Malaria in Catania/Sicily: Local Manifestations and International Scientific Cooperation During a Pandemic in the 1920s

-

Lene Faust

Lene Faust is an associate researcher at the Institute of Social Anthropology, University of Bern. She obtained her PhD from the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg in 2019. Her main research areas include political anthropology and the anthropology of the Mediterranean. Currently, she specializes in studying the transformation of Mediterranean societies with a particular focus on Sicily.and Christian Franke

Christian Franke teaches economic history/pluralistic economics at the Faculty of Economics at the University of Siegen. He obtained his PhD in 2005 from the University of Siegen, where he also completed his habilitation in 2010. His research focuses on the history of international economic relations, European integration, and infrastructure regulation.

Abstract

This article examines how international scientific cooperation addressed the malaria pandemic in the 1920s, focusing on the local context of Catania, Sicily, and a study trip to Sicily by the League of Nations Malaria Commission. In 1925, the Rockefeller Foundation established a field laboratory in San Giuseppe La Rena on the outskirts of Catania, and Italy became a key site for international scientific collaboration. Drawing on League of Nations archives and contemporary publications, the article demonstrates that integrating local and international perspectives proved to be a major challenge. Malaria varied greatly in its manifestations and underlying causes depending on local conditions, making targeted local interventions more effective than broadly-based international comparative approaches. The Malaria Commission sought to synthesize diverse regional problems and control strategies across Europe to develop general assessments and recommendations. However, it ultimately failed to translate these findings into concrete influence on local policy; at least in the case of Catania, as this study shows, the impact remained limited.

1 Introduction

“And you seem to feel it with your own hands – as if the thick, smoking earth, stretching endlessly back to the mountains that enclose it, from Agnone to snow-capped Mongibello [a Sicilian term for the volcano Etna], stagnates in the plain like the oppressive heat of July. [...] Below, the lake of Lentini lies still, like a lifeless pond with shallow banks, without a boat, without a tree on its shore – smooth and motionless. Along the banks, oxen graze sluggishly, scattered and scarce, their bodies caked in mud up to their chests, their fur unkempt. When the cowbell rings from the herd, wagtails take silent flight in the vast stillness, while the shepherd, yellow with fever and white with dust, briefly lifts his swollen eyelids and raises his head from the shade of the withered rushes. Malaria seeps into your bones with every bite of bread you eat, and as you open your mouth to speak or walk through streets suffocated by dust and sun, your knees grow weak, and you slump forward, resting your head against the mule’s yoke as it trudges along.” [1]

With these words, Giovanni Verga, a famous fiction writer from Catania, Sicily, described the devastating effects of malaria in the plains outside Catania at the end of the 19th century. The disease was not an abstract threat but an omnipresent force that shaped the daily lives of those who had to work outside the city. It permeated every corner of the landscape, rendering it nearly uninhabitable, as it brought certain death to so many. In southern Italy alone, malaria claimed around 20,000 lives per year at the time – 18,830 deaths were recorded in 1887, for example. [2]

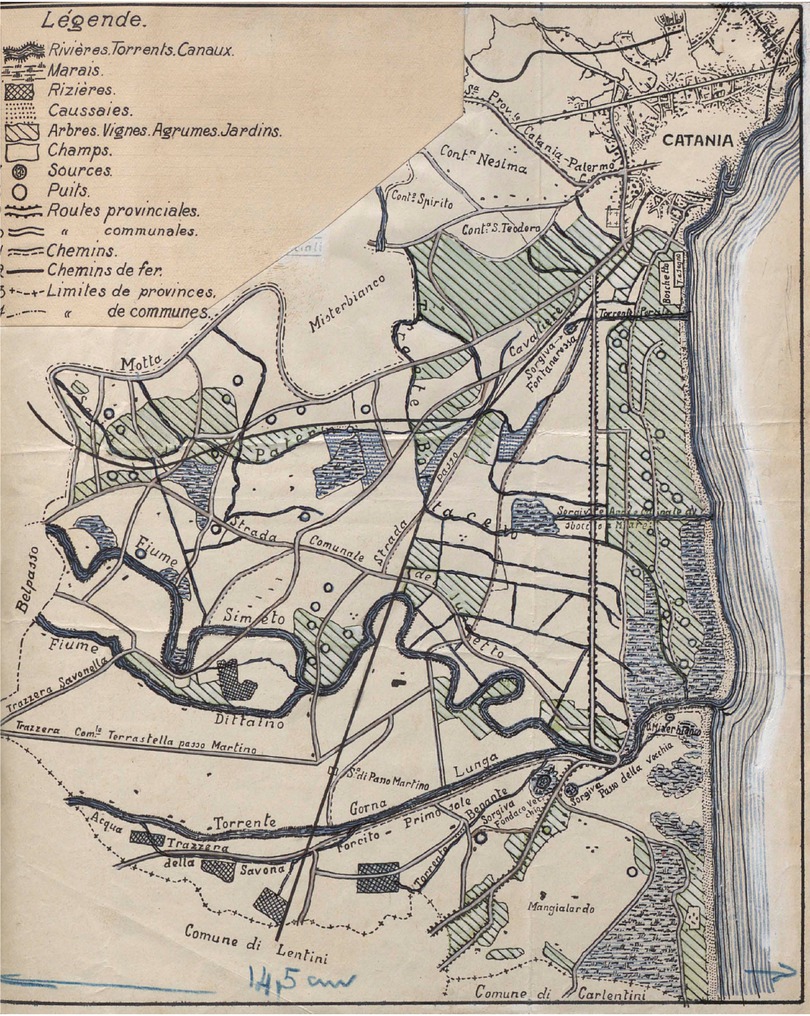

The name malaria originally referred to the bad air once believed to cause the illness. It was only at the end of the 19th century that scientists discovered that malaria was transmitted to humans by female mosquitoes of the Anopheles genus. Before this breakthrough, the disease had long been attributed to the miasma rising from swamps and stagnant water – landscape features that characterized areas such as San Giuseppe La Rena. The swampy vegetation surrounding the mouth of the Simeto River created ideal conditions for the spread of Anopheles mosquitoes, and consequently, malaria. Additionally, the construction of water reservoirs and irrigation canals further contributed to the proliferation of the disease. [3]

In villages such as San Giuseppe La Rena, south of Catania, which lies in the very plain that Giovanni Verga describes, people still remember the many lives lost to malaria. Even today, stories are told of siblings who, sleeping in the same bed, unknowingly infected each other – a lingering testament to the persistent misunderstandings about the disease that has left its mark on this region. San Giuseppe La Rena holds particular significance in the history of malaria, as the American Rockefeller Foundation established an international scientific research station there in 1925 to develop strategies for combating the disease.

