Abstract

Background

Postoperative sepsis is a major type of sepsis. Sociodemographic characteristics, incidence trends, surgical procedures, comorbidities, and organ system dysfunctions related to the disease burden of postoperative sepsis episodes are unclear.

Methods

We analyzed epidemiological characteristics of postoperative sepsis based on the ICD-9-CM codes for the years 2002 to 2013 using the Longitudinal Health Insurance Databases of Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database.

Results

We identified 5,221 patients with postoperative sepsis and 338,279 patients without postoperative sepsis. The incidence of postoperative sepsis increased annually with a crude mean of 0.06% for patients aged 45–64 and 0.34% over 65 years. Patients with postoperative sepsis indicated a high risk associated with the characteristics, male sex (OR:1.375), aged 45–64 or ≥ 65 years (OR:2.639 and 5.862), low income (OR:1.390), aged township (OR:1.269), agricultural town (OR:1.266), and remote township (OR:1.205). Splenic surgery (OR:7.723), Chronic renal disease (OR:1.733), cardiovascular dysfunction (OR:2.441), and organ system dysfunctions had the highest risk of postoperative sepsis.

Conclusion

Risk of postoperative sepsis was highest among men, older, and low income. Patients with splenic surgery, chronic renal comorbidity, and cardiovascular system dysfunction exhibited the highest risk for postoperative sepsis. The evaluation of high-risk factors assists in reducing the disease burden.

1 Introduction

Sepsis is the most severe manifestation of acute infection, causing a complex syndrome that may result in multiple organ failures and resulting in death in 30–50% cases [1, 2]. Sepsis, a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, is one of the 10 leading causes of death in Taiwan and the United States [3]. The incidence of sepsis is increasing. In the United States, approximately 164,000 cases of sepsis occurred each year during the 1970s [4]. However, according to studies performed by the National Center for Health Statistics, the incidence of sepsis has risen from 221 cases per 100,000 persons in 2000 to 377 per 100,000 persons in 2008, which is an increase of 7%–8% per year [5, 6]. In Taiwan, a nationwide population-based study demonstrated that the incidence of severe sepsis rose from 135 cases per 100,000 persons in 1997 to 217 per 100,000 persons in 2006, which is an approximately 3.9% increase per year [7]. The medical cost for treating sepsis has increased along with necessity for medical equipment, medical supplies, and healthcare services associated with sepsis improvement [8].

Postoperative sepsis is defined by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality according to the Ninth Revision and Clinical Modification codes of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9-CM) [9]. It includes patients 18 years or older who have undergone surgical procedures and have had postoperative hospital stays for no fewer than 4 days [9]. The major form of sepsis is postoperative sepsis, which accounts for approximately one-third of all sepsis cases [3]. Postoperative sepsis results in significant morbidity and mortality and is a leading cause of multiple organ dysfunction and death for hospital inpatients [10, 11]. However, the understanding of the incidence and temporal trends of postoperative sepsis in Taiwan has remained limited because only a few studies have been proposed to investigate these trends. The incidence and temporal trends of postoperative sepsis are critical information for developing strategies for treatment and reducing the cost of intervention.

The primary goal of this study was to discern the incidence and temporal trends of postoperative sepsis in Taiwan using a retrospective population-based survey. The secondary objective was to compare the incidence of postoperative sepsis after surgery with respect to various types of procedures. Moreover, we evaluated sociodemographic characteristics, comorbidities, and organ system dysfunctions associated with the development of postoperative sepsis. The present study identified the high-risk population from the database because doing so might assist with identifying process-level opportunities for reducing the incidence of postoperative sepsis.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Data source

The data used in this study were collected from the Longitudinal Health Insurance Databases (LHID 2010) of the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) for the years 2002 to 2013. The NHIRD was released for research purposes by the Taiwan National Health Research Institutes and covers nearly all patient medical benefit claims for the Taiwanese population. The NHIRD, which is one of the largest and most detailed nationwide population-based datasets in the world, is widely used in epidemiological research.

2.2 Study population selection and definitions

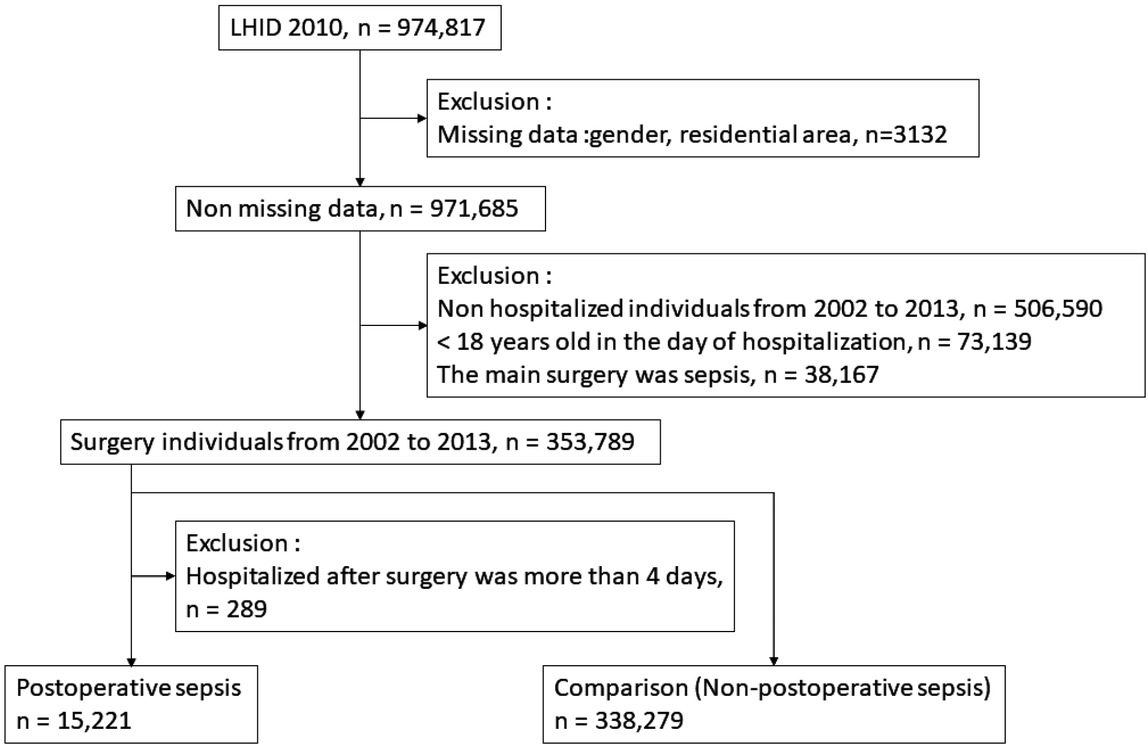

This study population comprised data regarding 974,817 patients collected from the LHID 2010 (Figure 1). Missing values for variables such as sex and residential area were excluded. Individuals who were not hospitalized, under 18 years of age, or had sepsis before surgery were also excluded. Using ICD-9-CM codes, we identified patients according to category of surgical procedure, and both hospitalized patients and surgical diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) were selected [9, 11, 12, 13]. The sepsis population was identified by secondary diagnoses using ICD-9-CM codes, namely 038, 038.0, 038.1, 038.2, 038.3, 038.4, 038.8, 038.9, 038.10, 038.11, 038.19, 038.40, 038.41, 038.42, 038.43, 038.44, 038.49, 790.7, and 996.62. In addition, all patients selected for the study had stayed in the hospital for no fewer than 4 days.

