The Early Upper Palaeolithic in Cueva del Arco (Murcia, Spain) and Its Contextualisation in the Iberian Mediterranean

-

Dídac Roman

Abstract

In this article, we present the results of the research carried out at the Gravettian occupation level of Cueva del Arco (Spain). For this purpose, a multidisciplinary investigation has been carried out in which all the elements recovered in the excavations carried out since 2015 at this site have been studied. The results are contextualised alongside all of the existing Gravettian sites in Mediterranean Iberia. The study of the material culture, the fauna, the landscape, and the dating has allowed us to approach the occupations of the site from many perspectives and has permitted us to conclude that Cueva del Arco was occupied sporadically at the beginning of the Gravettian period by a small human group in what would be the beginning of the consolidation of the anatomically modern humans (AMH) in this territory. Furthermore, these occupations were preceded by others belonging to the Aurignacian, which left hardly any remains in the cave. The data presented in this article lead us to believe that Cueva del Arco is a site of great importance for the knowledge of the beginning of the AMH settlement in the Iberian Mediterranean, both in its expansion towards the south and in its definitive consolidation in this territory.

1 Introduction

In this article, we present the data obtained from the excavations of the Gravettian occupation of Cueva del Arco. The site has been excavated since 2015, and an archaeological sequence has been documented beginning in the Middle Palaeolithic, followed by various levels of the Upper Palaeolithic and ending with early Neolithic occupation (Martín-Lerma & Román, 2018; Martín-Lerma et al., 2019, 2023).

Cueva del Arco is located in the municipality of Cieza (Murcia, Spain) at an altitude of 335–350 m asl and lies in a small ravine (Barranco de la Tabaquera) flowing into the river Segura, near Los Almadenes Canyon (Figure 1). It is a complex of various cavities around a large natural arch, which gives the name to the complex (translated into English as the “The Arched Cave”). These cavities have been individually labelled with letters, from A to E. Cave A is the focus of the current excavations and has provided the data for this study (Figure 2). Cave D has evidence of Palaeolithic art, as does Arco-II, a small cavity about 10 m away from the main arch (Salmerón Juan et al., 1997). In order to situate Cueva del Arco contextually, a brief overview of the periods which were documented at the site is essential.

Image of the Cueva del Arco and location map.

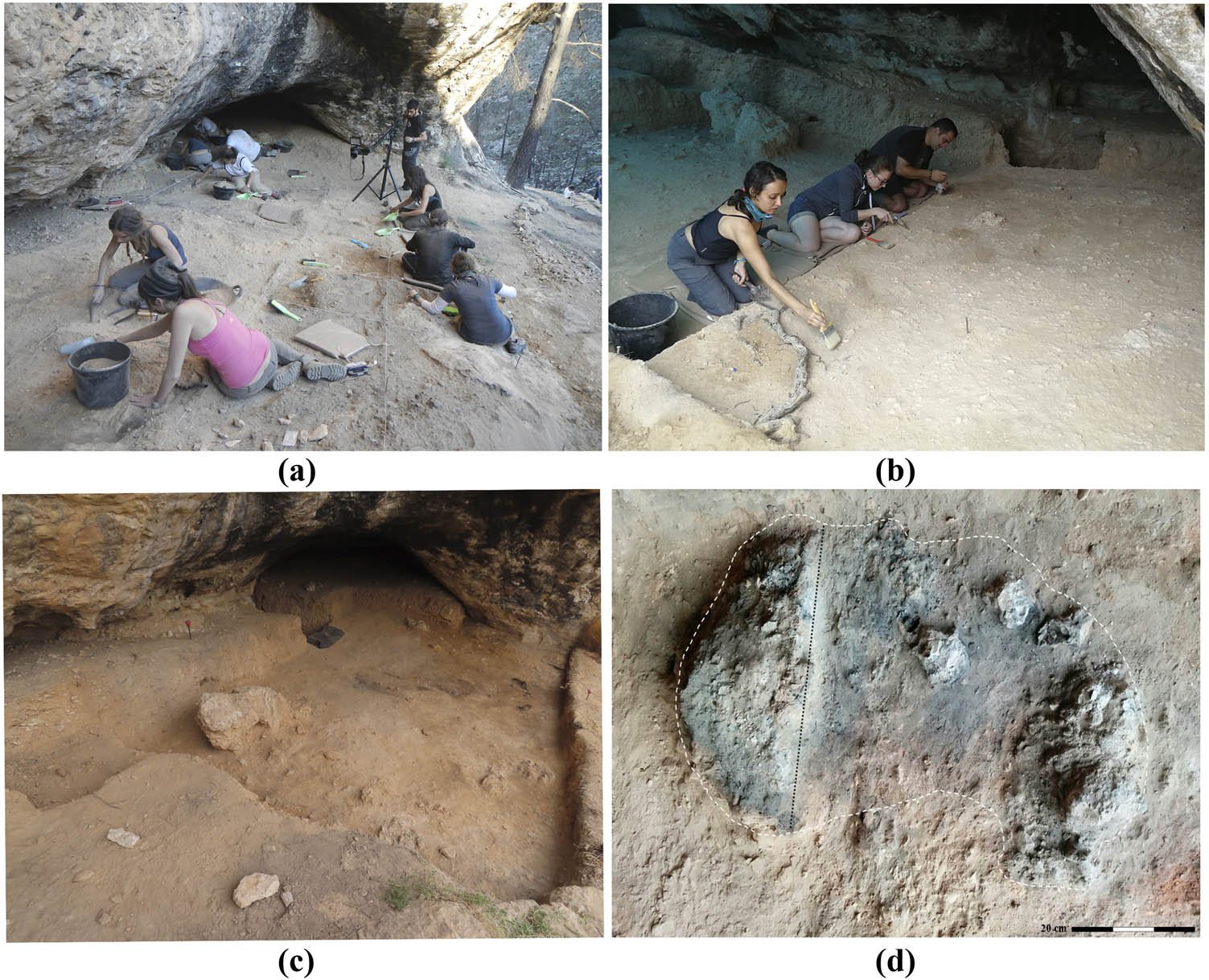

Images of the excavation in Cueva del Arco, cavity A. (a) Year 2015; (b) Year 2019; (c) Year 2019; (d) Hearth 1 (year 2015).

The beginning of the Upper Palaeolithic period (Aurignacian and Gravettian) is a heated topic in the Iberian Peninsula Palaeolithic research for many years. Like any time of transition, it has generated debates on various aspects, such as the disappearance of Neanderthals, the economy, the material culture, the landscape, and the chronological extent of the period (Cortés-Sánchez et al., 2019; Finlayson et al., 2006; Finlayson et al., 2008; Lloveras et al., 2016; Martínez-Alfaro et al., 2022; Martínez Varea, 2019; Molina Hernández, 2015; Morales et al., 2019; Real et al., 2019; Vidal Matutano, 2016; Villaverde et al., 2019; Zilhão & Pettitt, 2006; Zilhão et al., 2017; Zilhão, 2000, 2006).

The Iberian Mediterranean area, in particular, is precisely one of the most active regions for the study of the Gravettian period, especially due to the existence of a large number of sites that have provided important information on the beginning of the Upper Palaeolithic. These sites, many of them recently excavated, include Cova de les Malladetes (Villaverde et al., 2021), Cova de les Cendres (Villaverde & Román, 2004; Villaverde et al., 2019), El Palomar (De la Peña, 2012), and La Boja (Zilhão et al., 2017).

For all these reasons, the data provided by Cueva del Arco are of great interest. It makes it possible to significantly add to current knowledge, providing new information concerning material culture and its spatial distribution, the economy, and the landscape. These data are also supported by modern excavation methodology and radiocarbon dating that allow us to discuss the beginnings of the Gravettian period on the Mediterranean side of the Iberian Peninsula.

2 The Excavation

Cueva del Arco has been known archaeologically since the early 1990s after the discovery of two cavities with Palaeolithic rock art (Salmerón Juan et al., 1998) in Cave E and Arco II. In Cave E, two horse protomes, a doe, and some geometric lines can be attributed to the Solutrean period. At Arco II, there are three goats seen frontally and a possible vulva, stylistically assigned to the Upper Magdalenian period.

It was not until 2014 that some remains of the lithic industry, initially suspected and later confirmed to be from the Palaeolithic, were detected on the surface of Cave A. This led us to start the excavation project in 2015 (Martín-Lerma & Román, 2018) (Figure 2).

To date, eight campaigns have been carried out, allowing the extensive excavation of Caves A and D, and a 1 m2 test-pit in Cave E. The most complete and best-preserved archaeological deposit is the one found in Cave A. Within it, four archaeological units were excavated. These units are culturally attributed to the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic (Aurignacian, Gravettian, and Solutrean). On the top, material from the end of the Early Neolithic was recovered.

Cave D was documented Neolithic occupation, while the Palaeolithic remains that have been recovered to date (basically, lithic and faunal remains) do not allow clear assignment within the Upper Palaeolithic. In Cave E, the test-pit carried out thus far has not allowed us to document human occupations.

3 Methodology

The Gravettian levels we are presenting in this article have been excavated in an area of about 50 m² in Cave A. The surface has been divided into squares of 1 m², which, in turn, have been subdivided into four sub-squares measuring 50 cm on each side. The excavation was carried out using artificial spits 5 cm thick, always considering possible natural stratigraphic changes. The major changes in terms of textural and compositional features allowed us to define four “excavation units.”

All the sediment has been dry sifted through two 5 and 2 mm meshes, collecting all materials, including charcoal, micromammals, and small lithic remains. The characteristics of the sediment (which is rather fine and silty) have allowed this type of screening, although several sediment samples have been put aside for flotation and subsequent separation in the laboratory.

In order to study the spatial distribution of the materials (both horizontally and vertically), a three-dimensional plan was created in which each of the excavated layers and units were situated and distributed in a 3D document.

3.1 Mammal Remains

For the taxonomic and anatomical study of the macrofaunal remains, the reference bone collection from the Laboratorio Gil-Mascarell of the Department of Prehistory, Archaeology, and Ancient History of the University of Valencia was used. Indeterminate remains were classified first by weight according to the following categories: (i) very small <5 kg (e.g. Oryctolagus cuniculus, Felis silvestris), (ii) small between 5 and 100 kg (e.g. Capra pyrenaica), (iii) medium between 100 and 300 kg (Cervus elaphus), and (iv) large >300 kg, (Equus ferus, Bos primigenius) (Blasco, 2011), based on the mean weight of an adult from each of the present taxa. Second, they were classified by bone type, including (i) long bones (diaphysis of limb bones, including metapodial and phalanges), (ii) flat bones (cranial and axial skeleton, scapula, and coxal), and (iii) articular bones (carpal, tarsal, and epiphysis) (Cáceres, 2002).

Regarding the identification of age-at-death of ungulates, the classification was established based on dental eruption and wear and epiphysis fusion (Azorit, 2011; Barone, 1976; Mariezkurrena, 1983; Pérez Ripoll, 1988; Serrano et al., 2004; Silver, 1963). The individuals were classified into five categories: neonatal (deciduous teeth in eruption), infantile (complete deciduous teeth and permanent teeth germs), juvenile (deciduous teeth with different wear stages and some permanent teeth), adult (permanent teeth with different wear stages), and senile (permanent teeth with a heavy degree of wear) (Blasco, 2011). In the case of leporids, age-at-death was established based on epiphysis fusion following Sanchis (2012) and Cochard (2004), and the individuals were classified into three categories: juvenile (up to 3 months), subadult (3–9 months), and adults (>9 months).

The Number of Remains (NR), the Number of Identified Specimens (NISP), the Minimum Number of Elements (MNE), and the Minimum Number of Individuals (MNI) were used to calculate the general composition of the assemblage (Lyman, 1994, 2008). The standardised minimal animal units (% MAU) were also applied to the Capra pyrenaica remains (Binford, 1984). The percentage of Survivorship (% ISu) (Brain, 1981) and its correlation with the bone density of leporids (Pavao & Stahl, 1999) was applied by calculating Spearman’s rho, used to see if density differentiation can explain any bias in the assemblage. To evaluate the anatomical proportions and their relation to anthropic and non-anthropic accumulations, different indexes have been applied (Lloveras & Nadal, 2015): postcranial/cranial (PCRT/CR), appendicular/cranial (PCRAP/CR), long bones/cranial (PCRLB/CR), autopodia/zygopodia (AUT/ZE), zygopodia/stylopodia (Z/E), proximal/distal (P/D), and anterior/posterior (AN/PO).

Regarding the taphonomic analysis, all bones were seen under a stereomicroscope (Nikon SMZ-10A) to identify fractures and modifications. The classification of fractures followed Villa and Mahieu’s (1991) distinction between fresh and dry, depending on the morphology of fracture planes. To describe specific morphotypes, the Real et al. (2022) classification was used. The codes from this work are a combination of the origin of the fracture (fresh/dry/mixed) and the anatomical parts of the bone that are conserved including, for example, the length of the diaphysis, the width of circumference, or the quantity of the epiphysis.

