On the Economic Costs of the Spanish Flu Pandemic in Germany: An attempt at Assessing GNP Lost for 1918

-

Tobias A. Jopp

Tobias A. Jopp is a researcher at Technische Universität Bergakademie Freiberg. He studied economics at Universität Münster and completed his PhD in economics at Universität Hohenheim in 2012 with a study entitledInsurance, Fund Size, and Concentration: Prussian Miners’ Knappschaften in the Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Centuries and Their Quest for Optimal Scale (Berlin 2013). He held a number of academic positions in the Department of History at Universität Regensburg (2011–2024), where he completed his habilitation thesis in 2019 (T.A. Jopp , War, Bond Prices, and Public Opinion: How Did the Amsterdam Bond Market Perceive the Belligerents’ War Effort During World War One, Tübingen 2021). He held temporary positions in the departments of economics at Universität Hohenheim (2013/2014) and Universität Mannheim (2021/2022) before he joined theInstitut für Wirtschafts- und Technikgeschichte (IWTG) in Freiberg in October 2024. His publications address the history of social insurance, quantitative mining history, financial history, aviation history, and the history and methods of historiography. Most recently he wrote:T.A. Jopp/M. Spoerer , Civil Aircraft Procurement and Colonial Ties: Evidence on the Market for Jetliners, 1952–1989, in: Journal of Transport History 45/3, 2024, pp. 492-521.

Abstract

Evidence on the economic costs of the Spanish flu pandemic between 1918 and 1920 in Germany is still scarce. An analysis of the second-largest German sickness fund at the time, which covered mineworkers in the Ruhr area, helps assess two types of short term costs to the German economy in 1918, the first, and worst, year of the pandemic: the direct monetary costs to the health insurance system arising from excess sick claims; and, by combining morbidity evidence on the fund’s membership with a distributional perspective, the loss in overall economic performance. For 1918, total excess health costs are estimated at 0.1 percent of gross national product (GNP). The estimated GNP loss due to flu-related excess sick leave in 1918 is 1 percent, which accounts for about one third of the overall decline in GNP by –2.7 percent. This estimate can serve as a historical benchmark for a pandemic’s impact on a large, developed economy when globalization effects are largely absent.

1 Introduction

The recent COVID-19 pandemic hit the world economy severely, although with notable cross-country differences in crisis exposure. [1] According to the German Statistical Office’s initial estimations, German gross domestic product (GDP) dropped by around five percent in 2020 – a drop slightly less steep than the one due to the financial crisis in 2009. [2] The more integrated with the global economy a country like Germany was at the onset of the pandemic, the more severely it was affected. [3] Hence, it is not surprising that COVID-19 has once again raised serious questions about our knowledge of the underlying socioeconomic consequences of a pandemic in a globalized world and our ability to manage a pandemic well enough in light of the principle trade-off between personal freedom and personal (health) security. [4]

COVID-19 has revived academic interest in the economic costs of historical pandemics, especially in costs associated with the Spanish flu, which ravaged much of the world between 1918 and 1920 and is considered the deadliest pandemic to date. [5] While, for example, Robert Barro, Richard Burdekin, Marco Del Angel et al., François Velde, as well as Gustavo Cortes and Gertjan Verdickt study the Spanish flu’s effects on the U.S. economy, Mario Carillo and Tullio Jappelli analyze disparities in economic growth across Italian regions, Enrico Berbenni and Stefano Colombo focus on macroeconomic indicators for the Italian economy, Christian Dahl et al. trace income effects on the level of Danish municipalities, and Lars-Fredrik Andersson and Liselotte Eriksson analyze data on Sweden for household risk strategies in response to the pandemic. [6] In contrast, Robert Barro et al., Brian Beach et al., Sergi Basco et al. and Pierre Siklos take a global view; [7] while the studies by Barro et al. and Beach et al. include estimates of GDP lost by country, those by Basco et al. and Siklos investigate the pandemic’s effects on inequality and globalization, respectively. [8]

However, with a few exceptions we are still lacking comparable investigations into the economics of the Spanish flu in the German case. [9] While Kristian Blickle argues, quite generally, that the Spanish flu significantly contributed to the Nazi’s electoral success in the last Weimar elections, by cutting public spending options of cities that were highly exposed to the flu, Stefan Bauernschuster et al. analyze the relationship between Weimar election results and voters’ perception of health competence among politicians. [10] Richard Franke finds evidence for the State of Baden of a negative relationship between income and excess flu mortality (and a positive one between air pollution and mortality) in the short term. [11]

The most comprehensive investigation of the Spanish flu’s effect on German economic performance is the international study by Robert Barro et al. [12] In their sample period (1901 to 1929) and based on data for 48 countries, they model GDP growth as a function of combat- and flu-related deaths. Their estimate for a typical country’s flu-related reduction in real GDP over the combined years (1918 to 1920) is minus six percent; for the German case, their parameter estimates predict a flu-induced negative growth rate of around -2.3 percent over that three-year period. [13]

Instead of a top-down approach like Barro et al., this paper proposes an alternative bottom-up approach to assess the Spanish flu’s impact on national economic performance in the short term. Specifically, information on the second-largest German sickness fund at the time is used to assess short term costs to society in the pandemic’s first (and worst) year 1918. The direct monetary costs to the German health insurance system from flu-related excess sick claims are estimated, and, combining morbidity evidence with a distributional perspective, estimates of GNP lost are also presented. The focus on GNP instead of GDP is due to data availability. The sickness fund studied is the Allgemeiner Knappschaftsverein zu Bochum (AKV) [14] which ran a social health insurance scheme for most mineworkers in the Ruhr area, one of Germany’s major industrial centers.

