A novel crystallographic location of rattling atoms in filled Eu x Co4Sb12 skutterudites prepared under high-pressure conditions

-

João Elias F. S. Rodrigues

, Javier Gainza

, Federico Serrano-Sánchez

, Norbert M. Nemes

, Oscar J. Dura

, Jose Luis Martínez

und Jose Antonio Alonso

Abstract

Thermoelectric M

x

Co4Sb12 skutterudites are well-known to exhibit a reduced thermal conductivity thanks to the rattling effect of the M-filler at the large cages occurring in the framework, centered at the 2a sites of the

1 Introduction

A strong motivation for researching within the appealing field of Thermoelectric Materials (TM) is that about two thirds of energy production (at a global level) is dissipated as heat with no profit. Yet, TMs are able to directly transform a thermal gradient into electric energy [1], [2], [3], [4]. Designing novel TMs is challenging since three antagonistic properties must be optimized: they require high Seebeck voltages (S, thermoelectric power), low electrical resistivity (ρ), and low thermal conductivity (κ). TMs are typically semiconductors and so ρ is coupled to κ through the electronic contribution, κ e, since the same carriers are involved in both mechanisms, and to their S due to the Pisarenko relation. TMs are characterized by a dimensionless Figure of Merit (ZT = S 2 T/ρκ); the best ZTs are around 1–2, depending on temperature (T). Currently, commercial TMs are made of chalcogenide semiconductors like PbTe or Bi2Te3. Both contain Te; a scarce and expensive element (one part per billion on earth crust).

Instead of chalcogenides, some metal pnictides perform well as TMs, in particular AX3 skutterudites. They derive their name from the mineral CoAs3; the structure can host different transition metals (Fe, Co, Rh, Ir…) at A position, and pnictide elements (P, As, Sb) as X atoms [3]. Skutterudites are cubic, defined in the space group

Additionally, the structural analysis from high-angular resolution synchrotron X-ray diffraction (SXRD) unveils interesting features of these compounds. The so-called “Oftedal plots” [16], determined by the antimony positional parameters (y and z) as a function of the filling fraction, ionic state and atomic radius of the filler, yield an interesting view of the distortion of [Sb4] rings contained in the structure, closely linked to the band-convergence concept and its influence on the thermoelectric transport properties [16], [17], [18], [19].

Eu-filled skutterudites have been barely described since the first structural report on a compound Eu x Co4Sb12 [20]. In this work, we describe a Eu-filled skutterudite, Eu x Co4Sb12−δ prepared under high-pressure conditions, where high-angular resolution SXRD data disclosed a novel crystallographic position for the Eu rattling atoms, at 12d (x, 0, 0) sites, which combined with a conspicuous Sb deficiency leads to a substantial reduction of the thermal conductivity in this thermoelectric material.

2 Experimental procedures

A sample with nominal composition Eu0.5Co4Sb12 was prepared by a solid-state reaction under moderate temperature and high-pressure conditions. About 1.2 g of a stoichiometric mixture of the starting elements Eu (99.0%), Co (99%, ROC/RIC), and Sb (99.5%, Alfa-Aesar) were carefully ground and placed in a niobium capsule (5 mm in diameter), sealed and introduced inside a cylindrical graphite heater. To prevent oxidation, the capsule was properly manipulated inside an Argon-filled glove box. Reactions were carried out in a piston-cylinder press (Rockland Research Co.), at a pressure of 3.5 GPa, at 800 °C for 1 h. Afterwards, the products were quenched to room temperature and the pressure was released. The samples were obtained as hard pellets, which were partially ground to powder for structural characterization, or cut with a diamond saw as bar-shaped pellets to perform transport measurements.

Phase characterization was carried out using X-ray diffraction (XRD) on a Bruker-AXS D8 diffractometer (40 kV, 30 mA), run by DIFFRACTPLUS software, in Bragg-Brentano reflection geometry with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å). The structural details were analyzed from temperature-dependent SXRD patterns collected at the MSPD-diffractometer at the ALBA synchrotron (Barcelona, Spain), in the high-angular resolution mode (MAD set-up) with an incident beam of 27 keV energy (λ = 0.45861 Å) [21]. The polycrystalline powder was contained in rotating quartz capillaries of 0.7 mm in diameter. SXRD patterns were collected at room temperature (RT, 295 K), 473, 673, 873 and 1023 K for the temperature-dependent analysis. The FullProf software was used to refine the structure [22] with the Rietveld method [23]. The zero-point error, scale factor, background coefficients, pseudo-Voigt shape parameters, atomic coordinates, and anisotropic displacements for the Co and Sb atoms were refined.

The Seebeck coefficient was measured using a commercial MMR-technologies system. Measurements were performed under vacuum (10−3 mbar) from room temperature up to 800 K. A constantan wire was employed as a reference for comparison with bar-shaped skutterudite samples cut with a diamond saw perpendicular to the pressing direction. The reproducibility was checked with different contacts and constantan wires.

A Linseis LFA 1000 instrument was used to measure the thermal diffusivity (α) of the samples over a temperature range of 300 ≤ T ≤ 800 K by the laser-flash technique. A thin graphite coating was applied to the surface of the pellet to maximize heat absorption and emissivity. The thermal conductivity (κ) is determined using κ = α·C p ·d, where C p is the specific heat and d is the sample density. Specific heat was calculated using the Dulong–Petit equation.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Structural characterization

