Abstract

Background and aims:

Chronic widespread pain (CWP) is associated with poor quality of sleep, but the detailed underlying mechanisms are still not fully understood. In this study we investigated the influence of CWP on morning cortisol and fasting glucose concentrations as well as sleep disordered breathing.

Methods:

In this case-control study, subjects with CWP (n=31) and a control group without CWP (n=23) were randomly selected from a population-based cohort of women. Current pain intensity, sleep quality, excessive daytime sleepiness [Epworth sleepiness scale (ESS)], psychiatric comorbidity and occurrence of restless legs syndrome (RLS) were assessed. Overnight polygraphy was applied to quantify sleep apnoea, airflow limitation and attenuations of finger pulse wave amplitude (>50%) as a surrogate marker for increased skin sympathetic activity. Morning cortisol and fasting glucose concentrations were determined. Generalised linear models were used for multivariate analyses.

Results:

CWP was associated with higher cortisol (464±141 vs. 366±111 nmol/L, p=0.011) and fasting glucose (6.0±0.8 vs. 5.4±0.7 mmol/L, p=0.007) compared with controls. The significance remained after adjustment for age, body mass index, RLS and anxiety status (β=122±47 nmol/L and 0.89±0.28 mmol/L, p=0.009 and 0.001, respectively). The duration of flow limitation in sleep was longer (35±22 vs. 21±34 min, p=0.022), and pulse wave attenuation was more frequent (11±8 vs. 6±2 events/h, p=0.048) in CWP subjects compared with controls. RLS was associated with higher ESS independent of CWP (β=3.1±1.3, p=0.018).

Conclusions:

Elevated morning cortisol, impaired fasting glucose concentration and increased skin sympathetic activity during sleep suggested an activated adrenal medullary system in subjects with CWP, which was not influenced by comorbid RLS.

Implications:

CWP is associated with activated stress markers that may deteriorate sleep.

1 Introduction

Chronic widespread pain (CWP) is defined as persistent pain for at least 3 months and with the presence of pain in at least two contralateral body quadrants and the axial skeleton [1], [2]. At least 11% of the general population has been reported suffering from CWP [2]. Dysfunctional neural pain processing mechanisms like sensitisation, long-term potentiation of afferent pain signals and dysfunctional inhibition have been suggested as potential pathogenic mechanisms of CWP [3]. Disturbed sleep has been reported as a hallmark symptom of this chronic pain condition. However, the detailed underlying mechanisms are still not fully understood [4].

Restless legs syndrome (RLS)/Willis-Ekbom disease is a neurological condition that involves sensorimotor disturbance in the legs or the arms [5]. RLS symptom expression follows a circadian rhythm with increased symptom burden during late evening and night. Periodic limb movements (PLMs) occur in approximately 80% of all RLS patients and can considerably disrupt sleep architecture [5]. The pathogenesis of RLS is still not fully understood, and current hypotheses include dopaminergic dysfunction, reduced iron content in the central nervous system, local/systemic hypoxia, genetic associations and/or alteration in neurotransmitters like orexin [6].

RLS is a common comorbidity in patients with CWP, with a reported prevalence of 30–64% compared to approximately 10% in the general population [7], [8], [9], [10]. In a recent population-based study, we demonstrated that the likelihood of RLS is 5–6 times higher in middle aged women with multi-site pain compared to pain free controls independent of weight, age and psychiatric comorbidity [9]. Moreover, in women with CWP there was a strong detrimental influence of comorbid RLS on sleep quality, the degree of daytime sleepiness and body fatigue. The pathophysiological mechanisms to explain the association between CWP and RLS are still widely unknown.

The aim of the current case-control study was to investigate the impact of CWP on stress hormones, glucose metabolism and overnight skin sympathetic nervous activity. The influence of sleep disordered breathing and comorbid conditions (e.g. RLS, depression and anxiety) was also investigated.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design

