The role of spontaneous vs. experimentally induced attentional strategies for the pain response to a single bout of exercise in healthy individuals

-

Christina Titze

Abstract

Objectives

Exercise-induced pain and exercise-induced hypoalgesia (EIH) are well described phenomena involving physiological and cognitive mechanisms. Two experiments explored whether spontaneous and instructed mindful monitoring (MM) were associated with reduced exercise-induced pain and unpleasantness, and increased EIH compared with spontaneous and instructed thought suppression (TS) in pain-free individuals.

Methods

Eighty pain-free individuals participated in one of two randomized crossover experiments. Pressure pain thresholds (PPTs) were assessed at the leg, back and hand before and after 15 min of moderate-to-high intensity bicycling and a non-exercise control condition. Exercise-induced pain and unpleasantness were rated after bicycling. In experiment 1 (n=40), spontaneous attentional strategies were assessed with questionnaires. In experiment 2, participants (n=40) were randomly allocated to use either a TS or MM strategy during bicycling.

Results

In experiment 1, the change in PPTs was significantly larger after exercise compared with quiet rest (p<0.05). Higher spontaneous MM was associated with less exercise-induced unpleasantness (r=−0.41, p<0.001), whereas higher spontaneous TS was associated with higher ratings of exercise-induced unpleasantness (r=0.35, p<0.05), but not with pain intensity or EIH. In experiment 2, EIH at the back was increased in participants using instructed TS compared with participants using instructed MM (p<0.05).

Conclusions

These findings suggest that spontaneous and presumably habitual (or dispositional) attentional strategies may primarily affect cognitive-evaluative aspects of exercise, such as feelings of exercise-induced unpleasantness. MM was related to less unpleasantness, whereas TS was related to higher unpleasantness. In terms of brief experimentally-induced instructions, TS seems to have an impact on physiological aspects of EIH; however, these preliminary findings need further research.

Introduction

Exercise is often accompanied by muscle pain [1, 2] in pain-free individuals and a significant increase in pain in some individuals with chronic pain [3, 4]. On the other hand, exercise has been linked to a reduced sensitivity to pain, a phenomenon denoted as exercise-induced hypoalgesia (EIH) [5, 6]. EIH has therefore become an increasingly important paradigm in pain research, with potential application in clinical practice [7]. The mechanisms underlying exercise-induced pain and EIH are not fully understood, but literature indicates the involvement of both central and peripheral physiological mechanisms [8], [9], [10]. Recently, evidence has emerged that exercise-induced pain and EIH might also be linked to cognitions suggested to modulate attention directed to pain [11]. Yet, very little is known about the influence of different attentional strategies on exercise-induced pain and EIH.

Thought suppression (TS), one of the most common strategies to react to pain [12], is the attempt to simply not think about aversive thoughts or sensations such as pain, resulting in an unfocused and disorganized search for distraction. TS often fails to succeed and paradoxically leads to increased aversive thoughts or sensations [13]. For experimentally induced TS, detrimental effects on pain experience have been observed, with increased pain ratings [14], reduced pain tolerance [14, 15], and slower recovery from laboratory pain [14, 16] in pain-free individuals. Moreover, clinical studies observed a positive association of spontaneous and presumably habitual pain-related TS with pain intensity and pain-related disability [12, 17] as well as a mediating role of spontaneous pain-related TS between pain and depression [18].

A strategy opposing TS is mindful monitoring (MM). MM includes a focus on sensations (monitoring) and a purposeful and acceptance-based awareness [19]. Regarding pain, MM comprises paying attention to pain in an accepting and non-judgmental way [20]. Although, in contrast to TS, MM is a rather counterintuitive response to pain, a number of studies have shown that MM reduces pain sensations [15, 21], [22], [23], [24], [25]. MM directs limited attentional resources to sensory aspects of pain and may thereby decrease the capacity for negative emotional evaluation of pain [24, 26].

None of the existing studies has, however, explored whether self-reported spontaneous and experimentally induced (“instructed”) TS and MM are associated with exercise-induced pain and EIH. Investigating different attentional strategies may contribute to a better understanding of the experience of pain during and after exercise and shed light on factors intervening with the pain modulatory systems. Moreover, modulating attentional strategies [24] might be a promising treatment approach to reduce pain during exercise and to increase EIH. The main objectives of this study were therefore to explore the associations of spontaneous and instructed TS vs. spontaneous and instructed MM with exercise-induced pain and EIH in pain-free individuals. We expected that spontaneous and instructed MM were associated with reduced exercise-induced pain and increased EIH compared with TS.