Case selection procedure

Twelve major groups of surgical procedures, according to the ICD-9-CM codes for principal procedures, were included in the data analysis, namely esophageal, pancreatic, small bowel, gastric, splenic, gallbladder, hepatic, vascular, colorectal, thoracic, cardiac, and hernia surgeries. Sociodemographic characteristics included sex, age (divided into the following age groups: 20–40, 40–65, and ≥ 65 years), income level, and urbanization level [12]. Comorbidities included carcinoma in situ (ICD-9-CM: 230–234), diabetes (ICD-9-CM: 272), chronic heart failure (ICD-9-CM: 428), unspecified hepatitis (ICD-9-CM: 070.9, 571.4, 571.8, 571.9), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD, ICD-9-CM: 490-505 506.4), chronic renal disease (ICD-9-CM: 585), and acute myocardial infarction (ICD-9-CM: 410). Organ system dysfunctions included acute renal disease (ICD-9-CM: 584, 580, 39.95) and dysfunction of the respiratory (ICD-9-CM: 518.81–518.85, 786.09, 799.1, 96.7), cardiovascular (ICD-9-CM: 785.5, 458, 796.3), hepatic (ICD-9-CM: 570, 572.2, 573.3), hematological (ICD-9-CM: 286.6, 286.9, 287.3-287.5), and metabolic (ICD-9-CM: 276.2) systems [11,13].

2.3 Statistical analysis

Incidence was estimated using the total number of LHID 2010 cases with a surgical DRG code involving patients aged 18 years or older. Age-adjusted rates were calculated using direct methods with respect to the surgical in-hospital population from 2002 to 2013. The chi-squared test was used to assess the nominal variables between patients with and without postoperative sepsis. Logistic regression was used to estimate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for patients with and without postoperative sepsis. Data analysis was performed using SAS 9.3 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and a P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

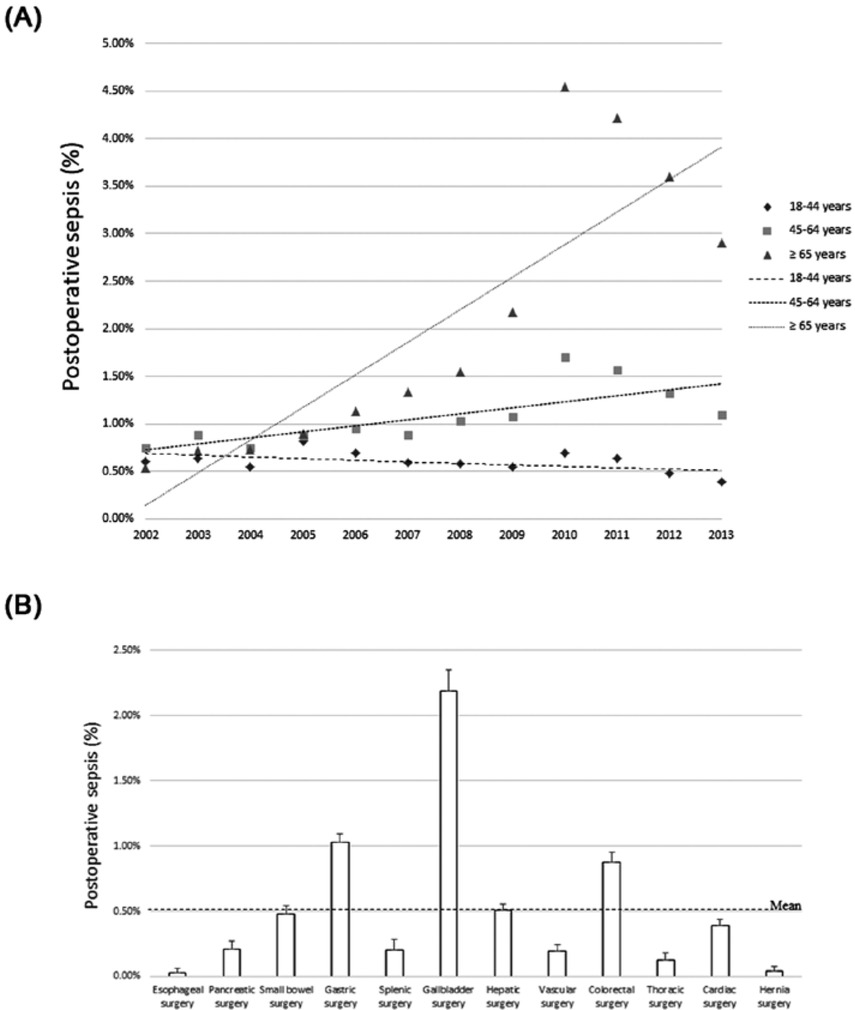

The final enrollment included 15,221 patients with postoperative sepsis and 338,279 patients without postoperative sepsis during the study period (Figure 1). The incidence of postoperative sepsis increased annually with a crude mean of 0.06% and 0.34% for patients aged 45–64 and ≥ 65 years, respectively (Figure 2A), and the incidence declined slightly with a crude mean of 0.01% for patients aged 18–44 years (Figure 2A). Figure 2B presents the average annual incidence of sepsis after various surgical procedures. Gastric, gallbladder, and colorectal surgeries were associated with a relatively high likelihood of postoperative sepsis, and esophageal surgery had the lowest risk of postoperative sepsis.

(A) Incidence of postoperative sepsis by age group (B) Incidence of postoperative sepsis by surgery type

The distribution of sociodemographic characteristics, comorbidities, and organ system dysfunctions among the study population are presented in Table 1. The differences between patients with postoperative sepsis and those without were significant with respect to sociodemographic characteristics, namely sex, age, income level, and urbanization level (P < 0.001). These differences in patients who had undergone various surgical procedures were also significant (P < 0.001), except for gallbladder surgery (P = 0.6620). In addition, the differences in patients with comorbidities were significant (P < 0.001), except for the comorbidity of carcinoma in situ (P = 0.1886).

Basic characteristics of the study participants

| Postoperative non-sepsis (n = 338279) |

Postoperative sepsis (n = 15221) |

P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | <.0001 | ||||

| female | 189467 | (56.01%) | 6834 | (44.90%) | |

| male | 148812 | (43.99%) | 8387 | (55.10%) | |

| Age | <.0001 | ||||

| 18-44 years | 222761 | (65.85%) | 3752 | (24.65%) | |

| 45-64 years | 47336 | (13.99%) | 2389 | (15.70%) | |

| ≥65 years | 68182 | (20.16%) | 9080 | (59.65%) | |

| Low income | <.0001 | ||||

| Yes | 170559 | (50.42%) | 3752 | (37.07%) | |

| No | 167720 | (49.58%) | 2389 | (62.93%) | |

| Urbanization level | <.0001 | ||||

| Highly urbanized | 98837 | (29.22%) | 3851 | (25.30%) | |

| Moderate urbanization | 100507 | (29.71%) | 4331 | (28.45%) | |

| Emerging town | 59945 | (17.72%) | 2376 | (15.61%) | |

| General town | 47102 | (13.92%) | 2429 | (15.96%) | |

| Aged Township | 6507 | (1.92%) | 504 | (3.31%) | |

| Agricultural town | 12855 | (3.8%) | 936 | (6.15%) | |

| Remote township | 12526 | (3.7%) | 794 | (5.22%) | |

| Surgical procedures | |||||

| Esophageal surgery | 65 | (0.02%) | 8 | (0.05%) | <.0001 |

| Pancreatic surgery | 98 | (0.03%) | 22 | (0.14%) | <.0001 |

| Small bowel surgery | 261 | (0.08%) | 67 | (0.44%) | <.0001 |

| Gastric surgery | 911 | (0.27%) | 141 | (0.93%) | <.0001 |

| Splenic surgery | 95 | (0.03%) | 20 | (0.13%) | <.0001 |

| Gallbladder surgery | 4789 | (1.42%) | 222 | (1.46%) | 0.6620 |

| Hepatic surgery | 809 | (0.24%) | 60 | (0.39%) | 0.0002 |

| Vascular surgery | 200 | (0.06%) | 30 | (0.20%) | <.0001 |

| Colorectal surgery | 1504 | (0.44%) | 119 | (0.78%) | <.0001 |

| Thoracic surgery | 1043 | (0.31%) | 19 | (0.12%) | <.0001 |

| Cardiac surgery | 762 | (0.23%) | 51 | (0.34%) | <.0001 |

| Hernia surgery | 6432 | (1.90%) | 12 | (0.08%) | <.0001 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Carcinoma in situ | 2988 | (0.88%) | 150 | (0.99%) | 0.1886 |

