Abstract

We investigate the scattering properties of coupled parity-time (PT) symmetric chiral nanospheres with scattering matrix formalism. The exceptional points, i.e., spectral singularities at which the eigenvalues and eigenvectors simultaneously coalesce in the parameter space, of scattering matrix can be tailored by the chirality of the nanospheres. We also calculate the scattering, absorption and extinction cross sections of the PT-symmetric chiral scatter under illumination by monochromatic left- and right-circularly polarized plane waves. We find that the scattering cross section of the nanostructures exhibits an asymmetry when the plane waves are incident from the loss and gain regions, respectively, especially in the broken phase, and the optical cross section exhibits circular dichroism, i.e., differential extinction when the PT-symmetric scatter is endowed with chirality. In particular, under illumination by linearly polarized monochromatic plane waves without intrinsic chirality, the ellipticity of scattered fields in the forward direction, denoting the chirality of light, becomes larger when the scatter is in the PT-symmetry-broken phase. Our findings demonstrate that the gain and loss can control the optical chirality and enhance the chiroptical interactions and pave the way for studying the resonant chiral light–matter interactions in non-Hermitian photonics.

1 Introduction

Chirality, which refers to a geometric handedness of a chiral object that the mirror image cannot be superposed onto itself, is ubiquitous in nature, known for chiral molecules and the double-helix structure of DNA [1]. Analogously, light also exhibits chiral properties and enables carrying orbital angular momentum (OAM) and/or spin angular momentum (SAM), such as OAM-carrying vectorial light beams and SAM-carrying circularly polarized light [2]. Recently, the chiral light–matter interactions have attracted great interest in the optical community [3], and inspired technologically important applications such as chiral sensing [4]. Various nanostructures and relevant physical mechanisms have been designed and studied to enhance the chiroptical response, including the use of chiral plasmonic nanostructures [5], high-index dielectric nanostructures [6, 7], helicity-preserving optical cavities [8], planar dielectric nanostructures [9] and chiral metamaterials designed by deep learning [10].

Non-Hermiticity in many physical systems has drawn great attention in recent years since the discovery of real spectra in parity-time (PT) symmetric complex Hamiltonians [11], which commutes with PT operator, [H, PT] = 0, where the parity operator P amounts to reversal of spatial coordinates,

The light scattering of small particles or aggregates has been extensively studied in classical electrodynamics, such as the Mie scattering theory of optically active particles, due to various practical applications [21]. However, the research of combining chirality and PT symmetry in optical systems is rarely reported, except for a theoretical proposal of PT-symmetric chiral metamaterials consisting of slabs of opposite chirality [22, 23]. In this paper, we study the light scattering properties of a PT-symmetric chiral nanosphere dimer using the electromagnetic transition matrix (T-matrix) and scattering matrix (S-matrix) [18, 24]. By investigating the influence of chirality and non-Hermiticity on the extinction, scattering, absorption cross sections and ellipticity of scattered light of the dimer system, we reveal that the gain and loss play an important role in chiral optical systems that can enhance the chiroptical responses and also allow to manipulate exceptional points by the chirality. The interplay between PT-symmetry and chirality investigated in nanoparticle systems can also be potentially revealed through far-field scatterings.

2 Methods

2.1 T-matrix and S-matrix

As sketched in Figure 1, we study the chiral electromagnetic response of a pair of chiral nanoparticles with the macroscopic Maxwell’s equations and constitutive equations (the time dependence

where

Two chiral nanoparticles positioned symmetrically along the x-axis to form a PT-symmetric optical scattering system. The distance between the centres of two spheres is d. The radii of two spheres are a, the relative permittivity of gain sphere is

To solve the wave equation, we can use the helicity to split the electric field into left circularly polarized (LCP) wave and right circularly polarized wave (RCP) [26], i.e.,

where

where the subscripts

Applying the electromagnetic boundary condition at the surface of the chiral sphere, we can obtain the T-matrix of each single chiral sphere [28, 29],

The T-matrix is nondiagonal, exhibiting the mixing of the electric and magnetic multipolar modes due to the chirality, and the Mie coefficients are,

where

where

where

can be derived from the T-matrix with the aid of relation between SVWFs [13]. To find the PT-symmetric conditions of the chiral scattering system, we take the action of PT operator on the wave equation, i.e., Eq. (2), and obtain,

