Abstract

This paper presents a research review on fabrication processes and mechanical characterization of aluminum matrix composites (AMCs), which have found application in structural, electrical, thermal, tribological, and environmental fields. A comprehensive literature review is carried out on various types of fabrication processes, the effects of individual reinforcement and multiple reinforcements, its percentage, size, temperature, processing time, wettability, and heat treatment on the mechanical characterization of AMCs including different product applications. Various models and techniques proposed to express the mechanical characteristics of AMCs are stated here. The concluding remarks addresses the future work needed on AMCs.

- Abbreviations

- Al

Aluminum

- MMCs

Metal matrix composites

- AMCs

Aluminum matrix composites

- SiC

Silicon carbide

- Al2O3

Aluminum oxide

- SC

Stir casting

- PM

Powder metallurgy

- SQ

Squeeze casting

- CC

Compo casting

- CG

Centrifugal casting

- EMS

Electromagnetic stir casting

- PI

Pressureless infiltration

- ARB

Accumulative roll bonding

- IC

Investment casting

- ISPM

In situ powder metallurgy

- HT

Heat treatment

- p

Particles

1 Introduction

Composite materials are receiving remarkable attention in structural, electrical, thermal, tribological, and environmental fields nowadays, as they have high specific strength, corrosion resistance, fatigue strength, good tribological properties, etc. [1], [2]. Composites are used for making components in the aircraft industry, in space vehicles, the electronic industry, in medical equipment, and in home appliances [3], [4].

Composite material is a combination of two or more constituents having different physical or chemical properties that remain separate on a macroscopic level [5], [6]. The matrix as a continuous phase, controls the strength at different temperatures, while reinforcement provides better level of strength and stiffness to the composite [7].

A composite can be classified on the basis of the matrix material as follows:

Metal matrix composites (MMCs),

Ceramic matrix composites (CMCs),

Polymer matrix composites (PMCs).

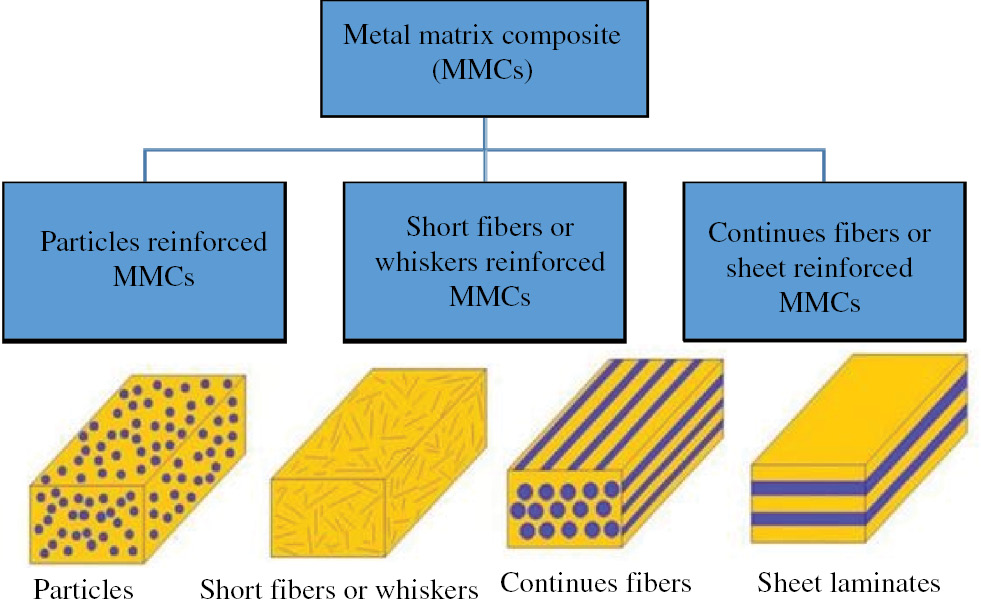

In MMCs, aluminum (Al), magnesium (Mg), titanium (Ti), and copper (Cu) are frequently used as matrix elements [8]. MMCs are classified on the basis of reinforcing elements [9] as shown in Figure 1, such as:

Types of metal matrix composite.

Particle-reinforced MMCs,

Short fiber or whisker-reinforced MMCs,

Continuous fiber or sheet-reinforced MMCs.

In this paper, an effort is made to review fabrication processes as well as the mechanical characterization of particulate-reinforced aluminum matrix composites (AMCs) because it has been found to be an application for fabrication of various components [5], [10], [11].

2 Aluminum matrix composite

Al has low density and good corrosion resistance; hence, it is useful in MMCs [12]. With the addition of appropriate reinforcing particles like oxides, carbides, or nitrides in matrices, the mechanical property of AMCs can be enhanced [13]. Moreover, the addition of multiple reinforcement in the matrix tends to further improve the mechanical properties [14]. Regarding the size of particle, research is remarkably accelerated nowadays from macro- to nano-size particles [15]. Nano particles have higher specific surface areas and high surface energy; hence, mechanical performance improves compared to micro-size particle-reinforced AMCs [16]. Macro to nano particle-reinforced AMCs are fabricated using various processes as stated below.

3 Fabrication processes

The commonly used fabrication process for AMCs grouped as the solid state method and the liquid metallurgy route [9], [17] is briefly discussed in the following sections.

3.1 Solid state method

The solid state method includes: powder metallurgy (PM) process, diffusion bonding process, and physical vapor deposition for AMCs fabrication.

3.1.1 PM process

This process consists of four basic steps: (i) blending of gas-atomized matrix and reinforcement, (ii) compacting the homogeneous blend, (iii) degassing the preform to remove volatile contaminants, and (iv) consolidation by vacuum hot pressing. Finally, hot pressed billets can be extruded as shown in Figure 2. In this method, the volume content of reinforcement can be easily controlled [9], and grain refinement during mixing improves the hardness and strength of the composites, while PM is not an ideal technology for mass production.

Schematic view of PM process for AMC fabrication.

3.1.2 Diffusion bonding process

Foil-fiber-foil bonding processes, matrix alloy of foil or powder cloth, and fiber arrays are stacked together as illustrated in Figure 3. Stacked layers are hot pressed through hot isostatic pressing; hence, diffusion bonding takes place between the materials. The main advantage of this method is fiber orientation, and fiber percentage is closely controlled. On the other hand, it requires higher processing temperature and pressure. Expensive and limited shapes can be fabricated through this process [9], [17].

Schematic view of foil-fiber-foil diffusion bonding process.

3.1.3 Physical vapor deposition process

In this process, the continuous passage of the fiber through a region of high partial pressure of the metal is deposited. MMCs are fabricated by assembling the matrix-coated fibers into a bundle, subsequently consolidated in a hot press. This technique can produce MMCs with uniform distribution up to 70%–80% vol. fraction. This process facilitates a wide range of nanolaminate structures and controls the thickness of the individual layer with the interface [17].

3.2 Liquid metallurgy route

The most common liquid metallurgy processes are stir casting (SC), squeeze casting (SQ), spray co-deposition, and in situ processes.

3.2.1 Stir casting process

In SC process, reinforcement is added into the liquid matrix melt, and the MMCs then solidify. After melting of the matrix, it is stirred vigorously for a while to form a vortex in the melt; thereafter, reinforcing particles are added at the side of the vortex as shown in Figure 4. It is simple, economical, and applicable for mass production. Poor interfacial bonding, wettability [18], [19], [20], and non-uniform reinforcement distribution are observed to some extent.

Schematic view of SC process.

3.2.2 SQ process

Molten metal is forced under pressure into particulate pre-form to produce MMCs. The matrix material with the required additives is melted in a crucible, and the reinforcing element is preheated separately. Finally, molten metal is poured on to the reinforcement, and simultaneously, pressure is applied through a ram as illustrated in Figure 5. The main benefits of this process are minimum interfacial reaction of matrix with reinforcement, low shrinkage, and ability to fabricate complex shapes [9].

Schematic view of SQ technique.

3.2.3 Spray co-deposition process

Melted metal and liquid stream are atomized; a fine solid powder is formed due to the rapid solidification of the metal. The stated technique is modified by co-depositing the reinforcing element with the matrix as shown in Figure 6. Higher production rate and lower solidification time promotes a minimum reaction of matrix with reinforcement [9]. Particle distribution in the composite depends upon the size and percentage of the reinforcement.

