The impact of maternal cardiovascular status prior to labor on birth outcomes: an observational study

-

Daniele Farsetti

, Francesca Pometti

Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of maternal characteristics, computerized cardiotocography (cCTG), maternal hemodynamics, and fetal Doppler in predicting adverse perinatal outcomes (APO) in healthy term pregnancies before labor onset.

Methods

In this prospective observational study, 395 term pregnant women were enrolled. Data on obstetric history, cCTG, maternal hemodynamics, and fetal ultrasound were collected. Women undergoing labor induction were excluded. The primary endpoint was a composite APO, defined as cesarean or operative vaginal delivery due to pathological CTG, 5-min Apgar <7, umbilical artery pH <7.1 and/or base excess >12 mmol/L, or NICU admission. A secondary outcome, “objective APO”, excluded operative delivery for pathological CTG. Logistic regression analyses were performed to assess predictors of APO.

Results

Among 307 women with spontaneous labor, 41 (13.36 %) experienced a composite APO. These women were less often multiparous (7.32 vs. 27.07 %, p=0.01), had higher systemic vascular resistance [SVR: 1,353 (1,209–1,498) vs. 1,249 (1,071–1,438) dyn s cm−5, p=0.01], and lower short-term variability [STV: 7.5 (6.2–10.0) vs. 9.1 (7.6–11.0) ms, p<0.01]. Fetal Doppler indices, including cerebro-placental ratio, showed no significant differences. ROC analysis identified SVR >1,135 dyn s cm−5 (OR 6.92, 95 % CI 2.08–23.03) and STV ≤7 ms (OR 3.95, 95 % CI 1.97–7.92), as optimal predictors. Multivariate analysis confirmed STV, SVR, and parity as independent predictors. In the secondary analysis of “objective APO”, both SVR and STV remained significant predictors, and the multivariable model demonstrated excellent discrimination [AUC 0.931 (95 % CI 0.896–0.957)].

Conclusions

In term pregnancies, maternal hemodynamic assessment and cCTG performed before labor may improve the identification of women at increased risk of APO.

Introduction

The development of an accurate diagnostic test to identify the risk of adverse outcomes during labor remains one of the greatest challenges in obstetrics. Current risk assessment strategies rely primarily on maternal demographic and clinical factors, including maternal age, socio-economic conditions, ethnicity, educational level, and obstetric history [1], [2], [3]. However, these parameters alone often fail to provide a comprehensive assessment of perinatal risk, as they do not account for the dynamic physiological changes that occur during pregnancy and labor. This limitation underscores the urgent need for more objective, quantifiable, and reliable predictive tools capable of identifying pregnancies at increased risk of adverse perinatal outcomes.

Recent studies have shown that placental dysfunction may also affect term fetuses with appropriate-for-gestational-age (AGA) weight, leading to increased interest in the cerebroplacental ratio (CPR) as a potential marker for identifying pregnancies at higher risk of perinatal complications [4], 5]. A lower CPR has been associated with an increased risk of operative delivery, fetal distress, and neonatal acidosis, suggesting a potential role in fetal surveillance. Despite its increasing use in clinical practice, systematic reviews have not yet confirmed its predictive accuracy, and its role in perinatal risk stratification remains controversial and inconclusive [6].

Similarly, computerized cardiotocography (cCTG) has been extensively studied for its potential to improve the detection of fetal distress and adverse perinatal outcomes. Unlike conventional CTG, cCTG eliminates inter- and intra-observer variability, allowing for a more standardized and objective evaluation of fetal well-being. Several studies have suggested that cCTG-derived short-term variability (STV) may be a valuable predictor of fetal acidosis and neonatal compromise. However, even the most recent systematic reviews lack conclusive evidence regarding its effectiveness in reducing perinatal morbidity and mortality [7]. The limited predictive capacity of cCTG highlights the necessity of integrating additional maternal and fetal parameters to improve risk assessment.

Beyond fetal monitoring, maternal cardiovascular adaptation throughout pregnancy plays a fundamental role in maintaining uteroplacental perfusion and ensuring fetal well-being [8]. Impaired maternal hemodynamics have been associated with several pregnancy complications, including hypertensive disorders [9], [10], [11], [12], fetal growth restriction (FGR) [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], and preterm birth [19], 20]. During pregnancy, the maternal cardiovascular system undergoes profound hemodynamic changes, including a decrease in systemic vascular resistance (SVR) and an increase in cardiac output (CO), which facilitate adequate placental perfusion. Failure to achieve these physiological adaptations may predispose to labor complications, including intrapartum fetal distress and operative delivery.

In a previous study conducted by our group, we demonstrated that assessing maternal cardiovascular adaptation during labor could help identify women at increased risk of intrapartum complications [21]. Specifically, we found that women with lower CO and increased SVR in the early stages of labor had an 8- to 10-fold higher risk of developing labor-related complications, such as operative delivery for fetal distress or emergency cesarean section. These findings support the hypothesis that impaired uterine perfusion may compromise fetal oxygenation, ultimately leading to adverse perinatal outcomes (APO). However, whether these hemodynamic alterations are already detectable before labor onset and how they interact with fetal monitoring parameters remain largely unexplored.

The aim of this study is to evaluate maternal characteristics, fetal cardiotocography, fetal Doppler ultrasound, and maternal hemodynamics in healthy term pregnancies before the onset of labor to identify reliable predictors of APO. Additionally, we seek to determine the most robust independent predictors of APO, which could enhance risk stratification, improve antenatal surveillance protocols, and inform clinical decision-making to optimize maternal and perinatal outcomes.

Materials and methods

This was an observational prospective study performed at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Policlinico Casilino Hospital, Rome. We enrolled 395 patients at term of pregnancy, before the onset of labor between September 2016 and December 2017.

The inclusion criteria were:

singleton pregnancy,

pregnancy dating by first trimester ultrasound using crown-rump length (CRL),

gestational age >37 + 0,

estimated fetal birth weight >10th percentile,

absence of fetal and maternal disease at enrollment.

The exclusion criteria were multiple pregnancies, chromosomal abnormalities, genetic syndrome or major structural fetal abnormalities, preterm rupture of membranes, intrauterine infection, undetermined gestational age, history of maternal heart disease, tobacco use, preexisting chronic medical problems, hypertensive disorders, FGR, assisted reproductive technology (ART) or if an elective C-section due to maternal request or breech presentation was scheduled.

For each patient, the following anamnestic, anthropometric and demographic parameters were collected: age, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), last menstrual period, gestational age corrected by first trimester ultrasound and obstetrical history.

