Abstract

Background and aims

Research investigating differences in pain location and distribution across conditions is lacking. Mapping a patient’s pain may be a useful way of understanding differences in presentations, however the use of pain mapping during a pain provocation task has not been investigated. The aim of this study was to assess the reliability of patient and clinician rated pain maps during a pain provocation task for the anterior knee.

Methods

Participants were recruited from a larger study of professional Australian rules football players (n=17). Players were invited to participate if they reported a current or past history of patellar tendon pain. No clinical diagnosis was performed for this reliability study. Participants were asked to point on their own knee where they usually experienced pain, which was recorded by a clinician on a piloted photograph of the knee using an iPad. Participants then completed a single leg decline squat (SLDS), after which participants indicated where they experienced pain during the task with their finger, which was recorded by a clinician. Participants then recorded their own self-rated pain map. This process was repeated 10 min later. Pain maps were subjectively classified into categories of pain location and spread by two raters. Pain area was quantified by the number of pixels shaded. Intra- and inter-rater reliability (between participants and clinicians) were analysed for pain area, similarity of location as well as subjective classification.

Results

Test-retest reliability was good for participants (intraclass correlation coefficients [ICC]=0.81) but only fair for clinicians (ICC=0.47) for pain area. There was poor agreement between participants and clinicians for pain area (ICC=0.16) and similarity of location (Jaccard index=0.19). Clinicians had good inter- and intra-rater reliability of classification of pain spread (k=0.75 and 0.67).

Conclusions

Participant completed pain maps were more reliable than clinician pain maps. Clinicians were reliable at classifying pain based on location and type of spread.

Implications

Clinicians should ask patients to complete their own pain maps following a pain provocation test, to elicit the most reliable and consistent understanding of their pain perception.

1 Introduction

Knee injuries represent some of the most common musculoskeletal conditions, across both athletes and the general population, leading to pain, disability and financial burden. The prevalence of people with anterior knee pain in the general population has been reported to be as high as 25% [1], and may be higher in certain subgroups such as athletes [2]. A number of different sources of nociception have been hypothesised to underpin anterior knee pain and there are a variety of differential diagnoses that can be considered for the anterior knee [3]. The specific pain location, and the spread of this pain, identified during clinical tests may be useful for sub-grouping patients with anterior knee pain, as other assessments, such as imaging, demonstrate high amounts of asymptomatic pathology, and thus, false positives. Common clinical tests used, such as squatting, reproduce symptoms around the anterior knee making them suitable to use as pain provocation tests. In the clinical and research setting, such clinical tests are commonly used as a dichotomous outcome (i.e. the presence or absence of pain). However, as these tests may provoke all types of anterior knee pain, the use of a yes/no outcome measure does not provide any specificity in differentiating a particular clinical diagnosis or patient sub-group. It is theorised that there are many drivers of nociception, and therefore potentially many patient sub-groups in anterior knee pain conditions (for example, problems with the cartilage, fat pad or patellar tendon). However, no work has yet tried to separate or understand these differences with regards to how it relates to the clinical presentation. Before being able to understand the different pain drivers in these subgroups, reliable methods for identifying pain location and spread are required.

One of the methods proposed for reliably identifying, and tracking, pain location and spread in musculoskeletal conditions is pain mapping. Previous studies have utilised artist drawn images, diagrams or photographs with zones pre-drawn on them, with patients reporting a preference for photographs or three dimensional images [4], [5]. The studies have varied in terms of whether the patient or clinician identifies the zones on the map where the pain is located [4], [5]. Other studies have also used different methods for analysing pain maps including: classifying pain location based on predetermined zones [6], [7], [8] (peripateller, retropatellar, or mixed) or investigating the spread of pain using categorical classifications (localised, regional or diffuse [9]). No single method has been identified as preferable, and it is possible optimal methods for quantifying pain location may differ between body parts or clinical presentations.

