The prevalence of neck-shoulder pain, back pain and psychological symptoms in association with daytime sleepiness – a prospective follow-up study of school children aged 10 to 15

Abstract

Background and aims

Chronic and recurrent pain is prevalent in adolescents and generally girls report more pain symptoms than boys. Also, pain symptoms and sleep problems often co-occur. Pain symptoms have negative effects on school achievement, emotional well-being, sleep, and overall health and well-being. For effective intervention and prevention there is a need for defining factors associated with pain symptoms and daytime sleepiness. The aim of this longitudinal study was to investigate the prevalence and association between neck-shoulder pain, back pain, psychological symptoms and daytime sleepiness in 10-, 12- and 15-year-old children. This study is the first that followed up the same cohort of children from the age of 10 to 15.

Methods

A cohort study design with three measurement points was used. Participants (n=568) were recruited from an elementary school cohort in a city of 1,75,000 inhabitants in South-Western Finland. Symptoms and daytime sleepiness were measured with self-administered questionnaires. Regression models were used to analyze the associations.

Results

Frequent neck-shoulder pain and back pain, and psychological symptoms, as well as daytime sleepiness, are already common at the age of 10 and increase strongly between the ages 12 and 15. Overall a greater proportion of girls suffered from pain symptoms and daytime sleepiness compared to boys. Daytime sleepiness in all ages associated positively with the frequency of neck-shoulder pain and back pain. The more that daytime sleepiness existed, the more neck-shoulder pain and back pain occurred. Daytime sleepiness at the age of 10 predicted neck-shoulder pain at the age of 15, and back pain at the age of 10 indicated that there would also be back pain at the age of 15. In addition, positive associations between psychological symptoms and neck-shoulder pain, as well as back pain, were observed. Subjects with psychological problems suffered neck-shoulder pain and back pain more frequently.

Conclusions

This study is the first study that has followed up the same cohort of children from the age of 10 to 15. The studied symptoms were all already frequent at the age of 10. An increase mostly happened between the ages of 12 and 15. Moreover, the self-reported daytime sleepiness at the age of 10 predicted neck-shoulder pain at the age of 15. More attention should be paid to the daytime sleepiness of children at an early stage as it has a predictive value for other symptoms later in life.

Implications

School nurses, teachers and parents are in a key position to prevent adolescents’ sleep habits and healthy living habits. Furthermore, the finding that daytime sleepiness predicts neck-shoulder pain later in adolescence suggests that persistent sleep problems in childhood need early identification and treatment. Health care professionals also need take account of other risk factors, such as psychological symptoms and pain symptoms. The early identification and treatment of sleep problems in children might prevent the symptoms’ development later in life. There is a need for an individuals’ interventions to treat adolescents’ sleep problems.

1 Introduction

Chronic and recurrent pain is prevalent in adolescents [1]. The most commonly reported pain symptoms are headaches, musculoskeletal/limb pain and abdominal pain [2]. The prevalence of back pain has been reported to range between 20 and 30% in children and adolescents and the prevalence of back pain increases during school age [3], [4]. The frequency of neck-shoulder pain in adolescents has been estimated to range between 20% and 40% and increases as age increases [5], [6]. Exact estimations of the frequency of psychological symptoms during adolescence are hard to give. Studies have reported that the frequency of mental health problems ranges between 10% to more than 49% [7], [8], [9].

Pain symptoms, especially if they become chronic, have significant negative effects on school achievement, emotional well-being, sleep, and overall health and well-being [10], [11], [12], [13]. Depressive symptoms, little physical activity and more sedentary behavior have been reported to be strongly associated with pain symptoms [6], [14]. It seems that pain symptoms in childhood and adolescence predict later psychiatric disorders, especially anxiety [15]. There is significant co-morbidity with back pain, neck-shoulder pain and psychosocial symptoms [16], [17]. Girls report pain and psychological symptoms more frequently compared to boys, and sex differences in reporting pain and mental health problems become apparent during adolescence [18], [19].

Additionally to pain symptoms, adolescence frequently report sleep-related problems. School children do not encounter the sleep recommendations (WHO study) and increasingly report daytime sleepiness [20]. Daytime sleepiness increases with age in early adolescence [21]. Excessive daytime sleepiness has been reported to be a relative common problem in children (with a prevalence of around 15%) [22] and has been reported to be associated with neurobehavioral (learning and attention) functions, performance in both processing speed and working memory [23], depression [24] and quality of life [25]. Also, different psychosomatic symptoms, sleep problems and pain symptoms, such as neck shoulder pain, often co-occur [26], [27], [28].

There is previous knowledge gained by cross-sectional studies on the frequency of and associations between sleep, pain and psychosocial symptoms, but little attention has been given to studying the effects of daytime sleepiness. There is a need for defining which factors are associated with pain symptoms and daytime sleepiness. The aim of this longitudinal study was to investigate the prevalence of and association between the neck-shoulder pain, back pain, psychological symptoms and daytime sleepiness of girls and boys aged 10, 12 and 15.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Participants and study procedures

Participants were recruited from 31 eligible Finnish-speaking elementary schools in the city of Turku (total population: 1,90,000). There were n=1,097 children participating at the age of 10, 928 at the age of 12 and 568 at the age of 15. The rate of attrition (from baseline to 2nd follow-up) for girls was 36% and for boys 39%. In the drop-out analysis we used data from the age of 10 to compare those who did not complete the questionnaire at age 15 years with those who completed the questionnaire. For both those completing and drop out at age 15 years, there were no statistically significant differences in the amount of sleep, frequency of daytime sleepiness, back pain, and neck-shoulder pain when aged 10 years.

