Morpholinium hydrogen sulfate (MHS) ionic liquid as an efficient catalyst for the synthesis of bio-active multi-substituted imidazoles (MSI) under solvent-free conditions

Abstract

Morpholinium hydrogen sulfate as an ionic liquid was employed as a catalyst for the synthesis of a biologically active series of multi-substituted imidazoles by a four-component reaction involving the combination of benzil with different aromatic aldehydes, ammonium acetate, and 1-amino-2-propanol under solvent-free conditions. The key advantages of this method are shorter reaction times, very high yield, and ease of processing. Furthermore, the resulting products can be purified by a non-chromatographic method and the ionic liquid catalyst is reusable. All of these novel compounds have been fully characterized from spectral data. The X-ray crystal structures of two representative molecules are also detailed.

1 Introduction

Imidazole scaffold compounds are very important heterocyclic molecules as they are essential components of many interesting natural products including amino acids, vitamin B12, the DNA base structure, purines, and histamine. Compounds containing an imidazole ring are also of great interest to organic chemists as they have extensive biological and pharmacological applications [1], [2], [3]. The capability and wide applicability of the imidazole pharmacophore may be due to its hydrogen bond donor–acceptor ability in addition to its high affinity for the metals that exist in many active sites of proteins [4], [5]. Anti-cancer drugs containing imidazole ring systems include mercaptopurine, which resists leukemia [6] and lepidiline type A and B that have significant cytotoxicity against many types of human cancer cell lines at micromolar concentrations [7]. Dacarbazine [8], zoledronic acid, tipifarnib, and azathioprine are also potent imidazole derivatives [9]. Imidazole derivatives, including clotrimazole, are selective inhibitors of nitric oxide (NO) synthase, targeting neurodegenerative, inflammation diseases, and tumors of the nervous system [5]. Other biological effects of imidazole pharmacophores are attributed to the downregulation of intracellular K+ and Ca2+ fluxes, and overlapping with translation initiation [10]. Imidazoles exhibit anti-bacterial [11], fungicidal [12], anti-parasitic, anti-inflammatory [13], anti-nociceptive, anti-convulsing [14], anti-hypertensive [15], and anti-depressant properties [16], [17], [18].

Multicomponent reactions (MCRs) are a distinctive class of synthetic organic processes. Because of the operational simplicity, atom-economy, structural diversity, and complexity of the molecules that can be prepared in these reactions, they have attracted much attention. MCRs have an increasing importance in medicinal and organic chemistry due to their various applications in diversity-oriented convergent preparation of complex molecules from simple and readily available substrates in a single vessel [19]. In this context, we decided to explore the effect of the ionic liquid morpholinium hydrogen sulfate (MHS) as a catalyst to facilitate a one-step synthesis of an extensive series of imidazole derivatives and to investigate their anti-inflammatory efficacy. An advantage of this protocol is that the ionic liquid used as a solvent can be removed by dissolution in water while the product is precipitated in high purity. Imidazole derivatives with benzene rings as substituents on each of the imidazole C atoms are quite common with the structures of 177 such compounds reported in the Cambridge structural database [20]. However, only four compounds, 2-(2-(2-nitrophenyl)-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-1-yl)-3-phenylpropan-1-ol [21], 2-(2-(4,5-diphenyl-2-p-tolyl-1H-imidazol-1-yl)-3-phenylpropan-1-ol [22], and the very closely related 4-[1-(2-hydroxypropyl)-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-yl]benzoic acid (5d) [23] and 1-[2,6-dichlorophenyl-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-1-yl]-propan-2-ol (5g) [24], have propanol substituents on the N-1 atom of the imidazole rings. The structure of a similar derivative with an N-1 bound phenylethanone substituent, 2-(2,4-bis(4-fluorophenyl)-5-phenyl-1H-imidazol-1-yl)-1-phenylethanone, has also been reported recently [25]. In addition, we have recently reported the preparations and some of the structures of a series of related imidazole substituents with ethanol substituents on the N-1 atom [26], [27], [28].

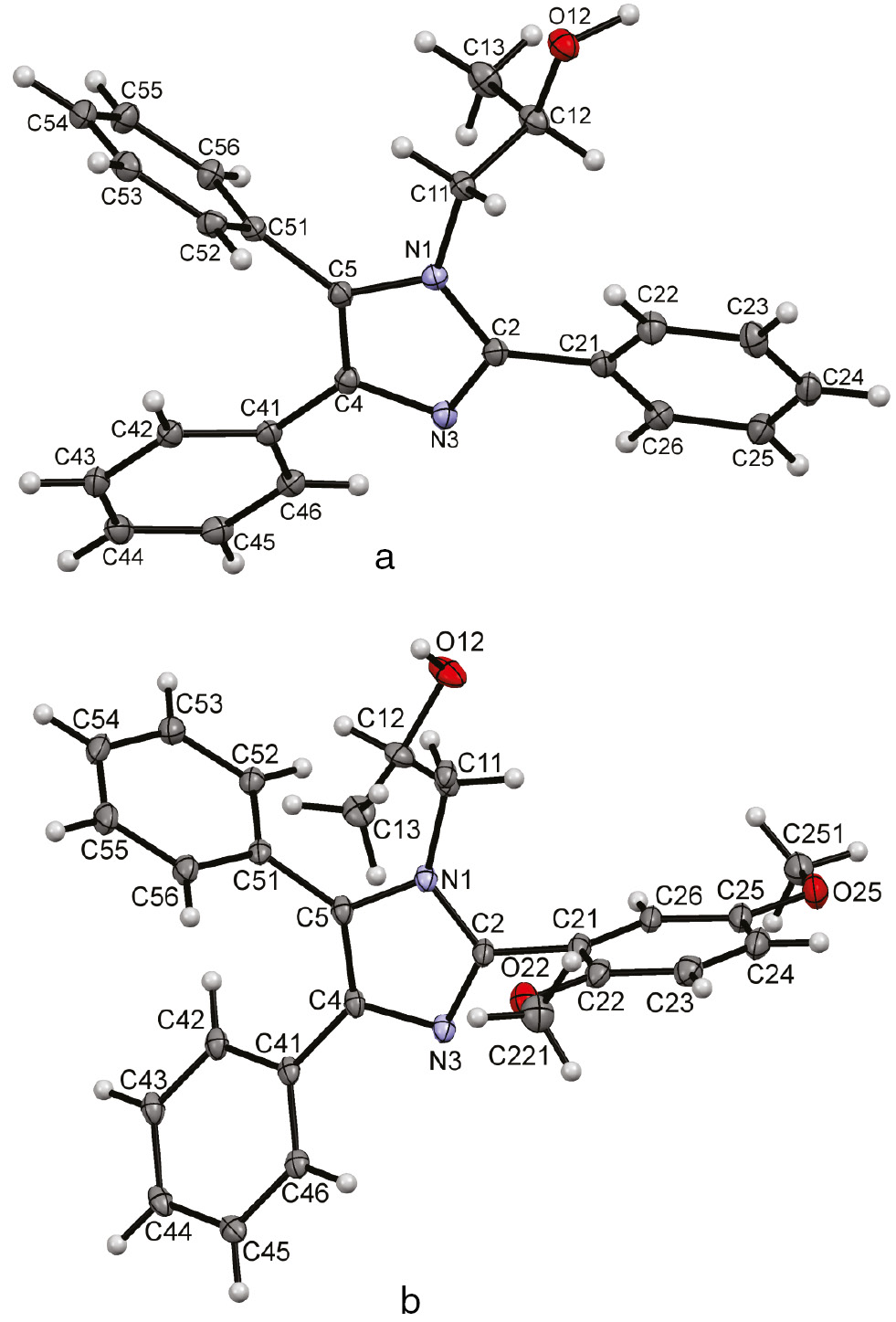

Because of the pharmaceutical potential of the compounds reported here, we have determined the crystal structures of two additional representative compounds, including the archetypal 1-(2,4,5-triphenyl-1H-imidazol-1-yl)propan-2-ol, and their molecular structures are detailed herein.