Methods

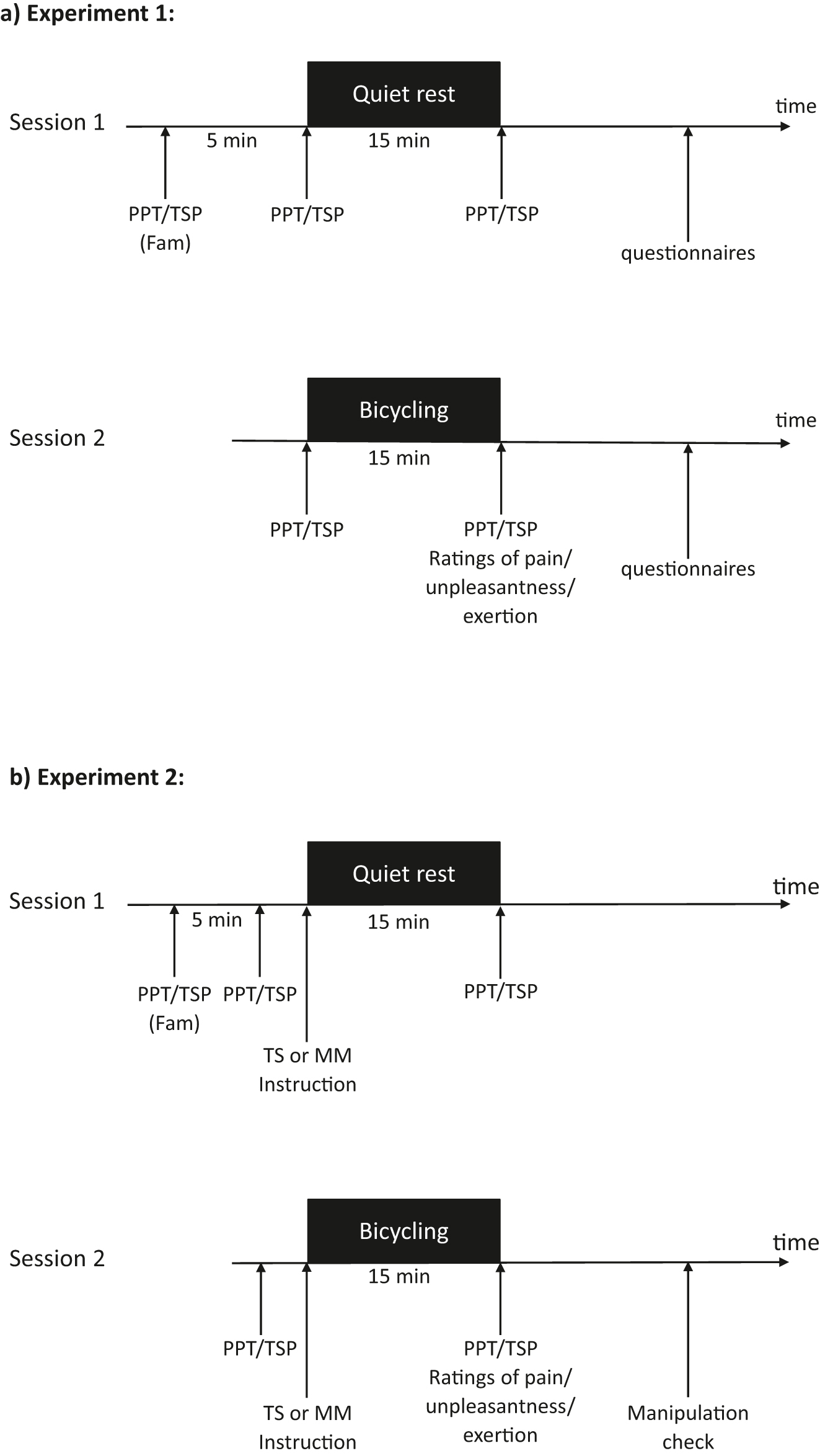

Two experiments were performed to explore the associations of spontaneous and instructed pain-related TS and MM with exercise-induced pain and EIH in relation to a single bout of aerobic exercise. In total, 80 pain-free individuals were included. All individuals participated in two sessions (Figure 1) approximately at the same time of the day and separated by 2–4 weeks. In both experiments, ratings of exercise-induced pain and unpleasantness were reported immediately following bicycling. EIH was primarily assessed using pressure pain thresholds (PPTs) and – rather exploratory – with temporal summation of pain before and after a non-exercise condition (i.e. quiet rest, session 1) and the bicycling condition (session 2). In experiment 1, spontaneous TS and MM were assessed with questionnaires in 40 pain-free individuals (mean age: 28.1 ± 10.6 years; 22 women); in experiment 2, 40 pain-free individuals (mean age 27.3 ± 4.8 years; 19 women) received instructions to use either TS or MM during quiet rest and bicycling.

Timeline of the experimental procedures illustrated for a) experiment 1 and b) experiment 2. PPT, assessment of pressure pain thresholds at the leg, the back and the hand; TSP, assessment of temporal summation of pain at the leg, the back and the hand; Fam, familiarization period; TS, Thought suppression; MM, mindful monitoring.

Individuals were recruited by advertisement at the University, word of mouth and social media. Before participating in this study, all interested individuals were screened during a telephone interview to assess exclusion criteria and to give further information on the purpose of the study. None of the included subjects suffered from neurological, psychological, cardiovascular diseases, had a body mass index above 30, had any pain or used any pain medication (both, over-the-counter and prescription medication) during the week prior to participation. All subjects were asked to refrain from physical exercises, alcohol, and nicotine on the days of participation and the day before participation. The studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent. Participants were rewarded with either 20 euros or credit toward a psychology course requirement for their participation.

Assessment of PPTs and temporal summation of pain

PPTs and temporal summation of pain were assessed at (1) the middle of the biceps femoris of the non-dominant leg, (2) the non-dominant side of the lower back approximately 2 cm adjacent to the spine at the level of the 2nd lumbar vertebra, and (3) the thenar eminence of the non-dominant hand using a handheld algometer (Algometer type II, SOMEDIC Electronics, Solna, Sweden) with a probe surface of 1 cm2. These assessment sites were selected as they were all accessible with the participant lying in prone position, preventing a risk of bias caused by rearranging the participant during the pain assessment procedure. The assessment sites have further been investigated in previous studies on EIH [27], [28], [29]. Handedness was identified using the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory [30]. To identify leg dominance, participants underwent a short destabilization test during which they were pushed forward, and the leg moved to regain balance was determined as the dominant leg. Leg dominance also determined the dominant side of the back. To assess PPTs, pressure was constantly increased at an approximate rate of 50 kPa/s. Participants were asked to say ‘stop’ as soon as they perceived the pressure stimulus as slightly painful, and the achieved pressure intensity was determined as the PPT. PPT was assessed twice at each site in randomized and counterbalanced order, separated by a 20 s interval. The mean of both measurements was used for the statistical analyses. To assess temporal summation of pain, pressure was applied 10 times at an intensity of the respective mean PPT at each of the sites [31]. Participants were instructed to rate the intensity of the pressure stimulus immediately after the first and the 10th stimulation on a scale from 0 (“no pain at all”) to 10 (“worst pain imaginable”). Temporal summation of pain was then calculated for each site as the absolute difference between the 10th minus the first pressure pain rating values. Thus, higher values indicate larger temporal summation of pain. The experimenters performing the pain sensitivity assessments were blinded to questionnaire scores (experiment 1) and experimental group assignment (experiment 2).

Exercise and non-exercise control conditions

The conditions of exercise and quiet rest were always conducted in the same order, with quiet rest in the first and exercise in the second session. The first session started with a familiarization period during which the participants were introduced to the procedures of the pain sensitivity assessments.

Quiet rest (control condition): After a five-minute recovery interval to avoid any carry-over effect from the familiarization procedures, 15 min of quiet rest were performed with participants sitting quietly on a chair. During quiet rest, the investigators remained in the room (to create conditions comparable to the exercise task), preparing the following tasks. Investigators did not talk to the participant to avoid distraction.

Bicycling (exercise condition): During the second session, participants underwent a 15 min aerobic cycling exercise using a stationary cycle (Corival cpet, Lode BV, Groningen, Netherlands) with included heart rate monitor. Seat height was individually adjusted to a knee bend of approximately 5° during the bottom phase of the pedal stroke. The cycling protocol used in this study was a slightly modified version of the heart rate-controlled protocol used by Vaegter et al. [32], [33], [34] which had previously been shown to produce robust EIH. Prior to the cycling exercise, the target heart (HR) of 85.9 % of age-related maximum HR was individually calculated for each participant [(220 − age) * 0.859]. This heart rate has previously been shown to correspond to 75 % of maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) [35] an intensity which has been shown sufficient to elicit EIH [5]. Participants were instructed to maintain a pedal rate of approximately 70 rounds per minute for the entire exercise. Pedal rate was displayed on the monitor of the ergometer. However, all other data including pace, time, intensity and heart rate were covered, to avoid further distraction from the instructed strategy (in experiment 2). After 2 min of warm-up, the resistance was increased, to achieve the target heart rate which was assessed with a heart rate monitor (Polar T31, Polar Electro, Kempele, Finland) after a total of 5 min. For the following 10 min the participants continued bicycling at the level of the target heart rate with the resistance being adapted, if necessary. Immediately after the exercise was completed, participants rated their current level of perceived exertion on a Borg scale from 6 (“very, very light”) to 20 (“very, very hard”) [36] as well as exercise-induced pain and unpleasantness due to the aerobic cycling exercise, each on a scale from 1 (not at all), 2 (little), 3 (moderate), 4 (considerable) to 5 (very high).