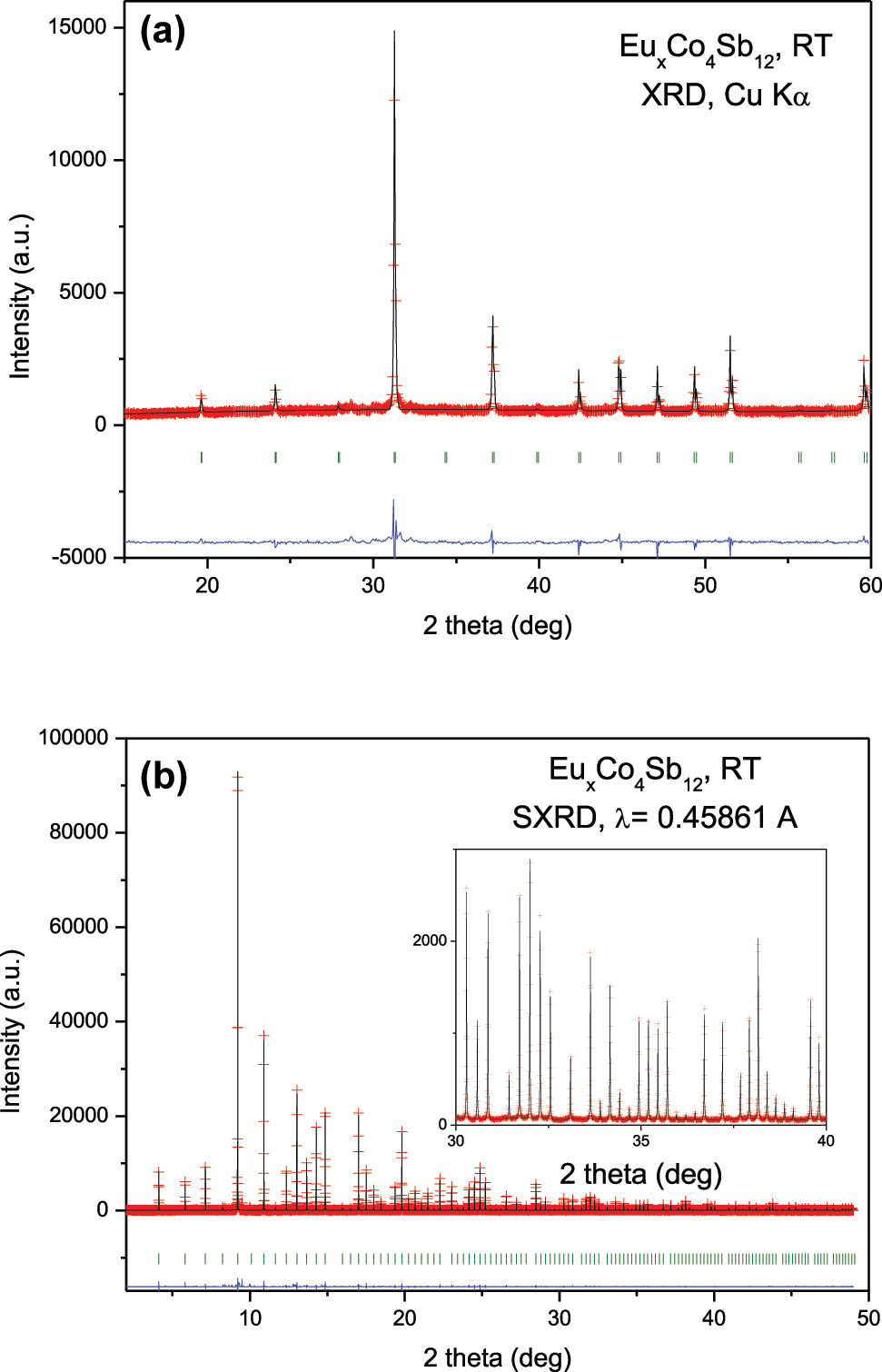

Preliminary characterization of Eu

x

Co4Sb12 was performed by laboratory XRD for some pellets ground into powder; a typical XRD pattern is shown in Figure 1a. The pattern corresponds to the skutterudite structure, defined in the space group

Rietveld plots from X-ray diffraction data: (a) Laboratory XRD pattern with Cu Kα radiation and (b) SXRD pattern for Eu x Co4Sb12 at room temperature (x = 0.02(1)). The inset shows the quality of the fit in the high-angle region. Experimental points (red crosses), calculated profile (black line), difference (blue line), and Bragg reflections (green symbols).

The high angular resolution of SXRD data was essential to thoroughly investigate the structural features of Eu0.5Co4Sb12 nominal composition. The crystal structure was refined in the skutterudite

![Figure 2:

Views of the skutterudite unit cell: (a) Difference Fourier map showing yellow regions with positive scattering density at 12d sites. (b) View of the skutterudite crystal structure, consisting of a framework of [CoSb6] octahedra sharing vertices, with Eu atoms located in the large cages left in between. Eu are found to be statistically occupying 12d sites, conforming regular octahedra centered at 2a (0, 0, 0) positions.](/document/doi/10.1515/zkri-2022-0051/asset/graphic/j_zkri-2022-0051_fig_002.jpg)

Views of the skutterudite unit cell: (a) Difference Fourier map showing yellow regions with positive scattering density at 12d sites. (b) View of the skutterudite crystal structure, consisting of a framework of [CoSb6] octahedra sharing vertices, with Eu atoms located in the large cages left in between. Eu are found to be statistically occupying 12d sites, conforming regular octahedra centered at 2a (0, 0, 0) positions.

Structural parameters of Eu x Co4Sb12 prepared under high-pressure conditions, obtained from SXRD data at 295 K.

| Crystal data | |

| a = 9.03647(2) Å | V = 737.90(1) Å3 |

| Z = 2 | |

| Refinement | |

|---|---|

| R p = 11.79% | R wp = 20.19% |

| R exp = 5.58% | R Bragg = 2.07% |

| χ 2 = 6.43 | |

| Fractional atomic coordinates and isotropic or equivalent isotropic displacement parameters (Å 2 ) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | x | y | z | U iso*/U eq | Occ. (<1) | |

| Co | 8c | 1/4 | 1/4 | 1/4 | 0.0060(4) | |

| Sb | 24g | 0 | 0.33488(7) | 0.15792(7) | 0.0077(4) | 0.996(4) |

| Eu | 12d | 0.23(2) | 0 | 0 | 0.02(1)* | 0.0033(18) |

| Atomic displacement parameters (Å2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U 11 | U 22 | U 33 | U 12 | U 13 | U 23 | |

| Co | 0.0060(4) | 0.0060(4) | 0.0060(4) | 0.0004(5) | 0.0004(5) | 0.0004(5) |

| Sb | 0.0067(3) | 0.0089(4) | 0.0075(4) | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.0009(3) |

Figure 2b displays a view of the Eu x Co4Sb12 crystal structure, highlighting the framework of corner-sharing, heavily tilted [CoSb6] octahedra. The Eu atoms were found statistically distributed at high multiplicity 12d sites, with a weak occupancy. This contrasts with the usually described filling of the 2a cages in skutterudites, in oversized cages where the filler elements are described to rattle, thus acting as a sink for phonons and, therefore, drastically reducing the lattice component of the thermal conductivity. In the present case, the Eu filler is also in this cage but it is found to be out of center, delocalized in an octahedral configuration within the cavity left in between each 8 [CoSb6] octahedra. This configuration determines two types of Eu–Sb distances, at 1.71(1) and 3.10(1) Å. It is evident that the first distance is unrealistic, but considering the weak Eu occupancy and the Sb vacancies in the structure, we can accept that the Eu presence in a certain position is coupled to a Sb vacancy, and thus, supporting this arrangement.

