Abstract

The aims of this research were to calculate marketing efficiency and to identify the information sources of cattle farmers who select direct or indirect channel of cattle selling. This study used a descriptive research design. Respondents in this research were determined by quota and judgmental sampling methods. Data were collected through observation and in-depth interviews. Data collected were analyzed descriptively. The results showed that 66.67% and 33.33% of farmers selected indirect channel and direct channel, respectively. Among the latter, all the farmers sold to butcher, inter-island traders, or end consumers on Muslim religious ceremony. Indirect channel farmers obtained 83.72% of producer’s share, while in the direct selling method farmers obtained the entire share. However, marketing efficiency of indirect marketing channel was better with 20.22 than the direct marketing channel with 29.70. Furthermore, in the direct marketing channel, most farmers received information from buyers (25.86%) and farmers in the indirect marketing channel received from family members (20.29%). All farmers obtained similar impersonal information from televised media. In conclusion, farmers in direct channel received more income but indirect marketing channel gave a better marketing efficiency. Lastly, majority of farmers in both channels received information from personal sources.

1 Introduction

Bali cattle (Bos javanicus domesticus) is a major cattle breed in Bali Province, Indonesia. This breed is favorable for smallholder livestock and transportation system because of the small average size, fertility, and low calf mortality [1,2]. As one of the cattle germplasm sources in Indonesia, Bali restricts the entrance of non-Bali cattle into its territory to maintain the breed purity [2]. Bali cattle are spread over some provinces in Indonesia [3], such as Gorontalo, West Nusa Tenggara, East Nusa Tenggara, South Sumatera, Lampung, and South Kalimantan [4]. Based on the data from Livestock and Animal Health Statistics in 2019 for the last 5 years, Bali occupies the fifth position as the island with the high contribution of beef cattle in 2019. Bali cattle in 2004 contributed 27% of the total national population [5]; an average of 49,138 beef cattle to the outside of Bali is supplied by Bali cattle [6] to fulfill meat demands of the largest meat market in Indonesia, such as Jakarta and West Java [7].

Channel selection plays a critical role in livestock marketing activities, and it requires major attention [8,9]. Some previous studies showed that Bali cattle farmers preferred to choose indirect marketing channels through the intermediaries or middlemen as a liaison between farmers and slaughterhouses or inter-island traders [10,11,12,13]. This is similar to in the other regions of Indonesia such as Langkat, North Sumatera [14], West Sumatera [15], and East Timor [16], and previous research shows that cattle selling through an intermediate still dominated in Bali cattle marketing [11,12]. Earlier study [13] showed in 2010 majority (77.42%) of farmers in Bali Province sold cattle through middlemen. By adopting this system, the margin share received by farmers was around 63.48–69.03% and the rest belong to marketing agencies. The involvement of intermediaries in the marketing of cattle in Bali is quite high, which causes the marketing channel to be longer, thus giving losses to farmers [11,13,17]. Therefore, many researchers have suggested to shorten the marketing chain [11,12]. However, Kotler and Armstrong [18] explain that intermediaries contribute in providing product to the target market. Intermediaries count on their relationships, experience, negotiations, and territorial reachment to carry out their duties.

Based on previous studies, insufficient access to markets, limited financial transactions, and a lack of information and knowledge often restrict opportunities for small-scale farmers to link to the commercial value chain [19]. There is no denying that information was an important key in farming activities to reduce uncertainty in livestock sales [20] and general agricultural management [21] as it helps farmers’ decision-making process to increase productivity [22]. In addition, information enables farmers to make economic decisions regarding market interactions, either to purchase or sell, and therefore increase farmer’s comparative advantages [23]. Lack of marketing information increases transaction costs and reduces market efficiency. Therefore, farmers need an accurate and timely information to increase market knowledge that is important in the bargaining process [23].

A study on relation of sources of information and marketing channel choice has not been carried on in Bali cattle farmers; therefore, it is important to conduct this study to identify the sources of information of farmers and to analyze the difference of information obtaining by farmers who choose direct or indirect selling to the buyers. The result would be important to understand the farmer’s decision making whether they tend to sell the cattle directly or through a middleman. Besides, it would be a valuable input for all stakeholders to have a better understanding of the role of each element in the cattle industry and to be more thoughtful to improve the performance of cattle industry.

2 Theoretical framework

2.1 Marketing channels

Agriculture was essential socioeconomically because most poor rural people depend on agriculture for their livelihoods in most developing countries [24]. The choice of marketing channels in agribusiness is an important factor as it affects transaction returns and coordination efficiency of the value chain. A proper marketing channel leads to decrease in cost along with value chain, and therefore, lower prices would be received by end consumers [25].

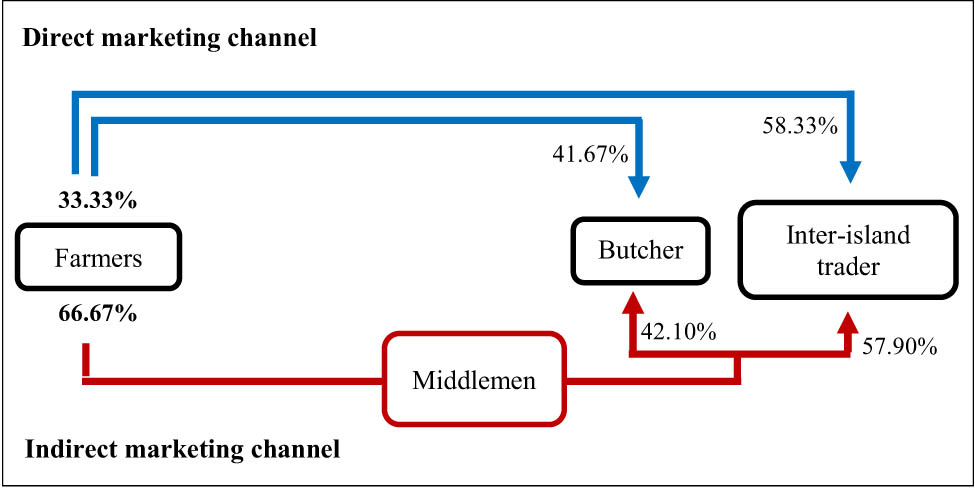

Marketing channels were divided into direct and indirect marketing channels [18] as shown in Figure 1. In direct marketing channel, producer undertakes all marketing activities and directly sells the product to consumer without any intermediaries’ involvement. Besides, indirect channels involve one or more intermediaries in marketing activities that allow funding reduction that spent by any intermediary in the value chain and at the same time it would be more efficient as everyone in this system dedicates more to its roles, despite the great effort in coordinating is required [25].

![Figure 1

Marketing channels. Source: Adapted from [18].](/document/doi/10.1515/opag-2021-0018/asset/graphic/j_opag-2021-0018_fig_001.jpg)

Marketing channels. Source: Adapted from [18].

However, the marketing intermediaries of indirect channels may have their own individual goals, which lead to conflict and power relationships [25], for example, looking for greater profit for themselves. While agricultural production in rural economies was dispersed geographically, so are individual small-scale producers who were characterized by having limited or no direct access to larger area of regional and central markets. As a result, to sell their products, farmers must transact with marketing intermediaries at the farm gate [26].

Different intermediaries were taking different margins according to the form of dates and locality [27]. According to some studies [14,15,16], intermediaries are commonly included in the marketing process of the commodity. In Langkat District, West Sumatera, and East Nusa Tenggara, there are multiple marketing channels of beef cattle that involve one to five different intermediates. The longer the marketing channel, the greater the marketing cost is. High marketing cost of indirect channel tends to depress prices received by farmers, and end consumers must pay a higher price [15]. More intermediaries cause higher marketing margin and impact on inefficiency. Based on the study by Syahdani et al. [14], the shorter marketing channel increases the marketing efficiency of beef cattle. Therefore, it is likely that:

H1: Long marketing channels in Bali beef cattle market lead to market inefficiency.