Despite the high prevalence of anterior knee pain, studies investigating the location and distribution of pain across different clinical presentations are lacking. Of the studies investigating pain mapping in knee conditions, three have focused exclusively on anterior knee pain conditions [cohorts of patellofemoral pain (PFP)] [8], [9], [10], while others have either included a variety of knee pain diagnoses [4], or included only tibio-femoral knee pain cases [4], [6]. All previous studies have only used patient recall of the painful area, and no study has investigated pain mapping during a pain provocation test. Two articles based their pain maps on palpatory findings [7], [8], however, palpation is sensitive but non-specific due to several issues including heterosynaptic plasticity. Convergence of afferent fibres back to the spinal cord can create challenges in differential diagnosis in a region, due to differences in receptive fields [11]. Finally, it is also important to ascertain whether clinicians or patients can reliably record a patient’s pain location and its spread and that these tests are repeatable. Thompson et al. [6] only completed clinician recorded pain maps. While Elson et al. [4] took both patient and clinician recorded maps, they did not look at the correlation between the two maps. Both of those studies categorised pain location into zones and did not look at the size of the painful area reported. As yet no study has investigated whether clinicians are able to accurately record patient reported knee pain location.

Therefore, the aims of this study were to (1) assess the reliability [12] of self-rated and clinician-rated pain maps of the anterior knee during a pain provocation for classifying pain location and distribution, and (2) compare agreement between self-rated and clinician-rated pain mapping (pain location and distribution) of the anterior knee during a pain provocation task.

2 Methods

This cross-sectional study was undertaken as part of a larger prospective cohort study investigating the burden of patellar and Achilles tendon pain in elite Australian football (AF) players [13]. Approval for this project was obtained from the La Trobe University Human Ethics Committee (S15-224). Following agreement by team staff for participation, informed consent was sought from individual players for inclusion.

2.1 Participants

In the last month of the competitive season, elite male AF players were invited to participate in the current study. A consecutive selection of players from three clubs who reported current, or a history of, patellar tendon pain were invited to participate in this sub study (n=477 from 12 clubs). Invitation to this sub study was based on convenience to the researcher’s location in Melbourne. Participants were excluded if they had undergone knee surgery in the last 6 months or had another injury that prevented them from completing a decline squat. Where participants had bilateral knee pain symptoms, their most painful side during a pain provocation task was chosen as the focus for this study.

2.2 Outcomes

2.2.1 VISA-P

All participants completed the Victorian Institute of Sport-Patellar tendon (VISA-P) questionnaire prior to testing, with 100 indicating full function and no symptoms. The VISA-P is a reliable patient reported outcome measure to measure pain and function of patients with patellar tendinopathy [14].

2.2.2 OSTRC overuse injury questionnaire

The Oslo Sports Trauma Research Centre (OSTRC) questionnaire consists of four multiple-choice questions that focus on: difficulty participating; reduced training; performance affected; and pain experienced [15]. The questionnaire posed the questions above in respect to the patellar tendon. Players provided their responses to the questionnaire on an online Google form. A sum score of results was calculated for each player between 0 and 100, with a score of zero indicating that the player is participating in all aspects of training and competition, performing at their optimum and has no pain. An additional question was asked at the beginning of completing the OSTRC on players’ history of having a patellar tendon problem.

2.2.3 Pain provocation test

A single-leg decline squat was used as the pain-provocation test. The single leg decline squat is a clinical test to load the knee extensors on a 25° decline board and is considered useful for assessing patients with patellar tendinopathy [16]. However, this test may aggravate many conditions of the anterior knee. A demonstration and instructions were provided to participants. The instructions were to stand on one foot in the middle of the decline squat board, keeping their shoulders and back flat against the wall. Participants squatted down to 60 degrees knee flexion, or where pain prevented them from going any lower, before returning to the starting position. Following this, participants reported their pain on a numerical rating scale (NRS) of 0–10, 0 being no pain at all to 10 being the worst pain imaginable.

2.2.4 Pain maps

An area of pain was recorded using the Sketchbook app (Autodesk, California, v3.6.1), on a computer tablet (Apple iPad mini 3, CA, USA). Electronic tablets have been used previously for pain mapping with good reliability [5], [17]. Using the software, participants were able to draw over an image of a knee using a stylus. The type, stroke setting, colour, and pixel diameter were standardised for all testing. The researchers trialled different images of the knee during pilot testing, and the final version used in this study was an image of the anterior knee in slight flexion, as it was most clear in visualising bony and muscular landmarks (Fig. 1). A clinician-rater trialled this final version with a standardised script of instructions over a 2-month period prior to testing.

The final image utilised, over which pain maps were drawn.

