Abstract

Background and aims:

Pain assessment in intensive care is challenging, especially when the patients are sedated. Sedated patients who cannot communicate verbally are at risk of suffering from pain that remains unnoticed without careful pain assessment. Some tools have been developed for use with sedated patients. The Behavioral Pain Scale (BPS), the Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT) and the Nonverbal Adult Pain Assessment Scale (NVPS) have shown promising psychometric qualities. We translated and culturally adapted these three tools for the Finnish intensive care environment. The objective of this feasibility study was to test the reliability of the three pain assessment tools translated into Finnish for use with sedated intensive care patients.

Methods:

Six sedated intensive care patients were videorecorded while they underwent two procedures: an endotracheal suctioning was the nociceptive procedure, and the non-nociceptive treatment was creaming of the feet. Eight experts assessed the patients’ pain by observing video recordings. They assessed the pain using four instruments: the BPS, the CPOT and the NVPS, and the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) served as a control instrument. Each expert assessed the patients’ pain at five measurement points: (1) right before the procedure, (2) during the endotracheal suctioning, (3) during rest (4) during the creaming of the feet, and (5) after 20 min of rest. Internal consistency and inter-rater reliability of the tools were evaluated. After 6 months, the video recordings were evaluated for testing the test-retest reliability.

Results:

Using the BPS, the CPOT, the NVPS and the NRS, 960 assessments were obtained. Internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient varied greatly with all the instruments. The lowest values were seen at those measurement points where the pain scores were 0. The highest scores were achieved after the endotracheal suctioning at rest: for the BPS, the score was 0.86; for the CPOT, 0.96; and for the NVPS, 0.90. The inter-rater reliability using the Shrout-Fleiss intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) tests showed the best results after the painful procedure and during the creaming. The scores were slightly lower for the BPS compared to the CPOT and the NVPS. The test-retest results using the Bland-Altman plots show that all instruments gave similar results.

Conclusions:

To our knowledge, this is the first time all three behavioral pain assessment tools have been evaluated in the same study in a language other than English or French. All three tools had good internal consistency, but it was better for the CPOT and the NVPS compared to the BPS. The inter-rater reliability was best for the NVPS. The test-retest reliability was strongest for the CPOT. The three tools proved to be reliable for further testing in clinical use.

Implications:

There is a need for feasible, valid and reliable pain assessment tools for pain assessment of sedated ICU patients in Finland. This was the first time the psychometric properties of these tools were tested in Finnish use. Based on the results, all three instruments could be tested further in clinical use for sedated ICU patients in Finland.

1 Introduction

Patient pain assessment and management are required for quality care in intensive care units (ICUs). Studies have shown that pain assessment and management in ICU patients are insufficient [1], [2]. For example, in Gélinas’ [3] study, up to 74% of ICU patients suffered moderate or severe pain, and up to 77% recalled experiencing pain [3]. In addition to illness, a patient’s pain can be caused by events such as endotracheal suctioning, chest tube removal, wound drain removal and arterial line insertion, which are some of the most painful procedures in intensive care [4]. Previous research has shown that systematic pain assessment decreases pain, the duration of mechanical ventilation and nosocomial infections [5], [6]. However, pain assessment in the ICU remains a challenge, especially when patients are sedated and not able to communicate.

Few potential pain assessment tools are available for sedated intensive care patients [7]. The Behavioral Pain Scale (BPS) [8], the Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT) [9] and the Nonverbal Adult Pain Assessment Scale (NVPS) [10] have shown promising psychometric qualities in systematic reviews [11], [12], [13], [14]. Fair to good agreement (0.74 and 0.75) has been found when evaluating the reliability of the BPS and the CPOT. Both instruments were able to discriminate between a painful and a non-painful procedure [15]. The reliability varied when the BPS and the NVPS were compared in situations with medical patients (the BPS=0.60, and the NVPS=0.65) and surgical patients (the BPS=0.77, and the NVPS=0.80). The validity of both tools was adequate [16]. In validation of the Swedish version of the CPOT also demonstrated good inter-rater reliability (on average 0.84) as well as adequate discriminant validity [17]. Validation of the Dutch version of the CPOT showed fair to moderate inter-rater reliability. In that study, the internal consistency was 0.56 (Cronbach α) during rest and when turning [18], and validity of the Swedish version of the CPOT showed that internal consistency was from 0.31 to 0.81 (Cronbach α) [17].

Deep sedation affected the pain assessment, so those scores are lower than without sedation [8]. Systematic pain assessment offers possibilities to ensure patients receive the right amount of sedatives and pain medication [5], [19]. With a systematic pain assessment, we also can diminish the amount of sedation; hence, the procedural pain can be cured adequately [7].

