Abstract

Even though Linked data has been much discussed and publishing of it has been widely implemented, the ecosystem around exchange of library data is still very much based on copying of MARC-records. A more distributed approach regarding the work done would need new models for both the description and how library systems interact. The last couple of years the National library of Sweden has aimed to take at least one step towards such a model.

Zusammenfassung

Obwohl Linked Data bisher viel diskutiert und viele Publikationen dazu veröffentlicht wurden, ist das System des Austausches von Bibliotheksdaten immer noch lediglich ein Kopieren von MARC-Datensätzen. Für die bisherige Arbeit wird aber ein distribuierterer Ansatz sowohl für die Beschreibung als auch für die Interaktion von Bibliotheken benötigt. In den letzten Jahren hat die Schwedische Nationalbibliothek zumindest einen Schritt in diese Richtung unternommen.

1 Background

Linked Data, a technology that makes it possible to model, link and access information, has in recent years been much discussed in the library world. A great deal of activity has gone into exploring the possibilities and its place in the ecosystem of bibliographic data and control. This is expected since large amounts of bibliographic data created and copied every day between catalogues, which means that the descriptions for the same entity is created independently in several places. There are a number of projects to express bibliographic data in RDF, the format as linked data uses, for example FRBRer, RDA, and BibFrame.

In spite of this the exchange of information between library catalogues is still largely based on the MARC format and copy-cataloguing, i. e. copying of records from one system into another. This usually means that updates at the source will not be transferred to the system that copied it.

Since there are few systems that are built with Linked data in mind, the current focus is to model, convert and publish linked data rather than to consume and link, which makes it not part of cataloguers work process. What happens if we raise our eyes a little, however, is that we can discern an opportunity to not only published linked data, but a fundamentally different approach to cataloguing and how we describe the libraries’ collections. And this is where greater future benefits are, in a changed, distributed ecosystem for bibliographic data.

2 Aggregates

One way to avoid this duplication and multiple manually created descriptions of the same thing is to aggregate a large number of records from different sources in the same data set, thus reusing descriptions. This combined with cataloguing directly in this central dataset avoids copying. The question is however, how well this model scales and perhaps especially how the reuse of data can take place outside the cooperation. Chances are that we’ll end up with a small number of large players since maintaining such large aggregates over time require a fair amount of resources. There is also a risk in that the vendor infrastructure creates a lock-in effect where moving from one vendor to another becomes cumbersome if data is tightly connected to the platform.

Collaborative efforts based on cooperative cataloguing, such as union catalogues, basically work the same way with the difference that the relationship is not that of a client and vendor but rather one of cooperation, hopefully with a solid foundation in the form of, for example, a national mission and funding.