The AKV’s publicly available administrative reports include a piece of insurance information that is pivotal for an analysis of GNP lost due to the pandemic. This insurance information is cause-specific sick claims made by the insured miners in combination with data on the cause-specific mean duration of sickness. This information is a necessary ingredient in the estimation of workdays lost among the working population due to the flu; and, in turn, foregone workdays are the basis for establishing an informed estimate on GNP lost when assessed from the perspective of the functional income distribution. [15]

It is worth stressing that the data on cause-specific sick claims and the mean duration of sickness are not available in the published aggregate statistics on health insurance; [16] and full information is not contained in the records of other large social sickness funds like the Allgemeine Ortskrankenkasse für die Stadt Berlin (Berlin’s local sickness fund was the largest German sickness fund as of 1914) or the Allgemeine Ortskrankenkasse München (Stadt) (Munich’s local fund was the third-largest German sickness fund as of 1914). [17]

To assess GNP lost for Germany from a distributional perspective, it is necessary to make extrapolations to higher levels of aggregation based on data for the Ruhr miners. Such extrapolations are ambiguous because the typical miner of the time was not necessarily representative of the average wage earner or health-insured person nationwide. Apart from the potential problems arising from such extrapolations, one aspect of the German health insurance system’s organization at the time imposes a natural restriction to this approach. This aspect is the health insurance system’s coverage, which amounted to around 50 percent of the working population, meaning that the morbidity of the uninsured half is even more difficult to study. [18]

The findings are as follows: firstly, total excess health costs in 1918 are estimated at 0.1 percent of GNP. Secondly, and more importantly, the loss in 1918 GNP due to flu-related excess sick leave is estimated at 1 percent, thus explaining about one third of the drop in GNP from 1917 to 1918 (which was -2.7 percent in total). This amounts to 43 percent of the decline in GNP over the combined years 1918 to 1920 as predicted by Robert Barro et al.’s model. [19]

The appeal of having an estimate for GNP lost for 1918 – and not merely for the entire flu pandemic period from 1918 to 1920 – largely stems from the fact that in 1918 Germany had a large, developed economy, which was almost completely cut off from international markets due the Allied naval blockade established early in the war. [20] Thus, the observable decline in GNP must have been rooted in domestic factors in the short term. Our estimate can therefore serve as an argumentative starting point for disentangling the domestic and international impact of a pandemic like COVID-19 on countries well integrated into the world economy.

The study proceeds as follows: Section Two provides historical and source background. Section Three is dedicated to estimate the short term economic costs of the Spanish flu. Section Four offers a critical discussion, and Section Five concludes.

2 Sources and Data

2.1 Historical Background on the Allgemeiner Knappschaftsverein (AKV)

The Knappschaften (KVs) served as the primary institutions managing the German miners’ occupational social insurance scheme. They had existed in this form, for example in Prussia, since 1854. Because the KVs’ insurance scheme has recently been the subject of intense research, the following overview based on the relevant literature is kept brief. [21]

The AKV was borne out of a merger of the two largest KVs in the Ruhr coal district in 1890. [22] The merger’s primary purpose was to create an insurance fund large enough to qualify as a so-called special insurer (Besondere Kasseneinrichtung) carrying Bismarckian pension insurance. [23] The Invalidity and Old-Age Insurance Act of 1889 provided for the possibility of admitting special insurance funds to cover specific groups of clients, in addition to the newly established provincial insurance institutions (Provinzialversicherungsanstalten) as the organizational basis of pension insurance. In 1889, this option was primarily of interest to those insurers which were already running occupational social insurance schemes in the mining, railroad, and maritime shipping sectors. [24]

The AKV’s special position in the German social insurance system was rooted in a distinctive organizational feature to be found only among the miners’ funds, namely its unique triple function as a social insurance provider. In addition to the miners’ occupational scheme, which continued to exist after the introduction of Bismarckian social insurance, the AKV also provided Bismarckian health insurance and, as the aforementioned special insurer, also Bismarckian invalidity and old-age insurance. [25] While all other KVs provided health insurance, too, only a few of them offered, as a special insurer, Bismarckian invalidity and old-age insurance.

Between 1890 and 1913, the AKV’s membership increased from just under 129,000 active miners to 443,000. Conscription during the First World War temporarily reduced the number of insured active miners to less than 300,000 (those drafted received an inactive status). [26] With the reorientation of wartime economic policy in 1916 (based for example on the famous Hindenburg program), many miners were recalled from the front to help boost coal production, so the number of active insured miners rose again to 380,000 by late 1918. [27]

The AKV provided insurance coverage for almost all miners employed in the Ruhr region to the right of the River Rhine [28] and impressed by its sheer size: in 1913, the AKV was the largest single sickness fund in the German Empire. Table 1 shows the different carriers of health insurance as of 1914 (by which point the AKV had fallen to second place).

Organizational Structure of the German Health Insurance System (as of 1914).