The scattering matrix of a general PT-symmetric optical system has the fundamental relation [18],

The weaker condition than unitarity implies the existence of spontaneous PT-symmetry breaking where the eigenvalues of scattering matrix are not unimodular, i.e., the eigenstate can exhibit amplification or dissipation. If the chiral media is reciprocal, the chirality parameter κ is a real number. It is worthy to note that the spontaneous PT-symmetry breaking of the scattering matrix indeed coincides with the PT-symmetry-breaking transition of the underlying PT-symmetric Hamiltonian [32].

2.2 Optical cross section

The scattering and absorption cross sections of the chiral optical system can be derived from the conservation of energy [33–35], when a monochromatic plane wave illuminates the scatter, and the total fields outside a sphere that circumscribes the scatter can be decomposed into incident and scattered waves, i.e.,

where the

where

According to the T-matrix, the scattering cross section can also be given by

where

It is obvious that the absorption in the chiral medium has three contributions, while the absorption due to the chirality parameter is proportional to the optical chirality [36],

The extinction cross section is

Note that the extinction and absorption cross sections of an optical scattering system can be negative in the presence of gain.

3 Results and discussions

We investigate the scattering properties of PT-symmetric coupled chiral spheres based on the theory and methods developed in the previous section. Our scattering system is depicted in Figure 1: two chiral nanoparticles both with a radius a = 60 nm positioned symmetrically along the x-axis, and their centre-to-centre distance is d = 130 nm. The sphere with optical gain is placed at −65 nm, and the lossy sphere is at 65 nm. The real part of relative permittivity is

