“Stupid” German Money? Bonus Interest Rate Payments on Savings Deposits During the Stagflation of 1967 to 1984

-

Sebastian Knake

Dr. Sebastian Knake undertook his PhD studies at Bielefeld and Bayreuth University. His dissertationUnternehmensfinanzierung im Wettbewerb was published in 2020 in the seriesBeihefte zum Jahrbuch für Wirtschaftsgeschichte . Between 2015 and 2018, Knake was part of the research projectErsparte Krisen , funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Science. The above article originates from the follow-up projectThe Anticipation of Expectations that has been conducted at Bayreuth University from 2019 to 2023. It was funded by theDeutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) as part of its Priority Program 1859Experience and Expectation . Since 2023, Knake participates in the research projectHistorical Tensions that deals with the history of taxation of multinational companies and is funded by the Volkswagen Foundation.

Abstract

The deregulation of interest rates in 1967 gave West German banks the opportunity of price discrimination among their customers. In the savings deposit market, banks used secret bonus payments paid on top of the regular interest rate to compete for funds. This article explores the practice of bonus payments using two case studies: the Sparkasse Bielefeld (1970 to 1975) and the Volksbanken in Harburg county (1979 to 1984). Both cases are analyzed both qualitatively and quantitatively. Informed by the case studies, I estimate that between 10 and 20 percent of savings deposits in West Germany received bonus payments at the peak of this practice. Banks limited the extent of these payments primarily by exploiting and reinforcing a strong asymmetry in the price transparency between savings accounts and other financial assets. Thus, the main advantage of bonus payments for banks was the exclusion of uninformed savers with larger accounts rather than the exclusion of small savers.

1 Introduction

A 1974 banking journal article with the provocative headline Stupid customers as revenue buffers? criticized the practice of bonus payments that West German banks offered on savings deposits in the early 1970s. The anonymously penned article read:

“As is well known, the majority of banks award special gratifications to those customers who have 10,000 D-Mark or several times that sum in their savings accounts and who threaten to withdraw their funds. In these cases, the pressured teller offers – according to the market situation – 2, 3 or up to 5 percent bonus on the regular rate on standard savings accounts, if the precious customer agrees to keep the money in the account for three months. Of course, this behavior is absolutely compliant with market principles […]. However, the vast majority of banks only gratify those customers who actively demand such payments. Those, who quietly save up by themselves, even if their savings add up to 10 or 20,000 Mark, go empty-handed. A smart banker called this the stupid-customer revenue buffer.” [1]

In a nutshell, this quote describes all relevant aspects of the practice of bonus payments by German banks in the stagflation period. Especially, it points to the main rationale of these programs. Bonus payments made sense not because of those customers who participated, but because of those who did not. The quote also demonstrates that although bonus payments were kept secret by the banks, the market and some of the customers were generally aware of how these programs worked.

The bonus programs were part of a twofold pricing strategy for savings accounts. The other part of this strategy was the setting of a benchmark rate – the so-called Spareckzins. [2] Despite the fact that bank interest rates were deregulated in West Germany in 1967, the Spareckzins was not a market rate. Instead, changes in the benchmark rate were the outcome of a complex decision-making process with a political communication process at its heart. [3] However, deregulation opened a path for both owners of savings accounts as well as banks to opt out of the Spareckzins regime. For the banks, negotiating individual bonus payments on savings deposits was an opportunity to answer market pressures at minimum costs. For savers, it was a way to escape the rigidities of the benchmark rate and its most problematic feature: negative real interest rates. The losers of this arrangement were those savers who only earned the official Spareckzins.

Thus, research on the bonus programs might help explain a number of seeming paradoxes in German financial history during the stagflation period. Specifically, it can help answer the following questions: How were banks able to keep the benchmark interest rate negative in real terms despite the fact that bank interest rates were deregulated in 1967, [4] competition among banks for deposits had increased substantially [5] and West Germany had opted out of the Great Inflation resulting in positive real interest rates in most financial markets? [6] Why did savings deposits reach an all-time high during the stagflation period when measured as a share of household financial wealth even in the presence of alternative investments with positive yields? [7]

The extent of the bonus payments on savings accounts is unknown. In German historiography, the bonus programs of banks during the stagflation period are non-existent. While contemporary publications from the German Federal Bank (Bundesbank), [8] trade journals and media outlets knew of their existence, so far there are no published attempts to estimate the size and properties of bonus programs. The reason for this lack of research is simple. The bonus programs were bank secrets. Banks did not publish any data on them. Hence, it is all but impossible to reconstruct the size of bonus payments from official data. Nonetheless, this paper attempts to shed light on the practice via two case studies from local banks, using account-level and branch-level data.

The article is organized as follows: First, I discuss bonus payments within the framework of economic theory by utilizing the concept of price discrimination. Second, I present a historical overview on the retail deposit market in West Germany during the stagflation period with a special emphasis on price transparency in the retail market. I then present the two case studies: the bonus program practices of Sparkasse Bielefeld (1970 to 1975) and Volksbanken in Harburg County (1979 to 1984). The former was a large urban savings bank in Westphalia, while the latter was a network of local credit unions in a suburban/rural region just south of Hamburg. In both cases, an in-depth analysis of the historical development of the bonus programs is followed by an empirical analysis of their extent and deposit share. Finally, I present (rough) estimations for the overall size of the bonus programs in the West German banking system and the implications of bonus payments on deposit prices and the savings and investment behavior of German households. I conclude by summarizing the findings.

2 Bonus Payments as Price Discrimination

Within economic theory, the bonus programs can be understood as a form of price discrimination as defined by Arthur Pigou. [9] Price discrimination means that suppliers charge different prices for the same or at least similar goods or services. Scholars of the economics of price discrimination have recently focused on information and information costs. Michael Katz differentiates between two kinds of customers: [10] Informed customers make large purchases and buy from the store with the lowest price, while uninformed customers make small purchases at random stores. The price and quantity of purchase thus depend on the information level of the customer. Since only the informed customers are sensitive to price differentials, competition for informed customers is higher than for those uninformed. Michael Katz’ theoretical analysis has three central outcomes: 1. Output and profitability of firms rise after the introduction of discriminatory prices. 2. The introduction of price discrimination redistributes consumer rents from the uninformed customers to the informed ones. 3. The welfare effect of discriminatory prices depends on the ratio of uninformed customers: If this group is small, uniform prices are more efficient. If it is large, price discrimination might sometimes be the more efficient alternative.