Schematic view of spray co-deposition technique.

3.2.4 In situ process

There are two major types of in situ process: (i) reactive and (ii) non-reactive.

The reactive type process consists of two elements, which react exothermically for the production of the reinforcing phase. For example, TiB2 particles are formed as:

In the non-reactive type process, monotectic and eutectic phases of alloys are used to form the reinforcement and matrix. Unidirectional solidification is controlled in the in situ process to produce MMCs, and a schematic view of the in situ process is shown in Figure 7. A crucible with a eutectic alloy moves downward from the top, and alternatively, the induction coil moves vice versa, when heating the alloy. This movement results in further melting followed by re-solidification of the composite under controlled cooling conditions. This process eliminates the wettability problem, so a clean and strong interface is formed between the matrix and the reinforcement [9].

Schematic view of in situ process.

Moreover, there is continuous development in the fabrication processes for the enrichment of the mechanical properties of AMCs.

In the gravity casting method, the cooling rate is low; and hence, a tendency of non-homogeneous reinforcing particle distribution in the matrix and porosity formation is observed. The porosity level is decreased by applying pressure during the SQ process. The compocasting method has a low agglomeration of Al2O3p, better wettability, and more uniform distribution, which proves that it has better mechanical properties than SC [21].

Rajan et al. [22] compared SC, compocasting, and SQ for 5% fly ash (FAp)-reinforced AMCs. They observed that the SQ method had better FApdistribution than compocasting and SC. The major elements of FA are SiO2, aluminum oxide (Al2O3) and Fe2O3, which react with Al and Mg alloys:

The MgAl2O4 spinels presents at interface or are distributed in the matrix, which leads to an increase in the undesirable particle-matrix debonding. In the case of the compocasting technique, the Si content in the matrix can minimize the kinetics of the reaction shown in equation (2). On the other hand, eutectic Si and Fe intermetallic are formed with a higher amount in the SC process as shown in equations (4) and (5). Hence, the compocasting process gives a better AMC quality than SC.

Conventional fabrication processes produce agglomerated arrangement of matrix and reinforcement, which lead to lower mechanical properties of AMCs. Barekar et al. [23] focused on distributive and dispersive mixing of composition under shearing action during the fabrication of AMCs. They have proposed the melt conditioned high-pressure die casting (MC-HPDC) method for AMC fabrication. The MC-HPDC process has improved particle distribution in the matrix with a strong interfacial bonding. Hence, better ultimate tensile strength (UTS) and tensile elongation have been reported compared with the conventional process.

In mechanical SC, the stirrer is used to rotate molten metal in a crucible. But in mechanical stirring, the stirrer erodes frequently during the stirring process, and eroded particles are mixed with the composite. Moreover, in some cases, the reinforcing particles are broken during stirring. Hence, the quality of the composite deteriorates [24]. These problems can be overcomed using the novel technique of electromagnetic stir casting (EMS). When AC power is supplied to the motor’s stator, an electromagnetic field is created [25]. Hence, the fluid (molten metal) inside the stator will rotate to achieve effective and reliable stirring [26] as shown in Figure 8. A vortex can draw reinforcement into the melt, so continuous dispersement is achieved [24], [27], [28].

Schematic view of EMS process setup.

Dwivedi et al. [29] investigated the mechanical performance of SiCp (5%, 10%, 15%) reinforced in A356, fabricated using the EMS process. They have reported enhancement in tensile strength, hardness, and toughness by the addition of SiCp in A356.

Clustering of particles is observed in AMCs, when fabricated through the conventional stirring process. Also, porosity is observed due to gas entrapment, hydrogen formation, and shrinkage during solidification. Consequently, it degrades the mechanical properties of AMCs [30], [31], [32]. This can be overcomed by applying ultrasonic treatment (UST) in AMC fabrication. Figure 9 shows the ultrasonic vibration-assisted technique for AMC fabrication. UST creates strong non-linear transient cavitation and acoustic streaming in the molten Al [33]. UST is capable of producing sufficient energy for breaking particle clusters and removes unwanted surface gases, thus, resulting in the improvement of wetting characteristic with molten Al. Moreover, oscillating and collapsing cavities generate better dispersion; hence, a homogeneous AMC microstructure is achieved [34], [35]. The porosity observed is 6.54% for AMC samples without ultrasonic treatment, and by the application of 12 min of ultrasonic vibration, it is reduced considerably to 0.86% [36].

Schematic view of the ultrasonic vibration-assisted technique for AMCs fabrication.

Kai et al. [37] carried out an ultrasonic process by breaking the agglomerated clusters of nano ZrB2 particle, which resulted in improved tensile property of AMCs. Mohanty et al. [38] have fabricated Al2O3p-reinforced nanocomposites using ultrasonic cavitation and reported enhancement of mechanical property with uniform distribution of nanoparticles in the matrix. Harichandran and Selvakumar [39] successfully fabricated micro and nano B4Cp-reinforced AMCs using an ultrasonic cavitation-assisted fabrication process. First, mechanical stirring was employed for 10 min as a primary distribution of particles in the molten Al. Subsequently ultrasonic cavitation was achieved by dipping a probe into the molten Al to break the particle clusters. The nanocomposite has higher ductility, strength, impact energy, and hardness than the micro B4Cp-reinforced AMCs.

Liu et al. [40] combined an in situ technique with ultrasonic vibration treatment for Ti and Gr-reinforced AMCs. The following exothermic reactions have been observed:

In the meantime, for the in situ technique, an ultrasonic generator of 1.5 kW and 20 kHz frequency was used to create vibration into the molten aluminum. Hence, because of ultrasonic degassing, the porosity level was decreased remarkably. Moreover, the particle clusters were broken, and oxide inclusions were eliminated effectively.

An innovative approach using electroceramic and ceramic particle as reinforcements, electroceramic reinforcements of pyroelectric lead barium niobate (PBNp) and piezoelectric lead lanthanum zirconate titanate (PLZTp) along with ceramic particle SiCpfor AMC fabrication, was carried out by Montalba et al. [41]. Multiple particle-reinforced AMCs were fabricated by applying ultrasonic treatment; hence, superior particle dispersion and remarkable wettability were observed.

Accumulative roll bonding (ARB) is a remarkable technique applied for AMC fabrication. Roll bonding is carried out with imposing reinforcement into the matrix. An ultra-fine grain structure is achieved, consequently strengthening the fabricated rolled sheet [42], [43]. Rezayat et al. [44] investigated the effect of ARB cycles on AMCs. Tensile strength increased with ARB cycles and maximum 256 MPa reported for eight cycles with only 2 vol.% Al2O3p, which is five times higher than Al.

The functionally graded composite material (FGCM) is a relatively advanced composite, in which microstructure and material composition are diverse in controlling the physical and mechanical properties. The FGCM has been successfully fabricated through SC followed by the centrifugal casting (CG) method [45], [46], [47]. Savaş et al. [48] fabricated the SiCp-reinforced AMCs through the CG method, and at the outer region, maximum percentage of particles were observed; hence, a higher hardness value has been reported.

Abdizadeh et al. [49] fabricated the MgOp-reinforced AMCs using SC and PM. Temperature values selected for SC were 800°C, 850°C, and 950°C, while 575°C, 600°C, and 625°C were selected for PM. Better homogeneous distribution and less porosity level in SC were observed, thus better properties were achieved than PM, within the decided range of temperatures. Temperatures of 625°C for PM and 850°C for SC were optimum for the best value of mechanical properties.

The indigenously developed enhanced SC process, consisting of two steps of stirring method, was used for AMCs fabrication. Better reinforcement distribution was observed. The addition of 1% Mg during the stirring improved wettability, and the addition of argon gas avoided unnecessary reaction of molten aluminum with the atmosphere. As a result, AMC performance has been improved remarkably through this process [50]. Mg addition reduces the surface energy of Al, which decreases the contact angle between the molten matrix and the reinforcement, consequently promoting wettability [51]. In in situ powder metallurgy (ISPM), Akhlaghi and Zare-Bidaki [52] combined the SC and PM processes and obtained an enhancement in the AMC properties.

By using any of above suitable, economical, or feasible fabrication processes, it is necessary to evaluate the tribological, mechanical, electrical, and corrosion performance of AMCs. The tribological aspects of diversified reinforcement on AMCs have been already reviewed [53]. In the present article, an attempt is made to review the effect of diversified reinforcement on mechanical characterization in AMCs.