Ultrasound examinations were performed using a 2–8 MHz volumetric probe (GE Healthcare, Milan, Italy). Doppler measurements were obtained from the umbilical artery (UA) and middle cerebral artery (MCA), according to the most modern standard protocol in absence of fetal breathing or body movements [22]. The CPR was calculated by dividing the pulsatility indices of the MCA by the UA. We also collected the Amniotic Fluid Index calculated as the sum of the deepest vertical pockets of amniotic fluid measured in each of the four uterine quadrants [23].

All patients underwent a hemodynamic evaluation using Ultrasound Cardiac Output Monitor (USCOM Ltd, Coffs Harbor, Australia). USCOM is a non-invasive Doppler ultrasonic technology for determining hemodynamic variables. A non-imaging continuous-wave Doppler transducer is placed at the suprasternal notch to measure transaortic blood flow [24], [25], [26]. It has demonstrated comparable accuracy to invasive methods (Swan-Ganz catheter) and the USCOM measurements are well correlated with echocardiographic assessment [27]. The measurements were performed by one trained operator under standardized conditions as described in previous studies [24], [25], [26]. The patients were in the left recumbent position to avoid the aortocaval compression in supine position and rested for at least 10 min before assessment. Blood pressure was measured using an automated brachial sphygmomanometer. Room temperature was controlled, and participants refrained from caffeine prior to the measurements.

We collected the following parameters: mean arterial pressure (MAP), SVR, CO, Smith-Madigan inotropy index (INO), potential to kinetic energy ratio (PKR).

The last two parameters are calculated from the assessment of maternal cardiovascular potential energy (PE) and kinetic energy (KE). The first one is the portion of output energy that produces arterial pressure, and the second one is the energy of blood flow. INO is calculated by the sum of these 2 types of energy adjusted for body surface area and it is a new approach to assess the inotropy status. PKR represents the ratio between PE and KE and it is a measure of the balance between blood pressure and blood flow [13].

The cCTG was performed by Sonicaid Oxford 8002 System (Manor Way, Old Woking, Surrey, England). Short-term variability (STV) was calculated as the average of sequential minute pulse interval differences by Dawes-Redman software-based algorithm.

A total of 88 (22.28 %) patients had an induction of labor and were excluded. Our sample included 307 patients (77.72 %) in spontaneous labor with a hemodynamic evaluation performed within 8 days prior to delivery. Subsequently we collected information about delivery to identify any maternal or neonatal adverse outcome: gestational age at delivery, epidural analgesia, delivery type (spontaneous, operative vaginal delivery, c-section) and any obstetrical indications, placental delivery, blood loss, neonatal sex, neonatal weight, APGAR score at 1 and 5 min.

The primary outcome of this study was a composite adverse perinatal outcome (APO), defined as the occurrence of at least one of the following:

caesarean section or vaginal operative delivery for pathological cardiotocography, defined according to the national SIGO guideline and applied in clinical decision-making at our hospital [28],

5-min Apgar score <7,

neonatal umbilical artery pH <7.1 and/or base excess >12 mmol/L at birth,

neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission.

A secondary outcome, excluding operative delivery for pathological cardiotocography, was also considered to assess the robustness of the findings for a more objective outcome, reducing subjectivity (subjective APO).

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysis

We divided our sample in two groups: patients with an APO and patients with uncomplicated ones.

Continuous variables were expressed as median with interquartile range, categorical variables were expressed as number and percentage. Group comparisons were performed using Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate based on data distribution. We performed a Chi-Squared test for the comparison of two proportions (from independent samples). To account for multiple comparisons, p-values were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) procedure applied only to independent variables, with significance set at FDR <0.05.

A receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve was constructed for each hemodynamic, cardiotocography and demographic parameter, to identify the best cut-off and convert the continuous variables into categorical ones. For each individual predictive variable, diagnostic performance metrics – including sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) – were calculated.

We performed a univariate binary logistic regression analysis and odds ratios (ORs) were calculated. In conclusion, a multivariate binary logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent predictors. To internally validate the predictive performance of the model, the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) was calculated with 95 % confidence intervals estimated using bootstrap resampling (1,000 iterations). The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was also applied to assess model calibration.

To assess the clinical usefulness of the diagnostic tests and prediction models, the number needed to predict (NNP) was calculated. The NNP represents the average the number of patients who need to be examined in the patient population to correctly predict the diagnosis of one person [29].

Unlike the simple inverse of the Youden index, which does not consider disease prevalence, we calculated the NNP by incorporating the prevalence of the event in our study population to better reflect the real-world clinical context. The NNP was computed using the following formula [29]:

A post-hoc sample size assessment was performed using the formula proposed by Riley et al. [30] to verify whether the available sample size was sufficient to meet the criteria for model stability and minimal overfitting.

A secondary analysis was performed to evaluate the predictive performance of variables for “objective APO”, defined as the presence of at least one of the following: 5-min Apgar score <7, umbilical artery pH <7.1 and/or base excess >12 mmol/L at birth, or NICU admission. Operative delivery (caesarean section or instrumental vaginal delivery) for suspected fetal distress, included in the primary composite APO definition, was excluded from this endpoint.

The statistical analysis was performed using MedCalc Statistical Software (MedCalc Software bvba, Ostend, Belgium; https://www.medcalc.org; 2016). Statistical significance was set to p<0.05.