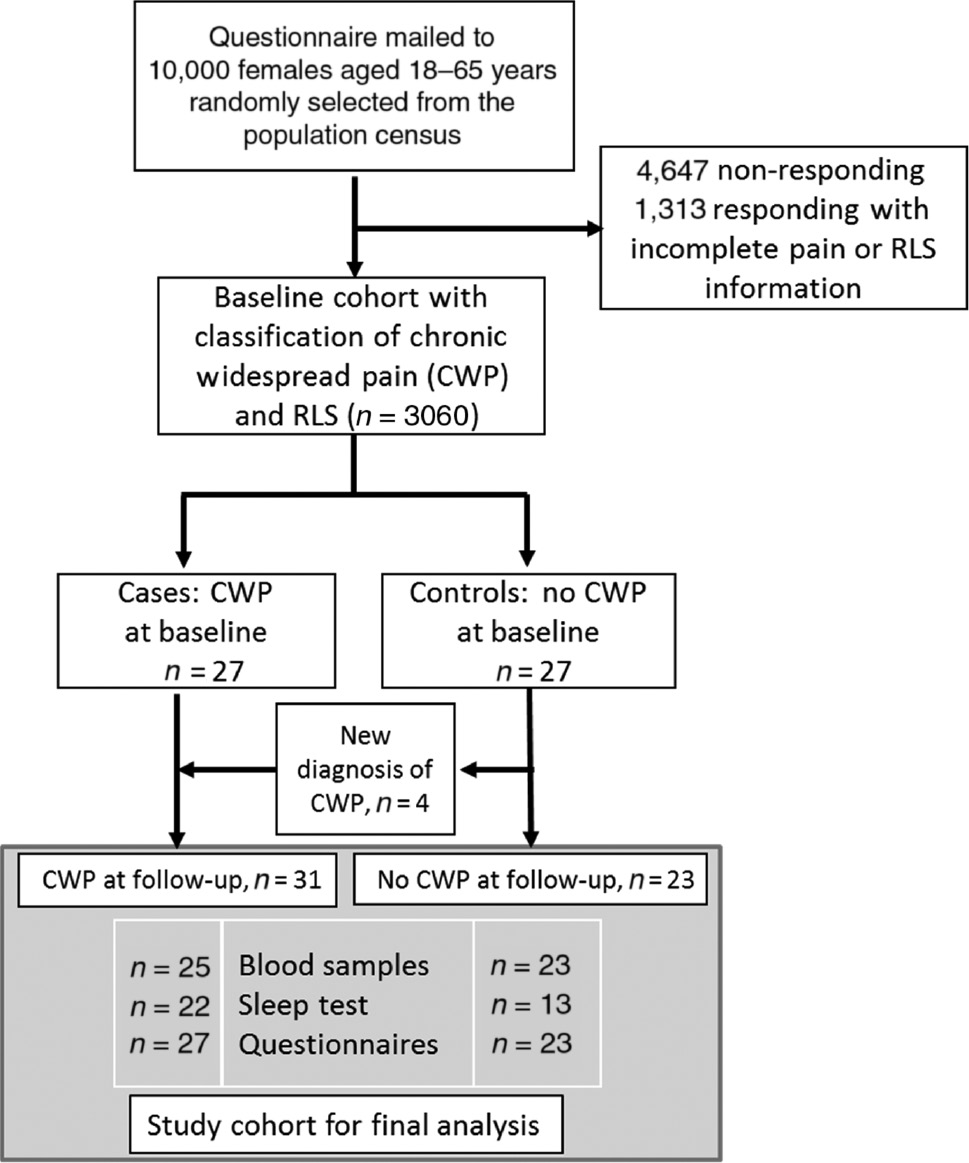

Study participants were recruited from a population-based questionnaire survey cohort of females aged 18–65 years in the Swedish county Dalarna [9]. In the current study, based on the CWP classification used in the original cohort, 27 women with pain presenting in all five body areas (neck, shoulder-arms, upper back, lower back and legs) were randomly selected from 3,060 participants. Twenty-seven controls without pain in the five areas at baseline were also identified. At follow-up, 4 out of the 27 controls reported multi-site pain and were therefore classified as CWP in the study. The final analysis group included 31 individuals in the CWP and 23 subjects without pain in the control groups (Fig. 1). All 54 subjects signed an informed consent after receiving oral and written information. The study was approved by the regional Ethical Review Board at Uppsala University (Dnr 2010-124).

The study flow chart illustrates the selection process of the study participants from the original population-based cohort to the final analysis cohort of the current study.

2.2 Study procedures

All subjects completed a series of questionnaires directly after blood sampling at 8:00 am (morning cortisol, fasting glucose and ferritin). Anthropometric data (age, height, body weight, current smoking) were collected, and psychiatric comorbidities were assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) questionnaire [11]. Subjects with CWP had a personal interview and a clinical examination performed by a pain specialist. In addition, 22 CWP women and 12 controls performed a sleep study at home (10:00 pm–7:00 am).

2.3 Pain assessment

For all participants, pain was assessed by means of a standardised pain drawing [12] and a visual analogue scale (VAS) [13], a line of 0–100 mm referring to current and previous pain (average, minimum and maximum). A neuropathic pain component was assessed by the Pain Detect questionnaire, an assessment tool that helps differentiate neuropathic pain from non-neuropathic pain [14], [15]. Subjects in the CWP group were physically examined, and the 18 tender points were assessed with algometry according to established criteria for the diagnosis of CWP [16].

2.4 RLS assessment

RLS was assessed using standard International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG) criteria for diagnosis of RLS [17]. Subjects who fulfilled all four criteria [(1) an urge to move the legs; (2) worsening at rest; (3) relieved by movement; and (4) with peak symptoms occurring at night or in the evening] were classified as RLS. Symptoms that could mimic RLS and are attributed to another mental disorder or medical condition (e.g. leg oedema, arthritis, leg cramps) or behavioural condition (e.g. positional discomfort, habitual foot tapping) were evaluated in CWP patients, and an RLS diagnosis was confirmed by an experienced physician. In addition, RLS severity and frequency was assessed using the validated IRLSSG rating scale [18]. A score of ≥20 was considered severe RLS.

2.5 Sleep assessment

Self-reported sleep quality was assessed by the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) questionnaire [19] and the degree of daytime sleepiness was evaluated by the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) [20]. Overnight sleep recording was performed using a cardiorespiratory polygraph (Embletta, Embla, Canada or T3, Nox Medical, Iceland). The recording montage includes nasal flow, respiratory effort, body position, limb movement by electromyography, oxygen saturation, heart rate and digital pulse wave amplitude (PWA) by oximetry. Apnoeas (≥90 reduction in airflow), hypopnoeas (≥50% but less than 90% reduction in airflow together with a 4% oxygen desaturation), 4% oxygen desaturations and airflow limitations (single breath flow contour analysis) were manually scored according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine guidelines [21] by an experienced scorer who was blinded to the subject’s group status. PLMs were classified based on electromyographic recordings. PWA attenuations (50% or more from the preceding baseline, moving-average window 20 s) were identified [22]. All event frequencies were indexed by analysis time (light-off to lights-on time).

