The DoloTest® in a specialized headache center among patients receiving psychological treatment. A pilot study

-

Marianne Kromann Nielsen

, Maria Lurenda Westergaard

Abstract

Background

The DoloTest is a newer health-related quality of life (HRQoL) monitoring instrument for pain, not yet validated for headache.

Aims

To examine the usefulness of the DoloTest in a specialized headache center.

Methods

The sample consisted of patients referred to psychologists from the Danish Headache Center (DHC) for whom the test was carried out at start of, end of, and 6 months after treatment. Points on eight scales of the test were measured (values ranged from 0 to 100), then totaled (0 to 800). Scores were analyzed using Wilcoxon Signed Ranks test. The correlation between headache days and DoloTest scores were computed using linear regression adjusted for age. Qualitative feedback on usefulness of the test were gathered from psychologists.

Results

Of 135 patients included, 105 completed treatment. On average, headache days decreased from 22 days per month at start of treatment (SD 9.0, median 29) to 18 days at end of treatment (SD 10.8, median 19) (p<0.001). At end of treatment, DoloTest scores improved for pain (p=0.015) and reduced energy and strength (p=0.034). At 6 months’ follow-up, total scores improved (p=0.034), as well as component scores for pain (p=0.010), problems with strenuous activity (p=0.045) and reduced energy and strength (p=0.012). Correlation between reduced headache days and improved DoloTest scores was 0.303 (p=0.028). Psychologists found the test useful in monitoring and evaluating patients.

Conclusions

The DoloTest was useful for psychoeducation and for monitoring the effect of headache treatment.

Implications

The DoloTest is a potential HRQoL monitoring instrument for headache patients. We recommend further validation studies.

1 Introduction

Headaches are highly prevalent, debilitating and associated with substantial reduction in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7].

In the clinical setting, it is important to monitor patients’ progress in order to evaluate effectiveness of interventions. In headache frequently used disability instruments are MIDAS [8], HIT-6 [9] and HURT [10], the latter by Buse et al. 2012 is published as review of several useful instruments for documenting headache impact and reduction in HRQoL, but there is still a need for instruments that are easy to fill in and interpret directly in order to monitor and evaluate headache treatment.

