Abstract

Nowadays there is an increasing demand for healthy biscuits. The reduction in sugar and fat level, as well as the addition of bioactive compounds, is positively associated with a healthy diet. In the present work, low-fat and low-sugar biscuits were prepared with infusions (mate, coffee, and tea) or with Prosopis chilensis pod flour (PPF). Biscuits were made with maize starch and wheat flour (gluten formulations) or with gluten-free ingredients (gluten-free). The colour, texture, and the antioxidant capacity were evaluated in dough and biscuits. Among the formulations prepared with infusions, the mate dough showed the lowest firmness (1.1 N (gluten)-24.3 N (gluten-free)). However, no significant differences were found in the fracture stress of the final products (P > 0.05). Mate gluten biscuits and PPF gluten-free biscuits showed the highest fracture strain (16.2 and 9.4%, respectively) and the lowest Young’s modulus (7.3 and 13.3 MPa, respectively) in their groups. The highest antioxidant activity was found in biscuits with mate (8.7 µmol FeSO4/g (gluten)-4.3 µmol FeSO4/g (gluten-free)). These values were three times higher than the ones found in the control biscuits (2.9 µmol FeSO4/g (gluten)-3.9 µmol FeSO4/g (gluten-free)). The present results showed that the antioxidant content in biscuits could be successfully increased with infusion addition.

1 Introduction

Biscuits are one of the best-selling food products in many countries. They have a long shelf life and, because a wide variety of ingredients can be incorporated into their formulation, they can be a useful tool to improve the nutritional quality in the consumer’s diet (Guiné et al. 2020). Nonetheless, biscuits generally contain high fat levels often more than 30% and a high sugar amount rarely less than 40%; therefore, they are not considered as healthy food.

The development of healthy biscuits can include the reduction in their sugar or fat levels and the incorporation of different bioactive components. Some authors made healthy biscuits through the incorporation of composite flours (Saha et al. 2011; Chandra et al. 2015; Dhankhar et al. 2019), fibre (Brennan and Samyue 2004; Aboshora et al. 2019; Diez-Sánchez et al. 2019), resistant starch (Aparicio-Saguilán et al. 2007; Laguna et al. 2011), natural and artificial sweeteners (Mosafa et al. 2017; Nakov et al. 2019), fruits (Pathak et al. 2018), spices (Klunklin and Savage 2018; Sandhya and Waghray 2018), or fat replacers (Colla et al. 2018).

On the contrary, the increase in the number of celiac patients increases the demand of gluten-free food. Although hydrocolloids or other additives are generally used to improve the physical characteristics of these food products, they may reduce the consumer’s acceptance. Moreover, gluten-free products present a high proportion of carbohydrates but they are deficient in protein, fibre, minerals, and vitamins (Saturni et al. 2010; Koidis 2016). Thus, the addition of ingredients that provide all the nutrients necessary to maintain a balanced diet and, at the same time, reduce the fat and the sugar content of gluten-free products is a matter of striking significance.

Various flours and starches have been studied as ingredients to replace wheat flour in gluten-free foods. Algarrobo pod flour or Mesquite flour is a gluten-free flour obtained from the grinding of the whole mature fruit (pod) of algarrobo trees (Prosopis spp.). These species are widely distributed in a large part of the South American territory, and it is a great food resource for humans and animals in arid and semi-arid regions of the world. Algarrobo pod flour is used for various purposes: food, wood, fodder, and also some ethnohistorical references have indicated their consumption by local indigenous people (Capparelli 2007; Capparelli and Prates 2015). Moreover, previous authors have indicated that algarrobo pod flour presents a high proportion of simple sugars and fibre, and also contains a significant amount of minerals, vitamins, and polyphenols with high antioxidant activity (Cardozo et al. 2010; Sciammaro et al. 2016; Gonzales-Barron et al. 2020).

It is well known that there is a positive correlation between food and health. Dietary guidelines worldwide recommend to increase the consumption of fruits and vegetables. These foodstuffs are rich sources of antioxidant and dietary fibre that could reduce the risk of human diseases such as cancer, atherosclerosis, heart diseases, osteoporosis, and obesity. Biscuits are often stored for extended periods; thus, antioxidant agents are one of the most used additives in the food industry. Natural antioxidants are generally preferred to potentially toxic, synthetic substances. Thus, several authors have studied the addition of natural antioxidant in biscuits with excellent results (Reddy et al. 2005; Mildner‐Szkudlarz et al. 2009; Caleja et al. 2017). Furthermore, antioxidants can protect the body from oxygen radical-induced damage.

Infusions are natural aqueous extracts with high antioxidant content. Coffee (Coffea arabica) and tea (Camellia sinensis) are widely consumed beverages, and they are rich in bioactive phytochemicals such as chlorogenic acids, polyphenols, alkaloids, and melanoidins (Rodrigues and Bragagnolo 2013; Iriondo-DeHond et al. 2019). Mate is an ancestral beverage consumed in several South American countries made from dried leaves of Ilex paraguariensis. Mate contains high levels of chlorogenic acids (Meinhart et al. 2018), saponins, purine alkaloids (Bracesco et al. 2011) vitamins, minerals, and several amino acids (Da Silva et al. 2008). Previous research has indicated the beneficial effects of mate consumption (Heck and Mejia 2007; Bracesco et al. 2011; Riachi and De Maria 2017; Gómez-Juaristi et al. 2018). Moreover, because of the long history of safe usage of these infusions and their high content of antioxidant substances, their addition into biscuit formulation is of particular interest to increase their nutritional value.

It is well known that the proportion of fat and sugar strongly influences the machinability of the dough as well as the quality of the finished product (Maache-Rezzoug et al. 1998; Baltsavias et al. 1999; Rodríguez-García et al. 2013). The fat acts as lubricant and contributes to dough plasticity, whereas the sugar contributes to volume, colour, tenderness, sweetness, and also acts as preservative (Mamat et al. 2010). The reduction in sugar and fat content in biscuits results in structural, textural, sensory, and hedonic consequences (Pareyt et al. 2009). Accordingly, the production of healthy low-fat and low-sugar biscuits enriched with natural antioxidants could be a worthwhile alternative to increase the amount of antioxidant in the diet. Besides, this may also be an attractive option for consumers who are increasingly concerned about the choice of healthy foods. However, the addition of new ingredients into biscuit formulations may adversely affect the viscoelastic properties of dough and the quality of the final products. Therefore, any modification of the formulation must be thoroughly evaluated.

Thus, the aim of this article was to verify that (1) healthy additive‐free low-fat and low-sugar biscuits with or without gluten can be made with a delicate texture by an appropriate selection of blends of different ingredients (flours and starches), and (2) the addition of infusions or algarrobo flour into biscuits could improve their antioxidant content without affecting their quality.

2 Materials and methods

Prosopis chilensis pod flour (PPF) (9.0% proteins, 4.6% lipids, 74% carbohydrates, 7.2% moisture, and 4.50% ash) was prepared by grinding whole pods of Prosopis chilensis. Other ingredients were purchased in a local market, such as wheat flour (ash content less than 0.65%, 10.1% protein, 14.7% moisture), rice flour (6% proteins, 1.2% lipids, 80% carbohydrates, and 2.4% fibre), chickpea flour (16% proteins, 9% lipids, 45% carbohydrates, and 15% fibre), cassava starch, maize starch, high oleic sunflower oil (Cañuelas, Argentina), sucrose, baking powder, vanilla, cocoa powder, black tea (La Virginia, Argentina), green tea (La Virginia, Argentina), yerba mate (Unión, Argentina), and coffee (La Morenita, Argentina). The chemical reagents were of analytical grade.