While Michael Katz’ model did not include a mechanism for learning, an extended literature on search behavior and search costs in industrial organization economics provides dynamic concepts of information seeking behavior. [11] A prominent research topic in this literature are informational gatekeepers or clearinghouses (media, for example), that make price information available to the public. A related question is how large the group of informed customers must be in order for firms to change strategy. Looking at the impact of comparative internet searches on life insurance prices, Jeffrey Brown and Austan Goolsbee found that price dispersion decreased after the ratio of internet-informed customers reached five percent. [12] Another strand of literature deals with processes of learning via social networks, where customers are either rational or bounded rational. [13] In the latter case, a successful learning strategy depends on the properties of its information network. Network members usually learn from interacting with their friends, family or colleagues. Since search costs affect the seller’s ability to discriminate between customers, it might be valuable for firms to keep information costs as high as possible. In the literature, different strategies are discussed. [14] One way to increase information costs is to allow for haggling. Guillermo Marshall shows that if prices are personalized in wholesale markets, they can differ by as much as 70 percent. [15]

Numerous articles apply the concept of price discrimination to the market of retail finance. Jason Allen et al. show the impact of negotiated prices in the Canadian mortgage industry. [16] This research group found that mortgage lenders post an official common interest rate, while in fact, only 25 percent of new home buyers pay this official rate. While the leverage of the mortgage lender is the spread between the official rate and costs, the leverage of the borrower is the threat to choose competitive offers. However, the mortgage lender has considerable market power that originates from three sources: The home bank premium, which means that customers will visit their home bank first; a small number of competitors and, the existence of considerable switching costs that result from the integration of various financial services into one product. [17] Many empirical studies have proven the importance of bank loyalty and switching costs in the retail deposit market. [18] Accordingly, bank loyalty and switching costs effectively limit the effect of inter-bank competition on the customer level. [19]

In the following sections I will use the concepts and studies discussed here as a framework for the analysis of the bonus payment schemes.

3 The German Retail Deposit Market in the Stagflation Period of 1967 to 1983

The practice of bonus payments on savings accounts cannot be understood outside of the historical context of the West German retail deposit market during the stagflation period. Throughout the 1970s, the market for bank deposits was affected by the fundamental volatility in the domestic and world financial markets. The currency turmoil in the early 1970s and the strong rise in inflation forced the Bundesbank to increase its benchmark rates to all-time highs in the periods of 1970 to 1974 and again in 1979 to 1983. Simultaneously, the Federal Bank forcefully tightened liquidity requirements for German retail banks by increasing reserve requirements. The combination of these measures led to a strong rise in money market rates. By contrast, the interim years from 1975 to 1979 constituted a low-interest period. [20]

The volatility in the money market spilled over to the retail bank deposit market via time deposits. From the perspective of banks, retail time deposits acted as close substitutes for inter-bank deposits, because they could be acquired in large quantities for a limited period. Traditionally, the owners of time deposits were businesses who deposited excess liquidity. However, the customer base of time deposits expanded during the high-interest rate periods to include wealthy households. Among the Westphalian savings banks, the number of time deposit accounts rose from about 10,000 in 1970 to 170,000 in 1981. However, this was not a continuous process. According to statistics of the Westphalian savings banks, the numbers of accounts went down to pre-stagflation levels between 1975 and 1978. [21]

From the consumer perspective, there are a few differences between time deposits and savings accounts (also sometimes called passbooks or Sparbücher in German). A time deposit was a bank account with a fixed interest rate and a fixed maturity. A savings account had a variable interest rate and a notice requirement, which means that the owner had to inform the bank in advance of withdrawals. In practice, several exceptions and special arrangements bridged the differences between these two savings products. For example, savers could withdraw a certain amount of money from savings accounts without prior notice. As for time deposits, customers could choose some form of automatic prolongation of the investment. Interest rates on savings accounts did not change very frequently, while the interest rate on short-term time deposits changed with every reinvestment.

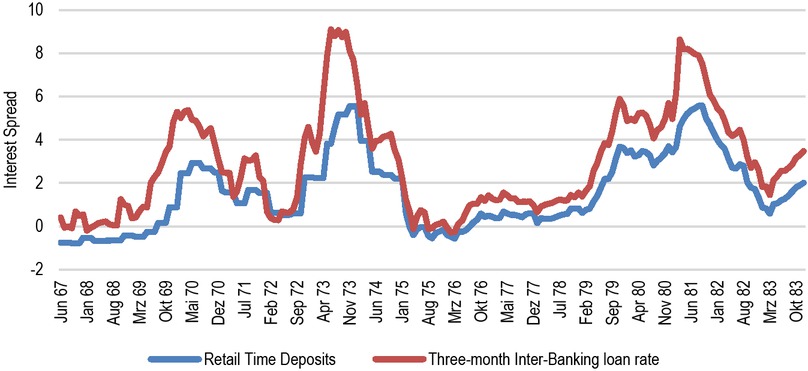

The main determinant of the private savings market in Germany was the Spareckzins. It constituted a uniform interest rate for standard savings accounts but also served as the benchmark for accounts with longer notices. The Spareckzins survived the deregulation of all bank interest rates in 1967. It was determined by recommendations of the federal associations of the major banking groups. [22] During high-interest-rate periods, the low sensitivity of the benchmark interest rate towards market rates created large interest spreads between savings deposits and other bank products, especially between savings and time deposits (see Figure 1). These large spreads made it attractive for retail investors to switch from savings to time deposits.

Interest Rate Spreads Between the Spareckzins and Money Market Rates. Note: Figure 1 shows the difference (spread) between two money market rates – the average rate on three-month retail time deposits and the three-month inter-banking loan rate – and the Spareckzins. Source: Bundesbank-Zinsstatistik, Habenzinsen der Banken (MFIs) in Deutschland (1967–2003).

However, banks had strong incentives to prevent large outflows from savings to time deposits for two reasons. First, time deposits required banks to hold more liquidity reserves relative to savings deposits. Hence, time deposits were more expensive for banks than savings deposits even without a positive interest spread. [23] Second, banks could not tolerate large outflows of savings deposits because they needed savings deposits to fund their long-term lending business. The German regulatory framework allowed banks to use 60 percent of their savings deposits as a source for refinancing long-term credits like mortgages. At the same time, banks could only use ten percent of time deposits for long-term loans. [24] During high-interest periods, many banks had problems to stay within the limits set by the liquidity rules. At the peak of the second high-interest period in July 1981, 70 percent of all savings banks had either reached or breached the limits of the liquidity requirements. [25] Already in 1979, the Federal Association of the Credit Unions (Bundesverband der Volksbanken und Raiffeisenbanken) issued a warning to all member banks to take the liquidity situation seriously. [26] The need to meet the official liquidity rules led to fierce competition for saving deposits during both high-interest-rate periods.

One way to prevent outflows from savings accounts to time deposits was to limit access to the latter. Most banks imposed minimum investment requirements. Since these requirements were discrete decisions of individual banks, there is no published evidence on their size. However, it seems to have been common knowledge among informed observers that the requirement was usually around 10,000 D-Mark. [27] While this requirement excluded the vast majority of savers from switching to time deposits, it did not exclude the bulk of savings deposits. [28] Among the savings banks, more than half of the total value of savings deposits were invested in accounts worth 10,000 D-Mark and more. The share of these large accounts increased to two thirds by the early 1980s. [29]

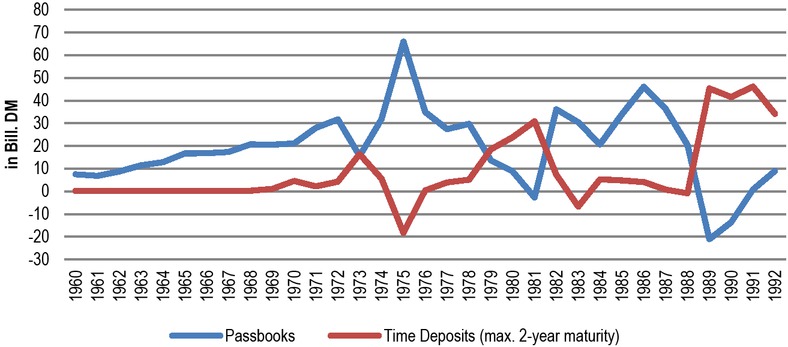

For owners of large accounts there was no formal barrier to use time deposits as substitutes for savings deposits and vice versa. Over time, more and more customers did so. As Figure 2 demonstrates, there were considerable flows between savings accounts and time deposits during the stagflation period. However, these flows did not lead to a convergence of the interest rate on time deposits and the Spareckzins, mainly because all banks feared for their profitability. Instead, they found another way to bridge this conflict of interest: they took advantage of the differences in transparency of the markets for savings accounts and time deposits.

