Abstract

Bound states in the continuum (BICs), i.e. highly-localized modes with energy embedded in the continuum of radiating waves, have provided in the past decade a new paradigm in optics and photonics, especially at the nanoscale, with a range of applications from nanophotonics to optical sensing and laser design. Here, we introduce the idea of a crystal made of BICs, in which an array of BICs is indirectly coupled via a common continuum of states resulting in a tight-binding dispersive energy miniband embedded in the spectrum of radiating waves. The results are illustrated for a chain of optical cavities side-coupled to a coupled-resonator optical waveguide with nonlocal contact points.

1 Introduction

Bound states in the continuum (BICs), originally predicted in nonrelativistic quantum mechanics for certain exotic potentials sustaining localized states with energies embedded in the continuous spectrum of scattered states [1–3], have attracted increasing interest in optics and photonics over the past decade [4–41], providing a new paradigm for unprecedented light localization in nanophotonic structures (for recent reviews see [42–46]). Besides fundamental interest, BICs have found many interesting applications in several areas of photonics, including integrated and nanophotonic circuits [18, 36, 41, 44], laser design [26], [27], [28, 39], optical sensing [22, 34], and nonlinear optics [16, 30, 37]. BICs have found increasing interest also in the cavity and circuit quantum electrodynamics (QED), where spontaneous emission and decoherence can be prevented by the formation of photon-atom BICs [47–55]. Among the different mechanisms underlying the formation of BICs [1], we mention symmetry-protected BICs, BICs via separability, Fano or Fabry–Pèrot BICs, and BICs from inverse engineering. In the majority of cases, a BIC arises from perfect destructive interference of distinct decay channels in the continuum of radiation modes, and thus perturbations rather generally transform a BIC into a long-lived resonance state of the system, so-called quasi-BICs. While the main interest in BICs and quasi-BICs has been focused on their localization features, such as the exceptionally high Q factors achievable using quasi BICs, and to the narrow Fano-like resonances arising from engineering BICs with applications to optical sensing, a less explored question is the coupling of BICs and related transport features. Arrays of BICs with compact support provide an example of a flat band system and have been investigated in some previous works [56–58]. However, in such a geometrical setting the BICs are decoupled and transport in the system via BIC hopping is prevented. Coupling of two BICs via a common continuum results rather generally in the formation of two quasi-BICs, which can sustain long-lived Rabi oscillations [54, 59]. Such results stimulate the search for dispersive bands of BICs, beyond the flat band regime, where transport is impossible.

In this article, we introduce the idea of a crystal of BICs where a dispersive band, formed by the indirect coupling of a chain of BIC states, is embedded in the broader continuum of radiating waves. Contrary to the BIC flat band systems [56–58], in our setting the band formed by the BIC states is dispersive, thus allowing transport in the system when e.g. a gradient field is applied. The concept of BIC crystal and transport via BIC mode hopping is exemplified by considering an array of optical cavities side-coupled to a coupled-resonator optical waveguide (CROW) [60, 61] with nonlocal contact points.

2 Dispersive bands formed by indirectly-coupled BICs: effective non-Hermitian description

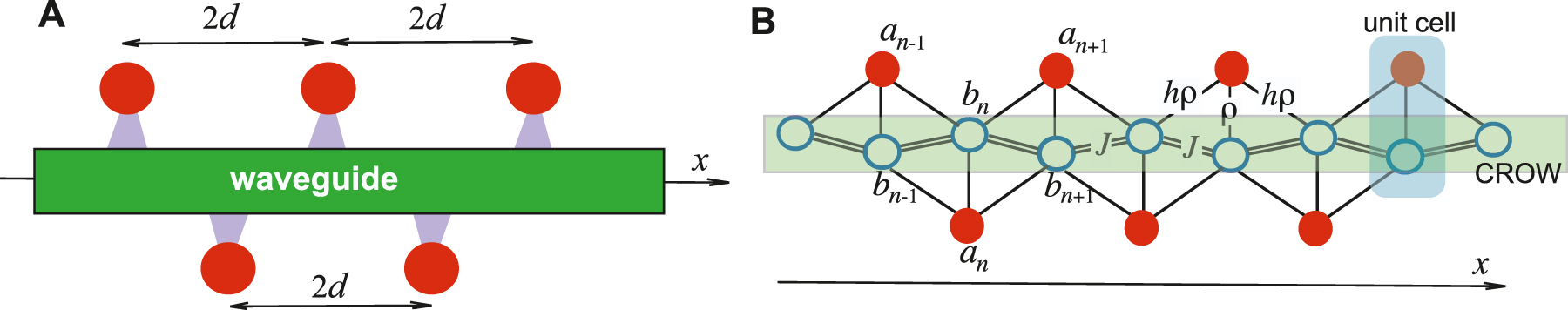

To highlight the idea of a crystal of BICs, let us consider a rather general model describing N discrete states coupled to a common one-dimensional (1D) continuum of radiating waves into which they can decay. In photonics, this system can describe, for example, an array of N optical cavities equally spaced by a distance d, with the same resonance frequency ω 0, side-coupled by evanescent field to a waveguide, as schematically shown in Figure 1A. A possible photonic platform, suggested in pioneering work on photonic BICs, could be a 1D photonic crystal waveguide on a square lattice of dielectric rods with additional lateral defects, which displays BICs with low radiation losses [5]. Our main focus is to consider a crystal of side-coupled resonators in the N → ∞ limit. We note that in the cavity or circuit QED context, the system of Figure 1A can describe as well an array of two-level quantum emitters with transition frequency ω 0, equally-spaced by a distance d and nonlocally coupled by an electric-dipole transition to the photon field of waveguide modes. Such circuit QED model could be implemented, for example, using arrays of artificial atoms side-coupled to a quantum waveguide realized with superconducting quantum circuits [52]. In the following, we will explicitly refer to the photonic system model and will use the terminology of integrated photonics.