2.1 Selection of biscuit formulation by sensorial analysis

Dough was prepared with a kneading machine (Phillipp Cucina, Brazil) using a dough hook attachment at medium speed (837 rpm). First, the oil and the sugar were creamed during 30 s; then, the infusions or the water and vanilla essence were added and mixed for 90 s. Finally, the mix of flour, starches, and baking powder was added and mixed for 120 s.

Dough was set into a polypropylene bag and held at 4°C for 30 min before it was extended with a rolling pin to give a thickness of 0.3 cm. Circular pieces of dough of 2.5 cm in diameter were cut and placed on a silicon sheet. The dough pieces were baked in an oven (Ariston type F9M, Italy) at 175°C with forced convection at different baking times.

To evaluate whether the addition of infusions (5%) could cause aromas, colours, or flavours perceived by consumers, two sensory tests were run. These assays were also used to optimize the proportion of ingredients that allowed the best texture in the low-fat and low-sugar biscuit. A total of 24 untrained panellists evaluated the colour, the texture, the aroma, the taste, and the global acceptance of four biscuits coded with random digits on a hedonic scale (1 = dislike and 10 = like very much).

The first sensory test was performed with gluten biscuit formulations made with four blends of wheat flour and maize starch (WF:MS) (100.0 g): 20.0 g of sugar, 8.0 g of high oleic sunflower oil, 1.0 g of vanilla essence, 1.0 g of baking powder, and 46.0 g of tap water. In three formulations, 30.0 g of water was replaced by 5% infusions (mate, coffee, and tea). Biscuits were baked for 22 min.

The second sensory test was made with four gluten-free blends with rice flour, cassava starch, maize starch, and chickpea flour (RF:CS:MS:CF) (100.0 g): 5.0 g sugar and 5.0 g PPF, 1.0 g of vanilla essence, 2.0 g of baking powder, and 35.0 g of tap water. In three of them, 30.0 g water was replaced by 5% infusions (mate, coffee, and tea). Biscuits were baked for 18 min.

Then, two new batches of biscuits were prepared using the formulations selected in the sensory tests: a control formulation (with water), formulations with 5% infusions (mate, coffee, black, or green tea), and one prepared with a mix of sugar and PPF (1:1). Gluten samples (formulated with a WF:MS mixture) were prepared with 46 g of tap water, while gluten-free samples (prepared with the RF:CS:MS:CF mixture) with 35 g. When PPF was added into formulations, a slightly higher amount of water was necessary to add (12 mL). Six rectangular pieces (5.0 × 2.5 × 0.3 cm) of gluten or gluten-free biscuit formulations were baked at 175°C during 32 min or 22 min, respectively.

2.2 Infusions’ preparation

Coffee, black or green tea, and yerba mate infusions were prepared (5% w/v) with warm tap water (60°C) in a thermostatic bath during 15 min. Then, the extracts were cooled at room temperature before their use. The pH of infusions was determined using a Mettler Toledo meter (SevenMulti, China) at 25°C.

2.3 Dough and biscuits characterization

Texture profile analysis (TPA) was performed with a texture analyser (TA-XT2i, Stable Micro Systems Ltd, England). The dough samples with a 2.0 cm diameter and 1 cm height were compressed and decompressed during two penetration cycles. Compression was exerted by a 7.5 cm diameter cylindrical probe with a test speed of 0.5 mm/s and with a 50 kg load cell. The strain was set at 50% and 30 s between cycles. Firmness (N), consistency (N s), adhesiveness (N s), springiness, and cohesiveness were calculated from the TPA plot (Gómez et al. 2007). The pH of dough was measured with an electrode for solid samples.

The fracture properties of the rectangular biscuits were studied by a three-point bending test performed with a TA.XT2 Texture Analyser (Stable Micro Systems Ltd, England), with trigger force of 25 g and load cell of 50 kg. Span length (L) was 1.7 cm, and compression speed was set at 0.1 mm/s. Samples were placed on supports with their top surface down. The large, width (d), and thickness (b) of the baked products were measured using a Vernier calliper. The force (F) needed to break the biscuit (N), the toughness or breaking work (N s), the deformation (y) before rupture (mm), and the slope (s) of force–distance curve (N mm) were determined. Texture of rectangular biscuits was expressed according to size-independent parameters (Baltsavias et al. 1999), and the fracture stress (σ, equation (1)), the fracture strain (ε, equation (2)), and the Young’s modulus (E, equation (3)) were calculated as follows:

The texture was measured 24 h after baking (to minimize the impact of moisture gradients in the baked product during cooling) with at least five different biscuits of each formulation. The water activity of biscuits was measured with AquaLab Serie3 (Decagon Devices, Inc., Pullman, WA; at 25°C) in duplicate. Besides, the moisture content was also determined in duplicate (AOAC 1984).

The surface colour of at least five samples (dough and biscuits) was measured using a Chroma meter CR-400 (Osaka, Japan) with D65 illuminant, 10° angle of vision. The colorimeter was calibrated using a standard white plate. The Hunter parameters L* (L* = 0 [black], L* = 100 [white]), a* (−a* = green, +a* = red), and b* (−b* = blue, +b* = yellow) were determined. Moreover, the whiteness index (WI, equation (4)) (Zucco et al. 2011) and the colour difference (ΔE, equation (5)) between samples and the control biscuits (note with o) were calculated as follows:

2.4 Extraction of antioxidant from dough and biscuits

The extraction of antioxidants was carried out in duplicate on ground and sieve samples (<500 µm) of biscuits, dough, and in some ingredients with a high proportion of bioactive compounds. The extraction was performed with warm water as described by Morales et al. (2009) with slight modifications. Briefly, 0.2 g of samples was weighed and extracted with 1.5 mL of distilled water (45°C) by stirring for 5 min (orbital shaker MS1, IKA, Brasil). Then, after 30 min of resting time at 4°C, samples were centrifuged for 10 min (Giumelli Z-127-D Centrifuge, Argentina). The residue was extracted one more time with 1 mL of warm water and centrifuged in the same conditions. Finally, the two aqueous extracts of each sample were combined and stored at −18°C before use.

2.5 Ferric reducing antioxidant power

The ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) of the samples was determined as described by Benzie and Strain (1996). Briefly, 0.2 mL of each extract was mixed with 1.8 mL of fresh prepared FRAP reagent and kept in the dark for 20 min. The absorbance was measured at 593 nm (UVmin-1240 spectrophotometer, Shimatdzu, Jenck S.A., Kyoto, Japan) in clear samples. A calibration curve was made with ferrous sulphate (FeSO4·7H2O) within the range of 0–1,000 μM. The FRAP of the samples was expressed as µmol FeSO4 per g of dried sample (biscuits, dough, or dried ingredients) or µmol FeSO4 per mL in infusion samples.

2.6 Data analysis

Data were statistically evaluated by analysis of variance (ANOVA) at a 0.05 significance level. The least significant differences (LSD) were calculated to compare the means at a level of 95% using the Fisher’s test.

Non-parametric statistical tests were used when the variables did not comply with the assumption of homogeneity of variance. As recommended by García‐Gómez et al. (2019), the differences in the sensory characteristics (colour, texture, taste, aroma, and global acceptance) were studied using Friedman’s test at 95% level of confidence.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Selected formulation from sensorial analysis

The low-fat and low-sugar biscuits could be classified as semisweet biscuits according to Manley’s classification (Manley 1998). The colour of the biscuits, the first characteristic that the consumers perceive and together with texture and taste, strongly affects the acceptability of the product. Data of colour, texture, and the sensory test of biscuits made with different ingredients are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Colour (whiteness index), texture (toughness), and results of the sensory test of biscuits prepared with wheat flour (WF) and maize starch (MS) of blends and with infusion addition

| WF:MS blend ratio | Infusion | Whiteness index | Toughness (N s) | Sensory test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colour | Aroma | Texture | Taste | Global acceptance | ||||

| 55:45 | Mate | 69.8c | 196.2a | 59.0ab | 58.5a | 77.0b | 73.0b | 74.0b |

| 62:38 | Coffee | 64.3a | 263.4a | 72.0b | 65.5a | 57.0a | 64.5ab | 63.0ab |

| 69:31 | Tea | 65.4ab | 380.4ab | 54.0a | 60.5a | 50.5a | 50.0a | 51.0a |

| 77:23 | — | 66.1b | 625.1b | 55.0a | 55.5a | 55.5a | 52.5a | 52.0a |

Means with different superscripts within the same column are significantly different (P < 0.05).

