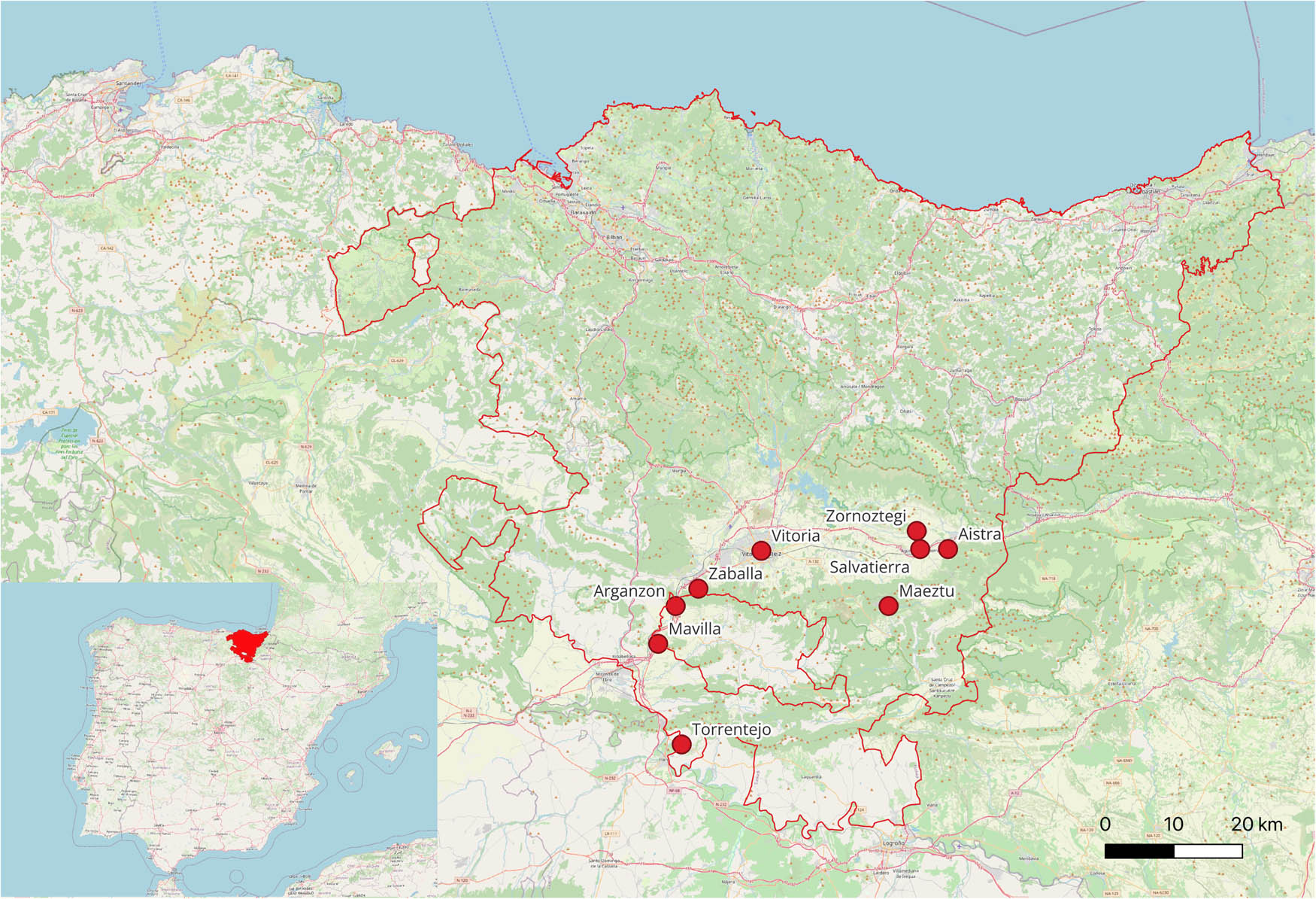

In this article, we argue that taking a microhistorical approach allows us to analyse in dialectical terms the hidden mechanisms of political regulation through daily practices in local societies. In this way, it is possible to overcome the contrast between top-down and bottom-up approaches. To achieve this, the aim is to analyse two of the main spheres around which the politics of local societies are structured: micropolitics and infrapolitics. To illustrate these themes, some case studies from medieval times in the Basque region will be taken into account, although reference will occasionally be made to the modern period. The case studies concentrate on one region because it is essential to have a coherent cultural and sociopolitical context when exploring micropolitics and infrapolitics (Figure 1).

Map with the sites cited in the article in the context of the Basque Country.

The text is organised into four sections. First, a brief explanation of the notion of microhistory is given in this archaeological analysis. Next, micropolitics are analysed from the perspective of practice theory. The analysis of infrapolitics, as defined by James C. Scott, is outlined in Section 4. Finally, in conclusion, some consequences are drawn from the analyses carried out.

2 Microhistory and Archaeology

As indicated in the introduction to this special issue, there is no single way of understanding microhistory from a conceptual and operational point of view (Berg, 2023; Ghobrial, 2019; Levi, 2019). Some scholars believe that it is a procedure to intensively analyse specific phenomena, while for others, it is a way of analysing societies, placing emphasis on agencies and practices as opposed to structuralist approaches. For some, it has been a way of constructing solid stories about the past based on experiences and memories of specific individuals or well-documented situations that, due to exceptional circumstances, have made it possible to understand their normality. Other specialists have defined the microhistorical perspective as a way of analysing global problems through particular contexts. And the list could go on. Magnússon and Szijártó’s publication provides a snapshot of this diversity of perspectives presented mainly in terms of national traditions (Magnússon & Szijártó, 2013). However, the authors who recognise themselves in this line of work generally do not consider that microhistory is solely a method or a historical current but also an analytical perspective that aspires to reconcile the distance between the different scales on which it develops social action (Ginzburg, 1994; Levi, 1994).

Since there is no single form of microhistory, neither is its impact on other disciplines uniform. Archaeology has claimed the microhistorical experience with several purposes. Faced with the increasing importance of the experimental sciences, grand narratives, and the use of “small” Big Data, some authors have claimed that microhistory is helpful for promoting other forms of archaeological knowledge creation (Ribeiro, 2019). Since one of the main achievements of microhistory has been to theorise the small scale, other authors have resorted to this experience to develop multiscale studies of complex phenomena (Riva & Grau Mira, 2022). In epistemological terms, microhistory has been used to lay claim to the importance of the evidential paradigm of an inductive nature when performing bottom-up analyses (Blanco González, 2016). Other contributions have emphasised singularising the past focusing on the small and ordinary to achieve biographies and lived experiences and identities (Mímisson & Magnússon, 2014). North American historical archaeology has claimed the importance of microhistory from a diversity of perspectives: multiscalar studies, the analysis of lower social groups, attention to everyday life, or the study of social networks and cultural variables (Orser, 2017). Another field in which the microhistorical approach has been promoted is osteoarchaeology. The creation of osteobiographies (Hosek, 2019) or the results provided by the isotopic analysis of specific individuals is allowing the study of processes such as mobility, food, lifestyles, and cultural biographies through the microscopic analysis of case studies (Britton, Crowley, Bataille, Miller, & Wooller, 2022).

Of course, there has been no shortage of authors who have questioned the microhistorical approach or its applicability to other disciplines. In particular, some of its weaknesses have been indicated in the absence of comparisons, the representativeness of normal exceptionalities, the decontextualisation of the small scale, the difficulty of creating large narratives, and the false contrast between bottom-up and top-down approaches. To these and other criticisms, Giovanni Levi has responded by arguing that to practice microhistory does not mean looking at little objects, but regarding things on a small scale (Levi, 2019).

This article uses the microhistorical approach to try and understand some structural features of everyday local societies that develop on the margins of documented history and grand narratives. Local societies are understood as arenas of interaction and competition between different agents active on different scales and political spaces. Its variable geometry is determined by the changing dimensions of the political systems that make up the local and central powers. Interest in understanding the politics of local societies through the theory of practices lies in the fact that they can illuminate domination and resistance procedures that are rarely directly traceable in the testimonies inherited from the past. Therefore, on this occasion, we will resort to a diversity of informative records, understood not only as “sources of the past” but also as actions charged with contextual meaning. In fact, this is one of the main strengths of historical archaeology.

