Abstract

Rh/γ-Al2O3 nanocatalysts with different metal loading were synthesized by two different techniques i. e. microemulsion and microwave irradiated solvothermal technique. Synthesized nanocatalysts were then successfully implemented for the hydrogenation of 4’,4”(5”)-di-tert-butyldibenzo-18-crown-6 ether (DTBuB18C6) at 70 bar, 353–393 K temperature and 5 h. It was observed that 3 wt% nanocatalyst obtained by microemulsion technique exhibited higher catalytic activity and resulted 40 % conversion with high selectivity towards cis-syn-cis di-tert-dicyclohexano-18-crown-6ether (CSC DTBuCH18C6).

1 Introduction

The removal and recovery of radiostrontium from nitric-acid-containing nuclear waste solutions is of considerable importance in the processing of such wastes for final disposal (Dietz et al. 1999). One of the most exciting features of crown ethers is their ability to complex with many compounds.

The crown ether dicyclohexano-18-crown-6 (DCH18C6), which attracted the attention of researchers, was used as a commercial product consisting of a mixture of stereoisomers, mainly cis-syn-cis and cis-anti-cis, without any purification or separation. However, these isomers are known to have very different metal-complexing properties and liquid-liquid extraction behaviour (Landre et al. 1993; Hafizi et al.1992; Abashkin et al. 1996). Horwitz, Dietz, and Fisher (1991) have investigated dicyclo-hexano18crown6 (DCH18C6) and it’s di-tert-butyl derivative (DTBuCH18C6) as Sr2+ selective extractants employing a variety of oxygenated aliphatic diluents e. g. alcohols, ketones, carboxylic acids and esters. Horwitz and Dietz (1992), also found that a solvent extraction process based on DTBuCH18C6 in 1-octanol was an effective method for the extraction and recovery of Sr2+. Hafizi, Abolghasemi, and Milani (1992), reported that dicyclo-hexano18crown6 (DCH18C6) and 18-crown-6 (18C6) extracted 99.91 % and 87.73 % of strontium, respectively and other crown ethers couldn’t extract the strontium greater than 16 %. A new polymeric membrane containing cellulose triacetate as the monomer, di-tert-butylcyclohexano-18-crown-6 (DTBuCH18C6) as the carrier and 2-nitrophenyl octyl ether (NPOE) as the plasticizer was developed by Mohapatra et al. (2004), Mohapatra, Lakshmi, and Manchanda (2006) for the selective transport of Sr2+ from aqueous nitrate solution. DTBuCH18C6 is usually prepared by the catalytic hydrogenation of DTBuB18C6, which yields mainly two stereoisomer’s of cis-syn-cis (CSC) and cis-anti-cis (CAC) DTBuCH18C6.The efficiency of this hydrogenation step, and thus the yield of the reduced product, varies with the reaction conditions (e. g., temperature, pressure, catalyst) Bond, Barrans, and Horwitz (2006a, 2006b). Metaxas and Papayannakos (2006) studied liquid-phase catalytic hydrogenation of benzene in a three-phase bench-scale reactor using Pd/Al2O3 and Ni/ Al2O3. Reaction kinetics and external gas-liquid mass transfer effects for the system were estimated. Unless purified, DTBuCH18C6 will contain unreacted starting materials and various side products, none of which is particularly effective as an extractant for strontium. As separation of stereoisomer’s is a complex and expensive process, so selective hydrogenation is worth considering. Kralik et al. (2012) studied liquid phase hydrogenation of aromatics using transition metal catalysts in batch slurry system and discussed about diffusivity of components influencing the reaction rate and deactivation of catalysts. The hydrogenation of aromatic compounds is well documented in the literature as far as parent hydrocarbons are concerned, but is scarcer as regards the stereoselective hydrogenation of substituted aromatics (Galletti et al. 2008; Patel et al. 2015; Nandanwar et al. 2015).

Ruthenium (Ru) and Rhodium (Rh) nanocatalyst show high activity and stereoselectivity simultaneously due to its zero valence state and nano-scale size. Most particularly rhodium was used in hydrogenation, hydroformylation reactions and oxidation reactions (Guerrero et al. 2013). Long back, Landre et al. (1994), used colloidal Rh catalyst for the hydrogenation DB18C6 and obtained 100 % conversion, 86 % chemoselectivity and syn:anti ratio 34:66 in presence of Aliquat-336 as phase transfer catalyst. Recently Gao, Chen, and Chen (2012), carried out hydrogenation of DB18C6 using ruthenium nanocatalyst at 408 K and 10.0 MPa and obtained 99.4 % conversion with 6:1 ratio of the syn/anti DCH18C6 as product. Wang et al. (2014) prepared simple and efficient heterogeneous Pd/NiO catalyst for the hydrogenation of a variety of substituted aromatic compounds to the corresponding cyclohexane and cyclohexanol derivatives. Activity and reusability of the catalyst was also investigated. Salih et al. (2014) used Rh-Fe/MgO catalyst for hydrogenation of DTBuB18C6 and found 78 % conversion and 53 % yield of DTBuCH18C6 under low hydrogen pressure (4 MPa), 500 °C and 3 h. Suryawanshi et al. (2015) used Ru/γ-Al2O3 nanocatalyst for the hydrogenation DB18C6 at 9 MPa, 393 K temperature and 3.5 h and found that 4 wt% Ru/γ-Al2O3 exhibited higher catalytic activity and 96.7 % conversion with 100 % selectivity towards CSC DCH18C6.