(A) Schematic of a waveguide with N side-coupled optical resonators or cavities (N = 5 in the figure). Adjacent cavities are spaced by a distance d. (B) A CROW in a zig-zag geometry (blue rings) with side-coupled optical cavities (red circles). The solid bonds show the couplings of the various cavities/resonators. Note that each cavity is coupled to three resonators of the CROW with coupling constants ρ and hρ. The distance between adjacent cavities is d = 1 (in units of the CROW period). The overall cavities-CROW system can be viewed as a bipartite lattice with two sites in the unit cell (sublattice A formed by the side cavities and the sublattice B formed by the resonators of the CROW). The weak-coupling limit corresponds to ρ ≪ J, where J is the coupling rate of adjacent resonators in the CROW.

In the second-quantization framework, the full Hamiltonian of the photon field is described by Friedrichs–Lee (or Fano-Anderson) Hamiltonian (see for instance [62, 63])

where

is the Hamiltonian of photon field in the N uncoupled cavities with the same resonance frequency ω 0 (n = 1, 2, …, N),

in the Hamiltonian describing the radiating field in the 1D waveguide, with dispersion relation ω(k) parametrized by the wave number k, and

describes the resonator-waveguide coupling with spectral coupling functions G

n

(k). In the above equations,

is satisfied for k = ±k 0, with ω(k) ≃ |k|v g for k ∼ ±k 0, where v g is the group velocity of the left- and right-propagating modes of the waveguide at the frequency ω 0. Since the resonators are equally-spaced by a distance d along the waveguide x-axis and equally coupled to the waveguide, the spectral coupling functions G n (k) satisfy the condition [6]

with G 0(k) → 0 as k → ±∞. Let us assume that the system is initially excited by a single photon or by a classical state of light in the resonators solely. In this case, we can restrict the analysis to the single excitation sector of Fock space [53, 64] by letting,

for the state vector of the photon field, where the amplitude probabilities a n (t) and c(k, t) satisfy the classical (c-number) coupled-mode equations

with c(k, 0) = 0. Assuming a weak resonator-waveguide coupling and neglecting retardation effects, using standard methods one can eliminate the waveguide degrees of freedom c(k, t) from the dynamics, resulting in an effective non-Hermitian coupling among the resonators mediated by the continuum of waveguide modes [5, 6, 46, 62, 63, 65], [66], [67]. The resulting approximate non-Hermitian dynamics of the resonator field amplitudes a n read

where the elements of the non-Hermitian matrix H are given by (technical details are presented in Section 1 of the Supplementary Material)

Note that, from Eqs. (6) and (11), it follows that H n,l is a function of (n − l) solely, i.e.

A few general properties of the coefficients H n are discussed in Section 1 of the Supplementary Material. In particular, for a symmetric coupling of the resonator mode with forward and backward propagating modes of the waveguide, i.e. for G 0(−k) = G 0(k), one has H −n = H n . Moreover, H n vanishes as n → ∞, if and only if the condition

is satisfied. As shown in the Supplementary Material, this condition corresponds to the vanishing of the imaginary part of H 0, i.e. to the existence of a BIC when a single resonator (rather than a chain of resonators) is coupled to the waveguide.

In a system with discrete translation invariance, i.e. in the N → ∞ limit, Eq. (10) indicates that the indirectly-coupled resonators behave like a tight-binding crystal with long range hopping, sustaining Bloch-like supermodes of the form

with the energy dispersion relation given by

where −π/d ≤ q < π/d is the Bloch wave number. The main result is that, provided that condition (13) is met, the series on the right hand side of Eq. (15) converges and the energy spectrum, described by the dispersion curve Ω(q), is entirely real and given by (see Section 2 of the Supplementary Material for technical details)

Clearly, the dispersion curve Ω(q) is embedded in the broad spectrum ω(k) of the scattering states of waveguides. A trivial case is when the BIC modes are compact states and decoupled one from another (H n = 0 for n ≠ 0), which occurs for enough wide spacing d: in this case, one obtains a flatband BIC crystal, i.e. Ω(q) = H 0 independent of q. Examples of crystals sustaining a flat band of BIC states have been discussed in the context of flat band systems (see e.g. [56–58]). However, the present asymptotic analyst shows that an entirely real energy dispersion relation is possible beyond the flat band case when the BIC states are indirectly coupled via the continuum of the waveguide modes so that excitation can be transferred among the various indirectly coupled BICs through the embedded dispersive band Ω(q).

3 An example of a BIC lattice: optical cavities side-coupled to a CROW

3.1 Model and band structure

To illustrate the existence and properties of a BIC crystal with a dispersive band, we consider a simple and exactly-solvable tight-binding model, shown in Figure 1B. It consists of an array of optical cavities side-coupled with three contact points to a CROW in a zig-zag geometry, with spacing d = 1 between one cavity and the next one (in units of the CROW period). We assume negligible radiation losses from the cavities to the surrounding space, so that decay mainly arises from evanescent mode coupling to the CROW. This system could be physically implemented in a two-dimensional photonic crystal platform, where a periodic sequence of defect modes is side-coupled to a 1D photonic crystal waveguide, in a configuration similar to the case of the two off-channel defects suggested in Ref. [5]. In such a configuration, the side-coupled off-channel cavities are hidden deeply in the photonic crystal so that radiation losses from the cavities are strongly suppressed. For the case of N = 2 cavities, this model has been recently studied in Ref. [59], showing that weakly damped Rabi flopping can be observed owing to the indirect coupling of two quasi-BIC modes. Here we consider, conversely, the N → ∞ limit so that the system displays discrete translation invariance and we can apply Bloch band theory. We indicate by ω 0 the frequency detuning between the optical modes in the cavities and resonators, by J the coupling constant between adjacent resonators in the CROW, and by ρ and hρ the coupling of each optical cavity with the three closest resonators of the CROW (Figure 1B). The dimensionless parameter h measures the relative strength of nearest and next-to-the-nearest mode coupling of the optical cavity with the CROW resonators. We typically assume ρ < J, with ρ ≪ J in the weak coupling regime. Clearly, in the N → ∞ limit, the tight-binding Hamiltonian in Wannier basis can be readily solved by Bloch theorem and the energy spectrum consists of two bands since the entire system can be viewed as a bipartite lattice composed by two sublattices (Figure 1B). This analysis will be discussed below. Before, we wish to illustrate how the existence of the BIC crystal can be predicted from the effective non-Hermitian description outlined in the previous section. As shown in Section3 of the Supplementary Material, the Hamiltonian of the photon field for the model of Figure 1B can be cast in the general Friedrichs–Lee form of Eqs. (1)–(4), where the continuum of radiation modes in the waveguide are the Bloch modes of the CROW with the dispersion relation

[k varies in the range (−π, π)], while the spectral coupling function G 0(k) is given by

The BIC condition (13) is satisfied provided that the frequency detuning ω 0 is tuned to the value

so as G(±k 0) = 0. Note that, to satisfy Eq. (19), we necessarily require h > 1/2.

