Pandonomics: Why Economics was Unprepared for COVID-19-Policies

-

Peter A. G. van Bergeijk

Peter van Bergeijk is emeritus professor at the Institute of Social Studies of Erasmus University, the Netherlands. He wrote extensively on the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, including the relationship between pandemics and (de)globalization. His most recent book is:P.A.G. van Bergeijk , On the Inaccuracies of Economic Observations: Why and How we could do Better, Cheltenham 2024. It contains a chapter on measurement errors during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Abstract

Despite clear warnings from scientists and a long history of pandemics, the economics profession was largely unprepared for COVID-19 and especially the drastic policy responses it triggered. While the risk of pandemics had been quantified – with estimated global annual costs of up to $500 billion – this knowledge was not integrated into mainstream economic thinking, modelling, or policy planning. Economists underestimated the sweeping public health interventions – particularly non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) like lock-downs, social distancing, and school closures, which were largely overlooked in economic literature. This gap was mirrored by institutions like the IMF, World Bank, and OECD, which had flagged pandemic risks but did not incorporate them into core forecasting frameworks. Academic economics also fell short, with limited pandemic-related research and little cross-disciplinary collaboration with health sciences. Several factors contributed to this underinvestment in preparedness: complacency from decades of global stability, distorted risk perception (e.g., viewing pandemics as issues for developing countries), and the invisibility of successful prevention. Pandemic preparedness, as a global public good, suffers from collective action problems: everyone benefits, but few want to pay. The COVID-19 crisis revealed a major blind spot in economic thinking: the failure to anticipate and model the economic implications of large-scale health policies. Going forward, stronger integration between economics and epidemiology is essential. Policymakers must also remain cautious in assessing the full cost of the pandemic, as data continues to be revised. This experience calls for humility and a rethinking of how economics addresses systemic global risks.

1 Introduction

For decades, scientists worldwide have consistently predicted that a new pandemic, with significant loss of life, would occur within a generation. The evidence is clear: pandemics have been a recurring part of human history. Since 1580, when the first detailed description of an influenza pandemic was recorded, 32 pandemics, including COVID-19, have occurred – roughly one every 15 years. The 20th century saw four influenza pandemics: the severe Spanish Flu of 1918 to 1920, the Asian Flu of 1957 to 1960, the Hong Kong Flu of 1969, and the milder Swine Flu of 2009.

Although the gap between major pandemics seemed to widen, with some attributing this to advancements in healthcare, medical and national security experts continued to warn of a high likelihood of another influenza pandemic within five years. While most pandemic analyses focused on influenza, it is noteworthy that the expected frequency nearly doubles if other pandemics and international epidemics are also considered. Based on historical data, the probability of an influenza pandemic occurring in any given decade is 38 percent, and nearly 20 percent over a five-year period. Including all pandemics, the chance rises to 72 percent per decade and approximately 35 percent over five years. [1] This was as true before COVID-19 as it is today. Furthermore, pandemic frequency is expected to rise due to factors such as increased global travel, closer human-wildlife interactions, intensified food production, and higher population density. [2]

Not all pandemics have the same level of impact. The health and economic effects depend on factors such as mortality rates, the disease’s spread speed, and the duration of illness, as well as economic conditions including structural inflexibility, high debt, inactivity and policies. Researchers, therefore, considered these uncertainties. Anas El Turabi and Philip Saynisch used a Monte Carlo experiment to combine pandemic frequency and economic impacts, estimating an average annual loss of $64 billion, totalling $6.4 trillion over a century. [3] They also noted a 10 percent chance of double this loss. A research team around Victoria Fan provided a higher estimate of $500 billion annually, factoring in the value of lives lost, with their pandemic loss estimate (0.6 percent of GNI) aligning with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s estimates for the costs of global warming. [4] This approach clarifies that the annual costs of pandemics are roughly comparable to the costs of Global Warming although different in the timing of impact, as the costs of pandemics are concentrated in the year of the outbreak. Assuming four pandemics per century, the costs of a pandemic outbreak could amount to roughly 25 x 0.6 percent or 15 percent of world income per pandemic on average. These costs are very large indeed and one would expect that a sound and broadly based analysis anchored in the academic curriculum would have existed pre-COVID-19. The lack of such motivates this article’s investigation of why this was the case.