2.3 Procedures/process

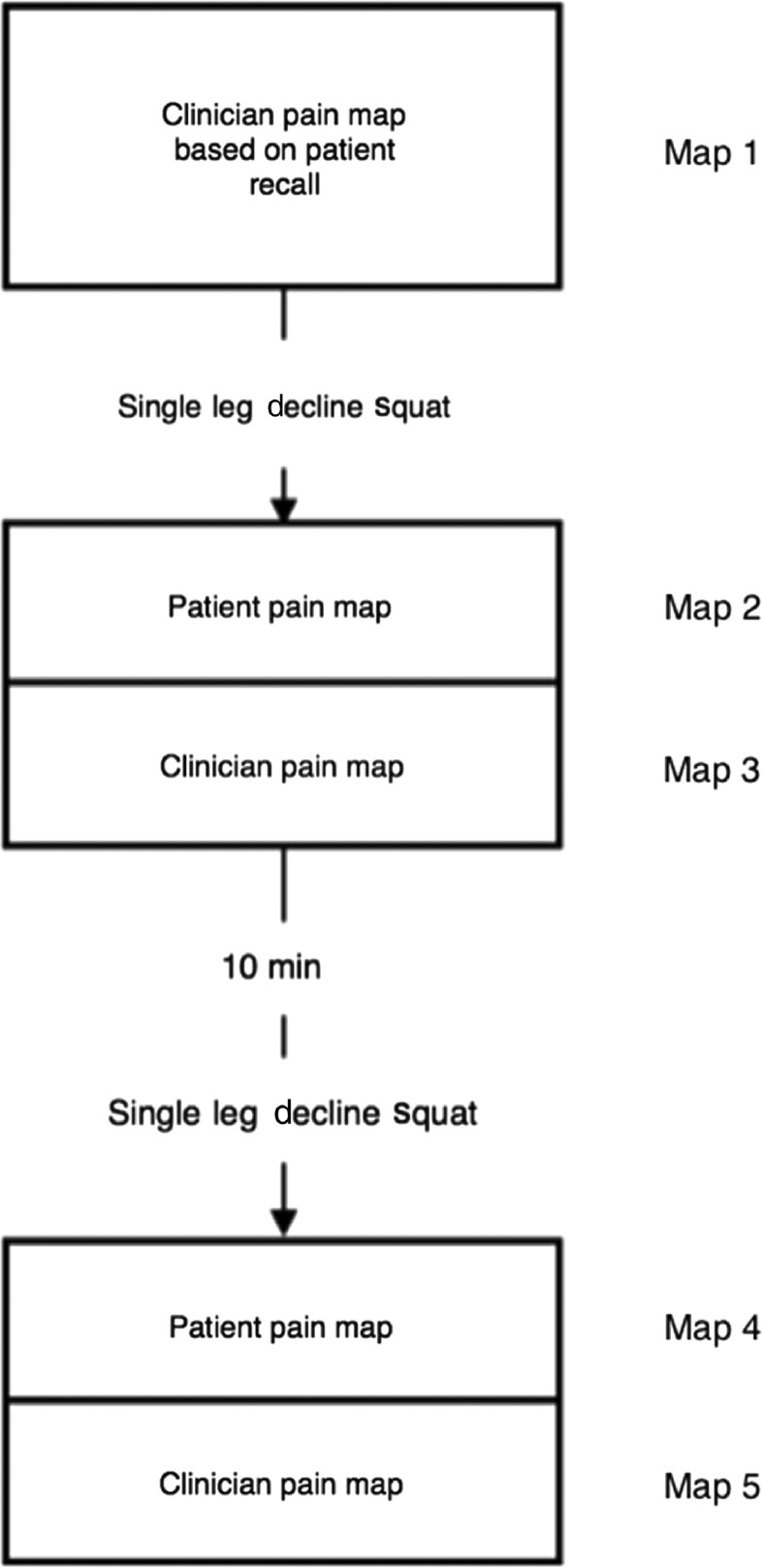

Participants were asked to point on their own knee where they experienced pain, without any verbal description. A single clinician-rater then marked the area of pain indicated by the participant, by shading the location and area indicated on the iPad pain map. This served as a clinician-rated pain map of the patient’s recollection of their pain location (map 1, Fig. 2).

Flow diagram outlining process for collection of pain maps.

The pain provocation test was performed, and participants were then immediately asked to give a numerical pain score. The location of pain was indicated by participants by pointing to it on their knee, without any verbal indicators. This was recorded by a single clinician-rater on the iPad pain map (map 2). Finally, the participant was asked to record the location of pain themselves on the iPad pain map (map 3). The same pain provocation process and mapping were repeated 10 min later to assess test-retest reliability (map 4 – clinician, and map 5 – participant). Throughout testing, the participant and clinician remained blinded to each other’s pain marking.