The dispersion curve of the BIC crystal is obtained from Eq. (16), where the sum on the right hand side of the equation is limited to the n = 0 term solely (this is because k varies only in the range (−π, π), rather than from −∞ to ∞ as in a waveguide). One obtains

which shows a singularity at J cos q = ω 0/2. The physical origin of such a singularity and failure of the asymptotic method will be discussed below through the exact analysis. However, the curve Ω(q) is regularized under the BIC condition ω 0 = −J/h [Eq. (19)], yielding

Note that the dispersion curve is sinusoidal, corresponding to the vanishing of H n for n ≠ 0, ±1.

Let us then turn to the exact analysis of modes and spectrum of the lattice shown in Figure 1B, which can be readily obtained by standard Bloch analysis in the Wannier basis of the CROW modes. In fact, indicating by a n and b n the field amplitudes in the nth side-coupled optical cavity and in the nth resonator of the CROW, the classical coupled-mode equations for a n and b n read

The Bloch eigenstates (supermodes) of the lattice are of the form

where the dispersion relation Ω(q) is obtained as the root of the determinantal equation

Note that Eq. (25) is of second order in Ω(q), indicating the existence of two lattice bands, according to the bipartite nature of the lattice which comprises the two sublattices A (optical cavities) and B (resonators of the CROW). The dispersion curves of the two bands read

Rather generally the energy spectrum is gapped with an upper (Ω+) and lower (Ω−) band (Figure 2A). However, when the resonance frequency detuning ω 0 is tuned to the value ω 0 = −J/h, corresponding to the BIC condition (19), the spectrum is gapless and the two bands cross, leading to the formation of a narrow band Ω n (q), embedded in a wider band Ω w (q), as shown in Figure 2B. Basically, Ω n (q) = Ω−(q) for −k 0 ≤ q ≤ k 0, and Ω n (q) = Ω+(q) for |q| > k 0. Likewise, Ω w (q) = Ω+(q) for −k 0 ≤ q ≤ k 0, and Ω w (q) = Ω−(q) for |q| > k 0. Remarkably, the narrow and wider bands have the same dispersion relation but with different amplitudes Δ w.n , namely

with

![Figure 2:

(A and B) Band diagram of the CROW structure with side-coupled optical cavities of Figure 1B for parameter values ρ/J = 0.3, h = 0.8 and for (A) ω

0/J = −0.75, (B) ω

0/J = −1/h = −1.25. The dashed red curves in (A and B) show the band dispersion curve Ω(q) predicted by the asymptotic analysis [Eq. (20)]. In (A), the BIC condition ω

0 = −J/h is not satisfied, the spectrum is gapped with noncrossing upper (Ω+) and lower (Ω−) bands. Note that Ω(q) shows a singularity at the Bloch wave numbers q = ±k

0, where k

0 satisfies the resonance condition ω

0 = 2J cos k

0. In (B), the BIC condition ω

0 = −J/h is satisfied and the spectrum is gapless, resulting in the formation of narrowband Ω

n

(the BIC band) embedded in a wider band Ω

w

. In this case, the predicted curve Ω(q) is almost overlapped with the exact curve Ω

n

of the narrow band. (C) Band diagram in the strong coupling regime (ρ/J = 1.1, h = 0.8) with ω

0/J = −1/h. A narrower band Ω

n

embedded in a wider band Ω

w

is still observed in the exact model (solid curves). However, the asymptotic analysis [Eq. (21), dashed curve] fails to provide the accurate shape of the narrow band.](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2021-0260/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2021-0260_fig_002.jpg)

(A and B) Band diagram of the CROW structure with side-coupled optical cavities of Figure 1B for parameter values ρ/J = 0.3, h = 0.8 and for (A) ω 0/J = −0.75, (B) ω 0/J = −1/h = −1.25. The dashed red curves in (A and B) show the band dispersion curve Ω(q) predicted by the asymptotic analysis [Eq. (20)]. In (A), the BIC condition ω 0 = −J/h is not satisfied, the spectrum is gapped with noncrossing upper (Ω+) and lower (Ω−) bands. Note that Ω(q) shows a singularity at the Bloch wave numbers q = ±k 0, where k 0 satisfies the resonance condition ω 0 = 2J cos k 0. In (B), the BIC condition ω 0 = −J/h is satisfied and the spectrum is gapless, resulting in the formation of narrowband Ω n (the BIC band) embedded in a wider band Ω w . In this case, the predicted curve Ω(q) is almost overlapped with the exact curve Ω n of the narrow band. (C) Band diagram in the strong coupling regime (ρ/J = 1.1, h = 0.8) with ω 0/J = −1/h. A narrower band Ω n embedded in a wider band Ω w is still observed in the exact model (solid curves). However, the asymptotic analysis [Eq. (21), dashed curve] fails to provide the accurate shape of the narrow band.

Note that, in the weak coupling limit ρ ≪ J one has Δ n ≃ −hρ 2/J, so that the dispersion relation Ω n (q) of the embedded narrow band exactly reduces to Eq. (21), predicted by the asymptotic analysis. The corresponding Bloch eigenstates [Eq. (24)] have the largest excitation in the sublattice a n , i.e. in the optical cavities, with a ratio B/A = Δ n /ρ ∼ O(ρ/J).

