Abstract

Human skeletal remains are routinely used to examine cultural and biological aspects of past populations. Yet, archaeological specimens are frequently fragmented/incomplete and so excluded from analyses. This leads to decreased sample sizes and to potentially biased results. Digital methods are now frequently used to restore/estimate the original morphology of fragmented/incomplete specimens. Such methods include 3D digitisation and Geometric Morphometrics (GM). The latter is also a solidly established method now to examine morphology. In this study, we use GM-based methods to estimate the original morphology of incomplete Mesolithic and Chalcolithic mandibles originating from present Portugal and perform ensuing morphological analyses. Because mandibular morphology is known to relate to population history and diet, we hypothesised the two samples would differ. Thirty-seven specimens (12 complete and 25 incomplete) were CT-scanned and landmarked. Originally complete specimens were used as reference to estimate the location of absent anatomical landmarks in incomplete specimens. As predicted, our results show shape differences between the two samples which are likely due to the compounded effect of contrasting population histories and diets.

1 Introduction

Human skeletal remains are used routinely to examine various cultural and palaeobiological aspects of past populations, including, e.g., funerary behaviour (Filipe, Godinho, Granja, Ribeiro, & Valera, 2013; Godinho, Gonçalves, & Valera, 2019), diet (Galland, Van Gerven, Von Cramon-Taubadel, & Pinhasi, 2016; Pokhojaev, Avni, Sella-Tunis, Sarig, & May, 2019; von Cramon-Taubadel, 2011), occupation (Henderson, 2013; Villotte et al., 2010; Villotte, Churchill, Dutour, & Henry-Gambier, 2010), mobility (Holt, 2003; Macintosh, Pinhasi, & Stock, 2014; Ruff et al., 2015), biological distances (Brewster, Meiklejohn, von Cramon-Taubadel, & Pinhasi, 2014; Nystrom & Malcom, 2010; Stojanowski & Schillaci, 2006), and palaeopathology (Calce, Kurki, Weston, & Gould, 2018; Godinho, Santos, & Valera, 2020; Griffin & Donlon, 2009). Yet, archaeological specimens are frequently fragmented, incomplete, and/or distorted, and so are often excluded from analyses (Godinho & O’Higgins, 2017; Gunz, Mitteroecker, Neubauer, Weber, & Bookstein, 2009; O’Higgins, Fitton, & Godinho, 2019). This leads to reduced sample sizes and hence, potentially biased results when examining past populations (Cardini & Elton, 2007; Cardini, Seetah, & Barker, 2015). To overcome such limitations, researchers frequently reconstruct incomplete specimens by estimating the original location of missing regions and include those specimens in the analyses to increase sample size. While reconstruction has frequently been based on individual expertise and morphological visual assessment, it is now commonly based on digital methods that allow more objective and reproducible approaches (Amano et al., 2015; Bauer & Harvati, 2015; Benazzi, Bookstein, Strait, & Weber, 2011; Godinho & O’Higgins, 2017). Such methods include 3D digitisation and Geometric Morphometrics (GM), which allow geometric- and statistical-technique-based digital reconstructions that are fully reproducible and so overcome the subjectivity of previous reconstruction methods (Gunz et al., 2009; O’Higgins et al., 2019). Moreover, GM also enables complex morphological analyses and examination of how form relates to other underlying variables (O’Higgins, 2000; Zelditch, Swiderski, Sheets, & Fink, 2012).

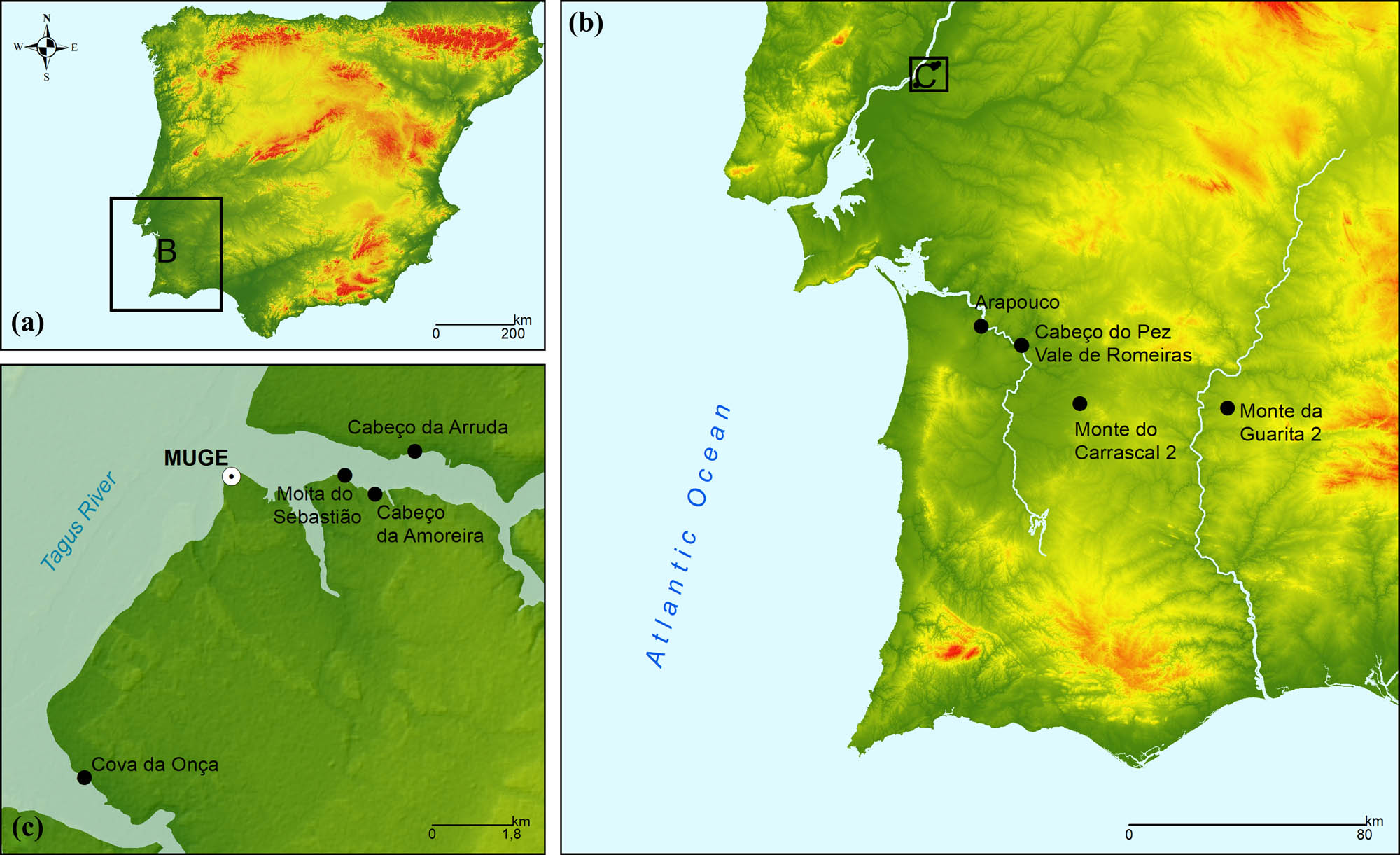

Here we use GM to reconstruct incomplete Mesolithic and Chalcolithic mandibles (from present Portugal) to increase sample size. The Mesolithic specimens originate from several Muge (Cabeço da Amoreira, Cabeço da Arruda, Cova da Onça, and Moita do Sebastião) and Sado (Arapouco, Cabeço de Pez, and Vale de Romeiras) shell middens and the Chalcolithic specimens from 2 distinct archaeological sites (Monte da Guarita 2 and Monte do Carrascal 2; Table 1 and Figure 1). The generally contemporaneous Muge shell middens are located in the Tagus valley and form one of the most important Mesolithic contexts worldwide (Bicho et al., 2013; Bicho, Umbelino, Detry, & Pereira, 2010; Gonçalves, 2009; Gonçalves, Cascalheira, & Bicho, 2014). They were formed by early Holocene hunter–gatherers and over 300 individuals were buried therein (Cunha & Cardoso, 2001; Jackes & Lubell, 1999; Peyroteo-Stjerna, 2020; Umbelino et al., 2015). The Sado complex also includes multiple middens and is located ∼100 km south of the Muge complex (Araújo, 2003; Cunha & Umbelino, 2001), and from which over 100 individuals (generally coeval with those from the Muge shell middens) were excavated (Cunha & Umbelino, 2001; Peyroteo-Stjerna, 2020; Umbelino, 2006). Monte da Guarita 2 is located in Alentejo and corresponds to a Chalcolithic collective underground tomb (hypogeum) from where several individuals were exhumed (Miguel & Simão, 2017). Monte do Carrascal 2 is an archaeological complex including several Chalcolithic collective hypogea from which several individuals were exhumed (Valera, Santos, Figueiredo, & Granja, 2014). After reconstruction of the samples, we further used GM to perform ensuing morphological analyses of the samples and examine if Mesolithic specimens are morphologically distinct from Chalcolithic mandibles. Because mandibular morphology is impacted by population history (Buck & Vidarsdottir, 2004; Katz, Grote, & Weaver, 2017; Mounier et al., 2018) and masticatory mechanics (Galland et al., 2016; von Cramon-Taubadel, 2011), and based on previous research (given below), we hypothesised that specimens from these two periods are morphologically distinct.

Inventory of complete and incomplete specimens (per site and chronology) used in this study

| Site | Chronology | Complete specimens | Incomplete specimens | Total specimens |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arapouco | Mesolithic | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Cabeço da Amoreira | Mesolithic | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Cabeço da Arruda | Mesolithic | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Cabeço de Pez | Mesolithic | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Cova da Onça | Mesolithic | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Moita do Sebastião | Mesolithic | 5 | 8 | 13 |

| Vale de Romeiras | Mesolithic | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Monte da Guarita 2 | Chalcolithic | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Monte do Carrascal 2 | Chalcolithic | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Total | 12 | 25 | 37 |

Location of the archaeological sites from which the specimens used in this study were recovered. (a) Overall location of sites within Iberia. (b) Cluster location of the Muge shell-middens and individual location of the remaining sites. (c) Individual location of each of the Muge sites.

