Abstract

Objectives

To investigate if chronic pain in children with cerebral palsy is undertreated with the current pharmacological/non-pharmacological interventions using a pain management index.

Methods

Parents of 120 children with cerebral palsy between the ages of 2–19 years from our region in Denmark answered a questionnaire about whether their child had everyday pain. When answering in pain, we inquired about pain status and pharmacological/non-pharmacological pain coping interventions. Everyday pain was viewed as chronic pain with acute exacerbations. Pain experienced was divided into worst pain (highest moments of pain intensity) and least pain (lowest moments of pain intensity). To describe and evaluate the effectiveness of pain interventions used, a pain management index was utilized. Everyday pain was assessed using a logistical regression by adjusting for age, sex, and gross motor function classification system level.

Results

59/115 (0.51) of parents answering the questionnaire reported everyday pain. Of those, the median age was 10 years. For pain alleviation, massage was reported by parents as being used by 29/59 (0.49) children and paracetamol by 21/59 (0.36). Pain affected daily life in 44/59 (0.75). By our evaluation 44/59 (0.75) were inadequately treated for their pain. Our evaluation also revealed that 19/59 (0.32) of children in pain had inadequately treated pain combined with an undesirable intensity of least pain.

Conclusions

Half of the children with cerebral palsy experienced chronic pain according to our pain questionnaire answered by parents. Among these children three-quarters were insufficiently treated for their pain. In the same group, one-third were impacted by pain felt at both its highest and lowest moments of intensity. Massage therapy and paracetamol were the most frequently utilized pain-alleviating interventions. In our cohort, pain was undertreated and likely underdiagnose (Protocol number H-17008823).

Introduction

One of the most common inborn childhood neurological diseases is cerebral palsy (CP) with a prevalence of 1.5–2.7 per 1,000 live births [1]. CP is perceived as a primary movement disorder, but the components of sensory disturbances of pain in children with CP are often unrecognized and thus underappreciated in pain treatment [1], [2], [3]. The occurrence of pain globally has an alarming prevalence of up to 74 percent in the pediatric population with CP and is often more secondary to musculoskeletal complications than it is related to the disease itself (e.g. hip dislocation, musculoskeletal deformity, scoliosis, spasticity) or due to interventions (e.g. surgery, physiotherapy, botulinum toxin injections) [4, 5]. Pain in children with CP has a major impact on the quality of life as it affects activities of daily living and quality of sleep. This can influence mental health negatively [1, 5, 6] and can consequently reduce the quality of life of the parents significantly [7]. Evidently, for these children, there appears to be an urgent need for pain treatment, but as long as the extent and nature of pain and pain treatment are poorly mapped, we are unable to provide children with CP adequate pharmacological and non-pharmacological pain interventions [8], [9], [10].

We sought to investigate how pain in children with CP was treated with the current medical pain treatment and pain coping interventions for everyday pain in our region using the pain management index (PMI). The PMI can be used to describe analgesic interventions and evaluate the adequacy of pain interventions [11], [12], [13]. Cleeland et al. originally developed the PMI to evaluate cancer patient’s worst pain to their prescribed pain medication to determine the adequacy of pain management [12]. Since then, the PMI has been modified to evaluate several other types of pain. We utilized a modified PMI, which evaluated if pain treatment was sufficient when compared to the individual patient’s pain level by a dichotomous score [11, 12]. The PMI score is then calculated by comparing the worst pain intensity, as in the pain at its highest moments of intensity, to pain treatment by subtracting a pain intensity score (0–3) from a treatment ‘analgesic score’ (0–3). A negative value of PMI indicates undertreatment in pain management while zero and positive values indicate adequate pain management [11, 12]. We utilized the modification of Ward et al. by including the pain medication actually used instead of prescribed and most notably also incorporated the least pain intensity (pain at its lowest moments) felt in addition to worst pain intensity (pain at its highest moments) to stratify the adequacy of pain treatment further into a grouped PMI of (1) inadequate pain management & undesirable least pain; (2) Adequate pain management & undesirable least pain; (3) Inadequate pain management & desirable least pain; and (4) Adequate pain management & desirable least pain [11, 13]. Grouping the PMI helps identify children with the most impactful pain, irrespective of fluctuations in pain intensity as both the highest and lowest moments of pain are accounted for. We found this approach purposeful for our study since pain in CP usually is chronic, recurrent and weak with acute exacerbations (of more severe pain) due to specific events (e.g. surgery or botulinum toxin injections) [5].