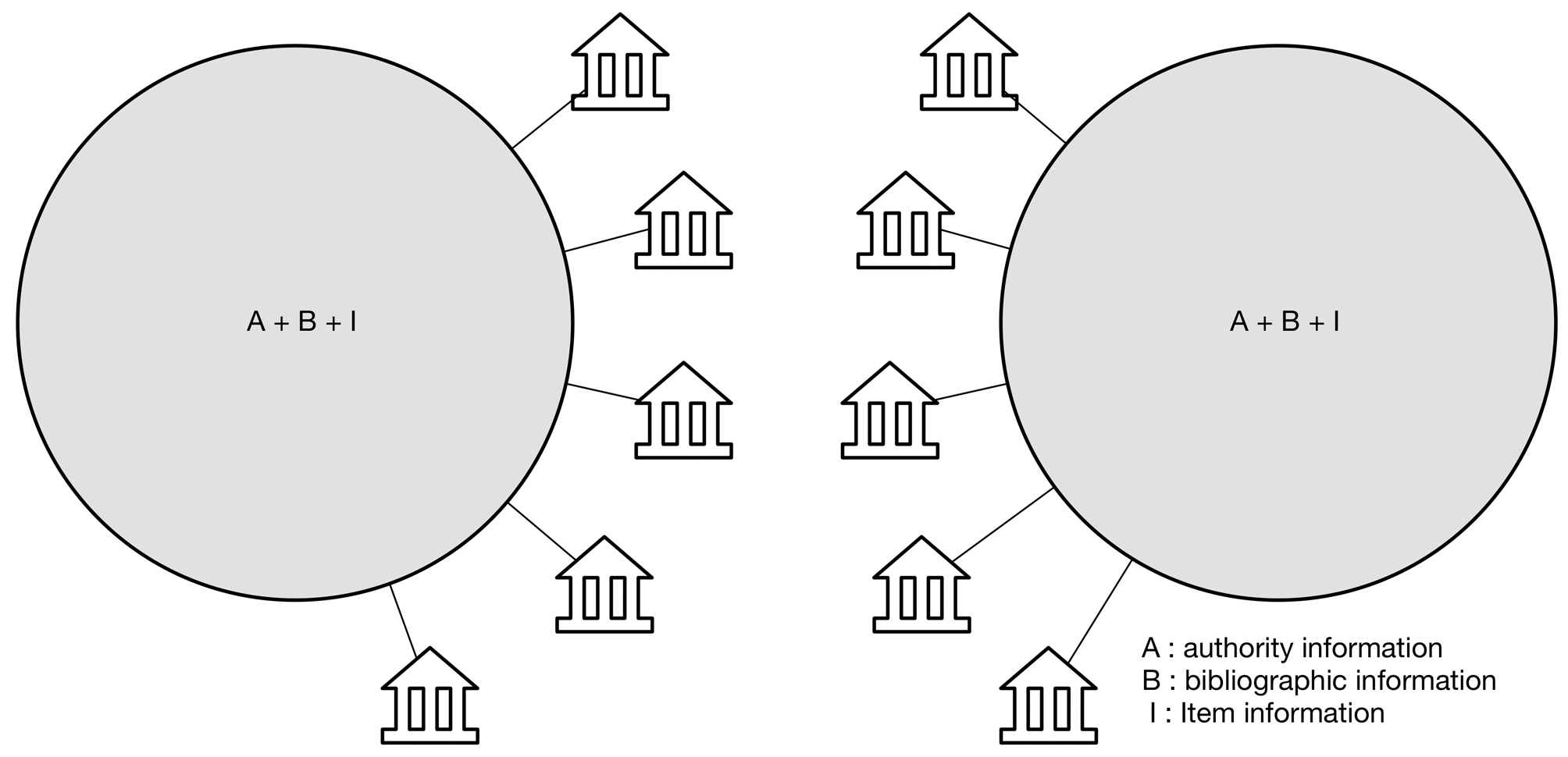

In the image below, all types of bibliographic data (authority, bibliographic and item) is gathered in two aggregates with a number of customers per aggregate. There is of course nothing that prevents copying between these two aggregates if it is allowed license-wise, but then we're back in the model of copying information rather than maintaining it in one place.

This is definitely a valid solution to the problem of copying information, but it is fundamentally centralised solution to a distributed problem, usually centred on vendor infrastructure.

Duelling ecosystems

These are definitely valid solutions to the problem of copying information, but they are fundamentally centralised solutions to a distributed problem.

3 Prerequisites for a distributed system

There are, at least, two levels of distribution possible: that of the record and that of infrastructure. Either can be implemented separately, though implementation of the former will give rise to discussions about the latter and vice versa.

4 Distribution of the record

The prevailing unit of information shipped around is the record, i. e. a number of bits which contain the description. By design the record is meant to be self-contained in that it contains all the information needed to identify what is being described, much like a traditional, printed library card. While being designed for, and partly achieving, robustness when it comes to identification by a human, it is also the cause for all the copying mentioned above. Furthermore, since external identifiers are rarely used for entities, other than the record itself and its origin, connecting descriptions across systems then fall back to string matching.

On the other hand there are often internal identifiers within library systems to achieve functionality such as linking to authorities, linking between bibliographic records, etc. The barrier, again, is that when exchanging information the internal identifier becomes useless since it only has meaning internally, within the system. Admittedly, work has been done to MARC essentially retrofitting the capability to handle external identifiers by bolting it on to existing fields, but the self-contained model remains.

A distribution of the record would mean making these identifiers visible and break the self-contained nature of the record by linking instead of copying. However, this also means being more precise while cataloguing. A system based on strings and not meant for linking can be lax about precision in a way that a distributed one cannot. This poses a challenge to anyone aiming to move to a more distributed model since creating Linked data from MARC will be inherently imprecise.

There is more than one effort to achieve this by replacing MARC with something based on RDF. This is discussed by Baker, Coyle and Petiya.[1]

5 Distribution of infrastructure

A distributed system is inherently different from one where all data is only available locally. Instead of keeping data and identifiers internal it would publish these for others to see and use. It allows for heterogeneous implementations to “talk” to each other in a standardised way, i. e. Linked data and neighbouring protocols such as SPARQL for queries and Atom when listening for updates.