Specifically, the Mesolithic hunter–gatherer mode of subsistence was replaced by Neolithic agro-pastoralism, which was introduced in Iberia in ∼5500 cal. BC by populations originating in the Middle East (Martins et al., 2015; Zilhão, 2000, 2001). This change in mode of subsistence is associated with marked genetic discontinuity between Iberian Mesolithic and Neolithic populations and substantial replacement of the former by the latter, despite some degree of population admixture (Haak et al., 2015; Olalde et al., 2015, 2019; Villalba-Mouco et al., 2019). Moreover, bone adapts to various aspects of mechanical loading (Currey, 2006; Judex & Rubin, 2010; Judex, Gross, & Zernicke, 1997; Judex, Lei, Han, & Rubin, 2007; Lanyon & Rubin, 1984; Lanyon, 1984; Mosley & Lanyon, 1998; Mosley, March, Lynch, & Lanyon, 1997; Turner, 1998) and so several previous studies have demonstrated that the dietary changes that occurred in the Mesolithic – Neolithic transition impacted mandibular morphology (Galland et al., 2016; Pokhojaev et al., 2019; von Cramon-Taubadel, 2011). Thus, we hypothesise that Mesolithic and Chalcolithic mandibular morphology of the samples used in this study differ because it is impacted by both population history and diet.

2 Materials and Methods

This study is based on a total of 37 Mesolithic and Chalcolithic specimens originating from several sites located in the present Portugal (Table 1 and Figure 1).

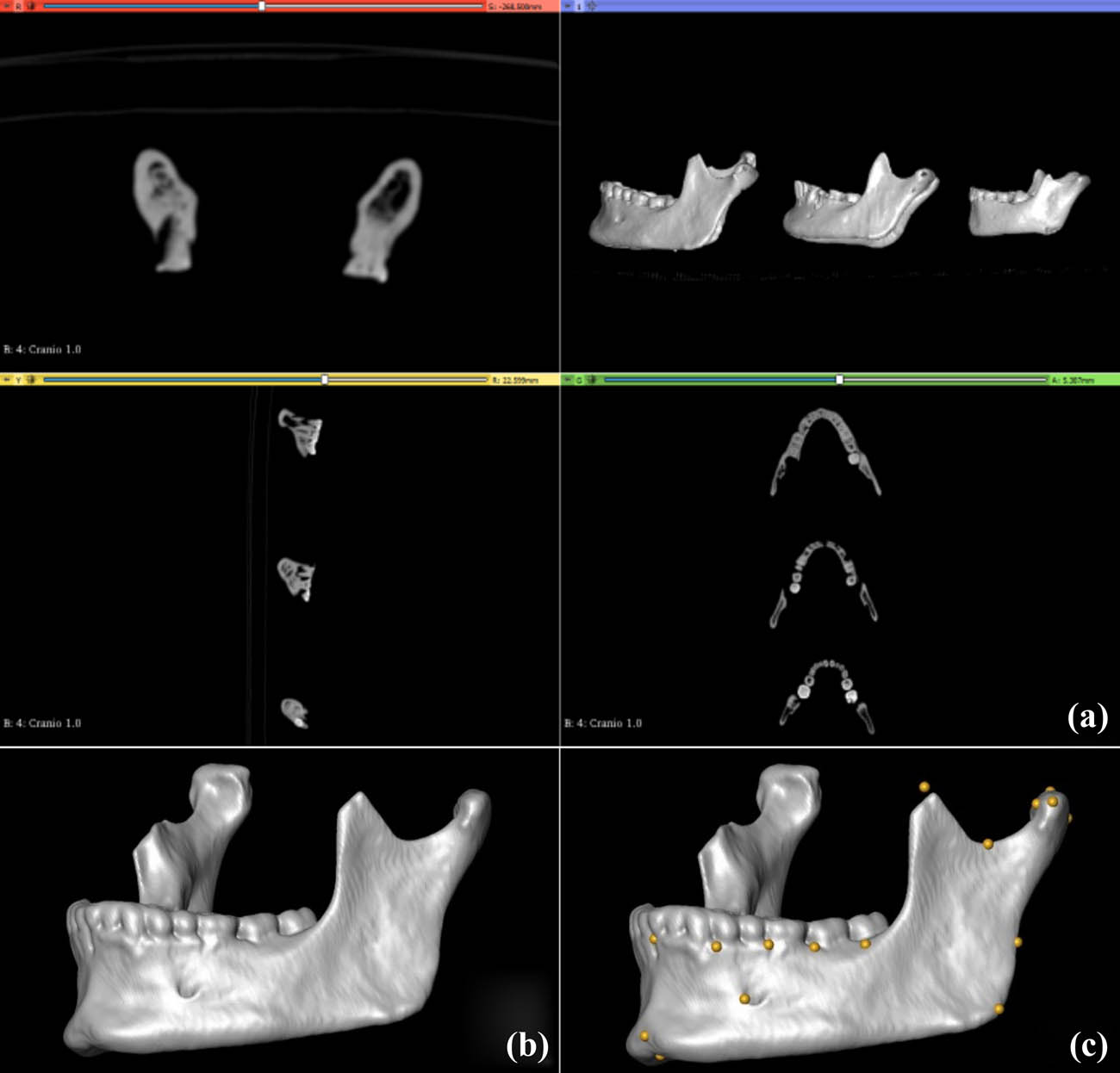

All specimens were digitised using a Toshiba Astelion CT scanner (120 kV, voxel size 0.348 × 0.348 × 0.3, revolution time 0.75 s, spiral pitch factor 0.94) at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine of the University of Lisbon. Segmentation ensued in 3D Slicer (Fedorov et al., 2012) using standard protocols described by Godinho and O’Higgins (2017, 2018), Godinho, Spikins, and O’Higgins (2018) and Godinho et al. (2018). Fragmented specimens were virtually pieced together (Godinho & Gonçalves, 2020). After this procedure, coordinates were extracted from a total of 21 anatomical landmarks (LMs; Table 2) from the most complete hemi-mandible of each specimen to capture mandibular morphology (Figure 2). The use of left hemi-mandibles was favoured. When specimens were incomplete, the location of the missing LMs was estimated using the thin plate spline (TPS) function of the Geomorph R package following the recommendations of Godinho, O’Higgins, and Gonçalves (2020). Specifically, excessively incomplete specimens were not reconstructed because reconstruction error may be larger than inter-individual differences and hence may lead to biased results. This led to the exclusion of specimens missing more than 5 LMs. Only 1 specimen with 5 missing LMs was included and incomplete specimens most often lacked 2 LMs (Table A1). Mesolithic specimens were used as reference to geometrically estimate the location of the missing landmarks in the incomplete Mesolithic specimens. The same procedure was applied to the Chalcolithic sample using complete Chalcolithic specimens. Thus, chronological specific references were used. This is because the use of inappropriate references (i.e., specimens with meaningful morphological differences due to, e.g., contrasting population history) leads to larger errors in the estimation of the location of missing anatomical regions (Gunz et al., 2009; Neeser, Ackermann, & Gain, 2009; Senck, Bookstein, Benazzi, Kastner, & Weber, 2015). Nevertheless, we tested if this population-specific reconstruction approach could be driving the hypothetical inter-population differences. To that end, a non-population specific reference was created using all complete specimens from both chronologies for ensuing reconstruction of incomplete specimens. Results from both reconstruction approaches were then compared using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Discriminant Function Analysis (DFA) (given below).

Mandibular landmarks used in this study

| # | Landmark name | Landmark description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gnathion | Midline of the inferior border of the mandible |

| 2 | Infradentale | Anterior alveolar ridge, between anterior incisors |

| 3 | Linguale | Genial tubercle: in case of a single tubercle, on its tip; in case of two, midpoint between them |

| 4 | Orale, mandible | Posterior alveolar ridge between the anterior incisors |

| 5 | Pogonion | Most anterior point of mandibular symphysis |

| 6 | C-P3 | Anterior alveolar ridge between canine and first premolar |

| 7 | P4-M1 | Anterior alveolar ridge between second premolar and first molar |

| 8 | M1-M2 | Anterior alveolar ridge between first and second molar teeth |

| 9 | Mental foramen anterior | Anterior point of mental foramen |

| 10 | Ramus root | Anterior rim of the ramus (placed on the level of the alveolar ridge) |

| 11 | Gonion | A point on the projection of the bisection of the mandibular angle |

| 12 | Condyle, lateral | From a superior view, the lateral point on the condyle |

| 13 | Condyle, midpoint | From a superior view, a point in the centre of the condyle |

| 14 | Condyle, medial | From a superior view, the medial point on the condyle |

| 15 | Sigmoid Notch | The lowest point of the mandibular notch, with the mandible in the mandibular plane and in lateral view |

| 16 | Coronoid process | Tip of the coronoid process |

| 17 | Mandibular foramen, inferior | Most inferior point of the mandibular foramen |

| 18 | Alveolous, lingual posterior | From a superior view, the most posterior point on the lingual alveolar process |

| 19 | Condyle, anterior | A point on the antero-superior aspect of the mandibular notch (on the condyle) |

| 20 | Condyle, posterior | The centre of the condyle from a posterior view |

| 21 | Ramus, posterior | Posteriormost point of the ramus that is in line with the ramus root |

Visualisation of CT scan slices (a), ensued by rendering (b), and landmarking of individual specimens (c). Note that C shows the location of present and estimated missing (e.g., in the coronoid process) landmarks.

