Abstract

In this article, the archaeological and archaeometrical study of several roof tiles and bricks retrieved at the Etruscan Domus dei Dolia is presented. The Domus is located in Etrusco-Roman neighbourhood (Hellenistic – Late Republican periods, third–first centuries BC) of the ancient city of Vetulonia (central Italy), in the area of Poggiarello Renzetti. The main goals were to establish the characteristics of the raw material/s used in their production, the possible provenance, the technology applied, and to get insight regarding the production organization and the local economy. The archaeological materials were analysed by optical microscopy (OM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and X-ray fluorescence (XRF). Principal component analysis was also applied to evaluate/interpret chemical data. Results evidenced that roof tiles and bricks were produced using a different technology and raw materials. Roof tiles were possibly manufactured within 12 km from the archaeological site and imported into the town, exploiting two different raw materials. Conversely, bricks were likely produced very close to the archaeological site. So, it is supposed that raw materials were selected considering factors such as distance, abundance, and accessibility to natural resources and security.

1 Introduction

Etruscans were one of the most important and sophisticated ancient Italian civilization before the rise of Rome (Ceccarelli, 2016; Neil, 2016; Stoddart, 2016), and they had a great cultural impact on the Roman civilization. Known as Tyrsenoi or Thyrrenoi by ancient Greeks, Etruscan people ruled in the Italian Peninsula between the ninth and the first century BC. Their presence has been attested in different regions of central Italy such as Tuscany, Lazio, Umbria, Campania, in large areas of the Po Valley (Emilia Romagna, Lombardia, and Veneto regions) in northern Italy, and in the Corsica Island (France) (Cristofani, 2000). According to ancient sources, they are considered to have been organised through a confederation of 12 city states (i.e. normally defined as Decadopoli) linked one to each other by the same economic, religious, and military interests (Leighton, 2013). Etruscan culture has also been widely documented during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, thanks to the discovery of numerous necropolis with their funerary equipment, being evidence of the degree of their civilization (Steingräber, 2016). In addition, Etruscans are also extremely famous for their metallurgical skills, their ability in gold processing, their aptitude to trade and sail, and having contacts with the most important civilization of the Mediterranean Area (Camporeale, 2016). With the beginning of the third century BC, their civilization started to be absorbed by Romans, and it is worth mentioning that three of the first kings of Rome were Etruscan (Balassone et al., 2018; Camporeale, 1969; Cristofani, 2000; Cristofani & Martelli, 1983; Nestler & Formigli, 2013).

Although much information has been collected regarding the cult of death, very little is known about the world of the living. Several scholars have addressed Etruscan ceramic production technology and provenance (Bruni, 2012; Bruni, Bagnasco Gianni, & Ciarati, 2001; Ciarati, Bruni, & Fermo, 2001; Fermo, Cariati, Ballabio, Consonni, & Bagnasco Gianni, 2004; Ganio, MacLennan, Svoboda, Lyons, & Trentelman, 2021; Gliozzo et al., 2011; Gliozzo, Kirkman, Pantos, & Turbanti, 2004; Longoni et al., 2023; Maritan, 2004; Nodari, Maritan, Mazzoli, & Russo, 2004; Saviano, Drago, Felli, & Violo, 2002), or the effects of local natural resource exploitation to the surrounding environment and people health in the past (Harrison, Cattani, & Turfa, 2010; Magny et al., 2007; Sadori, Mercuri, & Mariotti Lippi, 2010). Regarding Etruscan architecture, available information is scarce (Edlund-Berry, 2011; Miller, 2015; Roos & Wikander, 1986), and only on architectural terracotta a great deal of attention has been directed toward the stylistic and iconographical study of ancient roofs (Lulof, 2014; Meyers, Jackson, & Galloway, 2010; Winter, 2002). Even less data are available regarding the exploitation of local natural resources for construction purposes such as wood, roof tiles, bricks, or earthen-based materials (Amicone, Croce, Castellano, & Vezzoli, 2020; Ammerman et al., 2008; Ceccarelli, Moletti, Bellotto, Dotelli, & Stoddart, 2020; Coradeschi et al., 2021; Weaver, Meyers, Mertzman, Sternberg, & Didaleusky, 2013; Winter, Iliopoulos, & Ammerman, 2009).

Considering the rarity of archaeological sciences studies on architectural construction material from the Etruscan period, several bricks and roof tiles recovered at the Domus dei Dolia (Vetulonia, Italy) were considered to develop an interdisciplinary study. These materials always had less attention from archaeological science specialists compared to the most famous pottery wares, for example. In any case, the massive production and utilization of construction ceramics in civil architecture can surely be useful/utilized to evaluate the economic organization behind their production, the exploitation of locally available natural resources, and the technology of production. So, by studying these materials, it would be possible to increase our knowledge of Etruscan civil architecture and, widely, the Etruscan world of the living, which is still nowadays largely unknown.

The Domus dei Dolia was discovered in 2009, and it is located in the ancient town of Vetulonia (Castiglione della Pescaia Town Hall, Southern Tuscany, Italy). The study of the archaeological evidence made possible the documentation of an almost entire Etruscan house, probably occupied between the third and the first century BC (Coradeschi et al., 2021; Rafanelli et al., 2018), in the last centuries of its Etruscan History. Among the different materials collected, we can mention different ceramic wares, mortars, wall painting fragments, votive bronze statues, coins, nails, numerous charred woods, wattle and daub earthen construction materials, in addition to several bricks and roof tiles.

The utilization of bricks has been widely attested in the Etruscan world as an important architectural component (Pizzirani, 2019). They were normally unfired, and dimensions and shape could be adapted depending on architectural needs (i.e. width of the wall or foundation). Non-decorated roof tiles are generally abundant in most sites, and differently from bricks, they were generally fired (Bonetto, 2019; Ceccarelli et al., 2020). Two different roof-tile shapes were normally employed in Etruscan architecture (Meyers et al., 2010). They could be planar (pan roof tiles – tegulae) or semi-circular (cover roof tiles – imbrices), and these architectural elements represent the basic units of a typical terracotta pitched roof in Etruria. The production was quite standardized (Meyers et al., 2010). A pan roof tile was generally rectangular in shape, and it could be long, up to 65/70 cm, and up to 50 cm wide, with raised side borders on the longest sides. Normally positioned one close to another, the bottom part of each tegulae overlapped the top of the tegulae below it, starting from the higher part of the roof to the lower sides. Each curved imbrices covers the joints formed between the side ridges of adjacent tegulae, and they were also partially superimposed on the smaller side. Using this system, the water could easily flow down the roof, protecting the structure of the house from water infiltration.

The objectives of the study presented in this article are as follows:

To evaluate/understand whether the construction materials were locally produced in the town or imported.

To evaluate if different raw materials were employed to produce bricks and roof tiles.

To understand the technology employed in the production of bricks and roof tiles.

To understand the reasoning behind exploiting different raw materials (if confirmed).

To evaluate the production organization of construction materials and to get information regarding the local economy.