Baker, Coyle and Petiya mention two major design principles of RDF/Linked data that are relevant: the Open World Assumption (OWA) and Non-unique Naming Assumption (NUNA). They write:

Open World Assumption (OWA): “As a matter of principle, the information available at any given time may be incomplete. This is about more than just assuming that important servers might temporarily be offline. It is about recognizing that new information might be discovered or made available”.

Non-Unique Naming Assumption: “As a matter of principle, things described in RDF data can have more than one name. Because URI’s are used in RDF as names, anything may be identified by more than one URI.”[2]

Together this means that what was a coherent record within one infrastructure would be replaced by a graph where the parts can be created and maintained by multiple organisations independently.

6 Distributed solutions

A distributed solution could come in many forms, but it would mean linking to external resources rather than copying the data. This data can be found in other technical infrastructure, in another organisation, etc. which allow for a distribution of responsibilities of the description. This can obviously be done in several ways and need reasonably be carried out in stages, rather than assume that everyone will switch to Linked data overnight.

It would, however, allow vendors to be transparent about client data to a point where the user of this data do not know, or care, who hosts it and that a change in service provider would not disrupt the ecosystem by, for example changing identifiers.

Keeping with the idea that everyone should minimise what they describe and maximise linkage a plausible scenario would be that national libraries will provide Linked data for works published in that country, identifiers for authors and subject headings. The same goes for publication houses. Community efforts such as Wikidata[3] already contribute linkable information. This leaves item information and usage statistics as the unique data owned and published by the local library system.