| Diabetes | 59130 | (17.48%) | 6514 | (42.80%) | <.0001 |

| Chronic heart failure | 22580 | (6.67%) | 3824 | (25.12%) | <.0001 |

| COPD | 96522 | (28.53%) | 7760 | (50.98%) | <.0001 |

| Chronic renal disease | 11755 | (3.47%) | 2451 | (16.1%) | <.0001 |

| Chronic liver disease | 280 | (0.08%) | 28 | (0.18%) | <.0001 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 3386 | (1.00%) | 483 | (3.17%) | <.0001 |

| Organ system dysfunction | |||||

| Respiratory | 16554 | (4.89%) | 2573 | (16.9%) | <.0001 |

| Cardiovascular | 5273 | (1.56%) | 1192 | (7.83%) | <.0001 |

| Acute renal disease | 2522 | (0.75%) | 532 | (3.50%) | <.0001 |

| Hepatic | 16086 | (4.76%) | 1282 | (8.42%) | <.0001 |

| Haematological | 2439 | (0.72%) | 351 | (2.31%) | <.0001 |

| Neurological | 380 | (0.11%) | 63 | (0.41%) | <.0001 |

| Metabolic | 278 | (0.08%) | 75 | (0.49%) | <.0001 |

Included postoperative sepsis and comparison: non postoperative sepsis.

Table 2 presents the logistic regression analysis of patients with and without postoperative sepsis. Adjustments were made for sex, age, income level, urbanization level, surgical procedures, comorbidities, and organ system dysfunctions. Among the sociodemographic characteristics, the results indicated a high risk of postoperative sepsis among the following categories of patients: men (OR 1.375, 95% CI 1.375–1.423), aged 45–64 and ≥ 65 years (OR 2.639 and 5.862, 95% CI 2.496–2.790 and 5.545–6.196), low income (OR 1.390, 95% CI 1.134–1.441), aged township (OR 1.269, 95% CI 1.147–1.403), agricultural town (OR 1.266, 95% CI 1.172–1.368), and remote township (OR 1.205, 95% CI 1.110–1.308). The aged township category was associated with the highest risk with respect to urbanization level for postoperative sepsis among patients. Among patients who underwent other surgical procedures, those who underwent esophageal, pancreatic, small bowel, gastric, splenic, and vascular surgeries had the highest risk of postoperative sepsis. Among these procedures, splenic surgery (OR 7.723, 95% CI 4.614–12.927) had the highest risk. The specific comorbidities and organ system dysfunctions associated with the highest risk of postoperative sepsis were diabetes, chronic heart failure, COPD, chronic renal disease, respiratory dysfunction, cardiovascular dysfunction, acute renal disease, hepatic dysfunction, hematological dysfunction, neurological dysfunction, and metabolic dysfunction. Patients with chronic renal disease (OR 1.733, 95% CI 1.644–1.827) and cardiovascular dysfunction (OR 2.441, 95% CI 2.272–2.622) had the highest risks among comorbidities and organ system dysfunctions, respectively. These results indicated that patients who were men, older adults, lived in an aged township, had undergone splenic surgery, or had received a diagnosis of chronic renal disease or cardiovascular dysfunction had a relatively high risk of postoperative sepsis.

Odds ratio and 95% confidence interval of surgery among patients with sepsis

| Odds ratio (95%CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (reference: female) | ||

| Male | 1.375 (1.328-1.423) | <.0001 |

| Age (reference: 18-44 years old) | ||

| 40-64 years | 2.639 (2.496-2.790) | <.0001 |

| ≥ 65 years | 5.862 (5.545-6.196) | <.0001 |

| Low income (reference : no) | ||

| Yes | 1.390 (1.34-1.441) | <.0001 |

| Urbanization level (reference:Moderate urbanization) | ||

| Highly urbanized | 0.937 (0.895-0.981) | 0.0056 |

| Emerging town | 0.938 (0.890-0.989) | 0.0181 |

| General town | 1.037 (0.983-1.094) | 0.1876 |

| Aged township | 1.269 (1.147-1.403) | <.0001 |

| Agricultural town | 1.266 (1.172-1.368) | <.0001 |

| Remote township | 1.205 (1.110-1.308) | <.0001 |

| Surgical procedures (reference: other surgery) | ||

| Esophageal surgery | 2.668 (1.217-5.847) | 0.0143 |

| Pancreatic surgery | 4.045 (2.466-6.635) | <.0001 |

| Small bowel surgery | 4.242 (3.170-5.675) | <.0001 |

| Gastric surgery | 2.927 (2.420-3.539) | <.0001 |

| Splenic surgery | 7.723 (4.614-12.927) | <.0001 |

| Gallbladder surgery | 1.032 (0.898-1.186) | 0.6583 |

| Hepatic surgery | 1.168 (0.890-1.534) | 0.2636 |

| Vascular surgery | 1.962 (1.305-2.949) | 0.0012 |

| Colorectal surgery | 1.184 (0.976-1.437) | 0.0862 |

| Thoracic surgery | 0.431 (0.272-0.683) | 0.0003 |

| Cardiac surgery | 0.763 (0.569-1.022) | 0.0696 |

| Hernia surgery | 0.034 (0.019-0.060) | <.0001 |

| Comorbidities (reference: without) | ||

| Carcinoma in situ | 0.830 (0.699-0.985) | 0.0332 |

| Diabetes | 1.494 (1.439-1.550) | <.0001 |

| Chronic heart failure | 1.414 (1.351-1.480) | <.0001 |

| COPD | 1.149 (1.107-1.192) | <.0001 |

| Chronic renal disease | 1.733 (1.644-1.827) | <.0001 |

| Chronic live disease | 0.568 (0.373-0.863) | 0.0081 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 1.045 (0.939-1.163) | 0.4193 |

| Organ system dysfunction (reference: without) | ||

| Respiratory | 1.785 (1.697-1.877) | <.0001 |

| Cardiovascular | 2.441 (2.272-2.622) | <.0001 |

| Acute renal disease | 1.573 (1.416-1.747) | <.0001 |

| Hepatic | 1.194 (1.121-1.271) | <.0001 |

| Haematological | 1.699 (1.504-1.919) | <.0001 |

| Neurological | 1.140 (0.858-1.514) | 0.3665 |

| Metabolic | 1.667 (1.259-2.206) | 0.3665 0.0004 |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval, COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Table 3 presents the sociodemographic characteristics and risk of postoperative sepsis in each of the predefined age groups, which were 18–44, 45–64, and ≥65 years old. In the 18–44 age group, the following characteristics of patients were associated with a relatively high risk of postoperative sepsis: male sex, low income, remote township, pancreatic surgery, diabetes, and cardiovascular dysfunction. In the 45–64 age group, the high-risk characteristics of patients associated with postoperative sepsis were male sex, low income, aged township, small bowel surgery, chronic renal disease, and cardiovascular dysfunction. In the ≥65 age group, the high-risk characteristics postoperative sepsis were male sex, low income, agricultural town, splenic surgery, chronic renal disease, and cardiovascular dysfunction.