2 Results and discussion

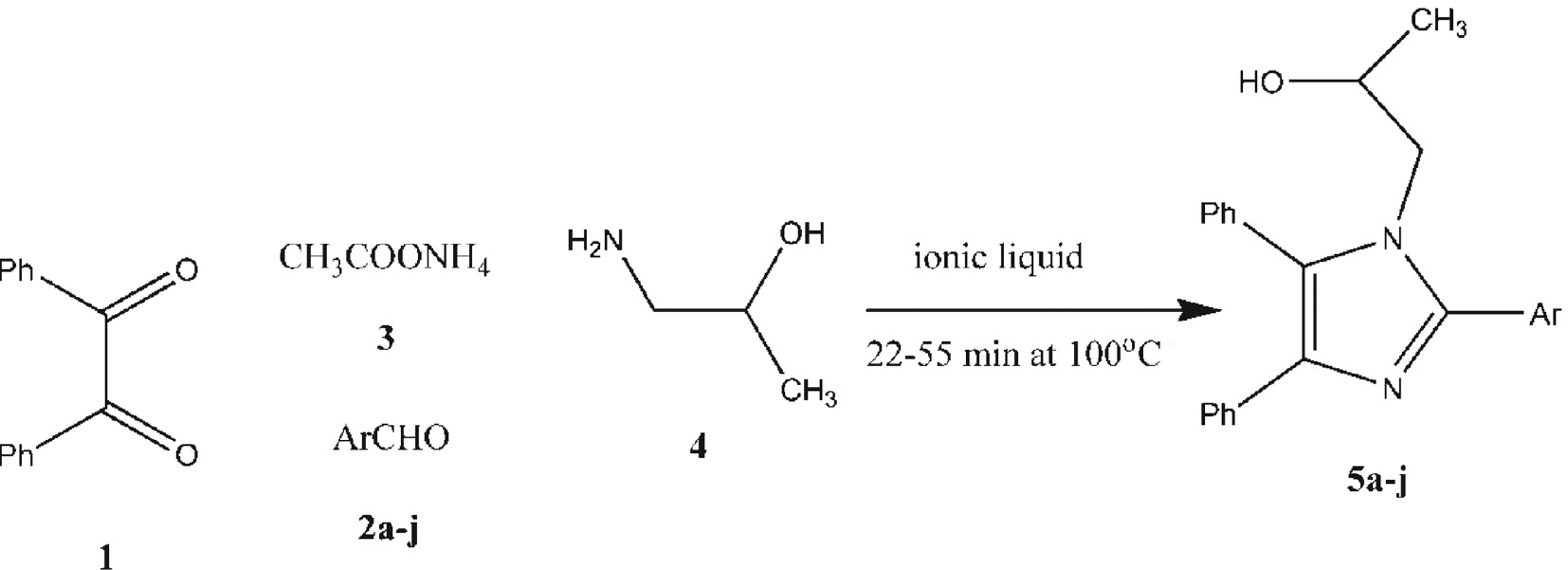

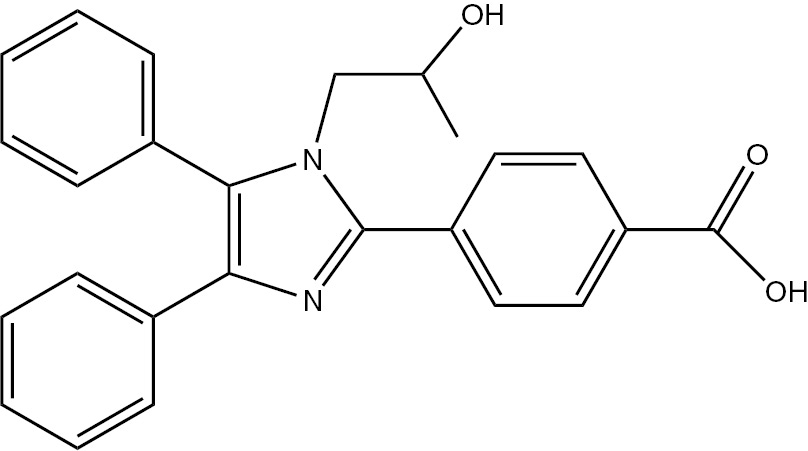

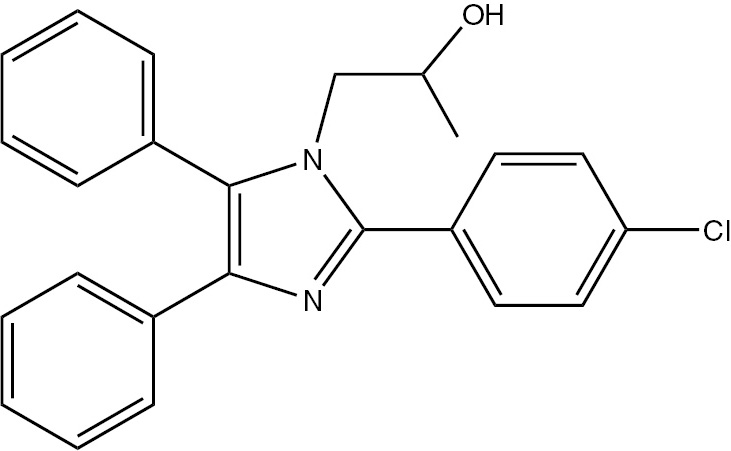

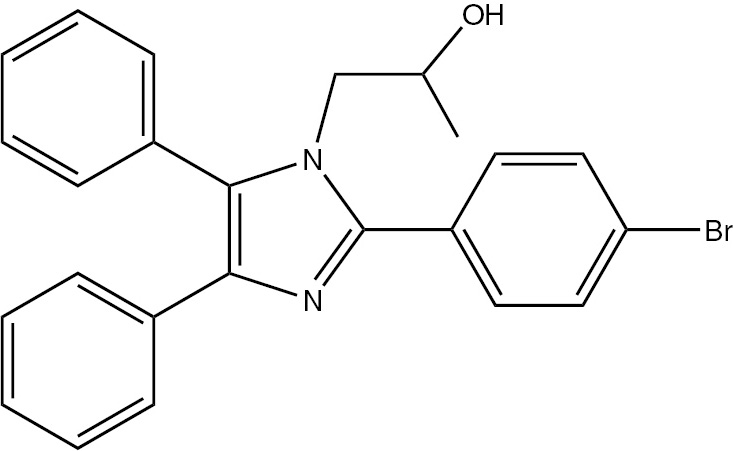

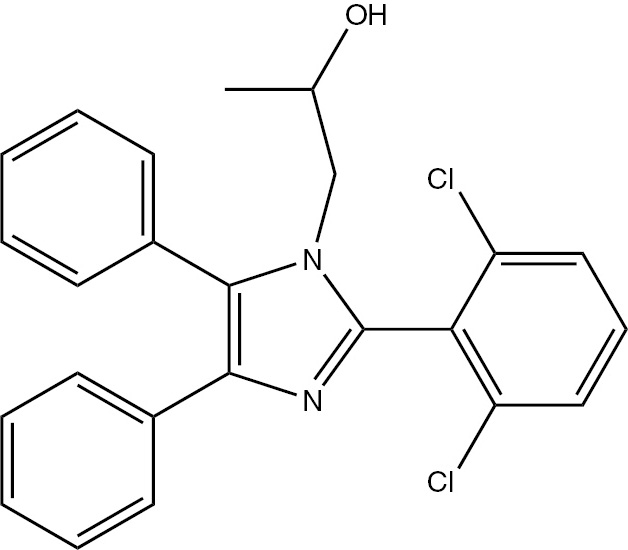

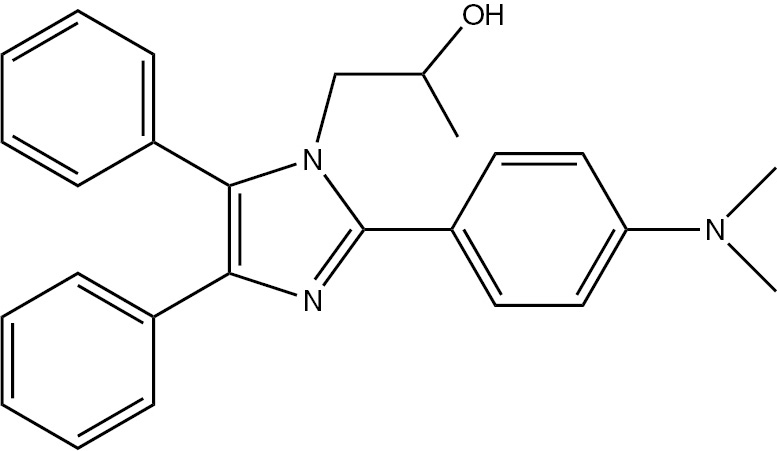

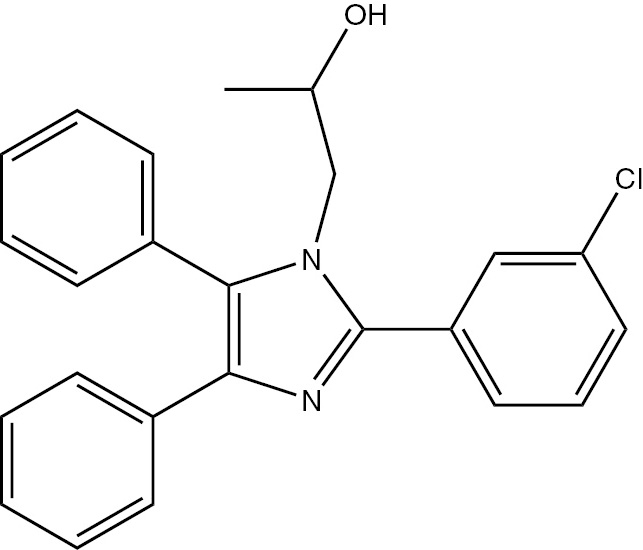

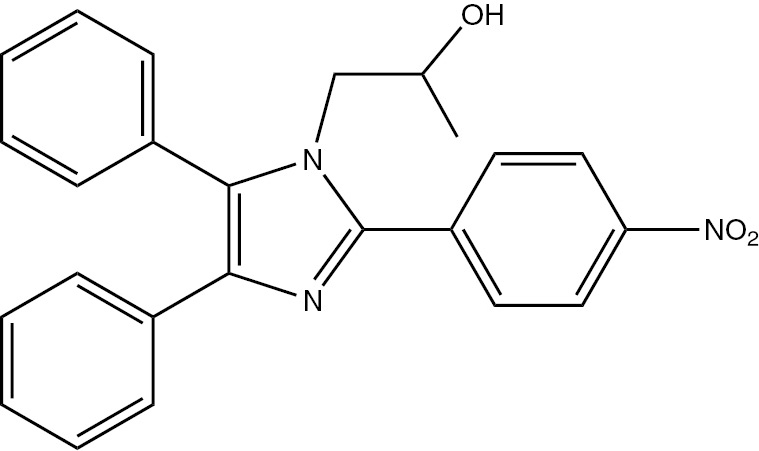

The synthesis of the multi-substituted 1,2,4,5-tetrasubstituted imidazoles 5a–j in excellent yields, by a simple, mild, expeditious, and an environmentally friendly method has been efficiently achieved via the reaction of benzil, 1, with the aromatic aldehydes 2a–j, ammonium acetate, 3, and 1-amino-2-propanol, 4, and using MHS as a catalyst under solvent-free conditions (Scheme 1, Table 1). All the new compounds were investigated by IR and NMR analysis, Moreover the structures of compounds 5a and 5c were confirmed by crystal structure determinations.

Synthesis of 1,2,4,5-tetrasubstituted imidazoles 5a–5j.

Morpholinium hydrogen sulfate catalyzed reactions for the synthesis of imidazoles 5a–j.