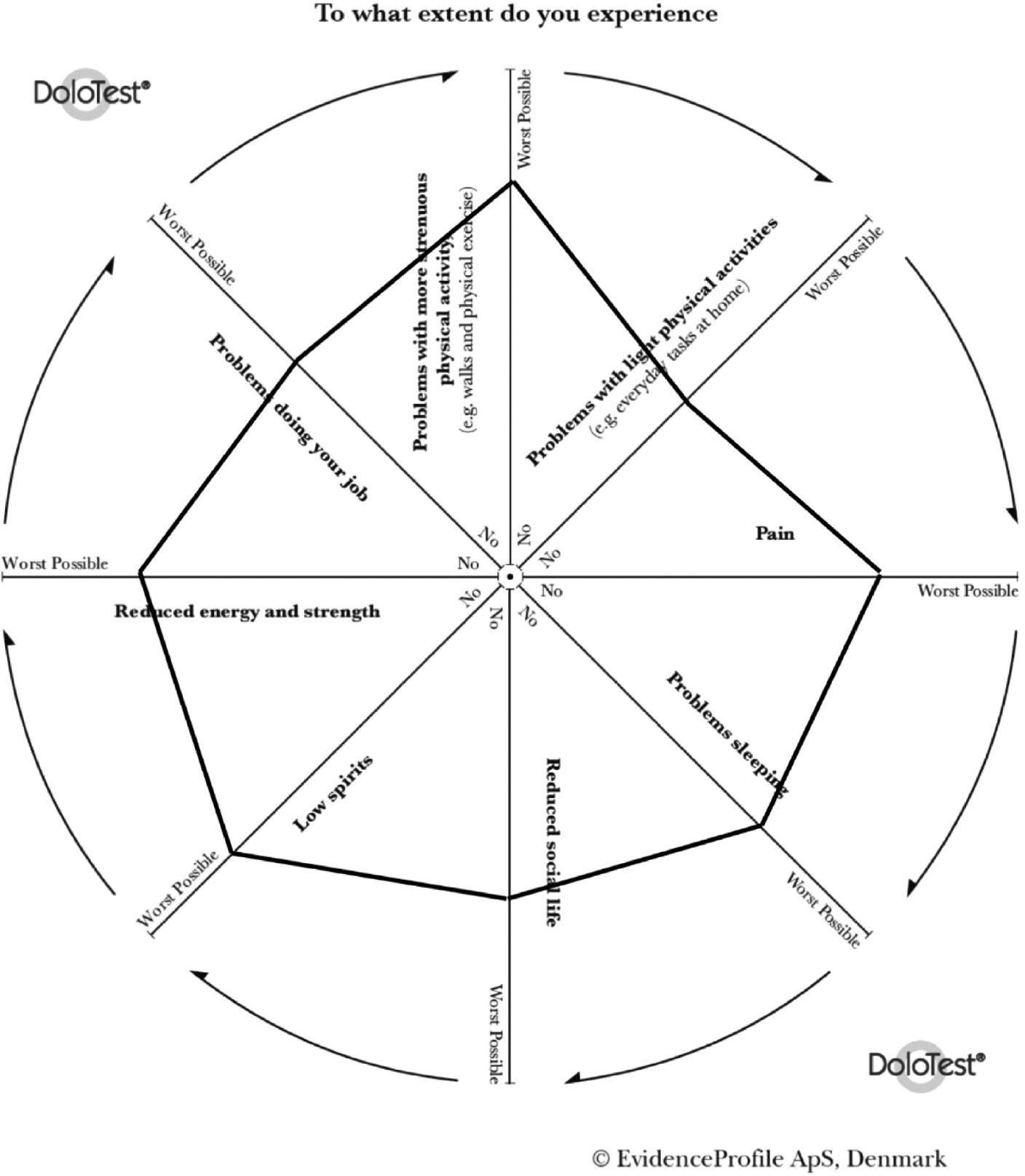

In this paper we look into the DoloTest, which is a newer self-administered tool for monitoring and evaluating HRQoL in adult patients with constant nociceptive pain [11]. It is a generic instrument, and is not specific for headache. It has not previously been applied to patients with headache in a specialty care setting. The DoloTest uses eight domains assessed on visual analog scales (VAS) (Fig. 1). The points representing the patient’s responses for each of the scales are connected, producing a visual representation of HRQoL and impact of illness.

DoloTest showing an example of a patient score (bold line) on the eight domains at one time point.

The figure is published with written permission from EvidenceProfile ApS, Denmark.

The DoloTest has characteristics that may prove advantageous in a clinical setting. VAS have high reliability and validity [12], [13]. The test can be completed in about 1 min and 49 s [11], and it requires little training to do so. The visual presentation of results can be evaluated by the patient and the therapist together, making the test a patient educational tool as well. The DoloTest can also be used by patients with mild cognitive impairment [14].

The DoloTest has been validated against 30 of the 36 parameters of the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form Surveys (SF-36) [15] in patients with persistent, stable, nociceptive pain [11].

The overall aim of this project was to investigate if the DoloTest is a useful instrument that psychologists in a specialized headache center can use for educating and monitoring their patients. This was done by examining DoloTest results at start of, at end of and 6 months after multidisciplinary treatment; by evaluating correlation between DoloTest scores and headache days; and by gathering qualitative feedback from psychologists on usefulness of the DoloTest.

We hypothesized that the psychologists would be able to quickly interpret the results and use these for patient education and monitoring. We further hypothesized reduction in test scores at the end of treatment, and that reduction in headache days is strongly correlated with improvement in the eight domains of the DoloTest.

The effectiveness of specific psychological interventions was not evaluated.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

All patients referred to the Danish Headache Center (DHC) who were offered psychological assessment at any time in the period from January 2012 to December 2012 were recruited to the study. The DHC is a tertiary headache center and receives patients with facial pain and headache from all over Denmark. Patients were referred directly from general practitioners or from neurologists.

2.1.1 Inclusion criteria

Presence of an active headache disorder as described in the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-II); age 18 years or older; and acceptance of the treatment plan which included evaluation by a psychologist.

2.1.2 Exclusion criteria

Medication-overuse headache according to the ICHD-II criteria; geographical, linguistic or physical problems that made it difficult for the patient to be present in sessions with a psychologist; refusal to participate in the psychological intervention offered; severe depression or other severe psychopathology, these patients were referred directly to a psychiatrist since their psychiatric condition was prioritized higher than stress and pain management.

Physicians interviewed the patients and performed neurological and general examinations. Data were gathered on age, sex, marital status, educational attainment, employment status and headache frequency. Physicians identified primary and secondary headache diagnoses and assessed the relevance of referring the patient for evaluation by a psychologist. Patients who were first seen by junior physicians were always conferred with senior specialists.

Patients referred to psychological evaluation were then interviewed by psychologists trained in headache management. The psychologists then decided whether a specific psychological intervention was relevant for the patient, and this was offered as part of the treatment plan. There were five types of psychological interventions: (1) stress and pain management, nine sessions; (2) mindfulness, nine sessions, (3) youth group therapy, 10 sessions, (4) group session for patients with post-traumatic headache, nine sessions and (4) individual therapy, which consisted of stress and pain management one-to-one for up to 12 sessions.

2.2 DoloTest

The DoloTest consists of eight domains (Fig. 1); pain severity; problems sleeping; reduced social life; low spirit; reduced energy and strength; problems doing your job; problems with more strenuous physical activity; and problems with light physical activities. Patients were asked to score an average for each domain the past week. All domains were presented graphically. A sum score was computed from the scores for each domain.

2.3 Treatment plan, follow-up and testing

All patients who participated in this project received the usual multidisciplinary treatment offered at the DHC. Treatment plans consisted of different combinations of interventions: use of acute and preventive medications for headache, psychological interventions, physiotherapy, and health education.

Psychologists educated patients about the relationship between debilitating headache and mental health (psychoeducation). Psychologists aimed to assist patients on stress and energy management; to become more aware of thoughts, feelings and bodily sensations related to headache pain; and to accept and work through limitations posed by chronic illness.