4 Mechanical characterization

The mechanical properties are very important for any material with the application of load, which determine the usefulness of a material in a specific product application [54]. Tensile and compressive strengths are the maximum stresses attained before fracture under tensile and compressive loading, respectively. Resistance against deformation is the modulus (elastic modulus), while flexural strength can be calculated from the maximum load before fracture under flexural loading. The hardness is known as the resistance to plastic deformation, generally by indentation, cutting, or abrasion [55], [56]. The mechanical properties of AMCs are extensively governed by the properties of matrix, reinforcement, and reinforcement/metal interface [57].

The effect of various reinforcements, its percentage, size, temperature, processing time, wettability, fabrication process, and heat treatment (HT) are significant to derive the mechanical properties of AMCs. The present review is to deal with the mechanical characterization of Al-based composite with individual reinforcement and multiple reinforcements.

4.1 Aluminum matrix composite for individual reinforcement

The overall mechanical properties of AMCs increase when high strength ceramic particles are added to ductile aluminum. When only ceramic particles are reinforced with aluminum, it produces an individual reinforced AMC. The mechanical characterizations of the individual particulate-reinforced AMCs are listed in Table 1. By increasing the reinforcement percentage in AMCs, the deformation of the matrix material is restricted. Hence, the mechanical property except impact strength has been improved with increasing vol./wt.% of the reinforcements [58], [79].

Mechanical characterization of individual particulate reinforced AMCs.

| Sr. no. | Fabrication process | Type of Al | Reinforcing element | Heat treatment (HT) | Outcomes | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | % | Particle size (μm) | ||||||

| 1 | SC, CC and SQ | A356 | FAp | 5, 15 wt. | 13 | T6 | Compression strength of AMCs processed by SQ was better than the matrix | [22] |

| 2 | EMS | A359 | Al2O3p | 2, 4, 6, 8 wt. | 30 | – | For 8 wt.% Al2O3p-reinforced AMCs, tensile strength was 45% higher, and hardness was 58% higher than Al | [27] |

| 3 | ARB | Al 1050 | Al2O3p | 1, 2, 3 vol. | 0.47 | – | Tensile strengths of AMCs increased with ARB cycles | [44] |

| 4 | SC and PM | A356 | MgOp | 1.5,2.5, 5 vol. | 70 nm (nano size) | – | SC-processed AMCs have better enhancement of hardness and compressive strength than the PM method | [49] |

| 5 | Enhanced SC | Al 6061 | TiCp | 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 vol. | – | – | UTS improved considerably with maintaining percentage elongation | [50] |

| 6 | SC | Al 6061 | SiCp | 2, 4, 6 wt. | 150 | – | UTS and hardness of AMCs were increased with SiCp percentage, but ductility decreased | [58] |

| 7 | PM | Al | SiCp | 4.09, 7.5, 12.5,17.5, 20.91 vol. | 68, 86, 112, 138, 156 | – | Vol. fraction was most dominating factor for AMC hardness | [59] |

| 8 | SC | Al 2024 | Al2O3p | 10,20,30 wt. | 16, 32, 66 | – | Among all of AMCs, the 16-μm Al2O3p has maximum hardness and tensile strength | [60] |

| 9 | SC | Al 6061and Al 2618 | SiCpand Al2O3p | 20% | 11 for SiCpand21 for Al2O3p | T6 | 20% Al2O3P with 2618 Al has better tensile strength than 20% of Al2O3P with 6061 Al at 300°C–350°C temperature | [61] |

| 10 | CC | Al 7005, Al 6061 | Al2O3p | 10, 20 vol. | – | T6 | Tensile strength decreased, and ductility increased significantly at 250°C | [62] |

| 11 | SC | A 356 | Al2O3p | 1.5 vol. | 20 nm | T6 | 4 min stirring offered maximum hardness and compressive strength than 8, 12, and 16 min | [63] |

| 12 | PM | Al | Al2O3p | 5 wt. | 165 | – | Micro hardness increased with milling time | [64] |

| 13 | PM | Al 6061 | MoSi2 | 15 vol. | <3 and 10–45 | Solution heat treated | UTS improved with milling time without losing ductility | [65] |

| 14 | Pressureless sintering | Al 6061 | SiCp | 10 wt. | 23 or 7 | Solution treated, quenched, and aged | 7 μm SiCp-reinforced AMCs have better strength than 23 μm size | [66] |

| 15 | SC | AlSi5 | SiCp | 9, 13, 17, 22, 26 vol. | 15–30 | – | Extrusion process improved yield strength and tensile strength approximately 40% | [67] |

| 16 | Hot isosta. Press. | Al 2124 | SiCp | 26 vol. | 3 | T4 | T4 treatment, performed after forging, was suitable for property enhancement | [68] |

| 17 | Molten metal process | AA 2618 | Al2O3p | 20 vol. | – | T6 | Forging improved ultimate strength and hardness of AMCs at room as well as at high temperature | [69] |

| 18 | PM | 7034 | SiCp | 15 vol. | – | Solution treated, quenched, and aged | Modulus and strength of AMCs decreased with increasing testing temperature | [70] |

| 19 | SC | Al 6061 | SiCp | 15 vol. | 23 | Solution treated, quenched, and aged | Interaction of heat treatment parameter has higher influence than individual parameter effect | [71] |

| 20 | SC | LM6 | SiO2p | 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 vol. | 65 | – | Compressive strength of SiO2pwas more effective than tensile strength of AMCs | [72] |

| 21 | SC | 7075 | B4Cp | 5, 10, 15, 20 vol. | 16–20 | T6 | Ultimate tensile, compression, hardness, and flexural strength increased with B4Cp | [73] |

| 22 | PM | Al | Si3N4p | 5, 10, 15 wt. | 0.1–0.3 | – | 10% wt. Si3N4p enhanced better transverse rupture strength, density, and hardness than 5% and 15% wt. | [74] |

| 23 | PI | Al-4.5% Mg | BNp | 5, 7.5 vol. | 8 | Solution treat. | Tensile strength increased due to formation of AlN and grain refinement | [75] |

| 24 | SC | AA 2024 | B4Cp | 3, 5, 7, 10 vol. | 29, 71 | – | Coarser B4Cp dispersed more uniformly than finer B4Cp | [76] |

| 25 | Molten metal process | Al 6061 | Al2O3p | 10, 20 vol. | – | T6 | Elongation increased and tensile strength decreased when temperature was raised from 20°C to 250°C | [77] |

| 26 | SC | AlSi10Mg | RHAp | 3, 6, 9, 12 wt. | 50–75 | – | Tensile, compression strength, and hardness of AMCs enhanced with RHAp | [78] |

The effect of the matrix particle size (Al), vol. fraction, and particle size (SiCp) on the hardness of the AMCs was studied using the central composite design (CCD) method. A smaller Al particle size and a bigger SiCp size increase the hardness of the AMCs [59]. Kok [60] fabricated the AMCs through a vortex method and the subsequently applied pressure. The tensile strength and the hardness of the AMCs increased with decreasing Al2O3p size. The coarser particles were more uniformly dispersed, while fine Al2O3p agglomerated in the matrix material.

Vedani et al. [61] evaluated the tensile strength of SiCp and Al2O3p-reinforced AMCs at a temperature range of 300°C–500°C. They observed that 20% of SiCp with 2618 Al has a higher tensile strength than 20% of Al2O3p with 2618 Al. Ductility has been improved remarkably at high temperatures, especially with fine particle reinforcement, and 20% of Al2O3p with 2618 Al has a higher tensile strength than 20% of Al2O3p with 6061 Al within 300°C–350°C, which indicates that selection of the matrix alloy plays a crucial role for the enhancement of the mechanical property.

Ceschini et al. [62] have found tensile properties of Al2O3preinforced on 6061 and 7005 Al at ambient temperatures, 100°C, 150°C, and 250°C. The temperature up to 100°C did not have a noteworthy effect on tensile strength and ductility. The tensile strength decreased and the ductility increased notably at 250°C. The MgAl2O4 spinels present in composites may promote void nucleation at the interface. Hence, it resulted in interfacial decohesion at the interface and, furthermore, failure of the composite. At higher temperature, the matrix becames softer, which results easily pulling out of reinforcement from matrix.