More specifically, the mechanisms through which the forms of domination and legitimation are structured in contexts of social stress will be analysed. These include foundation rituals and the taking of possession of contested assets, as well as other forms of resistance in the Basque Country region in the medieval period. Our knowledge of foundations and transactions of rights and assets in the past depends, above all, on the existence of written testimonies. However, these are documents that are jealously guarded, away from external gazes, and also not comprehensible in their form and substance by ordinary people. How were foundations and transactions narrated and legitimised in societies in which the technology of writing was limited to certain cultural elites? In other words, what actions and gestures were performed outside the documentary scene to build consensus and agreements in the local sphere, especially when there was a latent or potential conflict around these possessions? More specifically, how were changes of ownership, donations, or assignments of rights communicated and registered in illiterate societies?

Admitting that it was necessary to resort to practices of social legitimation and communication implicitly involves accepting ordinary people’s ability for agency and contestation. It supposes, in short, the need to consider subaltern agency. But how is it visualised or conceptualised? What agency ability do subordinate groups have and what is their visibility in the archaeological record? To address this problem, the concept of infrapolitics developed in several publications by the anthropologist James C Scott will be used (Scott, 1990).

3 Micropolitics, Performance, and Rituality

The term micropolitics has been used by several disciplines and social sciences with different meanings. It is, therefore, a disputed and, at the same time, a powerful concept, because it allows the framing of a whole series of political forms that transcend legislation and formalised regulations.

Simplifying to the extreme, two main uses have been made of the concept. On the one hand, it has been used in terms of scale to refer to small politics, customs, and protocols through which local communities regulate or self-regulate. Thus, for example, Cam Gray in his study of Late Antiquity communities defined three main areas for small politics: (a) taking decisions, managing tension, and mediating conflicts; (b) the decision-making processes of individuals and households in the communities; and (c) the strategies that communities might employ for resolving disagreements or disputes that have escalated to a point where they require a specific response or solution (Grey, 2011). These are, in summary, political practices that illuminate the daily life of local realities.

Other authors have used the term to refer to everyday small-scale interventions that govern large populations’ behaviour. They do not only affect the small scale, although they are mainly visible in the analyses of local scales. In this respect, micropolitics is associated with Foucault’s notion of “the microphysics of power.” He argues that “power is not a phenomenon of the massive and homogeneous domination of one individual over others, of one group over others, of one class over others” (Foucault, 1975, p. 175). According to the French philosopher, power is distributed in society, and it is not localised and unfolds in reticular terms. In this way, power is not established but exercised in different ways, on different scales and through numerous mechanisms. Micropolitics are another component of this type of diffuse power; they are characterised by their low degree of formalisation and, therefore, by their difficult documentary or material visualisation. According to Brent J. Steele, micro-politics are based on four principles: they are anti-ideological, improvisational, close to the “real,” and a particularly limited but pragmatic conception of agency (Steele, 2011).

The semantic field of micropolitics therefore encompasses a diversity of approaches, concepts, and meanings. However, there are some recurring features. First, it focuses on spaces and forms of political action alternative to the formalisation politics. Second, they are negotiated practices aimed at generating consensus and affiliation, attenuating or masking social asymmetries. In this respect, they are assertive and generate customs and traditions. Third, due to their non-formalised nature, they are not easily traceable through the mechanisms and instruments generated by the central powers. In other words, they are rarely visible in written documentation and potentially constitute a privileged field of action for an archaeology informed by microhistory. Fourth, they generate a space for political action contested and made up of a diversity of active agents on different scales and therefore constitute a mechanism of cohesion and dissent in local societies. Fifth, micropolitics reveal themselves through rituals, gestures, practices, and performances that are comprehensible in local spheres. One case, among others, is the perambulations that travel the limits of a territory reaffirming rights and negotiating those same rights with the neighbours.

On this occasion, we will briefly focus on two specific ritual spheres that have been documented in Iberia in medieval and modern times: foundation and taking of possession rituals.

3.1 Foundation Rituals

Santa Lucía is an isolated medieval chapel in Labastida on the banks of the River Ebro in a landscape dominated by vineyards in the region of La Rioja Alavesa (the Basque Country). The present-day church (Figure 2) is a multi-layered construction, since its apse and the beginning of the nave were built in the eleventh–twelfth centuries, while the rest of the building has been transformed and rebuilt in several historical periods. The study of the written documentation and the open-area archaeological excavation undertaken have allowed us to observe a long occupational sequence that began in recent prehistory. After a long hiatus, the site again became of interest in the early Middle Ages, giving rise to the village of Torrentejo (small stream). In the tenth–eleventh centuries, a church was built associated with an aristocratic building perpendicular to the slope, in a context dominated by a dense network of local lords. In 1075, King Sancho IV of Peñalén donated the half of the village with the church of Santa María de Torrencillo to the San Millán monastery, specifying the boundaries it had at the time (Becerro Galicano Digital [doc. 597]: www.ehu.eus/galicano/id597). The monastery then tried to buy other properties in the village to become the largest local proprietor. Once it had reached this position of dominance, it undertook the reconstruction of the village church. The orientation of the new house of worship was altered, while the old one remained partially in use while the head of the new monastic church was being built. Converted into a parish church, it has remained as the last testimony of the village following its depopulation in the late Middle Ages.

Santa Lucia of Torrentejo (Labastida, Álava).

A surprising discovery was made during the excavation. A “structured deposit,” which has been interpreted as a foundational deposit, was found about 2 m south of the church façade (Figure 3). It consisted of two holes at the circulation level inside which two small earthenware jars had been carefully placed. In the first of them, covered with another fragmented ceramic form, a complete juvenile chicken was found; the second was inverted, and an eggshell was recovered. The archaeological context is contemporary with the reconstruction of the church and can be interpreted as a ritual foundational deposit.

Excavation of the foundational deposit, Santa Lucia of Torrentejo (Labastida, Álava).

This is not an isolated find in the context of the Basque Country. Similar deposits have been identified in several localities. They correspond to the foundation of town walls (Vitoria-Gasteiz, Salvatierra), the transformation of another church (Zaballa), and the probable foundation of a domestic building (Mavilla, Estabillo). The foundational deposits that provide for the deposition below the floors of animal remains or bird sacrifices are well known in other European contexts from various historical periods (Belarte & Valenzuela Lamas, 2013; Gilchrist, 2012). However, it is striking that in medieval Iberia they have only been identified to date in the Basque Country.

Two interpretations have been proposed to explain this kind of find. On the one hand, it has been suggested that this type of structured deposit should be related to the well-known propitiatory or foundational sacrifices that were common during the Roman period (Sánchez Rincón, 2012). Regardless of whether it is a survival from the past or the reworking of an ancient cult, the cultural horizon would have been given by the memory of antiquity.

A second interpretation aims to link these deposits with practices of popular religiosity, suggesting the coexistence of official and popular rituals within Christianity. The weak strengthening of ecclesiastical authorities in the Basque Country would have allowed the development of ritual practices that did not follow the official liturgy (Grau-Sologestoa, 2018).

However, neither explanation is satisfactory because they both aspire to attribute these “structured deposits” to a specific category or cultural genealogy to provide them with a framework of intelligibility according to the categories and concepts of Modernity thought. However, when undertaking this exercise, other dimensions of the rituality of premodern societies are left aside, in particular, the performative and significant nature of the foundation ritual (Bruck, 1999). On what occasions were these acts carried out? In what spatial and social contexts? Taking into account the features of the deposits and the associated archaeological contexts, as well as their repetitive and standardised nature, it could be thought that we are looking at participated practices attended by an audience that recognised and bestowed certain meanings on the rite. These deposits have been found in potentially conflicting sociopolitical contexts given that the realisation of the new architectures significantly transformed the spatial and social order of the local community. In the case of Torrentejo, the reconstruction of the church by the San Millán monastery, nullifying the previous place of worship, represented much more than an architectural reform. It was a sign and an instrument of domination of the local community in a critical period for San Millán. It is no coincidence that in those same years, the Becerro Galicano (1185) was produced, at the time when the situation of the monastery was most vulnerable (Peterson, 2008). But it is also the result of the monastery’s expansionist policy the village, which ended up becoming the main property owner and source of authority.