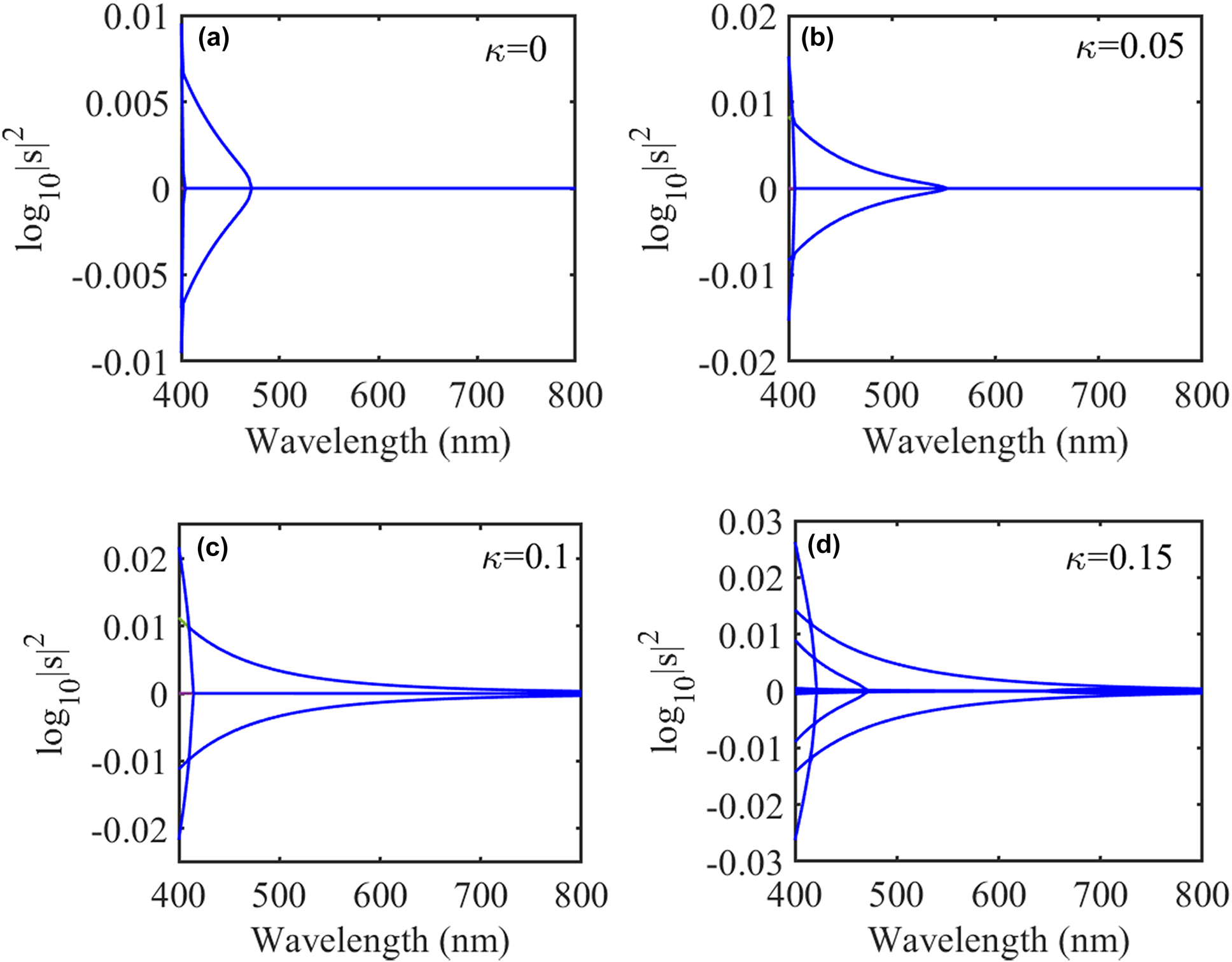

We first study the eigenvalues of the S-matrix of the nano-particle system influenced by the chirality parameter and only consider reciprocal chiral media, i.e.,

Semi-log plots of scattering matrix eigenvalues for the coupled PT-symmetric chiral nanospheres as a function of wavelength with chirality parameter

Now we consider the chiral nanoparticles, when the chirality parameter is

The optical cross section characterizes the capability of light concentration into sub-wavelength dimensions by metallic and dielectric nanoparticles. At low frequencies, the optical cross section of small nanoparticles is proportional to

where

The optical cross sections of the PT-symmetric chiral nanospheres are shown in Figure 3. Here, we set the chirality parameter and non-Hermiticity parameter as

Normalized extinction (black dash lines), scattering (red dot lines), and absorption (blue lines) cross sections of the PT-symmetric chiral nanospheres. The left and RCP waves are incident from the lossy sphere (a) and (b) and from the gain sphere (c) and (d), respectively. The chirality parameter and non-Hermiticity parameter are

While the extinction cross sections are different when the plane waves with opposite polarizations are incident from the same direction, so we can define the circular differential extinction cross section for chiral scatter, i.e.,

To further demonstrate the scattering asymmetry, we calculate the optical cross sections of PT-symmetric nanospheres without chirality and coupled chiral nanoparticles without gain and loss, which are shown in Figure 4. In Figure 4a and b, we can see that the scattering asymmetry results from the gain and loss, but the extinction cross sections of LCP and RCP waves are the same when they are incident from same and reverse directions in the absence of chirality. When there is no gain and loss, the absorption cross sections of the coupled chiral nanoparticles are vanishing, so the scattering cross sections and extinction cross sections are equal. As a result of Lorentz reciprocity, the coupled chiral nanoparticles without gain and loss exhibit no scattering asymmetry. In addition, scattering cross sections are the same when the RCP and LCP waves are incident from the same directions, this can be explained by the total chirality of coupled nanospheres is zero.

