Epidemics and Pandemics in Economic-historical Perspective – An Introduction

-

Tobias A. Jopp

Tobias A. Jopp is a researcher at Technische Universität Bergakademie Freiberg. He studied economics at Universität Münster and completed his PhD in economics at Universität Hohenheim in 2012 with a study entitledInsurance, Fund Size, and Concentration: Prussian Miners’ Knappschaften in the Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Centuries and Their Quest for Optimal Scale (Berlin 2013). He held a number of academic positions in the Department of History at Universität Regensburg (2011-2024), where he completed his habilitation thesis in 2019 (T.A. Jopp , War, Bond Prices, and Public Opinion: How Did the Amsterdam Bond Market Perceive the Belligerents’ War Effort During World War One, Tübingen 2021). He held temporary positions in the departments of economics at Universität Hohenheim (2013/2014) and Universität Mannheim (2021/2022) before he joined theInstitut für Wirtschafts- und Technikgeschichte (IWTG) in Freiberg in October 2024. His publications address the history of social insurance, quantitative mining history, financial history, aviation history, and the history and methods of historiography. Most recently he wrote:T.A. Jopp/M. Spoerer , Civil Aircraft Procurement and Colonial Ties: Evidence on the Market for Jetliners, 1952–1989, in: Journal of Transport History 45/3, 2024, pp. 492-521.and Markus Lampe

Markus Lampe is Professor of Economic and Social History at Vienna University of Economics and Business (WU). His research focuses on agricultural development, globalization and trade policy in history. He is co-author ofM. Lampe/P. Sharp , A Land of Milk and Butter, Chicago 2019 andM. Lampe/K.G. Persson/P. Sharp , An Economic History of Europe: Knowledge, Institutions and Welfare, Prehistory to the Present, Cambridge 32025. He is also a visiting professor at the University of Gothenburg and a CEPR, CEPH and Figuerola Institute research fellow.

Abstract

Epidemics and pandemics have been a constant feature of human life across all regions and historical periods. They have led to individual suffering, brought on far-reaching societal challenges and shaped demographic trends. Their effects persist far into the future and are not fully understood yet. One area that still merits further research concerns the economic costs attached to pandemics in the short, medium, and long term. The articles assembled in this thematic special issue include a wide range of case studies across different time periods, geographic contexts, and types of pathogens. Collectively, they contribute to our historical understanding of the socioeconomic backgrounds of epidemics and pandemics, societal responses to them, and their impact on key areas of social life. This special issue reflects the inherently interdisciplinary nature of economic and social history which serves as a bridge between historical scholarship and the social sciences, particularly economics. This introduction focuses on distilling key insights from the growing body of literature on the economic costs of epidemics and pandemics. Our aim is to identify the lessons that history has clearly taught us about economic costs so far, while also drawing attention to those areas of knowledge that remain only partially understood and deserve future research.

Outbreaks of infectious diseases – whether endemic, re-emerging, or newly emerging – that spread far beyond their place of origin (epidemics) or even globally across continents (pandemics) have been recorded, though not always fully understood, by humankind for centuries. [1] Many epidemic diseases are transmitted through the air or direct contact, such as smallpox, measles, diphtheria, influenza, and COVID-19. Others depend on animal vectors, for example malaria (mosquitoes), the Black Death (fleas), and typhus (lice), while some are spread through contaminated water (cholera), or via human blood and other bodily fluids (HIV). This diversity of transmission routes involves a wide range of parameters, control measures, and outcomes that are of particular interest to scholars studying the dynamics of infectious diseases.

The frequency of these and other infectious diseases has varied over time, across regions, and among different social groups. For example, the bubonic plague repeatedly struck Europe – first as the Plague of Justinian in the sixth century AD and later in successive waves from the mid-fourteenth century until the 1720s. Yet it also devastated regions beyond Europe, including India and China, which endured a prolonged wave beginning in Yunnan in 1855 that lasted for nearly a century. Smallpox, likely the cause of the Antonine Plague in the second century AD, remained a major killer in Europe well into the 19th century. Together with typhus, measles, influenza, and other diseases, it contributed to the catastrophic population decline of indigenous peoples in the Americas after 1492, when the Columbian exchange introduced syphilis to Europe and Asia, while spreading European diseases across the Americas. [2] In the 19th and 20th centuries – this special issue’s primary chronological focus – cholera, diphtheria, smallpox, typhus, and influenza were among the most significant infectious diseases in Europe, albeit with varying timing. This period also saw the gradual disappearance of malaria in Europe, even as it continued to severely affect sub-Saharan Africa. [3] Meanwhile, the emergence and subsequent control of HIV marked a new chapter in epidemiology, with its death toll and social impact remaining deeply unequal across populations and social groups. [4]

The list presented in Table 1 offers a more systematic review of the deadliest epidemics and pandemics in human history. [5] It includes specific outbreaks that can be clearly situated in time – such as the influenza pandemic of 1918 to 1920 (better known as the Spanish flu) – as well as long-term pathogenic threats like smallpox, which persisted with devasting effects until the late 20th century. Taken together, repeated waves of smallpox, the bubonic plague, and various influenza and SARS viruses are estimated to have caused at least 500 million to one billion deaths. This figure is likely a conservative estimate, given the limitations of both historical and contemporary records related to population dynamics. [6] As illustrated in Table 2, uncertainties surrounding source material also constrain our ability to estimate infection numbers by time and region across different pathogens.

