Abstract

The effectiveness of Pl genes is known to be resistant to downy mildew (DM) disease affected by fungus Plasmopara halstedii in sunflower. In this study phenotypic analysis was performed using inoculation tests and genotypic analysis were carried out with three DM resistance genes Plarg, Pl13 and Pl8. A total of 69 simple sequence repeat markers and 241 F2 individuals derived from a cross of RHA-419 (R) x P6LC (S), RHA-419 (R) x CL (S), RHA-419 (R) x OL (S), RHA419 (R) x 9758R (S), HA-R5 (R) x P6LC (S) and HA89 (R) x P6LC (S) parental lines were used to identify resistant hybrids in sunflower. Results of SSR analysis using markers linked with downy mildew resistance genes (Plarg, Pl8 and Pl13) and downy mildew inoculation tests were evaluated together and ORS716 (for Plarg and Pl13), HA4011 (for Pl8) markers showed positive correlation with their phenotypic results. These results suggest that these markers are associated with DM resistance and they can be used successfully in marker-assisted selection for sunflower breeding programs specific for downy mildew resistance.

1 Introduction

The sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) is known as the most important crop for the oil industry. Sunflower downy mildew caused by the obligate biotroph Plasmopara halstedii (Farl.) Berl. & de Toni is regarded to be a very damaging leaf tissue disease and has spread to all the countries where sunflower production has been made. Downy mildew (DM) can induce yield loss up to 80% in sunflower production [1]. Pl (Pl1–Pl17, Pl21 and Plarg) downy mildew resistance genes discovered to date in sunflowers and for the source of the Pl genes, wild Helianthus annual species can be followed [2]. These Pl genes that are very effective against P. halstedii races have been mapped in different linkage groups of sunflower: The Pl1/Pl6 locus on linkage group LG8 [3, 4]; the Pl5/Pl8 and Pl21 loci on LG13 [5, 6, 7]; the Plarg locus on LG1 [8]; the Pl13, Pl14 and Pl16 loci on LG1 [89101112].

The main target of sunflower breeding programs is to improve of downy mildew resistance. However, emerging strains of P. halstedii challenge global sunflower production and this has resulted in susceptibility to certain downy mildew strains in many commercial hybrids [13]. Therefore, new hybrids of sunflower are sought that are resistant to DM. The most effective measure of controlling downy mildew is the use of available resistant hybrids. Determination of the resistance genes location in sunflower genome and facilitation of marker assisted introgression for elite germplasm have been supplied with genetic mapping of downy mildew resistance genes [11].

Molecular markers are crucial for understanding genome organization and provide important advantages in the means of development of new lines [14] and determination of differentiation between initial germplasm [15]. The development of molecular markers in sunflower is at an advanced level and different types of markers have been developed for marker-assisted selection (MAS) over the years. There are numerous different molecular markers available which can be used in sunflower breeding [16]. Pérez-Vich and Berry [17] described three different generations of markers in sunflower research: Firstly, anonymous deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) markers like RFLP (Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism), RAPD (Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA), AFLP (Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism) and genomic SSR (Simple Sequence Repeat) markers were developed [18192021222324]. Usage of several molecular markers combined with numerous linkage maps makes it possible to develop a hybrid line that provides required properties [25]. There are several linkage maps available to use for marker assisted selection programmes. Researchers completed the first linkage map of sunflower in 2002 [24] and this was improved by another research group in 2003 through usage of new recombinant inbred lines population with SSR markers [26]. Another research group accomplished the genetic mapping of the fertility restoration gene by using SSR and TRAP (Targeted Region Amplified Polymorphism) markers [27]. Molecular markers related to different downy mildew resistance genes have been identified by bulk segregant analysis methods [28]. Mapping studies completed by RFLP and RAPD markers for identification of Pl1 [29], STS (Sequence Tagged Site) markers for identification of Pl5/Pl8 cluster [6], and SSR markers for identification of Pl6 and Pl13 locus. The Pl13 could be a useful source of resistance to the four major races of downy mildew and can be successfully transferred to different genetic backgrounds [30]. The identified markers closely linked to downy mildew resistance are expected to greatly enhance the efficiency of breeding using MAS [9]. Another study showed that Plarg loci provide resistance all known Plasmopara halstedii races [29].

Novel sources of resistance genes and suitable sequence specific molecular markers need to be found to keep up with the new pathogenic strains. More studies will be needed to quantitatively demonstrate resistance to downy mildew. MAS could in this way be used for detecting both major and minor genes and would bring us closer to achieving sustainable resistance to Plasmopara halstedii. Two DM resistance genes, Plarg and Pl8, are highly effective against P. halstedii races in the USA [31].

The objective of this study is to determine resistant sunflower lines for downy mildew using Plarg, Pl13 and Pl8 genes which gain resistance to downy mildew. SSRs were employed for screening resistant and susceptible parental lines and their F2 populations. Results of this study will permit an early selection of downy mildew resistant genotypes without inoculation and symptom detection as well as providing important knowledge for the development of new sunflower lines which are region specific.

2 Experimental Procedures

2.1 Plant Materials

DM-resistant parents RHA-419 (restorer oilseed sunflower which has Plarg resistance gene for downy mildew released by the USDA-ARS and the North Dakota Agricultural Experiment Station, Fargo, ND, USA), HA-R5 (restorer oilseed sunflower which has Pl13 resistance gene for downy mildew released by the USDA-ARS and the North Dakota Agricultural Experiment Station, Fargo, ND, USA), HA89 (oil seed sunflower which is susceptible for downy mildew released by the USDA-ARS and the North Dakota Agricultural Experiment Station, Fargo, ND, USA), DM-susceptible parents P6LC (resistant cultivar to IMI, Orobanche cumana, and downy mildew, Pl6 or Pl8), CL (IMI resistant and high oleic cultivar), 9758R (restorer oilseed sunflower which is susceptible for downy mildew released by Trakya Agricultural Research Institute, Edirne, TURKEY), OL (IMI resistant and high oleic cultivar) and 241 F2 populations from the cross of the DM-resistant and susceptible parents (Table 1) were used for screening for resistance to downy mildew.

Pl genes, parental lines and number of F2 individuals used in this study.

| Gene | Parental Lines | No. of F2 |

|---|---|---|

| Plarg(LG1) | RHA-419 x P6LC | 39 |

| Plarg(LG1) | RHA-419 x CL | 23 |

| Plarg(LG1) | RHA-419 x OL | 26 |

| Plarg(LG1) | RHA-419 x 9758R | 102 |

| Pl13(LG1) | HA-R5 x P6LC | 30 |

| PL8(LG13) | HA89 x P6LC | 23 |

RHA-419: Resistant

HA89: Resistant

HA-R5: Resistant

9758R: Susceptible

OL: Susceptible

P6LC: Susceptible

CL: Susceptible

The young leaf tissues of the Helianthus annuus L. species provided by Republic of Turkey Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock General Directorate of Agricultural Research and Policy, Trakya Agricultural Research Institute, Edirne, Turkey, have been used as plant material.