Results

Primary analysis

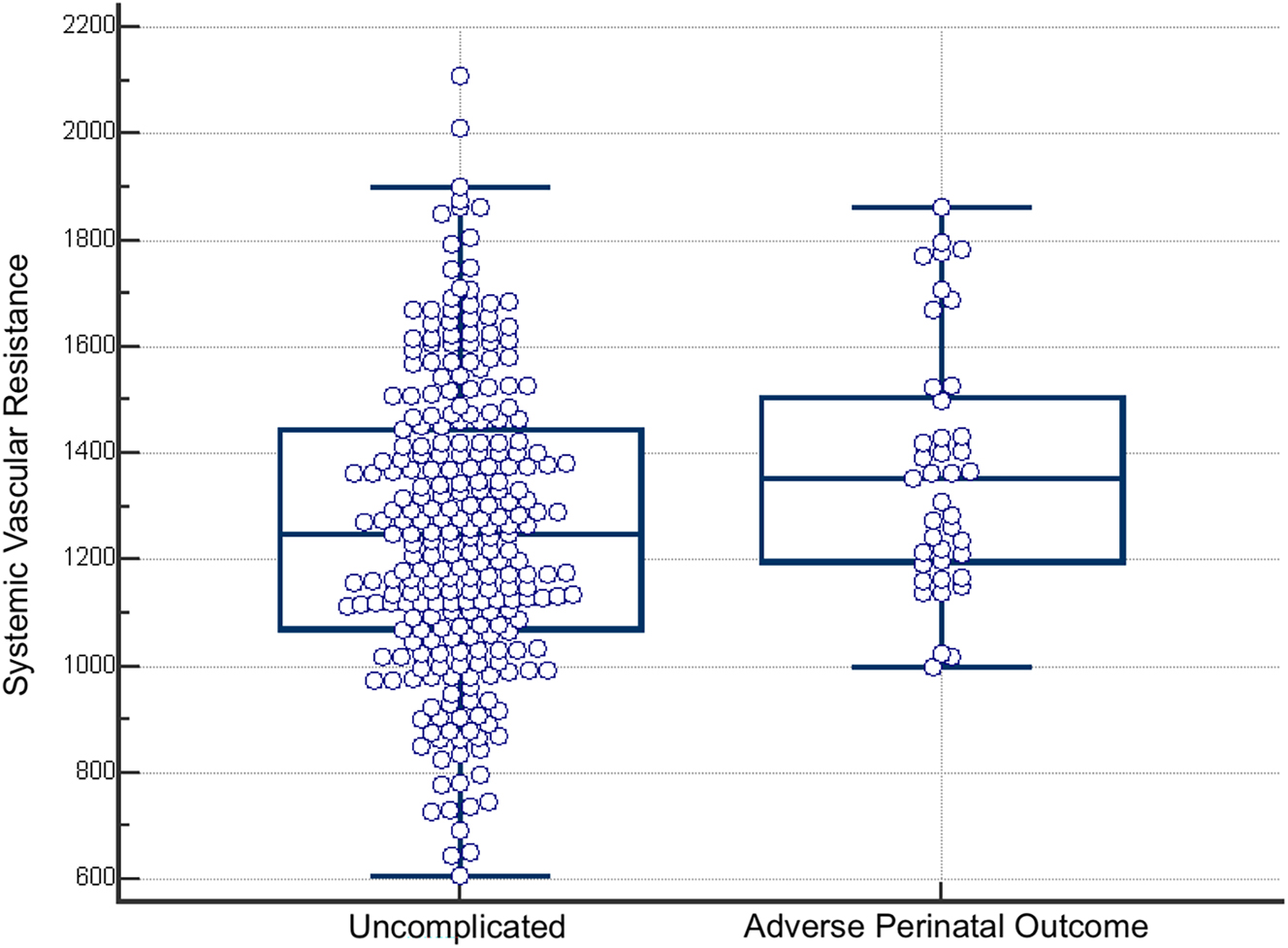

Among the 307 patients with spontaneous onset of labor, APO were observed in 41 cases (13.36 %) (Table S1). Table 1 summarizes the maternal and fetal characteristics at the time of enrollment. There were no significant differences between patients with and without APO in terms of gestational age, maternal age, BMI, weight, height, smoking status, fetal Doppler parameters, or amniotic fluid index. However, the rate of multiparity was significantly higher in patients with uncomplicated outcomes (27.07 vs. 7.32 %, p=0.01) and remained significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction. Among hemodynamic parameters, SVR was significantly higher in patients with APO [1,353 (1,209–1,498) dyn s cm−5 vs. 1,249 (1,071–1,438) dyn s cm−5, p=0.01] (Figure 1), and this difference also remained significant after Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment, while other maternal hemodynamic measures (CO, MAP, INO, PKR) did not differ significantly.

Demographic, hemodynamic, fetal ultrasound, cardiotocography and perinatal characteristics of the included patients, divided according to the presence of adverse perinatal outcomes.

| Parameters | Uncomplicated outcomes, n=266 | APO, n=41 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Height, m | 1.65 (1.60–1.70) | 1.62 (1.60–1.68) | 0.06 |

| Weight, kg | 72.00 (67.00–81.75) | 72.00 (63.00–78.00) | 0.33 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.62 (24.61–29.40) | 27.25 (24.05–28.72) | 1.00 |

| Age, years | 32.00 (28.00–36.00) | 31.50 (27.75–36.00) | 0.61 |

| Gestational age, days | 277.00 (272.25–281.00) | 280.00 (271.00–282.00) | 0.85 |

| Multiparous | 72 (27.07 %) | 3 (7.32 %) | 0.01 |

| Smoker | 8 (11.59 %) | 1 (14.29 %) | 0.81 |

|

|

|||

| Maternal hemodynamics | |||

|

|

|||

| MAP, mmHg | 88.33 (83.33–93.67) | 93.33 (83.33–96.67) | 0.11 |

| SVR, dyn s cm−5 | 1,249.00 (1,071.15–1,438.14) | 1,353.00 (1,209.00–1,498.63) | 0.01 |

| CO, L/min | 5.54 (4.98–6.50) | 5.20 (4.72–6.00) | 0.05 |

| INO, W/m2 | 1.40 (1.20–1.60) | 1.40 (1.10–1.60) | 0.42 |

| PKR | 29.00 (22.00–40.00) | 31.87 (25.00–41.00) | 0.13 |

| cCTG | |||

| STV, ms | 9.05 (7.60–11.00) | 7.50 (6.20–10.00) | <0.01 |

|

|

|||

| Fetal ultrasound | |||

|

|

|||

| UA-PI | 0.81 (0.70–0.93) | 0.78 (0.70–0.90) | 0.85 |

| MCA-PI | 1.34 (1.14–1.68) | 1.30 (1.07–1.59) | 0.37 |

| CPR | 1.77 (1.44–2.17) | 1.65 (1.35–2.02) | 0.53 |

| AFI, mm | 108.00 (86.00–135.00) | 102.00 (80.00–122.00) | 0.36 |

|

|

|||

| Outcome delivery | |||

|

|

|||

| Gestational age delivery, days | 282.00 (278.00–286.00) | 283.00 (277.00–287.00) | 0.79 |

| Interval evaluation-delivery | 5.00 (2.00–7.00) | 4.00 (3.00–7.00) | 0.78 |

| Neonatal weight, g | 3,400.00 (3,100.00–3,650.00) | 3,275.00 (3,017.50–3,547.50) | 0.11 |

| Analgesia | 215 (80.83 %) | 32 (78.05 %) | 0.84 |

-

APO, adverse perinatal outcomes; BMI, body mass index; MAP, mean arterial pressure; HR, heart rate; SVR, systemic vascular resistance; CO, cardiac output; INO, Smith-Madigan inotropy index; PKR, potential to kinetic energy ratio; STV, short-term variability; cCTG, computerized cardiotocography; UA-PI, umbilical artery-pulsatility index; MCA-PI, middle cerebral artery-pulsatility index; CPR, cerebroplacental ratio; AFI, amniotic fluid index. Data are shown as median (interquartile range) or n (%).