In the case of Zaballa, the transformation of a private church into a parish church was another critical moment in its history and, in general, for the local community (Quirós Castillo, 2012). Likewise, the construction of a walled enclosure in previously inhabited places, as in the case of Vitoria-Gasteiz or Salvatierra, involved an appropriation of urban space, but above all, the formation of political communities that resorted to rituals that generated a shared social memory. The case of Mavilla is much more ambiguous due to the small area excavated.

In summary, these foundation rituals must be understood as symbolic struggles aimed at generating symbolic capital through public acts that define social life. As P. Bourdieu pointed out, the legitimation and maintenance of social order is only sometimes the result of a net imposition through the use of force and is also a daily symbolic struggle for the production of common sense (Bourdieu, 1988).

3.2 Taking of Possession Rituals

On 4 October 1615, a strange ritual was held in the old chapel of Nuestra Señora de Arganzón, a church founded a thousand years ago near the royal villa of La Puebla de Arganzón (Burgos). On that day, Paulino de Gordojuela, curate of the town and representative of the bishop of Calahorra y La Calzada, and Juan Fernández de Antezana, mayor of La Puebla, took the general minister of the Franciscan province of Cantabria, the friar Juan de Domaica, by the hand and entered the chapel. Then, the friar closed the doors of the church and, after remaining inside for a time, opened them again to welcome all the people who had come to this taking of possession ritual. Next, a mass was held, the Holy Sacrament was placed in a silver monstrance on the altar, and Juan de Domaica himself gave the keys of the church to Friar Antonio de Zornoza, who from then on would be in charge of Santa María. A little later, the Franciscan minister went to drink water from the fountain near the chapel; he walked to the source of the stream that fed the fountain where there was a boundary stone and there he sat in front of the attendees. In this way, Fray Juan de Domaica took possession of the Arganzón chapel and its property to establish a Franciscan convent. Arganzón was a village founded in Late Antiquity and subsequently abandoned. Only the church with an annexed building was preserved, as well as some land, all within an enclosure.

We know of this ritual because it was recorded in a written document included in a file kept in Calahorra Cathedral Archive.[1] Among other texts, the file includes the deed by which the Arganzón chapel was purchased to find the monastery, the donation made to the Franciscan friars, and the conditions in which the sale was made. Noteworthy among the conditions was the commitment on the part of the Franciscans to welcome the residents of La Puebla de Arganzón who annually made a pilgrimage to the old chapel where they held litanies and other religious ceremonies. It was a significant place for the local community and was part of its locative identity. Likewise, the file contains a statement from the bishop of Calahorra himself in which he recalled that the Arganzón spring belonged to him and that when he passed nearby in his litter he always stopped to drink because the water was very cool. Reading between the lines, we find ourselves looking at a property, an early medieval chapel, a place, the depopulated village of Arganzón, and a cohesive artefact charged with meaning for the local community, which was changing ownership. This change in ownership constituted a potential stressor of the established order and shared memories. Therefore, a whole series of ritualised practices were set in motion to legitimise the transfer of ownership, the taking of possession, and the maintenance of certain rights for the people of the locality. The confirmation that it was a potentially conflicting situation can be seen in other documents kept in the same archive. They describe the way in which the processions were carried out on the occasion of the Arganzón pilgrimage, the desire to move the monastery to a position closer to the town of La Puebla de Arganzón, and the request for resources to expand and modify the monastery.

The archaeological excavation of the last monastery church and the cloister built in the seventeenth century and transformed in the eighteenth showed that the fears were well founded. Although at first the medieval chapel was used as the centre of worship for the new religious community, later a new ground plan was built. Consequently, the old medieval church was deconstructed both physically and symbolically (Figure 4). In addition, the fountain was reconstructed monumentally in the eighteenth century as part of the reform of the convent by order of the friars themselves (Figure 5).

Deconstructed convent church of Arganzon (La Puebla de Arganzón, Burgos).

Postmedieval fountain of Arganzón village (La Puebla de Arganzón, Burgos).

About 40 km to the east of Arganzón is the medieval town of Maeztu (Arraia-Maeztu). Another document, this time dated 28 November 1179, recalls how the domina Teresa donated to the Cathedral and the bishop of Calahorra her house in Puente de Maeztu, which had been converted into a hospital. She also donated a granary, an orchard, the times assigned for the use of a mill and other rights. The text records how the bishop, in the presence of numerous witnesses, accepted the offering and went to the hospital where Teresa had him enter physically and take possession of it, following the local custom (et fecirum dominum eius et possesorem ut sepe dictum est secundum consuetudinem terre) (Rodríguez de Lama, 1979, n. 272, pp. 49–50). In this case, the archaeological surveys have not revealed the place where the hospital was built, although we know it was close to the chapel and the San Juan bridge, which was rebuilt in 1785 (Azkarate Garai-Olaun & Palacios Mendoza, 1996).

These documents suggest that this type of ritual was common in the taking of possession. They were ceremonies carried out publicly following customary norms. Having said that, since both documents clearly record the donation and the taking of possession, why was it necessary to resort to unwritten means of communication? In the event of disputes or conflicts, we know that the evidentiary instruments used in lawsuits were precisely the texts. If it was such a widespread practice, why are these rituals only occasionally found in preserved documents? Why are some taking of possession rituals described in detail and others only generically? Unlike the numerous texts that narrate the foundation of a place of worship, a monastery or other constructions in which the formula “built with my own hands” was used rhetorically (Larrea & Viader, 2005, pp. 200–202), in takings of possession they describe specific acts with precision.

Few studies have made this type of takeover ritual. However, a review of those most relevant from the medieval and modern periods in Iberia allows us to identify some general trends (Puñal Fernández, 2002). First of all, its presence in the written documentation is always minimal. In a study carried out on 25,000 early medieval Catalan diplomas, only five described taking of possession rituals (Rodríguez-Escalona, 2021). Second, the documents that transcribe taking of possession rituals are present in practically all the historical periods for which we have documentary records of a certain entity. The oldest known examples on the Iberian Peninsula are from the eleventh century, although there are testimonies in late medieval and modern notarial protocols, monastic funds, and other types of sources throughout the Middle Ages and the post-medieval period (Beceiro Pita, 2009; Monsalvo Antón, 2015; Oliva Herrer, 2002; Puñal Fernández, 2002; Rodríguez-Escalona, 2021; Sánchez Sánchez, 2019). Third, their geographical distribution is very widespread, as they have been found in Andalusia, Catalonia, Castilla, Galicia, the Basque Country, as well as Latin America (Smietniansky, 2016). Fourth, although some features are repeated, there are many variants or differences determined by various factors. Taking possession of a house could include lighting the fire, opening and closing the door, walking around the new acquisition, handing over the keys, soil from the ground or straw from the roof, the proclamation of the new possession spoken out loud, etc. (Puñal Fernández, 2002; Rodríguez-Escalona, 2021). In the case of land appropriation, several practices have been documented that symbolise the carrying out of agricultural work: setting boundaries with signs or markings, marking the boundaries with a plough, cutting vine shoots, pulling up grass or stones, etc. The taking of physical possession of the property, the tour of the new property, and the exclusion of the former owners constitute the basic lexicon found in different periods and places. Also, the transfer of the property has its own ritualisation, which can include the symbolic transfer through a ring, a wooden stick, a bell rope, or the keys (Rodríguez-Escalona, 2021). In summary, the repertoire of gestures and practices is wide, but they are all performed in public, reinforced through orality, and understood by local communities. Fifth, the degree of detail with which these rituals are described is different. Sometimes an almost anecdotal reference is made to the ritual, while in cases like that of Arganzón they adopt a very explicit narrative form. In the sixth place, these ceremonies that integrate gestures, oral speeches, and collective participation do not replace or diminish the importance of the written document. The preparation of a document is in itself a public act (Barrett, 2023) that is carried out at the conclusion and as closure of the whole process.

On the other hand, it must be considered that not all takings of possession have given rise to a written document and that there are also gradations in terms of the degree of detail with which the rite and the oral speech were transcribed/transferred to written memory. So why did this action only sometimes take place? I believe it was a resource that was activated in the event of conflict – potential, latent, or evident – between different agents.