The Deadliest Epidemics and Pandemics in Human History

| Pandemic | Period | Geographical focus | Estimated death toll | Cause |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smallpox | Various periods | Worldwide | ~300-500 million in the later 19th and the 20th century alone | Variola virus |

| Black Death | 1347-1351 | Europe, Asia, North Africa | ~75-200 million | Yersinia pestis bacteria |

| Spanish Flu | 1918-1920 | Worldwide | ~50-100 million | H1N1 influenza virus |

| HIV/AIDS | 1981-present | Worldwide (but especially sub-Saharan Africa) | ~40+ million | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| Plague of Justinian | 541-542 CE (recurrences until 750 CE) | Byzantine Empire, Mediterranean | ~30-50 million | Yersinia pestis bacteria |

| Third Plague Pandemic | 1855-1959 | Worldwide (but mainly China, India) | ~12-15 million | Yersinia pestis bacteria |

| COVID-19 | 2019-present | Worldwide | ~7 million | SARS-CoV-2 virus |

| Cocoliztli Epidemics | 1545-1576 | Mexico, Central America | ~5-15 million | Unknown (possibly viral hemorrhagic fever) |

| Antonine Plague | 165-180 CE | Roman Empire | ~5-10 million | Possibly smallpox or measles |

| Hong Kong Flu | 1968-1970 | Worldwide | ~1-4 million | H3N2 influenza virus |

| Asian Flu | 1957-1958 | Worldwide | ~1-4 million | H2N2 influenza virus |

| Third Cholera Pandemic | 1852-1860 | Asia, Europe, North America | ~1-2 million | Vibrio cholerae bacteria |

| Russian Flu | 1889-1890 | Worldwide | ~1 million | H3N8 or H2N2 influenza virus |

Notes: ChatGPT was used to create Table land 2. It responded to three separately executed prompts: (1) “Create a list of the deadliest pandemics in human history”; (2) “Create a list of the deadliest epidemics in history”; and (3) “Create a list of the deadliest epidemics and pandemics in history”. All three lists are merged here. Smallpox is only listed in response to prompt (3). Entries were manually sorted according to the estimated death toll (ChatGPT's original sorting in the two lists slightly varied from ours, for an unclear reason). Formulating the prompts in German led to slightly different lists. Sources: ChatGPT (12.07.2025).

Table 2 was compiled using the same methodology as Table 1 and identifies outbreaks that may have produced the highest number of infections in recorded history. Notably, all listed events occurred within the past 175 years. This may be attributed to the vastly larger population in the modern era. However, it also reflects the profound lack of data on how pre-modern epidemic and pandemic events affected morbidity. [7]

The (Probably) Most Infectious Epidemics and Pandemics in Human History.

| Pandemic | Period | Geographical focus | Estimated infections | Cause |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swine Flu | 2009-2010 | Worldwide | ~1.4-1.6 billion | H1N1 influenza virus |

| COVID-19 | 2019-present | Worldwide | ~770+ million | SARS-CoV-2 virus |

| Spanish Flu | 1918-1920 | Worldwide | ~500-700 million | H1N1 influenza virus |

| Hong Kong Flu | 1968-1970 | Worldwide | ~100-200 million | H3N2 influenza virus |

| Asian Flu | 1957-1958 | Worldwide | ~100-200 million | H2N2 influenza virus |

| Russian Flu | 1889-1890 | Worldwide | ~300-500 million | H3N8 or H2N2 influenza virus |

| HIV/AIDS | 1981-present | Worldwide (but especially sub-Saharan Africa) | ~85+ million | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| Third Cholera Pandemic | 1852-1860 | Asia, Europe, North America | ~tens of millions | Vibrio cholerae bacteria |

| Chikungunya Outbreaks | 2005-present | Africa, Southeast Asia, India | ~tens of millions | Chikungunya virus |

| Zika Virus Outbreaks | 2015-2016 | Latin America (especially Brazil) | ~0.5-1+ million | Zika virus |

Note: ChatGPT responded to the prompt: (1) “Create a list of the epidemics and pandemics in human history with the highest infection rates”. What ChatGPT listed as Seasonal influenza was not included here. Likewise, not included are those epidemics and pandemics that lack an estimate of the infections in the provided list (i.e., measles, smallpox). Note the absence of malaria. Sources: ChatGPT (12.07.2025).

Epidemics and pandemics have been a constant feature of human life across all regions and historical periods. They have not only been responsible for extreme human suffering, but they have also shaped demographic trends and led to far-reaching societal challenges – effects that will likely persist into the future. For evidence supporting the historical dimension of this claim, we refer readers to the extensive existing literature documenting the occurrence and demographic consequences of past epidemics and pandemics. [8] There is no need to repeat in more detail what has already been thoroughly established. This introduction instead focuses on distilling key insights from the growing body of literature on the economic costs of epidemics and pandemics.

It is entirely understandable that scholars primarily concerned with epidemiological, medical, and demographic questions about epidemics and pandemics focus on compiling and interpretating data on disease transmission – both in its biological dimension and in its broader dependence on social and cultural practices – along with incidence, prevalence, lethality, and overall mortality. Such efforts are essential for understanding epidemics and pandemics, as well as for formulating effective action plans and policy. However, both individuals and societies inevitably bear short-, medium-, and long-term economic costs associated with epidemics and pandemics. These arise not only from unmanaged or poorly managed outbreaks, but also from the very efforts to study, understand, and control them – or, conversely, from the absence of such efforts. For this reason, this special issue seeks – albeit in general terms – to highlight the economic cost dimension of past epidemic and pandemic events, a topic firmly within the scope of economic history.