2.2 Information sources

The present study defined information needs as a situation that arises when an individual or member of the community encounters a problem that can be resolved through some information. This means that when someone identifies the information needed, the next step is seeking information to meet those needs [28]. Research in agricultural markets suggests that information accessibility affects the capability of farmers to seek various selling prices [29]. The model of the information-seeking behaviour proposed in this study was based on the study by Mahindarathne and Min [30], who developed a model based on Wilson s model in 1996 (Figure 2).

![Figure 2

Wilson’s information-seeking behavior of farmers model. Source: Adapted from [30].](/document/doi/10.1515/opag-2021-0018/asset/graphic/j_opag-2021-0018_fig_002.jpg)

Wilson’s information-seeking behavior of farmers model. Source: Adapted from [30].

In the adapted model, there were two “activating mechanisms” defined according to the context of agriculture. The first activating mechanism was related to the information needs decision: why and what. There were four categories of activating factors, such as production and technological factors, marketing factors, environmental and health factors, and policy and legal factors. These categories were related to the farmers’ uncertainty and create the farmers’ information needs. The second activating mechanism was related to information search decisions (when and how). As shown, information-seeking behavior is influenced by the sources of information; therefore, the risks and rewards of characteristics that are associated with the sources of information influence farmers’ information search decisions [30].

Farmers need comprehensive market information to make the right decision on the amount of product to sell and at market and at what price [31]. The market efficiency to determine price is affected by the information available to the market participants [29]. According to Dlamini and Huang [32], an accurate market information availability helps farmers to access market channels with higher market incentives; thus, it is important to encourage farmers to participate at the market and extent the scope of market range. According to Donkor et al. [33], access to market information also increases farmers’ bargaining power, and this allows farmers in negotiation to get a higher price. Based on the study by Koontz and Ward [29], reducing public information was found to increase price variance and decreased production efficiency.

Conceptually, the source of marketing information in the agricultural industry can be categorized into two types: personal and impersonal. The personal information source is gathered by face-to-face interaction between farmers and the informants, and impersonal information source is gathered without any direct interactions [34]. Personal information sources for farmers comprise extension agents, fellow farmers, group leaders, family members, and consumers. Meanwhile, impersonal information sources contain radio, televised media, books, newspapers, magazines, brochures, and online media. There were several factors influencing cattle farmers in deciding what information sources to be chosen as the credibility sources [35].

The preferences of information sources vary from farmers to farmers [36]. Personal information sources such as relatives, friends, fellow farmers [23], family members, and extension officers [21] were major information sources among farmers and considered effective in the provision of relevant information that contributes to market participation [37]. Farmers must be more active in seeking information as knowledge that relates to the business was essential to improve agriculture productivity and income [38]. Although television was one of the effective mediums of communication for the dissemination of agriculture information among farmers [39], agriculture activities keep farmers busy, without having enough time to listen to the radio or watch television [40]. Therefore, the hypothesis can be stated as follows:

H2: Personal sources information is the most preferred, motivated, and received by farmers.

3 Material and methods

3.1 Location

This research was conducted in eight districts and one municipality in Bali Province held in July 2019 to January 2020 as Bali Province was one of the beef cattle central regions in Indonesia and contributes the ninth rank with a total of 3.14% beef cattle population on the national scale. Furthermore, Bali Province has been designated as the purification area of Bali cattle in Indonesia [41]. Apart from the national level, as the first tourist destination in the world, cattle farms in Bali also contribute to fulfilling meat demand on the island. Therefore, the existence of beef cattle was important in Bali and at the national level.

3.2 Data collection

The number of respondents involved in this research was 33 farmers and 19 middlemen from eight districts and one municipality in Bali Province. Respondents in this research were chosen by quota and judgmental sampling methods. The quota sampling method was used to choosing five farmers from each area. The quota sampling method was a stratified sampling that aims to ensure certain groups were represented and a sufficient number to be analyzed, but the results cannot be projected onto a larger population [42]. Then, a judgmental sampling method was used to select Bali beef cattle farmers with a minimum of 2 years of experience from the total of a quota sampling method.

Middlemen in this research were chosen through the snowball sampling method from farmers’ information. A semi-structured questionnaire was used to collect data about information sources type: the most preferred, motivating, readily accepted, and easily understood sources of information. All data obtained were further analyzed descriptively. The sample used in this study was not representative of the overall population of agricultural producers in the sampled areas. However, these results mean that more research is needed with more representative samples to determine whether the conclusions drawn can be extended to the population.

The data collection was conducted through observation and in-depth interviews to identify the sources of information and marketing channels. Observation is a supervisory approach to collect data by examining the subject’s activity or properties of a material without conducting experiments to get answers [42]. The observation in this research was carried out using the non-participative observation method, without interacting with participants but recording their behavior [43]. An in-depth interview includes intensive interviews of individuals with a small number of respondents to explore their perspectives on a particular thought, program, or situation. The number of samples can be said to be sufficient when the stories, themes, problems, and topics that arise from the interview are saturated [44].

The research instrument uses a questionnaire with open questions. The questions related to why and how farmers manage their cattle. Why farmers still manage their cattle? Why and how are they selling their cattle? How are they collecting the livestock information? (Appendix).

-

Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Ethical approval: The research related to human use has been complied with all the relevant national regulations, institutional policies and in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration, and has been approved by the authors’ institutional review board or equivalent committee.

3.3 Data analysis

Descriptive statistics with percentages and frequencies were used to analyze the marketing channels and information sources of Bali beef cattle marketing actors. Bali beef cattle marketing in Bali Province was classified to direct and indirect marketing channels. Direct marketing channels is a term for producer who sells the product directly to consumers without any intermediaris. While in indirect marketing channels, there are one or more intermediaries or middleman who involve in the marketing process such as collectors or wholesalers.

Efficient marketing plays an important role in increasing the producer’s share in the consumer’s take and maintain the tempo of increased production. Four indicators were used for measuring efficiency in different marketing channels. These indicators were marketing cost, marketing margin, marketing profit, and percentage of producer’s share of product related to the last cattle sold by farmers 1 year before the research was conducted.

The total of marketing cost was determined by the following formula [45]:

where I = total cost of marketing, C p = producer cost of marketing, and Mc i = marketing cost by the i-th trader.

Margins represent the price charged by marketing agencies for all services provided, including buying, packing, transportation, storage, and processing. Marketing margins were commonly used to examine the difference between producer and consumer prices for the same quantity of a commodity [27]. The marketing margin of Bali beef cattle farmers in Bali Province was determined by the following formula [45]:

where MM = marketing margin, Sp = selling price, and Pp = purchase price.

Marketing profit was calculated by the following formula [45]:

where MP = marketing profit, MM = marketing margin, and MC = marketing cost.

The producer’s share was calculated by the following formula:

where Sppi = producer’s share in the i-th channel, Spri = average price at the retail level in each channel, and i = number of channels (i = 1, 2,…, n).

Marketing efficiency of Bali cattle marketing in Bali Province was calculated with the formula given by Shepherd (1965) in ref. [46]:

where ME = index of marketing efficiency, V = consumer price, and I = total marketing cost. Financial measurement did not follow international accounting standard but based on measurement of financial that applicable smallholder agribusiness in Indonesia.

Observation in this research was conducted in beef cattle markets, such as Bebandem, Pesinggahan, and Beringkit market in Bali Province. Observations were conducted as supporting data by observing the Bali beef cattle marketing process related to the interaction between farmers and buyers, the bargaining power of each marketing actors, transactions, and transportation processes.

4 Results and discussion

Bali beef marketing in Bali Province was conducted through direct and indirect marketing channels. The results showed that 66.67% of farmers selected to use middlemen services in selling the cattle, and the rest of 33.33% directly meet the buyers (Figure 3).

Marketing channel in Bali beef cattle in Bali Province. Source: Primary data (2020).