We also examined the type of pain treatment used and inquired into the prevalence, intensity, and anatomical location of the pain using a similar methodology as Eriksson et al. [1].

Methods

Study population

We included children with CP between 2 and 19 years of age as subjects in a convenience sample from our hospital’s primary service area in the island of Zealand.

Questionnaire

On March 2, 2019, parents were sent a questionnaire by letter to assess the treatment of pain in their children’s everyday life.

Definition of pain

We defined everyday pain as recurrent or chronic pain with acute exacerbations, which is consistent with previous studies on those with CP [14]. To account for the fluctuation in pain intensity during episodes of persistent pain, we utilized an established methodology used in other pain studies, incorporating both maximum and minimum pain levels scored separately by the subject’s parents between 0 and 10 using the numerical rating scale (NRS) [13, 15, 16]. Specifically, we defined the lowest or minimum momentary pain level experienced when in pain as “least pain”, while the highest or maximum momentary pain level was defined as “worst pain”.

The modified pain management index

Our ‘analgesic score’ was based on our question of ‘what usually alleviates their pain’. The pain intensity score was graded based on worst pain and using the NRS with 0 being none, 1–3 being mild, 4–7 being moderate, and 8–10 being severe which translated to a pain intensity score of 0, 1, 2, and 3, respectively [11, 12]. We modified the PMI ‘analgesic score’ based on the World Health Organizations’ (WHO) pain ladder for chronic pain in children to accommodate our pediatric population of CP patients [17]. Therefore, we modified the PMI to include non-pharmacological pain management as a separate treatment ‘analgesic score’, and the use of opioid medication of any kind as the highest ‘analgesic score’ option. Thus, the level of pain treatment grade by our analgesic score was 0 for no pain therapy, 1 for non-pharmacological pain coping strategies only (massage, physical therapy, temperature therapy, etc.), 2 for any kind of non-opioid medication (paracetamol, ibuprofen, gabapentin, chlorzoxazone, baclofen, botulinum toxin, etc.), and 3 for any type of opioid. We incorporated the subject’s least pain for our grouped PMI, stratifying it into either desirable (NRS 0–2) or undesirable (NRS 3–10). We graded least pain as desirable when the NRS score was between 0-2 due to this being seen as the desired goal for pain management among patients [13]. We divided the PMI score into four groups as described in the introduction, called the grouped PMI, allowing us to evaluate the adequacy of treatment in relation to pain intensity at both its highest and lowest moments in those with chronic pain. A higher grouped PMI value indicated a more effective use of pain interventions.

Demographics

Data regarding age and sex was extracted from the subject’s social security number at the time of inclusion, while their Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) level was obtained from their medical records.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were reported as medians with 25th–75th percentiles and categorical variables as fractions. Between-group differences were compared using Mann-Whitney U and Chi-square tests, as appropriate. We performed both a 2x2 and a 2x5 Chi-square cross-tabulation test to determine significant distribution differences between our study sample and data from the latest Danish Cerebral Palsy Follow-up Program (CPOP) concerning age and GMFCS levels, respectively [18]. Using univariable logistic regression, we examined factors associated with pain (age, sex, and GMFCS level). Due to age differences, we categorized age according to tertiles (2–9, 9–13, and 13–19 years). Furthermore, we assessed the association between pain and age, sex, and GMFCS level using multivariable logistic regression. We computed odds ratios (ORs) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs). All statistical analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (version 3.6.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Population, pain prevalence, dependency of age, sex, and GMFCS level

The questionnaire was sent to the parents of a total of 290 children with CP. 120/290 (0.41) subjects participated by their parents responding whereas 115/290 (0.40) were eligible. 4/120 (0.03) subjects were excluded due to their age being above 19 years and 1/120 (0.01) were excluded due to insufficient response data. Parents of 59/115 (0.51) subjects indicated that their child was in pain and 58/59 (0.98) of these parents answered the questionnaire concerning pain, treatment of it, and pain coping interventions used. The translated questionnaire from their native language is depicted in the supplemental files in Supplementary Figure 1. For the CP children with everyday pain, the median age was ten years (Q1: 7.5, Q3: 13). The male:female ratio was 2:1 (41/18). The distribution of subjects according to GMFCS level was 1.5:1:0.5 (30/20/9) for GMFCS levels I, II-IV, and V. Results from the logistic regression are summarized in Table 1.