7 Scenario one – “Linked data done right”

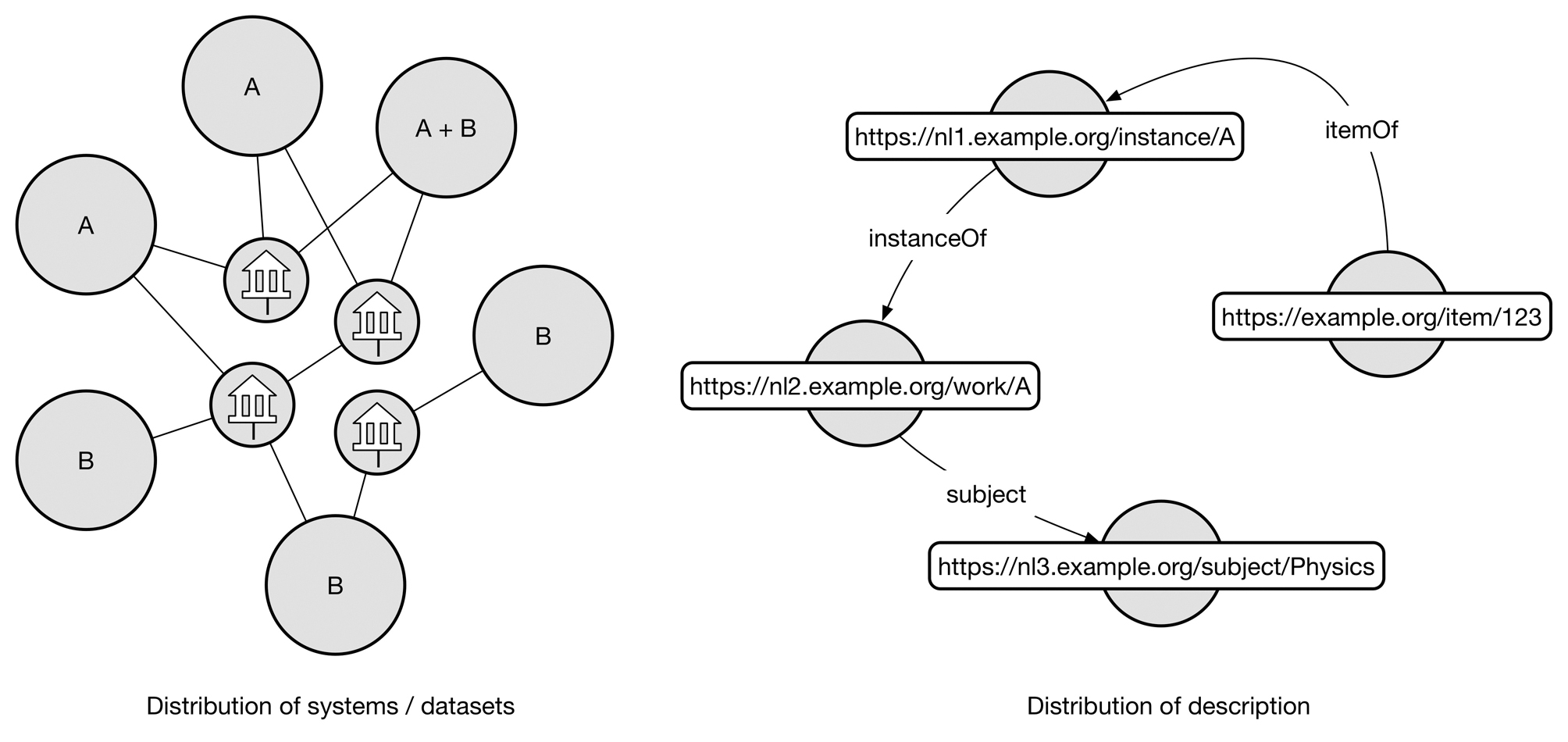

In this scenario, everyone does as little as possible, but no less and publishes the data that is unique to them as Linked data. This means that, for example, a library catalogue would link their item information to an external resource, which could reside at a national library, a publisher or Wikidata. The bibliographic data linked to could in turn link to a resource somewhere else, for example the work record (see FRBR WEMI) which might reside at yet another national library. Again that work record might use subject heading residing somewhere else, etc., etc. This way distribution happens within the description.

This is a very optimistic scenario in that it requires a lot of infrastructure and data to be in place for it to work. It also requires stability and trust between the maintainer of the data and the consumer/linker. These are not technical issues, but have to be dealt with. Moreover, support for the creation of Linked data by cataloguers need to be in place which, again, relies on standards such as BibFrame being stable enough for implementation.

This model could open up for more lightweight library systems that focus on item data and handling of users, leaving detailed descriptions to other parties.