Our aim in this introduction is to identify the lessons that history has taught us about economic costs, while also drawing attention to those areas of knowledge that remain only partially understood and deserve future research. In doing so, we do not claim – nor could we reasonably hope – to provide a comprehensive survey of all relevant literature on the subject. [9] Instead, we focus on summarizing the most recent research efforts since 2020.

1 COVID-19 and the Reviving Interest in the Economics of Pandemics

There is little doubt that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound and multifaceted impact on modern economies and societies. Warwick McKibbin and Roshen Fernando, for instance, estimate the global loss in gross domestic product (GDP) for the year 2020 alone at approximately 17 trillion US dollars – an indicator of the pandemic’s immediate economic repercussions. [10] Trying to improve on the quantification of the pandemic’s short- and long-term macroeconomic effects and to understand the underlying mechanisms of the associated cost – particularly in relation to the pre-crisis degree of globalization and the societal responses via pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical interventions – has reinvigorated scholarly interest in the study of epidemics and pandemics across a wide array of disciplines, which is not confined to economics and economic history but includes epidemiology, public health, political science, and beyond. [11]

Two principal factors are common to this multi-disciplinary revival: the paucity of reliable and comprehensive data, and a lack of consensus on appropriate methodologies for interpreting existing, ostensibly valid datasets. Considering the uncertainty regarding both COVID-19’s progression and its observable consequences, researchers have increasingly turned to historical analogies as a means of fostering theoretical insight and guiding policy formulation. Retrospective analyses extend beyond the immediate epidemiological concerns of disease transmission and mortality patterns. They include efforts to estimate the economic costs associated with the pandemic in the short, medium, and long term – costs incurred not only as a direct consequence of the viral outbreak itself, but also because of the broad spectrum of public health and social policy interventions implemented in response. [12]

To substantiate our claim of a broadly renewed scholarly interest in epidemics since 2020 – particularly in the use of historical analogies – we first draw on Google’s Ngram Viewer and conduct a simple topical analysis of economic history journals. The Ngram Viewer tool enables systematic searches across various Google Books corpora using simple lexical queries and provides visual representations of relative term frequencies over time. [13]

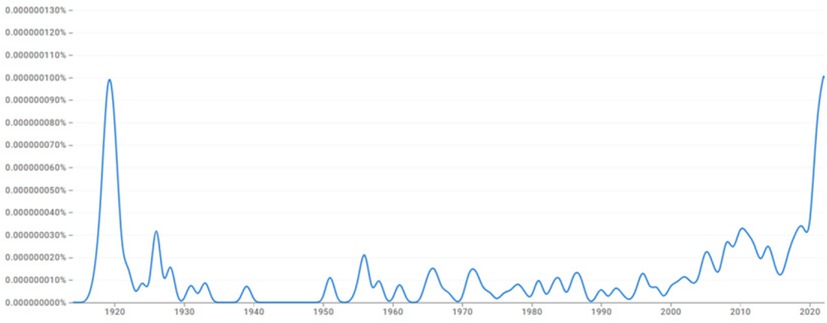

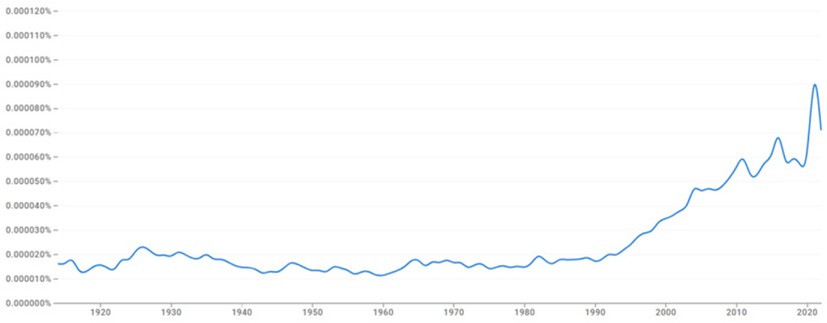

Figures 1 and 2 present the results for Spanish Flu and Black Death. In addition to their epidemiological significance in terms of mortality and morbidity (see Tables 1 and 2), these historical pandemics offer the analytical advantage of being clearly associated with specific historical periods, which facilitates the interpretation of trends. By a considerable margin, these two pandemics remain the most frequently invoked historical examples for drawing inferences about present health challenges.

The Spanish Flu in the English-language Google Books Corpus, 1914 to 2022. Note: Depicted is the combined frequency of the 2-grams Spanish Flu and Spanish Influenza (including all cases of lower-case notation) in all 2-grams. Sources: https://books.google.com/ngrams/ (16.07.2025).

The Black Death in the English-language Google Books Corpus, 1914 to 2022. Note: Depicted is the frequency of the 2-grams Black Death (including all cases of lower-case and mixed lower-/upper-case notation) in all 2-grams. Sources: https://books.google.com/ngrams/ (16.07.2025).