Logistical regression with an unadjusted and adjusted odds ratio for everyday pain in 115 children with cerebral palsy.

| Unadjusted OR (95 % CI) | Adjusteda OR (95 % CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years (n=115) | ||

|

|

||

| 9–13 (n=35) | 0.91 (0.37–2.25) | 0.86 (0.34–2.18) |

| 13–19 (n=42) |

0.50 (0.21–1.21) |

0.50 (0.20–1.29) |

| Sex (n=115) | ||

|

|

||

| Female (n=39) |

0.73 (0.34–1.59) |

0.64 (0.28–1.46) |

| GMFCS level (n=115) | ||

|

|

||

| II–IV (n=43) | 0.87(0.40–1.91) | 1.01 (0.44–2.33) |

| V (n=12) | 3.00 (0.74–12.18) | 3.58 (0.85–15.07) |

-

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; GMFCS, gross motor function classification system. Reference groups were age 2–9 years, male sex, and GMFCS level I. Age was analysed as a categorical variable. aAdjusted for age, GMFCS level, and sex.

Pain medication and other pain coping interventions

Characteristics of pain coping interventions are summarized in Table 2. 1/59 (0.02) subjects supplemented paracetamol with ibuprofen, gabapentin, and chlorzoxazone. The distribution of pain coping interventions used is illustrated in Figure 1. 34/59 (0.58) used any kind of non-pharmacological pain coping intervention for alleviating pain.

Characteristics of pain coping interventions used alone or in combination for 59 children with cerebral palsy that experience everyday pain.

| Pain coping interventions used (alone or in combination) | Number of subjects (as fractions) |

|---|---|

| Massage | 29/59 (0.49) |

| Paracetamol monotherapy | 21/59 (0.36) |

| Physiotherapy | 4/59 (0.07) |

| Other modalities (alone or in combination) | 10/59 (0.17) |

| Temperature therapy | 5/59 (0.09) |

| Foot bath | 1/59 (0.02) |

| Solicitude | 1/59 (0.02) |

| Distraction | 1/59 (0.02) |

| Rest | 4/59 (0.07) |

-

Temperature therapy refers to using either cold or heat to alleviate pain by applying a temperature source, such as a heating pad, directly to an affected area. Foot bath refers to the placement of feet in heated water. Solicitude refers to parental attentiveness and emotional support. Distraction refers to shifting one’s focus away from pain and towards other activities or thoughts. Rest refers to discontinuing work or movement to facilitate relaxation, sleep, or recuperation of physical and mental stamina.

Distribution of pain coping interventions used for 59 children with cerebral palsy that experience everyday pain.

41/59 (0.70) did not receive physician-prescribed pain-relieving pharmacological interventions, and 16/59 (0.27) subjects had pain-relieving interventions prescribed by a physician. 40/59 (0.68) parents indicated that they wanted further evaluation and intervention for their child. 48/59 (0.81) parents stated that their child could verbalize their pain and be able to identify pain location. The pain had a negative impact on their everyday life in 44/59 (0.75) when evaluated by their parents.