Experiment 1: spontaneous thought suppression and mindful monitoring

Spontaneous pain-related TS was assessed using the Thought Suppression Subscale of the Avoidance-Endurance Questionnaire (AEQ-TSS) [12]. The subscale comprises four items describing self-directed speech to suppress occurring pain sensations or pain-related thoughts (e.g. “Pull yourself together” and “I tell myself: I don’t have time for this right now!”) with responses ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (always). The score is calculated as the mean of the 4 items, with higher scores indicating more pronounced pain-related TS. The reliability and validity have been shown [12].

Generic TS was assessed using the White Bear Suppression Inventory (WBSI) [37]. The sum of the 15 items (e.g. “I often have thoughts that I try to avoid” and “I often do things to distract myself from my thoughts”) with responses from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree) ranges from 15 to 75 with higher scores indicating greater tendencies to suppress thoughts. The reliability and validity have previously been established [37].

Spontaneous MM was assessed with the Non-Judgmental Inner Critic subscale of the German version [38] of the 39 items Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) [39, 40]. The subscale comprises 8 items (e.g. “I criticize myself for having irrational or inappropriate emotions” and “I make judgements about whether my thoughts are good or bad”). The responses range from 1 (never or very rarely true) to 5 (Very often or always true). After inversion of all subscale scores, higher scores indicating more pronounced MM. The reliability and validity have previously been established and negative associations of this subscale with the WBSI in a student’s sample (r=−0.56, p<0.001) has been reported [41, 42].

The FFMQ and the WBSI were completed after the assessment of PPTs and temporal summation of pain following quiet rest; the AEQ was completed after the assessment of PPTs and temporal summation of pain following exercise. In the questionnaires, participants were asked to focus on occasional pain in daily life.

Experiment 2: instructed thought suppression and mindful monitoring

Randomization

The randomization sequence (1:1 group allocation) was distributed and stored in sealed opaque envelopes handled only by one experimenter who after group allocation delivered the instructions for the allocated attentional strategy. This experimenter was not involved in the exercise condition or the assessment of pain sensitivity. All outcome measurements (pain sensitivity and ratings) were done by another experimenter who was unaware of the participants’ group allocation at all time.

Attentional strategies

In line with and based on research on TS and MM [21, 26, 43], [44], [45], [46], we used short instructions for the attentional strategies. According to the assigned group, participants received instructions to use the respective attentional strategy during quiet rest and bicycling.

Instructions for TS: (1) Quiet rest: “During the following 15 min, please sit relaxed and quietly. In doing so, unpleasant sensations may arise. It is very important that you try as much as you can to not think about unpleasant thoughts or sensations. In other words, suppress or ignore any unpleasant thoughts and sensations, such as the pain during the pain assessment. Put them right out of your mind. Focus on ignoring these thoughts.” (2) Exercise: “During the following exercise, unpleasant sensations may arise. It is very important that you try as much as you can to not think about unpleasant thoughts or sensations. In other words, suppress or ignore any unpleasant thoughts or sensations. For example, do not think about pain, your heartbeat, sweating, stabbing or dragging pain in your muscles. Put them right out of your mind. Focus on ignoring these thoughts.”

Instructions for MM: (1) Quiet rest: “During the following 15 min, please sit relaxed and quietly. In doing so, unpleasant sensations may arise. It is very important that you try to fully perceive your sensations objectively, without judgment. In other words, focus on your sensations, such as the pain during the pain assessment, and consciously observe the location, the quality and the intensity of the sensations. Be open minded and even focus without judgment on unpleasant sensations without trying to avoid, control or change them.” (2) Exercise: “During the following exercise, unpleasant sensations may arise. It is very important that you try to fully perceive your sensations objectively, without judgment. In other words, focus on your sensations, such as pain, your heartbeat or sweating, and consciously observe the location, the quality and the intensity of the sensations, such as stabbing or dragging pain in your muscles. Be open minded and even focus without judgment on unpleasant sensations without trying to avoid, control or change them.”

Afterwards, participants were asked if the instruction was clear to them, giving them the possibility to ask questions.

A manipulation check was designed to assess the degree to which participants in the instructed TS or instructed MM groups had used the respective attentional strategy during exercise. Participants completed the manipulation check after the last pain sensitivity assessment, which followed the exercise condition. The manipulation check consisted of six items, with three items each assessing the degree of instructed TS and instructed MM (for example “How hard did you try to ignore unpleasant thoughts and sensations during the exercise?”/“How hard did you try to stop pain-related thoughts?” or “How hard did you try to observe unpleasant thoughts and sensations consciously?”/“How hard did you try to perceive quality and intensity of your sensations?”.) [47]. Participants used rating scales from 1 (not at all) to 5 (completely/highly). For both subscales, scores were summed and averaged. Moreover, participants were asked to evaluate the strategy (“How difficult was it to follow the instructions?”, “How useful was the strategy in reducing unpleasant thoughts and sensations?”, “How successful did you reduce unpleasant thoughts and sensations?”). All items were scored on a rating scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (completely/highly). As the manipulation check was filled in online and therefore anonymous, the risk of trying to please the examiner by giving biased answers was reduced.

Statistics

Results are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD). With a power of 0.80, α≤0.05 and large effect sizes based on a previously reported correlation of r=0.47 between EIH and a spontaneous cognitive variable [48], we chose to include a sample size of n=40 participants in each of the two experiments.

Experiment 1: First, to examine whether EIH had been induced by the exercise condition compared to quiet rest, separate paired t-tests comparing absolute changes in PPTs (after minus before conditions) at each assessment site between quiet rest vs. exercise were performed and Cohen’s d effect sizes were calculated. Changes in temporal summation of pain scores after exercise were also explored. Associations between spontaneous (generic and pain-related) TS and MM with exercise-induced pain and unpleasantness, perceived exertion and EIH were explored with Pearson’s correlation coefficients. Subsequently, three hierarchical multiple linear regression analyses adjusting for age, gender, and exercise-induced pain were performed as exercise-induced unpleasantness revealed significant associations with each of the attentional strategies. Independence of errors was analyzed by visual inspection of residuals, homoscedasticity was analysed by Koenker’s robust version of the Breusch-Pagan test [49], multicollinearity between the predictor variables was analyzed by tolerance and variance inflation factors, and the existence of influential cases was calculated by Cook’s distance (distance<1).