Net Flow of Funds among Savings Accounts and Time Deposits (Households). Note: Annual nominal changes in the volume of savings deposits and short-term time deposits. Source: Bundesbank, Finanzierungsrechnung nach ESVG 1995.

3.1 Price Transparency in West German Retail Banking

According to the theoretical literature reviewed above, one of the crucial prerequisites of a successful price discrimination strategy is the existence of a sufficiently large group of uninformed customers. What did German consumers know about retail deposit interest rates? In the 1970s, the market research company EMNID conducted several surveys asking customers about their knowledge of interest rates on savings accounts. [30] Though the results of these surveys are somewhat difficult to interpret, [31] roughly half of the respondents could give the correct answer on the official interest rate on savings accounts. Additionally, the respondents seemed to have recognized the increased volatility of the interest rates during the first half of the 1970s. By 1976, about half of the participants were aware of the trend of interest rate movements. This share had been considerably smaller in the first surveys of the early 1970s. Overall, retail customers were relatively well informed about the rates on savings accounts. [32]

When it comes to other retail deposit rates, the question of market transparency is much more complicated. Regarding time deposits, there is little data on even the ownership rate during the research period. The existence of minimum investment requirements, however, limited the potential investor pool. Official income and consumer statistics unfortunately subsumed time deposits under the category of “other financial assets” (“Sonstiges Geldvermögen”). In 1983, around the peak of time deposit popularity, 6.7 percent of all households owned at least one asset in this category, while time deposits made up about six percent of household financial wealth. Before, time deposits had been less important, making up only less than two percent of household financial wealth in 1976 and the ownership rates being significantly lower. [33]

The relatively small number of owners and the short holding periods both led to a slow speed of the spread of information on time deposits. Near the peak of time deposit popularity, the Soll und Haben survey, conducted in 1980, examined the information behavior of respondents regarding financial assets. According to the survey, only seven percent of respondents had acquired information on time deposits. This compares to 20 percent who had searched for information on longer-term savings accounts and 19 percent, who had sought information on building society contracts. [34] Since many of the better-informed customers either already owned or later bought a time deposit account, it is doubtful that more than ten percent of households knew about the interest rate level on the money market in Germany even at the peak of the second high-interest rate period.

The reasons for this information gap concerning the different deposit options were manifold. First, there was no single interest rate for time deposits. Interest rates differed not only from institution to institution, but also between small and large deposits and between short or long-term maturities. The banks acknowledged this reality soon after the deregulation of bank interest rates in 1967. The recommendations of federal associations that generally determined bank interest rates did not include time deposits. [35] In 1973, the Federal Association of Savings Banks (Deutscher Sparkassen- und Giroverband or DSGV) noted in a report on competitive prices in the banking sector, that comparisons of time deposit rates were not possible even in local markets, since individual banks preferred to determine interest ranges instead of interest rates. [36]

However, banks not only capitalized on this information asymmetry, they created and reinforced it through their position as important information brokers in the financial market. According to the aforementioned Soll und Haben survey, bank employees were used by half of all households for financial advice in 1980, reaching the importance of family members and far exceeding all other information sources including friends (23 percent) or newspapers (20 percent). [37] Thus, banks had a large influence on the spread of information regarding the prices of financial assets. By withholding information, banks were able to slow down the speed of its spread.

Yet, compared to the bonus programs, time deposits can be considered to have been a transparent market. The Bundesbank published a monthly average rate, as well as the range of interest rates on three-month-time deposits with a delay of about three months. [38] On bonus payments, neither the Bundesbank nor the banks themselves published anything. As I will show below, sometimes not even the management of individual banks knew the exact extent of these programs. They were among the best-kept secrets of the banks that I will try to reveal in the following section.

4 Two Case Studies on Banks’ Secret Bonus Programs

Because of the secrecy of the bonus programs, there are only a few hints about their prevalence in the German banking system during the stagflation period. The only reliable sources are consecutive statements in the internal periodical interest rate surveys by the Federal Association of Savings Banks (Deutscher Sparkassen- und Giroverband or DSGV) that covered all retail banking groups. In the survey of January 1974, the association found that the vast majority of savings banks and credit unions had introduced the practice of bonus payments to customers. [39] By contrast, the survey found that the large national and the regional commercial banks were more reluctant to grant bonuses. [40] The last mention of bonus payments in these regularly conducted surveys from the first high-interest period dates from December 1974. [41] From 1975 to 1978, most bonus programs seemed to have been temporarily discontinued.

However, they returned in the second high-interest period between 1979 and 1983. In 1981 and 1982, 60 percent of all savings banks reported the regular practice of bonus payments. [42] As to their extent, I found only rumors of certain cases. In early 1981, the president of the DSGV internally named examples of savings banks that made bonus payments on 10 to 20 percent of their overall deposits as extreme examples of the again fast-spreading practice of bonus payments. [43] Like in the previous high-interest period, the savings banks were not the only banks that introduced bonus payments. Deutsche Bank, as an example of large commercial banks, also operated bonus programs in this period. [44] As shown below, bonus payments were also prevalent among credit unions (Volksbanken) in rural areas.

These few hints offer a basic framework from which to derive informative case studies. First, bonus payments were widespread especially among savings banks and credit unions. Second, the above information offers a detailed periodization of the application of this practice. Most banks only temporarily introduced bonus programs during the two high-interest periods and canceled them in between.

The two case studies presented below fit well into this framework. The first case study concerns the bonus program of Sparkasse Bielefeld from 1970 to 1975. Sparkasse Bielefeld was (and still is) among the largest savings banks in Germany. [45] The size of Sparkasse Bielefeld came by way of a merger in 1974 of three formerly independent institutions: Kreissparkasse Bielefeld operating in Bielefeld County, Stadtsparkasse Bielefeld situated in Bielefeld City and Stadtsparkasse Brackwede. Since Sparkasse Bielefeld originated from both city and county savings banks, it represents the majority of savings banks customers. [46]

The second case study analyzes bonus payments of several Volksbanken in Harburg County from 1979 to 1984. This case is also representative for the German credit unions. Harburg County, just south of Hamburg, is a traditionally rural county whose most northern parts transformed into a suburban area of Hamburg during the research period. Harburg had 184,000 inhabitants in 1980. The only two towns, Buchholz and Winsen, had between 20,000 and 30,000 inhabitants in the 1970s. The rest of the county consisted of smaller independent municipalities that were merged into larger entities in 1972. None of Harburg’s credit unions were active in the entire county. Instead, twelve credit unions had subdivided the territory into smaller parts, mostly consisting of one or two municipalities. In addition, the Harburg credit unions had on average 47 million D-Mark in assets in 1978. The average for all credit unions in West Germany was 50 million D-Mark in the same year. From both the business and the geographical perspective, the Harburg Volksbanken constitute an almost perfectly representative sample for this banking group. [47]

Apart from their representative character, the main reason for the choice of the two case studies was source-driven. For both cases, I found qualitative and quantitative sources. This coincidence allowed me both to reconstruct the bank-internal rationale behind the bonus programs and to measure their size and structure. For the qualitative analysis, I use a large variety of sources. For the empirical analysis, I use branch-level data for the Bielefeld case and account-level data for Volksbank Rosengarten in Harburg country.

