Abstract

This study examines the impact of an outreach education in chemistry for circular plastic solutions (OEC-Circle) program on enhancing Thai 12th-grade students’ understanding of plastic-related chemistry and fostering positive learning attitudes. The program integrates the circular plastic economy through inquiry-based learning, including citizen inquiry and guided inquiry activities. The curriculum consists of three modules: Plastic Smart City, circular plastic economy, and sustainable polymer, blending lecture, demonstration, laboratory, and field experiences. A total of 32 students participated, and their learning outcomes were assessed using a pre- and post-test, along with a learning attitude about chemistry survey (CLASS-Chem). Results indicated a significant improvement in students’ understanding of topics like sustainable polymers and waste management, with a large effect size in the post-test. The CLASS-Chem survey also showed a positive shift in students’ attitudes, including increased interest, confidence, and an understanding of the real-world relevance of chemistry. These findings suggest that the program was effective in both improving students’ chemistry knowledge and fostering a deeper engagement with sustainability issues. The study highlights the potential of combining inquiry-driven learning with sustainability themes to enhance students’ attitudes toward chemistry and prepare them to address real-world challenges, particularly those related to plastic waste and sustainability.

1 Background

Since the invention of the first fully synthetic plastic, Bakelite, in 1907, polymers have revolutionized various aspects of modern life, underpinning industries such as packaging, automotive, electronics, healthcare, and consumer products. 1 Their low cost, versatility, and durability have led to an exponential rise in production, resulting in plastics becoming both indispensable and environmentally problematic materials in our society. 2 The persistence of plastics in the environment has triggered widespread concern, particularly due to their accumulation in oceans and landfills, their contribution to microplastic pollution, and their adverse impacts on ecosystems and human health. Recognizing these challenges, chemistry educators have sought safer and greener approaches to teaching about polymers and plastics, particularly in STEM outreach contexts. For instance, Boyd (2021) proposed demonstrations that are both engaging and environmentally responsible, which serve as models for sustainable educational practices. 3 These foundational approaches support the integration of sustainability principles into educational settings and underscore the relevance of hands-on experiences in promoting awareness of plastic-related issues.

Educational responses to plastic-related environmental issues increasingly recognize the urgency of embedding sustainability principles into science education, especially within the discipline of chemistry, which is uniquely positioned to address material, environmental, and industrial challenges. 4 Chemistry offers conceptual tools to understand resource use, material transformation, and waste, making it essential for educating environmentally responsible citizens and future scientists. As such, researchers have advocated for the integration of sustainable development, green chemistry, and circular economy frameworks into chemistry curricula to enhance student engagement with global challenges. 5 , 6 The incorporation of these themes supports not only cognitive learning outcomes but also affective dimensions such as values, responsibility, and decision-making. For example, Wissinger et al. highlighted how sustainability-linked instructional strategies improve the perceived relevance of chemistry by connecting it with real-world applications. 4 Juntunen and Aksela further noted that pedagogical models based on systems thinking and interdisciplinary approaches can strengthen students’ capacity to engage with complex sustainability issues. 7 Moreover, Summerton et al. emphasized the role of industry-informed CE education in developing graduate-level competencies, promoting both technical understanding and ethical awareness. 8 These findings collectively suggest that purposeful curriculum design aligned with sustainability imperatives can significantly transform chemistry education for the 21st century. However, conventional instructional approaches, whether at the secondary level, frequently struggle to engage learners in meaningful experiences that connect abstract principles to tangible societal and environmental challenges. 9 To address this gap, integrating the circular plastic economy into school chemistry curricula equips students with the knowledge and skills to tackle plastic waste and promote sustainable practices. 5 Indeed, modern polymers and sustainability should also be useful in outreach activities with secondary school students. 10 , 11

Traditional methods of teaching chemistry often centered on rote memorization, decontextualized content, and rigid laboratory procedures, and have been criticized for failing to connect abstract scientific principles with students’ everyday experiences and pressing societal issues. 9 This disconnect can lead to student disengagement and misconceptions about the relevance of chemistry, particularly in addressing environmental problems. To bridge this gap, educational researchers have increasingly promoted inquiry-based learning (IBL) and outreach programs as transformative pedagogical models. IBL encourages students to actively construct knowledge through hands-on experimentation, problem-solving, and critical thinking within meaningful contexts. 12 Studies by Singha and Singha (2024) have shown that integrating IBL and project-based learning in sustainability contexts can significantly improve learners’ motivation and analytical skills. 13 Furthermore, outreach programs such as Polymer Day and sustainability-themed modules have demonstrated effectiveness in fostering positive attitudes and improving conceptual understanding, especially when implemented through collaborative, community-linked, or interdisciplinary approaches. 14 These strategies align with modern visions of chemistry education reform.

Outreach education programs that combine context-based and inquiry-driven approaches provide vital opportunities to connect formal classroom learning with real-world environmental and societal challenges. These programs often include hands-on investigations, community-driven research, and authentic problem-solving tasks that empower students to take ownership of their learning. For instance, Noll et al. (2024) demonstrated how inquiry-based polymer science activities in outreach settings engage learners with sustainable material use while strengthening scientific reasoning. 10 Similarly, Herrera Monegro et al. (2024) reported that citizen science-inspired waste-sorting activities significantly enhanced students’ critical thinking and environmental responsibility. 11 Community-based inquiry fosters not only conceptual understanding but also a sense of agency and civic engagement, particularly when learners investigate issues relevant to their local contexts. 15 Additionally, the integration of digital tools, such as interactive simulations, mobile sensors, and virtual laboratories, has been shown to amplify these benefits by enabling students to explore complex chemical phenomena like polymer degradation and recycling pathways in dynamic, immersive environments. 16 , 17 , 18 , 19

This study presents an outreach education in chemistry for circular plastic solutions (OEC-Circle) program centered around the theme of chemistry for circular plastics and sustainable living. The theme promotes a sustainable approach to plastic use, emphasizing the principles of reduce, reuse, and recycle, alongside innovations in biodegradable polymers. The OEC-circle program was designed to engage upper secondary students in chemistry through inquiry-based pedagogies applied in both formal and informal learning settings. Students explored real-world challenges related to plastic use, connected them to core chemistry concepts, and participated in activities that emphasized environmental responsibility and systems thinking. Despite increasing global attention on sustainability in science education, there remains a lack of empirically grounded outreach programs, particularly in Southeast Asian school contexts, that integrate circular plastic economy content into chemistry instruction and evaluate both conceptual and attitudinal learning outcomes. This study addresses that gap by implementing and assessing a contextually relevant OEC-Circle program that links chemical knowledge and attitudes with sustainable action. In the light of this, our research was steered by two primary questions:

Do students’ plastic-related chemistry understanding change over the OEC-Circle program on the circular plastic economy?

What are students’ learning attitudes towards chemistry in the OEC-circle program on circular plastic economy?

While the OEC-circle program incorporated inquiry-based elements such as citizen and guided inquiry, this study aimed to evaluate the impact of the program as a whole, including its theme, design, content structure, and implementation, on students’ chemistry understanding and attitudes. Rather than attempting to isolate the effects of specific instructional components, we focused on evaluating the overall educational impact of the integrated outreach experience.

