Abstract

This study examines subsequent head coach opportunities for former National Football League (NFL) head coaches. Under a subsequent CEO career framework, survival analysis is used to examine the effects of race and market characteristics on subsequent NFL head coach opportunities for former head coaches. Observations of former head coaches who neither ended their coaching careers nor possess head coach positions in the observed seasons are used (n = 1,132). Black former NFL head coaches are less likely to secure subsequent NFL head coaching opportunities if their most recent coaching position was in a large media market. However, both Black and non-Black former head coaches who most recently coached in highly segregated metropolitan areas experienced higher likelihoods of securing subsequent head coaching opportunities. This segregated market effect is even stronger for Black former head coaches. The NFL can utilize this information in policy formation decisions regarding hiring policies and practices. Teams and their lead executives can also use this information to identify any personal biases that may arise within the head coach labor market. Coaches may use the information to best position themselves for subsequent career opportunities.

The National Football League (NFL) is the most popular sport in the United States as evidenced by its television ratings and attendance numbers (Das 2020). Since its formation in the early 1920s, the NFL has also grown to be the most valuable American sports league. NFL teams generate average yearly revenues of nearly 600 million USD, with franchise values averaging approximately 5 billion USD (Ozanian and Teitelbaum 2023). Additionally, teams equally share nearly two-thirds of all league-generated revenue (Ehrlich et al. 2021). In addition to its popularity in the United States, the NFL has greatly increased its global presence (Gems and Pfister 2019). NFL games are regularly held in England and Germany, with future schedules expanding into Brazil and Spain (Dajani 2024). The NFL’s popularity leads fans, front office personnel, and owners to carefully criticize and evaluate the performance of head coaches.

Rose (2016) evidenced an average of six to seven yearly NFL head coach turnovers, which team supporters generally view as an immediate solution to their team’s problems. Using 2005 to 2015 NFL head coaching data, Rose found that 65 % of new hires (49/75) were fired after less than three seasons. The abundance of head coach turnover in the NFL on the Monday after the regular NFL season ends has come to be known as “Black Monday” because it usually marks the firings of coaches and team executives whose teams did not make the playoffs (Cosgrove 2019).

In addition to the attention paid to the number of head coaches that are hired/fired each year, a significant amount of media attention has often focused on the race of the hired/fired head coaches (Henry and Oates 2020). The 2020 Racial and Gender Report Card for the NFL stated that 57.5 % of NFL players were Black, 30.5 % of assistant coaches were Black, and 9.4 % of head coaches were Black (TIDES 2020). This progressive decline from those playing in the NFL to those coaching in the NFL led Troy Vincent, Executive Vice President of Football Operations for the NFL, to suggest that the NFL’s head coach hiring system is broken for minority candidates (King 2020). The NFL has 32 teams but only five minority head coaches and five minority general managers following the 2020 season (Laine 2021). Of note, Brooks et al. (2019) reported that over a third of NFL teams have never hired a permanent minority head coach and no team has ever hired consecutive coaches from underrepresented minority backgrounds.

To address the underrepresentation of minority head coaches, the NFL introduced the Rooney Rule in 2003. The Rooney Rule required teams to interview at least one ethnic-minority candidate when they had a head coaching vacancy (Graziano 2020). Recently, NFL team owners approved new modifications to the Rooney Rule. For example, teams must conduct interviews with at least two candidates from underrepresented minority groups for any head coach vacancy (Graziano 2020). This modification aims to provide minority coaches with more opportunities to interview for coaching jobs, which will help both first-time coaches and those who are looking for a subsequent NFL head coach position.

In anticipation of more Black former head coaches potentially having subsequent opportunities, the purpose of this paper is to examine the extent to which Black former head coaches have received subsequent head coaching opportunities. Further, this project has interest in determining how those opportunities differ from non-Black former head coaches and the extent that the market size and segregation levels of their previous team’s metropolitan area may influence their prospects for becoming a head coach again. This examination is both necessary and timely as former Black head coaches may find themselves with increased interview opportunities and future Black head coaches may want to understand what their re-hire prospects may be if they fail in their first head-coaching role.

1 Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

Because of their many similarities, NFL head coaches have been used to develop chief executive officer (CEO) theory for decades (e.g. Brown 1982; Fredrickson, Hambrick, and Baumrin 1988; Keidel 1987; Ndofor et al. 2009). CEO theory has also been applied to research investigating American football phenomena (e.g. Foreman, Soebbing, and Seifried 2019; Soebbing and Washington 2011). More specifically, football data have been used to examine several possible career outcomes (e.g. promotion, dismissal) of these organizational leaders (e.g. Maxcy 2013; Salaga and Juravich 2020). A relatively under-researched career outcome of CEOs and sport head coaches is the opportunity to secure subsequent top leadership positions.

In their framework for understanding subsequent CEO opportunities for ousted CEOs, Ward, Sonnenfeld, and Kimberly (1995) presented several factors related to these subsequent career outcomes. Specifically, they explained how several factors such as the CEO’s compensation, reason for the CEO’s departure, demographic factors, and media coverage affect whether former CEOs are viewed as hirable for future CEO positions. Our framework subsequently follows, in which we discuss how executive compensation, CEO departure, and career outcomes relate to our context of the NFL head coach labor market. We then develop our hypotheses related to future career outcomes based on race, media market size, and segregation.

1.1 CEO Compensation

Due to high levels of compensation and generous exit packages, CEOs generally do not reenter the executive labor market (Ward, Sonnenfeld, and Kimberly 1995). While this phenomenon has not been examined in the NFL due to the lack of consistent and accessible NFL coach salary data, it can be seen following many football coach dismissals anecdotally. Publicly available information from college football highlights the phenomenon of head football coaches receiving large payouts prior to the typical retirement age. For example, Gus Malzahn was owed $21.5 million after his dismissal from Auburn University at age 55 and Kevin Sumlin received $7.3 million when he left the University of Arizona at age 56 (Kirk 2020).

1.2 Causes of Departures

Ward, Sonnenfeld, and Kimberly (1995) described several causes that could result in CEO departures, including performance issues, improper behavior, disagreements, and personality clashes. They reasoned that CEOs who departed firms due to the aforementioned reasons might be identified as damaged goods. CEOs that have been given that label are often viewed as unhirable for future CEO positions. Similarly, NFL head coaches are evaluated and experience adverse career outcomes following instances of poor performance and improper behavior (Foreman, Soebbing, and Seifried 2019). Disagreements and personality clashes can also influence career outcomes for NFL head coaches, especially with conflicts likely to occur due to cultural misunderstandings in the increasingly diverse NFL (Nelson and Quick 2017).

1.3 Demographics and Career Outcomes

Common demographics used for examining NFL head coaches are age and race (e.g. Salaga and Juravich 2020; Solow, Solow, and Walker 2011). Ward, Sonnenfeld, and Kimberly (1995) stated that age is an important factor in former CEOs securing subsequent CEO opportunities. Older CEOs are less likely than younger former CEOs to obtain other active executive positions. However, older CEOs were more likely than younger CEOs to be offered advisory role positions. Also of importance, Ward, Sonnenfeld, and Kimberly (1995) shared that older CEOs are less likely to take on fresh or new challenges and that organizations might be hesitant about hiring an older CEO to replace a departing one. This type of move would likely lead to another quick succession due to the incoming CEOs age.

While Ward, Sonnenfeld, and Kimberly (1995) did not explicitly discuss racial factors in subsequent CEO opportunities, they commented on the existence of an ‘inner circle,’ stating, “The idea is that there is a fairly well defined and relatively closed network or community of CEOs and directors who serve on interlocking boards and who look after their own by helping to find other directorships or positions for fellow elites ousted by an organization” (p. 126). Relatedly, the NFL is known to operate in a relatively closed network of mostly White men who operate as NFL owners, general managers, and head coaches (Collins 2007; Foreman et al. 2018; Foreman Bendickson, and Cowden 2021; TIDES 2020). Therefore, cognitive biases and access limitations to the network or ‘inner circle’ of NFL decision makers may prevent underrepresented coaches from securing head coach opportunities.