2.4 Pain map analysis

A single rater (JT) performed quantitative analysis of the pain maps. All maps were checked for any aberrant markings that fell outside the knee. These were erased using the GNU Image Manipulation Program (GIMP) (version 2.9.2) (GNU, free software foundation, Boston, USA). All maps were coded so as to allow the assessor to be blind to participant and rater.

Pain distribution was quantified using ImageJ (version 1.50i), an open source image processing program (imagej.net). The number of pixels coloured (total area) were quantified as a measure of pain distribution.

Subsequently, subjective measures of pain spread were completed by two raters (MG, SD). Pain maps were classified on spread; (1) local, (2) regional, or (3) diffuse, based on a modification of the classification used by Rathleff et al. [9]. Localised pain was defined as a spread of two finger widths or less. Regional pain was anything larger than two finger widths (but less than four finger widths). Participants who were not able to localise their pain and showed their pain to be all over the knee, were classified as diffuse pain. Pain location was also separately classified (for the same images) based on location; as being (1) retropatellar pain, (2) peripatellar pain, or (3) mixed. Finally, raters also dichotomised whether the patients reported pain being localised inferior patella pole pain (two finger widths or less) or not.

2.5 Statistical analysis

Analysis was performed using SPSS software (Version 24.0, Chicago, IL, USA). The alpha level was set at 0.05. For each measure the following pain maps were compared:

intra-rater test-retest reliability for both participants and clinicians

using maps 2 and 4 for clinicians, and 3 and 5 for participants (Fig. 2)

inter-rater reliability between clinicians and participants

using maps 2 and 3

validity of the clinician-rated maps of patient recollection compared to the clinician-rated pain map during a single-leg decline squat

using maps 1 and 2

Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) (two-way mixed models) for size of pain area (number of pixels) were calculated. An ICC of 0–0.39 was considered poor, 0.40–0.59 was deemed fair; 0.60–0.74 was good while 0.75–1.0 was excellent [18].

Additionally, the Jaccard index was calculated to ascertain a measure of similarity for both pain distribution and location [19]. The score for similarity (where one represents complete overlap and similarity and zero implies no overlap at all) is calculated by dividing the amount of area that overlaps (pixels), by the total area of the overlap and overlay together. The two relevant pain maps were layered over each other and pixels in each region were quantified using ImageJ.

Finally, a Pooled Similarity statistic was then calculated by adding the Jaccard index (score for similarity of location), to the ICC score (score for similarity of pain area) and dividing this by 2.

For subjective reporting of pain maps, intra-rater (maps 2 and 4) and inter-rater reliability (between clinicians) (map 2) of pain classification based on spread and location were assessed using Cohen’s κ statistic. The same analysis was also completed for the reliability of localised inferior pole pain.

3 Results

Seventeen male elite level AF players were included. Participants were an average age of 24±3.7 years old, an average height of 191.8±9 cm, and an average weight of 89.9±9.8 kg. Mean VISA-P was 89.7±11.4 and mean OSTRC score was 5.5±8.7.

Mean pain area expressed as pixels is shown in Table 1. Median pain reported (NRS) was 2.0 (IQR 5.0) during the SLDS. There was no difference for NRS between each SLDS trial (median 2.0±4.5 vs. 2.0±5.5). There was no significant correlation between pain scores and pain area (pixels) as rated by clinicians (r=−0.022, p=0.904) or patients (r=0.215, p=0.222).

Mean pain area expressed as pixels.

| Clinician |

Participant |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Map 1 | Map 2 | Map 3 | Map 4 | Map 5 | |

| Median pixels (IQR) | 6378.5 (5058.75) | 5900.5 (3124.0) | 7316.5 (4799.3) | 7101.5 (12691.5) | 6802.0 (13115.0) |

Test-retest reliability for the area of pain was considered as fair for clinicians (ICC=0.47), and very good for participants (ICC=0.81) (Table 2). Agreement between clinician and participant was poor (ICC=0.16) in quantifying the pain area. Baseline pain maps (clinician rated based on patient recall) had poor reliability compared to provocation test clinician pain maps for pain area (ICC=0.32).