However, in 2017, no valid pain assessment tools were in systematic use in the Finnish ICUs. It is important to use well-established, properly translated and culturally adapted tools for pain care. There is a need for feasible, valid and reliable pain assessment tools for sedated ICU patients in Finland; therefore, we translated and culturally adapted the three above-mentioned tools [20].

The objective of this feasibility study was to test the reliability of the three Finnish translations of the pain assessment tools for sedated intensive care patients.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sample and setting

Six sedated intensive care patients were videorecorded while they underwent endotracheal suctioning and creaming of the feet in second-level (see Valentin et al. [21]) ICU care with 12 beds. The patients’ pain was assessed from the video recordings by eight experts, who were chosen based on their years of experience in intensive care, pain care and teaching, and their expertise in pain research.

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The patients were sedated, intubated and mechanically ventilated. The inclusion criteria for patients dictated that they must be older than 18 years of age, mechanically ventilated, needing sedation and pain medication, and in a hemodynamically reasonably stable state (a physician evaluated that the vital functions were stable enough). The following criteria was used to exclude patients from the study: quadriplegia, need for muscle relaxants, a head wound (brain damage) or other illness causing brain dysfunction, leg ulcer, or liver dysfunction or uraemia that can affect the level of consciousness.

2.3 Assessment tools

The three tools – the BPS, the CPOT and the NVPS, as well as the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) – were translated into Finnish. The BPS, the CPOT and the NVPS were chosen based on a systematic review which showed that these pain assessment tools were the most effective for assessing the pain of patients in the ICU [13]. The NRS was chosen because it has been the tool most often used by nurses to assess pain in the ICUs in Finland.

The BPS was developed by Payen et al. [8] and includes three assessment categories: facial expression, upper limb movement and compliance with ventilation. Each is scored from 1 to 4, and the total score ranges from 3 to 12 [8]. Patients are considered to experience significant pain if the BPS score is greater than 5 [7]. The CPOT was developed by Gélinas et al. [9] and includes four assessment categories: facial expressions, body movements, and muscle tension, and compliance with the ventilator for intubated patients or vocalization for nonintubated patients. Each behavior is rated on a scale from 0 to 2 with the total score ranging from 0 to 8. [9]. Patients are considered to be in significant pain if the BPS score is 3 or greater [7]. The BPS and the CPOT scales were developed specifically for pain assessment in ICU patients and are based on behavioral indicators. The American College of Critical Care Medicine recommends that the BPS and the CPOT be used for adults who are medical, postoperative or trauma patients in the ICU [7]. The NVPS was developed by Odhner et al. [10]. Wegman [22] revised the assessment tool so that behavioral and psychological indicators could be observed. The revised version was used in this study. The NVPS assesses five responses: face, activity (movement), guarding, physiological (vital signs; blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate) and respiration. Each is rated on a scale from 0 to 2 with a total score ranging from 0 to 10 [10]. There is no exact cut-off point for pain based on research using this instrument, but the scale is the same as the NRS. Patients are considered to be in significant pain if the NVPS score is 4 or greater, as is the same with the NRS tool [7]. The NRS was a commonly used pain assessment tool in ICUs around the world before new assessment tools were introduced [23]. It is a sensitive and specific tool used for detecting significant pain and is most often recommended for critically ill patients who can self-report [24]. The psychometric properties of these tools have not been tested in Finnish use.

The depth of sedation was assessed by the Richmond Agitation Scale (RASS), a 10-point score from unresponsive (−5) to combative (+4). The validity and reliability of the RASS have been assessed in several studies [25], [26].

The physiological variables collected from the patients were mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR). The analgesia used and the sedation administered were recorded.

2.4 Procedure for data collection

Each patient was at rest for 20 min before they were touched. Patients received their normal medications throughout the procedure. After the 20-min rest time, the patients were prepared for endotracheal suctioning. The nurse touched the patient, called him or her by name and advised what she was going to do. The nurse also prepared the equipment. Three patients each received an extra bolus of pain medication prior to the procedure. The nurses determined the dosage of the bolus based on their evaluation of each patient’s pain. It was not possible to control the amount additional pain medication administered during the study due to ethical reasons.

The nurse performed the suctioning. After the procedure, the patient rested for 20 min. The nurse prepared the patient for creaming of the feet in the same manner as for the suctioning and then performed the creaming. The session ended with the patient being untouched for another 20 min. Each video recording lasted, on average, just over 1 h. The design is seen in Fig. 1.

Study design and data collection. BPS, the Behavioral Pain Scale; CPOT, the Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool; NVPS, the Nonverbal Adult Pain Assessment Scale; NRS, the Numeric Rating Scale; RASS, the Richmond Agitation Scale.