2.2 Downy mildew inoculation and phenotyping

Phenotypic screening for downy mildew was performed with inoculation tests in 10 replicates. Spores of different races of P. halstedii were cultured on the appropriate susceptible sunflower variety, and then a sporangium suspension was prepared with spores. Spore concentration was adjusted to 30.000 sporangia/ml. For sunflower seed disinfection, seeds were soaked in 1% NaClO suspension for 3 minutes, then were washed in distilled water, sunflower seeds were put in the growth chamber (24-28°C) to germinate until 2–5 mm. rootless were formed. Germinated seeds were incubated in the sporangium suspension for 4 hours at 18°C . Inoculated seedlings were planted in plastic flats or pots filled with a sand/perlite mixture (3:2, v/v). The growing condition was optimum at 24°C temperature and a 12-14 hr photoperiod illuminated with warm-white, high pressure mercury lamps (HGLM-400, Tungsram) to provide the plants with a light intensity of about 12.000 lux. After 8-10 days, when the first true leaves were formed, seedlings were placed in 100% humid, 16-17°C growth chamber for 48 hours. From each plant three segments of about 1 cm were excised, one each from the lower hypocotyl, the upper hypocotyl and the lower epicotyl. These were washed thoroughly with sterile distilled water, placed in Petri dishes lined with sterile moist filter paper and incubated at 18°C for 48 h in the dark to induce sporulation. Subsequently, white mildew spores could be seen under the cotyledon leaves of sensitive plants. Each plant infection level was assessed as a cotyledon/leaf surface covered with zoosporangiophores using a scale ranging from 0-3 [32] where 0: no sporulation, 1: sparse sporulation, 2: less than 50% of cotyledon/leaf area covered, and 3: more than 50% of cotyledon/leaf surface covered with zoosporangiophores.

2.3 DNA extraction and SSR Analysis

Leaf samples were harvested at seedling stage for DNA isolation and SSR analysis. 50-100 mg of plant young leaf tissues were homogenized by using a RetchMM400 mixer mill with liquid nitrogen and genomic DNA of the plants was isolated according to the CTAB method [33], the DNA quantity and quality were determined using a Qubit® 2.0 fluorometer.

A total of 69 SSR markers (12 markers for Plarg, 20 markers for Pl13, 37 markers for Pl8) were screened which showed linkage to the downy mildew resistance gene to identify polymorphisms between the parents (Table 2).

The primer sequences of the SSR markers linked to the sunflower downy mildew resistance genes Plarg, Pl13 and Pl8.

| Gene | SSR Marker | Forward Primer (5'-3') | ReversePrimer (5'-3') | Gene | SSR Marker | Forward Primer (5'-3') | ReversePrimer (5'-3') |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plarg | HT324 | ggC CAC CAC AAC AAC ATA AAT C | ATC AgA ATA TCC AAC gCA gCA A | Pl8 | ORS200 | ACT CTT gAT TgA ATg ATg CTC C | CgC ACT gCC TTA AAC CCT C |

| HT446 | CgT ATT gTC TAT ggT Cgg TgT TT | AAT CAA Tgg gAA gCT ggA TTT C | 0RS879 | CTC Cgg TTg CTg TTg ATg TCT | gAA CCT CCC TTT gTC TgC ATA TC | ||

| HT722 | CgT ATT gTC TAT ggT Cgg TgT TT | AAT CAA Tgg gAA gCT ggA TTT | ORS1277 | ATg gCT AAC ATT CAA gAg CAC CT | TTg CgA TAT AgC gAT TTA TgT gA | ||

| ORS371 | CAC ACC ACC AAA CAT CAA CC | ggT gCC TTC TCT TCC TTg Tg | ORS244 | Agg TgA ATC AAC gAg TgA ATg g | CAC CAC CAC CgC CgT CTC | ||

| ORS503 | AAC CAC ACA ACA CAg gCA AgA | TgA ACC TTC AAA CTT gCA ATC A | ORS596 | CAT gAg ggC ATT CTT gTC ATT | TgC gAT TAT TCT Agg AAg gTC A | ||

| ORS509 | CAA CgA AAA gAC AgA ATC gAA A | CCg ggA ATT TTA CAA ggT gA | ORS707 | gCA gTC AAT TCg TAg CAT Cg | gCT gAA gCT gAA gAC AgA TCC | ||

| ORS543 | CCA AgT TTC AgT TAC AAT CCA TgA | gggT CAT TAg gAg TTT ggg ATC A | ORS730 | CAT gTT Agg TTC AAg ggC ATT T | gCC AAC TgA TgC AAA TCT gA | ||

| ORS610 | Agg AAg CgA AAC gAg gAA gT | TTg TgA CCT TCT CCC TgC TC | ORS976 | AAA TTA CAA CCT CCA CAC CTT AT | CTT TTg TAT TCA AgC ACT AAT CA | ||

| ORS716 | CCC CAC AAC CCA TAg CCT AA | gAA CTA ACC gCC ATC CAA gA | ORS215 | CCT CTg CTg ATT gAA Tgg ATT g | Tgg TTC TCA CCA gCA gTT TAg g | ||

| ORS959 | CCg CTA AgT ATA AAC CgC CTA TT | CgT CCT CTT CgC ATC AAT CTT AT | ORS317 | ggT CgT ATg CTT AAT TCT TTC TCT | TTT ggC AgT TTg gTg gCT TA | ||

| ORS1182-1 | ggC gAT AAT AgA TgC gAC ACT C | TCT gTG CCA TAC CAC TTT ATT Cg | ORS224 | AAC CAA AgC gCT gAA gAA ATC | Tgg ACT AAC TAC CAg AAg CTA C | ||

| ORS1182-2 | TCT TCT gAT TgT AAg Cgg TgT TC | TgT CAT gTT CTC TAC CgA gCT TT | ORS1179 | AAA Cgg gAA gCA AgA ATA gAA CA | gAT TCg gAg CTg TTA ggA ggT Ag | ||

| Pl13 | 0RS822 | AAA CAA ACC TTT ggA CgA AAC TC | TgC CAT CTg TCA TCA gCT AC | ORS536 | gAA ATA ggA ggg gAT CTT ACC g | gCg gAg AgA AAg ACg AAg Ag | |

| 0RS598 | ATA gTC CCT gAC gTg gAT gg | CCA AAT gTg Agg Tgg gAg AA | 0RS781 | gAT gTg gAg gAg AgA ggg TgT | gTC AAC CCA TgA CCC AAA CC | ||

| 0RS222 | AAT TgA gCT TCA ATT Tgg Tgg A | ATC CgT gCg AAT TAA CCA TCA g | ORS1056 | ggT gAA ATC TAg TCA TgT gCC TTA | gTg gTg ggT TTA ATg gTC TTT gT | ||

| 0RS474 | gTgCTCgggATTgATTCTgT | TgC ACC TTT gTT Tgg ATC TTC | ORS995 | CAT gCT TTC TAg gAT ggT CAg TT | TgT ATg Tgg Agg CCA ACA AgT AT | ||

| ORS605 | ACg gAg CAA AgT TTC gAg gT | CgC gTg ATg TgA CgA TTA TT | ORS511 | Cgg gTT gCg AgT AAC Agg TA | Tgg CTC AgA TTA AgT TCA CAC Ag | ||

| 0RS462 | AAg CTA ACA AAC ggT CTT CAC A | ACA TTg ATT CTC gCg gTT CT | ORS1030 | CCT TTg ATg TAg TTA Agg AAg TTg Tg | CgA TCA ATT TAT ATg ACC gAA TTA CC | ||