Marketing efficiency was calculated based on marketing cost, marketing margin, marketing profit, and percentage of the producer’s share of the product. These calculations were based on price and cost data issued by farmers and intermediate involved in beef cattle marketing channels in Bali Province (Table 1).

Price and cost of beef cattle marketing in Bali Province (IDR/head)

| Actors/particulars | Marketing channels | |

|---|---|---|

| Direct | Indirect | |

| Farmers | ||

| Purchase price (Pp) | 8,158,333.33 | 6,250,000.00 |

| Production cost (feed and medicine) | 1,252,523.81 | 928,429.00 |

| Marketing cost (Cp) | 515,000.00 | 2,750.00 |

| Selling price (Sp) | 15,809,600.00 | 12,062,500.00 |

| Middlemen | ||

| Purchase price (Pp) | — | 12,062,500.00 |

| Marketing cost (Mci) | — | 676,335.00 |

| Selling price (Sp) | — | 14,408,148.00 |

| Consumer price (V) | 15,809,600.00 | 14,408,148.00 |

Note: IDR = Indonesia currency; $1 = IDR 14,021.11 (January 24, 2021).

Table 1 shows that the cost of calf purchases was different between direct and indirect marketing channels. Farmers in direct channel were aiming to sell the cattle for Muslim ceremony events, i.e., Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha. Demand on this special occasion required good quality posture cattle; therefore, farmers choose good quality calf to fulfill the market need. Otherwise, farmers in the indirect channel bought calf based on the amount of money they held, and calf quality was not the priority. The purpose of indirect channel farmers was to make livestock as savings – farmers in this group sell cattle when they need money to pay tuition costs, health care, and/or any religious ceremony. Furthermore, production cost was sum of feed cost including forage and concentrate, medicine, and vitamin. Direct channel production costs were relatively higher than the indirect channel. It can be understood as market of farmers in direct channels who buy cattle for religious ceremonies have higher willingness to pay [47].

In indirect channels, farmers obtained 83.72% producer share, and middlemen obtained 16.28%, while in direct marketing channels farmers had all the producer share. Farmers in direct marketing channels received higher income compared with marketing costs almost 100% than farmers in indirect marketing channels. Even farmers received more income in direct channels, selling through middlemen at the farm gate was still the favored choice by farmers because they do not have to bear marketing costs. The marketing efficiency through direct and indirect marketing channels was 29.70 and 20.22, respectively (Table 2).

Marketing cost, marketing margin, marketing profit, producer share, and marketing efficiency

| Particulars | Marketing channels | |

|---|---|---|

| Direct channel | Indirect channel | |

| Marketing cost (IDR/head) | 515,000.00 | 679,085.00 |

| Marketing margin (IDR/head) | 8,605,433.33 | 4,858,333.33 |

| Marketing profit (IDR/head) | 8,090,433.33 | 4,179,248.33 |

| Producer share (%) | 100.00 | 83.72 |

| Marketing efficiency | 29.70 | 20.22 |

Note: IDR = Indonesia currency; $1 = IDR 14,021.11 (January 24, 2021).

The sources of information of farmers who choose direct selling were buyers (25.86%), family members (13.79%), and extension agents (12.07%), while the sources of personal information of indirect selling farmers were family members (20.29%), extension agents (17.39%), and buyers and fellow farmers each 10.14%. The most used impersonal information sources for all farmers were televised media, respectively, 6.90% and 8.70%, while information from other media such as billboards, newspapers, magazines, brochures, books, radio, and online media have received less (Tables 3 and 4).

Information sources of farmers choosing direct marketing channels

| Information sources | Information received | Most preferable | Motivated | Easily accepted | Easily understood |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | % | |

| Personal (Pe) | |||||

| Extension agent | 12.07 | 38.46 | 18.18 | 40.00 | 22.22 |

| Fellow farmers | 8.62 | 7.69 | 18.18 | 10.00 | 11.11 |

| Leader group | 10.34 | 7.69 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Family member | 13.79 | 23.08 | 27.27 | 30.00 | 33.33 |

| Buyer | 25.86 | 7.69 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 11.11 |

| Total | 70.69 | 84.62 | 63.64 | 80.00 | 77.78 |

| Impersonal (Im) | |||||

| Billboard | 3.45 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Newspaper | 3.45 | 0.00 | 9.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Magazine | 3.45 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Brochure | 3.45 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Book | 1.72 | 7.69 | 9.09 | 10.00 | 11.11 |

| Televised media | 6.90 | 7.69 | 9.09 | 10.00 | 11.11 |

| Radio | 1.72 | 0.00 | 9.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Online media | 5.17 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Total | 29.31 | 15.38 | 36.36 | 20.00 | 22.22 |

| Total Pe + Im | 12.07 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

Note: n = 33.

Source: Primary data (2020).

Information sources of farmers choosing indirect marketing channels

| Information sources | Information received | Most preferable | Motivated | Easily accepted | Easily understood |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | % | |

| Personal (Pe) | |||||

| Extension agent | 17.39 | 21.43 | 19.05 | 28.57 | 28.57 |

| Fellow farmers | 10.14 | 17.86 | 28.57 | 23.81 | 23.81 |

| Leader group | 8.70 | 3.57 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Family member | 20.29 | 28.57 | 38.10 | 33.33 | 33.33 |

| Buyer | 10.14 | 3.57 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Total | 66.67 | 75.00 | 85.71 | 85.71 | 85.71 |

| Impersonal (Im) | |||||

| Billboard | 7.25 | 3.57 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Newspaper | 4.35 | 3.57 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Magazine | 4.35 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Book | 2.90 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Televised media | 8.70 | 10.71 | 14.29 | 14.29 | 14.29 |

| Radio | 2.90 | 3.57 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Online media | 2.90 | 3.57 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Total | 33.33 | 25.00 | 14.29 | 14.29 | 14.29 |

| Total Pe + Im | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

Note: n = 33.

Source: Primary data (2020).

In the group of farmers who select direct selling, family member informants were perceived as more motivated (27.27%) and easy to comprehend (33.33%) information, while extension agents were perceived as more preferable (38.46%) and easy to be accepted (40.00%). Then, televised media and books were perceived as the most preferred (6.90%), readily accepted (7.69%), easily understood (11.11%), and motivating (9.09%) information sources along with newspapers and radio. For farmers in indirect marketing, the family was also perceived as the most preferred (28.57%), motivating (38.10%), readily accepted (33.33%), and easily understood (33.33%) sources of information. Then, televised media were perceived as readily received (8.70%) and understood (14.29%), most preferred (10.71%), and motivating source (14.29%).

The result showed that most farmers chose indirect marketing channel. Compared with the previous studies by Dewi et al. [11] and Sukanata [12], the existence of a middleman was common in developing countries, where market failure is ubiquitous and the food chain still consists of many stages. The role of the middleman is to provide market information, to help farmers to reduce marketing risk including transportation cost, to ensure cattle were sold, and to solve time limitation of farmers [48]. This study showed that transportation facilities are provided by the middleman, attracted farmers to choose indirect marketing even though they had to share 16.28% of margin share (Table 2). Supported by Agus and Widi [48], farmers tend to choose a buyer near their area because they have no capability in transportation. It means that middlemen in this study were perceived as the problem solver.

“I only sell two cattle and it is not efficient if I bring cattle to market. I have a relationship with a middleman to sell as well as help me get new cattle, so I do not have to pay transportation cost and reduce to become a price game victim.” (M1, M2)

The role of middlemen has been criticized as their existence in the marketing process affects the decrease in farmer’s profit as indicated in Table 2. Empirical study also showed that even though cattle price is high in markets, farmers often get disadvantages in receiving substantial or equal profit because of their poor bargaining power [48]. However, the middleman carries the commodities to the market to derive large profits even market far from their location [49,50]. In this study, the majority of middlemen were the ones who sell the cattle to inter-island traders.