1.4 Racial Disparities in NFL Coach Career Opportunities

Brooks et al. (2019) noted that Black head coaches tend to be hired at older ages, have more relevant playing experience, and do not receive equivalent subsequent opportunities. Regarding age, they reported that newly hired White head coaches were 48.4 years old, compared to 51.2 for coaches of color – a difference of almost three years. Notably, among the 14 head coaches under the age of 40 who were hired over the past decade, only two (14.3 %) were coaches of color.

Regarding relevant coaching experience, Brooks et al. (2019) stated that former NFL offensive coordinators were most frequently hired as NFL head coaches. Other common past coaching positions included NFL defensive coordinator and NFL head coach of an alternative club. Almost two-fifths of head coaches hired since 2009 left offensive coordinator positions and a little less than one-third of head coaches hired left other head coaching roles. Interestingly, even though offensive coordinators and current NFL head coaches represent the two largest pools from which new head coach hires are found, half (i.e. 6 of 12) of the newly hired coaches of color occupied the defensive coordinator position prior to becoming a head coach.

Regarding subsequent NFL head coach opportunities, Brooks et al. (2019) presented descriptive statistics showing that Black former head coaches experienced more difficulty obtaining subsequent NFL head coach positions, compared to White former head coaches. Specifically, they stated:

The next coaching positions for outgoing head coaches of color were less varied compared to outgoing white head coaches. Outgoing head coaches of color most often became NFL defensive coordinators (36 %). Outgoing white head coaches most often became NFL defensive coordinators (22 %), NFL offensive coordinators (21 %), or head coaches of other NFL clubs (14 %). Exiting white head coaches were hired for other NFL head coaching positions at twice the rate of coaches of color (14.3 % vs. 7.1 %). They also went on to offensive coordinator positions in the NFL at nearly three times the rate of coaches of color (20.6 % vs. 7.1 %) (Brooks et al. 2019, p. 24).

Those results clearly demonstrate Black coaches struggle to return to the head coaching pipeline positions. However, these descriptive statistics did not control for the quantity or quality of coaching experiences. Building upon the descriptive statistics presented by Brooks et al. (2019), Foreman, Bendickson, and Cowden (2021) found that Black coaches were about 38 % more likely to secure subsequent head coach opportunities in the NFL than their non-Black counterparts. Given these mixed results, we present the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1:

Black former head coaches secure future head coach positions at a different rate than their non-Black former head coach peers.

1.5 Publicity and Market Size

While boards of directors are responsible for appointing CEOs in corporate settings, in the NFL, head coaches are appointed by team owners or general managers. However, personnel decisions made by both boards of directors and NFL team owners and general managers are susceptible to biases and may be based on limited information sets (Collins 2007; Fredrickson, Hambrick, and Baumrin 1988; Foreman, Bendickson, and Cowden 2021). In addition to individual cognitive biases that plague personnel decisions, team owners and general managers are often swayed by public opinion, whether that be (a) to appease stakeholders (e.g. fans and sponsors) or (b) because information sets are often include external evaluations (e.g. from the public, media, and analysts). For example, amid mounting, or even pending, pressure from the public, reluctant team decision-makers have changed their racist mascot names and logos (Ospina 2024), suspended their own players (Foreman, Soebbing, and Seifried 2019), or even hired or fired their head coaches (Hambrick, Bass, and Schaeperkoetter 2014; Flores, Forrest, and de Dios Tena 2012). Similarly, team decision-makers have been known to make suboptimal decisions based on limited information sets that have been largely influenced by the public, such as fans, media and social media, analysts (Bursik 2012; Foreman, Bendickson, and Cowden 2021; Romer 2006). Therefore, public perceptions of NFL head coach candidates can affect team owners’ and general managers’ hiring decisions, whether based on characteristics of the candidates themselves (e.g. race) or the public perceptions in the environments where the coaches previously coached.

The publicity surrounding an ousted CEO’s exit can help or harm their prospects of obtaining another executive role. As noted by Ward, Sonnenfeld, and Kimberly (1995), “For CEOs ousted for negative reasons, the publicity would only reinforce those negative perceptions … For those CEOs ousted for neutral exit reasons, however, the media exposure would help keep them visible to executive search firms” (p. 126). Therefore, for candidates who may be perceived more negatively by the public, whether due to race, performance, or other issues, more publicity could hinder future employment opportunities, whereas candidates perceived more neutrally, for the same reasons of race, performance, etc., may benefit from enhanced media exposure, aiding them in securing future employment.

Similar statements have been made about the importance of retaining media exposure to remain visible in the NFL (Collins 2007), especially since the NFL is a relatively closed network of predominantly White decision-makers. Therefore, we believe that the NFL team’s media market size has been a neglected factor for analysis in discussing the current underrepresentation of Black coaches. Where most studies have analyzed the underrepresentation of Black coaches as a labor market problem (Bozeman and Fay 2013; Braddock, Smith, and Dawkins 2012; Madden 2004), emphasis should be placed on the impact the media market plays in influencing the hiring of Black coaches.

Cunningham and Bopp (2010) discussed how media and press releases for new college football head coaching hires helped to perpetuate the belief that Whites were better at game planning and understanding the strategy of football than Blacks, and Blacks were better recruiters and more relatable for players. Highlighting the coaching ability of Whites, while downplaying it for Blacks, they argued helps to reinforce harmful racial ideologies about Black men in leadership. Considering the role the media plays in covering the hiring of Black coaches in the NFL, combined with an understanding that larger markets are likely to have more news outlets and more widespread coverage of coaches within that market that may have more substantive and negative effects on Black coaches, we offer the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2a:

The market size for the most recent NFL city that former head coaches coached in positively influences the speed at which they secure subsequent NFL head coach positions.

Hypothesis 2b:

The market size for the most recent NFL city that Black former head coaches coached in negatively influences the speed at which they secure subsequent NFL head coach positions.

1.6 Market Segregation

Just as perceptions about potential head coaches may arise based on the size of a market that a coach most recently worked in, another market characteristic that may affect Black head coach appointments is the degree to which the most recent market was segregated. For head coaches who most recently coached in more segregated markets, perceptions from that media market may be biased based on the degree of segregation from that market. Segregation within the metropolitan may be detrimental to an underrepresented candidate because of bias and discrimination that is inherent in the structure of the city, especially as it may result in less familiarity with people of diverse backgrounds. However, more segregated cities (e.g. Chicago, Detroit, New York) may be more likely to neglect people of diverse backgrounds in comparison to less segregated markets (e.g. Minneapolis, Seattle).

Moreover, in the case of high-profile jobs like CEO or NFL head coach, underrepresented leaders may benefit from less attention (Dwivedi, Misangyi, and Joshi 2021; Smith, Chown, and Gaughan 2021). Furthermore, the structure of the media within the city, especially with the prevalence of social media, may reflect the segregated structure of the city itself, resulting in more diverse media outlets leading the coverage of Black coaches and portraying them more positively. Given these competing possibilities for majority and underrepresented candidates for head coach positions in the NFL, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3a:

The degree of segregation for the most recent NFL city that former head coaches coached in influences the speed at which they secure subsequent NFL head coach positions.

Hypothesis 3b:

The degree of segregation for the most recent NFL city that Black former head coaches coached in influences the speed at which they secure subsequent NFL head coach positions.

2 Methods

To examine the effects of race, market size, segregation, and other potential determinants of former NFL head coaches securing subsequent NFL head coach opportunities, we use data from the NFL during the 25-season sample period extending from the 1995–1996 season through the 2019–2020 season. A dichotomous dependent variable is used to indicate the season in which a former NFL head coach secures a subsequent NFL head coach position (NextJob). The dependent variable NextJob is coded with a value of ‘1’ if the former head coach secured another head coach position in an observed season and ‘0’ if the former head coach held a position other than NFL head coach.