Experiment 2: As a successful manipulation is the basis for this study, manipulation check scores of participants in the instructed TS or MM group were evaluated (subscales thought suppression and mindful monitoring). Participants were excluded, if they (on average) indicated to use the instructed attentional strategy less than or equal to “2” (with “1” meaning “not at all” and “5” corresponding to “completely/highly”). Moreover, participants were excluded if the average score of the opposing strategy was rated at or above “4”. To check the validity of the manipulation, comparisons of the instructed TS and MM group subscales (manipulation check) were calculated. Manipulation was determined as successful, if the respective group scored higher on the respective manipulation check subscale, compared to the other group. Next, independent student’s t-tests were used to compare the effect of instructed TS compared with the MM instruction on ratings of exercise-induced pain and unpleasantness, perceived exertion, and EIH at each assessment site. Finally, differences in the evaluation of the difficulty, usefulness and success of the attentional strategy during exercise were explored with independent t-tests. Effect sizes were calculated as the Cohen’s d. For both experiments, effect sizes were categorized as large (≥0.80), moderate (≥0.50 to <0.80) and small (≥0.20 to <0.50) using Cohen’s criteria (Cohen, 1988). All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (Version 25, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). p-Values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

All participants completed both sessions in experiment 1 and experiment 2. Descriptive statistics for the included participants are presented in Table 1. After finishing experiment 2, 6 participants were excluded from further analyses due to the results of the manipulation check. Men and women did not differ with respect to age, spontaneous attentional strategies and ratings of aerobic exercise (all p>0.05).

Means (standard deviations) of age, spontaneous attentional strategies, and ratings of exercise-induced pain, unpleasantness and exertion after the aerobic exercise condition of the total study sample, and separate for women and men in experiment 1 and 2.

| Experiment 1 | Experiment 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample (n=40) | Women (n=22, 55 %) | Men (n=18, 45 %) | Total sample (n=34) | Women (n=16, 47 %) | Men (n=18, 53 %) | |

| Age (in years) | 28.13 (10.56) | 27.23 (11.23) | 29.22 (9.90) | 27.00 (5.08) | 27.19 (6.00) | 26.83 (4.27) |

| Spontaneous attentional strategiesa | ||||||

| FFMQ non-judgemental inner critic (1–5) | 3.54 (0.60) | 3.48 (0.54) | 3.63 (0.69) | 3.37 (0.63) | 3.42 (0.69) | 3.33 (0.60) |

| AEQ pain-related thought suppression (0–6) | 2.83 (1.73) | 2.75 (1.67) | 2.92 (1.85) | 3.36 (1.45) | 3.53 (1.46) | 3.21 (1.47) |

| WBSI generic thought suppression (15–75) | 40.11 (13.75) | 42.86 (13.72) | 36.73 (13.77) | 41.38 (14.27) | 41.13 (15.43) | 41.61 (13.60) |

| Ratings of aerobic exerciseb | ||||||

| Exercise-induced pain intensity (1–5) | 2.15 (1.08) | 2.27 (1.03) | 2.00 (1.14) | 2.62 (0.92) | 2.81 (1.05) | 2.44 (0.78) |

| Exercise-induced unpleasantness (1–5) | 2.92 (1.21) | 3.05 (1.08) | 2.73 (1.39) | 3.44 (1.05) | 3.31 (1.25) | 3.56 (0.86) |

| Perceived exertion (Borg, 6–20) | 15.60 (1.50) | 15.59 (1.68) | 15.61 (1.29) | 15.56 (1.44) | 15.25 (1.53) | 15.83 (1.34) |

-

FFMQ, Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire; AEQ, Avoidance-Endurance Questionnaire; WBSI, White Bear Suppression Inventory.

Experiment 1: the effect of exercise on pain sensitivity

Data on PPTs and temporal summation of pain before and after quiet rest and exercise are presented in Table 2. T-tests for paired samples indicated significant differences in changes in PPTs after the exercise condition compared with quiet rest with moderate effect sizes (PPT back: t=2.86, p<0.01, Cohen’s d=0.45; PPT leg: t=2.98, p<0.01, Cohen’s d=0.46; PPT hand: t=2.43, p<0.05, Cohen’s d=0.38; Table 2). There were no significant differences in temporal summation of pain after exercise compared with quiet rest (all p>0.05, see also Table 2).

Experiment 1: Means (standard deviations) of pressure pain thresholds (PPTs) and pain intensity after the first and 10th stimulus of temporal summation of pain testing before and after aerobic exercise and quiet rest, separated for the locations leg, back and hand. ∆PPT is absolute change in PPT after quiet rest/exercise compared with before quiet rest/exercise.

| Quiet rest | Bicycling | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | ∆PPT | Pre | Post | ∆PPT | ||||||

| PPT | |||||||||||

| Experiment 1 n=40 |

Leg | 402.04 (146.35) | 385.98 (134.51) | −16.06 (71.99) | 433.36 (188.97) | 462.14 (211.03) | 28.78 (77.48)a | ||||

| Back | 423.06 (192.23) | 399.80 (165.72) | −23.26 (73.06) | 443.99 (209.53) | 465.56 (215.22) | 21.58 (57.54)a | |||||

| Hand |

287.25 (113.48) |

265.60 (100.15) |

−21.65 (55.22) |

285.80 (111.07) |

294.11 (110.09) |

8.31 (55.73)a |

|||||

|

Temporal summation

|

Stimulus 1

|

Stimulus 10

|

Stimulus 1

|

Stimulus 10

|

|

Stimulus 1

|

Stimulus 10

|

Stimulus 1

|

Stimulus 10

|

|

|

| Leg | 1.75 (1.24) | 3.93 (1.79) | 1.80 (1.32) | 4.00 (1.84) | 1.86 (1.38) | 3.70 (1.83) | 1.80 (1.26) | 3.30 (1.88) | |||

| Back | 1.90 (1.34) | 3.75 (1.92) | 1.78 (1.35) | 3.25 (1.86) | 1.85 (11.31) | 3.45 (1.92) | 1.70 (1.34) | 3.38 (2.05) | |||

| Hand | 2.28 (1.26) | 4.63 (2.06) | 2.35 (1.42) | 4.75 (1.99) | 2.03 (1.19) | 4.30 (1.95) | 2.08 (1.38) | 4.63 (2.10) | |||

-

ap<0.05.

Both exercise-induced pain (M=2.15, 95 % CI: 1.82 to 2.48) and exercise-induced unpleasantness (M=2.92, 95 % CI: 2.55 to 3.29) were rated as “little-to-moderate”, on average. Perceived exertion, on average, was rated as “hard” (M=15.60, 95 % CI: 15.13 to 16.06).

Spontaneous attentional strategies and their association with exercise-induced pain and unpleasantness, perceived exertion and EIH

Bivariate Pearson correlations between the attentional strategies and ratings of exercise-induced pain, unpleasantness, perceived exertion and EIH change scores (post exercise PPT – pre exercise PPT) are reported in Table 3. Significant associations with moderate effect sizes for all three attentional strategies were found for the unpleasantness rating: Higher spontaneous MM was associated with lower unpleasantness ratings. In contrast, higher scores for generic or pain-related spontaneous TS were associated with higher unpleasantness ratings. No significant correlations of spontaneous attentional strategies with exercise-induced pain, exertion or EIH were observed (all p>0.05, see also Table 3).