The contact teachers from each school informed the children and their parents about the study. Participation in the study was voluntary. When children and their parents had given a written informed consent to participate, the contact teacher distributed the questionnaires to the participating children during the school day. The questionnaires were filled in using either paper or electronic form (depending on the availability of computers at the schools). Both versions were piloted.

2.2 The questionnaire instruments

To assess sleep, pain and psychosocial symptoms the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) study questionnaire by WHO (www.hbsc.org) was used. The questionnaire has been used in several previous studies [29].

The following questions were used to assess self-reported pain and psychological symptoms: “How often during the preceding 6 months have you had back pain/neck-shoulder pain/depression/irritability or bad temper/nervousness/anxiety/dejection?”. Symptoms were rated on a five-point frequency scale (seldom or never, once a month, once a week, more than once a week, almost daily). In the analysis, symptom frequencies of more than once a week and almost daily were combined and renamed as “frequent”. If at least one of the psychological symptoms (depression/irritability or bad temper/nervousness/anxiety/dejection) occurred at least weekly then we classified child to be symptomatic.

The question used to assess daytime sleepiness was: “How often have you felt tired in the daytime during the last week?” The response alternatives were: not at all, once, twice, several times or daily. For analysis the answers were categorized into two classes: rarely and frequently. Rarely included the responses not at all, once and twice, and frequently included the answers several times and daily.

2.3 Data analysis

Counts and percentages were calculated to describe the data in the tables. The frequency of neck-shoulder pain and back pain was analyzed with four ordinal categories (almost daily and at least once a week as combined and remained as frequent class).

The study goal was to examine whether associations between neck-shoulder pain, daytime sleepiness, gender and psychological symptoms occurred in children aged between 10 and 15 and whether any association changes over time for the same children answering the same questionnaire several times. The same modelling approach was used for back pain and neck-shoulder pain.

In statistical models neck-shoulder pain (assessed by asking the same children at 10, 12 and 15 years of age) was handled as response, and the association with explanatory variables (daytime sleepiness, psychological symptoms and gender) was examined. While the same children were examined at ages 10, 12 and 15, we used ordinal logistic regression for repeated measures analyses techniques to take into account the correlations between measurements (the SAS® GLIMMIX procedure). We also included the interaction between daytime sleepiness and age, gender and age, and psychological symptoms and age, and we wanted to examine whether the associations of these factors changed over time. If a statistically significant effect was found, further contrasts were programmed to find out where the significant differences were. For example, if age had a significant effect, the effect on the measurement taken between the ages 10–12, 10–15 and/or 12–15 was examined.

Also, whether neck-shoulder pain occurring in 15-year-old children had associations with the symptoms or gender differences of 10-year-old children (i.e. whether symptoms can predict neck-shoulder pain for 15-year-old children) was studied. First, univariable analyses were performed with a chi-square test for all children and separately for boys and girls. Associations between neck-shoulder pain at the age of 15 and neck-shoulder pain, psychological symptoms and daytime sleepiness at the age of 10 were studied. After the univariable approach we modelled neck-shoulder pain at 15 years of age, including all these explanatory variables in the same ordinal logistic regression model (the SAS® GLIMMIX procedure). This model was performed for boys and girls separately and also with a model where gender was one factor in the model. In the combined model we also included all interaction with gender.

p-Values less than 0.05 (two-tailed) were considered as statistically significant. The program used for statistical analysis was SAS® System, version 9.3 and 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

2.4 Ethical issues

The study follows the national legislation (Medical Research Act 488/1999) and the general guidelines of research ethics (TENK 2004). The ethical commission of the Hospital District of Southwest Finland has approved the study (8/2004/232). The participants received both oral and written information about the study; they had time to consider their participation and knew about their right to withdraw from the study at any time. Both the guardians and children gave a written informed consent to participate.

3 Results

3.1 Neck-shoulder pain, back pain and daytime sleepiness prevalence

The prevalence of weekly or more frequent neck-shoulder pain in children of the ages 10 and 12 was 20% (see Table 1). For 15-year-olds the prevalence had increased to 32% (F2=11.04, p<0.0001). For girls the prevalence of weekly or more frequent neck-shoulder pain at the age of 15 was 41% and for boys it was 20% (F2=5.6, p=0.0040). Overall, a greater proportion of girls compared to boys suffered from at least weekly neck-shoulder pain in all age groups (F1=16.11, p<0.0001). A more detailed description can be found in Table 1.

The prevalence numbers of neck-shoulder pain and back pain at the ages of 10, 12 and 15.

| Age | 10 years |

12 years |

15 years |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequent n (%) | Weekly n (%) | Once at month n (%) | Rarely or never n (%) | Frequent n (%) | Weekly n (%) | Once at month n (%) | Rarely or never n (%) | Frequent n (%) | Weekly n (%) | Once at month n (%) | Rarely or never n (%) | |

| Neck-shoulder pain | ||||||||||||

| All | 71 (9) | 88 (11) | 223 (27) | 442 (54) | 62 (7) | 110 (13) | 284 (34) | 384 (46) | 62 (12) | 108 (20) | 173 (33) | 189 (36) |

| – Girls | 40 (9) | 51 (12) | 116 (27) | 222 (52) | 42 (10) | 67 (15) | 141 (32) | 191 (43) | 47 (16) | 73 (25) | 98 (34) | 71 (25) |