2 Archaeological Setting

2.1 The Ancient City of Vetulonia and the Identification of the Domus dei Dolia

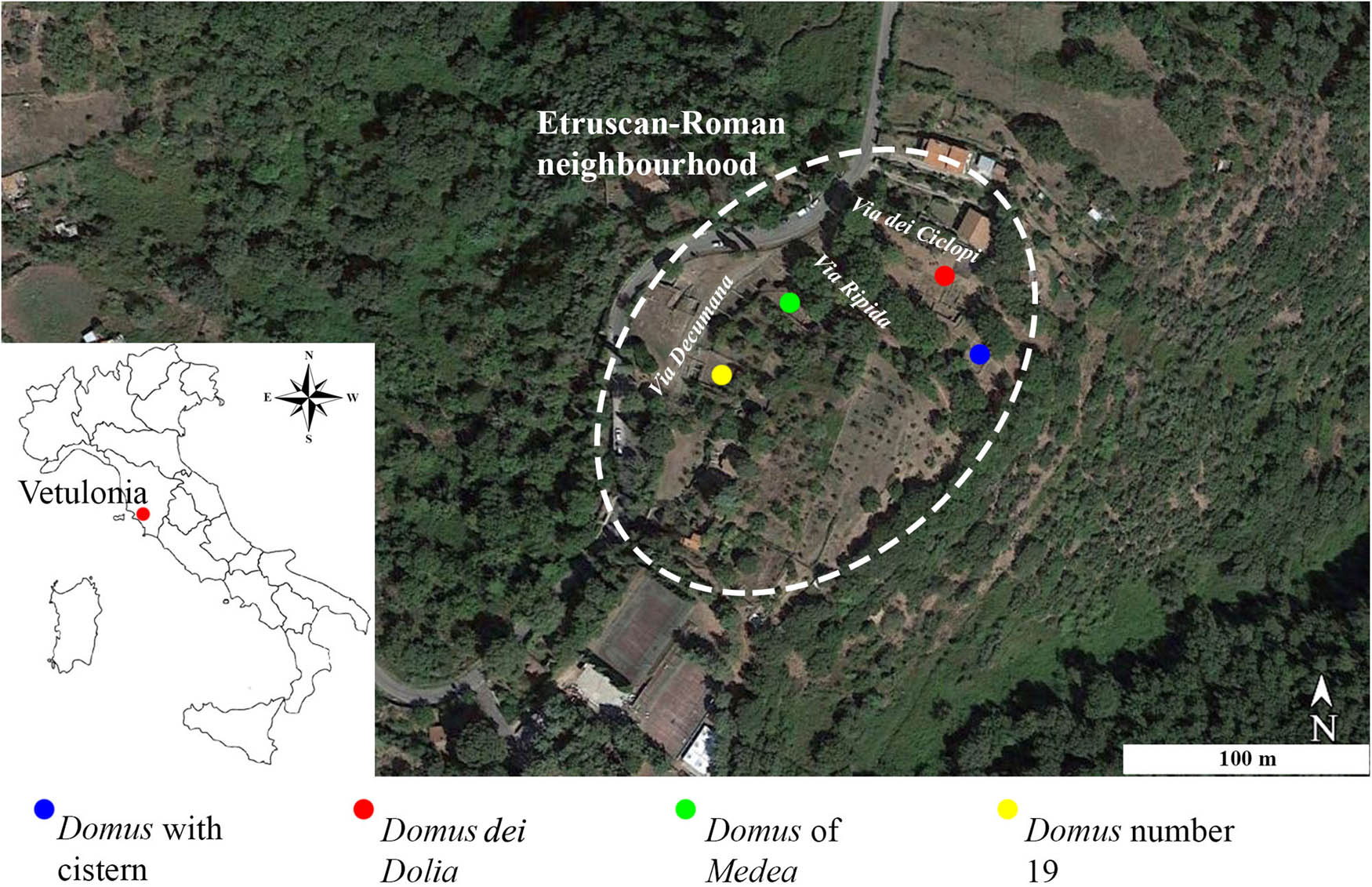

The city of Vetulonia is in central Italy, in the western side of the Italian peninsula in Southern Tuscany (Figure 1). During ancient times, the city overlooked a big navigable lagoon to the west (Colombi, 2018) and also controlled a vast territory to the north, including the so-called area of the Colline Metallifere, an important Italian mining district particularly abundant in ore natural resources (Bazzoni, Betti, Casini, Costantini, & Pagani, 2015). The most ancient Etruscan archaeological evidence goes back to the ninth–eleventh century BC, but it was between the eighth and the sixth century that Vetulonia gained importance, and it became one of the few important Etruscan city states that survived to Rome expansion until the second century BC. Nevertheless, during the first century BC, the city was involved in the Roman civil war, leading to its inexorable decline and destruction (Gregori, 1991; Semplici, 2015). The most ancient archaeological excavation at Vetulonia was carried out by Isidoro Falchi during the late nineteenth century, discovering the funerary area of the city (i.e. Villanovia phase of the Etruscan Culture, ninth–eighth century BC) in addition to the majestic tumulus tombs (Etruscan Orientalizing Period, eighth to beginning of the sixth century BC), and the Etrusco-Roman neighbourhood (Hellenistic – Late Republican periods, third–first centuries BC) of the ancient city in the area of Poggiarello Renzetti (Cygeilman, 2002).

Identification of the Domus dei Dolia within the Etruscan-Roman neighbourhood of Poggiarello Renzetti, Vetulonia, Italy.

Afterwards, since the middle of the twentieth century, new excavations were carried out by different scholars, bringing to light more evidence of the ancient Etruscan city of Vetulonia included in the Hellenistic (i.e. fourth–third centuries BC) and Late Republican (i.e. second–first centuries BC) periods (Cygielman, 2015; Rafanelli, 2015; Talocchini, 1981; da Vela, 2015). Just in 2009, in the Etrusco-Roman district discovered by Isidoro Falchi at Poggiarello Renzetti, the Domus dei Dolia was discovered (Agricoli, Rafanelli, & Carnevali, 2016).

The Domus is close to other residential Etruscan houses of the Hellenistic period such as the Domus n. 19, the Domus of Medea, and another Domus characterized by the presence of a vast atrium with impluvium and a large cistern (Figure 1). Consequently, the Hellenistic residential area of Poggiarello Renzetti represents the most important archaeological evidence of ancient Vetulonia, representing a period of prosperity and economic renaissance.

The results of the archaeological excavation evidenced that the Domus was destroyed by a fire, which probably also destroyed the whole neighbourhood (Cygeilman, 2016) during the Roman civil war of the first century BC. Besides, the preliminary study of pottery (i.e. black painted ware and Greek-Italic amphorae) supports this hypothesis, suggesting a chronological occupation of the house in a timeframe comprised between the third and the first century BC (Grassigli & Rafanelli, 2019; Rafanelli & Spiganti, 2019).

From the architectural point of view, the uncovered reality represents an important discovery in the field of Etruscan archaeology, as the archaeological structures are quite intact (Figure 2), and well-preserved dwellings with a high rise (i.e. 1.60 m high and 0.6 m thick) are still in place. Based on field observation, three different construction phases have been proposed by archaeologists and, until now (the excavation is still on-going), 12 different divisions of the Domus with a different function have been documented. The complete description of the Domus can be found elsewhere (Coradeschi et al., 2021; Grassigli & Rafanelli, 2019; Rafanelli & Spiganti, 2019).

Planimetry of the Domus dei Dolia, and the divisions brought to light between 2009 and 2015.

Different construction materials were employed to build the Domus dei Dolia. Perimetral and dividing walls were mostly constructed using locally available sandstone. Nevertheless, walls could also be constructed using stones (i.e. lower part of the wall) plus bricks or wattle and daub (i.e. higher part of the wall). These technological options have been widely attested in the Etruscan world (Amicone et al., 2020; Ceccarelli et al., 2020; Miller, 2015; Pizzirani, 2019), but they were prohibited and substituted by fired bricks in Roman territories after the first century BC (Spiganti, Trippetti, Spiganti, & Zoccoli, 2016). Wood was utilized for the construction of the room’s framing elements, for the doors, and may be for the internal support of wattle and daub (Coradeschi et al., 2021). Finally, roof tiles were used in the roof.

2.2 Geological Setting of the Area

The ancient city of Vetulonia is located on the western side of the Italian Peninsula, in the southern portion of the Tuscany region, roughly 15 km from the seacoast. It is positioned at an altitude of 320 m above sea level with the following coordinates: 42°51′34″N to 10°58′16″E. The geology of the area (Carmignani, Conti, Cornamusini, & Pirro, 2013) is the result of the collision between the African (i.e. Apulia microplate) and European (i.e. Briançonnais microplate) plates during the Tertiary. This event led to the rise of the Northern Apennines (Conti, Cornamusini, & Carmignani, 2020), and in Tuscany, it is possible to observe a complete nappe stack of it, being most geological unit completely exposed. In the area of interest (i.e. Tuscany southwest, Figure 3) the following units can be found: the metamorphic succession of the Tuscan domain, non-metamorphic succession of the Tuscan domain, the Sub-Ligurian domain, the Ligurian domains (i.e. internal and external), in addition to Neogene to Quaternary sedimentary successions. Of all these units derived by the Apulia microplate and the Thetys ocean realm (i.e. Ligurian domains), while the Sub-Ligurian domain represents a transitional domain between the oceanic and the Apulia continental crust. Neogene and quaternary intrusive and effusive acid/felsic volcanic rocks are also present close to the site.

Geological map of the area of Vetulonia where the archaeological site has been discovered. The geological map has been adapted after Carmignani et al. (2013).

3 Materials and Methods

3.1 Materials

The archaeological excavation of the Domus dei Dolia began in 2009 (it is still on-going), and the construction materials included in this study (Table 1) were recovered between 2009 and 2015. During this period, only the southern section of the Domus was excavated. Bricks were recovered inside division B, and only some of them were clearly visible during the excavation. In addition, bricks were not fired during the Etruscan period, so humidity, burial conditions, and rain affected their conservation and recovery. Nevertheless, in our case, the Domus was destroyed by a fire, and bricks were consequently partially fired (Spiganti et al., 2016), helping the preservation and recovery of some of them. Archaeological data indicated that they were utilized to complete the construction of a dividing wall made up of sandstones that separated division A from division B (Figure 4a and b). The preliminary macroscopic observation of the bricks suggested that the same raw material was probably exploited to produce them, and two samples from two different bricks were selected for analysis. The dimension of bricks could vary depending on preservation, and the registered dimensions were as follows: 20/26 cm long, 16/21 cm wide, and 11/12.5 cm thick (Pozzi, Giancarlo, Beltrame, & Coradeschi, 2016).

Archaeological samples included in this study, including typology, division of the Domus where the sample has been collected, year of recovery, and some sample characteristics

| Sample ref. | Roof tile typology | Room/function | Archaeological campaign | Paste colour |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VSC1 | Pan – Tegulae | G/storage room | 2015 | Buffy |

| VSC2 | Pan – Tegulae | H/semi open room with portico | 2015 | Buffy |

| VSC3 | Pan – Tegulae | G/storage room | 2015 | Red |

| VSC4 | Cover – imbrices | G/storage room | 2015 | Red |

| VSC5 | Cover – imbrices | G/storage room | 2015 | Red-brown |

| VSC6 | Pan – Tegulae | H/semi open room with portico | 2015 | Buffy |

| VSC7 | Pan – Tegulae | H/semi open room with portico | 2015 | Red |

| VSC8 | Pan – Tegulae | H/semi open room with portico | 2015 | Buffy |

| VSC9 | Pan – Tegulae | E/tablinum | 2013 | Red |

| VSC10 | Cover – imbrices | H/semi open room with portico | 2015 | Red |

| VSC11 | Cover – imbrices | H/semi open room with portico | 2015 | Red |

| VSC12 | Cover – imbrices | H/semi open room with portico | 2015 | Red |

| VSC13 | Cover – imbrices | H/semi open room with portico | 2015 | Red |

| VSC14 | Pan – Tegulae | E/tablinum | 2013 | Red |

| VSC15 | Pan – Tegulae | E/tablinum | 2013 | Brown |

| VSC16 | Pan – Tegulae | E/tablinum | 2013 | Buffy |

| VSC17 | Cover – imbrices | E/tablinum | 2013 | Red |

| VSC18 | Cover – imbrices | A/storage room | 2010 | Red-brown |

| VSC19 | Pan – Tegulae | A/storage room | 2010 | Buffy |

| VSC20 | Pan – Tegulae | A/storage room | 2010 | Buffy |

| VSC21 | Pan – Tegulae | C/triclinium | 2011 | Buffy |

| VSC22 | Pan – Tegulae | C/triclinium | 2011 | Red-brown |

| VSC23 | Brick | B/product processing area | 2009 | Red |

| VSC24 | Brick | B/product processing area | 2009 | Red |

(a) Room B, bricks and roof tiles can be observed lying on the top part of the archaeological deposit, (b) bricks from room B, (c) room C, a picture representing many roof tiles completely fragmented on the archaeological deposits with traces of burning.