Data in Table 1 show that farmers in indirect marketing channels almost do not need to expense more cost to selling their cattle through middlemen. Farmers in indirect marketing channels reduce marketing costs and allocate cattle weighing jobs to a middleman [51]. It was also argued by Kohls and Uhl [52] that farmers’ income does not depend on the number of middlemen in the marketing process but the kind of activity they have done. Marketing costs would become more expensive and detrimental if more than a middleman does the same job. Another role of middleman is at a certain time, when farmers need cash payment because of the need for paying the tuition fee, health care, and preparing for religious celebration [53]; in this situation middleman, could provide cash immediately.

The main personal information source for cattle farmers in a direct marketing channel was buyer, comprised of butchers and inter-island traders. Only farmers with transportation support can meet those buyers in the slaughterhouse and cattle market. At a certain time, e.g., on Eid al-Adha and Eid al-Fitr, end consumers buy cattle directly to the cattle farms for religious purposes. At this transaction, butchers and traders inform the market situation and market price to the farmers, and both buyer and seller use this as a base for dealing with their exchange [47].

“I received cattle price information from buyer” (I1, I3)

“Cattle buyers are usually honest in informing price whether it is rising or falling. If he says there is an increase, he says it goes up and vice versa.” (M2, M3)

Obtaining cattle price information during negotiation between buyer and seller at the farm gate also occurred in South Africa [32,54]. Farmers used their information sources for decision making in the selling process [55]. Product price was a determinant factor in choosing a marketing channel because economic calculation suggests the higher price market can determine the profitability of the farm enterprise [56]. The success of negotiation between farmers and buyers at the farm gate depends on the gathered information. Sufficiency of the price information would increase farmer’s bargaining power in the negotiating process as they were not bearing any risk, such as transportation costs [57]. If there is no price agreement, it is relatively easy for farmers to postpone the transaction and wait for other buyers but with increased feeding costs.

A different result was identified for farmers who choose indirect selling. Farmers who choose indirect marketing channel received personal information from family members due to the lack of access information from external sources. Supported by some studies [21,36], information from family members was always available. Farmers with less economy and time easily accessed the information. Limitation of relations to external parties causes farmers to rely on middlemen in their marketing activities because middlemen can act as liaisons between farmers and buyers. As market information was controlled by middlemen, they become more influential in farmer’s marketing decision making [58,59].

“I’m never interested in selling to the market. It costs a lot, sometimes cattle unsuccessfully sold. If there are better cattle offered by other farmers, then it becomes a reason for better to bargain. I’ve been there with friends. The cattle were offered IDR 2.5 million but then bargained under market price, which was IDR 2 million. But if we brought back the cattle, we already spent transportation cost and meals and we got nothing.” (M1, M2)

“Selling directly to the market is hard for farmers. Besides, transport costs, usually farmers do not know the market price, and it is of course played by some players in the market. Therefore, farmers are reluctant to go to Beringkit Market, marketing costs could be more expensive. That is it.” (M1, M2)

However, preferences were not always consistent with perceptions of how information was able to motivate, easy to understand, and was trusted. For both groups of farmers, the family was perceived as motivated and easily understood sources of information and trusted informants as family members might have similar backgrounds and experience to help overcome existing problems [23,36].

This study showed that Bali cattle farmers used multiple source of information. Furthermore, televised media were the highest number of impersonal information sources for farmers in both types of marketing channels. Televised media were also the most preferred, motivating, easily accepted, and easily understood sources. According to Rahman et al. [36], televised media are beneficial to farmers as it can be accessed quickly and at a low cost. The availability of televised programs through the Bali TV and TVRI Bali channels that broadcast news and information about animal husbandry has helped farmers to manage cattle farms in Bali Province.

“The information that I get is usually from televised media programs such as on Bali TV and TVRI Bali about the disease, around IB government programs.” (M2)

Televised media were a common source of information owned by most households [36] and are also the source of entertainment for farmer households [60]. The design of educational content using televised media involved a lot of farmers and was designed to be easy to understand with informative content on various aspects relevant to production, such as disease and artificial insemination.

Farmers in direct marketing channels particularly have more connections with potential buyers such as butchers, inter-island traders, and the end consumer. The more the information, the better the farmers anticipate changing agricultural scenarios by combining those multiple sources of information [55]. Table 5 shows that in some countries and varied research context, farmers use information gathered from various sources to improve their farming activities [21,33,36,61,62,63,64,65,66]. Farmers used a wide variety of information on various issues including market and price information of input and output. Some kind of information included the availability of new inputs, technology, disease outbreak or weather forecasts, and availability of agricultural support or government schemes related to agriculture (Table 5).

Multiple information sources used by farmers

| Subject | Countries | Information sources | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dairy farmers | Punjab, India | Televised media and family members | [62] |

| Crops farmers | Alborz, Iran | Local leaders/officials, experts, televised media, and neighboring associates | [64] |

| Fish farmers | Mymensingh, Bangladesh | Neighbor, televised media, experienced farmers, radio, input dealer, newspaper, local extension agents, and farm laborer | [23,36] |

| Smallholder farmers | Tigray, Ethiopia | Farmers, agricultural professionals, health extension workers, radio, and mobile phone | [61] |

| Farmers | Haryana, India | Newspaper, state agriculture department, televised media, agricultural universities, radio | [63] |

| Vegetable farmers | Accra, Ghana | Agro-chemical shops (the practical application monitored by extension agents) and radio | [66] |

| Cassava farmers | Oyo State, Nigeria | Radio and televised media | [33] |

| Farmers | Guangdong, China | Televised media, fellow-villagers, relatives, friends, mobile calls, fixed-line phone, colleagues, or classmates | [21] |

| Crops farmers | Bangladesh | Distributors, middle-class civilians, relatives, and close associates | [65] |

Surprisingly, the results showed that indirect marketing channel performed better marketing efficiency than direct marketing channel. Here, we adopt the point of view of the consumer [46]; marketing will be efficient if the total marketing margin is reduced for a given marketing cost. In other words, among the marketing margins of the different channels, that with the lowest value would reveal a channel to be efficient. The present study revealed that marketing efficiency in indirect marketing channels was better than the direct marketing channel. The higher marketing cost of the indirect marketing channel than that of the direct marketing channel has not impaired the efficiency of indirect marketing channel. The relatively lower marketing cost in the direct marketing channel does not necessarily indicate greater efficiency as indicated in Table 2.

The marketing choice of Bali cattle was mainly indirect marketing channel. It can be explained as majority of cattle farmers were smallholder farmers with one to three heads; therefore, it would put farmers in high risk if they carry the cattle to the market. There will be a huge loss if farmers have to take the cattle back to the farm. The lack of capital made farmers to avoid the risk of failure of selling cattle at the market. Table 1 shows that cattle selling price in indirect channel was lower than direct channel. At indirect channel, middlemen at the farm gate determine cattle price only based on cattle physical judgment and more or less also affected by higher bargaining power of middlemen [67]. In contrast, farmers in direct channel weighed cattle at the market using weight scale that provided by cattle market management. By having cattle weight information, bargaining power of farmers was increased and had opportunity to get a higher price as shown in Table 1. This discussion implied as also supported by Negi et al. [68] that farmers’ risk aversion behavior prohibits farmers to sell cattle at a better price, and this impacts farmers’ wealth.

This study showed that a minority of farmers already start to use online media as information sources. The media, which offer unique opportunities to disseminate information, can play an important role in informing citizens about social, academic, and economic issues, among others [69]. Online media by farmers in Bali Province were used to find market information and make transactions by providing information on the number of livestock available. Farmers in near future can use this platform in the marketing process. Farmers do not need to depend on middlemen and could increase their income.