Because former NFL head coaches can coach for several years without securing a subsequent opening, if they secure one at all, we use survival analysis with observations for episodes of former head coaches who have not ended their coaching careers and do not possess head coach positions in the observed seasons. Therefore, the dependent variable NextJob indicates a failure, in which a coaching episode ends with the outcome of a subsequent head coach position secured. Observations of former NFL head coaches who began an episode of underemployment, in which they were still in the labor market but not employed as an NFL head coach, that began prior to the sample period beginning in the 1995–1996 NFL season are left-censored. Observations of former NFL head coaches who continue to coach in non-NFL head coach positions through the end of the sample period are right-censored.

Due to the time-dependent nature of the independent variables required for analysis, episodes are separated into coach-season observations (Blossfeld, Golsch, and Rohwer 2009). Within the sample period, there are 192 former NFL head coach episodes spread across 1,132 coach-season observations. Among these observations, 27 episodes began prior to the sample period and are treated as left-censored observations whereas 82 episodes extend beyond the sample period and are treated as right-censored observations, which is a practice consistent with similar career duration hazard models in sport (e.g. Ducking, Groothuis, and Hill 2015; Groothuis and Hill 2004).

2.1 Independent Variables

To test the hypotheses, we use three independent variables and two interaction variables. We use a dichotomous race variable that is indicative of whether a former head coach is Black (Black). Observations associated with Black coaches are coded with the value of 1 and observations associated with non-Black coaches are coded with the value of 0. Classifications of former NFL head coaches as Black or not are consistent with reports of NFL head coach races found in the NFL Racial and Gender Report Cards (TIDES 2020). The Black variable is specifically used within the present study to examine Hypothesis 1, that Black former NFL head coaches do not secure future head coach openings at the same speed as their non-Black former head coach peers.

We use two variables to examine Hypotheses 2a and 2b, that market size reduces the time it takes for former NFL head coaches to secure subsequent head coaching positions (Hypothesis 2a) and that Black former NFL head coaches wait longer to secure subsequent NFL head coaching positions relative to non-Black former NFL head coaches, after having coached in a larger market. The two variables used to examine Hypotheses 2a and 2b are team market size (MarketSize) and an interaction variable between Black and MarketSize (Black × MarketSize). To measure the size of each market, we use the population of the metropolitan statistical area where the team is located (George 2007). To account for annual fluctuations in populations, MarketSize is standardized by year, so that the mean MarketSize for each year is 0 with a standard deviation of 1.

Similarly, we use two variables to examine Hypotheses 3a and 3b, that former NFL head coaches secure subsequent head coaching positions at a different speed based on the degree of segregation in the city they coached in (Hypothesis 3a), and that these differences are also based on race (Hypothesis 3b). The two variables used to examine Hypothesis 3 are the degree of segregation in the metropolitan area (Segregation) and an interaction variable between Black and Segregation (Black × Segregation). To measure the amount of segregation in the metropolitan area, we use the divergence score developed by the University of California’s Othering & Belonging Institute (see Othering & Belonging Institute 2022).

2.2 Control Variables

A former NFL head coach’s previous experience is accounted for in several ways. First, seven variables are used to measure the quantity of a former NFL head coach’s experience. The amount of previously held head coach positions a former NFL head coach had (NFLHCJobs), the average number of NFL seasons spent in NFL head coaching positions (AvgHCJobTenure), the number of NFL seasons spent as an NFL head coach (NFLHCExp), the number of NFL seasons spent as an NFL assistant head coach or offensive/defensive coordinator (NFLAHCExp), the number of NFL seasons spent as an NFL position coach (NFLPCExp), the number of NFL seasons spent as an NFL assistant coach at lower levels than position coaches (e.g. quality control coach or assistant position coach; NFLAPCExp), and the number of seasons spent as a football coach in other professional or college football leagues (NonNFLExp) are included in the model. Similarly, the positions last held by former NFL head coaches are also accounted for in the model using dichotomous variables coded with the value of 1 if the position was held in the previous season and 0 otherwise. These positions are NFL head coach (NFLHC), NFL assistant head coach or offensive/defensive coordinator (NFLAHC), NFL position coach (NFLPC), or head coach outside the NFL (NonNFLHC). In addition to the quantity of coaching experiences and the type of recent coaching experiences, we also include measures of overall career performance and recent performance as an NFL head coach. Former NFL head coaches’ career winning percentages as NFL head coaches (CarNFLWin%) and the percent of seasons a former NFL head coach won the conference championship and went to the Super Bowl (i.e. the number of conference championship wins divided by the number of NFL seasons as an NFL head coach; ConfChamp%) represent overall career performance as an NFL head coach. Recent performance as an NFL head coach is measured by the former NFL head coach’s winning percentage in their last season as an NFL head coach (LastNFLWin%). Lastly, the age of the former NFL head coach is included in the model (Age).

The proportional hazard model takes the following form:

where i indexes individual coaches and t indexes time in NFL seasons. The vector X it represents the vector of independent variables MarketSize and Segregation. The vector Z it represents the vector of control variables.

2.3 Estimation Issues

Proportional hazard model was estimated using various distributions, including exponential, generalized gamma, Gompertz, loglogistic, lognormal, and Weibull survival distributions. After examining the Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) yielded by each of these survival distributions, the Weibull distribution appeared to fit the data the best (see Frick and Wallbrecht 2012 for more information on survival models). Correlation coefficients among the independent variables did not exceed 0.8, as demonstrated in Table 2, indicating that multicollinearity is not likely a concern in this study (Hair et al. 2010). Robust standard errors were used to alleviate heteroskedasticity concerns.

3 Results

The descriptive statistics for the sample are presented in Table 1 and correlation coefficients are presented in Table 2. Within the sample, 5.3 % of the observations resulted in a subsequent head coaching position being secured. Table 3 presents the hazard ratios, coefficients, standard errors, and p-values associated with each of the independent and control variables in the survival analysis. The hazard ratios are estimates of the increased or decreased likelihood of securing a subsequent NFL head coaching opportunity following an episode relative to the baseline hazard rate of 1.000, with values greater than 1.000 indicating an increased likelihood of the event and values less than 1.000 indicating a decreased likelihood of the event occurring.

Descriptive statistics.

| Variable | Mean | Std. dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NextJob | 0.053 | 0.224 | 0 | 1 |

| Black | 0.102 | 0.303 | 0 | 1 |

| MarketSize | 0.027 | 1.053 | −0.990 | 3.595 |

| Segregation | 0.238 | 0.073 | 0.093 | 0.399 |

| NFLHC | 0.146 | 0.353 | 0 | 1 |

| NFLHCJobs | 1.283 | 0.541 | 1 | 4 |

| AvgHCJobTenure | 3.705 | 2.311 | 1 | 16.5 |

| NFLHCExp | 4.867 | 3.759 | 1 | 33 |

| NFLAHCExp | 6.050 | 5.128 | 0 | 29 |

| NFLPCExp | 5.730 | 4.324 | 0 | 23 |

| NFLAPCExp | 0.675 | 1.178 | 0 | 6 |

| NonNFLHCExp | 12.313 | 9.123 | 0 | 41 |

| NFLAHC | 0.333 | 0.472 | 0 | 1 |

| NFLPC | 0.140 | 0.348 | 0 | 1 |

| NonNFLHC | 0.191 | 0.393 | 0 | 1 |

| CarNFLHCWin% | 40.623 | 13.131 | 0.333 | 76.563 |

| ConfChamp% | 2.260 | 8.730 | 0 | 100 |

| LastNFLHCWin% | 32.567 | 14.979 | 0 | 87.5 |

| Age | 56.538 | 7.701 | 33 | 80 |

| N = 1,132 |

Correlation coefficients.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) | (15) | (16) | (17) | (18) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. NextJob | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Black | 0.0371 | |||||||||||||||||

| 3. MarketSize | 0.0195 | 0.0096 | ||||||||||||||||

| 4. Segregation | 0.0366 | −0.208*** | 0.287*** | |||||||||||||||

| 5. NFLHCJobs | −0.0143 | 0.098** | −0.028 | −0.101*** | ||||||||||||||

| 6. AvgHCJobTenure | 0.198*** | 0.0299 | −0.0006 | 0.056† | 0.092** | |||||||||||||