After estimation of the missing LMs, standard GM analysis ensued. The landmark coordinate datasets of all specimens were superimposed using Generalised Procrustes Analysis (GPA). GPA removes the effects of size, location, and orientation and produces shape variables that are used in shape analysis. Shape differences between samples were examined via the PCA and visualised using Thin Plate Splines (TPS) that depict shape differences along the selected PCs. The impact of reconstruction approach was examined by performing a PCA in which all specimens from the population-specific and non-population-specific reconstructions were included. DFA with 10,000 permutations and cross-validation scores was also used to examine the inter-population differences and was implemented using MorphoJ (Klingenberg, 2011). DFA was also used to examine the impact of population-specific vs non-population-specific reconstruction approaches (given above).

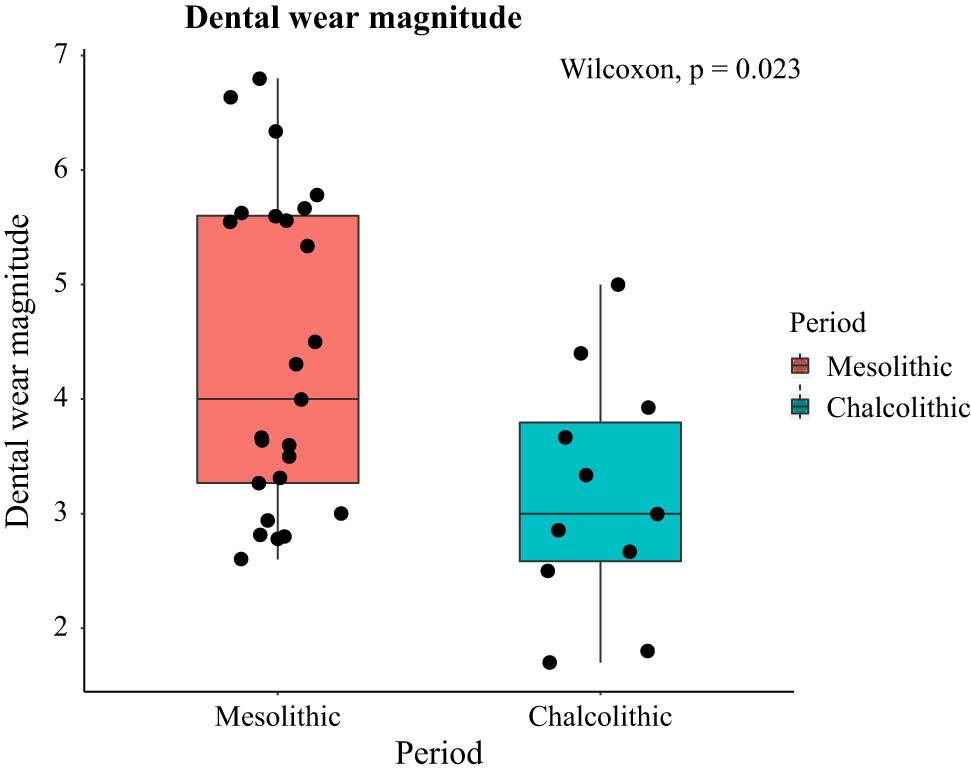

To examine if hypothetical morphological differences between Mesolithic and Chalcolithic samples are most likely related to population history or masticatory mechanics (given above), dental wear was also examined because it is related to the latter (Chattah & Smith, 2006; Smith, 1984). Wear magnitude was scored according to Smith (1984), averaged per individual and compared between the two samples using a boxplot and the Wilcoxon non-parametric statistical test.

3 Results

Digitisation and the use of GM-based reconstruction allowed estimating the original morphology of 25 originally incomplete specimens, thereby, increasing the sample size from 12 to 37 specimens.

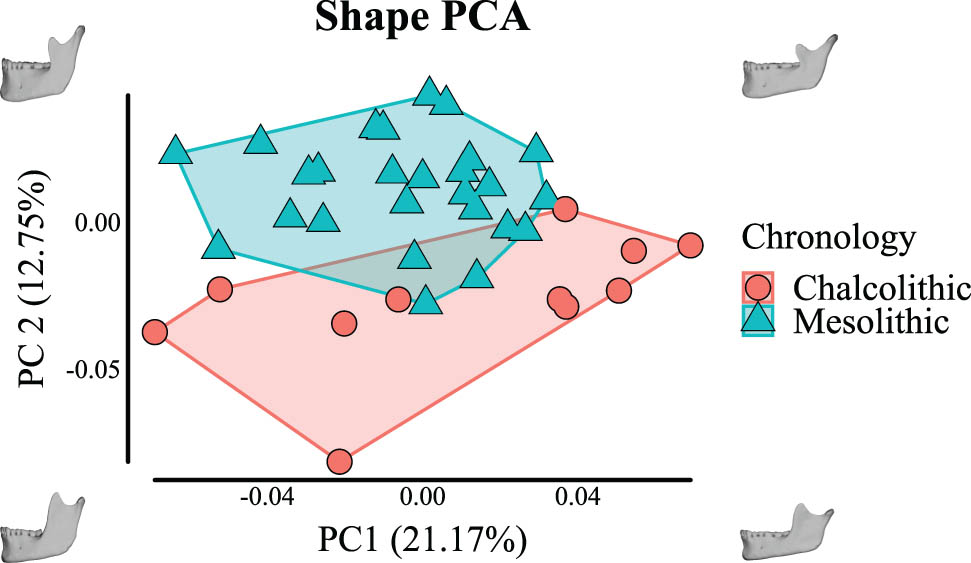

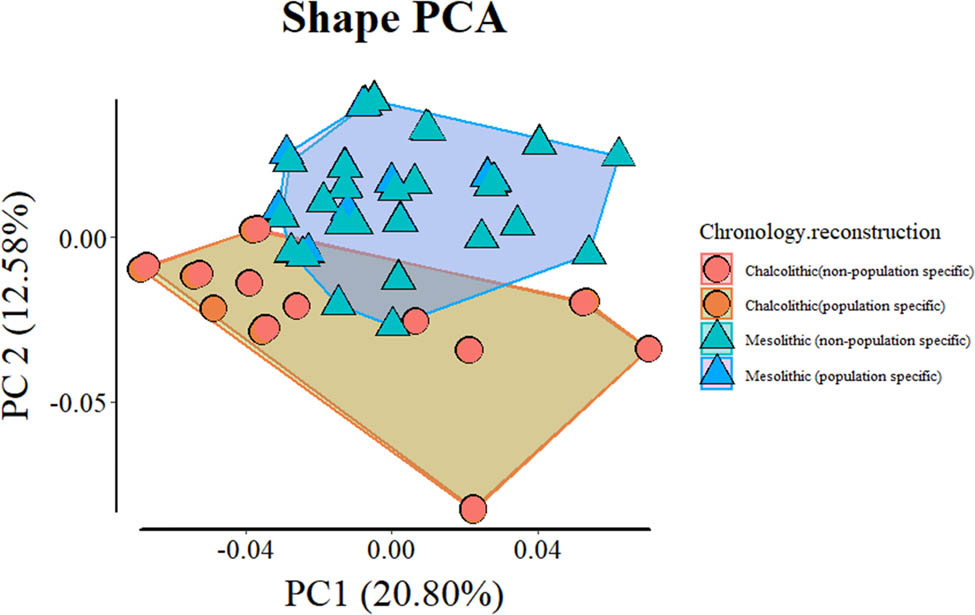

Ensuing morphological analysis including all specimens shows limited overlap between the two samples (when plotting PC1 and 2, which explain ∼34% of the total variance; Figure 3). This is because the Mesolithic sample clusters mostly along the positive values of PC2 and the Chalcolithic sample mostly clusters along the negative values. Morphologically, this corresponds to Chalcolithic specimens having, e.g., generally wider rami, taller coronoid processes, shorter mandibular symphyses, and more alveolar prognathism. Although there is overlap between the two samples in PC1, the most extreme positive specimens are Chalcolithic. Such specimens have, e.g., shorter mandibular symphyses, more flexure of the posterior border of the ramus and more anteriorly positioned coronoid processes. PCA comparison of full samples including population- and non-population-specific reconstruction approaches show meaningful overlap between specimens and very little impact on the overlap between groups (Figure A1). DFA is unable to reliably discriminate between population- and non-population-specific reconstructions of the same populations, and discriminates similarly between Mesolithic and Chalcolithic specimens based on the two different reconstruction approaches (Tables A2–A7). This shows inter-population differences are not due to reconstruction approach.

PCA of shape variation of Mesolithic hunter–gatherer and Chalcolithic agro-pastoralist mandibles.

DFA using 10,000 permutations shows significant inter-group differences (T-Square: p < 0.0001). Nevertheless, cross-validation results show misclassification of 4/11 Chalcolithic and 2/26 Mesolithic specimens (Table 3).

Cross-validation scores of DFA (with 10,000 permutations)

| Allocated to | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| True group | Chalcolithic | Mesolithic | Total |

| Chalcolithic | 7 | 4 | 11 |

| Mesolithic | 2 | 24 | 26 |

Dental wear magnitude is significantly heavier in the Mesolithic sample (Figure 4).

Dental wear magnitude (scored according to Smith, 1984) of the Mesolithic and Chalcolithic samples.

4 Discussion

The use of digital methods enabled the objective and reproducible reconstruction of 25 specimens that were originally incomplete. Thus, sample size was increased to a total of 37 specimens, which enabled further GM-based morphological analysis, a better representation of morphological variance, and hence more reliable results than if only the 12 originally complete specimens were included.