Consequently, taking of possession rituals constitute a complex rhetorical mechanism that integrates different communicative languages destined to generate legitimacy in contexts of negotiation and potential contestation of rights. The microhistorical approach reveals, in short, that it was not enough to have the legal backing of the written text, but that it was also necessary to weave memories and consensus into symbolic and spatialised universes, even if they were contingent and tactical (Torre, 2011).

3.3 Micropolitics and Foundation and Taking of Possession Rituals

Foundation and taking of possession rituals are two forms of micropolitics aimed at producing legitimacy, building balances, and generating consensus between conflicting interests and social groups. Foundation rituals and takeovers are two forms of micro-politics aimed at producing legitimacy, building equilibrium, and generating consensus among opposing interests and social groups. Although written proofs were the instruments used in medieval and modern courts, political action unfolded on different scales and through different mechanisms that were not mutually exclusive.

The archaeological study of ritualism is a controversial subject, both because of the ontological difficulty in overcoming the Western opposition between ritual and everyday life (Bruck, 1999), ritual and ceremony (Groot, 2008), and because of the tendency to attribute a ritual meaning to those records that are not easily understood (Merrifield, 1987).

Taphonomic approaches to ritual have also not been lacking (Groot, 2008). However, in recent years, there has been a large increase in archaeological and historical studies that have addressed the social meaning of ritual in social life by resorting to anthropological approaches, especially in Scandinavia and the Anglo-Saxon sphere (Pluskowski, 2011).

According to the anthropologist Stanley Jeyaraja Tambiah, “ritual is a culturally constructed system of symbolic communication. It is made up of patterned and ordered sequences of words and acts, often expressed in multiple media, whose content and arrangement are characterised in varying degrees by formality (conventionality), stereotypy (rigidity), condensation (fusion) and redundancy (repetition). Ritual action in its constitutive features is performative in these three senses” (Tambiah, 1985, p. 128). As a communication instrument, by definition rituals are participatory acts directed at audiences who not only attend the ritual and recognise the message and the meaning of the signs but also participate in the ritual by attributing values and building custom and habitus. In other words, ritual is not just communication, but also a powerful mechanism for constructing reality and creating social relationships. In the words of C. Bell, “ritualisation, as a strategic mode of action, is concerned with power and the legitimation of social order” (Bell, 1992, p. 170). From this perspective, when trying to define their circumstances and meanings in terms of social practices, it is not so important to determine whether these rituals have their roots in the Roman world or in certain traditions or forms of religiosity.

These approaches can be applied to both foundation and taking of possession rituals. However, there are important differences between the two, at least regarding the performative process. In material terms, the foundation rituals analysed are more visible because they involve making “structured deposits.” But in turn, they have no textual translation and are therefore invisible in the historical documentation. This is due to the fact that the symbolic capital generated in the participated ceremony is immediately transferred to the new architecture, so that there is a direct association between the act and the result. Instead, in the case of a taking of possession this transfer occasionally occurs. Is it a mechanism for reinforcing the message or a multilayered communication mechanism, in the sense that it targets a diversity of social groups? As a starting point, it would have to be argued that gesture, speech, and writing take on different functions throughout the process, which is not limited to the rite itself. Thanks to the donation of the Maeztu Bridge Hospital, we know that rituals, in their performative dimension, were part of local customs. Although the oral and gestural messages may be indispensable, this is not the case with the written message. And although the bias dependence on written evidence when it comes to the history of past societies places other communication mechanisms in a secondary role, this context forces us to resituate the production of the written record at a subordinate level with respect to gestures and orality. The rituals are aimed, first of all, at an audience for which micro-politics are effective and assertive. In other words, micropolitics articulated through rituals are potent mechanisms in the creation of social memories (Fentress & Wickham, 1992). Once the act of taking possession is finalised, the production of a written record enters the scene. It marks the conclusion of the ceremony by generating formal legitimation instruments that are intended to be used in other instances. In this respect, the recourse to writing does not aim to reinforce the meaning of the ritual, as some authors have pointed out (Puñal Fernández, 2002), since it operates on other levels of legitimacy and application. Gestures and speaking generate memories, traditions, and experiences that are powerful instruments for promoting social peace.

In summary, foundation and taking of possession rituals aim to rework, sanction, and negotiate social relations. The recourse to a diversity of communication mechanisms and forms of sanctioning these rituals illuminates blind spots of social life that are only occasionally reflected in material or written records. Nevertheless, they are of remarkable importance for understanding the mechanisms by which social life is organised.

4 Infrapolitics and the Archaeological Records

If the visibility of micro-politics in the testimonies of the past is sometimes problematic, the challenge is greater when reference is made to infrapolitics. This concept was introduced and developed by the anarchist anthropologist J. C. Scott in various works centred on the peasants of southeast Asia and their resistance strategies (Scott, 1976, 1985).

In particular, in his work “Domination and the Arts of Resistance. Hidden Transcripts,” he defines subaltern politics in the following terms:

If formal political organisation is the realm of elites (for example, lawyers, politicians, revolutionaries, political bosses), of written records (for example, resolutions, declarations, news stories, petitions, lawsuits), and of public action, infrapolitics is by contrast, the realm of informal leadership and non-elites, of conversation and oral discourse, and of surreptitious resistance. The logic of infrapolitics is to leave few traces in the wake of its passage. By covering its tracks, it not only minimises the risks its practitioners run but also eliminates much of the documentary evidence that might convince social scientists and historians that real politics was taking place. (Scott, 1990, p. 200)

Based on ethnographic and documentary observations, James C Scott argues that subaltern groups daily effect a circumspect struggle beyond the visible end of the spectrum. In this way, they avoid direct confrontation while continuously questioning and eroding the domination mechanisms of the dominant groups, generating a true hidden discourse. Its recurrence and multiplication have distorting effects on these mechanisms, without destabilising them through direct conflict (Scott, 1990). In this sense, infrapolitics are defined in terms of discretion and practices, as well as in terms of significance, when they tend to negate the capacity for subordinates’ political agency. This conceptual framework has been progressively embraced by several scholars, giving rise to important contributions (Marche, 2012).

Three fundamental features of these infrapolitics are that, on the one hand, they unfold in everyday form (everyday forms of resistance) taking advantage of the loopholes and spaces for social action that are far from the permanent control of the dominant sectors. On the other hand, they are low-profile practices, but they have a multiplier effect in terms of scale (gutta cavat lapidem). However, the most important characteristic is that, by definition, they hardly leave a trace in their wake. They are, therefore, forms of active resistance but are not always visible to or understandable by the elites. Therefore, they are one of the subalterns’ many fields of political action.

In his works, James C. Scott has identified, among other forms of infrapolitics, poaching, squatting, desertion, evasion, foot-dragging, dissimulation, theft, tax evasion, avoidance of conscription, etc. (Scott, 2013). However, I believe that the semantic field of infrapolitics could also expand to encompass a whole series of subaltern group practices and forms of resistance. Thus, for example, in modern times, it was common for nomadic gypsy groups to camp near churches and chapels to receive, where appropriate, ecclesiastical immunity. The decision of the medieval Moors to engage in artisanal activities that were despised by Christians could also fit within this extended definition of infrapolitics.

However, just because infrapolitics leave no footprint and are very difficult to trace, especially in written documentation, this does not mean we cannot try to identify them. And an archaeology informed by microhistory makes it possible to give new meaning to finds that often go unobserved or are little expressive of the daily resistance practices of the weak. On this occasion, we will briefly focus on two topics: poaching and grain pits.