| – Boys | 31 (8) | 37 (9) | 107 (27) | 220 (56) | 20 (5) | 43 (11) | 143 (36) | 193 (48) | 15 (6) | 35 (14) | 75 (31) | 118 (49) |

| Back pain | ||||||||||||

| All | 34 (4) | 56 (7) | 135 (16) | 598 (73) | 52 (6) | 41 (5) | 145 (17) | 597 (72) | 43 (8) | 66 (12) | 161 (30) | 263 (49) |

| – Girls | 19 (4) | 29 (7) | 61 (14) | 320 (75) | 33 (7) | 56 (6) | 70 (16) | 313 (71) | 32 (11) | 36 (12) | 91 (31) | 130 (45) |

| – Boys | 15 (4) | 27 (7) | 74 (19) | 278 (71) | 19 (5) | 16 (4) | 75 (19) | 284 (72) | 11 (5) | 30 (12) | 70 (29) | 133 (55) |

Frequent back pain at the ages of 10 and 12 was 11%, and at the age of 15 it was 20% (F2=17.7, p<0.0001) (see Table 1). There were no differences between girls and boys in back pain (F1=0.04, p=0.84). Furthermore, changes in back pain over time did not differ significantly between boys and girls (gender×time interaction: F2=1.37, p=0.25).

The daytime sleepiness of children occurring at least several times a week was on average 13% at the ages of 10 and 12, and 24% at the age of 15. There was a clear increase in daytime sleepiness at the age of 15 compared to 10 and 12 years of age (p<0.0001). The increase between age 12 and 15 was greater in girls compared to boys (p<0.0001). The results of the frequency of daytime sleepiness are seen in Table 2.

Daytime sleepiness categorized by five category (not at all, once, twice, several times/week and daily) at ages 10, 12 and 15.

| Daytime sleepiness | 10 years Girls n=467 Boys n=439 n (%) |

12 years Girls n=475 Boys n=453 n (%) |

15 years Girls n=300 Boys n=268 n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily | |||

| Girls | 8 (2) | 8 (2) | 14 (5) |

| Boys | 4 (1) | 12 (3) | 7 (3) |

| Several times/week | |||

| Girls | 57 (12) | 51 (11) | 78 (26) |

| Boys | 48 (11) | 48 (11) | 37 (14) |

| Twice/week | |||

| Girls | 119 (25) | 136 (29) | 99 (33) |

| Boys | 99 (23) | 115 (25) | 70 (26) |

| Once/week | |||

| Girls | 144 (31) | 174 (37) | 76 (25) |

| Boys | 142 (32) | 153 (34) | 93 (35) |

| Not at all | |||

| Girls | 117 (25) | 96 (20) | 27 (9) |

| Boys | 116 (26) | 104 (23) | 52 (19) |

3.2 Explanatory variables which associated generally to neck-shoulder pain and back pain over the study follow-up

We also wanted to study the association between daytime sleepiness and neck-shoulder pain, as well as back pain. Overall, daytime sleepiness in all ages associated positively with the frequency of neck-shoulder pain (F4=13.62, p<0.0001) and back pain (F4=14.62, p<0.0001). The more that daytime sleepiness existed, the more neck-shoulder pain and back pain occurred (see Table 3).

The association between frequency of daytime sleepiness and neck-shoulder pain or back pain at the age of 10, 12 and 15.

| Age 10 years Daytime sleepiness |

Age 12 years Daytime sleepiness |

Age 15 years Daytime sleepiness |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Every day n (%) |

Several times n (%) |

Two times n (%) |

Once n (%) |

Not at all n (%) |

Every day n (%) |

Several times n (%) |

Two times n (%) |

Once n (%) |

Not at all n (%) |

Every day n (%) |

Several time n (%) |

Two times n (%) |

Once n (%) |

Not at all n (%) |

|

| Neck-shoulder pain | |||||||||||||||

| Frequent | 2 (17) | 22 (22) | 24 (11) | 16 (6) | 11 (5) | 8 (40) | 19 (20) | 19 (8) | 14 (4) | 3 (2) | 7 (33) | 23 (20) | 18 (11) | 11 (7) | 5 (6) |

| Weekly | 2 (17) | 18 (16) | 29 (13) | 26 (9) | 14 (6) | 5 (25) | 24 (26) | 35 (15) | 35 (11) | 15 (8) | 6 (29) | 28 (25) | 36 (22) | 27 (16) | 13 (17) |

| Once a month | 2 (17) | 30 (38) | 61 (28) | 83 (30) | 49 (22) | 3 (15) | 28 (30) | 91 (38) | 110 (35) | 54 (29) | 3 (14) | 31 (28) | 68 (41) | 61 (37) | 11 (14) |

| Rarely or never | 6 (50) | 31 (38) | 103 (48) | 154 (55) | 150 (67) | 4 (20) | 22 (24) | 94 (39) | 155 (50) | 115 (61) | 5 (24) | 30 (27) | 44 (26) | 65 (40) | 50 (63) |

| Back pain | |||||||||||||||

| Frequent | 3 (25) | 13 (13) | 8 (4) | 5 (2) | 6 (3) | 6 (30) | 17 (18) | 12 (5) | 12 (4) | 5 (3) | 6 (29) | 16 (14) | 12 (7) | 6 (4) | 5 (6) |

| Weekly | 2 (17) | 14 (14) | 17 (8) | 19 (7) | 7 (3) | 1 (5) | 11 (12) | 14 (6) | 11 (4) | 5 (3) | 4 (19) | 16 (14) | 25 (15) | 17 (10) | 5 (6) |

| Once a month | 1 (8) | 22 (22) | 43 (20) | 47 (17) | 23 (10) | 4 (20) | 25 (27) | 51 (22) | 48 (15) | 20 (11) | 6 (29) | 34 (30) | 56 (34) | 57 (35) | 10 (13) |

| Rarely or never | 6 (50) | 52 (51) | 147 (68) | 207 (74) | 190 (84) | 9 (45) | 40 (43) | 160 (67) | 239 (77) | 158 (84) | 5 (24) | 47 (42) | 73 (44) | 84 (51) | 59 (75) |