Odds ratio and 95% confidence interval of surgery among patients with sepsis in each of the predefined age groups

| Odds ratio (95%CI) 18-44 years (n=2008) |

45-64 years (n=4133) | ≥ 65 years (n=9080) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (reference: female) | ||||||

| Male | 1.469 (1.343-1.608) | *** | 1.585 (1.484-1.692) | *** | 1.234 (1.179-1.291) | *** |

| Low income (reference : no) | ||||||

| Yes | 1.219 (1.114-1.333) | *** | 1.635 (1.534-1.743) | *** | 1.273 (1.206-1.344) | *** |

| Urbanization level (reference: Moderate urbanization) | ||||||

| Highly urbanized | 0.952 (0.847-1.069) | 0.937 (0.862-1.019) | 0.940 (0.883-1.001) | |||

| Emerging town | 0.923 (0.808-1.053) | 0.958 (0.869-1.056) | 0.920 (0.856-0.989) | * | ||

| General town | 0.963 (0.830-1.118) | 0.983 (0.886-1.090) | 1.032 (0.961-1.108) | |||

| Aged Township | 1.016 (0.701-1.472) | 1.636 (1.336-2.002) | *** | 1.126 (0.994-1.275) | ||

| Agricultural town | 1.406 (1.120-1.765) | ** | 1.352 (1.161-1.574) | ** | 1.141 (1.033-1.260) | ** |

| Remote township | 1.466 (1.181-1.820) | ** | 1.365 (1.168-1.596) | *** | 1.041 (0.934-1.160) | |

| Surgical procedures (reference: other surgery) | ||||||

| Esophageal surgery | 2.588 (0.338-19.815) | 3.166 (1.112-9.017) | * | 2.094 (0.530-8.283) | ||

| Pancreatic surgery | 11.497 (3.870-34.159) | *** | 4.900 (2.313-10.378) | *** | 2.528 (1.181-5.410) | * |

| Small bowel surgery | 9.715 (4.873-19.365) | *** | 6.701 (4.127-10.880) | *** | 2.673 (1.796-3.978) | *** |

| Gastric surgery | 2.569 (1.460-4.521) | ** | 2.424 (1.695-3.466) | *** | 3.141 (2.451-4.025) | *** |

| Splenic surgery | 9.534 (4.646-19.565) | *** | 6.371 (2.726-14.890) | *** | 4.042 (1.030-15.863) | * |

| Gallbladder surgery | 0.393 (0.195-0.789) | ** | 0.957 (0.758-1.208) | 1.223 (1.019-1.467) | * | |

| Hepatic surgery | 1.710 (0.665-4.397) | 1.643 (1.102-2.450) | * | 0.861 (0.579-1.282) | ||

| Vascular surgery | 7.714 (2.341-25.418) | ** | 2.801 (1.442-5.439) | ** | 1.374 (0.793-2.381) | |

| Colorectal surgery | 4.876 (2.687-8.850) | *** | 1.326 (0.934-1.883) | 0.967 (0.756-1.238) | ||

| Thoracic surgery | 0.596 (0.222-1.601) | 0.408 (0.168-0.990) | * | 0.402 (0.212-0.761) | ** | |

| Cardiac surgery | 5.701 (2.897-11.22) | *** | 0.515 (0.273-0.973) | * | 0.661 (0.454-0.962) | * |

| Hernia surgery | 0.042 (0.006-0.298) | ** | 0.030 (0.010-0.093) | *** | 0.035 (0.017-0.070) | *** |

| Comorbidities (reference: without) | ||||||

| Carcinoma in situ | 0.865 (0.428-1.747) | 0.789 (0.557-1.119) | 0.867 (0.706-1.064) | |||

| Diabetes | 2.780 (2.432-3.179) | *** | 1.743 (1.628-1.865) | *** | 1.274 (1.217-1.333) | *** |

| Chronic heart failure | 1.903 (1.416-2.557) | *** | 1.465 (1.319-1.626) | *** | 1.377 (1.309-1.448) | *** |

| COPD | 1.021 (0.912-1.143) | 1.041 (0.972-1.115) | 1.231 (1.173-1.292) | *** | ||

| Chronic renal disease | 2.682 (2.015-3.569) | *** | 2.456 (2.206-2.735) | *** | 1.559 (1.467-1.657) | *** |

| Chronic liver disease | 1.187 (0.104-13.506) | 0.649 (0.250-1.679) | 0.546 (0.341-0.873) | * | ||

| Acute myocardial infarction | 1.422 (0.645-3.133) | 0.924 (0.729-1.172) | 1.091 (0.968-1.231) | |||

| Organ system dysfunction (reference: without) | ||||||

| Respiratory | 1.714 (1.404-2.093) | *** | 1.732 (1.554-1.931) | *** | 1.783 (1.681-1.892) | *** |

| Cardiovascular | 4.668 (3.739-5.827) | *** | 2.998 (2.590-3.470) | *** | 2.116 (1.942-2.305) | *** |

| Acute renal disease | 2.271 (1.490-3.460) | ** | 1.723 (1.388-2.139) | *** | 1.458 (1.289-1.648) | *** |

| Hepatic | 1.723 (1.440-2.061) | *** | 1.358 (1.222-1.510) | *** | 0.990 (0.908-1.079) | |

| Haematological | 3.953 (2.808-5.565) | *** | 2.654 (2.141-3.290) | *** | 1.242 (1.061-1.453) | ** |

| Neurological | 3.037 (1.057-8.729) | * | 2.275 (1.259-4.112) | ** | 0.936 (0.672-1.304) | |

| Metabolic | 2.178 (0.817-5.804) | 1.425 (0.838-2.425) | 1.603 (1.137-2.261) | ** | ||

-

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval, COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

* *, **, *** Statistically significant, respectively P <0.05, P <0.01, P <0.0001.

4 Discussion

Taiwan launched the National Health Insurance (NHI) program in March 1995 to provide single-payer health insurance to residents of Taiwan; now, the NHI covers more than 99% of the population and enables them to easily access affordable healthcare with only a small copayment required at most clinics and hospitals. To the best of our knowledge, a retrospective and longitudinal nationwide study of postoperative sepsis has not been undertaken in Taiwan. However, nationwide databases have been used widely in the United States to identify the changes over time concerning the incidence, epidemiological characteristics, and temporal trends in postoperative sepsis in the country [11, 15]. The incidence of postoperative sepsis in the United States increased from 4.41% in 1990 to 6.25% in 2006 according to the Nationwide Inpatient Sample dataset [14]. The same study also demonstrated that the incidence of postoperative sepsis was 3.4% among those aged 18–49 years but 6.9% among those aged ≥80 years [14]. No evidence has been compiled and analyzed to assess the incidence of postoperative sepsis in Taiwan. However, one study analyzed data gathered from the NHIRD and determined the incidence of sepsis had increased from 637.8 per 100,000 persons in 2002 to 772.1 per 100,000 persons in 2012 [16]; the study also discovered that the incidence of sepsis in older adults (aged ≥65 years) was 10-fold higher than in younger adults (18–64 years) of the same sex [16]. In the present study, we determined that the incidence of postoperative sepsis increased from 1.90% in 2002 to 4.40% in 2013. Older adults (≥65 years) had a greater increase in incidence of postoperative sepsis than did middle-aged patients (45–64 years); however, the incidence of postoperative sepsis in younger (18–44 years) patients decreased slightly over the same period. This finding may imply that the senescence of older adult patients’ organs results in their higher incidence of postoperative sepsis.

The average annual incidence of sepsis with respect to a variety of surgical procedures is presented in Figure 2. We discovered higher incidences of sepsis associated with gastric, gallbladder, and colorectal surgeries; however, no statistically significant difference was evident with respect to the incidence of sepsis after undergoing gallbladder surgery. These results indicated that the number of patients who underwent gallbladder surgery was the largest among all the surgical procedures and thus led to the highest average annual incidence of sepsis after surgery. These findings were similar to those regarding the average annual incidence of sepsis after colorectal surgeries. Moreover, we determined that patients had a higher likelihood of developing sepsis after undergoing general abdominal surgeries such as splenic, small bowel, pancreatic, gastric, and esophageal surgeries. The basic rule in abdominal surgeries is to have an incision that offers the appropriate passageway to the region in the abdominal organ or tissue which suffered damage through injury or disease [17]. Pathologists have hypothesised that patients have higher risk of sepsis via microbial infection after spleens are processed as surgical specimens, splenic implants, or spleen removal surgery [18].