San Giuseppe La Rena is just one of many examples in Europe and around the world where malaria, which seemed to have been brought under control in Europe at the beginning of the 20th century, resurged after the First World War to such an extent that it developed into a pandemic. This crisis made the fight against malaria a key issue of international cooperation in both politics and science during those years.

Against this backdrop, this article explores the following questions: How did the League of Nations Malaria Commission attempt to combat the malaria pandemic after the First World War? What forms did international scientific collaboration take? Additionally, local conditions must be considered: What specific challenges arose in dealing with malaria at the local level? What measures were implemented in Sicily to combat the disease, and how did these efforts influence international scientific cooperation, particularly within the League of Nations Malaria Commission?

Previous research has examined international cooperation within the framework of the League of Nations Malaria Commission from various perspectives, though primarily in broad overviews or within very specific contexts. For example, the history of medicine has addressed the Malaria Commission in studies on the Health Committee of the League of Nations [4] or by focusing on individual scientists and their contributions. [5]

From an economic and business history perspective, research has explored the production, development, and distribution of anti-malaria drugs. In this context, international scientific collaboration within the Malaria Commission in the late 1920s and especially the 1930s played a significant role, as competition between quinine-based and synthetic malaria treatments was shaped by the Malaria Commission’s decisions. [6] Regarding malaria in Italy, historical studies have emphasized the significant impact of pandemics on socio-economic development, though the focus has largely been on northern Italy and efforts to combat malaria there. While it is acknowledged that pandemics with high mortality rates were primarily a phenomenon of southern Italy and Sicily, this has not led to in-depth studies. [7] Moreover, the extent to which malaria in Sicily contributed to (international) scientific research remains largely unexplored, despite the fact that the malaria epidemic of the 19th and early 20th centuries provided key impetus for scientific inquiry, including at the University of Catania. [8]

There are very few studies that specifically examine the relationship between international scientific cooperation, local malaria epidemics, and the concrete strategies and measures implemented in malaria-affected regions. This is particularly true for European efforts to combat malaria. Since diseases such as malaria are not isolated crises but fundamental factors shaping economic and social development – manifesting differently in local contexts – this study will focus on international scientific cooperation in relation to a specific malaria-affected region near Catania, Sicily. The aim is to analyze the interactions between local approaches to managing malaria risks and international scientific collaboration, particularly in the production of knowledge.

The focus on Catania, Sicily, and Italy is based on several key reasons. First, Italy – particularly southern Italy and Sicily – was among the regions most severely affected by malaria in Europe during the 19th and early 20th centuries. The area around Catania was one of the worst-hit regions. [9] Since the founding of the Kingdom of Italy, successive governments prioritized the fight against malaria, including the fascist government under Benito Mussolini, which came to power in 1922. [10] Second, Italian malaria research, including work conducted at the University of Catania, was among the most advanced in the world. Notably, the Italian malaria researcher Alberto Lutrario became the first chairman of the League of Nations Malaria Commission. Italy was regarded by the Malaria Commission as a model for malaria control and was therefore included as a key case study in its research efforts. Third, Italy saw significant international involvement from the Rockefeller Foundation, which launched a major research program in the mid-1920s. The foundation established a malaria school in Rome and provided substantial financial support for the first Malaria Congress, held in Rome in 1925. [11]

This study focuses on the 1920s, a period when malaria escalated into a pandemic in Europe before receding into localized epidemics. Although there were renewed outbreaks during and after the Second World War, malaria was largely eradicated from the European continent in the following years. However, from a global perspective, malaria remains an endemic disease with persistently high infection rates outside Europe.

To address the research questions posed, this study draws on archival materials from the League of Nations, the German Foreign Office, the German Federal Archives and the Archives of the Rockefeller Foundation. Additionally, numerous contemporary publications by key actors were examined as primary sources. [12]

This article combines a general approach to understanding the management and controlling of malaria with a case study in the specific geographical and epidemiological context of Sicily. It begins with providing an overview of the history of malaria and the methods used to combat it in Europe. It then historically contextualizes malaria and the fight against malaria in Sicily with a focus on the events at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. The main part of the article provides an analysis of the measures used to combat malaria, based on international scientific cooperation through the Malaria Commission of the League of Nations and the Rockefeller Foundation, which acted in response to the malaria pandemic of the early 1920s. Their cooperation in Italy is examined, with a particular focus on Sicily, which was neglected by the Italian state for a long time. The effects of the international initiatives are discussed, as well as the insoluble conflicts that led to the end of the Rockefeller Foundation’s work in Italy in 1934. A study tour by the League of Nations Malaria Commission to Sicily in 1926 is of central importance for the international dialog and is discussed in more detail here with regard to the long-term effects of international efforts and cooperation. This is followed by a concluding evaluation of the international scientific cooperation of the 1920s to combat malaria.

2 Malaria – A Multifaceted Scourge of Humanity

Many scientists consider malaria to be the most devastating disease in human history. Few other illnesses have been as widespread, claimed as many lives, manifested in such diverse forms, and remained largely undefeated for so long. [13] Just as malaria presents a highly varied clinical picture, efforts to combat the disease during the interwar period were equally diverse. Conflicting schools of thought, methods, and approaches emerged, reflecting the complex nature of the disease.

One reason for these diverse approaches was the significant regional variation in the course of the disease. People in different parts of the world had developed varying levels of natural immunity to malaria, further complicating treatment strategies. Additionally, malaria primarily affected (and continues to affect) countries with limited financial resources and inadequate medical infrastructure, making effective disease control challenging. This is also evident in the central role played by the Rockefeller Foundation in supporting Italian malaria research during the 1920s and 1930s. [14]

Against this backdrop, various control methods had emerged up to the 1920s, which can be broadly categorized into three main approaches:

Targeting the Disease in Humans – This approach focused on treating infected individuals, primarily through the administration of quinine-based medications. Scientific research aimed to improve the tolerability of these treatments and adapt their application to local conditions.

Addressing Socio-Economic Conditions – This strategy emphasized preventive measures such as public education, awareness campaigns, and environmental interventions, particularly the draining of mosquito breeding grounds, to reduce the population of malaria-carrying mosquitoes. The fascist government’s Grande Benefica program can be placed within this context. It was both a land reclamation initiative – intended to drain dangerous swamps for agricultural use – and a malaria-control effort aimed at eliminating mosquito breeding sites.

Vector Control – This approach focused on eliminating mosquito larvae by using so-called Paris Green, a highly toxic, emerald-green crystalline powder of copper acetoarsenate, used as an insecticide to target mosquito populations.