4.1 Case 1: The Bonus Program of Sparkasse Bielefeld (1970 to 1975)

The bonus program of Sparkasse Bielefeld began in 1970 and ended in the spring of 1975, with a hiatus between 1971 and 1973. In creating the bonus program, the bank built on practices prevalent in the market for time deposits. [48] At Kreissparkasse Bielefeld, the first mention of negotiated time deposit rates can be found in a memo of the central management to all branch managers in July 1969. [49] The memo confirms the failure to establish benchmark interest rates in the market for time deposits via the practice of nationwide interest rate recommendations. This represents the first attempt of Kreissparkasse Bielefeld to establish some general procedures or ground rules for negotiated interest rates. While it is possible that special arrangements with individual customers existed before, they seemed to have been so rare that the bank’s management did not intervene.

While the first cases of negotiated interest rates occurred in the market for time deposits, the focus soon shifted to savings deposits. In March 1970, the central management acknowledged that the outflow of money from savings to time deposits constituted a threat to the bank’s business. The management demanded that branch managers look more closely at the origin of new time deposits: they were to determine if funds came from outside the bank or from already existing accounts inside the bank. In the latter case, the bank would be reluctant to make any special arrangement for time deposits. [50] The branch managers shared the concern of the central management. They found that the existing large interest spreads between savings accounts and time deposits caused owners of the former to move their funds to the latter and they feared that this trend would accelerate, if the interest spread would continue. [51]

In response to this development, Kreissparkasse Bielefeld allowed their branches to offer bonus payments on savings accounts for the first time in the summer of 1970. At a branch manager meeting in September 1970, the management established general guidelines for bonus payments on savings deposits. The most important rule was that the total interest (regular + bonus) should not exceed the rate on short-term time deposits. [52] Later, the bank specified a period of 30 days as the typical duration of a bonus agreement. [53] However, branch managers were still able to offer different conditions by means of individual negotiations with the bank management.

The general size of the bonus program in 1970 is unknown. The only quantitative evidence comes from the Spiegelstraße branch that in its quarterly report from October 1970 stated that it had paid bonus interest rates to 50 customers (about 1 percent of the total customer base or on 5 percent of the branch’s savings deposits respectively). [54] In the following years, Spiegelstraße was among the branches with the most extensive bonus programs of Sparkasse Bielefeld. We can assume that the ratios were significantly smaller for the entire Kreissparkasse Bielefeld.

From the numbers of the Spiegelstraße branch, it seems that accounts that received bonus payments were large compared to the average account size. The lowest amount mentioned in the reports was 10,000 D-Mark – although this case was singled out as an example of how common bonus payments had become.

Though small in both outreach and financial terms, the bonus program was deemed necessary and important. Over the course of the year 1970, the growth rate of savings deposits had slowed considerably, while time deposits increased significantly. This development had serious consequences for the bank’s lending business. In January 1971, a bank manager noted that the volume of already approved long-term loans required the bank to increase the flow of savings deposits in 1971 fourfold compared to 1970. Otherwise, Kreissparkasse Bielefeld would have breached the official liquidity requirements. [55]

However, the liquidity squeeze was short-lived. During the year 1971, Kreissparkasse Bielefeld witnessed strong inflows of savings deposit, following a downward trend in the general interest rate level. In 1972 and early 1973, the rates on time deposits were closer to the level of the official Spareckzins. Consequently, the bank cut down on bonus payments. [56] Now, bonus payments were no longer mentioned in the internal papers of the bank. Only in 1973 did bonus payments return as a major topic. In their reports for the first quarter of 1973, branch managers again noticed increased outflows from savings accounts to time deposits. [57] By the second quarter of 1973, bonus payments had again become a tool in the internal and external competition for savings deposits.

In the second quarter of 1973, the branch managers recognized a change in the composition of the group of customers that demanded higher interest rates. Instead of handling a few cases via individual negotiations with professionals and entrepreneurs, the branch managers faced a large number of ordinary savers who were informed (or, in the eyes of the managers, “excited” (“angeregt”)) by the media or by friends and acquaintances on the possibility for higher yields. [58] The informed customers demanded bonus payments from their bank either by threat of switching to time deposits or by switching to a competitor. As for the latter threat, many branch managers directly named their competitors and the amount of deposits to be lost. [59] The bank management did not object to the loss of deposits in cases where other banks offered significantly higher rates. [60] Kreissparkasse Bielefeld was more concerned about the threat to switch to time deposits.

When evaluating the spread of information, branch managers expected the demand for bonus payments to increase even more in the following months. [61] By July 1973, the bank management reminded branch managers that the bank should prioritize savings deposits over time deposits. Branch managers were asked to answer customer demands for time deposits with offers of bonus payments on savings accounts. [62]

According to the sources, branch managers likewise favored bonus payments on savings accounts rather than offering time deposits – for different reasons. The manager of a rural branch stressed the importance of the haptic feeling of an actual savings book, which only the savings account offered to customers, and which created a stronger bank-customer relationship than did the time deposit. However, the most important argument in favor of the bonus payment was the fact that it did not alter the general investment pattern of the customer. [63] After the expiration of the bonus agreement, the investor was not forced to make any decisions or changes on their principal investment (e.g. the savings account). The temporary nature of the bonus program reveals the expectations of bank and branch managers alike. They expected the high-interest period to end at some point in the near future and a return to the previous status quo. The bonus program was explicitly designed to help the bank and its customers through a short period of relative crisis.

However, as the high-interest period continued through 1973 and most of 1974, it looked like the bonus program would evolve from an interim to a permanent feature of the bank’s product line. This development was seen as a major threat to the bank’s profitability. Early on, some branch managers had recognized this long-term risk of the bonus program.

In a memo from October 1973, one manager pointed out the fact that so far, only 30 of his branch’s savings account holders had received bonus payments. [64] However, in total, some 90 accounts worth more than 10,000 D-Mark were potentially eligible. Altogether these high-net-worth savers amounted to half of his branch’s savings deposits. He concluded that the bank would run into trouble if all eligible savers eventually received these payments.

From the second half of 1973, the Sparkasse Bielefeld addressed the expansion and spiraling costs of the bonus program. On the administrative side, the growth of the program demanded measures of rationalization. In the first half of 1973, bonus payments were organized in the same way as in 1970, when there were only a few cases per branch. After repeated demands from branch managers, the bank introduced standardized procedures, like the provision of printed forms for bonus agreements. [65] In February 1974, the newly merged Sparkasse Bielefeld took decisive steps to standardize the bonus program. The central management issued detailed, mandatory rules for bonus payments for the entire bank. Most of these rules existed before, but this was the first attempt to integrate all rules into one comprehensive framework.

The new framework confirmed 30 days as the default period for bonus payments, as well as monthly time deposits as the benchmark for bonus payments. The most important innovation within the framework was a mechanism that automatically prolonged the bonus agreement for 30-day periods indefinitely until one of the parties terminated the agreement. This feature came along with another innovation. With every automatic extension, the bonus was automatically adjusted to the current interest rate for monthly time deposits. [66] The standardization had become necessary, because bonus payments were now too common to treat them as individual arrangements.