2 Circular economy and sustainability in chemistry education

The concept of the circular economy (CE) has gained substantial traction as a sustainable alternative to the traditional linear economic model, emphasizing the reduction, reuse, and recycling of materials to minimize waste and environmental impact. 20 In the context of chemistry education, integrating CE principles fosters a deeper understanding of sustainable practices and prepares students to address complex environmental challenges. 6 Chemistry educators are increasingly recognizing the importance of embedding sustainability into curricula to cultivate environmentally responsible scientists and informed citizens. 4

Recent studies highlight the effectiveness of interdisciplinary approaches in teaching CE, where chemistry is linked with fields such as environmental science, engineering, and economics to provide a holistic view of sustainability. 8 For instance, project-oriented and inquiry-based learning methodologies have successfully engaged students in real-world sustainability issues, promoting critical thinking, problem-solving skills, and the application of theoretical knowledge to practical scenarios, which enhances their understanding of sustainable chemistry practices. 13 Moreover, the integration of digital tools has been shown to augment the teaching of CE concepts or green and sustainable processes in chemistry by providing interactive and flexible learning environments. 16 Digitalized learning materials facilitate the exploration of complex chemical processes related to CE and sustainable development, allowing students to experiment and visualize the lifecycle of materials without the constraints of physical laboratories. 17 , 18 Digitalization and technological integration not only make CE and sustainable chemistry education more accessible but also align with the evolving digital landscape of modern education. 21 , 22

Despite these advancements, challenges remain in effectively incorporating CE into chemistry or STEM education. Educators often face constraints such as limited resources, insufficient training, and rigid curricular structures that hinder the seamless integration of sustainability concepts. 7 Addressing these barriers requires institutional support, continuous professional development for teachers, and the development of comprehensive curricular frameworks that prioritize sustainability. 23 Additionally, fostering collaborations between educational institutions, industry partners, and policymakers can enhance the relevance and impact of CE and sustainability education by aligning it with real-world sustainability goals. 21 , 23

3 Integration of circular plastic economy in school chemistry

Plastics, as a subset of polymers, play a critical role in the global economy but pose significant environmental challenges due to their persistent nature and limited recyclability. 1 The integration of the circular plastic economy (CPE) into school chemistry curricula is essential for addressing the multifaceted issues associated with plastic waste and promoting sustainable consumption and production patterns. 2 CPE education emphasizes the principles of design for recycling, material recovery, and the development of biodegradable alternatives, aligning with the broader objectives of the circular economy. 24

Educational programs focused on CPE leverage hands-on activities, case studies, and collaborative projects to engage students in the complexities of plastic lifecycle management. 25 The integration of real-world case studies, such as “Plasticized Childhood” and “Unpacking Burgers,” into the school chemistry curriculum has significantly enhanced students’ understanding of the principles of the CPE. 21 These case studies have proven effective in cultivating critical thinking and problem-solving skills, which are vital for addressing the complex challenges of sustainability in the context of plastics. Feedback from students suggests that integrating CPE-focused case studies into the curriculum has significantly boosted student engagement and learning outcomes. 22

However, the successful implementation of CPE in school chemistry is contingent upon overcoming several obstacles. These include the lack of standardized curricular materials, limited access to laboratory facilities, and varying levels of educator expertise in sustainability topics. 7 To mitigate these challenges, it is imperative to develop robust curricular resources, provide targeted professional development for teachers, and establish partnerships with environmental organizations and industry stakeholders. 23 Additionally, incorporating assessment tools that measure students’ understanding and application of CPE principles can inform the continuous improvement of educational programs. 16 Moreover, the integration of digital technologies in plastic-related chemistry learning could be a promising potential to support students in achieving core chemistry competencies. 19

Emerging trends in CPE education highlight the importance of integrating circularity concepts early in the educational journey, thereby cultivating a generation of environmentally conscious individuals equipped to drive sustainability initiatives. 23 By embedding CPE into school chemistry, educators can play a pivotal role in mitigating plastic pollution, promoting sustainable material use, and contributing to the global transition towards a circular economy. 2

4 Curriculum: an OEC-circle program on CPE

4.1 Format of the OEC-circle program

The OEC-Circle program was designed as a 6-day intensive camp spread over 3 weeks, integrating both context-based and inquiry-based educational frameworks. This integrative approach effectively engages students by illustrating the interplay between various disciplines and emphasizing real-world applications, which enhances the long-term retention of concepts. The curriculum systematically breaks down conventional chemistry concepts into comprehensive subtopics, ensuring a coherent and progressively challenging learning experience anchored in real-life contexts.

The OEC-Circle camp focused on the CPE, utilizing everyday scenarios to connect related ideas and foster systems thinking. The program comprised three distinct learning modules – Plastic Smart City, circular plastic economy, and sustainable polymer – each designed to provide comprehensive insights into different aspects of the circular plastic economy. Students were organized into mixed-gender groups to promote collaboration and inclusivity, engaging in activities such as chemistry demonstrations, hands-on experiments, field research, and brainstorming sessions. These activities were meticulously structured to reinforce the core principles of the circular plastic economy, ensuring an immersive and holistic learning journey supported by expert mentors.

4.2 Learning modules from the OEC-circle program

The OEC-Circle program employed a “living laboratory” approach, leveraging the school campus and local community as practical venues for experiential learning. 26 This approach allowed students to apply classroom knowledge directly to their immediate environment, facilitating a deeper understanding of the circular economy from a scientific perspective. The program was divided into three equally timed modules, each encompassing in-class, in-lab, and in-field activities.

Module 1: Plastic smart city. This module introduced the concept of smart cities committed to zero plastic leakage, exploring the integration of circular economy principles within urban environments. Students engaged in citizen inquiry projects focused on plastic management within their school and community, fostering an understanding of systemic approaches to plastic pollution.

Module 2: Circular plastic economy. Building on the first module, this segment delved deeper into the principles of reuse, reduce, and recycling of plastic materials. Through guided-inquiry laboratory activities and field research, students investigated innovative recycling technologies and strategies to reduce plastic waste, enhancing their practical and analytical skills.

Module 3: Sustainable polymer. The final module focused on the development of sustainable polymers, exploring biodegradable alternatives and the chemistry behind polymer degradation. Interactive experiments enabled students to comprehend the lifecycle of plastics, and the scientific advancements aimed at mitigating environmental impact.

To provide clarity on the instructional design and pedagogical structure of the OEC-Circle program, Figure 1 presents a schematic diagram illustrating the three learning modules and their sequential integration. Each module is purposefully designed to build upon the previous one, enabling students to develop a comprehensive understanding of plastic-related chemistry through escalating complexity and contextual relevance.

A visual schematic of the three learning modules of the OEC-CIRCLE program with their sequential flow and pedagogical interconnectedness.

Figure 1 illustrates both the logical sequence and thematic interconnectedness of the modules, with the circular arrow indicating a continuous learning cycle. Each module transitions into the next by building upon prior knowledge – starting from understanding plastic waste issues in urban contexts, progressing through designing circular solutions, and culminating in the development of sustainable polymer alternatives. This integrated flow ultimately leads students toward proposing science-based, systemic solutions for realizing a Plastic Smart City. In addition, these modules were designed to make chemistry education engaging and relevant, encouraging students to develop a genuine interest in chemistry and its applications in sustainability. Teamwork, cooperation, and creative problem-solving were emphasized, with activities tailored to promote inclusive and collaborative learning experiences. Table 1 provides an overview of the three learning modules designed in the OEC-Circle program. Each module was developed around core chemistry content related to plastics, sustainability, and circular economy principles. To ensure the program supported both conceptual learning and attitudinal development, each module was also aligned with specific and measurable learning outcomes. These outcomes address two key domains: (1) chemistry content knowledge; and (2) student attitudes toward chemistry. This alignment between content and outcomes allowed for a holistic chemistry education experience, tailored to real-world sustainability challenges.