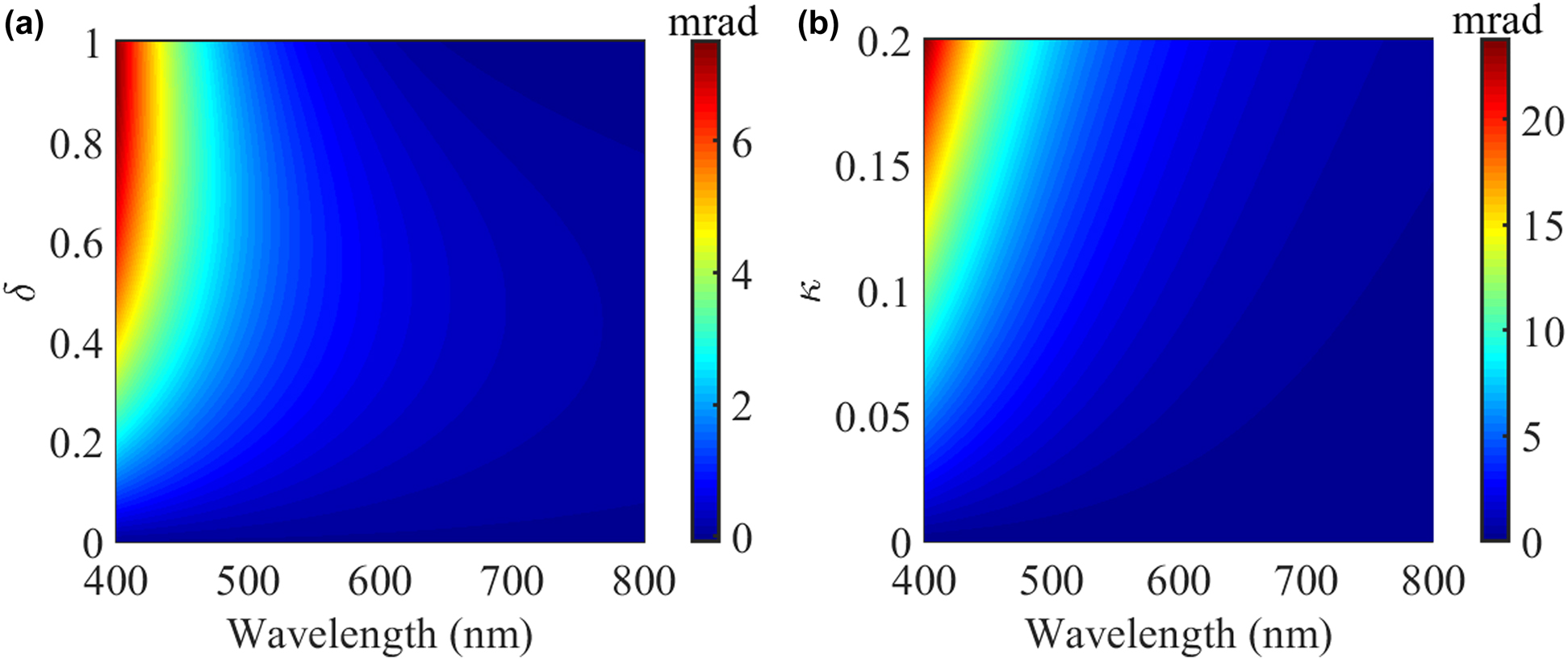

(a) Normalized extinction (black dash lines), scattering (red dot lines), and absorption (blue lines) cross sections of the PT-symmetric nanospheres without chirality, i.e.,

Finally, we investigate the effect of PT-symmetry and chirality on the incident linearly polarized plane wave. The ellipticity of scattered fields is a widely used parameter to denote the polarization states of light and hence evaluate the chirality of an optical scattering system. For example, the ellipticities for right-handed circularly polarized waves, linearly polarized waves and left-handed circularly polarized waves are -π/4, 0 and π/4, respectively [21]. Since the light scattering amplitude in the forward direction is related to the extinction cross section according to the well-known optical theorem [41], we only need to calculate the ellipticities of scattered fields in the forward direction under linearly polarized plane wave illumination without chirality as shown in Figure 5. In Figure 5a, we can see that the ellipticities of scattered fields become greater than zero when the incident wavelength is smaller and the non-Hermiticity parameter becomes large. In other words, the chirality of scattered light becomes large when the scattering system is in the PT-symmetry-broken phase, while the scattered field in the forward direction exhibits no chirality in the unbroken phase. Likewise, In Figure 5b, when the non-Hermiticity parameter is δ = 0.5, the ellipticity of scattered fields becomes large when the scatter is in PT-symmetry broken phase when we tailor the chirality parameter.

(a) Ellipticity of scattered fields in the forward direction as a function of non-Hermiticity parameter and wavelength. The chirality parameter is κ = 0.05. (b) Ellipticity of scattered field in the forward direction as a function of chirality parameter and wavelength. The non-Hermiticity parameter is δ = 0.5. The incident plane wave is linearly polarized plane wave without chirality.