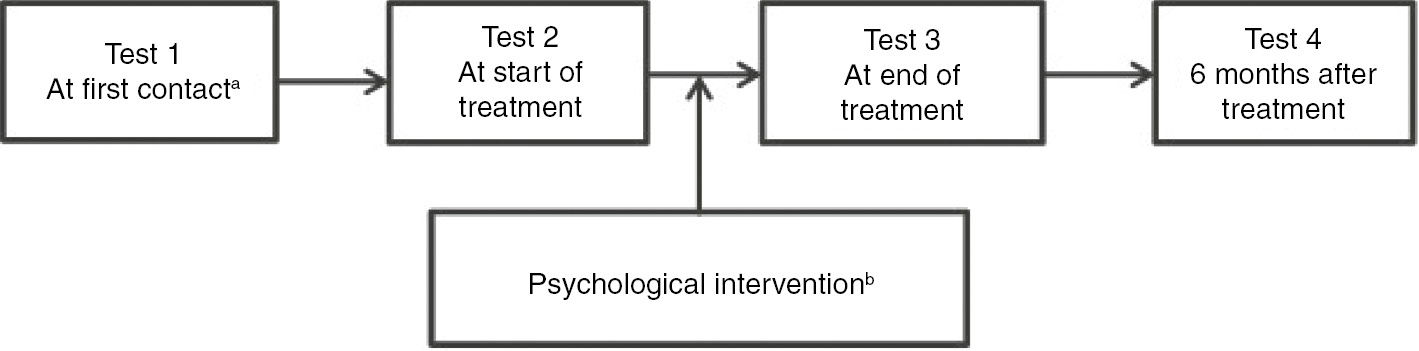

The DoloTest was filled in four times; the first three times at the DHC and administered by psychologists, the last time by the patient at home (Fig. 2).

Flowchart showing follow-up of patients referred for psychological interventions, and periods when the DoloTest was administered. aPatients were interviewed and evaluated by a psychologist and psychological treatment was offered if this was deemed relevant. bThe appropriate intervention was selected by the psychologists according to their evaluation of the patients.

The test was filled in on paper. The points on the lines were connected by the psychologist to produce a graphic presentation of the test result. The patients did not have access to previous results when they filled in the test a second, third or fourth time. Previous results were shown only after the patient completed the new questionnaire.

2.4 Qualitative evaluation

Four psychologists qualitatively evaluated the DoloTest in terms of ease of implementation, usefulness as a patient educational tool, and usefulness for evaluating patient progress over time. Their evaluation was based on a structured interview first on an individual basis and then in a group format.

2.5 Statistical analyses

Age data were summarized as means and standard deviations. All other demographic data were summarized as proportions per category. Headache frequency was summarized in two ways: number of headache days per month and presence of chronic headache. In this study chronic headache is defined as headache present 15 or more days per month in the last 3 months.

Demographic characteristics and headache diagnoses of completers and non-completers were compared using t-test (for age), χ2 test (for categorical variables), or Fisher’s exact test (for variables where expected counts in 50% or more categories were less than five). p-Values were two-tailed and considered significant if below 0.05.

Points on each of the eight scales of the DoloTest were measured and assigned a value from 0 to 100. These scores were then added up to a total score ranging from 0 to 800. A higher score indicated more severe disability or reduction in quality of life. The scores at start of treatment, end of treatment, and 6 months after treatment were compared using Wilcoxon Signed Ranks test for related samples. This non-parametric test was used instead of the paired t-test because the observations were not normally distributed.

Correlation between headache days and DoloTest scores were analyzed using linear regression.

All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 22.

