Abstract

Natives of the Low Rhine region, the Batavi were a community of ethnic soldiers engaged in a treaty with Rome, overseeing a heavy supply of men to the Roman auxiliary units. The present article examines the pottery discovered at and retrieved from three sites associated with Batavian auxilia: Războieni, Adony, and Romita. Their status as military sites shaped around the consumption habits of Batavian auxiliary troops makes them comparable. The comprehensive examination of pottery consumption patterns provides valuable insights into the dynamics of material culture in Dacia and Pannonia, facilitating our understanding of supply networks, consumption preferences, and cultural interactions within these frontier regions. The quantitative analyses of fabric and form distributions reveal distinctive trends at each site, reflecting variations in local production, regional trade networks, and social practices. The qualitative interpretations highlight the significance of certain vessel types and their cultural associations. While in the overall perspective, they emphasise the similarity between pottery consumption at the three forts shaped by military presence and regional trade networks, they also highlight potential markers of Batavian identity within the auxiliary units stationed there. By contextualising pottery within broader historical and archaeological frameworks, this research contributes to a more nuanced understanding of the cultural aspects of auxilia.

1 Introduction

Natives of the Low Rhine region (modern Netherlands – Nijmegen area), the Batavi were a community of ethnic soldiers engaged in a treaty with Rome and led by their native aristocracy, overseeing a heavy supply of men to the Roman auxiliary units. Loyal and fierce, they soon became elite soldiers, the emperors’ personal guards, and some of the Empire’s most valued auxiliaries. Regardless of (as well as due to) their extraordinary status, in AD 69, they were the protagonists of one of the fiercest rebellions faced by the Roman Empire during the first century.

The present article, part of a wider research, examines the pottery discovered at and retrieved from three Batavian sites: Războieni, Adony, and Romita. Their status as military sites shaped around the consumption habits of Batavian auxiliary troops makes them comparable. It is a known fact that the Batavians’ material culture is remarkably modest and unspecific; researchers use the term loosely to refer to material finds from the area they consider to belong to Batavian territory, but much of this is widespread in the area of the Lower Rhine. For comparison, the neighbouring tribe, the Cananefates distinguish themselves by retaining their traditional hand-made pottery at least until about 160/200 AD (De Bruin, 2019).

Meanwhile, the Batavians change to imported pottery as early as the first century AD. While somehow elusive, material culture holds the key to our understanding of the Batavians’ integration, acculturation, and becoming during the late second and third centuries. Early on, the unicity of Batavian material culture did not consist of specific pottery types, but rather unusual combinations of universal pottery styles. This became particularly obvious in the rural cemeteries of returning Batavian veterans, who combined the indigenous Gallo-Belgic beakers with the more cosmopolitan and military-related colour-coated beakers. These selections spoke on the multi-faceted identity of these soldiers as part of the process of Batavian ethnogenesis (Pitts, 2019, p. 189; Roymans, 2004).

This article aims to explore the supply and utilisation of vessel fabric, form class, and type at Războieni, Romita, and Adony, spanning Dacia and Pannonia from the early second century through the third century. This comprehensive examination will facilitate an understanding of vessel origins and their integration into regional contexts. The three sites serving as case studies played a role in both local and wider regional supply networks, connecting not only regionally with neighbouring sites but also cross-provincially with one another, as evidenced by imports of sigillata, colour-coated wares, local coarse wares, and Pannonian slipped wares (PSWs), which will be further explored below through the lens of social practice by highlighting pottery-associated behaviours such as supply, demand, and replication to illuminate the expression of identity within the pottery from these three forts associated with Batavian units.

2 Methodology

The methodology presents each site within its specific context, including its historical development, the relevant facts about the troop and their interactions, and the archaeological findings. The latter is especially significant for understanding the pottery under analysis. As the reader will see, the processes of excavation, data collection, and recording vary significantly across the sites, and in no case are we dealing with fully excavated sites. However, it is important to note that in each case, we personally examined the ceramic material and brought it to a comparable standard, regardless of the methodological setbacks. Therefore, the analyses presented here are based on our direct interaction with the artefacts, rather than relying on bibliographic sources or excavation reports when referring to the three case studies.

Methodological aspects have been discussed independently in regards to each site. This section, however, aims to show the more general framework of data collection applied across the three sites. Two types of data have been recorded, qualitative and quantitative. Qualitative data refer to the descriptive information on the qualities or attributes of the pottery, meaning that it is often expressed in a narrative form.

Fabric: This field designates the main fabric categories at the sites under analysis. They have been assigned according to:

their firing type (oxidised [OXID], reduced [COAR]),

level of coarseness (oxidised fine [OXIDF], reduced fine [FINE], and terra sigillata imitations [TS IMIT, PSW]), and

those that have traditionally been their own categories (mortaria [MORT] and amphorae [AMPH]).

Form class: It designates the main morphological categories of vessels, such as flagons (FL), bowls (BO), dishes (DS), beakers (BE), jars (JA), lids (LID), turibula (TUR), mortaria (MORT), and amphorae (AMPH). They have been defined according to Webster’s “Romano-British coarse pottery: a student’s guide” (1969), except the authors have merged the categories of “dish” and “platter” into the one of “dish,” to declutter the already abundant terminology existent on this matter.

Form type: It refers to the sub-categories of each form class, such as flat/round-rimmed bowls, everted rim jars, and storage jars. These categories have been developed according to the Museum of London Archaeology Roman pottery form codes. Where possible the types have been linked to existing typologies, to pinpoint exact analogies.

Functional categories: this tends to be a rather loose term that assumes the way vessels would have been used. However, throughout the text, the term “tablewares” has been employed to simply designate one concept when mentioning dishes and bowls at the same time. Similarly, when referring to jars, cooking/storage wares have been employed.

While the first two levels of assessment, the fabrics and form classes, provide wider and sometimes shallow perspectives, more suitable for a general characterisation, the third layer of assessment, the form types, offers a glimpse into the ways identities may have been negotiated via pottery consumption and practices among the Batavian auxilia in this case. This type of information highlights the diversity of styles, decorations, forms, and types of pottery involved in consumption at any site as part of the typological analysis of circulating forms in their wider imperial setting. This step is essential in the methodological approach to the material under analysis, since it collates the data into a comprehensive typology, which not only offers an overview of the selections at any site but is also suitable for further regional, national, and international comparisons.

Quantitative data refer to the information which describes the amount of analysed data, and it is often expressed in a numerical form. Primary data were collected first hand from the three case studies, allowing freedom in selecting the quantification methods. The main criterion in this process was to make the primary data compatible with already published local sites, especially when inter-site comparisons occurred. Therefore, Războieni, Adony, and Romita were quantified both by a minimum number of rims (MNR). The data quantification plays a crucial role in understanding the ratios of the qualitative attributes discussed above. Once obtaining this information, one can use it for intra- and inter-site analyses (e.g. Evans, 1985; Evans et al., 1988; Pitts, 2019; Willis, 2011).

3 Războieni, Adony, and Romita: Motivation and Historical Overview

After the AD 69 revolt, the Batavian troops were reorganised (Alföldy, 1968, pp. 47–48; Spaul, 2000) from nine cohorts that existed before the rebellion to four only. At least two of these new cohorts (certainly the second and third) were cohortes equitatae, meaning that they also had a cavalry intervention group, and all of them became miliariae by the second century. The ala, which was the elite cavalry troop, was a milliaria, theoretically comprising 1,000 men (around 800 realistically) who were highly skilled riders, often from traditional military families and trained for a military career since childhood.