This contribution also starts from a personal puzzle. In 2018 to 2019, I was member of a research team that helped to formulate the Dutch National Security Strategy. One of the risks that we considered was a very severe influenza pandemic. We noted in our scenario analysis that IC capacities would be insufficient and, alarmed by this finding, we investigated how the health authorities expected to respond. Their policy relied on triage, a form of medical rationing that prioritizes access to healthcare based on the likelihood of survival after treatment, commonly used in disasters and mass casualty events. In national security analyses, most experts assumed that countries would not resort to a full-scale lockdown, especially not for an extended period, in response to an influenza-like pandemic with relatively low mortality rates. In retrospect, this policy-free approach underestimated the costs associated with both the pandemic and the policy measures taken to combat it. The miscalculation was perhaps not so much about underestimating the economic impact of the pandemic itself, but rather the policy response, as it was assumed that countries would not commit economic suicide. Then came COVID-19 with an unexpected tsunami of lock-downs, social distancing and limitations to international travel and trade. I have labelled the policy response elsewhere “pandonomics” as a shorthand for this multifaceted cluster of policies. [5] The “onomics” part of this neologism reflects the impact of health policies on the economy as well as the response of economic policymakers to the health policy shock by means of unprecedented fiscal and monetary policies. The “pand”-part is also chosen on purpose. Indeed, pandonomics spread quicker than COVID-19 to the capitals of developed and emerging economies.

So, my personal puzzle is the research question of this article: why were economists not better prepared when the COVID-19 pandemic broke out in December 2019? Section 2 documents this unpreparedness. The point here is that the profession in general neglected the issue of (policy responses to) pandemics; the issue is not that individual economists and teams had not taken these problems on board. [6] Section 3 discusses why the world in general tends to underinvest in the production of knowledge that is necessary to understand pandemics, their frequency, their impact and the efficiency of considered health care, social and economic policies. Section 4 investigates how the large-scale use of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) came about, illustrating that the major official scripts for a pandemic did not articulate the possibility of a Great Lockdown, offering a major explanation for the unpreparedness of economists. Section 5 concludes with some final thoughts.

2 Economists were Unprepared

Gina Gopinath, then Chief Economist of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), in the preface to the April 2020 IMF World Economic Outlook gave a stunning insight into the state of affairs at the world’s most powerful economic and financial institution: “[…] a pandemic scenario had been raised as a possibility in previous economic policy discussions, but none of us had a meaningful sense of what it would look like on the ground and what it would mean for the economy.” [7]

Looking back, the seven decades leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic were an unusually fortunate time in which humanity was spared from major global disasters. World wars were avoided and the Great Recession didn’t escalate into a full-scale depression. While natural disasters became more frequent due to global warming, they largely remained localized. Future generations will likely recognize how fortunate those born after the 1950s were, particularly in terms of health. [8] This good fortune may have fostered complacency, discouraging investment in risk reduction.

Our descendants may also question how society could have overlooked the threat of pandemics and failed to take adequate precautions. The lack of investment in prevention, early detection, and response measures is perhaps most strikingly demonstrated by the findings of the Commission on a Global Health Risk Framework for the Future (CGHRFF): “[…] even countries with highly developed economies and sophisticated health systems have failed to invest in the infrastructure and capabilities necessary to provide essential public health services.” [9] This conclusion is further supported by the 2019 World Health Organization (WHO) survey on pandemic influenza preparedness, conducted among its member states. The survey highlighted two key areas: (a) preventing illness in communities (through pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical measures) and (b) the status of national pandemic preparedness plans. According to the WHO, member states scored an average of around 51 percent in these areas, indicating that nearly half of the necessary preparedness capacities were not in place. [10] The situation may have been even worse, as the global response rate to the survey was only 54 percent, a notably low figure for a governmental survey at the international level. Perhaps even more striking was that 36 percent of high-income countries, including Germany, Russia, Switzerland, and the Netherlands, did not respond. This lack of participation might suggest that these governments placed little importance on the risk of a pandemic or their preparedness for such an event. The WHO concluded that many countries were unprepared to handle an influenza pandemic.