Eight experts in pain care and ICU nursing care assessed the patients’ pain by viewing the video recordings. The pain was assessed using four instruments: the BPS, the CPOT and the NVPS, and the NRS, which was estimated by the nurse as a control instrument. Each expert assessed the patients’ pain at five measurement points (Fig. 1). After 6 months, the video recordings were evaluated with the same protocol by the same experts for testing the test-retest reliability.

2.5 Statistical methods

The pain scores are described as means and standard deviations at different time points. Mean arterial pressure and HR are described as absolute values. Internal consistency is described with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The inter-rater reliability was calculated using the Shrout-Fleiss ICC test, and the test-retest reliability was described using the Bland-Altman plots. The statistical software SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used.

2.6 Ethical aspects

The study protocol was approved by the Joint Commission on Ethics of the Satakunta Hospital District on 10 February 2010 and of Satakunta Central Hospital on 22 March 2010. Written informed consent could not be obtained from the patients due to their inability to communicate. Instead, a family member of each patient was informed orally and in writing. After providing the information, those family members were asked to provide consent on behalf of the patient. The nurses participating in the study also were informed orally and in writing, and they also signed informed consents regarding their participation. Only the research team had access to the data. The video recordings and patient data were kept separate and secure.

3 Results

Four participants were male and two were female. Their diagnoses were pneumonia (4), acute respiratory insufficiency (1) and epiglottitis (1). The patients’ mean age was 69 (from 40 to 83). Their sedation levels varied from −3 to −5. Propofol 120–180 mg/h was given for sedation, and oxycodone hydrochloride 1–3 mg/h was given for pain. The sedation medication and pain medication were administered, on average, 7 min 30 s (from 0 to 20 min) before the ETS. One patient did not receive additional medication. The propofol bolus averaged 40 mg (two patients were not administered a propofol bolus), and the oxycodone hydrochloride bolus averaged 2.3 mg (three patients did not receive an oxycodone hydrochloride bolus). Systematic pain and agitation guidelines were not in use. The nurses followed the doctor’s orders when administering the medications. Prior to the treatment, the nurses determined the dosage of each bolus. Nine hundred and sixty observations were evaluated. Mean pain scores and standard deviations are described in Table 1. The MAP and HR, which remained fairly stable throughout the study, also are illustrated in Table 1.

Pain scores at different time points (means and standard deviations).

| Mean pain scores (SD) n=6 | Time 1 |

Time 2 |

Time 3 |

Time 4 |

Time 5 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At rest | Test-retest | During ETS | Test-retest | After ETS, 20 min | Test-retest | During creaming | Test-retest | Post procedure | Test-retest | |

| BPS (scale 3–12) | 3.61 (1.03) | 3.52 (0.85) | 5.10 (1.08) | 4.54 (1.15) | 3.13 (0.11) | 3.17 (0.19) | 3.06 (0.1) | 3.10 (0.2) | 3.13 (0.25) | 3.27 (0.46) |

| CPOT (scale 0–8) | 0.90 (1.38) | 0.65 (1.13) | 2.54 (1.41) | 1.60 (1.15) | 0.15 (0.12) | 0.25 (0.30) | 0.04 (0.1) | 0.23 (0.27) | 0.23 (0.56) | 0.29 (0.48) |

| NVPS (scale 0–12) | 0.98 (1.49) | 0.73 (1.15) | 2.50 (1.73) | 1.75 (1.38) | 0.30 (0.18) | 0.25 (0.31) | 0.17 (0.13) | 0.19 (0.29) | 0.46 (0.62) | 0.40 (0.61) |

| NRS (scale 0–10) | 1.38 (0.81) | 1.02 (1.10) | 4.46 (2.17) | 3.13 (1.86) | 0.98 (0.33) | 0.63 (0.22) | 1.00 (0.51) | 0.56 (0.35) | 1.00 (0.34) | 0.58 (0.50) |

| MAP | 82 | 88 | 79 | 78 | 82 | |||||

| HR | 74 | 80 | 91 | 74 | 72 | |||||

-

BPS=the Behavioral Pain Scale; CPOT=the Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool; NVPS=the Nonverbal Adult Pain Assessment Scale; MAP=mean arterial pressure; HR=heart rate; ETS=endotracheal suctioning.

Internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient varied greatly with all instruments. The lowest values were recorded in those measurement points where the pain scores were 0. Highest scores were achieved after the endotracheal suctioning at rest: for the BPS, the score was then 0.86, the CPOT was 0.96, and the NVPS was 0.90. Table 2 shows the results of the internal consistency measures for the study.