Experiment 1: Bivariate correlations of spontaneous attentional strategies with exercise-induced changes of pressure pain thresholds (PPT) and ratings of exercise-induced pain and unpleasantness.

| PPT change | Exercise ratings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leg | Back | Hand | Pain | Unpleasantness | |

| FFMQ non-judgemental inner critic | −0.038 | 0.254 | 0.199 | −0.214 | −0.409b |

| AEQ pain-related thought suppression | −0.222 | −0.159 | −0.114 | 0.197 | 0.345a |

| WBSI generic thought suppression | −0.003 | −0.252 | −0.209 | 0.119 | 0.319a |

-

FFMQ, Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire; AEQ, Avoidance-Endurance Questionnaire; WBSI, White Bear Suppression Inventory. ap<0.05, bp<0.001.

Thus, subsequent hierarchical multiple regression analyses were only calculated for exercise-induced unpleasantness as dependent variable. With respect to the predictive value of spontaneous MM, spontaneous MM (β=−0.31; Table 4) remained as a significant predictor variable when adjusting for age, gender and exercise-induced pain. With respect to the predictive value of TS, both generic TS and pain-related TS did not emerge as significant predictors (p>0.05) after adjusting for age, gender and exercise-induced pain.

Hierarchical multiple linear regression analysis with ratings of exercise-induced unpleasantness during the aerobic cycling exercise as dependent variable and the spontaneous attentional strategy variables as independent variables.

| Dependent variable/step | St. B | SE B | β | p-Value | Change R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unpleasantness |

|

|||||

| 1 | Age | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.32 | 0.023 | 0.422 |

| Gender | −0.00 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.992 | ||

| Exercise-induced pain | 0.38 | 0.14 | 0.36 | 0.012 | ||

| FFMQ non-judgemental inner critic | −0.08 | 0.03 | −0.31 | 0.030 | ||

| 2 | Age | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.32 | 0.020 | 0.000 |

| Exercise-induced pain | 0.38 | 0.14 | 0.36 | 0.010 | ||

| FFMQ non-judgemental inner critic | −0.08 | 0.03 | −0.31 | 0.025 | ||

-

Adjusted R2=0.354 (p<0.001) of model 1; adjusted R2=0.372 (p<0.001) in the final model. FFMQ, Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire.

Experiment 2: manipulation check

According to previously defined manipulation check criteria, 4 participants were excluded from the TS condition as they reported instructed TS scores≤2. Two participants were excluded from the MM group as they reported instructed TS scores≥4. Student’s independent t-tests revealed significant differences between both experimental conditions in the manipulation check variables: the TS condition displayed significantly higher scores on the TS questions (M=3.39, 95 % CI: 3.23 to 3.54) than the MM condition (M=2.72, 95 % CI: 2.56 to 2.87; t=2.17, p<0.05, Cohen’s d=0.75) while the MM condition showed higher scores on the MM questions (M=3.33, 95 % CI: 3.23 to 3.43) compared to the TS condition (M=2.39, 95 % CI: 2.27 to 2.51; t=4.15, p<0.001, Cohen’s d=1.43).

Experiment 2: the effect of instructed attentional strategies on EIH, exercise-induced pain and unpleasantness

T-tests for independent samples indicated a significantly larger EIH response at the back in participants instructed to use TS compared with those instructed to use MM, with a moderate effect size (t=2.01, p<0.05; Cohen’s d=0.71; Table 5). No significant differences between the two groups were seen for the PPT change scores at the hand or at the leg.

Experiment 2: Means (standard deviations) of pressure pain thresholds (PPTs), pain intensity after the first and 10th stimulus of temporal summation of pain testing before and after bicycling, separated for the locations leg, back and hand, as well as ratings of exercise-induced pain, unpleasantness and exertion, and parameters related to the attentional strategies. Results are shown separately for the two instructed attentional strategies “thought suppression” and “mindful monitoring”.

| Instructed thought suppression (n=16) | Instructed mindful monitoring (n=18) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | ∆PPT | Pre | Post | ∆PPT | ||||||

| PPT |

Leg | 480.44 (199.86) | 528.81 (229.87) | 48.37 (72.64) | 369.78 (172.51) | 381.64 (182.88) | 11.86 (101.99) | ||||

| Back | 502.56 (278.13) | 543.47 (291.79) | 40.91 (63.61)a | 398.53 (228.90) | 385.83 (234.67) | −12.69 (84.96) | |||||

| Hand |

356.81 (203.81) |

358.03 (147.96) |

1.21 (62.99) |

265.50 (99.65) |

265.36 (91.62) |

−0.14 (41.31) |

|||||

| Temporal summation |

Stimulus 1

|

Stimulus 10

|

Stimulus 1

|

Stimulus 10

|

|

Stimulus 1

|

Stimulus 10

|

Stimulus 1

|

Stimulus 10

|

|

|

| Leg | 1.40 (1.23) | 3.05 (1.57) | 1.65 (1.04) | 3.45 (1.61) | 2.50 (1.50) | 3.75 (2.12) | 2.30 (1.30) | 3.25 (1.58) | |||

| Back | 1.95 (1.43) | 3.35 (1.69) | 2.20 (1.70) | 3.45 (1.99) | 2.40 (1.50) | 3.55 (1.90) | 2.25 (1.21) | 2.95 (1.43) | |||

| Hand |

2.15 (1.50) |

4.55 (1.85) |

2.30 (1.38) |

5.15 (1.73) |

|

2.80 (1.88) |

4.50 (2.26) |

2.65 (1.35) |

4.35 (1.98) |

|

|

| Exercise ratings |

Exercise-induced pain intensity (1–5) | 2.62 (1.02) | 2.61 (0.85) | ||||||||

| Exercise-induced unpleasantness (1–5) | 3.56 (1.03) | 3.33 (1.08) | |||||||||

| Perceived exertion (Borg 6–20) |

15.88 (1.54) |

|

|

|

15.28 (1.32) |

|

|||||

| Strategy ratings | Difficulty (1–5) | 2.69 (1.14) | 2.78 (1.17) | ||||||||

| Usefulness (1–5) | 2.94 (1.44) | 2.44 (0.86) | |||||||||

| Success (1–5) | 3.50 (1.37)i | 2.61 (0.98) | |||||||||

-

ap<0.05.

With respect to the ratings of exercise-induced pain and unpleasantness, participants using TS did not significantly differ from those using MM (p>0.05, Table 5). Similarly, no significant difference between both groups emerged for ratings of perceived exertion (p>0.05), which was rated as “hard” (M=15.6, 95 % CI: 15.3–15.8), on average. Concerning the ratings of difficulty, usefulness and success of the instructed attentional strategy, participants in the TS condition revealed significantly higher success ratings than participants in the MM condition (Table 5; t=2.199, p<0.05, Cohen’s d=−0.76).