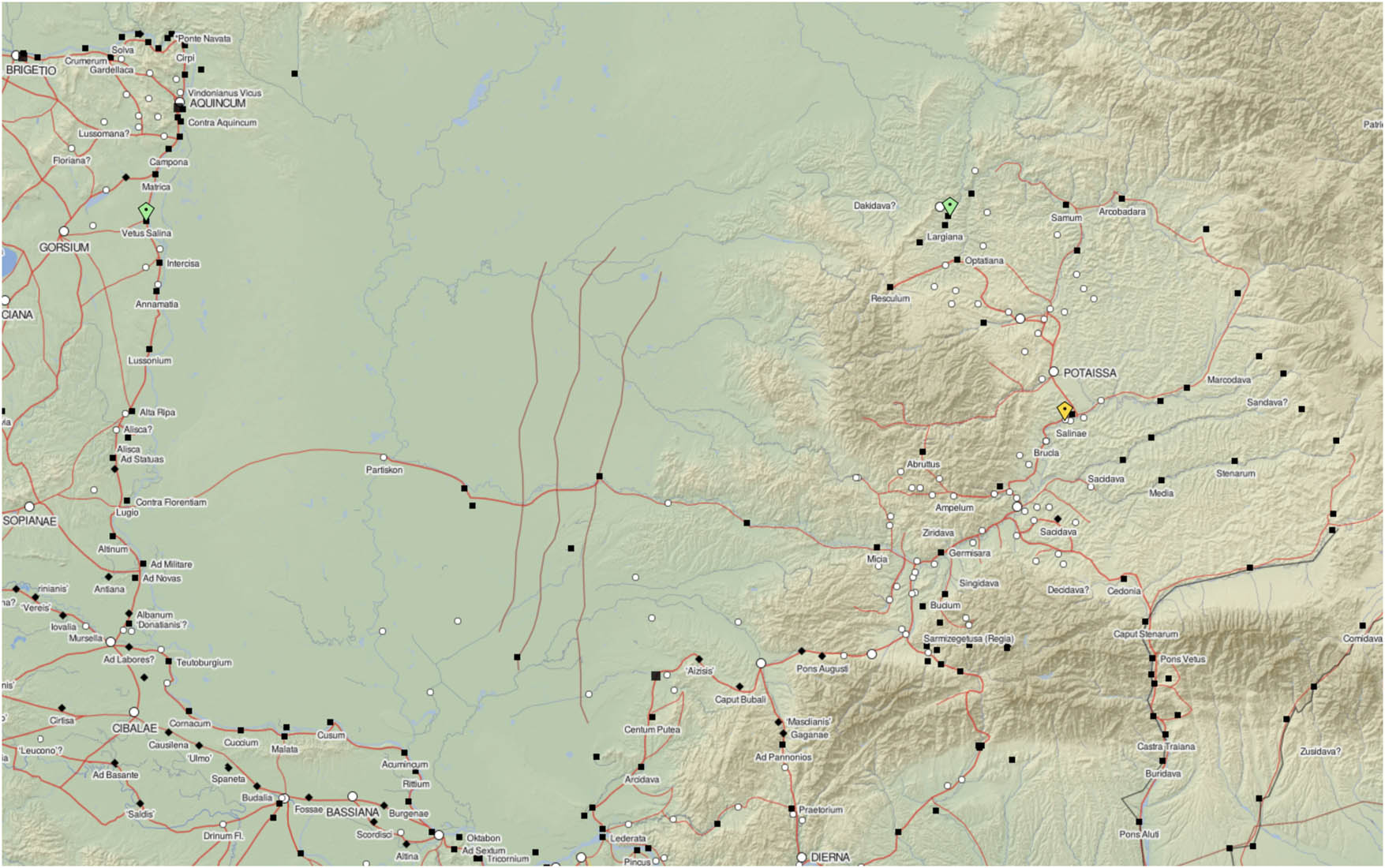

The journey of ala I Batavorum milliaria post-revolt started in Germania Inferior, as suggested by a diploma discovered at Elst (Haalebos, 2000), followed by its transfer to Pannonia Superior, likely in preparation for the Dacian wars, particularly the second one (105–106) (Lörincz, 2001, no. 306, Kat. 510). The location of the ala at the beginning of Hadrian’s reign is unknown, yet probable to be Pannonia until its later deployment to Dacia Superior, at Războieni-Cetate (Figure 1), where it stayed until the abandonment of the province during Aurelian’s reign (271–274). The troop’s earliest firm attestation in Dacia is documented in a diploma from 136/138 (Piso, Benea, 1984, p. 278), but it was probably deployed here earlier, during Hadrian’s fights with the Iazyges (117/118). Numerous stamped tiles indicate the troop’s presence in the Războieni fort (Piso & Varga, 2018). A thriving rural settlement developed around the fort. Its ancient name is unknown, but an inscription from Apamea (Syria) (AE 1993, 1577), dated during the first half of the third century AD, states that Aelius Verecundinus was natus in Dacia ad Vatabos. It is generally believed that “Ad Vatabos” is the settlement of Războieni. However, without additional epigraphic information, this assertion could be challenged, as it may also represent the vicus connected to the Batavian cohort’s fort in Dacia. The fort and its adjacent settlement were “green-field” territories: neither did they overlap a La Tène habitation nor was another troop attested on location before the ala.

Map of Dacia and Pannonia Inferior, with Adony, Războieni, and Romita marked.

Besides the ala, cohors I Batavorum milliaria was also brought on the Dacian limes (Weiss, 2002) and represents one of the three case studies in this article. Its precise location is under discussion, but it is likely to have been Romita in northern Dacia (Dacia Porolissensis) (Figure 1). Along with the cohors III Batavorum, this might be one of the Batavian troops that faced the Caledonians at Mons Graupius (Tacitus, Agricola XXXVI–XXXVIII) in Britannia. During the Dacian wars, it was stationed in Pannonia possibly at Solva (RMD II 86; Spaul, 2000, p. 211). The earliest known record of the troop as part of Dacia’s army is from a military diploma dated to 123 (AE 2011, 179), and it was likely stationed at Romita at that time. The absence of stamped construction material builds up a certain degree of uncertainty regarding the exact location of the troop. Cohors II Britannica milliaria and cohors VI Thracum were also attested at Romita, but we cannot establish an exact succession or system of cohabitation at this time.

From Pannonia Inferior, we are focusing on cohors III Batavorum milliaria equitata, stationed at Vetus Salina (modern-day Adony) (Figure 1). This troop’s itinerary after the Batavian rebellion included Britannia, Raetia, and Pannonia Inferior (Spaul, 2000, p. 213). The earliest attestation of the troop on site, at Adony, is the diploma of 135 (Roxan, 1999, pp. 249–255), but, as in the case of the ala, it was probably deployed here earlier. The first stages of the fort construction here are not fully clear, but apparently, cohors II Batavorum first garrisoned the camp, to be replaced by cohors II Alpinorum, who arrived most probably in 102, the first year of the Dacian wars and until 117–120, when cohors III Batavorum took over and stayed here as a permanent garrison.

These are the short historical outlines of the troops’ and sites’ merged history that have been analysed below from the lens of social practice and pottery consumption to shed light on the extent to which their ceramic goods are confined to the regional supply and whether any vessels may have originated from “home” as a means of preserving a specific facet of the Batavian identity abroad.

4 Războieni

This section analyses the pottery assemblage from the vicus of Războieni, focusing on the methodological considerations and approaches used to identify the pottery consumption patterns. Next, it displays the quantitative and qualitative aspects of the data, discussing their meaning towards a wider understanding of identities associated with Batavian units and the general military environment.

4.1 Methodological Considerations

The ceramic assessment from Războieni incorporates a sample of the assemblage from the vicus adjacent to the fort associated with ala I Batavorum miliaria, focusing on quantifying and qualifying the pottery to illuminate its supply dynamics and fit into the broader economic and social networks in Dacia across the second and third centuries AD. A notable methodological challenge throughout the overall analysis has been the understanding and adaption of contextual data to a comparative standard. While the current Războieni vicus excavations meticulously documented contextual details, their utilisation in this comparative study with older assemblages (such as the Romita bath complex, discussed further below) necessitated adjustment to ensure methodological consistency. This resulted in assigning it a broader date, which in this case has been agreed to span the broader second/third-century chronological framework. The pottery analysis entailed collecting both qualitative and quantitative data, recording qualitative attributes, such as fabric, form class, type, and function, crucial for constructing a comprehensive typology. Quantitatively, the MNR has been employed, informing on issues of supply, production, and social usage, consistently applied across the three case studies presented in this article.

4.2 Quantitative Data

The quantitative data will present the fabrics and forms regarding their range and quantities at Războieni throughout the second and third centuries AD.

4.2.1 Fabrics and Form Classes

The assemblage under analysis from the Războieni vicus consisted of the pottery recovered in the 2021 and 2022 excavation campaigns from a domestic edifice. The main fabric and form classes are displayed in Table 1. The total MNR is 667. The fabric percentages can be found on the last row, entitled “fabric total (MNR%).” Seven broad fabric classes have been identified: oxidised (OXID) with 39.1%, followed by local terra sigillata (TS imit) which amounted to 30.00%. Two types of sigillata imitations have been observed: oxidised, red-coated fabrics aforementioned (TS imit) and the reduced, black-coated version, also known as PSW with 3%. The reduced fabrics (COAR) followed at 22.5%. Other fabrics included finewares-oxidised (OXIDF, 4.3%) and reduced (FINE, 0.2%) – and some mortaria (0.9%) fragments.

Fabric and form class consumption at Războieni vicus

| Forms% | Fabrics% | Form total MNR (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OXID | COAR | TS imit | PSW | OXIDF | FINE | MORT | ||

| Bowl | 27.4 | 10.8 | 56.7 | 5.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 277/41.5 |

| Dish | 39.3 | 10.7 | 40.5 | 5.9 | 3.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 84/12.6 |

| Jar | 18.0 | 82.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100/15.0 |

| Flagon | 91.3 | 5.4 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 93/13.9 |

| Beaker | 3.3 | 0.0 | 6.7 | 3.3 | 83.4 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 30/4.5 |

| Mortarium | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 6/0.9 |

| Dolium | 60.0 | 40.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 10/1.5 |

| Lid | 63.3 | 36.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 49/7.3 |

| Turibulum | 81.8 | 18.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 11/1.7 |

| Other | 28.5 | 0.0 | 57.2 | 0.0 | 14.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7/1.1 |

| Fabric total (MNR%) | 39.1 | 22.5 | 30.0 | 3.0 | 4.3 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 667 MNR |

The percentages show the distribution of each form class across fabrics.