Summary of the experimental modules in the OEC-CIRCLE program.

| Module | Name | Major topics | Key learning outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Plastic smart city | Smart city; circular economy; plastic waste and management | Explain the chemical nature and sources of common plastic materials found in urban environments (knowledge) Identify real-world plastic waste problems and connect them with chemical and environmental implications (knowledge) Demonstrate increased interest in chemistry by participating actively in community-based citizen inquiry projects (attitude) Express greater awareness of the relevance of chemistry to everyday life and sustainability issues (attitude) |

| 2 | Circular plastic economy | Plastic circularity: Waste-to-value activated carbon; catalytic pyrolysis of plastic waste | Describe chemical processes involved in plastic recycling, pyrolysis, and conversion to value-added products (knowledge) Analyze plastic consumption data using scientific reasoning and chemical principles (knowledge) Develop more positive attitudes toward the usefulness of chemistry in solving societal problems through hands-on laboratory work (attitude) Evaluate how learning chemistry contributes to sustainable decision-making and environmental stewardship (attitude) |

| 3 | Sustainable polymer | Bioplastic formulation and degradation; types of polymers; polymer properties; polymer, plastic, and its utilization | Differentiate between synthetic and biodegradable polymers based on their chemical structure and properties Construct and interpret experimental data from bioplastic formulation and degradation experiments Report increased confidence in conducting chemistry experiments and explaining their outcomes Reflect on how chemistry contributes to innovative solutions for sustainability and express a more positive attitude toward pursuing science in the future |

4.3 Pedagogical applications in the OEC-circle program

The OEC-circle program integrates two primary pedagogical approaches: citizen inquiry and guided inquiry. These methodologies complement each other to provide comprehensive learning experience.

Citizen inquiry involves community-driven research projects where students identify and investigate real-world issues relevant to their environment. 27 In the OEC-Circle program, students utilized digital platforms such as nQuire 28 for collaborative data collection and analysis. Additionally, Facebook community group was employed to create project pages, fostering a sense of community and democratizing scientific inquiry. This approach empowered students to act as active contributors to scientific research, bridging the gap between academia and everyday life.

Guided Inquiry focuses on structured experimental learning within laboratory settings, allowing students to explore scientific concepts through hands-on activities under the guidance of educators. 29 In the Sustainable Polymer module, students conducted experiments using smartphones equipped with light sensors and thermal infrared imaging plugins. The incorporation of 360-degree video lessons, originally introduced in the Journal of Chemical Education, provided an immersive learning experience, enhancing their understanding of experimental procedures and outcomes. 30 , 31

By blending citizen inquiry with guided inquiry, the OEC-Circle program promoted both collaborative and individual learning, fostering critical thinking and practical skills essential for addressing complex sustainability challenges. This holistic approach ensured that students not only gained theoretical knowledge but also developed the ability to apply it in real-world contexts. Table 2 shows the details of the modules and their learning facilities and support.

Summary of the OEC-circle learning facilities and support.

| Module | Learning setting | Pedagogy | Technological tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plastic smart city | In-class, in-field | Citizen inquiry | nQuire platform, Facebook community group |

| Circular plastic economy | In-class, in-field | Citizen inquiry | nQuire platform, Facebook community group |

| Sustainable polymer | In-class, in-lab | Guided inquiry | Smartphone built-in light sensors, plugin thermal infrared imaging sensor, mobile app., 360-degree video lesson |

4.4 Description of the OEC-circle learning activities and its implementation

The OEC-Circle program comprised a series of structured learning activities conducted on weekends over 3 weeks for a total of 36 h. Thirty-two twelfth-grade students (ages 17–18) from a public school in northeastern Thailand participated. The activities were thoughtfully designed to provide a balanced mix of theoretical knowledge and practical application, fostering an engaging and immersive learning environment. The learning activities are as follows.

Prelab Video: Prior to each laboratory session, students engaged with a 60 min 360-degree interactive prelab video introducing the fundamentals of bioplastic formulation, degradation processes, and laboratory safety. This immersive video provided a virtual walkthrough of the procedures, enabling students to visualize techniques and understand scientific concepts before entering the lab. As a result, in-lab time could be dedicated more fully to experimentation and data analysis, enhancing students’ readiness, confidence, and engagement. The use of 360-degree video encouraged active exploration and curiosity, creating a more personalized and meaningful learning experience. The pedagogical value of such video-based preparation is supported by Nadelson et al. (2014), who reported improved student performance and efficiency in organic chemistry labs when prelab instructional videos were used. 32 Ardisara and Fung (2018) further demonstrated that 360-degree videos offer a wider visual field, improving clarity in complex experimental setups. 33 In parallel, Fung et al. (2019) applied immersive VR environments in environmental chemistry, confirming the benefits of interactive digital tools for enhancing conceptual understanding. 34 Together, these tools foster better preparation, deepen understanding of chemical practices, and promote student-centered learning in chemistry laboratory education. Figure 2 illustrates a screen example of the prelab 360-degree video.

Pre-test session: The OEC-Circle program commenced with a 60 min pre-test session designed to assess the baseline understanding of plastic-related chemistry among the participating students. A 21-item multiple-choice conceptual chemistry questionnaire aligned with the chemistry content of the program (Supplementary Material 1). For the questionnaire, items were reviewed by three chemistry education experts to ensure content validity and then a pilot test with 25 twelve-grade students was conducted to refine wording and assess clarity. Its reliability was confirmed with a KR-20 coefficient of 0.82. Administered at the beginning of the program as a pre-test, this session provided critical insights into the students’ initial knowledge levels and misconceptions. Prior to the pre-test, students received clear instructions emphasizing the importance of honest and individual responses to ensure the accuracy of the assessment.