| 7. NFLHCExp | 0.129*** | 0.062* | −0.0055 | −0.0033 | 0.669*** | 0.763*** | ||||||||||||

| 8. NFLAHCExp | −0.0485 | −0.118*** | 0.0387 | −0.025 | 0.091** | −0.194*** | −0.115*** | |||||||||||

| 9. NFLPCExp | −0.0126 | 0.184*** | −0.052† | −0.180*** | −0.0429 | −0.146*** | −0.159*** | 0.229*** | ||||||||||

| 10. NFLAPCExp | −0.0418 | 0.0463 | −0.0211 | −0.122*** | −0.060* | −0.128*** | −0.148*** | 0.0367 | 0.0312 | |||||||||

| 11. NonNFLHCExp | −0.085** | −0.191*** | 0.149*** | 0.234*** | −0.202*** | −0.176*** | −0.235*** | −0.278*** | −0.314*** | −0.267*** | ||||||||

| 12. NFLHC | 0.103*** | 0.059* | −0.0101 | 0.0333 | 0.127*** | 0.198*** | 0.241*** | −0.158*** | −0.080** | −0.001 | −0.100*** | |||||||

| 13. NFLAHC | 0.0085 | −0.084** | −0.0041 | −0.0455 | −0.068* | −0.172*** | −0.173*** | 0.452*** | 0.070* | 0.128*** | −0.166*** | −0.292*** | ||||||

| 14. NFLPC | −0.084** | 0.098*** | −0.0101 | −0.143*** | −0.103*** | −0.088** | −0.127*** | 0.022 | 0.382*** | 0.058† | −0.100*** | −0.167*** | −0.286*** | |||||

| 15. NonNFLHC | −0.095** | −0.090** | 0.0333 | 0.186*** | −0.0418 | −0.049† | −0.070* | −0.286*** | −0.246*** | −0.162*** | 0.452*** | −0.201*** | −0.343*** | −0.196*** | ||||

| 16. CarNFLHCWin% | 0.177*** | 0.124*** | 0.0083 | −0.0014 | 0.264*** | 0.512*** | 0.515*** | −0.180*** | −0.114*** | −0.066* | −0.055† | 0.175*** | −0.173*** | −0.092*** | 0.108*** | |||

| 17. ConfChamp% | 0.099*** | −0.042 | 0.074* | 0.0171 | −0.0274 | 0.227*** | 0.161*** | −0.058* | −0.138*** | −0.068* | 0.054† | 0.092** | −0.048 | −0.052† | −0.0356 | 0.292*** | ||

| 18. LastNFLHCWin% | 0.167*** | 0.049† | −0.054† | −0.141*** | 0.155*** | 0.199*** | 0.255*** | −0.139*** | −0.0326 | 0.0355 | −0.141*** | 0.090** | −0.139*** | −0.0149 | −0.015 | 0.594*** | 0.147*** | |

| 19. Age | −0.089** | −0.0399 | 0.104*** | 0.116*** | 0.196*** | 0.082** | 0.176*** | 0.353*** | 0.310*** | −0.284*** | 0.315*** | −0.186*** | −0.053† | 0.051† | 0.123*** | 0.0421 | 0.0031 | −0.120*** |

-

Note. †p < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, two-tailed tests.

Survival analysis results.

| Variable | Haz. ratio | Coef. | Std. err. | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black (H1) | 0.799 | −0.225 | 0.313 | 0.473 |

| MarketSize (H2a) | 1.025 | 0.024 | 0.027 | 0.368 |

| Black × MarketSize (H2b) | 0.664 | −0.409 | 0.106 | <0.001 |

| Segregation (H3a) | 11.525 | 2.445 | 0.535 | <0.001 |

| Black × Segregation (H3b) | 18.529 | 2.919 | 1.407 | 0.038 |

| NFLHCJobs | 2.254 | 0.813 | 0.169 | < 0.001 |

| AvgHCJobTenure | 1.090 | 0.086 | 0.040 | 0.032 |

| NFLHCExp | 0.989 | −0.011 | 0.033 | 0.744 |

| NFLAHCExp | 0.952 | −0.049 | 0.011 | < 0.001 |

| NFLPCExp | 1.034 | 0.033 | 0.011 | 0.004 |

| NFLAPCExp | 0.998 | −0.002 | 0.034 | 0.961 |

| NonNFLHCExp | 1.029 | 0.028 | 0.007 | < 0.001 |

| NFLHC | 56.852 | 4.040 | 0.158 | < 0.001 |

| NFLAHC | 1.861 | 0.621 | 0.128 | < 0.001 |

| NFLPC | 1.042 | 0.041 | 0.122 | 0.736 |

| NonNFLHC | 0.723 | −0.324 | 0.117 | 0.006 |

| CarNFLHCWin% | 1.022 | 0.021 | 0.004 | < 0.001 |

| ConfChamp% | 0.996 | −0.004 | 0.004 | 0.320 |

| LastNFLHCWin% | 0.992 | −0.008 | 0.003 | 0.002 |

| Age | 0.894 | −0.112 | 0.010 | < 0.001 |

| Constant | 0.231 | −1.465 | 0.424 | 0.001 |

| ln p | 0.849 | 0.022 | ||

| p | 2.337 | 0.051 | ||

| 1/p | 0.428 | 0.009 |

-

Note. In the lower rows of the table above, p denotes the shape parameter. In the far right column, two-tailed p-values are presented for all variables.