| ORS803 | ACC gCC gCA TAT AAA ggA gT | TTC CCA CCC ATC TTC ATC TC | ORS799 | ACT CCC TCC CAT TCT CgT CT | TCC AgC AAg TCA gCA ACA AC | ||

| 0RS718 | ATg CAA CAC CCg AAT CAA Ag | CAC TTT ACg CAC ACC AAA CC | ORS191 | ACT gCg TTT gTg ATT ACT ggT g | CAT gCA CTg AAg ACA TAC ACC C | ||

| 0RS965 | CAC TTT ACg CAC ACC AAA CC | TTg gAT TAC CTT ggA TAg TCA gC | ORS581 | ATC TTA Tgg TCC gCA CAA gC | TCT CgT ATA ACg TgC CCT gA | ||

| 0RS728 | CCA ACC TCT gAA TgA TAC TTg TgA C | CTC CAT AgC AAC CAC CTg AAA | ORS630 | gCA CgA CCC ggA TAT gTA AC | TgT gCT gAg gAT gAT ATg CAg | ||

| ORS662 | CCT TTA CAA ACg AAg CAC AAT TC | Cgg gTT ggA TAT ggA gTC AA | ORS316 | gAg ATT TgA gCT TCg TgT TgC | Tgg CgT CTT CAT AgC ATC Ag | ||

| 0RS675 | Cgg CTA AgA gAA Agg gAg AgA | ATC TgA AAT Cgg ACA AgA TTC A | HA4011 | ACT TCT ACC CTC CCC TTC TT | CTg TAC ACg TgC TgC TTT Ag | ||

| 0RS716 | CCC CAC AAC CCA TAg CCT AA | gAA CTA ACC gCC ATC CAA gA | HA1626 | gAT gTT ACA CgT TAg CAA Cg | gAA CTC AgC CTA AAA gTC | ||

| ORS970 | gTC ATA Tgg ATC ATg AAA ATg TTA gTg | TTg TgA TTT AAC TAT CAg gTg ACA Tg | HA3417 | TAA TTg ATT ggg ggT AAA Tg | TAT gAT TTg gTg TgC TCA gA | ||

| 0RS425 | CCC TTg gTC ATg TgT TgT gT | gCT CTC TCT CTT Cgg gTT CAV | HA2598 | TTC TCA TgT gCT CAA AgA Tg | CCT gAA CCC TTT TgT TTC TT | ||

| 0RS552 | CCA TCC CTT CCC TCT CTT TC | gTg gCT ggT ATC TCA TCA CC | HA3330 | ggC TgA gTA AAT gCC AAA TAC gg | ggT TgT TgA TTA CAA gCT CTC C | ||

| HA4090 | gCC ATg ATT ggC TAA ggTTCg | TgC gTT ACC gAC AAC ACA Agg | HA4208 | CCC gCA ATT gAA TAC gCg ACA TC | CAT CTC gTT gCC CgT TAA CTA TC | ||

| HA77 | TgT AAT CTg TAT CAC TTC CAC C | gTT gTT CTg TTA ggT CgT TCC g | HANT8R1 | gCC CAA AAT TgA AAg AAA ggT gTg | ggC gAA ATT ggT TCC CgT gAg TCg | ||

| 0RS365 | CgA ggC AAA ggg TgT CTA AA | gAA gCg AAg gAA Tgg Tgg TT | HANT8R3 | TAg TTA ACC ATg gCT gAA ACC gCT g | TTT gAA AgA TAA gTT CgC CTC TCg | ||

| ORS1008 | CAT gAg ggC ATT CTT gTC ATT T | gAT CAC CTT CAC TAT CCA CAA CC | HANT8R4 | ggT TTg AAg ATA TgT CgA gTT ggg | CCC AAC TCg ACA TAT CTT CAA ACC | ||

| Pl8 | 0RS673 | ggC ATg TTC TCA CCg TTC AT | Tgg TgC TAC TCC ATC CTT gA | HANT8R5 | TAg TTA ACC ATg gCT gAA ACC gCT g | CCC CAT ATT gAC AAA gAg TTg Agg | |

| 0RS534 | gCA gCg AAA TAg gAA AAA Cg | TCC AAA CTC TCT CCC CCT CT | HANT8R6 | TAg TTA ACC ATg gCT gAA ACC gCT g | CgT CTC Tgg TAg ATC gTT CAC CTT | ||

| ORS1009 | CCA TTT ACC CTT TAC ACe eAT CT | TAT gTA Tee TCg CCA ATT TAC CA |

The PCR reagents mixed in a master mix 2X solution, consisting of dH2O, 2X Taq buffer, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dNTP mix, Taq Polymerase 0,054 U/μl. Then master mix 2X solution is diluted into master mix X solution with water and primer addition to final volume of 23 μl per sample. The final reaction tube content has been calibrated as 1X Taq Buffer, 2,5 mM MgCl2, 2,5 mM dNTP, 0,8 mM primer, 0,027 U/μl Taq polimerase and 4 ng/μl genomic DNA. The PCR amplification profile included a hot start at 94°C for 3 min followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 59-62°C for 1 min and extension at 72°C for 1 min with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Amplified products were run on 2% agarose gel. DNA isolation and SSR studies were performed in 3 replicates.

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animals use.

3 Results

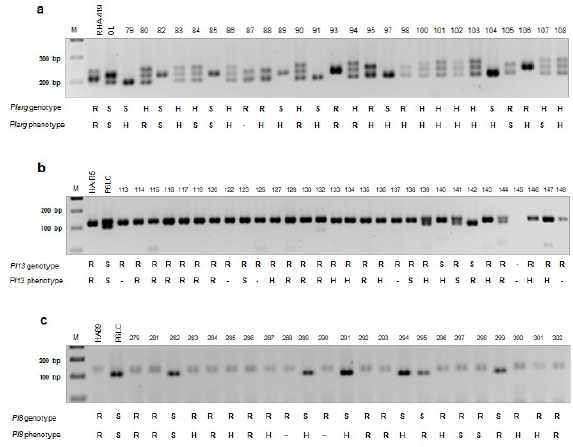

Results of the downy mildew resistance test for phenotyping of the 241 F2 plants derived from RHA-419 x P6LC, RHA-419 x CL, RHA-419 x OL, RHA419 x 9758R, HA-R5 x P6LC, HA89 x P6LC parental lines were determined as homozygous resistant/susceptible and heterozygous samples numerically. These results were shown with genotyping data obtained using polymorphic markers together (Table 3). Parental (RHA419-resistant x 9758R-susceptible) polymorphism was determined by 2 SSRs (ORS610, ORS716) and different combinations of crosses (RHA419-resistant x P6LC-susceptible; RHA419-resistant x CL-susceptible; RHA419-resistant x OL-susceptible) were resulted with polymorphic pattern by 1 SSR (ORS716) out of 12 SSRs for Plarg gene. Polymorphism was determined between HAR5 (resistant) and P6LC (susceptible) parental lines by 7 SSRs (ORS822, ORS803, ORS728, ORS716, HA4090, HA77, ORS1008) out of 20 SSRs for Pl13 gene. Amplification with five SSRs (ORS707, ORS730, ORS215, ORS316, and HA4011) out of 37 SSRs produced polymorphic pattern between HA89 (resistant) and P6LC (susceptible) for Pl8 gene. As a result, fourteen SSR markers out of 69 were selected for screening of F2 individuals belong the crosses mentioned above regarding the genetic linkage to Plasmopara resistance genes namely Plarg, Pl13 and Pl8. For this purpose, SSR analysis of 241 F2 plants derived from the cross of RHA-419 x P6LC, RHA-419 x CL, RHA-419 x OL, RHA419 x 9758R, HA-R5 x P6LC was conducted using fourteen polymorphic SSR markers. SSR results of ORS716 (Plarg) for RHA-419 x OL cross and their 26 F2; ORS716 (Pl13) for HA-R5 x P6LC cross and their 30 F2; HA4011 (Pl8) for HA89 x P6LC cross and their 23 F2 together with their phenotyping results were shown in Figure 1.