3.2 Thermal evolution

The thermal evolution of the crystal structure was determined from temperature-dependent SXRD patterns collected at 473, 673, 873 and 1023 K. The skutterudite framework is preserved up to 873 K, exhibiting the expected thermal expansion. Eu is located at 12d sites at 473 and 673 K, but at 873 K the Eu occupancy fades down. This reduced filling fraction reveals a segregation of the rare-earth element from the skutterudite framework, and it indicates a thermally activated reorganization of the atomic structure at high temperature, revealing the metastable nature of this compound prepared under high-pressure. Table S1 at the Supplementary Information includes the main structural parameters above RT, and Figure S2 illustrates the quality of the fits to the SXRD patterns at these temperatures. Finally, at 1023 K, a total decomposition of the skutterudite structure is observed, to give a mixture of Sb and CoSb2.

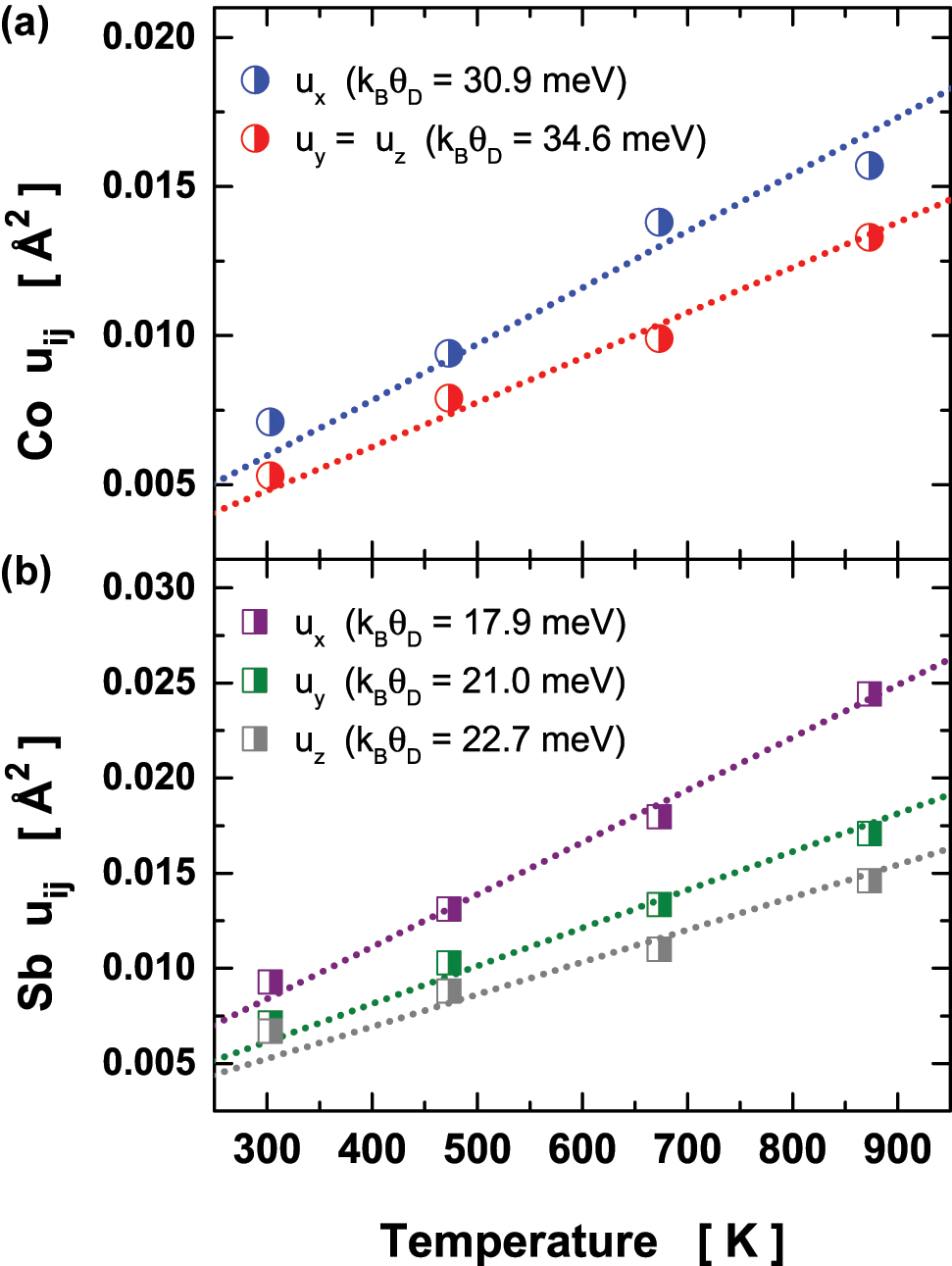

3.3 Debye model

Although the mean-square displacements (MSDs) of the Eu atoms were not properly derived from the Rietveld refinement, we have evaluated the lattice dynamics of Eu0.02(1)Co4Sb12 by following the thermal dependence of the anisotropic displacement parameters

such that,

The evaluation of the Debye temperature along diagonal elements of

3.4 Oftedal plots

As mentioned, the CoSb3 skutterudite structure (Figure 2b) mainly consists of a framework of corner-sharing [CoSb6] octahedra, so severely tilted that Sb atoms are at bonding distances in rectangular [Sb4] rings (Figure 4a). Therefore, there are two main covalent interactions: one between Co and Sb atoms, in [CoSb6] units, and the second one between every four Sb atoms, in the mentioned rings. These rings are characteristic of this type of structure [26], and the size and degree of distortion from the perfect square shape are determined by the y and z Sb positional parameters. The covalent interactions among pnictogen atoms have been analyzed in several works in terms of the electronic properties of the material, and this interaction is closely related to the band gap and valence band representation [19, 26].

Temperature dependence of the diagonal elements of the anisotropic displacements

As a consequence of the framework symmetry, there are only three main parameters to specify the structure: the lattice parameter a , and y and z atomic positions of Sb, besides the filling fraction (FF) or occupancy of the filler M atom (x). Figure 4b displays the evolution of the lattice parameters depending on the filling fraction of the 2a positions. This plot includes precedent materials prepared under the same high-pressure conditions, containing La, Ce, Sr, K, and Yb as filler elements [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]. All of them have been investigated by SXRD. The labels indicate the refined occupation of the filler. The main trend is a linear behavior with the filling fraction. The present Eu0.02(1)Co4Sb12 sample falls within this trend, slightly smaller in unit-cell parameter than Y0.02Co4Sb12, with the same occupancy, perhaps due to the different position exhibited by the rattling element: 12d for Eu and 2a for Y [16].