Variety of synthesis methods are being used for the development of nanoparticles for their potential use in the various field. Some of the familiar methods are co-precipitation, hydrothermal, solvothermal, sonochemical method, microwave irradiation and micro-emulsion methods. Ideally, the methods employed for synthesis are expected to form nanoparticles with narrow size distribution and easily modify particle properties such as size and surface during the synthesis.

Present study reveals hydrogenation of DTBuB18C6 over Rh/γ-Al2O3 nanocatalysts synthesized by two different techniques i. e. microemulsion and microwave irradiated solvothermal technique. Highly monodispersed metal nanocatalyst would be effective for hydrogenation of DTBuB18C6 under mild reaction conditions. Effects of reaction temperature, catalysts loading were also studied. Effects of rhodium nanocatalyst towards stereoselectivity and reaction kinetics were also discussed herein.

2 Experimental and procedure

2.1 Materials

Rhodium trichloride (RhCl3.nH2O, Rh Content ≥37 %) was purchased from finar chemicals, India. Poly (N-vinyl-2-Pyrrolidone) (PVP as stabilizer, average molecular weight 40,000) was purchased from Heny fine chemicals, India. The reducing agent sodium borohydride and non-ionic surfactant Dioctyl sulfosuccinate sodium (AOT) were purchased from S. D. Fine Chemicals, India. Distilled water of pH 5.9±0.2, conductivity 1.0 μScm–1 (Millipore, Elix, India) was used throughout the experiments for preparing all the aqueous solutions. Gamma alumina powder (support) of 98 % purity and 100 mesh size was purchased from National Chemicals, India. Other organic solvents like n-BuOH, chloroform, acetone, ethylene glycol, cyclohexane, toluene of analytical grade were purchased from Merck chemicals, India and used without further purification. DTBuB18C6 and Alumina (for purification of product mixtures) between (100–200 mesh) were purchased from sigma Aldrich India.

2.2 Catalyst preparation

2.2.1 Synthesis of Rh nanoparticles by Microemulsion Technique (ME)

Rh nanoparticles were synthesized by the w/o microemulsion technique comprising cyclohexane, AOT as surfactant, aqueous solution of salt, RhCl3 and reducing agent, NaBH4 as mentioned in the earlier paper (Nandanwar et al. 2011). In detail, high purity oil phase, cyclohexane, and nonionic surfactant Dioctyl sulfosuccinate sodium (AOT) were used for the preparation of water-in-oil (w/o) microemulsion. Microemulsion-I was prepared by mixing an aqueous solution of RhCl3 in cyclohexane-AOT mixtures. Uniform stirring was maintained with ultraturax T25 high-speed mechanical stirrer (Ultraturax IKA WERKE, GmBH & Co. KG) at 6,000 rpm for 4 min at room temperature for proper mixing. Both metal ions and surfactant concentration in the microemulsion were initially maintained at 0.2 M. The volume content of the aqueous phase was varied to achieve a water-to-surfactant (ω) value equal to 3. Higher ω was achieved by adding an additional amount of aqueous solution as required. Similarly, microemulsion-II of the same ω value was prepared simply by replacing the solution of RhCl3 by that of NaBH4 (0.5 M) solution. The two microemulsions were mixed to produce microemulsion-III containing Rh nanoparticles and were used for further characterization.

2.2.2 Synthesis of Rh nanoparticles by Microwave Irradiated Solvothermal Technique (MWI)

Rhodium (III) chloride as precursor salt and Poly (N-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone) (PVP as a capping agent) were dissolved in ethylene glycol, which played a dual role for synthesis, as solvent and also as reducing agent, was irradiated in microwave reactor (300 W, 200◦C) and cooled down by ice chilled water (Suryawanshi et al. 2013). Briefly, an advanced microwave synthesis labstation (MILESTONE, India) operating at 2.45 GHz frequency was used in the synthesis of Ru nanoparticles. Capping agent, polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) (1.73×10–4 mol) and RhCl3×H2O (1.44×10–5 mol) were dissolved in ethylene glycol maintaining a fixed ratio of PVP/RhCl3 (0.1) under vigorous stirring. After complete dissolution of the primary materials, red wine coloured reaction mixture was charged into reaction vial [PTFE (polytetrafluroethylene) lined vessels of 100 ml capacity, withstand 300 °C temperature and 50 bar maximum pressure] and heated upto 200 °C varying MW irradiation power.