To establish the origin of the accumulations, diagnostic modifications of non-human predators and humans were documented. Non-anthropogenic modifications were classified as tooth marks (scores, punctures, pits, and furrowing), fracture marks (notches, bone loss, and crenulated edges), and digestions, following classic criteria (Andrews, 1990; Binford, 1981; Domínguez-Rodrigo & Piqueras, 2003; Sala et al., 2012; Yravedra, 2006). Percussion marks (Vettese et al., 2020), cut-marks (Binford, 1981; Pérez Ripoll, 1992; Shipman & Rose, 1983; Soulier & Costamagno, 2017), and burnt bones (Stiner et al., 1995; Théry-Parisot et al., 2004) were registered as anthropogenic modifications. Specific references were considered for the modifications on leporid bones (Cochard et al., 2012; Hockett & Haws 2002; Lloveras & Nadal, 2015; Lloveras et al., 2009, 2011; Pérez Ripoll, 1993, 2004, 2005; Rosado-Méndez et al., 2016; Sanchis et al., 2011), as Leporidae are the best-represented family. Type of modification, agent, origin (percussion, cut-marks, tooth marks, and digestion), location, shape, distribution, direction, intensity, and quantity are the characteristics recorded for each modification.

3.2 Avifaunal Remains

The avifauna remains have been analysed from an archaeozoological perspective, with anatomical and taxonomic identification, as well as taphonomically, considering variables such as fragmentation, biotic and abiotic alterations, and possible marks of human origin. For the anatomical and taxonomic determination, reference collections have been used and diagnostic, metric, and morphological characters from the literature have been checked. For an initial approach to the remains in terms of orders and families, the work of Cohen and Serjeantson (1996) has been used. To identify passerines, especially small passerines, attempts have been made to apply the criteria proposed by Moreno (1985, 1986, 1987). Specifically in the case of corvids, the proposals of Tomek and Bocheński (2000) have been used. In the case of columbiforms, the criteria of Tomek and Bocheński (2009) have been applied. For the taphonomic marks and specifically the degrees of digestion, the work of Lloveras et al. (2014) has been used.

3.3 Plant Remains

During the excavation process, some charcoal fragments were taken manually, mainly from concentrations. The rest of the sediment was dry-sieved, and sediment samples were systematically collected to be processed using the tank flotation system, which allows for the recovery of very small organic remains. Once washed and dried, the samples were processed for the selection of the archaeobotanical material under a binocular loupe between 3 and 60 magnifications.

Charcoal analysis is based on the botanical identification of carbonised wood, i.e. determining which species the charcoal is derived from. For the standard analysis, charcoal is broken up manually, and no chemical treatment is needed, so these samples can be used later for radiocarbon dating (Vernet et al., 1979). Each fragment is observed under a reflected light brightfield/darkfield optical microscope with different lenses ranging from 50× to 1,000× magnification. Wood anatomical features are compared with specialised literature on plant anatomy (e.g. Greguss 1955, 1959; Jacquiot et al., 1973; Jacquiot, 1955; Schweingruber, 1990) as well as to a reference collection of current charred wood. For the observation of specific features and for taking pictures, we used a Hitachi S-4800 scanning electron microscope (SEM) held at the Central Service for Experimental Research Support (SCSIE) at the University of Valencia.

Charcoal analysis is on-going, however, to date, nine samples from Level II (including charcoal scattered throughout the level and hearth1) have been analysed with a total of 410 charcoal fragments.

Carpological analysis includes the study of not only seeds and fruits, but also stems, rhizomes, and tubers. For the taxonomical identification, carpological remains were observed under a low-power microscope and compared with specialised literature (Sabato & Peña-Chocarro, 2021; Torroba Balmori et al., 2013). In addition, a reference collection of current seeds and fruits was used. The histological identification was carried out after the observation of the remains under a reflected light brightfield/darkfield optical microscope.

To date, both hand-picked remains and those recovered during dry sieving have been identified. A total of 43 remains from three spits from Level II have been identified, but the carpological analysis is still ongoing.

The combination of anthracological and carpological analysis provides paleoclimatic and paleoeconomic information. Based on the ecological requirements of identified taxa, past climatic conditions and landscapes are reconstructed. The use of plant resources – firewood, food, and raw material – could be deeply assessed with the analysis of charred wood and seed remains.

For the palynological analysis of five coprolites, after the samples were weighed (Arc-Cop1: 2.02 g; Arc-Cop2: 10.74 g; Arc-Cop3: 0.84; Arc-Cop4: 3.83 g; Arc-Cop5: 0.41 g; Table 9), the “Classic Chemical Method” was followed for the extraction of palynomorphs (Dimbledy, 1985; Erdtman, 1969), with the modifications proposed by Girard and Renault-Miskovsky (1969) also taken into consideration. In order to evaluate the quality of the laboratory processing, we added one tablet of Lycopodium spores (BATCH No. 710961.500) to each coprolite sample. After being treated at the laboratory, the samples were mounted on slides with the use of liquid paraffin. The palynological identification was made by conventional microscopy (400× and 1,000×) using an optical microscope. We also used the palynomorph reference collection of the Department of Environmental Biology (Sapienza University of Rome) and of the Department of Plant Biology (University of Murcia). The pollen count data were treated with the Tilia Graph 1.7.16 program in order to obtain the pollen diagrams.

3.4 Stone Tools

The methodology for the use-wear analysis consisted of gentle cleaning of the tools in an ultrasonic tank with deionised water and neutral pH detergent (Twen-20), always observing beforehand for the possible presence of stuck-on residues. An Olympus BHMJ model microscope with Nomarski-type interferential contrast – DIC – and connection to a digital camera were used for traceological study (Martín-Lerma, 2015).

For the study of retouched tools, the typology of Sonneville-Bordes and Perrot (1954, 1955, 1956) has been used, and the studies of the French school for technology (e.g. Inizan et al., 1995; Pelegrin, 1995, 2000; Tixier et al., 1980) have been followed.

4 Stratigraphy

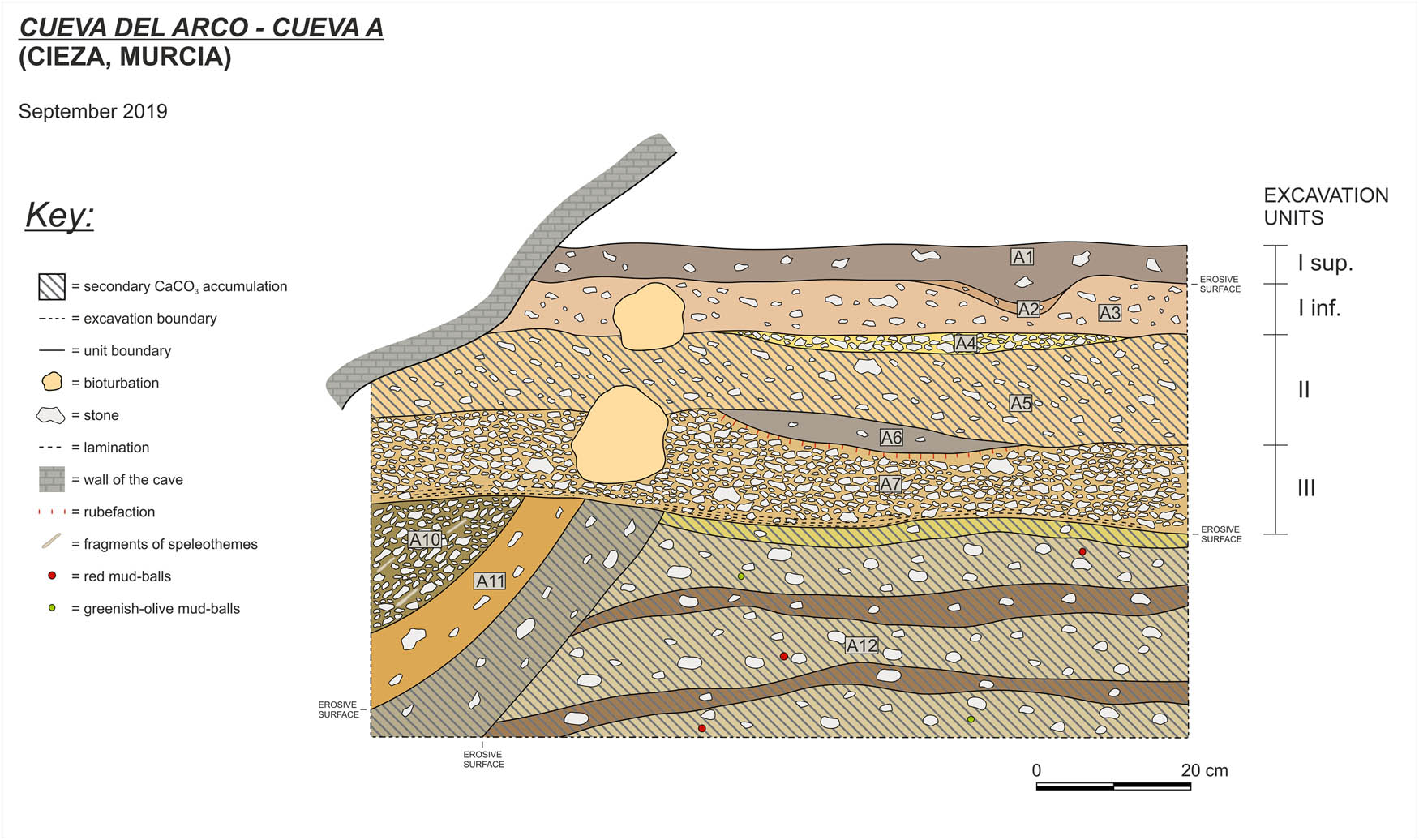

The deposit of Cave A is composed of several geoarchaeological field units (GFU) that were grouped, during archaeological fieldwork, into three main archaeological units (I, II, and III – see Martín-Lerma et al., 2023 for details) (Figure 3). All the units throughout the deposit contain common to abundant stones. They are composed of angular and sub-angular fragments of local limestone, ranging from a few millimetres to several centimetres in size.

Cueva del Arco: stratigraphic section of Cave A. The labels correspond to the GFU (Martín-Lerma et al., 2023); archaeological units are reported to the right.

Archaeological unit I sup. correspond to the Holocene series and consists of dark sediments, rich in organic matter and combustion by-products, with few stones. The lower boundary of archaeological unit I sup. is sharp and well recognisable but slightly irregular due to ancient biological activity.

Archaeological units I inf. and II represent the upper part of the Pleistocene series and include three main layers. The set of layers is almost horizontal in the inner sector of the shelter and slightly dips outwards (by very few degrees) approaching the dripline. All the layers are made up of sediment with a dominant clastic coarse fraction (limestone fragments) and fine material, the colour of which ranges from yellowish to brownish hues. The units were distinguished among them according to the relative quantity of coarse clastic inputs and the characteristics of the fine material (grain size, colour, and presence of secondary calcium carbonate). The base of archaeological unit I is a thin layer of silt with fine sand, 7.5YR5/6, and common stones, sometimes with horizontal orientation pattern (GFU A3). Below this, there is an intercalation of clast-supported limestone breccia with common angular platy stones (some of them are clearly frost-slabs), with a well-visible horizontal orientation pattern and scarce fine material, 7.5YR5/6 (GFU A4). The thickest unit is GFU A5, which shows the same features as GFU A3 but features slightly larger stones and weak cementation by calcium carbonate, which is also sometimes found in the form of small nodules. This layer lies on a concave lens enriched with ash and charcoal fragments, which stratigraphically corresponds to the top of archaeological unit III (A6 in Figure 3).

The succession of Cave A broadly shows the typical characteristics of southern European rock-shelter infillings formed in Mediterranean environmental contexts (Angelucci et al., 2018), that is crude stratification, predominance of coarse angular fraction with variable quantity of fine material and poor textural sorting, local enrichment of secondary calcium carbonate, and slight disturbance by ancient biological activity. The limestone fragments that make up the bulk of the sedimentary deposit are of local origin and clearly come from the rock shelter’s roof and wall. Among the limestone fragments, frost slabs are detected; they may indicate frost action (among other processes of wall disintegration) within a cold, moist climate context. As a whole, the succession of Cave A is rather thin, indicating a low sedimentation rate during its accumulation; this can be related to the position within the cave (i.e. sedimentary inputs in this position were scarce and mostly coming from cave walls).

5 Radiocarbon Dates

5.1 Sample Selection for Radiocarbon Dating

At Cueva del Arco, the selection of botanical material for dating has followed a strict protocol that first implies botanical identification. Dating is a destructive method, and if the sample is not first identified, valuable information about the history of the plants and their distribution is lost. In addition, the correct selection of the species to be dated can help solve taphonomic issues (Carrión Marco et al., 2018). Given the taxonomic poverty at Cueva del Arco and the predominance of long-lived species, the application of dendrological observations has been essential, such as the presence of bark or the last growth rings of the plant (which would give the closest date to the wood-cutting). Another criterion has been the selection of short-lived organs of long-lived species, as in the case of the pinecone bract, which is a reproductive leaf of the cone or strobilus, which offers greater precision than wood of the same species.