3 Results

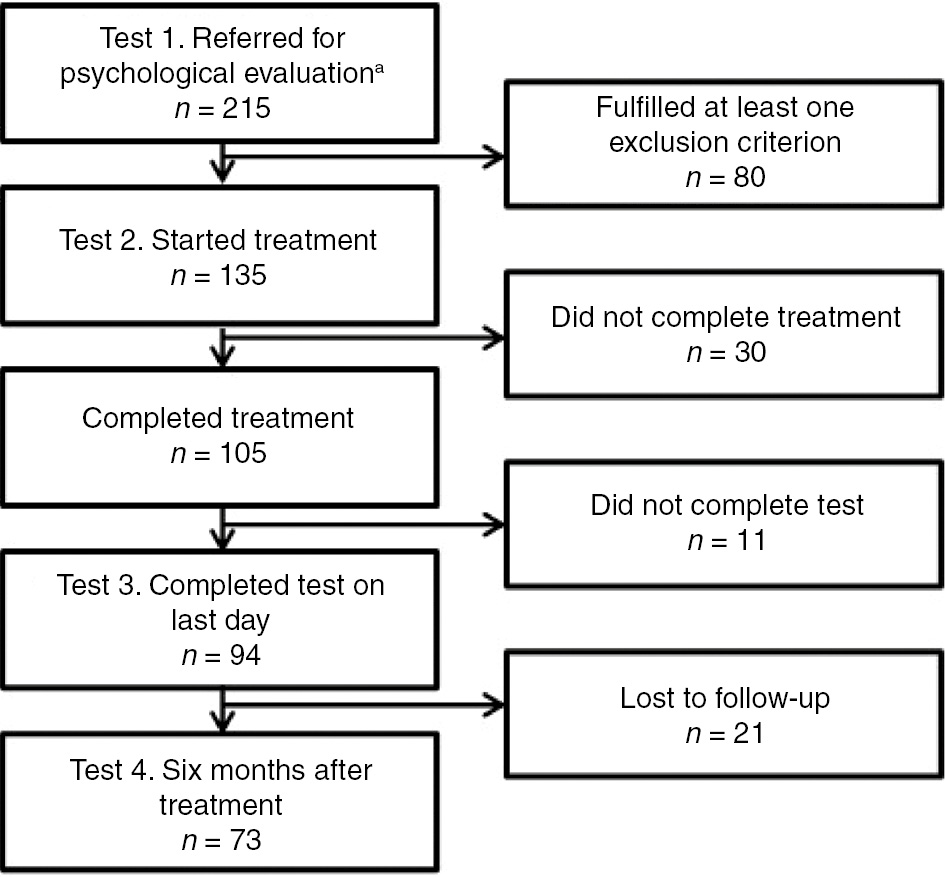

A total of 215 patients were evaluated by four psychologists. Among the 215 patients, 135 were found eligible for psychological treatment and accepted the treatment plan. Of the 135 who started, 105 (78%) completed the treatment with three or fewer missed sessions (Fig. 3). The patients’ demographic characteristics and headache diagnoses are shown on Table 1. There were no significant differences between the 105 completers and 30 non-completers in terms of demographic characteristics and headache diagnoses (p>0.05).

Flowchart showing inclusion of patients, number treated and number available for follow-up.

Characteristics of study participants by age, sex, marital status, educational attainment, employment status and headache diagnosis.

| Patients referred for evaluation (n=215) |

Patients who started treatment (n=135) |

Patients who completed treatment (n=105) |

Completers vs. non-completers p-Valuea |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 37.5 (11.8) | 38.8 (11.4) | 38.9 (11.7) | 0.933 |

| Range in years | 18–69 | 18–69 | 18–69 | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.068 | |||

| Female | 173 (80.5) | 112 (83.0) | 84 (80.0) | |

| Male | 42 (19.5) | 23 (17.0) | 21 (20.0) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.834 | |||

| Unmarried | 54 (25.1) | 27 (20.0) | 22 (21.0) | |

| Married, cohabitants | 144 (67.0) | 96 (71.1) | 75 (71.4) | |

| Divorced/separated/widow/widower | 15 (7.0) | 11 (8.1) | 8 (7.6) | |

| No data | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.7) | – | |

| Basic education, n (%) | 0.881 | |||

| Lower secondary school | 19 (8.8) | 9 (6.7) | 7 (6.7) | |

| Vocational or technical school | 42 (19.5) | 26 (19.3) | 21 (20.0) | |

| General upper secondary school | 141 (65.6) | 92 (68.1) | 70 (66.7) | |

| Other | 13 (6.0) | 8 (5.9) | 7 (6.7) | |

| Higher education, n (%) | 0.584 | |||

| No further education | 47 (21.9) | 21 (15.6) | 18 (17.1) | |

| Skilled works | 65 (30.2) | 47 (34.8) | 35 (33.3) | |

| Professional bachelor or academy profession programs | 55 (25.6) | 36 (26.7) | 26 (24.8) | |

| University graduate student | 35 (16.3) | 25 (18.5) | 21 (20.0) | |

| Special type of workers | 7 (3.3) | 2 (1.5) | 2 (1.9) | |

| No data | 6 (2.8) | 4 (3.0) | 3 (2.9) | |

| Employment status, n (%) | 0.353 | |||

| Full time (≥32 h/week) | 101 (47.0) | 61 (45.2) | 47 (44.8) | |

| Part time (<32 h/week) | 20 (9.3) | 15 (11.1) | 12 (11.4) | |

| Part time special conditions (>2 h/week) | 11 (5.1) | 9 (6.7) | 7 (6.7) | |

| Unemployed | 14 (6.5) | 10 (7.4) | 9 (8.6) | |

| Sick leave | 46 (21.4) | 27 (20.0) | 22 (21.0) | |

| Early pension | 11 (5.1) | 6 (4.4) | 4 (3.8) | |

| Pension | 2 (0.9) | 2 (1.5) | 2 (1.9) | |

| Other (maternity/paternity, training) | 10 (0.5) | 5 (3.7) | 2 (2.0) | |

| Headache type, with some patients having more than one type, n (%) | ||||

| Migraine without aura | 99 (46.0) | 65 (48.1) | 50 (47.6) | 0.818 |

| Migraine with aura | 22 (15.3) | 19 (14.1) | 14 (13.3) | 0.643 |

| Chronic TTH | 92 (42.8) | 57 (42.2) | 46 (43.8) | 0.485 |

| Frequent episodic TTH | 41 (19.1) | 28 (20.7) | 22 (21.0) | 0.910 |

| Post-traumatic headache | 39 (18.1) | 23 (17.0) | 16 (15.2) | 0.298 |

| Prior medication-overuse headache | 22 (10.2) | 16 (11.9) | 12 (11.4) | 0.776 |

| Trigeminal neuralgia | 10 (4.7) | 5 (3.7) | 3 (2.9) | 0.308 |

| Cluster headache | 7 (3.3) | 6 (4.4) | 6 (5.7) | 0.338 |

| Idiopathic intracranial hypertension | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.0) | 1.000 |

| Other | 6 (2.8) | 4 (3.0) | 3 (2.9) | 1.000 |

| Chronic headache, ≥15 days per month, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 160 (74.4) | 104 (77.0) | 81 (77.1) | 0.956 |

| No | 55 (25.6) | 31 (23.0) | 24 (22.9) |

-

SD=standard deviation; TTH=tension-type headache. ap-Values refer to comparisons between 105 patients who completed the treatment and 30 patients who did not. All p-values for demographic data are from χ2 tests, except for comparisons of mean age (t-test). For the headache diagnoses, Fisher’s exact tests were used for trigeminal neuralgia, cluster headache, idiopathic intracranial hypertension and other headaches.