Intraclass correlations and inter-rater reliability scores for BPS, CPOT and NVPS.

| Measure point n=6 | BPS | CPOT | NVPS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1: At rest | |||

| ICCa | 0.30 | 0.19 | 0.06 |

| Cronbach αa | 0.00 | 0.48 | 0.00 |

| Time 2: During ETS | |||

| ICC | 0.29 | 0.18 | 0.06 |

| Cronbach α | 0.00 | 0.57 | 0.26 |

| Time 3: After ETS, 20 min | |||

| ICC | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Cronbach α | 0.86 | 0.96 | 0.90 |

| Time 4: During creaming | |||

| ICC | 0.49 | 0.67 | 0.69 |

| Cronbach α | 0.69 | 0.89 | 0.85 |

| Time 5: Post procedure 20 min | |||

| ICC | 0.20 | 0.36 | 0.38 |

| Cronbach α | 0.47 | 0.58 | 0.67 |

-

aCronbach α=Cronbach alpha coefficient, ICC=Shrout-Fleiss intraclass correlation coefficient. BPS=the Behavioral Pain Scale, CPOT=the Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool, NVPS=the Nonverbal Adult Pain Assessment Scale, ETS=endotracheal suctioning.

The inter-rater reliability with the Shrout-Fleiss ICC tests showed the best results after the painful procedure and during the creaming. The scores were slightly lower for the BPS compared to the CPOT and the NVPS. At the baseline measurement point, the eight evaluators gave a score of 0 for pain in 80% of the evaluations with any of the instruments. Therefore, the reliability scores are close to 0. See Table 2 for detailed results of the inter-rater reliability scores.

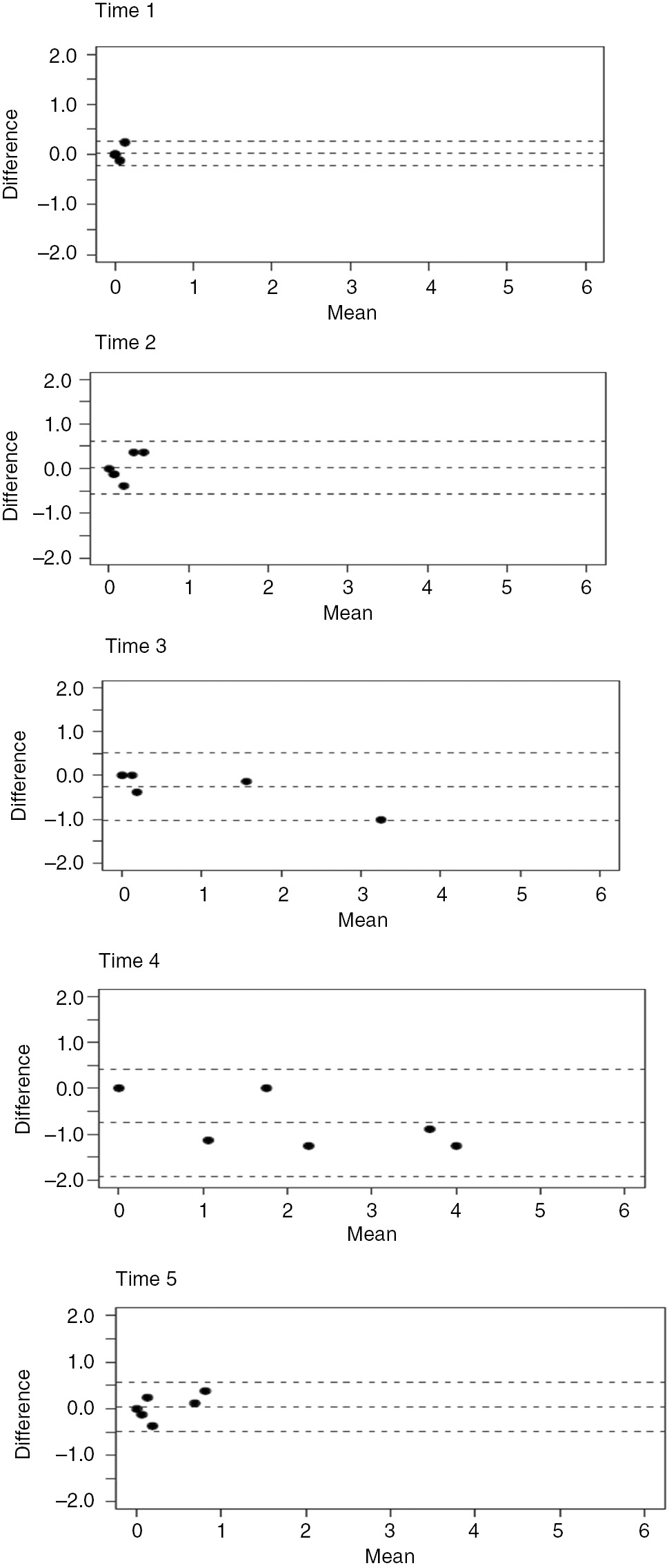

The test-retest results are illustrated in Figs. 2–4. The BPS Bland-Altman plots are illustrated in Fig. 2, the CPOT Bland-Altman plots are in Fig. 3, and the NVPS Bland-Altman plots are in Fig. 4. The Bland-Altman plots show that all instruments gave similar results. The retest values were always within one point of the first measurement and had a 95% confidence interval. The figures show less variability between the test and the retest measurements for the NVPS at time points 2 and 4 compared to those for the CPOT.