5.2 Results

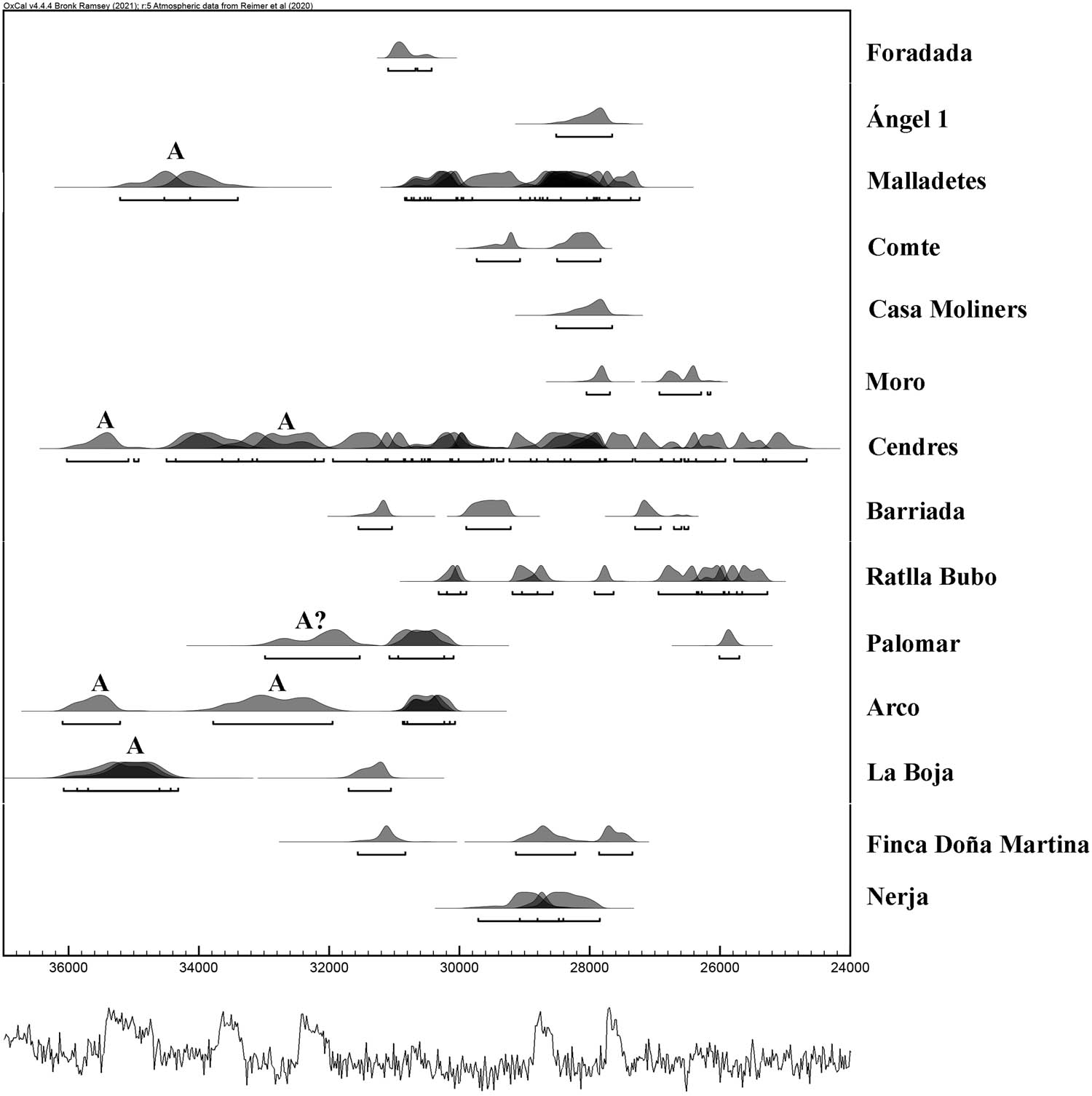

For Unit II of Cave A, four radiocarbon dates were obtained on Juniperus sp. charcoal (Table 1, Figure 12) and another date from Unit III that can be derived from level II. Three dates, from two of the hearths, are very close to one another, possibly showing an occupation event in the cavity in the early Gravettian period. For these three, the maximum and minimum probable dates are between 30890 and 29930 cal BP.

Radiocarbon dates from Cueva del Arco, Cave A, were obtained at the laboratories of ETH (Zurich, Switzerland), VERA (Vienna, Austria) and BETA Analytics (Miami, USA)

| Unit | Ref. | Sample | BP | δ 13C | Cal BP (95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| II | ETH-67833 | Juniperus sp. | 26193 ± 104 | −20.5 ± 1 | 30801–30148 |

| II | ETH-67834 | Juniperus sp. | 26279 ± 106 | −21 ± 1 | 30870–30233 |

| II | VERA-7068 | Juniperus sp. | 26151 ± 172 | −21.4 ± 1.4 | 30846–30068 |

| II | VERA-7063 | Juniperus sp. | 28617 ± 287 | −27.8 ± 1.1 | 33780–31948 |

| III | Beta - 627630 | Celtis seed | 31190 ± 190 | −6.5 | 36091–35203 |

ETH and VERA samples were pretreated using the ABOx-SC (acid-base-oxidation-stepped combustion) method (Brock and Higham, 2009). The results were calibrated with OxCal (version 4.4).

The other two dates are a little earlier, 33580–31620 and 36091–35203 cal BP and, as we will see in the final discussion, open up the possibility of the existence of some occupation from the end of the Aurignacian.

6 Lithic Industry

6.1 Technology

Evidence for the lithic industry found in levels I sup/inf. and II of Cavity A of Cueva del Arco is provided by 873 pieces. From I sup., we have removed the shapeless pieces, debris, splinters, and edges, as we do not know for certain whether they belong to the Gravettian period, nor do they provide any technological information. Of the total remains, 721 pieces are made of flint, making up the vast majority. The rest are made of quartzite (102 pieces), limestone (29), siliceous limestone (18), quartz (1), jasper (1), and sandstone (1). Regarding level II, we have a total of 389 pieces (Table 2). Of the materials found, the small number of cores (22 cores and fragments) is striking. Most of them (19) appear in the I sup/inf. level, which gives us minimal information about the blank extraction processes, as we cannot completely rule out these pieces belonging to occupations after the Gravettian period. Of the three pieces that appear in level II, one corresponds to a very depleted core fragment. The second is a complete core, with an orthogonal pattern and extraction of bladelets and possibly blades, as shown by the last 8.6 mm laminar extraction. The third core is shapeless, with extractions in three different directions. We have managed to preserve the reassembly of one of the last extractions – a laminar flake measuring 23.3 mm × 13.3 mm × 3.2 mm. The other cores, which we study here because we consider that, given the limited material corresponding to times later than the Gravettian, they must belong to this period, vary a little in type. We have examples of the frontal unipolar type for the extraction of blades and bladelets (5) with a quadrangular and pyramidal shape, and ecaillée frontal bipolar (1) for the extraction of bladelets and flakes.

Number of lithic blanks from level II

| Level II | Quarzite | Chert | Siliceous limestone | TOTAL | Retouched |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flake | 24 | 106 | 5 | 135 | 16 |

| Laminar Flake | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 1 |

| Blade | 0 | 27 | 3 | 30 | 9 |

| Bladelet | 1 | 27 | 4 | 32 | 13 |

| Thermal Flake | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Core | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Trimming (CTE) | 1 | 12 | 1 | 14 | 3 |

| Debris | 21 | 135 | 9 | 164 | 1 |

| Burin Spall | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| TOTAL | 47 | 321 | 22 | 389 | 43 |

All the cores and fragments are used up as much as possible and are very small, because the maximum possible amount of raw material has been used. There is also not enough cortex remains in the pieces to distinguish whether these cores come from raw material nodules or plaquettes, although we believe that in the case of quartzite (4) they are nodules, due to their natural shape in the area. This is also due to the large number of core trimming elements (CTE) that we found in the deposit.

One of the features of these pieces, beyond their high level of fractures, is the intense preparation of the overhangs and the percussion planes. This is one more indication that as much of the raw material as possible has been used. We have pieces showing small flakes all along the entire edge of the percussion plane, especially on overhangs, semi-tablets, and tables, as well as indications in the tables demonstrating the knapping errors typical of the use of a core at the end of its life.

With regard to the blanks, we can appreciate a clear overall tendency towards blade extraction, despite the fact that the majority of blanks are flakes (335). This is because these are not generally the final objective of the preparation but rather the remains of knapping and preparation. A factor determining this conclusion is that most of the retouched tools are made from blades and that most of the flakes are fractured and very small in size: 20.54 mm × 18.7 mm × 4.75 mm on average.

Flake extraction is carried out through surface preparation of the butts, which are mostly smooth. In the pieces where we have been able to distinguish it thanks to technological marks, percussion is generally with a hard hammer (163). This places us in the initial moments of the knapping process.

Although there are fewer of them (232), blade blanks are the end products of the blank extraction process. They are also considerably fractured, but they provide us with a great deal of information about the technology used. Concerning the types of blank, we have a larger number of bladelets, although the difference is minimal. If we relate this to the cores found, we can extrapolate that, at first, they were perhaps used for blade extraction, and then, when they became smaller, bladelets were extracted. We have no cores that are clearly for blade extraction to provide us with full knowledge of this aspect, which is not clarified by the CTE. We must also consider the possibility that these blanks are brought in already knapped from other places. Regarding the section of these blanks, 61.5% have a triangular section, so the extraction of these blades could be via frontal patterns using working fronts.

The vast majority of blade negatives on the various blanks are unipolar (150), as opposed to bipolar ones (17), which confirms us the use of this type of reduction pattern (frontal unipolar cores).

Finally, in this regard, we have pieces with well-prepared butt, which could indicate that they are blanks showing fully exploited cores. Above all, abrasions predominate and the variety of butts increases with respect to flakes, as linear and punctiform butts appear, although the majority continue to be smooth (68), followed, a long way behind, by dihedral (12), with the use of a soft hammer notably increasing (more than 50% of the total that we have been able to determine).

The data obtained after the study of Gravettian technological processes at Cueva del Arco have parallels in other sites in the Mediterranean area and inland in the southeast of the Iberian Peninsula. We found similarities in the characteristics of the initial reduction processes with the items analysed at Cueva de Nerja (Málaga), where there are low numbers of cortical pieces and very few cores – a problem similar to the one we found. Flakes also predominate, with blade blanks selected to make retouched tools (Jordá Pardo et al., 2008). This last characteristic is a general feature in the Gravettian period in the Mediterranean area, as we also find it in sites such as Cova de les Cendres (Alacant), where the finds are focused on blade exploitation, with many laminar flakes, even though flakes form a majority of the unworked blanks. Like this set, there are also cores from which blades and bladelets are extracted as work progresses and their size is reduced (Villaverde et al., 2019).

In terms of knapping patterns, Cueva del Arco complex coincides with others such as Les Cendres, Cova de les Mallaetes (València), and Abrigo del Palomar (Albacete), where we also find mostly unipolar prismatic cores, although bipolar knapping is by no means exceptional. For example, at Palomar, bipolar knapping has been interpreted as a way of recycling unworked supports and flint fragments, extracting bladelets from them with little technical difficulty (De la Peña & Vega Toscano, 2013). We should also stress that at Cueva del Arco we did not find blades extracted from cores in the form of carinated end-scrapers. Nor do these appear at Abrigo de La Boja (Zilhão et al., 2010), although they are abundant at the Palomar and Mallaetes (De la Peña & Vega Toscano, 2013).

The maintenance of the cores as they are being worked on also shows similarities, again with the Palomar complex, where the CTE are mainly semi-tablets and blade tables to correct the percussion plane and eliminate preparation and extraction knapping errors. Meanwhile, in the Valencian area, extraction on the flanks of the core to clean the extraction surface from the sides is predominant, as the cores are shorter (Villaverde et al., 2019). Finally, we found these cores to have been used up as far as possible after the extraction of bladelets (Zilhão et al., 2010).

6.2 Stone Tool Typology

A total of 43 retouched pieces have been found at the Gravettian level II, including four pieces from level I inf. which are clearly Gravettian (Table 3), representing 11% of the material recovered and 20% of production blanks. If we consider the excavated area, we can see we are dealing with a low density of lithic materials. Among these pieces, we would like to highlight the presence of six scrapers which, due to their characteristics, and having studied the materials from the Middle Palaeolithic level, we would prefer to include there. These are pieces that appeared in the intersection between levels II and III and which we believe belong to the lower level.

Retouched types from Level I inf. and II following Sonneville-Bordes and Perrot (1954, 1955, 1956) table numbers

| List no. | TYPE | No. | Group | No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Simple end scraper | 1 | G | 2 |

| 8b | Ogival end scraper | 1 | ||

| 30a | Angled burin on a break | 2 | B | 2 |

| 48 | Gravette point | 3 | D | 13 |

| 51 | Microgravette | 10 | ||

| 60 | Straight truncated piece | 1 | T | 1 |

| 65 | Retouch on 1 edge | 3 | RP | 4 |

| 66 | Retouch on 2 edges | 1 | ||

| 75 | Denticulated | 2 | ND | 2 |

| 85a | Backed bladelet | 1 | ml | 4 |

| 85d | Fine retouched bladelet | 1 | ||

| 85e | Pointed bladelet | 1 | ||

| 91c | Truncated backed point | 1 | ||

| 92 | Varia | 9 | V | 9 |

| TOTAL | 37 | 37 | ||

| 77 | Sidescraper | 6 | SS | 6 |

To distinguish the gravettes from microgravettes, we have considered their width, taking 8 mm as the measurement to separate them. This measurement is based on studies carried out in recent years in the Iberian Mediterranean area for Gravettian projectiles (Román & Villaverde, 2006; Villaverde et al., 2019) that combine the characteristics of the pieces from this area with various approaches made in other areas (e.g. Soriano, 1998).

The analysis of the materials, taking into account that, due to their low number, the data are merely indicative, shows us we are dealing with an occupation in which backed pieces predominate (40%), with microgravettes (27%) clearly ahead of Gravette points (8.1%). The other types are similarly represented at between 2 and 5%. The miscellaneous group is abundant, although most are fragments of unclassifiable retouched pieces (Figure 4).