Genotypic results of polymorphic markers and phenotypic results of inoculation tests.

| Gene | Parental Lines | Polymorphic Markers | Genotypic Results | Phenotypic Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plarg(LG1) | RHA419 x 9758R | ORS610 | R:62 S:27 H:1 | R:63 S:10 H:29 |

| (102 F) 2 | ORS716 | R:65 S:23 | R:63 S:10 H:29 | |

| RHA-419 x CL | ORS716 | R:5 S:6 H:7 | R:3 S:2 H:17 | |

| (23 F2) | ||||

| RHA-419 x OL | R:7 S:7 H:12 | R:4 S:5 H:16 | ||

| (26 F2) | ||||

| RHA-419 x P64LC53 | R:3 S:27 H:7 | R:4 S:5 H:25 | ||

| (39 F2) | ||||

| Pl13(LG1) | HA-R5 x P6LC | ORS822 | R:6 S:24 | R:12 S:3 H:9 |

| (30 F2) | ORS803 | R:13 S:15 | ||

| ORS728 | R:18 S:12 | |||

| ORS716 | R:27 S:3 | |||

| HA4090 | R: 6 S:22 | |||

| HA77 | R:28 S:2 | |||

| ORS1008 | R:8 S:21 | |||

| Pl8(LG13) | HA89 x P6LC | ORS707 | R:1 S:22 | R:9 S:3 H:9 |

| (23 F2) | ORS730 | R:9 S:14 | ||

| ORS215 | R:0 S:23 | |||

| ORS316 | R:10 S:13 | |||

| HA4011 | R:17 S:6 |

R: Resistant

S: Susceptible

H: Heterozygous

PCR amplifications of SSR markers and phenotypic results (a)ORS716 (Plarg - RHA-419 x OlL and 26 F2) (b)ORS716 (Pl13 - HA-R5 x P6LC and 30 F2) (c)HA4011 (Pl8 - HA89 x P6LC and 23 F2) M: 100 bp.

3.1 Correlation of Genotypic and Phenotypic Evaluation

When the results of genotyping and phenotyping were evaluated together, ORS716 (for Plarg and Pl13), HA4011 (for Pl8) markers showed positive correlation with their phenotypic results (Figure 1). For Plarg resistance in breeding population of RHA419 (resistant) x OL (susceptible) cross, one F2 individual (#93) was scored as resistant and two F2 individuals (#82, #85) were scored as susceptible by both phenotypic and genotypic evaluation while 7 individuals (#83, #86, #100, #101, #102, #103, #108) were scored as heterozygous both phenotypically and genotypically. Phenotypically nine heterozygous F2 individuals were segregated as 4 resistant (#88, #95, #98, #106) and 5 susceptible individuals (#79, #89, #91, #97, #104) by ORS716 marker (Figure 1a). For Pl13 resistance in breeding population of HA-R5 (resistant) x P6LC (susceptible) cross, eleven F2 individuals (#114, #115, #116, #117, #119, #120, #128, #130, #132, #135, # 144) were scored as resistant by both phenotypic and genotypic evaluation while eight F2 individuals (#127, #133, #134, #136, #139, #143, #146, #147) were heterozygous phenotypically but they were scored as resistant by genotypic data. In the frame of these results, ORS716 SSR marker was found very effective for both Plarg and Pl13 genes to identify the downy mildew resistance in sunflower (Figure 1b). For Pl8 resistance in breeding population of HA89 (resistant) x P6LC (susceptible) cross, seven F2 individuals (#279, #281, #284, #288, #292, #293, #302) were scored as resistant by both phenotypic and genotypic evaluation while six F2 individuals (#283, #285, #287, #296, #300, #301) were heterozygous phenotypically but they were scored as resistant by genotypic data by HA4011 marker. The one individual (#282) was scored as susceptible by both phenotypic scoring and HA4011 marker (Figure 1c).

4 Discussion

Downy mildew is an important disease which causes serious yield losses in sunflower cultivation both in Turkey and worldwide. The most promising and powerful solution for resistance to downy mildew is the development of new sunflower lines that show genetic resistance to Plasmopara halstedii races.

Development of new lines by conventional breeding is a question of time and money. Therefore, integration of marker assisted selection to conventional breeding applications is essential. By establishment of a relationship between genes providing resistance to an important trait like resistance to downy mildew, sensitivity and reliability of the breeding programs can be increased. Marker assisted selection methods make breeders able to determine resistance/sensitivity of the plant in early stages of the cultivation and also allows the testing of more than one plant in a shorter period of time.

Classical genetic analysis by phenotyping segregating populations elucidated that Plarg is unlinked to the previous known major resistance loci Pl1, Pl2, Pl5, Pl6, Pl7 and Pl8 which are mainly used in breeding material [34, 35]. There are markers for several Pl genes, including Pl8, Pl13 and Plarg, which are still effective against all strains of P. halstedii [5,6,891011,13].

Dußle et al. [8], studied 180 SSRs and they found 66 polymorphic markers between Arg1575-2xCmsHA342. Twelve polymorphic SSRs linked to the Plasmopara resistance gene Plarg were identified with the analysis of these 66 SSRs. These SSRs mapped on the same linkage group (LG1), as based on the map of Yu et al. [26], spanning a maximum distance of 9.3 cM. Two fertility restorer lines RHA-419 and RHA-420 were registered by Miller et al. [36] (derived from the cross RHA-373×Arg1575-2) which expressing resistance against Plasmopara races 300, 700, 730, and 770. Combination of Plarg with other known Pl resistance loci should provide a multigenic resistance for sunflower cultivars against new plasmopara epidemics. Radwan et al. [37] reported the association between Pl8 resistance system and hypersensitive response in the hypocotyl. Also, they observed a hypersensitive response for Plarg. Therefore, strategies have to be worked out to conserve the broad function of the resistance gene Plarg. Till now, Pl8 and Plarg confer resistance against all downy mildew races but Pl6 provides resistance to the races 304 and 314 [38]. A couple of studies were discussed how to extend the durability of Pl loci. Combination of monogenic Pl loci and quantitative resistance against downy mildew were proposed by Sakr [39], Tourvieille de Labrouhe et al. [40] and Vear et al. [41]. McDonald and Linde [42] recommended a pyramiding major resistance gene in hybrid cultivars or breeding cultivar mixtures including genotypes with diversified major resistance genes.