5 Conclusions

The involvement of intermediaries or middlemen in Bali cattle marketing channel was still the preferred option compared to the direct marketing channel because of limited capability of farmers to provide transportation facilities and take the marketing risk. Smallholder farmers kept livestock as saving and only sell cattle when they need cash; meanwhile, middlemen carry out cattle trading daily. Therefore, they have more information and experience in cattle trading. The gap of this bargaining power put more farmers to rely on intermediaries or middlemen in the cattle marketing process. Furthermore, in direct marketing channel, farmers obtained higher margin share compared to indirect marketing channel farmers that would give better wealth for farmers. However, the index of marketing efficiency of indirect channel performed at a better performance indicator which means consumers will receive a better price.

Farmers in direct marketing channels preferred more multi-information sources compared to farmers in the indirect marketing channel. In Bali Province, general marketing information of cattle is available in different sources. Buyers, family members, and extension agents were personal information sources since they were perceived more compatible, credible, and accessible for smallholders farmers.

This research has implication that government support through extension program is needed to stimulate farmers’ cooperative establishment. The larger size of farm enterprise allows farmers in cooperative to have more experience and confidence doing transaction as well as to set selling price standard.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge that some data contained in the article is sourced from the thesis of Dewi NMAK (2020) [47].

Appendix

(M) Marketing process (extracted from questionnaire)

Where do you sell the cattle? Why?

Market

Farm gate

What are the reasons you choose that place?

When do you sell the cattle? Do you sell the cattle in the special period?

(F) Financial calculation (extracted from questionnaire)

Production cost

Marketing cost

(I) Information sources used by the farmers (extracted from questionnaire)

What are your personal information sources?

What are your impersonal sources?

What kind of information you received from information sources?

-

Funding information: This project has received funding from Universitas Gadjah Mada, “Rekognisi Tugas Akhir” program under contract number 2607/UN1/DITLIT/DIT-LIT/PT/2020.

-

Author contributions: S. P. S. and F. T. H. designed and contributed in data analysis and wrote the paper. N. M. A. K. D. designed, collected the data, analyzed, and wrote the paper.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Quigley S, Dalgliesh N, Waldron S. Final report: enhancing smallholder cattle production in East Timor. Australia: ACIAR; 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Talib C, Siregar AR, Budiarti-Turner S, Diwyanto K. Strategies to improve Bali cattle in Eastern Indonesia. Aciar proceedings; 2003. p. 82–5.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Yupardhi WS. Sapi Bali Mutiara dari Bali. Bali: Udayana University Press; 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Romjali E. Program pembibitan sapi potong lokal Indonesia. Wartazoa. 2018;28(4):199–210.10.14334/wartazoa.v28i4.1813Search in Google Scholar

[5] Purwantara B, Noor RR, Andersson G, Rodriguez-Martinez H. Banteng and Bali cattle in Indonesia: status and forecasts. Reprod Domest Anim. 2012;47(1):2–6.10.1111/j.1439-0531.2011.01956.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Livestock and Animal Health Statistics. Jakarta: Direktorat Jenderal Peternakan dan Kesehatan Hewan, Kementerian Pertanian Republik Indonesia; 2019.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Suardana IW, Sukada IM, Suada IK, Widiasih DA. Analisis jumlah dan umur Sapi Bali betina produktif yang dipotong di Rumah Pemotongan Hewan Pesanggaran dan Mambal Provinsi Bali. J Sain Vet. 2013;31(1):43–8.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Andhika R, Hasnudi, Ginting N. Pengaruh rantai tataniaga terhadap efisiensi pemasaran daging sapi di Kabupaten Karo. J Peternak Integr. 2015;3(2):224–34.10.32734/jpi.v3i2.2757Search in Google Scholar

[9] Widitananto A, Sihombing G, Sari AI. Analisis pemasaran ternak sapi potong di Kecamatan Playen Kabupaten Gunung Kidul. Trop Anim Husb. 2012;1(1):59–66.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Astiti NMAGR. Impact of Bali cattle calf marketing to the farmers income. J Res Lepid. 2019;50(4):89–96.10.36872/LEPI/V50I4/201065Search in Google Scholar

[11] Dewi NMAK, Putri BRT, Sukanata IW. Marketing strategy of Bali calf to improve breeders’ income in Nusa Penida Sub District, Bali Province. J Biol Chem Res. 2018;35(2):318–22.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Sukanata IW. Pemasaran Sapi Bali. Focus group discussion, Penyelamatan Sapi Betina Produktif, BPTP, Denpasar; 2015 Oct. p. 1.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Sukanata IW, Suciani NW, Kayana IG, Budiartha IG. Penerapan Kebijakan Kuota Perdagangan dan Efisiensi Pemasaran Sapi Potong Antar Pulau. Final research report; 2010.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Syahdani A, Hasnudi, Hanafi ND. The income analysis and marketing efficiency of beef cattle business in Langkat District. J Peternak Integr. 2016;4(3):222–34.10.32734/jpi.v4i3.2799Search in Google Scholar

[15] Yuzaria RMI. Market structure of beef cattle business in Payakumbuh West Sumatera. J Adv Agric Technol. 2017;4(4):324–30.10.18178/joaat.4.4.324-330Search in Google Scholar

[16] Tiro M, Lalus MF. Spatial price connectivity in marketing beef cattle in Kupang Regency. Indonesia Russ J Agric Socio-Econ Sci. 2019;96(12):182–94.10.18551/rjoas.2019-12.23Search in Google Scholar

[17] Astiti NMAGR. Impact of Bali cattle calf marketing to the farmers income. J Res Lepid. 2019;50(4):89–96.10.36872/LEPI/V50I4/201065Search in Google Scholar

[18] Kotler P, Armstrong G. Principles of marketing. 14th ed. New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2012.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Krone M, Dannenberg P. Analysing the effects of information and communication technologies (ICTs) on the integration of East African farmers in a value chain context. Z Wirtschgeogr. 2018;62(1):65–81.10.1515/zfw-2017-0029Search in Google Scholar

[20] Kavi RK, Bugyei KA, Obeng-Koranteng G, Folitse BY. Assessing sources of information for urban mushroom growers in Accra. Ghana J Agric Food Inf. 2018;19(2):176–91.10.1080/10496505.2017.1361328Search in Google Scholar

[21] Chen Y, Lu Y. Factors influencing the information needs and information access channels of farmers: an empirical study in Guangdong, China. J Inf Sci. 2019;46(1):3–22.10.1177/0165551518819970Search in Google Scholar

[22] Thangjam B, Jha KK. Socio-economic correlates and information sources utilization by paddy farmers in Bishnupur District, Manipur, India. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2019;8(10):1652–9.10.20546/ijcmas.2019.810.192Search in Google Scholar

[23] Nwafor CU, Ogundeji AA, Westhuizen CVD. Adoption of ICT-based information sources and market participation among smallholder livestock farmers in South Africa. EconPapers. 2019;10(2):1–13.10.3390/agriculture10020044Search in Google Scholar

[24] Lwoga ET. Bridging the agricultural knowledge and information divide: the case of selected telecenters and rural radio in Tanzania. Electron J Inf Syst Dev Ctries. 2010;43(1):1–14.10.1002/j.1681-4835.2010.tb00310.xSearch in Google Scholar

[25] De Sousa Fragoso DM. Planning marketing channels: Case of the olive oil agribusiness in Portugal. J Agric Food Ind Organ. 2013;11(1):51–67.10.1515/jafio-2013-0001Search in Google Scholar

[26] Woldie GA. Optimal farmer choice of marketing channels in the Ethiopian banana market. J Agric Food Ind Organ. 2010;8(1):1–17.10.2202/1542-0485.1298Search in Google Scholar

[27] Adeel A, Aslam M, Ullah HK, Khan YM, Ayub MA. Marketing margins of selected stakeholders in the supply chain of dates in South Punjab, Pakistan. Cercet Agron Mold. 2018;51:109–24.10.2478/cerce-2018-0010Search in Google Scholar