Colour (whiteness index), texture (toughness), and results of the sensory test of gluten-free biscuits prepared from four blends of rice flour (RF), cassava starch (CS), maize starch (MS), and chickpea flour (CF) with infusions

| RF:CS:MS:CF blend ratio | Infusion | Whiteness index | Toughness (N s) | Sensory test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colour | Aroma | Texture | Taste | Global acceptance | ||||

| 25:25:25:25 | Mate | 57.2c | 42.8a | 67.0a | 64.5a | 64.5a | 71.0a | 67.0a |

| 38:12:12:38 | Tea | 54.4b | 53.2a | 60.0a | 57.0a | 55.0a | 56.5a | 58.5a |

| 50:12:12:26 | Coffee | 56.0bc | 46.1a | 65.5a | 63.5a | 57.0a | 54.5a | 59.5a |

| 26:12:12:50 | — | 48.1a | 96.1b | 47.5a | 55.0a | 63.5a | 58.0a | 55.0a |

Means with different superscripts within the same column are significantly different (P < 0.05).

As presented in Table 1, a wide range of toughness values (196.2–625.1 N s) could be obtained from different wheat flour and maize blend composition. Biscuits made with 55:45 (WF:MS) with mate were preferred by panellist in texture, taste, and global acceptance (P < 0.05). These samples showed the highest whiteness index (69.8) and a tender texture (low toughness, 196.2 N s)

On the contrary, the colour, the texture, and the sensory characteristics of gluten-free samples were also studied. According to the results presented in Table 2, no significant differences were found between samples in the sensory test (P > 0.05). The highest toughness value (96.1 N s) and the lowest whiteness index (48.1) were registered in 26:12:12:50 (RF:CS:MS:CF) blend biscuits with high content of chickpea flour (P < 0.05). Thus, the formulation 25:25:25:25 (RF:MS:CS:CF) was selected because it presented the highest scores in texture and global acceptance, besides it had a low value of toughness according to the bending test.

Results showed that all gluten-free biscuits showed lower WI values than gluten samples because of the colour of CF (88.60L*, −0.48a*, 22.86b*) and PPF (74.96L*, 3.87a*, 28.65b*) (Table 2).

It should be highlighted that in both sensory tests, biscuits made with a high starch proportion were preferred by the panellists. Besides, among the formulations with infusion additions, biscuits made with mate received the highest taste score.

3.2 Infusion preparation

Previous authors studied the effect of infusion preparation conditions and its antioxidant content (Richelle et al. 2001; Sánchez-González et al. 2005; da Silveira et al. 2014). Mate extracts contain purine alkaloids (methyl xanthines), flavonoids (rutin), vitamins (such as vitamin A, B complex, C, and E), tannins, chlorogenic acid and its derivatives, and numerous triterpenoid saponins derived from ursolic acid (Bracesco et al. 2011). Green tea is made by inactivating the enzymes in the fresh leaves, and it contains flavonoids derivatives of catechins (monomers), whereas black tea contains more complex polyphenols (dimers and polymers) (Wang and Ho 2009). Coffee contains phenolic compounds such as chlorogenic acids, caffeine, and diterpenic compounds (Yashin et al. 2017).

Generally, coffee and tea are prepared with very hot water (90–95°C), while mate is prepared at 60–85°C. In this study, all infusions were prepared with tap water at 60°C. Mate infusion had pH 6.30, coffee pH 5.62, green tea pH 5.71, and black tea pH 5.17. The pH value measured in the coffee infusion is within the range of 5–5.8 reported by Derossi et al. (2018).

3.3 Dough characterization

Results of colour and dough texture of gluten samples are presented in Tables 3 and 4. In both the tables, the highest whiteness index was found in the control samples (P < 0.05), while the highest colour difference was observed in the coffee samples (P < 0.05). The colour differences between samples and control dough were less in the gluten-free samples because of the colour of the chickpea flour. The addition of mate infusion increased the pH of the dough, whereas with other infusions or with PPF addition, the values were lower than the control.

Physical characteristics of dough and biscuits prepared from 55:45 wheat flour:maize starch blend flour with infusions or with Prosopis chilensis pod flour (PPF)

| Control | Coffee | Mate | Green tea | PPF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firmness (N) | 1.5b | 1.3ab | 1.1a | 1.4b | 4.8c |

| Consistency (N s) | 8.4b | 8.4b | 7.0a | 8.5b | 32.1c |

| Cohesiveness | 1.1b | 1.2b | 1.4c | 1.1b | 0.3a |

| Springiness | 0.98a | 0.98a | 0.98a | 0.98a | 0.98a |

| Whiteness index, WI | 74.1d | 59.4a | 66.4b | 68.9c | 67.0b |

| Colour differences, ΔE | — | 15.4c | 11.3b | 9.9a | 10.2a |

| pH | 6.56 | 6.41 | 6.73 | 6.62 | 6.40 |

Means with different superscripts within the same row are significantly different (P < 0.05).

Physical characteristics of gluten-free dough prepared from 25:25:25:25 rice flour:cassava starch:maize starch:chickpea flour blend with infusions or Prosopis chilensis pod flour (PPF)

| Control | Coffee | Mate | Black tea | PPF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dough | |||||

| Firmness (N) | 42.3d | 30.3b | 24.3a | 33.8c | 29.5b |

| Consistency (N s) | 212.2d | 156.6b | 129.6a | 181.9c | 162.3b |

| Cohesiveness | 0.100a | 0.113c | 0.105b | 0.101ab | 0.101ab |

| Adhesiveness (N s) | 2.2a | 4.0c | 3.9c | 3.0b | 2.3a |

| Springiness | 0.23b | 0.27b | 0.27b | 0.21ab | 0.15a |

| Whiteness index, WI | 64.7d | 58.5a | 61.9c | 61.3bc | 60.7b |

| Colour differences, ΔE | — | 6.9c | 3.0a | 3.6a | 4.8b |

| pH | 6.81 | 6.61 | 6.91 | 6.70 | 6.62 |

Means with different superscripts within the same row are significantly different (P < 0.05).

No significant differences were found between green tea, coffee, and control sample (Table 3). Mate sample shows the highest cohesiveness but also the lowest firmness and consistency values (P < 0.05). Except for the PPF dough, all samples were prepared using the same quantities of ingredients (water, sugar, oil, and proteins) but different infusions; therefore, the differences in dough texture and dough pH could be related to the composition of the aqueous extracts. The texture of the sample with PPF showed the lowest cohesiveness and the highest firmness and consistency values (P < 0.05). The replacement of sugar by PPF increases the amount of proteins and fibre in the formulation, and therefore, more water was required to obtain a homogeneous dough. Other authors reported a similar trend when replacing wheat flour with algarrobo flour (Bigne et al. 2016).

In Table 4, the control sample showed highest firmness and consistency values (P < 0.05), while the mate sample showed the lowest values. Adhesiveness of samples with infusion addition was higher than control formulations (P < 0.05). According to the results, it could be concluded that the replacement of half of sugar by PPF produced dough with less firmness, consistency, and springiness than control sample but with similar cohesiveness and adhesiveness values.