After performing the surgical removal of all or part of the pancreas, an increased the risk for the development of sepsis was found [19]. After radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer, post-operative infection is the most common complication via leukocyte depletion in transfusion patient [20]. Postoperative infection is the lethal and hospitalized factor in patients who underwent lower gastrointestinal surgery of the small intestine, colon, rectum, or anus in Unit State [21]. Studies had shown that patients who underwent surgical esophagectomy had a high risk of postoperative complications such as sepsis and high mortality [22]. These findings were similar to those discovered by researchers in the United States, indicating that the highest risks of postoperative sepsis with respect to general abdominal procedures were associated with esophageal, gastric, pancreatic, small bowel, and biliary surgeries [11]. And intra-abdominal infection is a common cause of open laparotomy in non-traumatic patients [23]. This study identified that pancreatic, small bowel, and splenic surgeries were associated with higher risks among patients aged 18–44, 45–64, and ≥65 years, respectively. In addition, there is much evidence claiming that postoperative sepsis was found in patients after an uncomplicated colonoscopic polypectomy, which is regarded as a safe procedure, due to unidentified abdominal infections [24, 25]. These results suggest that general abdominal procedures, including not only complex surgeries but also routine procedures, pose a significant risk for the development of postoperative sepsis.

Our logistic regression analysis demonstrated that several sociodemographic characteristics of the patients influenced their risk of postoperative sepsis. Being male or older (≥65 years) considerably increased the risk of developing postoperative sepsis; the elevated risk associated with these factors has been consistently reported in other epidemiological studies of sepsis [16, 26, 27] and postoperative sepsis [14, 15]. Sex hormones play a major role in shaping the host’s response to sepsis [28, 29, 30]. Older patients may have an increased risk of postoperative sepsis because of declining immune system performance and age-associated immunosenescence [31, 32]. Thus, our evidence lends support to the contention that male sex and older age may play key roles in the development of postoperative sepsis because of the regulation of the expression of sex hormones and defective immunological function, respectively.

Several possible comorbidities and organ system dysfunctions were associated with an increased incidence of postoperative sepsis. The comorbidities of chronic renal disease, diabetes, and chronic heart failure were associated with the first, second, and third highest risks, respectively, of patients developing postoperative sepsis. In addition, chronic renal disease, diabetes, and chronic heart failure were associated with a higher likelihood of developing postoperative sepsis among all age groups. Similar to the findings of other studies, the aforementioned chronic comorbidities increased the likelihood of sepsis [33, 34, 35]. A possible reason for patients with these three chronic comorbidities to have a higher risk of developing postoperative sepsis could be because they are each related to an inflammatory response that results in fewer and worse functioning leukocytes. Such evidence suggests that these three chronic comorbidities might play major roles in the development of postoperative sepsis attributable to the generation of inflammation and immune system dysfunction.

Organ system dysfunction was analyzed for all patients and age groups, and cardiovascular and hematological system dysfunctions were associated with the highest likelihood of developing postoperative sepsis. Organ system dysfunction was also associated with increased risk of sepsis [13]. These findings supported the findings of other studies that cardiovascular and hematological systems play major roles in the development of postoperative sepsis.

5 Limitations of the study

The present study has several limitations. The LHID 2010 and NHIRD are derived from a large administrative database. Although many studies have validated the use of this administrative data [11, 13], the data were originally intended for claims reimbursements and thus lack detailed biochemical data for each individual. Moreover, a statistical bias attributable to the coding schemes related to the limitations of various clinical entities cannot be entirely excluded; for example, they may have failed to accurately differentiate comorbidities from chronic diseases and organ system dysfunctions [11, 13, 15]. Some comorbidities or organ system dysfunctions may have been missed because only five diagnostic ICD-9-CM codes were assessed, which may have resulted in an underestimation of the incidence. An intrinsic bias may be attributable to the use of the ICD-9-CM discharge code, which may have been applied differently between and even within institutions.

6 Conclusions

The factors related to increased incidences of postoperative sepsis in our study were similar to those in studies undertaken in the United States. After general abdominal surgeries, namely splenic, small bowel, pancreatic, gastric, and esophageal surgeries, patients had a higher likelihood of developing sepsis. Patients who were male and older exhibited a considerably higher risk of developing postoperative sepsis than patients in other categories. Chronic renal disease, diabetes, chronic heart failure, and organ system dysfunction, including cardiovascular and hematological system dysfunction, were associated with a higher risk of developing postoperative sepsis in both the differential age groups and all patients. The key finding of this study was the valuable predictors associated with an increased risk of developing postoperative sepsis; these predictors, namely being male or older, undergoing splenic surgery, and having chronic renal comorbidities or cardiovascular system dysfunction, present a potential target for future research to reduce the disease burden.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work

References

[1] Angus DC, van der Poll T. Severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(9): 840-851.10.1056/NEJMra1208623Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Engel C, Brunkhorst FM, Bone HG, et al. Epidemiology of sepsis in Germany: results from a national prospective multicenter study. Intensive Care Med 2007; 33(4): 606–618.10.1007/s00134-006-0517-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Anderson RN, Smith BL. Deaths: leading causes for 2002. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2005; 53(17): 1–89.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Shubin H, Weil MH, Bacterial shock. JAMA 1976; 235(4): 421-424.10.1001/jama.1976.03260300045034Search in Google Scholar

[5] Lagu T, Rothberg MB, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Steingrub JS, Lindenauer PK. Hospitalizations, costs, and outcomes of severe sepsis in the United States 2003 to 2007. Crit Care Med 2012; 40(3): 754-761.10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232db65Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Hall MJ, Williams SN, DeFrances CJ, Golosinskiy A. Inpatient care for septicemia or sepsis: a challenge for patients and hospitals. NCHS Data Brief 2011; (62): 1–8.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Shen HN, Lu CL, Yang HH. Epidemiologic trend of severe sepsis in Taiwan from 1997 through 2006. Chest 2010; 138(2): 298–304.10.1378/chest.09-2205Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Rhee C, Gohil S, Klompas M. Regulatory mandates for sepsis care-reasons for caution. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(18): 1673–167610.1056/NEJMp1400276Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). AHRQ Quality Indicators™ (AHRQ QI™) ICD-9-CM Specification Version 6.0. 2017. https://www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/Downloads/Modules/PSI/V60-ICD09/TechSpecs/PSI_13_Postoperative_Sepsis_Rate.pdfSearch in Google Scholar

[10] Finks JF, Osborne NH, Birkmeyer JD. Trends in hospital volume and operative mortality for high-risk surgery. N Engl J Med 2011; 364(2): 2128-213710.1056/NEJMsa1010705Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Vogel TR, Dombrovskiy, VY, Carson JL, Graham AM, Lowry SF. Postoperative sepsis in the United States. Ann Surg 2010; 252(6): 1065-107110.1097/SLA.0b013e3181dcf36eSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Liu CY, Hung YT, Chuang YL, et al. Incorporating development stratification of Taiwan townships into sampling design of large scale health interview survey. J Health Manage 2006; 4: 1-22Search in Google Scholar

[13] Bouza C, López-Cuadrado T, Amate-Blanco JM. Characteristics, incidence and temporal trends of sepsis in elderly patients undergoing surgery. Br J Surg. 2016; 103(2): e73-8210.1002/bjs.10065Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Fried E, Weissman C, Sprung C. Postoperative sepsis. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2011;17(4): 396-40110.1097/MCC.0b013e328348bee2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Vogel TR, Dombrovskiy VY, Lowry SF. Trends in postoperative sepsis: are we improving outcomes? Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2009; 10(1): 71-7810.1089/sur.2008.046Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Bateman BT, Schmidt U, Berman MF, Bittner EA. Temporal trends in the epidemiology of severe postoperative sepsis after elective surgery: a large, nationwide sample. Anesthesiology. 2010; 112(4): 917-92510.1097/ALN.0b013e3181cea3d0Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Abdominal incisions in general surgery: a review. Ann Ib Postgrad Med 2007; 5(2): 59-63Search in Google Scholar

[18] Hansen K, Singer DB. Asplenic-hyposplenic overwhelming sepsis: postsplenectomy sepsis revisited. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2001; 4(2): 105-12110.1007/s100240010145Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Wancata LM, Abdelsattar ZM, Suwanabol PA, Campbell DA Jr, Hendren S. Intra-abdominal sepsis following pancreatic resection: incidence, risk factors, diagnosis, microbiology, management, and outcome. J Gastrointest Surg 2017; 21(2): 363-37110.1007/s11605-016-3307-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Xiao H, Quan H, Pan S, et al. Impact of peri-operative blood transfusion on post-operative infections after radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a propensity score matching analysis focusing on the timing, amount of transfusion and role of leukocyte depletion. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2018; 144(6): 1143-115410.1007/s00432-018-2630-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Liang H, Jiang B, Manne S, Lissoos T, Bennett D, Dolin P. Risk factors for postoperative infection after gastrointestinal surgery among adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease: Findings from a large observational US cohort study. JGH Open 2018 Aug 23;2(5):182-19010.1002/jgh3.12072Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Verhage RJ, Hazebroek EJ, Boone J, Van Hillegersberg R. Minimally invasive surgery compared to open procedures in esophagectomy for cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Minerva Chir 2009; 64(2): 135-146Search in Google Scholar