As expected, morphological analyses show shape differences between the Mesolithic and Chalcolithic samples. Our results also show negligible differences between population-specific and non-population-specific reconstructions. Thus, contrasting shapes between the two populations are not related to the reconstruction approach. Because mandibular morphology is known to relate to both population history (Buck & Vidarsdottir, 2004; Katz et al., 2017; Mounier et al., 2018) and masticatory mechanics (Galland et al., 2016; Katz et al., 2017; May, Sella-Tunis, Pokhojaev, Peled, & Sarig, 2018; Pokhojaev et al., 2019; von Cramon-Taubadel, 2011), these shape differences may relate to either of these two underlying factors.

Specifically, Iberian Mesolithic populations derived from previously existing Post-Glacial Upper Palaeolithic populations (Brewster et al., 2014; López-Onaindia, Gibaja, & Subirà, 2019). By no later than ∼5500 cal. BC, populations originating in the Middle East reached the Iberian Peninsula and introduced agriculture (Martins et al., 2015; Zilhão, 2000, 2001). Ancient DNA studies show marked genetic discontinuity between Mesolithic hunter–gatherers and Neolithic agro-pastoralists, thus suggesting population replacement mainly in most European regions. However, such studies also show the presence of Mesolithic DNA in post-Mesolithic individuals and so at least some level of admixture exists between the local Mesolithic and the incoming Neolithic populations (Haak et al., 2015; Olalde et al., 2015, 2019; Villalba-Mouco et al., 2019). Because mandibular morphology is known to relate to population history (Buck & Vidarsdottir, 2004; Katz et al., 2017; Mounier et al., 2018), our results showing shape differences between the two samples are to be expected and likely also related to population history.

Despite contrasts in mandibular shape being likely related to differences in population history in the samples, masticatory mechanics has also probably impacted mandibular morphology to some extent. The Mesolithic hunter–gatherer diet has been consistently said to be mechanically more demanding than the post-Mesolithic agro-pastoralist diet (Cohen, 1989; Larsen, 1997, 2006; Stock & Pinhasi, 2011). This is because the latter included more processed food items that made the overall diet softer and so less demanding (Cohen, 1989; Larsen, 1997, 2006; Stock & Pinhasi, 2011). Previous experimental studies using non-human mammal models have shown that differences in the material properties of diet impact skull morphology (Beecher & Corruccini, 1981; Bouvier & Hylander, 1984; He & Kiliaridis, 2003; Kiliaridis, Engström, & Thilander, 1985; Menegaz & Ravosa, 2017; Menegaz, Sublett, Figueroa, Hoffman, & Ravosa, 2009; Ravosa, Kunwar, Stock, & Stack, 2007; Ravosa et al., 2008a,b), and so differences in skull form between hunter–gatherers and agro-pastoralists are frequently linked to differences in the masticatory demands due to dietary differences (Galland et al., 2016; Katz et al., 2017; May et al., 2018; Pokhojaev et al., 2019; von Cramon-Taubadel, 2011). Our results showing significantly heavier wear in Mesolithic specimens are consistent with previous studies (Larsen, 1997; Lukacs, 1989) and support the hypothesis that mandibular shape differences between the two samples are also related to differences in diet and therefore in masticatory demands. This is because dental wear is known to relate to the material properties of food, and so it is frequently used to examine differences in diet and food pre-processing (Chattah & Smith, 2006; Smith, 1984).

In summary, our results confirm our prediction that mandibular morphology differs between Mesolithic hunter–gatherers and Chalcolithic agro-pastoralists. This is probably due to the compounded effect of population history and masticatory mechanics. Although we are unable to discern which of these factors impacted morphology the most, previous research about limb skeletal morphology showed that differences in mechanical loading fail to erase the impact of population history in bone form (Agostini, Holt Brigitte, & Relethford John, 2018). This is consistent with previous studies showing that mandibular morphology is impacted more by population history than by masticatory mechanics (Katz et al., 2017), and so the mandibular morphological differences detected in this study are most likely related to population history and, possibly, enhanced by contrasting masticatory demands.

Abbreviations

- DFA

-

discriminant function analysis

- GPA

-

generalised procrustes analysis

- GM

-

geometric morphometric

- LM

-

landmarks

- PCA

-

principal component analysis

- TPS

-

thin plate spline

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Dr Miguel Ramalho† and Dr José António Moita for granting access to the skeletal remains of Muge; António Valera and Era Arqueologia S.A. for providing access to the skeletal remains from Monte da Guarita 2; Sara Ramos for access to the skeletal remains from Monte do Carrascal 2; Prof. Sandra Jesus and Dr Óscar Gamboa for CT scanning at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine of the University of Lisbon.

-

Funding information: RM Godinho was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT; contract reference 2020.00499.CEECIND) and the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER) via the Programa Operacional CRESC Algarve 2020, of Portugal2020 (project ALG-01-0145-FEDER-29680), in the context of the MugePortal project (“Muge Shellmiddens Project: a new portal for the last hunter–gatherers of the Tagus Valley, Portugal (MugePortal);” project reference ALG-01-0145-FEDER-29680/PTDC/HAR-ARQ/29680/2017, funded by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT)). C. Umbelino was funded by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT, reference UIDB/00283/2020). C Gonçalves was funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT; contract reference DL 57/2016/CP1361/CT0029). This research was also funded by the Archaeological Institute of America (The Archaeology of Portugal Fellowship).

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Appendix

Number of missing landmarks per specimen in the Mesolithic and Chalcolithic samples

| Number of missing landmarks | Mesolithic | Chalcolithic | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10 | 2 | 12 | 32.43 |

| 1 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 13.51 |

| 2 | 6 | 3 | 9 | 24.32 |

| 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 13.51 |

| 4 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 13.51 |

| 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2.70 |

| Total | 26 | 11 | 37 | 100.00 |

DFA with cross-validation of the non-population-specific reconstructed Chalcolithic sample vs the population-specific reconstructed Chalcolithic sample (see details about reconstruction parameters in Materials and Methods)

| Allocated to | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| True group | Chalcolithic (non-population specific) | Chalcolithic (population specific) | Total |

| From discriminant function | |||

| Chalcolithic (non-population specific) | 11 | 0 | 11 |

| Chalcolithic (population specific) | 2 | 9 | 11 |

| From cross-validation | |||

| Chalcolithic (non-population specific) | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| Chalcolithic (population specific) | 6 | 5 | 11 |

DFA with cross-validation of the non-population-specific reconstructed Chalcolithic sample vs the non-population-specific reconstructed Mesolithic sample (see details about reconstruction parameters in Materials and Methods)

| Allocated to | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| True group | Chalcolithic (non-population specific) | Mesolithic (non-population specific) | Total |

| From discriminant function | |||

| Chalcolithic (non-population specific) | 11 | 0 | 11 |

| Mesolithic (non-population specific) | 0 | 26 | 26 |

| From cross-validation | |||

| Chalcolithic (non-population specific) | 8 | 3 | 11 |

| Mesolithic (non-population specific) | 2 | 24 | 26 |

DFA with cross-validation of the non-population-specific reconstructed Chalcolithic sample vs the population-specific reconstructed Mesolithic sample (see details about reconstruction parameters in Materials and Methods)

| Allocated to | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| True group | Chalcolithic (non-population specific) | Mesolithic (population specific) | Total |

| From discriminant function | |||

| Chalcolithic (non-population specific) | 11 | 0 | 11 |

| Mesolithic (population-specific) | 0 | 26 | 26 |

| From cross-validation | |||

| Chalcolithic (non-population specific) | 8 | 3 | 11 |

| Mesolithic (population-specific) | 1 | 25 | 26 |

DFA with cross-validation of the population-specific reconstructed Chalcolithic sample vs the non-population-specific reconstructed Mesolithic sample (see details about reconstruction parameters in Materials and Methods)

| Allocated to | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| True group | Chalcolithic (population specific) | Mesolithic (non-population specific) | Total |

| From discriminant function | |||

| Chalcolithic (population specific) | 11 | 0 | 11 |

| Mesolithic (non-population specific) | 0 | 26 | 26 |

| From cross-validation | |||

| Chalcolithic (population specific) | 7 | 4 | 11 |

| Mesolithic (non-population specific) | 1 | 25 | 26 |

DFA with cross-validation of the population-specific reconstructed Chalcolithic sample vs the population-specific reconstructed Mesolithic sample (see details about reconstruction parameters in Materials and methods)

| Allocated to | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| True group | Chalcolithic (population specific) | Mesolithic (population specific) | Total |

| From discriminant function | |||

| Chalcolithic (population specific) | 11 | 0 | 11 |

| Mesolithic (population specific) | 0 | 26 | 26 |

| From cross-validation | |||

| Chalcolithic (population specific) | 7 | 4 | 11 |

| Mesolithic (population specific) | 2 | 24 | 26 |

DFA with cross-validation of the non-population-specific reconstructed Mesolithic sample vs the population-specific reconstructed Mesolithic sample (see details about reconstruction parameters in Materials and Methods)

| Allocated to | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| True group | Mesolithic (non-population specific) | Mesolithic (population specific) | Total |

| From discriminant function | |||

| Mesolithic (non-population specific) | 22 | 4 | 26 |

| Mesolithic (population specific) | 6 | 20 | 26 |

| From cross-validation | |||

| Mesolithic (non-population specific) | 7 | 19 | 26 |

| Mesolithic (population specific) | 17 | 9 | 26 |

Shape PCA comparing population-specific and non-population-specific reconstruction of incomplete specimens. Note there is complete or almost complete overlap between specimens despite differences in reconstruction method.