Discussion

This experimental study is the first one investigating the associations of spontaneous and instructed pain-related thought suppression (TS) and mindful monitoring (MM) with exercise-induced pain and exercise-induced hypoalgesia (EIH) in pain-free individuals. Bicycling resulted in both exercise-induced pain and unpleasantness as well as in systemic EIH. In experiment 1, as expected, more spontaneous MM was associated with lower exercise unpleasantness ratings, whereas more pronounced generic and pain-related spontaneous TS were associated with higher exercise unpleasantness ratings. Spontaneous attentional strategies were, however, not associated with ratings of exercise-induced pain and EIH. In experiment 2, a larger EIH response at the back was observed in participants using the TS strategy compared with those using MM.

Influence of attentional strategies on exercise-induced pain and unpleasantness

As expected, more pronounced spontaneous MM was associated with less exercise-induced unpleasantness (experiment 1). This finding is in line with several experimental studies showing positive effects of MM on pain intensity, unpleasantness and distress in response to experimental stimuli other than exercise [15, 21], [22], [23], [24], [25]. MM strategies encompass an attentional focus on sensory information of many potentially uncomfortable events (i.e. monitoring) and a purposeful and acceptance-based awareness of these sensations. Both aspects are represented in the subscale Non-Judgemental Inner Critic of the Five-Facet-Mindfulness Questionnaire [38, 39], which assesses the presumably habitual response to unpleasant sensations, emotions and thoughts. Hence, the present study shows for the first time that individuals who habitually display MM rate their experiences during a standardized physical exercise as less unpleasant than subjects low in MM. MM may therefore facilitate the emotional withdrawal from potentially uncomfortable bouts of physical exercise. Support for this interpretation can be drawn from a qualitative finding by Cioffi [24], showing that individuals using MM evaluated their sensations during bicycling as rather exercise-induced, whereas participants in a control condition rather attributed their sensations to pathological sources such as possible health problems (e.g. bad circulation, fever or being out of shape). Future research should address whether such different attributions exist in individuals scoring high or low in spontaneous MM.

Instructed MM, however, did not reduce exercise-induced pain or unpleasantness (experiment 2). This is in contrast to a number of experimental studies in pain-free individuals and patients with pain reporting negative associations between MM and pain [16, 21, 23], although other studies failed to find beneficial effects on pain [26, 44, 50]. A possible explanation may be that, in many studies, the MM instruction was brief and without an additional mindfulness training. As MM is hardly a spontaneous or intuitive strategy to cope with pain [24] and was rated as rather difficult in our study, the lack of effects of MM might be due to a lack of training. Research showing benefits from mindfulness in participants with a regular meditation practice [51] supports this assumption.

In line with our expectations, higher scores of spontaneous generic or pain-related TS were associated with higher unpleasantness ratings of the exercise. This finding corresponds not only with experimental research showing detrimental effects of TS on subjective-evaluative parameters of pain experience, such as unpleasantness [14, 16, 47] or affective distress [14, 15], but also clinical research demonstrating a link between spontaneous pain-related TS and depression in patients suffering from pain [18, 52, 53]. Further support for our finding can be drawn from a study in individuals with back pain showing a positive relationship between spontaneous pain-related TS and clinical pain [12]. According to the theory of ironic processes of mental control [37], these detrimental effects may stem from two cognitive processes which are simultaneously activated: the operating process, i.e. a conscious, effortful search for distraction, and the monitoring process, i.e. an automatic, non-conscious evaluation of successful suppression. TS is often unsuccessful because the monitoring process constantly recollects the unwanted thoughts/sensations, eventually causing distress or depressive mood [15]. As the aim of TS is to “not think about pain”, it does not put in concrete terms what to think of instead, resulting in a potential unfocused search for alternative thoughts and a switching of possible distractors [37]. However, these distractors may become cues for the unwanted thoughts leading to paradoxical effects of TS [37].

Unexpectedly, spontaneous TS (both generic and pain-related) was not associated with exercise-induced pain which is in contrast to the literature on detrimental short- and long-term effects of pain-related TS on somatic pain experience [14, 16, 54]. A possible reason may be that the exercise in this study was experienced as unpleasant and strenuous rather than painful, in contrast to the experimental stimuli used in previous studies (e.g. ice baths).

Influence of attentional strategies on EIH

In contrast to our hypotheses, experiment 1 indicated no association between spontaneous TS or MM and physiological indicators of EIH. Even more surprising, experiment 2 revealed significantly larger increases for PPTs at the back after exercise for the TS group compared to the MM group, pointing towards a rather beneficial effect of TS on EIH. As research on the impact of attentional strategies on EIH is still in its beginning, our finding has to be interpreted with caution. It is possible that TS may cause short-term physiological alterations that are linked to reduced pain sensitivity. For example, TS was shown to activate the sympathetic arousal of the autonomic nervous system, as indicated by increased exhibition of skin conductance levels [55, 56] and finger pulse amplitude or temperature [56]. Wegner et al. [55] further showed that the increases in skin conductance levels were of rather short duration, occurring 3 min after stimulation and disappearing after 30 min. Thus, it is conceivable that experimentally induced TS causes a short-term physiological effect in terms of hypoalgesia after exercise. More recent brain imaging studies underline the role of physiology, elucidating specific neural pathways that play a role in the attentional modulation of pain [57], even for spontaneous pain-related TS [58]. Spontaneous and habitually shown TS, however, rather appears to be associated with elevated stress such as stronger unpleasantness during exercise, as indicated by experiment 1. These findings support the idea that the suppression of negative feelings and sensations might be maintained by principles of reinforcement learning with short-term positive and delayed negative consequences [59, 60].

Furthermore, it is important to emphasize that the choice of pain parameters may play a prominent role to study the relationship between TS and EIH. There is, for example, a lack of research on the impact of TS on pain thresholds, and it has been long debated whether or not pain thresholds are more physiologically determined and/or affected by psychological manipulation [21]. More studies are required to investigate the impact of attentional strategies on EIH assessed not only via pain thresholds but also with pain tolerance and affective (or subjective-evaluative) outcomes after exercise.

Clinical implications

This study has potential implications for clinicians interested in how to apply physical exercise to people experiencing unpleasantness or pain during physical therapy. In order to consider spontaneous attentional strategies, it would be necessary to apply a short screening assessing habitual (or dispositional) strategies to respond to pain, such as TS or the tendency to mindfully monitor bodily sensations. Possibly, more pronounced TS and less pronounced MM might increase the probability that a participant will feel uncomfortable during exercise. It is therefore important to bear in mind that – when mindfulness practices are incorporated into pain treatment – a simple short encouragement by the clinician to mindfully monitor sensory sensations and pain during exercise will probably not yield the expected benefit. Instead, a more comprehensive training of mindfulness may be necessary to reduce possible feelings of unpleasantness and pain.