Within these fabrics, the percentages of form classes have also been assessed. The last column in Table 1 entitled “form total MNR (%)” displays the raw MNR of each form class, as well as its percentage out of the total MNR of 667. The range of vessel form classes at Războieni vicus comprises nine distinct categories. Of these, bowls as the most prevalent at 41.5%, followed by jars at 15% and dishes at 12.6%. Tablewares appear to be by far the most consumed categories. Drinking-associated vessels also occupy a prominent place within the community: 13.9% flagons and, on the slightly lower side, 4.5% beakers.

The rest of Table 1 exhibits the percentages of form classes within each fabric. Hence, of the total 277 bowls, 56.7% were made in terra sigillata imitation fabric, 27.4% in oxidised fabrics, 10.8% in coarse fabrics, and 5.1% in PSW. Dishes were also predominantly made in local sigillata (40.5), followed closely by oxidised fabrics (39.3%). On the lower side were the dishes made in PSW (5.9%), oxidised fine (3.6%), and reduced fabrics (10.7%). Conversely, the reduced fabrics seem to have catered more towards jars with 82% of their total 100 MNR being made in greywares and only 18% made in oxidised wares.

These patterns are likely a result of the link between the assemblage chronology and the local production trends in Dacia at the time. The assemblage dates predominantly to the Hadrianic period onwards when assemblages in Dacia were generally dominated by oxidised fabrics. The post-Hadrianic phases in Dacia, the Antonine, and especially the Severan periods, respectively, experienced the maximum economic, social, and urban development of all times in the province (Rusu-Bolindeţ, 2014, p. 159), marked by intensifying building activity, growing production centres and commercial exchanges (Rusu-Bolindeţ, 2016, p. 379). Therefore, the longest phase of Războieni existence was marked by the peak periods of Dacia experiencing maximum urbanisation and economic growth which resulted in production workshops dominated by oxidised local sigillata in particular, as the results seem to indicate.

Additionally, the consumption of tablewares particularly made in local sigillatas is likely linked to the status of Războieni vicus as a local sigillata production centre. This would have encouraged increased consumption of tablewares which were the predominant vessel forms to be made in these fabrics. As its name indicates, this ware tends to imitate morphologically and/or aesthetically the original terra sigillata. Its firing is either oxidised or reduced and the outside has either a red or a black coat, respectively. The increased consumption of these fabrics is most likely an effect of the pottery production development in central and northwestern Dacia in this period. Războieni, along with other eleven sites from Dacia have been identified as official producers of local sigillata products (Rusu-Bolindeţ, 2014, p. 159). Similar products have been encountered in Dacia at Napoca and Buciumi, where the fabrics are described similarly to those seen at Războieni. For example, at Napoca, out of the total number of Dr37 imitations, 74% were the classic Mediterranean oxidised, red-glossed vessels, while the remaining 26% were fired in a reduced environment with a black coat (Rusu-Bolindeţ, 2007, p. 213). Thus, local sigillata production was versatile in terms of fabrics, drawing its inspiration from a wide range of sources and resembling repertoires from other Danubian provinces.

4.3 Qualitative Interpretation

The qualitative interpretation will explore the form types regarding their range at Războieni.

4.3.1 Form Types

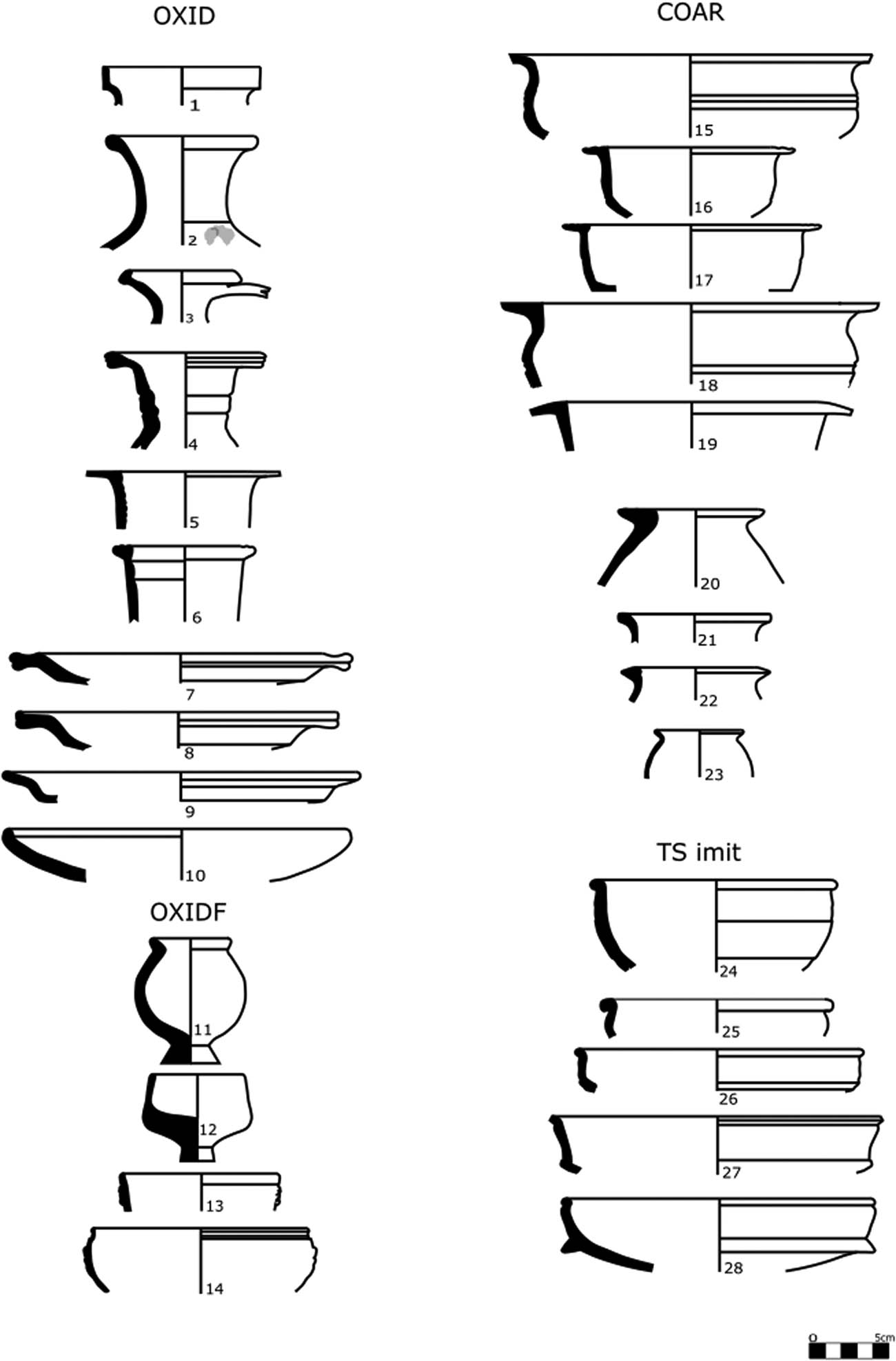

Within the reduced greywares fabric category, flat-rim jars emerged as the predominant form, with 25%, followed by everted-rim jars at 15% (Figure 2: 20–23). In contrast, flagons were mostly part of the oxidised category, comprising approximately 32% of this fabric class total quantity. Among these, reeded rim flagons (Figure 2: 6) accounted for 10%, followed by ring flagons (9%) (Figure 2: 4), continuous body flagons (Figure 2: 2) (8%), collared flagons (Figure 2: 1) (4%), and amphora type flagons (Figure 2: 3) (2%). Tablewares, including bowls and dishes, also featured prominently within the oxidised and reduced categories. The bowls made in reduced fabrics were predominantly flanged (Figure 2: 18–19). These types are more suitable for cooking, as they can be easily held by the elongated rims. Conversely, the bowls made in oxidised fabrics and local sigillatas were predominantly imitations of Dr37 and Dr44 (Figure 2: 24–28). These distinctions are less obvious in regards to dishes. In fact, the straight wall dishes were made in oxidised, reduced, and local sigillata fabrics. Not only do these findings offer comprehensive insights into form preferences and their connection to fabrics and related uses but also reveal material culture trends during the second and third centuries AD at Războieni vicus.

The range of form types from the three case studies.

5 Adony

This section analyses the pottery assemblage from the ancient site and fort Vetus Salina (now Adony), focusing on methodological challenges and approaches to identify pottery patterns. The results, presented in quantitative (fabric and form class figures) and qualitative data (form types), highlight their significance in the regional context.

5.1 Methodology

The assessment of pottery from Adony faced methodological challenges due to the lack of contextual information and the pottery recovery methods at the time. Contextual details are vital for understanding changing consumption patterns and regional dynamics, while comprehensive recovery methods are essential for capturing the accurate quantities of pottery (see Allison, 2013, p. 39). The assessed assemblage from Adony was recovered in the 1950s (Barkóczi, Bónis, 1954), a period marked by focus on individual vessels (“chaine operatoire” and technological aspects) (Lucas, 2002, p. 67), and hence overlooking broader social and cultural dimensions. Nonetheless, the pottery ultimately provides valuable insights into the breadth of vessel types and fabrics, allowing for an overdue quantitative and qualitative study of pottery consumption at Adony.