3.4 Quality properties of biscuits

Baking is a complex process, which includes evaporation of water, denaturation of proteins, starch gelatinization, and also Maillard reactions. Results of colour, humidity, dimensions, and fracture texture of biscuits are presented in Table 5 (gluten samples) and Table 6 (gluten-free samples). Although all the samples were baked simultaneously and had the same amount of ingredients (except for PPF), some unexpected differences were found in the moisture and water activity values. PPF samples showed a higher humidity and higher a w values than control samples, probably because they were prepared with a higher amount of water than the other formulations. In both tables, all the a w values were lower than 0.8; therefore, it could be considered that the pathogen growth would be inhibited (Mauer and Bradley 2017). Biscuits with lower thickness also showed lower values of a w and humidity and thus a crispy texture (high Young modulus values) (P < 0.05). However, no significant differences were found in the fracture stress (σ) values (P > 0.05), indicating that all biscuits had similar hardness. Finally, it was observed that the lowest colour difference was observed in the mate samples (Table 5).

Physical characteristics biscuits prepared from the 55:45 wheat flour:maize starch blend flour with infusions or with Prosopis chilensis pod flour (PPF)

| Control | Coffee | Mate | Green tea | PPF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fracture stress, σ (kPa) | 1.7a | 1.3a | 0.9a | 1.3a | 1.5a |

| Fracture strain, ε (%) | 5.0a | 8.2a | 16.2b | 7.9a | 6.8a |

| Young’s modulus, E (MPa) | 33.9c | 22.6bc | 7.3a | 17.8ab | 18.2ab |

| Thickness (mm) | 4.5a | 5.6ab | 6.7b | 5.6ab | 5.3b |

| Moisture content (%) | 6.7a | 8.7c | 11.2d | 7.9b | 9.0c |

| a w | 0.399a | 0.559b | 0.672c | 0.487ab | 0.529b |

| Whiteness index, WI | 68.5c | 57.0a | 68.2c | 61.8b | 56.7a |

| Colour differences, ΔE | — | 13.0b | 8.3a | 8.3a | 14.3b |

Means with different superscripts within the same row are significantly different (P < 0.05).

Physical characteristics of gluten-free biscuits prepared from 25:25:25:25 rice flour:cassava starch:maize starch:chickpea flour blend with infusions or Prosopis chilensis pod flour (PPF)

| Control | Coffee | Mate | Black tea | PPF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fracture stress, σ (kPa) | 0.8a | 1.1a | 0.9a | 1.1a | 1.2a |

| Fracture strain, ε (%) | 3.5a | 4.6ab | 6.5b | 4.9ab | 9.4c |

| Young’s modulus, E (MPa) | 18.8a | 37.6b | 17.2a | 27.7ab | 13.3a |

| Thickness (mm) | 5.0a | 4.6a | 4.9a | 5.0a | 5.2a |

| Moisture content (%) | 6.9ab | 6.1a | 9.8c | 7.7b | 11.1d |

| a w | 0.469a | 0.453a | 0.609c | 0.525b | 0.650d |

| Whiteness index, WI | 59.0c | 52.9a | 60.0c | 56.4b | 58.5c |

| Colour differences, ΔE | — | 7.7b | 3.1a | 5.5ab | 4.8ab |

Means with different superscripts within the same row are significantly different (P < 0.05).

The control biscuit (Table 5) showed the lowest values of thickness, a w and humidity, and the highest Young’s modulus values (which indicates a crispy texture) (P < 0.05). On the contrary, biscuits prepared with mate showed the highest fracture strain values (ε) and the lowest Young’s modulus (P < 0.05), indicating a tender texture. Other authors also found a reduction in the firmness texture with mate addition (Faccin et al. 2015). Mate biscuits also showed a significantly higher thickness, humidity, and a w values (P < 0.05). During baking, dough components (proteins, sugars, dietary fibre, and other high water affinity ingredients) are responsible for trapping water until it is released as a consequence of heating. Thus, differences in dough composition (extracts or PPF) produce that all biscuits retain more moisture than the control formulation. Regarding colour, coffee and PPF biscuits presented lower WI values and higher ΔE values than other biscuits (P < 0.05).

Results in Table 6 show that no significant differences were found in the thickness of gluten-free biscuits (P > 0.05). Coffee biscuits showed the highest Young’s modulus values (crispier texture) while samples with PPF showed the highest fracture strain (tender texture) (P < 0.05). The colour analysis indicated that mate and PPF biscuits presented higher WI values and lower ΔE values than coffee and tea biscuits (P < 0.05).

It was observed that despite the differences in the texture of the dough with infusions or with PPF (Tables 3 and 4), there were no important differences in the texture of biscuits (Tables 5 and 6).

3.5 Ferric reducing antioxidant power

There are many different antioxidants, and it is very difficult to measure each antioxidant component separately. In this study, the FRAP assay was selected because it is simple, and the reaction is reproducible and linearly related to the concentration of the antioxidant(s) present. In the present study, antioxidants were extracted under the same conditions (warm water) and analysed together with the dough and the biscuits samples by FRAP assay so that the results could be compared. The values found for these ingredients were (µmol FeSO4/g): 80.4 Moringa oleifera leaf powder; 1.9 dried cranberries (Vaccinium macrocarpon); 9.8 raisins (Vitis vinifera L.); and 5.5 dried plums (Prunus domestica).

Results of FRAP assay are presented in Table 7. Antioxidant capacity of dough depends on the amount of antioxidants added with ingredients. During baking, the outer layers of the dough are heated to 170°C, but in the inner layers, the temperature remains lower than 100°C. Decomposition of antioxidant during baking is partially compensated by the formation of Maillard products (melanoidins) which also possess antioxidant activity (Patrignani et al. 2021). Only samples made with PPF and with black tea showed a higher antioxidant activity in biscuits than dough. PPF and all infusions are shown higher FRAP values than control samples. The antioxidant activity of samples made with PPF or mate and green tea infusions was higher than samples made with coffee and black tea infusions. The same trend was observed between the antioxidant content of the ingredients. All ingredients showed a higher antioxidant activity than dried cranberries and dried plumbs. The antioxidant capacity of mate samples (8.1 (WF:MS) – 3.9 (RF:CS:MS:CF) was three times greater than the control dough samples (2.2 (WF:MS) – 1.3 (RF:CS:MS:CF)) and almost double in biscuits samples (P < 0.05). This is in accordance with the higher antioxidant activity of mate compared to tea infusions reported by other authors (Bravo et al. 2007; Heck and Mejia 2007; da Silveira et al. 2014). No differences were found between the antioxidant activity of coffee and PPF dough samples, but in biscuits, PPF showed higher values than coffee biscuits.

FRAP results in samples prepared with 55:45 wheat flour:maize starch (WF:MS) blend or with 25:25:25:25 rice flour:cassava starch:maize starch:chickpea flour (RF:CS:MS:CF) blend with infusions or Prosopis chilensis pod flour (PPF)*

| Control | Coffee | Mate | Black tea | Green tea | PPF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ingredients | — | 8.8* | 12.1* | 7.8* | 12.8* | 18.6 | |

| 55:45 (WF:MS) | Dough | 2.0a | 4.4b | 8.1d | — | 5.7c | 4.4b |

| Biscuit | 2.9a | 4.5b | 8.7d | — | 5.1bc | 5.6c | |

| 25:25:25:25 (RF:CS:MS:CF) | Dough | 1.3a | 3.3c | 3.9d | 2.0b | — | 3.0c |

| Biscuit | 1.8a | 3.3b | 4.3e | 3.1b | — | 3.8c | |

Means with different superscripts within the same row are significantly different (P < 0.05).

- *

Results are expressed as µmol FeSO4/g solid samples or µmol FeSO4/mL in liquid ingredients.

The sensorial test showed that the incorporation of the infusions at 5% level did not cause significant changes in appearance (aroma or colour) perceived by consumers, and it could be considered a positive aspect to keep the traditional aspect of the biscuits.