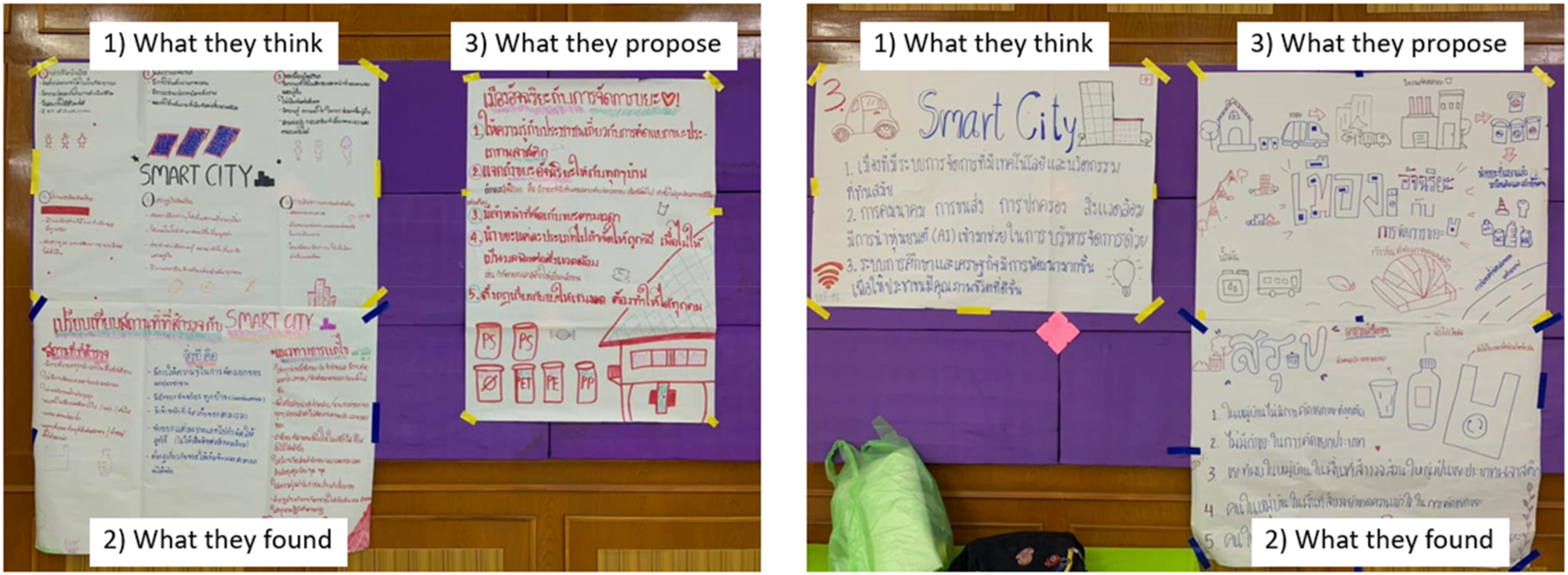

Module 1 – Plastic Smart City: This module spans two days and a total of 12 h. It introduced students to smart city initiatives focused on achieving zero plastic leakage through the application of circular economy principles in urban settings. Students were organized into mixed-gender groups of 4–5 participants. Each group worked collaboratively during the brainstorming, citizen inquiry, and community-based data collection tasks. Group sizes were intentionally kept small to promote active participation, equitable task distribution, and collaborative problem-solving throughout the 12 h module. Before launching into the learning module, students participated in structured training sessions designed to equip them with the digital skills needed to carry out citizen inquiry tasks effectively. The module began with a 180 min introductory session where students received guided instruction on how to use the nQuire platform for data logging and geo-mapping in their citizen science investigations, as well as training on Facebook community group for collaborative communication and sharing results with peers. After that, students collaboratively brainstormed strategies for managing plastic waste within their school and local community. This was followed by a 150 min “Plastic in Our School” citizen inquiry project and a 180 min “Circular Economy in Our Community” project, where students identified plastic pollution sources, collected and analyzed data, and developed actionable mitigation strategies. The module concluded with a 30 min summary session and individual video reflections. Throughout, mixed-gender groups engaged in hands-on activities, field research, and collaborative problem-solving, fostering critical thinking, teamwork, and a deep understanding of sustainable plastic management practices. Supplementary visual documentation of student activities and outputs from this module is presented in Figure 3, offering direct insight into students’ learning, performance, and reflection of their understandings throughout the Plastic Smart City experience.

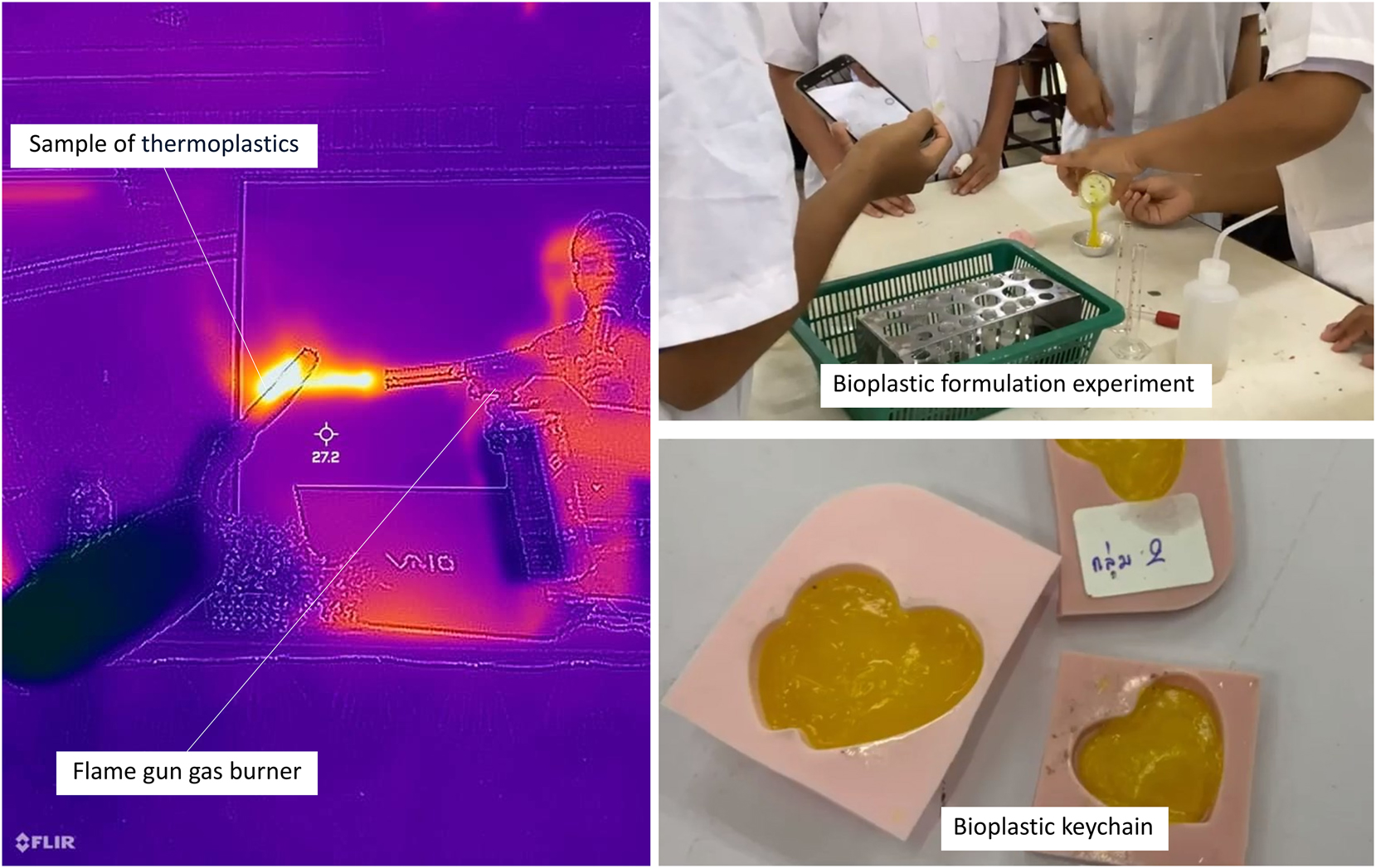

Module 2 – Circular Plastic Economy: The same student groups from Module 1 (4–5 members per group) were retained to ensure continuity in teamwork and inquiry progression. In the beginning of the module, students received hands-on practice using smartphone-integrated light sensors and thermal infrared imaging attachments, which were used in guided inquiry labs for analyzing material properties and recycling processes. These training activities were facilitated by instructors and peer mentors and were embedded in the learning sequence to ensure that students had both the technical confidence and digital fluency necessary to fully participate in the inquiry tasks. This module spanned two days and 9 h of immersive learning. Students assumed the role of “plastic detectives,” utilizing the nQuire application to investigate local community plastic usage patterns. Through these citizen inquiry activities (180 min), they promoted economical plastic use and gained insights into plastic consumption behaviors. The module featured hands-on demonstrations on waste utilization via pyrolysis (150 min), enabling students to understand the thermal decomposition of plastics into usable products. Additionally, students explored the conversion of waste into value-added products, such as activated carbon (180 min), enhancing their practical knowledge of recycling technologies. The module concluded with a 30 min summary session, which reinforced key concepts and encouraged students to reflect on their sustainability initiatives and the impact of their projects on the community. Additional evidence of students’ citizen inquiry-based learning processes and empirical outcomes within this module is presented in Figure 4, showcasing their in-field participation and guided inquiry outputs on sustainable plastic solutions.