Nano Al2O3p-reinforced AMCs have been fabricated via the SC method by altering the stirring time. It was observed that 4 min of stirring was better compared to 8, 12, and 16 min. Moreover, Cu and Al metallic powders were milled independently with nano Al2O3p-reinforced AMCs. Cu addition was found to be better than Al addition because Cu provided a better strengthening effect as well as better Al2O3p distribution in the AMCs [63].

Zebarjad and Sajjadi [64] studied the effect of milling times, varying from 20, 30, 75, 150, 270, 330, 450, 600 to 900 min on the Al2O3p-reinforced AMCs. The milled AMCs was found to be harder compared to the AMCs without milling. However, the hardness decreased with temperature in both the types. MoSi2p-reinforced AMCs was produced by Corrochano et al. [65] using PM. Ball milling has reduced the MoSi2p size and matrix grain size, which led to enhanced UTS with milling time without losing the ductility of the AMCs.

Wettability is the ability of the liquid to spread on a solid surface [9]. The wettability of the reinforcement in the melt is reduced with reinforcement size; consequently, the AMC quality is deteriorated. Mazaheri et al. [80] have improved the wettability by giving HT to B4Cp by heating at 800°C for 1 h and also added Na3AlF6 flux into the melt.

Lai and Chung [81] reported that SiCp reacts with Al at an elevated temperature as shown in equation (8). The brittle aluminum carbide formed has a tendency to weaken the interfacial bond between the matrix and the reinforcement. Thus, a small amount of SiCp is consumed due to the described reaction, which reduces the actual quantity of added SiCp. Moreover, silicon leads to non-homogeneous distribution of reinforcement in the matrix. Hence, the AMC quality deteriorates.

Ramesh et al. [82] performed electroless Ni-P coating on SiCp,which eliminates the above unwanted interfacial reaction. The metallic coating on the ceramic particles increases the surface energy of the ceramic particles, which improves the wettability by making a better contacting interface to metal with metal despite the metal being mixed with a ceramic [31]. Davidson and Regener [66] studied the tensile strength of Cu coated and uncoated SiCp with Al matrix. They observed a decohesion between the particulates and the matrix in the case of the uncoated particle-reinforced composite. Li et al. [83] observed an enhancement in the ultimate tensile strength for Bi2O3 coated on the aluminum borate whisker-reinforced AMCs. TiB2p-coated B4Cp-reinforced AMCs exhibited better tensile strength and hardness than uncoated AMCs [84].

Electroless Ni-P-coated Si3N4p-reinforced AMCs were fabricated by Ramesh et al. [85] through SC. They reported that interfacial region was free from any reaction during the fabrication of AMCs. Hence, a good interfacial bonding between matrix and reinforcement was observed. The UTS value was increased to 99% for 10 wt.% Ni-P-coated Si3N4p-reinforced AMCs compared with that of the matrix.

The secondary process like extrusion, rolling, and forging are also carried out on AMCs to improve the mechanical properties. Extrusion processes reduces the reinforcing particle size. Also, by reducing plastic deformation and pull out tendency of reinforcement from the matrix, composite properties can be enhanced [82]. Cöcen and Önel reported that extruded specimens have superior strength and ductility compared to cast specimens. In casted samples, the tensile strength of the AMCs increases up to 17 vol.% SiCp, and after that, upon further addition, it decreases, while tensile strength of the AMCs increase up to 26 vol.% SiCp for the extruded AMCs. The significant finding in this paper is that the extrusion process is more fruitful in the matrix with a higher reinforcement percentage for property enhancement [67].

The rolling process closes the pores and, thus, results in improved hardness and UTS of AMCs [86]. It also has been reported that hot rolled Al2O3p or carbon particle-reinforced AMCs have better tensile properties than cold rolled ones [87].

Badini et al. [68] reported that neither breaking of SiCp nor void formation occurs at interfaces during tensile testing at 300°C for forged AMCs. AlxFeNi intermetallic compounds have been observed in forged specimens, which promoted dynamic recrystallization of the matrix during the forging. Hence, dislocation motion was inhibited, which leads to enhanced stability of the matrix at a high temperature [69].

HT is a heating and cooling process used on metal for further enhancement of the mechanical properties and is successfully applied on the AMCs. Srivatsan and Al-Hajri [70] concluded that UTS at 27°C of peak-aged was lower than under-aged specimens, but at 120°C, UTS was nearly similar for both heat-treated samples. Mahadevan et al. [71] successfully modeled Brinell hardness (Y) as expressed in equation (9), with HT parameter like aging time (At), solutionizing time (St), and aging temperature (AT). The correlation coefficient (R) was 0.82, which indicates that the developed model has good correlation with the experimental data.

It has been reported that extrusion with T6 HT showed better tensile properties and hardness compared to gravity-casted SiCp-reinforced AMCs, due to better equiaxed structure and homogeneous particle distribution in the matrix [88].

Sulaiman et al. [72] investigated the SiO2p-reinforced AMCs using the CO2 sand molding method. Tensile strength and modulus decreased with an increase in SiO2p. Because of the compressive nature of SiO2p, compressive strength has better influence than tensile strength. For 5 wt.% CNT-reinforced AMCs, improvement up to 50% in tensile strength as well as 23% in stiffness compared with those of pure Al has been observed [89].

Baradeswaran and Elaya Perumal [73] observed that the addition of K2TiF6 eliminates oxide formation, which encourages wettability. Ceramic reinforcement resists dislocation motion, which offers resistance against fracture. B4Cp provides more restriction on plastic flow during deformation and tends to improve compressive strength.

Arik [74] observed more homogenous Si3N4pdispersion in mechanical alloying processes than in conventional mixing in the Al matrix and reported significant improvement in AMC properties. A large amount of Si3N4p in the matrix resulted in cold welding as well as easy fracturing. In this investigation, 10% of the Si3N4p-reinforced AMCs have demonstrated better transverse rupture strength, density, and hardness compared with 5% and 15% of the Si3N4p-reinforced AMCs.

Lee et al. [75] studied the pressureless infiltration (PI) method using 5% and 7.5% vol. BNp-reinforced AMCs. Aluminum nitride formed due to the reaction between Al and BNp increases the UTS as shown in the equation:

SiCp-reinforced AMCs have exhibited better ultimate tensile strength, hardness, and compressive strength compared with Al2O3p-reinforced AMCs and cenosphere-reinforced AMCs. Another important finding was that 8% of SiCp-reinforced AMCs have exhibited better ultimate tensile strength and compressive strength compared with 12% and 16% SiCp-reinforced AMCs, while the hardness of 16% SiCp-reinforced AMCs was better than the 8% and 12% SiCp-reinforced AMCs [90].

Abdizadeh et al. [91] investigated the mechanical properties of AMCs by comparing ZrSiO4p and TiB2p reinforcement. They also evaluated the effect of the processing temperature of AMCs, fabricated through the SC process. TiB2phas better wettability than ZrSiO4p, so TiB2p-reinforced AMCs have better performance. TiB2phas a lower heat expansion coefficient than of that of ZrSiO4p; hence, TiB2p-reinforced AMCs have been found to be better at 850°C and ZrSiO4p-reinforced AMCs at 750°C.

Fly ash is industrial waste, low in cost and successfully used as reinforcement for fabrication of AMCs [92]. The UTS and hardness increased with the addition of FAp [93], while the impact strength and ductility of AMCs decreased [94].

Rice husk is a commonly available agricultural element, successfully used as reinforcement for AMC fabrication [95], [96]. Tensile strength, compressive strength, and hardness of AMCs have been enhanced, while ductility decreased with increasing RHAp. The RHAp act as barriers and harden the Al matrix [78].

Particle swarm optimization, multiple linear regression and genetic algorithm, etc., techniques are frequently used for modeling and optimization of the mechanical properties. Shabani and Mazahery [86] have proposed the hybrid PSO-GA-based novel method, which predicts the mechanical properties of the Al2O3p-reinforced AMCs with better accuracy and reliability than the single optimization method.

Lee et al. [97] have modeled the particle clustering effect of the ceramic particle-reinforced AMCs. The model was compared with the TiCp-reinforced AMCs fabricated through PM. The representative volume element based on the tetrakaidecahedral grain boundary structure was reconstructed for 5 vol.% TiCp-reinforced AMCs through modified random sequential adsorption. The clustered particle arrangement model has a better agreement than the random particle arrangement model with experimental results.

