Abstract

Objectives

Recurrent pain is a prevalent and severe public health problem among adolescents and is associated with several negative health outcomes. In a representative sample of adolescents this study examined 1) whether exposure to bullying and low socioeconomic status (SES) were associated with recurrent headache, stomachache and backpain, 2) the combined effect of exposure to bullying and low SES on recurrent pain and 3) whether SES modified the association between bullying and recurrent pain.

Methods

Data derived from the Danish contribution to the international collaborative study Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC). The study population was students in three age groups, 11-, 13- and 15-year-olds from nationally representative samples of schools. We pooled participants from the surveys in 2010, 2014 and 2018, n=10,738.

Results

The prevalence of recurrent pain defined as pain ‘more than once a week’ was high: 11.7 % reported recurrent headache, 6.1 % stomachache, and 12.1 % backpain. The proportion who reported at least one of these pains ‘almost every day’ was 9.8 %. Pain was significantly associated with exposure to bullying at school and low parental SES. The adjusted odds ratio (AOR, 95 % CI) for recurrent headache when exposed to both bullying and low SES was 2.69 (1.75–4.10). Equivalent estimates for recurrent stomachache were 5.80 (3.69–9.12), for backpain 3.79 (2.58–5.55), and for any recurrent pain 4.81 (3.25–7.11).

Conclusions

Recurrent pain increased with exposure to bullying in all socioeconomic strata. Students with double exposure, i.e., to bullying and low SES, had the highest OR for recurrent pain. SES did not modify the association between bullying and recurrent pain.

Introduction

Recurrent headache, stomachache, and backpain are prevalent among adolescents [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]. In the international Health Behavior in School-aged Children (HBSC) survey from 2018, 15 % of the participating adolescents reported frequent headache, 13 % frequent backache, and 10 % frequent stomachache across the 45 participating countries [1]. Recurrent pain limits daily functioning; it is associated with poor mental health [2, 9, 10], poor quality of life [11], school stress [12], and sleep disorders [13]. Recurrent pain often tracks into adulthood [14, 15].

Recurrent pain is associated with exposure to bullying [16], [17], [18], [19]. Due et al. [16] found a twofold increase in frequent headache, frequent stomachache and frequent backache among adolescents exposed to bullying at school across 28 countries. Garmy et al. [17] found a similar association in a study of all Icelandic 11-15-year-old schoolchildren. Exposure to bullying at school is also associated with risk behaviours [20], suicide ideation [21], and negative school experiences [22, 23]. These negative consequences often remain into adulthood [24], [25], [26].

The prevalence of headache among adolescents increases with decreasing socioeconomic status (SES) [27, 28]. Several studies found an increasing prevalence of stomachache with decreasing SES [27, 29], [30], [31], [32]. It is less clear whether recurrent backpain among adolescents is associated with lower SES. Some studies reported that there was no such association [33], other studies show higher prevalence among adolescents in socially disadvantaged families [5, 27, 34], and still other studies found unclear patterns of association between lower backpain and SES [35], [36], [37].

Exposure to bullying at school is a common experience and most common among adolescents from lower SES families [38]. Exposure to bullying may have different implications on health depending on the adolescent’s SES, i.e., that students from higher SES seem to be protected against the negative consequences of bullying [39]. Other resources such as feeling empowered and ease of communication with parents buffer against the negative health consequences of exposure to bullying [40]. According to Due et al. [41], such resources are most prevalent in higher SES families. The Adolescent Pathway Model suggests a socially differential vulnerability to poor health, i.e., that adolescents from lower SES are more vulnerable to the harmful consequences of adverse experiences (e.g., bullying) than their peers from higher SES [41].

Little is known about combined effects of exposure to bullying and low SES on pain. Furthermore, no studies have examined whether high SES protects against the harmful effects of exposure to bullying on pain. Therefore, the aims of this study were to examine: 1) whether exposure to bullying and family’s SES were independently associated with recurrent pain in a representative sample of adolescents, 2) the combined effect of exposure to bullying and low SES on recurrent pain and 3) whether SES modified the association between bullying and recurrent pain. We expected that the prevalence of recurrent pain was highest among students frequently exposed to bullying and students from families with lower SES. We also expected that students with higher SES were protected against the harmful effects of being bullied, i.e., emergence of pain symptoms.

Methods

Design and study population

We used data from the Danish arm of the international Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) Study. HBSC is a series of comparable cross-sectional surveys of nationally representative samples of 11-, 13- and 15-year-olds [1]. We pooled data from 2010, 2014 and 2018 to increase the statistical power. The study population was all students in the fifth, seventh and ninth grades (corresponding to the age groups 11, 13 and 15) from random samples of schools. In total, 15,310 students were enrolled in the participating classes, 13,116 (85.7 %) completed the internationally standardized HBSC questionnaire in the classroom [42], and this study included students with complete information about sex, age group, prevalence of recurrent pain, exposure to bullying at school, and SES, n=10,738 (70.1 %).

Outcome measure

Recurrent pain was measured by the HBSC Symptom Check List [43]: “In the last 6 months, how often have you had … headache … stomach-ache … backpain?” with responses dichotomized into recurrent (“about every day” and “more than once a week”) vs. non-recurrent (“about every week”, “about every month”, and “rarely or never”). We also used an outcome measure ‘any recurrent pain’ with an even more restricted definition: reporting at least one of these pains “about every day.” Prior studies suggested that the HBSC Symptom Check List is reliable and valid [43], [44], [45].