| Compound | Ar | Formula (mol. wt.) | Formula | M.p., °C | Time, min | Yield, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5a | Ph | C24H22N2O (354.44) |  | 177–179 | 25 | 96 |

| 5b | 3,4-(OCH3)2-C6H3 | C25H26N2O3 (414.50) |  | 140–142 | 35 | 93 |

| 5c | 2,5-(OCH3)2-C6H3 | C26H26N2O3 (414.50) |  | 250–252 | 40 | 95 |

| 5d | 4-COOH-C6H4 | C25H22N2O3 (398.45) |  | 206–208 | 35 | 94 |

| 5e | 4-Cl-C6H4 | C25H21ClN2O (388.89) |  | 194–196 | 35 | 93 |

| 5f | 4-Br-C6H4 | C25H21BrN2O (433.34) |  | 206–207 | 45 | 95 |

| 5g | 2,6-Cl-C6H3 | C24H20Cl2N2O (423.33) |  | 208–210 | 40 | 94 |

| 5h | 4-(CH3)2N-C6H4 | C26H27N3O (397.51) |  | 198–200 | 50 | 89 |

| 5i | 3-Cl-C6H4 | C24H21ClN2O (388.13) |  | 178–180 | 45 | 92 |

| 5j | 4-NO2-C6H4 | C24H21N3O3 (399.44) |  | 80–82 | 55 | 87 |

Having optimized the reaction conditions, we investigated the model reaction further by varying the amount of MHS catalyst. It was observed that 4 mol% of the catalyst gave the highest yield of 96% and increasing the amount of catalyst any further did not improve the yield (Table 2).