It is worth briefly discussing the failure of the asymptotic analysis when the BIC condition ω 0 = −J/h is not met and the appearance of a singularity in the energy band Ω(q), given by Eq. (20), at the Bloch wave number q = ±k 0 with J cos k 0 = ω 0/2. To this aim, let us consider the exact band structure of the system, given by Eq. (26), in the ρ/J → 0 limit. Let us write the bands Ω± in the equivalent form

In the limit ρ/J → 0 and for ω 0 ≠ −J/h, a narrow gap, corresponding to an avoided crossing of the two branches Ω±(q), occurs at the Bloch wave number q = ±k 0 such that J cos k 0 = ω 0/2. For q far enough from ±k 0 such that |2J cos q − ω 0| ≫ ρ, we can perform a Taylor expansion of the square root on the right hand side of Eq. (29), yielding for the mixed branch Ω n (q) the following expression

which is precisely the dispersion curve Eq. (20) predicted by the asymptotic analysis. Hence, the unphysical singularity found in Eq. (20) at the Bloch wave numbers q = ±k 0 is related to the formation of a physical band gap, which cannot be described by the asymptotic analysis.

Finally, let us mention that for the exactly solvable model given by Eqs. (22) and (23) a narrower dispersive band Ω n embedded into a wider band Ω w is observed even in the strong coupling regime (ρ comparable or even larger than J), provided that the gapless condition ω 0 = −J/h is met. An example of the exact band structure (Ω n and Ω w ) in the strong coupling regime is shown in Figure 2C by solid curves. Clearly, in this regime, the asymptotic analysis, valid in the weak coupling limit, does not provide anymore an accurate description of the embedded band Ω n , with the dispersion curve Ω(x) predicted by Eq. (21) (dashed curve in Figure 2C) substantially deviating from the exact band dispersion curve Ω n . Also, in the strong coupling regime, a single BIC mode does not exist anymore under condition (19), and an additional shift from the gapless value given by Eq. (19) would be required to have a single BIC: hence in the strong coupling regime, the nature of the embedded band Ω n cannot be readily linked to indirectly coupled isolated BIC modes of the structure.

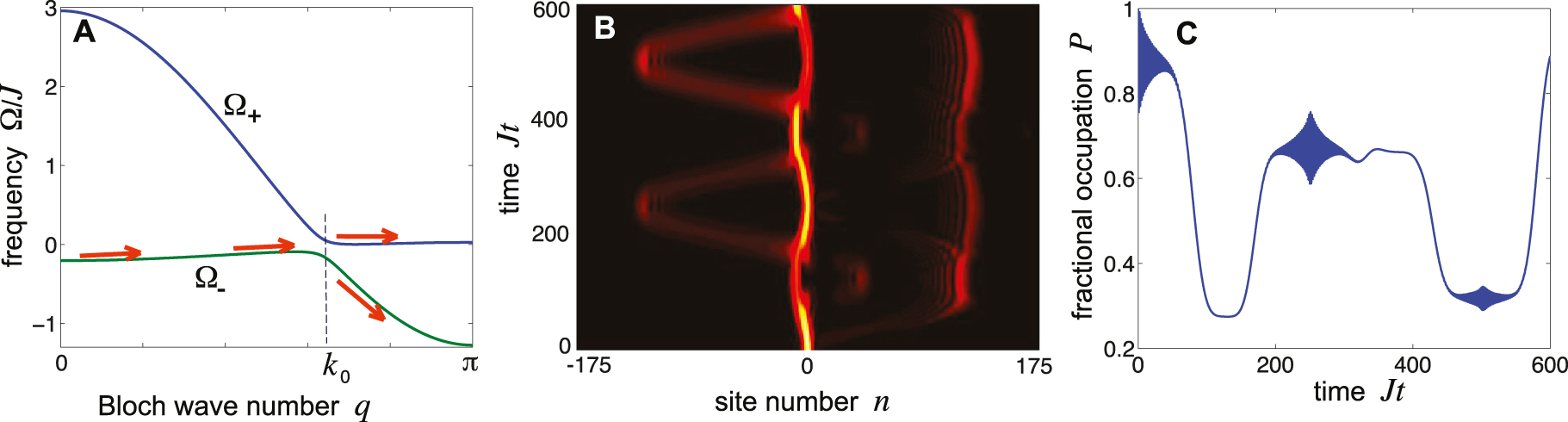

3.2 Transport dynamics: BOs in the BIC crystal

In a flat band system realized by a chain of uncoupled BICs, transport via mode hopping in the flat band is clearly prevented. Conversely, in a BIC crystal with a dispersive band transport is possible. To illustrate the concept, let us introduce a linear refractive index gradient along the x-axis of the system, shown in Figure 1B. In a single-band crystal, such a gradient is known to induce a periodic light dynamics which is the analogous of BOs of electrons in crystalline potentials (see for instance [68–75]). The coupled-mode equations ((22) and (23)) are modified as follows

where F is a small frequency detuning gradient induced by the index gradient. As an initial condition, we assume a Gaussian wave packet excitation of the optical cavities (sublattice A) with vanishing momentum, i.e. a n (0) = exp(−n/2 w 2 + iq 0 n), b n (0) = 1 with q 0 = 0 and w ≫ 1. The observed dynamical behavior largely depends on whether the system is gapless (ω 0 = −J/h) or gapped (ω 0 ≠ −J/h).

In the gapless case, i.e. when we have a BIC crystal, in the weak coupling limit ρ ≪ J the initial wave packet excites the narrow portion of the Ω n (q) narrow band with wave number q ∼ q 0 = 0. In the semiclassical description of the wave packet dynamics, the external force F induces a drift q(t) = q 0 + Ft of the wave number (momentum) in Bloch space. Since the spectrum is gapless, at the crossing points q = ±k 0, the excitation fully remains in the BIC crystal narrow band Ω n , without excitation of the wider embedding band Ω w , i.e. of sites of sublattice B. As a result, a periodic dynamics of the wave packet with a BO period T B = 2π/F is observed, with most of the excitation remaining trapped in the optical cavities, as measured by the evolution of the fractional optical power

This is illustrated, as an example, in Figure 3.