Independent variables

Exposure to bullying was measured by the item “How often have you been bullied at school in the past couple of months?” The responses were trichotomized into high exposure (“Several times a week,” “About once a week” and “2–3 times a month”), low exposure (“It has only happened once or twice”) and not bullied (“I have not been bullied at school in the past couple of months”). The high exposure category represents habitual bullying which has severe consequences for mental health [46]. Kyriakides et al. [47] showed that the measure was trustworthy.

SES was measured by parents’ occupation reported by the students. The research group coded the responses into Occupational Social Class (OSC) from I (high) to V (low) and VI for economically inactive parents [48]. Students’ reports about parents’ occupation are valid and appropriate for studies among adolescents [49, 50]. Each participant was categorized into family OSC by the highest-ranking parent: High (I-II, e.g., professionals and managerial positions), middle (III-IV, e.g., technical and administrative staff, skilled workers), and low (V, unskilled workers and VI, economically inactive).

Statistical procedures

First step: inspection of data by crosstabulations and chi2-test for homogeneity. Second step: logistic regression analyses to examine the association between the two independent variables and the four outcome measures, including sex, age group and survey year as control variables. The third step examined the combined effect of low OSC and bullying on pain and whether OSC modified the association between exposure to bullying and pain. The reference group in the logistic regression analysis was students with the combination of high OSC and no exposure to bullying. The logistic regression analyses accounted for the applied cluster sampling by means of multilevel modelling (PROC GLIMMIX in SAS).

Results

The study included 10,738 students, 37.9 % from the 2010-study, 24.8 % from the 2014-study, and 27.3 % from the 2018-study. The proportion of girls was 51.7 %; 33.6 % of participants were fifth graders (mean age (SD) 11.8 (0.42)), 35.2 % were seventh graders (mean age (SD) 13.8 (0.42)), and 31.3 % were ninth graders (mean age (SD) 15.8 (0.42)). Moreover, 16.1 % of the participants had low OSC, 42.7 % medium OSC, and 41.2 % high OSC (Table 1).

Pct. with recurrent headachea, stomachachea, backpaina, and any recurrent painb by sex, age group, survey year, exposure to bullying, and occupational social class (OSC), n=10,738.

| Recurrent headachea, % | Recurrent stomachachea, % | Recurrent backpaina, % | Any recurrent painb, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=10,738) | 11.7 | 6.1 | 12.1 | 9.8 |

| Boys (n=5,190) | 7.3 | 3.6 | 10.8 | 7.0 |

| Girls (n=5,548) | 15.8d | 8.6d | 13.3d | 12.4d |

| 11 years (n=3,611) | 9.4 | 6.7 | 8.9 | 8.4 |

| 13 years (n=3,780) | 12.4 | 6.4 | 12.3 | 10.1 |

| 15 years (n=3,347) | 13.4d | 5.4 | 15.3d | 10.8c |

| Survey year 2010 (n=4,076) | 10.2 | 5.3 | 11.7 | 9.4 |

| Survey year 2014 (n=3,735) | 12.4 | 6.9 | 13.1 | 10.4 |

| Survey year 2018 (n=2,927) | 12.9c | 6.5 | 11.5 | 9.3 |

| Not bullied (n=8,762) | 10.4 | 4.9 | 10.8 | 8.3 |

| Bullied occasionally (n=1,363) | 15.5 | 9.6 | 16.9 | 14.0 |

| Bullied repeatedly (n=613) | 22.7d | 16.2d | 20.2d | 20.4d |

| High OSC (n=4,426) | 10.4 | 5.0 | 11.0 | 8.2 |

| Medium OSC (n=4,587) | 11.8 | 6.4 | 12.2 | 10.1 |

| Low OSC (n=1,725) | 14.6d | 8.5d | 14.7d | 12.8d |

-

a“about every day” and “more than once a week”. bany pain “about every day”. cp<0.01. dp<0.0001.

Table 1 shows the proportion of adolescents with recurrent headache, stomachache and backpain by sex, age group, survey year, exposure to bullying, and OSC. Table 1 also shows the percentage of students who reported at least one of these pains “almost daily”, labeled “any recurrent pain”. The prevalence of pain was high: 11.7 % reported recurrent headache, 6.1 % recurrent stomachache and 12.1 % backpain. Further, 9.8 % of all participants reported at least one of these pains “almost daily.“ For each of the four measures of pain, the prevalence was highest among girls, highest among 15-year-olds, highest among students repeatedly exposed to bullying, and students from lower OSC families, all p-values <0.01.

Table 2 shows the results of the multivariate logistic regression analyses. Exposure to bullying and OSC were independently associated with pain. The left column presents the unadjusted odds ratios (ORs), and the right column the ORs adjusted for sex, age group, and survey year. Comparison of the columns shows that adjustment for sex, age group, and survey year had little effect on the OR-estimates. All four indicators of recurrent pain increased with increasing exposure to bullying and decreased with OSC.