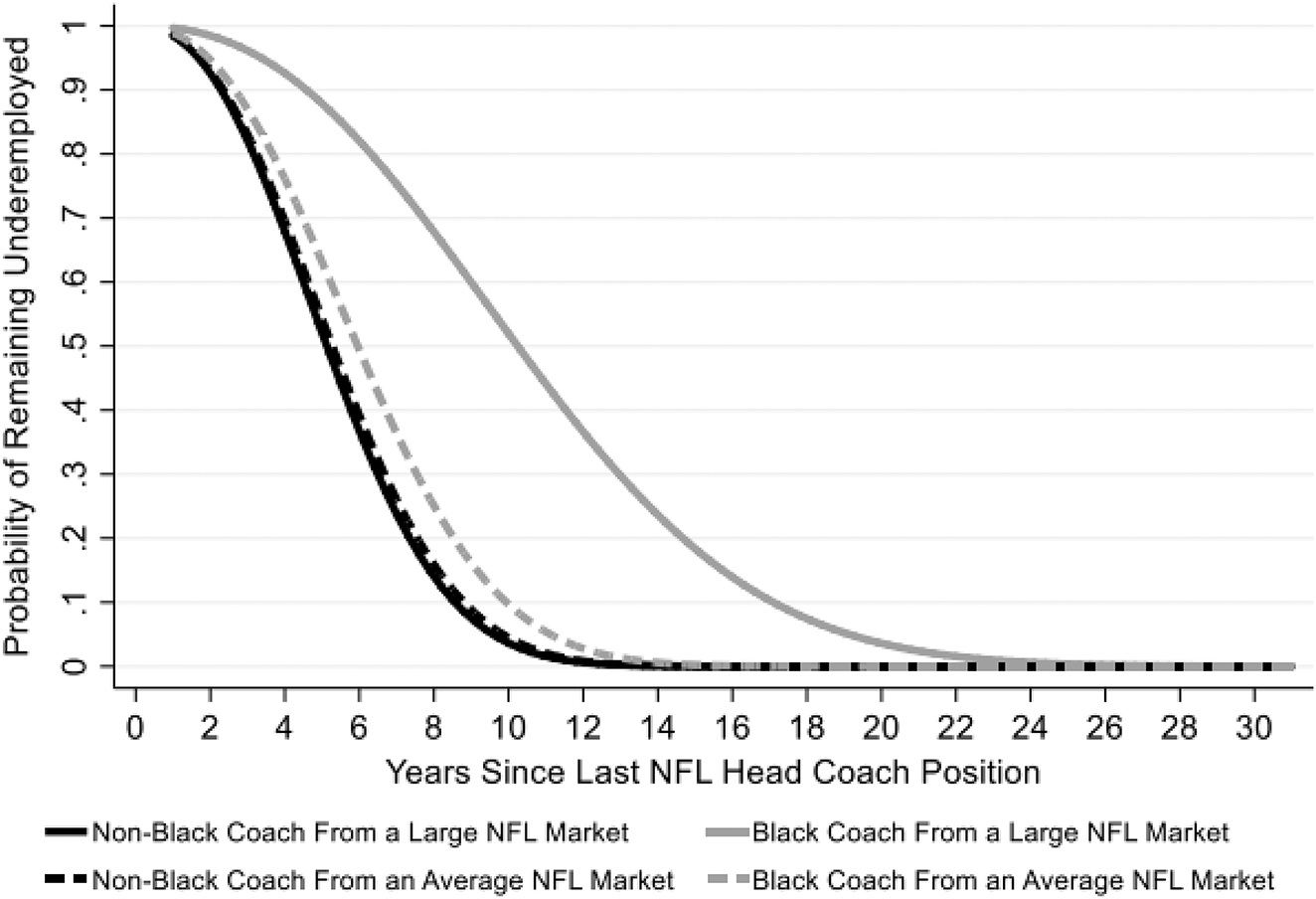

The variable Black, used to examine Hypothesis 1, has a two-tailed p-value above 0.05 (p = 0.473), and is, therefore, not statistically significant, indicating no support for Hypothesis 1. The variable MarketSize, used to examine Hypothesis 2a, has a one-tailed p-value above 0.05 (p = 0.184), and is, therefore, not statistically significant, indicating no support for Hypothesis 2a. The Black × MarketSize variable is statistically significant at the 0.05 significance level with a two-tailed p-value less than 0.001. Thus, Hypothesis 2b is supported. Figure 1 graphically depicts the differences in predicted likelihoods of former NFL head coaches securing subsequent NFL head coach positions, based on race and market sizes of teams. More specifically, Figure 1 shows the estimated likelihood of securing subsequent NFL head coach positions for four categories of former NFL head coaches (i.e. non-Black former NFL head coaches from a large NFL market, Black former NFL head coaches from a large NFL market, non-Black former NFL head coaches from an average size NFL market, and Black former NFL head coaches from an average size NFL market), ceteris paribus. Estimates in Figure 1 are based on a mean MarketSize (i.e. MarketSize = 0) for the average size market and large markets are based on three standard deviations above the mean (i.e. MarketSize = 3). As Figure 1 shows, Black former NFL head coaches are substantially disadvantaged after coaching in a large NFL market.

Probability of remaining underemployed by race, size of the metropolitan area the coach most recently coached in, and years since the coach last held a head coach position.

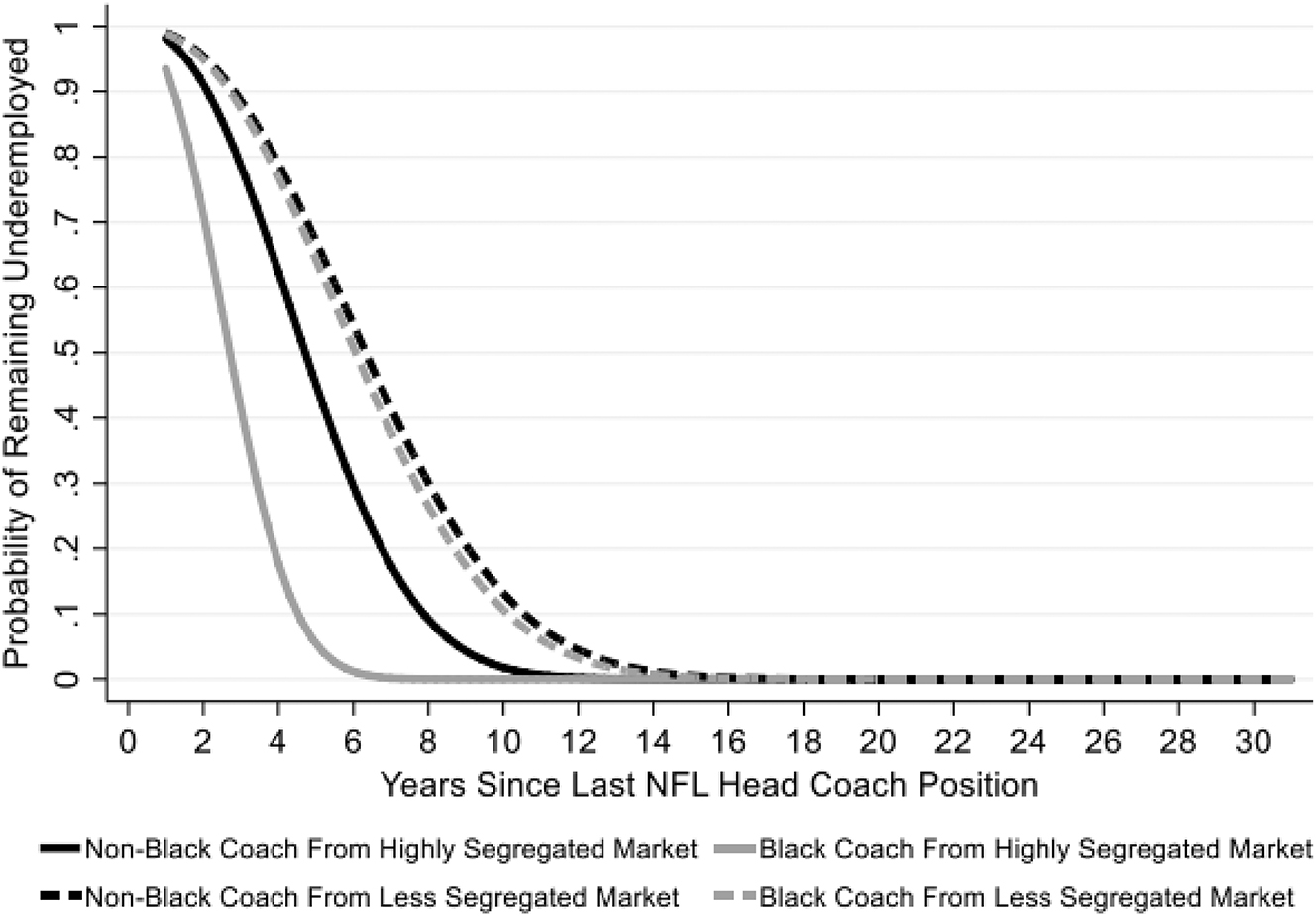

The variables Segregation and Black × Segregation are both statistically significant at the 0.05 significance level with two-tailed p-values of <0.001 and 0.038, respectively. As demonstrated in Figure 2, Black former head coaches from highly segregated markets are the most likely to secure a subsequent head coach position, followed by non-Black former head coaches from highly segregated markets. Therefore, Hypotheses 3a and 3b are supported.

Probability of remaining underemployed by race, segregation level of the area that the coach most recently coached in, and years since the coach last held a head coach position.

Other findings of interest that were not related to hypotheses presented in the present study pertain to variables for (a) number of NFL head coach positions held by former NFL head coaches, (b) average time spent in those past NFL head coach positions, (c) years spent as an assistant head coach or position coach, (d) career winning percentage and most recent season winning percentage as NFL head coaches, and (e) the age of the former NFL head coaches. As indicated by the NFLHCJobs variable, the more NFL head coach jobs a former NFL head coach held, the more likely they are to secure future positions. Similarly, the longer the former NFL head coach held those previous jobs, the more likely the former NFL head coach will secure a subsequent NFL head coach position. While the two measures of career NFL head coach performance had positive coefficients, indicating that better performance as an NFL head coach results in a higher likelihood of securing a subsequent head coaching position, the measure of recent NFL head coach performance had a negative coefficient and was statistically significant (p = 0.002). Lastly, the Age variable indicates that older former NFL head coaches are less likely to secure subsequent NFL head coaching opportunities.