In March 1974, only one month after the introduction of the automatic extension of bonus payments, Sparkasse Bielefeld took further measures, this time addressing the financial consequences of the program. In a meeting, the bank managers confronted the branch managers with the high costs of the bonus program. The bonus payments had increased the overall interest expenditure on savings deposits by between seven and ten percent. The central managers informed the branch managers that a reduction of effective interest rates on savings deposits by 0.5 percent would increase bank revenues by seven million D-Mark per annum. [67]

To reduce the costs of the bonus program, the bank prohibited new bonus agreements except for justifiable, individual cases. In an effort to exercise more control, the management required that branch managers report exact figures on bonus payments for savings accounts. This announcement carried the implicit threat to expose branches that had been too generous with bonus payments. [68] In May 1974, the bank management informed branch managers about the results of the first reports. They presented branch level data on the average interest rate on savings accounts with different maturities, as well as the average interest rate for the entire bank. The numbers confirmed the suspicion of the central management that branches diverged considerably regarding the extent of their bonus payments. [69]

The evaluation process put enormous pressure on some branch managers. This is why their reports for the first quarter of 1974 contain extensive explanations and justifications regarding the bonus program. Many managers pointed to the small number of accounts that received bonus payments. They stated that all owners of these accounts were well informed about bonus payment practices and expected interest rates equivalent to those for time deposits; the bank would lose customers and large quantities of savings deposits to competitors, if branches were forced to reduce bonus payments. [70]

Interestingly, this expectation was falsified by the customer reaction to several cuts in the bonus program in the second half of 1974. In June 1974, the bank decided to decouple the bonus payments from the interest rate on time deposits. [71] In July, the central management announced the termination of the automatic extension program in September (even though it had only installed it a few months earlier). A small survey conducted by Sparkasse Bielefeld on bonus systems by various banks in Bielefeld had previously concluded that all other Bielefeld banks had already terminated their automatic extension programs by July 1974. [72] In August, the bank issued a standard letter for all customers who were the recipients of bonus payments, announcing that the automatic prolongations would end. At the same time, the bank encouraged its customers to think about long-term investments and invited them to seek advice at their local branch. [73]

The bank’s new bonus program strategy turned out to be a success. Much to the surprise of branch managers, most customers held on to their savings accounts despite the still-existent gap between savings deposit and time deposit yields. [74] Contrary to branch manager expectations, customers also accepted the end of the automatic bonus program without many complaints. [75] One branch manager found that only those customers were disappointed, who had expected the high interest period to continue indefinitely. [76] These customers were the exception. Reports for the third quarter of 1974 suggest that most customers had acknowledged the trend of falling interest rates. As is shown in Figure 1, the spread between retail time deposits and the Spareckzins halved in the first half of 1974 and virtually disappeared in the second half of that year. In mid-1974, both informed customers and Sparkasse Bielefeld expected rates to continue falling and the spread between time deposits and savings deposits to disappear.

By August 1974, a reduction in costs was evident in branch data reports. The bonus program was winding down. [77] In November 1974, the bank increased the minimum deposit that made an account eligible for bonus payments from 10,000 to 20,000 D-Mark. [78] In reports for the fourth quarter of 1974, branch managers reported that most bonus payments had been discontinued. No branch manager reported any problems with the phasing-out of the program. In February 1975, the bank terminated all new bonus agreements. From March 1 onwards, extensions on existing bonus payments and the agreement of new ones was prohibited without exception. [79] Previous bonus payment recipients were relegated to being ordinary savers again under the rule of the Spareckzins.

Sparkasse Bielefeld: Empirical Findings

The main data sources for the case study of Sparkasse Bielefeld are the mandatory branch reports on bonus payments from March and August 1974. [80] The bank management evaluated these reports and presented their results to branch managers in internal memos in May and September, respectively. However, the memos only contained branch level data on the average interest rate on savings accounts, subdivided by the respective periods of notice. Neither the share of bonus deposits nor of the accounts receiving bonus payments were reported.

The most notable insight from the data is that the bonus program increased the average interest rate considerably. In March 1974, the bank paid an effective rate of 6.2 percent on standard accounts, while the official rate was at 5.5 percent. For savings accounts with a negotiable notice period, the difference was even higher. For accounts with 12-month-notice, the actual rate was 8 percent or one percent higher than the official rate.

As noted above, only accounts worth more than 10,000 D-Mark were eligible for bonus payments. The existence of this minimum investment requirement was confirmed by the aforementioned survey from June 1974, not only for Sparkasse Bielefeld, but also for all banks located in the city. [81] The average deposit size of accounts with negotiable notice periods was more than twice the size of average deposits on standard accounts, according to a survey among German savings banks in 1974. [82] Thus, negotiable notice accounts were far more likely to be eligible for bonus payments than standard accounts. Overall, the effective rate on all savings deposits was 0.8 percent higher than the weighted average of the official interest rates. [83]

Sparkasse Bielefeld did not report the ratio of savings deposits with a bonus to all deposits. However, I estimate the ratio as the difference between the effective and the official interest rate. Since the historical analysis has shown that the bank used the rate on monthly time deposits as the benchmark for bonus payments, I assume that all bonus payments are equal to the gap between the official rate on the respective savings account and the rate on monthly time deposits. I then estimate the ratio of bonus accounts in each account category. Finally, using the size of each account category as weights, I come up with the overall ratio of bonus accounts.

A methodical problem is the dependence of the time deposit rate on the size of the deposit. A larger sized account earned a higher interest rate. Since account level data is not available, there is no possibility to estimate the ratio of accounts of each size category. Instead, I use two scenarios: First, I assume that all bonus accounts are between 10,000 and 20,000 D-Mark, for which the January rate on time deposits is 9.5 percent. I then assume that all bonus accounts have a size between 20,000 and 50,000 D-Mark for which the rate is 10 percent. Since it is very unlikely that bonus accounts are dominated by sizes of more than 50,000 D-Mark, I do not calculate the ratio using interest rates for this size category.

In the first scenario, the ratio of bonus deposits to all savings deposits is 22 percent. In the second scenario, it is 18 percent. As expected, the ratio is much higher for accounts with negotiable notice periods than for standard accounts. However, since deposits on standard accounts make up two thirds of all savings deposits, standard accounts have the highest overall share among bonus deposits. They are closely followed by accounts with a one-year notice period. Other savings accounts are negligible.

Bonus Payments on Savings Accounts at Sparkasse Bielefeld: Share of Total Savings Deposits.

| Savings account (type) | Amount (in mn. D-Mark) | Interest (Official rate) | Interest (Actual average rate) | Share of bonus deposits (9.5%overall rate) | Share of bonus deposits (10% overall rate) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | 755 | 5.5 | 6.1 | 15.0 | 13.3 |

| 12-months | 287 | 7.0 | 7.9 | 36.0 | 30.0 |

| 48-months | 100 | 8.5 | 8.8 | 30.0 | 20.0 |

| Total | 1,142 | 6.1 | 6.8 | 21.6 | 18.1 |

Note: Share of bonus deposits to all savings deposits at Sparkasse Bielefeld as of February 1974. The share of bonus deposits at 9.5% overall rate presents the results of the first scenario, where the combination of official interest and bonus amounts to the rate on short-term time deposits with less than 20,000 D-Mark. The share of bonus deposits at 10% overall rate presents the results for the interest rate on time deposits with between 20,000 and 50,000 D-Mark. Source: Rundschreiben der Sparkasse Bielefeld Nr. 76/1974 vom 03.05.1974, in: HASB AIV3/62.