2.6 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM-SPSS version 20.0 software (Illinois, USA). Student’s t-test for independent samples or the Kruskal Wallis test was used to evaluate significant group differences between cases and controls. Differences in frequency distributions were evaluated using the χ2 test. A generalised linear model (GLM) was used to evaluate the independent contribution of CWP on morning cortisol and fasting glucose controlling for age, body mass index (BMI), RLS and psychiatric comorbidities. Results are reported as mean±SD or β-values±SE. A p-value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Anthropometric data, pain and RLS status

Age, BMI and smoking status did not differ between women with and without CWP (Table 1). Women with CWP reported moderate to severe pain (defined as VAS 60–100) compared to controls (mean last 7-day pain VAS score 61±18 vs. 11±16, p<0.001). RLS was more prevalent in the CWP group compared with the non-CWP controls (77% vs. 26%, p<0.001). Severe RLS (IRLSSG rating scale ≥20) was found in 45% RLS cases with CWP, whereas the corresponding number was 13% in the control group (p<0.02).

Group differences in anthropometrics, pain reporting, RLS status, and psychiatric comorbidity.

| Variable | Chronic widespread pain (n=31) | Controls (n=23) | Between group difference (p-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 57±8 | 57±10 | n.s. |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.4±5.7 | 27.4±5.4 | n.s. |