Module 3 – Sustainable Polymer: This module encompassed two and a half days and 15 h of comprehensive learning. For laboratory-based guided inquiry and data analysis activities in the module, students were placed in groups of 3 to 4. This smaller grouping allowed students to rotate roles (e.g., recorder, experimenter, analyst, and reporter) during experiments. The module began with a 90 min interactive lecture introducing polymers and plastics, laying the foundational knowledge for students. Students then engaged in a 270 min laboratory session focused on polymer classification, attributes, and formulation, enhancing their technical understanding. This was followed by a 180 min hands-on experience in bioplastic formation and degradation laboratories, deepening their practical insights into sustainable polymers. A 180 min brainstorming session encouraged innovative ideas on plastic utilization and sustainable alternatives. The module concluded with a 120 min circular plastic economy exhibition, where students showcased their projects. Throughout, students developed critical thinking and applied their knowledge to real-world sustainability challenges. Figure 5 provides visual evidence of student engagement in bioplastic experimentation, data analysis, and knowledge communication, thereby illustrating how this module deepened their practical understanding of sustainable polymer chemistry and its real-world implications.

Posters from two student groups in module 1 – plastic smart city: group 1 illustrates their initial ideas (what they think), field-based findings (what they found), and proposed solutions for plastic waste management (what they propose) (left); and group 2 presents similar outputs, reflecting their understanding of smart city concepts and sustainable practices (right).

To substantiate the effectiveness of the OEC-Circle program on each module, Figure 6 presents consolidated visual evidence of individuals and groups of student learning and engagement across all three modules. These visuals offer concrete examples of how students applied chemistry knowledge, engaged in real-world inquiry, and reflected on sustainability concepts – thereby directly supporting the stated learning outcomes.

Post-test Session: Upon completion of the three-week OEC-Circle program, a post-test session was conducted to evaluate students’ learning gains and attitudinal shifts resulting from their participation. This session included two assessment instruments. First, a 60 min conceptual post-test, identical in structure and content to the pre-test, was administered using a 21-item multiple-choice format to ensure consistency in measuring students’ chemistry understanding. This test aimed to capture knowledge acquisition and assess the effectiveness of the instructional interventions implemented across all three modules. Immediately following the conceptual test, students completed a 10-min, 50-item, 5-point rating scale questionnaire, known as the chemistry version of the Colorado Learning Attitudes about Science Survey (CLASS-Chem) 15 (Supplementary Material 2). This validated instrument was used to measure students’ attitudes toward chemistry learning, including their interest, confidence, and perceived relevance of chemistry to real-world issues. Together, these assessments provided a comprehensive evaluation of both cognitive and affective learning outcomes achieved through the OEC-Circle program.

An example of digital evidence obtained from students’ learning outcome in module 2 – circular plastic economy, recorded via the nQuire platform: observer details, time, and geolocation of the observation (left); and photographic evidence, plastic type identification, and notes on plastic circularity (right).

Practical activities from module 3 – sustainable polymer: thermal imaging of a thermoplastic heating investigation by students (left); and a bioplastic formulation experiment and producing molded bioplastic keychains produced by students (right).

A screen example of the interactive 360-degree video lesson.

Student work samples showing the diversity of connections made between plastics and issues in the community and the world: (A) incorporating ideation about plastic smart city within their local community; (B) investigating plastics and circularity behaviors in their local community hosting; (C) experimenting with bioplastic formulation and degradation in a laboratory setting; (D) presenting scientific understanding on how polymer formed using video clip; and (E) presenting final idea on circular plastic economy via exhibition.

4.5 Program evaluation

In the realm of educational research, measuring students’ progress via pre-test and post-test assessments is a common approach to determining the effectiveness of a particular instructional intervention. The success of the program was evaluated with the use of a 21-item multiple-choice conceptual chemistry test, and it was administered to all 32 students to complete in 60 min as a pre-test and post-test, which was taken before and after the program intervention. To examine the program efficacy, a data set was not normally distributed (p = 0.000) which also showed that the means were not equivalent. Therefore, non-parametric statistics of paired-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank test were used to compare a significant difference in their chemistry understanding between the pre-test and post-test scores. Evidence of learning from the Wilcoxon test comparing the pre-test and post-test revealed a distinct progression of students’ plastic-related chemistry understanding. The result shows a statistically significant difference (Z = −4.873, p < 0.01) between the pre-test (Mean = 11.28, SD = 2.23) and post-test (Mean = 17.09, SD = 1.35) scores in a large effect size (r > 0.8), which underscores the magnitude of the program intervention’s impact as displayed in Table 3.

Descriptive statistics and Wilcoxon sign test results comparing students’ pre-test and post-test chemistry understanding scores.

| Measurement | N | Mean rank | Rank sum | Z | p-Value | r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative rank | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −4.873 | 0.000a | −0.86 |

| Positive rank | 31 | 16.00 | 496.00 | |||

| Tie | 1 | |||||

| Total | 32 |

-

a p ≤ 0.001 indicates a significant change from the pre-test to post-test.