![Figure 4:

Features of the Eu

x

Co4Sb12 structure: (a) [Sb4] rings in the skutterudite structure, occurring because of the strong tilting of [CoSb6] octahedra. (b) Evolution of the unit-cell parameter of the skutterudite against the filling fraction, for specimens previously synthesized under high-pressure conditions (taken from Ref. [16]), where the Eu sample falls among the slightly filled materials.](/document/doi/10.1515/zkri-2022-0051/asset/graphic/j_zkri-2022-0051_fig_004.jpg)

Features of the Eu x Co4Sb12 structure: (a) [Sb4] rings in the skutterudite structure, occurring because of the strong tilting of [CoSb6] octahedra. (b) Evolution of the unit-cell parameter of the skutterudite against the filling fraction, for specimens previously synthesized under high-pressure conditions (taken from Ref. [16]), where the Eu sample falls among the slightly filled materials.

Figure 5a shows the Oftedal plot with different skutterudite compositions, prepared under high-pressure conditions. The Oftedal plot consists of a representation of the z versus y fractional positions of Sb within the crystal structure. The so-called Oftedal line with (y + z) = 0.5 corresponds to a perfectly square [Sb4] ring. We observed that the y and z parameters, determined from SXRD data, increase with the filling fraction, as it has been also described for other skutterudite compounds [27]. Our Eu specimen roughly falls within the observed trend regarding y and z values. Figure 5b represents the experimental (y + z) parameters with respect to the filling fraction. At first glance, the (y + z) magnitude behaves as the lattice parameter; however, there are important deviations. There is a pronounced effectiveness in reducing the rectangular distortion of the [Sb4] rings as the filling fraction increases. Previous studies on the contribution of an additional electronic band to carrier transport have shown an increasing valley degeneracy and improvements in the ratio of electrical conductivity and Seebeck coefficient [28]. These indicate a direct relation of the [Sb4] ring structural parameters with the energy difference of conduction bands. Particularly, a high band degeneracy is predicted for Sr-filled CoSb3 [29], exhibiting particularly good thermoelectric properties [16, 29]. Regarding Eu, its poor filling implies substantially distorted [Sb4] rings, and poor thermoelectric behavior, as described below.

![Figure 5:

Oftedal analysis, including other skutterudites: (a) Oftedal plot, including the Oftedal line (red line) for (y + z) = 0.5 and (b) (y + z) parameter against filling fraction (x or FF) for the differently filled skutterudites phases prepared under high-pressure. Single-filled skutterudite structural parameters of M

x

Co4Sb12 (M = La, Ce, K, Sr, Yb) correspond to high-pressure samples studied from SXRD data [13, 14, 16]. Eu0.02(1)Co4Sb12 roughly follows the observed trend.](/document/doi/10.1515/zkri-2022-0051/asset/graphic/j_zkri-2022-0051_fig_005.jpg)

Oftedal analysis, including other skutterudites: (a) Oftedal plot, including the Oftedal line (red line) for (y + z) = 0.5 and (b) (y + z) parameter against filling fraction (x or FF) for the differently filled skutterudites phases prepared under high-pressure. Single-filled skutterudite structural parameters of M x Co4Sb12 (M = La, Ce, K, Sr, Yb) correspond to high-pressure samples studied from SXRD data [13, 14, 16]. Eu0.02(1)Co4Sb12 roughly follows the observed trend.

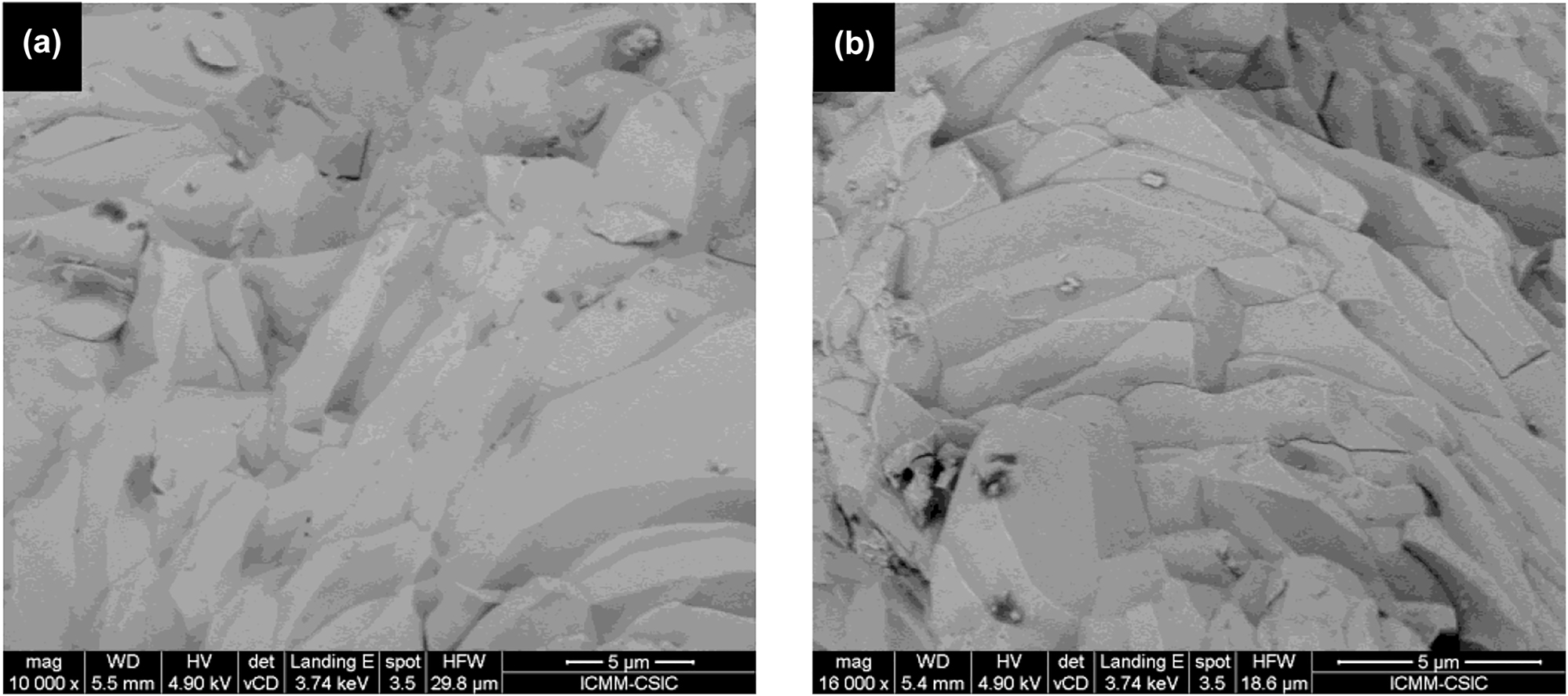

3.5 Scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM)

Grain boundary and morphology have been examined by FE-SEM to assess the compactness and homogeneity of the samples. Figure 6 illustrates two SEM images of Eu0.02(1)Co4Sb12 sample, showing large grains above 5 μm in size, and a highly compact microstructure, as well-sintered pellets resulting from the high-pressure synthesis. Figure S3 illustrates more views of the microstructure of this sample and Figure S4 contains the results of an EDX study, yielding Eu:Co:Sb ratios similar to those expected.