In addition, positive associations between psychological symptoms and neck-shoulder pain (F1=186.8, p<0.0001), as well as back pain (F1=149.1, p<0.0001), were observed; subjects with psychological problems suffered from neck-shoulder pain and back pain more frequently. These associations did not change over time (neck-shoulder pain: F2=0.27, p=0.77; back pain: F2=0.28, p=0.76).

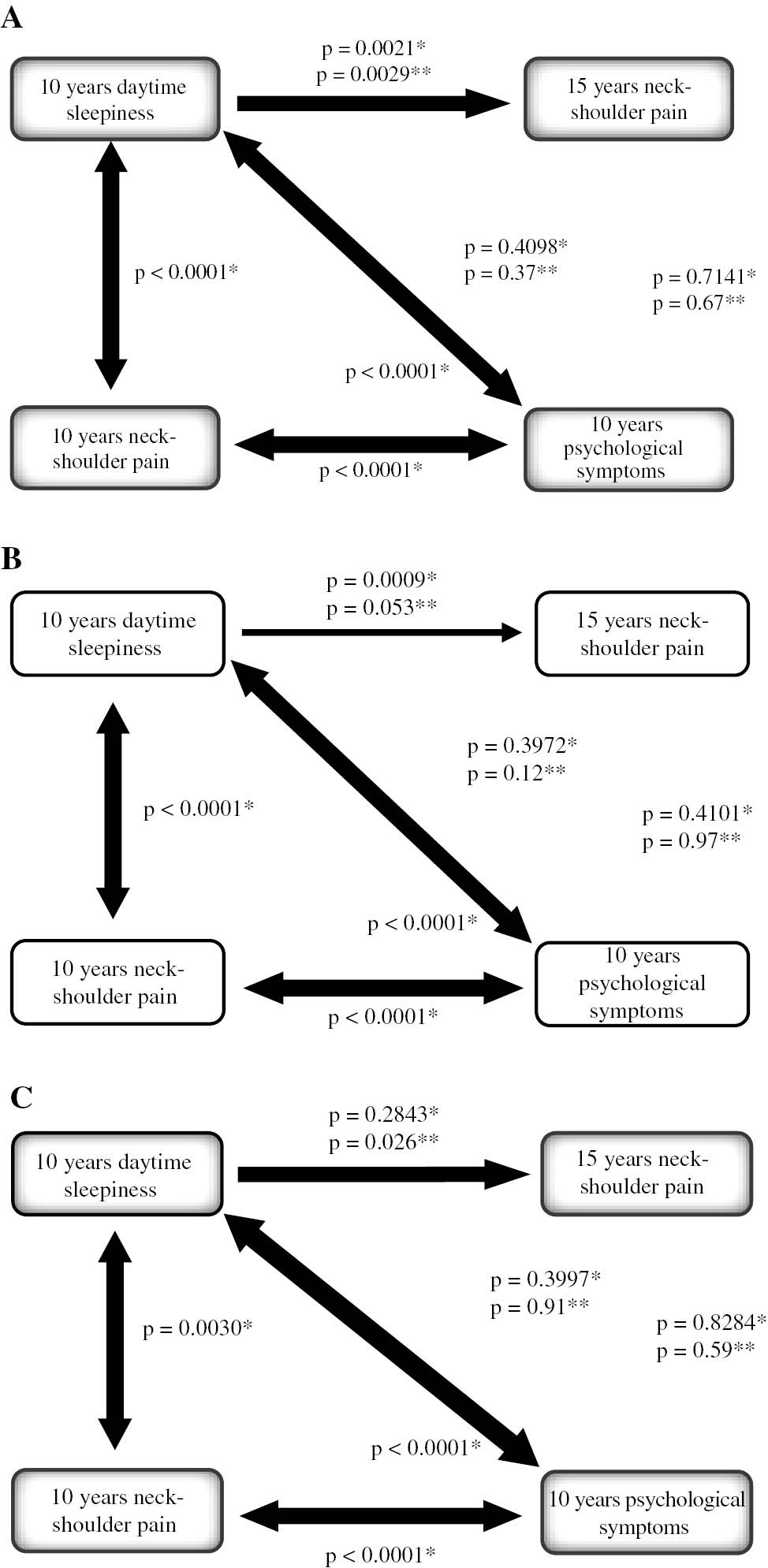

Univariable analysis showed significant association between daytime sleepiness, neck-shoulder pain and psychological symptoms at 10 years of age. The multivariable analysis between the ages of 10 and 15 revealed that only the daytime sleepiness of children at the age of 10 predicted neck-shoulder pain at the age of 15 (p=0.0029; Fig. 1A). At the age of 10 daytime sleepiness and psychological symptoms were strongly associated with neck-shoulder pain, but only daytime sleepiness (p=0.0029) at the age of 10 could predict neck-shoulder pain at the age of 15. Furthermore, this model was seen for boys (p=0.026) (Fig. 1C) but it was only indicative for girls (p=0.053) (Fig. 1B).