OR (95 % CI) for recurrent headachea, stomachachea, backpaina, and any painb by exposure to bullying and occupational social class (OSC).

| OR (95 % CI) for recurrent headachea | ||

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted for sex, age group and year | |

| Not bullied | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| Bullied occasionally | 1.59 (1.35–1.87) | 1.70 (1.44–2.00) |

| Bullied repeatedly | 2.54 (2.08–3.11) | 2.77 (2.25–3.40) |

| High OSC | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref) |

| Medium OSC | 1.15 (1.01–1.31) | 1.13 (0.99–1.29) |

| Low OSC | 1.47 (1.25–1.73) | 1.49 (1.26–1.77) |

|

|

||

| OR (95 % CI) for recurrent stomachachea |

||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted for sex, age group and year | |

|

|

||

| Not bullied | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| Bullied occasionally | 2.05 (1.67–2.52) | 2.02 (1.64–2.49) |

| Bullied repeatedly | 3.71 (2.93–4.70) | 3.72 (2.92–4.73) |

| High OSC | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref) |

| Medium OSC | 1.30 (1.08–1.55) | 1.26 (1.05–1.55) |

| Low OSC | 1.75 (1.41–2.18) | 1.75 (1.41–2.18) |

|

|

||

| OR (95 % CI) for recurrent backpaina |

||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted for sex, age group and year | |

|

|

||

| Not bullied | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| Bullied occasionally | 1.68 (1.44–1.97) | 1.83 (1.56–2.15) |

| Bullied repeatedly | 2.10 (1.70–2.58) | 2.30 (1.86–2.83) |

| High OSC | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref) |

| Medium OSC | 1.12 (0.98–1.28) | 1.20 (0.98–1.28) |

| Low OSC | 1.40 (1.19–1.64) | 1.43 (1.21–1.68) |

|

|

||

| OR (95 % CI) for any recurrent painb |

||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted for sex, age group and year | |

|

|

||

| Not bullied | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| Bullied occasionally | 1.79 (1.51–2.12) | 1.87 (1.57–2.22) |

| Bullied repeatedly | 2.81 (2.28–3.47) | 2.96 (2.39–3.66) |

| High OSC | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref) |

| Medium OSC | 1.25 (1.09–1.45) | 1.23 (1.07–1.42) |

| Low OSC | 1.63 (1.37–1.95) | 1.62 (1.36–1.94) |

-

a“about every day” and “more than once a week”. bany recurrent pain “about every day”.

Tables 3a–d shows the combined effects of bullying and OSC on the four outcome measures. The adjusted ORs (AORs) (95 % CI) show that adolescents who were often bullied and from the low OSC experienced between 2.7 and 5.8 times higher odds for pain than those from the high OSC who were not exposed to bullying. Adolescents with high exposure to bullying and low OSC had the highest AOR for recurrent stomachache, recurrent backpain, and any recurrent pain.

Adjusteda OR (95 % CI) for recurrent headacheb by combinations of exposure to bullying and OSC.

| Exposure to bullying | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OSC | Not bullied | Occasionally | Repeatedly |

| High | 1 (ref.) | 1.55 (1.16–2.01) | 2.86 (1.96–4.15) |

| Medium | 1.03 (0.80–1.20) | 2.11 (1.65–2.69) | 3.32 (2.45–4.49) |

| Low | 1.55 (1.27–1.88) | 1.90 (1.32–2.71) | 2.69 (1.75–4.10) |

-

aAdjusted for sex, age group and survey year. b“about every day” and “more than once a week”.

Adjusteda OR (95 % CI) for recurrent stomachacheb by combinations of exposure to bullying and OSC.

| Exposure to bullying | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OSC | Not bullied | Occasionally | Repeatedly |

| High | 1 (ref.) | 2.30 (1.61–3.27) | 4.95 (3.23–7.56) |

| Medium | 1.34 (1.07–1.66) | 2.46 (1.78–3.49) | 3.93 (2.69–5.74) |

| Low | 1.72 (1.30–2.26) | 3.17 (2.09–4.79) | 5.80 (3.69–9.12) |

-

aAdjusted for sex, age group and survey year. b“about every day” and “more than once a week”.

Adjusteda OR (95 % CI) for recurrent backpainb by combinations of exposure to bullying and OSC.

| Exposure to bullying | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OSC | Not bullied | Occasionally | Repeatedly |

| High | 1 (ref.) | 1.87 (1.43–2.43) | 2.59 (1.78–3.74) |

| Medium | 1.12 (0.96–1.30) | 2.15 (1.69–2.73) | 1.95 (1.38–2.73) |

| Low | 1.38 (1.13–1.67) | 2.09 (1.48–2.94) | 3.79 (2.58–5.55) |

-

aAdjusted for sex, age group and survey year. b“about every day” and “more than once a week”.

Adjusteda OR (95 % CI) for any recurrent painb by combinations of exposure to bullying and OSC.

| Exposure to bullying | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OSC | Not bullied | Occasionally | Repeatedly |

| High | 1 (ref.) | 1.66 (1.22–2.25) | 2.71 (1.81–4.01) |

| Medium | 1.14 (0.96–1.35) | 2.44 (1.89–3.15) | 3.13 (2.25–4.33) |

| Low | 1.51 (1.21–1.87) | 2.33 (1.62–3.35) | 4.81 (3.25–7.11) |

-

aAdjusted for sex, age group and survey year. bany pain “about every day”.

