Abstract

The study of plaster vessels, white ware, from the Late Neolithic Southwest Asia (7000–5000 cal BC) is an untapped source that can provide us with valuable insights into the earliest development of pyrotechnology and Neolithic society. This plaster material is not well known and has not been involved in many studies. Using a symmetrical approach for the case study of plaster ware at Tell Sabi Abyad in Upper Mesopotamia, this article argues that it is crucial to acknowledge materiality in the study of these vessels. The ware resembles pottery in shape, typology, and basic function but is far from it material-wise and in its chaîne opératoire. The material plaster is also often misunderstood and associated primarily with architecture. Therefore, plaster ware stands at the crossroads between being observed as a copy of ceramics and being recognized as portable architecture. This article calls for an interdisciplinary approach, balancing the exact sciences of archaeometry and the theory of materiality. It will also address problems concerning terminology; it proposes replacing the term white ware with “plaster ware” as the most appropriate title for this ware because it can be better understood by a wider audience outside the discipline.

1 Introduction

Within Southwest Asian archaeology, plaster ware (Figure 1), commonly known as white ware, occurred incidentally as early as the eight-millennium cal BC and continued to exist until c. 4500 cal BC. On a larger scale, it was only manufactured for a certain limited period during the Early Pottery Neolithic (EPN) period, 6700–6200 cal BC. At the same time, it was during a crucial development period for the Neolithic society marked by cultural and climatic change (associated with the so-called 8.2 ka event). This plaster material is unknown outside the field and has not been involved in many studies. The material has been found in a limited number of excavations in Syria, Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon, Israel, and Iraq (see overview sites in Nilhamn, 2003). In recent years, material from Sha’ar Hagolan in Israel (Freikman, 2019) and Shir (Rokitta-Krumnow & Wittmann-Gering, 2019), Tell Halula (Molist et al., 2021), and Tell Sabi Abyad in Syria (Nilhamn & Koek, 2013) has been studied thoroughly. As the number of excavations is limited, and the plaster material has not always been fully acknowledged during excavations, many questions remain unanswered. Since it was not clay ceramics, the pottery specialists did not consider it significant enough to incorporate into their studies, so it was often put into the small finds category of “varia” or “miscellaneous objects.”

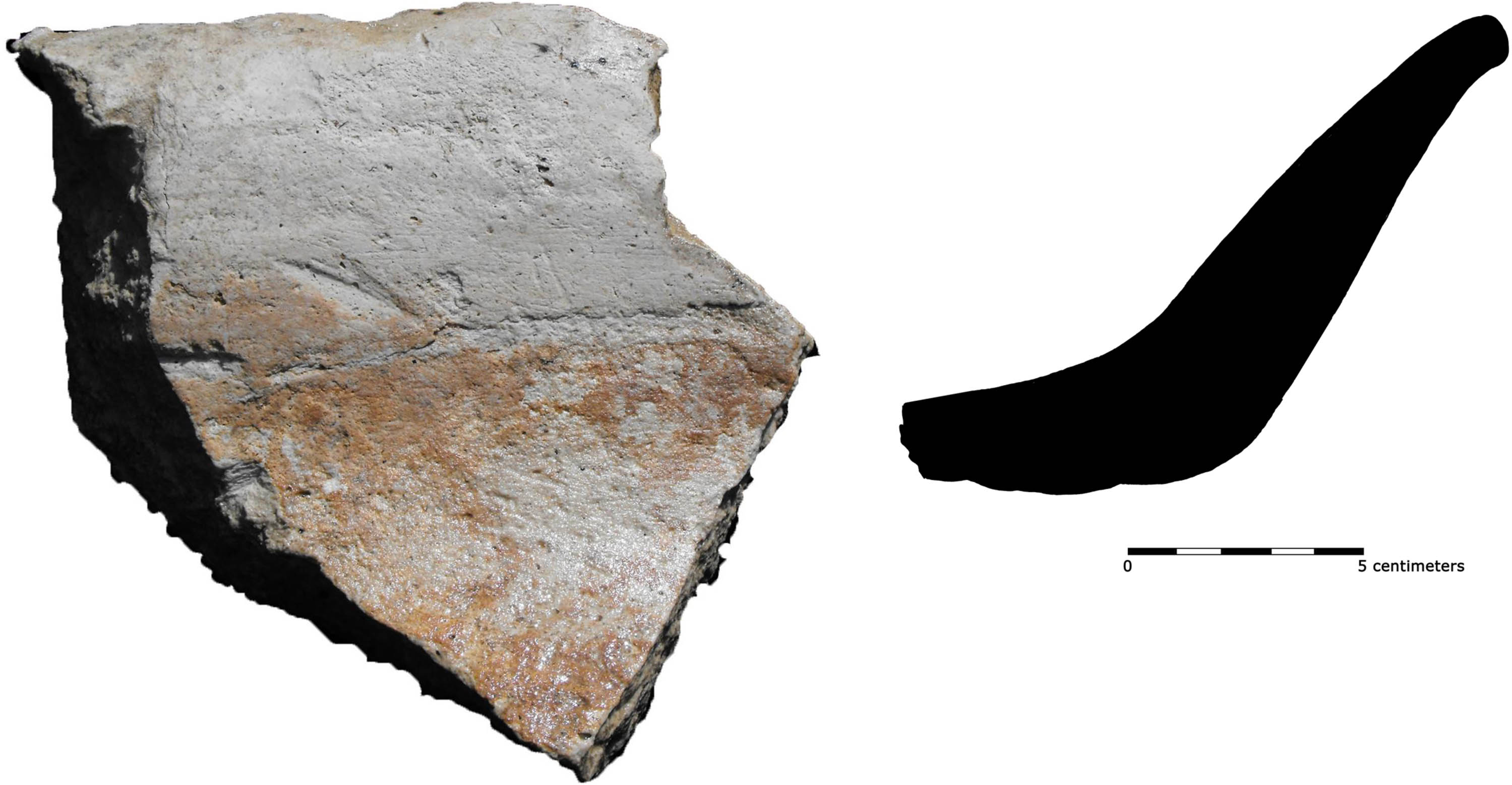

V08-67, Rimsherd of open gypsum plaster ware bowl. Tell Sabi Abyad, Syria (level A2/A3) 6395–6330 cal BC (photo: author, Drawing: M. Hense).

For a long time, white ware, or “vaiselle blanche,” was seen as the predecessor of pottery (Akkermans & Schwartz, 2003; Barnett & Hoopes, 1995; Balfet, Lafuma, Lounget, & Terrier, 1969; Contenson & Courtois, 1979). However, recent results show that plaster ware was contemporary with pottery but had different functions due to the physical properties of the raw materials (Nieuwenhuyse & Nilhamn, 2011). The variety of shapes for the plaster ware was also limited compared to the more versatile clay. These limitations are related to the plaster-shaping techniques and the chaîne opératoire. The ability of clay to take a wider variety of culturally bound styles has been put forward as one plausible reason why pottery continued to flourish while plaster ware ceased to exist (Nieuwenhuyse & Nilhamn, 2011). Plaster was (and still is) a common material but for other purposes. It is found in architectural features from the Neolithic period until modern times and has also been used as a medium for creating art objects. Nowadays, this material is not widely used for portable vessels, which might affect our view of it. From our own cultural perspective, it is too easy to regard plaster vessels as copies of pottery or a by-product when making an architectural feature.

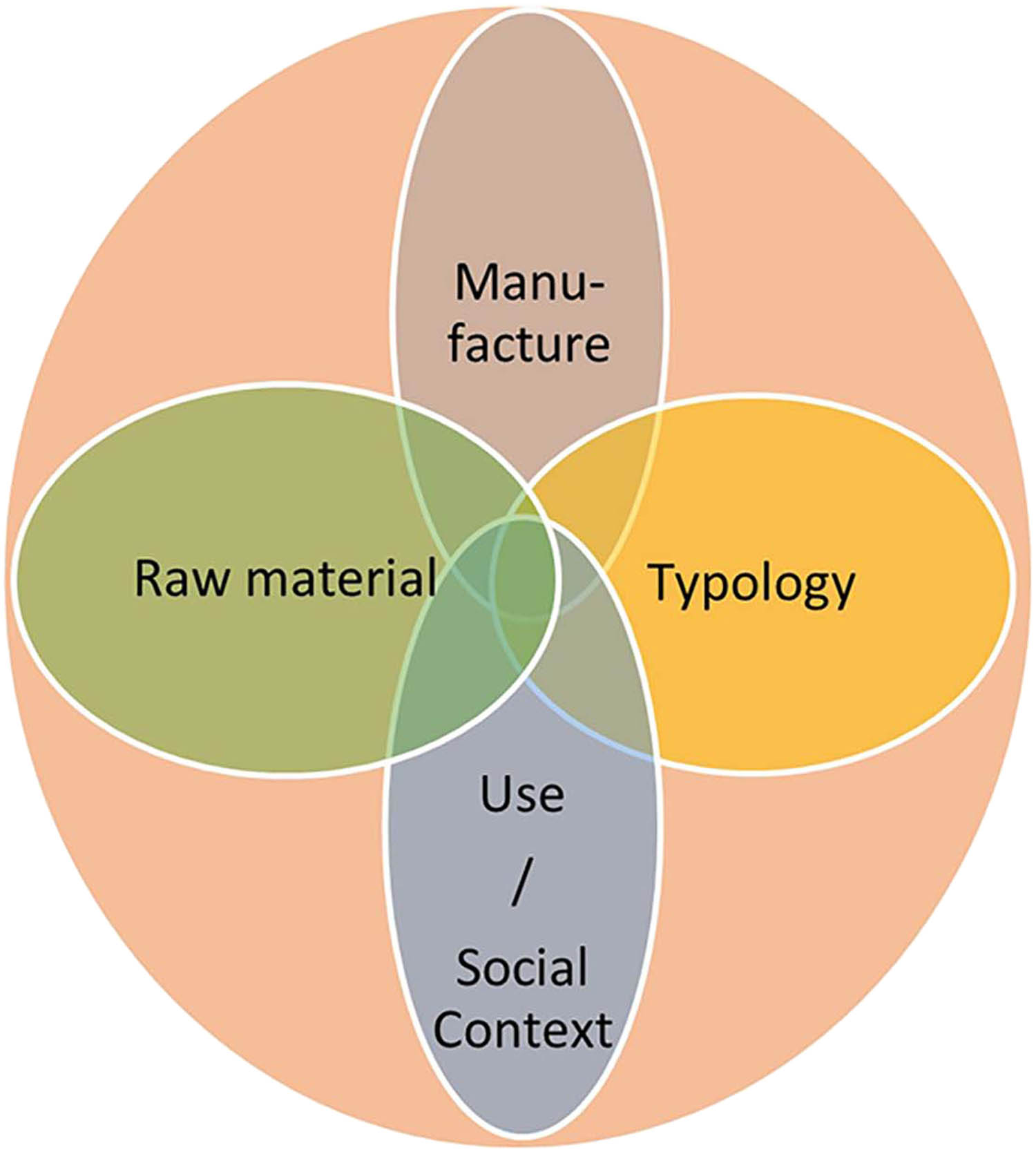

Plaster containers are genuinely in the middle of the crossroad of disciplines based on our traditional conceptions:

Plaster, as a building material and mortar, is mainly studied with a focus on physicochemical properties using analytical techniques like X-ray fluorescence (XRF), X-ray diffraction (XRD), thermogravimetry with differential thermal analysis, scanning electron microscopy-energy-dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) and infrared (IR) methods (archaeometry/geo-archaeology).