More information of the biochemistry and functional basis of resistance was needed for the implementation of these strategies. Mulpuri et al. [9], screened 116 F2 belong to HA-R5 x HA-821 sunflower parent combination using 500 SSR markers. They reported that 42.6% polymorphism determined between HA-R5 and HA-821 from 213 polymorphic bands. Using these polymorphic primers, they showed the association with the downy mildew resistance phenotype on S- and R- bulks and F2 population with identification of 7 SSR markers, including 1 marker from LG10 (ORS1008) and 6 markers from LG1 (ORS965-1, ORS965-2, ORS959, ORS371, ORS605, ORS716). ORS1008 and ORS965 markers were found close to the Pl13 locus comparing with the other markers. Similar to this study ORS1008 marker of Pl13 gene showed polymorphism between HA-R5 x P6LC. 30 F2 from this parental combination were screened using ORS1008 marker and showed 26,6% resistance. Qi et al. [43], identified 361 polymorphic markers from 849 SSR markers using HA-234 and HA-458 parents include a total of 17 linkage groups (LGs). Their BSA revealed the polymorphism that was produced by ORS1197 and ORS963 SSR markers on LG4 of sunflower genomes between the S- and R- bulks and they reported that all homozygous susceptible plants in S-bulk revealed the HA-234 allele, but 10 homozygous resistant plants in R-bulk showed the HA-458 allele. Qi et al. [2], studied with a new dominant downy mildew resistance gene (Pl18) transferred from wild Helianthus argophyllus (PI494573) into cultivated sunflower was mapped to LG2 of the sunflower genome by BSA using 869 SSR markers and they showed the validation of the resistance single gene inheritance with phenotyping 142 BC1F2:3 families derived from the cross of HA89 and H. agophyllus. The Plarg gene gives resistance in effect to the P. halstedii strains detected up to now in the USA and France and Pl8 gene gives resistance (98%) to the P. halstedii isolates [13, 44, 45]. However, P. halstedii races that appear new in North America and France have overcome various DM resistance genes commonly used in sunflowers, such as Pl6 (from H. annuus) and Pl7 (from H. praecox), although they were published simultaneously as Pl8 [13, 44]. The P. halstedii populations are much active and constantly alter the virulence system, thus continuing the search and experiment of the downy mildew resistance genes introgression from H. argophyllus and other wild species.

In this study SSR markers were employed to identify resistance linked with genes Plarg, Pl8 and Pl13 in 241 F2 progeny from the cross RHA-419 x P6LC, RHA-419 x CL, RHA-419 x OL, RHA419 x 9758R, HA-R5 x P6LC combination of resistant and susceptible parent lines. As a result of screening the markers on sunflower crosses, 14 SSRs produced polymorphic pattern between resistant and susceptible parents. Two markers (ORS716 and HA4011) showed high similarity results with resistance test results when compared with others markers used in this study. This correlation between genotypic and phenotypic results revealed that these markers could be very useful for marker-assisted selection studies focused on downy mildew resistance in sunflowers.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TUBITAK) (Project No: 3150030) and Marmara University Research Foundation (BAPKO) (Project No:FEN-A-090414-0088).

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Molinero-Ruiz ML, Melero-Vara JM, Dominguez J, Inheritance of resistance to two races of sunflower downy mildew (Plasmopara halstedii) in two Helianthus annuus L. lines, Euphytica, 2003;131:47–51.10.1023/A:1023063726185Search in Google Scholar

[2] Qi LL, Foley ME, Cai XW, Gulya TJ, Genetics and mapping of a novel downy mildew resistance gene, Pl18 introgressed from wild Helianthus argophyllus into cultivated sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.), Theor Appl Genet, 2016;129(4):741-752.10.1007/s00122-015-2662-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Gedil MA, Slabaugh MB, Berry S, Segers B, Peleman J, Michelmore R, et al. Candidate disease resistance genes in sunflower cloned using conserved nucleotide binding site motifs: genetic mapping and linkage to downy mildew resistance gene Pl1 gene. Genome, 2001;44:205–212.10.1139/gen-44-2-205Search in Google Scholar

[4] Bouzidi MF, Badaoui S, Cambon F, Vear F, Tourvielle De Labrouhe D, Nicolas P, et al. Molecular analysis of a major locus for resistance to downy mildew in sunflower with specific PCR-based markers, Theor Appl Genet, 2002;104:592–600.10.1007/s00122-001-0790-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Radwan O, Bouzidi MF, Vear F, Philippon J, de Tourvieille Labrouhe D, Nicolas P et al. Identification of non-TIR-NBSLRR markers linked to the Pl5/Pl8 locus for resistance to downy mildew in sunflower, Theor Appl Genet, 2003;106:1438–144.10.1007/s00122-003-1196-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Radwan O, Bouzidi MF, Nicolas P, Mouzeyar S. Development of PCR markers for the Pl5Pl8 locus for resistance to Plasmopara halstedii in sunflower, Helianthus annuus L. from complete CC-NBS-LRR sequences, Theor Appl Genet, 2004;109:176–185.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Vincourt P, As-sadi F, Bordat A, Langlade NB, Gouzy J, Pouilly N, et al. Consensus mapping of major resistance genes and independent QTL for quantitative resistance to sunflower downy mildew, Theor Appl Genet, 2012;125: 909–920.10.1007/s00122-012-1882-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Dußle CM, Hahn V, Knapp SJ, Bauer E. PlArg from Helianthus argophyllus is unlinked to other known downy mildew resistance genes in sunflower, Theor Appl Genet, 2004;109:1083–1086.10.1007/s00122-004-1722-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Mulpuri S, Liu Z, Feng J, Gulya TJ, Jan CC. Inheritance and molecular mapping of a downy mildew resistance gene, Pl13 in cultivated sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.), Theor Appl Genet, 2009;119:795–803.10.1007/s00122-009-1089-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Wieckhorst S, Bachlava E, Dußle CM, Tang S, Gao W, Saski C, et al. Fine mapping of the sunflower resistance locus PlARG introduced from the wild species Helianthus argophyllus Theor Appl Genet, 2010;121(8):1633-1644.10.1007/s00122-010-1416-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Bachlava E, Radwan OE, Abratti G, Tang S, Gao W, Heesacker AF, et al. Downy mildew (Pl8 and Pl14) and rust (RAdv) resistance genes reside in close proximity to tandemly duplicated clusters of non-TIR-like NBS-LRR-encoding genes on sunflower chromosomes 1 and 13, Theor Appl Genet, 2011;122:1211–1221.10.1007/s00122-010-1525-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Liu Z, Gulya TJ, Seiler GJ, Vick BA, Jan CC. Molecular mapping of the Pl16 downy mildew resistance gene from HA-R4 to facilitate marker-assisted selection in sunflower, Theor Appl Genet, 2012;125:121–131.10.1007/s00122-012-1820-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Gulya TJ, Markell S, McMullen M, Harveson B, Osborne L. New virulent races of downy mildew: distribution, status of DM resistant hybrids, and USDA sources of resistance. In: Proceedings of 33th Sunflower Research Forum, Fargo ND, 12–13 Jan 2011.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Hvarleva T, Tarpomanova I, Hristova-Cherbadji M, Hristov M, Bakalova A, Atanassov A, et al., Toward marker assisted selection for fungal disease resistance in sunflower. Utilization of H. bolanderi as a source af resistance to downy mildew, Biotechnol. and Biotechnol., 2009;23(4):1427-1430.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Santalla M, Power JB, Davey MR. Genetic diversity in mung bean germplasm releaved by RAPD markers, Plant Breeding, 1998;117:473-478.10.1111/j.1439-0523.1998.tb01976.xSearch in Google Scholar