SEM micrographs of the as-grown pellets of Eu0.02(1)Co4Sb12. (a) ×10,000 and (b) ×16,000 magnification.

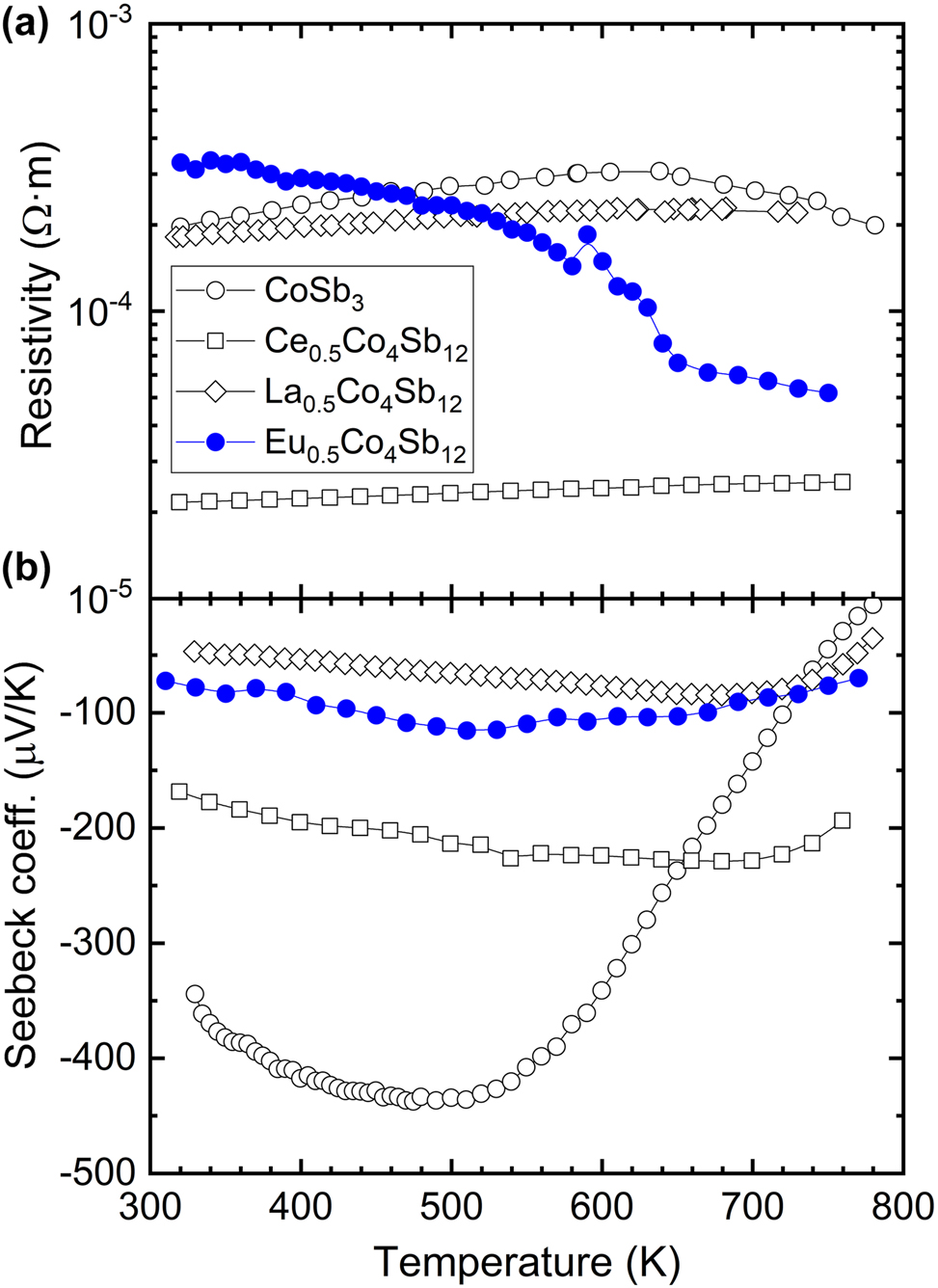

3.6 Thermoelectric properties

The electrical transport properties of the Eu0.02(1)Co4Sb12 are displayed in Figure 7a. The data of unfilled CoSb3−δ , Ce0.5- and La0.5- filled skutterudites prepared under the same high-pressure conditions [12], [13], [14] are shown for the sake of comparison. We can notice that, surprisingly, the resistivity of Eu0.02(1)Co4Sb12 at room temperature, ∼3 × 10−4 Ω m, is slightly higher than that of CoSb3. However, the resistivity of the Eu-doped filled compound is closer to that of Ce0.5Co4Sb12 as temperature increases, reaching a minimum of 5.2 × 10−5 Ω m at 750 K.

Temperature dependence of (a) resistivity and (b) Seebeck coefficient of Eu0.02(1)Co4Sb12. The additional compositions, in their nominal chemical formula, have been added for the sake of comparison, namely CoSb3 and M0.5Co4Sb12 (M = La, Ce).

The Seebeck coefficient is plotted in Figure 7b. Such a parameter always lies between 70 and 120 μV/K throughout the entire measured temperature range, similar to other filled skutterudites [14, 30–32]. The Seebeck coefficient for Eu0.02(1)Co4Sb12 is always higher than that measured for the La-filled compound, but it is also remarkably lower than that value for the nominal composition Ce0.5Co4Sb12.