4.1 Poaching

Zornoztegi is a village situated on an elongated hill on the eastern plain of Álava. The site was occupied continuously from the late Roman period to the thirteenth century (Figure 6). After that it was progressively abandoned and by the fifteenth century, it only had one inhabitant. The excavation of this deserted village has provided a detailed account of a non-hierarchical peasant community (Quirós Castillo, 2019). While it is true that it has been possible to recognise social differences within the local community, especially from the eighth century on, they have never been substantially relevant. The wealthy peasants had a lifestyle and material culture very similar to that of their neighbours. This conclusion has been obtained by studying some of the records found during the open-area excavation. In particular, it is worth focusing on the archaeozoological remains because they provide information, not only about dietary patterns but also, above all, about the activities that were carried out in the village and the characteristics of the local economy. As is common at historical sites, three species are best represented: cattle, pigs, and sheep/goats. The study of cattle slaughter patterns shows the predominance of adult and elderly specimens, which leads to the belief that most of the cattle were raised as work animals. The sheep and goats were also mostly adult individuals and were raised to produce wool, milk, and other secondary products. Pigs, on the other hand, reveal different types of patterns. But what draws our attention is the presence, in very small numbers, of red deer and roe deer. Peasants occasionally hunted deer between the late Roman period to the late Middle Ages.

Zornoztegi deserted village (Salvatierra, Álava).

Among the different forms of infrapolitics that James C. Scott mentions most frequently, poaching is one of the most widespread mechanisms among peasant societies. Hunting has been in the Middle Ages a mechanism of identity construction of the elites, so that there are numerous rules that exclude and pursue poaching (Morales Muñiz, 2001). Thus, the medieval provides a golden opportunity to evaluate the importance of poaching as a form of hidden resistance by the weaker members of society. The study of archaeozoological remains found in villages and peasant settlements constitutes, therefore, a procedure to identify poaching. And in this case, the rubbish reveals hidden practices.

Despite the fact that hunting and fishing were considered important economic activities for people of different social statuses in the medieval period, there is a growing consensus that considers hunting and the consumption of major wild species a characteristic of high status (Loveluck, 2013). Some surveys carried out in Britain (Sykes, 2015), France (Clavel & Yvinec, 2010), and Italy (Salvadori, 2015) revealed the paucity of wild animals in the different assemblages. Furthermore, these surveys challenged some of the previous historical accounts that defended the importance of forests and uncultivated spaces during the early Middle Ages, after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. Studies by scholars such as M. Montanari on the diet of early medieval societies had argued that game was part of the diet of all social groups. Large game hunting (deer, wild boar, and roe deer) would have been reserved for the dominant groups, although it was a “community affair” as a socialising moment that brought together all the inhabitants (Montanari, 1979). However, F. Salvatori has shown that the consumption of wild animals (deer, wild boar, hares) never exceeded 1 or 2% of all Italian contexts between Late Antiquity and the late Middle Ages. Furthermore, there is a correlation between high-status sites and the consumption of wild species. Indeed, it can be argued that large game hunting constituted a critical instrument in the identity construction of medieval aristocracies and nobility (Salvadori, 2015).

The studies carried out on the archaeozoological remains found in the rural villages, high-status sites, and small towns of Alava (Basque Country) close to Zornoztegi confirm this trend (Grau Sologestoa, 2019). Normally, the percentage of wild animals rarely exceeds 1% of the number of identified specimens found. There are, however, some exceptions. At Aistra, a high-status site, there is a large presence of deer and roe deer, especially in the sixth- to seventh-century phase, when they account for more than 5% of the total. Although this data is to be expected, bearing in mind that traces of collective feasting have been found in this aristocratic enclave (Quirós Castillo & Reynolds, 2023), the values found in other villages are more striking. Particularly noteworthy is the discovery of wild animals such as deer and roe deer in the early medieval village that preceded the founding of the small town of Salvatierra. Also, in the medieval village of Zaballa, the percentages are considerably above the average between the eighth and fifteenth centuries, including the consumption of deer (Quirós Castillo, 2012). In general, however, in almost all the rural villages excavated to date in Álava, wild animals (Grau-Sologestoa, 2015) have been recovered in greater or lesser quantities. Taking these data into account, it can be suggested that poaching of large animals was widespread among rural villages in the medieval period in Alava, as the rest of Iberia (Morales Muñiz & Morales Muñiz, 2001). Although not a frequent activity, it was undertaken by the peasants. James C. Scott’s observations have shown that poaching was understood by the peasantry as a form of symbolic and ideological dissidence by coming into possession of what was denied to them (Scott, 1990).

In summary, although peasants had access to forest resources, wild animals played little part in their diet. Nevertheless, poaching was frequent in the medieval period in Iberia.

4.2 Hiding the Crops: Underground Silos

In the early medieval period, the domestic spaces of the depopulated areas of Zornoztegi or Zaballa consisted of individual domestic units that contained buildings, enclosures, and open spaces that could be interpreted as intensively cultivated market gardens (Figure 7). However, one of the most visible elements in all these villages was an area within the domestic space in which several pits of different characteristics and sizes were concentrated. These have generally been identified as grain-pits. Without a doubt, the presence of globular or cylindrical holes excavated in the rocky substrate is one of the most common features of the rural settlements of Iberia and other places in the Mediterranean (Sigaut, 1978). Their presence is so frequent and their visibility in excavations so evident that they have become one of the main themes in the study of ancient agrarian practices.

Medieval silos of Zaballa (Iruña de Oca, Álava).

Having said that, they are difficult artefacts to interpret. First, because they had generally been re-filled with domestic waste, as they were reused as a rubbish dump. Therefore, inferring their original function is not easy. In fact, not all pits were silos designed for the anaerobic storage of cereals, nor were silos the only means of storing cereals, fruits, and other foods in the past. Second, they were abandoned precisely when they were no longer able to maintain their anaerobic conditions because they had been altered to the point that they could not be closed hermetically. Therefore, it is difficult to estimate the dimensions and characteristics of the pits when they are in use. Third, due to their polyfunctional and polysemous nature, they are not easily traceable through the mechanisms and instruments generated by the central powers. In addition to the dimensional criterion, and the location of these silos in relation to domestic structures or other constructions has made it possible to propose a diversity of readings. Some authors have considered that certain types of silos constituted a mechanism in the hands of the peasantry to mitigate the systemic risk of pre-industrial agriculture, storing grain reserves to face years of scarcity. On other occasions, the presence of large silos in castles, churches, and other places in the hands of the elites has led to the belief that they would have been instruments for storing income with which to speculate and take advantage of the lean years. Sometimes they have been related to phases of agricultural growth at a time when an increase in their size is noted. At other times, they have been linked to commercial practices. In Iberia, most medieval silos are associated with domestic units and individual buildings, but in Languedoc, “silo fields” were set up for the entire community to share their management and risk. Furthermore, several ethnoarchaeological projects carried out mainly in the Maghreb have recovered important information about the use of these grain pits in contemporary times (Alonso et al., 2017). Fourth, there is a profound asymmetry between the numerous silos found in archaeological excavations and their paucity in written documentation. In donations, sales, or acts recorded in medieval texts, references to barns and granaries are more common than those that mention silos. And furthermore, they appear in the hands of peasants or farmers. This is the case, for example, of the donation made by Alvaro Díaz and his wife Sancha of their bodies and souls to the monastery of Valpuesta in the year 1132, which included a threshing floor, a well, a land, and a silo (Ruiz Asencio, Ruiz Albi, & Herrero Jiménez, 2010, n. 168, pp. 401–404).

Now, perhaps the grand paradox of grain pits lies in the fact that, on the one hand, they constitute the most visible entity in archaeological excavations, to the point that it is believed that more than 80% of the early medieval rural sites in Iberia could have been characterised thanks to the finds of silos (Vigil-Escalera Guirado, 2013). On the other hand, they are practically invisible in written documentation. But they were also invisible when they were in use. The fact that they were underground and located in certain parts of the villages has led to the belief that storage in silos by the peasantry allowed part of the crops to be hidden. Ethnoarchaeological evidence has confirmed this behaviour on several occasions (Ouerfelli, 2013).

In summary, it is not intended to argue that poaching and all grain pits empowered the peasantry in terms of infrapolitics, and in fact, the silos established around churches were mainly there for visibility (Roig Buxó, 2013), and under certain circumstances, wild animals might be hunt by commoners. Nevertheless, in some cases, underground storage could have favoured those concealment practices (Tejerizo García & Carvajal Castro, 2021).

In other words, we do not have to look for a specific artefact or archaeological record that defines subaltern infrapolitics, but rather we should understand in terms of their practices and agency the conditions in which certain features favoured these forms of active resistance.