4 Discussion

Consistent with previous research regarding racial discrimination in the NFL coach labor market (e.g. Braddock, Smith, and Dawkins 2012; Foreman et al. 2018), Black former NFL head coaches were reported to be less likely to secure subsequent NFL head coaching opportunities (Brooks et al. 2019). However, this conclusion was based on an analysis of descriptive statistics, which did not account for other variables (e.g. experience or performance). The present study examined the time to securing a subsequent NFL head coach position using survival analysis and controlled for variables such as (a) most recent position held, (b) overall and recent success as an NFL head coach, (c) years of coaching experience at various levels, and (d) demographics.

Analyzing subsequent NFL head coaching opportunities for former NFL head coaches throughout a 25-season sample period, the results reveal practically and theoretically intriguing insights. Broadly, the findings show that race appears to be a factor in subsequent NFL head coaching opportunities. Moreover, the effect of race on subsequent NFL head coaching opportunities is also influenced by the most recent position held by the former NFL head coach and the market size of the team most recently coached. Therefore, race has its own effects as well as combined effects based on whether the former head coach was an assistant head coach the previous season and in what market the former head coach was most recently involved.

4.1 Market Size

Fredrickson, Hambrick, and Baumrin (1988) posited that larger groups are more likely to develop factions, and when those factions disagree, adverse decisions regarding the career advancements of organizational leaders can suffer. Therefore, when there are disagreements about a former NFL head coach’s ability to lead an organization, and some stakeholders may believe that Black individuals are ineffective leaders (see Rosette, Leonardelli, and Phillips 2008), Black former NFL head coaches may be less likely to secure subsequent NFL head coaching positions. Indeed, the results of the present study support this notion, with Black former NFL head coaches not experiencing the career advancement benefits of coaching in a larger NFL market that are experienced by their non-Black counterparts. Rather, the results of the present study indicate that the career advancement opportunities, in terms of securing subsequent NFL head coaching opportunities, are diminished for Black former NFL head coaches whose most recent coaching position was in a larger media market. Descriptive statistical analyses outside of sport also provide additional support for our findings.

In a Brookings Institution report, Perry et al. (2022) evidenced that the highest representation of black-owned businesses was found amongst smaller metropolitan areas. For example, Black business owners and entrepreneurs in metropolitan areas such as Oxnard, California and Fayetteville, North Carolina had much higher levels of peer representation than the much larger regions of New York City and Atlanta.

4.2 Segregation

More segregated metropolitan areas are more likely to produce future NFL head coaches who previously served as NFL head coaches. This relationship holds especially true for Black former NFL head coaches. Given the benefit for both Black and non-Black former NFL head coaches (and especially for Black former NFL head coaches), it is possible that the structure of the media within the city, especially with the prevalence of social media, may reflect the segregated structure of the city itself, resulting in more diverse media outlets leading the coverage of Black coaches and portraying them more positively.

While the segregation literature does focus on its pejorative uses and effects, there is additional evidence of “positive” outcomes associated with segregation. Peach (1996) argues that while “good” and “bad” segregation are interrelated, they are distinct concepts, which has led to misunderstandings as to the relationship between social processes and urban spatial patterns. Gil and Marion (2018) evidenced a similar phenomenon in a historical study of small businesses, where there was a positive relationship between residential segregation and market concentration of African American movie theaters. Our study provides additional evidence to Gil and Marion’s (2018) proposal of positive outcomes (e.g. improved consumption in horizontally differentiated goods) associated with higher levels of residential segregation.

4.3 Past Coaching Experience

While both Black and non-Black former NFL head coaches are more likely to secure subsequent NFL head coach positions immediately following a previous stint as an NFL head coach, substantial differences exist between Black and non-Black former NFL head coaches whose most recent position was not an NFL head coach. Specifically, Black former NFL head coaches whose most recent position was not a head coach position are more likely to secure subsequent NFL head coach positions than non-Black former NFL head coaches who also were not most recently in NFL head coach positions. There are many possible reasons why Black former NFL head coaches experience a higher likelihood of securing subsequent NFL head coach positions, relative to non-Black former NFL head coaches, when not already holding an NFL head coach position in the preceding season.

Though Black and non-Black former NFL head coaches appear to experience a relatively equal likelihood of securing subsequent NFL head coach positions immediately after holding head coach positions, and that likelihood is substantially higher than former NFL head coaches who assumed lower level coaching positions or took time away from the NFL, there is a significant racial disparity among these non-NFL head coaches when seeking subsequent NFL head coach opportunities. This disparity may be due to perceptions of former NFL coaches who went from NFL head coaches to lesser positions (or no positions), as they are more likely to be viewed as damaged goods (Ward, Sonnenfeld, and Kimberly 1995). However, among these coaches, Black former NFL coaches who took lower-level coaching positions or time away from the NFL may be perceived differently than non-Black former NFL head coaches. For example, they may have performed poorly under already-adverse circumstances (e.g. poor management, limited resources) after an initial NFL head coach opportunity that could be viewed as a glass cliff was taken. NFL team owners and general managers may view their teams as having better management or more resources, which could allow former NFL head coaches to be more successful. If minorities are more likely to obtain positions in which they are expected to fail (Cook and Glass 2014), Black former NFL head coaches may be less likely to be viewed as damaged goods, and more likely to secure subsequent NFL head coach positions after taking lower-level coaching positions.

Additionally, more previous NFL head coach positions and longer average tenures in those previous NFL head coach positions increases the likelihood of securing subsequent NFL head coach positions. However, more years of experience in general, and the age of head coaches, does not help former NFL head coaches secure subsequent head coach opportunities, indicating that head coach experiences are valuable, when varied. Given that Black NFL coaches tend to have more substantial playing experiences (Brooks et al. 2019), they may enter the coaching profession later, making them older coaches who are less likely to secure head coach positions because of their old age. Thus, age discrimination may be causing racial disparities in NFL head coach opportunities.

4.4 Past Performance

While many non-performance related factors influence the likelihood that former NFL head coaches will secure subsequent NFL head coach positions, performance related factors also play a role. Though no statistically significant evidence was found regarding the relationship between past Super Bowl appearances and securing subsequent NFL head coach positions, the overall career winning percentage and most recent career winning percentage as an NFL head coach were significant predictors of securing subsequent NFL head coach positions. However, these two measures of NFL head coach performance have substantially different effects. As expected, former NFL head coaches with higher career winning percentages as a head coach are more likely to secure subsequent NFL head coach positions.

In contrast, a former NFL head coach’s season winning percentage in the most recent season as an NFL head coach has a negative relationship with securing a subsequent NFL head coach position. Former NFL head coaches with lower winning percentages in their final season as a head coach for a team may experience a degree of forgiveness for that final poor performance that likely played a role in their dismissal. The forgivable final season as the head coach of an NFL team may be excusable for decision makers for several reasons such as: (a) a successful coach’s message may have gotten old with a team and it may be time to move on, (b) decision makers may view that final season of poor performance as an anomaly, or (c) resources may have been unavailable to the coach due to player suspensions (Foreman, Soebbing, and Seifried 2019) or injuries.

5 Conclusions

The present study found evidence of Black former NFL head coaches who coached a larger market team in the previous season being less likely to secure a subsequent NFL head coach position that season. Additionally, both Black and non-Black former NFL head coaches benefit in the NFL head coach labor market from coaching in a more segregated metropolitan area; however, Black former NFL head coaches benefit substantially more than their non-Black counterparts.

While the NFL can use this information to inform future diversity initiatives and policies (e.g. Rooney Rule modifications), individual team owners, general managers, and coaches can also benefit from this information. For example, individual team owners and general managers can identify their own biases to improve decision making when filling an NFL head coach vacancy. Black coaches can use this information to understand the optimal positions to pursue that would lead to future NFL head coach positions. Additionally, Black coaches can use the information in this study to understand the career implications of taking an NFL head coach position that may set them up for failure due to limited resources or poor management (i.e. glass cliff).