Containers as objects often involve traditional research questions of function and symbolic elements and their impact on society. The typology of the container has traditionally been the main focus (material agency/theoretical archaeology).

It will be argued here that plaster ware studies need to be approached from both sides, the technical aspects of the plaster and the more traditional study of the container. The study of plaster, therefore, starts with acknowledging how to study materials.

This article embraces theoretical discussion and natural science and takes its stand in the symmetrical approach or symmetrical archaeology (SA). This multidisciplinary approach has proved to be valuable for studying the plaster ware of Tell Sabi Abyad, Syria. SA emphasizes several aspects: the importance of acknowledging the physical material, the relevance of other find categories, the physical environment, how people used it, how we as archaeologists see and treat it, and how we communicate to our peers and the public about it.

2 Definition

White ware (vaiselle blanche) is the collective name used for Neolithic portable plaster containers found in Southwest Asia; it was coined by the French archaeologist Maurice Dunand in 1949 (1949, p. 57). Because its typology resembles Neolithic ceramics, it has often been described using pottery terminology. Traditionally, the study of ceramics has had a privileged position within archaeology. Most archaeology students count and draw sherds at some stage in their study. Moreover, there are countless articles on the matter within archaeology, anthropology, and ethnology, covering the emergence of pottery, its typology, its functionality, the socio-economic context, domestic use, high status, and pottery as a ritual object. In addition, raw material aspects and the chaîne opératoire have been studied using archaeometrical approaches and experimental archaeology. This bias is not unjustified because pottery is a common feature of human cultural development that is found worldwide. Clay is a reasonably stable material, so sherds manage to tell us about human behaviour through time (Kolb, 2000; Skibo & Feinman, 1999); hence, they are often used for relative dating. When thinking about the earliest containers, the evolution of pottery comes to mind. The Neolithic era has even been called the age of clay (Stevanović, 1997). Still today, we tend to divide cultures (Linear Pottery, Funnelbeaker, and Comb-ceramic culture, to name some of the more known ones in Europe) and time periods according to pottery (Pre-Pottery, Initial Pottery, and EPN).

Because we are so familiar with the study of pottery, it is, perhaps, too easy to immediately compare all kinds of vessels with those made of ceramics. As a result, terms like “container,” “vessel,” and “pot” are typically associated with ceramic goods, rendering other materials such as stone, wood, woven materials, and plaster secondary. So, from a “Saussurian” (De Saussure, 1970) point of view, it is a risk of only speaking the language of “ceramic” that all things are seen in relationship to it. Even in this article, the discussion will seem to fall into this trap as we relate plaster to pottery; however, here it is with a plaster-centric view, and pottery is only one of many relationships around it.

2.1 Terminology

Getting caught up in terminology when working on a particular topic is easy. The term, common within Near Eastern Archaeology, white ware is problematic for the broader audience outside the field, who would envision white glazed earth wares or tiles instead of EPN containers made of plaster. Internet and database search results are often misleading.

The same is true when talking about plaster. According to the common definition by Britannica.com, plaster is “a pasty composition (as of lime or gypsum, water, and sand) that hardens on drying and is used for coating walls, ceilings, and partitions (Britannica, 2019).” According to the International Organization of Standardization (ISO) 6707-1:2020 definition, plaster is a mixture of one or more binders, while a mixture of one or more binders with aggregate is seen as renders. The technical definition (ISO 6707-1, 2020) is more complex in detail: “Mixture used to obtain an internal finish (3.3.5.2), based on one or more binders (3.4.4.14) which, after the addition of water, is applied while plastic and hardens after application.” In archaeometry, plaster is more inclusive and can include both plaster and renders. This is acknowledged within building history as problematic when discussing ancient materials (Gliozzo, Pizzo, & La Russa, 2021).

In archaeological discourse, the term plaster is also used in a broad sense. To illustrate: a field report statement, “The floor was made of plaster,” can also refer to a “mud”-plaster floor. The term gypsum is likewise confusing. It can refer to both the rock gypsum and the paste gypsum plaster, two distinct materials. This becomes even more unclear when gypsum starts to mean plaster, regardless of the main raw material. Often in site-based descriptive reports, especially from earlier excavations, the plaster ware was never investigated on its own and was mentioned as a secondary category (Contenson & Courtois, 1979; Riis & Paulsen, 1957; Riis, 1962; Riis & Thrane, 1974) or as varia, as at the excavation of Tell Sabi Abyad. Unfortunately, it is often only recognized as plaster since its composition cannot be directly visually determined in the field. Even though lime plaster usually has an off-white colour, while gypsum has a more pinkish, buff, and grey hue, and lime plaster generally reacts if submitted to an acid test (i.e. placing a drop of dilute 5–10% hydrochloric acid on a rock or plaster sherd and watching for bubbles of carbon dioxide gas to be released: carbonate minerals will make the material effervesce, i.e. fizz and bubble – gypsum does not), contamination from the surrounding soil can mislead. As a result, laboratory analyses, such as XRF spectrometry and XRD analyses, are needed. This difficulty in identifying plaster made of gypsum rock vs limestone plaster is problematic since the two materials are distinct in their properties and functions.

As limestone plaster is the most common plaster in architecture, it has become a misconception that plaster/white ware is a limestone product. This assumption was based on the initial analysis of plaster ware given by Balfet et al. (1969) on material from Tell Ramad. This material was indeed lime plaster (Kingery, Vandiver, & Prickett, 1988). However, research results from the Chagha Sefid in Iran and the Balikh and Khabour valleys in Syria have shown that gypsum was also commonly used or even preferred (Kingery et al., 1988; Nilhamn & Koek, 2013; Rehhoff, Akkermans, Leonardsen, & Thuesen, 1990). Remarkably, limestone plaster was found principally in the earliest levels of Tell Sabi Abyad, challenging the theory (Frierman, 1971; Gourdin & Kingery, 1975; Rehhoff et al., 1990) that lime plaster technology was a later phenomenon and gypsum plaster an inferior technology.

3 Materials and Methods

3.1 Tell Sabi Abyad

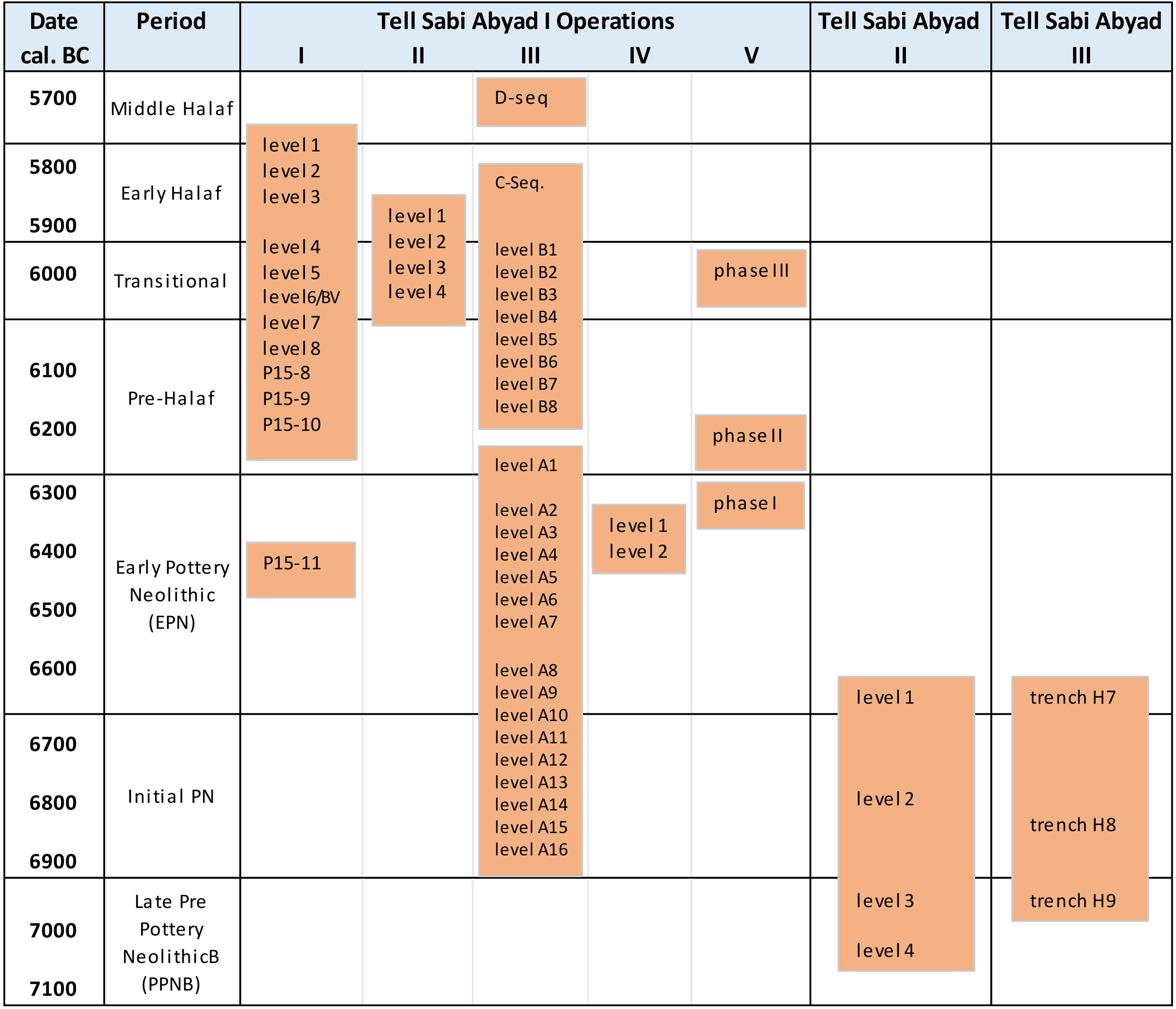

Tell Sabi Abyad was a small, nucleated village in the valley of the river Balikh, a perennial tributary of the Euphrates in the semi-arid northern Syrian steppes (Figure 2). The site has a total of four prehistoric mounds: Tell Sabi Abyad (SAB) I–IV, measuring between 1 and 5 ha in size. The mounds were inhabited from the later Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) (ca. 7550 cal BC) to the middle Halaf period (5700 cal BC; Figure 3). Occupation shifted back and forth from one mound to another. After c. 6700 BC, the beginning of the EPN, the settlement concentrated on the main mound SAB I. The economy was based on a semi-pastoral lifestyle (Akkermans, 2013). Several cultural transformations, including the development and use of clay and plaster containers, were introduced in the eighth and seventh millennia cal BC. Plaster ware and pottery emerged at the site around 7000 cal BC, opening up a vast new range of possibilities for handling fluids and goods. Both materials became exceptionally abundant during the EPN phase ca. 6700–6300 cal BC (levels A10 to A2 in SAB I Operation III). This EPN phase can be compared with the final PPNB/PPNC in the southern Levant (Nieuwenhuyse, Akkermans, & van der Plicht, 2010; Nilhamn, Astruc, & Gaulon, 2009; Nilhamn & Koek, 2013). Besides plaster ware and pottery, containers made of wood and leather, or liquid pouches like waterskins made of bladders, also existed but have not been preserved other than as vague charred wood fragments and bitumen imprints (Figure 4). Bitumen with basketry impressions found at the mounds SAB II and III show that bitumen-coated baskets were used in the PPNB (7550–6850 cal BC) and the Initial Pottery Neolithic (IPN; 7000–6700 cal BC) (Berghuijs, 2013). Stone vessels were also found (Table 1).