Box-and-whisker plot of systemic vascular resistance in patients with uncomplicated delivery and with adverse perinatal outcome (APO).

Patients with APO also exhibited significantly lower STV [7.5 (6.2–10) ms vs. 9.05 (7.6–11) ms, p<0.01] compared to those with uncomplicated outcomes (Figure 2), and this difference also remained significant after Benjamini-Hochberg correction.

Box-and-whisker plot of short term variability in patients with uncomplicated delivery and with adverse perinatal outcome (APO).

There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of gestational age at birth, neonatal weight, or the use of epidural analgesia (78.05 vs. 80.83 %) (Table 1).

A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to determine the optimal cut-off values for variables showing significant differences between the two groups (Figure 3). The best thresholds identified were SVR >1,135 dyn s cm−5 [AUC 0.62 (95 % CI, 0.56–0.67), sensitivity 92.68 % (95 % CI, 80.08–98.46 %), specificity 35.34 % (95 % CI, 29.60–41.41 %), PPV 18.10 % (95 % CI, 13.13–23.98 %), NPV 96.91 % (95 % CI, 91.23–99.36 %), p<0.01] and STV ≤7 ms [AUC 0.644 (95 % CI, 0.588–0.698), sensitivity 43.90 % (95 % CI, 28.47–60.25 %), specificity 83.46 % (95 % CI, 78.44–87.72 %), PPV 29.03 % (95 % CI, 18.20–41.95 %), NPV 90.61 % (95 % CI, 86.25–93.96 %), p<0.01]. Parity showed a sensitivity of 92.68 % (95 % CI, 80.08–98.46 %), a specificity of 27.07 % (95 % CI, 21.82–32.83 %), a PPV of 16.38 % (95 % CI, 11.86–21.78 %), and a NPV of 96.00 % (95 % CI, 88.75–99.17 %) in identifying adverse outcome.

ROC curve illustrating the predictive performance of systemic vascular resistance (A) and short-term variability (B) for adverse perinatal outcomes (APO).

Univariate binary logistic regression analysis was conducted, and ORs were calculated (Table 2). A multivariate logistic regression analysis was then performed, incorporating multiparity, STV ≤7 ms, and SVR ≥1,135 dyn s cm−5. The final multivariate model demonstrated a moderate diagnostic performance [AUC 0.761 (95 % CI, 0.709–0.807)] (Table 2). Internal validation using bootstrap resampling (1,000 iterations) yielded a 95 % confidence interval for the AUC of 0.682–0.818, confirming the model’s stability. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test indicated excellent calibration of the model (χ2=0.29, p=0.990), suggesting an adequate fit between observed and predicted outcomes (Supplementary Figure 1).

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis of the association between antenatal parameters and adverse perinatal outcomes (APO).

| Univariate logistic regression analysis | Mulivariate logistic regression analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95 % CI) | p-Value | aOR (95 % CI) | p-Value | |

| Multiparity | 0.21 (95 % CI, 0.06–0.71) | <0.01 | 0.18 (0.05–0.62) | <0.01 |

| SVR >1,135 dyn s cm−5 | 6.92 (95 % CI, 2.08–23.03) | <0.01 | 6.34 (1.86–21.56) | <0.01 |

| STV ≤7 ms | 3.95 (95 % CI, 1.97–7.92) | <0.01 | 4.30 (2.04–9.06) | <0.01 |

-

SVR, systemic vascular resistance; CO, cardiac output; STV, short-term variability.

To test the robustness of our multivariate model, we performed an additional sensitivity analysis excluding borderline cases, defined as values within ±5 % of the cut-off thresholds for SVR and STV. This analysis confirmed the stability of the model, with an AUC of 0.738 (95 % CI 0.676–0.795). The odds ratios for the three variables included in the model are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Based on a Cox & Snell R2 of 0.1177 estimated from our data, an outcome prevalence of 13.36 %, and a model including three predictor parameters, the minimum required sample size according to the Riley et al. formula was 215 patients [30]. Our study population included 307 patients, confirming that the sample was adequate for reliable multivariable model development.

The NNP was calculated for individual and combined predictors. For SVR >1,135 dyn s cm−5, the NNP was 6.66; for STV ≤7 ms, 5.09; and for parity alone, 8.08. In multivariable models, the NNP was 6.90 when at least one of the three parameters (SVR, STV, or parity) was present, 5.61 when at least two were present, and 2.89 when all three predictors were simultaneously present.

Secondary analysis

A secondary analysis was also performed focusing exclusively on “objective” APO, the results of which are provided in Table 3. In this analysis, both SVR and STV proved to be strong predictors of objective APO, whereas parity did not emerge as a significant predictor of objective endpoints. The multivariable model including parity, SVR, and STV demonstrated excellent predictive performance [AUC 0.941 (95 % CI, 0.908–0.964), sensitivity 100 % (95 % CI, 47.80–100 %), specificity 72.85 % (95 % CI, 67.5–77.8 %)], comparable to the model including only SVR and STV [AUC 0.931 (95 % CI, 0.896–0.957), sensitivity 100 % (95 % CI, 47.80–100 %), specificity 72.85 % (95 % CI, 67.5–77.8 %)].

Diagnostic performance for predicting objective adverse perinatal outcomes (5-min Apgar score <7, neonatal umbilical artery pH <7.1 and/or base excess > 2 mmol/L at birth, neonatal intensive care unit admission).

| Variable | AUC | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVR >1,684 dyn s cm5 | 0.773 (0.722–0.819) | 60.00 % (14.7–94.73 %) | 94.04 % (90.7–96.4) | 15.00 % (3.21–37.89 %) | 99.30 % (97.51–99.92 %) |

| STV ≤7.5 ms | 0.819 (0.772–0.861) | 100.00 % (47.80–100.00 %) | 72.85 % (67.5–77.8 %) | 5.75 % (1.89–12.90 %) | 100.00 % (98.34–100.00 %) |

-

AUC, area under the curve; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; SVR, systemic vascular resistance; STV, short-term variability.

Discussion

Main findings

This study highlights the importance of antepartum computerized cardiotocography and maternal hemodynamic assessment in identifying patients at risk of adverse perinatal outcomes (APO) within a low-risk population for intrapartum hypoxia. Specifically, our findings indicate that SVR >1,135 dyn s cm−5, STV ≤7 ms, and multiparity are independent predictors of adverse outcomes.