BPS Bland-Altman plots in time 1–5.

CPOT Bland-Altman plots in time 1–5.

NVPS Bland-Altman plots in time 1–5.

4 Discussion

The participants were fairly deeply sedated, and pain medication was administered continuously in an infusion. Some patients also were given boluses before the procedure. This seems to have affected the study results – during the painful procedure, the participants were not expressing pain, but when the effects of the bolus were diminishing, the patients showed expressions of pain even 20 min after the procedure. This could be seen in all results. The pain medication oxycodone hydrochloride was given in a varied scheme ranging from 0 to 20 min before the procedure. The effect of this medication was seen a few minutes after administration [27]. In some cases, the medication did not have an effect on the patient’s pain. Nurses did not necessarily evaluate the connection between the extra pain medication bolus and the procedure. This indicates a serious lack in systematic pain assessment and pain care. A more systematic approach to pain care would help intensive care nurses to recognize pain symptoms and signs. A systematic approach will secure correct doses of pain medication and sedation [5], [7], [19], [28]. In our study, the patients’ MAPs and HRs did not react greatly to pain.

Internal consistency varied with all instruments. However, they were slightly lower than in previous studies that used instruments in the original language, English or French [e.g. 9], [10], [29]. In our study, several patients had a pain score of 0 at several measurement points. This affected the results and lowered the ICCs. Similar results were previously reported when the Dutch version of the CPOT was tested [18]. Perhaps this is due to the small sample size and the type of patients participating in the study. In addition, we utilized eight evaluators instead of two, which is usually the case in similar studies [e.g. 30, 31, 32]. In real life, there are often more than two pain assessors for the same patient; hence, our study resembled actual practice. Also, the ICC was lower in the Dutch study, which used more than two evaluators [18]. Furthermore, deep sedation diminishes a patient’s pain expressions. Payen et al. [8] had low scores with the BPS with deeply sedated patients. In Wøien et al.’s [28] study, nurses estimated the pain of deeply sedated patients using the NRS, and the results were in line with Payen’s [8] study and with ours.

Even though the inter-rater reliability calculations gave low interclass correlations at measurement points with low pain scores, it does not mean that the reliability is low. This is due to how the calculations were performed. The differences between raters were measured in relation to the total variation, and if the differences in pain scores between the participants are smaller, then the variation between the raters is greater compared to the variation when differences in pain scores are bigger. Based on the inter-rater reliability scores, the CPOT differentiates mild pain less accurately than the NVPS.

All the instruments reacted to painful situations, an effect that has been seen in other studies [e.g. 29]. Payen et al. [8] made similar findings in deeply sedated patients while Topolevic-Vranic et al. [33] showed that the CPOT and the NVPS scores increased during a painful situation.

The test-retest reliability proved to be similar and good for all tools. All tool scores were within one point difference between the two measurement times with a 95% confidence interval. Similar results have been reported in two Chinese studies where the test-retest reliability of the Chinese version of the CPOT ranged from 0.81 to 0.93 [31], and test-retest reliability of the Chinese version of the BPS ranged from 0.50 to 0.84 [32].

Pain scores measured with the NRS were higher at all measurement points than with other tools. Similar results were reported previously [34].

Our results support the previous studies, and the Finnish translations of the BPS and the CPOT can be utilized as pain assessment tools in Finnish ICUs [29]. Accurate pain assessment supports ICU pain care and leads to an increase in care outcomes [6], [7].

This study had some limitations. Our sample size was small. However, the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the participants were strict, and the sample was homogeneous. In addition, we were able to use the same eight experts for both measurement time points, which increased the trustworthiness of the results. The deep sedation of the patients was challenging and made the assessment slightly difficult, especially when the participant was at rest. Some low pain scores may be due to the fairly deep sedation of the participants. The participants also were given intravenous pain medication. It would have been preferable to evaluate the pain of the participants in real-life situations. For example, in some cases it was difficult to evaluate the muscle tension since the evaluator was not able to touch the patient and assess the tension. However, our design made it possible to use the test-retest design. This was rarely used in previous studies.