| % current smokers | 11% | 17% | n.s. |

| Pain intensity scores – visual analogue scales (VAS) | |||

| VAS pain score – current | 57±20 | 6±12 | <0.001 |

| VAS pain score – preceding 7 days (mean) | 61±18 | 11±16 | <0.001 |

| Severe pain (VAS>70) preceding 7 days | 96% | 35% | <0.001 |

| RLS prevalence and intensity | |||

| RLS prevalence | 77% | 26% | <0.001 |

| IRLSS scale score | 15±10 | 5±9 | <0.001 |

| Severe RLS (IRRLS score ≥20) | 45% | 13% | 0.02 |

| Psychiatric comorbidity scores | |||

| Depression (HADS depression score ≥10) | 18.5% | 4.3% | 0.14 |

| Anxiety (HADS anxiety score ≥10) | 33% | 0% | 0.002 |

3.2 Blood sample analysis

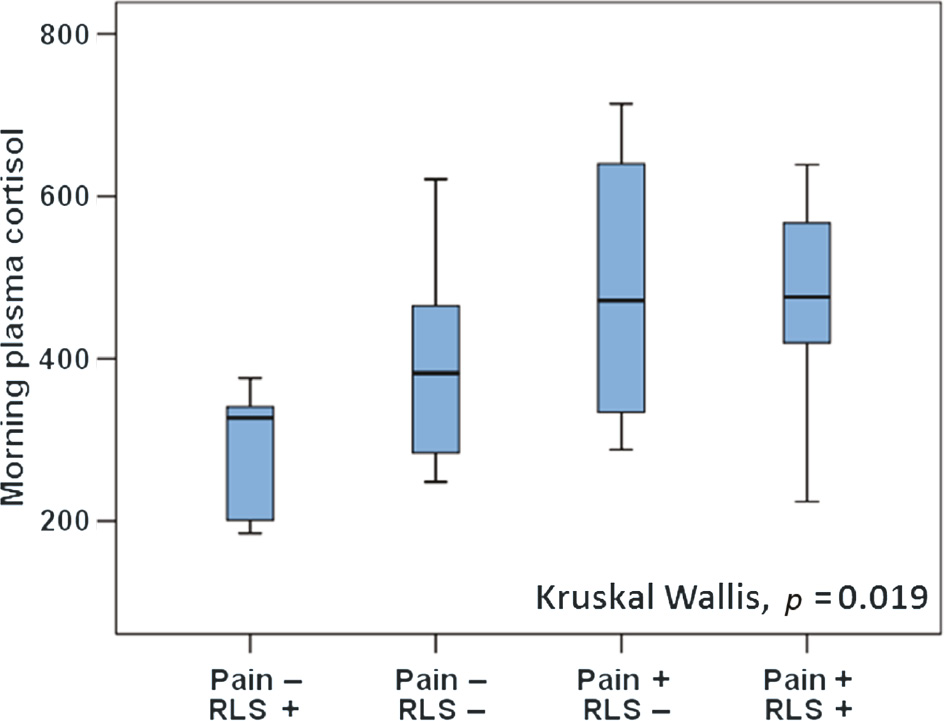

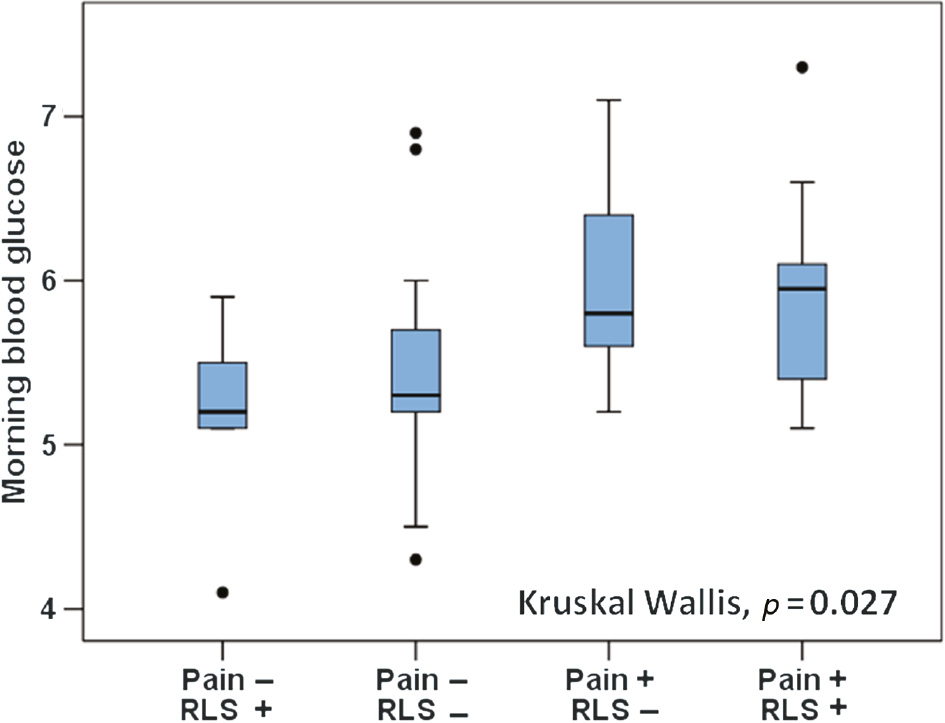

Morning cortisol levels (464±141 vs. 366±111 nmol/L, p=0.011) and fasting blood glucose (6.0±0.8 vs. 5.4±0.7 mmol/L, p=0.007) were elevated in subjects with CWP compared to the non-CWP group (Table 2). A ferritin threshold of <50 μg/L was fulfilled by one third of those with CWP and one quarter of the controls. There was no difference in mean ferritin levels between the CWP group and controls (89±68 vs. 88±45 μg/L, n.s.) or between women with and without RLS. The strong influence of CWP on morning cortisol levels and fasting blood glucose is illustrated in Figs. 2 and 3. There were no significant associations between RLS severity and cortisol or glucose levels. GLM analysis demonstrated that CWP diagnosis was associated with a 122±47 nmol/L increase in morning cortisol and a 0.89±0.28 mmol/L increase in fasting blood glucose after adjustment for age, BMI, RLS and anxiety status (p=0.009 and 0.001, respectively).

Blood sample analysis.

| Variable | Chronic wide-spread pain (n=25) | Controls (n=23) | Between group difference (p-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morning cortisol (nmol/L) | 464±141 | 366±111 | 0.011 |

| Fasting blood glucose (mmol/L) | 6.0±0.8 | 5.4±0.7 | 0.007 |

| Ferritin (μg/L) | 89±68 | 88±45 | n.s. |

| % Ferritin <50 μg/L | 36% | 26% | n.s. |

| % Ferritin <30 μg/L | 16% | 13% | n.s. |

Association between the chronic widespread pain/restless legs syndrome and morning cortisol (nmol/L).

Association between chronic widespread pain/restless legs syndrome and fasting blood glucose (mmol/L).

3.3 Psychiatric comorbidity

Symptoms related to depression and anxiety (HADS score) were associated with CWP and RLS diagnosis (Table 1). CWP was associated with symptoms of anxiety independent of age, BMI or RLS comorbidity (GLM analysis, β=3.0±1.3, p<0.02 for CWP). On the other hand, RLS was associated with the HADS depression score independent of a CWP diagnosis (GLM analysis, β=3.9±1.1, p<0.001 for RLS).

3.4 Subjective and objective measures of sleep

Self-reported sleep quality was poorer in those with CWP compared with controls (PSQI score 10.6±3.6 vs. 5.5±2.9, p<0.001, Table 3), and 92% of CWP subjects reported poor sleep quality (PSQI ≥5). There was an independent association between PSQI score and CWP status (GLM analysis for PSQI score, β=4.8±1.3, p<0.001 for CWP diagnosis). Moreover, subjective daytime sleepiness was elevated in CWP subjects when compared with controls (ESS score 9.1±4.3 vs. 6.0±3.2, p=0.011) and hypersomnia (ESS score ≥11) was seen in 41% of patients with CWP. However, GLM analysis demonstrated that RLS diagnosis was the strongest predictor of daytime sleepiness independent of the presence of CWP (GLM for ESS score, β=3.1±1.3, p<0.02 for RLS diagnosis).