Figure 1 indicates a steady increase in references to the Spanish flu between 2000 and 2010, followed by a larger surge beginning in 2016. Then, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic appears to have triggered a substantial increase in publications through 2022, the most recent year currently available in the English-language Google Books corpus. In contrast, the trajectory for Black Death shown in Figure 2 is less pronounced. Nevertheless, a moderate upward trend in references after 2019 is observable, suggesting a pandemic-related stimulus as well. It is important to note that Figures 1 and 2 do not provide information on the disciplinary distribution or genre of the publications included. However, this preliminary analysis lends empirical support to our more general argument regarding the resurgence of interest in pandemic history and analogical reasoning.

This general analysis will now be complemented by a targeted investigation of epidemic and pandemic research in economic history over the period 2000 to 2025. For this purpose, the five leading economic history journals were systematically reviewed for articles that examine a specific outbreak or series of outbreaks caused by the same pathogen, or that adopt a global, comparative perspective on the subject. [14] Table 3 shows the results of our screening efforts, pooled in five-year intervals. Panel A shows the total number of articles published in these journals, the number of articles deemed relevant under our definition, and the proportion of these articles measured as a share of all published articles. Panel B informs on the proportion by journal.

Proportion of Articles on Epidemics and Pandemics in the Top Five Economic History Journals, 2000 to 2025.

| Measure | 2000–2004 | 2005–2009 | 2010–2014 | 2015–2019 | 2020–2024 | 2025– |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. All five journals taken together | ||||||

| Published articles in total | 436 | 543 | 714 | 699 | 765 | 115 |

| Articles on a specific epidemic or pandemic, or with a comparative focus on several epidemics or pandemics | 4 | 5 | 9 | 15 | 24 | 4 |

| Relevant articles in percent of all articles | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 3.1 | 3.5 |

| B. Proportion by journal Cliometrica | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 3.2 | 7.1 | |

| Economic History Review | 2.6 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 3.1 |

| European Review of Economic History | 0.0 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 2.2 | 0.0 |

| Explorations in Economic History | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 2.3 | 4.0 | 4.5 |

| Journal of Economic History | 0.6 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 0.0 |

Note: Cut-off date for consideration of articles for 2025 is 13. July 2025. Published articles in total include research articles and short communications, but not review articles, errata, or editors’ notes. Percentages are rounded to one decimal place. Sources: Authors’ own calculations.

The volume of publications on epidemics and pandemics appears to be slightly increasing since the 2010s. [15] However, the increase in response to COVID-19 is less pronounced than that observed in Figure 1. One possible explanation for this moderate increase is that economic historians, who are working on this topic, are not just publishing in economic history journals, but in interdisciplinary outlets. [16] A comprehensive meta-analysis of economic historians’ publication patterns would be required to arrive at a more differentiated understanding of the field’s engagement with the topic. [17]

2 Historical Pandemics and their Economic Lessons in the Spotlight

One of the most influential early efforts in epidemiological modelling of non-pharmaceutical inventions and their potential impact on the spread of COVID-19 was a report published by Imperial College London, dated 16. March 2020. The report drew a direct analogy to the 1918 Spanish flu, caused by the H1N1 influenza virus. Its microsimulations were based on epidemiological insights from past influenza pandemics, including that of 1918. The authors concluded that “[…] the effectiveness of any one intervention in isolation is likely to be limited, requiring multiple interventions to be combined to have a substantial impact on transmission.” Given that no vaccine was available at the time, the report recommended efforts to “reverse epidemic growth” by suppressing transmission, which would “minimally require a combination of social distancing of the entire population, home isolation of cases and household quarantine of their family members,” alongside “school and university closures, […] [recognising] that such closures may have negative impacts on health systems due to increased absenteeism.” [18] The greater economic repercussions of the proposed measures, however, remained largely uncertain at this stage.

Early efforts to draw on historical analogies to anticipate such economic repercussions are closely associated with initiatives by the Center for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) in London. As early as 6 March 2020, CEPR published an e-book entitled Economics in the time of COVID-19, which was a collection of mostly short papers by economists attempting to project likely developments. The volume contained only two general references to the influenza pandemic of 1918, but no fewer than nine references to the Black Death, cited in two contributions by economic historians. [19]

A first more comprehensive attempt at anticipating the economic cost appeared in the inaugural article of the first issue of Covid Economics. Vetted and Real-Time Papers, CEPR’s ad hoc journal published between 3 April 2020 and 1 July 2021 with 83 issues. In this article, Sanjay Singh et al. estimated how the most significant pandemics since the 14th century had affected capital and labor markets. Their analysis showed that asset returns were significantly and negatively impacted, whereas real wages experienced modest positive effects. [20] Subsequent issues of Covid Economics featured more studies drawing on historical examples. Several papers examined the impact of the 1918 flu pandemic on the economies of American cities that had implemented non-pharmaceutical interventions to varying degrees. While Casper Hansen et al. focused on the short-term effects and Guillaume Chapelle on medium-term outcomes, Christopher Meissner and Zhixian Lin explored the long-run persistence of public health outcomes from 1918 to 2020. They found that cities more severely affected by the 1918 pandemic in terms of mortality were also hit disproportionately hard during the early phase of COVID-19. [21] Similarly, Tullio Jappelli and Mario Carillo estimated the short-term impact of the Spanish influenza on subsequent regional growth in Italy – a European country severely affected by the Spanish flu. They demonstrated a clear positive relationship between regional mortality levels and subsequent regional output losses. [22]

In 2007, CEPR had launched the online platform VoxEU columns as a forum for economists to comment on current economic and policy developments and to disseminate early-stage research in an accessible, low-threshold format. [23] In the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, the platform saw a surge in columns on pandemic economics, with many drawing on historical analogies to better grasp the potential economic costs. Viewed against the backdrop of the initial, deeply unsettling societal experiences with COVID-19, an analysis of these columns offers a quick way to identify the most pressing concerns voiced in economic history-related research at the time.