4.2 Aluminum matrix composite based on multiple reinforcements

When at least two reinforcements are present in the matrix, they form as multiple-reinforced AMCs. By cooperative effects of various reinforcement combinations, the AMCs tend to further enrich the mechanical properties. Table 2 shows the mechanical characterization of the multiple particulate-reinforced AMCs.

Mechanical characterization of multiple particulate-reinforced AMCs.

| Sr. no. | Fabrication process | Type of Al | Reinforcing element | Heat treatment (HT) | Outcomes | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | % | Particle size (μm) | ||||||

| 1 | SC and CC3 | Al 6061 | SiCp and FAp | SiCp 7.5, 10 and FAp7.5 wt. | – | – | Enhancement of tensile strength and hardness with adding of SiCp and FAp | [98] |

| 2 | SC | Al 7075 | Al2O3pand Grp | 2, 4, 6, 8 wt. of Al2O3p and 5 wt. Grp | 16 | T6 | Addition of Al2O3p increases the tensile strength, compression strength, flexural strength, and hardness | [99] |

| 3 | SC | A332 | Al2O3pand SiCp | 10 vol. | 2 to 87 | – | Bending strength and hardness resistance decreased with increasing particle size | [100] |

| 4 | SC | A332 | Al2O3pand SiCp | 10 vol. | 2 to 87 | – | Tensile strength increased with decreasing particle size | [101] |

| 5 | CC | Al with 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Cu wt.% | SiCp | 5, 10 vol. | 200 mesh size | – | Porosity increased with SiCpand hardness increased with SiCpand Cu addition | [102] |

SiCpceramic and FApindustrial by-products have been used for the enhancement of the tensile strength of the AMCs from 173 MPa to 213 MPa. Also, the hardness value increased from 69.53 HV to 78.8 HV [98]. Mahendra and Radhakrishna [103] also observed that the tensile strength, compressive strength and impact strength increased with SiCp and FAp% in the AMCs.

The strength of the AMCs has been increased by the addition of the hard ceramic Al2O3pin the matrix. The compressive strength of the 8-wt.% Al2O3p-reinforced AMCs was 10% higher than that of the matrix, while the flexural strength of the 8-wt.% Al2O3p-reinforced AMCs was increased up to 23% compared with that of the Al 7075. The Grp addition in the AMCs tends to form a thin layer on the tribo surface, which reduces wear, even though hardness is reduced [99]. Baradeswaran et al. [104] have studied the effect of 10 wt.% of B4Cp and 5 wt.% of Grp in AA 6061 and AA 7075 matrix. It has been observed that hybrid-reinforced AA 7075 has found better tensile strength and hardness than hybrid-reinforced AA 6061.

Kumar et al. [105] have investigated the wear performance of the 4-wt.% Grp and the 1 to 4 wt.% of the WCp-reinforced AMCs. The AMCs became more brittle by increasing WCp percentage; another important finding was that Al6061 with 3 wt.% WCp has higher hardness than that of the 4-wt.% WCp composite.

Thermomagnetic treatment was applied by Li et al. on aluminum borate (Al18B4O33) and iron oxide (Fe3O4)-reinforced AMCs. The specimens were subjected to thermomagnetic treatment at 100°C for 1 h with a pulsed magnetic field of 400 kA/m. A higher tensile strength has been reported after thermomagnetic treatment [106].

A neural network is capable of identifying trends from the given data; thus, it is frequently used for prediction. The neural network result has good agreement with the experimental data, for tensile strength, bending strength, and hardness for the 2-, 4-, 8-, 10-, 16-, 20-, 27-, 38-, 45-, 49-, 53-, 60-, 67-, 75-, and 87-μm particle size-reinforced AMCs [100], [101]. Comparison of the different algorithms like Levenberg-Marquardt, quasi-Newton, resilient back propagation and variable learning rate back propagation for the prediction of the bending strength and hardness carried out using the Al2O3p/SiCp-reinforced AMCs by changing the size of the particle was done. The Levenberg-Marquardt was found to be the fastest converging algorithm along with the highest accuracy among all the algorithms [107].

5 Product application of AMCs

The AMCs are found to have excellent mechanical properties; hence, they are used for product development. The product applications of the AMCs with its mechanical performance are mentioned in Table 3.

Product applications of AMCs.

| Sr. no. | Type of Al | Fabrication process | Reinforcing particle | Product application | Ref. no. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | % | Size (μm) | |||||

| 1 | Al | PM | Sip and SiCp | Sip (10, 12 wt.) and SiCp (5, 10 wt.) | – | Air conditioner compressor piston | [108] |

| 2 | Al | PM as well as SC | SiCp | 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 wt. | – | Poppet valve guide | [109] |

| 3 | A359 | Investment casting (IC) | SiCp and B4Cp | 20SiCp and 7.5 B4Cp | 35–38 μm for both SiCp and B4Cp | Pick-holder | [110] |

| 4 | A 356 FGCM | SC and CG | SiCp | 20 wt. | 23 | Brake disc | [111] |

| 5 | Al-Si alloy | SQ | Al2O3pand Nip | 2, 3 wt. of Al2O3pand 5, 10, 15 wt. of Ni | 60 nm for Al2O3p and 6 μm for Nip | Piston | [112] |

| 6 | AA 2124 | PM | SiCp, B4Cp, Al2O3p | 10, 20, 30 vol. | SiCp (2, 20, 53, 167), B4C (1–7), Al2O3, (1, 20–50) | Automobile cam material | [113] |

In the automobile, the piston of the compressor used in the air conditioner was fabricated successfully with SiCp and Sip-reinforced AMCs through PM, followed by extrusion (500°C with 8:1 extrusion ratio) and the forging process. Grain size decreased from 47 to 19 μm due to extrusion. Wear resistance, tensile strength and hardness of the AMCs were enhanced with the addition of SiCp[108].

SiCp (20–30 wt.%)-reinforced AMCs have been fabricated through the SC and PM methods. The hardness, radial crushing load, and wear resistance of SiCp-reinforced AMCs was found to be better than cast iron; hence, it was found to be a possible replacement for CI as a poppet valve guide [109].

An electronic package for a remote power controller were fabricated using SiCp-reinforced AMCs, which gave high thermal conductivity, controllable coefficient of thermal expansion, and low density [114], [115]; hence, this is used in communication satellites [116]. The SiCp-reinforced AMCs have found utility in microprocessor and optoelectronic packaging applications [9]. Al2O3 fiber-reinforced AMCs have better strength and stiffness; hence, they are suitable for power transmission cables [9], [117].

A high-gain antenna boom for the Hubble space telescope was fabricated using the Gr fibre-reinforced AMCs through the diffusion bonding method. The AMCs provide better stiffness, low coefficient of thermal expansion, and better electrical conductivity; hence, they are useful in space applications [116]. The SiCp-reinforced AMCs have been used as a fan-exit guide vane of the Pratt and Whitney engine for the Boeing 777 [9]. Flight control hydraulic manifolds have been fabricated by 40 vol.% SiCp-reinforced AMCs and are a successful utility in aerospace applications [17].

The IC process has been successfully deployed to fabricate the pick-holder, a part used in the textile sector. The AMCs have better microhardness and wear resistance than the matrix alloy, and also, it was observed that the particles were uniformly distributed in the pick-holder [110].

A brake disc using FGCM was manufactured via the SC and CG methods. Because of the action of the centrifugal force, the distribution of the reinforcement was varied in different zones of the brake disc. The minimum reinforcement distribution at the inner periphery and the maximum reinforcement distribution at the outer periphery were observed; hence, more hardness was observed at the outer periphery of the brake disc [111].

El-Labban et al. [112] studied the effect of nano Al2O3pand micro Nip-reinforced Al-Si-based piston alloy on mechanical behavior. They reported the highest UTS for 5 wt.% Ni and 2 wt.% nano Al2O3p-reinforced AMCs. Moreover, ductility improved due to Al2O3p and Nip addition in matrix.

An automobile cam was fabricated by Karamış et al. [113], and the hardness of the GGG40 cam material was compared with those of SiCp, Al2O3p, and B4Cp-reinforced AA2124. The hardness of the 20-μm-size SiCp 30% vol. was approximately 90% compared to the induction-hardened GGG40 material. The AMCs reinforced with B4Cp or SiCp were reported to be superior in specific wear resistance compared with GGG40; hence, the product application for the automobile cam profiles was found.