4 Conclusions

We have studied the scattering properties of PT-symmetric chiral coupled spheres through electromagnetic T-matrix and S-matrix. We found that the exceptional points of S-matrix can be tailored by the chirality of nanospheres. When the PT-symmetric reciprocal chiral scatter is illuminated by the monochromatic LCP and RCP plane waves, the scattering and absorption cross sections exhibit asymmetry when the plane waves are incident from the loss and gain regions, respectively. While the scattering cross section are the same when the incident plane waves are incident from the same directions with different polarizations. In addition, the PT-symmetric reciprocal chiral scatter exhibits the circular dichroism, i.e., differential extinction. By calculating the ellipticity of scattered fields in the forward direction under linearly polarized monochromatic plane wave illumination, we also find that the ellipticity becomes larger when the scatter is in the PT-symmetric broken phase. Our results will provide help to study the enhanced chiroptical response by exploiting gain and loss in chiral nanostructures, such as the non-Hermitian topological chiral metamaterials.

-

Author contribution: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Research funding: Hong Kong Polytechnic University through the “Life Science Research” project (1-ZVH9); the “State Key Laboratory of Chemical Biology and Drug Discovery” research project (K-BBX4); the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong through the Collaborative Research Project (C6013-18G).

-

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

[1] M. Schäferling, Chiral Nanophotonics: Chiral Optical Properties of Plasmonic Systems, Switzerland, Springer International Publishing, 2017.10.1007/978-3-319-42264-0Suche in Google Scholar

[2] J. Mun, M. Kim, Y. Yang, et al.., “Electromagnetic chirality: from fundamentals to nontraditional chiroptical phenomena,” Light Sci. Appl., vol. 9, pp. 1–18, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-020-00367-8.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] S. Yoo and Q. Park, “Chiral light-matter interaction in optical resonators,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 114, p. 203003, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.114.203003.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] S. Yoo and Q. Park, “Metamaterials and chiral sensing: a review of fundamentals and applications,” Nanophotonics, vol. 8, pp. 249–261, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2018-0167.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] A. O. Govorov and Z. Fan, “Theory of chiral plasmonic nanostructures comprising metal nanocrystals and chiral molecular media,” ChemPhysChem, vol. 13, pp. 2551–2560, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphc.201100958.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] S. Yoo and Q. Park, “Enhancement of chiroptical signals by circular differential Mie scattering of nanoparticles,” Sci. Rep., vol. 5, pp. 1–8, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep14463.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] J. Mun and J. Rho, “Surface-enhanced circular dichroism by multipolar radiative coupling,” Opt. Lett., vol. 43, pp. 2856–2859, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.43.002856.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] J. Feis, D. Beutel, J. Köpfler, et al.., “Helicity-preserving optical cavity modes for enhanced sensing of chiral molecules,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 124, 2020, Art no. 033201. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.124.033201.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] A. Zhu, W. Chen, A. Zaidi, et al.., “Giant intrinsic chiro-optical activity in planar dielectric nanostructures,” Light Sci. Appl., vol. 7, pp. 17158, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2017.158.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] W. Ma, F. Cheng, and Y. Liu, “Deep-learning-enabled on-demand design of chiral metamaterials,” ACS Nano, vol. 12, pp. 6326–6334, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.8b03569.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] C. M. Bender and S. Boettcher, “Real spectra in non-Hermitian Hamiltonians having PT symmetry,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 80, pp. 5243–5246, 1998. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.80.5243.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] A. Guo, G. J. Salamo, D. Duchesne, et al.., “Observation of PT-symmetry breaking in complex optical potentials,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 103, 2009, Art no. 093902. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.093902.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] X. L. Chen, W. C. Yue, R. X. Tao, P. J. Yao, and W. Liu, “Scattering phenomenon of PT-symmetric dielectric-nanosphere structure,” Phys. Rev., vol. 94, 2016, Art no. 053829. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.94.053829.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] M. A. Miri and A. Alù, “Exceptional points in optics and photonics,” Science, vol. 363, 2019, Art no. eaar7709. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aar7709.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Z. Lin, H. Ramezani, T. Eichelkraut, T. Kottos, H. Cao, and D. N. Christodoulides, “Unidirectional invisibility induced by PT-symmetric periodic structures,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 106, p. 213901, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.213901.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] M. Sakhdari, M. Hajizadegan, Q. Zhong, D. N. Christodoulides, R. El-Ganainy, and P.-Y. Chen, “Experimental observation of PT symmetry breaking near divergent exceptional points,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 123, p. 193901, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.123.193901.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] L. Xiao, X. Zhan, Z. Bian, et al.., “Observation of topological edge states in parity–time-symmetric quantum walks,” Nat. Phys., vol. 13, pp. 1117–1123, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys4204.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Y. D. Chong, L. Ge, and A. D. Stone, “PT-symmetry breaking and laser-absorber modes in optical scattering systems,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 106, 2012, Art no. 093902. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.093902.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Y. Sun, W. Tan, H. Q. Li, J. Li, and H. Chen, “Experimental demonstration of a coherent perfect absorber with PT phase transition,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 112, p. 143903, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.112.143903.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Z. J. Wong, Y. L. Xu, J. Kim, et al.., “Lasing and anti-lasing in a single cavity,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 10, pp. 796–801, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2016.216.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] C. F. Bohren and D. R. Huffman, Absorption and Scattering of Light by Small Particles, New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1998.10.1002/9783527618156Suche in Google Scholar