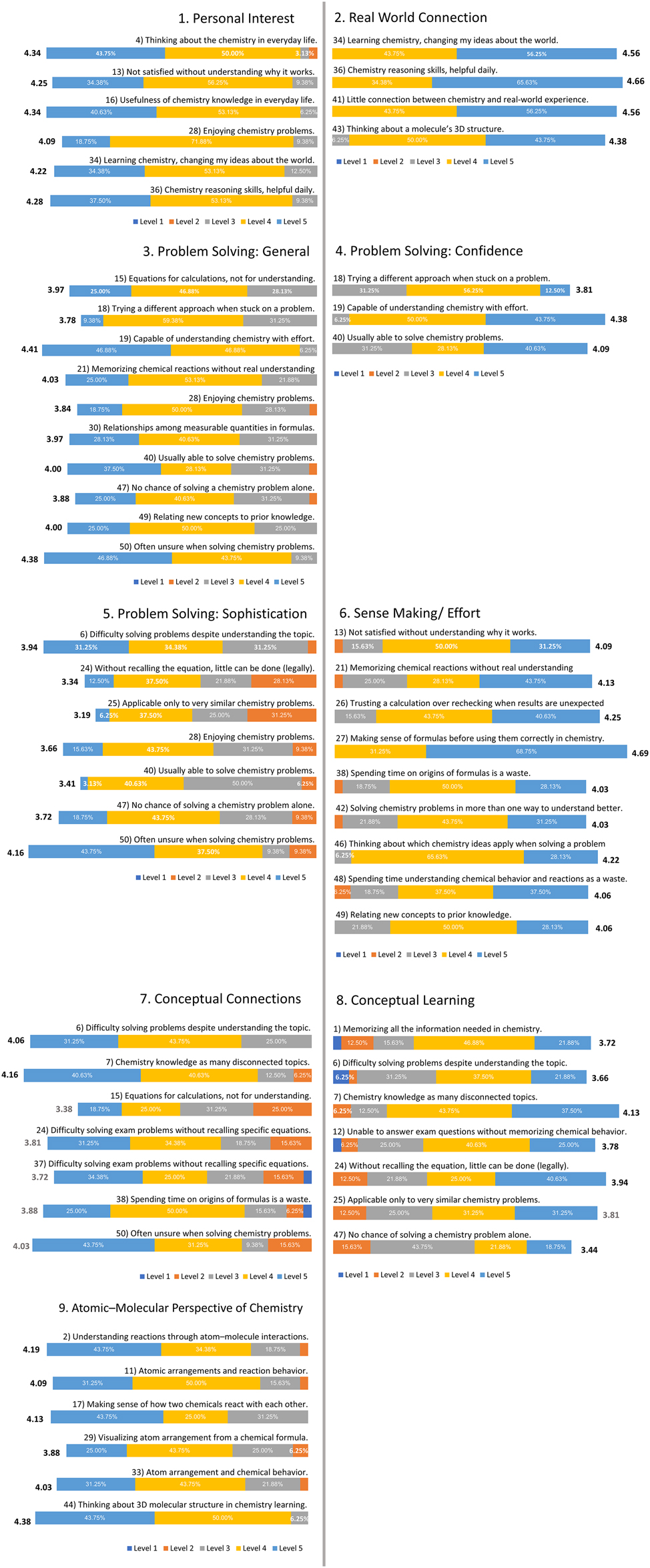

In addition to ensuring effective content delivery through the program structure, measuring students’ scientific attitudes emerged as a progressively significant consideration. The CLASS-Chem was also administered immediately to them after finishing the OEC-Circle program. To visualize their learning attitude toward the program intervention, descriptive statistics, i.e., arithmetic mean, standard deviation, frequency, and percentage were used to analyze post-test questionnaire scores. The post-test results of students’ learning attitudes toward chemistry, as measured by the CLASS-Chem revealed a significant positive shift across several key areas. A majority of students exhibited increased interest and engagement in the subject, with 50 % (n = 16) reporting that they thought about chemistry in their everyday lives, reflecting a stronger personal connection to the material. Additionally, 56.25 % (n = 18) of students felt that learning chemistry helped them understand its real-world applications, demonstrating the success of the program in making chemistry more relevant and practical. In the area of Problem Solving, 43.75 % (n = 14) of students expressed greater confidence in their ability to tackle chemistry problems, particularly those related to sustainability and plastic chemistry. Furthermore, 50 % (n = 16) of students reported improved problem-solving confidence, indicating that the program enhanced their ability to approach complex challenges. The Sense Making/Effort section also showed a positive impact, with 43.75 % (n = 14) of students indicating that they dedicated more time and effort to understanding challenging chemistry problems, reflecting an increased commitment to deepening their understanding. Overall, the CLASS-Chem’s post-test results highlight the OEC-Circle program’s success in enhancing students’ interest, confidence, and problem-solving skills in chemistry, particularly by connecting the subject to real-world sustainability issues. These findings suggest that the program effectively fostered a positive shift in students’ attitudes toward chemistry. Figure 7 presents percentages of the students’ learning attitude about chemistry.

Percentages of the students’ learning attitude about chemistry.

Despite the overall success of the OEC-Circle program, several implementation challenges were noted. These included time constraints during transitions between activities, particularly when transitioning between field-based and laboratory-based activities, where some student groups required more time than anticipated for data analysis or experimental setup. To address these issues in future iterations, we recommend providing additional orientation time, incorporating scaffolded materials for diverse learners, and exploring modular or hybrid formats to enhance flexibility that provide more flexibility in pacing and support. These improvements can strengthen the program’s adaptability and effectiveness across broader educational contexts.

5 Discussions and conclusion

The results of this study indicate a significant positive impact of the OEC-Circle program on students’ chemistry conceptual understanding and their overall attitude toward the subject. The analysis revealed a notable improvement in students’ post-test scores, with a large effect size, suggesting that the OEC-Circle program was highly effective in enhancing students’ understanding of chemistry topics such as the circular plastic economy, sustainable polymers, and waste management. This finding is consistent with previous research indicating that outreach programs combining context-based approach with immersive inquiry-driven pedagogies significantly improve students’ conceptual understanding of chemistry. 12 , 13 In our case, the success appears to stem from the synergistic integration of the program’s thematic focus on sustainability, its community-based and lab-based structure, and inquiry-informed activities that engaged students in real-world problem solving. By engaging students in real-world sustainability challenges, the OEC-Circle program made abstract chemistry concepts more tangible, which contributed to a deeper and more meaningful understanding of the subject matter. 4 , 5 , 10 , 11 , 26 While the 60 min pre-/post-test is standard in Thai education, it may not suit all cultural or instructional contexts. For future implementations, especially in international or time-limited outreach settings, a shorter or modular version is recommended. This approach maintains diagnostic value while minimizing fatigue, enhancing engagement, and supporting the broader applicability and adaptability of the OEC-Circle program across diverse educational environments.

In addition to improvements in chemistry attitude, the CLASS-Chem’s survey results highlight a high level of student engagement and a positive outcome in attitudes toward chemistry. The OEC-Circle program effectively fostered not only enhanced chemistry knowledge but also a positive attitude toward chemistry concepts and problem-solving skills related to plastic chemistry and sustainability. These positive results in attitudes can be attributed to the incorporation of citizen inquiry and living laboratory approaches, which played a pivotal role in student engagement. Visual data and learning artefacts from Figures 3, 4, 5, and 6 provide additional evidence of student engagement in inquiry-based processes, such as field investigations, experimentation, ideation, and public presentation. These inquiry-informed experiences contributed meaningfully to learning, but they operated within the structured design of the OEC-Circle program as a whole. We therefore interpret the observed learning gains as a result of the integrated design, rather than attributing them solely to inquiry-based methods. The citizen inquiry approach, which emphasizes collaboration and community-driven projects, encouraged students to actively investigate real-world sustainability issues, 14 , 28 such as plastic waste management, in their school and local environments. This hands-on, inquiry-driven learning model enhanced their sense of ownership and responsibility towards addressing environmental problems, 27 thereby boosting their confidence in tackling complex chemistry-related challenges.

While the findings of this study demonstrate a positive impact on students’ conceptual understanding and attitudes toward chemistry, it is important to recognize that the source of this impact cannot be attributed solely to the outreach program format. The pedagogical strategies embedded within the program – particularly the integration of context-based instruction, citizen inquiry, and guided inquiry – are themselves well-supported by educational research as effective methods for enhancing learning outcomes. Therefore, it is likely that the observed improvements are the result of a synergistic interaction between the outreach setting and these pedagogical approaches. This study did not attempt to isolate the independent effects of each instructional component. Future research employing comparative or factorial designs is recommended to examine how specific pedagogical elements contribute to learning gains within both formal and outreach educational settings.