5 Conclusions

To our knowledge, this was the first time all three behavioral pain assessment tools were evaluated in the same study in a language other than English or French. Although the study had its limitations, we concluded that the three tools had good internal consistency, but the results were better for the CPOT and the NVPS tools compared to the BPS. The inter-rater reliability was best for the NVPS, but it was good for the other two as well. The test-retest reliability was strongest for the CPOT, but the other instruments were not far behind. All three tools proved to be reliable for further testing in clinical use.

6 Implications

There is a need for reliable pain assessment tools for clinical use in Finnish ICUs. Our study design made it possible to test and retest three pain assessment tools for sedated patients in ICUs. All three instruments (the CPOT, the NVPS and the BPS) proved to be reliable with sedated ICU patients. Further clinical testing with larger samples is recommended.

-

Authors’ statements

-

Research funding: This work was supported by the Finnish Cultural Foundation, Satakunta Regional fund (29.5.2013), the Finnish Foundation of Nursing Education (15.1.2014) and the Finnish Association of Nursing Research (1.10.2013).

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from a family member of patients and nurses according to local regulations.

-

Ethical approval: The study protocol was approved by the Joint Commission on Ethics of the Satakunta Hospital District on 10 February 2010 and of Satakunta Central Hospital on 22 March 2010.

References

[1] Puntillo KA, Wild LR, Morris AB, Stanik-Hutt J, Thompson CL, White C. Practices and predictors of analgesic interventions for adults undergoing painful procedures. Am J Crit Care 2002;11:415–29.10.4037/ajcc2002.11.5.415Search in Google Scholar

[2] Payen JF, Chanques G, Mantz J, Hercule C, Auriant I, Leguillou JL, Binhas M, Genty C, Rolland C, Bosson JL. Current practices in sedation and analgesia for mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: a prospective multicenter patient-based study. Anesthesiology 2007;106:687–95.10.1097/01.anes.0000264747.09017.daSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Gélinas C. Management of pain in cardiac surgery ICU patients: Have we improved over time? Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2007;23:298–303.10.1016/j.iccn.2007.03.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Puntillo KA, Max A, Timsit JF, Vignoud L, Chanques G, Robleda G, Roche-Campo F, Mancebo J, Divatia JV, Soares M, Ionescu DC, Grintescu IM, Vasiliu IL, Maggiore SM, Rusinova K, Owczuk R, Egerod I, Papathanassoglou ED, Kyranou M, Joynt GM, et al. Determinants of procedural pain intensity in the intensive care unit. The Europain® study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;189:39–47.10.1164/rccm.201306-1174OCSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Chanques G, Jaber S, Barbotte E, Violet S, Sebbane M, Perrigault PF, Mann C, Lefrant JY, Eledjam JJ. Impact of systematic evaluation of pain and agitation in an intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2006;34:1691–9.10.1097/01.CCM.0000218416.62457.56Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Payen JF, Bosson JL, Chanques G, Mantz J, Labarere J. Pain assessment is associated with decresead duration of mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit. A post hoc analysisi of the DOLOREA study. Crit Care Med 2009;111:1308–16.10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181c0d4f0Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Barr J, Fraser G, Puntillo K, Wesley E, Gélinas C, Dasta J, Davidson J, Devlin J, Kress J, Joffe A, Coursin D, Herr D, Tung A, Robinson B, Fontaine D, Ramsay M, Riker R, Sessler C, Pun B, Skrobik Y, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2013;41:263–306.10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182783b72Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Payen JF, Bru O, Bosson JL, Lagrasta A, Novel E, Deschaux I, Lavagne P, Jacquot C. Assessing pain in critically ill sedated patients by using a behavioural pain scale. Crit Care Med 2001;29:2258–63.10.1097/00003246-200112000-00004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Gélinas C, Fillion L, Puntillo KA, Viens C, Fortier M. Validation of the critical-care pain observation tool in adult patients. Am J Crit Care 2006;15:420–27.10.4037/ajcc2006.15.4.420Search in Google Scholar