![Figure 3:

Bloch oscillation dynamics in the BIC crystal with the same parameter values as in Figure 2B and for a gradient F/J = 0.025. The initial excitation condition is a Gaussian wave packet a

n

(0) = exp[−(n/w)2 + iq

0

n] with initial wave number q

0 = 0 and width w = 3. The external gradient F induces a drift of the Bloch wave number according to q(t) = q

0 + Ft, which is schematically depicted in (A) by solid arrows. When the wave number q reaches the crossing point q = k

0, the wideband Ω

w

is not excited and the entire wave packet undergoes a periodic motion, remaining trapped in the narrow (BIC) band Ω

n

, with a period T

B = 2π/F ≃ 251.3/J. This is shown in panel (B), which depicts on a pseudo color map the temporal evolution of the amplitudes |a

n

(t)| in the various cavities, labeled by the site number n. The temporal evolution of the fractional optical power P(t) trapped in the cavities, defined by Eq. (33), is shown in panel (C). Note that during the entire Bloch oscillation (BO) period, the optical power remains mostly trapped in the optical cavities, with small excitation of the resonators in the CROW.](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2021-0260/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2021-0260_fig_003.jpg)

Bloch oscillation dynamics in the BIC crystal with the same parameter values as in Figure 2B and for a gradient F/J = 0.025. The initial excitation condition is a Gaussian wave packet a n (0) = exp[−(n/w)2 + iq 0 n] with initial wave number q 0 = 0 and width w = 3. The external gradient F induces a drift of the Bloch wave number according to q(t) = q 0 + Ft, which is schematically depicted in (A) by solid arrows. When the wave number q reaches the crossing point q = k 0, the wideband Ω w is not excited and the entire wave packet undergoes a periodic motion, remaining trapped in the narrow (BIC) band Ω n , with a period T B = 2π/F ≃ 251.3/J. This is shown in panel (B), which depicts on a pseudo color map the temporal evolution of the amplitudes |a n (t)| in the various cavities, labeled by the site number n. The temporal evolution of the fractional optical power P(t) trapped in the cavities, defined by Eq. (33), is shown in panel (C). Note that during the entire Bloch oscillation (BO) period, the optical power remains mostly trapped in the optical cavities, with small excitation of the resonators in the CROW.

Conversely, when the condition ω 0 = −J/h is not satisfied, i.e. when the two bands of the bipartite lattice undergo an avoided crossing at q = ±k 0, we do not have a BIC crystal anymore, i.e. a narrow band embedded in a wider one is not formed, rather we have two distinct bands Ω±(q) separated by a gap. The initial wave packet mostly excites the Bloch modes of the lower band Ω−(q) with wave number near q ∼ q 0 = 0. When the drifting Bloch wave number q(t) = q 0 + Ft reaches the avoided crossing points q = ±k 0, a splitting of excitation between the two distinct bands Ω± is observed, leading to a more complex and generally aperiodic two-band dynamics (so-called Bloch–Zener oscillations [76–80]). This behavior is illustrated in Figure 4. Note that, contrary to the gapless case of Figure 3, at the avoided-crossing points a rather abrupt change of the fractional optical power P(t) trapped in the optical cavities is observed, i.e. excitation does not remain trapped in the optical cavities anymore, but it is periodically transferred into the resonators of the CROW.

Same as Figure 3, but for parameter values as in Figure 2A and for a gradient F/J = 0.025. Note that, when the wave number q(t) of the Gaussian wave packet reaches the crossing point q = k 0, excitation is split between the upper and lower bands Ω± (solid arrows in panel (A)), and the entire wave packet undergoes an irregular motion, dubbed Bloch–Zener oscillations (panel (B)), with an aperiodic exchange of optical power between the two bands as q(t) crosses the two-gap points q = ±k 0. Correspondingly, a large fraction of optical power can be transferred during the dynamics from the optical cavities (sublattice A) to the resonators of the CROW (sublattice B), as shown in panel (C).

4 Conclusion

In this work, we have introduced the concept of a BIC crystal, i.e. a narrow energy band of Bloch modes (rather than one or more discrete energy levels) embedded in a wide spectrum of radiation modes. By means of an asymptotic analysis based on a non-Hermitian effective model, it has been shown that rather generally a BIC crystal arises when single BIC modes are indirectly coupled via a common continuum. To support the predictions of the asymptotic analysis, we presented an exactly-solvable model, consisting of an array of optical cavities side-coupled nonlocally to a CROW. The narrow embedded energy band formed by the indirectly coupled BIC modes enables transport in the crystal, contrary to the case of a flat band formed by uncoupled BIC modes. Our results shed new light in the area of BIC states, suggesting the fresh concept of the embedded band or BIC crystal, which could stimulate interest in photonics and in other areas of physics, such as in cavity or circuit QED.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the Spanish State Research Agency through the Severo Ochoa and Maria de Maeztu Program for Centers and Units of Excellence in R & D (MDM-2017-0711).