Upper Mesopotamia refers to the plains and steppes stretching from the coastal mountains of the northern Levant through south-eastern Anatolia and northern Syria into northern Iraq. The geographic location of Tell Sabi Abyad is marked in red (image: M. Hense).

The complex occupational sequence of Tell Sabi Abyad: Plaster ware occurs incidentally in PPNB. It becomes frequent from level A16 onwards with a concentration towards levels A6-A1. In levels C and D, it occurs but only in limited numbers (after image: A. Kaneda; Tell Sabi Abyad Project and Van der Plicht, Akkermans, Nieuwenhuyse, Kaneda, & Russell, 2011).

Bitumen-coated “leather bag” found in mound SAB III, trench J9. The sewing stitch is visible in the corner (© Peter Akkermans, Tell Sabi Abyad Archive).

Portable containers found at Tell Sabi Abyad, per project (MF denotes MasterFile number and is a saved individual object)

| Plaster ware | Pottery | Basketry | Stone vessels | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw count | Weight (kg) | MF | Profile | Complete | Raw count | MF | Profile | Complete | MF | MF | |

| SAB I Op: I | 249 | n/a | 181 | 3 | 0 | 49,974 | 185 | 115 | 15 | 139 | 159 |

| SAB I Op: II | 750 | n/a | 44 | 0 | 0 | 1,812 | 37 | 37 | 0 | 18 | 13 |

| SAB I Op: III | 21,040 | 1172.74 | 1,433 | 115 | 3 | 69,820 | 172 | 243 | 66 | 155 | 848 |

| SAB I Op: IV | 1,140 | 2.79 | 171 | 2 | 0 | 10,278 | 8 | 28 | 5 | 1 | 24 |

| SAB I Op: V | 414 | n/a | 107 | 2 | 0 | 4,737 | 8 | 19 | 2 | 3 | 12 |

| SAB II | 17 | n/a | 16 | 1 | 0 | 137 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 46 |

| SAB III | 155 | n/a | 17 | 1 | 0 | >187 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 152 | 56 |

| Total | 23,765 | >1,176 | 1,969 | 124 | 3 | >143,424 | 411 | 443 | 88 | 474 | 1,158 |

Basketry indicates imprints of basketry found on plaster, pottery, clay, or bitumen. Bold highlighted: SAB I Operation III, the focus of the research.

SAB mound I has been extensively excavated since 1986 by Prof. Dr Akkermans Leiden University, the Netherlands. The excavations were divided into five operations (I–V). Between 1986 and 1999, Operation I focussed on the southeastern part of the site, where occupation levels of Pre-Halaf, Transitional, and Halaf, ca. 6200–5850 BC, were exposed (Akkermans, 1993; Akkermans, Brüning, Huigens, & Nieuwenhuyse, 2014). Excavation in Operation II took place in 2003 and 2004 in the northeastern area, with Transitional and Halaf levels dated to ca. 6100–5800/5700 BC (Akkermans et al., 2012). The northwest slope was excavated as Operation III between 2002 and 2009, and exposed layers were radiocarbon dated to between 7000 and 6200 cal BC. Operations IV and V were excavated in 2001 and 2002 on the western side of mound I. Operation IV dates tentatively to EPN 6395–6375 cal BC. Operation V layers have been attributed to EPN and Transitional (ca. 6300–6200 BC and ca 5950–5900 BC, respectively; Akkermans et al., 2006; Nieuwenhuyse, 2018).

Mound SAB II was excavated between 1993 and 2001 (Verhoeven & Akkermans, 2000; Verhoeven, 2004). The lowest levels belong to the PPNB, while the upper levels have been dated to the IPN (7050–6700 BC; Akkermans, 2013). Mound SAB III was investigated in 2005 and 2010. It has been dated to the IPN, ca. 7000–6700 BC (Akkermans & Brüning, 2019; Nieuwenhuyse et al., 2010).

3.2 Data Set

Lemonnier (1992) exclaims that one must study the entire material assemblage to be able to understand any society. In this respect, the well-documented Tell Sabi Abyad excavation is a goldmine of information (Akkermans, 2014). The well-defined and dated stratigraphy, especially of SAB I Operation III, the total find assembly, and the relationships between find categories contribute to the understanding of how the plaster ware, as both a physical commodity and a pyrotechnological conception, emerged, was modified, used, and ceased at a certain point.

Between 2002 and 2009, all plaster ware found at the Tell Sabi Abyad excavation was collected, counted, weighed, and examined. SAB I Operation III alone generated a total of 21,040 plaster sherds (raw counts), which equals more than a ton (1172.7 kg; Table 1). During the field campaigns before 2002, sherds were only counted, not weighed. Counting sherds often show a different picture of the situation than weighing. It was observed that plaster sherds found in an indoor context were generally fewer in number but less fragmented. By including weight and calculating the % of the completeness of the material, a better understanding of quantification is gained. More than half (57 or 59%, depending on the choice of count or weight) of the material came from open areas, while only 13 or 16% came from room fill. Similarly, the volume of the vessels has also been estimated (Nilhamn et al., 2009). By using the method of estimated vessels represented (EVR, i.e. estimating the minimum number of vessels represented based on diagnostic fragments – rims and/or base sherds. Fragments attributed to the same vessel were seen as one item), 1,433 individual items from SAB I Operation III were registered and given an own M(aster)F(ile)-number. Plaster fragments assumed to be related to architectural features (floors, walls, platforms, and larger bins) were only incidentally collected as samples. Therefore, semi-stationary objects (Figure 5), like smaller bins or larger portable vessels, may never have reached the find registration.

Semi-permanent architectural bin in situ Tell Sabi Abyad, square F04 locus 207 (level A4) 6455–6390 cal BC. Diameter 45–50 cm. Height 38 cm (photo: author).

The study of the morphology of the plaster ware was made by macroscopic categorization to establish a codebook. This was done partly based on the terminology used at the site of Tell Sabi Abyad by the ceramicists (Nieuwenhuyse, 2007) and partly based on typical features of the plaster material. There was no earlier typology made for plaster ware, neither on the site itself nor from comparative sites in the region; it was not found in the literature as well. The reason for this was quite simple. Other sites had not yielded the same amount of plaster ware as Tell Sabi Abyad [cf. Sha’ar Hagolan 63 sherds (Freikman, 2019), Shir 330 sherds (Rokitta-Krumnow & Wittmann-Gering, 2019), Tell Halula ca. 400 with a detailed study of 154 sherds (Molist et al., 2021)].

Archaeometric analyses (XRF, XRD, optical microscopy, SEM-EDS) confirmed three main types of true Neolithic plaster found at Tell Sabi Abyad: Plaster made from limestone, gypsum, or a mixture of the two (Nilhamn & Koek, 2013). The author did not consider ware made with the addition of clay or marly clay (the latter often very light coloured) as proper plaster and it was, therefore, classified as pottery. Additional research included organic residue analysis (ORA)/gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS; Nilhamn, 2023), geological surveys and geographic information system (GIS) (Nilhamn, in Press), experimental archaeology of pigment (Nilhamn, 2017), and plaster and container production (ongoing experiments).

3.3 Symmetrical Approach

Materiality, as a concept, was introduced by Gosden (1994) to explain socio-material relations as something distinct from social relations or “mutuality.” It has a firm role within the study of materials and (agency of) things and the tradition of the actor-network theory (ANT). SA describes a material’s physical properties and studies how these features and their performances influence the user and society. In short, the choice of material affects the product (i.e. the object and its social interaction). The symmetry results from balancing the use of scientific data and interpretation with the acknowledgement of the role of the object (Jones, 2004). It is a symmetry between humans and objects (Shanks, 2007; Webmoor, 2007; Witmore, 2007). SA is not a new ism within archaeology, and it does not replace the earlier processual (Binford, 1962) and post-processual approaches (Hodder, 2001; Meskell & Preucel, 2004; Tilley, 1993). Instead, it builds further on the philosophical ideas of pragmatists, Leibnizians, and Whiteheadians (Witmore, 2007). Much of the vocabulary comes from the ANT proposed by the anthropologist Latour (1999, 2005), who speaks of the “infiltration” where humans no longer are the principal focus but one of several parts of a whole concept built by several “heterogeneous phenomena.” ANT emphasizes that one should not a priori have a bias of agency of subject or object (thing; Van Oyen, 2018/2021). SA acknowledges behavioural archaeology’s idea that behaviour is a result of both humans and material (LaMotta & Schiffer, 2001) and puts the spotlight on the material matter or thing (Mickel, 2016). It wants us to be aware of the capabilities and properties of materials and how things “exist, act and inflict on each other outside the human realm” (Olsen, 2012, p. 213).

The SA goes further than the holistic approach. Although the holistic approach has been proposed within archaeology as an inclusive approach that embraces social and economic organization, ideology, religion, art, and ecology (Renfrew & Bahn, 2005), it often lacks the connection between the material culture and the researcher. SA takes a stand in the balance, i.e. the dualistic symmetry of past/present, agent/thing, researcher/the studied, and theory/science. There is no long gone past; the past is still here as part of the product of evolution and development. Today, we are part of the past and “without things no humanity.” Quoting Witmore (2007), “a symmetrical archaeology builds upon the strengths of what we do as archaeologists” and requires us to be aware of the result of our actions (cf. example below of cleaning sherds).” Scholars such as Jones (2004), Olsen (2007), Shanks (2007), Webmoor (2007), and Witmore (2007, 2015, 2018, 2019) argue that archaeology is fundamentally “the discipline of things” (rather than material culture). New materialists argue that things or matter have the same capacity to cause change as humans. Things are matter because they matter due to their role and what they cause (Bennett, 2010; Coole & Frost, 2010; Dolphijn & van der Tuin, 2012; Schouwenburg, 2015). The relationship between human and nonhuman objects has been widely discussed in addition to how we, as people and researchers today, engage with the material (Knappett, 2005; Olsen, Shanks, Webmoor, & Witmore, 2012; Webmoor, 2007). Kirchhoff (2009) even states that material only has agency if both the ontological (agency is asymmetrical and relational) and epistemological (material interacts and changes human understanding) conditions are met. Hodder refers to it as the human-thing entanglement theory, where the components exist due to each other and are linked or “entangled” with each other without assuming that one is more dominant than the other. These linkages and networks evolve over time, sometimes into an inapprehensible knot (Hodder, 2011, 2015, 2018, 2020). Humans are dependent on things (a thing, according to Hodder, is a manmade object) to have a comfortable life, and their behaviour depends on whether they have access to things. Things exist due to humans, as humans make and maintain them as long as they are valuable. They also spread and evolve depending on humans’ (social) behaviour (Hodder, 2011). Renfrew also refers to it as material engagement (Renfrew, 2004). Jones emphasises that

The point is not that materials are either made with functional or social uses in mind but, rather, that the mechanical properties of artefacts either enable or constrain their use in certain social practices. It is the interaction between the properties of materials and the way in which they are socialised that is critical here (Jones, 2004, p. 335).