The opinions of scientific experts on the most effective malaria control strategy varied widely and depended on their scientific background, regional focus, research traditions, and national policies. As a result, the fight against malaria in the interwar period was characterized by a clash of differing perspectives and methodologies.

The First World War had marked a pivotal moment in the fight against malaria, as it severely disrupted existing healthcare systems in many countries. The war not only contributed to the spread of the disease but also allowed malaria to take root in a large number regions, leading to new epidemics that persisted for decades. [15] War-related factors such as forced migration, mass troop movements, and returning soldiers played a significant role in transforming malaria into a cross-border issue, turning it into a full-scale pandemic in Europe. While malaria had primarily afflicted regions in Asia, the Americas, southern Europe, and Africa before the war, it now became a pan-European crisis, garnering serious political attention as a major public health emergency. [16] The years 1922 to 1924 marked the peak of the malaria pandemic across Europe, with the Soviet Union alone reporting approximately 18 million infections. [17]

3 Malaria in Sicily – A Historical Perspective

Malaria has been Italy’s most serious public health issue since ancient times. At its peak in the 19th century, the disease was estimated to claim around 100,000 lives annually. [18] A key difference between northern and southern Italy was the ability to control malaria. In the north – extending as far as the region just south of Rome – the disease was more easily eradicated due to a higher standard of living. In contrast, malaria remained a persistent and severe threat in the south. [19]

The socio-economic consequences of malaria epidemics were especially severe in Sicily. This was one of the reasons why, in 1922, Italy established its third malaria school in Caltanissetta – following those in Rome and Venice – to train medical personnel in combating the disease. [20]

Large areas of land, particularly the swampy region of the Piana di Catania (Plain of Catania) in the valley and delta of the Simeto River between Syracuse and Catania in eastern Sicily, were virtually uninhabitable due to malaria. In the northern part of Catania, human activity exacerbated the problem. Water that was collected in basins and canals (including unauthorized branch canals) on the lower slopes of Mount Etna, was used for agricultural irrigation. Poor maintenance and sanitation led to water stagnation, creating ideal breeding grounds for malaria-carrying mosquitoes. [21]

The high risk to life and health in malaria-affected areas resulted in (noble) landowners not residing on their latifundia (large agricultural estates), but living in towns such as Catania instead, leaving the management of their lands to the so-called gabelotti (leaseholders or estate managers). [22] Given the exceptional agricultural fertility of the Piana di Catania, landowners could afford to delegate the administration of their estates, even accepting crop losses or reductions in income: just to keep safe from the risk of malaria infection.

Malaria had devastating demographic consequences: the life expectancy of a male agricultural worker in Sicily was only 22.5 years, compared to 35.7 years in the rest of Italy. [23] Some have even attributed certain stereotypical Sicilian traits, such as secrecy and lethargy, to malaria’s neurological effects, as the disease can cause anemia and cognitive impairments that may also be passed down to future generations. [24]

Because of malaria’s immense impact, Italian governments were compelled to take extensive measures to combat the disease as early as the 19th century. Between 1901 and 1906, a nationwide control program was implemented, requiring the mandatory reporting of all malaria cases and prioritizing the treatment of infected individuals with quinine, which is a natural active ingredient derived from the bark of the cinchona tree that disrupts the malaria parasite’s ability to digest hemoglobin in red blood cells. The Italian state subsidized quinine production and organized its free distribution, particularly targeting farmers and agricultural workers in the hardest-hit regions. Landowners were also required to contribute to the program’s funding.

At the core of this initiative was a state-controlled quinine-production monopoly, with large-scale production in Turin covering two-thirds of Italy’s demand, while the remaining third was supplemented by imports. [25] Additionally, the government established a monopoly on the distribution of quinine-based treatments. This program led to a significant decline in malaria-related deaths.

By the 1910s, malaria was widely believed to have been eradicated in most of Italy, due to the effectiveness of the government programs. However, since the root causes of the disease were never fully addressed, its pathogens and vectors remained prevalent. These shortcomings of the nationwide strategy became evident during the First World War, when the supply of quinine and quinine-based medicines could no longer be guaranteed, and much of the Italian healthcare system collapsed. By 1917 at the latest, malaria resurged dramatically, fueled in part by disruptions to global supply chains, particularly from Asia. Some regions, such as Catania, were especially hard hit.

The resurgence of malaria compelled the fascist government, in power since 1922, to take decisive action. In addition to expanding the distribution of quinine, Mussolini’s administration launched the Grande Benefica, one of Italy’s most ambitious infrastructure projects. The large-scale drainage of swampy areas – prime breeding grounds for the Anopheles mosquito, the primary vector of malaria – became a hallmark of Italy’s modernization efforts. [26] These measures not only made vast tracts of land arable through the implementation of modern water management systems but also contributed to a significant decline in malaria-related deaths. However, the initial focus of the project was limited to the extensive marshlands of northern Italy, such as the Pontine Marshes south of Rome. [27] Sicily, despite its high malaria burden, was not included.

4 International Scientific Cooperation

4.1 The Malaria Commission of the League of Nations

In response to the malaria pandemic of the early 1920s, the member states of the League of Nations placed malaria on the agenda of their Health Committee. In 1923, the Committee established a dedicated Malaria Commission, which began meeting regularly in 1924. Until the outbreak of the Second World War, it remained one of the League’s most active public health commissions. [28] Its role was not only to provide short-term solutions to pressing malaria-related issues but also to develop long-term recommendations and strategies for managing the disease.

The Malaria Commission aimed to formulate practical guidelines for addressing malaria in the many high-risk areas affected by this highly complex and regionally diverse illness. Additionally, it sought to develop comprehensive action plans that integrated various malaria control methods. One of the Malaria Commission’s key objectives was to analyze the different anti-malaria strategies that had emerged at local and national levels and to propose a unified approach – one capable of bridging the deep divides among proponents of differing strategies. From the outset, the Malaria Commission was not only a health policy and scientific body but also held significant economic influence. It recommended measures that required substantial financial investments from national governments and local authorities, thereby influencing markets, where considerable profits could be made. [29]

The Malaria Commission was composed of representatives from various League of Nations member states, all of whom were leading scientific experts in malaria research and treatment. The Malaria Commission was chaired by the Italian Alberto Lutrario, who also served as the Director-General of Public Health in Italy. Other key members included Sydney Price James from the UK and Émile Marchoux from France, both renowned figures in the field of clinical malaria research. [30] The Malaria Commission was further supported by permanent members such as Bernhard Nocht (Director of the Hamburg Institute for Tropical and Maritime Diseases), [31] Donato Ottolenghi (Bologna), Gustavo Pittaluga (Madrid), P. M. Bernard (Paris), and Gustave Reynaud (Algiers), as well as so-called correspondents like the Dutch scientist Nicolaas Hendrik Swellengrebel. [32] Notably, the Malaria Commission exhibited a remarkable continuity in its personnel over time. Among its advisors was James Hackett, the representative of the Rockefeller Foundation in Italy. [33] The Malaria Commission had a distinctly Eurocentric membership and focus. In its early years, it concentrated on malaria epidemics within Europe, focusing on European conditions while largely overlooking the unique challenges faced by malaria-endemic regions outside the continent. [34]