2.2.2.1 Synthesis of nanocatalyst

Rh/γ-Al2O3 nanocatalyst was synthesized by transferring the Rh nanoparticles onto the support to maintain the homogeneous distribution. The concentrated colloidal Rh nanoparticle (accumulated after repeated experimentation) was re-dispersed in methanol and the known quantity of γ-Al2O3 support was added under vigorous stirring. The mixture was mechanically stirred (6,500 rpm using Ultraturax) for 24 h. After evaporating the methanol, the mixture was washed with acetone and water to remove the organic and inorganic impurities and dried at 100 °C for 6 h. The catalyst was calcinated at 300 °C for 8 h in an oven under inert (nitrogen) atmosphere and was used for further characterization and catalyst testing.

2.3 Characterization of nanoparticle and nanocatalyst

The absorption spectra of rhodium were analyzed at different time interval using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (HACH, Germany). The size of nanoparticles was measured using particle size analyzer (Malvern Zetasizer, Nano ZS 90, U.K.). XRD analysis was performed on Bruker D8 (AXE) Powder X-ray diffractometer with Cu-Kα radiation (λ=1.54056 Å) in the range of 5-90°. TEM images were obtained with a Philips Tecnai – 20, Holland. SEM/EDAX analysis was performed on Shimadzu SSX-550. N2 adsorption-desorption and hydrogen chemisorptions were carried out by a Micromeritrics ASAP 2010 and Micromeritrics Chemisorb 2750, USA. Sr2+ concentration was determined by Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS, GBC Scientific Equipment Avanta make).

2.4 Catalytic hydrogenation of DTBDB18C6

2.4.1 Hydrogenation test

The substrate (DTBuB18C6) was dissolved in benzene (4 g sample/100 mL of benzene).The solution was heated to reflux and the benzene containing azeotrope collected in the Dean-Stark collector was discarded intermittently. Benzene was removed by a rotary evaporator, crystals of DTBuB18C6 started to form and the viscous solution was dissolved in n-butanol. In the above reaction mixture small amount of acetic acid (3–4 ml) was added as accelerator along with the catalyst. Mixing and dissolution was carried out as rapidly as possible to avoid contact with moisture in the air. Nitrogen was passed through a drying agent (CaCl2) chamber, was flushed into the reaction mixture while the reactor was heated rapidly for about ten minutes. The temperature of the reactor was around 35–40 °C. The nitrogen tube was disconnected, all the valves were closed, and the hydrogen was added to 510 psi. When the temperature of the reactor reached around 100 °C (varied between 80 and 120 °C), the reaction occurred and then the pressure drop was monitored upto 5 h.

2.4.2 Product analysis

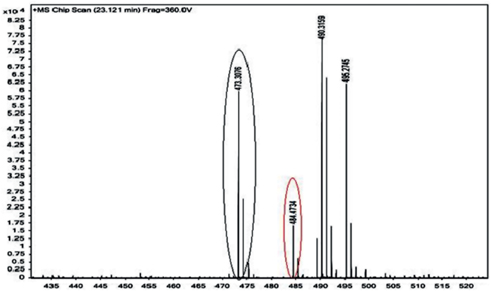

After 5 h, the temperature of the liquid reaction mixture was brought to ambient temperature. The pressure was released and excess hydrogen gas was typically removed following standard practices. The heterogeneous catalyst (Rh/γ-Al2O3) was separated from the liquid reaction mixture by filtration. The solvent (n-butanol and small amount of acetic acid) was removed by rotary evaporation under reduced pressure, and the residue was dried under high vacuum at a temperature of about 100 °C to about 120 °C. After evaporation, sample was passed through packed column for purification (stationary phase: alumina and mobile phase: chloroform). The purified sample was then analyzed by High Resolution Liquid Chromatography and Mass Spectroscopy (HRLCMS) of Agilent Technologies, USA having nanoHPLC with chipcube (Microfluidic column) mass spectrometer (Figure 1). The mass spectrometer was operated at an accelerating voltage of 8 kV and the slits set for a resolution of 3000 (10 % valley) A 0–90 % (v/v) methanol-acetonitrile gradient (60 min) was employed for analysis. Product mixture analysed by HRLCMS (Figure 1) showed main product peaks i. e. (MS peaks at 484.38, 485.38, 486.38 a.m.u.), proton NMR [1H: (200 MHz; CDCl3): 1.02–1.1 (m, 18H, –CH3), 1.3–2.0 (m, 16H, –CH2–), 3.4–3.7 (m, 4H, –CH–) and 3.7–3.9 (m, 16H, –CH2O–)].

2.4.3 Distribution coefficient (KD)

From reported literature it was found that isomeric form cis-syn-cis DCH18C6 showed most effective extracting power for Sr2+ (Dietz et al. 1999). Distribution coefficient (KD) is the ratio of concentration of Sr2+ in organic phase (octanol) to the concentration of Sr2+ in aqueous phase (3 M HNO3). 0.2 M of DTBuCH18C6 was added to the organic phase to extract Sr2+ from nuclear waste. After the extraction experiment (repeated three times) at room temperature, the strontium concentration in the aqueous phases were analysed by AAS at 460.7 nm wavelength with nitrous oxide burner at about 2,900 °C. Distribution coefficient (KD) was found to be 5 with 83.6 % extraction of Sr2+ from aqueous feed phase. From Table 1, it was observed that extraction with 0.2 M DTBuCH18C6 showed higher KD value and better extraction efficiency compared to the extraction processes carried out with our earlier synthesised product DCH18C6, which indicated mainly cis-syn-cis DTBuCH18C6 formed as a product (Suryawanshi et al. 2015).