| Type of sickness fund | Number of funds | Number of insured | Mean fund size | Total health expenditures | Sick pay (part of Total health expenditures) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local funds | 2,788 | 9,714,396 | 3,484 | 326,569,949 | 112,481,588 |

| (Ortskrankenkassen) | |||||

| Provincial funds | 595 | 2,096,211 | 3,523 | 32,339,231 | 4,779,058 |

| (Landkrankenkassen) | |||||

| Company funds | 5,524 | 3,408,196 | 617 | 129,582,358 | 54,597,974 |

| (Betriebskrankenkassen) | |||||

| Guild funds | 947 | 390,783 | 413 | 14,001,388 | 4,826,740 |

| (Innungskrankenkassen) | |||||

| Miners’ funds | 146 | 916,081 | 6,274 | 45,575,600 | 20,705,400 |

| (Knappschaftskrankenkassen or Knappschaftsvereine; KVs) | |||||

| Thereof Allgemeiner | – | 388,385 | – | 20,574,219 | 11,184,678 |

| Knappschaftsverein (AKV) | |||||

| Total | 10,000 | 16,525,667 | 1,653 | 548,068,526 | 197,390,760 |

Note: Total health expenditures include administration costs. Monetary figures in marks. Sources: Kaiserliches Statistisches Amt (Ed.), Statistisches Jahrbuch für das Deutsche Reich 1917, Vol. 38, Berlin 1917, p. 104; Statistisches Reichsamt (Ed.), Statistisches Jahrbuch für das Deutsche Reich, Vol. 41, Berlin 1920, pp. 202-204; Allgemeiner Knappschaftsverein zu Bochum, Verwaltungs-Bericht des Allgemeinen Knappschaftsvereins zu Bochum für das Jahr 1914, Bochum 1915, pp. 41, 58-59.

The following observations about health insurance are important. Most sickness funds were small; the average fund had only about 1,700 members. However, altogether, most insured people were insured in such small and local sickness funds. The miners’ funds were on average larger than the other sickness funds. The AKV accounted for more than half of the sick pay disbursed by all KVs taken together (which was disproportionately high, when measured in terms of the ratio of insured people). The AKV budgeted more than half of total expenditure for sickness benefits, while the local funds, for example, budgeted only slightly more than one-third. In absolute terms this contribution was larger than that of all the rural and guild sickness funds combined, which in absolute numbers represented a collective of insured people that was larger than the KVs’ by a factor of seven. This probably reflects a clear disparity in daily wages in favor of the miners, but possibly also a substantial difference in the effective frequency and length of sickness.

2.2 The AKV’s Administrative Reports

The AKV’s administrative reports (Verwaltungsberichte) have only rarely been used as sources when studying the epidemiological impact of the Spanish flu. [29] However, as mentioned in the introduction, they contain valuable data on the course of the pandemic from the miners’ perspective, especially on morbidity, which is usually studied less extensively for many countries, including Germany, due to lack of data.

The reports were published annually between 1890 and 1921. They consist of two parts, namely a shorter text part, presenting the main financial and non-financial results of the year under review in a sort of narrative form, and a much longer statistical part, containing the tables for all social insurance branches run by the AKV. The 1918 report, used as the primary source for this study, has a text section with 43 pages (including some charts and a two-page health report), while the statistical section covers 384 pages. [30] Only a few explanatory notes are given on data processing, which is a highly inconvenient feature of the source, especially because several tables in Part Two do not allow for unambiguous interpretation.

The key variables used in this study are reported in the statistical part. The 1918 report is divided into seven sub-sections: I. Statistics on pension recipients and pension contributions in the Pension Fund (Statistik über die Rentenempfänger und Rentenbeiträge in der Pensionskasse), II. Statistics on pension recipients and pension amounts in the Disability and Survivors’ Insurance Fund (Statistik über die Rentenempfänger und Rentenbeträge in der Invaliden- und Hinterbliebenenversicherungskasse), III. Statistics on the causes of invalidity (Statistik über die Invaliditätsursachen), IV. Statistics on deaths (Statistik über die Todesfälle), V. Statistics on medical treatment (Statistik über das Heilverfahren), VI. Statistics on active members (Statistik über die aktiven Mitglieder), and VII. Statistics on diseases (Statistik der Erkrankungen). In some cases, the offered statistical data is recorded at the level of the collective of insured miners, in other cases at the level of the mining districts (Bergämter) or of individual mines. Most data are referring to the year (this holds for all data reported on the district- and mine-levels); in a few cases, the granularity of reporting is higher, for example, monthly data is presented for the sick and death cases.