6 Concluding remarks

The objective of the present paper was to highlight the current research on the fabrication processes and the mechanical characterization of the AMCs, including product application. The following concluding remarks are drawn from the present work:

The most commonly used fabrication techniques for the production of AMCs are briefly discussed in the present article. Among all of them, SC and PM are more frequently used. Secondary fabrication processes like extrusion, rolling and forging are successfully implemented for the further enrichment of mechanical properties. Development of re-cycling technology for the AMCs is still an open-ended area in which a lot of exclusive research can be done.

The mechanical properties of the AMCs depend upon the types of matrix, reinforcements (individual, multiple, percentage, size, distribution in matrix), wettability and reaction during the fabrication process. Industrial and agricultural waste used as a reinforcing element minimized the overall cost of the AMCs. Less work has been reported on the nano particle-reinforced composite, which requires more investigation for the fabrication process and mechanical property enhancement of nano composites.

Several modeling and simulation techniques have been developed for the prediction of mechanical properties. Integration of multiple modeling techniques predicts the response with higher accuracy and reliability than the individual method. However, the various fabrication processes involve multi-input parameters, which makes difficult to predict he mechanical properties exactly. Thus, comprehensive modeling and simulation for fabrication processes and mechanical characterization covering phenomenological interactions are yet to be fully explored.

AMCs have found successful use in space technology, aircraft industry, automobile component, electrical and electronic field, and other product applications. It is also concluded that exclusive research is required to explore the use of AMCs at efficient as well as economical scale.

Acknowledgments

This work is part of a research project supported by Gujarat Council on Science and Technology, Gujarat, India (GUJCOST) (GUJCOST/MRP/16-17/273). The authors express their gratitude toward the GUJCOST for providing financial support.

References

[1] Rao RN, Das S. Mater. Des. 2010, 31, 1200–1207.10.1016/j.matdes.2009.09.032Search in Google Scholar

[2] Song JI, Bong HD, Han KS. Scr. Metall. Mater. 1995, 33, 1307–1313.10.1016/0956-716X(95)00359-4Search in Google Scholar

[3] Park HC. Scr. Metall. Mater. 1992, 27, 465–470.10.1016/0956-716X(92)90212-WSearch in Google Scholar

[4] Huda Z, Edi P. Mater. Des. 2013, 46, 552–560.10.1016/j.matdes.2012.10.001Search in Google Scholar

[5] Kaw AK. Mechanics of Composite Materials, CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2005.10.1201/9781420058291Search in Google Scholar

[6] Clyne TW, Withers PJ. An Introduction to Metal Matrix Composites, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1995.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Chung DDL. Composite Materials: Science and Applications, Springer: London, 2010.10.1007/978-1-84882-831-5Search in Google Scholar

[8] Davim J, Ed. Machining of Metal Matrix Composites, Springer-Verlag: Berlin, 2012.10.1007/978-0-85729-938-3Search in Google Scholar

[9] Chawla N, Chawla KK. Metal Matrix Composites, Springer: Berlin, 2006.10.1002/9783527603978.mst0150Search in Google Scholar

[10] Gultekin D, Uysal M, Aslan S, Alaf M, Guler MO, Akbulut H. Wear 2010, 270, 73–82.10.1016/j.wear.2010.09.001Search in Google Scholar

[11] Zhang S, Wang F. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2007, 182, 122–127.10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2006.07.018Search in Google Scholar

[12] Ashby MF, Jones DRH. Engineering Materials 2: An Introduction to Microstructures, Processing and Design, Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, 2014.10.1016/B978-0-08-098205-2.00001-9Search in Google Scholar

[13] Baradeswaran A, Perumal AE, Davim J. J. Balkan Tribol. Assoc. 2014, 19, 230–239.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Basavarajappa S, Chandramohan G, Paulo Davim J. Mater. Des. 2007, 28, 1393–1398.10.1016/j.matdes.2006.01.006Search in Google Scholar

[15] Shah MA. Nanotechnology Applications for Improvements in Energy Efficiency and Environmental Management, IGI Global: Hershey, PA, 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Davim JP. Tribology of Nanocomposites, Springer: Berlin, 2013.10.1007/978-3-642-33882-3Search in Google Scholar

[17] Surappa MK. Sadhana 2003, 28, 319–334.10.1007/BF02717141Search in Google Scholar

[18] Leon CA, Drew RAL. J. Mater. Sci. 2000, 35, 4763–4768.10.1023/A:1004860326071Search in Google Scholar

[19] Asthana R. J. Mater. Sci. 1998, 33, 1959–1980.10.1023/A:1004334228105Search in Google Scholar

[20] Koli DK, Agnihotri G, Purohit R. Procedia Mater. Sci. 2014, 6, 567–589.10.1016/j.mspro.2014.07.072Search in Google Scholar

[21] Sajjadi SA, Ezatpour HR, Torabi Parizi M. Mater. Des. 2012, 34, 106–111.10.1016/j.matdes.2011.07.037Search in Google Scholar

[22] Rajan TPD, Pillai RM, Pai BC, Satyanarayana KG, Rohatgi PK. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2007, 67, 3369–3377.10.1016/j.compscitech.2007.03.028Search in Google Scholar

[23] Barekar N, Tzamtzis S, Dhindaw BK, Patel J, Hari Babu N, Fan Z. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2009, 18, 1230–1240.10.1007/s11665-009-9362-5Search in Google Scholar

[24] Dwivedi SP, Kumar S, Kumar A. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2012, 26, 3973–3979.10.1007/s12206-012-0914-5Search in Google Scholar

[25] Moffatt HK. Phys. Fluids A 1991, 3, 1336–1343.10.1063/1.858062Search in Google Scholar

[26] Yu H, Zhu M. Acta Metall. Sin. (Engl. Lett.) 2009, 22, 461–467.10.1016/S1006-7191(08)60124-6Search in Google Scholar

[27] Kumar A, Lal S, Kumar S. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2013, 2, 250–254.10.1016/j.jmrt.2013.03.015Search in Google Scholar

[28] Dwivedi SP, Sharma S, Mishra RK. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2015, 37, 57–67.10.1007/s40430-014-0138-ySearch in Google Scholar

[29] Dwivedi SP, Sharma S, Mishra RK. Procedia Mater. Sci. 2014, 6, 1524–1532.10.1016/j.mspro.2014.07.133Search in Google Scholar

[30] Hong S-J, Kim H-M, Huh D, Suryanarayana C, Chun BS. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2003, 347, 198–204.10.1016/S0921-5093(02)00593-2Search in Google Scholar

[31] Hashim J, Looney L, Hashmi MSJ. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 1999, 92–93, 1–7.10.1016/S0924-0136(99)00118-1Search in Google Scholar

[32] Hashim J, Looney L, Hashmi MSJ. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2002, 123, 251–257.10.1016/S0924-0136(02)00098-5Search in Google Scholar

[33] Wu TY, Guo N, Teh CY, Hay JXW. Theory and Fundamentals of Ultrasound, Advances in Ultrasound Technology for Environmental Remediation, Springer: Netherlands, 2013, pp 5–12.10.1007/978-94-007-5533-8_2Search in Google Scholar

[34] Eskin GI, Eskin DG. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2003, 10, 297–301.10.1016/S1350-4177(02)00158-XSearch in Google Scholar

[35] Puga H, Teixeira JC, Barbosa J, Seabra E, Ribeiro S, Prokic M. Mater. Lett. 2009, 63, 2089–2092.10.1016/j.matlet.2009.06.059Search in Google Scholar

[36] Liu Z, Han Q, Li J, Huang W. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2012, 212, 365–371.10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2011.09.021Search in Google Scholar

[37] Kai X, Tian K, Wang C, Jiao L, Chen G, Zhao Y. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 668, 121–127.10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.01.152Search in Google Scholar

[38] Mohanty P, Mishra Dilip K, Varma S, Mishra K, Padhi P. Sci. Eng. Compos. Mater. 2016, 23, 481.10.1515/secm-2014-0242Search in Google Scholar

[39] Harichandran R, Selvakumar N. Arch. Civil Mech. Eng. 2016, 16, 147–158.10.1016/j.acme.2015.07.001Search in Google Scholar