During its initial phase, the Malaria Commission focused on compiling and analyzing existing knowledge through questionnaires, establishing a differentiated reporting system on treatment methods and success rates across various malaria-affected regions. Given its broad mandate and the diverse viewpoints among its members, the Malaria Commission initially adopted a holistic approach, conducting a comprehensive assessment of the situation before formulating recommendations for malaria control. [35]

A key aspect of its work – and the focus here – was the organization of joint study tours by its members to different malaria-endemic areas. These field visits allowed the Malaria Commission to document local treatment and prevention methods, variations of the disease, and patterns of natural immunity. [36] Additionally, the Malaria Commission was involved in educational and training initiatives at various malaria research institutions, where it disseminated scientific doctrines and treatment methodologies, shaping future malaria control strategies. Given the considerable heterogeneity of malaria research in the early 1920s, the Malaria Commission faced a significant challenge: it had to consolidate, analyze, disseminate, and categorize an array of scientific findings. Its goal was to enhance transparency regarding the state of malaria research and to make a lasting contribution to the international scientific network, fostering greater collaboration in the fight against the disease. [37]

The differences in approach regarding the right methods, strategies and active substances to combat malaria were a major challenge for the Malaria Commission in the first years of its work. [38] It was also unclear whether the Malaria Commission should pursue the long-term goal of eradicating malaria or help infected people in the short and medium term. In this respect, the early years of its work – which were reflected in the first two general Malaria Reports of 1925 and 1927 – were characterized by a pragmatic approach in order to develop a kind of global anti-malaria culture and to make the Malaria Commission an internationally recognized authority that coordinated the fight against the disease across borders and used economic resources efficiently to help as many people as possible.

The Malaria Commission and its general reports came to gain enormous international authority and became increasingly important for national governments, local authorities and institutes in choosing their strategies against malaria. The scientific judgments of the Malaria Commission and its directly and indirectly formulated policies thus acquired ever greater economic significance. This, of course, increased the interest of states and companies in filling the few positions in the Malaria Commission and influencing its goals and recommendations. [39]

4.2 The Rockefeller Foundation

International scientific cooperation was not limited to the Malaria Commission of the League of Nations. Of importance both for the Malaria Commission and for the fight against malaria in Italy were the financial, institutional and personnel support provided by and the scientific cooperation with the Rockefeller Foundation. [40] This organization had been established in 1913 by the US-owners of Standard Oil, with the aim of promoting the welfare of mankind throughout the world. In the first ten years after its founding, the Rockefeller Foundation rapidly expanded its activities beyond the United States and launched major public health campaigns in Latin America, Europe, and Asia, initially focusing on malaria control.

The Rockefeller Foundation showed an interest in becoming involved in Italy, after it had successfully implemented local projects in South American countries. Initial contact was made in 1922 by the Italian government, which had a strong financial interest in working with Rockefeller. The Foundation then sent its employee Lewis Hackett, who had experience with the South American projects, on a study tour to Italy. He was to spend several months of 1924 intensively investigating the situation in the various malaria regions of the country. [41]

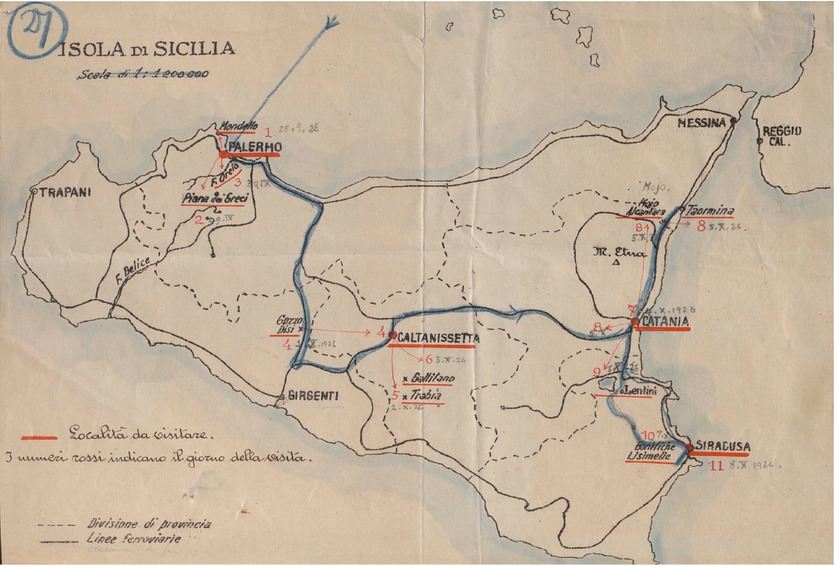

Lewis Hackett worked intensively with the Italian malariologist, Alberto Missiroli, who, unlike the majority of his Italian colleagues, saw the need to combat the malaria vectors. In this context, Hackett also undertook a nine-day tour to Sicily, where he spoke with the relevant authorities. According to Hackett, his experiences in Sicily in particular taught him that malaria “should be studied piecemeal in the hope that many of the less difficult malaria situations could be cleared up by local initiative, well directed.” [42]

Lewis Hackett was not impressed by the so-called “Italian method of malaria control” but noted on a first visit to the peninsula that malaria was still endemic in many regions. In line with the Foundation, he rejected the Italian method, which relied on quinine treatment, which he considered to be purely palliative. [43] Hackett also expressed that he was very surprised at why the Italian government in Rome paid so little attention to malaria control in Sicily. He wrote in his final report: “I found in Sicily the greatest local interest in and reaction to the malaria situation which I have yet seen in Italy.” [44] In order to deepen the epidemiological knowledge of local conditions and improve the technical organization, Hackett proposed a comprehensive support and study program for Italy to the Rockefeller Foundation, including the establishment of research centers and stations in various malaria regions of the country.