Batch equilibrium studies for Sr2+ extraction with synthesized DTBuCH18C6 and DCH18C6.

| Ligand concentration | KD | % Extraction |

|---|---|---|

| 0.1 M synthesized DCH18C6 in Octanol | 3 | 74.6 |

| 0.2 M synthesized DCH18C6 in Octanol | 3.7 | 78.5 |

| 0.2 M synthesized DTB DCH18C6 in Octanol | 5.1 | 83.6 |

Effect of temperature on conversion and initial rate constant.

| Temperature (°C) | 3 % ME | 3 % MWI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Conversion | Initial rate constant k (min–1) | % Conversion | Initial rate constant k (min–1) | |

| 80 | 23 | 0.005 | 23 | 0.004 |

| 90 | 30 | 0.006 | 28 | 0.005 |

| 100 | 40 | 0.01 | 33 | 0.006 |

| 110 | 31 | 0.007 | 30 | 0.005 |

| 120 | 29 | 0.006 | 29 | 0.005 |

Physical properties of Rh/γ-Al2O3 nanocatalysts.

| Entry | BET (m2/g) | Pore volume (cm3/g) | Average pore diameter (nm) | Supported metal surface area per gm of catalyst (SM, m2/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure γ-Al2O3 | 242 | 0.23 | 3.82 | 0 |

| 3wt. % ME | 214.42 | 0.210 | 3.69 | 41.23 |

| 3wt. % MWI | 216.20 | 0.184 | 3.47 | 39.65 |

3 Result and discussion

3.1 Formation of Rh nanoparticle

Progress of the formation of Rh nanoparticle was monitored (Figure 2) by UV-Vis spectrophotometer. Rh3+ would be converted to Rh0 by ME and MWI technique [Rh3+ (pinkish) → Rh0 (faint brown)]. A broad absorbance peak at around 255 nm attributed to Rh3+ ions. This peak disappeared within 20 min due to gradual reduction of Rh3+ to Rh0.

HRLCMS analysis of synthesized product.

UV-Visible absorption spectra of synthesized Rh nanoparticles.

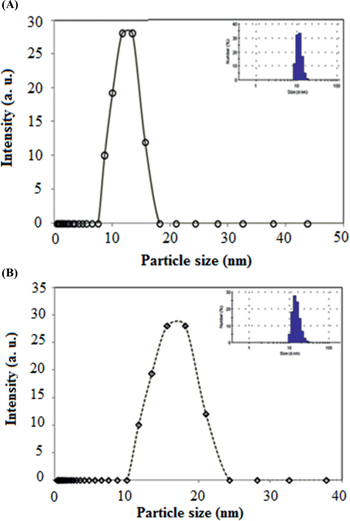

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) revealed information about the hydrodynamic radius of synthesized Rh nanocolloids. It was observed from Figure 3(A) and 3(B) that particles size of Rh nanocolloids synthesized by ME and MWI technique were in the range of 4–14 nm Figure 3(A) and 10–25 nm Figure 3(B) respectively.

DLS profile of Rh nanoparticles synthesized by (A) ME (B) MWI technique.

3.2 Catalyst characterization

3.2.1 XRD analysis

Figure 4(A) showed peaks at different 2θ angles like 42.7o (Rh0-111), 47.4o (Rh0-200), 70.4o (Rh0-220) for Rh in metallic state which was consistent with the standard rhodium metal Rh (111) fcc, data file (JCPDS No. 05–0685). Figure 4(B) showed additional peaks at 86.5o (Rh0-311), 89.8o (Rh0-222). Peak at 2θ=66.5° in both figures indicated the presence of γ-alumina as per JCPDS file No. 10–0425. Nature of the XRD pattern (sharp peak) additionally suggested the high crystalline nature of the catalyst (Biacchi et al. 2011; Kim et al. 2013).

XRD of Rh/γ-Al2O3 nanocatalysts synthesized by (A) ME (B) MWI technique.