[28] Chilimo WL, Ngulube P, Stilwell C. Information seeking patterns and telecentre operations: A case of selected rural communities in Tanzania. Libri. 2011;61(1):37–49.10.1515/libr.2011.004Search in Google Scholar

[29] Koontz SR, Ward CE. Livestock mandatory price reporting: a literature review and synthesis of related market information research. J Agric Food Ind Organ. 2011;9:9.10.2202/1542-0485.1254Search in Google Scholar

[30] Mahindarathne MGPP, Min G. Developing a model to explore the information seeking behaviour of farmers. J Doc. 2018;74(4):781–803.10.1108/JD-04-2017-0065Search in Google Scholar

[31] Kyaw NN, Ahn S, Lee SH. Analysis of the factors influencing market participation among smallholder rice farmers in Magway Region, central dry zone of Myanmar. Sustainability. 2018;10:4441.10.3390/su10124441Search in Google Scholar

[32] Dlamini SI, Huang WC. A double hurdle estimation of sales decisions by smallholder beef cattle farmers in Eswatini. Sustainability. 2019;11(19):5185.10.3390/su11195185Search in Google Scholar

[33] Donkor E, Onakuse S, Bogue J, Rios-Carmenado IDL. Determinants of farmer participation in direct marketing channels: a case study for cassava in the Oyo State of Nigeria. Span J Agric Res. 2018;16(2):e0106.10.5424/sjar/2018162-12076Search in Google Scholar

[34] Hess RL, Ring L. The influence of the source and valence of word-of-mouth information on post-failure and post-recovery evaluations. Serv Bus. 2016;10(2):319–43.10.1007/s11628-015-0272-3Search in Google Scholar

[35] Gwandu T, Mtambanengwe F, Mapfumo P, Mashavave TC, Chikowo R. Factors influencing access to integrated soil fertility management information and knowledge and its uptake among smallholder farmers in Zimbabwe. J Agric Educ Ext. 2014;20(1):79–93.10.1080/1389224X.2012.757245Search in Google Scholar

[36] Rahman MA, Lalon SB, Surya MH. Information sources preferred by the farmers in receiving farm information. Int J Agric Ext Rural Dev. 2016;3(12):258–62.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Dinku A. Assessment of constraints and opportunities in small-scale beef cattle fattening business: evidence from the West Hararghe Zone of Ethiopia. Int J Vet. 2019;5(2):58–68.10.17352/ijvsr.000042Search in Google Scholar

[38] Zhang Y, Wang L, Duan Y. Agricultural information dissemination using ICTs: a review and analysis of information dissemination models in China. Inf Process Agric. 2016;3(1):17–29.10.1016/j.inpa.2015.11.002Search in Google Scholar

[39] Chhachhar AR, Qureshi B, Khushk GM, Ahmed S. Impact of information and communication technologies in agriculture development. J Basic Appl Sci Res. 2014;4(1):281–8.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Mapiye O, Makombe G, Mapiye C, Dzama K. Management information sources and communication strategies for commercially oriented smallholder beef cattle producers in Limpopo province, South Africa. Outlook Agric. 2020;49(1):50–6.10.1177/0030727019860273Search in Google Scholar

[41] Azizah S, Arham ALD, Kusumastuti AE. The effect of comic as an introduction media of Bali cattle in Universitas Brawijaya. Erud J Educ Innov. 2019;6(2):192–205.10.18551/erudio.6-2.6Search in Google Scholar

[42] Cooper RD, Schindler PS. Business research methods. 12th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Driscoll DL. Introduction to primary research: observation, surveys, and interview. In: Lowe, Zemliansky P, editors. Writing spaces: reading on writing. 2nd ed. USA: Parlon Press and WAC Clearinghouse; 2011.Search in Google Scholar

[44] Boyce C, Neale P. Conducting in-depth interviews: a guide for designing and conducting in-depth interviews. United States: Pathfinder International; 2006.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Hasan MK, Khalequzzaman KM. Marketing efficiency and value chain analysis: the case of garlic crop in Bangladesh. Am J Trade Policy. 2017;4(1):7–18.10.18034/ajtp.v4i1.411Search in Google Scholar

[46] Solanke S, Krishnan M, Sarada C. Production, price spread and marketing efficiency of farmed shrimp in Thane District of Maharashtra. Indian J Fish. 2013;60(3):47–53.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Dewi NMAK. Saluran dan Sumber Pemasaran Sapi Bali di Provinsi Bali. Thesis. Master of Animal Science Study Program, Faculty of Animal Science, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia; 2020.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Agus A, Widi TSM. Current situation and future prospects for beef cattle production in Indonesia – a review. Asian-Aust J Anim Sci. 2018;31(7):976–83.10.5713/ajas.18.0233Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Abebe GK, Bijman J, Royer A. Are middlemen facilitators or barriers to improve smallholders’ welfare in rural economies? Empirical evidence from Ethiopia. J Rural Stud. 2016;43:203–13.10.1016/j.jrurstud.2015.12.004Search in Google Scholar

[50] Masters A. Unpleasant middlemen. J Econ Behav Organ. 2008;68(1):73–86.10.1016/j.jebo.2008.03.003Search in Google Scholar

[51] Dessie AB, Abate TM, Mekie TM. Factors affecting market outlet choice of wheat producers in North Gondar Zone, Ethiopia. Agric Food Secur. 2018;7:91.10.1186/s40066-018-0241-xSearch in Google Scholar

[52] Kohls RL, Uhl JN. Food marketing costs. Marketing of agricultural products. 5th ed. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co, Inc; 1980. p. 222.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Astiti NMAGR, Rukmini NKS, Rejeki IGADS, Balia RL. The farmer socio-economic profile and marketing channel of Bali-Calf at Bali Province. Sci Pap Manag Econ Eng Agric Rural Dev. 2019;19(1):47–51.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Mapiye O, Makombe G, Mapiye C, Dzama K. Limitations and prospects of improving beef cattle production in the smallholder sector: a case of Limpopo Province, South Africa. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2018;50(7):1711–25.10.1007/s11250-018-1632-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] Mittal S, Mehar M. Socio-economic factors affecting adoption of modern information and communication technology by farmers in India: analysis using multivariate probit model. J Agric Educ Ext. 2016;22(2):199–212.10.1080/1389224X.2014.997255Search in Google Scholar

[56] Harrizon K, Benjamin MK, Lawrence KK, Patrick KR, Anthony M. Determinants of tea marketing channel choice and sales intensity among smallholder farmers in Kericho District, Kenya. J Econ Sustain Dev. 2016;7(7):105–14.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Adugna M, Ketema M, Goshu D, Debebe S. Market outlet choice decision and its effect on income and productivity of smallholder vegetable producers in Lake Tana Basin, Ethiopia. Rev Agric Appl Econ. 2019;22(1):83–90.10.15414/raae.2019.22.01.83-90Search in Google Scholar

[58] Bassa Z, Woldeamanuel T. Market structure conduct and performance of live cattle in Borona Pastoral area: the case of Moyalle District, Oromiya Regional State. Sci Technol Int J Mod Trends. 2019;5(10):29–37.Search in Google Scholar

[59] Dinku A, Abebe B, Lemma A, Shako M. Beef cattle value chain analysis: evidence from West Hararghe Zone of Ethiopia. Int J Agric Sci Food Technol. 2019;5(1):77–87.10.17352/2455-815X.000046Search in Google Scholar

[60] Aonngernthayakorn K, Pongquan S. Determinants of rice farmers’ utilization of agricultural information in Central Thailand. J Agric Food Inf. 2017;18(1):25–43.10.1080/10496505.2016.1247001Search in Google Scholar

[61] Brhane G, Mammo Y, Negusse G. Sources of information and information seeking behaviour of smallholder farmers of Tanqa Abergelle Wereda, central zone of Tigray, Ethiopia. J Agric Ext Rural Dev. 2017;9(5):121–8.10.5897/JDAE2016.0801Search in Google Scholar