Unfortunately, the theory does not always connect to the real world and the field. As has previously been noted (Hodder, 2011; Jones, 2004; Nilhamn, 2003), there is a gap between archaeological scientists (archaeometry), archaeological theorists, and historians. This gap manifests in how they communicate their findings, with each group preaching to the choir. As a result, there is, for example, a certain differentiation of topics between the journals Archaeometry, which is more aimed at natural science, and the Journal of Material Culture, which explores the relationship between artefacts and social relations (Hodder, 2011; Jones, 2004).

Many material studies are either done by an archaeological scientist who relies on measurable scientific facts or an archaeological theorist who argues based on human behaviour. Both mindsets are relevant when studying material culture and a find category like plaster ware. Therefore, one must relate the object and its physical, archaeometric data to its function and place in society. It does not imply that one needs to be a specialist in all fields; it means acknowledging the available information and cooperating with scientists who can help interpret the analytical data. It calls to learn to communicate in a mutual language that social theorists and natural scientists understand and to publish one’s results for audiences beyond just peers. The author agrees entirely with Robb (2015) that the “Deep Theory” of the archaeological theorists and the “Applicable theory” of the scientists do not always reach each other. The middle range theory within material culture studies is missing (Robb, 2015). In fact, it becomes a “Deep secret” or “non-applicable theory” for the other party. The use of unambiguous terminology is helpful in the process of breaking down this divide and making unfamiliar concepts easier to grasp. Hence, this article uses the term “plaster ware” instead of “white ware.”

Studying material culture is like stereographic photography. One lens is the study of material properties, and the other is the study of the social and cultural context. By wearing the “3D glasses” of SA, it is possible to see how these properties interrelate. It is easier to understand why certain technological choices were made. It may feel odd to look through at first (as with normal 3D glasses), but it will provide depth into the material and reveal unseen aspects and details. This new interpretation is the essence of understanding material culture.

Further, it is important to recognize the one who wears the glasses. The behaviour of archaeologists and their conduct is crucial. Consider the value of cleaning sherds. We know that different materials need different cleaning and handling. However, it is easy to overthink it. At the Tell Sabi Abyad, it was acknowledged that plaster ware could not be cleaned as pottery. The common (unverified) idea was that the sherds could not be cleaned with water as they would “dissolve.” So instead, the field students cleaned them by brushing them. After some experiments (letting plaster sherds soak for days), it was noticed that it did not dissolve. In fact, brushing dry material removes important information as the surface is too soft for the brush and the enthusiastic field student. When a new cleaning routine was introduced using water without any friction applied to the objects, it was discovered that the white [plaster] ware was not always that white. XRF analyses have confirmed the presence of iron pigments. Incidentally, the pigment shows lines and dots on the exterior (Nilhamn, 2017). In other cases, the hue is most likely unintentionally caused by the contents (Figure 6).

White ware rim sherd V08-79 Tell Sabi Abyad Project Syria (level A1) 6335–6225 cal BC, after being dipped in water. While still moist, a reddish hue is visible on the vessel’s interior (photo: author, Drawing: M. Hense).

4 Chaîne Opératoire

A ware is a group of items that share the same function, appearance, style, and fabric. The materials (the fabric) and the chaîne opératoire provide the basic framework for categorizing the ware. In short, the group of items contains the same raw materials that are prepared similarly following the same step-by-step production, i.e. chaîne opératoire (Van der Leeuw, 1993). Chaîne opératoire was initially proposed by Leroi-Gourhan (1964), an anthropologist and a prehistorian who used an ethnographic approach to materials from a prehistoric settlement. Ceramicists developed the idea further, focusing on the progression of distinct processes or phases during the making of an item and how each step leads to the next before the final product is produced. Instead of being a priori based, it is founded on a posteriori information accumulation. Since the same object can be produced utilizing various methods and techniques before being finished, it can also serve as a cultural carrier. Traditions, resources, and technological expertise all influence how the path is selected (Bernbeck, 1994; Godon, 2010; Le Mière, 1979, 1986; Lemonnier, 1993; Le Mière & Nieuwenhuyse, 1996; Nieuwenhuyse, 2007, 2022).

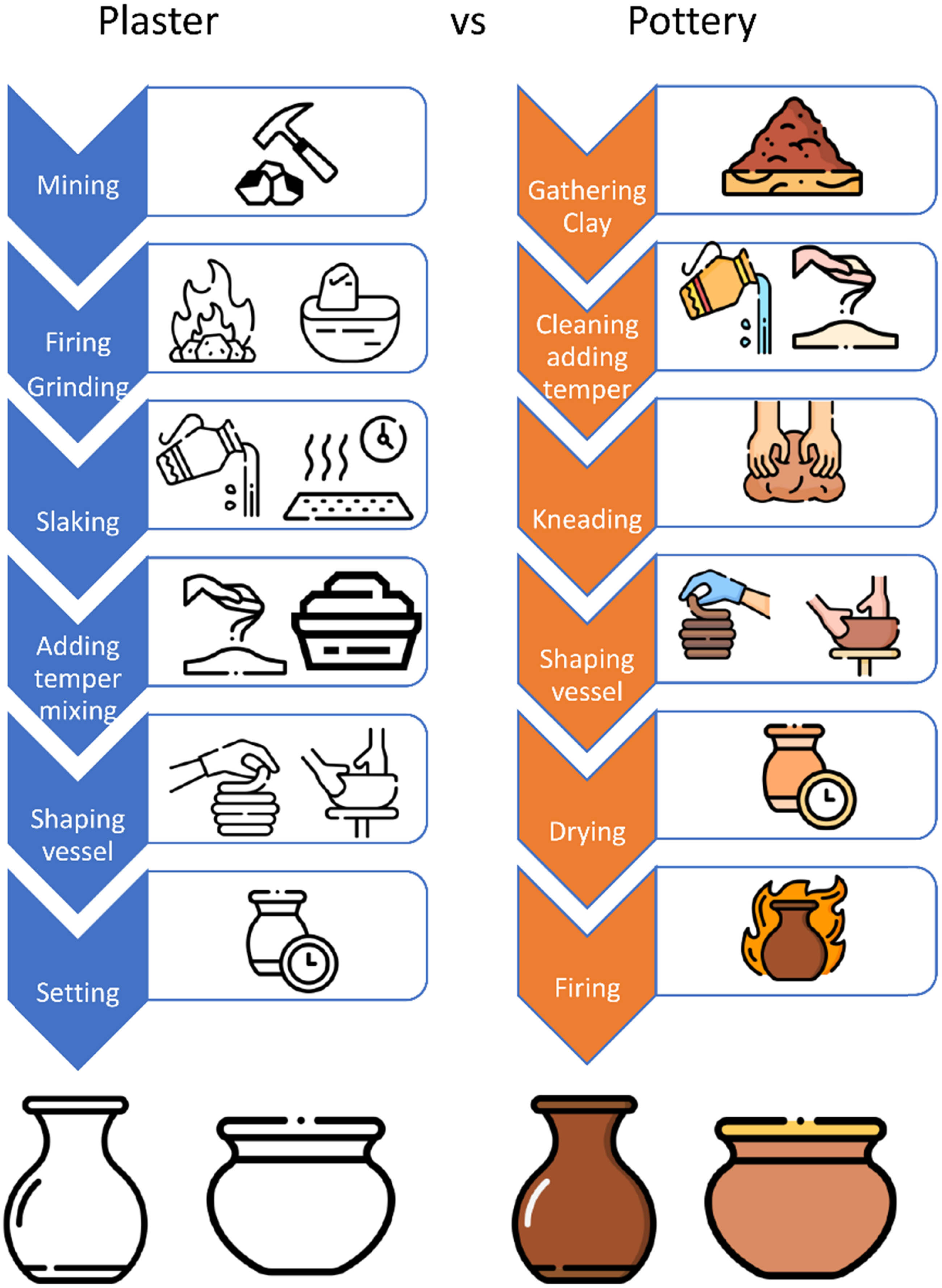

Even though Neolithic pottery and plaster ware seem related in style and shape, plaster does not share the same chaîne opératoire as pottery. The most notable difference between the two processes is that the raw material for plaster is fired at the start of the process, while in the case of pottery, the raw material is fired towards the end (Figure 7). Importantly, plaster from limestone also has a different production process than plaster from gypsum. This is crucial to emphasize.

Chaîne opératoire (simplified) for plaster and pottery (image: author using icons created by Darius Dan, Eucalyp, Freepik, Smashicons, and Umeicon from Flaticon.com).

Limestone rock (calcinated calcium carbonate, CaCO3) requires plenty of fuel to thermal decompose or calcinate (at temperatures above 825°C) into calcium oxide (CaO), also called quicklime, while gypsum rock (hydrated calcium sulphate, CaSO4·2H2O) decomposes at much lower temperatures (120–180°C). Further, the quicklime product obtained is highly caustic and not easy to handle without risk of burns, while gypsum is less harmful. The quicklime needs to be slaked (combined with water) to produce calcium hydroxide [Ca(OH)2]. This involves a highly exothermic reaction as the temperature would rise over 100°C as the water evaporates. The lime putty sets by absorbing water-soluble carbon dioxide (CO2) from the air (carbonation). Lime plaster takes far more time to set (up to weeks or months) compared to a few days for gypsum.

On the other hand, once set, the result of lime plaster is durable and impermeable. The slower the set, the better the outcome. In contrast, gypsum requires less temperature and fuel, but careful temperature management is crucial for success. Ideally, the natural gypsum calcium sulphate dihydrate (CaSO4·2H2O) is heated up to 130–180°C to form a hemihydrate (CaSO4·1/2H2O, also known as bassanite or Plaster of Paris), in which three-fourths of the water has been driven off. This hemihydrate can easily revert to its original chemical composition by adding water. If the temperature exceeds 180°C, the material forms γ-anhydrite (γ-CaSO4) due to a second dehydration, which is soluble and will still revert to hemihydrate once combined with water, but it is more sensitive to moisture in the air. If the temperature exceeds 260°C, the anhydrite forms insoluble β-anhydrite (β-CaSO4) that cannot readily revert, as it poorly accepts water and no longer binds; hence, it is useless for plaster.

The work organization also requires time, labour, and facility management skills. Making plaster from a rock is demanding work on a communal level. The limestone rock is quarried off-site and needs to be transported. Firing the rock (at the quarry or closer to the settlement) requires building a kiln, which can take up to a week. Then, the kiln must be guarded and the temperature managed for 2–3 days before allowing it to cool. The burnt material needs to be ground and mixed with water, the latter preferably closer to where it will be used. Finally, the plaster must be shaped quickly into the desired shape before it starts to set. The setting is further sensitive to weather conditions, so the working schedule is narrowed to the dry season. In contrast, gypsum plaster can be obtained by kiln firing or open-firing outcropped gypsum soil (an area of gypseous soil is cleaned from topsoil and covered with straw and dung before firing for approximately 3 days). The latter is less time consuming and requires less labour, but it is also less pure. Ethnographical studies have shown that a few people can do the production. This process has been described in detail by Kume (2013).