Summary of reliability analysis for pain area and location.

| Maps compared | Pain area |

Pain location |

Pooled similarity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICC (95% CI) | Jaccard index mean (SD) | ||||

| Clinician test-retest | 2 and 4 | 0.47 (0.02–0.76) p=0.022 | Fair | 0.30 (0.23) | 0.39 |

| Participant test-retest | 3 and 5 | 0.81 (0.56–0.93) p<0.001 | Excellent | 0.26 (0.20) | 0.54 |

| Clinician vs. participant | 2 and 3 | 0.16 (−0.30–0.57) p=0.261 | Poor | 0.19 (0.10) | 0.18 |

| Participant recollection vs. provocation test | 1 and 2 | 0.32 (−0.16–0.68) p=0.093 | Poor | 0.34 (0.20) | 0.33 |

Jaccard index score for the degree of similarity in pain location were generally low (0.30 for clinicians, 0.26 for participants, 0.19 for inter-rater). Pooled similarity values showed highest scores for test-retest of participant rated pain maps (0.56).

3.1 Subjective interpretation

Test-retest reliability for pain location was good (k=0.75), as was for pain location (k=0.75) (Table 3). Inter-rater reliability of pain type was good and pain location was moderate (k=0.40). Inter-rater reliability of localised inferior patella pole pain was good (k=0.66).

Reliability analysis for subjective classification of pain maps by clinicians.

| Intra-rater (test-retest) | ||

| Pain spread | 0.75 (0.43–1.00) | 0.001 |

| Pain location | 0.75 (0.42–1.00) | >0.001 |

| Reliability of inferior pole pain | 0.66 (0.50–0.84) | >0.001 |

| Inter-rater reliability (clinicians) | κ | p-Value |

| Pain spread | 0.67 (0.46–0.88) | >0.001 |

| Pain location | 0.40 (0.16–0.64) | >0.001 |

| Participant recollection vs. provocation test | ||

| Pain spread | 0.74 (0.40–1.00) | 0.002 |

| Pain location | 0.55 (0.12–0.98) | 0.006 |

4 Discussion

This is the first study to investigate knee pain mapping during a commonly performed pain provocation task for the anterior knee. Participants showed greater reliability in completing their own pain maps compared to clinicians mapping the participant’s pain, and there was significant disparity between participant and clinician rated pain maps. Despite this, clinicians showed good reliability at classifying the type of pain (regional, focal, diffuse) that participants indicated.

The findings highlight the difficulties in interpreting pain mapping in musculoskeletal conditions. Arguably there is no gold standard against which pain maps can be validated against, as even patient drawn maps may be prone to error due to improper recognition of anatomical landmarks on the corresponding body chart. Clinician-recorded pain maps are routinely used in practice in the format of body charts, however the findings of the current research highlight the disparity between clinician and patient drawn pain maps. Test-retest reliability may also be affected by changing or moving pain distribution, as even 10 min apart, pain may be affected by differing conditions such as warm up, prior activity, prior knee positioning and specific biomechanical loading, though there was no difference between reported pain (NRS) between the 1st or 2nd SLDS in this study. Given these findings, it may be best for patients to complete pain maps themselves for clinicians to gauge the best information about their pain.

Another important factor to consider is potential differences in reported baseline pain to pain on a provocation test. All previous research in pain mapping at the knee has only assessed pain based on recall [4], [9], [10] and not during a specific task or provocation test. While it appears that the type of pain at baseline (local or regional) can be distinguished by clinicians with good reliability during a task, the exact location was less reliable from baseline reporting. It is therefore probably best for clinicians to ascertain whether pain is localised or regional during subjective examination, and then ask patients to complete a pain map during a provocation task to determine the exact location.

Previous studies in knee pain mapping have classified pain based on predetermined zones around the knee [4], [6], [8]. Pre-determined zones present challenges as to the amount of pixels that are sufficient for a zone to be selected as being a pain area. Such zones also rely on borders that are pre-determined based on anatomical location (which a patient may not understand or recognise), or on arbitrarily decided regions. Our findings are similar to previous studies [6], showing classification based on whether pain is localised, regional or diffuse is reliable.

While the clinician-rated reliability of location of pain was only fair, the reliability of localised inferior patella pole pain was good. This is important, as this pain distribution is critical in the diagnostic criteria for diagnosing patellar tendinopathy [20], which is located at the inferior pole in athletes that jump and change direction. Further, it is not currently clear whether specific information about pain location adds value to a clinical examination, beyond its relationship to the patella (with pain location being retro- or peri-, medial or lateral, inferior or superior to the patella). Numerous structures may be involved in pain sensitisation as well as the potential for changes to central pain processing [21], [22]. Of interest, this study’s participants (with different pain maps) all presented for this study as they considered their knee pain to be patellar tendinopathy. However, the participant pain maps were not homogenous and future research should examine whether they respond differently to different clinical interventions. Clinical testing can non-specifically aggravate different presentations, thus the differentiation of potential sub-groups are only clinically useful if they are predictive for response to treatment (i.e. responders and non-responders to specific exercise program). Most research is conducted with participants who present with specific diagnoses, however studies lack detail around their inclusion criteria and many clinical tests are provocative for a number of pathologies.