Stone Tools. Gravette points (1–3); blades (4–5); backed bladelets/points (6, 8–11); double backed point (7); Dufour bladelet (12); burins (13, 16); end-scrapers (14–15).

The low number of pieces and the fragmentation of most of them do not permit a detailed analysis of the dimensions, but we can point out that the largest piece is a Gravette point measuring 69 mm in length by 13 mm in width, while the only complete microgravette measures 29 mm × 4 mm, although there is a piece that is still 43 mm in length even with a distal fracture. This shows us some of these pieces can be almost as long as the gravettes. If we analyse the width and thickness of all the pieces, we can see that the site we have here could show the largest projectiles of all the Gravettian sites in the Iberian Mediterranean (Román & Villaverde, 2006).

On the other hand, the presence of a finely retouched pointed bladelet is worth noting and also, although it appeared in the test pit and is not included in this study, a double-backed microblade tip. These are pieces found at recently excavated Gravettian sites with classification systems like the one we have applied in this study (Villaverde et al., 2019) that accompany gravettes and microgravettes.

The presence of end scrapers and burins is the same (two pieces). One of the end scrapers is quite large, and despite a proximal fracture (and the frontal reduction itself), it is 58 mm long. The other piece is a distal end (front) with an ogival tendency. The two burins are angled on fractures and are of a good size (the entire 58 mm in length). It should be noted that one of them appeared in the centre of one of the combustion structures.

A small bladelet with fine direct retouches which appeared just below one of the hearths dated to the early Gravettian period deserves a special mention. Although its type could be related to the Gravettian, the fact that it is not a backed piece and the existence of two dates of 33580–31620 and 36091–35203 cal BP makes us consider that it is a piece linked to a Evolved Aurignacian occupation that we have not detected in the excavation because it consisted of very sporadic occupation of the cavity.

This is a question that the data we currently possess does not allow us to confirm. However, because of the chronological and cultural context of the Aurignacian period in our area of study, it can be left open.

6.3 Use-wear Analysis

The use-wear analysis remains at an initial phase, but in this study, we are able to offer some of the early results we are obtaining. The randomly selected sample includes 12 pieces: four pieces with no retouching (flake/blade) and two of each type (end scraper/burin/Gravette/microgravette).

Regarding the microscopic alterations detected, we found three pieces (208, 734 and 735) with the so-called “floor shine” produced by rolling in sediment. This alteration, although it has not made the study impossible, has particularly affected the finer-grained flint and is especially present in the higher areas of the topography. However, most of the pieces analysed show no evidence of shine, so there have been no difficulties with the microscopic analysis.

In a functional study, we cannot focus solely on the retouched material, as the unretouched blanks also show signs of use. In fact, the two selected flakes (610 and 639) have been used to work wood, as they have a polish with a gently curving texture typical of this type of material, which extends to areas of medium topography. The light it reflects is bright, and some characteristic accidents can be perceived, such as undulations following the direction of use, and microholes.

One of the blades has no traces of use (208) and the other (634) shows a compact polish evenly distributed over high points of the topography and also in adjacent depressed areas. It is shiny with a curved tendency typical of something used to work a hard material, like bone or antler. We also found small, unevenly distributed chips, predominantly semicircular in shape, associated with sharpening.

Both domestic tools and projectiles have been selected from the retouched pieces. The two end scrapers – one on a flake (734), and one end scraper front (428) – have been used for leather work. The polish looks rough and greasy, as is very characteristic of this type of activity. The second piece is seen to have been used more, due to intense, continuous work, which allows us to confirm that it is the product of reworking, even preserving grooves that mark the oblique direction of the scraping.

Regarding the burins, one of the selected pieces is a burin on break (735) directly related to working bone material. It has a shiny, compact polish that is evenly distributed, with a clear scaly tendency. The other piece analysed (202) shows only percussion grooves and no signs of use, which has allowed us to interpret it as a core for extracting blanks rather than a tool.

Finally, we focus on analysing projectile items. The two selected microgravettes (983 and 741) show similarities in the traces found, as, although they show neither polishing nor impact macrofractures, they do retain impact striations and microchips on the edge caused by having been thrown at and striking, a harder object, probably an animal carcass.

The study of the gravettes (943 and 981) reveals a different use, as they lack the grooves and breaks derived from the impact. Instead, they show polishing developed with grooves related to continuous transversal activities. We cannot, therefore, rule out the possibility that these pieces may have been used as parts of small knives for various uses. This hypothesis is strengthened by their considerable size, unlike the microgravettes previously analysed.

Thanks to the analysis of the set of pieces, the functional potential of the Gravettian lithic material from Cueva del Arco is abundantly clear (Figure 5). The traceological studies in progress will undoubtedly help us to understand the type of activities carried out in the cave during its different phases of occupation, as has been done at other sites in the Region of Murcia (Zilhão et al., 2017).

Results obtained from the use-wear analysis. Scraper (1); burin (2); microgravette (3–4); gravettes (5–6).

7 Fauna

7.1 Macrofauna

7.1.1 Taxonomic and Anatomical Composition

The Gravettian macrofaunal assemblage is composed of 1,038 remains: 525 (50.3%) determinate and 522 (49.7%) indeterminate (Table 4), and seven coprolites. Several ungulates, one carnivore species, and leporids were identified.

Taxonomic composition by NISP, % NISP, and MNI of Level II

| NISP | % NISP | % NISP det | MNI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infantile | Juvenile | Subadult | Adult | ||||

| DETERMINATE | 516 | 49.7 | |||||

| Perissodactyla | 4 | 0.4 | 0.8 | ||||

| Equus ferus | 4 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 1 | |||

| Artiodactyla | 36 | 3.5 | 7.0 | ||||

| Bos primigenius | 1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 1 | |||

| Capra pyrenaica | 32 | 3.1 | 6.2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Cervus elaphus | 3 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1 | |||

| Carnivora | 3 | 0.3 | 0.6 | ||||

| Felis silvestris | 3 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1 | |||

| Lagomorpha | 473 | 45.6 | 91.7 | 1 | 5 | 10 | |

| INDETERMINATE | 522 | 50.3 | |||||

| Very small size | 7 | 0.7 | |||||

| Small size | 5 | 0.5 | |||||

| Small–medium size | 177 | 16.9 | |||||

| Medium size | 9 | 0.9 | |||||

| Medium–large size | 3 | 0.3 | |||||

| Large size | 5 | 0.5 | |||||

| Indeterminate | 316 | 30.2 | |||||

| 1,038 | 2 | 5 | 15 | ||||

Subadult age is referred only to Leporidae (shown in Section 3).

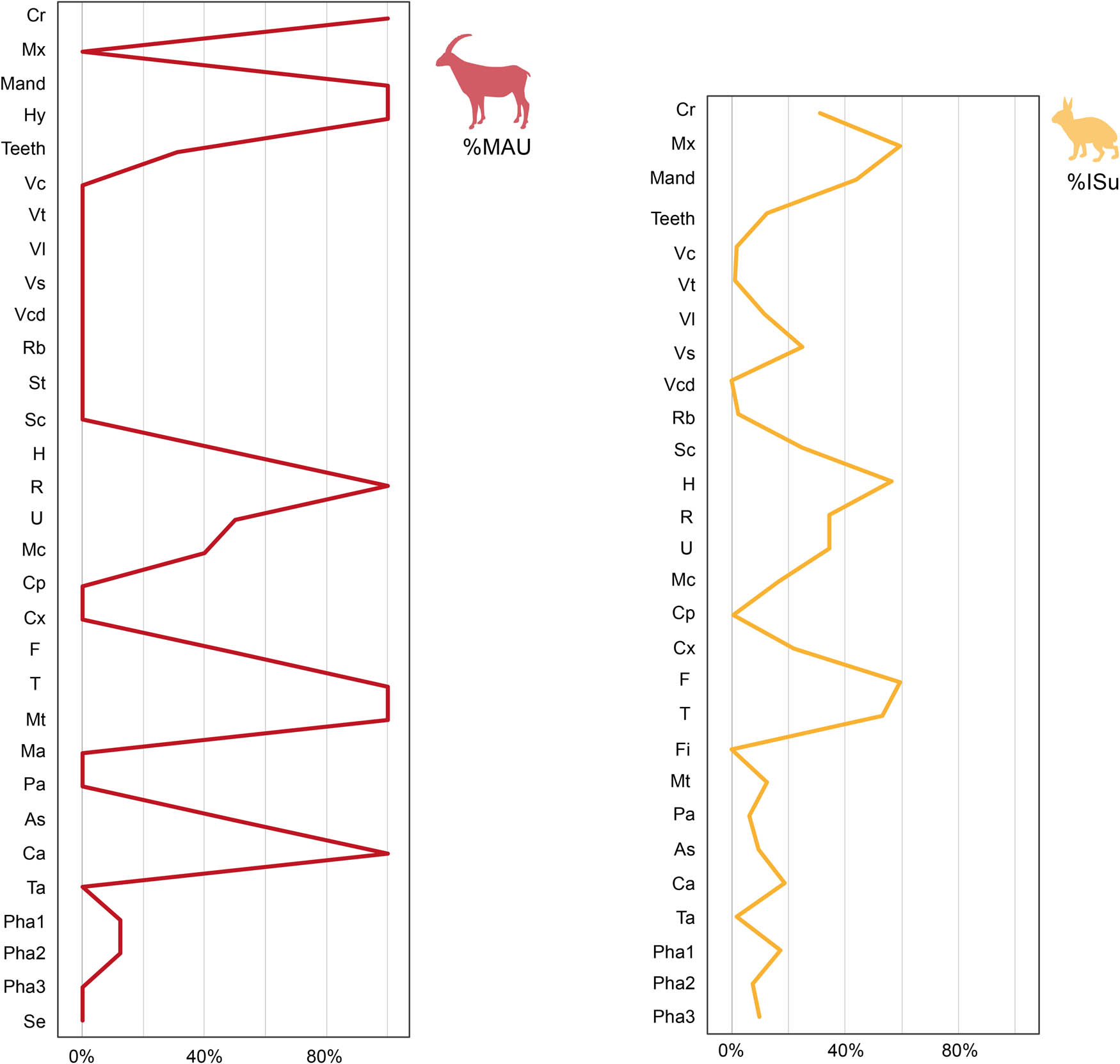

Leporids are the best-represented group in terms of NISP (91.7% of the determinates). Most of the anatomical elements of leporids are present in the assemblage (Table 5, Figure 6). Maxilla, femur, humerus, and tibia are the best-represented elements (>50%), but also mandible, cranium, radius, and ulna show high values between 30 and 40% (% ISu). Scapula, coxal, and sacrum are represented around 20%. Axial elements, carpal, tarsal, and phalanges, however, have low percentages (<20%). There is no correlation between % ISu and bones density (rs = 0.4348; p = 0.0276). Thus, it is unlikely that diagenetic processes biased the assemblage.

Anatomical composition of the species by NISP and MNE

| Equus ferus | Bos primigenius | Capra pyrenaica | Cervus elaphus | Felis silvestris | Leporidae | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NISP = MNE | NISP = MNE | NISP | MNE | NISP = MNE | NISP = MNE | NISP | MNE | |

| Cranial | 1 | 1 | 14 | 14 | 2 | 125 | 89 | |

| Cr | 1 | 1 | 19 | 5 | ||||

| Mx | 25 | 19 | ||||||

| Mand | 2 | 2 | 1 | 30 | 14 | |||

| Hy | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Teeth | 1 | 1 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 51 | 51 | |

| Axial | 30 | 30 | ||||||

| Vc | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Vt | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Vl | 13 | 13 | ||||||

| Vs | 4 | 4 | ||||||

| Rb | 9 | 9 | ||||||

| Forelimb | 6 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 81 | 70 | ||

| Sc | 11 | 8 | ||||||

| H | 1 | 1 | 1 | 20 | 18 | |||

| R | 2 | 2 | 1 | 15 | 11 | |||

| U | 1 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 11 | |||

| Cp | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| Mc | 2 | 2 | 21 | 21 | ||||

| Hindlimb | 2 | 9 | 8 | 109 | 73 | |||

| Cx | 1 | 11 | 7 | |||||

| F | 1 | 1 | 43 | 19 | ||||

| T | 1 | 2 | 2 | 25 | 17 | |||

| Pa | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| As | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| Ca | 2 | 2 | 6 | 6 | ||||

| Ta | 3 | 3 | ||||||

| Mt | 3 | 2 | 16 | 16 | ||||

| Extremities | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 102 | 100 | ||

| Mtp indet | 1 | 1 | 1 | 14 | 12 | |||

| Pha1 | 1 | 1 | 44 | 44 | ||||

| Pha2 | 1 | 1 | 19 | 19 | ||||

| Pha3 | 1 | 25 | 25 | |||||

| Indet. | 26 | |||||||

| Articular bone | 1 | |||||||

| Long bone | 25 | |||||||

| 4 | 1 | 31 | 30 | 3 | 3 | 473 | 362 | |

Abbreviations: Cr (cranium), Mx (maxilla), Mand (mandible), Hy (hyoid), Vc (cervical vertebra), Vt (thoracic vertebra), Vl (lumbar vertebra), Vs (sacrum vertebra), Vcd (caudal vertebra), V (indeterminate vertebra), Rb (rib), Sc (scapula), H (humerus), R (radius), U (ulna), Mc (metacarpal), Cp (carpal), Cx (coxal), F (femur), T (tibia), Mt (metatarsal), Pa (patella), As (astragalus), Ca (calcaneus), Ta (tarsal), Mtp (metapodia), Pha (phalanx), Pha R (residual phalanx), Se (sesamoid).