As a robustness check, I now look at data mentioned in the quarterly branch reports. In the first quarter of 1974, ten branches reported the ratio of bonus deposits to all deposits. The reported weighted average is 21 percent, which is clearly within the range estimated above. To find out if the ten branches are representative, I compare their reported effective interest rates to Sparkasse Bielefeld as a whole. Overall, the weighted average interest rate of the ten branches is in line with the effective interest rate of the entire bank. Thus, the estimated size of the bonus program of Sparkasse Bielefeld is roughly 20 percent of all deposits, and the estimation is robust.

Weighted Average Actual Interest Rate of Sparkasse Bielefeld and Ten Reporting Branches.

| Interest rate | 3-months | 12-months | 48-months |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sparkasse Bielefeld | 6.2 | 8 | 8.9 |

| 10 reporting branches (weighted average) | 6.3 | 8 | 8.9 |

Source: Quartalsberichte der Zweigkassenleiter der Sparkasse Bielefeld, Year 1974, in: HASB AII/3/116.

I now turn to the number of accounts that received bonus payments. Since I do not have bank-wide numbers, I use information from the quarterly branch reports. In the first quarter of 1974, nine branches reported exact numbers for bonus accounts. Taken together, these branches made bonus payments on four percent of all savings accounts. Again, I check that the nine reporting branches are representative for the bank as a whole. Similar to deposits, the weighted average of the nine branches show effective interest rates very similar to the entire bank. Thus, it can be assumed that the overall number of bonus accounts is roughly four percent. As expected, this ratio is much lower than the ratio of bonus deposits. At the peak of the bonus program in early 1974, Sparkasse Bielefeld offered bonus payments on 4 percent of all savings accounts, representing roughly 20 percent of overall savings deposits.

4.2 Case 2: Bonus Programs of Volksbanken in Harburg County (1979 to 1984)

The three largest Volksbanken in Harburg County (in Rosengarten, Nordheide and Buchholz) all had bonus programs during the stagflation period. [84] Combined, the three banks represented about half of the savings deposits of all Harburg credit unions. While I did not find evidence for the other credit unions, this does not mean that they did not use bonus payments. Source material is generally extremely scarce for the smaller banks in this period. In addition, while their small size probably made the introduction of formal bonus programs unlikely, they still could have paid higher interest on savings accounts on an individual basis. Concerning periodization, I only found evidence of regular bonus payments for the second high-interest period.

In November 1979, Volksbank Nordheide allowed its branches to offer bonus payments for the first time and issued detailed operating procedures on bonus payments to employees. [85] These new procedures were published in the so-called Arbeitshandbuch, which specified several general requirements for agreements on bonus payments. First, the bank clarified that special interest agreements regarding savings deposits were only allowed in the form of bonus payments on top of the regular rate. [86] Second, bonus payments were only allowed on accounts that met the minimum requirements for time deposits (at least 10,000 D-Mark). [87] Third, the bank prohibited bonus payments that would push the overall interest rate of savings deposits above the rate of time deposits. Fourth, agreements should have a maximum maturity of 90 days. During this period, the bank prohibited withdrawals from the bonus account. [88] In a separate memo, the bank urged its managers to only consider bonus payments as a last resort and explicitly prohibited any kind of marketing. [89] The instructions hinted at the secrecy of the bonus payments. The bank prohibited handing out any written record of the agreement to customers. The management also instructed employees to keep quiet about the fact that the bonus payments would be extended to newly deposited money on the same account. [90]

Just a few months later, the bank management found the established general rules to be too restrictive. In February 1980, branch managers were encouraged to become more active with bonus payments to prevent outflows of savings deposits. As a concrete measure, branch managers were allowed to reduce the minimum requirement and extend the maximum period of bonus payments to two years. [91] One reason was strong external competition from the local savings bank that reportedly offered bonus payments and high interest on time deposits. The other reason was internal competition from the bank’s time deposits that caused large outflows from savings accounts. The threat from both internal as well as external competition was amplified by a simultaneous trend of concentration of savings deposits at Volksbank Nordheide in fewer but larger accounts. [92]

The bonus program at Volksbank Nordheide thus shared the same rationale of the bonus program at Sparkasse Bielefeld in the earlier period. Both were a defensive measure to halt the outflow of funds from savings accounts to other accounts at the bank or to a competitor.

Volksbank Rosengarten: Empirical Evidence

While the quantitative evidence on the bonus program of Volksbank Nordheide is rather limited, I found detailed account-level data on the bonus program of Volksbank Rosengarten. The account level data originates from handwritten records that were part of the internal annual audits of Volksbank Rosengarten. I found complete records for the years 1979, 1982, 1983 and 1984. [93] Unfortunately, there were no records for 1980 and 1981. The records feature the account number, the name of the account owner, the size of the account, the agreed-upon bonus, the agreed-upon period and the actual interest payment in the respective year.

Table 3 shows the evolution of the bonus program at Volksbank Rosengarten. While barely significant at the end of 1979, the bonus program soon reached a notable share of the bank’s deposit base. However, the share of bonus deposits did not reach 10 percent and the share of accounts stayed below two percent.

Bonus Accounts at Volksbank Rosengarten (1979–1984).

| Year | Number of accounts | Share of total savings accounts | Share of total savings deposits |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | 35 | 0.2 | 1.3 |

| 1982 | 300 | 1.6 | 8.9 |

| 1983 | 196 | 1.0 | 6.2 |

| 1984 | 208 | 1.0 | 6.2 |

Source: See FN 93.

The dataset includes only few cases of multiple ownership of bonus accounts. In 1982, when the bonus program was at its peak, there were only 24 cases where one customer owned multiple bonus accounts. Given that the practice of owning multiple savings accounts was widespread, especially among wealthy savers, this finding is rather surprising. [94]

Another interesting feature of the bonus program of Volksbank Rosengarten is the changing composition of customers. Overall, the turnover was quite large. Only six of the 35 recipients of bonus payments in 1979 still received payments in 1982. However, in 1983, 55 percent of bonus program customers had already profited from bonus payments in 1982 (for another 4 percent, participation in 1982 is likely). 41 percent of customers had not received bonus payments the year before. In 1984, the stability of the customer base was even higher. This implies that bonus payments were becoming a more stable feature for customers over time.

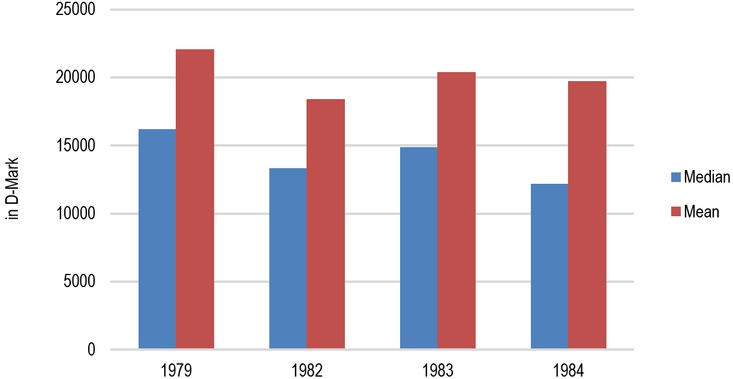

A closer look at the account sizes reveals several interesting insights (see Figure 3). The mean size of accounts went down from 22,000 D-Mark in 1979 to about 18,000 D-Mark in 1982. In the following years, it increased again. The median account size also decreased from 16,000 D-Mark in 1979 to 13,000 D-Mark in 1982 and increased again in 1983. These numbers show that Volksbank Rosengarten offered bonus payments to large accounts first, but lowered its requirements as the high-interest rate period progressed, allowing for a stronger participation of owners of medium-sized accounts.