4.1 Choices

The specific choice of the material depends on many factors. Therefore, it is crucial to study the physical properties through archaeometric analyses of the raw materials to understand the production and the organization around it – where the raw material originates from (geology, quarrying); trade and transport issues (based on geography, historical, and ethnological sources); how and when the manufacture and production steps are organized (locally, seasonally); and how the material is applied in different contexts (indoor, outdoor, storage).

Human actions have material consequences that are traceable in the use of certain materials. Therefore, behavioural theory often influences material culture interpretations; however, when focusing on materials like plaster, it is necessary to approach it with the same pragmatism as the ancient users may have done during the container’s lifetime. If the chaîne opératoire traditionally comprises the initial phases of becoming plaster and container, we may add two phases: active use and passive use. Here, passive use refers to the opposite of active use, i.e. inactive use. These four phases are linked to technical choices and people involved (see indicative list in Table 2). SA reminds us that we cannot assume that these phases are necessarily followed in a linear evolutionary order but may occur simultaneously or even in reverse order where passive/inactive once more become active. A broken vessel can be turned into a new object, for instance, a scraper. An abandoned vessel can be used again millennia later. It can be actively displayed at a museum or be passive/inactive in museum storage. The line between active and passive is fine and subjective. Being aware of how we define an object clarifies our bias towards it. The relationship between humans and the material world cannot be emphasized at the expense of others. We cannot eliminate the human aspect as little as we can remove materiality.

Journey of a plaster container from raw material to non-active use is linked to technical steps, choices, and people involved

| Becoming plaster | Becoming a vessel | Active use | Passive (inactive) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actions | Quarrying rock | Shaping in/around basketry/pit | Containing | Being maintained |

| Building lime pit/kiln | Shaping by coiling | Short-/long-time storing | Being repaired | |

| Gathering fuel | Surface treatment | Carrying | Being reworked into a new product | |

| Controlling fire | Setting/drying | Preparing | Archived | |

| Grinding burnt stone | Serving | Deposited (grave/“safekeeping”) | ||

| Mixing powder into a slurry | Displaying | Discarded | ||

| Transporting | Transporting | Being rediscovered | ||

| Recycling material | Reusing | Looted/excavated | ||

| Means | Knowledge, time, possibility, fuel, fire, raw material: rock, soils, recycled plaster, people | Tools, other vessels, space knowledge, people, time | Space, people, other commodities | Tools, knowledge, people, space, time |

| Choices | Manufacturing techniques | Method of shaping | Use (daily/long storage, context, with what commodities) | Discarding or repairing |

| Raw material | Method for surface treatment and/or decoration | Ownership | Worth-value repairing | |

| Acquisition of fuel and raw materials | Chosen craftsperson | Users | Maintain/repair techniques | |

| Management of time and workforce | Chosen craftsperson | |||

| Ownership | ||||

| Burial gift context | ||||

| Excavation techniques | ||||

| Lab and analysis methods | ||||

| Actors | Community, family, individuals | Specialists | User | The repair person |

| Gender, age, hierarchy, local, foreign, strong/weak, knowledgeable, specialists | Local/foreign | Owner | The person who discards. | |

| Age | Gender | The person who reuses | ||

| Age (children) | The deceased | |||

| Domestic | The looter | |||

| Hierarchy | The archaeologist | |||

| The museum conservator | ||||

| The audience | ||||

| Where | Mine, kiln, pit, | Offsite + transport on site | Stationary/mobile | Indoors/storage rooms |

| Offsite-to-site transport | Domestic outdoors | Indoors/outdoors | Outdoors/outside the village | |

| Onsite | Specialized workshop | Public areas/nuclear family | Trash heap | |

| Inside/outside the village | Archaeologic context | |||

| Storage short-term/long-term buildings | Storage/lab | |||

| Museum storage/display | ||||

| When | Seasonal or ad hoc | Seasonal or ad hoc | Daily handling | At a set period of use |

| Weeks to months | Days to weeks | Storage | Frozen in time: burial | |

| Occasionally | Out of context/time | |||

| Continuity generation after generation | ||||

| Relationships | Space: geology, raw material, fuel, water, trade | Knowhow: typology | Functionality | New use: new object ideas |

| Tools: hammer, chisel, fire, means of transport | Other containers: basketry, ceramics, stones, wood | Content: liquid, dry bulk, organic food, inorganic objects | Cognitive long-term planning | |

| Knowhow: trade of ideas, technical skills, social cooperation | Tools: for burnishing | Other containers: ceramics, basketry | Economic thinking | |

| Space to dry | Burial: emotions and beliefs | |||

| Memory/information carrier |

The journey is divided into four major phases. Each has different parameters and actors. At every stage, new questions arise. The list is indicative of how to approach the journey and must not be seen as complete.

4.2 Manufacture

XRF and XRD analyses of the plaster material at Tell Sabi Abyad have shown the use of both limestone and gypsum plasters (Nilhamn & Koek, 2013). The majority was gypsum based. Limestone was used side by side with gypsum and was mostly found in the earliest layers. It is interesting to note that one went from a difficult and time-consuming technological process towards a more straightforward handling method. Even though limestone was available in the vicinity, and lime plaster was more durable, gypsum seemed to be preferred. Gypsum rock was not locally available, but there were some gypsum outcrops, approximately 20–70 km south of the site. The site Tell Mounbateh, contemporary with Tell Sabi Abyad, lies right next to such an outcrop (Mulder, 1969). Tell Mounbateh, an important regional site, may have functioned as a trade hub, perhaps also for raw materials like gypsum. Gypsum plaster ware was also found at the site (Copeland, 1979).

No kiln for burning rock has been found at Tell Sabi Abyad, suggesting that the burning of the raw material was done where it was mined. Still, the open bonfire method may have been used. At SAB I Operation I, level 7, a shallow pit 2 m × 0.6 m has been found that may have been used for firing as the bottom had limestone (rock unconfirmed) with white (lime) particles, ash, and charcoal. It is unclear whether this was left over from firing raw material or grilling larger pieces of meat (Akkermans et al., 2014). This bonfire method is still used in the northeastern Syria (Kume, 2013).

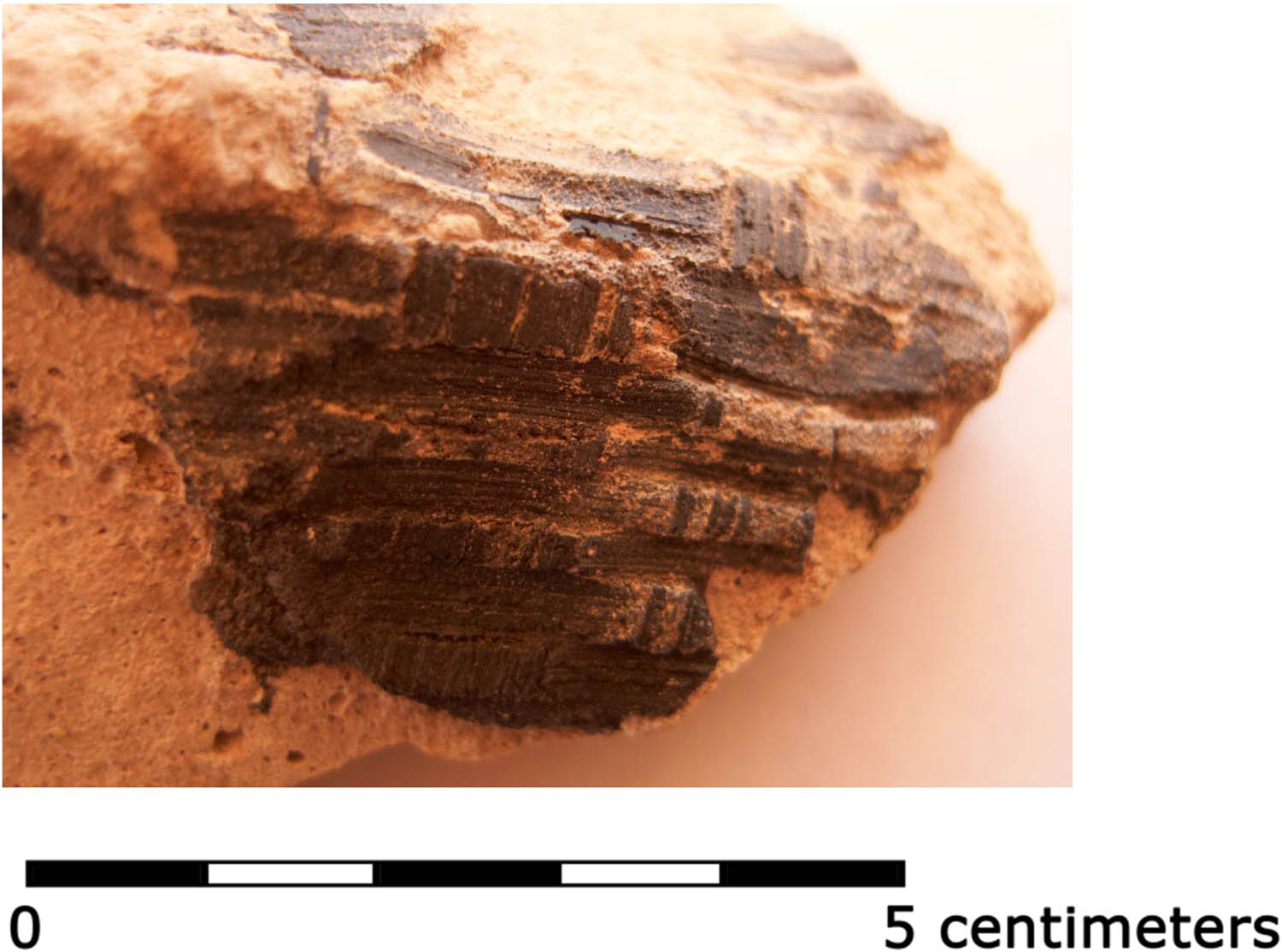

At Tell Sabi Abyad, plaster containers were made in two ways. First, a vessel could be built up by adding segments on top of each other to raise the walls horizontally. This coiling or “sequential slab technique” is seen in the finished material as the coils dried in phases and sometimes peeled off (Figure 8). Another method is casting, where the plaster is added to the interior or exterior of another object. The numerous impressions of now long-gone basketry evidence this process. Most impressions (91–158 imprints) are found on the plaster vessels’ exterior side, indicating that the plaster was put inside another vessel (Figure 9). However, there are also sherds with basketry impressions on their interior side (18 sherds). Vessels could also be made by plastering smaller dug pits, where they remained until the paste set, and the object could be moved. How common this method was is unclear, as only two smaller items have been identified with confidence. Larger objects made in pits were likely not portable and stayed permanent in situ (as bins). Sometimes pieces of pottery or stones were included in the paste to give the vessel more sturdiness. Flaking of layers and colour differences between layers are commonly seen in the material. Sometimes the outermost layer is made of finer and smoother material, perhaps as a finishing coating.

V07-340 Plaster ware rim sherd with at least three different segments/coils visible, indicated in red (photo: author).

V08-42 Gypsum plaster ware bowl with an impression of plated basketry on the exterior side, Tell Sabi Abyad (level A1) 6335–6225 cal BC (photo: author).