5 Final Remarks

The central argument we wished to support in this article is that micropolitics and infrapolitics are two sides of the same coin. They constitute two of the basic mechanisms for the production and reproduction of local societies and allow social life to be analysed in dialectical terms through the construction and destruction of symbolic capital.

Micropolitics aim first to regulate dissent and naturalise forms of domination through the continuous (re)negotiation of asymmetric relations by crafting socially accepted customs and traditions. They are structured in local spheres where rituals are not only understood and accepted but also generate shared social memories that reinforce the social order. Micropolitics are deployed through ritual formulas that integrate diverse communicative mechanisms with different functions, audiences, and effects.

Infrapolitics are intended to destabilise and call into question – implicitly and with little visibility – the balances created through micropolitics and their rituals. Taking advantage of the limitations and interstices of the domination and control of authority mechanisms, low-intensity (apparently) spaces of resistance are created. But just because they do not generate a direct and obvious response does not mean that they are not effective and highly destabilising.

The analysis carried out allows us to maintain that there is a correlation between the intensity and complexity of the political practices that develop in local societies and the forms of contestation of rights and cohesion mechanisms. It could be suggested that micropolitics are enriched, above all, in contexts of social stress, where it is necessary to build collective social memories. And I suspect that the same could be said in the case of infrapolitics, although it is much more difficult to keep track of them.

Both spheres render the agency capacity of the subaltern groups visible and the procedures through which the elites negotiated and built the equilibrium that allowed them to guarantee their pre-eminence with the lowest social cost. Paradoxically, both mechanisms rarely have a place in the history and legal production of formalised political structures. Nevertheless, reading between the lines, it can be argued that their relevance was significant in everyday life.

Historical archaeologies in general, and medieval archaeology in particular, continue to carry the heavy legacy of the persistent pre-eminence attributed to written sources by historical disciplines. And although the exponential growth of material records will end up unbalancing this methodological tension, the qualitative leap will take place when the “sources” are no longer just sources, when there is a deeper understanding of the different functions and meanings of the various communicative forms in their context and when, in summary, historical archaeology ceases to be merely a study of the materiality of the societies of historical periods to move towards a multidimensional discipline in epistemological and methodological terms. And on this itinerary, microhistory as an intellectual project has much to say. Not only to unravel the mini-stories of localities or singular events, but to harmonise the grand narratives with the group and individual agencies, the top-down perspectives with the bottom-up ones, and the stories transmitted through different records with the underlying social practices. The dialogue between history and archaeology should not continue to be structured around the “sources” but around the meaning and concepts constructed in each instance.

Acknowledgements

Carlos Tejerizo and Alfonso Vigil-Escalera have improved the text with their comments, as well as the anonymous reviewers.

-

Funding information: This research was supported by the project “Archaeology of the local societies in Southern Europe: identities, collectives and territorialities (5th–11th centuries)” (PID2020-112506GB-C41) funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, and the Research Group in Heritage and Cultural Landscapes (Government of the Basque Country, IT1442-22).

-

Author contributions: The author confirms the sole responsibility for the conception of the study, presented results, and manuscript preparation.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest. The author is a Guest Editor for the Special Issue on Microhistory and Archaeology. He was not, however, involved in the review process of this article. It was handled entirely by other Editors of the journal.

-

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the BIBAT Museum (Torrentejo, Zaballa, and Zornoztegi) and the Junta de Castilla y León (Arganzón), but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available.

References

Alonso, N., Cantero, F. J., López, D., Montes, E., Prats, G., Valenzuela-Lamas, S., & Jornet, R. (2017). Etnoarqueología de la basura: almacenaje en silos y su reaprovechamiento en la población Ouarten de El Souidac (El Kef, Túnez). In J. F. Eraso, J. A. Mujika, A. A. Valbuena, & M. G. Diez (Eds.), Miscelánea en homenaje a Lydia Zapata Peña (1965–2015) (pp. 31–67). Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea.Suche in Google Scholar

Andrén, A. (1998). Between artifacts and texts. Historical archaeology in global perspective. New York: Springer.10.1007/978-1-4757-9409-0Suche in Google Scholar

Azkarate Garai-Olaun, A., & Palacios Mendoza, V. (1996). Arabako zubiak = puentes de Álava. Vitoria-Gasteiz, Gobierno Vasco.Suche in Google Scholar

Barrett, G. (2023). El contexto social del documento: Tiempos y lugares de documentación en la Península Ibérica altomedieval (711–1031). Studia Historica. Historia Medieval, 41(2), 9–33.10.14201/shhme2023412933Suche in Google Scholar

Beceiro Pita, I. (2009). El escrito, la palabra y el gesto en las tomas de posesión señoriales. Studia Historica. Historia Medieval, 12, 53–82.Suche in Google Scholar

Belarte, M. C., & Valenzuela Lamas, S. (2013). Zooarchaeological evidence for domestic rituals in the Iron Ages communities of North-Eastern Iberia (present-day Catalonia) (sixth-second century BC). Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 33(2), 163–186.10.1111/ojoa.12008Suche in Google Scholar

Bell, C. (1992). Ritual theory, ritual practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Berg, M. (2023). Introduction: Global microhistory of the local and the global. Journal of Early Modern History, 27, 1–5.10.1163/15700658-bja10060Suche in Google Scholar

Blanco González, A. (2016). Microhistorias de la Prehistoria Reciente en el interior de la Península Ibérica. Trabajos de Prehistoria, 73(1), 47–67.10.3989/tp.2016.12163Suche in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, P. (1988). Espacio social y poder simbólico. Revista de Occidente, 81, 97–119.Suche in Google Scholar

Britton, K., Crowley, B. E., Bataille, C. P., Miller, J. H., & Wooller, M. J. (2022). Editorial: A Golden age for strontium isotope research? Current advances in paleoecological and archaeological research. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 9, 820295. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.820295.Suche in Google Scholar

Brown, W., Costambeys, M., Innes, M., & Kosto, A. J. (2013). Documentary culture and the laity in the early Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139177993Suche in Google Scholar

Bruck, J. (1999). Ritual and rationality: Some problems of interpretation in European archaeology. European Journal of Archaeology, 2(3), 313–344.10.1179/146195799799726487Suche in Google Scholar

Clavel, B., & Yvinec, J. H. (2010). L’archéozoologie du Moyen Âge au début de la période moderne dans la moitié nord de la France. In J. Chapelot (Ed.), Trente ans d’archéologie médiévale en France. Un bilan pour un avenir (pp. 71–88). Paris: CRAHM.Suche in Google Scholar

Delogu, P. (2012). Storia e archeologia, sorelle gelose. In Riccardo Francovich e i grandi temi del dibattito europeo: Archeologia, storia, tutela, valorizzazione, innovazione (pp. 59–66). Firenze: All’Insegna del Giglio.Suche in Google Scholar

Fentress, J., & Wickham, C. (1992). Social memory. Oxford: Blackwell.Suche in Google Scholar

Foucault, M. (1975). Vigilar y Castigar. Nacimiento de la prisión. Madrid: Siglo XXI.Suche in Google Scholar

Ghobrial, J. P. A. (2019). Introduction: Seeing the world like a microhistorian. Past and Present, 242(S14), 1–22. doi: 10.1093/pastj/gtz046.Suche in Google Scholar

Gilchrist, R. (2012). Medieval life: Archaeology and the life course. Woodbridge: Boydell Press.10.1515/9781846159749Suche in Google Scholar

Ginzburg, C. (1994). Microstoria: Due o tre cose che so di lei. Quaderni Storici, 86(2), 511–539.Suche in Google Scholar

Grau Sologestoa, I. (2019). Estudio de los materiales faunísticos (mamíferos y aves) y de la industria ósea del yacimiento de Zornoztegi. In J. A. Quirós Castillo (Ed.), Arqueología de una comunidad campesina medieval: Zornoztegi (Álava) (pp. 377–400). Bilbao: University of the Basque Country.Suche in Google Scholar

Grau-Sologestoa, I. (2015). The zooarchaeology of medieval Alava in its Iberian context. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports Limited.10.30861/9781407314457Suche in Google Scholar

Grau-Sologestoa, I. (2018). Pots, chicken and building deposits: The archaeology of folk and official religion during the High Middle Ages in the Basque Country. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 49, 8–18.10.1016/j.jaa.2017.11.002Suche in Google Scholar