Pain intensity

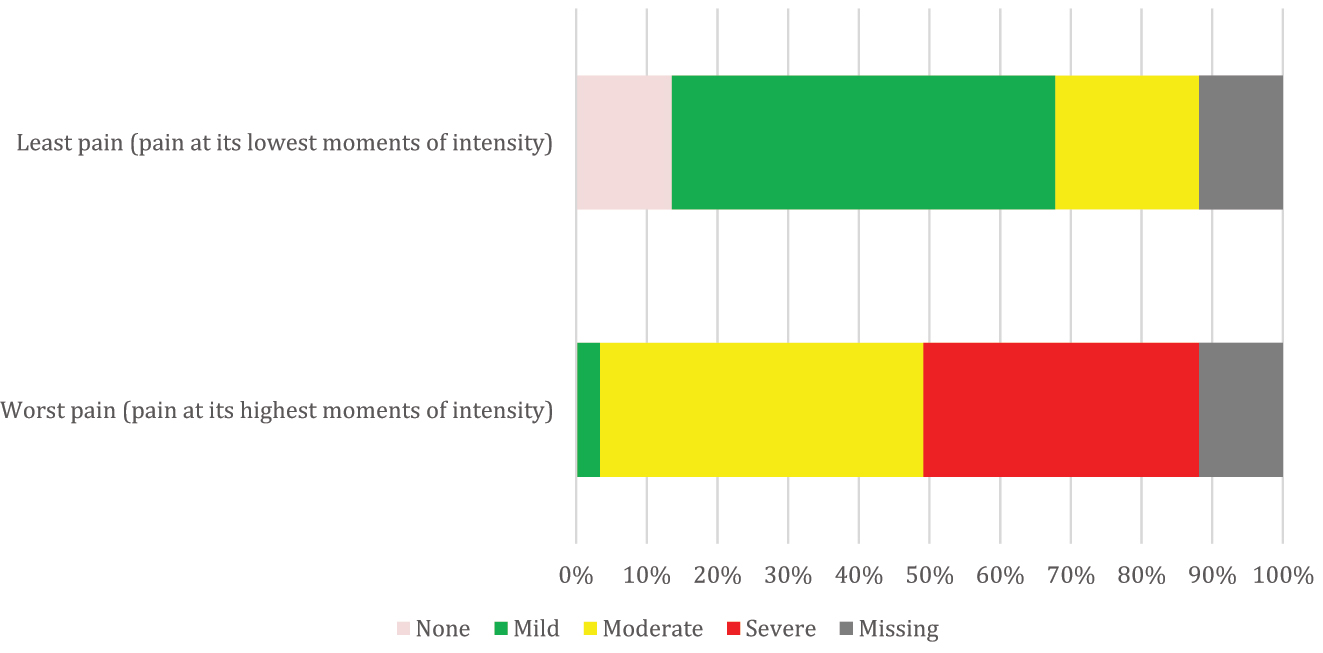

The parental evaluation of categorical pain intensity is illustrated in Figure 2. Out of those with pain in their everyday life, 43/59(0.73) experienced it during procedures and activities, with 41/59 (0.70) experiencing pain during physical activity, 4/59 (0.07) while sitting or sleeping, and 6/59 (0.10) during other activities such as using the computer, doing homework, mental fatigue, fasting, using new shoes, or being without an orthosis.

The categorization of pain intensity by parental evaluation of 59 children with cerebral palsy and everyday pain. We defined least pain as the lowest momentary pain intensity experienced, and worst pain as the highest momentary pain intensity experienced during pain. A numerical rating scale was used to grade the pain intensity of both the least pain and the worst pain, with 0 indicating no pain, 1–3 indicating mild pain, 4–7 indicating moderate pain, and 8–10 indicating severe pain.

The modified PMI and grouped PMI

The evaluation of the modified PMI showed that 8/59 (0.14) subjects with pain in their everyday life had an adequate PMI score of 0. 0/59 (0.00) had a positive PMI score of 1–3. 44/59 (0.75) had a negative PMI score. This was distributed as 25/59 (0.42) subjects with a score of −1, 16/59 (0.27) with −2, and 3/59 (0.05) with −3. The grouped PMI is shown in Table 3.

The modified pain management index (PMI) grouped for 59 children with cerebral palsy that experience everyday pain. The PMI was categorized into 4 groups depending on the adequacy of pain management during pain intensity experienced at its highest moments (worst pain) combined with pain intensity experienced at its lowest moments (least pain). Least pain was differentiated using the numeric rating scale (NRS) score of 0–2 (desirable) or 3–10 (undesirable). We graded least pain as desirable when the NRS score was between 0-2 due to this being seen as the desired goal for pain management among patients. This grouping was used to evaluate the effectiveness of pain interventions used, with a higher PMI group indicating better pain management.

| Grouped PMI | Number of subjects (as fractions) |

|---|---|

| 1. Inadequate pain management & undesirable least pain: | 19/59 (0.32) |

| 2. Adequate pain management & undesirable least pain: | 4/59 (0.07) |

| 3. Inadequate pain management & desirable least pain: | 25/59 (0.42) |

| 4. Adequate pain management & desirable least pain: | 4/59 (0.07) |

-

PMI, pain management index. Data was missing for 7.

Pain frequency

Parents of 59/115 (0.51) children reported pain in their everyday life. 49/115 (0.43) experienced pain within the latest week and 58/115 (0.50) experienced pain within the last three months.