3.1 Implementation of the DoloTest

The DoloTest was administered to 185 patients referred for psychological treatment (Test 1) and to 135 at start of treatment (Test 2). Of the 105 completers, 94 (90%) filled in the DoloTest at end of treatment (Test 3) and 73 (70%) responded 6 months after treatment (Test 4) (Fig. 3).

3.2 Qualitative feedback from psychologists

In the structured interview the psychologists all reported that they found it easy to explain the scope of the test to patients and to register results. They observed that it was easy and quick for the patients to fill in the test, and all patients were able to do so correctly.

The psychologists reported that patients found the DoloTest useful in depicting their actual state of health and headache. The visual analog scales made it possible for patients to describe their situation both quantitatively (marking the line) as well as qualitatively (go into detail with examples from daily life). The psychologists were immediately able to help patients interpret the results for the past week, and to focus on possible future interventions. The graphical output made it easier for the psychologists to monitor changes in HRQoL, and to educate patients in terms of progression and relapse.

The psychologists observed that most patients experienced large fluctuations in their headache duration, frequency and intensity and therefore found it difficult to give a score for the 1-week evaluation period.

3.3 Reduction in headache days

At the start of treatment, 135 patients reported an average of 22 headache days per month (SD 9.1, median 30, range 2–30 days/month). Among the 105 who completed treatment, the average headache frequency dropped significantly from 22 to 18 days per month (SD 10.8, median 19, p<0.001). There was a further drop after 6 months from end of treatment to 17 days per month (SD 10.8, median 17), though this was not significant (p=0.443).

3.4 DoloTest scores

All domains in the DoloTest scores decreased at end of treatment, although improvement was significant only in relation to pain (p=0.015) and reduced energy and strength (p=0.034) (Table 2). Six months after treatment, there was a significant improvement in total scores from 364 to 333 points (p=0.034) and in the following domains: pain (p=0.010), problems with strenuous activity (p=0.045) and reduced energy and strength (p=0.012) (Table 2).

DoloTest scores at start of treatment, at end of treatment and 6 months after treatment.

| Test 2a At start of treatment (n=105) |

Test 3 At end of treatment (n=94) |

Start vs. end of treatment |

Test 4 6 months after treatment (n=73) |

Start vs. 6 months after treatment |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median, Mean (SD) | Median, Mean (SD) | p-Value | Median, Mean (SD) | p-Value | |

| Total score | 364 | 341 | 0.104 | 333 | 0.034b |

| 367.4 (144.8) | 343.3 (141.5) | 338.0 (131.0) | |||

| Pain | 59 | 51 | 0.015b | 44 | 0.010b |

| 54.8 (22.4) | 49.8 (22.8) | 47.6 (23.0) | |||

| Problems with light activity | 32 | 35 | 0.583 | 31 | 0.154 |

| 36.6 (25.1) | 36.3 (24.1) | 34.0 (23.1) | |||

| Problems with strenuous activity | 49 | 43.5 | 0.488 | 41 | 0.045b |

| 47.6 (28.7) | 45.4 (29.0) | 42.2 (25.7) | |||

| Problems with doing your job | 26 | 23.5 | 0.567 | 30 | 0.494 |

| 31.5 (29.9) | 30.6 (29.3) | 31.3 (29.1) | |||

| Reduced energy and strength | 61 | 56 | 0.034b | 51 | 0.012b |

| 58.0 (22.0) | 54.0 (22.4) | 51.8 (20.1) | |||

| Low spirit | 49 | 40 | 0.123 | 38 | 0.110 |

| 47.8 (23.8) | 42.6 (22.9) | 42.3 (20.4) | |||

| Reduced social life | 51 | 42 | 0.059 | 52 | 0.724 |

| 48.9 (24.5) | 43.4 (23.8) | 48.9 (23.2) | |||

| Problems sleeping | 41 | 42.5 | 0.811 | 41 | 0.816 |

| 42.1 (30.7) | 41.4 (28.2) | 39.7 (22.6) |

-

aOnly data from patients who completed the treatment is included. bp-Values<0.05 were considered significant. Higher scores refer to greater disability or reduction in quality of life. p-Values refer to Wilcoxon Signed Ranks tests comparing scores at start of treatment with scores at end of treatment and 6 months after treatment.

3.5 Relationship between reduction in headache days and improvement in DoloTest scores

A large number of patients still had chronic headaches after treatment. There was no significant difference in the proportion of patients suffering from chronic headache at start of and at end of treatment (77.1% and 78.7%). Linear regression models were created using reduction in DoloTest score as the outcome variable, and reduction in headache days as the explanatory variable (Table 3). R-squared values were low (below 10%). The coefficients were significant for total score, pain, problems with strenuous activity, reduced energy and strength and reduced social life (p<0.05). The coefficient for reduced energy and strength was not significant once adjusted for age.