One must not confuse ware with the different forms (morphology) or how the vessels are shaped into these forms (Van der Leeuw, 1993). However, the methods of shaping a vessel limit the variability of style. Of the SAB I operation III assembly, 29.5% were open vessels, 19.1% were closed, and 7.2% were straight walled (remaining % uncertain). The open bowls are generally no taller than 20 cm (with some exceptions up to a half-meter). On average, their diameters were around 33.1 cm (SD 19.23) for open bowls and 23.0 cm (SD 13.95) for closed vessels, and the estimated volume was between 1 and 14 l. The vessels could have large diameters of up to 60 cm. A larger radius makes them clumsy to handle, and one could question where the size limit for a portable object ends and an architectural feature begins (cf. Figure 5). This calls for reflection on how many persons are required to transport it, for how far and how often. Further, in this way, the plaster crosses the boundary between vessel and architecture categories.

5 Use and Function

Plaster vessels frequently have beaded rims, and some items have been seen with knobs on the exterior, perhaps to make it easy to handle the vessel. The beaded rim made it easier to close the vessel off by covering the opening with a cloth or a hide tied to its place by a piece of string underneath the rim. This suggests that open bowls were for daily use at a specific working place, while smaller beaded rims and closed vessels were portable. Larger beaded or closed vessels may have functioned as long-term storage of organic commodities and food. Particularly, lime plaster vessels may have been convenient for this purpose, as the plaster’s alkaline composition is antiseptic and antifungal, while their hygroscopicity protects the contents against moisture (Rehhoff et al., 1990; Nilhamn et al., 2009). Grain was found within some plastered bins.

Considering the typology, these vessels do not meet the standard requirement for being storage vessels for liquid. Liquid containers are often portable, easy to handle, and have a spout, narrow orifice, or a tap. Preferably, they are easy to close off so as not to spill content while moving, and it is easier to keep content fresh and unspoiled in a closed vessel. Further, they must be impermeable to keep the liquid and reasonably resistant to mechanical shock so as not to crack easily (Nieuwenhuyse & Nilhamn, 2011). The chemical and physical properties of plaster also make it unsuitable for liquids. Here, it is further crucial to understand the raw material. Even if the end results superficially often look quite similar, containers made in either plaster category have different performance properties. The solubility of lime plaster (CaCO3) in 25°C water is much less (0.015 g/L) than that of gypsum (CaSO4, 2–2.5 g/L; Kingery et al., 1988). Hence, lime plaster is more water resistant, is harder, and survives mechanical wear and tear much better. Lime is also less vulnerable to fungal and bacterial growth as it is alkaline and allows moisture to evaporate quickly.

This does not mean that gypsum plaster dissolves immediately. On the other hand, it may attract fungal and bacterial growth when exposed to fluctuating moisture levels due to its pores and interstitial spaces where moisture can be trapped. Experiments have confirmed that gypsum plaster is susceptible to mould growth, water damage, and the development of salt efflorescence (by weather and wind; Nilhamn, 2017). Further, the relative hygroscopicity of gypsum means that water is more easily sealed between individual plaster layers, especially if they have different compositions, causing layers to flake off.

Still, gypsum was preferred at Tell Sabi Abyad. Perhaps there was no need to put liquids in these vessels. However, there were methods to improve water resistance. One could burnish the surface or impregnate the plaster with sealing agents, such as beeswax, soap, or oily substances, as done in the “qadâd” and “tadelakt” [lime] plaster methods (Sutter, 1999). The sealing material would be applied with a brush or cloth when the plaster was completely dry. The fine scratches and brush marks on many plaster sherds may be traces of such treatment. The burnishing of plaster containers is also attested at the site by a few sherds that show the characteristic traces. Another method uses bitumen (Figure 10). Eight plaster sherds have been found with bitumen at SAB II and III, some with basketry impressions (Berghuijs, 2013, Connan et al., 2023; Verhoeven & Akkermans, 2000).

V10-999 Bitumen found on plaster ware Tell Sabi Abyad SAB III (© E. Koek, Tell Sabi Abyad Archive).

ORA of plaster ware using GC-MS have not yielded any results. However, this must be treated cautiously, as it may give a false picture. Experiments have revealed that the properties of the different wares result in different absorption abilities and survival rates of organic residues through time. Plaster appears to be less able to retain residues than many ceramic wares. Hence, this may explain the lack of evidence for lipid products in the plaster. Although a vessel once may have been exposed to fatty compounds, archaeologists can no longer detect it by using the same standard methods as for pottery extraction. It calls for adapting our analysis methods when targeting plaster (Nilhamn, 2023).

6 Relationships

6.1 Cultural Setting

The introduction of plaster ware (and pottery) for making portable containers occurred around ca. 7000 cal BC. It has been proposed to be associated with an abrupt change in settlement densities and site locations (Le Mière & Picon, 1999; Nieuwenhuyse & Campbell, 2017; Tsuneki, 2017). In the case of Tell Sabi Abyad, abrupt change is not attested. Instead, there is a continuity of the settlement from PPNB through the IPN into the EPN. This may be because of the favourable location of the site. The population during the IPN was concentrated in the valleys of Balikh and Khabur. No IPN or EPN sites have been found in the semi-arid steppes between these valleys, indicating a need for secure (perennial) water sources, such as rivers and rain. Extensive surveys in the Balikh Valley have only yielded four IPN sites in the region (Tell Sabi Abyad, Tell Damishliyya, Tell Assouad, and Tell Mounbateh). All are situated north of the present-day 220 mm isohyet (Nieuwenhuyse & Akkermans, 2019). Tell Sabi Abyad was part of a broader exchange network where bitumen, mineral-tempered pottery, stone vessels of non-local stones, limestone, and gypsum rock were traded.

During the EPN, the sites were small, with few inhabitants. The spatial distribution of a few circular buildings and large open spaces with hearths, kilns, and bins suggests a communal setting. Plaster production fits in this picture. Tell Sabi Abyad, Tell Halula, Seker al-Aheimar, and Shir show that pottery and plaster were used side by side. Not all sites adopted pottery immediately in the EPN. Especially sites south along the Syrian Euphrates and in the Syrian interior adopted pottery much later (Akkermans & Schwartz, 2003); some of these sites, like Bouqras and El-Kowm, continued to use plaster ware instead.

At the end of the EPN, the spatial organization shows an increase in larger containers inside the houses. The use of seals became more frequent, supporting the idea of property and storage management (Duistermaat, 2013).

Sites dating to the pre-Halaf, Transitional, and Early Halaf (Halaf I) are all situated in the northern parts of valleys of the Euphrates, the Upper Tigris, the Balikh, and the Upper Khabur (Nieuwenhuyse & Akkermans, 2019). After 6250 cal BC, the steppe started being populated, causing a cultural change on several economic, administrative, social, and perhaps religious levels. Transport routes or social interactions changed the former exchange patterns. Products of rock material ceased. The pottery was mainly of local production, with some exceptions. The spatial organization in the village changed with large rectilinear buildings with many collective storage rooms. The village may have served as a storage hub for the semi-pastoralists in the region (Akkermans & Verhoeven, 1995; Akkermans & Schwartz, 2003; Verhoeven, 1999). In addition, many smaller round buildings may point towards family-oriented households. Stamp seals and abstract tokens became common (Duistermaat, 2013).

The environmental circumstances called for adaptations. Villages relocated and changed from agriculture and pig husbandry to semi-pastoralism of cattle and hunting. The domestication of aurochs led to the introduction of new dairy products (Evershed et al., 2008; Nieuwenhuyse et al., 2015). Containers were needed for food preparation, cooking, and storage. The painted serving pottery may also indicate new social habits of displaying status within a group. Flexibility was required for survival. The plaster was not flexible enough to keep up.

6.2 Architecture

Plaster was used for floors, walls, and stationary containers, such as bins, basins, and silos. In most cases, the plastering is a few millimetres thick finishing coating or whitewash, which must be redone regularly.

Plaster walls and floors are attested in the EPN levels and onwards. Twelve bins have been identified as made of white plaster (with the remark that field notes often state plaster without clarifying if it is of lime, gypsum, or mud origin). Most bins were oval with an average diameter of 50 cm. Round and square items occurred. Larger installations and silos were also built. In level A4, an estimated 4 m large basin (2.25 m still intact when found) was coated with 1–1.5 cm thick plaster (Akkermans et al., 2006). Another item has been estimated to be between 1.3 and 2 m (V04-209). In SAB I operation I level 7, two circular silos have been found inside houses with a diameter of 1.62 and 1.22 m. Their 30 cm clay walls were covered with thick plaster on the interiors, while the floor remained hard mud.

Plaster was used in the transitional time. A few buildings in level 8 (SAB I, Operation I) show traces of plaster floors and 1–2 mm white coating on the walls. In level 7, plaster was used as a coating or whitewash on the mud walls. In particular, the exterior facades of round buildings (tholoi) were plastered. However, not all tholoi were plastered, indicating a differentiation. The plaster was also used for interior features. Room 2 of house 6.15 (level 6/BV – Burned Village) had a square lime plaster bin with several complete household tools. In the following level 5, there is a notable change. Now the plaster was mainly used for whitewashing interior mud brick walls. The houses indicate that the activities earlier in the open areas had moved indoors. Not all houses or rooms within houses had plaster, once again, showing a certain differentiation. One room in building 5.8 had traces of white plaster close to the doorway. Plaster pieces with red paint found right underneath it suggest that the wall may have been painted. In 2010, small black-on-white-painted wall plaster areas were discovered in level A2. This was detected still on the wall for the first time at Tell Sabi Abyad (Akkermans & Brüning, 2023, p. 27). The painted architectural plaster strengthens the theory that some plaster objects may have been painted. Whether the plaster ware was made as a by-product when making plaster for walls and floors is still unknown. This hypothesis will be investigated in future research when analyzing and comparing plaster.

6.3 Other Containers

6.3.1 Pottery

In the IPN, pottery and plaster ware at Tell Sabi Abyad were scarce. The containers had small volumes with limited uses. The fragile mineral temper pottery was of a non-local origin (Le Mière, Merle, & Picon, 2018). Around 6700 cal BC, plant-tempered pottery was introduced. First (levels A10-A9), a mixture of mineral and vegetal temper was used. Gradually, the use of organic straw temper increased. This coarse ware made it possible to construct larger vessels. In particular, in levels A6–A2, pottery increased in height, weight, and capacity. It created new uses for pottery. Similar to plaster ware, pottery was shaped using the coiling method. In the beginning, the pottery had comparatively simple shapes similar to those displayed in the plaster ware. Often the ceramic vessels were vertical straight-walled pots with loop handles on either side (a feature not retrieved in the plaster ware), hole-mouth pots, and S-shaped vessels, characterized by a low, non-distinct collar. Later, the S-vessels would evolve into real jars with tall, distinct necks by the end of the period (which occurs but is rarely noticed in the plaster material). At around 6200 cal BC, the pottery developed new shapes and features not found in the plaster ware. The so-called cordons – appliqué bands running horizontally below the vessel rim – may have been used to fix a piece of cloth with a rope, similar to the use of the beaded rim of the plaster ware, a feature rarely seen on the pottery.