5.2 Quantitative Data

The quantitative data will present the fabrics and forms regarding their range and quantities at Adony.

5.2.1 Fabrics and Form Classes

The assemblage under analysis from Adony consisted of the pottery recovered in 1950s excavations in the fort known as Vetus Salina. This assemblage was re-assessed in 2023, and despite the lack of any contextual details of the pottery, a quantitative and qualitative study could be undertaken for the first time. The main fabric and form classes are displayed in Table 2. The total MNR is 304. The fabric percentages can be found on the last row, entitled “fabric total (MNR%).” Eight broad fabric classes have been identified. The reduced, coarse fabrics (COAR) were consumed the most, with 44.4%, followed by terra sigillata at 13.8%. Two types of imitations of terra sigillata have been identified, namely the classic oxidised, red-coated fabrics with 8.2% and the reduced, black-coated version, also known as PSW at 9.6%. Other fabrics included oxidised wares (9.6%), oxidised fine wares (3.6%), and some terra nigra fragments (1.3%). However, the latter is likely to be residual from earlier periods.

Fabric and form class consumption at Adony fort

| Forms% | Fabrics% | Form total MNR (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OXID | COAR | TS imit | PSW | OXIDF | TS (terra sigillata) | MORT | TN (terra nigra) | ||

| Bowl | 4.2 | 50.0 | 7.3 | 17.7 | 0.0 | 19.8 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 96/31.6 |

| Dish | 5.0 | 15.0 | 30.0 | 16.7 | 0.0 | 30.0 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 60/19.8 |

| Jar | 97.0 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 66/21.8 |

| Flagon | 80.9 | 19.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 21/6.9 |

| Beaker | 6.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.6 | 73.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 13.4 | 15/4.9 |

| Mortarium | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 29/9.5 |

| Lid | 10.0 | 90.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 10/3.3 |

| Turibulum | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1/0.3 |

| Others | 16.6 | 16.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 66.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6/1.9 |

| Fabric total (MNR%) | 9.6 | 44.4 | 8.2 | 9.6 | 3.6 | 13.8 | 9.5 | 1.3 | 304 MNR |

The percentages show the distribution of each form class across fabrics.

Within these fabrics, the percentages of form classes have also been assessed. The last column in Table 2 entitled “form total MNR (%)” displays the raw MNR of each form class, as well as its percentage out of the total MNR of 304. The range of vessel form classes at Adony comprises eight distinct categories: bowls as the most prevalent at 31.6%, followed by jars at 21.8% and dishes at 19.8%. Tablewares appear to be by far the most consumed categories. Mortaria consumption reaches 9.5%, which is particularly higher than the Războieni case study with only 0.9%. Liquid-associated vessels were also consumed in similar quantities to Războieni: flagons 6.9% and beakers 4.9%.

The fabric patterns shed light on the relationship between import and local production at Adony, placing its fabric consumption between two chronological and social frameworks: generally, across the Roman provinces, the first and early second centuries AD were defined by ostentatious terra sigillata services, while the later second and third centuries AD saw a decline in this ware and instead witnessed the rise of local sigillata production (Rusu-Bolindeţ, 2007, pp. 170–171). For instance, first-century urban-associated cemeteries in northern Gaul showcased pottery geared towards communal consumption (Pitts, 2019, p. 137), whilst in second- and third-century Dacia, sigillata imports dwindled, and its local version became predominant instead (Rusu-Bolindeţ, 2016, p. 384). Adony’s pottery fabric consumption navigates between these two chronological and social contexts, balancing imported and local versions of sigillata and other wares. The case study of Adony is not isolated in the Pannonian province. Other early and mid-Roman forts seem to display similar consumption styles. For example, Baracs (Kovács, 2001) and Ilok (Jelinćić, 2003) seem to have also relied heavily on bowls, dishes, and jars. Within the bowls category at Adony, 50.0% were mainly made in reduced fabrics, followed by terra sigillata (19.8%) and PSW (17.7%). Similarly, dishes were mostly made in PSW, terra sigillata, and its imitation fabrics, but less in reduced greywares. Within the tablewares category overall, terra sigillata and PSW seem to be the most common fabrics.

PSW used the production of terra sigillata as an inspiration for the style, becoming popular as tableware in everyday consumption (Ožanić Roguljić & Jelinčić Vučković, 2022, p. 40). As an example, this phenomenon is to be seen in the southern part of Pannonia (nowadays Croatia) (Ožanić Roguljić & Jelinčić Vučković, 2022). Migrating potters who came along with the military brought new fashions to the regional offer, and eventually, local potters used the information to create a new repertoire, where Roman influence and local traditions merged into a new ware (Schindler Kaudelka, 2022, p. 26), that is the PSW. A similar phenomenon happens in Dacia, which starts with the arrival of the Romans at the beginning of the second century AD with PSW prototypes (Schindler Kaudelka, 2022, p. 26), leading to its imitation in local sigillatas. The military environment at Adony and other sites across Pannonia and even Dacia seems to have displayed similar consumption styles, based on the circulating fashions at the time.

5.3 Qualitative Interpretation

The qualitative interpretation will explore the range of form types at Adony.

5.3.1 Form Types

In the reduced greywares fabric category, prevalent forms included everted rim, triangular or hooked rim, and flat-rimmed jars (Figure 2: 20–23). Tablewares comprised generic straight wall dishes, while bowls exhibited various forms characterised by strong carinations, flanged rims, or reeded rims (Figure 2: 15–19). Regarding bowl form types, they are distinctively divided based on fabrics: similarly to the Războieni situation, the flanged bowls were predominantly made in reduced greywares, while Dr37 imitations were made in the local sigillatas, particularly the PSW (Figure 2: 24–28). This corroborates previous research on PSW and the predominance of Dr37 in this fabric (Leleković, 2018), showing that Adony adheres to the provincial fashions in regards to the circulating form types and fabrics.

Conversely, within the oxidised category, flagons were predominant, with collared (Hofheim-type) flagons dating back to the first century AD, followed by amphora-type and ring-necked flagons peaking towards the end of the first century and diminishing by the second century (Precious in Darling & Precious, 2014, p. 53). The site’s diversity of fine wares, including scale-decorated Lyon ware beakers, suggests its connection with outside provinces and the variety of products supplied (Figure 2: 13). Despite the absence of precise chronological and stratigraphical context at Adony, certain pottery types can be dated to specific periods, indicating the fort’s establishment in the first century AD and the later transition towards local production, including imitations like PSW tablewares.

6 Romita: Seeking for Cohors I Batavorum

6.1 Methodology

The pottery from Romita originates from two distinct assemblages: one recovered from the fort baths in the first half of the 1970s (Gudea, 1973) and re-assessed in 2023 and another from recent 2023 excavations within a tetrapylon-style building in the auxiliary fort. Selecting two assemblages was crucial to ensure a more balanced understanding of pottery consumption at the fort and to provide a comprehensive perspective on its use. Material culture from the baths is often associated with specific activities and social interactions and can sometimes skew the image of everyday life, given the social nature of bathing activities (see Revell, 2007, p. 235). Therefore, including pottery from the tetrapylon-style building helps present a more balanced portrayal of daily consumption patterns at the fort. The methodological approach was tailored to address the challenges posed by both assemblages. The 1970s pottery lacked detailed contextual information, such as stratigraphy, and the analysis had to rely on broader chronological and spatial frameworks. The broader second- to third-century chronology has been applied to both assemblages for consistency and compatibility, ensuring nonetheless a rigorous examination despite the limited contextual data available.

6.2 Quantitative Data

The quantitative data will explore the fabrics and forms regarding their range and their quantities at Romita throughout the second and third centuries AD.

6.2.1 Fabrics and Form Classes

Two assemblages from Romita have been analysed. The first was recovered throughout a series of excavations in the fort baths complex in the 1970s and remained unpublished to this date. A second assemblage has been added to nuance the understanding of pottery consumption at Romita, namely the pottery recovered in the 2023 excavation season, which focused on a tetrapylon building. The first assemblage consisted of 193 MNR, while the second comprised 72 MNR. The main fabric and form classes are displayed in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. The fabric percentages can be found on the last row, entitled “fabric total (MNR%).” From the baths complex, five main fabric classes have been identified: oxidised wares (OXID) at 54.4%, with reduced greywares (COAR) slightly less prevalent at 34.2%. Terra sigillata imitations were also present, with PSW at 1.6% and TS imit at 6.7%. The assemblage also included some fine oxidised fabrics, totalling 3.1%.

Fabric and form class consumption at Romita baths complex

| Forms% | Fabrics% | Form total MNR (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OXID | COAR | TS imit | PSW | OXIDF | ||

| Bowl | 39.5 | 34.2 | 21.1 | 5.3 | 0.0 | 38/19.7 |

| Dish | 55.6 | 22.2 | 22.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 9/4.6 |

| Jar | 29.2 | 70.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 48/24.9 |

| Flagon | 84.2 | 13.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 76/39.4 |

| Beaker | 0.0 | 16.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 83.3 | 6/3.1 |

| Lid | 33.3 | 66.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 9/4.7 |

| Dolium | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2/1.0 |

| Other | 40.0 | 0.0 | 40.0 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 5/2.6 |

| Fabric total (MNR%) | 54.4 | 34.2 | 6.8 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 193 MNR |

The percentages show the distribution of each form class across fabrics.