[22] S. Droulias, S. Katsantonis, I. Kafesaki, M. Soukoulis, and N. Economou, “Chiral metamaterials with PT symmetry and beyond,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 122, p. 213201, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.122.213201.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] I. Katsantonis, S. Droulias, C. M. Soukoulis, E. N. Economou, and M. Kafesaki, “PT-symmetric chiral metamaterials: asymmetric effects and PT-phase control,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 101, p. 214109, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.101.214109.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] M. I. Mishchenko, L. D. Travis, and A. A. Lacis, Scattering, Absorption, and Emission of Light by Small Particles, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2002.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] I. V. Lindell, A. H. Sihvola, S. A. Tretyakov, and A. J. Viitanen, Electromagnetic Waves in Chiral and Bi-isotropic Media, Boston, Artech House, 1994.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] A. Aiello and M. V. Berry, “Note on the helicity decomposition of spin and orbital optical currents,” J. Opt., vol. 17, 2015, Art no. 062001. https://doi.org/10.1088/2040-8978/17/6/062001.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] I. Fernandez-Corbaton, X. Zambrana-Puyalto, and G. Molina-Terriza, “Helicity and angular momentum: a symmetry-based framework for the study of light-matter interactions,” Phys. Rev., vol. 86, 2012, Art no. 042103. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.86.042103.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] H. Chen, C. H. Liang, S. Y. Liu, and Z. F. Lin, “Chirality sorting using two-wave-interference–induced lateral optical force,” Phys. Rev., vol. 93, 2016, Art no. 053833. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.93.053833.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Q. C. Shang, Z. S. Wu, T. Qu, Z. J. Li, L. Bai, and L. Gong, “Analysis of the radiation force and torque exerted on a chiral sphere by a Gaussian beam,” Opt. Express, vol. 21, pp. 8677–8688, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.21.008677.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] M. Fruhnert, I. Fernandez-Corbaton, V. Yannopapas, and C. Rockstuhl, “Computing the T-matrix of a scattering object with multiple plane wave illuminations,” Beilstein J. Nanotechnol., vol. 8, pp. 614–626, 2017. https://doi.org/10.3762/bjnano.8.66.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] G. Demésy, J. C. Auger, and B. Stout, “Scattering matrix of arbitrarily shaped objects: combining finite elements and vector partial waves,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. A, vol. 35, pp. 1401–1409, 2018.10.1364/JOSAA.35.001401Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] L. Ge, Y. D. Chong, and A. D. Stone, “Conservation relations and anisotropic transmission resonances in one-dimensional PT-symmetric photonic heterostructures,” Phys. Rev., vol. 85, 2012, Art no. 023802. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.85.023802.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] M. Born and E. Wolf, Principles of Optics: Electromagnetic Theory of Propagation, Interference and Diffraction of Light, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2000.10.1063/1.1325200Suche in Google Scholar