Anatomical pain distribution

The distribution of pain in relation to anatomical location is shown in Figure 3, with a majority of subjects having lower extremity pain.

Distribution of anatomical location of pain of 59 children with cerebral palsy by parental evaluation. Parents were able to select multiple pain locations.

Comparison with data from the CPOP

There were no significant differences between both sex (P: 0.12) and GMFCS levels (P: 0.53) of our study population and those from the national CP registry, respectively.

Discussion

In this study, more than half of the children with CP in our region reported that they experienced chronic pain by parental proxy. Among those, about three-quarters were evaluated to be undertreated for their pain. Likewise, one-third were impacted by pain felt at both its highest and lowest moments of intensity. The majority who were in pain received alleviation through pharmacological and/or non-pharmacological interventions, with only a quarter using no pain interventions. The majority of parents of those in pain expressed a desire for further medical examination, while almost three-quarters of parents reported that the pain had a negative impact on their child’s daily living.

Based on the definition of chronic pain by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), the fact that four-fifths with everyday pain experienced pain within the last week and 58 out of 59 experienced it within the last 3 months in this study indicates that their pain is indeed recurrent and chronic in nature [14, 19]. This sheds a light on an alarming clinical problem for children with CP, that in our opinion needs urgent attention in the medical community since pain is the primary determinant for reduced quality of life, missed school days, less participation in activities, and reduced ambulation [1, 5, 6, 20].

Previous studies have proposed that there exists a misconception among children with CP, their parents, and their treating physicians that pain is an unavoidable part of the disease itself, thus being inadequately or untreated and leaving the children to resign to living with pain [8, 21]. Our results suggest this as well throughout our region. Out of necessity, parents turn to undocumented and perhaps ineffective pain-coping interventions [10].

In our study, more than half utilized non-pharmacological and “complementary therapies” of massage, physiotherapy, or other conservative modalities, whereas pharmacological pain interventions were utilized less frequently. For pharmacological pain interventions, paracetamol was almost exclusively used as monotherapy instead of other prescription medicine, and we interpret the use of paracetamol as an over-the-counter medication without a prescription. Besides paracetamol, other nonopioid analgesic groups are often used for pain management in children with CP such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID), anticonvulsants such as gabapentin, and muscle relaxants such as baclofen [5, 9]. However, evidence of their effectiveness in treating pain in children, in particular with CP, is lacking, and many of these medications can cause potentially debilitating side effects, which complicates the implementation of them into straightforward pain management algorithms [5, 9, 17]. Of note, NSAIDs can potentially cause a variety of side effects, with gastrointestinal issues being a source of concern [22]. This is especially problematic as children with CP are already burdened with a high prevalence of gastrointestinal problems [23]. In our study, no instances of antispasmodic usage for pain were reported, which we interpret as possibly due to parents not viewing it as a pain-coping intervention. About half of the parents of children with CP in pain reported lessened pain after massage therapy. Pediatric massage therapy has been shown to decrease hypertonicity in those with CP, alleviating those with chronic pain conditions and subsequently lowering anxiety and depression [10, 24]. Almost one-fifth also described pain relief from other conservative initiatives such as seeking solicitude or distraction. Our findings indicate the need for professional implementation of complementary therapies in everyday pain management.

Three-quarters of those with everyday pain were evaluated to be inadequately treated. One-third in pain had both an inadequate pain treatment at the highest moments of pain intensity while also having an undesirable intensity of pain at its lowest moments. We find that this subset of children with bothersome pain felt regardless of pain fluctuations are particularly important to identify and treat.