Fabric and form class consumption at Romita tetrapylon building

| Forms% | Fabrics% | Form total MNR (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OXID | COAR | TS imit | PSW | FINE | ||

| Bowl | 4.8 | 42.9 | 38.1 | 14.3 | 0.0 | 21/29.2 |

| Dish | 30.0 | 30.0 | 10.0 | 30.0 | 0.0 | 10/13.9 |

| Jar | 6.7 | 93.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 15/20.8 |

| Flagon | 90.0 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 20/27.8 |

| Beaker | 0.0 | 50.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 50.0 | 2/2.8 |

| Lid | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1/1.4 |

| Dolium | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2/2.8 |

| Turibulum | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1/1.4 |

| Fabric total (MNR%) | 37.5 | 40.3 | 12.5 | 8.3 | 1.4 | 72 MNR |

The percentages show the distribution of each form class across fabrics.

Table 4 exhibits details on the fabric consumption throughout the 2023 assemblage: reduced greywares (COAR) at 40.3%, followed by oxidised fabrics (OXID) at 37.5%. Terra sigillata imitations were also identified: classic oxidised, red-coated fabrics (TS imit) at 12.5% and reduced, black-coated versions known as PSW at 8.3%. While the overall differences between the two assemblages may not be particularly striking, they reflect variations related to the social function of the spaces, further explored in the form classes analysis below.

Within these fabrics, the percentages of form classes have also been assessed. The last column in Tables 3 and 4 entitled “form total MNR (%)” displays the raw MNR of each form class, as well as its percentage out of the total MNR. The range of vessel form classes at Romita baths comprises eight distinct categories. Of these, high quantities of flagons (39.4%) stood out, followed by jars (24.9%) and bowls (19.7%). Within the 2023 assemblage, bowls were the most prevalent at 29.2%, followed by flagons at 27.8% and dishes at 13.9%. Additionally, both assemblages included less common items, such as lids, beakers, cups, and dolia.

The predominance of flagons in both assemblages suggests a consumption pattern led by this vessel class. The baths assemblage is expected given their social function. However, the significant presence of flagons in the tetrapylon building may reflect a broader flagon-led consumption style at Romita during the second and third centuries AD. Comparable patterns have been observed at other Dacian sites associated with the military: the kiln site from Porolissum (Lăzărescu & Sido, 2018, p. 34) and the legionary fortress associated with legio V Macedonica at Potaissa (Andone-Rotaru & Nedelea, 2018, p. 69; Nedelea, 2020). The presence of the legion at the latter site would have enhanced the pottery production in the area according to the needs of its soldiers (Andone-Rotaru & Nedelea, 2018, p. 69). Thus, Romita could be part of a wider supply and consumption style defined by quantities of pouring vessels as characteristic features of its military environment.

The rest of Tables 3 and 4 exhibits the percentages of form classes within each fabric. Hence, from the fort baths, out of 76 flagons, 84.2% were made in oxidised fabrics. Bowls (39.5%) and dishes (55.6%) were predominantly made in the same fabric class. Conversely, 70.8% of the jars and 66.7% of the lids were made in reduced, greywares. When switching focus to the 2023 assemblage, it appears that only 3.4% of the total bowls were made in oxidised fabrics. Instead, 42.9% were made in reduced greywares, 38.1% in local sigillata, and 14.3% in PSW. Jars and flagons kept similar ratios regarding their fabric diversity. The next section will explore specific form types and their connection to fabrics and use.

6.3 Qualitative Interpretation

The qualitative interpretation will explore the range of form types at Romita.

6.3.1 Form Types

Within the Romita baths assemblage, the main forms within the reduced greyware fabric category included everted (JE) and triangular rim jars (JT), followed by flanged bowls (BF and BFR). Flagons were produced in both reduced and oxidised fabrics as ring flagons (FR), collared flagons (Figure 2: 1), continuous body flagons (Figure 2: 2), and reeded rim flagons (Figure 2: 6). Regarding sigillata imitations, Dr37 and Dr44 (BDR) (Figure 2: 24–28) were the most popular types reproduced in local fabrics, followed by flanged dishes in oxidised wares (Figure 2: 7–9) and flanged bowls mostly in reduced fabrics (Figure 2: 15–19). In the more recent 2023 assemblage from the tetrapylon, a similar pattern is observed, with everted rim jars (JE), triangular rim jars (JT), and flanged bowls (BF) remaining popular within the reduced fabric category. Flagons, particularly FB and FR, dominate the oxidised fabrics, showing less form diversity. Straight wall dishes (DS) persist in the PSW fabric, while the red local sigillata is characterised by two terra sigillata bowl imitations mentioned above. Overall, the 2023 assemblage reflects similar consumption patterns of forms compared to the baths assemblage, albeit with slightly different quantities, indicating a shift in social context.

7 Usage and Consumption: Comparative Remarks

The first mutual element across the three sites was the consumption of terra sigillata imitations. Their presence represents a mutual trait of the second and third centuries in the provinces of Pannonia and Dacia. Jelinćić (2003, p. 85) observed that local production increased locally in Pannonia at Ilok, now including local imitations of sigillata, aside from the original imported products. The black-slipped pottery class (PSW) imitated a wide range of terra sigillata forms, but from AD 130s–140s onwards, the Dr37 bowl became the predominant imitation at several sites in Pannonia, such as Mursa, Cibalae, Aquincum, and Siscia (Leleković, 2018). The pottery assessment from Adony confirms the adherence of its community to these provincial Pannonian trends.

Equally, the high consumption of similar fabric classes in Dacia, particularly the red-coated local sigillata, is most likely an effect of the pottery production development in central and northwestern Dacia in this period (Rusu-Bolindeţ, 2016, p. 379). Războieni, along with other eleven sites from Dacia, have been identified as official producers of local sigillata products (Rusu-Bolindeţ, 2014, p. 159), resulting thus in a high return of such fabrics. Additionally, the arrival of the Roman armies in Dacia at the beginning of the second century AD from the neighbouring province, Pannonia, may have meant the introduction of PSW prototypes (Schindler Kaudelka, 2022, p. 26), which ultimately inspired the local production. The pottery assessment from both Romita and Războieni appears to now confirm indeed the passing of fashions upon military arrivals. In short, the results from Dacia and Pannonia highlight that Adony, Războieni, and Romita were part of a wider supply route that covered neighbouring provinces and served the needs of these sites and their associated communities.

Table 5 focuses further on the vessel form classes from a series of sites in Pannonia and Dacia, dating to early and mid-Roman periods and analysing altogether the three case studies and several of their neighbouring sites for a better local and regional contextualisation. From Pannonia Inferior, assemblages from Baracs (Kovács, 2001) and Ilok (Jelinćić, 2003) have been analysed as they included material from the second and third centuries AD, compatible with Adony. Adony, Baracs, and Ilok are sites of military character and their consumption appears rather similar from the perspective of form preference, opting mainly for jars and bowls. The same pattern seems to follow at both Războieni and Romita, where jars and tablewares (dishes and bowls) are among the most popular forms across the assemblages under analysis. This goes to show that the pottery supply and consumption were interconnected provincially and regionally, resulting in similar trends across Pannonia and Dacia, which could have extended to cooking, eating, and drinking practices. The form class patterns show that pottery consumption in military environments had its own character.

Pottery form class consumption across Dacia and Pannonia during the second and third centuries AD

| Site | Character | MNR | BO (%) | DS (%) | JA (%) | FL (%) | BE (%) | MORT (%) | AMPH (%) | LID (%) | DOL (%) | TUR (%) | OTHER (%) (lamps, cups) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adony | Fort | 304 | 31.6 | 19.8 | 21.8 | 6.9 | 4.9 | 9.5 | — | 3.3 | — | 0.3 | 1.9 |

| Baracs | Fort | 29 | 27.6 | — | 17.2 | 24.1 | 10.3 | 6.9 | — | — | — | — | 13.8 |

| Ilok | Fort | 27 | 14.8 | 33.3 | 7.4 | 3.7 | 14.8 | 3.7 | 22.2 | — | — | — | |

| Războieni | Civilian settlement | 667 | 41.5 | 12.6.0 | 15.0 | 13.9 | 4.5 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 7.3 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.1 |

| Războieni | Fort | 86 | 22.1 | 23.2 | 23.2 | 4.6 | 11.6 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 4.6 | 1.1 | 5.8 | 1.1 |

| Romita | Baths | 193 | 19.7 | 4.6 | 24.9 | 39.4 | 3.1 | 1.0 | — | 4.7 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 2.6 |

| Romita | Tetrapylon building | 72 | 29.2 | 13.9 | 20.8 | 27.8 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 2.8 | 1.4 | 0.0 |

| Porolissum | Civilian settlement | 145 | 36.5 | 1.3 | 30.3 | 19.3 | 1.3 | — | 1.3 | 4.8 | 3.4 | 4.8 | — |

| Potaissa | Fortress | 507 | 39.0 | 7.1 | 41.2 | 10.2 | — | — | — | — | 2.3 | — | |

8 Leftover Batavian Traits?

While the pottery assessment has confirmed the existence of a separate generic military identity of the auxiliary units across the three case studies, it is inevitable to ask whether a separate Batavian identity could be recognised at any of these sites. Initially, it was stated that the transfer of Batavian units to the continent starting with the end of the first century AD marked their “denationalisation” (van Rossum, 2004, p. 120) and the general end of ethnic recruitment (Haalebos, 1999, p. 201; Kraft, 1951, p. 50). However, subsequent studies (e.g. Roymans, 2004; van Driel-Murray, 2009) proved that not only is it likely that some form of ongoing ethnic recruitment may have continued after the transfer of the units to the continent, but also that they kept some sort of ethnic identity spirit, often visible through the epigraphic record. Based on such evidence, an additional assemblage from Războieni was also analysed from this perspective to trace Batavian identity in material culture.