-

Author contribution: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

[1] J. von Neumann and E. P. Wigner, “On some peculiar discrete eigenvalues,” Z. Phys., vol. 30, pp. 465–467, 1929.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] L. Fonda, “Bound states embedded in the continuum and the formal theory of scattering,” Ann. Phys., vol. 22, pp. 123–132, 1963. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-4916(63)90299-9.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] F. H. Stillinger and D. R. Herrick, “Bound states in the continuum,” Phys. Rev. A: At., Mol., Opt. Phys., vol. 11, pp. 446–454, 1975. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.11.446.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] D. C. Marinica, A. G. Borisov, and S. V. Shabanov, “Bound states in the continuum in photonics,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 100, p. 183902, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.100.183902.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] E. N. Bulgakov and A. F. Sadreev, “Bound states in the continuum in photonic waveguides inspired by defects,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 78, p. 075105, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.78.075105.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] S. Longhi, “Transfer of light waves in optical waveguides via a continuum,” Phys. Rev. A: At., Mol., Opt. Phys., vol. 78, p. 013815, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.78.013815.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] F. Dreisow, A. Szameit, M. Heinrich, et al.., “Adiabatic transfer of light via a continuum in optical waveguides,” Opt. Lett., vol. 34, pp. 2405–2407, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.34.002405.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Y. Plotnik, O. Peleg, F. Dreisow, et al.., “Experimental observation of optical bound states in the continuum,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 107, p. 183901, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.107.183901.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] M. I. Molina, A. E. Miroshnichenko, and Y. S. Kivshar, “Surface bound states in the continuum,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 108, p. 070401, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.070401.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] C. W. Hsu, B. Zhen, J. Lee, et al.., “Observation of trapped light within the radiation continuum,” Nature, vol. 499, pp. 188–191, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12289.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] S. Weimann, Y. Xu, R. Keil, et al.., “Compact surface Fano states embedded in the continuum of waveguide arrays,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 111, p. 240403, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.111.240403.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] G. Corrielli, G. Della Valle, A. Crespi, R. Osellame, and S. Longhi, “Observation of surface states with algebraic localization,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 111, p. 220403, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.111.220403.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Y. Yang, C. Peng, Y. Liang, Z. Li, and S. Noda, “Analytical perspective for bound states in the continuum in photonic crystal slabs,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 113, p. 037401, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.037401.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] S. Longhi and G. Della Valle, “Floquet bound states in the continuum,” Sci. Rep., vol. 3, p. 2219, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02219.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] E. N. Bulgakov and A. F. Sadreev, “Bloch bound states in the radiation continuum in a periodic array of dielectric rods,” Phys. Rev. A: At., Mol., Opt. Phys., vol. 90, p. 053801, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.90.053801.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] E. N. Bulgakov and A. F. Sadreev, “Robust bound state in the continuum in a nonlinear microcavity embedded in a photonic crystal waveguide,” Opt. Lett., vol. 39, pp. 5212–5215, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.39.005212.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] B. Zhen, C. W. Hsu, L. Lu, A. D. Stone, and M. Soljacic, “Topological nature of optical bound states in the continuum,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 113, p. 257401, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.113.257401.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] F. Monticone and A. Alù, “Embedded photonic eigenvalues in 3D nanostructures,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 112, p. 213903, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.112.213903.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] S. Longhi, “Bound states in the continuum in PT-symmetric optical lattices,” Opt. Lett., vol. 39, pp. 1697–1699, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.39.001697.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] R. Gansch, S. Kalchmair, P. Genevet, et al.., “Measurement of bound states in the continuum by a detector embedded in a photonic crystal,” Light Sci. Appl., vol. 5, p. e16147, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2016.147.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] N. Rivera, C. W. Hsu, B. Zhen, H. Buljan, J. D. Joannopoulos, and M. Soljacic, “Controlling directionality and dimensionality of radiation by perturbing separable bound states in the continuum,” Sci. Rep., vol. 6, p. 33394, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep33394.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Y. Liu, W. Zhou, and Y. Sun, “Optical refractive index sensing based on high-Q bound states in the continuum in free-space coupled photonic crystal slabs,” Sensors, vol. 17, p. 1861, 2017. https://doi.org/10.3390/s17081861.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Z. F. Sadrieva, I. S. Sinev, K. L. Koshelev, et al.., “Transition from optical bound states in the continuum to leaky resonances: role of substrate and roughness,” ACS Photonics, vol. 4, pp. 723–727, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.6b00860.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Y.-X. Xiao, G. C. Ma, Z.-Q. Zhang, and C. T. Chan, “Topological subspace-induced bound state in the continuum,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 118, p. 166803, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.118.166803.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] E. N. Bulgakov and D. N. Maksimov, “Topological bound states in the continuum in arrays of dielectric spheres,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 118, p. 267401, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.118.267401.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] A. Kodigala, T. Lepetit, Q. Gu, B. Bahari, Y. Fainman, and B. Kanté, “Lasing action from photonic bound states in continuum,” Nature, vol. 541, pp. 196–199, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature20799.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Y. Song, N. Jiang, L. Liu, X. Hu, and J. Zi, “Cherenkov radiation from photonic bound states in the continuum: towards compact free-electron lasers,” Phys. Rev. Appl., vol. 10, p. 64026, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevapplied.10.064026.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] B. Midya and V. V. Konotop, “Coherent-perfect-absorber and laser for bound states in a continuum,” Opt. Lett., vol. 43, pp. 607–610, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.43.000607.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Y. V. Kartashov, C. Milian, V. V. Konotop, and L. Torner, “Bound states in the continuum in a two-dimensional PT-symmetric system,” Opt. Lett., vol. 43, pp. 575–578, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.43.000575.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] L. Carletti, K. Koshelev, C. De Angelis, and Y.-S. Kivshar, “Giant nonlinear response at the nanoscale driven by bound states in the continuum,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 121, p. 033903, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.121.033903.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] H. M. Doeleman, F. Monticone, W. den Hollander, A. Alù, and A. F. Koenderink, “Experimental observation of a polarization vortex at an optical bound state in the continuum,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 12, pp. 397–401, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-018-0177-5.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] S. D. Krasikov, A. A. Bogdanov, and I. V. Iorsh, “Nonlinear bound states in the continuum of a one-dimensional photonic crystal slab,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 97, p. 224309, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.97.224309.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] J. Jin, X. Yin, L. Ni, M. Soljacic, B. Zhen, and C. Peng, “Topologically enabled ultra-high-Q guided resonances robust to out-of-plane scattering,” Nature, vol. 574, pp. 501–504, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1664-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] S. Romano, G. Zito, S. N. L. Yepez, et al.., “Tuning the exponential sensitivity of a bound-state-in-continuum optical sensor,” Opt. Express, vol. 27, pp. 18776–18786, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.27.018776.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] X. Gao, B. Zhen, M. Soljacic, H. S. Chen, and C. W. Hsu, “Bound states in the continuum in fiber Bragg gratings,” ACS Photonics, vol. 6, pp. 2996–3002, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.9b01202.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Z. Yu, X. Xi, J. Ma, H. K. Tsang, C.-L. Zou, and X. Sun, “Photonic integrated circuits with bound states in the continuum,” Optica, vol. 6, pp. 1342–1348, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1364/optica.6.001342.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] M. Minkov, D. Gerace, and S. Fan, “Doubly resonant χ(2) nonlinear photonic crystal cavity based on a bound state in the continuum,” Optica, vol. 6, p. 1039, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1364/optica.6.001039.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Z. Sadrieva, K. Frizyuk, M. Petrov, Y. Kivshar, and A. Bogdanov, “Multipolar origin of bound states in the continuum,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 100, p. 115303, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.100.115303.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] C. Huang, C. Zhang, S. Xiao, et al.., “Ultrafast control of vortex microlasers,” Science, vol. 367, pp. 1018–1021, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba4597.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] M. S. Sidorenko, O. N. Sergaeva, Z. F. Sadrieva, et al.., “Observation of an accidental bound state in the continuum in a chain of dielectric disks,” Phys. Rev. Appl., vol. 15, p. 034041, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevapplied.15.034041.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] E. Melik-Gaykazyan, K. Koshelev, J.-H. Choi, et al.., “From Fano to quasi-BIC resonances in individual dielectric nanoantennas,” Nano Lett., vol. 21, pp. 1765–1771, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c04660.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] C. W. Hsu, B. Zhen, A. D. Stone, J. D. Joannopoulos, and M. Soljacic, “Bound states in the continuum,” Nat. Rev. Mater., vol. 1, p. 16048, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1038/natrevmats.2016.48.Suche in Google Scholar