Grey, C. (2011). Constructing comunities in the late Roman countryside. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511994739Suche in Google Scholar

Groot, M. (2008). Animals in ritual and economy in a frontier community. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.10.5117/9789089640222Suche in Google Scholar

Haldon, J., Mordechai, L., Newfield, T. P., Chase, A. F., Izdebski, A., Guzowski, P., … Roberts, N. (2018). History meets palaeoscience: Consilience and collaboration in studying past societal responses to environmental change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(13), 3210–3218.10.1073/pnas.1716912115Suche in Google Scholar

Hosek, L. (2019). Osteobiography as Microhistory: Writing from the Bones Up. Bioarchaeology International, 3(1), 44–57.10.5744/bi.2019.1007Suche in Google Scholar

Larrea, J. J., & Viader, R. (2005). Aprisions et presuras au début du IXe siècle: Pour une étude des formes d’appropriation du territoire dans la Tarraconaise du haut Moyen Âge. In P. Sénac (Ed.), De la Tarraconaise à la Marche supérieure d’Al-Andalus (IVe-XIe siècle) (pp. 167–210). Toulouse: Université du Toulouse.10.4000/books.pumi.30696Suche in Google Scholar

Levi, G. (1994). Sobre microhistoria. In P. Burke (Ed.), Formas de hacer historia (pp. 119–143). Madrid: Alianza.Suche in Google Scholar

Levi, G. (2019). Microhistorias. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes.10.30778/2019.38Suche in Google Scholar

Loveluck, C. (2013). Northwest Europe in the early middle ages, c. AD 600-1150: A comparative archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139794725Suche in Google Scholar

Lucas, G. (2012). Understanding the Archaeological record. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511845772Suche in Google Scholar

Magnússon, S. G., & Szijártó, I. M. (2013). What is Microhistory? Theory and practice. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203500637Suche in Google Scholar

Marche, G. (2012). Why infrapolitics matters. Revue française d’études américaines, 131, 3–18.10.3917/rfea.131.0003Suche in Google Scholar

Merrifield, R. (1987). The archaeology of ritual and magic. London: Batsford.Suche in Google Scholar

Mímisson, K., & Magnússon, S. G. (2014). Singularizing the past: The history and archaeology of the small and ordinary. Journal of Social Archaeology, 14(2), 131–156.10.1177/1469605314527393Suche in Google Scholar

Monsalvo Antón, J. M. (2015). Antropología política e Historia: Costrumbre y derecho; comunidad y poder; aristocracia y parentesco; ritulaes locales y espacios simbólicos. In E. López Ojeda (Ed.), Nuevos temas, nuevas perspectivas en Historia Medieval (pp. 105–157). Logroño: Instituto de Estudios Riojanos.Suche in Google Scholar

Montanari, M. (1979). L’alimentazione contadina nell’alto Medioevo. Bari: Liguori.Suche in Google Scholar

Morales Muñiz, A. (2001). ¿De quién es este ciervo?: Algunas consideraciones en torno a la fauna cinegética de la España Medieval. In J. Clemente Ramos (Ed.), El medio natural en la España medieval: Actas del I Congreso sobre ecohistoria e historia medieval, [celebrado en Cáceres, entre el 29 de noviembre y el 1 de diciembre de 2000] (pp. 383–406). Cáceres: Universidad de Extremadura.Suche in Google Scholar

Morales Muñiz, A., & Morales Muñiz, D. C. (2001). ¿De quién es este ciervo? Algunas consideraciones en torno a la fauna cinegética de la España medieval. In J. Clemente Romos (Ed.), El medio natural en la España Medieval. (pp. 384–406). Cáceres: Universidad de Extremadura.Suche in Google Scholar

Moreland, J. (2001). Archaeology and text. London: Duckworth.Suche in Google Scholar

Moreland, J. (2010). Archaeology, theory and the Middle Ages: Understanding the Early Medieval past. London: Duckworth.10.5040/9781849668606Suche in Google Scholar

Oliva Herrer, H. R. (2002). Rituales de posesión en las comunidades campesinas castellanas a fines de la Edad Media. In C. M. Reglero de la Fuente (Ed.), Poder y sociedad en la Baja Edad Media hispánica: Estudios en homenaje al profesor Luis Vicente Díaz Martín (pp. 481–494). Valladolid: Universidad de Valladolid.Suche in Google Scholar

Orser, C. E. (2017). Historical archaeology. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315647128Suche in Google Scholar

Ouerfelli, M. (2013). Commerce et stockage des grains dans l’Occident musulman (XII e -XV e siècle). In M. Lauwers & L. Schneider (Eds.), Mises en réserve. Production, accumulation et redistribution des céréales dans l’Occident médiéval et moderne (pp. 217–297). Toulouse: Universitè du Toulouse.Suche in Google Scholar

Peterson, D. (2008). Cambios y precisiones de fecha de la documentación emilianense. Berceo, 154, 77–96.Suche in Google Scholar

Pluskowski, A. (2011). The ritual killing and burial of animals European perspectives. Oxford: Oxbow.10.2307/j.ctv13pk7ntSuche in Google Scholar

Puñal Fernández, T. (2002). Análisis documental de los rituales de posesión en la Baja Edad Media. Espacio, Tiempo y Forma. Serie III, Historia Medieval, 15, 113–148.10.5944/etfiii.15.2002.3676Suche in Google Scholar

Quirós Castillo, J. A. (Ed.). (2012). Arqueología del campesinado medieval: La Aldea de Zaballa. Bilbao: Universidad del Pais Vasco.Suche in Google Scholar

Quirós Castillo, J. A. (Ed.). (2019). Arqueología de una comunidad campesina medieval: Zornoztegi (Álava). Documentos de Arqueología Medieval. Bilbao: Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea.Suche in Google Scholar

Quirós Castillo, J. A., & Reynolds, A. (Eds.). (2023). Arqueología de las sociedades locales en la Alta Edad Media. San Julián de Aistra y las residencias de las élites rurales. Historical Archaeologies. Oxford: Archaeopress.10.2307/jj.3452816Suche in Google Scholar

Ribeiro, A. (2019). Microhistory and archaeology: Some comments and contributions. Papers from the Institute of Archaeology, 28(1), 1–26.10.14324/111.444.2041-9015.1123Suche in Google Scholar

Riva, C., & Grau Mira, I. (2022). Global archaeology and microhistorical analysis. Connecting scales in the 1st-milennium B.C. Mediterranean. Archaeological Dialogues, 29(1), 1–14.10.1017/S1380203822000101Suche in Google Scholar

Rodríguez de Lama, I. (1979). Colección diplomática medieval de La Rioja: (923-1225). Logroño: Instituto de Estudios Riojanos.Suche in Google Scholar

Rodríguez-Escalona, M. (2021). Gestos simbólicos y rituales juridicos de transferencia y posesión de bienes en la Cataluña altomedieval. Anuario de Estudios Medievales, 51(2), 801–822.10.3989/aem.2021.51.2.11Suche in Google Scholar

Roig Buxó, J. (2013). Silos, poblados e iglesias: Almacenaje y rentas en época visigoda y altomedieval en Cataluña (siglos VI al XI). In A. V. -E. Guirado & G. Bianchi (Eds.), Horrea, barns and silos: Storage and incomes in early medieval Europe (pp. 145–170). Bilbao: Universidad del País Vasco.Suche in Google Scholar

Ruiz Asencio, J. M., Ruiz Albi, I., & Herrero Jiménez, M. (2010). Los becerros gótico y galicano de Valpuesta. Madrid: Academia de la Lengua Española.Suche in Google Scholar

Salvadori, F. (2015). Uomini e animali nel Medioevo: Ricerche archeozoologiche in Italia, tra analisi di laboratorio e censimento dell edito. Saarbrücken: Edizioni Accademiche Italiane.Suche in Google Scholar

Sánchez Rincón, R. (2012). De monedas y avesa, una extraña pareja. Gaceta Numismática, 184, 57–65.Suche in Google Scholar