5.1 Limitations

While several meaningful statistically significant results were identified in this study, and rationales were provided regarding why these phenomena may be occurring, we cannot be certain as to why these relationships exist. While causal relationships are easier to identify using survival analysis due to the temporal nature of the analysis (Blossfeld, Golsch, and Rohwer 2009), the underlying reasons of why these relationships occur remains uncertain and beyond the purview of the statistical analysis used in the present study. Additionally, exogenous factors may be affecting the analysis. Nevertheless, through a rigorous statistical analysis using numerous robustness checks, we are confident that the results in the study are valid, and the examination of subsequent NFL head coaching opportunities is meaningful.

5.2 Future Research Opportunities

Future research can delve deeper into these issues using qualitative or quantitative analyses. Future research can seek to understand why and how decisions are made when filling NFL head coach vacancies. A variety of qualitative tools could be used to examine this issue including observations, content analyses, interviews, focus groups, or ethnographies. From a quantitative perspective, future research can examine unanswered questions in this research such as whether there is a significant disadvantage for minority coaches in the coach labor market due to sustaining longer professional playing careers. The advent of legalized betting on American professional sport has led to greater data availability of NFL market odds. This would allow future work to assess a head coach’s success based on predicted gambling expectations. Another opportunity for qualitative or quantitative research could be to examine why, or under what conditions, is poor performance in a final season as a head coach desirable for decision makers filling head coach vacancies.

References

Blossfeld, H. P., K. Golsch, and G. Rohwer. 2009. Event History Analysis with Stata. New York: Psychology Press.Search in Google Scholar

Bozeman, B., and D. Fay. 2013. “Minority Football Coaches’ Diminished Careers: Why Is the ‘Pipeline’ Clogged?” Social Science Quarterly 94 (1): 29–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2012.00931.x.Search in Google Scholar

Braddock, J. H., E. Smith, and M. P. Dawkins. 2012. “Race and Pathways to Power in the National Football League.” American Behavioral Scientist 56 (5): 711–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764211433802.Search in Google Scholar

Brooks, S. N., C. K. Harrison, K. L. Gallagher, S. Bukstein, L. Brenneman, and R. Lofton. 2019. Field Studies: A 10-Year Snapshot of NFL Coaching Hires. Retrieved from Global Sport Education and Research Lab; Global Sport Institute at Arizona State University (GSERL Working Paper Series Volume 1, Issue 1): gserl.org.Search in Google Scholar

Brown, M. C. 1982. “Administrative Succession and Organizational Performance: The Succession Effect.” Administrative Science Quarterly 27 (1): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392543.Search in Google Scholar

Bursik, P. B. 2012. “Behavioral Economics in the NFL.” In The Economics of the National Football League, edited by K. G. Quinn, 259–76. New York: Springer.10.1007/978-1-4419-6290-4_15Search in Google Scholar

Collins, B. W. 2007. “Tackling Unconscious Bias in Hiring Practices: The Plight of the Rooney Rule.” NYU Law Review 82: 870–912.Search in Google Scholar

Cook, A., and C. Glass. 2014. “Above the Glass Ceiling: When Are Women and Racial/ethnic Minorities Promoted to CEO?” Strategic Management Journal 35 (7): 1080–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2161.Search in Google Scholar

Cosgrove, E. 2019. “NFL Teams Slash Staff on ‘Black Monday.’ Here’s Who’s Out.” CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2019/12/30/nfl-teams-slash-staff-on-black-monday-heres-whos-out.html.Search in Google Scholar

Cunningham, G. B., and T. Bopp. 2010. “Race Ideology Perpetuated: Media Representations of Newly Hired Football Coaches.” Journal of Sports Media 5 (1): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1353/jsm.0.0048.Search in Google Scholar

Dajani, J. 2024. “NFL to Play First-Ever Game in Spain: League to Hold 2025 Regular-Season Game in Real Madrid’s Stadium.” CBS Sports, https://www.cbssports.com/nfl/news/nfl-to-play-first-ever-game-in-spain-league-to-hold-2025-regular-season-game-in-real-madrids-stadium/#:∼:text=In%202025%2C%20the%20NFL%20will,home%20to%20Real%20Madrid%20C.F.Search in Google Scholar

Das, S. 2020. “Top 10 Most Popular Sport in America 2020 (TV Ratings).” Sports Show. https://sportsshow.net/most-popular-sports-in-america/.Search in Google Scholar

Ducking, J., P. A. Groothuis, and J. R. Hill. 2015. “Exit Discrimination in the NFL: A Duration Analysis of Career Length.” The Review of Black Political Economy 42 (3): 285–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12114-014-9207-9.Search in Google Scholar

Dwivedi, P., V. F. Misangyi, and A. Joshi. 2021. ““Burnt by the Spotlight”: How Leadership Endorsements Impact the Longevity of Female Leaders.” Journal of Applied Psychology 106 (12): 1885–906. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000871.Search in Google Scholar

Ehrlich, J., S. Ghimire, and S. Sanders. 2021. “NFL Team Revenue Distribution and Revenue Sharing: A Median Voter Theorem.” Managerial Finance 47 (4): 525–34. https://doi.org/10.1108/mf-03-2020-0105.Search in Google Scholar

Flores, R., D. Forrest, and J. D. Tena. 2012. “Decision Taking under Pressure: Evidence on Football Manager Dismissals in Argentina and Their Consequences.” European Journal of Operational Research 222 (3): 653–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2012.03.033.Search in Google Scholar

Foreman, J., B. Soebbing, C. Seifried, and K. Agyemang. 2018. “Examining Relationships between Managerial Career Advancement and Centrality, Race, and the Rooney Rule.” International Journal of Sport Management 19 (3): 315–38.Search in Google Scholar

Foreman, J. J., B. P. Soebbing, and C. S. Seifried. 2019. “The Impact of Deviance on Head Coach Dismissals and Implications of a Personal Conduct Policy.” Sport Management Review 22 (4): 491–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2018.06.012.Search in Google Scholar

Foreman, J. J., J. S. Bendickson, and B. J. Cowden. 2021. “Agency Theory and Principal–Agent Alignment Masks: an Examination of Penalties in the National Football League.” Journal of Sport Management 35 (2): 105–16. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2019-0352.Search in Google Scholar

Fredrickson, J. W., D. C. Hambrick, and S. Baumrin. 1988. “A Model of CEO Dismissal.” Academy of Management Review 13 (2): 255–70. https://doi.org/10.2307/258576.Search in Google Scholar

Frick, B., and B. Wallbrecht. 2012. “Infant Mortality of Professional Sports Clubs: An Organizational Ecology Perspective.” Jahrbucher für Nationalokonomie und Statistik 232 (3): 360–89. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110511185-011.Search in Google Scholar

Gems, G. R. and Pfister, G. (2019) Touchdown: An American Obsession. Great Barrington, MA: Berkshire.Search in Google Scholar

George, L. 2007. “What’s Fit to Print: The Effect of Ownership Concentration on Product Variety in Daily Newspaper Markets.” Information Economics and Policy 19 (3-4): 285–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoecopol.2007.04.002.Search in Google Scholar

Gil, R., and J. Marion. 2018. “Residential Segregation, Discrimination, and African-American Theater Entry during Jim Crow.” Journal of Urban Economics 108: 18–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2018.09.004.Search in Google Scholar

Graziano, D. 2020. “NFL Approves Rooney Rule Changes, Tables Minority Hiring Incentives.” ESPN. https://www.espn.com/nfl/story/_/id/29194925/nfl-approves-rooney-rule-changes-tables-minority-hiring-incentives.Search in Google Scholar

Groothuis, P. A., and J. R. Hill. 2004. “Exit Discrimination in the NBA: A Duration Analysis of Career Length.” Economic Inquiry 42 (2): 341–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/ei/cbh065.Search in Google Scholar