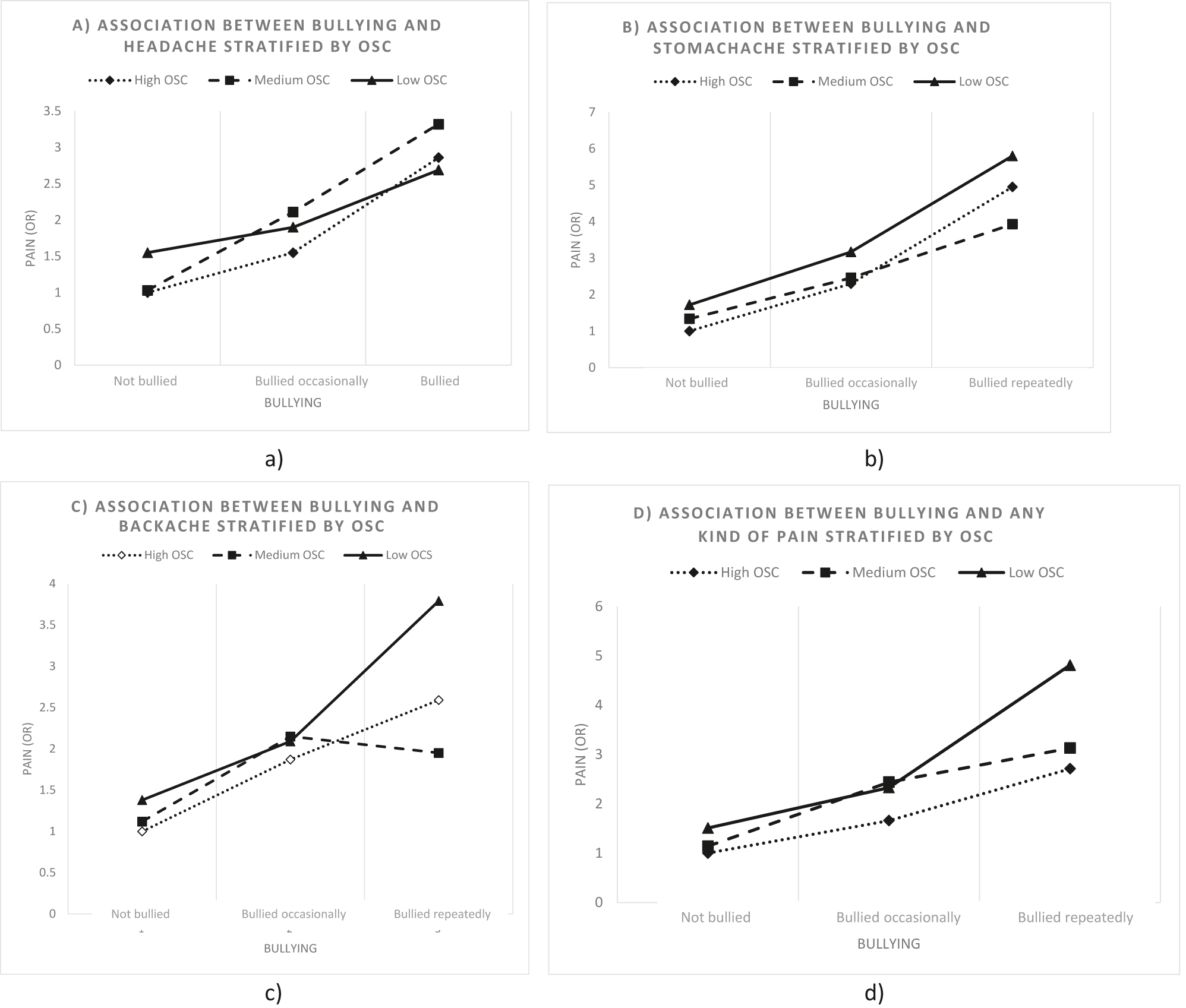

Figure 1A–D shows the association between exposure to bullying and the four pain variables stratified by OSC. The associations appear similar for all OSC-groups. The confidence intervals for students from the low OSC-group who were exposed to bullying repeatedly were quite broad (not shown in the Figure). Judged by the confidence intervals, there were no significant differences between the three lines in any of the four figures. Thus, SES did not modify the association between exposure to bullying and pain as expected.

OR (95 % CI) for the four recurrent pain indicators and exposure to bullying stratified by occupational social class (OSC), adjusted for sex, age group, and survey year.

Discussion

Main findings

There were four main findings. First, the prevalence of recurrent pain was high, a finding which corresponded with other recent studies [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8, 29, 51]. Having pain “almost every day” is not trivial. It is an important public health problem that such a high proportion of adolescents suffer from recurrent pain. Second, the prevalence of pain was significantly and independently elevated for students exposed to bullying at school and to students from lower SES. This finding also corresponded with several other studies [16, 17]. Third, the odds for recurrent pain were extraordinarily high for students with double exposure, i.e., exposure to bullying and low SES. We have not been able to identify other studies that explored the joint effect of bullying and SES on adolescents’ recurrent pain. Fourth, SES did not modify the association between exposure to bullying and recurrent pain. For each of the four indicators of recurrent pain, the association between exposure to bullying and pain was similar in all socioeconomic groups. Therefore, the study did not confirm the theoretical assumption of a socially patterned vulnerability [41, 51], i.e., that adolescents from lower SES should be more susceptible to harmful exposures than their peers from higher SES.

The experience of recurrent pain such as headache, stomachache and backpain is related to a range of somatic problems and lifestyle factors [6, 7, 15, 31, 34, 52, 53], and also considered an important indicator of poor mental health [2, 9, 10]. The underlying causes of headache, stomachache, and backpain are complex and cover more ground than just poor mental health. Wickström & Lindholm [54] interviewed 15-year-olds from Sweden about how they understood and answered the items from the HBSC Symptom Check List, which we applied in our study. Their study showed that pain symptoms could not be attributed to poor mental health alone [54]. Our study suggests that objective environmental factors such as exposure to bullying and low SES are key factors in the etiology of recurrent pain.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of the study is the large and nationally representative study population and the robustness of the applied measurements. There are important limitations as well. One is the cross-sectional design which limits the insight into causality. There is a need for longitudinal studies of the association between exposure to bullying and recurrent pain to explore possible reverse causality. This issue is less relevant for the SES-pain association because parents’ SES is unlikely to be caused by their offspring’s pain.