Interpretation and comparison with existing literature

Our results are consistent with existing scientific literature on this topic. Multiparity has been consistently identified as a protective factor against adverse maternal and fetal outcomes, with our findings yielding an OR comparable to that reported by Kalafat et al. (OR 0.20, 95 % CI 0.06–0.56, p=0.003) [31].

Previously, our group reported a higher incidence of complications in women with SVR >1,069 dyn s cm−5 during early labor [21]. Notably, this threshold is close to the value identified in this study (1,135 dyn s cm−5), where SVR emerged as the strongest independent predictor of APO. The slightly higher cut-off observed here is likely attributable to methodological differences: in this study, measurements were obtained at term in a resting, pre-labor condition, whereas the previous study assessed women at the onset of active labor, when CO is physiologically increased, resulting in lower SVR values. Importantly, these differences are minimal and do not alter the clinical interpretation, as both studies consistently demonstrate that elevated SVR is strongly associated with adverse perinatal outcomes.

Moreover, Kalafat et al. demonstrated that elevated SVR, assessed using USCOM, correlates with an increased risk of operative delivery due to presumed fetal compromise in women undergoing labor induction [31].

Women who developed complications during labor exhibited a distinct hemodynamic profile characterized by high vascular resistance and low CO, indicative of cardiovascular maladaptation. This hypodynamic circulation was significantly associated with the development of fetal distress during labor. Cardiovascular adaptation is essential for maintaining adequate uteroplacental perfusion and ensuring sufficient fetal oxygen supply during pregnancy and labor [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32].

Labor represents a major physiological challenge for the feto-placental unit, as uterine contractions transiently reduce blood flow to the fetus [33]. Consequently, the onset of labor may further compromise placental function, increasing the risk of hypoxic perinatal events. Our previous studies demonstrated a relationship between hypodynamic circulation and subclinical placental dysfunction, suggesting that maternal hemodynamic abnormalities may be clinically silent until labor begins.

In uncomplicated pregnancies, vascular remodeling results in SVR reduction and CO augmentation, which are critical for maintaining adequate uterine perfusion and preventing fetal hypoxia. During labor, CO increases by 30 % in the first stage and by over 50 % in the second stage. Women with elevated SVR and poor cardiac performance at term face an increased risk of developing intrapartum complications. Subclinical alterations in cardiac function may underlie reduced uteroplacental perfusion, leading to fetal distress.

These findings suggest that maternal hemodynamic alterations, characterized by elevated SVR and decreased CO, reduce uteroplacental perfusion and compromise fetal oxygenation, particularly during labor when metabolic demands increase and placental circulation is further stressed.

In our study, fetal Doppler assessment before delivery was not significantly associated with subsequent adverse outcomes. Previous studies have reported that antenatal and early labor Doppler evaluation of cerebral redistribution is linked to an increased likelihood of vacuum extraction or cesarean section due to suspected fetal distress, though with poor predictive performance [34], [35], [36].

No significant differences have been reported between the use of antenatal CTG vs. no CTG in terms of perinatal mortality, cesarean section rate, Apgar scores <7 at 5 min, NICU admission, or gestational age at birth. However, computerized CTG, as opposed to traditional CTG, has been associated with a significant reduction in perinatal mortality (RR 0.20, 95 % CI 0.04–0.88), while no significant differences were found for cesarean section rate, Apgar scores <7 at 5 min, NICU stay, or gestational age at birth [37]. Notably, most studies evaluating CTG involve high-risk pregnancies [37], whereas few observational studies have focused on antenatal CTG in low-risk pregnancies, often with limited sample sizes. To date, the use of traditional CTG in low-risk pregnancies has demonstrated poor predictive capability for APO [38].

A prior study indicated that computerized CTG during labor in low-risk pregnancies effectively identifies fetal distress, with STV emerging as a strong independent predictor of fetal acidemia (OR 20.96, p<0.001) [39].

In our study, antenatal computerized CTG was predictive of perinatal complications, including cesarean section or operative vaginal delivery for pathological CTG, Apgar scores <7 at 5 min, neonatal metabolic acidosis, and NICU admission. Our findings suggest that computerized CTG may serve as a valuable tool for identifying pregnancies with subclinical maternal hemodynamic compromise, which are at higher risk of intrapartum hypoxic events.

Clinical implications

Intrapartum fetal distress in apparently low-risk pregnancies is a critical issue, as many vulnerable fetuses remain undetected until labor, when reduced placental reserve can lead to hypoxia, urgent delivery, and serious neonatal complications. In most cases, fetal distress during labor is the result of preexisting placental dysfunction, which limits the fetus’s ability to tolerate the stress of uterine contractions [40]. Identifying these pregnancies before the onset of labor could allow targeted surveillance and even the consideration of preventive interventions aimed at improving placental perfusion. However, current clinical trials exploring potential cardiovascular therapies, such as phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, do not incorporate maternal hemodynamic assessment into their inclusion criteria – potentially overlooking a subgroup of patients who might derive the greatest benefit.

To evaluate the clinical applicability of our findings, we calculated the NNP, a metric that quantifies the efficiency of a diagnostic tool in identifying true positive cases. The relatively low NNP values observed for both individual parameters and combined models suggest that these tests may hold practical relevance even in a low-risk population. In particular, the progressive reduction of NNP when multiple predictors are simultaneously present underscores the additive value of combining maternal hemodynamic profiling with computerized CTG. Beyond statistical significance, the effect sizes observed showed clear clinical relevance: multiparity reduced the risk of APO by ∼80 %, elevated SVR conferred a two- to three-fold increase, and reduced STV tripled to quadrupled the likelihood of APO. Consistently, SVR >1,135 dyn s cm−5 demonstrated >90 % sensitivity, while STV ≤7 ms showed >80 % specificity, further reinforcing the potential utility of these markers for clinical risk stratification. This finding supports the potential implementation of a multimodal approach in routine antenatal assessment to better stratify the risk of intrapartum complications.