Limitations

The cross-sectional design of experiment 1 limits its informative value regarding the causal effects of MM and TS on pain experience under single-bout exercise. However, it is possible that the effects of habitual pain-related cognitions deviate from those of experimentally manipulated ones which underlines the relevance of studying habitual modes for their greater external and ecological validity. As discussed, the instruction and a lack of training of MM and TS might have influenced the results, and the generalizability of an MM instruction to mindfulness training programs may be limited, since the employed instruction is not equivalent to intensive mindfulness trainings. Furthermore, the order between exercise and quiet rest was not counterbalanced, and sample sizes for each group were rather small. Future studies might investigate the impact of attentional strategies on EIH using larger sample sizes in order to sufficiently power interaction terms exploring individual differences in the response to exercise and cognitive manipulation. Further, as our results may not necessarily be transferred to clinical samples, the influence of attentional strategies on the experience of pain during exercise in patients should be explored.

Conclusions

Spontaneous and presumably habitual MM and TS contrasted in their relation to exercise-induced unpleasantness: whereas MM was associated with lower ratings of unpleasantness, TS was associated with higher unpleasantness. Experimentally instructed TS may be related to higher EIH whereas short instruction to MM without a special training were not. Further research in the role of attention-related strategies for the experience of physical exercise and EIH is warranted.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants for their participation.

-

Research funding: No external funding was received for this study. HBV is supported by a Visiting International Professor fellowship of Ruhr-University Bochum (RUB) Research School.

-

Author contributions: All listed authors contributed to the present study based on substantial contributions to study design, data collection, data analyses and interpretation of data. Furthermore, all included authors were involved in discussing the results, drafting the article, or commenting on the manuscript.

-

Competing of interests: There are no actual or potential conflicts of interest for any of the authors.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

-

Ethics approval: This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology at the Ruhr University Bochum (application #242).

References

1. Vaegter, HB, Dørge, DB, Schmidt, KS, Jensen, AH, Graven-Nielsen, T. Test-retest reliability of exercise-induced hypoalgesia after aerobic exercise. Pain Med 2018;19:2212–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pny009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Vaegter, HB, Bjerregaard, LK, Redin, MM, Rasmussen, SH, Graven-Nielsen, T. Hypoalgesia after bicycling at lactate threshold is reliable between sessions. Eur J Appl Physiol 2019;119:91–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-018-4002-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Grimby-Ekman, A, Ahlstrand, C, Gerdle, B, Larsson, B, Sandén, H. Pain intensity and pressure pain thresholds after a light dynamic physical load in patients with chronic neck-shoulder pain. BMC Muscoskel Disord 2020;21:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03298-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Vaegter, HB, Petersen, KK, Sjodsholm, LV, Schou, P, Andersen, MB, Graven‐Nielsen, T. Impaired exercise‐induced hypoalgesia in individuals reporting an increase in low back pain during acute exercise. Eur J Pain 2021;25:1053–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1726.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Naugle, KM, Fillingim, RB, Riley, JLIII. A meta-analytic review of the hypoalgesic effects of exercise. J Pain 2012;13:1139–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2012.09.006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Vaegter, HB, Jones, MD. Exercise-induced hypoalgesia after acute and regular exercise: experimental and clinical manifestations and possible mechanisms in individuals with and without pain. Pain Reports 2020;5:e823. https://doi.org/10.1097/pr9.0000000000000823.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Rice, D, Nijs, J, Kosek, E, Wideman, T, Hasenbring, MI, Koltyn, K, et al.. Exercise-induced hypoalgesia in pain-free and chronic pain populations: state of the art and future directions. J Pain 2019;20:1249–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2019.03.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Brellenthin, AG, Crombie, KM, Cook, DB, Sehgal, N, Koltyn, KF. Psychosocial influences on exercise-induced hypoalgesia. Pain Med 2017;18:538–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnw275.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Koltyn, KF, Brellenthin, AG, Cook, DB, Sehgal, N, Hillard, C. Mechanisms of exercise-induced hypoalgesia. J Pain 2014;15:1294–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2014.09.006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Sluka, KA, Law, LF, Bement, MH. Exercise-induced pain and analgesia? Underlying mechanisms and clinical translation. Pain 2018;159:S91–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001235.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Vaegter, HB, Thinggaard, P, Madsen, CH, Hasenbring, M, Thorlund, JB. Power of words: influence of preexercise information on hypoalgesia after exercise-randomized controlled trial. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2020;52:2373–9. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0000000000002396.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Hasenbring, MI, Hallner, D, Rusu, AC. Fear-avoidance-and endurance-related responses to pain: development and validation of the Avoidance-Endurance Questionnaire (AEQ). Eur J Pain 2009;13:620–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.11.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Wegner, DM, Schneider, DJ, Carter, SR, White, TL. Paradoxical effects of thought suppression. J Pers Soc Psychol 1987;53:5–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.53.1.5.Search in Google Scholar

14. Elfant, E, Burns, JW, Zeichner, A. Repressive coping style and suppression of pain-related thoughts: effects on responses to acute pain induction. Cognit Emot 2008;22:671–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930701483927.Search in Google Scholar

15. Masedo, AI, Esteve, MR. Effects of suppression, acceptance and spontaneous coping on pain tolerance, pain intensity and distress. Behav Res Ther 2007;45:199–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2006.02.006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Cioffi, D, Holloway, J. Delayed costs of suppressed pain. J Pers Soc Psychol 1993;64:274–82. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.64.2.274.Search in Google Scholar

17. Gajsar, H, Titze, C, Levenig, C, Kellmann, M, Heidari, J, Kleinert, et al.. Psychological pain responses in athletes and non‐athletes with low back pain: avoidance and endurance matter. Eur J Pain 2019;23:1649–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1442.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Hülsebusch, J, Hasenbring, MI, Rusu, AC. Understanding pain and depression in back pain: the role of catastrophizing, help-/hopelessness, and thought suppression as potential mediators. Int J Behav Med 2016;23:251–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-015-9522-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 2003;10:144–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg016.Search in Google Scholar

20. Prins, B, Decuypere, A, Van Damme, S. Effects of mindfulness and distraction on pain depend upon individual differences in pain catastrophizing: an experimental study. Eur J Pain 2014;18:1307–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1532-2149.2014.491.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Ahles, TA, Blanchard, EB, Leventhal, H. Cognitive control of pain: attention to the sensory aspects of the cold pressor stimulus. Cognit Ther Res 1983;7:159–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01190070.Search in Google Scholar

22. Blitz, B, Dinnerstein, AJ. Effects of different types of instructions on pain parameters. J Abnorm Psychol 1968;73:276–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0025745.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Braams, BR, Blechert, J, Boden, MT, Gross, JJ. The effects of acceptance and suppression on anticipation and receipt of painful stimulation. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatr 2012;43:1014–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2012.04.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Cioffi, D. Beyond attentional strategies: a cognitive-perceptual model of somatic interpretation. Psychol Bull 1991;109:25–41. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.109.1.25.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Leventhal, H, Brown, D, Shacham, S, Engquist, G. Effects of preparatory information about sensations, threat of pain, and attention on cold pressor distress. J Pers Soc Psychol 1979;37:688–714. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.37.5.688.Search in Google Scholar