Sleep study analysis.

| Self-reported sleep quality and degree of daytime sleepiness | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Chronic wide-spread pain (n=27) | Controls (n=23) | Between group difference (p-Value) |

| Epworth Sleepiness Scale Score | 9.1±4.3 | 6.0±3.2 | 0.011 |

| Hypersomnia (ESS score ≥11) | 41% | 9% | 0.012 |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index | 10.6±3.6 (n=25) | 5.5±2.9 (n=20) | <0.001 |

| Poor sleep quality (PSQI≥5) | 92% | 55% | 0.005 |

| Sleep polygraphic recording, CWP (n=22) and Controls (n=12) | |||

| Sleep analysis time (min) | 422±81 | 402±65 | n.s. |

| Apnoea hypopnoea index (n/h) | 6±6 | 5±5 | n.s. |

| 4% oxygen desaturation index (n/h) | 5±5 | 4±4 | n.s. |

| Mean oxygen saturation (%) | 95±2 | 94±2 | n.s. |

| Time below SaO2 <90% (%) | 4±10 | 2±4 | n.s. |

| Time in flow limitation (min) | 35±22 | 21±34 | 0.022 |

| Periodic limb movement index (n/h) | 5±11 | 9±12 | 0.09 |

| Mean pulse rate (bpm) | 66±9 | 61±8 | 0.08 |

| Finger pulse wave analysis in 17/3 subjects (CWP/controls) | |||

| PWA attenuation >50% index (events/h) | 11±8 | 6±2 | 0.048 |

Measures of sleep apnoea and nocturnal hypoxaemia did not differ between CWP subjects and controls (Table 3), although a diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnoea (apnoea-hypopnoea index ≥5 n/h) tended to be more prevalent among those with CWP (45% vs. 33%, n.s.). However, airflow limitation was more common in subjects with CWP during sleep compared with controls (35±22 vs. 21±34 min, p=0.022). Episodes with PWA attenuation during sleep (vasoconstriction of the digital vascular bed) were more frequent in those with CWP (PWA 50% index, 11±8 vs. 6±2 events/h, p=0.048). Additionally, mean overnight heart rate tended to be elevated in the CWP group (Table 3).

4 Discussion

From our study we can demonstrate several novel findings. Firstly CWP is associated with an upregulated stress response, both during wakefulness, demonstrated by elevated morning cortisol and impaired glycemic control, as well as during sleep, as shown by activation of sympathetic vascular control (PWA attenuation) and poor subjective sleep quality. Secondly, RLS in women with CWP is not independently associated with metabolic dysfunction, alterations in iron metabolism or overnight hypoxic load as previously described in RLS without CWP [23], [24]. These findings suggest a specific phenotype with RLS in this particular population, characterised by a high degree of neuropathic pain symptoms in CWP patients with RLS. Thirdly, depressive mood and cognitive dysfunction were linked to the RLS diagnosis rather than to CWP. It is also speculated that central nervous system processes linked to depression and sleepiness/fatigue also may be involved in the generation of RLS symptoms.

Acute pain induces a stress response that involves increased catecholamine secretion. Different types of stressors may induce specific biological and behavioural responses and the response pattern may vary significantly [25]. On the other hand, chronic pain conditions like CWP are considered to be associated with increased neurotransmitter activity of the central nervous system [26]. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympatho-adrenomedullary systems appear to be involved in both of the processes. In the current study, we found an almost 25% increase in morning cortisol levels irrespective of the confounders assessed. This finding is in line with previous studies which identified an activated HPA axis in fibromyalgia patients compared with matched controls [27], [28]. However, other studies also demonstrated a depressed HPA axis [29], [30], [31] or normal serum cortisol levels [32], [33] in patients with fibromyalgia. The differences in findings remain unexplained but may be related to the population-based setting in our study compared with clinic-based chronic fibromyalgia patients in previous studies. The duration of exposure to stimulation and comorbidity may also play a role in cortisol production and release in various pain conditions [34], [35].

A strong association between chronic pain and psychiatric comorbidity has been observed in several clinical studies, and a combination of HPA axis dysfunction and disturbed monoamine transmission was proposed as a key to understanding the association [36]. A recent study reported an increased odds ratio for depression in subjects with hypercortisolism (OR 1.9–2.4) when compared to eucortisolism [37]. Indeed, in our study we identified an increased prevalence of psychiatric diseases in subjects with CWP. Most interestingly, depression symptoms were linked to a comorbid RLS diagnosis, whereas anxiety symptoms were linked to CWP subjects with elevated cortisol levels.

A number of recent studies conducted in patients with fibromyalgia [7], [8], [9] and other chronic multi-site pain conditions [38] established a strong association between CWP and RLS. Most recently, we extended this association by showing a strong relationship between the number of pain areas and the prevalence of RLS [9]. Shortened and disturbed sleep was a hallmark in the association between CWP and RLS [39]. However, the possible mechanisms relating these two conditions have not been extensively studied. RLS is known to be related to iron deficiency [40], local or systemic hypoxia [23], [24], [41], hypercortisolism [42] and increased motor dysfunction during sleep [43]. Whilst we examined those factors as potential mechanisms for the dose-response relationship between pain localisation and RLS symptoms, none of those factors could be identified in our study. A partial explanation may be the limited sample size of the current investigation or CWP status rather than RLS status as inclusion criteria for entry in the study cohort. Another potential hypothesis for this particular RLS phenotype in CWP patients may be that the opioid system seems to play an important role in RLS. When RLS is associated with pain, endogenous opioids may excite dopaminergic activity that is either specific for reducing PLMs or has an effect sufficient enough to reduce PLMs but not to reduce RLS symptoms. This might partially explain the lower PLM index in women with CWP compared to the pain free group. Alternatively, we cannot exclude that RLS in CWP subjects has a different aetiology and pathogenic mechanism as evidenced by the finding that a neuropathic component had an increased prevalence in CWP subjects with RLS compared to those without [44].