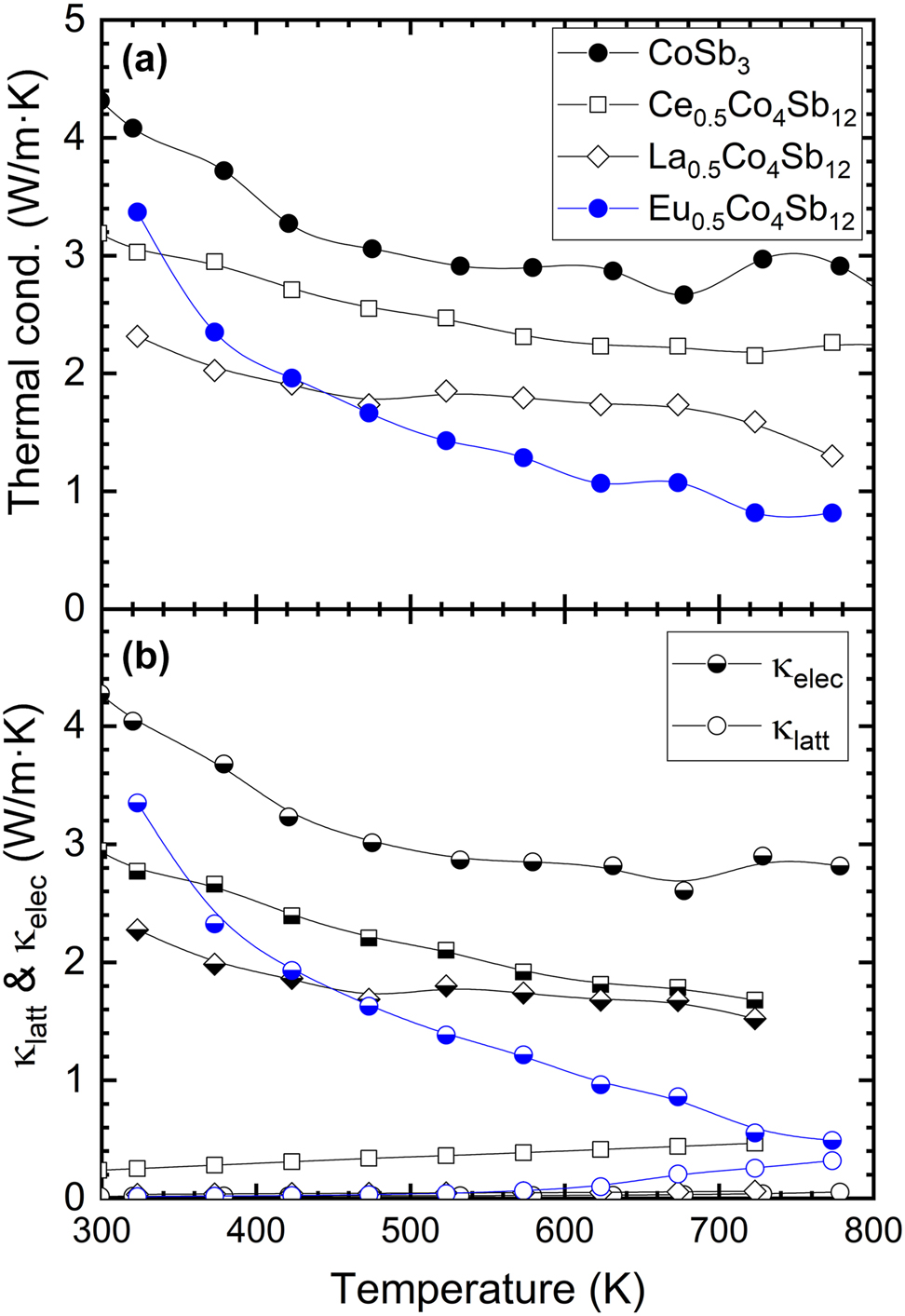

The thermal conductivity of Eu0.02(1)Co4Sb12 is shown in Figure 8a, together with data, for the sake of comparison, of similar skutterudites also synthesized under high-pressure [12], [13], [14]. The thermal conductivity of Eu-filled compound is lower at all temperatures than that of the unfilled skutterudite. It is worth noting that, at room temperature, its thermal conductivity is higher than that shown by the Ce- and La- filled skutterudites, which is probably due to the lower filling fraction reached by Eu in the CoSb3 structure (∼0.02(1)). However, as temperature increases, the Eu0.02(1)Co4Sb12 compound reaches the lowest thermal conductivity compared to the other compositions prepared by high-pressure synthesis, with a minimum value of 0.82 W m−1 K−1 from 723 up to 773 K. Moreover, these are extremely low compared to other single-filled CoSb3 derivatives [14, 30, 31], and thus, suggests a stark phonon scattering enhancement due to the distinctive crystallographic position of Eu atoms at 12d sites coupled with Sb vacancies. In fact, Eu-filled CoSb3 prepared by conventional methods still show lower lattice thermal conductivity at high temperature than other filled CoSb3, slightly above that reported here [33].

Temperature dependence of (a) total thermal conductivity and (b) its lattice and electronic contributions for Eu0.02(1)Co4Sb12. Additional compositions, in their nominal chemical formulae, have been added for the sake of comparison, namely CoSb3 and M0.5Co4Sb12 (M = La, Ce).

The two different contributions to the thermal conductivity, the lattice and the electronic parts, are displayed in Figure 8b. We can see that they follow the same trend than the total thermal conductivity, reaching a minimum value at 773 K. It can also be noticed that, for the case of Eu0.02(1)Co4Sb12, the electronic contribution is only relevant beyond 600 K, when the electrical resistivity of the compound is lower enough. Moreover, beyond this temperature it is when the Eu-filled skutterudite shows its highest thermoelectric figure of merit, ZT, reaching a value of ∼0.12 at 723 K (see Figure S5). This maximum is superior than that observed in the La0.5Co4Sb12 nominal composition prepared under high pressure, owing to its lower resistivity with respect to that of the La-filled compound beyond 550 K.

4 Conclusions

The synthesis and sintering of Eu0.02(1)Co4Sb12 skutterudite was carried out in one step under high-pressure conditions, followed by quenching. The structural analysis from SXRD data discloses a novel position for the rattling Eu atoms, at 12d sites within the large overdimensioned cages occurring in the skutterudite framework. The Debye temperature was obtained by averaging the isotropic displacements by the Co and Sb atomic masses, providing

Acknowledgements

All the authors thank the Spanish Ministry for Science and Innovation (MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033) for funding the project numbers: PID2021-122477OB-I00 and TED2021-129254B-C22. J.G. thanks MICINN for granting the contract PRE2018-083398. The authors wish to express their gratitude to ALBA technical staff for making the facilities available for the synchrotron X-ray diffraction experiment number 2017072260.