Correlation between reduction in headache days and reduction in DoloTest scores (total and per domain) from start to end of treatment, adjusted for age.

| Ra | R-squaredb | Coefficientc | p-Valued | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: univariate analysis | ||||

| Total score | 0.294 | 0.087 | 5.667 | 0.012e |

| Pain | 0.289 | 0.084 | 0.890 | 0.014e |

| Problems with light activity | 0.225 | 0.051 | 0.772 | 0.057 |

| Problems with strenuous activity | 0.289 | 0.084 | 1.031 | 0.014e |

| Problems with doing your job | 0.109 | 0.012 | 0.440 | 0.361 |

| Reduced energy and strength | 0.280 | 0.078 | 0.922 | 0.017e |

| Low spirit | 0.110 | 0.012 | 0.358 | 0.356 |

| Reduced social life | 0.234 | 0.055 | 0.778 | 0.048e |

| Problems sleeping | 0.146 | 0.021 | 0.476 | 0.221 |

| Model 2: adjusted for age | ||||

| Total score | 0.303 | 0.092 | 5.214 | 0.028e |

| Pain | 0.290 | 0.084 | 0.871 | 0.022e |

| Problems with light activity | 0.231 | 0.053 | 0.716 | 0.095 |

| Problems with strenuous activity | 0.292 | 0.085 | 0.990 | 0.025e |

| Problems with doing your job | 0.157 | 0.025 | 0.295 | 0.560 |

| Reduced energy and strength | 0.318 | 0.101 | 0.761 | 0.058 |

| Low spirit | 0.160 | 0.026 | 0.237 | 0.560 |

| Reduced social life | 0.249 | 0.062 | 0.871 | 0.036e |

| Problems sleeping | 0.146 | 0.021 | 0.473 | 0.250 |

-

aR is the correlation between observed and predicted values of the DoloTest score. bR-squared is the proportion of the variance in the reduction of each DoloTest score which can be explained by reduction in headache days. This is a measure of the strength of association between a positive effect of treatment (reduction in headache days) and an improvement in the test score. cFor every unit reduction in headache days, there is a corresponding reduction in the DoloTest score as shown by the unstandardized coefficient. dp-Values refer to the coefficient being significantly different from 0. ep-Values<0.05 were considered significant.

4 Discussion

In this study, we examined the DoloTest in a specialized headache center. We found it was useful as a patient education tool, and as a treatment monitoring tool in the clinical setting.

According to the psychologists the test was easy to administer, fill in and score. The patients easily understood how to use the test and reported that the test made it easier to verbalize their daily problems. However, many patients experienced large fluctuations in their headache duration, frequency and intensity. As a consequence, a 1-week evaluation period might not be representative. A longer evaluation period might have been more appropriate and simultaneous use of a calendar or diary may thus assist here. The psychologists found the test useful as a psychoeducational and therapeutic tool. The scores and visual representations of change, or lack thereof, were discussed in the group sessions to give participants opportunities to reflect upon any changes, their life situation, and the outcome of treatment. These discussions likely contributed to the participants’ understanding and acceptance of how fluctuations in pain and quality of life are often tightly correlated.

We found that improvement in headache days corresponded to improvement in total DoloTest score, as well as scores in several domains. However, the correlations were not very strong. A possible explanation is the relatively limited sample size. Many patients in the sample were refractory to medical treatment, and only small reductions in headache days and/or HRQoL could be expected. The sample’s headache frequency was skewed towards the highest score (30 days per month). The sample may therefore represent a population that was more severely affected than the population for which the DoloTest was originally developed. Certain HRQoL domains; problems with doing your job, low spirit and problems sleeping, do not appear to be strongly correlated with a reduction in headache days. Those domains could be associated with social problems, depression or other psychopathology, and sleep disorders and may therefore be less useful in the monitoring of headaches. We hypothesize that psychological interventions gave patients strategies for how to function despite their illness, thereby improving their quality of life scores, despite no reduction in headache days.

Total test scores appear to be normally distributed, suggesting that there are no floor or ceiling effects where a high proportion of the sample has extreme values. It is not possible to compare with data from the general population because “normal” values have not yet been established for the DoloTest. In general, however, the “ideal” score can be regarded as being as close as possible to zero. For the individual patient, the goal is for the eight-sided polygon to become smaller over time. These changes may not be statistically significant but could represent clinical importance for the patients.

4.1 Strengths and limitations of the instrument

The main strength of the DoloTest is that it is easy to translate scores into a graphical image that patients and health care personnel can easily interpret and understand. It can be filled in within 1–2 min. The scoring is not complex. Data can be summarized as a continuous variable, and requires only addition to compute a total score. Scores can then be used to quantify HRQoL visually and document change over time for specific domains. In contrast to other HRQoL instruments, the DoloTest includes a domain about sleep problems which is highly relevant for headache patients [16].

The main limitation of the test is that it has not been validated for headache disorders and that the criterion validity was not tested in the present pilot study only in patients with nociceptive pain [11]. The test was designed to monitor patients with nociceptive pain in general, and was not designed to be sensitive to the specific burden of headaches. The test period only includes the last week. A longer evaluation period is preferred for headache monitoring and evaluation.

DoloTest is copyrighted and a license must be purchased prior to use. This could present a limitation for larger scale implementation in many centers.

4.2 Prospects for future research

Among this group of patients with medically refractory and frequent headaches, it may have been more useful to monitor not just headache days but also headache intensity and duration. This would likely allow for a better description of patients’ disability and impairment. Analysis using compound parameters as Area under the Headache Curve (Intensity×Duration) or Headache Indexes have been proposed [17], [18]. These data should be gathered in future studies.