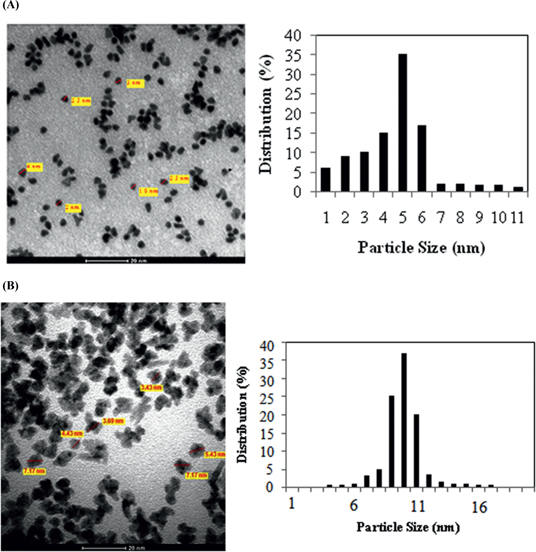

3.2.2 TEM analysis

The surface morphology of the Rh/γ-Al2O3 (3 wt% Rh) catalyst synthesized by ME (Figure 5(A)) and MWI technique (Figure 5(B)) were studied by TEM. Figures showed that Rh nanoparticles imaged as black dark dots and were uniformly dispersed on the γ-Al2O3 support, with size of the Rh nanoparticles ranging from 2–10 nm (ME) & 4–14 nm (MWI) respectively. Average particle sizes (~4 nm for ME & ~9 nm for MWI) were in good agreement with the particle size calculated by the Debye Scherrer formula (~7 nm) and (~10 nm) respectively.

TEM images and particle size distribution of Rh/γ-Al2O3 nanocatalysts synthesized by (A) ME (B) MWI technique.

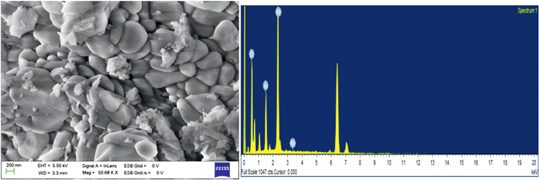

3.2.3 SEM and EDAX analysis

SEM analysis (Figure 6) of 3 wt% Rh/γ-Al2O3 synthesized by ME technique revealed that rhodium nanoparticles of various sizes were uniformly dispersed on the surface, covering the whole surface of γ-Al2O3 and the EDAX analysis indicated the presence of the rhodium, aluminium, oxygen on the surface of the catalyst.

SEM image and EDAX profile of Rh/γ-Al2O3 nanocatalysts synthesized by ME technique.

3.3 Catalytic activity of DTBuB18C6 hydrogenation reaction

The Rh/γ-Al2O3 nanocatalysts synthesized by different technique (2–4 wt% Rh) were used for the hydrogenation of DTBuB18C6. Reaction was monitored by checking pressure drop at different time intervals. Initially, the reaction pressure, temperature, catalyst loading and time were optimized to achieve maximum conversion and was found to be 7 MPa H2, 373 K, 3 wt% Rh/γ-Al2O3 and 5 h respectively.

Conversion profile (Figure 7) at different temperature showed %conversion data of DTBuB18C6 hydrogenation reaction. Comparing the catalytic activities of synthesized nanocatalysts, 3 wt% Rh/γ-Al2O3 synthesized by microemulsion technique was considered to be the optimum because it provided the highest (40 %) conversion of DTBuB18C6 and high selectivity towards CSC DTBuCH18C6. Higher metal loading (4 wt%) would cause more aggregation of the nanoparticles and resulted lesser surface area for hydrogenation which was responsible for lower catalytic activity.

Conversion profile at different temperature with synthesized Rh/γ-Al2O3 nanocatalysts.

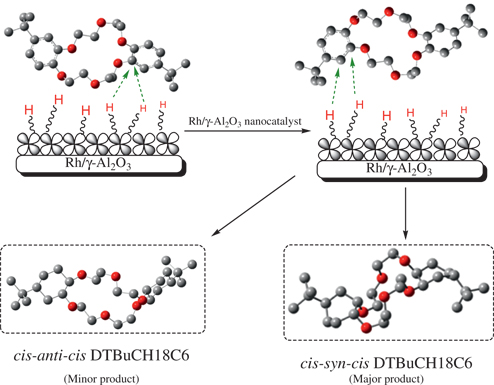

Actually Rh0 has higher density of electron around the atom, and thus larger repulsion to the cyclohexyl ring which is produced by the reduction of one benzene ring of DTBuB18C6. As the half-hydrogenated crown ether molecule getting close to the Rh catalyst, cyclohexyl ring will be easily pushed to the opposite side and as far as possible to the catalyst surface and produced mainly CSC DTBuCH18C6 (Figure 8) (Suryawanshi et al. 2015). High distribution ratio (KD) also supported formation of higher amount of CSC DTBuCH18C6 in the product mixture.

Mechanism of formation of CSC DTBuCH18C6 on Rh/γ-Al2O3 nanocatalyst.

This reaction could be considered as first order with respect to DTBuB18C6 as concentration of hydrogen will be more compared to DTBuB18C6.

Where, CA=concentration of the reactant, DTBuB18C6 at time t, CA0=initial concentration of the reactant and k = rate constant for the first-order reaction.

Rate constant for first-order reaction can be calculated by the equation

The activation energy of the reaction can be calculated by Arrhenius equation,

Here k0 is the pre-exponential factor, E is the activation energy, R is the gas constant (8.314 J mol–1 K–1), T is the absolute temperature (K).

From ln CA/CA0 vs time plot (Figure 9(A) and 9(B)), the initial rate constant (upto 15 min of reaction time) was calculated varying the reaction temperature (80–120 °C). Table 2 showed that the rate constant value obtained using 3 wt% ME and MWI nanocatalysts increased linearly with increasing the reaction temperature from 80–100 °C and then decreased at higher temperature (Table 2). Actually, the higher reaction temperature promotes desorption of DTBuB18C6 and the surface coverage of hydrogen at higher temperature is lower, both of which disfavour the hydrogenation of DTBuB18C6 to DTBuCH18C6 (Nandanwar et al. 2013).