Table 4 lists all VoxEU columns tagged with economic history that appeared between March and December 2020. In addition to the date of publication, the headline, and contributors, each column was assigned by us to a broader subject category. As the compilation shows, in the early stages of the pandemic, economic historians, and economists invoking historical precedent, focused primarily on four themes: the effects on regional, national, and global output growth; the effects on social capital (shaped by social distancing and blame dynamics); the effects on private and public finance; and the implications for inequality. The Spanish influenza of 1918 and the Black Death emerge as the most frequently cited historical examples in this collection, reinforcing our earlier observation about the enduring significance of these pandemics for research.

Pandemics in VoxEU Columns Tagged with Economic History in 2020.

| Date | Headline | Authors | Broader subject |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20. March | Coping with disasters: Lessons from two centuries of international response | C. Reinhart, C. Trebesch, S. Horn | GDP |

| 20. March | Coronavirus meets the Great Influenza Pandemic | J. Ursua, J. Weng, R. Barro | GDP |

| 22. March | Pandemics and social capital: From the Spanish Flu of 1918/1919 to COVID-19 | M. Le Moglie, G. Alfani, F. Gandolfi, A. Aassve | Social capital/Non-pharmaceutical interventions |

| 04. April | Will inflation make a come-back after the crisis ends? | A. Scott, D. Miles | Monetary and fiscal policy |

| 04. April | The normality of extraordinary monetary reactions to huge real shocks | S. Ugolini | Monetary and fiscal policy |

| 08. April | The longer-run economic consequences of pandemics | S. Singh, A. Taylor, O. Jordà | GDP |

| 09. April | Pandemics and asymmetric shocks: Lessons from the history of plagues | G. Alfani | GDP |

| 10. April | Globalisation and financial contagion: A history | A. Szafarz, K. Oosterlinck, M. Briere, A. Burietz, O. Accominotti | Finance |

| 20. April | What we may learn from historical financial crises to understand and mitigate COVID-19 panic buying | K. Rieder | Individual household behaviour/Monetary and fiscal policy |

| 21. April | Coronavirus from the perspective of 17th century plague | M. Kelly, C. Ó Gráda, N. Cummins | Inequality |

| 29. April | The 1918 influenza did not kill the US economy | C. Frydman, E. Benmelech | GDP |

| 03. May | Pandemics and the persecution of minorities: Evidence from the Black Death | N. Johnson, M. Koyama, R. Jedwab | Social capital/persecutions |

| 05. May | COVID-19: The skewness of the shock | F. Guvenen, S. Salgado, N. Bloom | Sectoral output |

| 13. May | Modern health crisis: Recession and recovery | J. Rogers, S. Zhou, C. Ma | GDP |

| 20. May | Re-evaluating the benefits of non-pharmaceutical interventions during the 1918 pandemic | G. Chappelle | Social capital/Non-pharmaceutical interventions |

| 26. May | Trade and travel in the time of epidemics | H.-J. Voth | Social capital/Mobility |

| 14. July | Pandemics and local economic growth: Italy during the Great Influenza | T. Jappelli, M. Carillo | Regional output |

| 03. October | Pandemics and inequality | T. Giommoni, S. Galletta | Inequality |

| 15. October | Pandemics and inequality: A historical review | G. Alfani | Inequality |

| 11. November | Economic expected losses and downside risks due to the Spanish Flu | W. van der Veken, R. De Santis | GDP |

Sources: VoxEU, https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns (16.07.2025).

Let us take output growth, highlighted in Table 4, as an example. Economic historians have shown sustained interest in the effects of historical pandemics on output growth at different levels of economic activity – individual, sectoral, by country, and global. The latter two are typically assessed using datasets covering the period of the Spanish influenza pandemic. Robert Barro et al., for example, examine mortality and GDP across 48 countries and suggest that the representative country experienced GDP and consumption declines between six and eight percent, underscoring the importance of limiting, as far as possible, the death toll of a severe pandemic. [24] Using a more complex approach to analyzing historical GDP data, Maciej Stefanski finds that, overall, pandemics stimulate GDP per capita in the medium and longer-term, mainly due to mortality-related productivity effects. [25] Fraser Summerfield and Livio Di Matteo also take a long-term perspective on fluctuations in GDP, but with a specific focus on influenza pandemics between 1871 and 2016. Their findings suggest that those pandemics with milder effects on population dynamics, especially mortality, can nonetheless cause serious economic repercussions. [26]