Distribution on system/dataset level and within a single description

8 Scenario two – one step forward

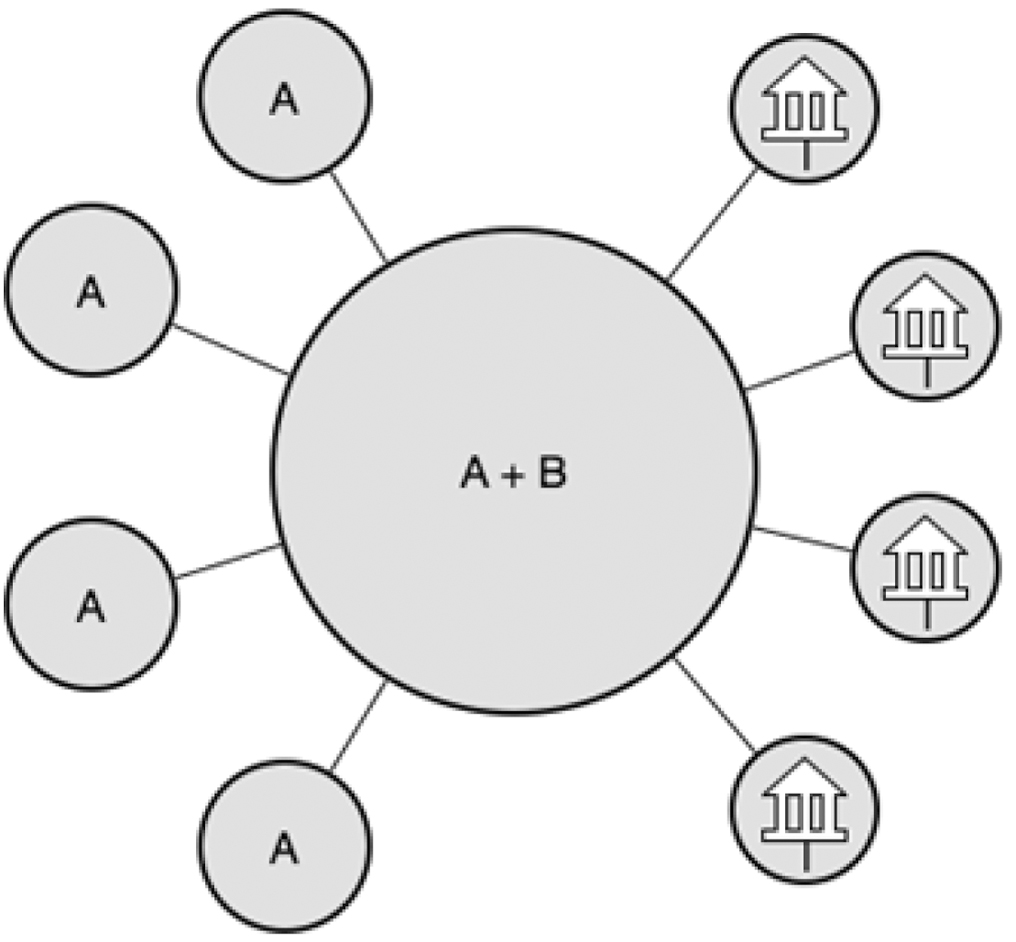

A more realistic scenario is to have local systems deal with a single external provider of bibliographic and authority metadata while keeping, and publishing, item data. This minimises a lot of issues regarding, for example, trust. So while we might need central infrastructure for some time, the challenge for providers is to be as transparent as possible to not make a transition impossible.

Bear in mind that this does not imply that everyone have their own local catalogue installed on servers owned by the library. The main point is that there should, looking from the outside, be no difference between local hosting and being part of a cooperative effort or some vendors’ infrastructure.

Scenario two (A = auth data, B = bib data, I = item data)

9 A step towards a more distributed model in Sweden

The last three years the National library of Sweden has researched the possibility to replace the existing infrastructure for Libris,[4] the Swedish Union Catalogue, with something akin to scenario two. The rationale behind this has been, apart from breaking out of the prison that is MARC21, that higher expectation on the catalogue drives a need for a more flexible, and above all extensible, descriptions formats. There are definitely other formats, but none as flexible as RDF. At the same time Libris is used as infrastructure for a large number of libraries and one of the goals for the National library, the custodian of Libris, is that 85 % of Swedish libraries should be connected by 2020. This means that already existing processes need to be supported during the transition, for example export of MARC-data to member libraries and import of MARC-data from suppliers.

As stated above the imprecise nature of MARC-based formats poses a challenge to anyone moving to RDF. Therefore it is unsurprising that the largest technical hurdle has no doubt been, and still is, the conversion and reconversion of records necessary to function with a MARC21-based ecosystem. While BibFrame is a good starting point for this conversion, there are still outstanding issues that need to be addressed.[5]

In keeping with the idea to publish datasets without it being dependent on specific infrastructure one part of the transition has been the creation of a separate service for data that is solely the responsibility of the National library.[6] It currently holds subject headings and genre terms. This is the first step in trying to separate datasets within Libris while still using the same infrastructure. This does raise the question of ownership which influences identifier creation. The fact that many descriptions in Libris have many creators/maintainers from different organisations over time means that the least common denominator is the collaborative effort itself, resulting in identifiers on the form https://libris.kb.se/<number>.Example.[7]

There are currently no library systems that work with one (or many) external catalogues using Linked data for bibliographic resources, which is also why the National library has funded a project to examine the possibilities of such a system.[8]

10 Conclusion

The technical framework needed for a distributed ecosystem of library data is partly in place, the main challenges are unsurprisingly organisation and change. The work currently being done by BibFrame provides a crucial part, namely a way to transition existing datasets from MARC into RDF. Though the willingness of vendors to embrace this model is a key, but it could also present an opportunity for smaller, more agile players.

Literaturverzeichnis

Baker, Thomas; Coyle, Karen; Petiya, Sean (2014): Multi-entity models of resource description in the Semantic Web. In: Library Hi Tech, 32 (4), 562–82. doi: 10.1108/LHT-08-2014-0081.10.1108/LHT-08-2014-0081Search in Google Scholar

© 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Titelseiten

- Inhaltsfahne

- Die Zukunft des Publizierens

- Zur Situation des digitalen geisteswissenschaftlichen Publizierens – Erfahrungen aus dem DFG-Projekt „Future Publications in den Humanities“

- Von der Digitalisierung zur Digitalität: Wissenschaftsverlage vor anderen Herausforderungen

- Finanzierungsmodelle für Open-Access-Zeitschriften

- Best Practice

- Stadtbücherei Hilden – Bibliothek des Jahres 2016

- Next generation library systems

- A Step Towards a Distributed Model for Bibliographic Data in Sweden

- DARIAH

- CLARIN-D: eine Forschungsinfrastruktur für die sprachbasierte Forschung in den Geistes- und Sozialwissenschaften

- Weitere Beiträge

- Informationsverhalten, sozialer Kontext und Bibliotheken: Annäherungen an Theorien der Small Worlds und Informationswelten

- Kultur und Wissen digital vermitteln – Stand und Perspektiven der Deutschen Digitalen Bibliothek – ein Überblick

- Bibliotheken auf dem Weg zu lernenden Organisationen – Entwicklung eines Selbstbewertungstools