Roof tiles were very abundant in all divisions, but few were almost intact. Most roof tiles were extremely fractured because of the roof’s collapse (Figure 4b and c). The best-preserved planar roof tile was 71.5 cm long, 52 cm wide, and 3.5 cm thick. The raised side border was 2–3 cm wide, the internal height was 4.3 cm, and the external height was 7.6 cm. In the case of semi-circular roof tiles, just partial fragments were recovered, and they were a maximum of 19.8 cm long and 17.7 cm wide, and the chord was 10 cm maximum (Pozzi et al., 2016). Unlike bricks, planar and semi-circular roof tiles differed in terms of paste colour, suggesting that more than one raw material was probably exploited in their production. In total, 14 pan and nine (9) cover roof tiles were selected from different divisions of the Domus, being representative of the different pastes observed during sampling.

3.2 Methods

Samples were analysed using optical microscopy (OM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and X-ray fluorescence (XRF). Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to evaluate XRF results.

3.2.1 OM

OM analysis was performed for all samples. To describe this section, minerals, rocks, and rock fragments were identified in all cases. Ceramic paste, porosity, and temper characteristics were described following the guidelines of Quinn (2013). Temper grain size was described using the Wentworth (1922) classification scale, while grain size distribution and temper abundance were evaluated by 2D image analysis using ImageJ software (Beltrame et al., 2020; Sitzia, Beltrame, & Mirão, 2022). A transmitted light petrographic microscope, model Leica DM-2500-P, equipped with an acquisition camera model Leica MC-170-HD was used for the ceramic thin section analysis. The HRX-01 HIROX microscope, equipped with a 5 MP sensor and HR-5000E lens at 0° inclination, was used to acquire high-resolution images of samples at 140× magnifications.

3.2.2 XRD

XRD analyses were developed on powdered samples. The equipment utilized was a Bruker AXS D8 Discover with the Da Vinci design, using a Cu Kα source and operating at 40 kV and 40 mA. Analyses were performed in the 3 to 75° 2θ, range, with a step of 0.05 2θ, and 1 second/step acquisition time by point. The interpretation of XRD patterns was performed using Diffract-EVA software with a PDF-2 mineralogical database (International Centre for Diffraction Data).

3.2.3 XRF and PCA

XRF was applied in all samples for the quantification of major oxides (SiO2, TiO2, Al2O3, Na2O, K2O, CaO, MgO, MnO, FeO, and P2O5) and some trace elements (Rb, Sr, Y, Zr, Nb, Th, U, and Mn), using an S2 Puma (Bruker) energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (Beltrame et al., 2019, 2021). Samples (1.2 g) were fused in a Claisse LeNeo heating chamber with the addition of a flux (Li‒Tetraborate, 12 g) to prepare fused beads (ratio sample/flux = 1/10). The software utilised for data acquisition and processing was Spectra Elements 2.0, which reported the final oxide/element concentrations and the instrumental statistical error associated with the measurement. The loss on ignition (LOI) was determined by calcining a 1 g dry sample in a muffle furnace for 1 h at 1,100°C. PCA was applied to interpret chemical analysis results (Swan & Sandilands, 1995) including LOI. PCA was developed using a correlation matrix, and a principal component (PC) was considered significant when the eigenvalue was higher than 1. The contribution of each variable (i.e. positive or negative loading) to a PC was assessed as follows. Considering that the sum of the squares of all loadings for an individual PC must equal one, we first calculated the loadings assuming all variables contributed equally to that PC. Afterwards, any variable having a higher loading than the calculated value (i.e. medium value) was considered an important contributor to that PC.

4 Results and Discussion

4.1 OM

Five different fabrics were identified after thin section analysis (Table 2, Figure 5).

Synthesis of samples subdivision based on fabrics

| Sample ref. | Roof tile typology | Room/function | Fabric |

|---|---|---|---|

| VSC1 | Pan | G/storage room | A |

| VSC2 | Pan | H/semi open room with portico | A |

| VSC3 | Pan | G/storage room | B |

| VSC4 | Cover | G/storage room | B |

| VSC5 | Cover | G/storage room | B |

| VSC6 | Pan | H/semi open room with portico | A |

| VSC7 | Pan | H/semi open room with portico | B |

| VSC8 | Pan | H/semi open room with portico | A |

| VSC9 | Pan | E/tablinum | A |

| VSC10 | Cover | H/semi open room with portico | B |

| VSC11 | Cover | H/semi open room with portico | E |

| VSC12 | Cover | H/semi open room with portico | E |

| VSC13 | Cover | H/semi open room with portico | E |

| VSC14 | Pan | E/tablinum | B |

| VSC15 | Pan | E/tablinum | C |

| VSC16 | Pan | E/tablinum | A |

| VSC17 | Cover | E/tablinum | B |

| VSC18 | Cover | A/storage room | B |

| VSC19 | Pan | A/storage room | A |

| VSC20 | Pan | A/storage room | A |

| VSC21 | Pan | C/t riclinium | A |

| VSC22 | Pan | C/t riclinium | B |

| VSC23 | Brick | B/product processing area | D |

| VSC24 | Brick | B/product processing area | D |

Fabric collected (25× magnification) at crossed polarized light. (a) Fabric A, (b) Fabric B, (c) Fabric C, (d) Fabric D, and (e) Fabric E.

Fabric A (Figure 5a). This fabric includes samples VSC-1/2/6/8/9/16/19/20/21, and they are pan roof tiles. In all cases, the ceramic paste is moderately homogeneous and buffy in colour. The colour of ceramic pastes suggests a high calcium content in the raw clay material employed to produce them. Nevertheless, this consideration will be tested/verified by mineralogical and chemical analysis in Sections 4.2 and 4.3. Porosity is abundant, and it is mainly composed of micro to macrochannels and vughs. Channels are generally weakly oriented to the outer surfaces of the fragments in thin sections. Temper (5 to 10%) is very poorly sorted in all cases, and elongated crystals are more abundant than equant ones. The degree of roundness varies from angular to sub-rounded. Grain size distribution is bimodal. Besides, two distinct grain size fractions could be clearly observed. The smaller fraction is mainly composed of sub-rounded/angular grains of coarse silt, while the coarse fraction is composed of very coarse sand to granule angular grains. From the mineralogical point of view, plagioclase feldspars and pyroxenes were dominant, with lower amounts of quartz, amphiboles (few), potassium-rich feldspar (rarely), and opaque minerals. Gabbroic rock fragments were very common. Shale, siltstone, and sandstone could also be rarely observed, in addition to some fragments of volcanic glass.

Fabric B (Figure 5b). This fabric includes samples VSC-3/4/5/7/10/14/17/18/22, and they are four pans and five cover roof tiles. In all cases, the ceramic paste is slightly homogeneous and red/brown in colour. The colour of ceramic pastes suggests high iron content in the raw clay material employed to produce them. Porosity is not very abundant, and it is mainly composed of micro to meso vesicles and vughs. Temper (5 to 20%) is very poorly sorted in all cases, with a similar concentration of elongated and equant crystals. Roundness varies from angular to sub-rounded. Grain size distribution is mostly bimodal. Besides, two distinct grain size fractions could be clearly observed with a different degree of roundness. The smaller fraction (i.e. more rounded) varies from coarse silt to very fine sand, while the coarse fraction varies from coarse sand to granule. From the mineralogical point of view, quartz, plagioclase, and pyroxene were dominant mineralogical phases compared to muscovite, potassium-rich feldspar, and amphibole minerals. Opaque minerals were also identified in thin sections. Unlike fabric A, shale, siltstone, and sandstone rock fragments were common in all cases, and gabbroic rock fragments were less represented.

Fabric C (Figure 5c). This fabric includes a sample VSC-15, and it is a pan roof tile. The ceramic paste is moderately homogeneous and brown in colour. Thus, similar to fabric B, the ceramic paste colour suggests high iron content in the raw clay material employed to produce it. Porosity is not very abundant, being mainly composed of micro to meso vesicles and vughs. Temper (20%) is very poorly sorted, predominating equant crystals. Roundness varies from angular to sub-rounded. Grain size distribution is bimodal, and two distinct grain size fractions could be clearly observed. The smaller fraction is composed of sub-rounded/angular grains of coarse silt, while the coarse fraction is composed of angular grains of coarse sand. From the mineralogical point of view, quartz, big crystals potassium-rich feldspar, and biotite mineralogical phases are dominant. Plagioclase feldspars (few), zircon (rare), and opaque minerals could also be observed. Unlike fabrics A and B, granitic rock fragments were common, but a few sandstone fragments were also observed.

Fabric D (Figure 5d). This fabric includes samples VSC-23/24, and they are two bricks. The ceramic paste is moderately homogeneous and red in colour. Thus, similar to fabrics B and C, the ceramic paste colour suggests high iron content in the raw clay material employed to produce them. Porosity is mainly composed of randomly oriented micro to macro vesicles, vughs, and channels. Temper (40–50%) is moderately sorted, with a clear predominance of equant crystals. Roundness varies from sub-rounded to rounded. Grain size distribution is unimodal in all cases, with the predominance of fine sand grains. From the mineralogical point of view, quartz, potassium-rich feldspar, and muscovite are the dominant mineralogical phases, in addition to plagioclase feldspars (few) and opaque minerals. Amongst rock fragments, shale, and sandstone fragments were very abundant.

Fabric E (Figure 5e). This fabric includes samples VSC-11/12/13, and they are semi-circular roof tiles. The ceramic paste is slightly homogeneous and red/brown in colour. Thus, similar to fabrics B, C, and D, the ceramic paste colour suggests high iron content in the raw clay material employed to produce them. Porosity is abundant, slightly alienated to samples margins in thin sections, and it is mainly composed of meso to mega vughs, channels, and planar voids. Temper (5–10%) is very poorly sorted, with a predominance of equant crystals. Roundness varies from angular to sub-rounded. Grain size distribution is bimodal, and two distinct grain size fractions could be clearly observed. The smaller fraction is composed of sub-rounded/angular grains of coarse silt, while the coarse fraction is mainly composed of sub-angular and angular grains of coarse sand. From the mineralogical point of view, quartz is the dominant mineralogical phase, with a lower amount of potassium-rich feldspar, plagioclase feldspars, amphiboles (few), pyroxenes, and opaque minerals. Shale, slate, sandstone, and quartzite were very common, and gabbroic rock fragments (rarely) were rarely identified.