In 1925 the Rockefeller Foundation sponsored the foundation of the Italian Stazione Sperimentale per la Lotta Antimalarica (Experimental Station for Malaria Control) in Rome, headed by Alberto Missiroli. In contrast to the big Malaria research institutes in London, Paris and Hamburg, which had a strong clinical focus, the center in Rome was to have a stronger focus on prophylactic malaria control, following the example of Rockefeller’s very successful anti-malaria campaigns in the USA and Central and South America. Rockefeller also financed malaria therapy through the new center and founded the center for Malaria Therapy and Cure at the Santa Maria della Pietà Psychiatric Hospital in Rome in 1927. [45]

In October 1925, the Rockefeller program in Italy was ceremoniously opened with a major international Malaria Congress under the auspices of the Malaria Commission of the League of Nations. The Rome Congress, which Mussolini personally opened, [46] was used as a stage to celebrate both the achievements of Italian Fascism and that of Italian malaria research, which had long been one of the world leaders. While the League of Nations and the Italian government used the event, which was largely financed by the Rockefeller Foundation, as a stage for demonstrating their own achievements, the Rockefeller Foundation hoped to be able to introduce its approach to combating malaria more effectively into international scientific cooperation.

For the Rockefeller Foundation, the program in Italy was to be a pilot project to combat malaria that would serve as a model for other European countries. The program envisaged gradually transferring financial responsibility to the Italian state, which was unable to provide enough state funding in the early and mid-1920s. The Rockefeller Foundation established mixed financial systems according to which the local authorities had to contribute to the malaria campaigns and were to switch to self-financing in several stages (usually two sequential three-year contracts). However, the Foundation financed most of the basic equipment and training of staff. The Rockefeller Foundation pursued an approach that was intended to be more cost-effective than the prophylaxis and control of human diseases with quinine preparations and the draining of swamps using complicated hydraulic systems. [47]

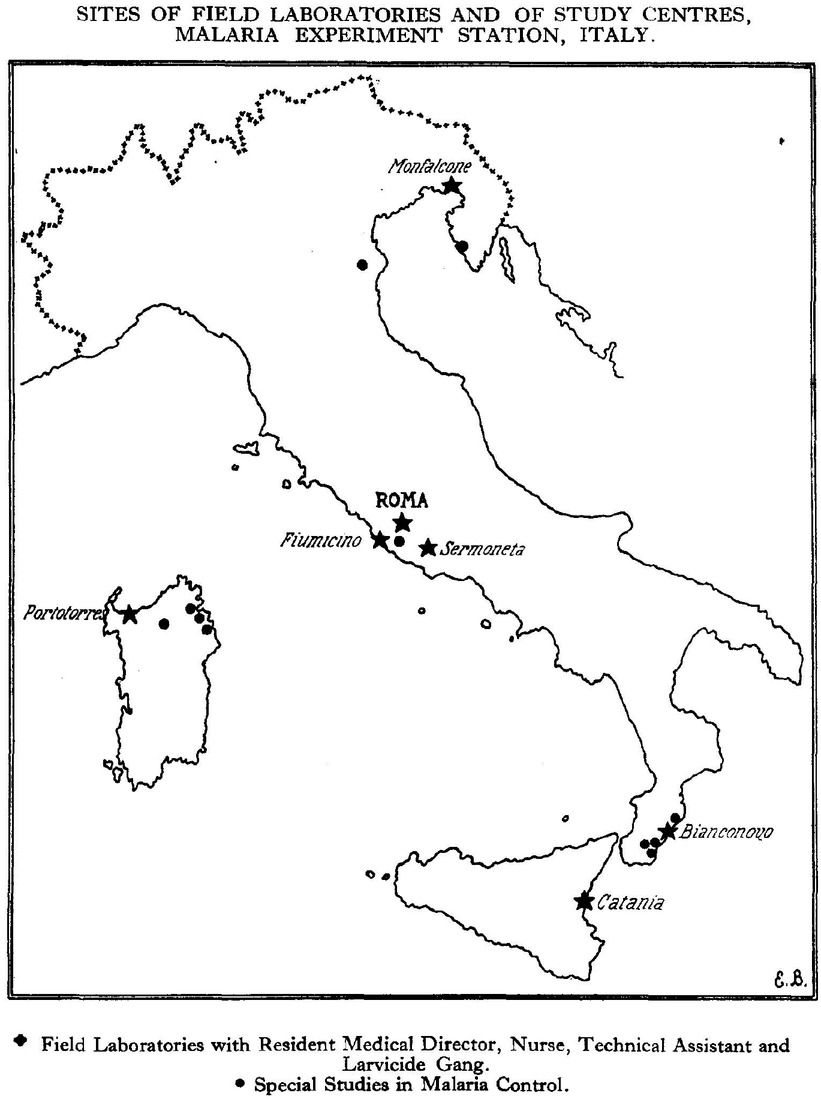

The geographical focus of the Rockefeller Foundation’s program was on the northern Italian malaria regions in the Po Valley or the Pontine Marshes south of Rome, partly at the request of the Italian government and because of the cooperation with Italian malaria researchers in these locations. In addition, smaller field laboratories were set up in heavily affected areas such as Sardinia, Calabria or Sicily, one of them south of Catania/Sicily in the village of San Guiseppe La Rena. [48]

Spraying of Paris Green in San Guiseppe La Rena.

The focus was on the precise analysis of local conditions, especially the breeding sites of mosquito larvae, and the control of larvae by spraying Paris Green. [49] Between 1925 and 1927, many malaria research centers were opened, which then mapped the local environment, located larval breeding sites and then combated them with Paris Green, the highly toxic green compound made of copper acetoarsenate. The Foundation made a massive contribution to systematically mapping water areas in order to then take action against the larvae, as well as training personnel, including medical staff as well as technicians who sprayed swamps and watercourses with Paris Green during nine months of the year.

Eventually, the Rockefeller Foundation opened seven field laboratories and eight further special studies centers in Italy. The former consisted of a scientific director, a nurse, technical assistants and a larvade gang, which was responsible for spraying Paris Green and monitoring the development of the larvae.

The field laboratory under the direction of Dr. Battisti in San Guiseppe la Rena aimed to “carry out the ‘desanophelization’ of a suburban area covering an area of 900 hectares.” [50] This area extended over a radius of six kilometers around Catania.

When the field laboratory in San Giuseppe la Rena was opened, the spleen index (an indicator of malaria infestation) was 20 percent in the Catania area in general and 85 percent in San Giuseppe la Rena specifically. Here, the municipal health department of Catania maintained a treatment station right next to the Rockefeller Foundation’s field laboratory.