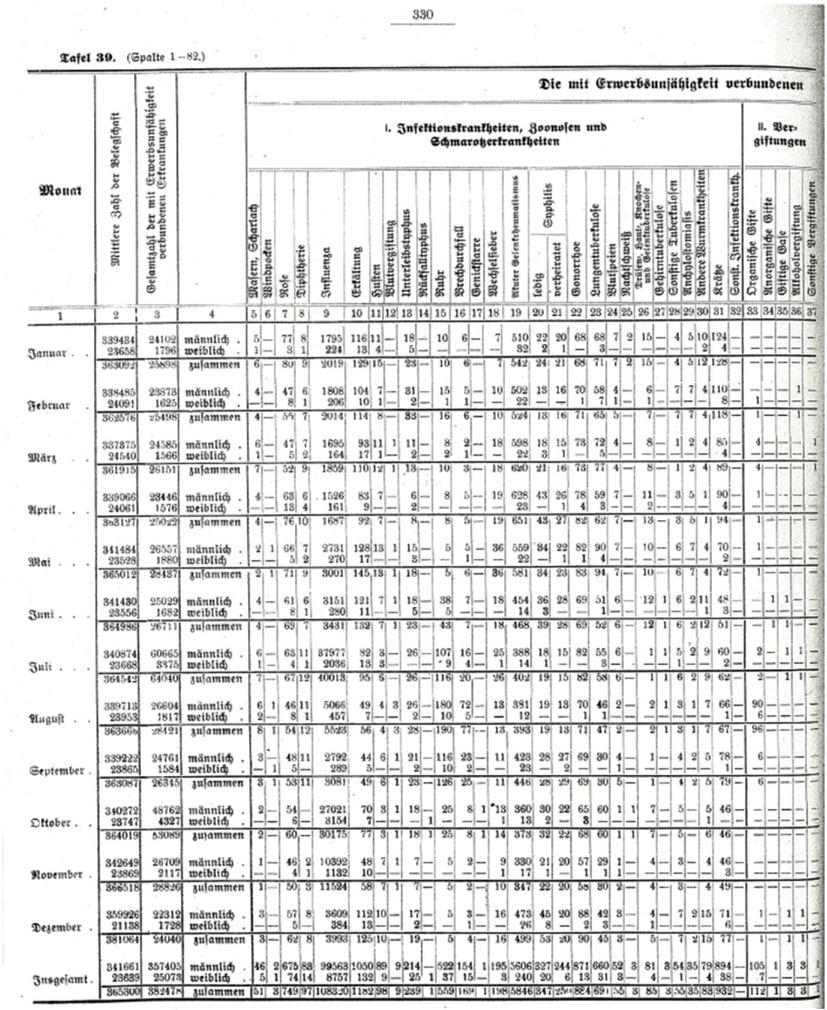

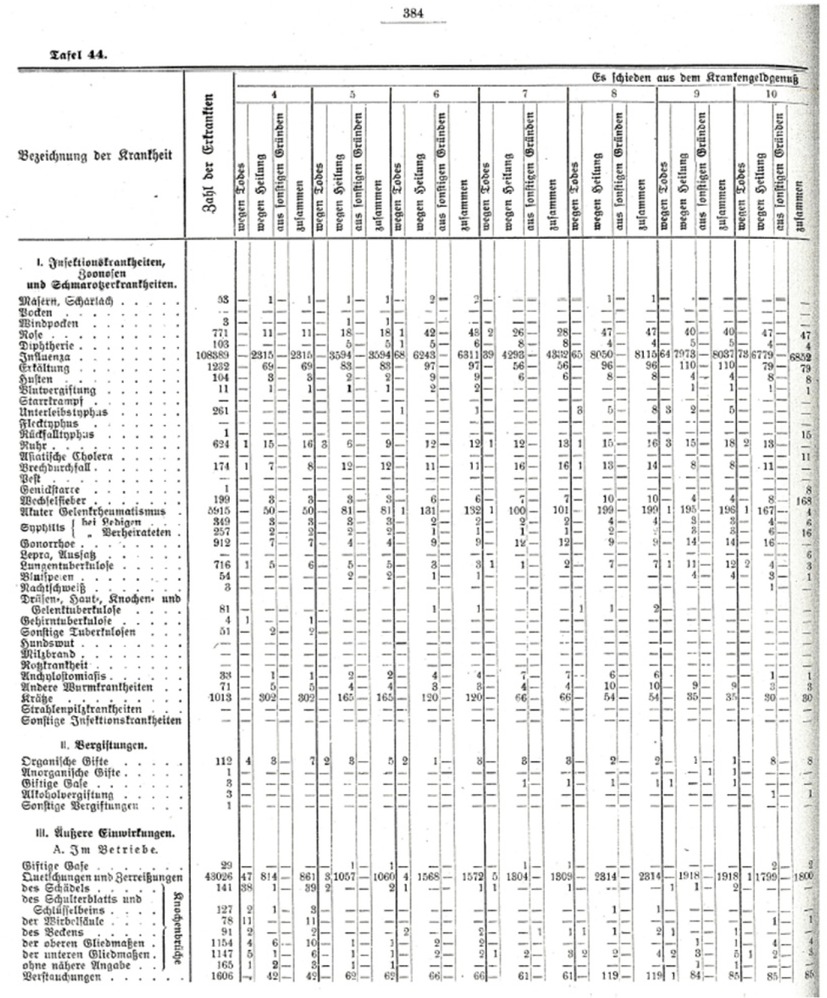

The information needed for the analysis below is taken from tables providing data on the level of individual members in the sub-chapter on diseases, where the cause-specific incidence of sick cases was recorded by month as well as the duration of the cause-specific length of sickness conditional on how the sickness ended (by year). Figures 1 and 2 illustrate how both statistics look in the original publication; the Spanish flu (influenza here) is reported under the header infectious diseases (column 9 in Figure 1; or disease number six in Figure 2).

Monthly Statistics on Sick Cases by Cause for 1918. Note: Shown is the statistics’ first page out of four pages in total. Source: Allgemeiner Knappschaftsverein zu Bochum, Verwaltungs-Bericht 1918, p. 330.

Annual Statistics on the Duration of Sickness by Cause for 1918. Note: Shown is the statistics’ first page out of 16 pages in total. Source: Allgemeiner Knappschaftsverein zu Bochum, Verwaltungs-Bericht 1918, p. 384.

2.3 The Ruhr Miners’ Pandemic Experience

How did the Ruhr miners fare in the pandemic? A natural starting point for insight is the AKV’s health report for 1918. The report’s tone is strikingly unemotional given the outstanding increase in mortality and infection rates evidenced by the compiled statistics. It reads that “[…] the main causes of high morbidity are the two widespread epidemics of influenza. This disease alone caused 40,013 and 30,175 cases of sickness in the two peaks of its development, in July and October respectively”. [31] Given the hardship for the miners and their families following the rapid spread of the Spanish flu, one might expect more empathetic words.