4 Conclusions

Biscuits are products worldwide appreciated and consumed by different categories of consumers, child, young, and adults. Therefore, the reduced sugar and fat content could have a great impact on health. Low-fat and low-sugar biscuits enriched with natural sources of antioxidants may be attractive for consumers who are increasingly concerned about the choice of healthy foods. Algarrobo pod flour could be obtained at home, with a simple ground process, and it is a gluten-free ingredient that could be used as a partial sugar replacer.

The use of infusions is an environment-friendly process to obtain natural food additives. This study revealed that both the use of infusions (aqueous extracts of coffee, tea, and mate) and the use of PPF as biscuit ingredients allowed to obtain products with a high antioxidant activity. The infusion preparation conditions (concentrations, temperature, and time) and level of incorporation on biscuit formulation should be further investigated. In addition, the results indicated that healthier low-fat and low-sugar biscuits without artificial additives and with a delicate texture could be obtained by selecting the right mix of ingredients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr. Fabian Conforti for providing the algarrobo pod used in the present work.

Appendix

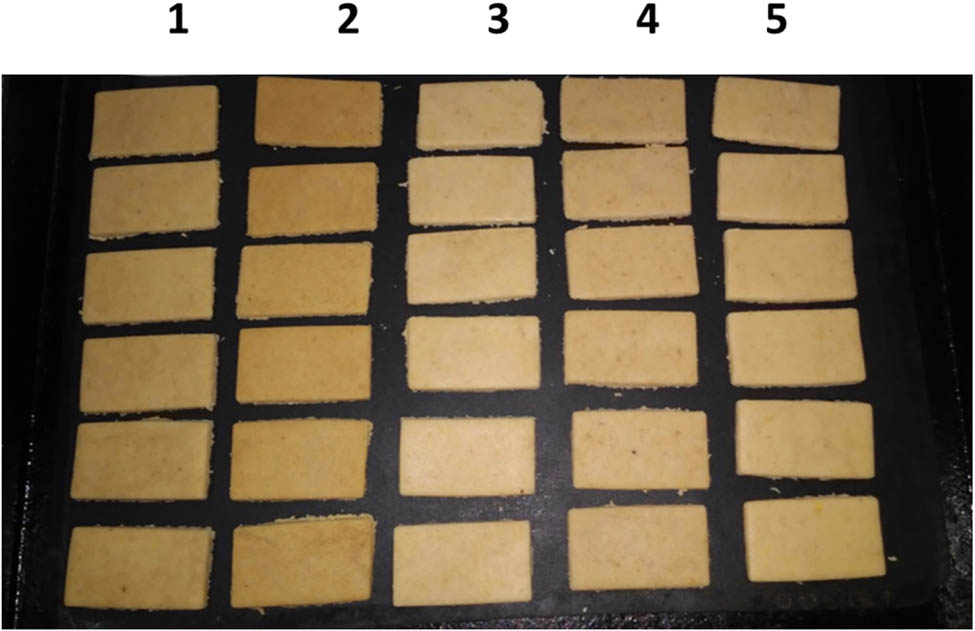

Photo of gluten-free dough prepared from 25:25:25:25 rice flour: cassava starch: maize starch: chickpea flour blend flour with infusions or Prosopis chilensis pod flour (PPF) (1: black tea; 2: coffee; 3: control (prepared with water); 4: PPF; 5: mate).

-

Funding information: This work was financially supported by ANPCyT (PICT 2013-0007, PICT 2016-3047), CONICET, and UNLP of Argentina.

-

Author contribution: PAC: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, data curation, funding acquisition, writing – original draft, review and editing. MP: visualization, formal analysis, writing – original draft, review and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Aboshora W, Yu J, Omar KA, Li Y, Hassanin HA, Navicha WB, et al. Preparation of Doum fruit (Hyphaene thebaica) dietary fiber supplemented biscuits: influence on dough characteristics, biscuits quality, nutritional profile and antioxidant properties. J Food Sci Technol. 2019;56(3):1328–36.10.1007/s13197-019-03605-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] AOAC. Official methods of analysis of the association of official analytical chemists. AOAC; 1984.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Aparicio-Saguilán A, Sayago-Ayerdi SG, Vargas-Torres A, Tovar J, Ascencio-Otero TE, Bello-Pérez LA. Slowly digestible cookies prepared from resistant starch-rich lintnerized banana starch. J Food Compost Anal. 2007;20(3–4):175–81. 10.1007/s13197-019-03605-z.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Baltsavias A, Jurgens A, Van Vliet T. Fracture properties of short-dough biscuits: effect of composition. J Cereal Sci. 1999;29(3):235–44. 10.1006/jcrs.1999.0249.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Benzie IF, Strain JJ. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: the FRAP assay. Anal Biochem. 1996;239(1):70–6. 10.1006/abio.1996.0292.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Bigne F, Puppo MC, Ferrero C. Fibre enrichment of wheat flour with mesquite (Prosopis spp.): effect on breadmaking performance and staling. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2016;65:1008–16. 10.1016/j.lwt.2015.09.028.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Bracesco N, Sanchez AG, Contreras V, Menini T, Gugliucci A. Recent advances on Ilex paraguariensis research: minireview. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;136(3):378–84. 10.1016/j.jep.2010.06.032.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Bravo L, Goya L, Lecumberri E. LC/MS characterization of phenolic constituents of mate (Ilex paraguariensis, St. Hil.) and its antioxidant activity compared to commonly consumed beverages. Food Res Int. 2007;40(3):393–405. 10.1016/j.foodres.2006.10.016.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Brennan CS, Samyue E. Evaluation of starch degradation and textural characteristics of dietary fiber enriched biscuits. Int J Food Prop. 2004;7(3):647–57. 10.1081/JFP-200033070.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Caleja C, Barros L, Antonio AL, Oliveira MBP, Ferreira IC. A comparative study between natural and synthetic antioxidants: Evaluation of their performance after incorporation into biscuits. Food Chem. 2017;216:342–6. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.08.075.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Capparelli A. Los productos alimenticios derivados de Prosopis chilensis (Mol.) Stuntz y P. flexuosa DC., Fabaceae, en la vida cotidiana de los habitantes del NOA y su paralelismo con el algarrobo europeo. Kurtziana. 2007;33(1):1–19.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Capparelli A, Prates L. Exploitation of Algarrobo (Prosopis spp.) fruits by hunter-gatherers from Northeast Patagonia. Chungará (Arica). 2015;47(4):549–63. 10.4067/S0717-73562015005000030.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Cardozo ML, Ordoñez RM, Zampini IC, Cuello AS, Dibenedetto G, Isla MI. Evaluation of antioxidant capacity, genotoxicity and polyphenol content of non conventional foods: prosopis flour. Food Res Int. 2010;43(5):1505–10. 10.1016/j.foodres.2010.04.004.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Chandra S, Singh S, Kumari D. Evaluation of functional properties of composite flours and sensorial attributes of composite flour biscuits. J Food Sci Technol. 2015;52(6):3681–8. 10.1007/s13197-014-1427-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Colla K, Costanzo A, Gamlath S. Fat replacers in baked food products. Foods. 2018;7(12):192. 10.3390/foods7120192.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Da Silva EL, Neiva TJ, Shirai M, Terao J, Abdalla DS. Acute ingestion of yerba mate infusion (Ilex paraguariensis) inhibits plasma and lipoprotein oxidation. Food Res Inter. 2008;41(10):973–9. 10.1016/j.foodres.2008.08.004.Search in Google Scholar