The larger ceramic vessels were most likely intended for dry goods, while liquids may have been kept in the smaller or taller pottery vessels that were easier to handle. Even though most of the pottery during the EPN was predominantly porous, plant-tempered, standard coarse ware and therefore not suitable for storing liquids for longer periods, there were means to reduce the porosity. One way was to burnish the exterior walls of the pot. In the later phase of the EPN, it was ubiquitous to plaster the coarse ware on the interior or exterior (and sometimes both) with gypsum plaster. Especially taller vessels seem to have been plastered. This is interesting, as traditionally, jars were used for liquids. For short-term storage, the high hygroscopicity of the gypsum may be beneficial because even if it did not make the material waterproof, slow evaporation through the walls kept the vessel and the water inside cool. Like the larger immovable plaster vessels, larger pottery vessels were sometimes dug into floors. Often these were situated close to the entrance of buildings. Nieuwenhuyse proposed that these containers were meant for water, ready to use when entering the building (Nieuwenhuyse & Nilhamn, 2011; Nieuwenhuyse & Koek, 2018). As with the plaster ware, plastered ceramics may have been used for long-term storage, especially for dry organic goods.

Another relationship between pottery and plaster is that gypsum plaster was used for repairing broken pottery (Nieuwenhuyse & Dooijes, 2008; Nieuwenhuyse & Koek, 2018). The composition of the plaster used was similar to that of the plaster ware (Nilhamn & Koek, 2013).

6.3.2 Basketry

It is not possible to discuss the earliest basketry without starting with bitumen. The first imprints of basketry occur in bitumen in PPNB. The earliest bitumen at Tell Sabi Abyad dates to PPNB 7550–6850 cal BC, and indeed, the oldest sample shows basketry imprints. One plaster ware sherd was found in the PPNB coated with bitumen and basketry imprints showing that all materials were used together. Bitumen had to be imported from different sources. Samples dated to 7200–6400 cal BC have been identified as imported from the southern desert of Jebel Bishri, most likely Wadi Bishri. Especially, bitumen associated with basketry seems to originate from here. The bitumen lumps were probably part of the trade exchange and followed the exchange patterns of pottery, which is supported by the fact that the earliest pottery at Tell Sabi Abyad was non-local mineral ware. The numerous bitumen with basketry imprints (125) show that basketry was common in the PPNB and IPN. Eight plaster ware sherds have attached bitumen. Two of these show plaited basketry impressions (Berghuijs, 2013; Connan et al., 2023). The combination of plaster and basketry seems to peak in the A4 level with 34 plaster vessels with basketry imprints (cf. only 16 sherds in level A2 and 24 sherds in A1). It is unclear if the basketry was used as a mould for making plaster vessels or if the plaster was applied to make the basket more solid. Sometimes, the imprints are so deep that removing the plaster after setting must have been impossible. In other cases, parts of the vessel show basketry impressions, while the rest of the plaster ware has been smoothed or burnished. The plaster wares with bitumen and basketry impressions indicate the close relationship between the container categories and the transition from bitumen-coated basketry to the use of plaster and pottery as primary containers.

6.3.3 Stone Vessels

Plaster ware can be so solid that it is mistaken for a vessel carved out of stone. Stone vessels were common at Tell Sabi Abyad. They were made of non-local rocks, indicating trade. In the early IPN, they were more common than plaster ware and pottery. In levels A16–A11, 109 stone vessels were found (excluding mortars made of basalt), compared with 100 plaster ware sherds and 35 pottery sherds. These IPN stone containers were small, with an average diameter of 9.2 cm. The typology of the stone vessels stays similar over time (Akkermans et al., 2006; Figure 14) and is comparable with plaster ware. However, much smaller (diameter rarely larger than 12 cm), they most likely had other purposes than the plaster ware.

7 Discussion

As the material of Tell Sabi Abyad shows, there is an advantage to approaching plaster, particularly plaster ware, through SA, balancing the exact sciences of archaeometry and the theory of materiality from an unbiased perspective. Shanks (2007) summarizes SA’s essence as the archaeologist’s attitude built on four components: process, creativity, mediation, and distribution. This attitude is based on the awareness that the process of making an artefact, and the study of its remains is bound into a continuous relationship, as “the past” has no end but is a constant process that all users along the line, including the researcher influence. This requires a creative mind that sees both the remains of the studied object and the (in)direct relationships as important resources to understand the bigger picture. It also calls for creativity to translate/mediate the findings unambiguously so that they (and their relationships and memory) will become accessible to others.

The question of how the researcher relates to and treats “plaster” is equally important as understanding what it is, how it is made, and why. The physical properties of the material call for archaeometrical and geo-archaeological questions, while the container typology raises questions of function and symbolic elements and their impact on the social society (material agency/theoretical archaeology). Therefore, our approach goes further than the “ceramic ecology” approach (Matson, 1965; Kolb, 2000), which argues that one should first investigate the relationship between technology and the environment before putting the ceramic in a cultural context. In our view, all aspects have an entangled relationship (Figure 11).

The entangled fields of study when studying material. Raw material, geological source, and physical properties are in a relationship “entangled” with how the performances of the material relate to how the objects were shaped and used. This, in turn, relates to why certain raw material was chosen due to a combination of the influence of social context and (trade) network.

Freely paraphrasing Kirshhoff’s material agency theory (2009) and with reference to Latour (1999, pp. 178–180): “If it is equally credible to assign the same functional role to [plaster] as we usually or intuitively do to [pottery], then [plaster] is part and parcel of the process constituting [‘human interaction with containers’].”

True, it is important to acknowledge and study the relationships, but relying on material agency theory only, based on the functional relationships, as the aforementioned statement indicates, is unwise (as Kirchhoff also pointed out in 2009). The plaster and pottery materials from Tell Sabi Abyad show many similarities regarding functionality and typology. However, it does not imply that the two materials should be treated and interpreted identically. On the contrary, the physical material and the chaîne opératoire are still of importance.

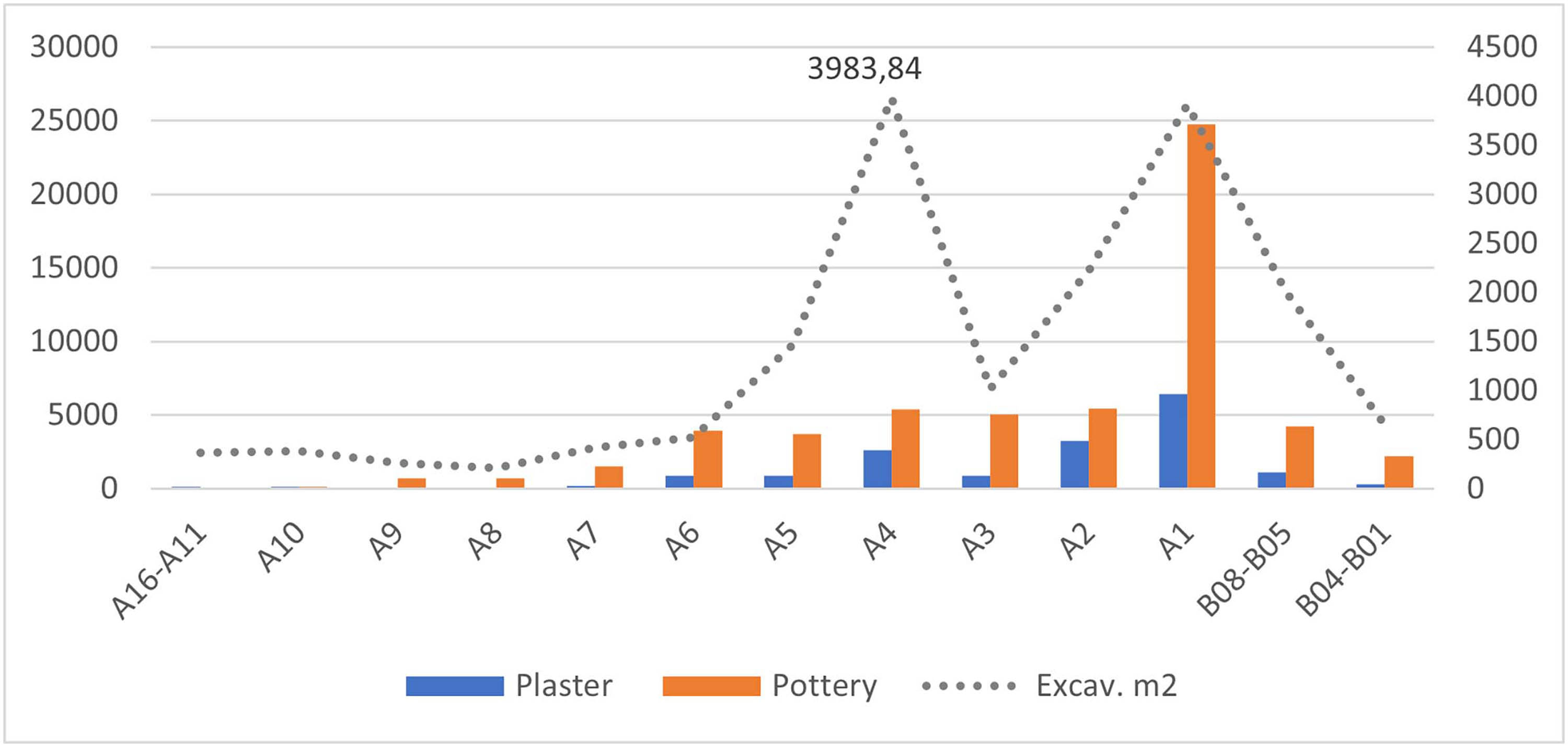

Until the EPN (SAB layer A10), plaster ware was as frequent as pottery or even slightly more common. They were both products dependent on the import of raw materials or final products. Around 6200 cal BC, the use of plaster ware declined while pottery flourished (Figure 12). One plausible explanation is that plaster production was comparatively costly in terms of fuel (Rehhoff et al., 1990). The 8.2 k.a. climate event, associated in Southwest Asia with a 150- to 200-year period of lower temperature and less precipitation (Alley et al., 1997; Akkermans & van der Plicht, 2020; Van der Plicht et al., 2011), may have made fuel scarce. Further, there may (also) have been a constraint on the supply of geological raw materials due to changes in trade routes or regional socio-politics. The extent to which the event affected the region is still under discussion (Flohr, Fleitmann, Matthews, Matthews, & Black, 2016). Nevertheless, it is clear that the material culture displays an adapted lifestyle around this period, both regarding architecture and settlement organization (Akkermans, van der Plicht, Nieuwenhuyse, Russell, & Kaneda, 2015; Akkermans & van der Plicht, 2020).

Raw count sherds of plaster ware and pottery in relationship with excavated areas (in m2) of SAB I Operation III. See Figure 4 for the date of levels A and B.

In contrast to pottery, plaster-making concerns a more significant social interaction and cooperation. A single person can gather local clay, clean it, add temper, shape it into the desired vessel, and make a fire oven to fire it. However, making plaster, especially limestone plaster, involves more time management skills offsite, transport, and seasonal planning for the community. Open-fire gypsum plaster manufacturing is less demanding, which can be one reason why gypsum was preferred instead of limestone. Making plaster is more seasonal as the setting is sensitive to weather conditions. This is not an issue for pottery as the firing finalizes the product, making it easier to balance supply and demand in case the demand for containers grows and the village social organization changes.