[34] M. J. Berg, C. M. Sorensen, and A. Chakrabarti, “Extinction and the optical theorem. Part I. single particles,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. A, vol. 25, pp. 1504–1513, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1364/josaa.25.001504.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] L. Novotny and B. Hecht, Principles of Nano-Optics, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2006.10.1017/CBO9780511813535Suche in Google Scholar

[36] J. E. Vázquez-Lozano and A. Martínez, “Optical chirality in dispersive and lossy media,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 121, 2018, Art no. 043901.10.1103/PhysRevLett.121.043901Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] V. V. Klimov, I. V. Zabkov, A. A. Pavlov, and D. V. Guzatov, “Eigen oscillations of a chiral sphere and their influence on radiation of chiral molecules,” Opt. Express, vol. 22, pp. 18564–18578, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.22.018564.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] R. Zhao, T. Koschny, and C. M. Soukoulis, “Chiral metamaterials: retrieval of the effective parameters with and without substrate,” Opt. Express, vol. 18, pp. 14553–14567, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.18.014553.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Y. M. Xie, W. Tan, and Z. G. Wang, “Anomalous forward scattering of dielectric gain nanoparticles,” Opt. Express, vol. 23, pp. 2091–2100, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.23.002091.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] D. L. Sounas and A. Alù, “Extinction symmetry for reciprocal objects and its implications on cloaking and scattering manipulation,” Opt. Lett., vol. 39, pp. 4053–4056, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.39.004053.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] A. B. Evlyukhin, T. Fischer, C. Reinhardt, and B. N. Chichkov, “Optical theorem and multipole scattering of light by arbitrarily shaped nanoparticles,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 94, p. 205434, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.94.205434.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2022 Xiaolin Chen et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial on special issue: “Metamaterials and plasmonics in Asia”

- Reviews

- Waveguide effective plasmonics with structure dispersion

- Graphene-based plasmonic metamaterial for terahertz laser transistors

- Recent advances in metamaterials for simultaneous wireless information and power transmission

- Multi-freedom metasurface empowered vectorial holography

- Nanophotonics-inspired all-silicon waveguide platforms for terahertz integrated systems

- Optical metasurfaces towards multifunctionality and tunability

- The perspectives of broadband metasurfaces and photo-electric tweezer applications

- Free-form optimization of nanophotonic devices: from classical methods to deep learning

- Optical generation of strong-field terahertz radiation and its application in nonlinear terahertz metasurfaces

- Responsive photonic nanopixels with hybrid scatterers

- Research Articles

- Efficient modal analysis of plasmonic nanoparticles: from retardation to nonclassical regimes

- Molecular chirality detection using plasmonic and dielectric nanoparticles

- Vortex radiation from a single emitter in a chiral plasmonic nanocavity

- Reconfigurable Mach–Zehnder interferometer for dynamic modulations of spoof surface plasmon polaritons

- Manipulating guided wave radiation with integrated geometric metasurface

- Comparison of second harmonic generation from cross-polarized double-resonant metasurfaces on single crystals of Au

- Rotational varifocal moiré metalens made of single-crystal silicon meta-atoms for visible wavelengths

- Meta-lens light-sheet fluorescence microscopy for in vivo imaging

- All-metallic high-efficiency generalized Pancharatnam–Berry phase metasurface with chiral meta-atoms

- Drawing structured plasmonic field with on-chip metalens

- Negative refraction in twisted hyperbolic metasurfaces

- Anisotropic impedance surfaces activated by incident waveform

- Machine–learning-enabled metasurface for direction of arrival estimation

- Intelligent electromagnetic metasurface camera: system design and experimental results

- High-efficiency generation of far-field spin-polarized wavefronts via designer surface wave metasurfaces

- Terahertz meta-chip switch based on C-ring coupling

- Resonance-enhanced spectral funneling in Fabry–Perot resonators with a temporal boundary mirror

- Dynamic inversion of planar-chiral response of terahertz metasurface based on critical transition of checkerboard structures

- Terahertz 3D bulk metamaterials with randomly dispersed split-ring resonators

- BST-silicon hybrid terahertz meta-modulator for dual-stimuli-triggered opposite transmission amplitude control

- Gate-tuned graphene meta-devices for dynamically controlling terahertz wavefronts