[17] da Silveira TFF, Meinhart AD, Ballus CA, Godoy HT. The effect of the duration of infusion, temperature, and water volume on the rutin content in the preparation of mate tea beverages: an optimization study. Food Res Inter. 2014;60:241–5. 10.1016/j.foodres.2013.09.024.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Derossi A, Ricci I, Caporizzi R, Fiore A, Severini C. How grinding level and brewing method (Espresso, American, Turkish) could affect the antioxidant activity and bioactive compounds in a coffee cup. J Sci Food Agr. 2018;98(8):3198–207. 10.1002/jsfa.8826.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Dhankhar J, Vashistha N, Sharma A. Development of biscuits by partial substitution of refined wheat flour with chickpea flour and date powder. J Microbiol Biotechnol Food Sci. 2019;9:1093–7. 10.15414/jmbfs.2019.8.4.1093-1097.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Diez-Sánchez E, Quiles A, Llorca E, Reiβner AM, Struck S, Rohm H, et al. Extruded flour as techno-functional ingredient in muffins with berry pomace. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2019;113:108300. 10.1016/j.lwt.2019.108300.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Faccin C, Alberti S, Frare L, Vieira LR, Salas-Mellado MM, de Freitas M. Bread with Yerba mate aqueous extract (Ilex paraguariensis A.St.-Hil.). Am J Food Tech. 2015;10(5):206–14. 10.3923/ajft.2015.206.214.Search in Google Scholar

[22] García‐Gómez B, Romero‐Rodríguez Á, Vázquez‐Odériz L, Muñoz‐Ferreiro N, Vázquez M. Sensory evaluation of low‐fat yoghurt produced with microbial transglutaminase and comparison with physicochemical evaluation. J Sci Food Agric. 2019;99(5):2088. 10.1002/jsfa.9401.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Gómez M, Ronda F, Caballero PA, Blanco CA, Rosell CM. Functionality of different hydrocolloids on the quality and shelf-life of yellow layer cakes. Food Hydrocolloid. 2007;21(2):167–73. 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2006.03.012.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Gómez-Juaristi M, Martínez-López S, Sarria B, Bravo L, Mateos R. Absorption and metabolism of yerba mate phenolic compounds in humans. Food Chem. 2018;240:1028–38. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.08.003.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Gonzales-Barron U, Dijkshoorn R, Maloncy M, Finimundy T, Calhelha RC, Pereira C, et al. Nutritive and bioactive properties of mesquite (Prosopis pallida) flour and its technological performance in breadmaking. Foods. 2020;9(5):597. 10.3390/foods9050597.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Guiné RPF, Souta A, Gürbüz B, Almeida E, Lourenço J, Marques L, et al. Textural properties of newly developed cookies incorporating whey residue. J Culin Sci Technol. 2020;18(4):317–32. 10.1080/15428052.2019.1621788.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Heck CI, De Mejia EG. Yerba mate tea (Ilex paraguariensis): a comprehensive review on chemistry, health implications, and technological considerations. J Food Sci Technol. 2007;72(9):R138–51. 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00535.x.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Iriondo-DeHond A, Ramírez B, Escobar FV, del Castillo MD. Antioxidant properties of high molecular weight compounds from coffee roasting and brewing byproducts. Bioact Compd Health Dis. 2019;2(3):48–63. 10.31989/bchd.v2i3.588.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Klunklin W, Savage G. Physicochemical properties and sensory evaluation of wheat-purple rice biscuits enriched with green-lipped mussel powder (Perna canaliculus) and spices. J Food Qual. 2018;1:1–9. 10.1155/2018/7697903.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Koidis A. Developing food products for consumers on a gluten-free diet. Developing food products for consumers with specific dietary needs. Cambridge, UK: Woodhead Publishing; 2016. p. 201–14. 10.1016/B978-0-08-100329-9.00010-4.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Laguna L, Salvador A, Sanz T, Fiszman SM. Performance of a resistant starch rich ingredient in the baking and eating quality of short-dough biscuits. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2011;44(3):737–46. 10.1016/j.lwt.2010.05.034.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Maache-Rezzoug Z, Bouvier JM, Allaf K, Patras C. Effect of principal ingredients on rheological behaviour of biscuit dough and on quality of biscuits. J Food Eng. 1998;35(1):23–42. 10.1016/S0260-8774(98)00017-X.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Mamat H, Hardan MOA, Hill SE. Physicochemical properties of commercial semi-sweet biscuit. Food Chem. 2010;121(4):1029–38. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.01.043.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Manley, D. Classification of biscuits. Technology of biscuits, crackers and cookies. 3rd edn. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing Limited; 1998. p. 221–8. 10.1533/9780857093646.3.271.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Mauer LJ, Jr Bradley RL. Moisture and total solids analysis. In: Nielsen S. Food analysis, food science text series fifth edition. New York, USA: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 279. 10.1007/978-1-4419-1478-1_6.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Meinhart AD, Caldeirão L, Damin FM, Teixeira Filho J, Godoy HT. Analysis of chlorogenic acids isomers and caffeic acid in 89 herbal infusions (tea). J Food Compos Anal. 2018;73:76–82. 10.1016/j.jfca.2018.08.001.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Mildner‐Szkudlarz S, Zawirska‐Wojtasiak R, Obuchowski W, Gośliński M. Evaluation of antioxidant activity of green tea extract and its effect on the biscuits lipid fraction oxidative stability. J Food Sci. 2009;74(8):S362–70. 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2009.01313.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Morales FJ, Martin S, Açar ÖÇ, Arribas-Lorenzo G, Gökmen V. Antioxidant activity of cookies and its relationship with heat-processing contaminants: a risk/benefit approach. Eur Food Res Technol. 2009;228(3):345. 10.1007/s00217-008-0940-9.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Mosafa L, Nadian N, Hojatoleslami M. Investigating the effect of whole oat flour, maltodextrin and isomalt on textural and sensory characteristics of biscuits using response surface methodology. J Food Meas Charact. 2017;11(4):1780–6. 10.1007/s11694-017-9559-5.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Nakov G, Jukić M, Vasileva N, Stamatovska V, Dimov I, Komlenić DK. The influence of different sweeteners on In vitro starch digestion in biscuits with wheat flour and whole barley flour. Sci Study Res Chem Chem Eng Biotechnol Food Ind. 2019;20(1):53–62.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Pareyt B, Talhaoui F, Kerckhofs G, Brijs K, Goesaert H, Wevers M, et al. The role of sugar and fat in sugar-snap cookies: structural and textural properties. J Food Eng. 2009;90(3):400–8. 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2008.07.010.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Pathak R, Thakur V, Gupta RK. Formulation and analysis of papaya fortified biscuits. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2018;7(4):1542–5.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Patrignani M, Brantsen JF, Awika JM, Conforti PA. Application of a novel microwave energy treatment on brewers’ spent grain (BSG): effect on its functionality and chemical characteristics. Food Chem. 2021;346:128935. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128935.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Reddy V, Urooj A, Kumar A. Evaluation of antioxidant activity of some plant extracts and their application in biscuits. Food Chem. 2005;90(1–2):317–21. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.05.038.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Riachi LG, De Maria CAB. Yerba mate: an overview of physiological effects in humans. J Funct Foods. 2017;38:308–20.10.1016/j.jff.2017.09.020Search in Google Scholar

[46] Richelle M, Tavazzi I, Offord E. Comparison of the antioxidant activity of commonly consumed polyphenolic beverages (coffee, cocoa, and tea) prepared per cup serving. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49(7):3438–42. 10.1021/jf0101410.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Rodrigues NP, Bragagnolo N. Identification and quantification of bioactive compounds in coffee brews by HPLC–DAD–MSn. J Food Compos Anal. 2013;32(2):105–15. 10.1016/j.jfca.2013.09.002.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Rodriguez Garcia J, Puig Gómez CA, Salvador A, Hernando Hernando MI. Functionality of several cake ingredients: a comprehensive approach. Czech J Food Sci. 2013;31(4):355–60.10.17221/412/2012-CJFSSearch in Google Scholar