An important consideration when evaluating the clinical implications of this study relates to the potential costs associated with implementing routine screening based on maternal hemodynamics and computerized cardiotocography in all low-risk pregnancies. Although the acquisition and maintenance of non-invasive hemodynamic devices such as USCOM may initially appear costly, their integration into routine antenatal care at term could prove cost-effective when balanced against the potential reduction in emergency obstetric interventions, neonatal morbidity, and NICU admissions. Early identification of at-risk pregnancies through maternal cardiovascular assessment may improve perinatal outcomes and optimize the use of healthcare resources. Future prospective studies are warranted to formally assess the cost-effectiveness of such an approach in low-risk populations.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is that one of the primary outcomes – obstetric intervention due to intrapartum fetal distress – was subjectively defined based on cardiotocography (CTG) interpretation, which has a well-documented high interobserver and intraobserver variability [41]. According to Rhöse et al., interobserver agreement for CTG classification and clinical management decisions is poor (κw range 0.31–0.50 and 0.20–0.45, respectively) [41]. However, the highest agreement was found for abnormal CTG patterns (Pa range 0.28–0.36), which are the primary indications for cesarean section or operative delivery [41]. In our study, no formal inter-observer agreement analysis was performed, and this may represent a potential source of bias. However, to reduce misclassification, only cases with clearly documented indications for operative delivery due to pathological CTG were included as adverse perinatal outcomes. Cases with multifactorial or unclear indications were excluded. While this approach reflects real-world clinical decision-making, it underlines the need for further prospective studies with centralized CTG review or predefined adjudication protocols to improve reproducibility.

As with all non-invasive hemodynamic methods, USCOM measurements may be subject to operator dependency. However, in this study, all assessments were performed by a single, trained operator under standardized conditions, minimizing variability and ensuring measurement consistency. Furthermore, USCOM has been validated against both echocardiography – the current gold standard for maternal cardiovascular assessment – and invasive techniques, and several studies have demonstrated its good reproducibility even in obstetric populations [8].

Additionally, this was a single-center study conducted in a tertiary care setting, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other clinical contexts or patient populations. Although the exclusion of induced labors may reduce external applicability, this was a deliberate methodological choice to eliminate a major source of confounding related to pharmacologic and clinical variability.

Taken together, these limitations underline the need for a prospective, multicenter validation study to assess the reproducibility and predictive performance of the proposed model. This investigation should be considered a pilot study, aimed at exploring associations between maternal hemodynamic parameters, computerized CTG analysis, and adverse perinatal outcomes, providing the rationale and framework for future confirmatory research.

Strengths

A major strength of this study is that the hemodynamic assessment was conducted under standardized conditions, minimizing potential confounders such as labor pain and variations in room conditions that could affect hemodynamic parameters. Unlike our previous study, which assessed maternal hemodynamics during labor, this research examined maternal cardiovascular status before the onset of labor, allowing for a standardized evaluation in a non-stress condition. The 8-day window between assessment and delivery ensured clinical feasibility, while still capturing a physiologically stable and relevant maternal profile close to birth. This approach enabled us to determine whether the resting hemodynamic profile differs in women at risk of APO.

Additionally, we excluded patients undergoing labor induction to minimize confounding factors. Labor induction is known to significantly increase the likelihood of emergency cesarean section due to intrapartum fetal compromise [3].

Conclusions

In conclusion, low short-term variability (STV), and hypodynamic circulation (low CO and elevated SVR) before labor onset are significant risk factors for adverse perinatal outcomes. Maternal hemodynamic assessment and computerized cardiotocography at term may enhance the ability to predict adverse labor outcomes in low-risk pregnancies.

These new technologies could be utilized as a screening tool for APO in low-risk pregnancies, potentially identifying cases that would not have been detected using traditional methods, although their diagnostic performance was modest.

Pregnancies at increased risk may benefit from closer surveillance to prevent maternal and fetal complications.

-

Research ethics: IRB Rome 85.20/2020.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: DF and FP contributed to counselling, data collection, statistical analysis and to writing the article. GC, LP, DAD and BL contributed to data collection. HV contributed to the conception and design of the study. GPN, GMN and BV contributed to the statistical analysis and the interpretation of the analysis and data collection. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