9 Drinking and Beakers

The assemblage discussed in this section consists of the pottery recovered from the 2018 excavation campaign at Războieni fort. Table 5 shows the total MNR of 86, along with the percentages of form classes. From these results, the most striking pattern to emerge is the beaker consumption at Războieni fort. It presents a higher quantity than the Potaissa fortress which amounted to a 507 MNR. Considering the differences in the assemblage quantities, it is striking to see Războieni displaying such a high percentage. Additionally, the nearby civilian settlement from Războieni also displayed a significantly lower quantity of beakers. While these patterns could be a result of the different sizes of the assemblages, nonetheless, the gathered data present reliable quantities to achieve initial patterns which could ultimately be assessed further in future excavations.

The high beaker consumption observed in the fort might be an indication of a specific drinking practice linked to the presence of the Batavian ala at Războieni. The importance of drinking within the Batavian society has been observed on multiple occasions (Pitts, 2019, p. 71; Roymans, 2004, p. 240; T. Vindol. III, 628). Thus, the quantities of beakers may represent a preliminary trait of the Batavian character of the unit; a possible continuation of this behaviour stereotypically associated with these units from the beginning and ongoing even in the late second and third centuries. To further scrutinise this possibility, it is important to assess the form types and see whether the practice alone was kept, or whether it was supplemented with foreign vessel types.

The beakers within the fort displayed varied profiles: curve-rimmed, straight, or oblique profile. The straight/oblique type, likely glass imitations prevalent in military contexts, is part of a category termed “legionary ware” (Greene & Dore, 1977; Swan, 2004). Notably, a biconical beaker from Războieni fort (Figure 3: BEC1) stands out morphologically and aesthetically, resembling examples from northern Gaul rather than typical Dacian assemblages (Crizbasan, 2023, 2024). Its fine, reduced firing and polished surface suggest that it may be an imitation of the P54-57/Holwerda 26 biconical beaker, particularly the P56.1 typological form originating from regions such as Gallia Belgica (Deru, 1996, p. 131; Pitts, 2019, pp. 188–189).

Beakers and face pots typology from Războieni.

However, it is worth noting that while the style resembles the terra nigra beaker, there is a significant chronological gap between its actual popularity “at home” and the Războieni example. Additionally, in terms of quantities of BEC1 alone, the low percentages from Războieni may indicate personal ownership rather than the formal supply of these beakers at this stage. Therefore, the overall beaker consumption, along with this specific type, shows possible remaining links of the unit to northern Gaul, inviting further research in the future. The Batavian auxilia may have maintained a certain awareness of the trendy objects at home, and when they arrived in foreign territories, they attempted to reproduce some of them to maintain a familiar consumption facilitated by familiar objects.

9.1 Facepots

Some of the most spectacular ceramic imported artefacts discovered at Războieni in the civilian settlement are two anthropomorphic vessels (Bounegru & Varga, 2019). Although a separate category of vessels, we included them in the analysis because, methodologically, they are part of the ceramic material and because they speak about cultural and religious habits, thus being important for the understanding of local society.

Pre-Roman production of face pots, with ritualistic functions or simply decorative, existed in all Eastern Mediterranean, in Etruscan and non-Etruscan Italy, as well as in Western Europe. It is generally accepted that one is dealing with two separate traditions, both reverberating in the Western Roman provinces: the Italian face beakers intersected with the larger vessels with face masks from the Lowlands and Germany, used in domestic context and as receptacles for cremated bones alike. In Western Europe, face urns, dating from the Late Bronze Age and Iron Age, have been discovered in the Polish, Scandinavian, and German areas. Apparently, they were frequently used as cremation urns during that period (Braithwaite, 1984, p. 31). The earliest continental Roman face pots have been found on the Rhine and Raetian frontier, exclusively as part of the Rhineland legionary repertoire in the first half of the first century AD (Braithwaite, 1984, p. 100). Their distribution extends to the Upper Danube and into the Benelux Lowlands, which is also the homeland of the Batavian troops; the highest numbers of face pots have been recorded at Cologne, Colchester, and Nijmegen (Braithwaite, 2007, p. 397).

One of the pots discovered at the site of the ala is very fragmentary, with only the right eye of the human figure preserved, while the other is largely intact and has an interesting feature: two phallic representations, one on the back of the vessel and one on the left cheek of the human figure (Figure 3). This feature is particularly important as not only is it inexistent on any other face pots from Dacia, but it also points towards the specific tradition from the Rhineland (Braithwaite, 2007, p. 380), as these phallic decorations were limited almost entirely to this area in the first century AD. Later on, they appear in other European locations under the influence of Gallic and Rhenish troops. Most anthropomorphic vessels come from Cologne, Colchester, and Nijmegen. In Roman times, they continued to be used in burial rituals, but this function became adjacent to everyday use: in domestic altars, where sacrifices were offered daily in the name of a tutelary deity.

The pots are very relevant in the context of evaluating the culture of the settlement we have under scrutiny. Beautiful and “peculiar,” imports such as these reflect cultural roots and at the same time shaped mentalities. The larger of the two vessels has no traces of usage (burning on the inside or the outside) and was discovered in a waste pit, so thrown away by its owners, not destroyed along a building. A hypothesis could be that somebody from the troop or immediate family, coming from the Batavian homeland to Dacia, brought the anthropomorphic urn to use it for funerary purposes. But the artefact broke before being used and it ended up in the waste pit of the house they lived in – for us to find. This shows the existence of another facet of the links between the unit and their homeland which would otherwise be invisible without the material culture.

10 Conclusion

In conclusion, the comprehensive examination of pottery consumption patterns at Războieni, Adony, and Romita provides valuable insights into the dynamics of material culture in Dacia and Pannonia during the early to mid-Roman periods. Although we are fully aware of the limitations of the datasets – stemming from the archaeological excavation methods used (particularly in the case of Adony, where older research methods are involved) or from the nature of the site itself (such as Războieni, where modern disturbances make it challenging to establish a precise decade-by-decade chronology) – we believe we have succeeded in extracting relevant and interesting data from the ceramic datasets. While future discoveries may influence or alter some of our results, especially in quantitative terms, the validity of most of the identified patterns remains certain.

The methodological approaches employed in assessing these pottery assemblages have facilitated a nuanced understanding of supply networks, consumption preferences, and cultural interactions within these frontier regions. The quantitative analyses of fabric and form class distributions reveal distinctive trends at each site, reflecting variations in local production, regional trade networks, and social practices. Despite differences in specific fabric compositions and form preferences, mutual traits emerge, such as the prevalence of terra sigillata imitations and the prominence of functional vessels like tablewares and cookwares across all sites. These shared consumption patterns suggest high connectivity and cultural exchange within the military communities of Dacia and Pannonia.

The qualitative interpretations further highlight the significance of certain vessel types and their cultural associations. While these findings emphasise the similarities in pottery consumption across the three forts, influenced by military presence and regional trade networks, they also suggest potential indicators of Batavian identity within the auxiliary units stationed there. It is well known that Batavian material culture is not distinct in itself – especially not at the level of common pottery – but is instead integrated into the broader production and consumption patterns of the Lower Rhineland and northern Gaul regions. This makes it extremely hard to pinpoint “Batavian artefacts,” but the presence of certain material traits connected with the aforementioned area, in the context of a Batavian troop stationing on site, suggests the presence of soldiers drafted from the Batavian area. For example, the presence of beakers at Războieni hints at a Batavian presence and the preservation of certain habits within the auxiliary unit, as reflected in the material culture. Meanwhile, imported face pots at the same site provide intriguing insights into cultural connections with the Rhineland.

In summary, the qualitative interpretation of pottery may hint at broader cultural connections, revealing facets of ethnic identity among auxiliary units. Overall, this study emphasises the multifaceted nature of pottery consumption in frontier regions and underscores the importance of material culture in understanding identity formation, cultural exchange, and social practices in auxiliary units. By contextualising pottery within broader historical and archaeological frameworks, this research contributes to a more nuanced understanding of the cultural aspects of auxilia.

Acknowledgements

This work is the result of a long-term effort, supported by scholarships and grants from the Gerda Henkel Foundation and, respectively, the Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitisation of Romania, as well as by the National Union Museum of Alba Iulia and the Babeș-Bolyai University of Cluj-Napoca, through enabling the archaeological excavations at Războieni. We are grateful to our colleagues in the archaeological team, Dr. George Bounegru and Dr. Imola Boda, for all their support.