References

Agostini, G., Holt Brigitte, M., & Relethford John, H. (2018). Bone functional adaptation does not erase neutral evolutionary information. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 166(3), 708–729. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.23460.Search in Google Scholar

Amano, H., Kikuchi, T., Morita, Y., Kondo, O., Suzuki, H., Ponce de León, M. S., & Ogihara, N. (2015). Virtual reconstruction of the Neanderthal Amud 1 cranium. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 158(2), 185–197. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.22777.Search in Google Scholar

Araújo, A. C. (2003). Long term change in Portuguese early Holocene settlement and subsistence. In L. Larsson, H. Kindgren, K. Knutsson, D. Leoffler, & A. Åkerlund (Eds.), Mesolithic on the move (pp. 569–580). Stockholm: Oxbow Books.Search in Google Scholar

Bauer, C. C., & Harvati, K. (2015). A virtual reconstruction and comparative analysis of the KNM-ER 42700 cranium. Anthropologischer Anzeiger, 72(2), 129–140.10.1127/anthranz/2015/0387Search in Google Scholar

Beecher, R. M., & Corruccini, R. S. (1981). Effects of dietary consistency on craniofacial and occlusal development in the rat. The Angle Orthodontist, 51(1), 61–69. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1981)051 < 0061:EODCOC > 2.0.CO;2.Search in Google Scholar

Benazzi, S., Bookstein, F. L., Strait, D. S., & Weber, G. W. (2011). A new OH5 reconstruction with an assessment of its uncertainty. Journal of Human Evolution, 61(1), 75–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.02.005.Search in Google Scholar

Bicho, N., Cascalheira, J., Marreiros, J., Gonçalves, C., Pereira, T., & Dias, R. (2013). Chronology of the Mesolithic occupation of the Muge valley, central Portugal: The case of Cabeço da Amoreira. Quaternary International, 308–309, 130–139. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2012.10.049.Search in Google Scholar

Bicho, N., Umbelino, C., Detry, C., & Pereira, T. (2010). The emergence of muge Mesolithic shell Middens in Central Portugal and the 8200 cal yr BP Cold Event. The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology, 5(1), 86–104. doi: 10.1080/15564891003638184.Search in Google Scholar

Bouvier, M., & Hylander, W. L. (1984). The effect of dietary consistency on gross and histologic morphology in the craniofacial Region of Young-Rats. American Journal of Anatomy, 170(1), 117–126. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001700109.Search in Google Scholar

Brewster, C., Meiklejohn, C., von Cramon-Taubadel, N., & Pinhasi, R. (2014). Craniometric analysis of European Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic samples supports discontinuity at the Last Glacial Maximum. Nature Communications, 5, 4094. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5094.Search in Google Scholar

Buck, T. J., & Vidarsdottir, U. S. (2004). A proposed method for the identification of race in sub-adult skeletons: A geometric morphometric analysis of mandibular morphology. Journal of Forensic Science, 49(6), JFS2004074–2004076.10.1520/JFS2004074Search in Google Scholar

Calce, S. E., Kurki, H. K., Weston, D. A., & Gould, L. (2018). The relationship of age, activity, and body size on osteoarthritis in weight-bearing skeletal regions. International Journal of Paleopathology, 22, 45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpp.2018.04.001.Search in Google Scholar

Cardini, A., & Elton, S. (2007). Sample size and sampling error in geometric morphometric studies of size and shape. Zoomorphology, 126(2), 121–134. doi: 10.1007/s00435-007-0036-2.Search in Google Scholar

Cardini, A., Seetah, K., & Barker, G. (2015). How many specimens do I need? Sampling error in geometric morphometrics: Testing the sensitivity of means and variances in simple randomized selection experiments. Zoomorphology, 134(2), 149–163. doi: 10.1007/s00435-015-0253-z.Search in Google Scholar

Chattah, N. L.-T., & Smith, P. (2006). Variation in occlusal dental wear of two Chalcolithic populations in the southern Levant. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 130(4), 471–479. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20388.Search in Google Scholar

Cohen, M. N. (1989). Health and the rise of civilization. New Haven: Yale University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Cunha, E., & Cardoso, F. (2001). The osteological series from Cabeço Da Amoreira (Muge, Portugal). Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris, 13(3–4), 323–333.10.4000/bmsap.6231Search in Google Scholar

Cunha, E., & Umbelino, C. (2001). Mesolithic people from Portugal: An approach to Sado osteological series. Anthropologie, 39(2/3), 125–132.Search in Google Scholar

Currey, J. D. (2006). Bones, structure and mechanics. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Fedorov, A., Beichel, R., Kalpathy-Cramer, J., Finet, J., Fillion-Robin, J.-C., Pujol, S., … Kikinis, R. (2012). 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 30(9), 1323–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2012.05.001.Search in Google Scholar

Filipe, V., Godinho, R. M., Granja, R., Ribeiro, A., & Valera, A. (2013). Bronze age funerary spaces in Outeiro Alto 2 (Brinches, Serpa, Portugal): The hypogea cemetery. Zephyrus, 71, 107–129.Search in Google Scholar

Galland, M., Van Gerven, D. P., Von Cramon-Taubadel, N., & Pinhasi, R. (2016). 11,000 years of craniofacial and mandibular variation in Lower Nubia. Scientific Reports, 6, 31040. doi: 10.1038/srep31040. http://www.nature.com/articles/srep31040#supplementary-information.Search in Google Scholar

Godinho, R. M., Fitton, L. C., Toro-Ibacache, V., Stringer, C. B., Lacruz, R. S., Bromage, T. G., & O’Higgins, P. (2018). The biting performance of Homo sapiens and Homo heidelbergensis. Journal of Human Evolution, 118, 56–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2018.02.010.Search in Google Scholar

Godinho, R. M., & Gonçalves, C. (2020). Antropologia Virtual: Novas metodologias para a análise morfológica e funcional. In J. M. Arnaud, C. Neves, & A. Martins (Eds.), Actas do III Congresso da Associação dos Arqueólogos Portugueses (pp. 311–323). Lisboa: Associação dos Arqueólogos Portugueses e CITCEM.10.21747/978-989-8970-25-1/arqa23Search in Google Scholar

Godinho, R. M., Gonçalves, D., & Valera, A. C. (2019). The preburning condition of Chalcolithic cremated human remains from the Perdigões enclosures (Portugal). International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 29(5), 706–717. doi: 10.1002/oa.2768.Search in Google Scholar

Godinho, R. M., & O’Higgins, P. (2017). Virtual reconstruction of cranial remains: The H. heidelbergensis, Kabwe 1 fossil. In D. Errickson & T. Thompson (Eds.), Human remains – Another dimension: The application of 3D imaging in funerary context (pp. 135–147). London: Elsevier.10.1016/B978-0-12-804602-9.00011-4Search in Google Scholar

Godinho, R. M., & O’Higgins, P. (2018). The biomechanical significance of the frontal sinus in Kabwe 1 (Homo heidelb10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.10.007Search in Google Scholar

Godinho, R. M., O’Higgins, P., & Gonçalves, C. (2020). Assessing the reliability of virtual reconstruction of mandibles. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 172(4), 723–734. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.24095.Search in Google Scholar

Godinho, R. M., Santos, A. L., & Valera, A. C. (2020). A lunate-triquetral coalition from a commingled funerary context from the Chalcolithic Perdigões ditched enclosures of Portugal. Anthropologischer Anzeiger, 77(1), 83–88. doi: 10.1127/anthranz/2019/0935.Search in Google Scholar

Godinho, R. M., Spikins, P., & O’Higgins, P. (2018). Supraorbital morphology and social dynamics in human evolution. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2(6), 956–961. doi: 10.1038/s41559-018-0528-0.Search in Google Scholar

Gonçalves, C. (2009). Modelos preditivos em SIG na localização de sítios arqueológicos de cronologia mesolítica no Vale do Tejo. (Master thesis). Faro: Universidade Do Algarve.Search in Google Scholar

Gonçalves, C., Cascalheira, J., & Bicho, N. (2014). Shellmiddens as landmarks: Visibility studies on the Mesolithic of the Muge valley (Central Portugal). Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 36, 130–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2014.09.011.Search in Google Scholar

Griffin, R. C., & Donlon, D. (2009). Patterns in dental enamel hypoplasia by sex and age at death in two archaeological populations. Archives of Oral Biology, 54, S93–S100. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2008.09.012.Search in Google Scholar

Gunz, P., Mitteroecker, P., Neubauer, S., Weber, G. W., & Bookstein, F. L. (2009). Principles for the virtual reconstruction of hominin crania. Journal of Human Evolution, 57(1), 48–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2009.04.004.Search in Google Scholar

Haak, W., Lazaridis, I., Patterson, N., Rohland, N., Mallick, S., Llamas, B., … Reich, D. (2015). Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe. Nature, 522(7555), 207–211. doi: 10.1038/nature14317.Search in Google Scholar

He, T. L., & Kiliaridis, S. (2003). Effects of masticatory muscle function on craniofacial morphology in growing ferrets (Mustela putorius furo). European Journal of Oral Sciences, 111(6), 510–517. doi: 10.1111/j.0909-8836.2003.00080.x.Search in Google Scholar

Henderson, C. (2013). Subsistence strategy changes: The evidence of entheseal changes. HOMO, 64(6), 491–508. doi: 10.1016/j.jchb.2013.08.002.Search in Google Scholar

Holt, B. M. (2003). Mobility in Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic Europe: Evidence from the lower limb. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 122(3), 200–215. doi: 10.1002/Ajpa.10256.Search in Google Scholar

Jackes, M., & Lubell, D. (1999). Human biological variability in the Portuguese Mesolithic. Arqueologia, 24, 25–42.Search in Google Scholar

Judex, S., Gross, T. S., & Zernicke, R. F. (1997). Strain gradients correlate with sites of exercise-induced bone-forming surfaces in the adult skeleton. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 12(10), 1737–1745. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.10.1737.Search in Google Scholar

Judex, S., Lei, X., Han, D., & Rubin, C. (2007). Low-magnitude mechanical signals that stimulate bone formation in the ovariectomized rat are dependent on the applied frequency but not on the strain magnitude. Journal of Biomechanics, 40(6), 1333–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.05.014.Search in Google Scholar