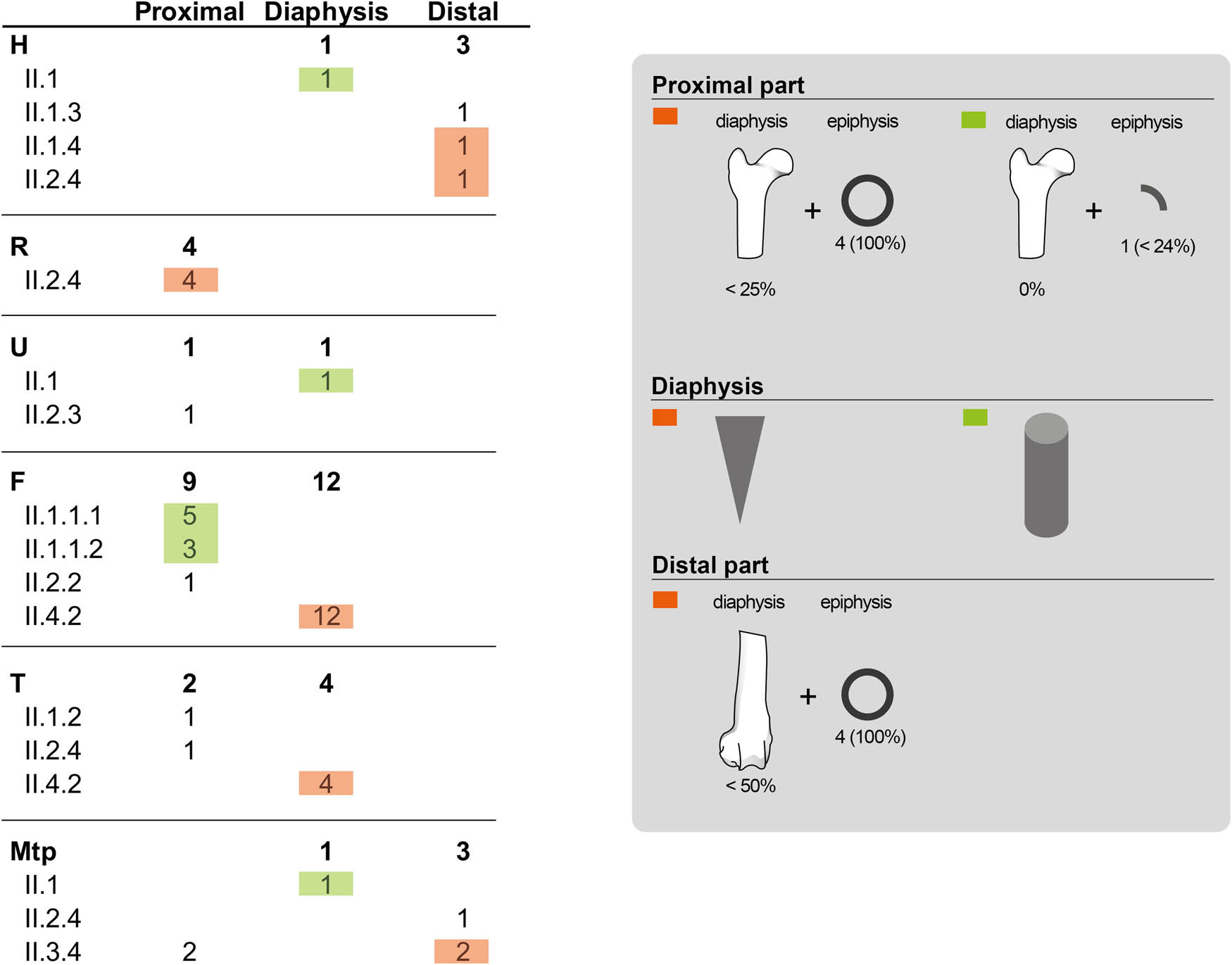

Anatomical representation of Capra pyrenaica (% MAU) and Leporidae (% ISu). Abbreviations are shown in Table 5.

Capra pyrenaica is the most abundant species of ungulates, with 6.2% over the determinate remains, although there are also a few bones from Equus ferus, Cervus elaphus, and Bos primigenius. The anatomical representation by % MAU of Capra pyrenaica shows an incomplete skeleton. Cranial elements, stylopodia and zeugopodia, calcaneus, and astragalus are well-represented with values between 50 and 100% (Table 5, Figure 6). First and second phalanges are also present, but in lower quantities, whereas the axial skeleton and waist are absent.

Equus ferus is represented by one upper molar, a coxal, and two diaphysis of tibia and a metapodial. There is only a hemimandible and a radius of Cervus elaphus, and a teeth fragment from Bos primigenius. Only one carnivore species has been documented, three bones from Felis silvestris: a distal fragment of a humerus, a proximal epiphysis of an ulna, and a complete third phalange.

Regarding the age-at-death, a minimum of one adult individual of Cervus elephus, Equus ferus, Bos primigenius, and Felis silvestris has been calculated. In the case of Capra, there is one infantile individual aging between 1 and 2 years old and one adult (Table 4). In the case of leporids, there is one juvenile, five subadults, and 10 adults.

7.1.2 Taphonomic Analysis

7.1.2.1 Fractures

The assemblage is strongly fragmented, only 17.1% are complete bones. The most abundant category of length is 10–20 mm (75.7%), and only 1.4% are higher than 50 mm.

Regarding ungulates and carnivores, four teeth of Capra pyrenaica, one tooth of Cervus elaphus, and a Felis silvestris phalange are complete. Fragmented remains are represented mainly by fresh and indeterminate fractures (Table 6). Long bones and metapodials diaphysis without complete circumference are the most abundant morphotypes of Capra pyrenaica as well as the remains from other small- to medium-sized specimens. Moreover, other elements like mandible, calcaneus, astragalus, and phalanges are also freshly fractured.

Complete and fractured bones, and type of fractures by species

| Complete | Fragmented | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recent | Fresh | Dry | Mixed | Indet. | ||

| Determinate | ||||||

| Equus ferus | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bos primigenius | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Capra pyrenaica | 4 | 3 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 11 |

| Cervus elaphus | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Felis silvestris | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Leporidae | 172 | 69 | 67 | 65 | 2 | 98 |

| Indeterminate | ||||||

| Very small size | 0 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Small size | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 |

| Small–medium size | 0 | 0 | 61 | 56 | 3 | 53 |

| Medium size | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Medium–large size | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Large size | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 178 | 75 | 151 | 133 | 7 | 171 | |

Leporid bones – without counting remains with recent fractures – are nearly equally complete (42.6%) and fragmented (57.4%) (Table 6). Complete bones include phalanges, metapodials, compact bones, cranial and axial elements, and some non-fused epiphysis of long bones. Concerning the origin of the fractures, 42.2% are indeterminate, 28.9% fresh, 28% dry, and 0.9% mixed. Fresh fractures are located mainly on long bones, but also on metapodials, phalanges, calcaneus and coxal. The most repeated morphotypes on long bones include fragments of diaphysis without complete circumference in the case of femur and tibia; cylinders on humerus and ulna; proximal parts (diaphysis + epiphysis) of femur, radius, and tibia; and distal parts of humerus (Figure 7). Metapodials are fragmented as distal or proximal parts, and there is only one isolated diaphysis.

List of the fresh fractures of long bones metapodials from Leporidae and their specific morphotype (follow Real et al., 2022).

7.1.2.2 Modifications

Thermal alteration is the most abundant modification, though it affects only 5.1% of the identified assemblage (Table 7). Nonetheless, if the percentage is calculated over each species, values increase to 33.3% (medium-sized animals), 25% (Equus ferus), 9% (small- to medium-sized animals), and 7.9% (indeterminate). Charred degree (79.2%) is more important than calcinate (11.3%), affecting the whole bone in 75.5% of the cases.

Anthropogenic and non-anthropogenic modification by species

| Anthropogenic | Non-anthropogenic | Indeterminate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut-marks | Notches | Percussion flakes | Burnt bones | Scores | Bone loss | Digestions | Notches | |

| Equus ferus | 1 | |||||||

| Capra pyrenaica | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Felis silvestris | 1 | |||||||

| Leporidae | 8 | 30 | 2 | |||||

| Very small size | 1 | |||||||

| Small–medium size | 1 | 16 | 11 | 1 | ||||

| Medium size | 8 | 3 | 1 | |||||

| Indeterminate | 25 | |||||||

| NM | 3 | 1 | 8 | 53 | 2 | 1 | 42 | 2 |

| % NISP with M | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 5.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 4.0 | 0.2 |

Total Number of Modifications (NM): Percentage of remains with modification (% NISP with M).

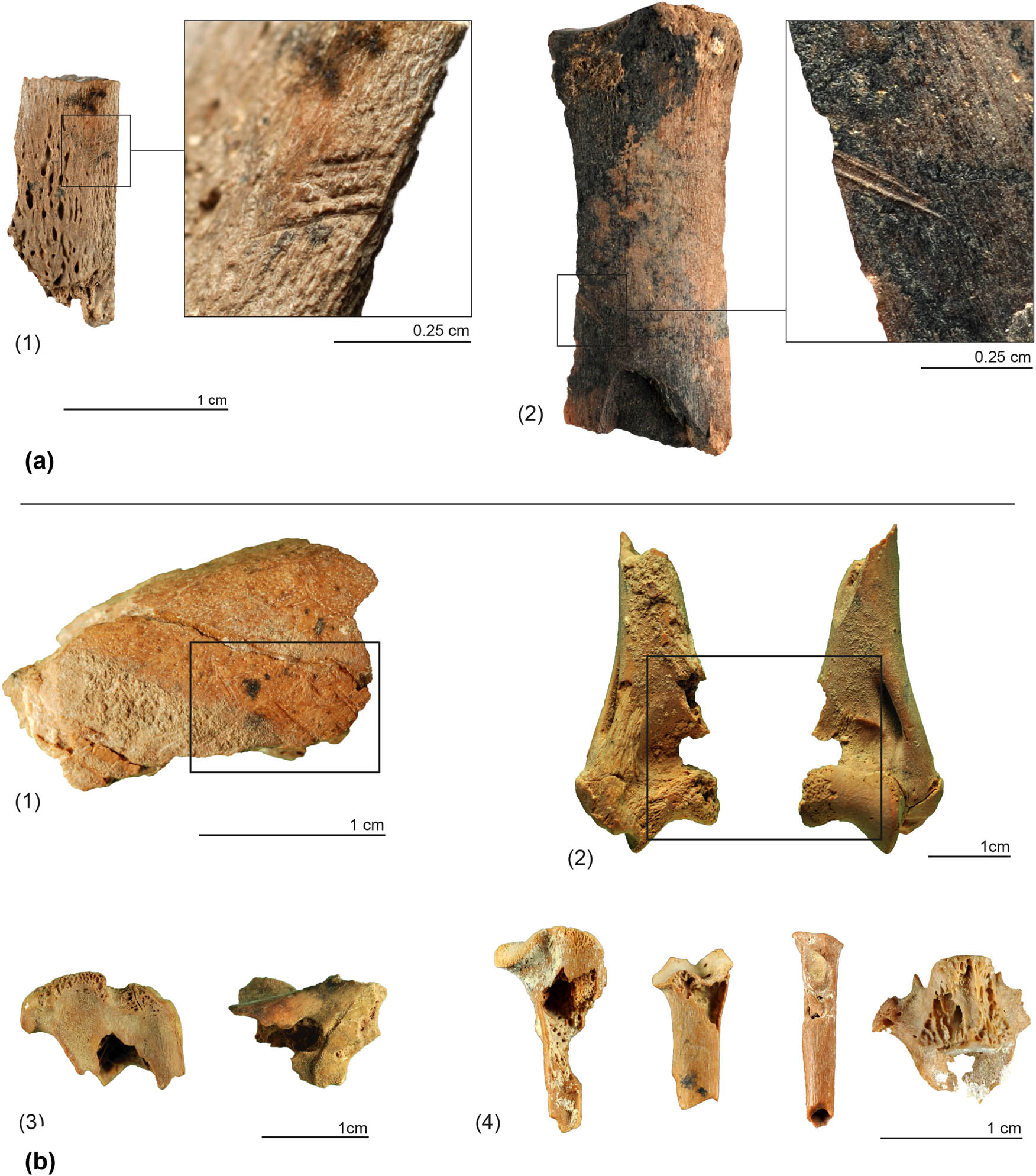

The other anthropogenic modifications are scare (1.2%) (Table 7). There are nine pieces evidencing percussion: eight percussion flakes and a notch on a tibia of Capra pyrenaica. These modifications plus other fresh fractures reflect the access to marrow. Moreover, three bones present cut-marks, all of them short, oblique, and with multiple slicing marks. One cut-mark is on the diaphysis of a small- to medium-sized specimen that could have been caused during the defleshing process. The other two are located on Capra pyrenaica bones including one on the proximal part of a metatarsal diaphysis and another on the distal part of an ulna diaphysis (Figure 8). These marks could be a consequence of skinning and disarticulation activities, respectively.

(a) Anthropogenic modifications: cut-marks on Capra pyrenaica ulna (1) and metatarsal (2). (b) Non-anthropogenic modifications: scores on a diaphysis from a medium-sized specimen (1); bone loss on the distal part of a humerus of Felis silvestris (2); notch on a tibia and a coxal of Leporidae (3); digested bones from Leporidae (4).