Thin section evaluation evidenced a clear difference in roof tiles and bricks manufacturing technology. In the first case, fabrics A, B, C, and E were largely employed to produce roof tiles. Fabrics A and C were generally utilized to produce pan roof tiles, while fabric E was just utilized to produce cover roof tiles. On the contrary, fabric B could be utilized to produce both pan and cover roof tiles. Our observations suggest that in all cases, the raw material was partially treated, and a bigger inclusion could be added in a second moment. Besides, small and big grains do not generally sediment together, and the presence of sub-rounded inclusion in the smaller grain size fraction also points to a partial treatment of the raw material. Temper amount could change (5–20%) in this category of construction materials. Probably, it was not an important variable or, alternatively, a slightly different amount of tempering material could be added depending on the characteristics of the clayey material employed (loss of volume during drying and firing). This hypothesis would suggest that the clayey raw material employed could be different and heterogeneous for different fabrics.

In the case of bricks (Fabric D), the manufacturing technology employed was completely different. It seems that considering the amount of temper (40–50%), the raw material extracted was not treated at all or, alternatively, just the bigger inclusions were removed from the raw material. Inclusion grain size is quite uniform, and it might support this hypothesis. Maybe this was a specific technological option considering the raw material loss of volume and shrinkage during drying (Ceccarelli et al., 2020). Besides, as already stated in the introductory section, during the Etruscan period, bricks were unfired, and a significant amount of temper was probably needed to preserve the original shape of the brick during drying and to avoid shrinkage.

Regarding the origin of the raw material employed to produce roof tiles and bricks, the exploitation of three different raw materials sources is proposed considering sample characteristics and the geological setting of the area (Figure 3). The first raw material source is represented by fabrics A, B, and E. The colour of ceramic pastes (i.e. buffy, red, and red/brown) suggests that the characteristics of the clayey raw material employed could be slightly different between fabrics and that the sedimentary deposit exploited could be different or heterogeneous. Besides, the ceramic paste of CaO-rich raw materials normally became buffy after firing while, on the contrary, when CaO is not so abundant, it does not. This hypothesis will be verified by XRD and XRF analysis in Sections 4.2 and 4.3, respectively. Regarding inclusions (i.e. minerals and rock fragments), the identification of a similar mineralogical association (i.e. in all cases, mafic minerals such as plagioclase feldspars and pyroxenes were clearly identified in a thin section) suggests/indicates that a raw material with similar mafic inclusions was selected and exploited. The main difference between fabrics A, B, and E resides in the relative abundance of these minerals in sample ceramic pastes. On fabric A, mafic minerals are the dominant mineralogical phases. Conversely, from fabrics B to E, the presence of mafic minerals decreases, while the presence of mineral inclusion such as quartz, muscovite, and potassium-rich feldspars increases. Also, the identification of similar rock fragments points to an analogous interpretation. As in the previous case, mafic (i.e. gabbro rock fragments) and sedimentary (i.e. quartzite, shale, slate, and sandstone) rock fragments were observed in all cases. The presence of mafic rock fragments decreases from fabrics A to E, while the abundance of sedimentary rock fragments increases from fabrics A to E. Considering the geological setting of the area close to the archaeological site, optical microscopy results point to a compatibility with the non-metamorphic succession of the Internal Ligurian Unit (Figure 3) that outcrops in a radius of roughly 4–12 km north/north-east from the archaeological site. They are mainly composed of Jurassic ophiolites (Montanini, Travaglioli, Serri, Dostal, & Ricci, 2006) and their cretaceous sedimentary cover (Carmignani et al., 2013; Conti et al., 2020; Nirta, Pandelli, Principi, Bertini, & Cipriani, 2005). In particular, the sedimentary cover is made by heterogeneous shales (i.e. dark/grey shale, siliceous limestone, and fine-grained quartz arenite bed), including ophiolitic masses (i.e. olistoliths and sedimentary breccias) of variable dimension. Mafic minerals and rock fragments can only be found within this geological unit, and it is localized in the territory. Consequently, this material was selected and preferred (i.e. considering the number of samples included in these fabrics) to produce roof tiles, and the heterogeneity observed in fabrics A, B, and E reflects the heterogeneity of the selected deposit/s of the same geological formation.

In the case of fabric C, the minerals and rock fragments identified in thin sections (i.e. feldspars, biotite, quartz, zircon, and granite) point to compatibility with the Neogene and Quaternary acid/felsic magmatic outcrops, located at 6–8 km north-east of the archaeological site. In this case, the Gavorrano monzogranites (Musumeci, Mazzarini, Corti, Barsella, & Montanari, 2005) show a similar mineralogical association, suggesting that the alteration products of this geological formation were employed to produce the only fabric C sample. Also, in this case, the outcrop is extremely localized, and a similar mineralogy cannot be found elsewhere close to the archaeological site. Similar outcrops can only be found in the Elba, Giglio, and Montecristo Islands and north of the city of Piombino at roughly 50–60 km from the archaeological site (Carmignani et al., 2013; Conti et al., 2020).

Regarding fabric D (i.e. bricks), they are compatible with the outcrops of the non-metamorphic succession of the Tuscan domain, where the archaeological and the town of Vetulonia is located (Amendola et al., 2016; Cornamusini, Elter, & Sandrelli, 2002). Besides, the mineralogical association (i.e. quartz, feldspars, and muscovite) and the rock fragments (i.e. shale and sandstone) can be clearly correlated with this geological formation, indicating that bricks were probably produced in close proximity to the archaeological site.

Thus, our observations indicate that roof tiles were possibly not produced in place, and two different sets of raw materials were exploited. These raw materials could be found in a radius of roughly 12 km from the archaeological site. So, they were imported into the city. Considering that the Domus is not the only one within the archaeological area of Vetulonia, a massive production of roof tiles was required. Consequently, the selection of the geological deposit was likely based on factors such as distance, abundance, accessibility, space to process the raw material, fuel and water availability, and security. Differently, in the case of bricks, they were probably produced very close to the archaeological sites, using a third and completely different raw material. So, for bricks, the raw material was selected according to accessibility and local availability. The technology applied was also different. In the case of roof tiles, there was no distinction in the technology used to produce them, the typology was not an important variable and similar production criteria were employed in all cases. Differently, in the case of bricks, the amount of temper was an important issue, and it had to be high to avoid bricks shrinkage during drying to preserve the original shape. This technological option in brick manufacture has been very common (Nodarou, Frederick, & Hein, 2008) in the Mediterranean area since pre-history.

4.2 XRD

The mineralogical analysis of the samples verified optical microscopy observations, and it added new data to evaluate samples characteristics and the firing technology applied. Moreover, as already stated in previous sections, the Domus was destroyed by a fire, and roof tiles and bricks were exposed to a high temperature. Roof tiles were generally fired (Ceccarelli et al., 2020), but bricks were not (Pizzirani, 2019). So, it can be possible to understand to which extent the “destruction” event influenced the original mineralogy of the samples. Based on the results obtained, samples were grouped into five different XRD groups (Table 3), which reflect the subdivision proposed in Section 4.1.

XRD results

| SAMPLE | FABRIC | XRD group | Qz | Pl | Kfs | Prx | Amp | Ak-Gh | Cal | Hem | Anl | Bt | Ilt-Ms | Sme | Chl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VSC1 | A | 1 | XXX | XXX | XXX | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| VSC2 | A | 1 | XX | XXX | X | XXX | X | X | X | ||||||

| VSC3 | B | 2 | XXXX | XX | X | X | X | X | X | XX | |||||

| VSC4 | B | 2 | XXXX | XX | XX | X | X | X | |||||||

| VSC5 | B | 2 | XXXX | XX | XX | XX | X | TR | |||||||

| VSC6 | A | 1 | XX | XXX | X | XXX | XX | TR | X | ||||||

| VSC7 | B | 2 | XXXX | XXX | XX | XXX | X | X | X | ||||||

| VSC8 | A | 1 | XXX | XXX | XX | XXX | X | TR | XX | ||||||

| VSC9 | A | 1 | XX | XXX | X | XXX | XX | XX | TR | ||||||

| VSC10 | B | 2 | XXXX | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| VSC11 | E | 5 | XXXX | X | X | VS | TR | X | XX | ||||||

| VSC12 | E | 5 | XXXX | X | X | TR | TR | TR | X | X | |||||

| VSC13 | E | 5 | XXXX | X | X | TR | X | X | |||||||

| VSC14 | B | 2 | XXXX | X | XXX | XX | X | X | X | ||||||

| VSC15 | C | 3 | XXXX | X | XXX | X | XX | TR | |||||||

| VSC16 | A | 1 | XXX | XXX | VS | XXXX | TR | XX | |||||||

| VSC17 | B | 2 | XXXX | XX | X | XX | TR | X | X | ||||||

| VSC18 | B | 2 | XXXX | XX | X | XX | X | X | |||||||

| VSC19 | A | 1 | XXX | XXX | XX | XXX | X | X | X | X | |||||

| VSC20 | A | 1 | XX | XXX | XX | XXX | TR | X | X | ||||||

| VSC21 | A | 1 | XXX | XXX | X | XXX | X | X | X | ||||||

| VSC22 | B | 2 | XXXX | XX | XX | XX | X | X | |||||||

| VSC23 | D | 4 | XXXX | XX | X | XX | X | X | |||||||

| VSC24 | D | 4 | XXXX | XX | X | XX | TR | TR |

Qz, quartz; Pl, plagioclase; Kfs, potassium-rich feldspar; Amp, amphibole; Ak-Gh, akermanite-gehlenite; Cal, calcite; Hem, hematite; Anl, analcime; Bt, biotite; Ilt/Ms, illite-muscovite; Sme, smectite; Chl, chlorite; XXXX, very abundant; XXX, abundant; XX, moderate; X, not abundant; TR, traces.