The economics profession also appeared unprepared for a pandemic. One reason is that major financial institutions did not sufficiently highlight the pandemic threat in their flagship publications. This isn’t to say that pandemics were entirely ignored; for instance, comprehensive overviews by the OECD (2011) and the World Bank (2014) addressed pandemics in detail. [11] However, these studies were not integrated into the broader risk factors routinely covered in the economic outlooks of leading institutions. Peter Sands et al. note the absence of analyses on the economic impact of pandemics from global institutions like the IMF, OECD, and World Bank, as well as from regional bodies like the African, Asian, and Inter-American Development Banks, and private institutions including rating agencies. [12] According to the International Working Group on Financing Preparedness: “For far too long, our approach to pandemics has been one of panic and neglect: throwing money and resources at the problem when a serious outbreak occurs; then neglecting to fund preparedness when the news headlines move on.” [13]

Academic research and teaching did not perform much better in recognizing the need for preparation for pandemics. It is telling that in a brief article in the American Economic Review, Imran Rasul described the research on viral outbreaks as a “nascent literature.” [14] Moreover, the analytical approach to applied economic research into pandemics typically was of a comparative and static nature, comparing equilibria before and after a disturbance in applied general equilibrium models, considered policy (non-)response in cost benefit analysis and/or deviations from a base run in applied large-scale econometric models. Due to this focus the dynamics of a pandemic shock were ignored.

This neglect of the pandemic dynamics to a large extent explains why academic economic research did not try to combine available epidemiological model structures (that describe how disease and death develop in real time) into their models although this could certainly have been possible technically. Moreover, there was a lack of significant natural experiments that could have demonstrated the need to extend the available analyses. For the milder pandemics (in particular the Swine Flu) and epidemics, the available models and the use of economic shock-parameters provided satisfactory descriptions of economic aspects. In other words, health shocks and policy responses had not been sufficiently large to stimulate research lines with alternative approaches. [15]

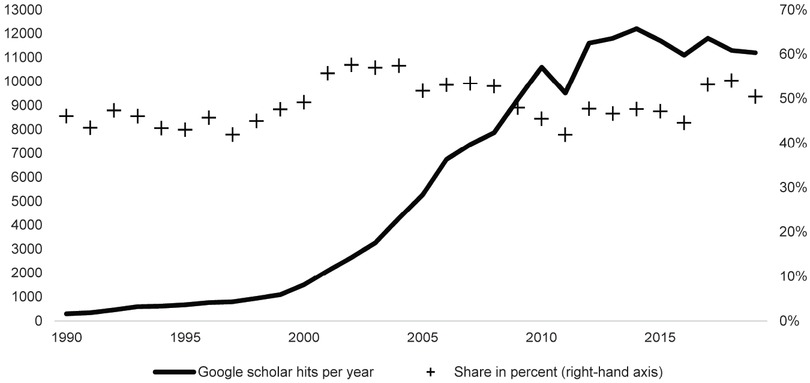

Figure 1 provides a rough illustration of the academic discourse through a Google Scholar analysis, showing the number of hits for the search terms “pandemic,” “health,” and “economic” each year. The inclusion of “health” and “pandemic” was necessary to avoid capturing metaphorical uses of “pandemic” for global economic phenomena.

Annual Scholar Hits on Economic Aspects of Pandemics before COVID-19 (1990–2019). Notes: Google scholar hits are for pandemic health economic. The share is calculated in percent of annual hits for pandemic health. Source: Van Bergeijk, Pandemic Economics, Figure 2.1.