The association between daytime sleepiness, a neck-shoulder pain and psychological symptoms at the ages of 10 and 15. (p-value with *, from univariable model and p-value with **, from multivariable model). 1A: All children. 1B: Girls. 1C: Boys.

3.3 Predictors for neck-shoulder pain and back pain occurred at 15-year old children

We also wanted to build a predictive model. We stated with univariable analysis between back pain, daytime sleepiness and psychological symptoms at 10 years of age, and back pain at 15 years of age (Fig. 2A). Univariable analysis also showed significant association between daytime sleepiness, back pain and psychological symptoms at 10 years of age (Fig. 2A). Multivariable ordinal logistic regression analysis showed that the predictive association of back pain suffered when 10 years old was statistically significantly different between girls and boys (p=0.0060). Girls had a significant association of back pain when 10 years old and when 15 years old (p=0.0004) (Fig. 2B), whereas the association for boys was not statistically significant (p=0.076) (Fig. 2C). In a multivariate model neither daytime sleepiness nor psychological symptoms significantly predicted back pain at 15 years old.

The association between daytime sleepiness, back pain and psychological symptoms at the ages of 10 and 15. (p-value with *, from univariable model and p-value with **, from multivariable model). 2A: All children. 2B: Girls. 2C: Boys.

4 Discussion

Our findings revealed that frequent neck-shoulder pain, back pain and psychological symptoms, as well as daytime sleepiness, are already common at the age of 10 and increase strongly between the ages 12 and 15. The symptoms also tend to co-occur in the same individuals and co-occurrence of the symptoms. Our results are in line with previous studies suggesting significant co-morbity, e.g. between different type of symptoms being associated with headache [30], sleep problems [28], behavioral factors and psychological symptoms [16], [19], [31]. Additionally to finding co-occurrence, we also found associations and predictability between different symptoms. Back pain at age 10 indicated back pain at age 15 and daytime sleepiness at the age of 10 predicted neck-shoulder pain at the age of 15.

Our results on gender specific differences in frequency and co-occurrence of symptoms are also in line with previous research [28], [32].

At schools the role of school health professionals is to support healthy living habits that include issues related to sleep, physical activity and general healthy lifestyles. Moreover, the early detection of sleep-related problems, as well as symptoms, is essential as early care brings better results and prevents symptoms from becoming chronic [33]. School health professionals should be aware of the phenomena of daytime sleepiness and that symptoms tend to co-occur. When one symptom is detected there may also be additional psychosocial symptoms and other symptoms that need to be targeted. Therefore when treating individual symptoms in children we should always have a more holistic approach.

Since children already have pain, psychological symptoms and daytime sleepiness at the age of 10, they need targeted interventions that are aimed at preventing these. Teachers and other professionals at school can support children’s wellbeing at school by offering opportunities for physical exercise during and between classes [34]. Daytime sleepiness is more difficult to handle at school. However, education about sleep hygiene, daily rhythm and their connection to circadian rhythm could be offered. Since girls report more daytime sleepiness than boys, interventions should be targeted separately to them [35]. Children should be actively heard regarding what kind of activities they are interested in. The sports offered at school might not be the ones that children are interested in. Physical activity promotion strategies should target children with a low level of activity in particular [36].

The curricula at schools vary between countries but quite often physical training is included in the curricula. According to the results of this and several previous studies, there is also a need for lectures related to social and emotional well-being [37], [38]. Also, emotional intelligence can be learned [39].

It is not only health professionals who should be interested in children’s health and well-being. Teachers can also support healthy living habits. They could integrate health issues into basic lectures, such as mathematics, chemistry, physics, languages, etc. When problems occur, teachers should know where to seek for help for children and adolescents and guide them to the services.

At home, parents are important role models for their children and should try to support healthy sleeping, as well as other healthy living habits, with their behavior. Moreover, parents and family members should pay attention to possible symptoms at an early stage, know the health care service system and search for support when needed. Parents should be able to discriminate normal, occasional symptoms from those that need to be effectively targeted. It is also important for parents to be aware of how their children and adolescents spend their free time in regard to hobbies and friends [40].

Our study indicated that neck-shoulder pain at the age of 10 predicted pain at 15. Also, the frequency of symptoms increased strongly between the ages of 12 and 15. This is a time when several developmental things occur (such as puberty and changes in the social lives of adolescents). Interventions concerning sleep habits and pain should start as early as possible. Adolescents should be competent in choosing healthy living habits and have knowledge of health-related issues. They should also be aware of how to detect ill health in themselves as well as in their friends. They need to know the basics about social and health services and where and how to seek for help if needed.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study is the research design: a prospective follow-up of one age cohort consisting of a large sample size. Also, the follow-up time for the same children of 5 years – from pre-adolescence to adolescent years – is unique and additionally provides some predictive data to the description. As the data was collected during school hours and as schools have been reported to be good research settings (as basically all children attend school), the results present a very wide range of social backgrounds and a heterogeneous group of youth. Methodologically, the use of the HBSC study questions also supports the validity of the results of this study. The HBSC questionnaire has previously been widely used and reported to be acceptable for test-retest validity and stability [41].

Some limitations need to be considered when interpreting the findings. The assessment of the pain symptoms was only performed with adolescents’ self-reported data and did not include any diagnostic assessments. The drop out was fairly large during the follow-up time. The drop out was mainly caused by uncontrollable factors, such as children moving location or being absent from school at the study time. However, the drop-out analysis shows that there was no significant difference between the baseline results and the participants dropping out and those not dropping out.