We acknowledge that our study does have limitations. Firstly, our response rate of approximately two-fifths could give rise to a participation bias where the response to our questionnaire was more likely from those with pain in their everyday life. Investigating the group of non-responders could potentially have affected our results regarding pain. Our subjects were chosen as a convenience sample, thus our study could be influenced by selection bias from both factors. Although, for sex and GMFCS level, we found no significant difference between our cohort and that of the Danish national CP registry. This suggests that our study sample is representative of children with CP in our country. In the group of children that responded to our questionnaire by parental proxy, we found that older age, female sex, and increased GMFCS level did not have a significant impact on pain which has been suggested in some earlier studies [1, 5, 20, 25, 26]. Our overall pain prevalence in this study is comparable to methodically similar contemporary studies done approximately within the same age range as ours with findings between 42.5 and 49.6 percent [1, 25, 26], though a comparison of pain prevalence between studies is difficult due to study method disparities; in particular with differences in age groups and pain definitions [20]. Although we used responses from proxy reporting this should not influence our results [25]. Since our focus was evaluating the actual management of pain in children with CP, we explored a method to describe and evaluate the adequacy of the pain interventions used. Our modified PMI is limited in its approach to pain treatment in CP children as opioids of any type are determined as the appropriate analgesic for severe pain which should be prescribed within the principles of opioid stewardship [17]. As stated by WHOs’ guidelines for the management of chronic pain in children, opioids are usually indicated for terminal care and must be prescribed with a clear tapering plan [17]. Likewise, the hierarchical order of pain management in children is difficult to assess with evidence of pharmacological management being of low certainty evidence in comparison to the evidence of non-pharmacological pain interventions such as physical therapy (very low certainty evidence) and psychological therapy (moderate certainty evidence) [17]. Incorporation of non-pharmacological interventions in a pain ladder together with pharmacological interventions is challenging. The closest example would be WHO’s revised analgesic three-step ladder which added a bidirectional fourth step with interventional and minimally invasive procedures [27]. As such, our suggestion for pain management in children with CP is for an increased focus on psychological therapy, based on WHO’s moderately evidence-based recommendation [17]. Additionally, massage therapy has also shown promising results [10, 24]. It would also be beneficial for more healthcare providers to become aware of WHO’s guidelines for chronic pain management in children, which recommends implementing both non-pharmacological and pharmacological interventions together as part of a biopsychosocial model for pain management [17]. Moreover, the modification of the PMI was intended to provide a more comprehensive description of the pain management interventions actually used by parents, and to better assess their effectiveness in managing pain in children.

In conclusion, chronic pain is a prevalent issue for children with cerebral palsy, with approximately half of the children in our region experiencing everyday pain. Pain affected daily living for almost three-quarters of those in pain. The majority used pharmacological and non-pharmacological pain interventions with massage therapy and paracetamol being the most utilized. By our evaluation, pain management was inadequate for three-quarters of those in pain. Likewise, one-third of those in pain were impacted by their pain at both its highest and lowest moments of intensity. Increased awareness of pain management is warranted for children with CP.

-

Research funding: Authors state no funding involved for this study.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflicts of interests: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

-

Ethics approval: Research involving human subjects complied with all relevant national regulations, institutional policies and is in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration (as amended in 2013) and has been approved by The Regional Committee of Health Research Ethics (Protocol number H-17008823) as a clinical quality study and the subjects were enrolled after appropriate informed consent from the parents.

References

1. Eriksson, E, Hägglund, G, Alriksson-Schmidt, AI. Pain in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy - a cross-sectional register study of 3545 individuals. BMC Neurol 2020;20:15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-019-1597-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. van Eck, M, Dallmeijer, AJ, Beckerman, H, van den Hoven, PAM, Voorman, JM, Becher, JG. Physical activity level and related factors in adolescents with cerebral palsy. Pediatr Exerc Sci 2008;20:95–106. https://doi.org/10.1123/pes.20.1.95.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Pavão, SL, Rocha, NACF. Sensory processing disorders in children with cerebral palsy. Infant Behav Dev 2017;46:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2016.10.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Parkinson, KN, Dickinson, HO, Arnaud, C, Lyons, A, Colver, A. SPARCLE group. Pain in young people aged 13 to 17 years with cerebral palsy: cross-sectional, multicentre European study. Arch Dis Child 2013;98:434–40. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2012-303482.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Michelsen, JS, Normann, G, Wong, C. Analgesic effects of botulinum toxin in children with CP. Toxins 2018;10:162. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins10040162.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Whitney, DG, Warschausky, SA, Peterson, MD. Mental health disorders and physical risk factors in children with cerebral palsy: a cross-sectional study. Dev Med Child Neurol 2019;61:579–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.14083.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Albayrak, I, Biber, A, Çalışkan, A, Levendoglu, F. Assessment of pain, care burden, depression level, sleep quality, fatigue and quality of life in the mothers of children with cerebral palsy. J Child Health Care 2019;23:483–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493519864751.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Blackman, JA, Svensson, CI, Marchand, S. Pathophysiology of chronic pain in cerebral palsy: implications for pharmacological treatment and research. Dev Med Child Neurol 2018;60:861–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.13930.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Ostojic, K, Paget, SP, Morrow, AM. Management of pain in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol 2019;61:315–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.14088.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Flyckt, N, Wong, C, Michelsen, JS. Non-pharmacological and non-surgical treatment of pain in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: a scoping review. J Pediatr Rehabil Med 2022;15:49–67. https://doi.org/10.3233/PRM-210046.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Deandrea, S, Montanari, M, Moja, L, Apolone, G. Prevalence of undertreatment in cancer pain. A review of published literature. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol 2008;19:1985–91. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdn419.Search in Google Scholar