Although this method is imprecise – since it also captures studies that include these terms in reference titles – the data offer insight into research that connects the economic and health aspects of pandemics. With this caveat, the literature shows exponential growth between 1990 and 2010, which may reflect the broader surge in academic studies fuelled by the internet and the publish-or-perish academic culture. However, what stands out is the slowdown in this growth after 2010. Economists might attribute this to the Great Recession of 2008, which likely shifted focus away from pandemics, but it is also possible that the limited impact of the 2009 Swine Flu contributed to this trend break, as a similar decline is seen in general pandemic-related hits. Despite these factors, Figure 1 highlights that academic research on the economic aspects of pandemics had peaked by the early 21st century.

The flattening of the curve, however, was not specific for economics. Flattening also occurred for pandemic-related research in general as the share of economy-related in total pandemic hits remained more or less stable at some 50 percent.

3 Underinvestment in Pandemic Preparedness

Underinvestment in pandemic preparedness is a general trait among countries. Many potential explanations exist why nations did not invest adequately in pandemic preparedness. One of the basic reasons is that prevention and preparedness often compete with immediate policy priorities that have a direct and visible effect on citizens, such as education, employment, housing, and environmental policies. These areas vie for attention and resources alongside disaster preparedness efforts. There is also competition between different types of disaster preparedness, even within the healthcare sector. Disease clusters may not only involve contagious diseases but could also stem from chemical or radiological threats or health security issues within the food supply chain. In addition to the government budget constraint, three reasons stand out: a distorted risk perception, lacking visibility of (un)preparedness in connection with a biased evaluation of the Global North’s pandemic preparedness, and the global public good nature of pandemic preparedness.

Firstly, recognizing risks accurately is challenging. Generally, human behaviour tends to exhibit disaster myopia and disregard for black swan events, which are rare but have significant societal impacts. Despite the abundant global information on climate change, natural disasters, and potential pandemics, individuals and governments often downplay their vulnerability, seeing these events as unlikely or distant. As a result, they underestimate the costs of inaction and fail to take preventive measures or secure insurance against such risks. [16] Both the public and policymakers tend to consider many disasters as improbable. This distorted perception of risk was amplified by the historically low frequency of pandemics after the 1918 Spanish Flu, with only two major pandemics in the 1950s and 1960s, a minor one in the 2000s, and two international health crises (Ebola and HIV/AIDS) that were not classified as pandemics by the WHO. These crises were often viewed as being limited to Africa. Additionally, the advanced healthcare systems in developed countries were seen as so robust that both the public and policymakers found it hard to imagine facing a life-threatening situation beyond the reach of modern medicine. [17]

Secondly, the production of essential facilities and services needed during a pandemic is largely intangible and invisible. [18] This is because the benefits of preparation are only apparent when a large-scale outbreak occurs. If no new dangerous contagious disease emerges, the investments and preparations made in the healthcare sector can appear wasteful in hindsight. Similarly, if potential pandemics are successfully contained, the preparations in other regions may seem unnecessary. Moreover, the most effective outcome in pandemic preparedness is preventing a health crisis – therefore something that does not happen, and by its very nature, remains unseen. Here also another bias plays havoc: unpreparedness is also not observed as long as a pandemic does not emerge: many advanced economies may have believed they were well prepared for pandemics, because international organizations had often highlighted that the lack of preparedness was primarily an issue for non-OECD countries. For instance, an influential World Bank study presented a geographic analysis of pandemic preparedness, identifying regions with high risk and low preparedness, such as Central and West Africa, and noted a correlation between preparedness levels and per capita income. [19]

Thirdly, pandemic preparedness depends on collective action. Mancur Olson’s theory of collective action remains a central concept for understanding how public goods are provided and how governments collaborate. [20] Olson highlighted the free-rider problem, where self-interested actors who benefit from a public good – like pandemic preparedness by other countries – lack incentive to contribute to its cost since they cannot be excluded from its benefits. Essentially, why pay for something you’ll get anyway? Charles Kindleberger emphasized that providing public goods domestically is difficult, but it becomes even more challenging in international relations, where no global authority exists. [21] If more countries underinvest in pandemic preparedness, the global public good can turn into a global public bad, leading to an uncontrollable outbreak. [22]

Underinvestment in pandemic preparedness is thus a widespread issue among nations, primarily due to a combination of factors, including competing policy priorities, distorted perceptions of risk, the invisibility of preparedness efforts, and the global collective action problem. Governments often prioritize immediate and visible needs, such as education and housing, over preparedness for future pandemics, which may seem unlikely or distant. Furthermore, the free-rider problem discourages countries from investing in global pandemic preparedness, as they may rely on the efforts of others. If this underinvestment continues, it could result in global consequences, with the risk of uncontrollable outbreaks. Underinvestment on itself can however not fully explain why so little economic work existed on the kind of policy environment that COVID-19 generated.