5 Conclusions

This study is the first study that has followed up the same cohort of children from the age of 10 to 15. The studied symptoms were all already frequent at the age of 10. The increases mostly happened between the ages of 12 and 15. Moreover, the self-reported daytime sleepiness at the age of 10 predicted neck-shoulder pain at the age of 15. More attention should be paid to the daytime sleepiness of children at an early stage as it has a predictive value for other symptoms later in life.

6 Implications

School nurses, teachers and parents are in a key position to prevent adolescents’ sleep habits and healthy living habits. Many adolescents and their parents do not understand the impact of good sleep habits on health outcomes. Furthermore, the finding that daytime sleepiness predicts neck-shoulder pain later in adolescence suggests that persistent sleep problems in childhood need early identification and treatment. Health care professionals also need take account of other risk factors, such as psychological symptoms and pain symptoms. The early identification and treatment of sleep problems in children might prevent the symptoms’ development later in life. There is a need for an individuals’ interventions to treat adolescents’ sleep problems.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank all the study participants of the Schools on the Move research project.

-

Authors’ statements

-

Research funding: This study was partly funded by The University of Turku and Juho Vainio Foundation.

-

Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

-

Informed consent: Both the guardians and children gave a written informed consent to participate.

-

Ethical approval: The study follows the national legislation (Medical Research Act 488/1999) and the general guidelines of research ethics (TENK 2004). The ethical commission of the Hospital District of Southwest Finland has approved the study (8/2004/232).

References

[1] King S, Chambers CT, Huguet A, MacNevin RC, McGrath PJ, Parker L, MacDonald AJ. The epidemiology of chronic pain in children and adolescents revisited: a systematic review. Pain 2011;152:2729–38.10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.016Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Fichtel A, Larsson B. Psychosocial impact of headache and comorbidity with other pains among swedish school adolescents. Headache 2002;42:766–75.10.1046/j.1526-4610.2002.02178.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] van Gessel H, Gassmann J, Kröner-Herwig B. Children in pain: recurrent back pain, abdominal pain, and headache in children and adolescents in a four-year-period. J Pediatr 2011;158:977–83.10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.11.051Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Stanford EA, Chambers CT, Biesanz JC, Chen E. The frequency, trajectories and predictors of adolescent recurrent pain: A population-based approach. Pain 2008;138:11–21.10.1016/j.pain.2007.10.032Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Hogg-Johnson S, van der Velde G, Caroll LJ, Holm LW, Cassidy JD, Guzman J, Cote P, Haldeman S, Carragee E, Hurwitz E, Nordin M, Peloso P. The burden and determinants of neck pain in the general population: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine 2008;33:39–51.10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816454c8Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Myrtveit SM, Sivertsen B, Skogen JC, Frostholm L, Stormark KM, Hysing M. Adolescent neck and shoulder pain – the association with depression, physical activity, screen-based activities, and use of health care services. J Adolesc Health 2014;55:366–72.10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.02.016Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:837–44.10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Sawyer MG, Arney FM, Baghurst PA, Clark JJ, Graetz BW, Kosky RJ, Nurcombe B, Patton GC, Prior MR, Raphael B, Rey J, Whaites LC, Zubrick SR. The mental health of young people in Australia: key findings from the child and adolescent component of the national survey of mental health and well-being. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2001;35:806–14.10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00964.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Bronsard G, Alessandrini M, Fond G, Loundou A, Pascal Auquier, Tordjman S, Boyer L. The prevalence of mental disorders among children and adolescents in the child welfare system: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2016;95:e2622.10.1097/MD.0000000000002622Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Forgeron P, King S. Social functioning and peer relationships in children and adolescents with chronic pain: a systematic review. Pain Res Manag 2010;15:27–41.10.1155/2010/820407Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Ramchandani PG, Hotopf M, Sandhu B, Stein A. The epidemiology of recurrent abdominal pain from 2 to 6 years of age: Results of a large, population-based study. Pediatrics 2005;116:46–50.10.1542/peds.2004-1854Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Watson KD, Papageorgiou AC, Jones GT, Taylor S, Symmons DPM, Silman AJ, Macfarlane GJ. Low back pain in schoolchildren: the role of mechanical and psychosocial factors. Arch Dis Child 2003;88:12–7.10.1136/adc.88.1.12Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Oddson BE, Clancy CA, McGrath PJ. The role of pain in reduced quality of life and depressive symptomology in children with spina bifida. Clin J Pain 2006;22:784–9.10.1097/01.ajp.0000210929.43192.5dSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Lahey BB, Rathouz PJ, Van Hulle C, Urbano RC, Krueger RF, Applegate B, Garriock HA, Chapman DA, Waldman ID. Testing structural models of DSM-IV symptoms of common forms of child and adolescent psychopathology. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2008;36:187–206.10.1007/s10802-007-9169-5Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Gregory AM, Caspi A, Eley TC, Moffitt TE, Oconnor TG, Poulton R. Prospective longitudinal associations between persistent sleep problems in childhood and anxiety and depression disorders in adulthood. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2005;33:157–63.10.1007/s10802-005-1824-0Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Adamson G, Murphy S, Shevlin M, Buckle P, Stubbs D. Profiling schoolchildren in pain and associated demographic and behavioural factors: a latent class approach. Pain 2007;129:295–303.10.1016/j.pain.2006.10.015Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Vikat A, Rimpelä M, Salminen JJ, Rimpelä A, Savolainen A, Virtanen SM. Neck or shoulder pain and low back pain in Finnish adolescents. Scand J Public Health 2000;28:164–73.10.1177/14034948000280030401Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Roth-Isigkeit A, Thyen U, Raspe HH, Stöven H, Schmucker P. Reports of pain among German children and adolescents: An epidemiological study. Acta Paediatr 2004;93:258–63.10.1111/j.1651-2227.2004.tb00717.xSuche in Google Scholar