12. Cleeland, CS, Gonin, R, Hatfield, AK, Edmonson, JH, Blum, RH, Stewart, JA, et al.. Pain and its treatment in outpatients with metastatic cancer. N Engl J Med 1994;330:592–6. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199403033300902.Search in Google Scholar

13. Ward, SE, Carlson-Dakes, K, Hughes, SH, Kwekkeboom, KL, Donovan, HS. The impact on quality of life of patient-related barriers to pain management. Res Nurs Health 1998;21:405–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199810)21:5<405::aid-nur4>3.0.co;2-r.10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(199810)21:5<405::AID-NUR4>3.0.CO;2-RSearch in Google Scholar

14. Riquelme, I, Cifre, I, Montoya, P. Age-related changes of pain experience in cerebral palsy and healthy individuals. Pain Med 2011;12:535–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01094.x.Search in Google Scholar

15. Stone, AA, Broderick, JE, Goldman, RE, Junghaenel, DU, Bolton, A, May, M, et al.. I. Indices of pain intensity derived from ecological momentary assessments: rationale and stakeholder preferences. J Pain 2021;22:359–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2020.08.003.Search in Google Scholar

16. Schneider, S, Junghaenel, DU, Broderick, JE, Ono, M, May, M, Stone, AA. II. Indices of pain intensity derived from ecological momentary assessments and their relationships with patient functioning: an individual patient data meta-analysis. J Pain 2021;4:371–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2020.10.002.Search in Google Scholar

17. World Health Organization. Guidelines on the management of chronic pain in children; 2020. Available from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240017870 [Accessed 17 Mar 2023].Search in Google Scholar

18. Johansen, M. CPOP databasen: landsdækkende klinisk kvalitetsdatabase for opfølgningsprogrammet for cerebral parese (CPOP); 2018. Available from https://cpop.dk/wp-content/uploads/61307_cpop-databasen-aarsrapport-2018-offentliggjort.pdf [Accessed 17 Mar 2023].Search in Google Scholar

19. Treede, RD, Rief, W, Barke, A, Aziz, Q, Bennett, MI, Benoliel, R, et al.. Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: the IASP classification of chronic pain for the international classification of diseases (ICD-11). Pain 2019;160:19–27. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001384.Search in Google Scholar

20. Mckinnon, CT, Meehan, EM, Harvey, AR, Antolovich, GC, Morgan, PE. Prevalence and characteristics of pain in children and young adults with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol 2019;61:305–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.14111.Search in Google Scholar

21. Chaleat-Valayer, E, Roumenoff, F, Bard-Pondarre, R, Ganne, C, Verdun, S, Lucet, A, et al.. Pain coping strategies in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 2019;61:1329–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.14204.Search in Google Scholar

22. Bianciotto, M, Chiappini, E, Raffaldi, I, Gabiano, C, Tovo, PA, Sollai, S, et al.. Drug use and upper gastrointestinal complications in children: a case-control study. Arch Dis Child 2013;98:218–21. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2012-302100.Search in Google Scholar

23. Trivić, I, Hojsak, I. Evaluation and treatment of malnutrition and associated gastrointestinal complications in children with cerebral palsy. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr 2019;22:122–31. https://doi.org/10.5223/pghn.2019.22.2.122.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Field, T. Pediatric massage therapy research: a narrative review. Children 2019;6:78. https://doi.org/10.3390/children6060078.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Hägglund, G, Burman-Rimstedt, A, Czuba, T, Alriksson-Schmidt, AI. Self-versus proxy-reported pain in children with cerebral palsy: a population-based registry study of 3783 children. J Prim Care Community Health 2020;11: 2150132720911523. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150132720911523.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Penner, M, Xie, WY, Binepal, N, Switzer, L, Fehlings, D. Characteristics of pain in children and youth with cerebral palsy. Pediatrics 2013;132:e407–13. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-0224.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Pugh, TM, Squarize, F, Kiser, AL. A comprehensive strategy to pain management for cancer patients in an inpatient rehabilitation facility. Front Pain Res (Lausanne) 2021;2:688511. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpain.2021.688511.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/sjpain-2022-0124).