[23] Kritayakirana K, M Maggio P, Brundage S, Purtill MA, Staudenmayer K, A Spain D. Outcomes and complications of open abdomen technique for managing non-trauma patients. J Emerg Trauma Shock 2010; 3(2): 118-12210.4103/0974-2700.62106Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Gioia S, Lancia M, Mencacci A, Bacci M, Suadoni F. Fatal Clostridium perfringens Septicemia After Colonoscopic Polypectomy, Without Bowel Perforation. J Forensic Sci. 2016; 61(6):1689-169210.1111/1556-4029.13197Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Boenicke L, Maier M, Merger M, et al. Retroperitoneal gas gangrene after colonoscopic polypectomy without bowel perforation in an otherwise healthy individual: report of a case. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2006; 391(2):157-16010.1007/s00423-005-0019-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Lee CC, Yo CH, Lee MG, et al. Adult sepsis - A nationwide study of trends and outcomes in a population of 23 million people. J Infect 2017; 75(5):409-41910.1016/j.jinf.2017.08.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J. Pinsky MR. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: Analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med 2001; 29(7): 1303-131010.1097/00003246-200107000-00002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Williams MD, Braun LA, Cooper LM, et al. Hospitalized cancer patients with severe sepsis: analysis of incidence, mortality, and associated costs of care. Crit Care 2004; 8(5):R291-29810.1186/cc2893Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Feng JY, Liu KT, Abraham E, et al. Serum estradiol levels predict survival and acute kidney injury in patients with septic shock--a prospective study. PLoS One 2014; 9(6): e9796710.1371/journal.pone.0097967Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] van Vught LA, Scicluna BP, Wiewel MA, et al. Association of Gender With Outcome and Host Response in Critically Ill Sepsis Patients. Crit Care Med 2017; 45(11): 1854-186210.1097/CCM.0000000000002649Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Tsang G, Insel MB, Weis JM, et al. Bioavailable estradiol concentrations are elevated and predict mortality in septic patients: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care 2016; 20(1): 33510.1186/s13054-016-1525-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Merz TM, Pereira AJ, Schürch R, et al. Mitochondrial function of immune cells in septic shock: A prospective observational cohort study. PLoS One 2017; 12(6): e017894610.1371/journal.pone.0178946Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Tejera D, Varela F, Acosta D, et al. Epidemiology of acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease in the intensive care unit. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva 2017; 29(4): 444-45210.5935/0103-507X.20170061Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Frydrych LM, Fattahi F, He K, Ward PA, Delano MJ. Diabetes and Sepsis: Risk, Recurrence, and Ruination. Front Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2017; 8: 27110.3389/fendo.2017.00271Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Sergi C, Shen F, Lim DW, et al. Cardiovascular dysfunction in sepsis at the dawn of emerging mediators. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017; 95: 153-16010.1016/j.biopha.2017.08.066Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2019 Po-Yi Chen et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Article

- Prostate Cancer-Specific of DD3-driven oncolytic virus-harboring mK5 gene

- Case Report

- Pediatric acute paradoxical cerebral embolism with pulmonary embolism caused by extremely small patent foramen ovale

- Research Article

- Associations between ambient temperature and acute myocardial infarction

- Case Report

- Discontinuation of imatinib mesylate could improve renal impairment in chronic myeloid leukemia

- Research Article

- METTL3 promotes the proliferation and mobility of gastric cancer cells

- The C677T polymorphism of the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene and susceptibility to late-onset Alzheimer’s disease

- microRNA-1236-3p regulates DDP resistance in lung cancer cells

- Review Article

- The link between thyroid autoimmunity, depression and bipolar disorder

- Research Article

- Effects of miR-107 on the Chemo-drug sensitivity of breast cancer cells

- Analysis of pH dose-dependent growth of sulfate-reducing bacteria

- Review Article

- Musculoskeletal clinical and imaging manifestations in inflammatory bowel diseases

- Research Article

- Regional hyperthermia combined with chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer

- Analysis of hormone receptor status in primary and recurrent breast cancer via data mining pathology reports

- Morphological and isokinetic strength differences: bilateral and ipsilateral variation by different sport activity

- The reliability of adjusting stepped care based on FeNO monitoring for patients with chronic persistent asthma

- Comparison of the clinical outcomes of two physiological ischemic training methods in patients with coronary heart disease

- Analysis of ticagrelor’s cardio-protective effects on patients with ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome accompanied with diabetes

- Computed tomography findings in patients with Samter’s Triad: an observational study

- Case Report

- A spinal subdural hematoma induced by guidewire-based lumbar drainage in a patient with ruptured intracranial aneurysms

- Research Article

- High expression B3GAT3 is related with poor prognosis of liver cancer

- Effects of light touch on balance in patients with stroke

- Oncoprotein LAMTOR5 activates GLUT1 via upregulating NF-κB in liver cancer

- Effects of budesonide combined with noninvasive ventilation on PCT, sTREM-1, chest lung compliance, humoral immune function and quality of life in patients with AECOPD complicated with type II respiratory failure

- Prognostic significance of lymph node ratio in ovarian cancer

- Case Report

- Brainstem anaesthesia after retrobulbar block

- Review Article

- Treating infertility: current affairs of cross-border reproductive care

- Research Article

- Serum inflammatory cytokines comparison in gastric cancer therapy

- Behavioural and psychological symptoms in neurocognitive disorders: Specific patterns in dementia subtypes

- MRI and bone scintigraphy for breast cancer bone metastase: a meta-analysis

- Comparative study of back propagation artificial neural networks and logistic regression model in predicting poor prognosis after acute ischemic stroke

- Analysis of the factors affecting the prognosis of glioma patients

- Compare fuhrman nuclear and chromophobe tumor grade on chromophobe RCC

- Case Report

- Signet ring B cell lymphoma: A potential diagnostic pitfall

- Research Article

- Subparaneural injection in popliteal sciatic nerve blocks evaluated by MRI

- Loneliness in the context of quality of life of nursing home residents

- Biological characteristics of cervical precancerous cell proliferation

- Effects of Rehabilitation in Bankart Lesion in Non-athletes: A report of three cases

- Management of complications of first instance of hepatic trauma in a liver surgery unit: Portal vein ligation as a conservative therapeutic strategy

- Matrix metalloproteinase 2 knockdown suppresses the proliferation of HepG2 and Huh7 cells and enhances the cisplatin effect

- Comparison of laparoscopy and open radical nephrectomy of renal cell cancer

- Case Report

- A severe complication of myocardial dysfunction post radiofrequency ablation treatment of huge hepatic hemangioma: a case report and literature review

- Solar urticaria, a disease with many dark sides: is omalizumab the right therapeutic response? Reflections from a clinical case report

- Research Article

- Binge eating disorder and related features in bariatric surgery candidates

- Propofol versus 4-hydroxybutyric acid in pediatric cardiac catheterizations

- Nasointestinal tube in mechanical ventilation patients is more advantageous

- The change of endotracheal tube cuff pressure during laparoscopic surgery

- Correlation between iPTH levels on the first postoperative day after total thyroidectomy and permanent hypoparathyroidism: our experience

- Case Report

- Primary angiosarcoma of the kidney: case report and comprehensive literature review

- Research Article

- miR-107 enhances the sensitivity of breast cancer cells to paclitaxel

- Incidental findings in dental radiology are concerning for family doctors

- Suffering from cerebral small vessel disease with and without metabolic syndrome