Judex, S., & Rubin, C. T. (2010). Is bone formation induced by high-frequency mechanical signals modulated by muscle activity? Journal of Musculoskeletal & Neuronal Interactions, 10(1), 3–11.Search in Google Scholar

Katz, D. C., Grote, M. N., & Weaver, T. D. (2017). Changes in human skull morphology across the agricultural transition are consistent with softer diets in preindustrial farming groups. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1702586114.Search in Google Scholar

Kiliaridis, S., Engström, C., & Thilander, B. (1985). The relationship between masticatory function and craniofacial morphologyI. A cephalometric longitudinal analysis in the growing rat fed a soft diet. European Journal of Orthodontics, 7(4), 273–283.10.1093/ejo/7.4.273Search in Google Scholar

Klingenberg, C. P. (2011). MorphoJ: An integrated software package for geometric morphometrics. Molecular Ecology Resources, 11(2), 353–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02924.x.Search in Google Scholar

Lanyon, L. E. (1984). Functional strain as a determinant for bone remodeling. Calcified Tissue International, 36(1), S56–S61. doi: 10.1007/bf02406134.Search in Google Scholar

Lanyon, L. E., & Rubin, C. T. (1984). Static vs Dynamic Loads as an Influence on Bone Remodeling. Journal of Biomechanics, 17(12), 897–905. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(84)90003-4.Search in Google Scholar

Larsen, C. S. (1997). Bioarchaeology: Interpreting behavior from the human skeleton. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511802676Search in Google Scholar

Larsen, C. S. (2006). The agricultural revolution as environmental catastrophe: Implications for health and lifestyle in the Holocene. Quaternary International, 150(1), 12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2006.01.004.Search in Google Scholar

López-Onaindia, D., Gibaja, J. F., & Subirà, M. E. (2019). Heirs of the Glacial Maximum: Dental morphology suggests Mesolithic human groups along the Iberian Peninsula shared the same biological origins. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 11(10), 5499–5512. doi: 10.1007/s12520-019-00877-6.Search in Google Scholar

Lukacs, J. R. (1989). Dental paleopathology: Methods for reconstructing health status and dietary patterns in prehistory. In M. Y. İşcan & K. A. R. Kennedy (Eds.), Reconstructing Life from the Skeleton (pp. 261–286). New York: Alan R. Liss.Search in Google Scholar

Macintosh, A. A., Pinhasi, R., & Stock, J. T. (2014). Lower limb skeletal biomechanics track long-term decline in mobility across ∼6150 years of agriculture in Central Europe. Journal of Archaeological Science, 52, 376–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2014.09.001.Search in Google Scholar

Martins, H., Oms, F. X., Pereira, L., Pike, A. W., Rowsell, K., & Zilhão, J. (2015). Radiocarbon dating the beginning of the Neolithic in Iberia: New results, new problems. Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology, 28(1), 105–131.10.1558/jmea.v28i1.27503Search in Google Scholar

May, H., Sella-Tunis, T., Pokhojaev, A., Peled, N., & Sarig, R. (2018). Changes in mandible characteristics during the terminal Pleistocene to Holocene Levant and their association with dietary habits. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 22, 413–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2018.03.020.Search in Google Scholar

Menegaz, R. A., & Ravosa, M. J. (2017). Ontogenetic and functional modularity in the rodent mandible. Zoology, 124, 61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.zool.2017.05.009.Search in Google Scholar

Menegaz, R. A., Sublett, S. V., Figueroa, S. D., Hoffman, T. J., & Ravosa, M. J. (2009). Phenotypic Plasticity and Function of the Hard Palate in Growing Rabbits. The Anatomical Record: Advances in Integrative Anatomy and Evolutionary Biology, 292(2), 277–284. doi: 10.1002/ar.20840.Search in Google Scholar

Miguel, L., & Simão, P. (2017). Minimização de Impactes sobre o Património Cultural decorrentes da execução dos Blocos de Rega de Pias (Fase de Obra) – Relatório dos Trabalhos Arqueológicos Monte da Guarita 2(2017). Retrieved from Lisboa. https://biblioteca.edia.pt/BiblioNET/Upload/PDFS/M03608.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Mosley, J. R., & Lanyon, L. E. (1998). Strain rate as a controlling influence on adaptive modeling in response to dynamic loading of the ulna in growing male rats. Bone, 23(4), 313–318. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(98)00113-6.Search in Google Scholar

Mosley, J. R., March, B. M., Lynch, J., & Lanyon, L. E. (1997). Strain magnitude related changes in whole bone architecture in growing rats. Bone, 20(3), 191–198. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(96)00385-7.Search in Google Scholar

Mounier, A., Correia, M., Rivera, F., Crivellaro, F., Power, R., Jeffery, J., & Mirazón Lahr, M. (2018). Who were the Nataruk people? Mandibular morphology among late Pleistocene and early Holocene fisher-forager populations of West Turkana (Kenya). Journal of Human Evolution, 121, 235–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2018.04.013.Search in Google Scholar

Neeser, R., Ackermann, R. R., & Gain, J. (2009). Comparing the accuracy and precision of three techniques used for estimating missing landmarks when reconstructing fossil hominin crania. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 140(1), 1–18. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21023.Search in Google Scholar

Nystrom, K. C., & Malcom, C. M. (2010). Sex-specific phenotypic variability and social organization in the Chiribaya of Southern Peru. Latin American Antiquity, 21(4), 375–397. doi: 10.7183/1045-6635.21.4.375.Search in Google Scholar

O’Higgins, P. (2000). The study of morphological variation in the hominid fossil record: Biology, landmarks and geometry. Journal of Anatomy, 197, 103–120. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2000.19710103.x.Search in Google Scholar

O’Higgins, P., Fitton, L. C., & Godinho, R. M. (2019). Geometric morphometrics and finite elements analysis: Assessing the functional implications of differences in craniofacial form in the hominin fossil record. Journal of Archaeological Science, 101, 159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2017.09.011.Search in Google Scholar

Olalde, I., Mallick, S., Patterson, N., Rohland, N., Villalba-Mouco, V., Silva, M., & Reich, D. (2019). The genomic history of the Iberian Peninsula over the past 8000 years. Science (New York, N.Y.), 363(6432), 1230. doi: 10.1126/science.aav4040.Search in Google Scholar

Olalde, I., Schroeder, H., Sandoval-Velasco, M., Vinner, L., Lobón, I., Ramirez, O., … Lalueza-Fox, C. (2015). A Common genetic origin for early farmers from mediterranean cardial and central European LBK Cultures. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 32(12), 3132–3142. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv181.Search in Google Scholar

Peyroteo-Stjerna, R. (2020). Chronology of the burial activity of the last hunter-gatherers in the Southwestern Iberian Peninsula, Portugal. Radiocarbon, 63, 1–35. doi: 10.1017/RDC.2020.100.Search in Google Scholar

Pokhojaev, A., Avni, H., Sella-Tunis, T., Sarig, R., & May, H. (2019). Changes in human mandibular shape during the Terminal Pleistocene-Holocene Levant. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 8799. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45279-9.Search in Google Scholar

Ravosa, M. J., Kunwar, R., Stock, S. R., & Stack, M. S. (2007). Pushing the limit: Masticatory stress and adaptive plasticity in mammalian craniomandibular joints. Journal of Experimental Biology, 210(4), 628–641. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02683.Search in Google Scholar

Ravosa, M. J., Lopez, E. K., Menegaz, R. A., Stock, S. R., Stack, M. S., & Hamrick, M. W. (2008a). Adaptive plasticity in the mammalian masticatory complex: You are what, and how, you eat. In C. Vinyard, M. J. Ravosa, & C. Wall (Eds.), Primate craniofacial function and biology (pp. 293–328). Boston: Springer US.10.1007/978-0-387-76585-3_14Search in Google Scholar

Ravosa, M. J., López, E. K., Menegaz, R. A., Stock, S. R., Stack, M. S., & Hamrick, M. W. (2008b). Using “Mighty Mouse” to understand masticatory plasticity: Myostatin-deficient mice and musculoskeletal function. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 48(3), 345–359. doi: 10.1093/icb/icn050.Search in Google Scholar

Ruff, C. B., Holt, B., Niskanen, M., Sladek, V., Berner, M., Garofalo, E., … Whittey, E. (2015). Gradual decline in mobility with the adoption of food production in Europe. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(23), 7147.10.1073/pnas.1502932112Search in Google Scholar

Senck, S., Bookstein, F. L., Benazzi, S., Kastner, J., & Weber, G. W. (2015). Virtual reconstruction of modern and fossil Hominoid Crania: Consequences of reference sample choice. The Anatomical Record, 298(5), 827–841. doi: 10.1002/ar.23104.Search in Google Scholar

Smith, B. H. (1984). Patterns of molar wear in hunter–gatherers and agriculturalists. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 63(1), 39–56. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330630107.Search in Google Scholar

Stock, J. T., & Pinhasi, R. (2011). Introduction: Changing paradigms in our understanding of the transition to agriculture: Human bioarchaeology, behaviour and adaptaion. In Human bioarchaeology of the transition to agriculture (pp. 1–13). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi: 10.1002/9780470670170.ch1.Search in Google Scholar

Stojanowski, C. M., & Schillaci, M. A. (2006). Phenotypic approaches for understanding patterns of intracemetery biological variation. Yearbook of Physical Anthropology, 131(S43), 49–88. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20517.Search in Google Scholar

Turner, C. H. (1998). Three rules for bone adaptation to mechanical stimuli. Bone, 23(5), 399–407. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(98)00118-5.Search in Google Scholar

Umbelino, C. (2006). Outros sabores do passado: As análises de oligoelementos e de isótopos estáveis na reconstituição da dieta das comunidades humanas do Mesolítico Final e do Neolítico Final-Calcolítico do território português. Coimbra: University of Coimbra.Search in Google Scholar