© 2023 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Systematic Review

- Comparison of the effectiveness of eHealth self-management interventions for pain between oncological and musculoskeletal populations: a systematic review with narrative synthesis

- Topical Review

- Shifting the perspective: how positive thinking can help diminish the negative effects of pain

- Clinical Pain Researches

- Pain acceptance and psychological inflexibility predict pain interference outcomes for persons with chronic pain receiving pain psychology

- A feasibility trial of online Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for women with provoked vestibulodynia

- Relations between PTSD symptom clusters and pain in three trauma-exposed samples with pain

- Short- and long-term test–retest reliability of the English version of the 7-item DN4 questionnaire – a screening tool for neuropathic pain

- Chronic post-thoracotomy pain after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study of preoperative risk factors

- Pain sensitivity after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass – associations with chronic abdominal pain and psychosocial aspects

- Barriers in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) management: perspectives from health practitioners

- Observational studies

- Spontaneous self-affirmation: an adaptive coping strategy for people with chronic pain

- COVID-19 and processes of adjustment in people with persistent pain: the role of psychological flexibility

- Presence and grade of undertreatment of pain in children with cerebral palsy

- Sex-related differences in migraine clinical features by frequency of occurrence: a cross-sectional study

- Recurrent headache, stomachache, and backpain among adolescents: association with exposure to bullying and parents’ socioeconomic status

- Original Experimentals

- Temporal stability and responsiveness of a conditioned pain modulation test

- Anticipatory postural adjustments mediate the changes in fear-related behaviors in individuals with chronic low back pain

- The role of spontaneous vs. experimentally induced attentional strategies for the pain response to a single bout of exercise in healthy individuals

- Acute exercise of painful muscles does not reduce the hypoalgesic response in young healthy women – a randomized crossover study

- Short Communications

- Nation-wide decrease in the prevalence of pediatric chronic pain during the COVID-19 pandemic

- A multidisciplinary transitional pain service to improve pain outcomes following trauma surgery: a preliminary report

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Systematic Review

- Comparison of the effectiveness of eHealth self-management interventions for pain between oncological and musculoskeletal populations: a systematic review with narrative synthesis

- Topical Review

- Shifting the perspective: how positive thinking can help diminish the negative effects of pain

- Clinical Pain Researches

- Pain acceptance and psychological inflexibility predict pain interference outcomes for persons with chronic pain receiving pain psychology

- A feasibility trial of online Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for women with provoked vestibulodynia

- Relations between PTSD symptom clusters and pain in three trauma-exposed samples with pain

- Short- and long-term test–retest reliability of the English version of the 7-item DN4 questionnaire – a screening tool for neuropathic pain

- Chronic post-thoracotomy pain after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study of preoperative risk factors

- Pain sensitivity after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass – associations with chronic abdominal pain and psychosocial aspects

- Barriers in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) management: perspectives from health practitioners

- Observational studies

- Spontaneous self-affirmation: an adaptive coping strategy for people with chronic pain

- COVID-19 and processes of adjustment in people with persistent pain: the role of psychological flexibility

- Presence and grade of undertreatment of pain in children with cerebral palsy

- Sex-related differences in migraine clinical features by frequency of occurrence: a cross-sectional study

- Recurrent headache, stomachache, and backpain among adolescents: association with exposure to bullying and parents’ socioeconomic status

- Original Experimentals

- Temporal stability and responsiveness of a conditioned pain modulation test

- Anticipatory postural adjustments mediate the changes in fear-related behaviors in individuals with chronic low back pain

- The role of spontaneous vs. experimentally induced attentional strategies for the pain response to a single bout of exercise in healthy individuals

- Acute exercise of painful muscles does not reduce the hypoalgesic response in young healthy women – a randomized crossover study

- Short Communications

- Nation-wide decrease in the prevalence of pediatric chronic pain during the COVID-19 pandemic

- A multidisciplinary transitional pain service to improve pain outcomes following trauma surgery: a preliminary report