The present study was a feasibility study to test the clinical acceptability for patients and psychologists. A proper validation against other headache disability instruments such as MIDAS [8], HIT-6 [9] and HURT [10] are recommended in future studies.

The eight domains are considered equally important, but some patients with headache may rank some domains as being more important than others. This could also be explored in future studies.

The DoloTest has now been developed as an app for mobile devices. Applicability of this app for headache or other chronic pain should be examined.

5 Conclusion

Our study shows that the DoloTest is easy to implement in clinical headache practice. It is easy to score and interpret. It has good face validity and tracks changes over time although correlation between scores and headache days is weak for this group of patients referred to tertiary care. The test may be useful for psychologists and likely other members of the multidisciplinary team in psychoeducation, and in evaluating treatment effectiveness.

5.1 Clinical implications

The DoloTest is a newer HRQoL measurement instrument for pain patients. The instrument is not yet validated for headache patients, but may prove useful in the clinical setting.

The test is easy for patients to understand and complete. Psychologists found test results useful for psychoeducation.

The test is useful for multimodal monitoring of effect of headache treatment.

Further validation studies are recommended.

-

Authors’ statements

-

Research funding: No external funding has been given to this project.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest of relevance to this project.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

-

Ethical approval: As a service and quality improvement project, the project fell outside the scope of research ethics review in Denmark. The DoloTest was part of the standard evaluation procedure carried out by psychologists at the Danish Headache Center. All central person registry (CPR) numbers were replaced with project identification codes (numbers and letters) to ensure anonymity. Only one psychologist (DKN) had access to all the patients’ CPR numbers. Two authors (MLW and MKN) had access to raw data in anonymized form during statistical analysis.

Permission was granted by EvidenceProfile ApS, Denmark to use the DoloTest at the DHC for a trial period. EvidenceProfile ApS, Denmark did not receive any data from the project, and did not have any influence on the decision to publish results of the study. Neither the DHC nor the authors received monetary compensation from EvidenceProfile ApS, Denmark.

References

[1] Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Lipton R, Scher A, Steiner T, Zwart JA. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia 2007;27:193–210.10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01288.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Stovner LJ, Andrée C. Impact of headache in Europe: a review for the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain 2010;11:289–99.10.1007/s10194-010-0217-0Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Guitera V, Muñoz P, Castillo J, Pascual J. Quality of life in chronic daily headache: a study in a general population. Neurology 2002;58:1062–5.10.1212/WNL.58.7.1062Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Duru G, Auray JP, Gaudin AF, Dartigues JF, Henry P, Lantéri-Minet M, Lucas C, Pradalier A, Chazot G, El Hasnaoui A. Impact of headache on quality of life in a general population survey in France (GRIM2000 Study). Headache 2004;44:571–80.10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.446005.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Terwindt GM, Ferrari MD, Tijhuis M, Groenen SM, Picavet HS, Launer LJ. The impact of migraine on quality of life in the general population: the GEM study. Neurology 2000;55:624–9.10.1212/WNL.55.5.624Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Milde-Busch A, Heinrich S, Thomas S, Kühnlein A, Radon K, Straube A, Bayer O, von Kries R. Quality of life in adolescents with headache: results from a population-based survey. Cephalalgia 2010;30:713–21.10.1177/0333102409354389Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Blumenfeld AM, Varon SF, Wilcox TK, Buse DC, Kawata AK, Manack A, Goadsby PJ, Lipton RB. Disability, HRQoL and resource use among chronic and episodic migraineurs: results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). Cephalalgia 2011;31:301–15.10.1177/0333102410381145Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Kolodner KB, Sawyer J, Lee C, Liberman JN. Validity of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) score in comparison to a diary-based measure in a population sample of migraine suffers. Pain 2000;88:41–52.10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00305-5Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, Bjorner JB, Ware JE Jr, Garber WH, Batenhorst A, Cady R, Dahlöf CG, Dowson A, Tepper S. A six-item short-form survey for measuring headache impact: the HIT-6. Qual Life Res 2003;12:963–74.10.1023/A:1026119331193Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Buse DC, Sollars CM, Steiner TJ, Jensen RH, Al Jumah MA, Lipton RB. Why HURT? A review of clinical instruments for headache management. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2012;16:237–54.10.1007/s11916-012-0263-1Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Kristiansen K, Lyngholm-Kjaerby P, Moe C. Introduction and validation of DoloTest(®): a new health-related quality of life tool used in pain patients. Pain Pract 2010;10:396–403.10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00366.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Grossman S, Sheidler V, McGuire D. A comparison of the Hopkins Pain Rating instrument with standard visual analogue and verbal descriptor scales in patients with cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage 1992;7:196–203.10.1016/0885-3924(92)90075-SSuche in Google Scholar

[13] Jensen MP, Karoly P. Self-report scales and procedures for assessing pain in adults. In: Turk DC, Melzack R, editors. Handbook of Pain Assessment. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press, 2001:15–34.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Kristiansen K, Shafiei R, Lyngholm-Kjaerby P, Moe C. Dolotest® and cognitive dysfunction: a study of use and understanding. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:2430–2.10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03165.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–83.10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Lund N, Westergaard ML, Barloese M, Glümer C, Jensen RH. Epidemiology of concurrent headache and sleep problems in Denmark. Cephalalgia 2014;34:833–45.10.1177/0333102414543332Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Silberstein S, Tfelt-Hansen P, Dodick DW, Limmroth V, Lipton RB, Pascual J, Wang SJ; Task Force of the International Headache Society Clinical Trials Subcommittee. Guidelines for controlled trials of prophylactic treatment of chronic migraine in adults. Cephalalgia 2008;28:484–95.10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01555.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Bendtsen L, Bigal ME, Cerbo R, Diener HC, Holroyd K, Lampl C, Mitsikostas DD, Steiner TJ, Tfelt-Hansen P; International Headache Society Clinical Trials Subcommittee. Guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in tension-type headache: second edition. Cephalagia 2010;30:1–16.10.1111/j.1468-2982.2009.01948.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