Sánchez Sánchez, X. (2019). Las formas del poder en la feudalidad tardía. Las tomas de posesión en el señorío de la iglesia de Santiago de Compostela durante el siglo XV: Dominio, gesto y significación. Studia Historica. Historia Medieval, 37(2), 133–153.10.14201/shhme2019372133153Suche in Google Scholar

Scott, J. C. (1976). The moral economy of the peasant: Rebellion and subsistence in Southeast Asia. New Haven, London: Yale University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Scott, J. C. (1985). Weapons of the weak. Everyday forms of peasant resistance. London: Yale University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Scott, J. C. (1990). Domination and the arts of resistance: Hidden transcripts. London: Yale University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Scott, J. C. (2013). Decoding subaltern politics. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 53(9), 1689–1699.Suche in Google Scholar

Sigaut, F. (1978). Les réserves de grains a long terme: Techniques de conservation et fonctions sociales dans l’histoire. Paris: Éditions de la Maison des Sciences de l’Homme.Suche in Google Scholar

Smietniansky, S. (2016). El uso motivado del lenguaje: Escritura y oralidad en los rituales de toma de posesión. El caso de Hispanoamérica colonial. Revista de Antropologia São Paulo, 59(2), 131–154.10.11606/2179-0892.ra.2016.124285Suche in Google Scholar

Smith, S. V. (2009). Materializing resistant identities among the medieval peasantry: An examination of dress accessories from English rural settlement sites. Journal of Material Culture, 14(3), 309–332.10.1177/1359183509106423Suche in Google Scholar

Steele, B. J. (2011). Revisiting classical functional theory: Towards a twenty-first century micro-politics. Journal of International Political Theory, 7(1), 16–39.10.3366/jipt.2011.0004Suche in Google Scholar

Sykes, N. (2015). Beastly questions: Animal answers to archaeological issues. London: Bloomsbury Academic, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.Suche in Google Scholar

Tambiah, S. J. (1985). Culture, thought, and social action. Harvard: Harvard University Press.10.4159/harvard.9780674433748Suche in Google Scholar

Tejerizo García, C., & Carvajal Castro, Á. (2021). Confronting Leviathan. Some remarks on resistance to the state in precapitalist societies: The case of Early Medieval Northern Iberia. In T. L. Thurston & M. Fernández-Gotz (Eds.), Power from below in premodern societies: The dynamics of political complexity in the archaeological record (pp. 202–219). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781009042826.010Suche in Google Scholar

Torre, A. (2011). Luoghi: La produzione di località in età moderna e contemporanea. Roma: Donzelli.Suche in Google Scholar

Vigil-Escalera Guirado, A. (2013). Ver el silo medio lleno o medio vacío: La estructura arqueológica en su contexto. In G. Bianchi (Ed.), Horrea, barns and silos: Storage and incomes in early medieval europe (pp. 127–144). Bilbao: Universidad del País Vasco.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Social Organization, Intersections, and Interactions in Bronze Age Sardinia. Reading Settlement Patterns in the Area of Sarrala with the Contribution of Applied Sciences

- Creating World Views: Work-Expenditure Calculations for Funnel Beaker Megalithic Graves and Flint Axe Head Depositions in Northern Germany

- Plant Use and Cereal Cultivation Inferred from Integrated Archaeobotanical Analysis of an Ottoman Age Moat Sequence (Szigetvár, Hungary)

- Salt Production in Central Italy and Social Network Analysis Centrality Measures: An Exploratory Approach

- Archaeometric Study of Iron Age Pottery Production in Central Sicily: A Case of Technological Conservatism

- Dehesilla Cave Rock Paintings (Cádiz, Spain): Analysis and Contextualisation within the Prehistoric Art of the Southern Iberian Peninsula

- Reconciling Contradictory Archaeological Survey Data: A Case Study from Central Crete, Greece

- Pottery from Motion – A Refined Approach to the Large-Scale Documentation of Pottery Using Structure from Motion

- On the Value of Informal Communication in Archaeological Data Work

- The Early Upper Palaeolithic in Cueva del Arco (Murcia, Spain) and Its Contextualisation in the Iberian Mediterranean

- The Capability Approach and Archaeological Interpretation of Transformations: On the Role of Philosophy for Archaeology

- Advanced Ancient Steelmaking Across the Arctic European Landscape

- Military and Ethnic Identity Through Pottery: A Study of Batavian Units in Dacia and Pannonia

- Stations of the Publicum Portorium Illyrici are a Strong Predictor of the Mithraic Presence in the Danubian Provinces: Geographical Analysis of the Distribution of the Roman Cult of Mithras

- Rapid Communications

- Recording, Sharing and Linking Micromorphological Data: A Two-Pillar Database System

- The BIAD Standards: Recommendations for Archaeological Data Publication and Insights From the Big Interdisciplinary Archaeological Database

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Plant Use and Cereal Cultivation Inferred from Integrated Archaeobotanical Analysis of an Ottoman Age Moat Sequence (Szigetvár, Hungary)”

- Special Issue on Microhistory and Archaeology, edited by Juan Antonio Quirós Castillo

- Editorial: Microhistory and Archaeology

- Contribution of the Microhistorical Approach to Landscape and Settlement Archaeology: Some French Examples

- Female Microhistorical Archaeology

- Microhistory, Conjectural Reasoning, and Prehistory: The Treasure of Aliseda (Spain)

- On Traces, Clues, and Fiction: Carlo Ginzburg and the Practice of Archaeology

- Urbanity, Decline, and Regeneration in Later Medieval England: Towards a Posthuman Household Microhistory

- Unveiling Local Power Through Microhistory: A Multidisciplinary Analysis of Early Modern Husbandry Practices in Casaio and Lardeira (Ourense, Spain)

- Microhistory, Archaeological Record, and the Subaltern Debris

- Two Sides of the Same Coin: Microhistory, Micropolitics, and Infrapolitics in Medieval Archaeology

- Special Issue on Can You See Me? Putting the 'Human' Back Into 'Human-Plant' Interaction

- Assessing the Role of Wooden Vessels, Basketry, and Pottery at the Early Neolithic Site of La Draga (Banyoles, Spain)

- Microwear and Plant Residue Analysis in a Multiproxy Approach from Stone Tools of the Middle Holocene of Patagonia (Argentina)

- Crafted Landscapes: The Uggurwala Tree (Ochroma pyramidale) as a Potential Cultural Keystone Species for Gunadule Communities

- Special Issue on Digital Religioscapes: Current Methodologies and Novelties in the Analysis of Sacr(aliz)ed Spaces, edited by Anaïs Lamesa, Asuman Lätzer-Lasar - Part I

- Rock-Cut Monuments at Macedonian Philippi – Taking Image Analysis to the Religioscape

- Seeing Sacred for Centuries: Digitally Modeling Greek Worshipers’ Visualscapes at the Argive Heraion Sanctuary

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Social Organization, Intersections, and Interactions in Bronze Age Sardinia. Reading Settlement Patterns in the Area of Sarrala with the Contribution of Applied Sciences

- Creating World Views: Work-Expenditure Calculations for Funnel Beaker Megalithic Graves and Flint Axe Head Depositions in Northern Germany

- Plant Use and Cereal Cultivation Inferred from Integrated Archaeobotanical Analysis of an Ottoman Age Moat Sequence (Szigetvár, Hungary)

- Salt Production in Central Italy and Social Network Analysis Centrality Measures: An Exploratory Approach

- Archaeometric Study of Iron Age Pottery Production in Central Sicily: A Case of Technological Conservatism

- Dehesilla Cave Rock Paintings (Cádiz, Spain): Analysis and Contextualisation within the Prehistoric Art of the Southern Iberian Peninsula

- Reconciling Contradictory Archaeological Survey Data: A Case Study from Central Crete, Greece

- Pottery from Motion – A Refined Approach to the Large-Scale Documentation of Pottery Using Structure from Motion

- On the Value of Informal Communication in Archaeological Data Work

- The Early Upper Palaeolithic in Cueva del Arco (Murcia, Spain) and Its Contextualisation in the Iberian Mediterranean

- The Capability Approach and Archaeological Interpretation of Transformations: On the Role of Philosophy for Archaeology

- Advanced Ancient Steelmaking Across the Arctic European Landscape

- Military and Ethnic Identity Through Pottery: A Study of Batavian Units in Dacia and Pannonia