[19] Rees CS, Smith AJ, O’Sullivan PB, Kendall GE, Straker LM. Back and neck pain are related to mental health problems in adolescence. BMC Public Health 2011;25:382.10.1186/1471-2458-11-382Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Millman R, Working Group on Sleepiness in Adolescents/Young Adults, AAP Committee on Adolescence. Excessive sleepiness in adolescents and young adults: causes, consequences, and treatment strategies. Pediatrics 2005;115:1777–86.10.1542/peds.2005-0772Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Campbell IG, Burright CS, Kraus AM, Grimm KJ, Feinberg I. Daytime sleepiness increases with age in early adolescence: a sleep restriction dose–response study. Sleep 2017;40. DOI:10.1093/sleep/zsx046.10.1093/sleep/zsx046Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Calhoun SL, Vgontzas AN, Fernandez-Mendoza J, Mayes SD, Tsaoussoglou T, Basta M, Bixler EO. Prevalence and risk factors of excessive daytime sleepiness in a community sample of young children: the role of obesity, asthma, anxiety/depression, and sleep. Sleep 2011;34:503–7.10.1093/sleep/34.4.503Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Calhoun SL, Fernandez-Mendoza J, Vgontzas AN, Mayes SD, Tsaoussoglou M, Rodriguez-Muñoz A, Bixler EO. Learning, attention/hyperactivity, and conduct problems as sequelae of excessive daytime sleepiness in a general population study of young children. Sleep 2012;35:627–32.10.5665/sleep.1818Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Stein MA, Mendelsohn J, Obermeyer WH, Amromin J, Benca R. Sleep and behavior problems in school-aged children. Pediatrics 2001;107:e60.10.1542/peds.107.4.e60Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Gustafsson M-L, Laaksonen C, Aromaa M, Asanti R, Heinonen O, Koski P, Koivusilta L, Löyttyniemi E, Suominen S, Salanterä S. Association between amount of sleep, daytime sleepiness and health-related quality of life in schoolchildren. J Adv Nurs 2016;72:1263–72.10.1111/jan.12911Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Luntamo T, Sourander A, Rihko M, Aromaa M, Helenius H, Koskelainen M, McGrath PJ. Psychosocial determinants of headache, abdominal pain, and sleep problems in a community sample of Finnish adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012;21:301–13.10.1007/s00787-012-0261-1Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Brun Sundblad G, Saartok T, Engström L-MT. Prevalence and co-occurrence of self-rated pain and perceived health in school-children: age and gender differences. Eur J Pain 2007;11:171–80.10.1016/j.ejpain.2006.02.006Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Valrie CR, Bromberg MH, Palermo T, Schanberg LE. A systematic review of sleep in pediatric pain populations. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2013;34:120–8.10.1097/DBP.0b013e31827d5848Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Pallesen S, Hetland J, Sivertsen B, Samdal O, Torsheim T, Nordhus IH. Time trends in sleep-onset difficulties among Norwegian adolescents: 1983–2005. Scand J Public Health 2008;36:889–95.10.1177/1403494808095953Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Landgraf MN, von Kries R, Heinen F, Langhagen T, Straube A, Albers L. Self-reported neck and shoulder pain in adolescents is associated with episodic and chronic migraine. Cephalalgia 2016;36:807–11.10.1177/0333102415610875Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Wiklund M, Malmgren-Olsson EB, Öhman A, Bergström E, Fjellman-Wiklund A. Subjective health complaints in older adolescents are related to perceived stress, anxiety and gender – a cross-sectional school study in Northern Sweden. BMC Public Health 2012;12:993.10.1186/1471-2458-12-993Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Hakala P, Rimpelä A, Salminen JJ, Virtanen SM, Rimpelä M. Back, neck, and shoulder pain in Finnish adolescents: national cross sectional surveys. Br Med J 2002;325:743.10.1136/bmj.325.7367.743Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Kronholm E, Puusniekka R, Jokela J, Villberg J, Urrila AS, Paunio T, Välimaa R, Tynjälä J. Trends in self-reported sleep problems, tiredness and related school performance among Finnish adolescents from 1984 to 2011. J Sleep Res 2015;24:3–10.10.1111/jsr.12258Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Weaver RG, Webster CA, Egan C, Campos CMC, Michael RD, Vazou S. Partnerships for active children in elementary schools: Outcomes of a 2-year pilot study to increase physical activity during the school day. Am J Health Promot 2018;32:621–30.10.1177/0890117117707289Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Galland BC, Gray AR, Penno J, Smith C, Lobb C, Taylor RW. Gender differences in sleep hygiene practices and sleep quality in New Zealand adolescents aged 15 to 17 years. Sleep Health 2017;3:77–83.10.1016/j.sleh.2017.02.001Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Fairclough S, Hackett A, Davies I, Gobbi R, Mackintosh K, Warburton G, Stratton G, Sluijs E, Boddy L. Promoting healthy weight in primary school children through physical activity and nutrition education: a pragmatic evaluation of the CHANGE! randomised intervention study. BMC Public Health 2013;13:626.10.1186/1471-2458-13-626Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Chung S, McBride A. Social and emotional learning in middle school curricula: a service learning model based on positive youth development. Child Youth Serv Rev 2015;53:192–200.10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.04.008Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Durlak J, Weissberg R, Dymnicki A, Taylor R, Schellinger K. The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Dev 2011;82:405–32.10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Veltro F, Ialenti V, Morales García MA, Iannone C, Bonanni E, Gigantesco A. Evaluation of the impact of the new version of a handbook to promote psychological wellbeing and emotional intelligence in the schools (students aged 12–15). Riv Psichiatr 2015;50:71–9.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Voss, C, Sandercock, GRH. Associations between perceived parental physical activity and aerobic fitness in schoolchildren. J Phys Act Health 2013;10:397–9.10.1123/jpah.10.3.397Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Liu Y, Wang M, Tynjälä J, Yan Lv, Villberg J, Zhang Z, Kannas L. Test-retest reliability of selected items of Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) survey questionnaire in Beijing, China. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010;10:73.10.1186/1471-2288-10-73Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