The amount of MHS catalyst for the synthesis of imidazole 5a.a

| Entryb | Catalyst, mol% | Yield, %a | Entryb | Catalyst, mol% | Yield, %a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 30 | 5 | 4 | 96 |

| 2 | 2 | 44 | 6 | 5 | 96 |

| 3 | 3 | 57 | 7 | 6 | 96 |

aIsolated yield based on 5a.

bReaction conditions: 1 (1 mmol), 2a (1 mmol), 3 (1 mmol), 4 (1 mmol).

We also tried different solvents such as water, ethanol, methanol, DMF, THF, DCM, 1,4-dioxane, MeCN, and toluene under similar reaction conditions. Invariably, this resulted in lower yields and extended reaction times in comparison to completing the reaction without additional solvent (Table 3).

Effect of solvent for the synthesis of imidazole 5a.a

| Solvent | Time, min | Yield, %a,b |

|---|---|---|

| Toluene | 190 | 60 |

| CHCl3 | 180 | 63 |

| DCM | 160 | 63 |

| EtOH | 90 | 88 |

| MeOH | 90 | 87 |

| H2O | 60 | 91 |

| Solvent-free | 45 | 98 |

aReaction conditions: 1 (1 mmol), 2a (1 mmol), 3 (1 mmol), 4 (1 mmol), and 4 mol% catalyst.

bIsolated yield based on 5a.

A general mechanism for the four-component cyclocondensation was proposed in our previous paper [26] and applies again here.

2.1 Molecular structures of 5a and 5c

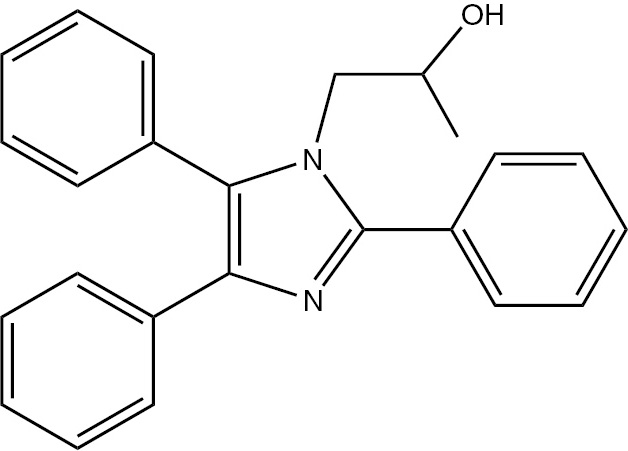

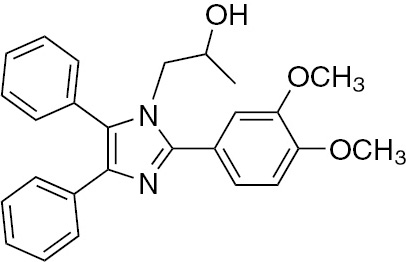

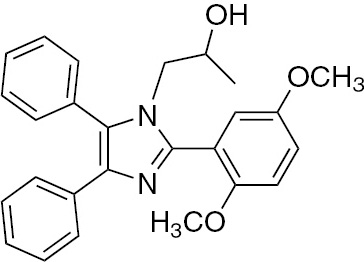

The molecular structures of 5a and 5c were determination by single-crystal X-ray diffraction (Fig. 1; and Experimental section). Table 4 summarizes characteristic dihedral angles between the imidazole and benzene rings of 5a and 5c.

The molecular structures of (a) 5a and (b) 5c in the crystal with the crystallographic atom numbering scheme adopted. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level. For clarity only the major disorder component of the disordered 2-hydroxypropyl substituent of 5c is shown.

Dihedral angles (deg) between the imidazole and benzene rings for 5a and 5c.a

| Compound | 1/2 | 1/3 | 1/4 | 1/5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5a | 83.97(12) | 26.13(13) | 33.62(12) | 67.45(8) |

| 5c | 71.8(2) | 84.09(10) | 28.84(16) | 67.99(12) |

aPlanes are numbered as follows: 1: N1,C2,N3,C4,C5; 2: N1,C11,C12, O12; 3: C21...C26; 4: C41…C46; 5: C51…C56.

2.2 Anti-inflammatory activity

The effect of the 10 new imidazoles reported here as anti-inflammatory agents was studied using the sulfated polysaccharide carrageenan and applying the standard carrageenan-induced paw edema method in rats. The method was applied to both male and female albino rats with weights in the range 160–190 g. The animals (pregnant female animals were excluded) were housed in cages made of stainless steel and divided into 15 groups each of six animals. Before the experiment, animals were fasted by depriving them of food but not water for 24 h (each rat was given 3 mL of water orally) to minimize the variability of the edema response. The imidazole compounds under investigation (10 mg kg−1 body weight) and indomethacin (as a reference standard) were suspended in saline solution using a small amount of Tween 80 as a surfactant to enhance wettability of the drug particles. Test and control groups were then given the saline solution orally 1 h before induction of inflammation.

Carrageenan paw edema was produced according to a modified method of Winter et al. [29]. After 1 h, 0.1 mL of freshly prepared 1% carrageenan solution in normal saline was injected subcutaneously into the subplantar region of the right hind paw of the rat (0.1 mL per rat). The rat’s right paw thickness was checked with a mercury electronic digital micrometer (LDM-150) at different time intervals, at zero time and 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 h after carrageenan induction. The edema was confirmed by observing the difference in thickness between injected and non-injected paws.

All data were calculated and analyzed quantitatively. Variables from normal distribution were referred to as means±standard error. The significant difference between groups was calculated by applying a one-way analysis of variance test followed by a post hoc test at P<0.05 and P<0.01.

The results were expressed as percentage of edema inhibition (OI, %) indicating the anti-inflammatory action. In other words, thickness in treated animals was compared with that in the control group and calculated using the following equation [30] (Table 5).

The effect of compounds 5a, 5c–j as anti-inflammatory agents by using carrageenan-induced paw edema in rats.a

| Inhibition of edema (%±standard error) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | 1 h | 2 h | 3 h | 4 h | 5 h |

| Control | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Indomethacin | 28.5±0.8 | 40±2b | 47±1 | 64±2b | 44±1 |

| 5a | 24.3±0.6 | 34±1 | 39±1 | 54±1 | 45.2±0.5 |

| 5c | 25±2 | 32±1 | 44±1 | 60±1 | 45±2 |

| 5d | 28.9±0.8 | 35.3±0.7 | 46±1 | 59±1 | 49±1 |

| 5e | 26±1 | 37±1 | 49±1 | 61±2b | 47±1 |

| 5f | 28±1 | 35.0±0.7 | 47.8±0.9 | 58±1 | 46.4±0.9 |

| 5g | 32±1 | 32±1 | 41±1 | 56±4b | 45±3b |

| 5h | 32±1 | 40±1 | 54±1 | 65±2 | 50.2±0.8 |

| 5i | 32±1 | 38±2b | 51±1 | 63±2 | 46±2b |

| 5j | 28.4±0.8 | 35.3±0.5 | 47±1 | 61.0±0.7 | 43±1 |

aAll results in the table are represented as the means of six experiments±standard error.

bIndicates a significant difference from the control value at P<0.05.

where VR is the mean thickness of the right paw, VL is the mean thickness of the left paw, (VR – VL)C is the mean increase in the thickness of the paws in the control group of rats, and (VR – VL)T is the mean increase in the thickness of the paws in rats treated with the compounds under investigation [31].