A recognized limitation of the current study is the absence of a control group, which restricts the ability to make direct comparisons between the integrated approach and more conventional methods. This limitation stemmed from the nature of the interventional voluntary, intensive science outreach camp where participants were self-selected into the program. Due to ethical and logistical constraints, random assignment or control group withholding was not feasible. Nonetheless, the study employed a combination of pre- and post-assessment, attitudinal surveys, and qualitative learning evidence to provide a robust and multifaceted evaluation of learning outcomes. Additionally, this study did not isolate the independent effects of specific pedagogical strategies such as guided or citizen inquiry. Future research employing factorial or quasi-experimental designs could examine the relative contributions of each instructional element within the outreach framework, and also to further validate the instructional effectiveness of context-based approach and inquiry-driven chemistry education.

In conclusion, the OEC-Circle program demonstrated significant educational benefits by improving students’ chemistry understanding and fostering a positive attitude toward chemistry. These findings suggest that a carefully designed outreach chemistry program, incorporating sustainability-focused content, structured learning modules, and inquiry-informed activities, can effectively motivate students and enhance their engagement with real-world environmental challenges. Future research could focus on the effectiveness of teaching methods related to circular economy competencies within chemistry curricula. There is a recognized need for studies that explore the relationship between educational approaches and the transfer of knowledge regarding sustainable practices. Moreover, the development of curricula that incorporate themes of green chemistry education and sustainable chemistry education remains essential for advancing chemistry education in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express our appreciation to all the secondary school students involved in this study. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Faculty of Education, Khon Kaen University, and the Digital Education and Learning Engineering Association, Thailand.

-

Research ethics: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Khon Kaen University Ethics Committee, Thailand, with the No. HE663075, and informed consent was obtained from all individual participants.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization, methodology, resources, supervision, writing – review and editing: Niwat Srisawasdi; resources, supervision: Pawat Chaipidech; formal analysis and investigation, resources, writing – original draft preparation: Banjong Prasongsap. All authors read and approved of the final manuscript. The final manuscript was read and approved by all the authors.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT to improve the readability and language of the work and not to replace key authoring tasks in producing scientific and pedagogic insights and drawing scientific conclusions. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the content of the publication.

-

Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts to declare.

-

Research funding: The authors declare no competing financial interest.

-

Data availability: The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

1. Andrady, A. L. The Plastic in Microplastics: A Review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 119 (1), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.01.082.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Ellen MacArthur Foundation. A New Plastics Economy: Rethinking the Future of Plastics; Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2019. https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/publications/a-new-plastics-economy-rethinking-the-future-of-plastics.Search in Google Scholar

3. Boyd, D. A. Safer and Greener Polymer Demonstrations for STEM Outreach. ACS Polym. Au. 2021, 1 (2), 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1021/acspolymersau.1c00019.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Wissinger, J. E.; Visa, A.; Saha, B. B.; Matlin, S. A.; Mahaffy, P. G.; Kümmerer, K.; Cornell, S. Integrating Sustainability into Learning in Chemistry. J. Chem. Educ. 2021, 98 (4), 1061–1063. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.1c00284.Search in Google Scholar

5. Burmeister, M.; Eilks, I. An Example of Learning About Plastics and Their Evaluation as a Contribution to Education for Sustainable Development in Secondary School Chemistry Teaching. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2012, 13 (1), 93–102. https://doi.org/10.1039/C1RP90067F.Search in Google Scholar

6. Rauch, F. Education for Sustainable Development and Chemistry Education. In Worldwide Trends in Green Chemistry Education; Zuin, V.; Mammino, L., Eds.; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 16–26.10.1039/9781782621942-00016Search in Google Scholar

7. Nguyen, T. P. L. Integrating Circular Economy into STEM Education: A Promising Pathway Toward Circular Citizenship Development. Front. Educ. 2023, 8, 1063755. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1063755.Search in Google Scholar

8. Summerton, L.; Clark, J. H.; Hurst, G. A.; Ball, P. D.; Rylott, E. L.; Carslaw, N.; Creasey, J.; Murray, J.; Whitford, J.; Dobson, B.; Sneddon, H. F.; Ross, J.; Metcalf, P.; McElroy, C. R. Industry-Informed Workshops to Develop Graduate Skill Sets in the Circular Economy Using Systems Thinking. J. Chem. Educ. 2019, 96 (12), 2959–2967. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.9b00257.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Ting, J. M.; Ricarte, R. G.; Schneiderman, D. K.; Saba, S. A.; Jiang, Y.; Hillmyer, M. A.; Bates, F. S.; Reineke, T. M.; Macosko, C. W.; Lodge, T. P. Polymer Day: Outreach Experiments for High School Students. J. Chem. Educ. 2017, 94 (11), 1629–1638. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.6b00767.Search in Google Scholar

10. Noll, J.; Leven, F.; Limberg, J.; Weidmann, C.; Ostermann, R. Electrospinning as a Fascinating Platform for Teaching Applied Polymer Science with Safe and Sustainable Experiments. J. Chem. Educ. 2024, 101 (9), 3936–3943. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.4c00504.Search in Google Scholar

11. Herrera Monegro, R.; Graham, S. R.; Steele, J.; Robertson, M. L.; Henderson, J. A. Hands-On Activity Illustrating the Sorting Process of Recycled Waste and Its Role in Promoting Sustainable Solutions. J. Chem. Educ. 2024, 101 (5), 1899–1904. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.3c01128.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Jegstad, K. M. Inquiry-Based Chemistry Education: A Systematic Review. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2023, 60 (2), 251–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057267.2023.2248436.Search in Google Scholar

13. Singha, R.; Singha, S. Application of experiential, inquiry-based, problem-based, and project-based learning in sustainable education. In Teaching and Learning for a Sustainable Future: Innovative Strategies and Best Practices; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, 2024; pp. 109–128.10.4018/978-1-6684-9859-0.ch006Search in Google Scholar

14. Collier, K. M.; McCance, K.; Jackson, S.; Topliceanu, A.; Blanchard, M. R.; Venditti, R. A. Observing Microplastics in the Environment Through Citizen-Science-Inspired Laboratory Investigations. J. Chem. Educ. 2023, 100 (5), 2067–2079. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.2c01078.Search in Google Scholar

15. Barbera, J.; Adams, W. K.; Wieman, C. E.; Perkins, K. K. Modifying and Validating the Colorado Learning Attitudes About Science Survey for Use in Chemistry. J. Chem. Educ. 2008, 85 (10), 1435–1439. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed085p1435.Search in Google Scholar

16. Lathwesen, C.; Eilks, I. Can You Make It Back to Earth? A Digital Educational Escape Room for Secondary Chemistry Education to Explore Selected Principles of Green Chemistry. J. Chem. Educ. 2024, 101 (8), 3193–3201. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.4c00149.Search in Google Scholar

17. Mellor, K. E.; Coish, P.; Brooks, B. W.; Gallagher, E. P.; Mills, M.; Kavanagh, T. J.; Simcox, N.; Lasker, G. A.; Botta, D.; Voutchkova-Kostal, A.; Kostal, J.; Mullins, M. L.; Nesmith, S. M.; Corrales, J.; Kristofco, L.; Saari, G.; Steele, W. B.; Melnikov, F.; Zimmerman, J. B.; Anastas, P. T. The Safer Chemical Design Game. Gamification of Green Chemistry and Safer Chemical Design Concepts for High School and Undergraduate Students. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2018, 11 (2), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/17518253.2018.1434566.Search in Google Scholar