Plot of –ln Ct/C0 vs. time using A) 3wt% ME B) 3wt% MWI nanocatalysts Reaction conditions: Pressure 70 bar; catalyst amount 0.3gm; reaction time 300 min; 3 gm DTBuB18C6; 30ml n-butanol and 0.3 mL acetic acid.

From Arrhenius plot (Figure 10) activation energies of 3 wt% ME and MWI catalysts were calculated and found to be 13.7 and 21.1 kJ mol–1 respectively.

Arrhenius Plot : lnk vs 1/T.

Kinetics of competitive hydrogenation of C=C has been previously studied (Jain et al. 2014) and LHHW (Langmuir Hinshelwood Hougen Watson) model has been reported for liquid-gas phase hydrogenation of aromatic compounds (Kralik et al. 2012). Considering competitive and dissociative adsorption of hydrogen for the hydrogenation reaction of DTBuB18C6, following model was found to be best fitted.

CH2 = concentration of H2 in the liquid phase (kmol/m3)

CB = concentration of the reactant in the liquid phase(kmol/m3)

KH2 = adsorption equilibrium constant for H2 (m3/kmol)

KB = adsorption equilibrium constant for the reactant (m3/kmol)

k3 = surface reaction rate constant (kmol kgcat−1 min−1)

r = rate of reaction (kmol kgcat−1 min−1)

From Table 3, it was observed that of 3 wt. % ME nanocatalyst had comparatively smaller specific surface areas (SBET=214.42 m2/g) than 3 wt. % MWI nanocatalyst (SBET=216.20 m2/g) but chemisorption data showed that active metal surface area of 3 wt% ME nanocatalyst was higher (SM=41.23 m2/g) compared to 3 wt% MWI nanocatalyst (SM=39.65 m2/g) to carry out the hydrogenation reaction, which supported activation energy data obtained from Arrhenius plot. TEM image of 3 wt% ME nanocatalyst (Figure 3(A)) also represented narrow metal particle size distribution with smaller average particle size between 4 and 14 nm, which would provide maximum active sites for hydrogenation of DTBuB18C6 and resulted higher conversion (40 %) and larger initial rate constant (0.01 min–1).

4 Conclusion

3 wt% Rh/γ-Al2O3 catalyst synthesized by ME technique was found to be very active for the reduction of DTBuB18C6 to DTBuCH18C6. 40 % conversion with high selectivity towards CSC DTBuCH18C6 was achieved at 70 bar pressure but at comparatively lower temperature (100ºC) with 5 h of reaction time. Reaction mechanism and high distribution coefficient (KD) value supported high selectivity towards CSC DTBuCH18C6. Higher rate constant value (0.01 min–1) and lower activation energy (13.7 kJ mol–1) obtained from Arrhenius plot indicated better performance of the 3 wt% ME nanocatalyst compared to other catalyst.

References

1. Abashkin, V. M., Wester, D.W., Campbell, J.A., Grant, K.E., 1996. Radiation stability of cis-isomers of Dicyclohexano-18-crown-6. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 48, 463–472.10.1016/0969-806X(96)00012-6Suche in Google Scholar

2. Biacchi, A.J., Schaak, R.E., 2011. The solvent matters: kinetic versus thermodynamic shape control in the polyol synthesis of rhodium nanoparticles. ACS Nano 5, 8089–8099.10.1021/nn2026758Suche in Google Scholar

3. Bond, A.H., Barrans, R.E. Jr, Horwitz, E.P., 2006a. Improved purification of 4,4’(5’)-[Di-t-butyldicyclohexano]-18-crown-6.WO 03/043960A2.Suche in Google Scholar

4. Bond, A.H., Barrans, R.E. Jr, Horwitz, E.P., 2006b. Purification of 4,4’(5’)-[Di-t-butyldicyclohexano]-18-crown-6.US00709133B2.Suche in Google Scholar

5. Dietz, M.L., Felinto, C., Rhoads, S., Clapper, M., Finch, J.W., Hay, B.P., 1999. Comparison of column chromatographic and precipitation methods for the purification of a macrocyclic polyether extractant. Separation Science and Technology 34, 2943–295610.1081/SS-100100814Suche in Google Scholar

6. Galletti, A.M.R., Antonetti, C., Longo, I., Capannelli, G., Venezia, A.M., 2008. A novel microwave assisted process for the synthesis of nanostructured ruthenium catalysts active in the hydrogenation of phenol to cyclohexanone. Applied Catalalysis A 350, 46–52.10.1016/j.apcata.2008.07.044Suche in Google Scholar

7. Gao, J., Chen, S., Chen, J., 2012. Stereoselective reduction of dibenzo-18-crown-6 ether to dicyclohexano-18-crown-6ether catalyzed by ruthenium catalysts. Catalysis Communication 28, 27–31.10.1016/j.catcom.2012.08.019Suche in Google Scholar