All mosquito breeding sites were searched for and localized in San Guiseppe La Rena. The effort and expense involved was enormous. Battisti and his team had to count all water springs, which formed small swamps where they emerged from the ground. They had to check the irrigation canals in the area, which formed a network of around 50 kilometers in length. They also had to check the retention basins on all citrus plantations. Apart from checking already existing water, the team dug large numbers of shallow wells. All of the various pools of water were then treated with Paris Green every ten days. The treated water bodies were then checked for the development of larvae and the presence of adult Anopheles mosquitoes. Apart from the strenuous field work, the team had to prepare documentation. [51]

The research centers and field laboratories operated by the Rockefeller Foundation in Italy, contributed significantly to testing and researching methods of malaria control that focused on the pathogens and transmission. Their intervention redirected malaria research to parasite control and then to the control of contagion by testing Paris Green, which was shown to be effective in small mosquito breeding sites such as puddles, canals and ditches. They thus explored a method that had previously been little used in European malaria research.

Map of the Rockefeller Foundation malaria activities in Italy.

5 The Early Study Tours of the Malaria Commission

The Malaria Commission’s study tours were intended to study local variants of malaria and their control methods. At the beginning of the Malaria Commission’s work, they were intended to help compile and compare knowledge, findings and strategies that had been developed in the local epidemic hotspots. They also provided a platform for international dialogue, since tour members got to know each other, exchanged knowledge and ensured that knowledge circulated and was pooled among its members. [52]

In 1924, the Malaria Commission organized a study tour through Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, Greece, Romania, Bulgaria, Russia and Italy, that lasted nearly four months. Participants of the trip included members of the Malaria Commission as well as invited malaria experts from various League of Nations member countries. The results of the first study tour were published as part of the first general Malaria Report of the Malaria Commission in 1925.

Unfortunately, the report was highly biased, having been written by a small editorial team led by the British malariologist Sydney James, an advocate of quinine treatment and prophylaxis. Although the members of the study tour had very different opinions, the first general Malaria Report was very one-sided. It advocated exclusively the treatment of infected people with quinine and the prophylactic administration of the corresponding preparations, as had also been established by the Italian government. The extensive studies by the Rockefeller Foundation, which had long been carried out in the Americas and had now also been launched in Catania, were hardly mentioned, and certainly not in a positive light. In general, all proposed preventive measures against mosquitoes were limited to advocating to raise the standard of living and educating the population in the malaria regions. The Italian system of malaria control, i.e. the combination of quinine distribution and drainage of swamps, received top marks, despite the criticism voiced by Lewis Hackett, Alberto Missiroli and others. Accordingly, the Malaria Commission’s report was very controversial from this side. [53]

The Malaria Report fell short of showing a unified strategy that would have incorporated the various competing methods and been supported by all stakeholders. Lewis Hackett reacted with extreme indignation in an open letter to the Malaria Commission. He interpreted the report as dividing research between “clinical malarialogists and hydraulic engineers”. He emphatically pointed out the plurality and local variation of problems and methods. He wrote: “If there were only one or two towns in Italy where it would be easier to eradicate the mosquito than to treat the people, then it would be the method of choice for these communities.” [54] The Dutch expert Nicolaas Hendrik Swellengrebel also stressed in a letter that “opinions are still too much divided to allow of clear judgement to be expressed.” [55] In particular, he pointed out that the Italian measures in the framework of the Grande Bonifica project would not necessarily lead to the eradication of malaria mosquitoes.

The fact that the Italian strategy to combat malaria had made a particularly strong impression on the members of the Malaria Commission was certainly in part due to the very targeted choreography of the study tour by the Italian authorities. The destinations in Italy that should have been visited at the very end of the European study tour were radically curtailed at the request of the Italian government. The study tour members stayed exclusively in northern Italy to look at Grande Bonifica projects, i.e. land reclamation projects by draining the marshes. The areas in southern Italy that were severely affected by malaria were left out of the program.

The same happend in 1925, when study tours were made exclusively to the Italian flagship projects (Pontine Marshes, Agro Romano and Po Valley) in the context of the Malaria Congress in Rome in October of the same year. Italian malaria researchers such as Alberto Missiroli and Alberto Lutrario even noted that the official Italian statistics were not particularly reliable and that the malaria sites visited during the first study tour and in the context of the Malaria Congress had been deliberately selected and prepared in advance. They urged the Malaria Commission to take a critical look at the figures and sites visited, as the Italian authorities and government were keen to demonstrate national success in dealing with one of Italy's worst diseases. Although the Malaria Commission had also taken an hour to watch a demonstration by Alberto Missiroli on Paris Green, they did not wait to see the results of the presentation. [56]

6 The Malaria Commission’s 1926 Study Tour to Sicily

Despite criticism of its judgments and approach, the Malaria Commission continued its study tours, organizing tours to Palestine and Syria in 1925 and Spain in 1926. A tour to Sicily was also undertaken from 28. September to 08. October 1926. In addition to Alberto Lutrario, Bernhard Nocht and Donato Ottolenghi, the experts Sydney Price James and Nicolaas Hendrik Swellengrebel, as well as Émile Marchoux (France), Claus Schilling (Germany) and M. Wenyon (Great Britain) also took part in the tour to Sicily as official representatives (not of the Malaria Commission, but the overarching League of Nations Health Commission). The journey took the study tour members from Palermo to Caltanisetta and the sulphur mines of Gallitano and Trabia, before continuing to Catania and the plain of Catania and finally to Syracuse. The Malaria Commission’s travel report on this study tour to Sicily emphasized how different the situations were even in individual regions: “Every day the country looked different, every day the territorial and social conditions changed. Each individual case requires a special description.” [57]

The planning and execution of the study tour to Sicily followed up on the previous tour to Italy. The tour members were either presented with the political successes in the health sector, as stressed in the opening lecture by Professor Luigi Manfredi in Palermo, or they visited flagship hydraulic engineering projects that were modern and not a source of malaria.

In Catania, which the study tour members reached on the seventh day, the picture was the same: a lecture was given by Professor Eugenio di Mattei on the natural and (agricultural) economic conditions that caused of the epidemic since 1917, and on the successful quinine strategy of the government and local authorities. Di Mattei’s comprehensive statistical material, which was meant to prove the successes in the fight against malaria, was made available to the study tour members in large numbers. [58]

The publicly staged lecture in the university’s Aula Magna, located directly in the heart of the city on the Via Etnea boulevard, was followed by an afternoon tour to the flagship farm, La Rotondella, in the plain of Catania, where the successful history of malaria control was demonstrated. The owner of the farm, Gabriello Carnazza, a former Sicilian minister, told the members of the tour about his experience in developing the previously almost unusable land on the edge of the Simeto River. He described the infrastructure that connected the farm with a road and electricity, among other things to pump water to the higher fields. Nevertheless, the farm struggled with malaria in the first year, as the workers sleeping in the open air or in tents were infected and could not work. Only the quinine treatment and better accommodation were able to defeat the malaria and allow a hundred workers to live and work in the malaria-prone region in good health. Although the international experts found “larvae of Anopheles and a large amount of Culex larvae in two dip samples in an irrigation canal near the houses,” the locals there were healthy. In the study tour report, which was written by Émile Marchoux, the verdict on the local project was positive: “It was therefore sufficient to develop the land here in order to drive out malaria.” [59]

Itinerary of the Malaria Commission’s Study Tour to Sicily.