-

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest statement: There are no conflicts to declare.

References

1. Li, J.-F., Liu, W.-S., Zhao, L.-D., Zhou, M. High-performance nanostructured thermoelectric materials. NPG Asia Mater. 2010, 2, 152–158; https://doi.org/10.1038/asiamat.2010.138.Suche in Google Scholar

2. Snyder, G. J., Toberer, E. S. Complex thermoelectric materials. Nat. Mater. 2008, 7, 105–114; https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat2090.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Nolas, G. S., Morelli, D. T., Tritt, T. M. Skutterudites: a phonon-glass-electron crystal approach to advanced thermoelectric energy conversion applications. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 1999, 29, 89–116.10.1146/annurev.matsci.29.1.89Suche in Google Scholar

4. Zhu, T., Liu, Y., Fu, C., Heremans, J. P., Snyder, J. G., Zhao, X. Compromise and synergy in high-efficiency thermoelectric materials. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1605884; https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201605884.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Slack, G. A. CRC handbook of hermoelectrics. In CRC Handbook of Thermoelectricshermoelectrics; Rowe, D. M., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 1995; pp. 407–440.Suche in Google Scholar

6. Qiu, P. F., Yang, J., Liu, R. H., Shi, X., Huang, X. Y., Snyder, G. J., Zhang, W., Chen, L. D. High-temperature Electrical and Thermal Transport Properties of Fully Filled Skutterudites RFe4Sb12 (R5Ca, Sr, Ba, La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Eu, and Yb). J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 12, 063713; https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3553842.Suche in Google Scholar

7. Shi, X., Bai, S., Xi, L., Yang, J., Zhang, W., Chen, L., Yang, J. Realization of high thermoelectric performance in n-type partially filled skutterudites. J. Mater. Res. 2011, 26, 1745–1754.10.1557/jmr.2011.84Suche in Google Scholar

8. Nolas, G. S., Slack, G. A., Morelli, D. T., Tritt, T. M., Ehrlich, A. C. The effect of rare-earth filling on the lattice thermal conductivity of skutterudites. J. Appl. Phys. 1996, 79, 4002; https://doi.org/10.1063/1.361828.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Patschke, R., Zhang, X., Singh, D., Schindler, J., Kannewurf, C. R., Lowhorn, N., Tritt, T., Nolas, G. S., Kanatzidis, G. M. Thermoelectric properties and electronic structure of the cage compounds A2BaCu8Te10 (A = K, Rb, Cs): systems with low thermal conductivity. Chem. Mater. 2001, 13, 613–621; https://doi.org/10.1021/cm000390o.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Koza, M. M., Johnson, M. R., Viennois, R., Mutka, H., Girard, L., Ravot, D. Breakdown of phonon glass paradigm in La- and Ce-filled Fe4Sb12 skutterudites. Nat. Mater. 2008, 7, 805–810; https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat2260.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Snyder, G. J., Christensen, M., Nishibori, E., Caillat, T., Iversen, B. B. Disordered zinc in Zn4Sb3 with phonon-glass and electron-crystal thermoelectric properties. Nat. Mater. 2004, 3, 458–463; https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat1154.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Prado-Gonjal, J., Serrano-Sánchez, F., Nemes, N. M., Dura, O. J., Martínez, J. L., Fernández-Díaz, M. T., Fauth, F., Alonso, J. A. Extra-low thermal conductivity in unfilled CoSb3−δ skutterudite synthesized under high-pressure conditions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 111, 083902; https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4993283.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Serrano-Sánchez, F., Prado-Gonjal, J., Nemes, N. M., Biskup, N., Varela, M., Dura, O. J., Martínez, J. L., Fernández-Díaz, M. T., Fauth, F., Alonso, J. A. Low thermal conductivity in La-filled cobalt antimonide skutterudites with an inhomogeneous filling factor prepared under high-pressure conditions. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 118–126; https://doi.org/10.1039/C7TA08545A.Suche in Google Scholar

14. Serrano-Sánchez, F., Prado-Gonjal, J., Nemes, N. M., Biskup, N., Dura, O. J., Martínez, J. L., Fernández-Díaz, M. T., Fauth, F., Alonso, J. A. Thermal conductivity reduction by fluctuation of the filling fraction in filled cobalt antimonide skutterudite thermoelectrics. ACS Appl. Energy Mater 2018, 1, 6181–6189; https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaem.8b01227.Suche in Google Scholar

15. Gainza, J., Serrano-Sánchez, F., Prado-Gonjal, J., Biskup, N., Dura, O. J., Martínez, J. L., Fauth, F., Alonso, J. A. Substantial thermal conductivity reduction in mischmetal skutterudites Mm: XCo4Sb12 prepared under high-pressure conditions, due to uneven distribution of the rare-earth elements. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7, 4124–4131; https://doi.org/10.1039/c8tc06461j.Suche in Google Scholar

16. Gainza, J., Serrano-Sánchez, F., Rodrigues, J. E., Prado-Gonjal, J., Nemes, N. M., Biskup, N., Dura, O. J., Martínez, J. L., Fauth, F., Alonso, J. A. Unveiling the correlation between the crystalline structure of M-filled CoSb3 (M = Y, K, Sr) skutterudites and their thermoelectric transport properties. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2001651; https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202001651.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Rodrigues, J. E. F. S., Gainza, J., Serrano-Sánchez, F., Ferrer, M. M., Fabris, G. S. L., Sambrano, J. R., Nemes, N. M., Martínez, J. L., Popescu, C., Alonso, J. A. Unveiling the structural behavior under pressure of filled M0.5Co4Sb12 (M = K, Sr, La, Ce, and Yb) thermoelectric skutterudites. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 7413–7421; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.1c00682.Suche in Google Scholar

18. Gainza, J., Serrano-Sánchez, F., Nemes, N. M., Dura, O. J., Martínez, J. L., Fauth, F., Alonso, J. A. Strongly reduced lattice thermal conductivity in Sn-doped rare-earth (M) filled skutterudites MxCo4Sb12−ySny, promoted by Sb–Sn disordering and phase segregation. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 26421–26431; https://doi.org/10.1039/D1RA04270J.Suche in Google Scholar

19. Tang, Y., Gibbs, Z. M., Agapito, L. A., Li, G., Kim, H-S, Nardelli, M. B., Curtarolo, S., Snyder, G. J. Convergence of multi-valley bands as the electronic origin of high thermoelectric performance in CoSb3 skutterudites. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 1223–1228; https://doi.org/10.1038/NMAT4430.Suche in Google Scholar