8. Guerrero, M., Chau, N.T.T., Noel, S., Denicourt-Nowicki, A., Hapiot, F., Roucoux, A., Monflier, E., Philippot, K., 2013. About the use of rhodium nanoparticles in hydrogenation and hydroformylation reactions. Current Organic Chemistry 17, 364–399.10.2174/1385272811317040006Suche in Google Scholar

9. Hafizi, M., Abolghasemi, H., Milani, S.A., 1992. Solvent extraction of strontium from aqueous solution by crown ethers. Separation Science and Technology 32, 1050–1056.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Horwitz, E.P., Dietz, M.L., Fisher, D.E., 1991. SREX: A new process for the extraction and recovery of strontium from acidic nuclear waste streams. Solvent Extraction and Ion Exchange 9, 1–25.10.1080/07366299108918039Suche in Google Scholar

11. Horwitz, P.E., Dietz, M.L., 1992. Process for the recovery of strontium from acid solutions. US005100585A.Suche in Google Scholar

12. Jain, B.A., Vaidya, D.P., 2014. Kinetics of aqueous-phase hydrogenation of model bio-oil compounds over a Ru/C catalyst. Energy & Fuels 29, 361–368.10.1021/ef5018253Suche in Google Scholar

13. Kim, H., Khi, N.T., Yoon, J., Yang, H., Chae, Y., Baik, H., Lee, H., Sohn, J-H., Lee. K., 2013. Fabrication of hierarchical Rh nanostructures by understanding the growth kinetics of facet-controlled Rh nanocrystals. Chemical Communications 49, 2225–2227.10.1039/c3cc39294eSuche in Google Scholar

14. Králik, M., Turáková, M., Mačák, I., Wenchich, S., 2012. Catalytic hydrogenation of aromatic compounds in the liquid phase. Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data 6, 1074–1082.Suche in Google Scholar

15. Landre, P.D., Lemaire M., Richard, D., Gallezot, P., 1993. A stereoselective reduction of dibenzo-18-crown-6 ether to dicyclohexyl-18-crown-6 ether. Journal of Molecular Catalysis 78, 257–261.10.1016/0304-5102(93)87055-DSuche in Google Scholar

16. Landre, P.D., Richard, D., Draye, M., Gallezot, P., Lemaire, M., 1994. Colloidal rhodium: A new catalytic system for the reduction of Dibenzo-18-crown-6 Ether. Journal of Catalysis 147, 214–222.10.1006/jcat.1994.1132Suche in Google Scholar

17. Metaxas, K.C., Papayannakos, N.G., 2006. Kinetics and mass transfer of benzene hydrogenation in a trickle-bed reactor. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 45(21), 7110–7119.10.1021/ie060577aSuche in Google Scholar

18. Mohapatra P.K., Lakshmi, D.S., Manchanda, V.K., 2006. Diluent effect on Sr(II) extraction using using di-tert-butyl cyclohexano 18 crown 6 as the extractant and its correlation with transport data obtained from supported liquid membrane studies. Desalination 198, 166–172.10.1016/j.desal.2006.03.516Suche in Google Scholar

19. Mohapatra P.K., Pathak, P.N., Kelkar, A., Manchanda V.K., 2004. Novel polymer inclusion membrane containing a Macrocyclic ionophore for selective removal of strontium from nuclear water solution. New Journal of Chemistry 28, 1004–1009.10.1039/B305853KSuche in Google Scholar

20. Nandanwar, S.U., Chakraborty, M., Mukhopadhyay, S., Shenoy, K.T., 2013. Benzene hydrogenation over highly active monodisperse Ru/γ-Al2O3 nanocatalyst synthesized by (w/o) reverse microemulsion. Reaction Kinetics Mechanism Catalysis 108, 473–48910.1007/s11144-012-0526-1Suche in Google Scholar

21. Nandanwar, S.U., Chakraborty, M., Mukhopadhyay, S., Shenoy, K.T., 2011. Stability of ruthenium nanoparticle synthesized by solvothermal method. Crystal Research Technology 46, 393–399.10.1002/crat.201100025Suche in Google Scholar

22. Nandanwar, S.U., Dabbawala, A.A, Chakraborty, M., Bajaj, H.C., Mukhopadhyay, S., Shenoy, K.T. 2015. Partial hydrogenation of benzene to cyclohexene over Ru/γ-Al2O3 nanocatalyst via w/o microemulsion using boric acid and ethanolamine additives. Research on Chemical Intermediates, DOI 10.1007/s11164-015-2102–6.10.1007/s11164-015-2102-6Suche in Google Scholar

23. Patel, R.R., Barad, J.M., Nandanwar, S.U., Chakraborty, M., Dabbawala, A.A., Parikh, P.A., Bajaj, H.C., 2015. Cellulose supported ruthenium nanoclusters as an efficient and recyclable catalytic system for Benzene Hydrogenation under mild conditions. Kinetics and Catalysis 56, 173–180.10.1134/S002315841502007XSuche in Google Scholar