Subnational repercussions on economic output have likewise been examined in a range of studies. François Velde, for instance, drawing on high-frequency city-level data, argues that the US economy was only moderately affected by the 1918 influenza pandemic, owing in part to the policy interventions aimed at containing the spread of the virus. [27] In addition, Gustavo Cortes and Gertjan Verdickt analyze the responses of the US life insurance industry, finding that life insurers raised premiums in line with increasing mortality risk. [28] Lars-Fredrik Andersson and Liselotte Eriksson, by contrast, investigate household-level behavioral responses to increased demographic and economic risk during the 1918 influenza pandemic in Sweden. Their findings indicate that, unlike in the US, Swedish life insurers did not experience more demand for life insurance policies, thereby raising the question why behavioral adaptation remained comparatively sluggish in the face of a severe health crisis. [29]

A different line of inquiry into the macroeconomics of pandemics is pursued by Vincent Geloso and Jamie Pavlik, who explore the relationship between pandemics and the degree of economic freedom. They argue that countries with greater economic freedom fared better in the 1918 pandemic in terms of output losses. This finding has been corroborated in various contexts: by Rosolino Candela and Vincent Geloso, using data on present-day economies; by Vincent Geloso et al., drawing on historical data on economies’ exposure to typhoid fever and smallpox; by Gregori Galofré-Vilà et al., who link the aftermath of the First World War and the Spanish flu to the rise of fascism in Italy and Germany; and by Nina Boberg-Fazlic et al. and Pierre Siklos, studying the Spanish influenza pandemic’s potential impact on the interwar reversal of globalization – namely, the resurgence of protectionism. [30]

A third important dimension of the macroeconomic costs potentially incurred by a pandemic concerns private finance, as was already hinted at by either increased or sluggish demand for life insurance. Building on the study by Sanjay Singh et al. mentioned earlier, who suggest that history reveals a negative relationship between asset returns and the severity of epidemics and pandemics, Richard Burdekin and Marco Del Angel et al. examine stock market responses to the 1918 influenza pandemic. [31] To the extent that stock market players’ perceptions on the war effort, on the one hand, and the pandemic’s demographic and economic shocks, on the other, can be disentangled, historical evidence suggests that European and US stock markets reacted strongly and negatively to the pandemic. This contrasts with the experience during COVID-19 in the present, when stock markets did not react very much. [32] One possible explanation is that in 1918, unlike in 2020, the working population was affected more severely, with negative implications for labor supply and, consequently, firm’s short- and medium-term profit expectations. [33]

Apart from macroeconomic repercussions, economic and social historians study epidemics and pandemics with regard to their impact on social structures and the distribution of demographic and economic burdens – as well as potential benefits – across different social groups over varying temporal horizons. Historical evidence consistently demonstrates that socioeconomic inequalities, albeit in differing forms and intensities, have characterized every society constructed by humankind and, when exacerbated beyond a critical threshold, have frequently precipitated social unrest. Guido Alfani, for example, has provided a valuable long-term perspective on the relationship between epidemics and economic inequality. In his analytical framework, epidemics are conceptualized as asymmetric shocks whose consequences varied markedly depending on a society’s institutional structures and social capabilities – particularly those embedded in networks of interpersonal and societal relations. [34] This means that inequality outcomes cannot be reasonably predicted solely on the basis of a pandemic’s demographic impact, especially mortality rates. [35] Earlier research by Nico Voigtländer and Hans-Joachim Voth, had shown that pre-modern pandemics sometimes produced relatively favorable long-term economic outcomes, including lower levels of inequality. As Voth explained in an interview with Spiegel Online in March 2020, the Black Death, despite its catastrophic death toll, catalyzed economic transformations that ultimately laid the groundwork for the emergence of industrialized society. [36] Many studies emphasize the longterm transformative impact of the Black Death on European societies, on the Great Divergence, and on the Little Divergence within Europe. [37] In this context, the Black Death emerges as an event that enabled some economies – primarily those of North-Western Europe – not only to escape Malthusian constraints in the short term, but also to initiate structural transformations. These potentially encompassed changes in land and labor market institutions, consumption habits, marriage patterns, and the spatial as well as sectoral distribution of production. These developments helped lock in the short-term gains and create favorable path dependency. By contrast, in other regions, existing institutional, social, and geographical conditions impeded such resilience and hindered comparable structural change. [38]

For the 19th and 20th centuries, several studies have examined the relationship between social class, geography, and excess mortality during the 1918 influenza pandemic for the cases of Sweden, Spain, the US, and other places and diseases. [39] This body of research suggests that, while the Black Death of the 1340s, which struck European societies largely unprepared, seems to have acted as a “great leveler”, to use Walter Scheidel’s term, subsequent waves of the plague and other pathogenic crises, although occasionally affecting rich and poor alike, were overall more likely to exacerbate than to reduce socioeconomic inequalities. [40] Richard Franke, for instance, in an attempt to corroborate Karen Clay et al.’s findings for the US in a German context, demonstrates a significant negative relationship between income and mortality during the Spanish influenza pandemic. [41]

The degree to which such distinctions between the modern and premodern eras hold true depends to a considerable extent on the configuration of the welfare state as well as on public health measures implemented – or, conversely, neglected – in response to severe health crises. Consequently, the role of epidemics and infectious diseases in shaping policy responses and social narratives has received sustained attention from social and cultural historians. Such policy responses have ranged from positively perceived interventions, such as the introduction of improved sewage systems – closely intertwined with the political economy of cholera [42] – and the establishment of disease control institutions, [43] to sometimes unpopular non-pharmaceutical interventions, including social distancing and quarantine or confinement. [44] Moreover, pandemics have frequently triggered mechanisms of distrust, blame, scapegoating, and xenophobia, exemplified in the stigmatization associated with HIV/AIDS and the attribution of infectious threats to foreign countries and migrant populations. [45] Both measures and discourses, shaped by authorities or those opposing them, can have strong and long-lasting – and perhaps unintended – consequences.