[16] Wieckhorst S. Characterization of the PlARG locus mediating resistance against Plasmopara halstedii in sunflower, Doctoral dissertation, Technische Universität München, 2012.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Pérez-Vich B, Berry ST, Molecular Breeding. In: Hu J, Seiler G, Kole C (Eds.), Genetics, Genomics and Breeding of Sunflower CRC Press, Pullman, Washington, USA, pp 221-252, 2010.10.1201/b10192-8Search in Google Scholar

[18] Al-Chaarani GR, Roustaee A, Gentzbittel L, Mokrani L, Barrault G, Dechamp- Guillaume G, et al. A QTL analysis of sunflower partial resistance to downy mildew (Plasmopara halstedii) and black stem (Phoma macdonaldii) by the use of recombinant inbred lines (RILs), Theor Appl Genet, 2002;104:490-496.10.1007/s001220100742Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Berry ST, Leon AJ, Hanfrey CC, Challis P, Burkholz A, Barnes SR, et al. Molecular marker analysis of Helianthus annuus L. 2. Construction of an RFLP linkage map for cultivated sunflower, Theor Appl Genet, 1995;91:195-199.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Gentzbittel L, Vear F, Zhang YX, Bervillé A, Nicolas P. Development of a consensus linkage RFLP map of cultivated sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.), Theor Appl Genet, 1995;90:1079-1086.10.1007/BF00222925Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Lawson WR, Goulter KC, Henry RJ, Kong GA, Kochman JK. Marker assisted selection for two rust resistance genes in sunflower, Mol Breeding, 1998;4:227-234.10.1023/A:1009667112088Search in Google Scholar

[22] Lu YH, Melero-Vara JM, Garcia-Tejada JA, Blanchard P. Development of SCAR markers linked to the gene Or5 conferring resistance to broomrape (Orobanche cumana Wallr.) in sunflower, Theor Appl Genet, 2000;100:625-632.10.1007/s001220050083Search in Google Scholar

[23] Quagliaro G, Vischi M, Tyrka M, Olivieri AM. Identification of wild and cultivated sunflower for breeding purposes by AFLP markers, J Hered, 2001;92:38-42.10.1093/jhered/92.1.38Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Tang S, Yu JK, Slabaugh MB, Shintani DK, Knapp SJ. Simple sequence repeat map of the sunflower genome, Theor Appl Genet, 2002;105:1124-136.10.1007/s00122-002-0989-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Knapp SJ, Berry ST, Rieseberg LH. Genetic mapping in sunflowers, In DNA-Based Markers in Plants, Springer Netherlands, 2001, pp 379-403.10.1007/978-94-015-9815-6_22Search in Google Scholar

[26] Yu JK, Tang S, Slabaugh MB, Heesacker A, Cole G, Herring M, et al. Towards a saturated molecular genetic linkage map for cultivated sunflower, Crop Sci., 2003, 43, 367–387.10.2135/cropsci2003.3670Search in Google Scholar

[27] Yue B, Vick BA, Cai X, Hu J. Genetic mapping for the Rf1 (fertility restoration) gene in sunflower Helianthus annuus L.) by SSR and TRAP markers, Plant Breeding, 2010;129:24–28.10.1111/j.1439-0523.2009.01661.xSearch in Google Scholar

[28] Michelmore RW, Paran I, Kesseli RV. Identification of markers linked to disease resistance genes by bulked segregant analysis: A rapid method to detect markers in specific genomic regions by using segregating populations, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 1991;88:9828–9832.10.1073/pnas.88.21.9828Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Mouzeyar S, Roeckel-Drevet P, Gentzbittel L, Philippon J, Tourvieille De Labrouhe D, et al. RFLP and RAPD mapping of the sunflower Pl1 locus for resistance to Plasmopara halstedii race 1, Theor Appl Genet, 1995;91:733–737.10.1007/BF00220951Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Gulya TJ, Marek LF, Gavrilova V, In: Proc. of the Int. Symposium “Sunflower Breeding on Resistance to Diseases”, Krasnodart Russia. pp.7, 2010.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Qi LL, Talukder ZI, Hulke BS, Foley ME. Development and dissection of diagnostic SNP markers for the downy mildew resistance genes PlArg and Pl8 and maker-assisted gene pyramiding in sunflower Helianthus annuus L.), Mol Genet Genomics, 2017:1-13.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Oros G, Virányi F. Glasshouse evaluation of fungicides for the control of sunflower downy mildew (Plasmopara halstedii) Ann Appl Biol, 1987;110(1):53-63.10.1111/j.1744-7348.1987.tb03232.xSearch in Google Scholar

[33] Doyle JJ, Doyle JL. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue, Phytochem. Bull., 1987;19:11-15.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Röcher T. Molekular genetische Untersuchungen zur Resistenz der Sonnenblume Helianthus annuus L.) gegen den Erreger des Falschen Mehltaus Plasmopara halstedii Dissertation, Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen, Gießen, 1999.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Vear F, Tourvieille de Labroughe D, Miller J. Inheritance of the wild-range downy mildew resistance in the sunflower line RHA419, Helia, 2003;26:19-24.10.2298/HEL0339019VSearch in Google Scholar

[36] Miller JF, Gulya TJ, Seiler GJ. Registration of five fertility restorer sunflower germplasms, Crop Sci, 2002;42:989-991.10.2135/cropsci2002.9890Search in Google Scholar

[37] Radwan O, Mouzeyar S, Venisse JS, Nicolas P, Bouzidi MF. Resistance of sunflower to the biotrophic oomycete Plasmopara halstedii is associated with a delayed hypersensitive response within the hypocotyls, J Exp Bot, 2005b;56: 2683-269310.1093/jxb/eri261Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Vear F, Serre F, Roche S, Walser P, Tourvieille de Labrouhe D. Recent research on downy midew resistance useful for breeding industrial-use sunflowers, Helia, 2007;30:45-54.10.2298/HEL0746045VSearch in Google Scholar

[39] Sakr N. Can we enhance durable resistance against Plasmopara halstedii (sunflower downy mildew)? J Plant Protection Res, 2010;50:15-21.10.2478/v10045-010-0003-7Search in Google Scholar

[40] Tourvieille de Labrouhe D, Serre F, Walser P, Roche S, Vear F. Quantitative resistance to downy mildew Plasmopara halstedii in sunflower Helianthus annuus Euphytica, 2008;164:433-444.10.1007/s10681-008-9698-1Search in Google Scholar

[41] Vear F, Serre F, Jouan-Dufournel I, Bert PF, Roche S, Walser P, et al. Inheritance of quantitative resistance to downy mildew Plasmopara halstedii in sunflower Helianthus annuus L.). Euphytica, 2008a;164:561-570.10.1007/s10681-008-9759-5Search in Google Scholar