Non-anthropogenic modifications have been documented mainly by digestive corrosions (4%) (Table 7), which affect leporids and remains of small- to medium- and very small-sized animals. This corrosion is documented on bones less than 20 mm (85.7%) and between 20 and 40 mm (14.3%). In the case of leporids, most of these remains present a light/moderate level of corrosion (Table 8), with a polished surface, slimming edges, and even porosity on the spongy parts, and affect all kinds of bones, from axial to appendicular fragments (Figure 8).

Remains with digestive corrosion by degree

| Degree of digestive corrosion | Total digt. | % digest. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light (1) | Moderate (2) | Intense (3) | Extreme (4) | |||

| Leporidae | 11 | 10 | 7 | 2 | 30 | |

| Vl | 1 | 1 | 7.7 | |||

| Vt | 1 | 1 | 25.0 | |||

| Rb | 1 | 1 | 11.1 | |||

| H | 1 | 1 | 5.0 | |||

| R | 3 | 1 | 4 | 26.7 | ||

| U | 1 | 1 | 2 | 16.7 | ||

| Cx | 1 | 1 | 2 | 18.2 | ||

| F | 2 | 2 | 4 | 9.3 | ||

| Mt | 1 | 2 | 3 | 18.8 | ||

| As | 1 | 1 | 2 | 66.7 | ||

| Mtp | 2 | 1 | 3 | 21.4 | ||

| Pha1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 6.8 | ||

| Long bone | 3 | 3 | 12.0 | |||

| Very small size | 1 | 1 | ||||

| F | 1 | 1 | 100.0 | |||

| Small–medium size | 4 | 4 | 3 | 11 | ||

| Vl | 1 | 1 | 2 | 66.7 | ||

| Rb | 1 | 1 | 2 | 11.8 | ||

| Long bone | 3 | 3 | 6 | 5.6 | ||

| Articular bone | 1 | 1 | 4.3 | |||

| 15 | 15 | 10 | 2 | 42 | 8.9 | |

Total NR with digestive corrosion (Total digest.); percentage of affected remains over each element (% digest.). For abbreviations see Table 5.

There are also another two non-anthropogenic modifications (0.3%) (Table 7): light, short, and multiple scores on the diaphysis of a long bone of a medium-sized animal, and on a calcaneus of Capra pyrenaica. The latter is located on the edge of a fracture and is associated with its consumption. And a distal part of Felis silvestris humerus shows a partial consumption of the epiphysis with traces of corrosion surrounding the fracture (Figure 8).

Moreover, some notches of an indeterminate origin have been identified, including on a long bone diaphysis of small- to medium-sized animal, on the ilium and the proximal part of a tibia of Leporidae (Figure 8). The notches on the tibia and coxal could have been made by a non-human predator.

7.2 Avifauna

The birds recovered make up a modest set of no more than 51 remains from different squares (C18, C19, D18, D19) in level II, layer 2.

From the results obtained, it should be noted that there are two sizes of birds from the family Corvidae. The first of them, which is more abundant, is medium to small in size. It is compatible in measurements with the genus Pyrrhocorax and specifically closest to Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax. Larger items are compatible in measurements with Corvus corone. Of the five remains identified, three show some degree of corrosion due to digestion.

The other passerines correspond to small birds: three of them are close in size to the thrush and the rest even smaller. It has been difficult to taxonomically classify these elements, and all we dare say is that some could belong to the Paridae family. Of the 37 remains, nine show some degree of corrosion from digestion.

The only piece associated with the genus Columba corresponds to a femur with measurements that make it compatible with either C. livia or C. palumbus. It shows corrosion from digestion. The two remains classified as Perdicinae are compatible in size with the genus Alectoris. They show corrosion from digestion. The two fragments could correspond to the same individual (proximal ulna and distal ulna).

Finally, the remains without any kind of identification could correspond to the aforementioned taxa, although one phalanx is morphologically reminiscent of some small bird of prey, which could be a strigiform or an accipitriciform.

The degree of corrosion from digestion ranges from slight to medium, although the number of unaltered remains exceeds those with digestion marks, and in some cases, they have been strongly digested. Apart from small manganese stains and some elements with slight concretion, no other types of taphonomic alterations are observed. There is no type of mark of an anthropic nature, from thermoalteration, cut marks, or percussion. All this leads us to believe that this is a set that has reached the site in some kind of natural way. Some of the taxa live in caves (Pyrrhocorax and perhaps Columba) and could be birds that died in situ. On the other hand, digestion refers to elements consumed by some type of predator which, due to the low significance of the sample, is difficult to identify. Perhaps, there has been activity by some small- or medium-sized nocturnal predator.

7.3 Micromammals

The morphological and metric analysis of the molars of rodents recovered in the Gravettian levels has allowed us to identify Apodemus sylvaticus, known as the field mouse. It has been identified from eight mandibular fragments and a maxillary fragment, with an incomplete presence of the corresponding molar pieces. We have also identified Iberomys cabrerae from a pair of mandibular first molars among a dozen isolated teeth belonging to the Arvicolidae family.

The species described are common in Upper Pleistocene sites in the Iberian Peninsula and survive to the present day. We should also mention that these three species coexist today in forest ecosystems and open areas with a Mediterranean climate. We should highlight the strict requirements of Iberomys cabrerae, which requires green herbaceous cover throughout the year, with constant high humidity, and no frost or periods of drought.

8 Spatial Distribution

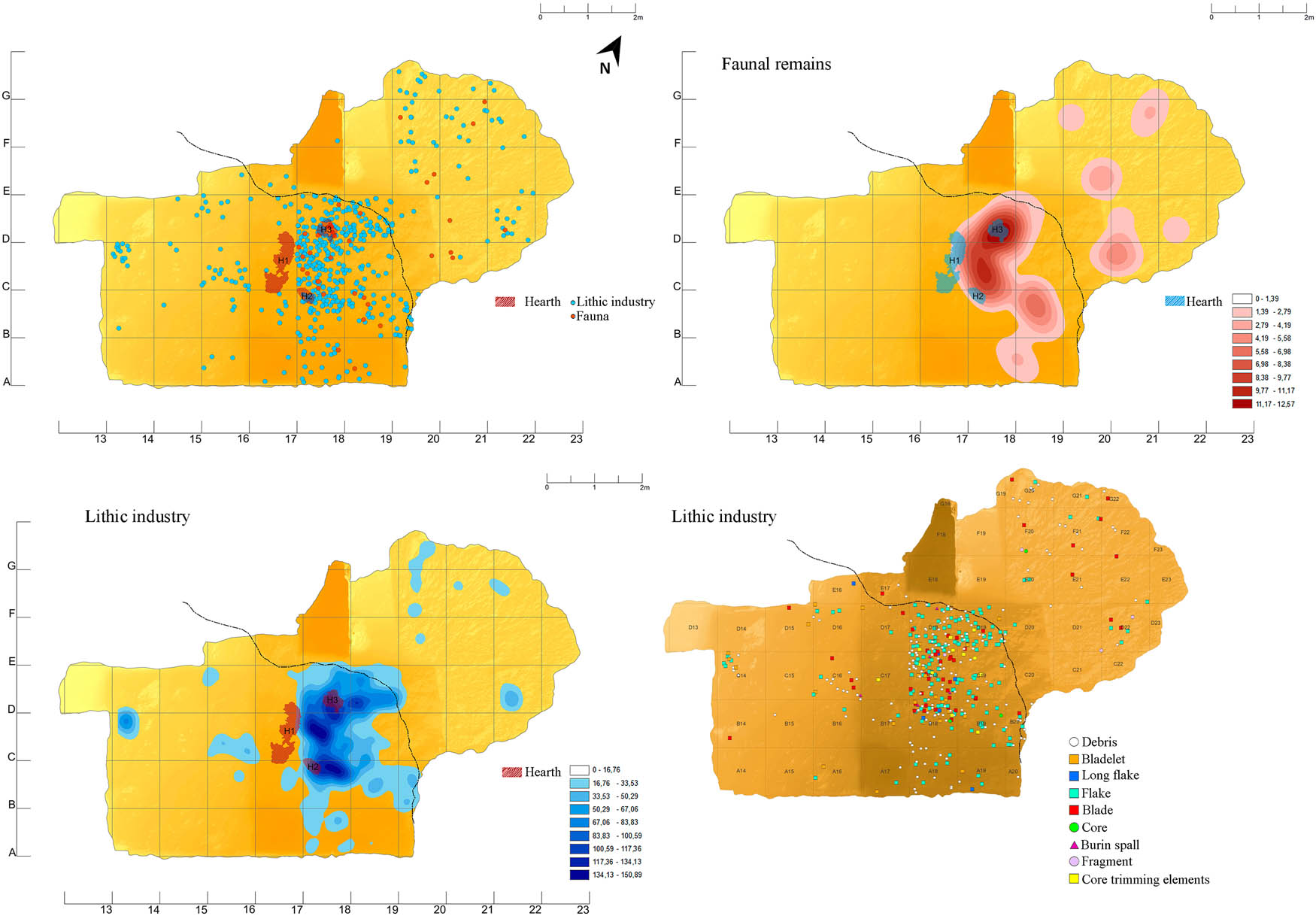

The excavation has provided evidence of three hearths characterised by good preservation conditions (Figure 2d). The three hearths are located next to the drip line of the cavity, marking a spatial separation between the exterior and the interior (Figure 9).

Spatial distribution of lithic industry, faunal remains, and location of preserved hearths.

The spatial distribution of the materials clearly indicates that it is around these hearths where the greatest intensity of occupation was, with most of the industrial and faunal remains being clearly linked to these domestic structures.

It is therefore the area that separates the cavity from the outside where the usual domestic tasks, such as lithic knapping (remains of the entire operational chain are found in this area) and activities related to the processing of fauna, would have been carried out.

9 Palaeoecological Data

9.1 Charcoal Analysis

Charcoal analysis has revealed the use of very few woody species: Ephedra sp. (joint pine), Juniperus sp. (juniper), Pinus halepensis (Aleppo pine), Pistacia sp., Quercus sp. evergreen (holm oak and kermes oak), and Rosmarinus officinalis (rosemary). Juniper accounts for approximately 92% of the wood used, being the rest of the species scarcely represented (Figure 10).

Archaeobotanical remains from Cueva del Arco: 1. Ephedra sp. cross section ×120; 2. Ephedra sp. tangential section ×500; 3. Monocotyledon rhizomes; 4. Pistacia sp. cross section ×120; 5. Pistacia sp. tangential section ×300; 6. Quercus sp. evergreen cross section ×100; 7. Juniperus sp. cross section ×90; 8. Juniperus sp. tangential section ×400; 9. Juniperus sp. radial section ×900; 10. Pinus sp. halepensis cross section ×40; 11. Pinus sp. halepensis radial section ×800; 12. Pinus halepensis cone bract (SEM images, except for photos 3 and 12, which have been taken under a binocular).

Although all species of the genus Juniperus are very similar, Greguss (1959) classifies species with short rays (one–six cells high) and species with long rays (average of more than six cells high). Charcoal identified at Cueva del Arco belongs to the first group, among which the species Juniperus communis, J. excelsa, J. sabina, and/or J. thurifera could be present. In any case, all the species of the genus form open forests, which withstand different temperatures, but conditions of enormous aridity. The presence of Pistacia sp., Pinus halepensis, and Quercus sp. evergreen (although with very low percentages) denotes relatively warm conditions.

The excellent preservation of the wood and the large size of the charcoal fragments (which can reach several cm) have allowed us to corroborate, in the case of Juniperus, the high presence of wood with very weak curvature (more than 80% on average in the samples) and very narrow rings, which is evidence of mature trees: this corroborates the immense exploitation of Juniperus, probably favoured by the enormous abundance and availability of this genus.

9.2 Carpological Analysis

Forty-four carpological remains, including pinecone bracts, bark fragments, rhizomes and stems, were recovered. Most part of the assemblage is composed of Pinus sp. cone bracts (Figure 10, no 12), some of them identified as Pinus halepensis. Two fragments of rhizomes and one stem of Monocotyledon plants were also documented (Figure 10, no 3). Moreover, an uncharred macrospore of Isoetes sp. was recovered.

The carpological assemblage shows low taxonomical diversity in the current state of the analysis, but future works including the analysis of flotation samples could increase the number of taxa, especially considering the good state of preservation of the archaeobotanical remains.

9.3 Palynologycal Analysis of Five Coprolites

The five coprolites studied for pollen (samples ID Arc-Cop1 to Arc-Cop5; Figure 11) were collected during the 2017 fieldwork campaigns, in Level II (squares C-19 and C-18 of the excavations grid; Table 9). These coprolites were fragmented and morphologically could not be associated with their producing species. Although they are very frequent in Palaeolithic sites and indeed subject of palynological investigations (Carrión et al., 2001, 2007, 2008, Carrión Marco et al., 2018, 2019; Ochando et al., 2020), hyaena coprolites can be discarded on the basis of coprolite morphology. The Arco coprolite fragments might therefore correspond to other medium to small species, which would be coherent with the faunal findings at Level II (Table 9).