[49] Sánchez-González I, Jiménez-Escrig A, Saura-Calixto F. In vitro antioxidant activity of coffees brewed using different procedures (Italian, espresso and filter). Food Chem. 2005;90(1–2):133–9. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.03.037.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Sandhya AE, Waghray K. Development of sorghum biscuits incorporated with spices. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2018;3(2):120–8.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Saturni L, Ferretti G, Bacchetti T. The gluten-free diet: safety and nutritional quality. Nutrients. 2010;2(1):16–34. 10.3390/nu2010016.Search in Google Scholar

[52] Saha S, Gupta A, Singh SRK, Bharti N, Singh KP, Mahajan V, et al. Compositional and varietal influence of finger millet flour on rheological properties of dough and quality of biscuit. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2011;44(3):616–21. 10.1016/j.lwt.2010.08.009.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Sciammaro L, Ferrero C, Puppo MC. Chemical and nutritional properties of different fractions of Prosopis alba pods and seeds. J Food Meas Charact. 2016;10(1):103–12. 10.1007/s11694-015-9282-z.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Wang Y, Ho CT. Polyphenolic chemistry of tea and coffee: a century of progress. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57(18):8109–14. 10.1021/jf804025c.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] Yashin A, Yashin Y, Xia X, Nemzer B. Chromatographic methods for coffee analysis: a review. J Food Res. 2017;6(4):60–82. 10.5539/jfr.v6n4p60.Search in Google Scholar

[56] Zucco F, Borsuk Y, Arntfield SD. Physical and nutritional evaluation of wheat cookies supplemented with pulse flours of different particle sizes. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2011;44(10):2070–6. 10.1016/j.lwt.2011.06.007.Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Paula Andrea Conforti and Mariela Patrignani, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The nutmeg seedlings growth under pot culture with biofertilizers inoculation

- Recovery of heather (Calluna vulgaris) flowering in northern Finland

- Soil microbiome of different-aged stages of self-restoration of ecosystems on the mining heaps of limestone quarry (Elizavetino, Leningrad region)

- Conversion of land use and household livelihoods in Vietnam: A study in Nghe An

- Foliar selenium application for improving drought tolerance of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.)

- Assessment of deficit irrigation efficiency. Case study: Middle Sebou and Innaouene downstream

- Integrated weed management practices and sustainable food production among farmers in Kwara State, Nigeria

- Determination of morphological changes using gamma irradiation technology on capsicum specie varieties

- Use of maturity traits to identify optimal harvestable maturity of banana Musa AAB cv. “Embul” in dry zone of Sri Lanka

- Theory vs practice: Patterns of the ASEAN-10 agri-food trade

- Intake, nutrient digestibility, nitrogen, and mineral balance of water-restricted Xhosa goats supplemented with vitamin C

- Physicochemical properties of South African prickly pear fruit and peel: Extraction and characterisation of pectin from the peel

- An evaluation of permanent crops: Evidence from the “Plant the Future” project, Georgia

- Probing of the genetic components of seedling emergence traits as selection indices, and correlation with grain yield characteristics of some tropical maize varieties

- Increase in the antioxidant content in biscuits by infusions or Prosopis chilensis pod flour

- Altitude, shading, and management intensity effect on Arabica coffee yields in Aceh, Indonesia

- Climate change adaptation and cocoa farm rehabilitation behaviour in Ahafo Ano North District of Ashanti region, Ghana

- Effect of light spectrum on growth, development, and mineral contents of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L.)

- An assessment of broiler value chain in Nigeria

- Storage root yield and sweetness level selection for new honey sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas [L.] Lam)

- Direct financial cost of weed control in smallholder rubber plantations

- Combined application of poultry litter biochar and NPK fertilizer improves cabbage yield and soil chemical properties

- How does willingness and ability to pay of palm oil smallholders affect their willingness to participate in Indonesian sustainable palm oil certification? Empirical evidence from North Sumatra

- Investigation of the adhesion performance of some fast-growing wood species based on their wettability

- The choice of information sources and marketing channel of Bali cattle farmers in Bali Province

- Preliminary phytochemical screening and in vitro antibacterial activity of Plumbago indica (Laal chitrak) root extracts against drug-resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae

- Agronomic and economic performance of maize (Zea mays L.) as influenced by seed bed configuration and weed control treatments

- Selection and characterization of siderophores of pathogenic Escherichia coli intestinal and extraintestinal isolates

- Effectiveness of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L.) living mulch on weed suppression and yield of maize (Zea mays L.)

- Cow milk and its dairy products ameliorate bone toxicity in the Coragen-induced rat model

- The motives of South African farmers for offering agri-tourism

- Morphophysiological changes and reactive oxygen species metabolism in Corchorus olitorius L. under different abiotic stresses

- Nanocomposite coatings for hatching eggs and table eggs

- Climate change stressors affecting household food security among Kimandi-Wanyaga smallholder farmers in Murang’a County, Kenya

- Genetic diversity of Omani barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) germplasm

- Productivity and profitability of organic and conventional potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) production in West-Central Bhutan

- Response of watermelon growth, yield, and quality to plant density and variety in Northwest Ethiopia

- Sex allocation and field population sex ratio of Apanteles taragamae Viereck (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), a larval parasitoid of the cucumber moth Diaphania indica Saunders (Lepidoptera: Crambidae)

- Comparison of total nutrient recovery in aquaponics and conventional aquaculture systems

- Relationships between soil salinity and economic dynamics: Main highlights from literature

- Effects of soil amendments on selected soil chemical properties and productivity of tef (Eragrostis tef [Zucc.] Trotter) in the highlands of northwest Ethiopia

- Influence of integrated soil fertilization on the productivity and economic return of garlic (Allium sativum L.) and soil fertility in northwest Ethiopian highlands

- Physiological and biochemical responses of onion plants to deficit irrigation and humic acid application

- The incorporation of Moringa oleifera leaves powder in mutton patties: Influence on nutritional value, technological quality, and sensory acceptability

- Response of biomass, grain production, and sugar content of four sorghum plant varieties (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) to different plant densities

- Assessment of potentials of Moringa oleifera seed oil in enhancing the frying quality of soybean oil

- Influences of spacing on yield and root size of carrot (Daucus carota L.) under ridge-furrow production

- Review Articles

- A review of upgradation of energy-efficient sustainable commercial greenhouses in Middle East climatic conditions

- Plantago lanceolata – An overview of its agronomically and healing valuable features

- Special Issue on CERNAS 2020

- The role of edible insects to mitigate challenges for sustainability

- Morphology and structure of acorn starches isolated by enzymatic and alkaline methods

- Evaluation of FT-Raman and FTIR-ATR spectroscopy for the quality evaluation of Lavandula spp. Honey

- Factors affecting eating habits and knowledge of edible flowers in different countries

- Ideal pH for the adsorption of metal ions Cr6+, Ni2+, Pb2+ in aqueous solution with different adsorbent materials

- Determination of drying kinetics, specific energy consumption, shrinkage, and colour properties of pomegranate arils submitted to microwave and convective drying

- Eating habits and food literacy: Study involving a sample of Portuguese adolescents

- Characterization of dairy sheep farms in the Serra da Estrela PDO region

- Development and characterization of healthy gummy jellies containing natural fruits

- Agro-ecological services delivered by legume cover crops grown in succession with grain corn crops in the Mediterranean region

- Special issue on CERNAS 2020: Message from the Editor

- Special Issue on ICESAT 2019

- Climate field schools to increase farmers’ adaptive capacity to climate change in the southern coastline of Java

- Special Issue on the International Conference on Agribusiness and Rural Development - IConARD 2020

- Supply chain efficiency of red chili based on the performance measurement system in Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Sustainable value of rice farm based on economic efficiency in Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Enhancing the performance of conventional coffee beans drying with low-temperature geothermal energy by applying HPHE: An experimental study