Mean and Median Value of Bonus Accounts at Volksbank Rosengarten. Note: Own Calculation. Source: See FN 93.

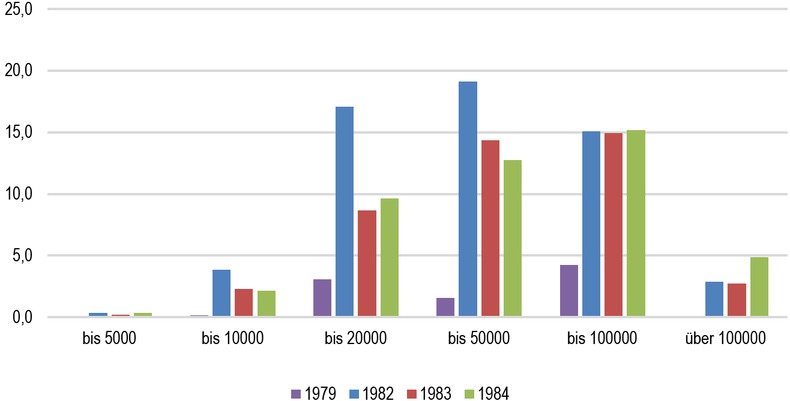

However, the increasing participation of owners of medium-sized financial wealth did not lead to any kind of democratization of bonus payments. The data confirms the significance of the 10,000 D-Mark lower bound for bonus payments.

In 1982, the share of accounts with less than 10,000 D-Mark to all bonus accounts was roughly 25 percent, while the share of deposits on these accounts to all bonus deposits was about 7 percent. Since almost all savings accounts of Volksbank Rosengarten (94 percent) were worth less than 10,000 D-Mark, the share of bonus accounts to all accounts of this size was insignificant (0.4 percent). The share of bonus accounts to all accounts worth more than 10,000 D-Mark was 20 percent. Bonus accounts worth less than 10,000 D-Mark were thus an extremely rare exception. The significance of the required minimum is bolstered by the fact that there were almost no bonus accounts worth less than 5,000 D-Mark.

When further differentiating bonus accounts worth more than 10,000 D-Mark (see Figure 4), the result is rather surprising: the share of bonus accounts to all accounts does not necessarily increase with the size of the accounts. The typical account size with the largest share of bonus accounts in 1982 was between 20,000 and 50,000 D-Mark. In that year, the share of bonus accounts to all accounts worth 10,000 to 20,000 D-Mark was higher compared to those worth more than 50,000 D-Mark. However, in the following years, the share of bonus accounts and deposits in the middle categories decreased sharply, while the share in the higher-sized categories remained stable. This change hints at receding pressure to offer bonus payments on mid-sized accounts.

Share of Bonus Deposits to all Deposits (among different size categories) in percent. Note: Own Calculation. Source: See FN 93.

Finally, neither the number of bonus accounts nor the share of bonus deposits exceeded 20 percent of the total in any size category in any year (with only one exception). Even among the largest account holders, those customers who were well-informed about bonus payment practices of their bank were a rather small minority.

5 The Bonus Programs during the Stagflation Period: General Findings

Having taken an in-depth look at the bonus programs at exemplary banks, I find that the bonus programs in the stagflation period seem to have been a reaction to changes in the demand of only a fraction of their customers. The first bonus agreements were concluded at the branch level in sporadic direct interactions between customers and bank personnel. The most important underlying economic cause was the emergence of large spreads between the interest rates on savings deposits and those on retail time deposits. The longer this rate-spread continued, the more common bonus payments became. Eventually, they reached a volume that led banks to standardize the procedures around bonus payments, turning them into full-fledged bonus programs. However, the system retained its temporary nature and continued to exclude as many customers as possible.

The final aim of this article is to estimate the extent of the bonus programs for West German banks. I estimate the importance of bonus payments as being somewhere between the bonus program of Sparkasse Bielefeld in 1973/1974 and that of Volksbank Rosengarten in 1979 to 1984. The program in Bielefeld peaked in 1974, when roughly 20 percent of all savings deposits received bonus payments. Rosengarten granted bonus payments to nine percent of savings deposits in 1982. This leads me to believe that West German banks probably granted bonus payments on about 10 to 20 percent of deposits at the peak of both high-interest periods.

Given the total value of savings deposits in West Germany, the ratios amount to between 30 and 60 billion D-Mark worth of deposits receiving bonus payments in 1974. In 1981, the value rose to between 50 and 100 billion D-Mark. This compares to increases in time deposits of about 40 billion D-Mark from 1969 to 1974 and about 80 billion D-Mark between 1979 and 1982. Thus, the bonus programs effectively halved the outflow from savings to time deposits.

At the same time, bonus payments extended to only a small fraction of savings accounts. At the peak of the programs, only between 1.5 and 4 percent of savings accounts received bonus payments. However, the savings banks alone had issued more than 65 million passbooks by 1980, which means that the savings banks made bonus payments on between one million and 2.6 million savings accounts. [95] This compares to 650,000 new time deposits that savings banks had issued in the last high-interest period.

From a theoretical perspective, the bonus programs integrated several elements of price discrimination as discussed above. The historical and empirical analysis confirms the importance of the 10,000 D-Mark minimum investment requirement. However, if small accounts are excluded, the relationship between account size and access to bonus programs vanishes. While the threshold of 10,000 D-Mark effectively excluded about 80 percent of customers, it excluded only a third of deposits. If all deposits worth more than 10,000 D-Mark had received bonus payments, the programs would have applied to savings deposits worth more than 200 billion D-Mark in 1974 and about 350 billion D-Mark in 1982. Had this been the case, it would have been more efficient for banks to end the bonus programs and raise the official interest rates on savings deposits to a level that would stop the outflow.

However, this is not a mere theoretical assumption. Branch managers and banking group officials believed that the success of the bonus program did not depend on the exclusion of small savers. For the bonus program to be profitable, it was crucial to exclude the majority of eligible customers.

In the early 1980s, the Federal Association of Savings Banks (Deutscher Sparkassen- und Giroverband or DSGV) repeatedly discussed replacing bonus payments with a system of interest rates based on account size. In a memo, the DSGV calculated that a bonus of only one percent on accounts above 10,000 D-Mark would cut the operating profit of the entire savings bank organization by a quarter. Given that the actual bonus payments were much higher (see section 4.1 above), the proposed new system would have risked the Sparkassen’s general profitability. In addition, the DSGV feared a race to the bottom as competition with credit unions would decrease minimum requirements. Any official bonus payments would result in a substantially higher interest rate for all savings accounts. [96]

So how did the banks manage to exclude the majority of large account holders from the bonus programs? The best answer is that banks made it incredibly difficult for customers to ask for bonus payments. One of the most important features of the bonus programs was that banks kept them secret. There was no official information on these programs and not even the federal banking associations knew of their true extent. In the absence of any official information, negotiations between customers and bank employees required substantial knowledge about prices on several deposit markets, bank policies concerning quantities and the guts to start negotiations with bank experts in the first place. The historical analysis on the bonus program of Sparkasse Bielefeld hints at the communication channels that carried the information on bonus programs. According to the branch managers, customers learned about bonus payments via newspaper articles or from friends, colleagues or acquaintances.