[40] Liu Z, Han Q, Li J. Compos B: Eng. 2011, 42, 2080–2084.10.1016/j.compositesb.2011.04.004Search in Google Scholar

[41] Montalba C, Eskin DG, Miranda A, Rojas D, Ramam K. Mater. Des. 2015, 84, 110–117.10.1016/j.matdes.2015.06.101Search in Google Scholar

[42] Kitazono K, Sato E, Kuribayashi K. Scr. Mater. 2004, 50, 495–498.10.1016/j.scriptamat.2003.10.035Search in Google Scholar

[43] Alizadeh M, Paydar MH. J. Alloys Compd. 2010, 492, 231–235.10.1016/j.jallcom.2009.12.026Search in Google Scholar

[44] Rezayat M, Akbarzadeh A, Owhadi A. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2012, 43, 261–267.10.1016/j.compositesa.2011.10.015Search in Google Scholar

[45] Rajan TPD, Pai BC. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2010, 62, 383–389.10.1007/s12666-009-0067-0Search in Google Scholar

[46] Duque NB, Melgarejo ZH, Suárez OM. Mater. Charact. 2005, 55, 167–171.10.1016/j.matchar.2005.04.005Search in Google Scholar

[47] Karun AS, Rajan T, Pillai U, Pai B, Rajeev V, Farook A. J. Compos. Mater. 2016, 50, 2255–2269.10.1177/0021998315602946Search in Google Scholar

[48] Savaş Ö, Kayıkcı R, Fiçici F, Çolak M, Deniz G, Varol F. Sci. Eng. Compos. Mater. 2016, 23, 155–159.10.1515/secm-2014-0141Search in Google Scholar

[49] Abdizadeh H, Ebrahimifard R, Baghchesara MA. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2014, 56, 217–221.10.1016/j.compositesb.2013.08.023Search in Google Scholar

[50] Gopalakrishnan S, Murugan N. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2012, 43, 302–308.10.1016/j.compositesb.2011.08.049Search in Google Scholar

[51] Hashim J, Looney L, Hashmi MSJ. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2001, 119, 324–328.10.1016/S0924-0136(01)00975-XSearch in Google Scholar

[52] Akhlaghi F, Zare-Bidaki A. Wear 2009, 266, 37–45.10.1016/j.wear.2008.05.013Search in Google Scholar

[53] Mistry JM, Gohil PP. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2017, 231, 399–421.10.1177/1350650116658572Search in Google Scholar

[54] Chung DD, Composite Materials: Science and Applications, Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, 2010.10.1007/978-1-84882-831-5Search in Google Scholar

[55] Dowling NE. Mechanical Behavior of Materials: Engineering Methods for Deformation, Fracture, and Fatigue, Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, 1993.Search in Google Scholar

[56] Ashby MF, Jones DRH, Engineering Materials 1: An Introduction to Their Properties and Applications, Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, 1996.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Taheri-Nassaj E, Kobashi M, Choh T. Scr. Metall. Mater. 1995, 32, 1923–1929.10.1016/0956-716X(95)00083-8Search in Google Scholar

[58] Veeresh Kumar GB, Rao CSP, Selvaraj N. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2012, 43, 1185–1191.10.1016/j.compositesb.2011.08.046Search in Google Scholar

[59] Diler EA, Ipek R. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2013, 50, 371–380.10.1016/j.compositesb.2013.02.001Search in Google Scholar

[60] Kok M. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2005, 161, 381–387.10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2004.07.068Search in Google Scholar

[61] Vedani M, D’Errico F, Gariboldi E. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2006, 66, 343–349.10.1016/j.compscitech.2005.04.045Search in Google Scholar

[62] Ceschini L, Minak G, Morri A. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2006, 66, 333–342.10.1016/j.compscitech.2005.04.044Search in Google Scholar

[63] Karbalaei Akbari M, Baharvandi HR, Mirzaee O. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2013, 52, 262–268.10.1016/j.compositesb.2013.04.038Search in Google Scholar

[64] Zebarjad SM, Sajjadi SA. Mater. Des. 2007, 28, 2113–2120.10.1016/j.matdes.2006.05.020Search in Google Scholar

[65] Corrochano J, Lieblich M, Ibáñez J. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2011, 42, 1093–1099.10.1016/j.compositesa.2011.04.014Search in Google Scholar

[66] Davidson AM, Regener D. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2000, 60, 865–869.10.1016/S0266-3538(99)00151-7Search in Google Scholar

[67] Cöcen Ü, Önel K. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2002, 62, 275–282.10.1016/S0266-3538(01)00198-1Search in Google Scholar

[68] Badini C, La Vecchia GM, Fino P, Valente T. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2001, 116, 289–297.10.1016/S0924-0136(01)01056-1Search in Google Scholar

[69] Ceschini L, Minak G, Morri A. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2009, 69, 1783–1789.10.1016/j.compscitech.2008.08.027Search in Google Scholar

[70] Srivatsan TS, Al-Hajri M. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2002, 33, 391–404.10.1016/S1359-8368(02)00025-2Search in Google Scholar

[71] Mahadevan K, Raghukandan K, Senthilvelan T, Pai BC, Pillai UTS. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2006, 171, 314–318.10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2005.06.073Search in Google Scholar

[72] Sulaiman S, Sayuti M, Samin R. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2008, 201, 731–735.10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2007.11.221Search in Google Scholar

[73] Baradeswaran A, Elaya Perumal A. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2013, 54, 146–152.10.1016/j.compositesb.2013.05.012Search in Google Scholar

[74] Arik H. Mater. Des. 2008, 29, 1856–1861.10.1016/j.matdes.2008.03.010Search in Google Scholar

[75] Lee KB, Sim HS, Heo SW, Yoo HR, Cho SY, Kwon H. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2002, 33, 709–715.10.1016/S1359-835X(02)00011-8Search in Google Scholar

[76] Canakci A, Arslan F, Varol T. Sci. Eng. Compos. Mater. 2014, 21, 505–515.10.1515/secm-2013-0118Search in Google Scholar

[77] Gariboldi E, Lo Conte A. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2008, 68, 260–267.10.1016/j.compscitech.2007.03.014Search in Google Scholar

[78] Saravanan SD, Kumar MS. Procedia Eng. 2013, 64, 1505–1513.10.1016/j.proeng.2013.09.232Search in Google Scholar

[79] Lakshmipathy J, Kulendran B. Sci. Eng. Compos. Mater. 2015, 22, 573–582.10.1515/secm-2013-0268Search in Google Scholar

[80] Mazaheri Y, Meratian M, Emadi R, Najarian AR. Mater. Sci. Eng.: A. 2013, 560, 278–287.10.1016/j.msea.2012.09.068Search in Google Scholar

[81] Lai S-W, Chung DDL. J. Mater. Chem. 1996, 6, 469–477.10.1039/JM9960600469Search in Google Scholar

[82] Ramesh CS, Keshavamurthy R, Naveen GJ. Wear 2011, 271, 1868–1877.10.1016/j.wear.2010.12.078Search in Google Scholar

[83] Li ZJ, Wang LD, Yue HY, Fei WD. J. Mater. Sci. 2007, 42, 9355–9358.10.1007/s10853-007-1862-9Search in Google Scholar

[84] Mazahery A, Shabani MO. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2013, 66, 171–176.10.1007/s12666-012-0238-2Search in Google Scholar

[85] Ramesh CS, Keshavamurthy R, Channabasappa BH, Ahmed A. Mater. Sci. Eng.: A. 2009, 502, 99–106.10.1016/j.msea.2008.10.012Search in Google Scholar

[86] Shabani MO, Mazahery A. Eng. Comput. 2014, 30, 559–568.10.1007/s00366-012-0299-1Search in Google Scholar

[87] Daoud A, El-Bitar T, El-Azim AA. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2003, 12, 390–397.10.1361/105994903770342908Search in Google Scholar

[88] Sahin I, Akdogan Eker A. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2011, 20, 1090–1096.10.1007/s11665-010-9738-6Search in Google Scholar

[89] Esawi AMK, Morsi K, Sayed A, Taher M, Lanka S. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2010, 70, 2237–2241.10.1016/j.compscitech.2010.05.004Search in Google Scholar

[90] Ekka KK, Chauhan S, Varun. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J: J. Eng. Tribol. 2014, 228, 682–691.10.1177/1350650114526581Search in Google Scholar