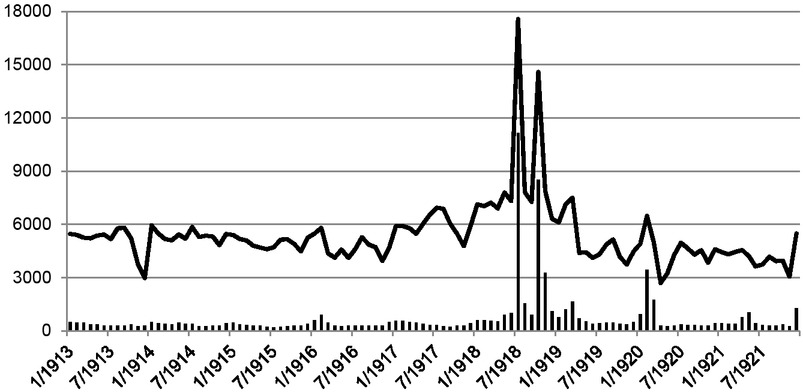

Figure 3 illustrates the severity of the Spanish flu in terms of infections. Two comments on the data on cases of sickness are in order: Firstly, following widespread practice in the historical literature on the Spanish flu, pneumonia cases are counted as flu-related as well; and, secondly, the AKV’s report is not clear on whether the reported cases of sickness are new cases or existing cases (i.e., new cases plus cases carried over from previous months). Following an earlier study of mine, I assume sick cases to reflect incidence (new cases only) and not prevalence (existing cases). [32] Furthermore, the incidence among the AKV’s membership cannot be traced beyond 1921 for two reasons: Firstly, no report was published for 1922, which, secondly, may have been connected to the merger of all KVs into the new Reichsknappschaft around that time; in other words, the AKV ceased to exist at the end of 1922 as a stand-alone sickness fund. As of 1923 it was a regional branch within the Reichsknappschaft.

Monthly Influenza Incidence Rate among AKV members (Jan. 1913 to Dec. 1921). Note: The incidence rate shows crude sick cases per 100,000 insured miners. All-cause incidence is indicated by a line, and combined influenza and pneumonia incidence by bars. Source: Jopp, Spanische Grippe, p. 108.

The most important takeaway from Figure 3 is that July 1918 and October 1918 stand out as the most precarious months, with flu incidences of 11,000 and 8,300 cases per 100,000 insured miners, indicating that no fewer than between eleven and eight percent of the active members fell ill. In addition, four more months show extraordinary incidence rates as well: November 1918 (3,100), March 1919 (1,600), February 1920 (3,300), and March 1920 (1,700). [33] In the highlighted peak months, the all-cause incidence rate was clearly driven by the Spanish flu. It should be stressed that a similar depiction of the monthly occurrence of infection for either the German population as a whole or the population of a particular German state does not seem to be available in the literature. [34]

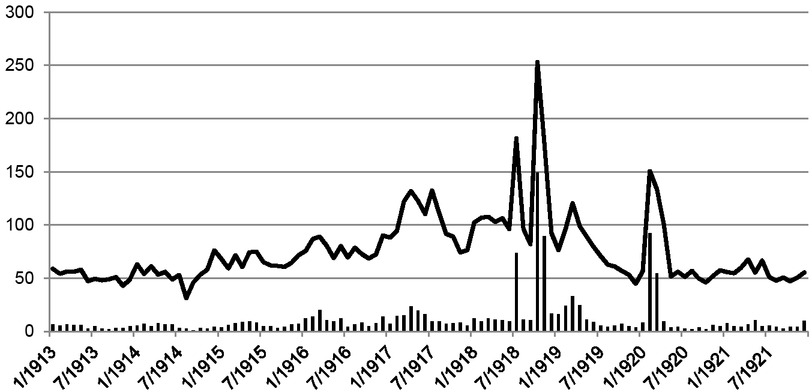

Figure 4 extends the picture beyond the miners’ morbidity experience by addressing monthly flu mortality rates. [35] The combined flu mortality rate amounted to 75 in July 1918, while in October it was 150 and 85 in November. In the spring of 1919, it was between 16 and 34 and between just over 50 and 90 in early 1920. While at the end of 1921 an upsurge in the infection rate beyond the long term usual occurred again, the mortality rate stayed within the limits set by pre-Spanish flu experience.

Monthly Mortality Rate among AKV members (Jan. 1913 to Dec. 1921). Note: The mortality rate shows crude deaths per 100,000 insured miners. All-cause mortality is indicated by a line, and combined influenza and pneumonia mortality by bars. Source: Jopp, Spanische Grippe, p. 109.

Looking at the experience of the Ruhr miners, a concise periodization reveals four waves of the Spanish flu epidemic: A first wave occurred in the summer of 1918, a second followed in the autumn 1918, a third happened in the winter of 1918/1919, and a fourth wave took place in late winter 1920. This periodization seems to be in line with what the literature on Germany’s Spanish flu experience has put forward so far. [36] While the first wave is characterized by an exceptionally high incidence of infection, the second one stands out for high mortality. In contrast, the third wave is already much less spectacular, while the fourth shows the highest lethality. [37] With two to three of altogether four epidemic waves taking part in 1918, this year was the worst of the three pandemic years in terms of sheer numbers of infection and death.

3 An Estimate of GNP Lost in 1918

Let us begin by going through the estimation of GNP lost for 1918 based on workdays lost. Tables 2 and 3 show the key components of this estimation.

Estimate of Excess Health Insurance Costs due to the Spanish Flu.

| Variable | 1918 |

|---|---|

| A) Figures relating to the AKV | |

| (1) Historical number of sick cases | 108,320 |

| (2) Estimated number of sick days | 1,616,173 |

| (3) Estimated mean length of sickness in days = (2) / (1) | 15 |

| (4) Estimated number of excess sick cases | 94,263 |

| (5) Estimated number of excess sick days = (4) * (3) | 1,413,945 |

| (6) Historical average sick pay per sick day in marks, nominal | 3.2 |

| (7) Historical average miscellaneous costs per sick day in marks, nominal | 1.3 |

| (8) Estimated total excess health costs in marks, nominal = (5) * ((6) + (7)) | 6,362,753 |

| (9) Historical total health costs in marks, nominal | 43,276,756 |

| (10) Share of excess health costs in total costs in percent = (8) / (9) * 100 | 14.7 |

| B) Figures relating to the entire health insurance system | |

| (11) Historical total health costs in marks, nominal | 901,945,000 |

| (12) Estimated total excess health costs, nominal = (11) * (10) / 100 | 132,585,915 |

| (13) Historical GNP at 1913 market prices in million marks, real (1913 = 1) | 43,502 |

| (14) Estimated total health costs in marks, real (1913 = 1) | 290,967,457 |

| (15) Estimated total health costs in percent of GNP = (14) / (13) * 100 | 0.67 |

| (16) Estimated total excess health costs in marks, real (1913 = 1) | 42,772,216 |

| (17) Estimated total excess health costs in percent of GNP = (16) / (13) * 100 | 0.10 |