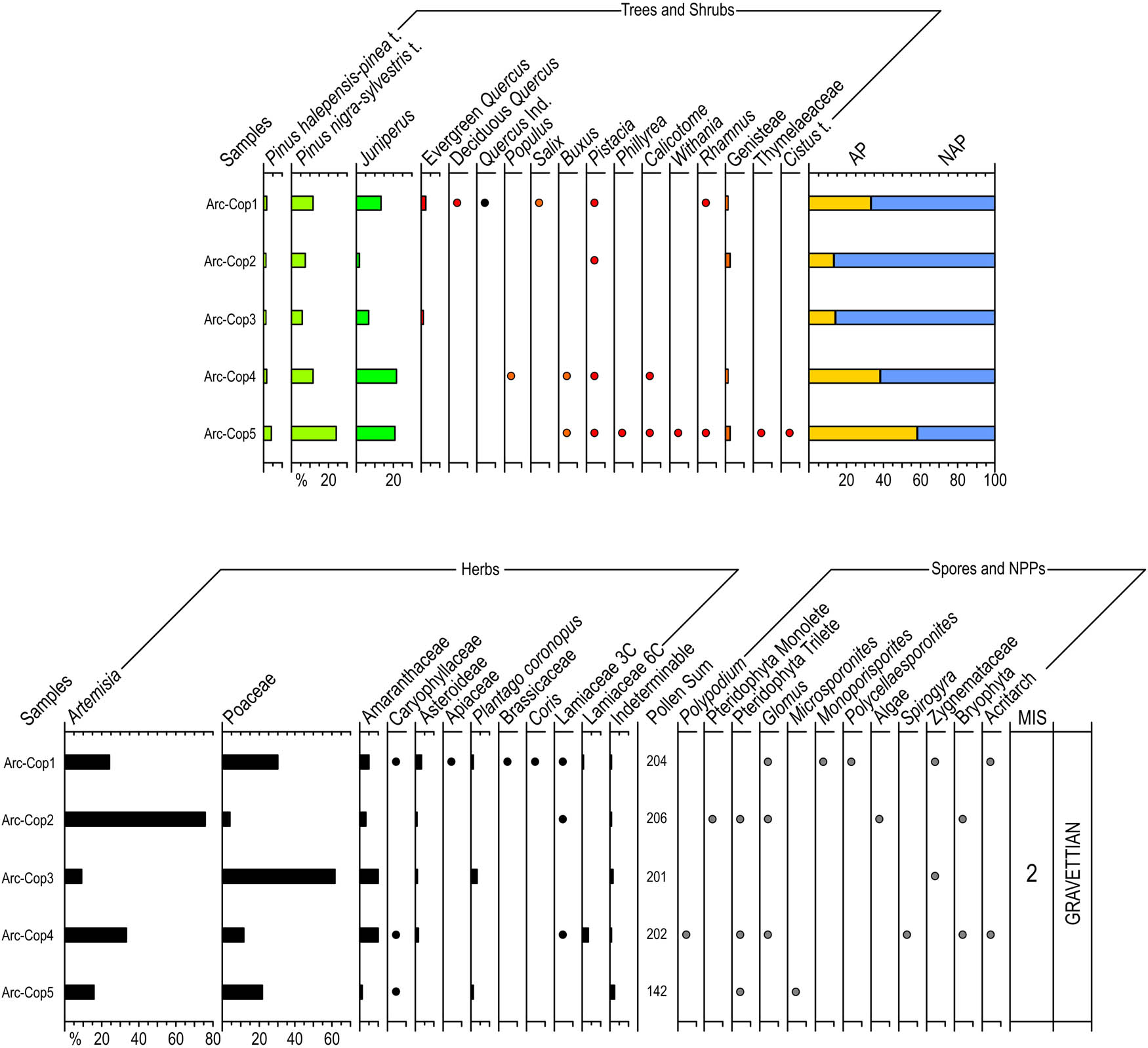

Percentage pollen diagram of the coprolites of Cueva del Arco including Trees, Shrubs, Herbs, Spores and NPPs, summatory of AP and NAP. Black dots for percentages below 2.

Summary of palynological features of Cueva del Arco samples

| Sample | Level | Square | Material bag | Net Weight (g) | Concentration (grains/g) | Indeterminable (%) | (a)Pollen sum | Pollen sum with Asteroideae | Number of taxa (Pollen) | Spores sum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coprolites | ||||||||||

| Arc-Cop1 | II | C-19 | 129 | 2.02 | 7019.71 | 1.47 | 204 | 211 | 21 | 12 |

| Arc-Cop2 | II | C-19 | 130 | 10.74 | 2914.32 | 0.48 | 206 | 207 | 10 | 11 |

| Arc-Cop3 | II | C-19 | 134 | 0.84 | 23842.73 | 1.49 | 201 | 203 | 9 | 1 |

| Arc-Cop4 | II | C-18 | 135 | 3.83 | 4136.58 | 0.99 | 202 | 205 | 15 | 18 |

| Arc-Cop5 | II | C-18 | 136 | 0.41 | 20074.82 | 2.81 | 142 | 142 | 17 | 4 |

| TOTAL | 955 | 968 | 46 | |||||||

(a)Asteroideae excluded.

A pollen diagram representing Trees, Shrubs, Herbs, Spores, and NPPs (non-pollen palynomorphs) was prepared (Figure 11), together with a summatory of arboreal pollen (AP) and non-arboreal pollen (NAP). It should be emphasised that the number of spores and NPPs present in the coprolites was relatively low (Table 9). A total of 1,014 palynomorphs were identified, counting 968 pollen grains and 46 spores and NPPs. Along with spores and NPPs, we excluded from the total pollen sum the counts of Asteroideae assuming it might be overrepresented due to local occurrences. The percentage of indeterminable types remained in values lower than 3 (Table 9). The number of pollen types varies between 9 and 21, with a total of 28 recognised taxa. The number of palynomorphs extracted from the coprolites ranges between 2914.32 and 23842.73 grains/g (Table 9).

All the coprolites were polleniferous (Table 9, Figure 11). The pollen sum varied between 142 and 211 pollen grains. NAP is predominant across all samples, reaching values >86%, except in coprolite Arc-Cop5, in which the lowest percentage of NAP (41%) is reached. The most noteworthy characteristics of this level are the abundance of Artemisia (9–76%), Poaceae (4–61%), and Amaranthaceae (1–10%), while Plantago does not exceed 4%. Other NAP includes Asteroideae (counted out of the pollen sum), Caryophyllaceae, Apiaceae, Brassicaceae, Coris, and Lamiaceae. Among AP (Figure 11), Pinus nigra-sylvestris (6–24%) and Juniperus (2–22%) are remarkable, while Pinus halepensis-pinea is below 5%. The occurrence of evergreen Quercus, Pistacia, and Genisteae are also ecologically meaningful, as well as the frequencies of deciduous Quercus, Populus, Salix, Buxus, Phillyrea, Calicotome, Withania, Rhamnus, Thymelaeaceae, and Cistus. Fungal spores, algae, bryophyta, pteridophyta, and NPPs do not abound (Figure 11, Table 9) although the occurrences of Pteridophyta, Triletes, Glomus, Zygnemataceae, and Acritarch are occasionally noticeable.

Coprolite pollen assemblage is co-dominated by three or four of the main pollen contributors, namely Pinus nigra-sylvestris, Juniperus, Artemisia, and Poaceae (Figure 11). Exceptions include Arc-Cop2 and Arc-Cop3 exclusively dominated by Artemisia and Poaceae, respectively. Palaeoecologically, the pollen spectra involve the occurrence of diverse trees, shrubs, and herbs, with broad-leaf trees, Mediterranean components, conifers, xerothermophytes, indicators of saline substrates, and heliophytes such as Asteroideae and Cistaceae. The xero-heliophytic component (Poaceae, Artemisia, Amaranthaceae) has a high cover. The woody component is relatively low (with the exception of samples Arc-Cop5), which includes a combination of mesophytes, such as deciduous trees (deciduous Quercus, Populus, and Salix), and Mediterranean taxa in addition to evergreen oaks and pines (Buxus, Pistacia, Calicotome, Cistus, Withania, Phillyrea, and Rhamnus). According to the aforementioned data, the Palaeolithic vegetation surrounding Cueva del Arco would include wormwood, grass, pine, oak, juniper, pistacia, and wormwood steppes, open parklands, riverine forest patches, helophytic matorrals, rocky scrub with hemicryptophytes and shrubby grasslands.

10 The Early Upper Palaeolithic at Cueva del Arco in the Iberian Mediterranean Context

The data obtained from the excavations in Cave A at Cueva del Arco have allowed us to document an interesting occupation site from the beginning of the Gravettian period. It also opens up the possibility of the existence of some Evolved Aurignacian occupation.

For the Aurignacian, if we accept its presence around the two dates obtained, we must imagine sporadic occupation by these pioneering human groups. It is probable that this limited occupation has been integrated into the Gravettian materials. If so, and given the characteristics of the site, we do not believe that these materials are statistically important, although at La Boja site it has been suggested that at the end of this period the backed bladelets, of which we have some examples at Arco, replace the Dufour bladelets (Zilhão et al., 2017).

The occupations of the end of the Aurignacian at sites such as Cova de les Cendres or Malladetes show few materials (Villaverde et al., 2019, 2021). The general perception is that these first groups of anatomically modern humans (AMH) arriving in the Iberian Mediterranean did not manage to settle definitively in the region and were organised in small and possibly highly mobile groups that left few materials evidence. They did not finally settle until the Gravettian period. This evolution is what could be represented at Cueva del Arco itself.

The Gravettian period has received a great deal of attention in recent years in the Mediterranean Iberia. Recent excavations at various sites have allowed new studies showing the importance of this period for the consolidation of the settlement by AMH south of the river Ebro (De la Peña & Vega Toscano, 2013; Villaverde & Román, 2004, 2013; Villaverde et al., 2019, 2021; Zilhão et al., 2017).

The Gravettian is characterised by the manufacture of backed projectiles, to which splintered pieces and some truncations are added. This period can be divided into three phases, although the changes at the industrial level are small and have to do in particular with a greater or lesser occurrence of gravettes and microgravettes (Villaverde et al., 2019). Despite this homogeneity in the stone tools, some features can also be made out that could show a degree of regionalisation with respect to neighbouring areas such as the Cantabrian Sea or the Pyrenees. This concerns the presence of particular pieces such as the Cendres type points (Villaverde & Román, 2004; Villaverde et al., 2019) and the absence or very low frequency of pieces highly characteristic in other territories such as the Noailles burins (according to Zilhão et al., 2017 there are some pieces from the mid-Gravettian at Finca Doña Martina site).

Chronologically, we currently have 68 Gravettian dates and 13 for the end of the Aurignacian period from 14 sites (Table 10, Figure 12)[1]. The analysis of all these dates allows us to propose the date of 31500 cal. BP as the beginning of the Gravettian period in the Iberian Mediterranean. At this time, the Aurignacian period seems to end. These limits coincide with some recent Bayesian studies in which it has been proposed that the end of the Aurignacian could be between 31600 and 30400 cal. BP and the beginning of the Gravettian between 31700 and 30900 cal. BP (Martínez-Alfaro et al., 2022; Villaverde et al., 2021).

List of radiocarbon dates from the Gravettian sites from Mediterranean Iberia

| SITE | LEVEL | REF. LAB. | BP | ± | Cal. BP (95%) | SAMPLE | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arco | IIa | ETH-67833 | 26193 | 104 | G | 30840–30200 | C | Martín-Lerma et al., 2023 |

| Arco | IIa | ETH-67834 | 26279 | 106 | G | 30880–30320 | C | Martín-Lerma et al., 2023 |

| Arco | IIa | VERA-7068 | 26151 | 172 | G | 30890–29930 | C | Martín-Lerma et al., 2023 |

| Arco | IIb | VERA-7063 | 28617 | 287 | A/G? | 33580–31620 | C | Martín-Lerma et al., 2023 |

| Arco | III | Beta-627630 | 31190 | 190 | A | 36091–35203 | S | Unpublished |

| Barriada | A | Beta-296222 | 22750 | 110 | G | 27430–26750 | C | Fernandez et al., 2011 |

| Barriada | B | Beta-296223 | 25260 | 120 | G | 29660–28940 | C | Fernandez et al., 2011 |

| Barriada | C | Beta-362534 | 27140 | 160 | G | 31300–30940 | C | Fernandez et al., 2011 |

| Cendres | XIV-XV | Beta-437194 | 22190 | 80 | G | 26495–26285 | C | Villaverde et al., 2019 |

| Cendres | XV | Beta-142282 | 21230 | 80 | G | 25820–25340 | C (PN) | Villaverde & Román, 2004 |

| Cendres | XV? | Beta-287546 | 20800 | 110 | G | 25480–24640 | C | Villaverde & Román, 2013 |

| Cendres | XVIA | Beta-437195 | 22750 | 110 | G | 27430–26750 | C | Villaverde et al., 2019 |

| Cendres | XVIA | Beta-303419 | 23350 | 100 | G | 27750–27390 | C (QP) | Villaverde & Román, 2013 |

| Cendres | XVIA | Beta-287548 | 23920 | 100 | G | 28230–27710 | C | Villaverde & Román, 2013 |

| Cendres | XVIA | Beta-287549 | 23860 | 100 | G | 28140–27700 | C | Villaverde & Román, 2013 |

| Cendres | XVIA-inf | Beta-142283 | 24240 | 220 | G | 28760–27800 | C | Villaverde & Román, 2004 |

| Cendres | XVIA | Beta-155606 | 24080 | 150 | G | 28510–27750 | C | Villaverde & Román, 2004 |

| Cendres | XVIA? | Beta-295148 | 21880 | 100 | G | 26320–25880 | C (R) | Villaverde & Román, 2013 |

| Cendres | XVIA-sup | Beta-437196 | 24850 | 110 | G | 29170–28610 | C | Villaverde et al., 2019 |

| Cendres | XVIB-sup | Beta-437197 | 26020 | 130 | G | 30780–29780 | C | Villaverde et al., 2019 |