[43] K. Koshelev, A. Bogdanov, and Y. Kivshar, “Meta-optics and bound states in the continuum,” Sci. Bull., vol. 64, pp. 836–842, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scib.2018.12.003.Suche in Google Scholar

[44] K. Koshelev, G. Favraud, A. Bogdanov, Y. Kivshar, and A. Fratalocchi, “Nonradiating photonics with resonant dielectric nanostructures,” Nanophotonics, vol. 8, pp. 725–745, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2019-0024.Suche in Google Scholar

[45] K. Koshelev, A. Bogdanov, and Y. Kivshar, “Engineering with bound states in the continuum,” Opt Photon. News, vol. 31, pp. 38–45, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1364/opn.31.1.000038.Suche in Google Scholar

[46] A. F. Sadreev, “Interference traps waves in open system: bound states in the continuum,” 2020, preprint https://arxiv.org/abs/2011.01221.Suche in Google Scholar

[47] H. Nakamura, N. Hatano, S. Garmon, and T. Petrosky, “Quasibound states in the continuum in a two channel quantum wire with an adatom,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 99, p. 210404, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.99.210404.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] M. V. Gustafsson, T. Aref, A. F. Kockum, M. K. Ekstrom, G. Johansson, and P. Delsing, “Propagating phonons coupled to an artificial atom,” Science, vol. 346, pp. 207–211, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1257219.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] A. F. Kockum, G. Johansson, and F. Nori, “Decoherence-free interaction between giant atoms in waveguide quantum electrodynamics,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 120, p. 140404, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.120.140404.Suche in Google Scholar

[50] G. Andersson, B. Suri, L. Guo, T. Aref, and P. Delsing, “Non-exponential decay of a giant artificial atom,” Nat. Phys., vol. 15, pp. 1123–1127, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-019-0605-6.Suche in Google Scholar

[51] P. Facchi, D. Lonigro, S. Pascazio, F. V. Pepe, and D. Pomarico, “Bound states in the continuum for an array of quantum emitters,” Phys. Rev. A, vol. 100, p. 023834, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.100.023834.Suche in Google Scholar

[52] B. Kannan, M. Ruckriegel, D. Campbell, et al.., “Waveguide quantum electrodynamics with giant superconducting artificial atoms,” Nature, vol. 583, pp. 775–779, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2529-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[53] S. Longhi, “Photonic simulation of giant atom decay,” Opt. Lett., vol. 45, pp. 3017–3020, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.393578.Suche in Google Scholar

[54] L. Guo, A. F. Kockum, F. Marquardt, and G. Johansson, “Oscillating bound states for a giant atom,” Phys. Rev. Res., vol. 2, p. 043014, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevresearch.2.043014.Suche in Google Scholar

[55] S. Guo, Y. Wang, T. Purdy, and J. Taylor, “Beyond spontaneous emission: giant atom bounded in the continuum,” Phys. Rev. A, vol. 102, p. 033706, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.102.033706.Suche in Google Scholar

[56] S. Xia, A. Ramachandran, S. Xia, et al.., “Unconventional flatband line states in photonic Lieb lattices,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 121, p. 263902, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.121.263902.Suche in Google Scholar

[57] J. D. Bodyfelt, D. Leykam, C. Danieli, X. Yu, and S. Flach, “Flatbands under correlated perturbations,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 113, p. 236403, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.113.236403.Suche in Google Scholar

[58] D. Leykam and S. Flach, “Photonic flatbands,” APL Photonics, vol. 3, p. 070901, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5034365.Suche in Google Scholar

[59] S. Longhi, “Rabi oscillations of bound states in the continuum,” Opt. Lett., vol. 49, pp. 2091–2094, 2021.10.1364/OL.424756Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[60] A. Yariv, Y. Xu, R. K. Lee, and A. Scherer, “Coupled-resonator optical waveguide: a proposal and analysis,” Opt. Lett., vol. 24, pp. 711–713, 1999. https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.24.000711.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[61] S. Olivier, C. Smith, M. Rattier, et al.., “Miniband transmission in a photonic crystal coupled-resonator optical waveguide,” Opt. Lett., vol. 26, pp. 1019–1021, 2001. https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.26.001019.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[62] S. Longhi and G. Della Valle, “Many-particle quantum decay and trapping: the role of statistics and Fano resonances,” Phys. Rev. A: At., Mol., Opt. Phys., vol. 86, p. 012112, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.86.012112.Suche in Google Scholar

[63] S. Longhi, “Quantum decay in a topological continuum,” Phys. Rev. A, vol. 100, p. 022123, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.100.022123.Suche in Google Scholar

[64] S. Longhi, “Optical Bloch oscillations and Zener tunneling with nonclassical light,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 101, p. 193902, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.101.193902.Suche in Google Scholar

[65] P. L. Knight, M. A. Lauder, and B. J. Dalton, “Laser-induced continuum structure,” Phys. Rep., vol. 190, pp. 1–61, 1990. https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-1573(90)90089-k.Suche in Google Scholar

[66] E. Frishman and M. Shapiro, “Complete suppression of spontaneous decay of a manifold of states by infrequent interruptions,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 87, p. 253001, 2001. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.87.253001.Suche in Google Scholar