- A meta-analysis of robot assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy versus laparoscopic radical prostatectomy

- Indications and outcomes of splenectomy for hematological disorders

- Expression of CENPE and its prognostic role in non-small cell lung cancer

- Barbed suture and gastrointestinal surgery. A retrospective analysis

- Using post transplant 1 week Tc-99m DTPA renal scan as another method for predicting renal graft failure

- The pseudogene PTTG3P promotes cell migration and invasion in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- Lymph node ratio versus TNM system as prognostic factor in colorectal cancer staging. A single Center experience

- Review Article

- Minimally invasive pilonidal sinus treatment: A narrative review

- Research Article

- Anatomical workspace study of Endonasal Endoscopic Transsphenoidal Approach

- Hounsfield Units on Lumbar Computed Tomography for Predicting Regional Bone Mineral Density

- Communication

- Aspirin, a potential GLUT1 inhibitor in a vascular endothelial cell line

- Research Article

- Osteopontin and fatty acid binding protein in ifosfamide-treated rats

- Familial polyposis coli: the management of desmoid tumor bleeding

- microRNA-27a-3p down-regulation inhibits malignant biological behaviors of ovarian cancer by targeting BTG1

- PYCR1 is associated with papillary renal cell carcinoma progression

- Prediction of recurrence-associated death from localized prostate cancer with a charlson comorbidity index–reinforced machine learning model

- Colorectal cancer in the elderly patient: the role of neo-adjuvant therapy

- Association between MTHFR genetic polymorphism and Parkinson’s disease susceptibility: a meta-analysis

- Metformin can alleviate the symptom of patient with diabetic nephropathy through reducing the serum level of Hcy and IL-33

- Case Report

- Severe craniofacial trauma after multiple pistol shots

- Research Article

- Echocardiography evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function in elderly women with metabolic syndrome

- Tailored surgery in inguinal hernia repair. The role of subarachnoid anesthesia: a retrospective study

- The factors affecting early death in newly diagnosed APL patients

- Review Article

- Oncological outcomes and quality of life after rectal cancer surgery

- Research Article

- MiR-638 repressed vascular smooth muscle cell glycolysis by targeting LDHA

- microRNA-16 via Twist1 inhibits EMT induced by PM2.5 exposure in human hepatocellular carcinoma

- Analyzing the semantic space of the Hippocratic Oath

- Fournier’s gangrene and intravenous drug abuse: an unusual case report and review of the literature

- Evaluation of surgical site infection in mini-invasive urological surgery

- Dihydromyricetin attenuates inflammation through TLR4/NF-kappaB pathway

- Clinico-pathological features of colon cancer patients undergoing emergency surgery: a comparison between elderly and non-elderly patients

- Case Report

- Appendix bleeding with painless bloody diarrhea: A case report and literature review

- Research Article

- Protective effects of specneuzhenide on renal injury in rats with diabetic nephropathy

- PBF, a proto-oncogene in esophageal carcinoma

- Use of rituximab in NHL malt type pregnant in I° trimester for two times

- Cancer- and non-cancer related chronic pain: from the physiopathological basics to management

- Case report

- Non-surgical removal of dens invaginatus in maxillary lateral incisor using CBCT: Two-year follow-up case report

- Research Article

- Risk factors and drug resistance of the MDR Acinetobacter baumannii in pneumonia patients in ICU

- Accuracy of tumor perfusion assessment in Rat C6 gliomas model with USPIO

- Lemann Index for Assessment of Crohn’s Disease: Correlation with the Quality of Life, Endoscopic Disease activity, Magnetic Resonance Index of Activity and C- Reactive Protein

- Case report

- Münchausen syndrome as an unusual cause of pseudo-resistant hypertension: a case report

- Research Article

- Renal artery embolization before radical nephrectomy for complex renal tumour: which are the true advantages?

- Prognostic significance of CD276 in non-small cell lung cancer

- Potential drug-drug interactions in acute ischemic stroke patients at the Neurological Intensive Care Unit

- Effect of vitamin D3 on lung damage induced by cigarette smoke in mice

- CircRNA-UCK2 increased TET1 inhibits proliferation and invasion of prostate cancer cells via sponge miRNA-767-5p

- Case report

- Partial hydatidiform mole and coexistent live fetus: a case report and review of the literature

- Research Article

- Effect of NGR1 on the atopic dermatitis model and its mechanisms

- Clinical features of infertile men carrying a chromosome 9 translocation

- Review Article

- Expression and role of microRNA-663b in childhood acute lymphocytic leukemia and its mechanism

- Case Report

- Mature cystic teratoma of the pancreas: A rare cystic neoplasm

- Research Article

- Application of exercised-based pre-rehabilitation in perioperative period of patients with gastric cancer

- Case Report

- Predictive factors of intestinal necrosis in acute mesenteric ischemia

- Research Article

- Application of exercised-based pre-rehabilitation in perioperative period of patients with gastric cancer

- Effects of dexmedetomidine on the RhoA /ROCK/ Nox4 signaling pathway in renal fibrosis of diabetic rats

- MicroRNA-181a-5p regulates inflammatory response of macrophages in sepsis

- Intraventricular pressure in non-communicating hydrocephalus patients before endoscopic third ventriculostomy

- CyclinD1 is a new target gene of tumor suppressor miR-520e in breast cancer

- CHL1 and NrCAM are primarily expressed in low grade pediatric neuroblastoma

- Epidemiological characteristics of postoperative sepsis

- Association between unstable angina and CXCL17: a new potential biomarker

- Cardiac strains as a tool for optimization of cardiac resynchronization therapy in non-responders: a pilot study

- Case Report

- Resuscitation following a bupivacaine injection for a cervical paravertebral block

- Research Article

- CGF treatment of leg ulcers: A randomized controlled trial

- Surgical versus sequential hybrid treatment of carotid body tumors

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Article

- Prostate Cancer-Specific of DD3-driven oncolytic virus-harboring mK5 gene

- Case Report

- Pediatric acute paradoxical cerebral embolism with pulmonary embolism caused by extremely small patent foramen ovale

- Research Article

- Associations between ambient temperature and acute myocardial infarction

- Case Report

- Discontinuation of imatinib mesylate could improve renal impairment in chronic myeloid leukemia

- Research Article

- METTL3 promotes the proliferation and mobility of gastric cancer cells

- The C677T polymorphism of the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene and susceptibility to late-onset Alzheimer’s disease

- microRNA-1236-3p regulates DDP resistance in lung cancer cells

- Review Article

- The link between thyroid autoimmunity, depression and bipolar disorder

- Research Article

- Effects of miR-107 on the Chemo-drug sensitivity of breast cancer cells

- Analysis of pH dose-dependent growth of sulfate-reducing bacteria

- Review Article

- Musculoskeletal clinical and imaging manifestations in inflammatory bowel diseases

- Research Article

- Regional hyperthermia combined with chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer

- Analysis of hormone receptor status in primary and recurrent breast cancer via data mining pathology reports

- Morphological and isokinetic strength differences: bilateral and ipsilateral variation by different sport activity

- The reliability of adjusting stepped care based on FeNO monitoring for patients with chronic persistent asthma

- Comparison of the clinical outcomes of two physiological ischemic training methods in patients with coronary heart disease

- Analysis of ticagrelor’s cardio-protective effects on patients with ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome accompanied with diabetes

- Computed tomography findings in patients with Samter’s Triad: an observational study

- Case Report

- A spinal subdural hematoma induced by guidewire-based lumbar drainage in a patient with ruptured intracranial aneurysms

- Research Article

- High expression B3GAT3 is related with poor prognosis of liver cancer

- Effects of light touch on balance in patients with stroke

- Oncoprotein LAMTOR5 activates GLUT1 via upregulating NF-κB in liver cancer

- Effects of budesonide combined with noninvasive ventilation on PCT, sTREM-1, chest lung compliance, humoral immune function and quality of life in patients with AECOPD complicated with type II respiratory failure