Another strength is the fair participation rate among pupils (70.1 %). Some selection bias may occur on student level in this study. It is likely that students who were frequently bullied and/or had recurrent pain were more likely to be absent from school on the day of data collection. This could potentially result in an underestimation of the prevalence of exposure to bullying and the prevalence of pain. If there is an underestimation of both exposure and outcome, the analyses could potentially also underestimate the association between exposure to bullying and recurrent pain.

We decided to conceptualize recurrent pain as pain occurring more than once weekly, even though having pain once a week might be equally debilitating [9, 32, 55]. Furthermore, it is a limitation that the pain measurement only focuses on frequency but not intensity. The exposure item and the outcome items included in this study have undergone extensive validation work conducted by the Health Behavior in School-Aged Children’s (HBSC) network and other researchers during the last decade and several studies have suggested that these measurements are applicable and valid [43], [44], [45, 47], [48], [49], [50, 56].

The study may suffer from unmeasured confounding. For example, we did not have access to objective information about health problems in the participants. If the participants have physical health problems which cause pain and if adolescents with physical illness are at higher risk of being bullied [57], that may account for some of the association between exposure to bullying and recurrent pain. Furthermore, we did not have access to information about illness of the adolescents’ parents. Previous studies link parents’ physical and mental illness to exposure to bullying of their children, to lower SES, and to the experience of pain [58].

Implications for future research

Even though we did not find that occupational social class modified the association between exposure to bullying and experiencing recurrent pain, it is likely that other factors may modify the association. Factors such as close relations to parents or to teachers at school may have buffering effects on the association [40]. Also, illness in the close family may amplify the effects of exposure to bullying, i.e., be an important effect modifier. Therefore, we encourage future studies to investigate other potential effect modifiers in the association between exposure to bullying and pain to identify intervention potential.

Implications for practice

The results underline the importance of implementing bullying preventive interventions at school. The school is an ideal setting for interventions as it is possible to target the entire adolescent population. Further, research suggests that bullying interventions are effective in decreasing bullying and victimization [59, 60]. Thus, schools may be an important context to reduce bullying behaviour and thereby prevent and reduce recurrent pain [19], risk behaviours [20], suicide ideation [21] and negative school experiences [22, 23]. The results also point to the importance of ensuring awareness and knowledge among health workers and teachers at schools about how to detect and react to adolescents who express recurrent pain.

Conclusions

Experiencing headache, stomachache, and backpain more than once a week was prevalent among Danish adolescents. The combined exposure to low SES and being bullied at school multiplied the occurrence of recurrent pain. Exposure to bullying at school increased the prevalence of recurrent pain regardless of the participants’ socioeconomic status.

Acknowledgements

Pernille Due was the Principal Investigator for the Danish HBSC studies in 2010 and Mette Rasmussen in 2014 and 2018.

-

Research funding: The Nordea foundation (grant number 02-2011-0122) provided economic support for the 2010 study and The Danish Health Authority (grant number 1-1010-274/13) for the 2018 survey. The funding agencies did not interfere in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, writing of this article or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. None of the authors received any honorarium, grant or other form of payment to produce the manuscript.

-

Author contributions: All authors have contributed substantially to the conception and design of the paper and to the interpretation of data. BEH and KRM contributed to the data collection. BEH performed the analyses and KMM wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and a critical revision of the intellectual content. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Informed consent and ethical approval: There are no formal agency for approval of questionnaire-based surveys in Denmark. Therefore, we asked the school board as the parents’ representative, the principal, and the students’ council in each of the participating schools to approve the study. The participants received oral and written information that participation was voluntary, and that data were treated confidentially. The study complied with national standards for data protection. From 2014 the Danish Data Protection Authority has requested notification of such studies and has granted acceptance for the 2014 survey (Case No. 2013-54-0576) and the 2018 survey (Case No. 10 622, University of Southern Denmark).

References

1. Inchley, J, Currie, D, Budisavljevic, S, Torsheim, T, Jåstad, A, Cosma, A, et al.. Spotlight on adolescent health and well-being. volume 1. key findings. Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 2020.Search in Google Scholar