4 The Unexpected New Role of Social Distancing

Only a few years after the COVID-19 outbreak it is already difficult to remember the unexpectedness of the new health and economic policy shocks. Somehow, the world had overlooked the direction medical policymakers had taken. About fifteen years ago, the field of epidemiology adopted social distancing as a key tool for combating pandemics. However, the economics field may have missed this shift because the idea of returning to social distancing faced strong opposition, with many viewing it as impractical, unnecessary, and politically unfeasible. [23] This new approach, known as non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs), was regularly reviewed, updated, and published, for example in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly, where Noreen Qualls wrote:

“When a novel influenza A virus with pandemic potential emerges, non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) often are the most readily available interventions to help slow transmission of the virus in communities, which is especially important before a pandemic vaccine becomes widely available. NPIs, also known as community mitigation measures, are actions that persons and communities can take to help slow the spread of respiratory virus infections, including seasonal and pandemic influenza viruses.” [24]

The comprehensiveness of the NPI measures was, however, not well articulated, as illustrated by the following excerpt from the summary that accompanied the 2017 USA Guidelines:

“NPIs can be phased in, or layered, on the basis of pandemic severity and local transmission patterns over time. Categories of NPIs include personal protective measures for everyday use (e.g., voluntary home isolation of ill persons, respiratory etiquette, and hand hygiene); personal protective measures reserved for influenza pandemics (e.g., voluntary home quarantine of exposed household members and use of face masks in community settings when ill); community measures aimed at increasing social distancing (e.g., school closures and dismissals, social distancing in workplaces, and postponing or cancelling mass gatherings); and environmental measures (e.g., routine cleaning of frequently touched surfaces).” [25]

The document itself provides more detail, briefly mentioning the closure of public places and the role of NPIs in non-healthcare workplace settings. However, it is clear that lockdowns are categorized under “Very high severity (very severe to extreme pandemic),” with the CDC likely to adopt a more aggressive approach and recommend additional NPIs during a severe or extreme pandemic, similar to the 1918 pandemic. [26] The 2017 US guidelines also introduced a shift from the Pandemic Severity Index to the new Pandemic Severity Assessment Framework (PSAF), which for the first time included workplace transmission and attack rates in the assessment. This change in thinking and the communication of policy considerations in the US mirrors similar shifts elsewhere, such as in the EU Guide on public health measures to mitigate the impact of influenza pandemics in Europe.

“During a pandemic with lesser severe disease and of fewer falling sick, such as those seen in 1957 and 1968, some possible community measures (proactive school closures, home working, etc.), though probably reducing transmission, can be more costly and disruptive than the effects of the pandemic itself. Hence such measures may only have a net benefit if implemented during a severe pandemic, for example one that results in high hospitalisation rates or has a case fatality rate comparable to that of the 1918 to 1919 ‘Spanish flu’. For these reasons, early assessment of the clinical severity of a pandemic globally and in European settings will be crucial. Though early implementation of measures is logical, application of the more disruptive interventions too early will be costly and may make them hard to sustain.” [27]

Noteworthy is that the evidence-base for the benefits of workplace restrictions and cancellation of public gatherings and international events was lacking (and this was actually transparently reported). Pérez Velasco et al., in their systematic review of the 2009 Asian Flu pandemic, provide several explanations for this gap in our knowledge:

“This may be explained by the nature of non-pharmaceutical interventions, for which effectiveness and cost effectiveness are difficult to assess. For instance, it may be unethical to restrict travel or to introduce public communication and advisory measures for only specific population groups. There is a lack of standard protocols for non-pharmaceutical interventions resulting in a large variability of practice across settings. Also, most of the non-pharmaceutical interventions are complex, involving multidimensional aspects and difficulties to control confounding factors. Lastly, in the absence of a pandemic event, it is difficult to introduce radical public measures (e.g., travel restrictions, school closure, and quarantine), which hinder opportunities to generate robust and reliable evidence on effectiveness.” [28]

Stephen Eubank and colleagues note three key aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic that explain this health policy reaction despite the lacking evidence base for the unprecedented use of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs). [29] First, the absence of both a vaccine and anti-viral treatments. Second, the newness of the disease which meant that public perceptions created their own dynamic. Third, the availability of mobile internet access both for communicating, advocating and monitoring social distancing measures. And comparing the earlier controversy about the use of NPIs with the general adoption of the measures during the COVID-19 pandemic, they observe:

“A beneficial result of these differences is that social distancing measures whose practicality was suspect then have been widely adopted today even in the absence of – or sometimes in opposition to – official guidance. School closings, community programs to support vulnerable people, state and county policies to require social distancing, as well as business and government support for telecommuting are widespread around the world.” [30]

5 Concluding Remarks

The issues related to pandemic preparedness remained in the health policy and health economics domains and did not reach the macroeconomic debate on the impact of shocks. In this sense economists were unprepared for the COVID-19 pandemic. They were not unprepared because the probability was underestimated or because its raw policy-free impact was not understood, but because economists had not realized that a new treatment was being designed and would be administered. The economic side effects of this medicine (the Great Lockdown), however, were not beforehand transparent to society and policy makers, although elements of NPIs (or endogenous reactions with similar expected behavioural impact) were sometimes included in sensitivity analyses and alternative scenarios. The economic consequences of social distancing had been recognized in policy discussions amongst health care analysts, but unfortunately never entered the economic domain as an issue of concern. [31] The consequences would become transparent soon after COVID-19 hit the Western market economies. Economic consequences of NPI-based health policies are not only important for economic advice, but also for healthcare – if only because expensive or extensive policies that cannot be sustained economically are also a threat to non-pandemic health care and may therefore have a long-term health impact that is not recognized by current epidemiological models. A choice for the most cost-efficient NPIs is only possible if coordination between policy areas is strengthened and can only be evidence-based if economic and epidemiological studies are integrated. [32]

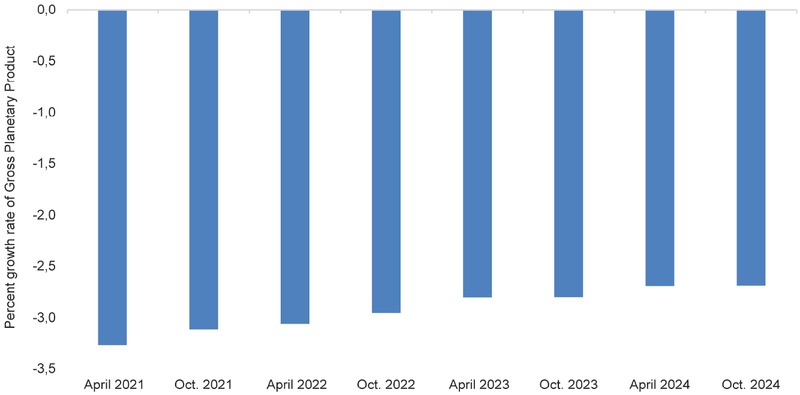

It is still difficult to attach a number to the economic and social costs of the COVID-19 pandemic, because statistical observation broke down. [33] Data collection was difficult and delayed and our view on the economy during the Great Lockdown is still changing due to revisions as illustrated in Figure 2. It is important to note that Figure 2 does not relate to forecasts but to estimates after the fact. As such Figure 2 indicates that information which became available in 2021 and later years, led to the changing estimation of what happened in 2020. The fact that these revisions are still ongoing offers a sobering lesson for researchers and warrant caution in economic assessments of the Great Lockdown and the associated policies.