Our study has several strengths and also limitations which need to be addressed. First, we describe a prospective study including individuals from a population-based sample which clearly increases the generalisation of our findings. Second, classification of CWP and RLS status is based on a detailed clinical interview, a physical examination, and questionnaires all performed by a CWP and RLS expert team. Our data also indicate a high reliability of the RLS/CWP status classification over time between baseline and follow-up assessments. Third, while missing data reduced the sample size, objective data were collected for metabolic parameters, causes of sleep fragmentation (apnoeas, hypopnoeas, flow limitation, and PLM), and overnight hypoxic exposures. In addition, in finger pulse wave analysis only 17/3 subjects (CWP/controls) were included in the final analysis. While control subjects did not perform all clinical examinations or interview with the CWP/RLS expert, we argue that the bias is toward a lower incidence of RLS diagnosis in the control group. The low IRLSSG rating score in the control group suggests that undiagnosed RLS in controls is less likely.

5 Conclusion

In this prospective study, we demonstrated that elevated morning cortisol levels, impaired fasting glucose control and markers of increased adrenergic sympathetic activity during sleep are associated with CWP in women. The stimulation of adrenergic sympathetic activity was not further influenced by RLS, although RLS was common in CWP and associated with increased mental and cognitive dysfunction. Future studies are warranted to investigate the influences of HPA abnormality and increased nocturnal sympathetic activity on sleep in patients with CWP.

-

Authors’ statements

-

Research funding: This study did not receive any grant funding from the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. There are no other financial interests to disclose.

-

Conflict of interest: All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

-

Informed consent: All 54 subjects signed an informed consent after receiving oral and written information.

-

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the regional Ethical Review Board at Uppsala University (Dnr 2010-124).

-

Authors’ contributions: RS: Study design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, writing of the manuscript. JU: Study design, data interpretation, reviewing the manuscript. DZ: Data analysis and interpretation, writing of the manuscript. JH: Study design, data interpretation, writing of the manuscript. LG: Study design, data analysis and interpretation, writing of the manuscript.

References

[1] Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, Bennett RM, Bombardier C, Goldenberg DL, Tuggwell P, Campell SL, Abeles M, Clark P, Fam AG, Farber SJ, Fiechtner JJ, Fanklin CM, Gatter RA, Hamaty D, Lessard J, Lichtbroun AS, Masi AT, McCain GA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum 1990;33:160–72.10.1002/art.1780330203Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Papageorgiou AC, Silman AJ, Macfarlane GJ. Chronic widespread pain in the population: a seven year follow up study. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61:1071–4.10.1136/ard.61.12.1071Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Costigan M, Scholz J, Woolf CJ. Neuropathic pain: a maladaptive response of the nervous system to damage. Ann Rev Neurosci 2009;32:1–32.10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135531Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Bellato E, Marini E, Castoldi F, Barbasetti N, Mattei L, Bonasia DE, Blonna D. Fibromyalgia syndrome: etiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Pain Res Treat 2012;2012:426130.10.1155/2012/426130Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Allen RP, Earley CJ. Restless legs syndrome: a review of clinical and pathophysiologic features. J Clin Neurophysiol 2001;18:128–47.10.1097/00004691-200103000-00004Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Allen RP. Restless Leg Syndrome/Willis-Ekbom Disease Pathophysiology. Sleep Med Clin 2015;10:207–14.10.1016/j.jsmc.2015.05.022Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Stehlik R, Arvidsson L, Ulfberg J. Restless legs syndrome is common among female patients with fibromyalgia. Eur Neurol 2009;61:107–11.10.1159/000180313Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Viola-Saltzman M, Watson NF, Bogart A, Goldberg J, Buchwald D. High prevalence of restless legs syndrome among patients with fibromyalgia: a controlled cross-sectional study. J Clin Sleep Med 2010;6:423–7.10.5664/jcsm.27929Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Stehlik R, Ulfberg J, Hedner J, Grote L. High prevalence of restless legs syndrome among women with multi-site pain: a population-based study in Dalarna, Sweden. Eur J Pain 2014;18:1402–9.10.1002/ejp.504Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Ulfberg J, Nystrom B, Carter N, Edling C. Restless Legs Syndrome among working-aged women. Eur Neurol 2001;46:17–9.10.1159/000050750Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 2002;52:69–77.10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00296-3Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] van den Hoven LH, Gorter KJ, Picavet HS. Measuring musculoskeletal pain by questionnaires: the manikin versus written questions. Eur J Pain 2010;14:335–8.10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.06.002Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Price DD, McGrath PA, Rafii A, Buckingham B. The validation of visual analogue scales as ratio scale measures for chronic and experimental pain. Pain 1983;17:45–56.10.1016/0304-3959(83)90126-4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U, Tolle TR. painDETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin 2006;22:1911–20.10.1185/030079906X132488Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Freynhagen R, Tolle TR, Gockel U, Baron R. The painDETECT project – far more than a screening tool on neuropathic pain. Curr Med Res Opin 2016;32:1033–57.10.1185/03007995.2016.1157460Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Gran JT. The epidemiology of chronic generalized musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2003;17:547–61.10.1016/S1521-6942(03)00042-1Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Salas RE, Gamaldo CE, Allen RP. Update in restless legs syndrome. Curr Opin Neurol 2010;23:401–6.10.1097/WCO.0b013e32833bcdd8Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Walters AS, LeBrocq C, Dhar A, Hening W, Rosen R, Allen RP, Trenkwalder C; International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Validation of the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group rating scale for restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med 2003;4:121–32.10.1016/S1389-9457(02)00258-7Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1989;28:193–213.10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 1991;14:540–5.10.1093/sleep/14.6.540Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Berry RB, Budhiraja R, Gottlieb DJ, Gozal D, Iber C, Kapur VK, Marcus CL, Mehra R, Parthasarathy S, Quan SF, Redline S, Strohl KP, Davidson Ward SL, Tangredi MM. Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: update of the 2007 AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events. Deliberations of the Sleep Apnea Definitions Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med 2012;8:597–619.10.5664/jcsm.2172Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Zou D, Grote L, Eder DN, Peker Y, Hedner J. Obstructive apneic events induce alpha-receptor mediated digital vasoconstriction. Sleep 2004;27:485–9.10.1093/sleep/27.3.485Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Earley CJ, Ponnuru P, Wang X, Patton SM, Conner JR, Beard JL, Taub DD, Allen RP. Altered iron metabolism in lymphocytes from subjects with restless legs syndrome. Sleep 2008;31:847–52.10.1093/sleep/31.6.847Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Salminen AV, Rimpila V, Polo O. Peripheral hypoxia in restless legs syndrome (Willis-Ekbom disease). Neurology 2014;82:1856–61.10.1212/WNL.0000000000000454Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Kvetnansky R, Sabban EL, Palkovits M. Catecholaminergic systems in stress: structural and molecular genetic approaches. Physiol Rev 2009;89:535–606.10.1152/physrev.00042.2006Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Williams DA, Clauw DJ. Understanding fibromyalgia: lessons from the broader pain research community. J Pain 2009;10:777–91.10.1016/j.jpain.2009.06.001Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Torpy DJ, Papanicolaou DA, Lotsikas AJ, Wilder RL, Chrousos GP, Pillemer SR. Responses of the sympathetic nervous system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis to interleukin-6: a pilot study in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:872–80.10.1002/1529-0131(200004)43:4<872::AID-ANR19>3.0.CO;2-TSuche in Google Scholar