XRD group 1. Fabric A samples are included in this group. Quartz, plagioclase feldspar, pyroxene, and akermanite/gehlenite mineralogical phases were always identified. On the contrary, potassium-rich feldspar, hematite, analcime, amphibole, and illite/muscovite mineralogical phases may or may not be present.

XRD group 2. Fabric B samples are included in this group. Quartz, plagioclase feldspar, potassium-rich feldspars, pyroxene, hematite, and illite/muscovite mineralogical phases were identified in all cases. On the contrary, calcite, and amphibole mineralogical phases may or may not be observed.

XRD group 3. Fabric C samples are included in this group. Quartz, plagioclase feldspars, potassium-rich feldspars, hematite, biotite, and illite/muscovite minerals were identified.

XRD group 4. Fabric D samples are included in this group. Quartz, plagioclase feldspar, potassium-rich feldspars, and illite/muscovite mineralogical phases were identified in all samples. Smectite and chlorite clay minerals were also identified.

XRD group 5. Fabric E samples are included in this group. Quartz, plagioclase feldspar, potassium-rich feldspars, pyroxene, and illite/muscovite mineralogical phases were identified in all cases, while hematite, calcite, and amphibole may or may not be observed.

As observed during optical microscopy analysis, XRD groups 1, 2, and 5 show a slightly different mineralogy. In XRD group 1, plagioclase feldspars and pyroxenes were observed in thin sections, but akermanite/gehlenite (i.e. sorosilicate) minerals were not. Considering ceramic pastes colour (i.e. buffy), the identification of sorosilicate minerals on XRD patterns strongly suggests that plagioclase feldspars (i.e. tectosilicate) and pyroxenes (i.e. inosilicates) also formed during burning within the ceramic paste. Besides, when the carbonate component of the original raw material is significant, high-temperature calcium/magnesium-rich mineralogical phases nucleate at 800°C (Beltrame et al., 2021; Heimann & Maggetti, 2019; Trinidade, Dias, Coroado, & Rocha, 2009). So, plagioclase feldspars and pyroxenes were included in the tempering material, but they also formed in the ceramic paste in addition to akermanite/gehlenite. The same reasoning is not valid in the case of XRD groups 2 and 5, as akermanite/gehlenite was not identified in XRD patterns, and a difference in the carbonate component within the raw material exploited can be assumed.

Moreover, considering the same XRD groups, the semi-quantification of quartz, plagioclase feldspar, and pyroxene mineralogical phases clearly change. Quartz abundance increases in XRD groups 2 and 5, while the plagioclase and pyroxene representativity decrease accordingly. These results support the observation developed in the case of XRD group 1, and the interpretation proposed in the optical microscopy section. These observations indicate that the original raw materials employed to produce XRD groups 1, 2, and 5 contained similar mineralogical species (i.e. as inclusion), but on the clayey fraction, the carbonate component could vary. Consequently, XRD patterns reflect the heterogeneity of the original geological formation exploited in their production.

For XRD groups 3 and 4, results corroborate optical microscopy observation.

Regarding firing technology, bricks and roof tile are two different classes of construction materials, and they were produced using a different technology (Bonetto, 2019; Ceccarelli et al., 2020; Pizzirani, 2019). So, different considerations can be made after evaluating XRD results to determine sample's thermal history. Besides, specific mineralogical phases might disappear or nucleate when a clayey raw material is fired. Phyllosilicates and carbonate disappear during firing depending on the maximum firing temperature attained. Illite/muscovite disappear above 950/1,000°C, smectites at 500°C, while chlorite dehydroxylation occurs around 650°C (Beltrame et al., 2020; Maritan, Nodari, Mazzoli, Milano, & Russo, 2006; Trinidade et al., 2009). Between 700 and 800°C, CO2 is removed from carbonates, and free lime can combine with melted phyllosilicates in the formation of new calcium-rich mineralogical phases (Fabbri, Gualtieri, & Shoval, 2014; Trinidade et al., 2009), including plagioclase feldspars, pyroxenes, and akermanite/gehlenite. This reaction starts at 800°C (Heimann & Maggetti, 2014, 2019; Noll & Heimann, 2016; Trinidade et al., 2009), and it can continue until a higher temperature (i.e. more than 1,000°C). Hematite nucleates at 750°C (Beltrame et al., 2020).

Thus, the identification of clay minerals on bricks (i.e. XRD group 4) indicates that the fire that destroyed the Domus was not sufficiently strong for the clay minerals to collapse and disappear from XRD patterns. Besides, bricks were generally unfired, and the identification of clay minerals points to this interpretation. In the case of roof tiles, considering XRD results, the fire did not influence the original mineralogy because the fire temperature was too low. Consequently, the firing technology applied can be established in the case of roof tiles. Regarding XRD group 1, the firing temperature was higher than 800°C and up to 1,000°C, considering that illite/muscovite was not detected in two different samples. Differently, XRD groups 2, 3, and 5 samples were probably fired between 750 and 950°C. Besides, hematite and illite/muscovite were always detected in the analysed samples.

4.3 XRF and PCA

The chemical analysis result table is presented in a separate annexed file. The statistical treatment of sample's chemical composition by PCA extracted five different PCs, and they describe 87.43% of the total variance (Table 4). The first two PCs were the most significant, representing 58.57% of the total variance.

Descriptive table with eigenvalues and percentage of variance of the extracted PCs

| PC | Eigenvalue | Percentage of variance (%) | Cumulative (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7.42 | 41.24 | 41.24 |

| 2 | 3.12 | 17.33 | 58.57 |

| 3 | 2.48 | 13.80 | 72.36 |

| 4 | 1.57 | 8.74 | 81.10 |

| 5 | 1.14 | 6.33 | 87.43 |

PCs 1 and 2 have different loadings (Table 5). In the case of PC1, the most important were represented by K2O, TiO2, Rb, Y, and Zr (i.e. positive), and Na2O, CaO, MgO, and Sr (i.e. negative). They describe the abundance of these oxides/elements inside the raw material exploited. K2O and Rb can be hosted both by tectosilicates (i.e. feldspars) and by phyllosilicates (i.e. illite/muscovite, biotite). They were both identified during optical microscopy (as lithoclasts or individual minerals) and XRD analysis. Titanium oxide, yttrium, and zircon chemical elements are normally hosted by different accessory minerals. Amongst them, oxides (i.e. ilmenite, rutile, anatase) or nesosilicates (i.e. zircon) can be mentioned. These oxides/elements can be present in the finer grain size fraction of a sediment, sedimentary, and felsic/acid rocks. CaO, MgO, and Sr might represent samples carbonate component, but these oxides (i.e. including Na2O)/chemical elements can also be hosted by some mafic minerals, such as tectosilicates and inosilicates (i.e. plagioclase feldspars, pyroxenes, and amphiboles). So, PC1 describes the variation of the sedimentary/felsic vs the carbonate/mafic components inside the analysed samples, and these characteristics are widely discussed in Sections 4.1 and 4.2.

Loading values of PC1 and PC2 for each oxide, chemical element, and LOI. Bold values represent significant PC1 and PC2 loadings

| Variables | Loadings of PC1 | Loadings of PC2 |

|---|---|---|

| N2O | −0.25 | −0.18 |

| MgO | −0.32 | 0.14 |

| Al2O3 | 0.02 | 0.4 |

| SiO2 | 0.2 | −0.44 |

| P2O5 | 0.16 | 0.31 |

| K2O | 0.3 | −0.14 |

| CaO | −0.3 | 0.1 |

| TiO2 | 0.29 | 0.13 |

| Fe2O3 | 0.22 | 0.36 |

| Rb | 0.29 | −0.08 |

| Sr | −0.27 | 0.1 |

| Y | 0.31 | 0.01 |

| Zr | 0.29 | −0.17 |

| Nb | 0.23 | 0.21 |

| Th | 0.23 | 0.17 |

| U | −0.08 | 0.28 |

| Mn | 0.01 | 0.09 |

| LOI | 0.05 | 0.34 |

Regarding PC2, significant positive loading has been observed in the case of Al2O3, P2O5, Fe2O3, U, and LOI, contrasted by a negative loading of SiO2 (Table 4). While the variability of uranium and phosphorous is not clear, Al2O3, Fe2O3, and LOI give important indications. Aluminium and iron oxides are important components in phyllosilicates, while LOI represents hydrous minerals (i.e. mainly phyllosilicates and amphiboles). SiO2 (i.e. silica) can be included inside different mineralogical phases, and quartz (i.e. tectosilicates) is probably the most significant in this case. So, PC2 describes the amount of hydrous minerals (i.e. mainly phyllosilicates) compared to the amount of quartz (i.e. tectosilicates) inside the analysed samples. Thus, PC2 describes the clay to temper ratio. Nevertheless, in our case, the clay-to-temper ratio was not established, and only an estimation of temper by image analysis was included in the optical microscopy section.

Thus, the biplot (Figure 6) clearly summarizes sample subdivision based on their characteristics, and by combining OM and XRD results, the following observation can be made on fabrics:

The chemical composition of fabrics A, B, and E (i.e. XRD groups 1, 2, and 5) samples is explained by the variation of the carbonate component inside the ceramic paste, the variation of mafic and sedimentary minerals/rock fragments, and the clay-to-temper ratio.

Fabric A (i.e. XRD group 1) samples are rather uniform in chemical composition, and the carbonate/mafic component was extremely important in this case.

Fabric B (i.e. XRD group 2) samples show stronger variability along the PC2 axe. Besides, temper evaluation by 2D image analysis also shows the biggest temper concentration range (i.e. 5–20%). Moreover, the importance of the carbonate/mafic components decreases when compared to fabric A samples.

Fabric E (i.e. XRD group 5) samples are rather uniform in chemical composition, and the abundance of clay, sedimentary minerals, and rock fragments were important components in this case.

The chemical composition of fabric C (i.e. XRD group 3) samples is explained by the abundance of felsic mineral and rock fragments. Besides, quartz, biotite, and potassium-rich feldspars were important mineralogical phases, as evidenced by optical microscopy and XRD results. Also, the zircon mineral was an important component of the raw material exploited.