- Opportunities of using Spirulina platensis as homemade natural dyes for textiles

- Special Issue on the APA 2019 - 11th Triennial Conference

- Expanding industrial uses of sweetpotato for food security and poverty alleviation

- A survey on potato productivity, cultivation and management constraints in Mbala district of Northern Zambia

- Orange-fleshed sweetpotato: Strategies and lessons learned for achieving food security and health at scale in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Growth and yield of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) as affected by storage conditions and storage duration in Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria

- Special Issue on the International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research - Agrarian Sciences

- Application of nanotechnologies along the food supply chain

- Special Issue on Agriculture, Climate Change, Information Technology, Food and Animal (ACIFAS 2020)

- The use of endophytic growth-promoting bacteria to alleviate salinity impact and enhance the chlorophyll, N uptake, and growth of rice seedling

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- The nutmeg seedlings growth under pot culture with biofertilizers inoculation

- Recovery of heather (Calluna vulgaris) flowering in northern Finland

- Soil microbiome of different-aged stages of self-restoration of ecosystems on the mining heaps of limestone quarry (Elizavetino, Leningrad region)

- Conversion of land use and household livelihoods in Vietnam: A study in Nghe An

- Foliar selenium application for improving drought tolerance of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.)

- Assessment of deficit irrigation efficiency. Case study: Middle Sebou and Innaouene downstream

- Integrated weed management practices and sustainable food production among farmers in Kwara State, Nigeria

- Determination of morphological changes using gamma irradiation technology on capsicum specie varieties

- Use of maturity traits to identify optimal harvestable maturity of banana Musa AAB cv. “Embul” in dry zone of Sri Lanka

- Theory vs practice: Patterns of the ASEAN-10 agri-food trade

- Intake, nutrient digestibility, nitrogen, and mineral balance of water-restricted Xhosa goats supplemented with vitamin C

- Physicochemical properties of South African prickly pear fruit and peel: Extraction and characterisation of pectin from the peel

- An evaluation of permanent crops: Evidence from the “Plant the Future” project, Georgia

- Probing of the genetic components of seedling emergence traits as selection indices, and correlation with grain yield characteristics of some tropical maize varieties

- Increase in the antioxidant content in biscuits by infusions or Prosopis chilensis pod flour

- Altitude, shading, and management intensity effect on Arabica coffee yields in Aceh, Indonesia

- Climate change adaptation and cocoa farm rehabilitation behaviour in Ahafo Ano North District of Ashanti region, Ghana

- Effect of light spectrum on growth, development, and mineral contents of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L.)

- An assessment of broiler value chain in Nigeria

- Storage root yield and sweetness level selection for new honey sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas [L.] Lam)

- Direct financial cost of weed control in smallholder rubber plantations

- Combined application of poultry litter biochar and NPK fertilizer improves cabbage yield and soil chemical properties

- How does willingness and ability to pay of palm oil smallholders affect their willingness to participate in Indonesian sustainable palm oil certification? Empirical evidence from North Sumatra

- Investigation of the adhesion performance of some fast-growing wood species based on their wettability

- The choice of information sources and marketing channel of Bali cattle farmers in Bali Province

- Preliminary phytochemical screening and in vitro antibacterial activity of Plumbago indica (Laal chitrak) root extracts against drug-resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae

- Agronomic and economic performance of maize (Zea mays L.) as influenced by seed bed configuration and weed control treatments

- Selection and characterization of siderophores of pathogenic Escherichia coli intestinal and extraintestinal isolates

- Effectiveness of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L.) living mulch on weed suppression and yield of maize (Zea mays L.)

- Cow milk and its dairy products ameliorate bone toxicity in the Coragen-induced rat model

- The motives of South African farmers for offering agri-tourism

- Morphophysiological changes and reactive oxygen species metabolism in Corchorus olitorius L. under different abiotic stresses

- Nanocomposite coatings for hatching eggs and table eggs

- Climate change stressors affecting household food security among Kimandi-Wanyaga smallholder farmers in Murang’a County, Kenya

- Genetic diversity of Omani barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) germplasm

- Productivity and profitability of organic and conventional potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) production in West-Central Bhutan

- Response of watermelon growth, yield, and quality to plant density and variety in Northwest Ethiopia

- Sex allocation and field population sex ratio of Apanteles taragamae Viereck (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), a larval parasitoid of the cucumber moth Diaphania indica Saunders (Lepidoptera: Crambidae)

- Comparison of total nutrient recovery in aquaponics and conventional aquaculture systems

- Relationships between soil salinity and economic dynamics: Main highlights from literature

- Effects of soil amendments on selected soil chemical properties and productivity of tef (Eragrostis tef [Zucc.] Trotter) in the highlands of northwest Ethiopia

- Influence of integrated soil fertilization on the productivity and economic return of garlic (Allium sativum L.) and soil fertility in northwest Ethiopian highlands

- Physiological and biochemical responses of onion plants to deficit irrigation and humic acid application

- The incorporation of Moringa oleifera leaves powder in mutton patties: Influence on nutritional value, technological quality, and sensory acceptability

- Response of biomass, grain production, and sugar content of four sorghum plant varieties (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) to different plant densities

- Assessment of potentials of Moringa oleifera seed oil in enhancing the frying quality of soybean oil

- Influences of spacing on yield and root size of carrot (Daucus carota L.) under ridge-furrow production

- Review Articles

- A review of upgradation of energy-efficient sustainable commercial greenhouses in Middle East climatic conditions

- Plantago lanceolata – An overview of its agronomically and healing valuable features

- Special Issue on CERNAS 2020

- The role of edible insects to mitigate challenges for sustainability

- Morphology and structure of acorn starches isolated by enzymatic and alkaline methods

- Evaluation of FT-Raman and FTIR-ATR spectroscopy for the quality evaluation of Lavandula spp. Honey

- Factors affecting eating habits and knowledge of edible flowers in different countries

- Ideal pH for the adsorption of metal ions Cr6+, Ni2+, Pb2+ in aqueous solution with different adsorbent materials

- Determination of drying kinetics, specific energy consumption, shrinkage, and colour properties of pomegranate arils submitted to microwave and convective drying

- Eating habits and food literacy: Study involving a sample of Portuguese adolescents

- Characterization of dairy sheep farms in the Serra da Estrela PDO region

- Development and characterization of healthy gummy jellies containing natural fruits

- Agro-ecological services delivered by legume cover crops grown in succession with grain corn crops in the Mediterranean region

- Special issue on CERNAS 2020: Message from the Editor

- Special Issue on ICESAT 2019

- Climate field schools to increase farmers’ adaptive capacity to climate change in the southern coastline of Java

- Special Issue on the International Conference on Agribusiness and Rural Development - IConARD 2020

- Supply chain efficiency of red chili based on the performance measurement system in Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Sustainable value of rice farm based on economic efficiency in Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Enhancing the performance of conventional coffee beans drying with low-temperature geothermal energy by applying HPHE: An experimental study

- Opportunities of using Spirulina platensis as homemade natural dyes for textiles

- Special Issue on the APA 2019 - 11th Triennial Conference

- Expanding industrial uses of sweetpotato for food security and poverty alleviation

- A survey on potato productivity, cultivation and management constraints in Mbala district of Northern Zambia

- Orange-fleshed sweetpotato: Strategies and lessons learned for achieving food security and health at scale in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Growth and yield of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) as affected by storage conditions and storage duration in Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria

- Special Issue on the International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research - Agrarian Sciences

- Application of nanotechnologies along the food supply chain

- Special Issue on Agriculture, Climate Change, Information Technology, Food and Animal (ACIFAS 2020)

- The use of endophytic growth-promoting bacteria to alleviate salinity impact and enhance the chlorophyll, N uptake, and growth of rice seedling