18. Lees, M.; Wentzel, M. T.; Clark, J. H.; Hurst, G. A. Green Tycoon: A Mobile Application Game to Introduce Biorefining Principles in Green Chemistry. J. Chem. Educ. 2020, 97 (7), 2014–2019. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00363.Search in Google Scholar

19. Nugraheni, A. R. E.; Srisawasdi, N. Development of Pre-Service Chemistry Teachers’ Knowledge of Technological Integration in Inquiry-Based Learning to Promote Chemistry Core Competencies. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2025, 26, 398–419. https://doi.org/10.1039/d4rp00160e.Search in Google Scholar

20. Iglesias-Gonzalez, N.; Ramírez, P.; Lorenzo-Tallafigo, J. From a Hazardous Waste to a Commercial Product: Learning Circular Economy in the Chemistry Lab. J. Chem. Educ. 2024, 101 (8), 3485–3492. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.4c00509.Search in Google Scholar

21. Araripe, E.; Zuin Zeidler, V. G. Advancing Sustainable Chemistry Education: Insights From Real-World Case Studies. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2024, 9, 100436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crgsc.2024.100436.Search in Google Scholar

22. Zuin Zeidler, V. Digitalization Paving the Ways for Sustainable Chemistry: Switching on More Green Lights. Science 2024, 384, eadq3537. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.eadq3537.Search in Google Scholar

23. Juntunen, M. K.; Aksela, M. K. Education for Sustainable Development in Chemistry – Challenges, Possibilities and Pedagogical Models in Finland and Elsewhere. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2014, 15 (4), 488–500. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4RP00128A.Search in Google Scholar

24. Murray, A.; Skene, K.; Haynes, K. The Circular Economy: An Interdisciplinary Exploration of the Concept and Application in a Global Context. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140 (3), 369–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2693-2.Search in Google Scholar

25. Liu, J.; Hu, Z.; Du, F.; Tang, W.; Zheng, S.; Lu, S.; An, L.; Ding, J. Environment Education: A First Step in Solving Plastic Pollution. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1130463. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2023.1130463.Search in Google Scholar

26. Lindstrom, T.; Middlecamp, C. Campus as a Living Laboratory for Sustainability: The Chemistry Connection. J. Chem. Educ. 2017, 94 (8), 1036–1042. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.6b00624.Search in Google Scholar

27. Sharples, M.; Scanlon, E.; Ainsworth, S.; Anastopoulou, S.; Collins, T.; Crook, C.; Jones, A.; Kerawalla, L.; Littleton, K.; Mulholland, P.; O’Malley, C. Personal Inquiry: Orchestrating Science Investigations Within and Beyond the Classroom. J. Learn. Sci. 2014, 24 (2), 308–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2014.944642.Search in Google Scholar

28. Herodotou, C.; Aristeidou, M.; Sharples, M.; Scanlon, E. Designing Citizen Science Tools for Learning: Lessons Learnt from the Iterative Development of nQuire. Res. Pract. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2018, 13 (1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41039-018-0072-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Buck, L. B.; Bretz, S. L.; Towns, M. H. Characterizing the Level of Inquiry in the Undergraduate Laboratory. J. Coll. Sci. Teach. 2008, 38, 52–58.Search in Google Scholar

30. Levonis, S. M.; Tauber, A. L.; Schweiker, S. S. 360° Virtual Laboratory Tour with Embedded Skills Videos. J. Chem. Educ. 2021, 98 (2), 651–654. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c01074.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Clemons, T. D.; Fouché, L.; Rummey, C.; Lopez, R. E.; Spagnoli, D. Introducing the First Year Laboratory to Undergraduate Chemistry Students with an Interactive 360° Experience. J. Chem. Educ. 2019, 96 (7), 1491–1496. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.9b00076.Search in Google Scholar

32. Nadelson, L. S.; Scaggs, J.; Sheffield, C.; McDougal, O. M. Integration of Video-Based Demonstrations to Prepare Students for the Organic Chemistry Laboratory. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2015, 24 (4), 476–483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-014-9535-3.Search in Google Scholar

33. Ardisara, A.; Fung, F. M. Integrating 360° Videos in an Undergraduate Chemistry Laboratory Course. J. Chem. Educ. 2018, 95 (10), 1881–1884. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.8b00143.Search in Google Scholar

34. Fung, F. M.; Choo, W. Y.; Ardisara, A.; Zimmermann, C. D.; Watts, S.; Koscielniak, T.; Blanc, E.; Coumoul, X.; Dumke, R. Applying a Virtual Reality Platform in Environmental Chemistry Education to Conduct A Field Trip to an Overseas Site. J. Chem. Educ. 2019, 96 (2), 382–386. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.8b00728.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/cti-2025-0009).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- Non-formal chemistry learning: a scoping review

- Research Article

- Discussion on definition and understanding of the thermodynamic spontaneous process

- Good Practice Report

- A molecular motion-based approach to entropy and application to phase transitions and colligative properties

- Research Articles

- Interrelationship of differential changes of thermodynamic potentials in a system in which a reaction takes place intending to obtain useful work in isentropic conditions–lectures adapted to sensing learners

- A role-playing tabletop game on laboratory techniques and chemical reactivity: a game-based learning approach to organic chemistry education

- Predominant strategies for integrating digital technologies in the training of future chemistry and biology teachers

- Enhancing conceptual teaching in organic chemistry through lesson study: a TSPCK-Based approach

- Enhancing chemistry understanding and attitudes through an outreach education program on circular plastic economy: a case study with Thai twelfth-grade students

- Process oriented guided inquiry learning: a possible solution to improve high school students’ conceptual understanding of electrochemistry and attitude

- Good Practice Report

- Portable syringe kit demonstration of gas generating reactions for upper secondary school chemistry

- Research Article

- Determination of total hardness of water sample by titration using double burette method: an economical approach

- Good Practice Reports

- Interpretation of galvanic series when teaching metal corrosion

- Synthesis of valproic acid for medicinal chemistry practical classes

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- Non-formal chemistry learning: a scoping review

- Research Article

- Discussion on definition and understanding of the thermodynamic spontaneous process

- Good Practice Report

- A molecular motion-based approach to entropy and application to phase transitions and colligative properties

- Research Articles

- Interrelationship of differential changes of thermodynamic potentials in a system in which a reaction takes place intending to obtain useful work in isentropic conditions–lectures adapted to sensing learners

- A role-playing tabletop game on laboratory techniques and chemical reactivity: a game-based learning approach to organic chemistry education

- Predominant strategies for integrating digital technologies in the training of future chemistry and biology teachers

- Enhancing conceptual teaching in organic chemistry through lesson study: a TSPCK-Based approach

- Enhancing chemistry understanding and attitudes through an outreach education program on circular plastic economy: a case study with Thai twelfth-grade students

- Process oriented guided inquiry learning: a possible solution to improve high school students’ conceptual understanding of electrochemistry and attitude

- Good Practice Report

- Portable syringe kit demonstration of gas generating reactions for upper secondary school chemistry

- Research Article

- Determination of total hardness of water sample by titration using double burette method: an economical approach

- Good Practice Reports

- Interpretation of galvanic series when teaching metal corrosion

- Synthesis of valproic acid for medicinal chemistry practical classes