The following day, the study tour members visited the field laboratory of the Rockefeller Foundation in San Guiseppe la Rena as well as the adjoining treatment center of the municipal health department against malaria, to which, among other things, the quinine allocation was entrusted. The treatment center had a service area of 23,000 hectares (at risk of malaria), compared to 900 hectares for the field laboratory. Distributors dispensed quinine in several sectors and tracked down and treated sick people if necessary.

Map of San Guiseppe La Rena.

The study tour report shows a great bias: while the study tour members thoroughly examined and documented the work conducted at the field laboratory, they maintained a critical distance from the approach taken there. The relevant passages in the report sound distanced and matter-of-fact, and no success in the fight against malaria is attested to the Rockefeller Foundation’s work. The passages on the work of the municipal treatment center, on the other hand, were extremely positive. Based on the Italian malaria strategies, the center was presented by Marchoux as a local model of success: an area where “the children and often the adults were pale, anemic, with enlarged spleens and sickly” and “the agricultural workers could only work to a limited extent”, had become an area where “the population is active, the children are robust and the malaria is harmless” thanks to the quinine treatment. “The soil is worked regularly and even with zeal.” [60]

In its general conclusions, the study tour report confirmed the position that had already been set out in the general Malaria Report of 1925. It also supported the policy of the Italian government in dealing with a serious health and economic problem in Italy. The travel report highly praised the measures taken, emphasizing that their success depended solely on correct local implementation. Rather uncritically, the report concluded that the successes in the fight against malaria “are undoubtedly due to the remarkable Italian health organization, the vigilance of the Directorate General for Public Health, the forward-looking laws that have been enacted and, above all, the many and dedicated staff entrusted with the implementation of these measures.” [61] The centralization of tasks and responsibilities by the Italian government was praised as “one of the wisest measures”, as it allowed “better use of public resources and thus produce the maximum of useful work with the minimum of means.” [62]

What the report on the study tour to Sicily lacks is a critical reflection on the work done by the group members themself, the regions visited and examined, and the one-sided focus on dealing with malaria consequences. The resurgence of high infection and death rates after the First World War should have prompted a more critical approach to a strategy (quinine treatment and prophylaxis) that treated the symptoms without tackling the causes. The report pointed out that many measures had not been implemented in Sicily, partly because the Grande Bonifica projects did not cover the island.

The report here included requests by practitioners on the ground, who called for a critical examination of local realities, for greater involvement of the central government in water management, and more consistent implementation of existing laws by local authorities. Both Luigi Manfredi in Palermo and Eugenio di Mattei in Catania were quoted as advocating a reforestation program to improve water management, increase economic production and defeat malaria. In addition, there was clear criticism of the Sicilian population’s handling of the causes of malaria, which was explained by a lack of education and “numerous private and illegal initiatives, particularly concerning the management of water-flows and retention ponds.” [63]

7 The impact of the Study Tour to Sicily on the Malaria Commission and International Scientific Cooperation

The second general Malaria Report of the Malaria Commission came out in 1927. It had been authored by the same editorial team as the 1925 general report and did not introduce any substantial changes in direction. Instead, it reflected a slight shift in justification and focus – moving away from preventive measures through quinine administration and toward the treatment of those affected, along with related research on malaria drugs and their distribution. [64] The rejection of mosquito larvae control as a prophylactic measure, such as spraying Paris Green, was very clear; it was dismissed as ineffective and too expensive by the second general Malaria Report. [65] The study tours across Europe and the investigation of the control methods demonstrated in Italy provided the basis for a verdict by the Malaria Commission, which was welcomed by those members of the Commission who had already given a positive assessment of the first general Malaria Report. [66]

The already deep divisions in the international scientific community over the right way to fight malaria were further intensified by the second general Malaria Report. In particular, the report brought on a break between the Malaria Commission and the Rockefeller Foundation. While the Foundation had generously supported the Malaria Commission financially because it wanted to promote its proclaimed goal of developing a comprehensive anti-malaria strategy, it now withdrew from the Malaria Commission. Rockefeller halved its financial support from 1927 onwards, which meant that the Malaria Commission’s program was also halved, including the expensive study tours. [67] There is strong evidence to suggest that this shift was influenced by the two general reports of the Malaria Commission, which primarily advocated the medical treatment of infected people (with quinine) and was openly skeptical or even hostile to the approach to fight the carriers as investigated and propagated by the Rockefeller Foundation. [68]

As the malaria pandemic in Europe came to an end in the second half of the 1920s and the number of malaria deaths stabilized at a low level, the Malaria Commission’s work was reoriented. On the one hand, it changed its internal structure and work priorities by assigning three thematic focus areas to individual working groups: [69] methods of malaria control; epidemiology of malaria; and the use of quinine. This was in response to the fact that it had not been possible to combine the different approaches to malaria control. On the other hand, there was a geographical shift of focus from Europe to the rest of the world, especially to the malaria regions of Asia and Africa, where the colonial medical departments of many European countries were active. [70]

In addition to the changes in the Malaria Commission of the League of Nations, the cooperation of the Italian government and local authorities with the Rockefeller Foundation also changed significantly. With the decline in malaria deaths, the successful land reclamation programs and the positive assessment by the Malaria Commission, the Italian government sought to continue to exploit its Grande Beneficia program for propaganda purposes. Critical voices and alternative approaches were not welcome, [71] so that conflicts with the Rockefeller Foundation became more numerous until it withdrew completely from Italy in 1934. [72]

In Sicily and Catania, a new phase in the fight against malaria began at the end of the 1920s, when quinine prophylaxis was supplemented by small-scale drainage measures. In Caltanisetta, a center was set up to produce Paris Green to meet the needs of the entire island. In the municipalities concerned, teams of mosquito fighters were formed, usually consisting of two or more people, to take action in creating water drainage canals and to eliminate stagnant water, to control mosquitos with Paris Green, to destroy larvae by fumigation, other insecticidal liquids or trapping with special equipment. As late as 1938, a campaign was launched throughout the island and an information leaflet entitled Brief elements of the fight against malaria was distributed in schools, outlining long-known measures against malaria, its modes of transmission, its potential for health and economic damage, its prevention and treatment and the fight against mosquitoes. Although the number of malaria deaths declined throughout Sicily, neither the disease nor its causes were to disappear completely, and malaria returned during the turmoil of the Second World War. [73]