- Dual-band composite right/left-handed metamaterial lines with dynamically controllable nonreciprocal phase shift proportional to operating frequency

- Highly suppressed solar absorption in a daytime radiative cooler designed by genetic algorithm

- All-optical binary computation based on inverse design method

- Exciton-dielectric mode coupling in MoS2 nanoflakes visualized by cathodoluminescence

- Broadband wavelength tuning of electrically stretchable chiral photonic gel

- Spatio-spectral decomposition of complex eigenmodes in subwavelength nanostructures through transmission matrix analysis

- Scattering asymmetry and circular dichroism in coupled PT-symmetric chiral nanoparticles

- A large-scale single-mode array laser based on a topological edge mode

- Far-field optical imaging of topological edge states in zigzag plasmonic chains

- Omni-directional and broadband acoustic anti-reflection and universal acoustic impedance matching

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial on special issue: “Metamaterials and plasmonics in Asia”

- Reviews

- Waveguide effective plasmonics with structure dispersion

- Graphene-based plasmonic metamaterial for terahertz laser transistors

- Recent advances in metamaterials for simultaneous wireless information and power transmission

- Multi-freedom metasurface empowered vectorial holography

- Nanophotonics-inspired all-silicon waveguide platforms for terahertz integrated systems

- Optical metasurfaces towards multifunctionality and tunability

- The perspectives of broadband metasurfaces and photo-electric tweezer applications

- Free-form optimization of nanophotonic devices: from classical methods to deep learning

- Optical generation of strong-field terahertz radiation and its application in nonlinear terahertz metasurfaces

- Responsive photonic nanopixels with hybrid scatterers

- Research Articles

- Efficient modal analysis of plasmonic nanoparticles: from retardation to nonclassical regimes

- Molecular chirality detection using plasmonic and dielectric nanoparticles

- Vortex radiation from a single emitter in a chiral plasmonic nanocavity

- Reconfigurable Mach–Zehnder interferometer for dynamic modulations of spoof surface plasmon polaritons

- Manipulating guided wave radiation with integrated geometric metasurface

- Comparison of second harmonic generation from cross-polarized double-resonant metasurfaces on single crystals of Au

- Rotational varifocal moiré metalens made of single-crystal silicon meta-atoms for visible wavelengths

- Meta-lens light-sheet fluorescence microscopy for in vivo imaging

- All-metallic high-efficiency generalized Pancharatnam–Berry phase metasurface with chiral meta-atoms

- Drawing structured plasmonic field with on-chip metalens

- Negative refraction in twisted hyperbolic metasurfaces

- Anisotropic impedance surfaces activated by incident waveform

- Machine–learning-enabled metasurface for direction of arrival estimation

- Intelligent electromagnetic metasurface camera: system design and experimental results

- High-efficiency generation of far-field spin-polarized wavefronts via designer surface wave metasurfaces

- Terahertz meta-chip switch based on C-ring coupling

- Resonance-enhanced spectral funneling in Fabry–Perot resonators with a temporal boundary mirror

- Dynamic inversion of planar-chiral response of terahertz metasurface based on critical transition of checkerboard structures

- Terahertz 3D bulk metamaterials with randomly dispersed split-ring resonators

- BST-silicon hybrid terahertz meta-modulator for dual-stimuli-triggered opposite transmission amplitude control

- Gate-tuned graphene meta-devices for dynamically controlling terahertz wavefronts

- Dual-band composite right/left-handed metamaterial lines with dynamically controllable nonreciprocal phase shift proportional to operating frequency

- Highly suppressed solar absorption in a daytime radiative cooler designed by genetic algorithm

- All-optical binary computation based on inverse design method

- Exciton-dielectric mode coupling in MoS2 nanoflakes visualized by cathodoluminescence

- Broadband wavelength tuning of electrically stretchable chiral photonic gel

- Spatio-spectral decomposition of complex eigenmodes in subwavelength nanostructures through transmission matrix analysis

- Scattering asymmetry and circular dichroism in coupled PT-symmetric chiral nanoparticles

- A large-scale single-mode array laser based on a topological edge mode

- Far-field optical imaging of topological edge states in zigzag plasmonic chains

- Omni-directional and broadband acoustic anti-reflection and universal acoustic impedance matching