[42] McDonald BA, Linde C. Pathogen population genetics, evolutionary potential, and durable resistance, Annu Rev Phytopathol, 2002;40:349-379.10.1146/annurev.phyto.40.120501.101443Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Qi LL, Long YM, Jan CC, Ma GJ, Gulya TJ. Pl17 is a novel gene independent of known downy mildew resistance genes in the cultivated sunflower Helianthus annuus L.), Theor Appl Genet, 2015;128(4):757-767.10.1007/s00122-015-2470-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Gascuel Q, Martinez Y, Boniface MC, Vear F, Pichon M, Godiard L. The sunflower downy mildew pathogen Plasmopara halstedii Mol Plant Pathol, 2015;16(2):109-122.10.1111/mpp.12164Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Gilley MA, Markell SG, Gulya TJ, Misar CG. Prevalence and virulence of Plasmopara halstedii (downy mildew) in sunflowers in 2014. In: Proceeding 37th Sunflower Research Forum. Fargo ND, (7–8 Jan 2015).Search in Google Scholar

© 2018 Ezgi Çabuk Şahin et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Article

- Purification of Tea saponins and Evaluation of its Effect on Alcohol Dehydrogenase Activity

- Runt-related transcription factor 3 promoter hypermethylation and gastric cancer risk: A meta-analysis

- Risk Factors for Venous Thromboembolism in Hospitalized Patients in the Chinese Population

- Value of Dual-energy Lung Perfusion Imaging Using a Dual-source CT System for the Pulmonary Embolism

- A new combination of substrates: biogas production and diversity of the methanogenic microorganisms

- mTOR modulates CD8+ T cell differentiation in mice with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis

- Direct Effects on Seed Germination of 17 Tree Species under Elevated Temperature and CO2 Conditions

- Role of water soluble vitamins in the reduction diet of an amateur sportsman

- Aberrant DNA methylation involved in obese women with systemic insulin resistance

- 16S ribosomal RNA-based gut microbiome composition analysis in infants with breast milk jaundice

- Characterization of Haemophilus parasuis Serovar 2 CL120103, a Moderately Virulent Strain in China

- MiRNA-145 induces apoptosis in a gallbladder carcinoma cell line by targeting DFF45

- Telmisartan induces osteosarcoma cells growth inhibition and apoptosis via suppressing mTOR pathway

- Optimizing the Formulation for Ginkgolide B Solid Dispersion

- Determination of the In Vitro Gas Production and Potential Feed Value of Olive, Mulberry and Sour Orange Tree Leaves

- Factors Influencing the Successful Isolation and Expansion of Aging Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells

- The Value of Diffusion-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Predicting the Efficacy of Radiation and Chemotherapy in Cervical Cancer

- Chemical profile and antioxidant activity of Trollius europaeus under the influence of feeding aphids

- SSR Markers Suitable for Marker Assisted Selection in Sunflower for Downy Mildew Resistance

- A Fibroblast Growth Factor Antagonist Peptide Inhibits Breast Cancer in BALB/c Mice

- Antihyperglycemic and antihyperlipidemic effects of low-molecular-weight carrageenan in rats

- Microbial indicators and environmental relationships in the Umhlangane River, Durban, South Africa

- TUFT1 promotes osteosarcoma cell proliferation and predicts poor prognosis in osteosarcoma patients

- Long non-coding RNA-2271 promotes osteogenic differentiation in human bone marrow stem cells

- The prediction of cardiac events in patients with acute ST segment elevation myocardial infarction: A meta–analysis of serum uric acid

- Risk expansion of Cr through amphibious clonal plant from polluted aquatic to terrestrial habitats

- Overexpression of Zinc Finger Transcription Factor ZAT6 Enhances Salt Tolerance

- Sini decoction intervention on atherosclerosis via PPARγ-LXRα-ABCA1 pathway in rabbits

- Soluble myeloid triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cell 1 might have more diagnostic value for bacterial ascites than C-reactive protein

- A Preliminary Study on the Newly Isolated High Laccase-producing Fungi: Screening, Strain Characteristics and Induction of Laccase Production

- Hydrolytic Enzyme Production by Thermophilic Bacteria Isolated from Saudi Hot Springs

- Analysis of physiological parameters of Desulfovibrio strains from individuals with colitis

- Emodin promotes apoptosis of human endometrial cancer through regulating the MAPK and PI3K/ AKT pathways

- Down-regulation of miR-539 indicates poor prognosis in patients with pancreatic cancer

- Inhibitory activities of ethanolic extracts of two macrofungi against eggs and miracidia of Fasciola spp.

- PAQR6 expression enhancement suggests a worse prognosis in prostate cancer patients

- Characterization of a potential ripening regulator, SlNAC3, from Solanum lycopersicum

- Expression of Angiopoietin and VEGF in cervical cancer and its clinical significance

- Umbilical Cord Tissue Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Can Differentiate into Skin Cells

- Isolation and Characterization of a Phage to Control Vancomycin Resistant Enterococcus faecium

- Glycogen Phosphorylase Isoenzyme Bb, Myoglobin and BNP in ANT-Induced Cardiotoxicity

- BAG2 overexpression correlates with growth and poor prognosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- Relationship between climate trends and grassland yield across contrasting European locations

- Review Articles

- Mechanisms of salt tolerance in halophytes: current understanding and recent advances

- Salivary protein roles in oral health and as predictors of caries risk

- Nanoparticles as carriers of proteins, peptides and other therapeutic molecules

- Survival mechanisms to selective pressures and implications

- Up-regulation of key glycolysis proteins in cancer development

- Communications

- In vitro plant regeneration of Zenia insignis Chun

- DNA barcoding of online herbal supplements: crowd-sourcing pharmacovigilance in high school

- Case Reports

- Management of myasthenia gravis during pregnancy: A report of eight cases

- Three Cases of Extranodal Rosai-Dorfman Disease and Literature Review

- Letters to the Editor

- First report of Chlamydia psittaci seroprevalence in black-headed gulls (Larus ridibundus) at Dianchi Lake, China

- Special Issue on Agricultural and Biological Sciences - Part II

- Chemical composition of essential oil in Mosla chinensis Maxim cv. Jiangxiangru and its inhibitory effect on Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation

- Secondary metabolites of Antarctic fungi antagonistic to aquatic pathogenic bacteria

- Study of Seizure-Manifested Hartnup Disorder Case Induced by Novel Mutations in SLC6A19

- Transcriptome analysis of Pinus massoniana Lamb. microstrobili during sexual reversal

- Mechanism of oxymatrine-induced human esophageal cancer cell apoptosis by the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway

- Methylation pattern polymorphism of cyp19a in Nile tilapia and hybrids

- A Method of Biomedical Information Classification based on Particle Swarm Optimization with Inertia Weight and Mutation

- A novel TNNI3 gene mutation (c.235C>T/ p.Arg79Cys) found in a thirty-eight-year-old women with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- Remote Sensing-Based Extraction and Analysis of Temporal and Spatial Variations of Winter Wheat Planting Areas in the Henan Province of China

- Topical Issue on Precision Medicine

- Serum sTREM-1, PCT, CRP, Lac as biomarkers for death risk within 28 days in patients with severe sepsis

- IL-17 gene rs3748067 C>T polymorphism and gastric cancer risk: A meta-analysis

- Efficacy of Danhong injection on serum concentration of TNF-α, IL-6 and NF-κB in rats with intracerebral hemorrhage