Decreasing global Gross Planetary Product. Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook databases, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/SPROLLs/worldeconomic-outlook-databases#sort=%40imfdate%20descending (09.06.2025).

At the same time Figure 2 offers food for thought, since the impact of very severe lockdown policies did not seem to bite as hard into world economic production as pre-COVID-19 analyses had suggested. This may be due to the fact, that COVID-19 was not as deadly as other near pandemics, or that the economic policies that were developed and deployed during the Great Lockdown were able to reduce the hardship.

Does this mean that we can afford pandonomics? Fundamentally, pandonomics represents a catastrophic situation: a high-impact event that is likely to survive a single occurrence but has a low chance of surviving repeated exposures. [34] We are discovering that lockdowns require both discipline and endurance, qualities that are lacking in many modern Western democracies. [35] We are coming to terms with the opportunity costs associated with prioritizing COVID-19: the health consequences for non-COVID-related sectors, the mental and societal toll that will eventually affect public health, and the economic costs, including rising debt and quantitative easing. While estimating the exact costs will take time, as some effects unfold gradually, the message is clear: we need to develop alternatives to lockdowns. This area of pandemic preparedness is where economic research and policy can offer significant insights.

About the author

Peter van Bergeijk is emeritus professor at the Institute of Social Studies of Erasmus University, the Netherlands. He wrote extensively on the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, including the relationship between pandemics and (de)globalization. His most recent book is: P.A.G. van Bergeijk, On the Inaccuracies of Economic Observations: Why and How we could do Better, Cheltenham 2024. It contains a chapter on measurement errors during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Acknowledgement

Comments by anonymous referees are gratefully acknowledged.

© 2025 Peter A. G. van Bergeijk, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Obituary for Eckart Schremmer

- Special Issue Articles

- Epidemics and Pandemics in Economic-historical Perspective – An Introduction

- Cholera in the City of Poznań: Did the Death Toll of the 1866 Cholera Epidemic Reflect Social and Economic Differences?

- The Mortality Impact of Cholera in Germany

- When Diseases Return from the Epidemiological Honeymoon: The Reemergence of Smallpox in 19th Century Germany and its Lessons for Public Health Policies after COVID-19

- On the Economic Costs of the Spanish Flu Pandemic in Germany: An attempt at Assessing GNP Lost for 1918

- Malaria in Catania/Sicily: Local Manifestations and International Scientific Cooperation During a Pandemic in the 1920s

- Geographical Aspects of Diphtheria in England and Wales: Immunisation and the Spatial Sequence of Retreat to Effective Elimination, 1921 to 1964

- Pandonomics: Why Economics was Unprepared for COVID-19-Policies

- Research Forum

- “Stupid” German Money? Bonus Interest Rate Payments on Savings Deposits During the Stagflation of 1967 to 1984

- Geography and Space in Recent Economic History

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Obituary for Eckart Schremmer

- Special Issue Articles

- Epidemics and Pandemics in Economic-historical Perspective – An Introduction

- Cholera in the City of Poznań: Did the Death Toll of the 1866 Cholera Epidemic Reflect Social and Economic Differences?

- The Mortality Impact of Cholera in Germany

- When Diseases Return from the Epidemiological Honeymoon: The Reemergence of Smallpox in 19th Century Germany and its Lessons for Public Health Policies after COVID-19

- On the Economic Costs of the Spanish Flu Pandemic in Germany: An attempt at Assessing GNP Lost for 1918

- Malaria in Catania/Sicily: Local Manifestations and International Scientific Cooperation During a Pandemic in the 1920s

- Geographical Aspects of Diphtheria in England and Wales: Immunisation and the Spatial Sequence of Retreat to Effective Elimination, 1921 to 1964

- Pandonomics: Why Economics was Unprepared for COVID-19-Policies

- Research Forum

- “Stupid” German Money? Bonus Interest Rate Payments on Savings Deposits During the Stagflation of 1967 to 1984

- Geography and Space in Recent Economic History