The chemical composition of fabric D (i.e. XRD group 4) samples is explained by the abundance of quartz and sedimentary rock fragments and minerals. As evidenced during optical microscopy observation, this fabric was extremely abundant in temper.

Bi-plot of PC1 and PC2. Blue axes represent PC1 and PC2 loadings for all variables presented in Table 4, while black axes represent sample scores for PC1 and PC2.

5 Conclusions

The archaeological and archaeometrical study evidenced that construction materials were presumably manufactured close to the archaeological site. Roof tiles were most probably produced within 4–12 km from the Domus, and the exploitation of two different raw material sources has been proposed. In both cases, the raw material was partially treated, temper could be added in a second moment, and they were fired. Considering that the Domus dei Dolia was not the only civil construction in the ancient Etruscan city of Vetulonia, it is supposed that a big production of roof tiles was needed for the ancient city. In any case, production sites (i.e. kilns) were never documented close to the archaeological area, but our study suggests that productive areas could be located close to the geological formations exploited. Seemingly, the location could be selected considering the distance from the raw material source, raw material abundance, accessibility, space to process the raw material, water, fuel to fire roof tiles, and security (i.e. in the case of a fire). Maybe, all (or some) of these factors did not favour the utilization of fabric C to produce roof tiles. Conversely, bricks could be produced very close to the archaeological site using specific criteria; the amount of temper was an important variable, and they were not fired. So, security was not a problem, and the selection of the raw material sources was just based on factors such as availability and accessibility. To conclude, this study added new information regarding the technology employed by the Etruscan of Vetulonia in producing roof tiles and bricks and suggested a production organization model.

Abbreviations

- VSC

-

Vetulonia Scavi

- PCA

-

principal component analysis

- PC

-

principal component

- Qz

-

Quartz

- Pl

-

Plagioclase

- Kfs

-

potassium rich feldspar

- Amp

-

amphibole

- Ak-Gh

-

akermanite–gehlenite

- Cal

-

calcite

- Hem

-

hematite

- Anl

-

analcime

- Bt

-

biotite

- Ilt/Ms

-

illite-muscovite

- Sme

-

smectite

- Chl

-

chlorite

- XXXX

-

very abundant

- XXX

-

abundant

- XX

-

moderate

- X

-

not abundant

- TR

-

traces

- LOI

-

loss on ignition

Acknowledgments

The corresponding author wish to acknowledge the Municipality of Castiglione della Pescaia (Italy), the Isidoro Falchi Civic Archaeological Museum (Italy), the HERCULES Laboratory funded by the “Fundação para Ciência e Tecnologia” (project codes: UIDB/04449/2020 and UIDP/04449/2020), and the China-Portugal Joint Laboratory of Cultural Heritage Conservation Science supported by the Belt and Road Initiative – National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFE0200100).

-

Funding information: This work was partly funded by the Municipality of Castiglione della Pescaia, Italy. Laboratory analyses were developed in the framework of the Hercules Laboratory projects funded by the Portuguese “Fundação para Ciência e Tecnologia” (project codes: UIDB/04449/2020 and UIDP/04449/2020).

-

Author contributions: Massimo Beltrame – Ginevra Coradeschi – José Mirão: funding acquisition, methodology, conceptualization, archaeometric analysis, data interpretation, data validation, writing first draft, review, editing. Simona Rafanelli – Costanza Quaratesi: archaeological excavation, archaeological excavation data preparation, archaeological materials collection and description.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The complete XRF datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the form of supplementary material.

References

Agricoli, G., Rafanelli, S., & Carnevali, S. (2016). Vetulonia. La Domus dei Dolia. Arcidosso, Italy: Effigi.Search in Google Scholar

Amendola, U., Perri, F., Critelli, S., Monaco, P., Cirilli, S., Trecci, T., & Rettori, R. (2016). Composition and provenance of the Macigno Formation (Late Oligocene-Early Miocene) in the Trasimeno Lake area (northern Apennines). Marine and Petroleum Geology, 69, 146–167. doi: 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2015.10.019.Search in Google Scholar

Amicone, S., Croce, E., Castellano, L., & Vezzoli, G. (2020). Building Forcello: Etruscan wattle‐and‐daub technique in the Po Plain (Bagnolo San Vito, Mantua, northern Italy). Archaeometry, 62(3), 521–537. doi: 10.1111/arcm.12535.Search in Google Scholar

Ammerman, A. J., Iliopoulos, I., Bondioli, F., Filippi, D., Hilditch, J., Manfredini, A., … Winter, N. A. (2008). The clay beds in the Velabrum and the earliest tiles in Rome. Journal of Roman Archaeology, 21, 7–30. doi: 10.1017/S1047759400004359.Search in Google Scholar

Balassone, G., Mercurio, M., Germinario, C., Grifa, C., Villa, I. M., Di Maio, G., … Langella, A. (2018). Multi-analytical characterization and provenance identification of protohistoric metallic artefacts from Picentia-Pontecagnano and the Sarno valley sites, Campania, Italy. Measurement, 128, 104–118. doi: 10.1016/j.measurement.2018.06.019.Search in Google Scholar

Bazzoni, C., Betti, C., Casini, A., Costantini, A., & Pagani, G. (2015). Minerali: Bellezze della natura nel parco delle Colline Metallifere – Tuscan Mining Geopark. In A. Costantini & G. Pagani (Eds.), Ospedaletto – Pisa: Pacini Editore Spa.Search in Google Scholar

Beltrame, M., Liberato, M., Mirão, J., Santos, H., Barrulas, P., Branco, F., … Schiavon, N. (2019). Islamic and post Islamic ceramics from the town of Santarém (Portugal): The continuity of ceramic technology in a transforming society. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 23, 910–928. doi: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2018.11.029.Search in Google Scholar

Beltrame, M., Sitzia, F., Arruda, A. M., Barrulas, P., Barata, F. T., & Mirão, J. (2021). The Islamic ceramic of the Santarém Alcaçova: Raw materials, technology, and trade. Archaeometry, 63(6), 1157–1177. doi: 10.1111/arcm.12671.Search in Google Scholar

Beltrame, M., Sitzia, F., Liberato, M., Santos, H., Barata, F. T., Columbu, S., & Mirão, J. (2020). Comparative pottery technology between the Middle Ages and Modern times (Santarém, Portugal). Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 12(7), 130. doi: 10.1007/s12520-020-01053-x.Search in Google Scholar

Bonetto, J. (2019). Diffusione ed uso del mattone cotto nell Cisalpina romana tra ellenizazzione e romanizazzione. In J. Bonetto, E. Bukowiecki, & R. Volpe (Eds.), Alle origini del laterizio romano. Nascita e diffusione del mattone cotto nel Mediterraneo tra IV e I secolo a.C. Roma: Edizioni Quasar.Search in Google Scholar

Bruni, S. (2012). Le analisi chimiche nello studio dei materiali ceramici. In M. Bonghi Jovino & G. Bagnasco Gianni (Eds.), Tarquinia. Il Santuario dell’Ara della Regina. I templi Arcaici (pp. 421–423). Roma: L’Erma di Bretschneider.Search in Google Scholar

Bruni, S., Bagnasco Gianni, G., & Ciarati, F. (2001). Spectroscopic characterization of Etruscan depurata and impasto pottery from the excavation at Pian di Civita in Tarquinia (Italy): A comparison with local clay. In I. C. Druc (Ed.), Archaeology and clay (Vol. 942, pp. 27–38). Oxford: Bar Internationa Series.Search in Google Scholar

Camporeale, G. (1969). I Commerci di Vetulonia in Età Orientalizzante. Firenze, Italy: Sansone Editore.Search in Google Scholar

Camporeale, G. (2016). The Etruscans and the Mediterranean. In S. Bell & A. A. Carpino (Eds.), A Companion to the Etruscans (pp. 67–86). Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley. doi: 10.1002/9781118354933.ch6.Search in Google Scholar

Carmignani, L., Conti, P., Cornamusini, G., & Pirro, A. (2013). Geological map of Tuscany (Italy). Journal of Maps, 9(4), 487–497. doi: 10.1080/17445647.2013.820154.Search in Google Scholar

Ceccarelli, L. (2016). The Romanization of Etruria. In S. Bell & A. A. Carpino (Eds.), A companion to the Etruscans (pp. 28–40). Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley. doi: 10.1002/9781118354933.ch3.Search in Google Scholar

Ceccarelli, L., Moletti, C., Bellotto, M., Dotelli, G., & Stoddart, S. (2020). Compositional characterization of Etruscan earthen architecture and ceramic production. Archaeometry, 62(6), 1130–1144. doi: 10.1111/arcm.12582.Search in Google Scholar

Ciarati, F., Bruni, S., & Fermo, P. (2001). Sezione tecnologica. In G. Bonghi Jovino, G. Bagnasco, & S. Businaro (Eds.), Tarquinia. Scavi sistematici dell’abitato.Campagne 1982–1988. I materiali (Vol. 2, pp. 525–537). Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider.Search in Google Scholar

Colombi, C. (2018). Castiglione della Pescaia (Grosseto), Italien. Auf der Suche nach den Häfen der etruskischen Stadt Vetulonia. Die Arbeiten der Jahre 2016 bis 2018. E-Forschungsberichte, 2, 79–85. doi: 10.34780/c1f9-2c9f.Search in Google Scholar

Conti, P., Cornamusini, G., & Carmignani, L. (2020). An outline of the geology of the northern Apennines (Italy), with geological map at 1:250,000 scale. Italian Journal of Geosciences, 139(2), 149–194. doi: 10.3301/IJG.2019.25.Search in Google Scholar

Coradeschi, G., Beltrame, M., Rafanelli, S., Quaratesi, C., Sadori, L., & Barrocas Dias, C. (2021). The wooden roof framing elements, furniture and furnishing of the Etruscan Domus of the Dolia of Vetulonia (Southern Tuscany, Italy). Heritage, 4(3), 1938–1961. doi: 10.3390/heritage4030110.Search in Google Scholar