Note: The focus is exclusively on flu reporting here, i.e., pneumonia and other potentially related diseases are excluded from consideration. Source: Author’s own computations.

Estimate of GNP Lost due to Influenza-related Sick Leave.

| Variable | 1918 |

|---|---|

| A) Figures relating to the AKV | |

| (1) Estimated number of excess sick days | 1,413,945 |

| (2) Historical membership size | 365,304 |

| (3) Estimated excess sick days per member = (1) / (2) | 3.9 |

| (4) Historical average nominal sick pay per sick day in marks, nominal | 3.2 |

| B) Figures relating to the entire working population | |

| (5) Historical working population | 27,000,000 |

| (6) Total person-days of work lost = (5) * (3) | 105,300,000 |

| (7) Estimated wage sum lost, nominal = 2 * (4) * (6) | 673,920,000 |

| (8) Historical GNP at 1913 market prices in million marks, real (1913 = 1) | 43,502 |

| (9) Estimated wage sum lost, real (1913 = 1) | 217,406,592 |

| (10) Estimated wage sum lost in percent of GNP = (9) / (8) * 100 | 0.50 |

| (11) Historical growth rate of GNP from t-1 to t in percent | -2.67 |

Source: Author’s own computations

In a first step, excess health costs are estimated. They are the costs that the AKV incurred due to the Spanish flu in the short term (see Panel A in Table 2); the definition of what constitutes sickness here directly follows from the health insurance system’s definition. A member was sick when receiving sick pay, which had to be preceded by a doctor’s formal diagnosis. Once a health-insured individual was formally diagnosed as sick with the flu, the individual had to sustain a three-day waiting period before insurance benefits were disbursed, i.e. from the fourth day of sickness onward and for a maximum of 26 weeks; thereafter, a health-insured person would have been transferred to accident insurance or to invalidity and old-age insurance.

Health costs consisted of two major types of expenditure, namely, daily sick pay disbursed due to certified sickness, and expenditures for medical care, such as visits to the doctor, drugs, and hospital stays (including stays at a health spa). [38] Cause-specific variation in costs can only be inferred from the data for expenses on sick pay. While sick days by cause were not reported directly in the statistics, sick cases were (see component 1 in Table 2, Panel A). Additional figures allow the calculation of the cause-specific mean duration of sickness (i.e. the average number of paid sick days per case).

Altogether, slightly over 108,000 flu cases were recorded in 1918 (see Figure 3). [39] Multiplied with the mean duration of a flu case of 15 days (component 2 in Table 2), [40] an estimate of over 1.6 million sick days (component 3) can be linked with the flu, which is 22.7 percent of the total number of sick days across all causes. Since a baseline number of flu infections in 1918 occurred anyway, excess sick cases (component 4) were estimated to be roughly 94,300 by subtracting the mean number of monthly cases for January to June 1918 from the number of cases for each month (see Figure 1). The number of excess sick days induced by the Spanish flu (component 5) then amounts to slightly over 1.4 million. The average sick pay per sick day for a miner can be calculated at 3.20 marks (component 6). By law, sick pay was supposed to amount to half the daily wage of an insured person.

In combination with average miscellaneous health benefits – i.e., all care-related benefits (component 7) – derived by assuming cost proportionality, [41] total excess health costs associated with excess sick days (component 8) can be calculated to have amounted to around 6.4 million marks. Considering the AKV’s reported health costs (component 9) of approximately 43.3 million marks, the share of flu-induced excess health costs (component 10) amounted to nearly 15 percent. This estimate of roughly 15 percent is the best estimate currently at hand of the share of flu-induced short term excess costs in the entire health insurance system.

Now, considering all types of sickness funds mentioned in Table 1 (component 11 in Table 2, Panel B), the German health insurance system can be assumed to have incurred excess costs of around 132.6 million marks for the Spanish flu (component 12). Adjusted for inflation (component 14) and expressed as a share of real GNP (component 13), this equals a share of almost 0.7 percent, which implies that the health insurance system in Germany at the end of the First World War was still not very sizeable. [42] This share is not solely explained by the fact that only half of the working population was health-insured. In addition, it must be considered that the system still offered rather low generosity levels compared to later periods. [43] Consequently, the 43 million marks spent in excess would come to around 0.1 percent of GNP. [44] This very low percentage could certainly be increased by taking into account estimates of health-related excess costs incurred outside the health insurance system.

The epidemiological experience of the AKV’s members, when expressed in reported health costs and demographic data, is now extrapolated to the national level, that is, to the entire German working population. This assumes that infection had similar statistical effects on both the insured and uninsured working population. [45] The proposed estimate of flu-induced excess sick days (component 1 in Table 3) serves as a starting point. Redistributing these days over the AKV’s entire membership (component 2), each member experienced, on average, four sick days due to the Spanish flu (3). Such a redistribution is necessary because there is no information available on flu-related sick cases in the remaining health insurance system or the non-insured population.