| Cendres | XVIB | Beta-437823 | 25590 | 100 | G | 30150–29350 | C (A) | Villaverde et al., 2019 |

| Cendres | XVIB | Beta-189078 | 25850 | 260 | G | 30790–29350 | C (PN) | Villaverde & Román, 2004 |

| Cendres | XVIB | Beta-287537 | 25600 | 140 | G | 30280–29280 | C | Villaverde & Román, 2013 |

| Cendres | XVIB-inf XVIC-sup | Beta-437198 | 26580 | 90 | G | 31000–30680 | C | Villaverde et al., 2019 |

| Cendres | XVIC? | VERA6428A | 26970 | 190 | G? | 31280–30780 | C (PN) | Villaverde et al., 2019 |

| Cendres | XVIC? | VERA6428A | 27560 | 240 | G? | 31880–31020 | C (PN) | Villaverde et al., 2019 |

| Cendres | XVIC | Beta-437199 | 28450 | 110 | A/G? | 32960–31800 | C | Villaverde et al., 2019 |

| Cendres | XVIC | Beta-437193 | 28690 | 160 | A/G? | 33380–32180 | C | Villaverde et al., 2019 |

| Cendres | XVIC | VERA6427A | 29270 | 260 | A | 33960–32860 | C (PN) | Villaverde et al., 2019 |

| Cendres | XVIC | VERA6427A | 29490 | 260 | A | 34140–33100 | C (PN) | Villaverde et al., 2019 |

| Cendres | XVID | Beta-458346 | 31080 | 170 | A | 35340–34620 | C (J) | Villaverde et al., 2019 |

| Moro | Beta-464213 | 22230 | 80 | G | 26754–26150 | C | Roman et al., 2021 | |

| Moro | Beta-464211 | 23730 | 90 | G | 27984–27625 | C | Roman et al., 2021 | |

| Casa Moliners | IV | Beta-438707 | 23780 | 180 | G | 28210–27570 | C | Miret et al., 2016 |

| Comte | SU1001 | Beta-413715 | 25050 | 100 | G | 29430–28750 | C | Casabó et al., 2016 |

| Comte | SU1002 | Beta-413716 | 24010 | 90 | G | 28330–27770 | C | Casabó et al., 2016 |

| Malladetes | VII | VERA-6607 | 23150 | 130 | G | 27660–27220 | C | Villaverde et al., 2021 |

| Malladetes | VII | VERA-6608 | 23840 | 150 | G | 28230–27630 | C | Villaverde et al., 2021 |

| Malladetes | IX | VERA-6610 | 23530 | 140 | G | 27880–27480 | C | Villaverde et al., 2021 |

| Malladetes | IX | VERA-6612 | 24090 | 150 | G | 28520–27760 | C | Villaverde et al., 2021 |

| Malladetes | IX | VERA-6613 | 24170 | 160 | G | 28610–27810 | C | Villaverde et al., 2021 |

| Malladetes | IX | VERA-6616 | 24230 | 150 | G | 28660–27860 | C | Villaverde et al., 2021 |

| Malladetes | X | VERA-6617 | 24380 | 180 | G | 28820–27980 | C | Villaverde et al., 2021 |

| Malladetes | X | VERA-6618 | 24280 | 160 | G | 28730–27890 | C | Villaverde et al., 2021 |

| Malladetes | X | VERA-6503 | 24180 | 150 | G | 28600–27840 | C | Villaverde et al., 2021 |

| Malladetes | X? | Beta-155607 | 25120 | 240 | G | 29720–28640 | C | Villaverde et al., 2021 |

| Malladetes | XI | VERA-6504 | 26080 | 180 | G | 30880–29760 | C | Villaverde et al., 2021 |

| Malladetes | XI | VERA-6505 | 25820 | 170 | G | 30600–29480 | C | Villaverde et al., 2021 |

| Malladetes | XI | VERA-6506 | 25930 | 170 | G | 30740–29580 | C | Villaverde et al., 2021 |

| Malladetes | XI | VERA-6507 | 26120 | 180 | G | 30900–29820 | C | Villaverde et al., 2021 |

| Malladetes | XII | VERA-6508 | 30100 | 280 | A | 34660–33700 | C | Villaverde et al., 2021 |

| Malladetes | XIII | VERA-6509 | 29520 | 270 | A | 34150–33190 | C | Villaverde et al., 2021 |

| Malladetes | XII | KN-1/926 | 29690 | 560 | A | 34820–32620 | C | Fortea & Jordá, 1976 |

| Angel 1 | 10 med b | GrA-16961 | 25330 | 190 | G | 29890–28890 | C | Utrilla & Domingo, 2001 |

| La Boja | OH12 | VERA-5852 | 23530 | 150 | G | 27899–27434 | C | Zilhão et al., 2017 |

| La Boja | OH13 | VERA-5789 | 27260 | 230 | G | 31483–30895 | C | Zilhão et al., 2017 |

| La Boja | OH15 | VERA-6153 | 30548 | 363 | A | 35137–33891 | C | Zilhão et al., 2017 |

| La Boja | OH16 | VERA-6154 | 30686 | 355 | A | 35289–33989 | C | Zilhão et al., 2017 |

| La Boja | OH17 | VERA-6156 | 30918 | 359 | A | 35561–34165 | C | Zilhão et al., 2017 |

| Finca DM | 6_7 | VERA-6170HS | 24450 | 170 | G | 28837–28058 | C | Zilhão et al., 2017 |

| Finca DM | 6_7 | VERA-5367HS | 23480 | 150 | G | 27864–27408 | C | Zilhão et al., 2017 |

| Finca DM | 7b | VERA-5368 | 26990 | 220 | G | 31312–30765 | C | Zilhão et al., 2017 |

| Nerja | V11 | Beta-102023 | 24730 | 250 | G | 29320–28240 | C | Jordà & Aura, 2008 |

| Nerja | V13 | Beta-189080 | 24200 | 200 | G | 28700–27780 | C | Jordà & Aura, 2006 |

| Nerja | V11_13 | Beta-131576 | 24480 | 110 | G | 28710–28030 | C | Arribas et al., 2004 |

| Palomar | III | Beta-185409 | 21560 | 110 | G | 26050–25650 | B | De la Peña & Vega Toscano, 2013 |

| Palomar | IV | Beta-85410 | 26430 | 210 | G | 31070–30270 | B | De la Peña & Vega Toscano, 2013 |

| Palomar | V | Beta-185411 | 26230 | 200 | G | 30960–30000 | B | De la Peña & Vega Toscano, 2013 |

| Palomar | VI | Beta-185412 | 28050 | 230 | G/A? | 32650–31210 | B | De la Peña & Vega Toscano, 2013 |

| Ratlla Bubo | II | Beta-565510 | 23620 | 90 | G | 27901–27556 | C | Martínez-Alfaro et al., 2022 |

| Ratlla Bubo | II | Beta-565511 | 21190 | 80 | G | 25748–25284 | C | Martínez-Alfaro et al., 2022 |

| Ratlla Bubo | II | Beta-565512 | 22270 | 90 | G | 26886–26174 | C | Martínez-Alfaro et al., 2022 |

| Ratlla Bubo | II | Beta-565513 | 25740 | 100 | G | 30340–29529 | C | Martínez-Alfaro et al., 2022 |

| Ratlla Bubo | III_IV | Beta-565518 | 25890 | 100 | G | 30552–29701 | C | Martínez-Alfaro et al., 2022 |

| Ratlla Bubo | IV | Beta-565519 | 21770 | 80 | G | 26161–25835 | C | Martínez-Alfaro et al., 2022 |

| Ratlla Bubo | IV | Beta-565520 | 21450 | 90 | G | 25950–25577 | C | Martínez-Alfaro et al., 2022 |

| Ratlla Bubo | IV | Beta-565521 | 21890 | 80 | G | 26325–25905 | C | Martínez-Alfaro et al., 2022 |

| Ratlla Bubo | IV | Beta-565522 | 24780 | 90 | G | 29050–28554 | C | Martínez-Alfaro et al., 2022 |

| Ratlla Bubo | IV | Beta-565524 | 24500 | 90 | G | 28780–28300 | C | Martínez-Alfaro et al., 2022 |

| Cova Foradada | IIIn | OxA-24646 | 26570 | 120 | G | 31045–30610 | M | Morales et al., 2019 |

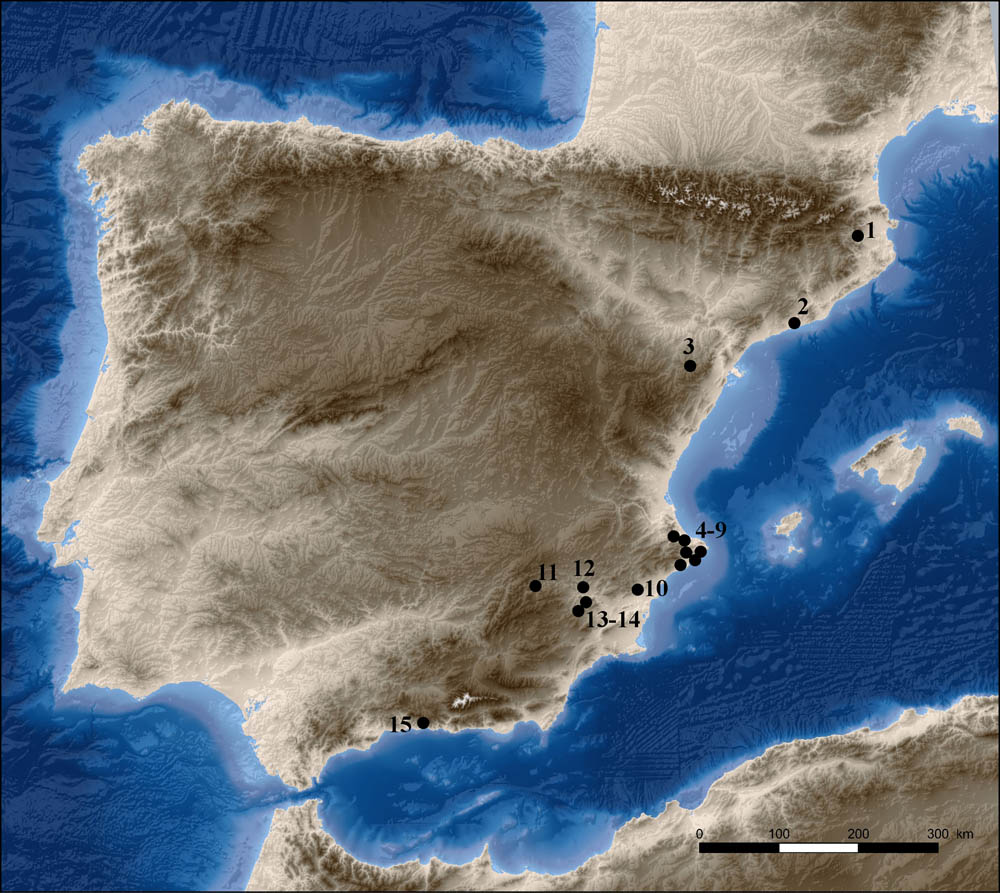

At Cueva del Arco, we find occupations from the beginning of the Gravettian period, chronologically comparable with several sites in the Mediterranean Iberian Peninsula dated between 31500 and 30500 cal BP (Foradada de Calafell, Malladetes, Cendres, Barriada, Palomar, La Boja, and Finca Doña Martina) (Figure 13), with most of the oldest sites concentrated in the centre and southeast. The presence in Catalonia of Cova Foradada (Morales et al., 2019) makes it possible to confirm, as is logical to think if the Gravettian spread from eastern Europe, that sites from these initial stages also exist in the northern part of the Iberian Mediterranean.

Gravettian sites cited in the text. 1. Arbreda; 2. Foradada; 3. Ángel 2; 4–9. Malladetes, Parpalló, Casa dels Moliners, Moro, Cendres, Barriada; 10. Ratlla del Bubo; 11. Palomar; 12. Arco; 13–14. Boja y Finca Doña Martina; 15. Nerja.

The Gravettian faunal assemblage from Cueva del Arco presents a taxonomic spectrum coinciding with those already seen in other faunal assemblages from this period in the Iberian Mediterranean area (e.g. Aura Tortosa et al., 2012; Iturbe et al., 1993; Rufí et al., 2019; Villaverde et al., 2019, 2021). At Cueva del Arco, leporids are the dominant taxon (45%) within the determined remains. Among the macrofauna, there is a higher abundance of Spanish ibex, and a lower presence of other ungulate species (red deer, auroch, horse) and only one carnivore species (wild cat). The proportion between the most represented ungulates follows the pattern present in other assemblages from inland/mountainous zones of the Iberian Mediterranean area, where Spanish ibex is more hunted, such as Cova de les Malladetes or Cova Beneito (Iturbe et al., 1993; Sanchis et al., 2023). Moreover, this pattern departs somewhat from the northern sites such as at Cova de l’Arbreda, where horse remains constitute a higher number of instances (Nadal et al., 2005; Rufí et al., 2021).

The anatomical representation of Spanish ibex is biased, as shown by the absence of the axial skeleton and the waists, although it is possible that some axial remains of a small- to medium-sized specimens belong also to the Spanish ibex. Despite these data, and given the reduced NR, we are unable to determine how this prey was transported, although its size could indicate a complete transportation, as other assemblages point out, such as Cova del Comte (Casabó et al., 2016) or Cova de les Cendres (Villaverde et al., 2019).