There were limitations of this research. Firstly, only a small sample size completed the task, and variations in findings may be conflated. Participants were recruited based on self-reported past history of patellar tendon pain, or current patella tendon pain as reported on a patient outcome. They were not formally assessed and diagnosed by clinicians, hence inferences should not be made relating the pain map findings to the clinical condition, as this was a reliability study. Also, the participants had low levels of pain on the provocation task, and VISA-P values were high (indicative of good function) compared to previous research in symptomatic populations [23].

Issues related to recognition of the anatomical landmarks may have affected findings. Different images were pilot tested prior to conducting this research, however recognition by participants would probably be maximised if images of their own knee were used, allowing for recognition of self. This however would not allow for analysis of spread/distribution as a cohort due to variation in the size of the body map. Previous research has suggested photographic pain maps were preferred to anatomic drawings or outlines [4], however anatomical variations may exist between people, which may result in people not being able to assimilate images to the knee in front of them.

The findings in this cohort of elite AF players should be generalised with caution to other population groups due to their unique training environment and physicality. Future research may consider critical features such as muscle bulk, gender differences, and age of participants, as well as familiarity training (i.e. recognising limb features such as bony landmarks and checking accuracy). Further, studies may consider providing images with common pain maps represented that patients and clinicians can select from, rather than draw themselves, as this may be easier for patients and/or clinicians to interpret.

5 Conclusion

Participant self-mapping of their knee pain location, using a tablet application on an iPad, was shown to be reliable following a provocative task. Clinicians were reliable at classifying whether pain was local or regional and at classifying the specific area of inferior patella pole pain. However, there was poor similarity between clinician- and participant-rated pain maps during a provocation task, which is an important clinical and research finding. To form the most accurate picture of a patient’s pain perception, it is recommended that clinicians ascertain whether pain is localised, regional or diffuse, and then patients map the location of their pain. A critical step following on from this work is to establish whether these clinical presentations respond differently to different interventions. Given the lack of gold standard for pathological diagnoses, pain mapping may be a useful clinical and research adjunct to better describe clinical populations and define people who do, and do not, respond to treatments.

-

Authors’ statements

-

Research funding: This project was supported by the Australian Football League Research Board Priority Grant (2016). ER is supported by NHMRC early career research fund.

-

Conflict of interest: None declared.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was gained from all participants.

-

Ethical approval: This research was approved by La Trobe University Human Research Ethics Committee (S15-224).

-

Author contributions: ER, SD, LV were involved in designing the research. ER, SD, JT, CG were involved in piloting and data collection. ER, MG, LV, SD were involved in data analysis, and manuscript preparation. All authors have read and approved the paper.