Cornamusini, G., Elter, F., & Sandrelli, F. (2002). The Corsica-Sardinia Massif as source area for the early Northern Apennines foredeep system: Evidence from debris flows in the “Macigno costiero” (Late Oligocene, Italy). International Journal of Earth Sciences, 91(2), 280–290. doi: 10.1007/s005310100212.Search in Google Scholar

Cristofani, M. (2000). Gli Etruschi. Una nuova immagine. Firenze, Italy: Giunti Editore.Search in Google Scholar

Cristofani, M., & Martelli, M. (1983). L’oro degli Etruschi. Novara, Italy: De Agostini Editore.Search in Google Scholar

Cygeilman, M. (2002). Vetulonia Museo Civico Archeologico “Isidoro Falchi” Guida. Firenze, Italy: Arti Grafiche Nencini.Search in Google Scholar

Cygeilman, M. (2016). La città antica di Vetulonia. Il quartiere di Poggiarello Renzetti. In S. Rafanelli, G. Agricoli, & S. Carnevali (Eds.), Vetulonia. La Domus dei Dolia: Vol. I (Archeologia Itinera, pp. 11–14). Arcidosso, Italy: Effigi.Search in Google Scholar

Cygielman, M. (2015). Medea a Vetulonia. In Il Museo Civico Archeologico Isidoro Falchi di Vetulonia. Rome: Edizioni Quasar.Search in Google Scholar

Edlund-Berry, I. (2011). Etruscan architecture. In Classics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/obo/9780195389661-0121.Search in Google Scholar

Fabbri, B., Gualtieri, S., & Shoval, S. (2014). The presence of calcite in archeological ceramics. Journal of the European Ceramic Society, 34(7), 1899–1911. doi: 10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2014.01.007.Search in Google Scholar

Fermo, P., Cariati, F., Ballabio, D., Consonni, V., & Bagnasco Gianni, G. (2004). Classification of ancient Etruscan ceramics using statistical multivariate analysis of data. Applied Physics A, 79(2), 299–307. doi: 10.1007/s00339-004-2520-6.Search in Google Scholar

Ganio, M., MacLennan, D., Svoboda, M., Lyons, C., & Trentelman, K. (2021). Portrait of an Etruscan Athletic Official: A multi-analytical study of a painted terracotta wall panel. Heritage, 4(4), 4596–4608. doi: 10.3390/heritage4040253.Search in Google Scholar

Gliozzo, E., Comini, A., Cherubini, A., Ciacci, A., Moroni, A., & Memmi, I. T. (2011). Ceramic production and metal working at the Trebbio archaeological site (Sansepolcro, Arezzo, Italy). In Proceedings of the 37th International Symposium on Archaeometry, 13th–16th May 2008, Siena, Italy (pp. 61–69). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-14678-7_9.Search in Google Scholar

Gliozzo, E., Kirkman, I. W., Pantos, E., & Turbanti, I. M. (2004). Black gloss pottery: Production sites and technology in Northern Etruria, Part II: Gloss technology. Archaeometry, 46(2), 227–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4754.2004.00154.x.Search in Google Scholar

Grassigli, G. L., & Rafanelli, S. (2019). La Domus “Dei Dolia” nel quartiere di Poggiarello Renzetti a Vetulonia (GR). Bollettino Di Archeologia On-Line, X(1–2), 169–191.Search in Google Scholar

Gregori, D. (1991). Una bottega vetuloniese di buccheri e di impasti orientalizzanti decorati a stampiglia. In F. Paoli & F. Nicosia (Eds.), Studi e materiali. Scienze dell’antichità in Toscana: Vol. VI (pp. 64–81). Firenze: Regione Toscana – L’Erma di Bretschneider.Search in Google Scholar

Harrison, A. P., Cattani, I., & Turfa, J. M. (2010). Metallurgy, environmental pollution and the decline of Etruscan civilisation. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 17(1), 165–180. doi: 10.1007/s11356-009-0141-5.Search in Google Scholar

Heimann, R. B., & Maggetti, M. (2014). Ancient and historical ceramics. Materials, technology, art and culinary tradition. Stuttgrat: Schweizerbart Science Pubblisher.Search in Google Scholar

Heimann, R. B., & Maggetti, M. (2019). The struggle between thermodynamics and kinetics: Phase evolution of ancient and historical ceramics. European Mineralogical Union Notes in Mineralogy, 20, 233–281. doi: 10.1180/EMU-notes.20.6.Search in Google Scholar

Leighton, R. (2013). Urbanization in Southern Etruria from the tenth to the sixth century BC: The origin and growth of major centres. In J. MacIntosh Turfa (Ed.), The Etruscan world (pp. 134–150). London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Longoni, M., Calore, N., Marzullo, M., Teseo, D., Duranti, V., Bagnasco Gianni, G., & Bruni, S. (2023). Bucchero ware from the Etruscan town of Tarquinia (Italy): A study of the production site and technology through spectroscopic techniques and multivariate data analysis. Ceramics, 6(1), 584–599. doi: 10.3390/ceramics6010035.Search in Google Scholar

Lulof, P. S. (2014). Terracotta architectural sculpture in classical archaeology. In Encyclopedia of global archaeology (pp. 7273–7278). New York, NY: Springer New York. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-0465-2_1440.Search in Google Scholar

Magny, M., de Beaulieu, J.-L., Drescher-Schneider, R., Vannière, B., Walter-Simonnet, A.-V., Miras, Y., … Leroux, A. (2007). Holocene climate changes in the central Mediterranean as recorded by lake-level fluctuations at Lake Accesa (Tuscany, Italy). Quaternary Science Reviews, 26(13–14), 1736–1758. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2007.04.014.Search in Google Scholar

Maritan, L. (2004). Archaeometric study of Etruscan-Padan type pottery from the Veneto region: Petrographic, mineralogical and geochemical-physical characterisation. European Journal of Mineralogy, 16(2), 297–307. doi: 10.1127/0935-1221/2004/0016-0297.Search in Google Scholar

Maritan, L., Nodari, L., Mazzoli, C., Milano, A., & Russo, U. (2006). Influence of firing conditions on ceramic products: Experimental study on clay rich in organic matter. Applied Clay Science, 31(1–2), 1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.clay.2005.08.007.Search in Google Scholar

Meyers, G. E., Jackson, L. M., & Galloway, J. (2010). The production and usage of non-decorated Etruscan roof-tiles, based on a case study at Poggio Colla. Journal of Roman Archaeology, 23, 303–319. doi: 10.1017/S1047759400002415.Search in Google Scholar

Miller, P. (2015). Continuity and change in Etruscan domestic architecture: A study of building techniques and materials from 800–500 BC. (PhD thesis). University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.Search in Google Scholar

Montanini, A., Travaglioli, M., Serri, G., Dostal, J., & Ricci, C. A. (2006). Petrology of gabbroic to plagiogranitic rocks from southern Tuscany (Italy): Evidence for magmatic differentiation in an ophiolitic sequence. Ofioliti, 31(2), 55–69.Search in Google Scholar

Musumeci, G., Mazzarini, F., Corti, G., Barsella, M., & Montanari, D. (2005). Magma emplacement in a thrust ramp anticline: The Gavorrano Granite (northern Apennines, Italy). Tectonics, 24(6), 1–17. doi: 10.1029/2005TC001801.Search in Google Scholar

Neil, S. (2016). Materializing the Etruscans. In Sinclair Bell & A. A. Carpino (Eds.), A companion to the Etruscans (pp. 15–27). Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley. doi: 10.1002/9781118354933.ch2.Search in Google Scholar

Nestler, G., & Formigli, E. (2013). Granulazione Etrusca. Un’antica arte Orafa. Poggibonsi, Siena, Italy: Arti Grafiche Nencini.Search in Google Scholar

Nirta, G., Pandelli, E., Principi, G., Bertini, G., & Cipriani, N. (2005). The Ligurian unit of Southern Tuscany. Bollettino Della Società Geologica Italiana, 3, 29–54.Search in Google Scholar

Nodari, L., Maritan, L., Mazzoli, C., & Russo, U. (2004). Sandwich structures in the Etruscan-Padan type pottery. Applied Clay Science, 27(1–2), 119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.clay.2004.03.003.Search in Google Scholar

Nodarou, E., Frederick, C., & Hein, A. (2008). Another (mud)brick in the wall: Scientific analysis of Bronze Age earthen construction materials from East Crete. Journal of Archaeological Science, 35(11), 2997–3015. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2008.06.014.Search in Google Scholar

Noll, W., & Heimann, R. B. (2016). Ancient old world pottery. Materials, technology, and decoration. Stuttgrat, Germany: E. Schweizerbart’Sche Varlagsbuchhandlung Pubblisher.Search in Google Scholar

Pizzirani, C. (2019). Tecniche costruttive nell’edilizia domestica etrusca tra il VI e IV secolo a.C. In J. Bonetto, E. Bukowiecki, & R. Volpe (Eds.), Alle origini del latterizzio romano. Nascita e diffusione del mattone cotto nel Mediterraneo tra il IV e I secolo a.C. (pp. 335–344). Roma: Edizioni Quasar.Search in Google Scholar

Pozzi, S., Giancarlo, A., Beltrame, M., & Coradeschi, G. (2016). Catalogo. In S. Rafanelli (Ed.), Bentornati a Casa. La Domus dei Dolia riapre le porte dopo duemila anni (pp. 56–71). Monteriggioni, Siena: Ara Edizioni.Search in Google Scholar

Quinn, P. S. (2013). Ceramic petrography the interpretation of archaeological pottery & related artefacts in thin section. Summertown, Oxford, UK: Archaeopress.10.2307/j.ctv1jk0jf4Search in Google Scholar

Rafanelli, S. (2015). Le mura di Vetulonia. In Il museo Civico Archeologico Isidoro Falchi di Vetulonia (pp. 20–21). Arcidosso, Italy: Effigi.Search in Google Scholar