2.3 Anti-inflammatory results

The anti-inflammatory activity of the 10 synthesized compounds was estimated by monitoring carrageenan-induced paw edema in rats [32]. Generally, it has been observed (Table 5) that all of the compounds investigated exhibit considerable anti-inflammatory activity. In particular, however, compound 5h showed excellent anti-inflammatory properties (65.0% OI), somewhat better than the standard indomethacin (64.5% OI).

Comparing the activity of compounds 5d, 5e, 5f, and 5h that vary only by the nature of the substituents on the benzene ring at the 2-position of the imidazole ring reveals that a compound with a strong electron-donating substituent group, 4-N(CH3)2, as in 5h showed higher anti-inflammatory activity in comparison to those with electron-withdrawing substituents such as 4-COOH, 4-Cl, and 4-Br.

3 Conclusions

The presented technique is an operationally undeniable and environmentally friendly procedure for the synthesis of multi-substituted imidazoles using a catalytic amount of MHS. These have been fully characterized by spectroscopic methods and the X-ray crystal structures of 5a and 5c are also reported. MHS is a fairly efficient strong acidic catalyst for the synthesis of the substituted imidazoles. This protocol has obvious advantages including excellent yields, highly pure products, enhanced rapid reaction rates, and short reaction times. The procedures are compatible with a variety of different functional groups, the operation is simple, and work-up particularly easy. Also, MHS is a readily available, cheap, stable, reusable catalyst and importantly one that is environmentally acceptable. Hence, we believe that this method will find wide application in organic synthesis as well as industry. All of the imidazole derivatives showed some potential as alternative anti-inflammatory agents.

4 Experimental section

4.1 General

All chemical reagents and instruments were bought from Aldrich or Merck and used directly without further purification. Our products were characterized from spectroscopic data (FTIR, 1H and 13C NMR, and mass spectra) and melting points. A SHIMADZU FT-IR-8400s spectrometer was used to record IR spectra using KBr pellets. NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker (400 MHz) Ultrashield NMR spectrometer with [D6]DMSO as a solvent. The purity of the substances and progress of the reactions were monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and melting points recorded by the open capillary method using a Gallenkamp melting point apparatus and are uncorrected.

4.2 Synthesis of the catalytic ionic liquid MHS

Morpholine (20 mmol) was added to a 150-mL three-necked flask with a magnetic stirrer. Then an equimolar quantity of sulfuric acid (concentrated) was slowly added dropwise to the flask in an ice bath. The reaction mixture was then stirred at 80°C for overnight, washed with diethyl ether several times to separate out the non-ionic residues, and dried under vacuum using a rotary evaporator to yield MHS as a clear viscous liquid.

4.3 General procedure for the synthesis of 1,2,4,5-tetrasubstituted imidazoles (5a–5j) using MHS as an ionic liquid catalyst

Benzil (10 mmol), an aldehyde (2a–j) (10 mmol), ammonium acetate (10 mmol), and 1-amino-2-propanol (10 mmol) were added to MHS (4 mmol) in an oil bath at 25°C. The resulting mixture was refluxed at 100°C for the time reported in Table 1. The reaction progress was monitored by TLC until completion. The reaction mixtures were next washed with distilled water, and the resulting solid products purified in all cases by recrystallization from absolute ethanol.

4.3.1 1-(2,4,5-Triphenyl-1H-imidazol-1-yl)propan-2-ol (5a)

M.p. 177–179°C; yield 96%. – FTIR (KBr): ν=3265 (OH), 3062 (C–H), 2996 (C–H), 2840 (C–H), 1601 (C=N), 1456 (C=C), 1168, 1083, 838, 722, 697 cm−1. – 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO/D2O, TMS): δ=0.70 (d., 3H, CH3), 3.90 (d., 2H, CH2N), 3.92 (m., 1H, CH(OH)–CH3), 4.96 (s., 1H, OH), 7.03–7.7 (m., 15H, Ar-H) ppm. – 13C NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO/D2O): δ=21.24, 52.08, 65.05, 126.45, 126.73, 128.37, 128,84, 128.98, 129.12, 129.40, 129.83, 130.550, 131.60, 131.87, 132.26, 135.45, 137.17, 147.85 ppm. – Analysis for C24H22N2O (354.4): C 81.33, H 6.26, N 7.90; found C 81.05, H 6.63, N 7.09%.

4.3.2 1-(2-(3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl)-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-1-yl) propan-2-ol (5b)

Mp 140–142°C. FTIR (KBr, cm−1): 3356 (OH), 3059 (C–H), 2989 (C–H), 2895, 1604 (C=N), 1588 (C=C), 1475, 1242, 1189, 1057, 869, 741, 699; 1HNMR (DMSO-d6/D2O, 300 MHz): 0.69 (d., 3H, CH3-CH), 3.39 (tr., 2H, CH2N), 3.72 (m., 1H, CH2–CH(OH)–CH3), 3.83 (s., 6H, 2CH3O), 4.89 (s. br, 1H, CH2OH), 7.07–7.69 (m., 13H, Ar–H); 13C NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): 21.250, 52.210, 56.440, 56.890, 65.120, 114.670, 116.460, 117.670, 126.410, 126.590, 128.220, 129.210, 129.510, 131.650, 131.887, 136.876, 137.766, 147.126, 152.243, 154.897 ppm. DEPT 135 (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): 52.2100 (CH2) ppm. – Analysis for C26H26N2O3 (414.50): C 75.34, H 6.32, N 6.76; found C 75.19, H 6.18, N 6.95%.

4.3.3 1-(2-(2,5-Dimethoxyphenyl)-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-1-yl) propan-2-ol (5c)

M.p. 250–252°C; yield 95%. – FTIR (KBr): ν=3476 (OH), 3057(C–H), 2998 (C–H), 2895, 1604 (C=N) 1582 (C=C), 1476, 1241, 1184, 1066, 872, 735, 702 cm−1. – 1H NMR ([D6]DMSO/D2O, 400 MHz): δ=0.63 (d., 3H, CH3–CH), 3.37 (tr., 2H, CH2N), 3.56 (m., 1H, CH), 3.79 (s., 6H, 2CH3O), 4.76 (s. br, 1H, OH), 7.08–7.58 (m., 13H, Ar-H) ppm. – 13C NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δ=21.10, 51.87, 56.22, 56.78, 65.01, 113.85, 116.38, 118.32, 126.31, 126.58, 128.33, 129.03, 129.41, 131.53, 131.79, 136.79, 137.99, 147.11, 152.23, 154.77 ppm. – Analysis for C26H26N2O3 (414.50): C 75.34, H 6.32, N 6.76; found C 75.21, H 6.20, N 7.01%.