[62] Chauhan M, Kansal SK. Most preferred animal husbandry information sources and channel among dairy farmers of Punjab. Indian Res J Ext Edu. 2014;14(4):14–7.Search in Google Scholar

[63] Duhan A, Singh S. Sources of agricultural information accessed by farmers in Haryana, India. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2017;6(12):1559–65.10.20546/ijcmas.2017.612.175Search in Google Scholar

[64] Ertiaei F, Barabadi SA. Designing a model to explain the relationship between individual and communicational characteristics of farmers to agricultural product insurance. Agric Commun. 2015;3(3):48–52.Search in Google Scholar

[65] Mamun-Ur-Rashid M, Karim MM, Islam MM, Bin Mobarak MS. The usefulness of cell phones for crop farmers in selected regions of Bangladesh. Asian J Agric Rural Dev. 2019;9(2):298–312.10.18488/journal.1005/2019.9.2/1005.2.298.312Search in Google Scholar

[66] Osei SK, Folitse BY, Dzandu LP, Obeng-Koranteng G. Sources of information for urban vegetable farmers in Accra. Ghana Inf Dev. 2017;33(1):72–9.10.1177/0266666916638712Search in Google Scholar

[67] Onduso R, Onono JO, Ombui JN. Assessment of structure and performance of cattle markets in western Kenya. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2020;52:725–32.10.1007/s11250-019-02062-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[68] Negi DS, Birthal PS, Roy D, Khan MT. Farmers’ choice of market channels and producer prices in India: role of transportation and communication networks. Food Policy. 2018;81:106–21.10.1016/j.foodpol.2018.10.008Search in Google Scholar

[69] Mugwisi T. Communicating agricultural information for development: the role of the media in Zimbabwe. Libri. 2015;65(4):281–99.10.1515/libri-2015-0094Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Ni Made Ari Kusuma Dewi et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The nutmeg seedlings growth under pot culture with biofertilizers inoculation

- Recovery of heather (Calluna vulgaris) flowering in northern Finland

- Soil microbiome of different-aged stages of self-restoration of ecosystems on the mining heaps of limestone quarry (Elizavetino, Leningrad region)

- Conversion of land use and household livelihoods in Vietnam: A study in Nghe An

- Foliar selenium application for improving drought tolerance of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.)

- Assessment of deficit irrigation efficiency. Case study: Middle Sebou and Innaouene downstream

- Integrated weed management practices and sustainable food production among farmers in Kwara State, Nigeria

- Determination of morphological changes using gamma irradiation technology on capsicum specie varieties

- Use of maturity traits to identify optimal harvestable maturity of banana Musa AAB cv. “Embul” in dry zone of Sri Lanka

- Theory vs practice: Patterns of the ASEAN-10 agri-food trade

- Intake, nutrient digestibility, nitrogen, and mineral balance of water-restricted Xhosa goats supplemented with vitamin C

- Physicochemical properties of South African prickly pear fruit and peel: Extraction and characterisation of pectin from the peel

- An evaluation of permanent crops: Evidence from the “Plant the Future” project, Georgia

- Probing of the genetic components of seedling emergence traits as selection indices, and correlation with grain yield characteristics of some tropical maize varieties

- Increase in the antioxidant content in biscuits by infusions or Prosopis chilensis pod flour

- Altitude, shading, and management intensity effect on Arabica coffee yields in Aceh, Indonesia

- Climate change adaptation and cocoa farm rehabilitation behaviour in Ahafo Ano North District of Ashanti region, Ghana

- Effect of light spectrum on growth, development, and mineral contents of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L.)

- An assessment of broiler value chain in Nigeria

- Storage root yield and sweetness level selection for new honey sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas [L.] Lam)

- Direct financial cost of weed control in smallholder rubber plantations

- Combined application of poultry litter biochar and NPK fertilizer improves cabbage yield and soil chemical properties

- How does willingness and ability to pay of palm oil smallholders affect their willingness to participate in Indonesian sustainable palm oil certification? Empirical evidence from North Sumatra

- Investigation of the adhesion performance of some fast-growing wood species based on their wettability

- The choice of information sources and marketing channel of Bali cattle farmers in Bali Province

- Preliminary phytochemical screening and in vitro antibacterial activity of Plumbago indica (Laal chitrak) root extracts against drug-resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae

- Agronomic and economic performance of maize (Zea mays L.) as influenced by seed bed configuration and weed control treatments

- Selection and characterization of siderophores of pathogenic Escherichia coli intestinal and extraintestinal isolates

- Effectiveness of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L.) living mulch on weed suppression and yield of maize (Zea mays L.)

- Cow milk and its dairy products ameliorate bone toxicity in the Coragen-induced rat model

- The motives of South African farmers for offering agri-tourism

- Morphophysiological changes and reactive oxygen species metabolism in Corchorus olitorius L. under different abiotic stresses

- Nanocomposite coatings for hatching eggs and table eggs

- Climate change stressors affecting household food security among Kimandi-Wanyaga smallholder farmers in Murang’a County, Kenya

- Genetic diversity of Omani barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) germplasm

- Productivity and profitability of organic and conventional potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) production in West-Central Bhutan

- Response of watermelon growth, yield, and quality to plant density and variety in Northwest Ethiopia

- Sex allocation and field population sex ratio of Apanteles taragamae Viereck (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), a larval parasitoid of the cucumber moth Diaphania indica Saunders (Lepidoptera: Crambidae)

- Comparison of total nutrient recovery in aquaponics and conventional aquaculture systems

- Relationships between soil salinity and economic dynamics: Main highlights from literature

- Effects of soil amendments on selected soil chemical properties and productivity of tef (Eragrostis tef [Zucc.] Trotter) in the highlands of northwest Ethiopia

- Influence of integrated soil fertilization on the productivity and economic return of garlic (Allium sativum L.) and soil fertility in northwest Ethiopian highlands

- Physiological and biochemical responses of onion plants to deficit irrigation and humic acid application

- The incorporation of Moringa oleifera leaves powder in mutton patties: Influence on nutritional value, technological quality, and sensory acceptability

- Response of biomass, grain production, and sugar content of four sorghum plant varieties (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) to different plant densities

- Assessment of potentials of Moringa oleifera seed oil in enhancing the frying quality of soybean oil

- Influences of spacing on yield and root size of carrot (Daucus carota L.) under ridge-furrow production

- Review Articles

- A review of upgradation of energy-efficient sustainable commercial greenhouses in Middle East climatic conditions

- Plantago lanceolata – An overview of its agronomically and healing valuable features

- Special Issue on CERNAS 2020

- The role of edible insects to mitigate challenges for sustainability

- Morphology and structure of acorn starches isolated by enzymatic and alkaline methods

- Evaluation of FT-Raman and FTIR-ATR spectroscopy for the quality evaluation of Lavandula spp. Honey

- Factors affecting eating habits and knowledge of edible flowers in different countries

- Ideal pH for the adsorption of metal ions Cr6+, Ni2+, Pb2+ in aqueous solution with different adsorbent materials

- Determination of drying kinetics, specific energy consumption, shrinkage, and colour properties of pomegranate arils submitted to microwave and convective drying

- Eating habits and food literacy: Study involving a sample of Portuguese adolescents

- Characterization of dairy sheep farms in the Serra da Estrela PDO region

- Development and characterization of healthy gummy jellies containing natural fruits

- Agro-ecological services delivered by legume cover crops grown in succession with grain corn crops in the Mediterranean region

- Special issue on CERNAS 2020: Message from the Editor

- Special Issue on ICESAT 2019

- Climate field schools to increase farmers’ adaptive capacity to climate change in the southern coastline of Java

- Special Issue on the International Conference on Agribusiness and Rural Development - IConARD 2020