[28] Adler GK, Geenen R. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and autonomic nervous system functioning in fibromyalgia. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2005;31:187–202, xi.10.1016/j.rdc.2004.10.002Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Crofford LJ. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal stress axis in fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome. Z Rheumatol 1998;57 Suppl 2:67–71.10.1007/s003930050239Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Heim C, Ehlert U, Hellhammer DH. The potential role of hypocortisolism in the pathophysiology of stress-related bodily disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2000;25:1–35.10.1016/S0306-4530(99)00035-9Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Becker S, Schweinhardt P. Dysfunctional neurotransmitter systems in fibromyalgia, their role in central stress circuitry and pharmacological actions on these systems. Pain Res Treat 2012;2012:741–6.10.1155/2012/741746Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Klerman EB, Goldenberg DL, Brown EN, Maliszewski AM, Adler GK. Circadian rhythms of women with fibromyalgia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:1034–9.10.1210/jc.86.3.1034Suche in Google Scholar

[33] van Denderen JC, Boersma JW, Zeinstra P, Hollander AP, van Neerbos BR. Physiological effects of exhaustive physical exercise in primary fibromyalgia syndrome (PFS): is PFS a disorder of neuroendocrine reactivity? Scand J Rheumatol 1992;21:35–7.10.3109/03009749209095060Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Maletic V, Raison CL. Neurobiology of depression, fibromyalgia and neuropathic pain. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2009;14:5291–338.10.2741/3598Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Generaal E, Vogelzangs N, Macfarlane GJ, Geenen R, Smit JH, Penninx BW, Dekker J. Reduced hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity in chronic multi-site musculoskeletal pain: partly masked by depressive and anxiety disorders. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014;15:227.10.1186/1471-2474-15-227Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Blackburn-Munro G. Hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction as a contributory factor to chronic pain and depression. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2004;8:116–24.10.1007/s11916-004-0025-9Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Maripuu M, Wikgren M, Karling P, Adolfsson R, Norrback KF. Relative hypo- and hypercortisolism are both associated with depression and lower quality of life in bipolar disorder: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2014;9:e98682.10.1371/journal.pone.0098682Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Hoogwout SJ, Paananen MV, Smith AJ, Beales DJ, O’Sullivan PB, Straker LM, Eastwood PR, McArdle N, Champion D. Musculoskeletal pain is associated with restless legs syndrome in young adults. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2015;16:294.10.1186/s12891-015-0765-1Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Stehlik R, Ulfberg J, Zou D, Hedner J, Grote L. Perceived sleep deficit is a strong predictor of RLS in multisite pain – A population based study in middle aged females. Scand J Pain 2017;17:1–7.10.1016/j.sjpain.2017.06.003Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Earley CJ, Connor J, Garcia-Borreguero D, Jenner P, Winkelman J, Zee PC, Allen R. Altered brain iron homeostasis and dopaminergic function in Restless Legs Syndrome (Willis-Ekbom Disease). Sleep Med 2014;15:1288–301.10.1016/j.sleep.2014.05.009Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Wahlin-Larsson B, Ulfberg J, Aulin KP, Kadi F. The expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in skeletal muscle of patients with sleep disorders. Muscle Nerve 2009;40:556–61.10.1002/mus.21357Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Schilling C, Schredl M, Strobl P, Deuschle M. Restless legs syndrome: evidence for nocturnal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system activation. Mov Disord 2010;25:1047–52.10.1002/mds.23026Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Montplaisir J, Boucher S, Poirier G, Lavigne G, Lapierre O, Lesperance P. Clinical, polysomnographic, and genetic characteristics of restless legs syndrome: a study of 133 patients diagnosed with new standard criteria. Mov Disord 1997;12:61–5.10.1002/mds.870120111Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Karroum EG, Golmard JL, Leu-Semenescu S, Arnulf I. Painful restless legs syndrome: a severe, burning form of the disease. Clin J Pain 2015;31:459–66.10.1097/AJP.0000000000000133Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Article note:

The manuscript is part of Romana Stehlik’s PhD thesis, “Restless Legs Syndrome among women with Chronic Widespread Pain”.

©2018 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain. Published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston. All rights reserved.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Topical review

- Reducing risk of spinal haematoma from spinal and epidural pain procedures

- Clinical pain research

- A multiple-dose double-blind randomized study to evaluate the safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and analgesic efficacy of the TRPV1 antagonist JNJ-39439335 (mavatrep)

- Reliability of three linguistically and culturally validated pain assessment tools for sedated ICU patients by ICU nurses in Finland

- Superior outcomes following cervical fusion vs. multimodal rehabilitation in a subgroup of randomized Whiplash-Associated-Disorders (WAD) patients indicating somatic pain origin-Comparison of outcome assessments made by four examiners from different disciplines

- Morning cortisol and fasting glucose are elevated in women with chronic widespread pain independent of comorbid restless legs syndrome

- Chronic pain experience and pain management in persons with spinal cord injury in Nepal

- The Standardised Mensendieck Test as a tool for evaluation of movement quality in patients with nonspecific chronic low back pain

- Exploring effect of pain education on chronic pain patients’ expectation of recovery and pain intensity

- Pain, psychological distress and motor pattern in women with provoked vestibulodynia (PVD) – symptom characteristics and therapy suggestions

- Relative and absolute test-retest reliabilities of pressure pain threshold in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- The influence of pre- and perioperative administration of gabapentin on pain 3–4 years after total knee arthroplasty

- Observational study

- CT guided neurolytic blockade of the coeliac plexus in patients with advanced and intractably painful pancreatic cancer

- Prescription of opioids to post-operative orthopaedic patients at time of discharge from hospital: a prospective observational study

- The psychological features of patellofemoral pain: a cross-sectional study

- Prevalence of self-reported musculoskeletal pain symptoms among school-age adolescents: age and sex differences

- The association between back muscle characteristics and pressure pain sensitivity in low back pain patients

- Postural control in subclinical neck pain: a comparative study on the effect of pain and measurement procedures

- Original experimental

- Exercise-induced hypoalgesia in women with varying levels of menstrual pain

- Exercise does not produce hypoalgesia when performed immediately after a painful stimulus

- Effectiveness of neck stabilisation and dynamic exercises on pain intensity, depression and anxiety among patients with non-specific neck pain: a randomised controlled trial

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Topical review

- Reducing risk of spinal haematoma from spinal and epidural pain procedures

- Clinical pain research

- A multiple-dose double-blind randomized study to evaluate the safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and analgesic efficacy of the TRPV1 antagonist JNJ-39439335 (mavatrep)

- Reliability of three linguistically and culturally validated pain assessment tools for sedated ICU patients by ICU nurses in Finland

- Superior outcomes following cervical fusion vs. multimodal rehabilitation in a subgroup of randomized Whiplash-Associated-Disorders (WAD) patients indicating somatic pain origin-Comparison of outcome assessments made by four examiners from different disciplines

- Morning cortisol and fasting glucose are elevated in women with chronic widespread pain independent of comorbid restless legs syndrome

- Chronic pain experience and pain management in persons with spinal cord injury in Nepal

- The Standardised Mensendieck Test as a tool for evaluation of movement quality in patients with nonspecific chronic low back pain

- Exploring effect of pain education on chronic pain patients’ expectation of recovery and pain intensity

- Pain, psychological distress and motor pattern in women with provoked vestibulodynia (PVD) – symptom characteristics and therapy suggestions

- Relative and absolute test-retest reliabilities of pressure pain threshold in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- The influence of pre- and perioperative administration of gabapentin on pain 3–4 years after total knee arthroplasty

- Observational study

- CT guided neurolytic blockade of the coeliac plexus in patients with advanced and intractably painful pancreatic cancer

- Prescription of opioids to post-operative orthopaedic patients at time of discharge from hospital: a prospective observational study

- The psychological features of patellofemoral pain: a cross-sectional study

- Prevalence of self-reported musculoskeletal pain symptoms among school-age adolescents: age and sex differences

- The association between back muscle characteristics and pressure pain sensitivity in low back pain patients

- Postural control in subclinical neck pain: a comparative study on the effect of pain and measurement procedures

- Original experimental

- Exercise-induced hypoalgesia in women with varying levels of menstrual pain

- Exercise does not produce hypoalgesia when performed immediately after a painful stimulus

- Effectiveness of neck stabilisation and dynamic exercises on pain intensity, depression and anxiety among patients with non-specific neck pain: a randomised controlled trial