Hair, J., W. Black, B. Babin, and R. E. Anderson. 2010. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed. London: Pearson Prentice Hall.Search in Google Scholar

Hambrick, M. E., J. R. Bass, and C. C. Schaeperkoetter. 2014. “The Biggest Hire in School History”: Considering the Factors Influencing the Hiring of a Major College Football Coach.” Case Studies in Sport Management 3 (1): 82–92. https://doi.org/10.1123/cssm.2014-0002.Search in Google Scholar

Henry, T. M., and T. P. Oates. 2020. ““Sport Is Argument”: Polarization, Racial Tension, and the Televised Sport Debate Format.” Journal of Sport & Social Issues 44 (2): 154–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723519881199.Search in Google Scholar

Keidel, R. W. 1987. “Team Sports Models as a Generic Organizational Framework.” Human Relations 40 (9): 591–612. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872678704000904.Search in Google Scholar

King, P. 2020. “FMIA: NFL Has a ‘Broken System’ for Minority Hiring. Here Is How to Fix it.” Peter King’s Football Morning in America. https://profootballtalk.nbcsports.com/2020/05/25/nfl-minority-hiring-rooney-rule-fmia-peter-king/.Search in Google Scholar

Kirk, J. 2020. “Alabama’s Highest-Paid State Employee in a Pandemic Year Will Be a Fired Football Coach.” Slate. https://slate.com/culture/2020/12/gus-malzahn-buyout-auburn-fired-college-football-coaches-chaching.html.Search in Google Scholar

Laine, J. 2021. “NFL’s Roger Goodell: Two Minority Head Coach Hirings ‘Wasn’t What We Expected.” ESPN. https://www.espn.com/nfl/story/_/id/30835175/nfl-roger-goodell-two-minority-head-coach-hirings-expected.Search in Google Scholar

Madden, J. F. 2004. “Differences in the Success of NFL Coaches by Race, 1990–2002: Evidence of Last Hire, First Fire.” Journal of Sports Economics 5 (1): 6–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002503257245.Search in Google Scholar

Maxcy, J. G. 2013. “Efficiency and Managerial Performance in FBS College Football to the Employment and Succession Decisions, Which Matters the Most, Coaching or Recruiting?” Journal of Sports Economics 14 (4): 368–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002513497170.Search in Google Scholar

Ndofor, H. A., R. L. Priem, J. A. Rathburn, and A. K. Dhir. 2009. “What Does the New Boss Think? How New Leaders’ Cognitive Communities and Recent “Top-Job” Success Affect Organizational Change and Performance.” The Leadership Quarterly 20 (5): 799–813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.06.011.Search in Google Scholar

Nelson, D., and J. Quick. 2017. ORGB, 5th ed. Boston: Cengage Learning.Search in Google Scholar

Ospina, L. 2024. “Missing the Mark: How Legislative Adjustments to the Disparagement Clause Could Promote the Revocation of Trademarks for Professional Sporting Teams Referencing Native American Culture.” Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal 31 (1): 183–216.Search in Google Scholar

Othering & Belonging Institute. 2022. Technical Appendix. Berkeley: University of California. https://belonging.berkeley.edu/technical-appendix.Search in Google Scholar

Ozanian, M., and J. Teitelbaum. 2023. “NFL Team Valuations.” Forbes.Search in Google Scholar

Peach, C. 1996. “Good Segregation, Bad Segregation.” Planning Perspectives 11 (4): 379–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/026654396364817.Search in Google Scholar

Perry, A., R. Seo, A. Barr, C. Romer, and K. Broady. 2022. Black-owned Businesses in US Cities: Challenges, Solutions, and Opportunities for Prosperity. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution.Search in Google Scholar

Romer, D. 2006. “Do Firms Maximize? Evidence from Professional Football.” Journal of Political Economy 114 (2): 340–65. https://doi.org/10.1086/501171.Search in Google Scholar

Rose, D. 2016. “NFL Head Coaches Hired in the Last Decade: What the Data Says.” The Cauldron. https://the-cauldron.com/nfl-head-coaches-hired-during-the-last-ten-years-a-look-at-the-data-a41e2e68a1b6.Search in Google Scholar

Rosette, A. S., G. J. Leonardelli, and K. W. Phillips. 2008. “The White Standard: Racial Bias in Leader Categorization.” Journal of Applied Psychology 93 (4): 758–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.4.758.Search in Google Scholar

Salaga, S., and M. Juravich. 2020. “National Football League Head Coach Race, Performance, Retention, and Dismissal.” Sport Management Review 23 (5): 978–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2019.12.005.Search in Google Scholar

Smith, E. B., J. Chown, and K. Gaughan. 2021. “Better in the Shadows? Public Attention, Media Coverage, and Market Reactions to Female CEO Announcements.” Sociological Science 8: 119–49. https://doi.org/10.15195/v8.a7.Search in Google Scholar

Soebbing, B. P., and M. Washington. 2011. “Leadership Succession and Organizational Performance: Football Coaches and Organizational Issues.” Journal of Sport Management 25 (6): 550–61. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.25.6.550.Search in Google Scholar

Solow, B. L., J. L. Solow, and T. B. Walker. 2011. “Moving on Up: The Rooney Rule and Minority Hiring in the NFL.” Labour Economics 18 (3): 332–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2010.11.010.Search in Google Scholar

TIDES. 2020. The 2020 Racial and Gender Report Card: National Football League. Orlando, FL: University of Central Florida, The Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport. https://www.tidesport.org/.Search in Google Scholar

Ward, A., J. A. Sonnenfeld, and J. R. Kimberly. 1995. “In Search of a Kingdom: Determinants of Subsequent Career Outcomes for Chief Executives Who Are Fired.” Human Resource Management 34 (1): 117–39. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.3930340108.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Guest Editorial

- Special Issue Articles

- Is Blood Thicker than Water? The Impact of Player Agencies on Player Salaries: Empirical Evidence from Five European Football Leagues

- When Colleagues Come to See Each Other as Rivals: Does Internal Competition Affect Workplace Performance?

- Pregnancy in the Paint and the Pitch: Does Giving Birth Impact Performance?

- An Empirical Estimation of NCAA Head Football Coaches Contract Duration

- Race, Market Size, Segregation and Subsequent Opportunities for Former NFL Head Coaches

- Football Fans’ Interest in and Willingness-To-Pay for Sustainable Merchandise Products

- Change in Home Bias Due to Ghost Games in the NFL

- Consumer Perceptions Matter: A Case Study of an Anomaly in English Football

- Talent Allocation in European Football Leagues: Why Competitive Imbalance May be optimal?

- Data Observer

- SOEP-LEE2: Linking Surveys on Employees to Employers in Germany

- The IAB-SMART-Mobility Module: An Innovative Research Dataset with Mobility Indicators Based on Raw Geodata

- Miscellaneous

- Annual Reviewer Acknowledgement

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Guest Editorial

- Special Issue Articles

- Is Blood Thicker than Water? The Impact of Player Agencies on Player Salaries: Empirical Evidence from Five European Football Leagues

- When Colleagues Come to See Each Other as Rivals: Does Internal Competition Affect Workplace Performance?

- Pregnancy in the Paint and the Pitch: Does Giving Birth Impact Performance?

- An Empirical Estimation of NCAA Head Football Coaches Contract Duration

- Race, Market Size, Segregation and Subsequent Opportunities for Former NFL Head Coaches

- Football Fans’ Interest in and Willingness-To-Pay for Sustainable Merchandise Products

- Change in Home Bias Due to Ghost Games in the NFL

- Consumer Perceptions Matter: A Case Study of an Anomaly in English Football

- Talent Allocation in European Football Leagues: Why Competitive Imbalance May be optimal?

- Data Observer

- SOEP-LEE2: Linking Surveys on Employees to Employers in Germany

- The IAB-SMART-Mobility Module: An Innovative Research Dataset with Mobility Indicators Based on Raw Geodata

- Miscellaneous

- Annual Reviewer Acknowledgement