[67] S. Zhang, Z. Ye, Y. Wang, et al.., “Anti-Hermitian plasmon coupling of an array of gold thin-film antennas for controlling light at the nanoscale,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 109, p. 193902, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.109.193902.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[68] R. Morandotti, U. Peschel, J. S. Aitchison, H. S. Eisenberg, and Y. Silberberg, “Experimental observation of linear and nonlinear optical Bloch oscillations,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 83, p. 4756, 1999. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.83.4756.Suche in Google Scholar

[69] T. Pertsch, P. Dannberg, W. Elflein, A. Bräuer, and F. Lederer, “Optical Bloch oscillations in temperature tuned waveguide arrays,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 83, p. 4752, 1999. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.83.4752.Suche in Google Scholar

[70] D. N. Christodoulides, F. Lederer, and Y. Silberberg, “Discretizing light behaviour in linear and nonlinear waveguide lattices,” Nature, vol. 424, pp. 817–823, 2003. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01936.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[71] S. Longhi, “Quantum-optical analogies using photonic structures,” Laser Photon. Rev., vol. 3, pp. 243–261, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.200810055.Suche in Google Scholar

[72] I. L. Garanovich, S. Longhi, A. A. Sukhorukov, and Y. S. Kivshar, “Light propagation and localization in modulated photonic lattices and waveguides,” Phys. Rep., vol. 518, pp. 1–79, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2012.03.005.Suche in Google Scholar

[73] A. Block, C. Etrich, T. Limboeck, et al.., “Bloch oscillations in plasmonic waveguide arrays,” Nat. Commun., vol. 5, p. 3843, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4843.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[74] S. Longhi, “Stopping and time reversal of light in dynamic photonic structures via Bloch oscillations,” Phys. Rev. E, vol. 75, p. 026606, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreve.75.026606.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[75] L. Yuan and S. Fan, “Bloch oscillation and unidirectional translation of frequency in a dynamically modulated ring resonator,” Optica, vol. 3, pp. 1014–1018, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1364/optica.3.001014.Suche in Google Scholar

[76] S. Longhi, “Optical Zener-Bloch oscillations in binary waveguide arrays,” Europhys. Lett., vol. 76, pp. 416–421, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1209/epl/i2006-10301-8.Suche in Google Scholar

[77] B. M. Breid, D. Witthaut, and H. J. Korsch, “Bloch-Zener oscillations,” New J. Phys., vol. 8, p. 110, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/8/7/110.Suche in Google Scholar

[78] B. M. Breid, D. Witthaut, and H. J. Korsch, “Manipulation of matter waves using Bloch and Bloch-Zener oscillations,” New J. Phys., vol. 9, p. 62, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/9/3/062.Suche in Google Scholar

[79] F. Dreisow, A. Szameit, M. Heinrich, et al.., “Bloch-Zener oscillations in binary superlattices,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 102, p. 076802, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.076802.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[80] S. Longhi, “Bloch-Zener quantum walk,” J. Phys. B, vol. 45, p. 225504, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-4075/45/22/225504.Suche in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article offers supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2021-0260).

© 2021 Stefano Longhi published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- The science of harnessing light’s darkness

- Reviews

- Bound states in the continuum in resonant nanostructures: an overview of engineered materials for tailored applications

- Reconfigurable nonlinear response of dielectric and semiconductor metasurfaces

- Research Articles

- Active angular tuning and switching of Brewster quasi bound states in the continuum in magneto-optic metasurfaces

- Resonance-forbidden second-harmonic generation in nonlinear photonic crystals

- Dispersive bands of bound states in the continuum

- Dressed emitters as impurities

- Engineering gallium phosphide nanostructures for efficient nonlinear photonics and enhanced spectroscopies

- Ultraviolet second harmonic generation from Mie-resonant lithium niobate nanospheres

- Label-free DNA biosensing by topological light confinement

- Guided-mode resonance on pedestal and half-buried high-contrast gratings for biosensing applications

- Ways to achieve efficient non-local vortex beam generation

- Fabrication robustness in BIC metasurfaces

- Bound states in the continuum in periodic structures with structural disorder

- Demonstration of on-chip gigahertz acousto-optic modulation at near-visible wavelengths

- Integrated diffraction gratings on the Bloch surface wave platform supporting bound states in the continuum

- Ultrahigh-Q system of a few coaxial disks

- Bound states in the continuum in strong-coupling and weak-coupling regimes under the cylinder – ring transition

- Two tractable models of dynamic light scattering and their application to Fano resonances

- Polarization-independent anapole response of a trimer-based dielectric metasurface

- Transparent hybrid anapole metasurfaces with negligible electromagnetic coupling for phase engineering

- Nonradiating sources for efficient wireless power transfer

- Anapole-enabled RFID security against far-field attacks

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- The science of harnessing light’s darkness

- Reviews

- Bound states in the continuum in resonant nanostructures: an overview of engineered materials for tailored applications

- Reconfigurable nonlinear response of dielectric and semiconductor metasurfaces

- Research Articles

- Active angular tuning and switching of Brewster quasi bound states in the continuum in magneto-optic metasurfaces

- Resonance-forbidden second-harmonic generation in nonlinear photonic crystals

- Dispersive bands of bound states in the continuum

- Dressed emitters as impurities

- Engineering gallium phosphide nanostructures for efficient nonlinear photonics and enhanced spectroscopies

- Ultraviolet second harmonic generation from Mie-resonant lithium niobate nanospheres

- Label-free DNA biosensing by topological light confinement

- Guided-mode resonance on pedestal and half-buried high-contrast gratings for biosensing applications

- Ways to achieve efficient non-local vortex beam generation

- Fabrication robustness in BIC metasurfaces

- Bound states in the continuum in periodic structures with structural disorder

- Demonstration of on-chip gigahertz acousto-optic modulation at near-visible wavelengths

- Integrated diffraction gratings on the Bloch surface wave platform supporting bound states in the continuum

- Ultrahigh-Q system of a few coaxial disks

- Bound states in the continuum in strong-coupling and weak-coupling regimes under the cylinder – ring transition

- Two tractable models of dynamic light scattering and their application to Fano resonances

- Polarization-independent anapole response of a trimer-based dielectric metasurface

- Transparent hybrid anapole metasurfaces with negligible electromagnetic coupling for phase engineering

- Nonradiating sources for efficient wireless power transfer

- Anapole-enabled RFID security against far-field attacks