References

[1] Callaghan MJ, Selfe J. Has the incidence or prevalence of patellofemoral pain in the general population in the United Kingdom been properly evaluated? Phys Ther Sport 2007;8:37–43.10.1016/j.ptsp.2006.07.001Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Boling M, Padua D, Marshall S, Guskiewicz K, Pyne S, Beutler A. Gender differences in the incidence and prevalence of patellofemoral pain syndrome. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2010;20:725–30.10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.00996.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Dye SF, Vaupel GL, Dye CC. Conscious neurosensory mapping of the internal structures of the human knee without intraarticular anesthesia. Am J Sports Med 1998;26:773–7.10.1177/03635465980260060601Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Elson DW, Jones S, Caplan N, Stewart S, St Clair Gibson A, Kader DF. The photographic knee pain map: locating knee pain with an instrument developed for diagnostic, communication and research purposes. Knee 2011;18:417–23.10.1016/j.knee.2010.08.012Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Boudreau SA, Badsberg S, Christensen SW, Egsgaard LL. Digital pain drawings: assessing touch-screen technology and 3D body schemas. Clin J Pain 2016;32:139–45.10.1097/AJP.0000000000000230Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Thompson LR, Boudreau R, Hannon MJ, Newman AB, Chu CR, Jansen M, Nevitt MC, Kwoh CK, Osteoarthritis Initiative I. The knee pain map: reliability of a method to identify knee pain location and pattern. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61: 725–31.10.1002/art.24543Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Brushoj C, Holmich P, Nielsen MB, Albrecht-Beste E. Acute patellofemoral pain: aggravating activities, clinical examination, MRI and ultrasound findings. Br J Sports Med 2008;42:64–7; discussion 7.10.1136/bjsm.2006.034215Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Post WR, Fulkerson J. Knee pain diagrams: correlation with physical examination findings in patients with anterior knee pain. Arthroscopy 1994;10:618–23.10.1016/S0749-8063(05)80058-1Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Rathleff MS, Roos EM, Olesen JL, Rasmussen S, Arendt-Nielsen L. Lower mechanical pressure pain thresholds in female adolescents with patellofemoral pain syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2013;43:414–21.10.2519/jospt.2013.4383Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Boudreau SA, Kamavuako EN, Rathleff MS. Distribution and symmetrical patellofemoral pain patterns as revealed by high-resolution 3D body mapping: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2017;18:160.10.1186/s12891-017-1521-5Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Woolf CJ, Salter MW. Neuronal plasticity: increasing the gain in pain. Science 2000;288:1765–9.10.1126/science.288.5472.1765Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 1979;86:420–8.10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Docking SI, Rio E, Cook J, Orchard J, Fortington LV. The prevalence of Achilles and patellar tendon injuries in Australian Football players beyond a time-loss definition. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2018. [Epub ahead of print].10.1111/sms.13086Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Visentini PJ, Khan KM, Cook JL, Kiss ZS, Harcourt PR, Wark JD. The VISA score: an index of severity of symptoms in patients with jumper’s knee (patellar tendinosis). Victorian Institute of Sport Tendon Study Group. J Sci Med Sport 1998;1:22–8.10.1016/S1440-2440(98)80005-4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Clarsen B, Myklebust G, Bahr R. Development and validation of a new method for the registration of overuse injuries in sports injury epidemiology: the Oslo Sports Trauma Research Centre (OSTRC) overuse injury questionnaire. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:495–502.10.1136/bjsports-2012-091524Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Mendonca Lde M, Ocarino JM, Bittencourt NF, Fernandes LM, Verhagen E, Fonseca ST. The Accuracy of the VISA-P Questionnaire, Single-Leg Decline Squat, and Tendon Pain History to Identify Patellar Tendon Abnormalities in Adult Athletes. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2016;46: 673–80.10.2519/jospt.2016.6192Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Jamison RN, Washington TA, Gulur P, Fanciullo GJ, Arscott JR, McHugo GJ, Baird JC. Reliability of a preliminary 3-D pain mapping program. Pain Med 2011;12:344–51.10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.01049.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol Assess 1994;6:284–90.10.1037//1040-3590.6.4.284Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Fuxman Bass JI, Diallo A, Nelson J, Soto JM, Myers CL, Walhout AJ. Using networks to measure similarity between genes: association index selection. Nat Methods 2013;10:1169–76.10.1038/nmeth.2728Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Malliaras P, Cook J, Purdam C, Rio E. Patellar tendinopathy: clinical diagnosis, load management, and advice for challenging case presentations. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2015;45:887–98.10.2519/jospt.2015.5987Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Rathleff MS, Rathleff CR, Stephenson A, Mellor R, Matthews M, Crossley K, Vicenzino B. Adults with patellofemoral pain do not exhibit manifestations of peripheral and central sensitization when compared to healthy pain-free age and sex matched controls – an assessor blinded cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0188930.10.1371/journal.pone.0188930Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Pazzinatto MF, de Oliveira Silva D, Barton C, Rathleff MS, Briani RV, de Azevedo FM. Female adults with patellofemoral pain are characterized by widespread hyperalgesia, which is not affected immediately by patellofemoral joint loading. Pain Med 2016;17:1953–61.10.1093/pm/pnw068Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Visnes H, Hoksrud A, Cook J, Bahr R. No effect of eccentric training on jumper’s knee in volleyball players during the competitive season: a randomized clinical trial. Clin J Sport Med 2005;15:227–34.10.1097/01.jsm.0000168073.82121.20Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

©2018 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain. Published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston. All rights reserved.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial comment

- Diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome

- Body image concerns and distortions in people with persistent pain

- The prevalence of recurrent pain in childhood is high and increases with age

- Friends in pain: pain tolerance in a social network

- Clinical pain research

- Correlation of clinical grading, physical tests and nerve conduction study in carpal tunnel syndrome