- Prognostic significance of lymph node ratio in ovarian cancer

- Case Report

- Brainstem anaesthesia after retrobulbar block

- Review Article

- Treating infertility: current affairs of cross-border reproductive care

- Research Article

- Serum inflammatory cytokines comparison in gastric cancer therapy

- Behavioural and psychological symptoms in neurocognitive disorders: Specific patterns in dementia subtypes

- MRI and bone scintigraphy for breast cancer bone metastase: a meta-analysis

- Comparative study of back propagation artificial neural networks and logistic regression model in predicting poor prognosis after acute ischemic stroke

- Analysis of the factors affecting the prognosis of glioma patients

- Compare fuhrman nuclear and chromophobe tumor grade on chromophobe RCC

- Case Report

- Signet ring B cell lymphoma: A potential diagnostic pitfall

- Research Article

- Subparaneural injection in popliteal sciatic nerve blocks evaluated by MRI

- Loneliness in the context of quality of life of nursing home residents

- Biological characteristics of cervical precancerous cell proliferation

- Effects of Rehabilitation in Bankart Lesion in Non-athletes: A report of three cases

- Management of complications of first instance of hepatic trauma in a liver surgery unit: Portal vein ligation as a conservative therapeutic strategy

- Matrix metalloproteinase 2 knockdown suppresses the proliferation of HepG2 and Huh7 cells and enhances the cisplatin effect

- Comparison of laparoscopy and open radical nephrectomy of renal cell cancer

- Case Report

- A severe complication of myocardial dysfunction post radiofrequency ablation treatment of huge hepatic hemangioma: a case report and literature review

- Solar urticaria, a disease with many dark sides: is omalizumab the right therapeutic response? Reflections from a clinical case report

- Research Article

- Binge eating disorder and related features in bariatric surgery candidates

- Propofol versus 4-hydroxybutyric acid in pediatric cardiac catheterizations

- Nasointestinal tube in mechanical ventilation patients is more advantageous

- The change of endotracheal tube cuff pressure during laparoscopic surgery

- Correlation between iPTH levels on the first postoperative day after total thyroidectomy and permanent hypoparathyroidism: our experience

- Case Report

- Primary angiosarcoma of the kidney: case report and comprehensive literature review

- Research Article

- miR-107 enhances the sensitivity of breast cancer cells to paclitaxel

- Incidental findings in dental radiology are concerning for family doctors

- Suffering from cerebral small vessel disease with and without metabolic syndrome

- A meta-analysis of robot assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy versus laparoscopic radical prostatectomy

- Indications and outcomes of splenectomy for hematological disorders

- Expression of CENPE and its prognostic role in non-small cell lung cancer

- Barbed suture and gastrointestinal surgery. A retrospective analysis

- Using post transplant 1 week Tc-99m DTPA renal scan as another method for predicting renal graft failure

- The pseudogene PTTG3P promotes cell migration and invasion in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- Lymph node ratio versus TNM system as prognostic factor in colorectal cancer staging. A single Center experience

- Review Article

- Minimally invasive pilonidal sinus treatment: A narrative review

- Research Article

- Anatomical workspace study of Endonasal Endoscopic Transsphenoidal Approach

- Hounsfield Units on Lumbar Computed Tomography for Predicting Regional Bone Mineral Density

- Communication

- Aspirin, a potential GLUT1 inhibitor in a vascular endothelial cell line

- Research Article

- Osteopontin and fatty acid binding protein in ifosfamide-treated rats

- Familial polyposis coli: the management of desmoid tumor bleeding

- microRNA-27a-3p down-regulation inhibits malignant biological behaviors of ovarian cancer by targeting BTG1

- PYCR1 is associated with papillary renal cell carcinoma progression

- Prediction of recurrence-associated death from localized prostate cancer with a charlson comorbidity index–reinforced machine learning model

- Colorectal cancer in the elderly patient: the role of neo-adjuvant therapy

- Association between MTHFR genetic polymorphism and Parkinson’s disease susceptibility: a meta-analysis

- Metformin can alleviate the symptom of patient with diabetic nephropathy through reducing the serum level of Hcy and IL-33

- Case Report

- Severe craniofacial trauma after multiple pistol shots

- Research Article

- Echocardiography evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function in elderly women with metabolic syndrome

- Tailored surgery in inguinal hernia repair. The role of subarachnoid anesthesia: a retrospective study

- The factors affecting early death in newly diagnosed APL patients

- Review Article

- Oncological outcomes and quality of life after rectal cancer surgery

- Research Article

- MiR-638 repressed vascular smooth muscle cell glycolysis by targeting LDHA

- microRNA-16 via Twist1 inhibits EMT induced by PM2.5 exposure in human hepatocellular carcinoma

- Analyzing the semantic space of the Hippocratic Oath

- Fournier’s gangrene and intravenous drug abuse: an unusual case report and review of the literature

- Evaluation of surgical site infection in mini-invasive urological surgery

- Dihydromyricetin attenuates inflammation through TLR4/NF-kappaB pathway

- Clinico-pathological features of colon cancer patients undergoing emergency surgery: a comparison between elderly and non-elderly patients

- Case Report

- Appendix bleeding with painless bloody diarrhea: A case report and literature review

- Research Article

- Protective effects of specneuzhenide on renal injury in rats with diabetic nephropathy

- PBF, a proto-oncogene in esophageal carcinoma

- Use of rituximab in NHL malt type pregnant in I° trimester for two times

- Cancer- and non-cancer related chronic pain: from the physiopathological basics to management

- Case report

- Non-surgical removal of dens invaginatus in maxillary lateral incisor using CBCT: Two-year follow-up case report

- Research Article

- Risk factors and drug resistance of the MDR Acinetobacter baumannii in pneumonia patients in ICU

- Accuracy of tumor perfusion assessment in Rat C6 gliomas model with USPIO

- Lemann Index for Assessment of Crohn’s Disease: Correlation with the Quality of Life, Endoscopic Disease activity, Magnetic Resonance Index of Activity and C- Reactive Protein

- Case report

- Münchausen syndrome as an unusual cause of pseudo-resistant hypertension: a case report

- Research Article

- Renal artery embolization before radical nephrectomy for complex renal tumour: which are the true advantages?

- Prognostic significance of CD276 in non-small cell lung cancer

- Potential drug-drug interactions in acute ischemic stroke patients at the Neurological Intensive Care Unit

- Effect of vitamin D3 on lung damage induced by cigarette smoke in mice

- CircRNA-UCK2 increased TET1 inhibits proliferation and invasion of prostate cancer cells via sponge miRNA-767-5p

- Case report

- Partial hydatidiform mole and coexistent live fetus: a case report and review of the literature

- Research Article

- Effect of NGR1 on the atopic dermatitis model and its mechanisms

- Clinical features of infertile men carrying a chromosome 9 translocation

- Review Article

- Expression and role of microRNA-663b in childhood acute lymphocytic leukemia and its mechanism

- Case Report

- Mature cystic teratoma of the pancreas: A rare cystic neoplasm

- Research Article

- Application of exercised-based pre-rehabilitation in perioperative period of patients with gastric cancer

- Case Report

- Predictive factors of intestinal necrosis in acute mesenteric ischemia

- Research Article

- Application of exercised-based pre-rehabilitation in perioperative period of patients with gastric cancer

- Effects of dexmedetomidine on the RhoA /ROCK/ Nox4 signaling pathway in renal fibrosis of diabetic rats

- MicroRNA-181a-5p regulates inflammatory response of macrophages in sepsis

- Intraventricular pressure in non-communicating hydrocephalus patients before endoscopic third ventriculostomy

- CyclinD1 is a new target gene of tumor suppressor miR-520e in breast cancer

- CHL1 and NrCAM are primarily expressed in low grade pediatric neuroblastoma

- Epidemiological characteristics of postoperative sepsis

- Association between unstable angina and CXCL17: a new potential biomarker

- Cardiac strains as a tool for optimization of cardiac resynchronization therapy in non-responders: a pilot study

- Case Report

- Resuscitation following a bupivacaine injection for a cervical paravertebral block

- Research Article

- CGF treatment of leg ulcers: A randomized controlled trial

- Surgical versus sequential hybrid treatment of carotid body tumors