- An ensemble method to predict target genes and pathways in uveal melanoma

- Evaluation of the quality of CT images acquired with smart metal artifact reduction software

- NPM1A in plasma is a potential prognostic biomarker in acute myeloid leukemia

- Arterial infusion of rapamycin in the treatment of rabbit hepatocellular carcinoma to improve the effect of TACE

- New progress in understanding the cellular mechanisms of anti-arrhythmic drugs

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Article

- Purification of Tea saponins and Evaluation of its Effect on Alcohol Dehydrogenase Activity

- Runt-related transcription factor 3 promoter hypermethylation and gastric cancer risk: A meta-analysis

- Risk Factors for Venous Thromboembolism in Hospitalized Patients in the Chinese Population

- Value of Dual-energy Lung Perfusion Imaging Using a Dual-source CT System for the Pulmonary Embolism

- A new combination of substrates: biogas production and diversity of the methanogenic microorganisms

- mTOR modulates CD8+ T cell differentiation in mice with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis

- Direct Effects on Seed Germination of 17 Tree Species under Elevated Temperature and CO2 Conditions

- Role of water soluble vitamins in the reduction diet of an amateur sportsman

- Aberrant DNA methylation involved in obese women with systemic insulin resistance

- 16S ribosomal RNA-based gut microbiome composition analysis in infants with breast milk jaundice

- Characterization of Haemophilus parasuis Serovar 2 CL120103, a Moderately Virulent Strain in China

- MiRNA-145 induces apoptosis in a gallbladder carcinoma cell line by targeting DFF45

- Telmisartan induces osteosarcoma cells growth inhibition and apoptosis via suppressing mTOR pathway

- Optimizing the Formulation for Ginkgolide B Solid Dispersion

- Determination of the In Vitro Gas Production and Potential Feed Value of Olive, Mulberry and Sour Orange Tree Leaves

- Factors Influencing the Successful Isolation and Expansion of Aging Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells

- The Value of Diffusion-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Predicting the Efficacy of Radiation and Chemotherapy in Cervical Cancer

- Chemical profile and antioxidant activity of Trollius europaeus under the influence of feeding aphids

- SSR Markers Suitable for Marker Assisted Selection in Sunflower for Downy Mildew Resistance

- A Fibroblast Growth Factor Antagonist Peptide Inhibits Breast Cancer in BALB/c Mice

- Antihyperglycemic and antihyperlipidemic effects of low-molecular-weight carrageenan in rats

- Microbial indicators and environmental relationships in the Umhlangane River, Durban, South Africa

- TUFT1 promotes osteosarcoma cell proliferation and predicts poor prognosis in osteosarcoma patients

- Long non-coding RNA-2271 promotes osteogenic differentiation in human bone marrow stem cells

- The prediction of cardiac events in patients with acute ST segment elevation myocardial infarction: A meta–analysis of serum uric acid

- Risk expansion of Cr through amphibious clonal plant from polluted aquatic to terrestrial habitats

- Overexpression of Zinc Finger Transcription Factor ZAT6 Enhances Salt Tolerance

- Sini decoction intervention on atherosclerosis via PPARγ-LXRα-ABCA1 pathway in rabbits

- Soluble myeloid triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cell 1 might have more diagnostic value for bacterial ascites than C-reactive protein

- A Preliminary Study on the Newly Isolated High Laccase-producing Fungi: Screening, Strain Characteristics and Induction of Laccase Production

- Hydrolytic Enzyme Production by Thermophilic Bacteria Isolated from Saudi Hot Springs

- Analysis of physiological parameters of Desulfovibrio strains from individuals with colitis

- Emodin promotes apoptosis of human endometrial cancer through regulating the MAPK and PI3K/ AKT pathways

- Down-regulation of miR-539 indicates poor prognosis in patients with pancreatic cancer

- Inhibitory activities of ethanolic extracts of two macrofungi against eggs and miracidia of Fasciola spp.

- PAQR6 expression enhancement suggests a worse prognosis in prostate cancer patients

- Characterization of a potential ripening regulator, SlNAC3, from Solanum lycopersicum

- Expression of Angiopoietin and VEGF in cervical cancer and its clinical significance

- Umbilical Cord Tissue Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Can Differentiate into Skin Cells

- Isolation and Characterization of a Phage to Control Vancomycin Resistant Enterococcus faecium

- Glycogen Phosphorylase Isoenzyme Bb, Myoglobin and BNP in ANT-Induced Cardiotoxicity

- BAG2 overexpression correlates with growth and poor prognosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- Relationship between climate trends and grassland yield across contrasting European locations

- Review Articles

- Mechanisms of salt tolerance in halophytes: current understanding and recent advances

- Salivary protein roles in oral health and as predictors of caries risk

- Nanoparticles as carriers of proteins, peptides and other therapeutic molecules

- Survival mechanisms to selective pressures and implications

- Up-regulation of key glycolysis proteins in cancer development

- Communications

- In vitro plant regeneration of Zenia insignis Chun

- DNA barcoding of online herbal supplements: crowd-sourcing pharmacovigilance in high school

- Case Reports

- Management of myasthenia gravis during pregnancy: A report of eight cases

- Three Cases of Extranodal Rosai-Dorfman Disease and Literature Review

- Letters to the Editor

- First report of Chlamydia psittaci seroprevalence in black-headed gulls (Larus ridibundus) at Dianchi Lake, China

- Special Issue on Agricultural and Biological Sciences - Part II

- Chemical composition of essential oil in Mosla chinensis Maxim cv. Jiangxiangru and its inhibitory effect on Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation

- Secondary metabolites of Antarctic fungi antagonistic to aquatic pathogenic bacteria

- Study of Seizure-Manifested Hartnup Disorder Case Induced by Novel Mutations in SLC6A19

- Transcriptome analysis of Pinus massoniana Lamb. microstrobili during sexual reversal

- Mechanism of oxymatrine-induced human esophageal cancer cell apoptosis by the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway

- Methylation pattern polymorphism of cyp19a in Nile tilapia and hybrids

- A Method of Biomedical Information Classification based on Particle Swarm Optimization with Inertia Weight and Mutation

- A novel TNNI3 gene mutation (c.235C>T/ p.Arg79Cys) found in a thirty-eight-year-old women with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- Remote Sensing-Based Extraction and Analysis of Temporal and Spatial Variations of Winter Wheat Planting Areas in the Henan Province of China

- Topical Issue on Precision Medicine

- Serum sTREM-1, PCT, CRP, Lac as biomarkers for death risk within 28 days in patients with severe sepsis

- IL-17 gene rs3748067 C>T polymorphism and gastric cancer risk: A meta-analysis

- Efficacy of Danhong injection on serum concentration of TNF-α, IL-6 and NF-κB in rats with intracerebral hemorrhage

- An ensemble method to predict target genes and pathways in uveal melanoma

- Evaluation of the quality of CT images acquired with smart metal artifact reduction software

- NPM1A in plasma is a potential prognostic biomarker in acute myeloid leukemia

- Arterial infusion of rapamycin in the treatment of rabbit hepatocellular carcinoma to improve the effect of TACE

- New progress in understanding the cellular mechanisms of anti-arrhythmic drugs