1. Essex, HN, Green, J, Baston, H, Pickett, KE. Which women are at an increased risk of a caesarean section or an instrumental vaginal birth in the UK: an exploration within the Millennium Cohort Study. BJOG 2013;120:732–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12177.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Lean, SC, Derricott, H, Jones, RL, Heazell, AEP. Advanced maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2017;12:e0186287. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186287.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Mendis, R, Flatley, C, Kumar, S. Maternal demographic factors associated with emergency caesarean section for non-reassuring fetal status. J Perinat Med 2018;46:641–7. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2017-0142.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Prior, T, Mullins, E, Bennett, P, Kumar, S. Prediction of intrapartum fetal compromise using the cerebroumbilical ratio: a prospective observational study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;208:124.e1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2012.11.016.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Morales-Roselló, J, Khalil, A, Morlando, M, Bhide, A, Papageorghiou, A, Thilaganathan, B. Poor neonatal acid-base status in term fetuses with low cerebroplacental ratio. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2015;45:156–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.14647.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Conde-Agudelo, A, Villar, J, Kennedy, SH, Papageorghiou, AT. Predictive accuracy of cerebroplacental ratio for adverse perinatal and neurodevelopmental outcomes in suspected fetal growth restriction: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2018;52:430–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.19117.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Tsipoura, A, Giaxi, P, Sarantaki, A, Gourounti, K. Conventional cardiotocography versus computerized CTG analysis and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review. Maedica (Bucur) 2023;18:483–9. https://doi.org/10.26574/maedica.2023.18.3.483.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Vasapollo, B, Zullino, S, Novelli, GP, Farsetti, D, Ottanelli, S, Clemenza, S, et al.. Maternal hemodynamics from preconception to delivery: research and potential diagnostic and therapeutic implications: position statement by Italian Association of Preeclampsia and Italian Society of Perinatal Medicine. Am J Perinatol 2024;41:1999–2013. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-2267-3994. Epub 2024 Feb 13. Erratum in: Am J Perinatol. 2024 Oct;41(14):e1. doi: 10.1055/s-0044-1786746.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Vasapollo, B, Novelli, GP, Farsetti, D, Valensise, H. Maternal peripheral vascular resistance at mid gestation in chronic hypertension as a predictor of fetal growth restriction. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2022;35:9834–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2022.2056443.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Vasapollo, B, Novelli, GP, Gagliardi, G, Farsetti, D, Valensise, H. Pregnancy complications in chronic hypertensive patients are linked to pre-pregnancy maternal cardiac function and structure. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020;223:425.e1–425.e13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.02.043.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Pisani, I, Tiralongo, GM, Lo Presti, D, Gagliardi, G, Farsetti, D, Vasapollo, B, et al.. Correlation between maternal body composition and haemodynamic changes in pregnancy: different profiles for different hypertensive disorders. Pregnancy Hypertens 2017;10:131–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preghy.2017.07.149.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Gagliardi, G, Tiralongo, GM, Lo Presti, L, Pisani, I, Farsetti, D, Vasapollo, B, et al.. Screening for pre-eclampsia in the first trimester: role of maternal hemodynamics and bioimpedance in non-obese patients. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2017;50:584–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.17379.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Valensise, H, Farsetti, D, Pometti, F, Vasapollo, B, Novelli, GP, Lees, C. The cardiac-fetal-placental unit: fetal umbilical vein flow rate is linked to the maternal cardiac profile in fetal growth restriction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2023;228:222.e1–222.e12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2022.08.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Vasapollo, B, Lo Presti, D, Gagliardi, G, Farsetti, D, Tiralongo, GM, Pisani, I, et al.. Restricted physical activity in pregnancy reduces maternal vascular resistance and improves fetal growth. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2018;51:672–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.17489.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Vasapollo, B, Novelli, GP, Maellaro, F, Gagliardi, G, Pais, M, Silvestrini, M, et al.. Maternal cardiovascular profile is altered in the pre-clinical phase of normotensive early and late fetal growth restriction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2025;232:312.e1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2024.05.015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Farsetti, D, Vasapollo, B, Pometti, F, Frantellizzi, R, Novelli, GP, Valensise, H. Maternal hemodynamics for the identification of early fetal growth restriction in normotensive pregnancies. Placenta 2022;129:12–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.placenta.2022.09.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Farsetti, D, Pometti, F, Tiralongo, GM, Lo Presti, D, Pisani, I, Gagliardi, G, et al.. Distinction between SGA and FGR by means of fetal umbilical vein flow and maternal hemodynamics. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2022;35:6593–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2021.1918091.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Farsetti, D, Pometti, F, Vasapollo, B, Novelli, GP, Nardini, S, Lupoli, B, et al.. Nitric oxide donor increases umbilical vein blood flow and fetal oxygenation in fetal growth restriction. A pilot study. Placenta 2024;151:59–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.placenta.2024.04.014.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Valensise, H, Farsetti, D, Lo Presti, D, Pisani, I, Tiralongo, GM, Gagliardi, G, et al.. Preterm delivery and elevated maternal total vascular resistance: signs of suboptimal cardiovascular adaptation to pregnancy? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2016;48:491–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.15910.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Valensise, H, Pometti, F, Farsetti, D, Novelli, GP, Vasapollo, B. Hemodynamic assessment in patients with preterm premature rupture of the membranes (pPROM). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2022;274:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2022.04.027.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Valensise, H, Tiralongo, GM, Pisani, I, Farsetti, D, Lo Presti, D, Gagliardi, G, et al.. Maternal hemodynamics early in labor: a possible link with obstetric risk? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2018;51:509–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.17447.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Bhide, A, Acharya, G, Bilardo, CM, Brezinka, C, Cafici, D, Hernandez-Andrade, E, et al.. ISUOG practice guidelines: use of Doppler ultrasonography in obstetrics. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2013;41:233–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.12371.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Bahlmann, F, Reinhard, I, Krummenauer, F, Neubert, S, Macchiella, D, Wellek, S. Blood flow velocity waveforms of the fetal middle cerebral artery in a normal population: reference values from 18 weeks to 42 weeks of gestation. J Perinat Med 2002;30:490–501. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm.2002.077.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Bijl, RC, Valensise, H, Novelli, GP, Vasapollo, B, Wilkinson, I, Thilaganathan, B, International Working Group on Maternal Hemodynamics, et al.. Methods and considerations concerning cardiac output measurement in pregnant women: recommendations of the International Working Group on Maternal Hemodynamics. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2019;54:35–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.20231.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Valensise, H, Farsetti, D, Pisani, I, Tiralongo, GM, Lo Presti, D, Gagliardi, G, et al.. Friendly help for clinical use of maternal hemodynamics. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2021;34:3075–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2019.1678136.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Kager, CC, Dekker, GA, Stam, MC. Measurement of cardiac output in normal pregnancy by a non- invasive two-dimensional independent Doppler device. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2009;49:142–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-828x.2009.00948.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Namara, H, Barclay, P, Sharma, V. Accuracy and precision of the ultrasound cardiac output monitor (USCOM 1A) in pregnancy: comparison with three-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography. Br J Anaesth 2014;113:669–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aeu162.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Società Italiana di Ginecologia e Ostetricia. Monitoraggio cardiotocografico in travaglio. SIGO; 2018. Availble from: https://www.sigo.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/LG_MonitoraggioCardiotocoTravaglio_2018.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

29. Linn, S, Grunau, PD. New patient-oriented summary measure of net total gain in certainty for dichotomous diagnostic tests. Epidemiol Perspect Innovat 2006;3:11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-5573-3-11.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Riley, RD, Ensor, J, Snell, KIE, Harrell, FEJr, Martin, GP, Reitsma, JB, et al.. Calculating the sample size required for developing a clinical prediction model. Br Med J 2020;368:m441. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m441.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Kalafat, E, Barratt, I, Nawaz, A, Thilaganathan, B, Khalil, A. Maternal cardiovascular function and risk of intrapartum fetal compromise in women undergoing induction of labor: a pilot study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2019.10.1002/uog.21918Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Valensise, H, Novelli, GP, Farsetti, D, Vasapollo, B. Cardiac function. In: Lees, C, Gyselaers, W, editors. Maternal hemodynamics. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press; 2018.Search in Google Scholar

33. Janbu, T, Nesheim, B-T. Uterine artery blood velocities during contractions in pregnancy and labour related to intrauterine pressure. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol 1987;94:1150–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.1987.tb02314.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Dall’Asta, A, Brunelli, V, Prefumo, F, Frusca, T, Lees, CC. Early onset fetal growth restriction. Matern Heal Neonatol Perinatol 2017;3:2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40748-016-0041-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. Ramirez Zegarra, R, Dall’Asta, A, Ghi, T. Mechanisms of fetal adaptation to chronic hypoxia following placental insufficiency: a review. Fetal Diagn Ther 2022;49:279–92. https://doi.org/10.1159/000525717.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Bricker, L, Medley, N, Pratt, JJ. Routine ultrasound in late pregnancy (after 24 weeks’ gestation). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;2015:CD001451. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd001451.pub4.Search in Google Scholar

37. Grivell, RM, Alfirevic, Z, Gyte, GM, Devane, D. Antenatal cardiotocography for fetal assessment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;2015:CD007863. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007863.pub4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38. Kumar, N, Yadav, M. Role of admission cardiotocography in predicting the obstetric outcome in term antenatal women: a prospective observational study. J Mother Child 2022;26:43–9. https://doi.org/10.34763/jmotherandchild.20222601.d-22-00017.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

39. Galazios, G, Tripsianis, G, Tsikouras, P, Koutlaki, N, Liberis, V. Fetal distress evaluation using and analyzing the variables of antepartum computerized cardiotocography. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2010;281:229–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-009-1119-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Dall’Asta, A, Kumar, S. Prelabor and intrapartum Doppler ultrasound to predict fetal compromise. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2021;3:100479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100479.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Rhöse, S, Heinis, AM, Vandenbussche, F, van Drongelen, J, van Dillen, J. Inter- and intra-observer agreement of non-reassuring cardiotocography analysis and subsequent clinical management. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2014;93:596–602. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.12371.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2025-0329).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- The fetus as a patient in the 21st century: science, ethics, technology and global responsibility

- Vision, Education, and the Future of Perinatal Medicine

- Opening – field direction, education, and AI

- Quo vadis neonatologia? Where is neonatology heading in the 21st century?