Umbelino, C., Gonçalves, C., Figueiredo, O., Pereira, T., Cascalheira, J., & Marreiros, J. (2015). Life in the Muge shell middens: Inferences from the new skeletons recovered from Cabeço da Amoreira. In N. Bicho, C. Detry, T. Price, & E. Cunha (Eds.), Muge 150th: The 150th anniversary of the discovery of Mesolithic Shellmiddens (Vol. 1, pp. 209–224). Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Valera, A. C., Santos, H., Figueiredo, M., & Granja, R. (2014). Contextos funerários na periferia do Porto Torrão: Cardim 6 e Carrascal 2. In A. C. Silva, F. T. Regala, & M. Martinho (Eds.), 4 Colóquio de Arqueologia do Alqueva (pp. 83–95). Évora: EDIA/DRCAlen.Search in Google Scholar

Villalba-Mouco, V., van de Loosdrecht, M. S., Posth, C., Mora, R., Martínez-Moreno, J., Rojo-Guerra, M., … Haak, W. (2019). Survival of Late Pleistocene Hunter-Gatherer Ancestry in the Iberian Peninsula. Current Biology, 29(7), 1169–1177.e1167. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.02.006.Search in Google Scholar

Villotte, S., Castex, D., Couallier, V., Dutour, O., Knüsel, C. J., & Henry-Gambier, D. (2010). Enthesopathies as occupational stress markers: Evidence from the upper limb. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 142(2), 224–234. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21217.Search in Google Scholar

Villotte, S., Churchill, S. E., Dutour, O. J., & Henry-Gambier, D. (2010). Subsistence activities and the sexual division of labor in the European Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic: Evidence from upper limb enthesopathies. Journal of Human Evolution, 59(1), 35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.02.001.Search in Google Scholar

von Cramon-Taubadel, N. (2011). Global human mandibular variation reflects differences in agricultural and hunter-gatherer subsistence strategies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(49), 19546–19551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113050108.Search in Google Scholar

Zelditch, M. L., Swiderski, D. L., Sheets, H. D., & Fink, W. L. (2012). Geometric Morphometrics for biologists: A primer. New York: Elsevier.Search in Google Scholar

Zilhão, J. (2000). From the Mesolithic to the Neolithic in the Iberian Peninsula. In T. Price (Ed.), Europe’s first farmers (pp. 144–182). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511607851.007Search in Google Scholar

Zilhão, J. (2001). Radiocarbon evidence for maritime pioneer colonization at the origins of farming in west Mediterranean Europe. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98(24), 14180–14185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241522898.Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Ricardo Miguel Godinho et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial

- Editorial: Open Archaeology in Challenging Times

- Regular Articles

- Caves, Senses, and Ritual Flows in the Iberian Iron Age: The Territory of Edeta

- Tutankhamun’s Polychrome Wooden Shawabtis: Preliminary Investigation for Pigments and Gilding Characterization and Indirect Dating of Previous Restorations by the Combined Use of Imaging and Spectroscopic Techniques

- When TikTok Discovered the Human Remains Trade: A Case Study

- Nuraghi as Ritual Monuments in the Sardinian Bronze and Iron Ages (circa 1700–700 BC)

- A Pilot Study in Archaeological Metal Detector Geophysical Survey

- A Blocked-Out Capital from Berenike (Egyptian Red Sea Coast)

- The Winery in Context: The Workshop Complex at Ambarçay, Diyarbakır (SE Turkey)

- Tracing Maize History in Northern Iroquoia Through Radiocarbon Date Summed Probability Distributions

- Faunal Remains Associated with Human Cremations: The Chalcolithic Pits 16 and 40 from the Perdigões Ditched Enclosures (Reguengos de Monsaraz, Portugal)

- A Multi-Method Study of a Chalcolithic Kiln in the Bora Plain (Iraqi Kurdistan): The Evidence From Excavation, Micromorphological and Pyrotechnological Analyses

- Potters’ Mobility Contributed to the Emergence of the Bell Beaker Phenomenon in Third Millennium BCE Alpine Switzerland: A Diachronic Technology Study of Domestic and Funerary Traditions

- From Foragers to Fisher-Farmers: How the Neolithisation Process Affected Coastal Fisheries in Scandinavia

- Enigmatic Bones: A Few Archaeological, Bioanthropological, and Historical Considerations Regarding an Atypical Deposit of Skeletonized Human Remains Unearthed in Khirbat al-Dusaq (Southern Jordan)

- Who Was Buried at the Petit-Chasseur Site? The Contribution of Archaeometric Analyses of Final Neolithic and Bell Beaker Domestic Pottery to the Understanding of the Megalith-Erecting Society of the Upper Rhône Valley (Switzerland, 3300–2200 BC)

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Britain In or Out of Europe During the Late Mesolithic? A New Perspective of the Mesolithic–Neolithic Transition”

- Review Article

- Archaeological Practices and Societal Challenges

- Special Issue Published in Cooperation with Meso’2020 – Tenth International Conference on the Mesolithic in Europe, edited by Thomas Perrin, Benjamin Marquebielle, Sylvie Philibert, and Nicolas Valdeyron - Part I

- Animal Teeth and Mesolithic Society

- A Matter of Scale: Responses to Landscape Changes in the Oslo Fjord, Norway, in the Mesolithic

- Chipped Stone Assemblage of the Layer B of the Kamyana Mohyla 1 Site (South-Eastern Ukraine) and the Issue of Kukrek in the North Meotic Steppe Region

- Rediscovered Mesolithic Rock Art Collection from Kamyana Mohyla Complex in Eastern Ukraine

- Mesolithic Montology

- A Little Mystery, Mythology, and Romance: How the “Pigmy Flint” Got Its Name

- Preliminary Results and Research Perspectives on the Submerged Stone Age Sites in Storstrømmen, Denmark

- Techniques and Ideas. Zigzag Motif, Barbed Line, and Shaded Band in the Meso-Neolithic Bone Assemblage at Zamostje 2, Volga-Oka Region (Russia)

- Modelling Foraging Cultures According to Nature? An Old and Unfortunately Forgotten Anthropological Discussion

- Mesolithic and Chalcolithic Mandibular Morphology: Using Geometric Morphometrics to Reconstruct Incomplete Specimens and Analyse Morphology

- Britain In or Out of Europe During the Late Mesolithic? A New Perspective of the Mesolithic–Neolithic Transition

- Non-Spatial Data and Modelling Multiscale Systems in Archaeology

- Living in the Mountains. Late Mesolithic/Early Neolithic Settlement in Northwest Portugal: Rock Shelter 1 of Vale de Cerdeira (Vieira do Minho)

- Enculturating Coastal Environments in the Middle Mesolithic (8300–6300 cal BCE) – Site Variability, Human–Environment Relations, and Mobility Patterns in Northern Vestfold, SE-Norway

- Why Mesolithic Populations Started Eating Crabs on the European Atlantic Façade Only Over the Past 15 Years?

- “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” – Mesolithic Colonisation Processes and Landscape Usage of the Inner-Alpine Region Kleinwalsertal (Prov. Vorarlberg, Western Austria)

- Mesolithic Freshwater Fishing: A Zooarchaeological Case Study

- Consumers, not Contributors? The Study of the Mesolithic and the Study of Hunter-Gatherers

- Fish Processing in the Iron Gates Region During the Transitional and Early Neolithic Period: An Integrated Approach

- Hunting for Hide. Investigating an Other-Than-Food Relationship Between Stone Age Hunters and Wild Animals in Northern Europe

- Changing the Perspective, Adapting the Scale: Macro- and Microlithic Technologies of the Early Mesolithic in the SW Iberian Peninsula

- Fallen and Lost into the Abyss? A Mesolithic Human Skull from Sima Hedionda IV (Casares, Málaga, Iberian Peninsula)

- Evolutionary Dynamics of Armatures in Southern France in the Late Mesolithic and Early Neolithic

- Combining Agent-Based Modelling and Geographical Information Systems to Create a New Approach for Modelling Movement Dynamics: A Case Study of Mesolithic Orkney

- Pioneer Archaeologists and the Influence of Their Scientific Relationships on Mesolithic Studies in North Iberia

- Neolithisation in the Northern French Alps: First Results of the Lithic Study of the Industries of La Grande Rivoire Rockshelter (Isère, France)

- Late Mesolithic Individuals of the Danube Iron Gates Origin on the Dnipro River Rapids (Ukraine)? Archaeological and Bioarchaeological Records

- Special Issue on THE EARLY NEOLITHIC OF EUROPE, edited by F. Borrell, I. Clemente, M. Cubas, J. J. Ibáñez, N. Mazzucco, A. Nieto-Espinet, M. Portillo, S. Valenzuela-Lamas, & X. Terradas - Part II

- Early Neolithic Large Blades from Crno Vrilo (Dalmatia, Croatia): Preliminary Techno-Functional Analysis

- The Neolithic Flint Quarry of Pozarrate (Treviño, Northern Spain)

- From Anatolia to Algarve: Assessing the Early Stages of Neolithisation Processes in Europe

- What is New in the Neolithic? – A Special Issue Dedicated to Lech Czerniak, edited by Joanna Pyzel, Katarzyna Inga Michalak & Marek Z. Barański

- What is New in the Neolithic? – Celebrating the Academic Achievements of Lech Czerniak in Honour of His 70th Birthday

- Do We Finally Know What the Neolithic Is?