[10] Odhner M, Wegman D, Freeland N, Steinmetz A, Ingersoll GL. Assessing pain control in nonverbal critically ill adults. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2003;22:260–7.10.1097/00003465-200311000-00010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Cade CH. Clinical tools for the assessment of pain in sedated critically ill adults. Nurs Crit Care 2008;13:288–97.10.1111/j.1478-5153.2008.00294.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Li D, Puntillo K, Miaskowski C. A review of objective pain measures for use with critical care adult patients unable to self-report. J Pain 2008;9:2–10.10.1016/j.jpain.2007.08.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Pudas-Tähkä SM, Axelin A, Aantaa R, Lund V, Salanterä S. Pain assessment tools for unconscious or sedated intensive care patients: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs 2009;65:946–56.10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04947.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Stites M. Observational pain scales in critically ill adults. Crit Care Nurse 2013;33:68–78.10.4037/ccn2013804Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Rijkenberg S, Stilma W, Endeman H, Bosman RJ, Oudemans-van Straaten HM. Pain measurement in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: Behavioral Pain Scale versus Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool. J Crit Care 2015; 30:167–72.10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.09.007Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Juarez P, Bach A, Baker M, Duey D, Durkin S, Gulczynski B, Nellett M, O’Mara S, Schleder B, Lefaiver CA. Comparison of two pain scales for the assessment of pain in the ventilated adult patient. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2010;29:307–15.10.1097/DCC.0b013e3181f0c48fSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Nürnberg Damström D, Saboonchi F, Sackey PV, Björling G. A preliminary validation of the Swedish version of the Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool in adults. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2011;55:379–86.10.1111/j.1399-6576.2010.02376.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Stilma W, Rijkenberg S, Feijen HM, Maaskant JM, Endeman H. Validation of the Dutch version of the critical-care pain observation tool. Nurs Crit Care 2015; doi:10.111/nicc.1225.10.111/nicc.1225Search in Google Scholar

[19] Gélinas C, Arbour C, Michaud C, Vaillant F, Desjardins S. Implementation of the critical-care pain observation tool on pain assessment/management nursing practices in an intensive care unit with nonverbal critically ill adults: a before and after study. Int J Nurs Stud 2011;48:1495–504.10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.03.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Pudas-Tähkä SM, Axelin A, Aantaa R, Lund V, Salanterä S. Translation and cultural adaptation of an objective pain assessment tool for Finnish ICU patients. Scand J Caring Sci 2014;28:885–94.10.1111/scs.12103Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Valentin A, Ferdinande P, ESCIM Working Group on Quality Improvement. Recommendations on basic requirements for intensive care units: structural and organizational aspects. Intensive Care Med 2011;37:1575–87.10.1007/s00134-011-2300-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Wegman DA. Tool for pain assessment. Crit Care Nurse 2005;25:14–5.10.4037/ccn2005.25.1.14-aSearch in Google Scholar

[23] Skrobik Y, Chanques G. The pain, agitation, and delirium practice guidelines for adult critically ill patients: a post-publication perspective. Ann Intensive Care 2013;3:9.10.1186/2110-5820-3-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Chanques G, Viel E, Constantin JM, Jung B, de Lattre S, Carr J, Cissé M, Lefrant JY, Jaber S. The measurement of pain in intensive care unit: comparison of 5 self-report intensity scales. Pain 2010;151:711–21.10.1016/j.pain.2010.08.039Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, Brophy GM, O’Neal PV, Keane KA, Tesoro EP, Elswick RK. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:1338–44.10.1164/rccm.2107138Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Ely EW, Truman B, Shintani A, Thomason JW, Wheeler AP, Gordon S, Francis J, Speroff T, Gautam S, Margolin R, Sessler CN, Dittus RS, Bernard GR. Monitoring sedation status over time in ICU patients: reliability and validity of the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS). J Am Med Assoc 2003;289:2983–91.10.1001/jama.289.22.2983Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Pharmaca Fennica. OXANEST injektioneste, liuos 10 mg/ml https://www.pharmacafennica.fi/spc/2192511#annostusjaantotapa (28.9.2017), 2017Search in Google Scholar

[28] Wøien H, Stubhaug A, Bjørk IT. Improving the systematic approach to pain and sedation management in the ICU by using assessment tools. J Clin Nurs 2012;23:1552–61.10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04309.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Chanques G, Pohlman A, Kress JP, Molinari N, de Jong A, Jaber S, Hall JB. Psychometric comparison of three behavioural scales for the assessment of pain in critically ill patients unable to self-report. Crit Care 2014;18:R160.10.1186/cc14000Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Liu Y, Li L, Herr K. Evaluation of two observational pain assessment tools in Chinese critically ill patients. Pain Med 2015;16:1622–8.10.1111/pme.12742Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Li Q, Wan X, Gu C, Yu Y, Huang W, Li S, Zhang Y. Pain assessment using the critical-care pain observation tool in Chinese critically ill ventilated adults. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;48:975–82.10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.01.014Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Chen YY, Lai YH, Shun SC, Chi NH, Tsai PS, Liao YM. The Chinese Behavior Pain Scale for critically ill patients: translation and psychometric testing. Int J Nurs Stud 2011;48:438–48.10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.07.016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Topolovec-Vranic J, Gelinas C, Li Y, Pollmann-Mudryj MA, Innis J, McFarlan A, Canzian S. Validation and evaluation of two observational pain assessment tools in a trauma and neurosurgical intensive care unit. Pain Res Manag 2013;18:e107–14.10.1155/2013/263104Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Buttes P, Keal G, Cronin SN, Stocks L, Stout C. Validation of the critical-care pain observation tool in adult critically ill patients. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2014;33:78–81.10.1097/DCC.0000000000000021Search in Google Scholar PubMed