- Supply chain efficiency of red chili based on the performance measurement system in Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Sustainable value of rice farm based on economic efficiency in Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Enhancing the performance of conventional coffee beans drying with low-temperature geothermal energy by applying HPHE: An experimental study

- Opportunities of using Spirulina platensis as homemade natural dyes for textiles

- Special Issue on the APA 2019 - 11th Triennial Conference

- Expanding industrial uses of sweetpotato for food security and poverty alleviation

- A survey on potato productivity, cultivation and management constraints in Mbala district of Northern Zambia

- Orange-fleshed sweetpotato: Strategies and lessons learned for achieving food security and health at scale in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Growth and yield of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) as affected by storage conditions and storage duration in Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria

- Special Issue on the International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research - Agrarian Sciences

- Application of nanotechnologies along the food supply chain

- Special Issue on Agriculture, Climate Change, Information Technology, Food and Animal (ACIFAS 2020)

- The use of endophytic growth-promoting bacteria to alleviate salinity impact and enhance the chlorophyll, N uptake, and growth of rice seedling

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The nutmeg seedlings growth under pot culture with biofertilizers inoculation

- Recovery of heather (Calluna vulgaris) flowering in northern Finland

- Soil microbiome of different-aged stages of self-restoration of ecosystems on the mining heaps of limestone quarry (Elizavetino, Leningrad region)

- Conversion of land use and household livelihoods in Vietnam: A study in Nghe An

- Foliar selenium application for improving drought tolerance of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.)

- Assessment of deficit irrigation efficiency. Case study: Middle Sebou and Innaouene downstream

- Integrated weed management practices and sustainable food production among farmers in Kwara State, Nigeria

- Determination of morphological changes using gamma irradiation technology on capsicum specie varieties

- Use of maturity traits to identify optimal harvestable maturity of banana Musa AAB cv. “Embul” in dry zone of Sri Lanka

- Theory vs practice: Patterns of the ASEAN-10 agri-food trade

- Intake, nutrient digestibility, nitrogen, and mineral balance of water-restricted Xhosa goats supplemented with vitamin C

- Physicochemical properties of South African prickly pear fruit and peel: Extraction and characterisation of pectin from the peel

- An evaluation of permanent crops: Evidence from the “Plant the Future” project, Georgia

- Probing of the genetic components of seedling emergence traits as selection indices, and correlation with grain yield characteristics of some tropical maize varieties

- Increase in the antioxidant content in biscuits by infusions or Prosopis chilensis pod flour

- Altitude, shading, and management intensity effect on Arabica coffee yields in Aceh, Indonesia

- Climate change adaptation and cocoa farm rehabilitation behaviour in Ahafo Ano North District of Ashanti region, Ghana

- Effect of light spectrum on growth, development, and mineral contents of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L.)

- An assessment of broiler value chain in Nigeria

- Storage root yield and sweetness level selection for new honey sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas [L.] Lam)

- Direct financial cost of weed control in smallholder rubber plantations

- Combined application of poultry litter biochar and NPK fertilizer improves cabbage yield and soil chemical properties

- How does willingness and ability to pay of palm oil smallholders affect their willingness to participate in Indonesian sustainable palm oil certification? Empirical evidence from North Sumatra

- Investigation of the adhesion performance of some fast-growing wood species based on their wettability

- The choice of information sources and marketing channel of Bali cattle farmers in Bali Province

- Preliminary phytochemical screening and in vitro antibacterial activity of Plumbago indica (Laal chitrak) root extracts against drug-resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae

- Agronomic and economic performance of maize (Zea mays L.) as influenced by seed bed configuration and weed control treatments

- Selection and characterization of siderophores of pathogenic Escherichia coli intestinal and extraintestinal isolates

- Effectiveness of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L.) living mulch on weed suppression and yield of maize (Zea mays L.)

- Cow milk and its dairy products ameliorate bone toxicity in the Coragen-induced rat model

- The motives of South African farmers for offering agri-tourism

- Morphophysiological changes and reactive oxygen species metabolism in Corchorus olitorius L. under different abiotic stresses

- Nanocomposite coatings for hatching eggs and table eggs

- Climate change stressors affecting household food security among Kimandi-Wanyaga smallholder farmers in Murang’a County, Kenya

- Genetic diversity of Omani barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) germplasm

- Productivity and profitability of organic and conventional potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) production in West-Central Bhutan

- Response of watermelon growth, yield, and quality to plant density and variety in Northwest Ethiopia

- Sex allocation and field population sex ratio of Apanteles taragamae Viereck (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), a larval parasitoid of the cucumber moth Diaphania indica Saunders (Lepidoptera: Crambidae)

- Comparison of total nutrient recovery in aquaponics and conventional aquaculture systems

- Relationships between soil salinity and economic dynamics: Main highlights from literature

- Effects of soil amendments on selected soil chemical properties and productivity of tef (Eragrostis tef [Zucc.] Trotter) in the highlands of northwest Ethiopia

- Influence of integrated soil fertilization on the productivity and economic return of garlic (Allium sativum L.) and soil fertility in northwest Ethiopian highlands

- Physiological and biochemical responses of onion plants to deficit irrigation and humic acid application

- The incorporation of Moringa oleifera leaves powder in mutton patties: Influence on nutritional value, technological quality, and sensory acceptability

- Response of biomass, grain production, and sugar content of four sorghum plant varieties (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) to different plant densities

- Assessment of potentials of Moringa oleifera seed oil in enhancing the frying quality of soybean oil

- Influences of spacing on yield and root size of carrot (Daucus carota L.) under ridge-furrow production

- Review Articles

- A review of upgradation of energy-efficient sustainable commercial greenhouses in Middle East climatic conditions

- Plantago lanceolata – An overview of its agronomically and healing valuable features

- Special Issue on CERNAS 2020

- The role of edible insects to mitigate challenges for sustainability

- Morphology and structure of acorn starches isolated by enzymatic and alkaline methods

- Evaluation of FT-Raman and FTIR-ATR spectroscopy for the quality evaluation of Lavandula spp. Honey

- Factors affecting eating habits and knowledge of edible flowers in different countries

- Ideal pH for the adsorption of metal ions Cr6+, Ni2+, Pb2+ in aqueous solution with different adsorbent materials

- Determination of drying kinetics, specific energy consumption, shrinkage, and colour properties of pomegranate arils submitted to microwave and convective drying

- Eating habits and food literacy: Study involving a sample of Portuguese adolescents

- Characterization of dairy sheep farms in the Serra da Estrela PDO region

- Development and characterization of healthy gummy jellies containing natural fruits

- Agro-ecological services delivered by legume cover crops grown in succession with grain corn crops in the Mediterranean region

- Special issue on CERNAS 2020: Message from the Editor

- Special Issue on ICESAT 2019

- Climate field schools to increase farmers’ adaptive capacity to climate change in the southern coastline of Java

- Special Issue on the International Conference on Agribusiness and Rural Development - IConARD 2020

- Supply chain efficiency of red chili based on the performance measurement system in Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Sustainable value of rice farm based on economic efficiency in Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Enhancing the performance of conventional coffee beans drying with low-temperature geothermal energy by applying HPHE: An experimental study

- Opportunities of using Spirulina platensis as homemade natural dyes for textiles

- Special Issue on the APA 2019 - 11th Triennial Conference

- Expanding industrial uses of sweetpotato for food security and poverty alleviation

- A survey on potato productivity, cultivation and management constraints in Mbala district of Northern Zambia

- Orange-fleshed sweetpotato: Strategies and lessons learned for achieving food security and health at scale in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Growth and yield of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) as affected by storage conditions and storage duration in Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria

- Special Issue on the International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research - Agrarian Sciences

- Application of nanotechnologies along the food supply chain

- Special Issue on Agriculture, Climate Change, Information Technology, Food and Animal (ACIFAS 2020)

- The use of endophytic growth-promoting bacteria to alleviate salinity impact and enhance the chlorophyll, N uptake, and growth of rice seedling