- Intermarine Area Archaeology and its Contribution to Studies of Prehistoric Europe

- Households and Hamlets of the Brześć Kujawski Group

- Exploiting Sheep and Goats at the Late Lengyel Settlement in Racot 18

- Colonists and Natives. The Beginning of the Eneolithic in the Middle Warta Catchment. 4500–3500 BC

- Is It Just the Location? Visibility Analyses of the West Pomeranian Megaliths of the Funnel Beaker Culture

- An Integrated Zooarchaeological and Micromorphological Perspective on Midden Taphonomy at Late Neolithic Çatalhöyük

- The Neolithic Sequence of the Middle Dunajec River Basin (Polish Western Carpathians) and Its Peculiarities

- Great Transformation on a Microscale: The Targowisko Settlement Region

- Special Issue on Digital Methods and Typology, edited by Gianpiero Di Maida, Christian Horn & Stefanie Schaefer-Di Maida

- Digital Methods and Typology: New Horizons

- Critique of Lithic Reason

- Unsupervised Classification of Neolithic Pottery From the Northern Alpine Space Using t-SNE and HDBSCAN

- A Boat Is a Boat Is a Boat…Unless It Is a Horse – Rethinking the Role of Typology

- Quantifying Patterns in Mortuary Practices: An Application of Factor Analysis and Cluster Analysis to Data From the Taosi Site, China

- Reexamining Ceramic Standardization During Agricultural Transition: A Geometric Morphometric Investigation of Initial – Early Yayoi Earthenware, Japan

- Statistical Analysis of Morphometric Data for Pottery Formal Classification: Variables, Procedures, and Digital Experiences of Medieval and Postmedieval Greyware Clustering in Catalonia (Twelfth–Nineteenth Centuries AD)

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial

- Editorial: Open Archaeology in Challenging Times

- Regular Articles

- Caves, Senses, and Ritual Flows in the Iberian Iron Age: The Territory of Edeta

- Tutankhamun’s Polychrome Wooden Shawabtis: Preliminary Investigation for Pigments and Gilding Characterization and Indirect Dating of Previous Restorations by the Combined Use of Imaging and Spectroscopic Techniques

- When TikTok Discovered the Human Remains Trade: A Case Study

- Nuraghi as Ritual Monuments in the Sardinian Bronze and Iron Ages (circa 1700–700 BC)

- A Pilot Study in Archaeological Metal Detector Geophysical Survey

- A Blocked-Out Capital from Berenike (Egyptian Red Sea Coast)

- The Winery in Context: The Workshop Complex at Ambarçay, Diyarbakır (SE Turkey)

- Tracing Maize History in Northern Iroquoia Through Radiocarbon Date Summed Probability Distributions

- Faunal Remains Associated with Human Cremations: The Chalcolithic Pits 16 and 40 from the Perdigões Ditched Enclosures (Reguengos de Monsaraz, Portugal)

- A Multi-Method Study of a Chalcolithic Kiln in the Bora Plain (Iraqi Kurdistan): The Evidence From Excavation, Micromorphological and Pyrotechnological Analyses

- Potters’ Mobility Contributed to the Emergence of the Bell Beaker Phenomenon in Third Millennium BCE Alpine Switzerland: A Diachronic Technology Study of Domestic and Funerary Traditions

- From Foragers to Fisher-Farmers: How the Neolithisation Process Affected Coastal Fisheries in Scandinavia

- Enigmatic Bones: A Few Archaeological, Bioanthropological, and Historical Considerations Regarding an Atypical Deposit of Skeletonized Human Remains Unearthed in Khirbat al-Dusaq (Southern Jordan)

- Who Was Buried at the Petit-Chasseur Site? The Contribution of Archaeometric Analyses of Final Neolithic and Bell Beaker Domestic Pottery to the Understanding of the Megalith-Erecting Society of the Upper Rhône Valley (Switzerland, 3300–2200 BC)

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Britain In or Out of Europe During the Late Mesolithic? A New Perspective of the Mesolithic–Neolithic Transition”

- Review Article

- Archaeological Practices and Societal Challenges

- Special Issue Published in Cooperation with Meso’2020 – Tenth International Conference on the Mesolithic in Europe, edited by Thomas Perrin, Benjamin Marquebielle, Sylvie Philibert, and Nicolas Valdeyron - Part I

- Animal Teeth and Mesolithic Society

- A Matter of Scale: Responses to Landscape Changes in the Oslo Fjord, Norway, in the Mesolithic

- Chipped Stone Assemblage of the Layer B of the Kamyana Mohyla 1 Site (South-Eastern Ukraine) and the Issue of Kukrek in the North Meotic Steppe Region

- Rediscovered Mesolithic Rock Art Collection from Kamyana Mohyla Complex in Eastern Ukraine

- Mesolithic Montology

- A Little Mystery, Mythology, and Romance: How the “Pigmy Flint” Got Its Name

- Preliminary Results and Research Perspectives on the Submerged Stone Age Sites in Storstrømmen, Denmark

- Techniques and Ideas. Zigzag Motif, Barbed Line, and Shaded Band in the Meso-Neolithic Bone Assemblage at Zamostje 2, Volga-Oka Region (Russia)

- Modelling Foraging Cultures According to Nature? An Old and Unfortunately Forgotten Anthropological Discussion

- Mesolithic and Chalcolithic Mandibular Morphology: Using Geometric Morphometrics to Reconstruct Incomplete Specimens and Analyse Morphology

- Britain In or Out of Europe During the Late Mesolithic? A New Perspective of the Mesolithic–Neolithic Transition

- Non-Spatial Data and Modelling Multiscale Systems in Archaeology

- Living in the Mountains. Late Mesolithic/Early Neolithic Settlement in Northwest Portugal: Rock Shelter 1 of Vale de Cerdeira (Vieira do Minho)

- Enculturating Coastal Environments in the Middle Mesolithic (8300–6300 cal BCE) – Site Variability, Human–Environment Relations, and Mobility Patterns in Northern Vestfold, SE-Norway

- Why Mesolithic Populations Started Eating Crabs on the European Atlantic Façade Only Over the Past 15 Years?

- “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” – Mesolithic Colonisation Processes and Landscape Usage of the Inner-Alpine Region Kleinwalsertal (Prov. Vorarlberg, Western Austria)

- Mesolithic Freshwater Fishing: A Zooarchaeological Case Study

- Consumers, not Contributors? The Study of the Mesolithic and the Study of Hunter-Gatherers

- Fish Processing in the Iron Gates Region During the Transitional and Early Neolithic Period: An Integrated Approach

- Hunting for Hide. Investigating an Other-Than-Food Relationship Between Stone Age Hunters and Wild Animals in Northern Europe

- Changing the Perspective, Adapting the Scale: Macro- and Microlithic Technologies of the Early Mesolithic in the SW Iberian Peninsula

- Fallen and Lost into the Abyss? A Mesolithic Human Skull from Sima Hedionda IV (Casares, Málaga, Iberian Peninsula)

- Evolutionary Dynamics of Armatures in Southern France in the Late Mesolithic and Early Neolithic

- Combining Agent-Based Modelling and Geographical Information Systems to Create a New Approach for Modelling Movement Dynamics: A Case Study of Mesolithic Orkney

- Pioneer Archaeologists and the Influence of Their Scientific Relationships on Mesolithic Studies in North Iberia

- Neolithisation in the Northern French Alps: First Results of the Lithic Study of the Industries of La Grande Rivoire Rockshelter (Isère, France)

- Late Mesolithic Individuals of the Danube Iron Gates Origin on the Dnipro River Rapids (Ukraine)? Archaeological and Bioarchaeological Records

- Special Issue on THE EARLY NEOLITHIC OF EUROPE, edited by F. Borrell, I. Clemente, M. Cubas, J. J. Ibáñez, N. Mazzucco, A. Nieto-Espinet, M. Portillo, S. Valenzuela-Lamas, & X. Terradas - Part II

- Early Neolithic Large Blades from Crno Vrilo (Dalmatia, Croatia): Preliminary Techno-Functional Analysis

- The Neolithic Flint Quarry of Pozarrate (Treviño, Northern Spain)

- From Anatolia to Algarve: Assessing the Early Stages of Neolithisation Processes in Europe

- What is New in the Neolithic? – A Special Issue Dedicated to Lech Czerniak, edited by Joanna Pyzel, Katarzyna Inga Michalak & Marek Z. Barański

- What is New in the Neolithic? – Celebrating the Academic Achievements of Lech Czerniak in Honour of His 70th Birthday

- Do We Finally Know What the Neolithic Is?

- Intermarine Area Archaeology and its Contribution to Studies of Prehistoric Europe

- Households and Hamlets of the Brześć Kujawski Group

- Exploiting Sheep and Goats at the Late Lengyel Settlement in Racot 18

- Colonists and Natives. The Beginning of the Eneolithic in the Middle Warta Catchment. 4500–3500 BC

- Is It Just the Location? Visibility Analyses of the West Pomeranian Megaliths of the Funnel Beaker Culture

- An Integrated Zooarchaeological and Micromorphological Perspective on Midden Taphonomy at Late Neolithic Çatalhöyük

- The Neolithic Sequence of the Middle Dunajec River Basin (Polish Western Carpathians) and Its Peculiarities

- Great Transformation on a Microscale: The Targowisko Settlement Region

- Special Issue on Digital Methods and Typology, edited by Gianpiero Di Maida, Christian Horn & Stefanie Schaefer-Di Maida

- Digital Methods and Typology: New Horizons

- Critique of Lithic Reason

- Unsupervised Classification of Neolithic Pottery From the Northern Alpine Space Using t-SNE and HDBSCAN

- A Boat Is a Boat Is a Boat…Unless It Is a Horse – Rethinking the Role of Typology

- Quantifying Patterns in Mortuary Practices: An Application of Factor Analysis and Cluster Analysis to Data From the Taosi Site, China

- Reexamining Ceramic Standardization During Agricultural Transition: A Geometric Morphometric Investigation of Initial – Early Yayoi Earthenware, Japan

- Statistical Analysis of Morphometric Data for Pottery Formal Classification: Variables, Procedures, and Digital Experiences of Medieval and Postmedieval Greyware Clustering in Catalonia (Twelfth–Nineteenth Centuries AD)