- Shaping the future: advancing maternal-fetal medicine through educational standards and innovations

- Integrating generative AI in perinatology: applications for literature review

- Maternal Hemodynamics, Fetal Physiology, and Surveillance

- Core fetal physiology and maternal-fetal interaction

- Cardiac output-guided maternal positioning may protect the fetal oxygen supply and thereby reduce pregnancy complications

- Effect of antenatal betamethasone on fetal heart rate short-term variability in growth restricted fetuses

- Umbilical venous flow and maternal hemodynamics as predictors of impaired fetal growth in gestational diabetes: a prospective study

- The impact of maternal cardiovascular status prior to labor on birth outcomes: an observational study

- Complex Pregnancies, Placenta, and Fetal Therapy

- Twins, placental disease, fetal intervention, and periviability

- Complications in monochorionic twin pregnancies

- Association of discordance in birth weights of dichorionic twins with the incidence of preeclampsia in pregnant women

- Management and outcomes of periviable infants in Slovenia: a decade of experience

- Successful management of severe hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn (HDFN) due to anti-Kell

- Systems of Care, Screening, and Population-Level Perinatal Medicine

- Public health, structured care, and national data

- Structured stillbirth management in Slovenia: outcomes and comparison with international guidelines

- Newborn screening for rare diseases: expanding the paradigm in the genomic era

- Ten years of experience with screening for diabetes in pregnancy according to IADPSG criteria in Slovenia

- Gestational diabetes and fetal macrosomia: a dissenting opinion

- Advanced Prenatal Diagnosis

- Imaging and fetal anomaly detectionata

- Detection of isolated fetal limb anomalies using 3D/4D ultrasound

- Ethics, Professional Responsibility, and Patient-Centered Counseling

- The moral and communicative core of “Fetus as a Patient”

- The fetus as a patient: professional responsibility in contemporary Perinatal Medicine

- Placenta-oriented counseling: challenges and opportunities in obstetric practice

- Patient education materials: improving readability to advance health equity

- Global Health, Pandemic, and Humanitarian Perinatal Medicine

- COVID-19, war, immunity, and respectful care

- Clinical factors in SARS-CoV-2 antibody response in unvaccinated mothers

- Serum vitamin D and inflammatory markers in SARS-CoV-2 positive pregnant women

- Perceptions of respectful maternity care in Ukraine during a time of war

- Role of prelabour midwifery consultation in enhancing maternal satisfaction and preparedness for birth

- Obstetric Decision-Making and Postpartum Outcomes

- Clinical controversies and maternal outcomes

- Should we conduct a trial of labor in women with a macrosomic fetus?

- Postpartum maternal complications: a retrospective single-center study

- Annual Reviewer Acknowledgment

- Reviewer Acknowledgment

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- The fetus as a patient in the 21st century: science, ethics, technology and global responsibility

- Vision, Education, and the Future of Perinatal Medicine

- Opening – field direction, education, and AI

- Quo vadis neonatologia? Where is neonatology heading in the 21st century?

- Shaping the future: advancing maternal-fetal medicine through educational standards and innovations

- Integrating generative AI in perinatology: applications for literature review

- Maternal Hemodynamics, Fetal Physiology, and Surveillance

- Core fetal physiology and maternal-fetal interaction

- Cardiac output-guided maternal positioning may protect the fetal oxygen supply and thereby reduce pregnancy complications

- Effect of antenatal betamethasone on fetal heart rate short-term variability in growth restricted fetuses

- Umbilical venous flow and maternal hemodynamics as predictors of impaired fetal growth in gestational diabetes: a prospective study

- The impact of maternal cardiovascular status prior to labor on birth outcomes: an observational study

- Complex Pregnancies, Placenta, and Fetal Therapy

- Twins, placental disease, fetal intervention, and periviability

- Complications in monochorionic twin pregnancies

- Association of discordance in birth weights of dichorionic twins with the incidence of preeclampsia in pregnant women

- Management and outcomes of periviable infants in Slovenia: a decade of experience

- Successful management of severe hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn (HDFN) due to anti-Kell

- Systems of Care, Screening, and Population-Level Perinatal Medicine

- Public health, structured care, and national data

- Structured stillbirth management in Slovenia: outcomes and comparison with international guidelines

- Newborn screening for rare diseases: expanding the paradigm in the genomic era

- Ten years of experience with screening for diabetes in pregnancy according to IADPSG criteria in Slovenia

- Gestational diabetes and fetal macrosomia: a dissenting opinion

- Advanced Prenatal Diagnosis

- Imaging and fetal anomaly detectionata

- Detection of isolated fetal limb anomalies using 3D/4D ultrasound

- Ethics, Professional Responsibility, and Patient-Centered Counseling

- The moral and communicative core of “Fetus as a Patient”

- The fetus as a patient: professional responsibility in contemporary Perinatal Medicine

- Placenta-oriented counseling: challenges and opportunities in obstetric practice

- Patient education materials: improving readability to advance health equity

- Global Health, Pandemic, and Humanitarian Perinatal Medicine

- COVID-19, war, immunity, and respectful care

- Clinical factors in SARS-CoV-2 antibody response in unvaccinated mothers

- Serum vitamin D and inflammatory markers in SARS-CoV-2 positive pregnant women

- Perceptions of respectful maternity care in Ukraine during a time of war

- Role of prelabour midwifery consultation in enhancing maternal satisfaction and preparedness for birth

- Obstetric Decision-Making and Postpartum Outcomes

- Clinical controversies and maternal outcomes

- Should we conduct a trial of labor in women with a macrosomic fetus?

- Postpartum maternal complications: a retrospective single-center study

- Annual Reviewer Acknowledgment

- Reviewer Acknowledgment