- Spectroscopic differences in posterior insula in patients with chronic temporomandibular pain

- Deconstructing chronicity of musculoskeletal pain: intensity-duration relations, minimal dimensions and clusters of chronicity

- “When I feel the worst pain, I look like shit” – body image concerns in persistent pain

- The prevalence of neck-shoulder pain, back pain and psychological symptoms in association with daytime sleepiness – a prospective follow-up study of school children aged 10 to 15

- The neglected role of distress in pain management: qualitative research on a gastrointestinal ward

- Pain mapping of the anterior knee: injured athletes know best

- The role of pain in chronic pain patients’ perception of health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional SQRP study of 40,000 patients

- The DoloTest® in a specialized headache center among patients receiving psychological treatment. A pilot study

- Observational study

- Chronic pelvic pain – pain catastrophizing, pelvic pain and quality of life

- Survey of chronic pain in Chile – prevalence and treatment, impact on mood, daily activities and quality of life

- Patients’ pre-operative general and specific outcome expectations predict postoperative pain and function after total knee and total hip arthroplasties

- The peer effect on pain tolerance

- Original experimental

- The effects of propranolol on heart rate variability and quantitative, mechanistic, pain profiling: a randomized placebo-controlled crossover study

- Idiographic measurement of depressive thinking: development and preliminary validation of the Sentence Completion Test for Chronic Pain (SCP)

- Adding steroids to lidocaine in a therapeutic injection regimen for patients with abdominal pain due to anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome (ACNES): a single blinded randomized clinical trial

- The influence of isometric exercise on endogenous pain modulation: comparing exercise-induced hypoalgesia and offset analgesia in young, active adults

- Do pain-associated contexts increase pain sensitivity? An investigation using virtual reality

- Differences in Swedish and Australian medical student attitudes and beliefs about chronic pain, its management, and the way it is taught

- An experimental investigation of the relationships among race, prayer, and pain

- Educational case report

- Wireless peripheral nerve stimulation for complex regional pain syndrome type I of the upper extremity: a case illustration introducing a novel technology

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial comment

- Diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome

- Body image concerns and distortions in people with persistent pain

- The prevalence of recurrent pain in childhood is high and increases with age

- Friends in pain: pain tolerance in a social network

- Clinical pain research

- Correlation of clinical grading, physical tests and nerve conduction study in carpal tunnel syndrome

- Spectroscopic differences in posterior insula in patients with chronic temporomandibular pain

- Deconstructing chronicity of musculoskeletal pain: intensity-duration relations, minimal dimensions and clusters of chronicity

- “When I feel the worst pain, I look like shit” – body image concerns in persistent pain

- The prevalence of neck-shoulder pain, back pain and psychological symptoms in association with daytime sleepiness – a prospective follow-up study of school children aged 10 to 15

- The neglected role of distress in pain management: qualitative research on a gastrointestinal ward

- Pain mapping of the anterior knee: injured athletes know best

- The role of pain in chronic pain patients’ perception of health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional SQRP study of 40,000 patients

- The DoloTest® in a specialized headache center among patients receiving psychological treatment. A pilot study

- Observational study

- Chronic pelvic pain – pain catastrophizing, pelvic pain and quality of life

- Survey of chronic pain in Chile – prevalence and treatment, impact on mood, daily activities and quality of life

- Patients’ pre-operative general and specific outcome expectations predict postoperative pain and function after total knee and total hip arthroplasties

- The peer effect on pain tolerance

- Original experimental

- The effects of propranolol on heart rate variability and quantitative, mechanistic, pain profiling: a randomized placebo-controlled crossover study

- Idiographic measurement of depressive thinking: development and preliminary validation of the Sentence Completion Test for Chronic Pain (SCP)

- Adding steroids to lidocaine in a therapeutic injection regimen for patients with abdominal pain due to anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome (ACNES): a single blinded randomized clinical trial

- The influence of isometric exercise on endogenous pain modulation: comparing exercise-induced hypoalgesia and offset analgesia in young, active adults

- Do pain-associated contexts increase pain sensitivity? An investigation using virtual reality

- Differences in Swedish and Australian medical student attitudes and beliefs about chronic pain, its management, and the way it is taught

- An experimental investigation of the relationships among race, prayer, and pain

- Educational case report

- Wireless peripheral nerve stimulation for complex regional pain syndrome type I of the upper extremity: a case illustration introducing a novel technology