2. Blaauw, BA, Dyb, G, Hagen, K, Holmen, TL, Linde, M, Wentzel-Larsen, T, et al.. Anxiety, depression and behavioral problems among adolescents with recurrent headache: the Young-HUNT study. J Headache Pain 2014;15:38. https://doi.org/10.1186/1129-2377-15-38.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Holstein, BE, Andersen, A, Denbaek, AM, Johansen, A, Michelsen, SI, Due, P. Short communication: persistent socio-economic inequality in frequent headache among Danish adolescents from 1991 to 2014. Eur J Pain 2018;22:935–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1179.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Swain, MS, Henschke, N, Kamper, SJ, Gobina, I, Ottová-Jordan, V, Maher, CG. An international survey of pain in adolescents. BMC Publ Health 2014;14:447. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-447.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Holstein, BE, Damsgaard, MT, Madsen, KR, Pedersen, TP, Toftager, M. Chronic backpain among adolescents in Denmark: trends 1991–2018 and association with socioeconomic status. Eur J Pediatr 2022;181:691–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-021-04255-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Waldie, KE, Thompson, JM, Mia, Y, Murphy, R, Wall, C, Mitchell, EA. Risk factors for migraine and tension-type headache in 11 year old children. J Headache Pain 2014;15:60. https://doi.org/10.1186/1129-2377-15-60.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Kamper, SJ, Yamato, TP, Williams, CM. The prevalence, risk factors, prognosis and treatment for back pain in children and adolescents: an overview of systematic reviews. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2016;30:1021–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdy129.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Gobina, I, Villberg, J, Välimaa, R, Tynjälä, J, Whitehead, R, Cosma, A, et al.. Prevalence of self-reported chronic pain among adolescents: evidence from 42 countries and regions. Eur J Pain 2019;23:316–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1306.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Batley, S, Aartun, E, Boyle, E, Hartvigsen, J, Stern, PJ, Hestbæk, L. The association between psychological and social factors and spinal pain in adolescents. Eur J Pediatr 2019;178:275–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-018-3291-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Ayonrinde, OT, Ayonrinde, OA, Adams, LA, Sanfilippo, FM, O’Sullivan, TA, Robinson, M, et al.. The relationship between abdominal pain and emotional wellbeing in children and adolescents in the Raine Study. Sci Rep 2020;10:1646. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58543-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Svedberg, P, Eriksson, M, Boman, E. Associations between scores of psychosomatic health symptoms and health-related quality of life in children and adolescents. Health Qual Life Outcome 2013;11:176. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-11-176.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Hjern, A, Alfven, G, Ostberg, V. School stressors, psychological complaints and psychosomatic pain. Acta Paediatr 2008;97:112–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00585.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Huntley, ED, Campo, JV, Dahl, RE, Lewin, DS. Sleep characteristics of youth with functional abdominal pain and a healthy comparison group. J Pediatr Psychol 2007;32:938–49. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsm032.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Hestbaek, L, Leboeuf-Yde, C, Kyvik, KO, Manniche, C. The course of low back pain from adolescence to adulthood: eight-year follow-up of 9600 twins. Spine 2006;31:468–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000199958.04073.d9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Harreby, M, Nygaard, B, Jessen, T, Larsen, E, Storr-Paulsen, A, Lindahl, A, et al.. Risk factors for low back pain in a cohort of 1389 Danish school children: an epidemiologic study. Eur Spine J 1999;8:444–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s005860050203.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Due, P, Holstein, BE, Lynch, J, Diderichsen, F, Gabhain, SN, Scheidt, P, et al.. Bullying and symptoms among school-aged children: international comparative cross sectional study in 28 countries. Eur J Publ Health 2005;15:128–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cki105.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Garmy, P, Hansson, E, Vilhjalmsson, R, Kristjansdottir, G. Bullying and pain in school-aged children and adolescents: a cross-sectional study. SAGE Open Nurs 2019;5:2377960819887556. https://doi.org/10.1177/2377960819887556.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Fekkes, M, Pijpers, FI, Verloove-Vanhorick, SP. Bullying behavior and associations with psychosomatic complaints and depression in victims. J Pediatr 2004;144:17–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.09.025.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Gini, G. Associations between bullying behaviour, psychosomatic complaints, emotional and behavioural problems. J Paediatr Child Health 2008;44:492–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01155.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Vieno, A, Gini, G, Santinello, M. Different forms of bullying and their association to smoking and drinking behavior in Italian adolescents. J Sch Health 2011;81:393–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00607.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Barzilay, S, Brunstein Klomek, A, Apter, A, Carli, V, Wasserman, C, Hadlaczky, G, et al.. Bullying victimization and suicide ideation and behavior among adolescents in Europe: a 10-country study. J Adolesc Health 2017;61:179–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.02.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Bowser, J, Larson, JD, Bellmore, A, Olson, C, Resnik, F. Bullying victimization type and feeling unsafe in middle school. J Sch Nurs 2018;34:256–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059840518760983.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Harel-Fisch, Y, Walsh, SD, Fogel-Grinvald, H, Amitai, G, Pickett, W, Molcho, M, et al.. Negative school perceptions and involvement in school bullying: a universal relationship across 40 countries. J Adolesc 2011;34:639–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.09.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Copeland, WE, Wolke, D, Angold, A, Costello, EJ. Adult psychiatric outcomes of bullying and being bullied by peers in childhood and adolescence. JAMA Psychiatr 2013;70:419–26. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.504.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Wolke, D, Copeland, WE, Angold, A, Costello, EJ. Impact of bullying in childhood on adult health, wealth, crime, and social outcomes. Psychol Sci 2013;24:1958–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613481608.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Takizawa, R, Maughan, B, Arseneault, L. Adult health outcomes of childhood bullying victimization: evidence from a five-decade longitudinal British birth cohort. Am J Psychiatr 2014;171:777–84. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101401.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Holstein, BE, Currie, C, Boyce, W, Damsgaard, MT, Gobina, I, Kökönyei, G, et al.. Socio-economic inequality in multiple health complaints among adolescents: international comparative study in 37 countries. Int J Publ Health 2009;54:260–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-009-5418-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Lenzi, M, Vieno, A, De Vogli, R, Santinello, M, Ottova, V, Baška, T, et al.. Perceived teacher unfairness and headache in adolescence: a cross-national comparison. Int J Publ Health 2013;58:227–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-012-0345-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Holstein, BE, Damsgaard, MT, Ammitzbøll, J, Madsen, KR, Pedersen, TP, Rasmussen, M. Recurrent abdominal pain among adolescents: trends and social inequality 1991–2018. Scand J Pain 2021;21:95–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-009-5418-4.Search in Google Scholar