For the next estimation steps, only expenditures on sick pay are taken into account. Expenditures on miscellaneous health costs are excluded because they cannot be assessed by cause. Given the working population (component 5), the total person-days of work lost (component 6) amount to slightly more than 105 million. [46] Assuming that twice the daily sick pay for miners approximates the daily wage of the representative working person reasonably well, the estimated wage sum lost (component 7), associated with the loss in work time, amounts to 674 million marks. [47] From a distributional perspective, national output is essentially the sum of all factor incomes generated within a country’s borders. Hence, the sum of wages lost directly equals a production loss of the same amount. [48] Expressed in real terms (components 8 and 9), this production loss is in the range of 0.5 percent of GNP (component 10). When setting the ratio of labor to capital income to one – for the sake of the argument – the total production loss equals one percent in our estimation, or almost one-third of the total 1918 drop in GNP, which amounted to 2.67 percent. [49]

4 Discussion

How reliable is the presented estimate for GNP lost in 1918? There are several aspects that potentially affect the method of extrapolation and, consequently, the estimate’s quality.

To begin with, one might be inclined to surmise that the working conditions for coal miners underground – maybe less so at the surface – provided a perfect breeding ground for a highly infectious disease to spread faster than it would in other work environments. Miners worked in a confined space, with no option to avoid frequent contact with fellow workers. Apart from that, in many Ruhr mines, regular miners had to work side-by-side with prisoners-of-war (POWs) who were usually accommodated in overcrowded lodgings, which probably fostered the spread of disease among POWs and, consequently, among regular miners. [50] So, the question arises whether miners basically faced a higher risk of infection than the average employee. Since this aspect has not yet been studied, a definitive answer is hard to give.

The estimates of the fraction of the German population that got infected are in the range of 20 to 30 percent or more. [51] The figure for the Ruhr miners lies well within this range. Consider that the AKV had around 367,000 members in 1918 who produced roughly 86,700 sick cases related to the flu in the months July to December. [52] Under the restrictive assumption that each case represents a different miner, a fraction of 23.6 percent of the AKV’s members got infected. Allowing for multiple infections, and for a certain turnover among miners (which would raise the actual number of individual miners in the AKV’s membership above 367,000), the fraction was probably even smaller. Thus, the presumption of a systematically higher risk of infection among miners is not backed by the findings here. Probably, the proposed estimate likely somewhat underestimates the true occurrence of infection.

Directly related to this aspect, one may doubt whether the presented figures on the flu-induced mean excess sick days (i.e., 3.9 days per active AKV member) is an accurate description of the infection events in the health-insured working population, not to mention in the uninsured population. We would principally need to know whether miners systematically experienced fewer or more sick days compared to members of other sickness funds. Since all sickness funds were bound by the same legal framework, there is not much room to argue for systematic structural differences in the administrative process (which does not rule out discretion in individual cases). Such differences – rooted in structure or the quality of the provided health services – have not yet been researched in sufficient detail to draw firm conclusions; any attempt to do so has to overcome the problem of insufficient data because the Reich statistics and relevant semiofficial statistics do not offer comparable information on the health insurance system. Thus, applying the proposed estimate on the duration of sickness to higher levels of aggregation of the working population appears to be the only feasible option.

Regarding the uninsured employees, the crucial question is whether they disproportionately avoided seeing a doctor at their own expense when feeling sick, or, more importantly, whether they disproportionately went to work when sick (also called presenteeism), due to the monetary work incentive (i.e. absence of sick pay). Were these effects strong enough to systematically decrease the number of workdays lost in this group? Such practices would possibly have led to adverse effects on productivity, [53] and biological factors may have forced workers into a relapse, which would possibly have prolonged sickness. [54]

The fundamental problem here is that we know too little about the morbidity of non-health-insured individuals to weigh these factors accurately. Intuitively, a good starting point appears to be the literature on the epidemiological transition in Germany. However, where that literature looks at developments in the entire population, it focuses on mortality as the statistically far better documented aspect (probably assessed bottom-up from the city-level). Where morbidity is addressed, sources relating to the health insurance system are necessarily invoked. [55]

What about the monetary assumptions underlying the estimate? One might claim that the average sick pay in the health insurance system must have been lower than 3.2 marks. After all, miners’ wages exceeded the mean earnings in the working population as well as among industrial workers. [56] Yet, when projecting annual earnings from miners’ sick pay, assuming a work week of six days, one arrives at a figure slightly below that for the representative working person, which makes the estimate acceptable, after all. This assessment is somewhat supported by the observation that the average contributing member of the Berlin sickness fund mentioned above had to pay 37 marks for sickness benefits, while the average contributing AKV member had to pay only about 28 marks. [57] That means that the estimate here would be too low rather than too high. [58]

A final doubt about the plausibility of the estimate relates to overtime. The labor market was unable to supply additional workers in the short term because it was effectively drained after four years of war by mid-1918. [59] Possibly, a certain fraction of the workdays lost were compensated for by increasing working hours and, consequently, the workload of the healthy employees, with possible adverse health effects kicking in with a delay in 1919 or later. I have studied this effect previously, based on output and worktime data for Ruhr coal mining, and I assume that mine owners seemed to have managed to keep the level of production largely unchanged during late summer and even into October 1918 by reallocating working hours from sick to healthy employees. [60] However, Ruhr coal output declined by three million tons from 1917 to 1918, and this decline can almost entirely be attributed to November and December 1918, when official working hours were reduced. [61] Four mutually non-exclusive explanations for this decline come to mind: Firstly, the reduction in working hours reflects the mine owners’ tendency to reduce production capacity in light of economic uncertainty following the armistice on 11. November. Secondly, working hours may have been lost to strike activity; although mild post-war strike activity in late 1918 is documented, the main part of it occurred in the spring of 1919. [62] Thirdly, the release of some 70,000 POWs deployed in Ruhr coal mining may have triggered at least part of the decline. [63] Fourthly, excess workdays lost due to Spanish flu infections may have finally taken their toll on the Ruhr coal district’s output. Considering that one foregone workday per miner equalled one foregone shift, we can calculate foregone coal output by multiplying our estimates of excess workdays lost, reported in Tables 2 and 3, with average shift productivity of 1.02 tons. [64] As a result, almost 1.5 million tons of coal may be assumed foregone. This figure equals 1.5 percent of actual 1918 coal output, or roughly 50 percent of the decline. Viewed benevolently, this calculation lends some credence to the extrapolations with respect to GNP. [65]