©2018 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain. Published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston. All rights reserved.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial comment

- Diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome

- Body image concerns and distortions in people with persistent pain

- The prevalence of recurrent pain in childhood is high and increases with age

- Friends in pain: pain tolerance in a social network

- Clinical pain research

- Correlation of clinical grading, physical tests and nerve conduction study in carpal tunnel syndrome

- Spectroscopic differences in posterior insula in patients with chronic temporomandibular pain

- Deconstructing chronicity of musculoskeletal pain: intensity-duration relations, minimal dimensions and clusters of chronicity

- “When I feel the worst pain, I look like shit” – body image concerns in persistent pain

- The prevalence of neck-shoulder pain, back pain and psychological symptoms in association with daytime sleepiness – a prospective follow-up study of school children aged 10 to 15

- The neglected role of distress in pain management: qualitative research on a gastrointestinal ward

- Pain mapping of the anterior knee: injured athletes know best

- The role of pain in chronic pain patients’ perception of health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional SQRP study of 40,000 patients

- The DoloTest® in a specialized headache center among patients receiving psychological treatment. A pilot study

- Observational study

- Chronic pelvic pain – pain catastrophizing, pelvic pain and quality of life

- Survey of chronic pain in Chile – prevalence and treatment, impact on mood, daily activities and quality of life

- Patients’ pre-operative general and specific outcome expectations predict postoperative pain and function after total knee and total hip arthroplasties

- The peer effect on pain tolerance

- Original experimental

- The effects of propranolol on heart rate variability and quantitative, mechanistic, pain profiling: a randomized placebo-controlled crossover study

- Idiographic measurement of depressive thinking: development and preliminary validation of the Sentence Completion Test for Chronic Pain (SCP)

- Adding steroids to lidocaine in a therapeutic injection regimen for patients with abdominal pain due to anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome (ACNES): a single blinded randomized clinical trial

- The influence of isometric exercise on endogenous pain modulation: comparing exercise-induced hypoalgesia and offset analgesia in young, active adults

- Do pain-associated contexts increase pain sensitivity? An investigation using virtual reality

- Differences in Swedish and Australian medical student attitudes and beliefs about chronic pain, its management, and the way it is taught

- An experimental investigation of the relationships among race, prayer, and pain

- Educational case report

- Wireless peripheral nerve stimulation for complex regional pain syndrome type I of the upper extremity: a case illustration introducing a novel technology

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial comment

- Diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome

- Body image concerns and distortions in people with persistent pain

- The prevalence of recurrent pain in childhood is high and increases with age

- Friends in pain: pain tolerance in a social network

- Clinical pain research

- Correlation of clinical grading, physical tests and nerve conduction study in carpal tunnel syndrome

- Spectroscopic differences in posterior insula in patients with chronic temporomandibular pain

- Deconstructing chronicity of musculoskeletal pain: intensity-duration relations, minimal dimensions and clusters of chronicity

- “When I feel the worst pain, I look like shit” – body image concerns in persistent pain

- The prevalence of neck-shoulder pain, back pain and psychological symptoms in association with daytime sleepiness – a prospective follow-up study of school children aged 10 to 15

- The neglected role of distress in pain management: qualitative research on a gastrointestinal ward

- Pain mapping of the anterior knee: injured athletes know best

- The role of pain in chronic pain patients’ perception of health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional SQRP study of 40,000 patients

- The DoloTest® in a specialized headache center among patients receiving psychological treatment. A pilot study

- Observational study

- Chronic pelvic pain – pain catastrophizing, pelvic pain and quality of life

- Survey of chronic pain in Chile – prevalence and treatment, impact on mood, daily activities and quality of life

- Patients’ pre-operative general and specific outcome expectations predict postoperative pain and function after total knee and total hip arthroplasties

- The peer effect on pain tolerance

- Original experimental

- The effects of propranolol on heart rate variability and quantitative, mechanistic, pain profiling: a randomized placebo-controlled crossover study

- Idiographic measurement of depressive thinking: development and preliminary validation of the Sentence Completion Test for Chronic Pain (SCP)

- Adding steroids to lidocaine in a therapeutic injection regimen for patients with abdominal pain due to anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome (ACNES): a single blinded randomized clinical trial

- The influence of isometric exercise on endogenous pain modulation: comparing exercise-induced hypoalgesia and offset analgesia in young, active adults

- Do pain-associated contexts increase pain sensitivity? An investigation using virtual reality

- Differences in Swedish and Australian medical student attitudes and beliefs about chronic pain, its management, and the way it is taught

- An experimental investigation of the relationships among race, prayer, and pain

- Educational case report

- Wireless peripheral nerve stimulation for complex regional pain syndrome type I of the upper extremity: a case illustration introducing a novel technology