30. Inchley, J, Currie, D, Young, T, Samdal, O, Torsheim, T, Augustson, L, et al.. Growing up unequal: gender and socioeconomic differences in young people’s health and well-being. Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 2016.Search in Google Scholar

31. Chitkara, DK, Rawat, DJ, Talley, NJ. The epidemiology of childhood recurrent abdominal pain in Western countries: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:1868–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41893.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Grøholt, EK, Stigum, H, Nordhagen, R, Köhler, L. Recurrent pain in children, socio-economic factors and accumulation in families. Eur J Epidemiol 2003;18:965–75. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1025889912964.10.1023/A:1025889912964Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Sjölie, AN. Psychosocial correlates of low-back pain in adolescents. Eur Spine J 2002;11:582–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-002-0412-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Joergensen, AC, Hestbaek, L, Andersen, PK, Nybo Andersen, AM. Epidemiology of spinal pain in children: a study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. Eur J Pediatr 2019;178:695–706. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-019-03326-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. King, S, Chambers, CT, Huguet, A, MacNevin, RC, McGrath, PJ, Parker, L, et al.. The epidemiology of chronic pain in children and adolescents revisited: a systematic review. Pain 2011;152:2729–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.016.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Hestbaek, L, Korsholm, L, Leboeuf-Yde, C, Kyvik, KO. Does socioeconomic status in adolescence predict low back pain in adulthood? A repeated cross-sectional study of 4,771 Danish adolescents. Eur Spine J 2008;17:1727–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-008-0796-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Leboeuf-Yde, C, Wedderkopp, N, Andersen, LB, Froberg, K, Hansen, HS. Back pain reporting in children and adolescents: the impact of parents’ educational level. J Manip Physiol Ther 2002;25:216–20. https://doi.org/10.1067/mmt.2002.123172.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Due, P, Merlo, J, Harel-Fisch, Y, Damsgaard, MT, Holstein, BE, Hetland, J, et al.. Socioeconomic inequality in exposure to bullying during adolescence: a comparative, cross-sectional, multilevel study in 35 countries. Am J Publ Health 2009;99:907–14. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.139303.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

39. Due, P, Damsgaard, MT, Lund, R, Holstein, BE. Is bullying equally harmful for rich and poor children? A study of bullying and depression from age 15 to 27. Eur J Publ Health 2009;19:464–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckp099.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Gilman, DK, Palermo, TM, Kabbouche, MA, Hershey, AD, Powers SWNation, M, Vieno, A, et al.. Bullying in school and adolescent sense of empowerment: an analysis of relationships with parents, friends, and teachers. J Community Appl Soc Psychol 2008;18:211–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.921.Search in Google Scholar

41. Due, P, Krølner, R, Rasmussen, M, Andersen, A, Trab Damsgaard, M, Graham, H, et al.. Pathways and mechanisms in adolescence contribute to adult health inequalities. Scand J Publ Health 2011;39:62–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494810395989.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

42. Roberts, C, Freeman, J, Samdal, O, Schnohr, CW, de Looze, ME, Nic Gabhainn, S, et al.. The Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study: methodological developments and current tensions. Int J Publ Health 2009;54:140–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-009-5405-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

43. Ravens-Sieberer, U, Erhart, M, Torsheim, T, Hetland, J, Freeman, J, Danielson, M, et al.. An international scoring system for self-reported health complaints in adolescents. Eur J Publ Health 2008;18:294–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckn001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

44. Haugland, S, Wold, B, Stevenson, J, Aaroe, LE, Woynarowska, B. Subjective health complaints in adolescence: a cross-national comparison of prevalence and dimensionality. Eur J Publ Health 2001;11:4–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/11.1.4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

45. Haugland, S, Wold, B. Subjective health complaints in adolescence – reliability and validity of survey methods. J Adolesc 2001;24:611–24. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.2000.0393.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

46. Lund, R, Nielsen, KK, Hansen, DH, Kriegbaum, M, Molbo, D, Due, P, et al.. Exposure to bullying at school and depression in adulthood: a study of Danish men born in 1953. Eur J Publ Health 2009;19:111–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckn101.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

47. Kyriakides, L, Kaloyirou, C, Lindsay, G. An analysis of the revised olweus bully/victim questionnaire using the rasch measurement model. Br J Educ Psychol 2006;76:781–801. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709905X53499.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

48. Christensen, U, Krølner, R, Nilsson, CJ, Lyngbye, PW, Hougaard, C, Nygaard, E, et al.. Addressing social inequality in aging by the Danish occupational social class measurement. J Aging Health 2014;26:106–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264314522894.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

49. Lien, N, Friestad, C, Klepp, KI. Adolescents’ proxy reports of parents’ socioeconomic status: how valid are they? J Epidemiol Community Health 2001;55:731–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.55.10.731.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

50. Pförtner, T-K, Günther, S, Levin, K, Torsheim, T, Richter, M. The use of parental occupation in adolescent health surveys. An application of ISCO-based measures of occupational status. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015;69:177–84. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2014-204529.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

51. Diderichsen, F, Andersen, I, Manuel, C, Andersen, AM, Bach, E, Baadsgaard, M, et al.. Health inequality – determinants and policies. Scand J Publ Health 2012;40:12–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494812457734.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

52. Swain, MS, Henschke, N, Kamper, SJ, Gobina, I, Ottová-Jordan, V, Maher, CG. Pain and moderate to vigorous physical activity in adolescence: an international population-based survey. Pain Med 2016;17:813–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/pme.12923.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