This article was only possible with access to the archaeological material from Adony and Romita. This access was generously granted by the Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum of Budapest and the County Museum of History and Art from Zalău, with the valuable help of our colleagues Dr. Ádám Szabó and Dr. Dan Deac.

-

Funding information: This research was undertaken in the framework of a grant of the Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitization, CNCS – UEFISCDI, project number PN-III-P1-1.1-TE-2021-0165, within PNCDI III, called People, things and identity constructs. The materiality of the Batavians from Roman Dacia.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results, and approved the final version of the manuscript. The contribution of the authors was equal. CC, being a pottery specialist, mainly worked on the primary categorisation of pottery and RV worked more on analysis and contextualisation. Both authors designed the structure of the article and agreed on the conclusions.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Alföldy, G. (1968). Die Hilfstruppen der römischen Provinz Germania Inferior. Rheinland Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

Allison, P. M. (2013). People and spaces in Roman military bases. Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139600248Search in Google Scholar

Andone-Rotaru, M., & Nedelea, L. (2018). The pottery workshops at Potaissa. In V. Rusu-Bolindeţ, C.-A. Roman, M. Gui, I.-A. Iliescu, F.-O. Botiș, S. Mustaţă, & D. Petruţ (Eds.), Atlas of Roan Pottery Workshops from the provinces Dacia and Lower Moesia/Scythia Minor (1st – 7th Centuries AD) (I). Mega Publishing House.Search in Google Scholar

Barkóczi, L., & Bónis, E. (1954). Das frührömische Lager und die Wohnsiedlung von Adony (Vetus Salina). Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, 4, 128–199.Search in Google Scholar

Bounegru, G., & Varga, R. (2019). Two face pots from the vicus of Războieni-Cetate (Alba County). In S. Nemeti, E. Beu-Dachin, I. Nemeti, & D. Dana (Eds.), The Roman Provinces – Mechanisms of Integration (pp. 221–232). Mega Publishing House.Search in Google Scholar

Braithwaite, G. (1984). Romano-British face pots and head pots. Britannia, 12, 99–131.10.2307/526586Search in Google Scholar

Braithwaite, G. (2007). Faces from the past: A study of Roman face pots from Italy and the Western provinces of the Roman Empire. BAR International Series 1651. Archaeopress.10.30861/9781407300856Search in Google Scholar

Crizbasan, C. (2023). Moving communities and changing ceramics: The impact of Batavian auxiliaries across the Roman Empire. (Unpublished Doctoral dissertation). Exeter, Devon: University of Exeter.Search in Google Scholar

Crizbasan, C. (2024). Pottery and social practice: Between home and abroad. Electrum, 31, 83–100. doi: 10.4467/20800909EL.24.007.19157.Search in Google Scholar

Darling, M., & Precious, B. (2014). A corpus of Roman pottery from lincoln. Oxbow.10.2307/j.ctvh1dq62Search in Google Scholar

De Bruin, J. (2019). Border Communities at the Edge of the Roman Empire. Processes of Change in the Civitas Cananefatium. Amsterdam University Press.10.2307/j.ctvkjb403Search in Google Scholar

Deru, X. (1996). La Céramique Belge dans le Nord de la Gaule. Caractérisation, Chronologie, Phénomènes Culturels et économiques. Publications d’histoire de l’art et d’archéologie de l’Université Catholique de Louvain.Search in Google Scholar

Evans, J. (1985). Aspects of later Roman pottery assemblages in Northern England. Investigation of Roman pottery assemblages and supply with emphasis on East Yorkshire industries, and of the potential of neutron activation analysis for fabric characterisation. (Unpublished Doctoral dissertation). Bradford, West Yorkshire, England: University of Bradford.Search in Google Scholar

Evans, J., Price, J., & Wilson, P. R. (1988). All Yorkshire is divided into three parts; social aspects of later Roman pottery distributions in Yorkshire. In J. Price & P. R. Wilson (Eds.), Recent Research in Roman Yorkshire (pp. 323–337). BAR British Series 193. BAR Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Greene, K., & Dore, J. (1977). Roman Pottery Studies in Britain and Beyond. BAR Suppl. Ser, 30. BAR Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Gudea, N. (1973). Castrul roman de la Romita-Certiae. Muzeul Ţǎrii Crişurilor.Search in Google Scholar

Haalebos, J. K. (1999). Nederlanders in Roemenie. Westerheem: Tijdschrift voor de Nederlandse Archeologie, 48(6), 197–210.Search in Google Scholar

Haalebos, J. K. (2000). Traian und die Hilfstruppen am Niederrhein. Ein Militärdiplom des Jahres 98 n. Chr. aus Elst in der Over-Betuwe (Niederlande). Saalburg Jahrbuch, 50, 31–72.Search in Google Scholar

Jelinćić, K. (2003). Rimska keramika iz Iloka. Prilozi Instituta za arheologiju u Zagrebu, 20, 79–88.Search in Google Scholar

Kovács, P. (2001). Annamatia (Baracs) – A Roman auxiliary fort in Pannonia. Acta Antiqua, 41, 55–80.10.1556/aant.41.2001.1-2.7Search in Google Scholar

Kraft, K. (1951). Zur Rekrutierung der Alen und Kohorten an Rhein und Donau. Aedibus A. Francke.Search in Google Scholar

Lăzărescu, V. A., & Sido, K. (2018). The ceramic production centre from Porolissum. In V. Rusu-Bolindeţ, C.-A. Roman, M. Gui, I.-A. Iliescu, F.-O. Botiș, S. Mustaţă, & D. Petruț (Eds.), Atlas of Roman pottery workshops from the provinces Dacia and Lower Moesia/Scythia Minor (1st–7th Centuries AD) (I) (pp. 31–53). Mega Publishing House.Search in Google Scholar

Leleković, T. (2018). How were imitations of samian formed? Internet Archaeology, 50. doi: 10.11141/ia.50.18.Search in Google Scholar

Lörincz, B. (2001). Die römischen Hilfstruppen in Pannonien wahrend der Prinzipatszeit. Poibos.Search in Google Scholar

Lucas, G. (2002). Critical approaches to fieldwork: Contemporary and historical archaeological practice. Routledge.10.4324/9780203132258Search in Google Scholar

Nedelea, L. (2020). Ceramica. In M. Bărbulescu (Ed.), Principia din castrul legionar de la Potaissa (pp. 97–156). Mega.Search in Google Scholar

Ožanić Roguljić, I., & Jelinčić Vučković, K. (2022). Introduction to Pannonian slipped ware in Croatia. Roads and rivers, pots and potters in Pannonia-interactions, analogies and differences (Vol. 17, pp. 31–57). Zbornik instituta za arheologiju.Search in Google Scholar

Piso, I., & Benea, D. (1984). Das Militärdiplom von Drobeta. ZPE, 56, 263–295.Search in Google Scholar

Piso, I., & Varga, R. (2018). Les éstampilles militaires de Razboieni-Cetate. Acta Musei Porolissensis, 41, 263–290.Search in Google Scholar

Pitts, M. (2019). The Roman object revolution: Objectscapes and intra-cultural connectivity in northwest Europe. Amsterdam University Press.10.1017/9789048543878Search in Google Scholar

Revell, L. (2007). Military Bath-houses in Britain – A comment. Britannia, 38, 230–237. doi: 10.3815/000000007784016368.Search in Google Scholar

Roxan, M. (1999). Two complete diplomas of Pannonia Inferior: 19 May 135 and 7 Aug. 143. ZPE, 127, 249–273.Search in Google Scholar

Roymans, N. (2004). Ethnic identity and imperial power: The Batavians in the early Roman Empire. Amsterdam University Press.10.5117/9789053567050Search in Google Scholar

Rusu-Bolindeţ, V. (2007). Ceramica romana de la Napoca. Mega.Search in Google Scholar

Rusu-Bolindeţ, V. (2014). Local Samian Ware Supply in Roman Dacia. Rei Cretariae Romanae Fautorum Acta, 43, 159–174.Search in Google Scholar

Rusu-Bolindeţ, V. (2016). Supply and consumption of terra sigillatasigillata in Roman Dacia during the Severan dynasty. In A. Panaite, R. Cirjan, & C. Capita (Eds.), Moesica et Christiana (pp. 379–409). Editura Istros.Search in Google Scholar

Schindler Kaudelka, I. (2022). Pannonische Glanztonware. A Special case in Central Europe or just a general pattern in Roman Pottery? Roads and Rivers, pots and potteRs in pannonia-inteRactions, analogies and differences (Vo. 17, pp. 5–31). Zbornik instituta za arheologiju.Search in Google Scholar

Spaul, J. E. H. (2000). Cohors: The evidence for and a short history of the auxiliary infantry units of the imperial Roman army. BAR Int. Ser. 841. BAR Publishing.10.30861/9781841710464Search in Google Scholar