Finally, there is the question of whether epidemics also transmit adverse consequences across generations – through in utero exposure that impairs health status and economic outcomes of the affected cohorts over subsequent decades; this question remains highly contested the literature. While early seminal contributions by Douglas Almond and Bhashkar Mazumder argued for substantial in utero effects of the 1918 to 1920 influenza pandemic in the US, with variation according to the prenatal social environment, more recent reevaluations of the evidence by Brian Beach et al. have produced mixed and largely insignificant results. [46]

As far as Table 4 suggests, one area that appears to have received comparatively little immediate scholarly attention when COVID-19 emerged, concerns the effects of pandemics on human capital formation over different time horizons, and, by extension, their implications for long-term economic development. Pre-COVID-19 research highlights the relevance of such dynamics. For instance, Brian Beach et al. emphasize the critical role of improved water quality – reducing mortality from waterborne diseases such as typhoid fever (and cholera, of course) – in fostering human capital formation. [47] Similarly, Marco Percoco demonstrates for Italy that the 1918 influenza pandemic significantly reduced the average years of schooling among the 1918 to 1920 birth cohorts, with persistent negative effects on regional productivity well beyond the pandemic. [48] Complementing this evidence, Keith Meyers and Melissa Thomasson document comparable consequences of the 1916 polio outbreak in the US, while Amanda Guimbeau et al. provide analogous findings for Brazil. [49]

Another area that appears to be comparatively understudied from an economic historical perspective is pharmaceutical interventions like immunization, compared to non-pharmaceutical ones like social distancing and lock-down policies. Although, for example, Malte Thießen and Wilfried Witte provided evidence on the impact of vaccination campaigns for Germany, there is still much to learn about the economic costs attached to such campaigns in the past and present. [50]

3 What this Special Issue Offers

This special issue is not the first in recent years to adopt a historical perspective on pressing questions about epidemics and pandemics. Readers interested in related historical lessons may consult at least four other special issues:

– Geschichte und Gesellschaft published a special issue on COVID-19 in a historical and social science perspective as early as 2020 (Vol. 46, issue 3). [51]

– Historical Social Research followed up in 2021 with a special issue on Caring in times of a global pandemic/vaccination and society (Vol. 46, issue 4) and a supplement on Epidemics and pandemics – the historical perspective (Suppl. 33). [52]

– In 2022, The Economic History Review featured a symposium on demographic shocks (Vol. 5, issue 4), consisting of an introductory and three research articles, two of which address lessons from the Spanish flu and are referenced in this issue. [53]

– In addition, The Economic History Review hosts a virtual special issue on epidemics, disease and mortality on its homepage, assembling relevant articles from past volumes. [54]

While these special issues offer valuable insights into historical examples and highlight important lessons, they leave ample room for further investigations into various economic aspects of historical epidemics and pandemics.

The articles assembled in this thematic special issue include a wide range of case studies across different time periods, geographic contexts, and types of pathogens. Collectively, they contribute to our historical understanding of the socioeconomic backgrounds of epidemics and pandemics, of societal responses to them, and of their impact on key areas of social life. In doing so, this special issue reflects the inherently interdisciplinary nature of economic history which serves as a bridge between historical scholarship and the social sciences, particularly economics. However, this bridging function extends beyond these disciplines. Judging by the disciplinary background of the contributing authors, the volume is situated at the intersection of diverse academic fields, including history, economics, sociology, demography, geography, epidemiology, biology, and statistics.

Chronologically, the focus of the assembled articles lies entirely on epidemic and pandemic events in the modern era, defined here as outbreaks occurring since approximately 1800. The infectious diseases examined include cholera, diphtheria, malaria, smallpox, influenza, and COVID-19. Methodologically, the contributions span a broad spectrum, ranging from qualitative-hermeneutic analyses to quantitative, regression-based approaches.

Grażyna Liczbińska and Jörg Vögele, as well as Kalle Kappner, examine the history of cholera in 19th-century Germany. Kappner employs a novel comparative dataset at the city level to analyze macro-regional variation across successive cholera waves between 1831 and 1914. In contrast, Liczbińska and Vögele provide a micro-level case study of a specific outbreak in the fortified city of Poznań in 1866. Despite the city’s structurally conducive conditions for cholera transmission, they identify variation in exposure, infection, and mortality according to neighborhood, social status, and gender. Katharina Mühlhoff investigates the dynamics of smallpox in Germany, a disease largely in retreat due to the implementation of vaccination policies in the early 19th century. However, she highlights its unexpected resurgence during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/1871, when soldiers from various regions with differing immunization regimes came into close contact in garrisons and on the battlefield. The important lesson is that post-pandemic vaccine hesitancy can lead to problematic gaps in population immunity very quickly unless counteracted by resolute political action towards immunization. Tobias A. Jopp analyzes the 1918 influenza pandemic in Germany at its peak and estimates its immediate macroeconomic consequences, particularly national output loss, from a distributional perspective. Lene Faust and Christian Franke trace the activities of national and international experts in Catania, Sicily, which was once one of Europe’s most malaria-ridden areas. They reconstruct the political conflicts and the divergent expert views that shaped efforts to eliminate the disease. The contribution by Matthew Smallman-Raynor, Sarah Jewitt, and Andrew D. Cliff examines the successful eradication of diphtheria in England and Wales during the 1940s and 1950s. The authors emphasize the protracted struggle to implement comprehensive compulsory vaccination policies, which ultimately proved effective only after years of resistance and regional variation. Peter van Bergeijk reflects on pandemic policymaking under conditions of uncertainty. He argues that, outside of East Asia, economic preparedness for the COVID-19 pandemic was inadequate. This, he suggests, stemmed in part from fundamental differences in how economists and epidemiologists evaluated the feasibility of lockdowns and other non-pharmaceutical interventions, as well as diverging priorities in national emergency planning and risk assessment.