Rafanelli, S., Moita, P., Mirão, J., Carvalho, A., Braga, P., Vicente, R., … Coradeschi, G. (2018). Etruscan render mortars from Domus dei Dolia (Vetulonia, Italy). In Conserving cultural heritage (pp. 141–143). London, UK: CRC Press, Taylor and Francis group. doi: 10.1201/9781315158648-36.Search in Google Scholar

Rafanelli, S., & Spiganti, S. (2019). La città di Vetulonia in età ellenistica. Nuovi dati sul circuito murario urbano e sulla nuova Domus dei Dolia. In L. Attenni (Ed.), Le mura poligonali. Atti del Sesto Seminario con una sezione sul Museo Civico di Alatri (pp. 123–143). Napoli: Valtrend Editore.Search in Google Scholar

Roos, P., & Wikander, O. (1986). Architettura Etrusca nel Viterbese. Ricerche svedesi a San Giovanale e Acquarossa 1956–1986 (De Luca Editore). Roma: De luca editore.Search in Google Scholar

Sadori, L., Mercuri, A. M., & Mariotti Lippi, M. (2010). Reconstructing past cultural landscape and human impact using pollen and plant macroremains. Plant Biosystems – An International Journal Dealing with All Aspects of Plant Biology, 144(4), 940–951. doi: 10.1080/11263504.2010.491982.Search in Google Scholar

Saviano, G., Drago, L., Felli, F., & Violo, M. (2002). Architectural decorations, ceramics and terracotta from Veii (Etruria): A preliminary study. Periodico Di Mineralogia, 71, 203–215.Search in Google Scholar

Semplici, A. (2015). Il Museo Civico Archeologico Isidoro Falchi di Vetulonia (Effigi). Arcidosso, Italy: Effigi.Search in Google Scholar

Sitzia, F., Beltrame, M., & Mirão, J. (2022). The particle-size distribution of concrete and mortar aggregates by image analysis. Journal of Building Pathology and Rehabilitation, 7(74), 1–17. doi: 10.1007/s41024-022-00214-w.Search in Google Scholar

Spiganti, F., Trippetti, S., Spiganti, S., & Zoccoli, C. (2016). Le tecniche edilizie. In G. Agricoli, S. Rafanelli, & S. Carnevali (Eds.), Vetulonia. La Domus dei Dolia: Vol. I (Archeologia Itinera, pp. 21–28). Arcidosso, Italy: Effigi.Search in Google Scholar

Steingräber, S. (2016). Rock tombs and the world of the Etruscan Necropoleis. In A Companion to the Etruscans (pp. 146–161). Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley. doi: 10.1002/9781118354933.ch11.Search in Google Scholar

Stoddart, S. (2016). Beginnings. In S. Bell & A. A. Carpino (Eds.), A companion to the Etruscans (pp. 1–14). Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley. doi: 10.1002/9781118354933.ch1.Search in Google Scholar

Swan, A. R. H., & Sandilands, M. (1995). Introduction to geological data analysis. Oxford: Blackwell Science.Search in Google Scholar

Talocchini, A. (1981). Ultimi dati offerti dagli scavi vetuloniensi. Atti Del XII Convegno Di Studi Etruschi e Italici, 16–20 Giugno 1979 (pp. 100–138). Firenze: Istituto Italiano di Studi Etruschi ed Italici.Search in Google Scholar

Trinidade, M. J., Dias, M. I., Coroado, J., & Rocha, F. (2009). Mineralogical transformations of calcareous rich clays with firing: A comparative study between calcite and dolomite rich clays from Algarve, Portugal. Applied Clay Science, 42(3–4), 345–355. doi: 10.1016/j.clay.2008.02.008.Search in Google Scholar

da Vela, R. (2015). Un database relazionale ed un network di verifica per l’edizione degli scavi di Anna Talocchini a Costa Murata (Vetulonia) 1963–1979. In P. Rondini & L. Zamboni (Eds.), Digging up excavations. Processi di ricontestualizazzione di “vecchi” scavi archeologici: Esperienze, problemi e prospettive. Roma: Edizioni Quasar.Search in Google Scholar

Weaver, I., Meyers, G. E., Mertzman, S. A., Sternberg, R., & Didaleusky, J. (2013). Geochemical evidence for integrated ceramic and roof tile industries at the Etruscan site of Poggio Colla, Italy. Mediterranean Arhaeology and Archaeometry, 13(1), 31–43.Search in Google Scholar

Wentworth, C. K. (1922). A scale of grade and class terms for clastic sediments. The Journal of Geology, 30(5), 377–392. doi: 10.1086/622910.Search in Google Scholar

Winter, N. A. (2002). Commerce in Exile: Terracotta roofing in Etruria, Corfu and Sicily, a Bacchiad family enterprise. Etruscan Studies, 9, 18.10.1515/etst.2002.9.1.227Search in Google Scholar

Winter, N. A., Iliopoulos, I., & Ammerman, A. J. (2009). New light on the production of decorated roofs of the 6th c. B.C. at sites in and around Rome. Journal of Roman Archaeology, 22, 6–28. doi: 10.1017/S1047759400020560.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- A 2D Geometric Morphometric Assessment of Chrono-Cultural Trends in Osseous Barbed Points of the European Final Palaeolithic and Early Mesolithic

- Wealth Consumption, Sociopolitical Organization, and Change: A Perspective from Burial Analysis on the Middle Bronze Age in the Carpathian Basin

- Everything Has a Role to Play: Reconstruction of Vessel Function From Early Copper Age Graves in the Upper Tisza Region (Eastern Hungary)

- Urban Success and Urban Adaptation Over the Long Run

- Exploring Hypotheses on Early Holocene Caspian Seafaring Through Personal Ornaments: A Study of Changing Styles and Symbols in Western Central Asia

- Victims of Heritage Crimes: Aspects of Legal and Socio-Economic Justice

- On the (Non-)Scalability of Target Media for Evaluating the Performance of Ancient Projectile Weapons

- Small Houses of the Dead: A Model of Collective Funerary Activity in the Chalcolithic Tombs of Southwestern Iberia. La Orden-Seminario Site (Huelva, Spain)

- Bigger Fish to Fry: Evidence (or Lack of) for Fish Consumption in Ancient Syracuse (Sicily)

- Terminal Ballistics of Stone-Tipped Atlatl Darts and Arrows: Results From Exploratory Naturalistic Experiments

- First Archaeological Record of the Torture and Mutilation of Indigenous Mapuche During the “War of Arauco,” Sixteenth Century

- The Story of the Architectural Documentation of Hagia Sophia’s Hypogeum

- Iconographic Trends in Roman Imperial Coinage in the Context of Societal Changes in the Second and Third Centuries CE: A Small-Scale Test of the Affluence Hypothesis

- Circular Economy in the Roman Period and the Early Middle Ages – Methods of Analysis for a Future Agenda

- New Insights Into the Water Management System at Tetzcotzinco, Mexico

- How Linguistic Data Can Inform Archaeological Investigations: An Australian Pilot Study Around Combustion Features

- Leadership in the Emergent Baekje State: State Formation in Central-Western Korea (ca. 200–400 CE)

- Middle Bronze Age Settlement in Czeladź Wielka – The Next Step Toward Determining the Habitation Model, Chronology, and Pottery of the Silesian-Greater Poland Tumulus Culture

- On Class and Elitism in Archaeology

- Archaeology of the Late Local Landscapes of the Hualfín Valley (Catamarca, Argentina): A Political Perspective from Cerro Colorado of La Ciénaga de Abajo

- Review Article

- The State of the Debate: Nuragic Metal Trade in the Bronze Age and Early Iron Age

- A Review of Malta’s Pre-Temple Neolithic Pottery Wares

- Commentary Article

- Paradise Found or Common Sense Lost? Göbekli Tepe’s Last Decade as a Pre-Farming Cult Centre

- Special Issue Published in Cooperation with Meso’2020 – Tenth International Conference on the Mesolithic in Europe, edited by Thomas Perrin, Benjamin Marquebielle, Sylvie Philibert, and Nicolas Valdeyron - Part II

- The Time of the Last Hunters: Chronocultural Aspects of Early Holocene Societies in the Western Mediterranean

- Fishing Nets and String at the Final Mesolithic and Early Neolithic Site of Zamostje 2, Sergiev Posad (Russia)

- Investigating the Early-to-Late Mesolithic Transition in Northeastern Italy: A Multifaceted Regional Perspective

- Socioeconomic, Technological, and Cultural Adaptation of the Mesolithic Population in Central-Eastern Cantabria (Spain) in the Early and Middle Holocene

- From Coastal Sites to Elevated Hinterland Locations in the Mesolithic – Discussing Human–Woodland Interaction in the Oslo Fjord Region, Southeast Norway

- Exploitation of Osseous Materials During the Mesolithic in the Iron Gates

- Motorways of Prehistory? Boats, Rivers and Moving in Mesolithic Ireland

- Environment and Plant Use at La Tourasse (South-West France) at the Late Glacial–Holocene Transition

- Stylistic Study of the Late Mesolithic Industries in Western France: Combined Principal Coordinate Analysis and Use-Wear Analysis

- Mesolithic Occupations During the Boreal Climatic Fluctuations at La Baume de Monthiver (Var, France)

- Pressure Flakers of Late Neolithic Forest Hunter-Gatherer-Fishers of Eastern Europe and Their Remote Counterparts

- The Site Groß Fredenwalde, NE-Germany, and the Early Cemeteries of Northern Europe

- Special Issue on Archaeology of Migration: Moving Beyond Historical Paradigms, edited by Catharine Judson & Hagit Nol

- The Blurry Third Millennium. “Neolithisation” in a Norwegian Context

- Movement or Diaspora? Understanding a Multigenerational Puebloan and Ndee Community on the Central Great Plains

- Human Mobility and the Spread of Innovations – Case Studies from Neolithic Central and Southeast Europe

- The Thule Migration: A Culture in a Hurry?

- The Transformation of Domes in Medieval Chinese Mosques: From Immigrant Muslims to Local Followers

- Landscapes of Movement Along the (Pre)Historical Libyan Sea: Keys for a Socio-Ecological History

- Arab Migration During Early Islam: The Seventh to Eighth Century AD from an Archaeological Perspective