- Die Niederösterreichische Landesbibliothek

- Lernzentren – eine kurze Bestandsaufnahme

- Aus der Frühzeit der Mainzer Skriptorien: Ein unbekanntes karolingisches Handschriftenfragment (Mainz, Wissenschaftliche Stadtbibliothek, Hs frag 20)

- Für die Praxis

- Befähigung im Wandel

- Bibliographische Übersichten

- Zeitungen in Bibliotheken

- Rezensionen

- Georg Ruppelt (Hrsg.): 350 Jahre Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Bibliothek (1665–2015). Hannover: Gottfried-Wilhelm-Leibniz-Bibliothek, 2015. 453 S., ISBN: 978-3-943922-12-7. 44,80 €

- Katrin Janz-Wenig, Monika E. Müller, Gregor Patt: Die mittelalterlichen Handschriften und Fragmente der Signaturengruppe D in der Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Düsseldorf, Teil 1: Textband; Teil 2: Tafelband. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2015 (Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Düsseldorf, Kataloge der Handschriftenabteilung; 4). 2 Bde., 453 + 553 S., 603 farbige Abb. ISBN 978-3-447-10514-9. 298,– EUR.

- Paul Ladewig: Katechizm biblioteki. Przelożył z języka niemieckiego na język polski Zdzisław Gębolyś; przy wspólpracy Bernharda Kwoki; przelożył z języka niemieckiego na język angielski Zdzislaw Gębolyś. Bydgoszcz: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Kazimierza Wielkiego, 2016. 211 S., 35 s/w-Abb. Kart. ISBN 978-83-8018-050-5. 29,40 zł (ca. 6,60 €)

Articles in the same Issue

- Titelseiten

- Inhaltsfahne

- Die Zukunft des Publizierens

- Zur Situation des digitalen geisteswissenschaftlichen Publizierens – Erfahrungen aus dem DFG-Projekt „Future Publications in den Humanities“

- Von der Digitalisierung zur Digitalität: Wissenschaftsverlage vor anderen Herausforderungen

- Finanzierungsmodelle für Open-Access-Zeitschriften

- Best Practice

- Stadtbücherei Hilden – Bibliothek des Jahres 2016

- Next generation library systems

- A Step Towards a Distributed Model for Bibliographic Data in Sweden

- DARIAH

- CLARIN-D: eine Forschungsinfrastruktur für die sprachbasierte Forschung in den Geistes- und Sozialwissenschaften

- Weitere Beiträge

- Informationsverhalten, sozialer Kontext und Bibliotheken: Annäherungen an Theorien der Small Worlds und Informationswelten

- Kultur und Wissen digital vermitteln – Stand und Perspektiven der Deutschen Digitalen Bibliothek – ein Überblick

- Bibliotheken auf dem Weg zu lernenden Organisationen – Entwicklung eines Selbstbewertungstools

- Die Niederösterreichische Landesbibliothek

- Lernzentren – eine kurze Bestandsaufnahme

- Aus der Frühzeit der Mainzer Skriptorien: Ein unbekanntes karolingisches Handschriftenfragment (Mainz, Wissenschaftliche Stadtbibliothek, Hs frag 20)

- Für die Praxis

- Befähigung im Wandel

- Bibliographische Übersichten

- Zeitungen in Bibliotheken

- Rezensionen

- Georg Ruppelt (Hrsg.): 350 Jahre Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Bibliothek (1665–2015). Hannover: Gottfried-Wilhelm-Leibniz-Bibliothek, 2015. 453 S., ISBN: 978-3-943922-12-7. 44,80 €

- Katrin Janz-Wenig, Monika E. Müller, Gregor Patt: Die mittelalterlichen Handschriften und Fragmente der Signaturengruppe D in der Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Düsseldorf, Teil 1: Textband; Teil 2: Tafelband. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2015 (Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Düsseldorf, Kataloge der Handschriftenabteilung; 4). 2 Bde., 453 + 553 S., 603 farbige Abb. ISBN 978-3-447-10514-9. 298,– EUR.

- Paul Ladewig: Katechizm biblioteki. Przelożył z języka niemieckiego na język polski Zdzisław Gębolyś; przy wspólpracy Bernharda Kwoki; przelożył z języka niemieckiego na język angielski Zdzislaw Gębolyś. Bydgoszcz: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Kazimierza Wielkiego, 2016. 211 S., 35 s/w-Abb. Kart. ISBN 978-83-8018-050-5. 29,40 zł (ca. 6,60 €)