5 Conclusion

In this paper, the German GNP loss caused by the Spanish flu in the year 1918 is estimated by drawing on the statistics of the Allgemeiner Knappschaftsverein Bochum, the second-largest German sickness fund at the time. Although the AKV’s membership is rather specific, the statistical results derived from this group can serve as a starting point for generalizing about the epidemiological experience in the entire working population – especially when it comes to the aspect of morbidity. The proposed estimate – a GNP loss of one percent, or nearly one third of the total GNP decline between 1917 and 1918 – should be considered a lower bound for the short term economic impact of the Spanish flu in Germany.

Additional factors beyond work absence due to sickness might be considered to refine this estimate and bring it even closer to the pandemic’s actual economic impact. Flu-related mortality, as was studied by Robert Barro et al., is one crucial factor because deaths certainly impacted the quantity and quality of the labor supply – in the short term as well as in the long term. [66] Non-pharmaceutical interventions causing, for example, additional losses in working or schooling hours should be factored in on the cost side as well. [67] However, the more complex any cost calculation gets, the greater the need for a thorough, integrative treatment of war costs, in general, and the pandemic’s cost, in particular. [68]

As it stands, the estimate derived in this paper provides an initial sense of the pandemic’s immediate economic severity in 1918 Germany, a country in wartime isolation. Thus, the case also illustrates how a pandemic affects a large, developed economy when globalization effects are temporarily not at work.

About the author

Tobias A. Jopp is a researcher at Technische Universität Bergakademie Freiberg. He studied economics at Universität Münster and completed his PhD in economics at Universität Hohenheim in 2012 with a study entitled Insurance, Fund Size, and Concentration: Prussian Miners’ Knappschaften in the Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Centuries and Their Quest for Optimal Scale (Berlin 2013). He held a number of academic positions in the Department of History at Universität Regensburg (2011–2024), where he completed his habilitation thesis in 2019 (T.A. Jopp, War, Bond Prices, and Public Opinion: How Did the Amsterdam Bond Market Perceive the Belligerents’ War Effort During World War One, Tübingen 2021). He held temporary positions in the departments of economics at Universität Hohenheim (2013/2014) and Universität Mannheim (2021/2022) before he joined the Institut für Wirtschafts- und Technikgeschichte (IWTG) in Freiberg in October 2024. His publications address the history of social insurance, quantitative mining history, financial history, aviation history, and the history and methods of historiography. Most recently he wrote: T.A. Jopp/M. Spoerer, Civil Aircraft Procurement and Colonial Ties: Evidence on the Market for Jetliners, 1952–1989, in: Journal of Transport History 45/3, 2024, pp. 492-521.

© 2025 Tobias A. Jopp, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Obituary for Eckart Schremmer

- Special Issue Articles

- Epidemics and Pandemics in Economic-historical Perspective – An Introduction

- Cholera in the City of Poznań: Did the Death Toll of the 1866 Cholera Epidemic Reflect Social and Economic Differences?

- The Mortality Impact of Cholera in Germany

- When Diseases Return from the Epidemiological Honeymoon: The Reemergence of Smallpox in 19th Century Germany and its Lessons for Public Health Policies after COVID-19

- On the Economic Costs of the Spanish Flu Pandemic in Germany: An attempt at Assessing GNP Lost for 1918

- Malaria in Catania/Sicily: Local Manifestations and International Scientific Cooperation During a Pandemic in the 1920s

- Geographical Aspects of Diphtheria in England and Wales: Immunisation and the Spatial Sequence of Retreat to Effective Elimination, 1921 to 1964

- Pandonomics: Why Economics was Unprepared for COVID-19-Policies

- Research Forum

- “Stupid” German Money? Bonus Interest Rate Payments on Savings Deposits During the Stagflation of 1967 to 1984

- Geography and Space in Recent Economic History

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Obituary for Eckart Schremmer

- Special Issue Articles

- Epidemics and Pandemics in Economic-historical Perspective – An Introduction

- Cholera in the City of Poznań: Did the Death Toll of the 1866 Cholera Epidemic Reflect Social and Economic Differences?

- The Mortality Impact of Cholera in Germany

- When Diseases Return from the Epidemiological Honeymoon: The Reemergence of Smallpox in 19th Century Germany and its Lessons for Public Health Policies after COVID-19

- On the Economic Costs of the Spanish Flu Pandemic in Germany: An attempt at Assessing GNP Lost for 1918

- Malaria in Catania/Sicily: Local Manifestations and International Scientific Cooperation During a Pandemic in the 1920s

- Geographical Aspects of Diphtheria in England and Wales: Immunisation and the Spatial Sequence of Retreat to Effective Elimination, 1921 to 1964

- Pandonomics: Why Economics was Unprepared for COVID-19-Policies

- Research Forum

- “Stupid” German Money? Bonus Interest Rate Payments on Savings Deposits During the Stagflation of 1967 to 1984

- Geography and Space in Recent Economic History