©2018 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain. Published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston. All rights reserved.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Topical review

- Reducing risk of spinal haematoma from spinal and epidural pain procedures

- Clinical pain research

- A multiple-dose double-blind randomized study to evaluate the safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and analgesic efficacy of the TRPV1 antagonist JNJ-39439335 (mavatrep)

- Reliability of three linguistically and culturally validated pain assessment tools for sedated ICU patients by ICU nurses in Finland

- Superior outcomes following cervical fusion vs. multimodal rehabilitation in a subgroup of randomized Whiplash-Associated-Disorders (WAD) patients indicating somatic pain origin-Comparison of outcome assessments made by four examiners from different disciplines

- Morning cortisol and fasting glucose are elevated in women with chronic widespread pain independent of comorbid restless legs syndrome

- Chronic pain experience and pain management in persons with spinal cord injury in Nepal

- The Standardised Mensendieck Test as a tool for evaluation of movement quality in patients with nonspecific chronic low back pain

- Exploring effect of pain education on chronic pain patients’ expectation of recovery and pain intensity

- Pain, psychological distress and motor pattern in women with provoked vestibulodynia (PVD) – symptom characteristics and therapy suggestions

- Relative and absolute test-retest reliabilities of pressure pain threshold in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- The influence of pre- and perioperative administration of gabapentin on pain 3–4 years after total knee arthroplasty

- Observational study

- CT guided neurolytic blockade of the coeliac plexus in patients with advanced and intractably painful pancreatic cancer

- Prescription of opioids to post-operative orthopaedic patients at time of discharge from hospital: a prospective observational study

- The psychological features of patellofemoral pain: a cross-sectional study

- Prevalence of self-reported musculoskeletal pain symptoms among school-age adolescents: age and sex differences

- The association between back muscle characteristics and pressure pain sensitivity in low back pain patients

- Postural control in subclinical neck pain: a comparative study on the effect of pain and measurement procedures

- Original experimental

- Exercise-induced hypoalgesia in women with varying levels of menstrual pain

- Exercise does not produce hypoalgesia when performed immediately after a painful stimulus

- Effectiveness of neck stabilisation and dynamic exercises on pain intensity, depression and anxiety among patients with non-specific neck pain: a randomised controlled trial

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Topical review

- Reducing risk of spinal haematoma from spinal and epidural pain procedures

- Clinical pain research

- A multiple-dose double-blind randomized study to evaluate the safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and analgesic efficacy of the TRPV1 antagonist JNJ-39439335 (mavatrep)

- Reliability of three linguistically and culturally validated pain assessment tools for sedated ICU patients by ICU nurses in Finland

- Superior outcomes following cervical fusion vs. multimodal rehabilitation in a subgroup of randomized Whiplash-Associated-Disorders (WAD) patients indicating somatic pain origin-Comparison of outcome assessments made by four examiners from different disciplines

- Morning cortisol and fasting glucose are elevated in women with chronic widespread pain independent of comorbid restless legs syndrome

- Chronic pain experience and pain management in persons with spinal cord injury in Nepal

- The Standardised Mensendieck Test as a tool for evaluation of movement quality in patients with nonspecific chronic low back pain

- Exploring effect of pain education on chronic pain patients’ expectation of recovery and pain intensity

- Pain, psychological distress and motor pattern in women with provoked vestibulodynia (PVD) – symptom characteristics and therapy suggestions

- Relative and absolute test-retest reliabilities of pressure pain threshold in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- The influence of pre- and perioperative administration of gabapentin on pain 3–4 years after total knee arthroplasty

- Observational study

- CT guided neurolytic blockade of the coeliac plexus in patients with advanced and intractably painful pancreatic cancer

- Prescription of opioids to post-operative orthopaedic patients at time of discharge from hospital: a prospective observational study

- The psychological features of patellofemoral pain: a cross-sectional study

- Prevalence of self-reported musculoskeletal pain symptoms among school-age adolescents: age and sex differences

- The association between back muscle characteristics and pressure pain sensitivity in low back pain patients

- Postural control in subclinical neck pain: a comparative study on the effect of pain and measurement procedures

- Original experimental

- Exercise-induced hypoalgesia in women with varying levels of menstrual pain

- Exercise does not produce hypoalgesia when performed immediately after a painful stimulus

- Effectiveness of neck stabilisation and dynamic exercises on pain intensity, depression and anxiety among patients with non-specific neck pain: a randomised controlled trial