Another plausible reason plaster ware fell out of use is that the variety of shapes feasible to manufacture was too limited for the needs of the inhabitants, and ceramics was a much more versatile material. Pottery could be heated and put over a fire. The plaster could not, as it would deteriorate if burnt. Even though it cannot be denied that plaster vessels could have held liquid temporarily, the material and the typology (shape and size) suggest that this was, at least, not their primary function. Instead, plaster was more suitable for storing dry products, such as dried plants and grain. After 6200 cal BC, the shapes in pottery became more voluminous. At the same time, some pottery became finer and more elaborate. These new items may have indicated that feasting as a social phenomenon had reached another stage where the decorated serving “tableware” became part of the feast as displayable items (Nieuwenhuyse, 2007).

In the end, pottery won against plaster ware. It was not an immediate process. People kept making it. Was this out of tradition, emotional ties, or laissez-faire, or was it rational thinking not to waste left-over material after plastering walls and floors? Perhaps a communal effort and a seasonal social event for making it kept the tradition alive on a small scale.

Today we use plastic, but did that immediately stop us from using ceramics and glass when plastic became available? Plastic is more malleable and lighter, and in the beginning, there was no common knowledge of the health risks that the phthalates, bisphenols, and fluorinated compounds brought. Still, glass and ceramics remained as there were more than rational aspects involved. Preferences (but also indifferences) go deep and can be based on rational thinking as well as emotional involvement. Indeed, emotions and people’s material engagement are interrelated. Harris and Sørensen (2010) even consider this interrelation as fundamental.

It is true that pottery that is decorated, perhaps imported from distant places, has traditionally been given a high status within a society by archaeologists due to its exclusivity. However, it would be presumptuous to say that pottery immediately had a stronger (emotional) value. These rather sturdy plaster ware objects continued being used generation after generation even when they were not manufactured on a large scale anymore. This may explain the incidental occurrence in, for example, the following Halaf-period context. There are also several cases at Tell Sabi Abyad where the plaster ware seems to be used entirely out of chronological context. For example, Neolithic plaster ware was found in the Late Bronze Age context, indicating that it was recycled from a pragmatic point of view: “I found a vessel I can use.”

It is, therefore, dangerous to assume that material out of the “expected context” is due to disturbance. Further, the life or value of an object category does not immediately stop after the production peak. From a symmetrical point of view, this is logical. An object does not cease to exist because the context changes or it no longer belongs to the first user/owner. It may form other relationships with the world around it. The object is still an entity that builds new memories, habits, and meanings nonstop. In the same way, a vessel used as a grave gift is frozen for us archaeologists in the context where we find it, but for the one who deposited the vessel, it had another, perhaps eternal meaning.

8 Conclusion

Approaching new materials gives us fresh insights into a society’s social and economic environment. Perhaps most importantly, it stimulates archaeology as a science to see that archaeology does not have its starting point in the past but in the here and now. Metaphorically speaking, we must first understand the palimpsests of the topsoil layer before heading for the deep-lying past. It also means we must stay aware of the power of (pre-set) categories and terminology. The facts that plaster ware resembles pottery in shape, typology, and function – though it is far from it material-wise and in terms of chaîne opératoire – and that the material, plaster, is often (too) associated with architecture has (unintentionally) influenced previous approaches.

Limestone and gypsum plasters also differ and have two slightly different chaîne opératoire. The archaeometric analyses (XRF, XRD, optical microscopy, SEM, and ORA/GC-MS), GIS, archaeological and geological fieldwork, in combination with ethnological sources and experimental archaeology (plaster and container production, pigment, and ORA experiments), provide us with valuable information about trade-networks, technological choices, usage, and functions, but also the limits and boundaries of these materials. Stratigraphic data (Figure 12) tell us about space and time and how, when, and where usage, technological choices, and development occurred. These data would have been missed if plaster had been treated as a mere sidekick to pottery.

As the case of Tell Sabi Abyad shows, it is impossible (and unwise) to neglect the relationship of plaster with ceramics, as the two materials co-existed for a long time. However, ceramics should not overshadow the importance of the plaster material. The findings show that innovations generally did not happen because of intentional engineering. The material study allows us to follow the gradual changes in Upper Mesopotamia in close detail and investigate how these container innovations fit into the broader transformations in Neolithic subsistence and social organization.

Plaster ware emerges in PPNB and IPN when villages form at specific locations; the plaster indicates stability in a communal social structure. In the IPN and EPN, limestone plaster points towards trade routes to quarries in the south and the presence of enough fuel. Limestone ceased to be used as raw material for plaster after 6350 BC. Perhaps, it is a sign that both trade routes to quarries and fuel were less accessible. Instead, the inhabitants chose gypsum. Plaster starts to cease in the Pre-Halaf when the villages choose a semi-sedentary life again. After 6200 cal BC, new social patterns evolve, leaning towards property ownership. There was a need for storage facilities and larger, sealable closed-shaped vessels. The shaping of plaster products limited the possibilities for larger shapes, especially for closed vessels. The new economy, leaving agriculture as the primary source and turning to semi-sedentary herding, called for adaptation. Plaster ware, suitable for storing agricultural products such as grain, turned out to be less ideal for heating and processing dairy products. Another essential aspect was that plaster production is more likely to be a seasonal activity, while pottery production is more flexible to suit the demand of a semi-sedentary community.

Olsen stated in 2007 that SA as a concept would hopefully soon be superfluous. Fifteen years later, there are still vivid discussions about materiality. Watts (2018) stated that materiality as a concept continues to develop, as seen in the preference for the more expansive and transdisciplinary term “new materialism.” Witmore (2019) argued that the symmetrical argument cannot provide any applicable theory. However, perhaps SA does not give us a handbook to follow point by point when studying plaster, but it is still applicable as it makes us aware that we, as researchers, should not be prejudiced and limit our research to focus only on what we know and assume. Instead, we should study material from a more all-inclusive perspective using data from and for fieldwork, archival finds, document processing, stratigraphy, archaeometry, geology, and human-oriented sciences, such as psychology and ethnography, particularly because we are not one-sided specialists.

Moreover, the material is not a one-sided entity either. This approach brings the analytical side of materials and archaeological theory closer together. By reinjecting into archaeology, a fair portion of what Witmore (2019) calls “analytical agnosticism,” i.e. scrutinizing the world with a “tabula rasa” mind not yet affected by experiences or impressions, we can explore different facets and open up an awareness of find categories beyond the traditional ones.

The study of plaster ware challenges our choice of terminology. “White ware” is confusing and inaccurate. So, should white ware as a terminology be changed? Yes, even though it is an established concept within Near Eastern archaeology. It would be better to talk about plaster ware. Even though plaster as a word itself can refer to many types of chemical compounds, the author suggests that highlighting plaster makes this ware less ambiguous for the main audience and enhances the importance of the raw material. Ware still keeps the relation to container ware. Doing this gives the find category its own podium to tell the story of its role within the Neolithic society.

Abbreviations

- ANT

-

actor-network theory

- DTA

-

differential thermal analysis

- EPN

-

early pottery neolithic

- GC-MS

-

gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- GIS

-

geographic information system

- IPN

-

initial pottery neolithic

- IR

-

infra-red

- ISO

-

International Organization for Standardization

- ORA

-

organic residue analysis

- PPNB

-

pre-pottery neolithic B

- SA

-

symmetrical archaeology

- SAB

-

Tell Sabi Abyad

- SEM-EDS

-

scanning electron microscopy-energy dispersive spectroscopy

- TGA

-

thermal gravimetric analysis

- XRD

-

X-ray diffraction

- XRF

-

X-ray fluorescence spectrometry

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful for the assistance of Prof. Peter Akkermans, Akemi Kaneda and especially to Merel Brüning (all Leiden University) for answering impossible questions on short notice and with the aid of accessing the repository of objects and stratigraphy datafiles of the Tell Sabi Abyad Project, Martin Hense for the digitalisation of drawings and Dr Katrien Janine, Leicester university and Dr Hannah Plug, Liverpool University for their comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. All remaining errors lie with the author.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by a research grant received from the Nordenskiöld Trust (2022).

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The data supporting this study’s findings are available from Tell Sabi Abyad Project, Leiden University, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study and are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the author upon reasonable request and with permission of Tell Sabi Abyad Project.

References

Akkermans, P. M. M. G. (1993). Villages in the steppe: Later Neolithic settlement and subsistence in the Balikh Valley, Northern Syria. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Akkermans, P. M. M. G. (2013). Tell Sabi Abyad, or the Ruins of the White Boy: A Short History of Research into the Late Neolithic of Northern Syria. In D. Bonatz & L. Martin (Eds.), 100 Jahre archäologische Feldforschungen in Nordost-Syrien, eine Bilanz (pp. 29–43). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.Suche in Google Scholar

Akkermans, P. M. M. G. (2014). Tell Sabi Abyad I. DANS: Leiden University. doi: 10.17026/dans-294-p94z.Suche in Google Scholar

Akkermans P. M. M. G., & Brüning M. L. (2019). Architecture and social continuity at Neolithic Tell Sabi Abyad III, Syria. In P. Abrahami & L. Battini (Eds.), Ina dmarri u qan tuppi - Par la bêche et le stylet! Cultures et sociétés syro-mésopotamiennes, Mélanges offerts à Olivier Rouault (pp. 101–110). Oxford: Archaeopress.10.2307/j.ctvndv9gg.17Suche in Google Scholar

Akkermans P. M. M. G., & Brüning M. L. (2023). Dwellings with three rooms: A new type of architecture at late seventh millennium BCE Tell Sabi Abyad, Syria. In B. S. Düring & P. M. M. G. Akkermans (Eds.), Style and Society in the Prehistory of West Asia. Essays in Honour of Olivier P. Nieuwenhuyse, PALMA 29 (pp. 21–34). Leiden: Sidestone.Suche in Google Scholar

Akkermans, P. M. M. G., Brüning, M .L. Huigens, H. O., & Nieuwenhuyse, O. P. (Eds.). (2014). Excavations at Late Neolithic Tell Sabi Abyad, Syria. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers.Suche in Google Scholar

Akkermans, P. M. M. G., Brüning, M., Hammers, N., Huigens, H., Kruijer, L., Meens, A., … Visser, E. (2012). Burning down the house: The burnt building V6 at Late Neolithic Tell Sabi Abyad, Syria. Analecta Praehistorica Leidensia, 43/44, 307–324.Suche in Google Scholar

Akkermans, P. M. M. G., Cappers, R., Cavallo, C., Nieuwenhuyse, O., Nilhamn, B., & Otte, I. N. (2006). Investigating the early pottery Neolithic of northern Syria: New evidence from Tell Sabi Abyad. American Journal of Archaeology, 110(1), 123–56. doi: 10.3764/aja.110.1.123x.Suche in Google Scholar

Akkermans, P. M. M. G., van der Plicht, J., Nieuwenhuyse, O., Russell, A., & Kaneda, A. (2015). Cultural transformation and the 8.2 ka event in Upper Mesopotamia. In S. Kerner, R. J. Dann, & P. Bangsgaard (Eds.), Climate and ancient societies (pp. 97–112). Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Akkermans, P. M. M. G., & van der Plicht, J. (2020). Crisis in prehistorisch Syrië, 8200 jaar geleden? Tijdschrift voor Mediterrane Archeologie, 64, 1–7.Suche in Google Scholar

Akkermans, P. M. M. G. & Verhoeven, M. (1995). An image of complexity: The burnt village at Late Neolithic Tell Sabi Abyad, Syria. American Journal of Archaeology, 99, 5–32.10.2307/506877Suche in Google Scholar