[91] Abdizadeh H, Baharvandi HR, Moghaddam KS. Mater. Sci. Eng.: A. 2008, 498, 53–58.10.1016/j.msea.2008.07.009Search in Google Scholar

[92] Rohatgi PK. JOM. 1994, 46, 55–59.10.1007/BF03222635Search in Google Scholar

[93] Ramachandra M, Radhakrishna K. J. Mater. Sci. 2005, 40, 5989–5997.10.1007/s10853-005-1303-6Search in Google Scholar

[94] Kumar KR, Mohanasundaram KM, Subramanian R, Anandavel B. Sci. Eng. Compos. Mater. 2014, 21, 181–189.10.1515/secm-2013-0006Search in Google Scholar

[95] Majeed K, Hassan A, Bakar AA, Jawaid M. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2016, 29, 1003–1019.10.1177/0892705714554492Search in Google Scholar

[96] Alaneme KK, Adewale TM, Olubambi PA. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2014, 3, 9–16.10.1016/j.jmrt.2013.10.008Search in Google Scholar

[97] Lee WJ, Kim YJ, Kang NH, Park IM, Park YH. Mech. Compos. Mater. 2011, 46, 639–648.10.1007/s11029-011-9177-ySearch in Google Scholar

[98] David Raja Selvam J, Robinson Smart DS, Dinaharan I. Energy Procedia 2013, 34, 637–646.10.1016/j.egypro.2013.06.795Search in Google Scholar

[99] Baradeswaran A, Elaya Perumal A. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2014, 56, 464–471.10.1016/j.compositesb.2013.08.013Search in Google Scholar

[100] Altinkok N, Koker R. Mater. Des. 2004, 25, 595–602.10.1016/j.matdes.2004.02.014Search in Google Scholar

[101] Altinkok N, Koker R. Mater. Des. 2006, 27, 625–631.10.1016/j.matdes.2005.01.005Search in Google Scholar

[102] Hassan AM, Alrashdan A, Hayajneh MT, Mayyas AT. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2009, 209, 894–899.10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2008.02.066Search in Google Scholar

[103] Mahendra KV, Radhakrishna K. J. Compos. Mater. 2010, 44, 989–1005.10.1177/0021998309346386Search in Google Scholar

[104] Baradeswaran A, Vettivel SC, Elaya Perumal A, Selvakumar N, Franklin Issac R. Mater. Des. 2014, 63, 620–632.10.1016/j.matdes.2014.06.054Search in Google Scholar

[105] Kumar GV, Swamy A, Ramesha A. J. Compos. Mater. 2012, 46, 2111–2122.10.1177/0021998311430156Search in Google Scholar

[106] Li G, Fei WD, Li Y. J. Mater. Sci. 2005, 40, 511–514.10.1007/s10853-005-6116-0Search in Google Scholar

[107] Koker R, Altinkok N, Demir A. Mater. Des. 2007, 28, 616–627.10.1016/j.matdes.2005.07.021Search in Google Scholar

[108] Lee HS, Yeo JS, Hong SH, Yoon DJ, Na KH. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2001, 113, 202–208.10.1016/S0924-0136(01)00680-XSearch in Google Scholar

[109] Purohit R, Sagar R. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2010, 51, 685–698.10.1007/s00170-010-2637-zSearch in Google Scholar

[110] Previtali B, Pocci D, Taccardo C. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2008, 39, 1606–1617.10.1016/j.compositesa.2008.07.001Search in Google Scholar

[111] Babu KV, Jappes JW, Rajan T, Uthayakumar M. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L: J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2016, 230, 182–189.10.1177/0954405415573850Search in Google Scholar

[112] El-Labban HF, Abdelaziz M, Mahmoud ERI. J. King Saud Univ. Eng. Sci. 2016, 28, 230–239.10.1016/j.jksues.2014.04.002Search in Google Scholar

[113] Karamış MB, Alper Cerit A, Selçuk B, Nair F. Wear 2012, 289, 73–81.10.1016/j.wear.2012.04.012Search in Google Scholar

[114] Thaw C, Minet R, Zemany J, Zweben C. JOM 1987, 39, 55.10.1007/BF03259000Search in Google Scholar

[115] Miracle DB. Affordable Metal-Matrix Composites for High Performance Applications II, John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, 2001, pp 1–22.Search in Google Scholar

[116] Rawal SP. JOM 2001, 53, 14–17.10.1007/s11837-001-0139-zSearch in Google Scholar

[117] Miracle DB. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2005, 65, 2526–2540.10.1016/j.compscitech.2005.05.027Search in Google Scholar

©2018 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Research review of diversified reinforcement on aluminum metal matrix composites: fabrication processes and mechanical characterization

- Original articles

- On the mechanisms of modal damping in FRP/honeycomb sandwich panels

- Innovative experimental and finite element assessments of the performance of CFRP-retrofitted RC beams under fatigue loading

- Mixed-mode I/III fracture toughness of polymer matrix composites toughened with waste particles

- A novel analytical curved beam model for predicting elastic properties of 3D eight-harness satin weave composites

- Microwave absorption and mechanical properties of double-layer cement-based composites containing different replacement levels of fly ash

- Electrical and rheological properties of carbon black and carbon fiber filled low-density polyethylene/ethylene vinyl acetate composites

- Effect of neutron irradiation on neat epoxy resin stability in shielding applications

- Study on the relation between microstructural change and compressive creep stress of a PBX substitute material

- Chemical synthesis and densification of a novel Ag/Cr2O3-AgCrO2 nanocomposite powder

- Reinforcing polypropylene with calcium carbonate of different morphologies and polymorphs

- Fabrication, mechanical, thermal, and electrical characterization of epoxy/silica composites for high-voltage insulation

- Synergy of cashew nut shell filler on tribological behaviors of natural-fiber-reinforced epoxy composite

- Fabrication and Failure Prediction of Carbon-alum solid composite electrolyte based humidity sensor using ANN

- Investigation of three-body wear of dental materials under different chewing cycles

- Structural and physico-mechanical characterization of closed-cell aluminum foams with different zinc additions

- Mechanical performance of polyester pin-reinforced foam filled honeycomb sandwich panels

- Effect of chemical treatment on thermal properties of hair fiber-based reinforcement of HF/HDPE composites

- Indium doping in sol-gel synthesis of In-Sm co-doped xIn-0.05%Sm-TiO2 composite photocatalyst

- Effect of the meso-structure on the strain concentration of carbon-carbon composites with drilling hole

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Research review of diversified reinforcement on aluminum metal matrix composites: fabrication processes and mechanical characterization

- Original articles

- On the mechanisms of modal damping in FRP/honeycomb sandwich panels

- Innovative experimental and finite element assessments of the performance of CFRP-retrofitted RC beams under fatigue loading

- Mixed-mode I/III fracture toughness of polymer matrix composites toughened with waste particles

- A novel analytical curved beam model for predicting elastic properties of 3D eight-harness satin weave composites

- Microwave absorption and mechanical properties of double-layer cement-based composites containing different replacement levels of fly ash

- Electrical and rheological properties of carbon black and carbon fiber filled low-density polyethylene/ethylene vinyl acetate composites

- Effect of neutron irradiation on neat epoxy resin stability in shielding applications

- Study on the relation between microstructural change and compressive creep stress of a PBX substitute material

- Chemical synthesis and densification of a novel Ag/Cr2O3-AgCrO2 nanocomposite powder

- Reinforcing polypropylene with calcium carbonate of different morphologies and polymorphs

- Fabrication, mechanical, thermal, and electrical characterization of epoxy/silica composites for high-voltage insulation

- Synergy of cashew nut shell filler on tribological behaviors of natural-fiber-reinforced epoxy composite

- Fabrication and Failure Prediction of Carbon-alum solid composite electrolyte based humidity sensor using ANN

- Investigation of three-body wear of dental materials under different chewing cycles

- Structural and physico-mechanical characterization of closed-cell aluminum foams with different zinc additions

- Mechanical performance of polyester pin-reinforced foam filled honeycomb sandwich panels

- Effect of chemical treatment on thermal properties of hair fiber-based reinforcement of HF/HDPE composites

- Indium doping in sol-gel synthesis of In-Sm co-doped xIn-0.05%Sm-TiO2 composite photocatalyst

- Effect of the meso-structure on the strain concentration of carbon-carbon composites with drilling hole