20. Jeitschko, W., Foecker, A. J., Paschke, D., Dewalsky, M. V., Evers, Ch. B. H., Künnen, B., Lang, A., Kotzyba, G., Rodewald, U. Ch., Möller, M. H. Crystal structure and properties of some filled and unfilled skutterudites: GdFe4P12, SmFe4P12, NdFe4As12, Eu0.54Co4Sb12, Fe0.5Ni0.5P3, CoP3, and NiP3. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2000, 626, 1112–1120. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1521-3749(200005)626:5<1112::AID-ZAAC1112>3.0.CO;2-E.10.1002/(SICI)1521-3749(200005)626:5<1112::AID-ZAAC1112>3.0.CO;2-ESuche in Google Scholar

21. Fauth, F., Boer, R., Gil-Ortiz, F., Popescu, C., Vallcorba, O., Peral, I., Fullà, D., Benach, J., Juanhuix, J. The crystallography stations at the Alba synchrotron. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2015, 130, 160; https://doi.org/10.1140/epjp/i2015-15160-y.Suche in Google Scholar

22. Rodríguez-Carvajal, J. Recent advances in magnetic structure determination by neutron powder diffraction. Phys. B 1993, 192, 55–69; https://doi.org/10.1016/0921-4526(93)90108-I.Suche in Google Scholar

23. Rietveld, H. M. A profile refinement method for nuclear and magnetic structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1969, 2, 65–71; https://doi.org/10.1107/S0021889869006558.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Rodrigues, J. E. F. S., Escanhoela, C. A.Jr., Fragoso, B., Sombrio, G., Ferrer, F. F., Álvarez-Galván, C., Fernández-Díaz, M. T., Souza, J. A., Ferreira, F. F., Pecharromán, C., Alonso, J. A. Experimental and theoretical investigations on the structural, electronic, and vibrational properties of Cs2AgSbCl6 double perovskite. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 18918–18928.10.1021/acs.iecr.1c02188Suche in Google Scholar

25. Rodrigues, J. E. F. S., Gainza, J., Serrano-Sanchez, F., Marini, C., Huttel, Y., Nemes, N. M., Martínez, J. L., Alonso, J. A. Atomic structure and lattice dynamics of CoSb3 skutterudite-based thermoelectrics. Chem. Mater. 2022, 34, 1213–1224.10.1021/acs.chemmater.1c03747Suche in Google Scholar

26. Oftedal, I. XXXIII. Die Kristallstruktur von Skutterudit und Speiskobalt-Chloanthit. Z. Kristallogr. 1928, 66, 517–546; https://doi.org/10.1524/zkri.1928.66.1.517.Suche in Google Scholar

27. Chakoumakos, B. C., Sales, B. C. Skutterudites: their structural response to filling. J. Alloys Compd. 2006, 407, 87–93; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2005.06.073.Suche in Google Scholar

28. Hanus, R., Guo, X., Tang, Y., Li, G., Snyder, G. J., Zeier, W. G. A chemical understanding of the band convergence in thermoelectric CoSb3 skutterudites: influence of electron population, local thermal expansion, and bonding interactions. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 1156–1164; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b04506.Suche in Google Scholar

29. Yelgel, Ö. C., Ballikaya, S. Theoretical and experimental evaluation of thermoelectric performance of alkaline earth filled skutterudite compounds. J. Solid State Chem. 2020, 284, 121201.10.1016/j.jssc.2020.121201Suche in Google Scholar

30. Tang, Y., Hanus, R., Chen, S., Snyder, G. J. Solubility design leading to high figure of merit in low-cost Ce-CoSb3 skutterudites. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7584; https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8584.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Mi, J., Christensen, M., Nishibori, E., Iversen, B. B. Multitemperature crystal structures and physical properties of the partially filled thermoelectric skutterudites M0.1Co4Sb12 (M = La, Ce, Nd, Sm, Yb, and Eu). Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84, 064114; https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.84.064114.Suche in Google Scholar

32. Tang, Y., Chen, S. W., Snyder, G. J. Temperature dependent solubility of Yb in Yb–CoSb3 skutterudite and its effect on preparation, optimization and lifetime of thermoelectrics. J. Mater. 2015, 1, 75–84; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmat.2015.03.008.Suche in Google Scholar

33. Lamberton, G. A., Bhattacharya, S., Littleton, R. T., Kaeser, M. A., Tedstrom, R. H., Tritt, T. M., Yang, J., Nolas, G. S. High figure of merit in Eu-filled CoSb3-based skutterudites. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2002, 80, 598–600; https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1433911.Suche in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article offers supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/zkri-2022-0051).

© 2022 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Inorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- A contribution to the perrhenate crystal chemistry: the crystal structures of new CdTh[MoO4]3-type compounds

- Mixed-valent 1:1 oxidotellurates(IV/VI) of Na, K and Rb: superstructure and three-dimensional disorder

- Structure and properties of phases from solid solutions YTIn1−x Al x (T = Ni and Cu)

- Halide-sodalites: thermal behavior at low temperatures and local deviations from the average structure

- Structural study of ceramic samples of the PbTiO3–BaTiO3–BaZrO3 system with a high PbTiO3 content studied by the Rietveld method

- A novel crystallographic location of rattling atoms in filled Eu x Co4Sb12 skutterudites prepared under high-pressure conditions

- Magnesium and barium in two substructures: BaTMg2 (T = Pd, Ag, Pt, Au) and the isotypic cadmium compound BaAuCd2 with MgCuAl2 type structure

- Organic and Metalorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Synthesis, structure, and photocatalytic properties of a two-dimensional uranyl organic framework

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Inorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- A contribution to the perrhenate crystal chemistry: the crystal structures of new CdTh[MoO4]3-type compounds

- Mixed-valent 1:1 oxidotellurates(IV/VI) of Na, K and Rb: superstructure and three-dimensional disorder

- Structure and properties of phases from solid solutions YTIn1−x Al x (T = Ni and Cu)

- Halide-sodalites: thermal behavior at low temperatures and local deviations from the average structure

- Structural study of ceramic samples of the PbTiO3–BaTiO3–BaZrO3 system with a high PbTiO3 content studied by the Rietveld method

- A novel crystallographic location of rattling atoms in filled Eu x Co4Sb12 skutterudites prepared under high-pressure conditions

- Magnesium and barium in two substructures: BaTMg2 (T = Pd, Ag, Pt, Au) and the isotypic cadmium compound BaAuCd2 with MgCuAl2 type structure

- Organic and Metalorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Synthesis, structure, and photocatalytic properties of a two-dimensional uranyl organic framework