53. Klavina-Makrecka, S, Gobina, I, Pulmanis, T, Pudule, I, Villerusa, A. Insufficient sleep duration in association with self-reported pain and corresponding medicine use among adolescents: a cross-sectional population-based study in Latvia. Int J Publ Health 2020;65:1365–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-020-01478-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

54. Wickström, A, Lindholm, SK. Young people’s perspectives on the symptoms asked for in the Health Behavior in School-Aged Children survey. Childhood 2020;27:450–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568220919878.56.Search in Google Scholar

55. Straube, A, Heinen, F, Ebinger, F, von Kries, R. Headache in school children: prevalence and risk factors. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2013;110:811–8. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2013.0811.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

56. Solberg, ME, Olweus, D. Prevalence estimation of school bullying with the olweus bully/victim questionnaire. Aggress Behav 2003;29:239–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.10047.Search in Google Scholar

57. Pinquart, M. Systematic Review: bullying involvement of children with and without chronic physical illness and/or physical/sensory disability – a meta-analytic comparison with healthy/nondisabled peers. J Pediatr Psychol 2016;42:245–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsw081.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

58. Elliott, L, Thompson, KA, Fobian, AD. A Systematic review of somatic symptoms in children with a chronically ill family member. Psychosom Med 2020;82:366–76. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000799.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

59. Evans, CBR, Fraser, MW, Cotter, KL. The effectiveness of school-based bullying prevention programs: a systematic review. Aggress Violent Behav 2014;19:532–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2014.07.004.Search in Google Scholar

60. Vreeman, RC, Carroll, AE. A systematic review of school-based interventions to prevent bullying. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2007;161:78–88. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.161.1.78.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Systematic Review

- Comparison of the effectiveness of eHealth self-management interventions for pain between oncological and musculoskeletal populations: a systematic review with narrative synthesis

- Topical Review

- Shifting the perspective: how positive thinking can help diminish the negative effects of pain

- Clinical Pain Researches

- Pain acceptance and psychological inflexibility predict pain interference outcomes for persons with chronic pain receiving pain psychology

- A feasibility trial of online Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for women with provoked vestibulodynia

- Relations between PTSD symptom clusters and pain in three trauma-exposed samples with pain

- Short- and long-term test–retest reliability of the English version of the 7-item DN4 questionnaire – a screening tool for neuropathic pain

- Chronic post-thoracotomy pain after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study of preoperative risk factors

- Pain sensitivity after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass – associations with chronic abdominal pain and psychosocial aspects

- Barriers in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) management: perspectives from health practitioners

- Observational studies

- Spontaneous self-affirmation: an adaptive coping strategy for people with chronic pain

- COVID-19 and processes of adjustment in people with persistent pain: the role of psychological flexibility

- Presence and grade of undertreatment of pain in children with cerebral palsy

- Sex-related differences in migraine clinical features by frequency of occurrence: a cross-sectional study

- Recurrent headache, stomachache, and backpain among adolescents: association with exposure to bullying and parents’ socioeconomic status

- Original Experimentals

- Temporal stability and responsiveness of a conditioned pain modulation test

- Anticipatory postural adjustments mediate the changes in fear-related behaviors in individuals with chronic low back pain

- The role of spontaneous vs. experimentally induced attentional strategies for the pain response to a single bout of exercise in healthy individuals

- Acute exercise of painful muscles does not reduce the hypoalgesic response in young healthy women – a randomized crossover study

- Short Communications

- Nation-wide decrease in the prevalence of pediatric chronic pain during the COVID-19 pandemic

- A multidisciplinary transitional pain service to improve pain outcomes following trauma surgery: a preliminary report

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Systematic Review

- Comparison of the effectiveness of eHealth self-management interventions for pain between oncological and musculoskeletal populations: a systematic review with narrative synthesis

- Topical Review

- Shifting the perspective: how positive thinking can help diminish the negative effects of pain

- Clinical Pain Researches

- Pain acceptance and psychological inflexibility predict pain interference outcomes for persons with chronic pain receiving pain psychology

- A feasibility trial of online Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for women with provoked vestibulodynia

- Relations between PTSD symptom clusters and pain in three trauma-exposed samples with pain

- Short- and long-term test–retest reliability of the English version of the 7-item DN4 questionnaire – a screening tool for neuropathic pain

- Chronic post-thoracotomy pain after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study of preoperative risk factors

- Pain sensitivity after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass – associations with chronic abdominal pain and psychosocial aspects

- Barriers in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) management: perspectives from health practitioners

- Observational studies

- Spontaneous self-affirmation: an adaptive coping strategy for people with chronic pain

- COVID-19 and processes of adjustment in people with persistent pain: the role of psychological flexibility

- Presence and grade of undertreatment of pain in children with cerebral palsy

- Sex-related differences in migraine clinical features by frequency of occurrence: a cross-sectional study

- Recurrent headache, stomachache, and backpain among adolescents: association with exposure to bullying and parents’ socioeconomic status

- Original Experimentals

- Temporal stability and responsiveness of a conditioned pain modulation test

- Anticipatory postural adjustments mediate the changes in fear-related behaviors in individuals with chronic low back pain

- The role of spontaneous vs. experimentally induced attentional strategies for the pain response to a single bout of exercise in healthy individuals

- Acute exercise of painful muscles does not reduce the hypoalgesic response in young healthy women – a randomized crossover study

- Short Communications

- Nation-wide decrease in the prevalence of pediatric chronic pain during the COVID-19 pandemic

- A multidisciplinary transitional pain service to improve pain outcomes following trauma surgery: a preliminary report