Together, these studies illustrate that the economic history of epidemics and pandemics remains a dynamic and methodologically diverse field. Unlike policymaking, which often prioritizes short-term, cost-effective solutions, historical analysis offers insights into areas where societal benefits unfold more gradually. It thus provides a valuable perspective on the long-term and often unpredictable interactions between diseases, national economies, and social structures.

About the authors

Tobias A. Jopp is a researcher at Technische Universität Bergakademie Freiberg. He studied economics at Universität Münster and completed his PhD in economics at Universität Hohenheim in 2012 with a study entitled Insurance, Fund Size, and Concentration: Prussian Miners’ Knappschaften in the Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Centuries and Their Quest for Optimal Scale (Berlin 2013). He held a number of academic positions in the Department of History at Universität Regensburg (2011-2024), where he completed his habilitation thesis in 2019 (T.A. Jopp, War, Bond Prices, and Public Opinion: How Did the Amsterdam Bond Market Perceive the Belligerents’ War Effort During World War One, Tübingen 2021). He held temporary positions in the departments of economics at Universität Hohenheim (2013/2014) and Universität Mannheim (2021/2022) before he joined the Institut für Wirtschafts- und Technikgeschichte (IWTG) in Freiberg in October 2024. His publications address the history of social insurance, quantitative mining history, financial history, aviation history, and the history and methods of historiography. Most recently he wrote: T.A. Jopp/M. Spoerer, Civil Aircraft Procurement and Colonial Ties: Evidence on the Market for Jetliners, 1952–1989, in: Journal of Transport History 45/3, 2024, pp. 492-521.

Markus Lampe is Professor of Economic and Social History at Vienna University of Economics and Business (WU). His research focuses on agricultural development, globalization and trade policy in history. He is co-author of M. Lampe/P. Sharp, A Land of Milk and Butter, Chicago 2019 and M. Lampe/K.G. Persson/P. Sharp, An Economic History of Europe: Knowledge, Institutions and Welfare, Prehistory to the Present, Cambridge 32025. He is also a visiting professor at the University of Gothenburg and a CEPR, CEPH and Figuerola Institute research fellow.

© 2025 Tobias A. Jopp/Markus Lampe, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Obituary for Eckart Schremmer

- Special Issue Articles

- Epidemics and Pandemics in Economic-historical Perspective – An Introduction

- Cholera in the City of Poznań: Did the Death Toll of the 1866 Cholera Epidemic Reflect Social and Economic Differences?

- The Mortality Impact of Cholera in Germany

- When Diseases Return from the Epidemiological Honeymoon: The Reemergence of Smallpox in 19th Century Germany and its Lessons for Public Health Policies after COVID-19

- On the Economic Costs of the Spanish Flu Pandemic in Germany: An attempt at Assessing GNP Lost for 1918

- Malaria in Catania/Sicily: Local Manifestations and International Scientific Cooperation During a Pandemic in the 1920s

- Geographical Aspects of Diphtheria in England and Wales: Immunisation and the Spatial Sequence of Retreat to Effective Elimination, 1921 to 1964

- Pandonomics: Why Economics was Unprepared for COVID-19-Policies

- Research Forum

- “Stupid” German Money? Bonus Interest Rate Payments on Savings Deposits During the Stagflation of 1967 to 1984

- Geography and Space in Recent Economic History

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Obituary for Eckart Schremmer

- Special Issue Articles

- Epidemics and Pandemics in Economic-historical Perspective – An Introduction

- Cholera in the City of Poznań: Did the Death Toll of the 1866 Cholera Epidemic Reflect Social and Economic Differences?

- The Mortality Impact of Cholera in Germany

- When Diseases Return from the Epidemiological Honeymoon: The Reemergence of Smallpox in 19th Century Germany and its Lessons for Public Health Policies after COVID-19

- On the Economic Costs of the Spanish Flu Pandemic in Germany: An attempt at Assessing GNP Lost for 1918

- Malaria in Catania/Sicily: Local Manifestations and International Scientific Cooperation During a Pandemic in the 1920s

- Geographical Aspects of Diphtheria in England and Wales: Immunisation and the Spatial Sequence of Retreat to Effective Elimination, 1921 to 1964

- Pandonomics: Why Economics was Unprepared for COVID-19-Policies

- Research Forum

- “Stupid” German Money? Bonus Interest Rate Payments on Savings Deposits During the Stagflation of 1967 to 1984

- Geography and Space in Recent Economic History