©2018 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain. Published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston. All rights reserved

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial comment

- Diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome

- Body image concerns and distortions in people with persistent pain

- The prevalence of recurrent pain in childhood is high and increases with age

- Friends in pain: pain tolerance in a social network

- Clinical pain research

- Correlation of clinical grading, physical tests and nerve conduction study in carpal tunnel syndrome

- Spectroscopic differences in posterior insula in patients with chronic temporomandibular pain

- Deconstructing chronicity of musculoskeletal pain: intensity-duration relations, minimal dimensions and clusters of chronicity

- “When I feel the worst pain, I look like shit” – body image concerns in persistent pain

- The prevalence of neck-shoulder pain, back pain and psychological symptoms in association with daytime sleepiness – a prospective follow-up study of school children aged 10 to 15

- The neglected role of distress in pain management: qualitative research on a gastrointestinal ward

- Pain mapping of the anterior knee: injured athletes know best

- The role of pain in chronic pain patients’ perception of health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional SQRP study of 40,000 patients

- The DoloTest® in a specialized headache center among patients receiving psychological treatment. A pilot study

- Observational study

- Chronic pelvic pain – pain catastrophizing, pelvic pain and quality of life

- Survey of chronic pain in Chile – prevalence and treatment, impact on mood, daily activities and quality of life

- Patients’ pre-operative general and specific outcome expectations predict postoperative pain and function after total knee and total hip arthroplasties

- The peer effect on pain tolerance

- Original experimental

- The effects of propranolol on heart rate variability and quantitative, mechanistic, pain profiling: a randomized placebo-controlled crossover study

- Idiographic measurement of depressive thinking: development and preliminary validation of the Sentence Completion Test for Chronic Pain (SCP)

- Adding steroids to lidocaine in a therapeutic injection regimen for patients with abdominal pain due to anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome (ACNES): a single blinded randomized clinical trial

- The influence of isometric exercise on endogenous pain modulation: comparing exercise-induced hypoalgesia and offset analgesia in young, active adults

- Do pain-associated contexts increase pain sensitivity? An investigation using virtual reality

- Differences in Swedish and Australian medical student attitudes and beliefs about chronic pain, its management, and the way it is taught

- An experimental investigation of the relationships among race, prayer, and pain

- Educational case report

- Wireless peripheral nerve stimulation for complex regional pain syndrome type I of the upper extremity: a case illustration introducing a novel technology

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial comment

- Diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome

- Body image concerns and distortions in people with persistent pain

- The prevalence of recurrent pain in childhood is high and increases with age

- Friends in pain: pain tolerance in a social network

- Clinical pain research

- Correlation of clinical grading, physical tests and nerve conduction study in carpal tunnel syndrome

- Spectroscopic differences in posterior insula in patients with chronic temporomandibular pain

- Deconstructing chronicity of musculoskeletal pain: intensity-duration relations, minimal dimensions and clusters of chronicity

- “When I feel the worst pain, I look like shit” – body image concerns in persistent pain

- The prevalence of neck-shoulder pain, back pain and psychological symptoms in association with daytime sleepiness – a prospective follow-up study of school children aged 10 to 15

- The neglected role of distress in pain management: qualitative research on a gastrointestinal ward

- Pain mapping of the anterior knee: injured athletes know best

- The role of pain in chronic pain patients’ perception of health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional SQRP study of 40,000 patients

- The DoloTest® in a specialized headache center among patients receiving psychological treatment. A pilot study

- Observational study

- Chronic pelvic pain – pain catastrophizing, pelvic pain and quality of life

- Survey of chronic pain in Chile – prevalence and treatment, impact on mood, daily activities and quality of life

- Patients’ pre-operative general and specific outcome expectations predict postoperative pain and function after total knee and total hip arthroplasties

- The peer effect on pain tolerance

- Original experimental

- The effects of propranolol on heart rate variability and quantitative, mechanistic, pain profiling: a randomized placebo-controlled crossover study

- Idiographic measurement of depressive thinking: development and preliminary validation of the Sentence Completion Test for Chronic Pain (SCP)

- Adding steroids to lidocaine in a therapeutic injection regimen for patients with abdominal pain due to anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome (ACNES): a single blinded randomized clinical trial

- The influence of isometric exercise on endogenous pain modulation: comparing exercise-induced hypoalgesia and offset analgesia in young, active adults

- Do pain-associated contexts increase pain sensitivity? An investigation using virtual reality

- Differences in Swedish and Australian medical student attitudes and beliefs about chronic pain, its management, and the way it is taught

- An experimental investigation of the relationships among race, prayer, and pain

- Educational case report

- Wireless peripheral nerve stimulation for complex regional pain syndrome type I of the upper extremity: a case illustration introducing a novel technology