24. Salih, A.A. M., Li, Y., Fan, J., Yi, C., Yang, B., 2014. Preparation of novel membrane material 4’,4”(5”)-di-tert-butyldicyclohexyl-18-crown-6. Advanced Material Research 960–961, 73–77.10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.960-961.73Suche in Google Scholar

25. Suryawanshi, Y.R., Chakraborty, M., Jauhari, S., Mukhopadhyay, S., Shenoy, K.T., Shridharkrishna, R. 2013. Microwave irradiation solvothermal technique: an optimized protocol for size-control synthesis of Ru nanoparticles. Crystal Research Technology 48, 69–74.10.1002/crat.201200412Suche in Google Scholar

26. Suryawanshi, Y.R., Chakraborty, M., Jauhari, S., Mukhopadhyay, S., Shenoy, K.T., Sen, D., 2015. Selective Hydrogenation of Dibenzo-18-crown-6 ether over highly active monodisperse Ru/γ-Al2O3 nanocatalyst. Bulletin of Chemical Reaction Engineering & Catalysis 10, 23–29.10.9767/bcrec.10.1.7141.23-29Suche in Google Scholar

27. Wang, Y., Cui, X., Deng, Y., Shi, F., 2014. Catalytic hydrogenation of aromatic rings catalyzed by Pd/NiO. RSC Advances 4, 2779–2732.10.1039/C3RA45600ESuche in Google Scholar

©2017 by De Gruyter

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Bubble Trajectory in a Bubble Column Reactor using Combined Image Processing and Artificial Neural Network

- Non-linear Radiation Effects in Mixed Convection Stagnation Point Flow along a Vertically Stretching Surface

- Mixing Behaviors of Jets in Cross-Flow for Heat Recovery of Partial Oxidation Process

- Selective Hydrogenation of 4’,4”(5”)-Di-Tert-Butyldibenzo-18-Crown-6 Ether over Rh/γ-Al2O3 Nanocatalyst

- Titania-Loaded Coal Char as Catalyst in Oxidation of Styrene with Aqueous Hydrogen Peroxide

- A Study of the Soft-Sphere Model in Eulerian-Lagrangian Simulation of Gas-Liquid Flow

- Conceptual Approach in Multi-Objective Optimization of Packed Bed Membrane Reactor for Ethylene Epoxidation Using Real-coded Non-Dominating Sorting Genetic Algorithm NSGA-II

- Kinetics of Extraction of Tributyl phosphate (TBP) from Aqueous Feed in Single Stage Air-sparged Mixing Unit

- Viscous Dissipation Effects in Water Driven Carbon Nanotubes along a Stream Wise and Cross Flow Direction

- Evaluation of Mixing and Mixing Rate in a Multiple Spouted Bed by Image Processing Technique

- A Parametric Study of Biodiesel Production Under Ultrasounds

- Numerical Study of MHD Viscoelastic Fluid Flow with Binary Chemical Reaction and Arrhenius Activation Energy

- CFD Analysis and Design Optimization in a Curved Blade Impeller

- Bio-Oil Heavy Fraction as a Feedstock for Hydrogen Generation via Chemical Looping Process: Reactor Design and Hydrodynamic Analysis

- Upgrading of Heavy Oil in Supercritical Water using an Iron based Multicomponent Catalyst

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Bubble Trajectory in a Bubble Column Reactor using Combined Image Processing and Artificial Neural Network

- Non-linear Radiation Effects in Mixed Convection Stagnation Point Flow along a Vertically Stretching Surface

- Mixing Behaviors of Jets in Cross-Flow for Heat Recovery of Partial Oxidation Process

- Selective Hydrogenation of 4’,4”(5”)-Di-Tert-Butyldibenzo-18-Crown-6 Ether over Rh/γ-Al2O3 Nanocatalyst

- Titania-Loaded Coal Char as Catalyst in Oxidation of Styrene with Aqueous Hydrogen Peroxide

- A Study of the Soft-Sphere Model in Eulerian-Lagrangian Simulation of Gas-Liquid Flow

- Conceptual Approach in Multi-Objective Optimization of Packed Bed Membrane Reactor for Ethylene Epoxidation Using Real-coded Non-Dominating Sorting Genetic Algorithm NSGA-II

- Kinetics of Extraction of Tributyl phosphate (TBP) from Aqueous Feed in Single Stage Air-sparged Mixing Unit

- Viscous Dissipation Effects in Water Driven Carbon Nanotubes along a Stream Wise and Cross Flow Direction

- Evaluation of Mixing and Mixing Rate in a Multiple Spouted Bed by Image Processing Technique

- A Parametric Study of Biodiesel Production Under Ultrasounds

- Numerical Study of MHD Viscoelastic Fluid Flow with Binary Chemical Reaction and Arrhenius Activation Energy

- CFD Analysis and Design Optimization in a Curved Blade Impeller

- Bio-Oil Heavy Fraction as a Feedstock for Hydrogen Generation via Chemical Looping Process: Reactor Design and Hydrodynamic Analysis

- Upgrading of Heavy Oil in Supercritical Water using an Iron based Multicomponent Catalyst