4.3.4 4-(1-(2-Hydroxypropyl)-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-yl)benzoic acid (5d)

M.p. 206–208°C; yield 94% [16]. – FTIR (KBr): ν=3356 (OH), 3078 (C–H), 2978(C–H), 1602 (C=N) 1503 (C=C), 1456, 1181, 1069, 860, 720, 696 cm−1. – 1H NMR [D6]DMSO/D2O, 400 MHz): δ=0.70 (d., 3H, CH3), 3.38 (m., 1H, CH), 3.92 (d., 2H, CH2N), 4.93(br., 1H, OH), 7.13–8.09 (m., 14H, Ar-H), 13.12 (s. br., 1H, COOH) ppm. – 13C NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δ=21.25, 52.97, 65.01, 126.68, 128.93, 129.36, 129.55, 129.91, 129.56, 131.58, 132.45, 136.68, 137.57, 138.48, 147.08, 168.12 ppm. – Analysis for C25H22N2O3 (398.45): C 75.36, H 5.57, N 7.03; found C 75.60, H 5.57, N 7.25%.

4.3.5 1-(2-(4-Chlorophenyl)-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-1-yl)propan-2-ol (5e)

M.p. 194–196°C; yield 93%. – FTIR (KBr): 3396 (OH), 3059 (C–H), 2970 (C–H), 2934 (C–H), 2856 (C–H), 1600 (C=N) 1502 (C=C), 1460, 1234, 1154, 1061, 840, 735, 698 cm−1. – 1H NMR ([D6]DMSO/D2O, 400 MHz): δ=0.69 (d., 3H, CH3), 3.36 (m., 1H, CH), 3.90 (d., 2H, CH2N), 4.95 (s. br., 1H, OH), 7.12–7.90 (m., 14H, Ar-H) ppm. – 13C NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δ=21.25, 52.12, 65.11, 126.53, 126.70, 128.30, 128.52, 129.21, 129.41, 131.32, 131.56, 134.25, 136.21, 138.73, 148.59 ppm. – Analysis for C24H21ClN2O (388.89): C 74.12, H 5.44, N 7.20; found C 74.06, H 5.58, N 7.47%.

4.3.6 1-(2-(4-Bromo)-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-1-yl)propan-2-ol (5f)

M.p. 206–208°C; yield 95%. – FTIR (KBr): ν=3434 (2OH), 3059 (C–H), 2996 (C–H), 2890 (C–H), 1601 (C=N) 1505 (C=C), 1467, 1173, 1078, 834, 709, 696 cm−1. – 1H NMR ([D6]DMSO/D2O, 400 MHz): δ=0.72 (d., 3H, CH3), 3.36 (m., 1H, CH), 3.85 (d., 2H, CH2N), 4.98 (s. br., 1H, OH), 7.10–7.80 (m., 14H, Ar-H) ppm. – 13C NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δ=20.80, 51.20, 65.60, 123.50, 126.61, 128.50, 129.54, 131.40, 131.69, 131.92, 134.90, 137.00, 137.20, 147.10 ppm. – Analysis for C24H21BrN2O (433.34): C 66.52, H 4.88, N 6.46; found C 66.80, H 5.22, N 6.81%.

4.3.7 1-(2-(2,6-Dichlorophenyl)-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-1-yl)propan-2-ol (5g)

M.p. 208–210°C; yield 94%. – FTIR (KBr): ν=3265 (OH), 3059 (C–H), 2962 (C–H), 2915 (C–H), 2856 (C–H), 1603 (C=N) 1501 (C=C), 1458, 1233, 1167, 1054, 831, 735, 695 cm−1. – 1H NMR ([D6]DMSO/D2O, 400 MHz): δ=0.72 (d., 3H, CH3), 3.37 (m., 1H, CH), 3.69 (d., 2H, CH2N), 4.79 (s. br., 1H, OH), 7.14–7.79 (m., 13H, Ar-H) ppm. – 13C NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δ=21.26, 55.60, 64.62, 126.42, 128.55, 128.52, 129.11, 129.69, 131.66, 135.18, 136.41, 137.33, 138.01, 143.23 ppm. – Analysis for C24H20Cl2N2O (423.33): C 68.09, H 4.76, Cl 16.75, N 6.62; found C 67.78, H 4.73, N 6.76%.

4.3.8 2-(2-(4-(Dimethylamino)phenyl)-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-1-yl)propan-2-ol (5h)

M.p. 198–200°C; yield 89%. – FTIR (KBr): ν=3340 (OH), 3062 (C–H), 3006 (C–H), 2895 (C–H), 1605 (C=N) 1567 (C=C), 1460, 1247, 1170, 1099, 856, 723, 696 cm−1. – 1H NMR ([D6]DMSO/D2O, 400 MHz): δ=0.69 (d., 3H, CH3–CH), 2.99 (s., 6H, (CH3)2N), 3.36 (m., 1H, CH), 3.89 (tr., 2H, CH2N), 4.89 (s. br., 1H, OH), 6.82 (d., 2H, Ar-H), 6.99–7.62 (m., 10H, Ar-H), 10 7.92 (d., 2H, Ar-H) ppm. – 13C NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δ=22.42, 52.78, 112.22, 118.97, 126.57, 128.43, 129.27, 129.68, 130.32, 131.43, 131.77, 135.40, 136.79, 148.77, 150.78 ppm. – Analysis for C26H27N3O (397.51): C 78.56, H 6.85, N 10.57; found C 78.73, H 7.00, N 10.39%.

4.3.9 1-(2-(3-Chlorophenyl)-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-1-yl)propan-2-ol (5i)

M.p. 149–151°C; yield 92%. – FTIR (KBr): ν=3234 (OH), 3056 (C–H), 2955 (C–H), 2879 (C–H), 1601 (C=N) 1504 (C=C), 1443, 1223, 1152, 1073, 857, 736, 697 cm−1. – 1H NMR ([D6]DMSO/D2O, 400 MHz): δ=0.72 (d., 3H, CH3), 3.38 (m., 1H, CH), 3.89 (d., 2H, CH2N), 5.00 (s. br., 1H, OH), 7.21–7.96 (m., 14H, Ar-H) ppm. – 13C NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δ=21.38, 52.06, 64.98, 126.84, 128.15, 128.52, 128.90, 129.25, 129.55, 130.82, 131.47, 133.83, 133.98, 135.02, 137.75, 143.34 ppm. – Analysis for C24H21ClN2O (388.89): C 74.12, H 5.44, N 7.20; found C 74.33, H 5.71, N 7.51%.

4.3.10 1-(2-(4-Nitrophenyl)-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-1-yl)propan-2-ol (5j)

M.p. 178–180°C; yield 87%. – FTIR (KBr): ν=3224 (2OH), 3059 (C–H), 2945 (C–H), 2879 (C–H), 1602 (C=N) 1502 (C=C), 1455, 1210, 1150, 1072, 857, 736, 694 cm−1. – 1H NMR ([D6]DMSO/D2O, 400 MHz): δ=0.75 (d., 3H, CH3), 3.35 (m., 1H, CH), 4.00 (d., 2H, CH2N), 5.00 (s. br., 1H, OH), 7.11 (d., 2H, Ar-H), 7.33–8.22 (m., 10H, Ar-H), 8.40 (d., 2H, Ar-H) ppm. – 13C NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δ=22.11, 52.75, 65.45, 124.18, 126.68, 128.58, 129.60, 130.44, 131.47, 132.13, 133.27, 135.92, 137.64, 147.13, 148.56 ppm. – Analysis for C24H21N3O3 (399.44): C 72.16, H 5.30, N 10.52; found C 71.99, H 5.25, N 10.80%.