8 Conclusion

“Lentini, Francofonte, and Paternò struggle in vain to climb the first hills rising from the plain, wrapping themselves in orange groves, vineyards, and evergreen gardens – but malaria clings to the inhabitants, haunting the depopulated streets, forcing them from their sun-scorched homes, shivering with fever beneath their coats, burdened by all their bedding draped over their shoulders.” [74]

What Giovanni Verga described in the second half of the 19th century in his novella about malaria were the villages Lentini, Fracofonte and Paterno “climbing hills” in a kind of maimed state due to the lack of infrastructure and socioeconomic consequences of malaria and the desperate attempts to combat it in the area around Catania. It is a landscape in which the contrast between the fertility of the land and the illness and death of the people from malaria becomes tangible. Malaria has left its mark not only on the people, but also on the landscape. Cultural and natural imprints linked to the history of malaria have become deeply engraved in the land and its people. The painful relationship between land and farmer is, so to speak, etched into the modified landscape, a result of processes that go back many centuries.

The analysis of international scientific malaria collaborations provides an insight into the strategic political and economic initiatives, mechanisms and interests that have shaped this pained landscape at the interface of local and global strategies for malaria control, whose successes and long-term effects, however, require critical evaluation.

The League of Nations Malaria Commission and the Rockefeller Foundation went to great lengths to study malaria in Europe between 1924 and 1927, conducting practical research on the ground and organizing intensive study tours in order to understand the many local variations of the disease and its causes. They supported international collaboration of scientists from different countries, which allowed knowledge to be generated and circulated. In particular, the study tours of the Malaria Commission were central events of collaboration, which were important in the context of the malaria pandemic in Europe.

However, the impact of these efforts on local malaria strategies depended on their acceptance by local decision-makers. Measuring success remains challenging, in part because knowledge was disseminated and adapted through various channels. Ultimately, the Malaria Commission failed to develop a unified approach that would have effectively integrated the diverse methods and strategies for combating malaria. This can be seen, for example, in the clear priority given to quinine treatment and economic development measures as methods of malaria control that were a pragmatic solution in the short term. The Rockefeller Foundation’s intensive research in Italy, for example in Catania, aimed at combating malaria by targeting mosquito larvae rather than solely relying on quinine treatment. This approach, which sought to address the root causes of the disease, was met with resistance from the Malaria Commission and tended to create tensions within the international scientific community. However, as malaria-related deaths in Europe declined by the mid-1920s, these conflicts gradually shifted focus and were no longer centered on Italy or Catania.

The Italian methods were declared as the flagship strategy by the Malaria Commission due to the decline in malaria deaths, although causal relationships remained unclear: In this context, a close look at the malaria situation in Catania in Sicily also revealed that the Italian government and its health authorities went to great lengths to make Italy appear as an international paragon of malaria control and to celebrate fascism for its progressiveness and success in eradicating the disease.

However, there were doubts about the statistics presented and the staged demonstration of showcase projects for the Malaria Commission. The example of Catania shows that elementary problem areas such as the notoriously poor sewage systems, the population’s lack of knowledge in dealing with malaria (education) or the skepticism with which the population met the official authorities, were not addressed or taken into account by the Malaria Commission.

In summary, the integration of local and international perspectives was a major challenge. Malaria varied greatly in its forms and causes, depending on the local context, making targeted local measures more effective than broad-based international comparative approaches. Combating a disease like malaria primarily required local strategies, not an international framework that applied equally to all. The Malaria Commission tried to summarize the various regional problems and control strategies across Europe in order to make general assessments and recommendations. However, it did not manage to translate its findings into concrete influence on local policy: at least in the case of Catania, as was examined here, the impact of the Malaria Commission’s studies remained limited.

About the authors

Lene Faust is an associate researcher at the Institute of Social Anthropology, University of Bern. She obtained her PhD from the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg in 2019. Her main research areas include political anthropology and the anthropology of the Mediterranean. Currently, she specializes in studying the transformation of Mediterranean societies with a particular focus on Sicily.

Christian Franke teaches economic history/pluralistic economics at the Faculty of Economics at the University of Siegen. He obtained his PhD in 2005 from the University of Siegen, where he also completed his habilitation in 2010. His research focuses on the history of international economic relations, European integration, and infrastructure regulation.

© 2025 Lene Faust/Christian Franke, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Obituary for Eckart Schremmer

- Special Issue Articles

- Epidemics and Pandemics in Economic-historical Perspective – An Introduction

- Cholera in the City of Poznań: Did the Death Toll of the 1866 Cholera Epidemic Reflect Social and Economic Differences?

- The Mortality Impact of Cholera in Germany

- When Diseases Return from the Epidemiological Honeymoon: The Reemergence of Smallpox in 19th Century Germany and its Lessons for Public Health Policies after COVID-19

- On the Economic Costs of the Spanish Flu Pandemic in Germany: An attempt at Assessing GNP Lost for 1918

- Malaria in Catania/Sicily: Local Manifestations and International Scientific Cooperation During a Pandemic in the 1920s

- Geographical Aspects of Diphtheria in England and Wales: Immunisation and the Spatial Sequence of Retreat to Effective Elimination, 1921 to 1964

- Pandonomics: Why Economics was Unprepared for COVID-19-Policies

- Research Forum

- “Stupid” German Money? Bonus Interest Rate Payments on Savings Deposits During the Stagflation of 1967 to 1984

- Geography and Space in Recent Economic History

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Obituary for Eckart Schremmer

- Special Issue Articles

- Epidemics and Pandemics in Economic-historical Perspective – An Introduction

- Cholera in the City of Poznań: Did the Death Toll of the 1866 Cholera Epidemic Reflect Social and Economic Differences?

- The Mortality Impact of Cholera in Germany

- When Diseases Return from the Epidemiological Honeymoon: The Reemergence of Smallpox in 19th Century Germany and its Lessons for Public Health Policies after COVID-19

- On the Economic Costs of the Spanish Flu Pandemic in Germany: An attempt at Assessing GNP Lost for 1918

- Malaria in Catania/Sicily: Local Manifestations and International Scientific Cooperation During a Pandemic in the 1920s

- Geographical Aspects of Diphtheria in England and Wales: Immunisation and the Spatial Sequence of Retreat to Effective Elimination, 1921 to 1964

- Pandonomics: Why Economics was Unprepared for COVID-19-Policies

- Research Forum

- “Stupid” German Money? Bonus Interest Rate Payments on Savings Deposits During the Stagflation of 1967 to 1984

- Geography and Space in Recent Economic History