Swan, V. G. (2004). The historical significance of “Legionary Wares” in Britain. In F. Vermeulen, K. Sas, & W. Dhaeze (Eds.), Archaeology in Confrontation. Aspects of Roman Military Presence in the Northwest. Studies in honour of Professor Em. Hugo Thoen. Arch. Rep. Ghent Univ. 2 (pp. 259–286). University of Ghent.Search in Google Scholar

van Driel-Murray, C. (2009). Ethnic recruitment and military mobility. In A. Morillo, N. Hanel, & E. Martín (Eds.), Limes XX: XX Congreso Internacional de Estudios sobre la Frontera Romana: León (España), Septiembre, 2006 = XXth International Congress of Roman Frontier Studies (pp. 813–822). Polifemo.Search in Google Scholar

van Rossum, J. A. (2004). The end of the Batavian auxiliaries as ‘national’units’. In L. de Ligt, E. Hemelrijk, & H. W. Singor (Eds.), Roman rule and civic life: Local and regional perspectives (pp. 113–131). Brill.10.1163/9789004401655_008Search in Google Scholar

Webster, G. (1969). Romano-British coarse pottery: A student’s guide (No. 1). Council for British Archaeology.Search in Google Scholar

Weiss, P. (2002). Neue diplome fiir soldaten der exercitus dacicus. ZPE, 141, 241–251.Search in Google Scholar

Willis, S. (2011). Samian ware and society in Roman Britain and beyond. Britannia, 42, 167–242. doi: 10.1017/S0068113X11000602.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Social Organization, Intersections, and Interactions in Bronze Age Sardinia. Reading Settlement Patterns in the Area of Sarrala with the Contribution of Applied Sciences

- Creating World Views: Work-Expenditure Calculations for Funnel Beaker Megalithic Graves and Flint Axe Head Depositions in Northern Germany

- Plant Use and Cereal Cultivation Inferred from Integrated Archaeobotanical Analysis of an Ottoman Age Moat Sequence (Szigetvár, Hungary)

- Salt Production in Central Italy and Social Network Analysis Centrality Measures: An Exploratory Approach

- Archaeometric Study of Iron Age Pottery Production in Central Sicily: A Case of Technological Conservatism

- Dehesilla Cave Rock Paintings (Cádiz, Spain): Analysis and Contextualisation within the Prehistoric Art of the Southern Iberian Peninsula

- Reconciling Contradictory Archaeological Survey Data: A Case Study from Central Crete, Greece

- Pottery from Motion – A Refined Approach to the Large-Scale Documentation of Pottery Using Structure from Motion

- On the Value of Informal Communication in Archaeological Data Work

- The Early Upper Palaeolithic in Cueva del Arco (Murcia, Spain) and Its Contextualisation in the Iberian Mediterranean

- The Capability Approach and Archaeological Interpretation of Transformations: On the Role of Philosophy for Archaeology

- Advanced Ancient Steelmaking Across the Arctic European Landscape

- Military and Ethnic Identity Through Pottery: A Study of Batavian Units in Dacia and Pannonia

- Stations of the Publicum Portorium Illyrici are a Strong Predictor of the Mithraic Presence in the Danubian Provinces: Geographical Analysis of the Distribution of the Roman Cult of Mithras

- Rapid Communications

- Recording, Sharing and Linking Micromorphological Data: A Two-Pillar Database System

- The BIAD Standards: Recommendations for Archaeological Data Publication and Insights From the Big Interdisciplinary Archaeological Database

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Plant Use and Cereal Cultivation Inferred from Integrated Archaeobotanical Analysis of an Ottoman Age Moat Sequence (Szigetvár, Hungary)”

- Special Issue on Microhistory and Archaeology, edited by Juan Antonio Quirós Castillo

- Editorial: Microhistory and Archaeology

- Contribution of the Microhistorical Approach to Landscape and Settlement Archaeology: Some French Examples

- Female Microhistorical Archaeology

- Microhistory, Conjectural Reasoning, and Prehistory: The Treasure of Aliseda (Spain)

- On Traces, Clues, and Fiction: Carlo Ginzburg and the Practice of Archaeology

- Urbanity, Decline, and Regeneration in Later Medieval England: Towards a Posthuman Household Microhistory

- Unveiling Local Power Through Microhistory: A Multidisciplinary Analysis of Early Modern Husbandry Practices in Casaio and Lardeira (Ourense, Spain)

- Microhistory, Archaeological Record, and the Subaltern Debris

- Two Sides of the Same Coin: Microhistory, Micropolitics, and Infrapolitics in Medieval Archaeology

- Special Issue on Can You See Me? Putting the 'Human' Back Into 'Human-Plant' Interaction

- Assessing the Role of Wooden Vessels, Basketry, and Pottery at the Early Neolithic Site of La Draga (Banyoles, Spain)

- Microwear and Plant Residue Analysis in a Multiproxy Approach from Stone Tools of the Middle Holocene of Patagonia (Argentina)

- Crafted Landscapes: The Uggurwala Tree (Ochroma pyramidale) as a Potential Cultural Keystone Species for Gunadule Communities

- Special Issue on Digital Religioscapes: Current Methodologies and Novelties in the Analysis of Sacr(aliz)ed Spaces, edited by Anaïs Lamesa, Asuman Lätzer-Lasar - Part I

- Rock-Cut Monuments at Macedonian Philippi – Taking Image Analysis to the Religioscape

- Seeing Sacred for Centuries: Digitally Modeling Greek Worshipers’ Visualscapes at the Argive Heraion Sanctuary

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Social Organization, Intersections, and Interactions in Bronze Age Sardinia. Reading Settlement Patterns in the Area of Sarrala with the Contribution of Applied Sciences

- Creating World Views: Work-Expenditure Calculations for Funnel Beaker Megalithic Graves and Flint Axe Head Depositions in Northern Germany

- Plant Use and Cereal Cultivation Inferred from Integrated Archaeobotanical Analysis of an Ottoman Age Moat Sequence (Szigetvár, Hungary)

- Salt Production in Central Italy and Social Network Analysis Centrality Measures: An Exploratory Approach

- Archaeometric Study of Iron Age Pottery Production in Central Sicily: A Case of Technological Conservatism

- Dehesilla Cave Rock Paintings (Cádiz, Spain): Analysis and Contextualisation within the Prehistoric Art of the Southern Iberian Peninsula

- Reconciling Contradictory Archaeological Survey Data: A Case Study from Central Crete, Greece

- Pottery from Motion – A Refined Approach to the Large-Scale Documentation of Pottery Using Structure from Motion

- On the Value of Informal Communication in Archaeological Data Work

- The Early Upper Palaeolithic in Cueva del Arco (Murcia, Spain) and Its Contextualisation in the Iberian Mediterranean

- The Capability Approach and Archaeological Interpretation of Transformations: On the Role of Philosophy for Archaeology

- Advanced Ancient Steelmaking Across the Arctic European Landscape

- Military and Ethnic Identity Through Pottery: A Study of Batavian Units in Dacia and Pannonia

- Stations of the Publicum Portorium Illyrici are a Strong Predictor of the Mithraic Presence in the Danubian Provinces: Geographical Analysis of the Distribution of the Roman Cult of Mithras

- Rapid Communications

- Recording, Sharing and Linking Micromorphological Data: A Two-Pillar Database System

- The BIAD Standards: Recommendations for Archaeological Data Publication and Insights From the Big Interdisciplinary Archaeological Database

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Plant Use and Cereal Cultivation Inferred from Integrated Archaeobotanical Analysis of an Ottoman Age Moat Sequence (Szigetvár, Hungary)”

- Special Issue on Microhistory and Archaeology, edited by Juan Antonio Quirós Castillo

- Editorial: Microhistory and Archaeology

- Contribution of the Microhistorical Approach to Landscape and Settlement Archaeology: Some French Examples

- Female Microhistorical Archaeology

- Microhistory, Conjectural Reasoning, and Prehistory: The Treasure of Aliseda (Spain)

- On Traces, Clues, and Fiction: Carlo Ginzburg and the Practice of Archaeology

- Urbanity, Decline, and Regeneration in Later Medieval England: Towards a Posthuman Household Microhistory

- Unveiling Local Power Through Microhistory: A Multidisciplinary Analysis of Early Modern Husbandry Practices in Casaio and Lardeira (Ourense, Spain)

- Microhistory, Archaeological Record, and the Subaltern Debris

- Two Sides of the Same Coin: Microhistory, Micropolitics, and Infrapolitics in Medieval Archaeology

- Special Issue on Can You See Me? Putting the 'Human' Back Into 'Human-Plant' Interaction

- Assessing the Role of Wooden Vessels, Basketry, and Pottery at the Early Neolithic Site of La Draga (Banyoles, Spain)

- Microwear and Plant Residue Analysis in a Multiproxy Approach from Stone Tools of the Middle Holocene of Patagonia (Argentina)

- Crafted Landscapes: The Uggurwala Tree (Ochroma pyramidale) as a Potential Cultural Keystone Species for Gunadule Communities

- Special Issue on Digital Religioscapes: Current Methodologies and Novelties in the Analysis of Sacr(aliz)ed Spaces, edited by Anaïs Lamesa, Asuman Lätzer-Lasar - Part I

- Rock-Cut Monuments at Macedonian Philippi – Taking Image Analysis to the Religioscape

- Seeing Sacred for Centuries: Digitally Modeling Greek Worshipers’ Visualscapes at the Argive Heraion Sanctuary