4.4 X-ray structure determinations of 5a and 5c

Crystallographic data for 5a and 5c are listed in Table 6. The diffraction data were obtained on an Agilent SuperNova, Dual, Cu at zero, Atlas diffractometer using a mirror monochromator and CuKα radiation (λ=1.5418 Å). The data collection, cell refinement, data reduction, and absorption corrections were applied using Crysalis Pro [33]. The structures were both solved with Shelxs [34] and refined by full-matrix least squares on F2 using Shelxl-2014 [35] and Titan2000 [36]. All non-hydrogen atoms were assigned anisotropic displacement parameters. The H atoms of the hydroxyl groups of both molecules were located in difference Fourier maps and their coordinates refined with atomic displacement parameters set to 1.5 Ueq(O). All other H atoms were positioned geometrically and refined using a riding model with d(C–H)=0.95 Å for aromatic and 0.99 Å for CH2 with Uiso=1.2Ueq(C) and 0.98 Å, Uiso=1.5Ueq(C), for CH3 atoms. Although 5a and 5c both crystallized in non-centrosymmetric space groups, P212121 and P21, respectively, the absence of heavy atoms from the structures meant that the absolute configurations could not be determined from anomalous scattering effects. For 5c high and increasing atomic displacement parameters for the C12 and C13 atoms suggested disorder and these were split over to two positions with an occupancy ratio that converged at 0.525(19):0.475(19). All molecular plots and packing diagrams were drawn using Mercury [37]. Other calculations were performed using Platon [38] and tabular material was produced using WinGX [39].

Crystal data and structure refinement of 5a and 5c.

| 5a | 5c | |

|---|---|---|

| Empirical formula | C24H22N2O | C26H26N2O3 |

| Formula weight | 354.43 | 414.49 |

| Temperature, K | 100(2) | 100(2) |

| Wavelength, Å | 1.54184 | 1.54184 |

| Crystal system | Orthorhombic | Monoclinic |

| Space group | P212121 | P21 |

| a, Å | 5.87139(18) | 5.8136(3) |

| b, Å | 13.9289(5) | 15.2850(6) |

| c, Å | 22.7469(7) | 11.8329(6) |

| β, deg | 90 | 94.654(5) |

| V, A3 | 1860.29(10) | 1048.02(9) |

| Z | 4 | 2 |

| Dcalcd, g cm−3 | 1.266 | 1.313 |

| µ, mm−1 | 0.607 | 0.689 |

| F (000), e | 752 | 440 |

| Crystal size, mm3 | 0.40×0.35×0.20 | 0.437×0.275×0.121 |

| Refl. collected | 6235 | 5088 |

| Refl. unique | 3385 | 2985 |

| Rint | 0.0392 | 0.0478 |

| Refl. observed | 3175 | 2782 |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 3385/0/248 | 2985/1/306 |

| Final R1/wR2 [I>2σ(I)] | 0.0476/0.1263 | 0.0519/0.1368 |

| Final R1/wR2 (all data) | 0.0510/0.1299 | 0.0552/0.1418 |

| Goodness-of-fit | 1.014 | 1.038 |

| Flack x | 0.2(5) | −0.7(4) |

| Largest diff. peak/hole, e Å−3 | 0.405/−0.200 | 0.321/−0.241 |

| CCDC reference number | CCDC 1479433 | CCDC 1479434 |

CCDC 1479433 and CCDC 1479434 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the analytical service team (Helen Sutton, Paul Warren, and Saeed Gulzar) at Manchester Metropolitan University for providing the spectral results. They also thank the University of Otago for purchase of the Agilent diffractometer and the Chemistry Department, University of Otago, for support of the work of JS.

References

[1] H. R. Shaterian, M. Ranjbar, J. Mol. Liq.2011, 160, 40.10.1016/j.molliq.2011.02.012Suche in Google Scholar

[2] R. Breslow, Acc. Chem. Res.1995, 28, 146.10.1021/ar00051a008Suche in Google Scholar

[3] B. F. Mirjalili, A. H. Bamoniri, L. Zamani, Scientia Iranica C2012, 19, 565.10.1016/j.scient.2011.12.013Suche in Google Scholar

[4] M. Kidwai, S. Saxena, S. Rastogi, Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2005, 26, 2051.10.5012/bkcs.2005.26.12.2051Suche in Google Scholar

[5] B. Sammaiah, D. Sumalatha, S. Reddy, M. Rajeswari, L. Sharada, Int. J. Ind. Chem.2012, 3, 1.10.1186/2228-5547-3-1Suche in Google Scholar

[6] M. Bahnous, A. Bouraiou, M. Chelghoum, S. Bouacida, T. Roisnel, F. Smati, C. Bentchouala, P. C. Gros, A. Belfaitah, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.2013, 23, 1274.10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.01.004Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] C. Belwal, A. Joshi, Der Pharma Chemica2012, 4, 1873.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] M. Akkurt, S. K. Mohamed, A. A. E. Marzouk, V. M. Abbasov, F. Santoyo-Gonzalez, Acta Crystallogr.2013, E69, o988.10.1107/S1600536813014104Suche in Google Scholar

[9] W. Liu, W. Guo, J. Wu, Q. Luo, F. Tao, Y. Gu, Y. Shen, J. L. R. Tan, Q. Xu, Y. Sun, Biochem. Pharma. 2013, 85, 1504.10.1016/j.bcp.2013.03.008Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] A. H. El-Masry, H. H. Fahmy, S. H. Ali, Molecules2000, 5, 1429.10.3390/51201429Suche in Google Scholar

[11] S. Sridharan, N. Sabarinathan, S. A. Antony, Int. J. Chem. Tech. Res.2014, 6, 1220.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] A. Mohammadi, H. Keshvari, R. Sandaroos, B. Maleki, H. Rouhi, H. Moradi, Z. Sepehr, S. Damavandi, Appl. Catal. A2012, 429–430, 73.10.1016/j.apcata.2012.04.011Suche in Google Scholar

[13] D. Sharma, B. Narasimhan, P. Kumar, V. Judge, R. Narang, E. Clercq, J. Balzarini, Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 2347.10.1016/j.ejmech.2008.08.010Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] A. M. Pieczonka, A. Strzelczyk, B. Sadowska, G. Mlosto, P. Staczek, Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 64, 389.10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.04.023Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] M. R. Grimmett, Imidazole and Benzimidazole Synthesis, Academic Press, London, 1997.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] K. Vikrant, M. Ritu, S. Neha, Res. J. Chem. Sci.2012, 2, 18.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] F. Hatamjafari, H. Khojastehkouhi, Orient. J. Chem.2014.30, 329.10.13005/ojc/300143Suche in Google Scholar

[18] S. D. Sharma, P. Hazarika, D. Konwar, Tetrahedron Lett.2008, 49, 2216.10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.02.053Suche in Google Scholar