Interactions with friends and family are considered as the most important channel of social learning. [97] However, this way of learning usually takes a long time to diffuse through the entire population of a society. As for the media, they did play a role in accelerating the learning process. However, their effectiveness as information clearinghouses was impeded because they could not publish exact information. Even the news outlets had to rely on hearsay. [98]

Blurred information on bonus payments stood in stark contrast to the highly publicized benchmark interest rate or Spareckzins. Communication with the public actually drove the changes in this benchmark rate. [99] The banks’ communication strategies on interest rates on savings accounts differed fundamentally between the official rate and an unofficial bonus rate. In addition, most bonus programs were discontinued between 1975 and 1979. During this low-interest interim period, the Spareckzins was not just the official, but also the actual benchmark rate for all savings accounts. All in all, the communication strategy of banks and the interruption of the bonus programs during low-interest periods worked against a fast diffusion of knowledge about these programs among customers. Banks successfully exploited and reinforced the large information asymmetries between the market for savings deposits and the other financial markets by discriminating not merely against small account holders but primarily against the uninformed owners of large accounts.

6 Conclusion

This article uncovered the widely used practice of price discrimination among West German banks during the stagflation period that hitherto had been largely unknown. Given the lack of any data or meaningful general information, I used a bottom-up approach by generalizing from my findings on two case studies. Future research on other case studies can clarify, correct or even falsify my estimates. However, there is an upper limit on the size of these programs set by their rationale. Thus, the qualitative research on the motives of the respective banks also had important implications for the quantitative estimates.

The key finding on the bonus programs is that it was not sufficient for banks to exclude small savers from these programs. The programs were only efficient, because banks were able to exclude the majority of the owners of large accounts. The “stupid customer revenue buffer” was produced mainly by the total secrecy of these programs, which stood in stark contrast to the widely publicized official interest rate on savings accounts, i.e. the Spareckzins.

From an international perspective, this dual track information strategy of West German banks sharply contrasted with the experience in the United States. In another paper, I have shown how differences in the structure of the banking system and in the timing of deregulation led to a far higher ratio of informed American customers. Once market-rate savings deposits became available in the US, many more savers profited from the high interest levels of the stagflation period than did their German counterparts. [100] This difference had profound long-term consequences. The German banking system survived the stagflation period generally intact, while the American savings institutions suffered heavy losses from persistent negative interest margins. On the customer side, German households kept their savings accounts for several decades, while their US counterparts switched to more profitable investments. [101]

However, by the end of the stagflation period, the bonus programs seem to have reached the limit of their effectiveness: exactly because they were beginning to be common knowledge. Information on the bonus programs had reached enough people that a commentator in the Zeitschrift für die gesamte Kreditwirtschaft (ZGK) was able to blame customers for not taking advantage:

“Hans Joachim Krahnen [the former CEO of Bethman Bank] has criticized the practice of bonus payments for its discrimination between two classes of customers, namely those who trust the officially stated interest rates and those who are in the know and are confident in their negotiation skills. This criticism seems justified although one could argue that, due to the daily consumer education by the media on bank prices of all kinds, continued ignorance should be understood as a form of gross negligence on behalf of the uninformed.” [102]

The increased market transparency had several consequences. First, bonus payments did not disappear after 1983. The program of Volksbank Rosengarten was actually larger in 1984 than in 1983 (see Table 3). Second, many banks introduced special savings accounts or certificates that directly derived from the experience of bonus payments, but did not operate in secrecy, like the “saving for wealth” (Vermögenssparen) program. [103] Non-secret bonus payments – mostly in the form of special accounts – became a common feature of the German deposit market in the 1980s. In 1986, the Bundesbank started a new statistical series on so-called special savings accounts (“Sondersparformen”) that reported the size of deposits on passbooks with special agreements. In 1986, the share of these special savings accounts to all savings deposits was about 20 percent. In 1989 it reached 30 percent and in the mid-1990 it peaked at 60 percent. [104] The “stupid-customer revenue buffer” had finally disappeared.

About the author

Dr. Sebastian Knake undertook his PhD studies at Bielefeld and Bayreuth University. His dissertation Unternehmensfinanzierung im Wettbewerb was published in 2020 in the series Beihefte zum Jahrbuch für Wirtschaftsgeschichte. Between 2015 and 2018, Knake was part of the research project Ersparte Krisen, funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Science. The above article originates from the follow-up project The Anticipation of Expectations that has been conducted at Bayreuth University from 2019 to 2023. It was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) as part of its Priority Program 1859 Experience and Expectation. Since 2023, Knake participates in the research project Historical Tensions that deals with the history of taxation of multinational companies and is funded by the Volkswagen Foundation.

© 2025 Sebastian Knake, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Obituary for Eckart Schremmer

- Special Issue Articles

- Epidemics and Pandemics in Economic-historical Perspective – An Introduction

- Cholera in the City of Poznań: Did the Death Toll of the 1866 Cholera Epidemic Reflect Social and Economic Differences?

- The Mortality Impact of Cholera in Germany

- When Diseases Return from the Epidemiological Honeymoon: The Reemergence of Smallpox in 19th Century Germany and its Lessons for Public Health Policies after COVID-19

- On the Economic Costs of the Spanish Flu Pandemic in Germany: An attempt at Assessing GNP Lost for 1918

- Malaria in Catania/Sicily: Local Manifestations and International Scientific Cooperation During a Pandemic in the 1920s

- Geographical Aspects of Diphtheria in England and Wales: Immunisation and the Spatial Sequence of Retreat to Effective Elimination, 1921 to 1964

- Pandonomics: Why Economics was Unprepared for COVID-19-Policies

- Research Forum

- “Stupid” German Money? Bonus Interest Rate Payments on Savings Deposits During the Stagflation of 1967 to 1984

- Geography and Space in Recent Economic History

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Obituary for Eckart Schremmer

- Special Issue Articles

- Epidemics and Pandemics in Economic-historical Perspective – An Introduction

- Cholera in the City of Poznań: Did the Death Toll of the 1866 Cholera Epidemic Reflect Social and Economic Differences?

- The Mortality Impact of Cholera in Germany

- When Diseases Return from the Epidemiological Honeymoon: The Reemergence of Smallpox in 19th Century Germany and its Lessons for Public Health Policies after COVID-19

- On the Economic Costs of the Spanish Flu Pandemic in Germany: An attempt at Assessing GNP Lost for 1918

- Malaria in Catania/Sicily: Local Manifestations and International Scientific Cooperation During a Pandemic in the 1920s

- Geographical Aspects of Diphtheria in England and Wales: Immunisation and the Spatial Sequence of Retreat to Effective Elimination, 1921 to 1964

- Pandonomics: Why Economics was Unprepared for COVID-19-Policies

- Research Forum

- “Stupid” German Money? Bonus Interest Rate Payments on Savings Deposits During the Stagflation of 1967 to 1984

- Geography and Space in Recent Economic History