[19] L. Weber, Curr. Med. Chem. 2002, 9, 2085.10.2174/0929867023368719Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] C. R. Groom, I. J. Bruno, M. P. Lightfoot, S. C. Ward, Acta Crystallogr.2016, B72, 171.10.1107/S2052520616003954Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Y. Li, P. Mao, Y. Xiao, L. Yang, L. Qu, Acta Crystallogr.2014, 70, o621.10.5428/pcar20140210Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Y. Xiao, L. Yang, K. He, J. Yuan, P. Mao, Y. Xiao, L. Yang, K. He, J. Yuan, P. Mao, Acta Crystallogr. 2012, E68, o264.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] J. P. Jasinski, S. K. Mohamed, M. Akkurt, A. A. Abdelhamid, M. R. Albayati, Acta Crystallogr.2015, E71, o77.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] M. Akkurt, J. P. Jasinski, S. K. Mohamed, A. A. Marzouk, M. R. Albayati, Acta Crystallogr.2015, E71, o299.10.1107/S2056989014027133Suche in Google Scholar

[25] S. Pusch, T. Opatz, Org. Lett.2014, 16, 5430.10.1021/ol502667hSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] S. K. Mohamed, J. Simpson, A. A. Marzouk, A. H. Talybov, A. A. Abdelhamid, Y. A. Abdullayev, V. M. Abbasov, Z. Naturforsch. B2015, 70, 809.10.1515/znb-2015-0067Suche in Google Scholar

[27] S. K. Mohamed, M. Akkurt, A. A. Marzouk, V. M. Abbasov, A. V. Gurbanov, Acta Crystallogr.2013, E69, o474.10.1107/S1600536813004285Suche in Google Scholar

[28] A. A. Marzouk, V. M. Abbasov, A. H. Talybov, Chem. J.2012, 2, 179.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] C. A. Winter, E. A. Risley, G. W. Nuss, Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med.1962, 111, 544.10.3181/00379727-111-27849Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] H. Nojima, H. Tsuneki, L. Kimura, M. Kimura, Br. J. Pharmacol.1995, 116, 1680.10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb16391.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] M. E. Shoman, M. Abdel-Aziz, O. M. Aly, H. H. Farag, M. A. Morsy, Eur. J. Med. Chem.2009, 44, 3068.10.1016/j.ejmech.2008.07.008Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] H. H. Cong, V. N. Khaziakhmetova, L. E. Zigashina, Int. J. Risk Safety Med. 2015, 27(Suppl 1), S76.10.3233/JRS-150697Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] CrysAlis Pro Software System, Intelligent Data Collection and Processing Software for Small Molecule and Protein Crystallography, Agilent Technologies Ltd., Yarnton, Oxfordshire (UK) 2013.Agilent Technologies Ltd.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] G. M. Sheldrick, Acta Crystallogr.2008, A64, 112.10.1107/S0108767307043930Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] G. M. Sheldrick, Acta Crystallogr.2015, C71, 3.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] K. A. Hunter, J. Simpson, Titan2000, University of Otago, Otago (New Zealand) 1999.University of OtagoSuche in Google Scholar

[37] C. F. Macrae, I. J. Bruno, J. A. Chisholm, P. R. Edgington, P. Mccabe, E. Pidcock, L. Rodriguez-Monge, R. Taylor, J. van de Streek, P. A. Wood, J. Appl. Crystallogr.2008, 41, 466.10.1107/S0021889807067908Suche in Google Scholar

[38] A. L. Spek, Acta Crystallogr.2009, D65, 148.10.1107/S090744490804362XSuche in Google Scholar

[39] L. J. Farrugia, J. Appl. Crystallogr.2012, 45, 849.10.1107/S0021889812029111Suche in Google Scholar

Article note:

Multicomponent green synthesis, biological and structural investigation of multi-substituted imidazoles. Part 2. Part 1: S. K. Mohamed, J. Simpson, A. A. Marzouk, A. H. Talybov, A. A. Abdelhamid, Y.A. Abdullayev, V. M. Abbasov, Z. Naturforsch.2015, 70b, 809–817.

©2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Invariom-based comparative electron density studies of iso-sildenafil and sildenafil

- A norterpenoid and tripenoids from Commiphora mukul: isolation and biological activity

- Formiside and seco-formiside: lignin glycosides from leaves of Clerodendrum formicarum Gürke (Lamiaceae) from Cameroon

- Morpholinium hydrogen sulfate (MHS) ionic liquid as an efficient catalyst for the synthesis of bio-active multi-substituted imidazoles (MSI) under solvent-free conditions

- A highly selective fluorescent chemosensor based on naphthalimide and Schiff base units for Cu2+ detection in aqueous medium

- Synthesis and crystal structure of a cyanido-bridged copper(II)–silver(I) bimetallic complex containing a trimeric {[Ag(CN)2]−}3 anion, [Cu(Dach)2-Ag(CN)2-Cu(Dach)2][Ag(CN)2]3 (Dach=cis-1,2-diaminocyclohexane)

- Two highly acetylated sterols from the marine sponge Dysidea sp.

- New oxaphenalene derivative from marine-derived Streptomyces griseorubens sp. ASMR4

- Hydrogenium-bis-hydrogensulfate anions adjacent to [S2O7]2− in Rb3[S2O7][H(HSO4)2]: a structural evidence of the increasing acidity of polysulfuric acids with growing chain length

- High-pressure synthesis and crystal structure of In3B5O12

- The high-pressure phase of CePtAl

- Note

- Synthesis and structural characterization of Mn(II) and Cu(II) complexes with bis(4-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)phenyl)methanone ligands

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Invariom-based comparative electron density studies of iso-sildenafil and sildenafil

- A norterpenoid and tripenoids from Commiphora mukul: isolation and biological activity

- Formiside and seco-formiside: lignin glycosides from leaves of Clerodendrum formicarum Gürke (Lamiaceae) from Cameroon

- Morpholinium hydrogen sulfate (MHS) ionic liquid as an efficient catalyst for the synthesis of bio-active multi-substituted imidazoles (MSI) under solvent-free conditions

- A highly selective fluorescent chemosensor based on naphthalimide and Schiff base units for Cu2+ detection in aqueous medium

- Synthesis and crystal structure of a cyanido-bridged copper(II)–silver(I) bimetallic complex containing a trimeric {[Ag(CN)2]−}3 anion, [Cu(Dach)2-Ag(CN)2-Cu(Dach)2][Ag(CN)2]3 (Dach=cis-1,2-diaminocyclohexane)

- Two highly acetylated sterols from the marine sponge Dysidea sp.

- New oxaphenalene derivative from marine-derived Streptomyces griseorubens sp. ASMR4

- Hydrogenium-bis-hydrogensulfate anions adjacent to [S2O7]2− in Rb3[S2O7][H(HSO4)2]: a structural evidence of the increasing acidity of polysulfuric acids with growing chain length

- High-pressure synthesis and crystal structure of In3B5O12

- The high-pressure phase of CePtAl

- Note

- Synthesis and structural characterization of Mn(II) and Cu(II) complexes with bis(4-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)phenyl)methanone ligands