26. Burns, JW. The role of attentional strategies in moderating links between acute pain induction and subsequent psychological stress: evidence for symptom-specific reactivity among patients with chronic pain versus healthy nonpatients. Emotion 2006;6:180–92. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.6.2.180.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Gajsar, H, Titze, C, Hasenbring, MI, Vaegter, HB. Isometric back exercise has different effect on pressure pain thresholds in healthy men and women. Pain Med 2017;18:917–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnw176.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Gajsar, H, Nahrwold, K, Titze, C, Hasenbring, MI, Vaegter, HB. Exercise does not produce hypoalgesia when performed immediately after a painful stimulus. Scand J Pain 2018;18:311–20. https://doi.org/10.1515/sjpain-2018-0024.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Gomolka, S, Vaegter, HB, Nijs, J, Meeus, M, Gajsar, H, Hasenbring, MI, et al.. Assessing endogenous pain inhibition: test–retest reliability of exercise-induced hypoalgesia in local and remote body parts after aerobic cycling. Pain Med 2019;20:2272–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnz131.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Oldfield, RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 1971;9:97–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Cathcart, S, Winefield, AH, Rolan, P, Lushington, K. Reliability of temporal summation and diffuse noxious inhibitory control. Pain Res Manag 2009;14:433–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2009/523098.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Vaegter, HB, Handberg, G, Graven-Nielsen, T. Similarities between exercise-induced hypoalgesia and conditioned pain modulation in humans. Pain 2014;155:158–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2013.09.023.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Vaegter, HB, Handberg, G, Graven‐Nielsen, T. Isometric exercises reduce temporal summation of pressure pain in humans. Eur J Pain 2015a;19:973–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.623.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Vaegter, HB, Handberg, G, Jørgensen, MN, Kinly, A, Graven-Nielsen, T. Aerobic exercise and cold pressor test induce hypoalgesia in active and inactive men and women. Pain Med 2015b;16:923–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/pme.12641.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Swain, DP, Abernathy, KS, Smith, CS, Lee, SJ, Bunn, SA. Target heart rates for the development of cardiorespiratory fitness. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1994;26:112–6. https://doi.org/10.1249/00005768-199401000-00019.Search in Google Scholar

36. Borg, GA. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1982;14:377–81. https://doi.org/10.1249/00005768-198205000-00012.Search in Google Scholar

37. Wegner, DM, Zanakos, S. Chronic thought suppression. J Pers 1994;62:615–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1994.tb00311.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Michalak, J, Zarbock, G, Drews, M, Otto, D, Mertens, D, Ströhle, G, et al.. Erfassung von Achtsamkeit mit der deutschen Version des Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaires (FFMQ-D). Z für Gesundheitspsychol 2016;24:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1026/0943-8149/a000149.Search in Google Scholar

39. Baer, RA, Smith, GT, Hopkins, J, Krietemeyer, J, Toney, L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment 2006;13:27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191105283504.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Baer, RA, Carmody, J, Hunsinger, M. Weekly change in mindfulness and perceived stress in a mindfulness‐based stress reduction program. J Clin Psychol 2012;68:755–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21865.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Baer, RA, Smith, GT, Lykins, E, Button, D, Krietemeyer, J, Sauer, S, et al.. Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment 2008;15:329–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191107313003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

42. Gu, J, Strauss, C, Crane, C, Barnhofer, T, Karl, A, Cavanagh, K, et al.. Examining the factor structure of the 39-item and 15-item versions of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire before and after mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for people with recurrent depression. Psychol Assess 2016;28:791–802. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000263.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

43. Harvey, AG, McGuire, BE. Suppressing and attending to pain-related thoughts in chronic pain patients. Behav Res Ther 2000;38:1117–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00150-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

44. McCaul, KD, Haugtvedt, C. Attention, distraction, and cold-pressor pain. J Pers Soc Psychol 1982;43:154–62. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.43.1.154.Search in Google Scholar

45. Michael, ES, Burns, JW. Catastrophizing and pain sensitivity among chronic pain patients: moderating effects of sensory and affect focus. Ann Behav Med 2004;27:185–94. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm2703_6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

46. Shires, A, Sharpe, L, Newton John, TR. The relative efficacy of mindfulness versus distraction: the moderating role of attentional bias. Eur J Pain 2019;23:727–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1340.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

47. Burns, JW, Elfant, E, Quartana, PJ. Suppression of pain-related thoughts and feelings during pain-induction: sex differences in delayed pain responses. J Behav Med 2010;33:200–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-010-9248-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

48. Naugle, KM, Naugle, KE, Fillingim, RB, Riley, JL3rd. Isometric exercise as a test of pain modulation: effects of experimental pain test, psychological variables, and sex. Pain Med 2013;15:692–701. https://doi.org/10.1111/pme.12312.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

49. Koenker, R. A note on studentizing a test for heteroscedasticity. J Econom 1981;17:107–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(81)90062-2.Search in Google Scholar

50. Petter, M, Chambers, CT, Chorney, JM. The effects of mindful attention on cold pressor pain in children. Pain Res Manag 2013;18:39–45. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/857045.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

51. Zeidan, F, Gordon, NS, Merchant, J, Goolkasian, P. The effects of brief mindfulness meditation training on experimentally induced pain. J Pain 2010;11:199–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2009.07.015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

52. Konietzny, K, Chehadi, O, Streitlein-Böhme, I, Rusche, H, Willburger, R, Hasenbring, MI. Mild depression in low back pain: the interaction of thought suppression and stress plays a role, especially in female patients. Int J Behav Med 2018;25:207–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-017-9657-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

53. Konietzny, K, Chehadi, O, Levenig, C, Kellmann, M, Kleinert, J, Mierswa, T, et al.. Depression and suicidal ideation in high‐performance athletes suffering from low back pain: the role of stress and pain‐related thought suppression. Eur J Pain 2019;23:1196–208. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1387.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

54. Hasenbring, MI, Hallner, D, Klasen, B, Streitlein-Böhme, I, Willburger, R, Rusche, H. Pain-related avoidance versus endurance in primary care patients with subacute back pain: psychological characteristics and outcome at a 6-month follow-up. Pain 2012;153:211–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2011.10.019.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

55. Wegner, DM, Shortt, JW, Blake, AW, Page, MS. The suppression of exciting thoughts. J Pers Soc Psychol 1990;58:409–18. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.3.409.Search in Google Scholar

56. Gross, JJ. Antecedent-and response-focused emotion regulation: divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. J Pers Soc Psychol 1998;74:224–37. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.1.224.Search in Google Scholar

57. Bushnell, MC, Čeko, M, Low, LA. Cognitive and emotional control of pain and its disruption in chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci 2013;14:502–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3516.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

58. Chehadi, O, Rusu, AC, Konietzny, K, Schulz, E, Köster, O, Schmidt‐Wilcke, T, et al.. Brain structural alterations associated with dysfunctional cognitive control of pain in patients with low back pain. Eur J Pain 2018;22:745–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1159.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

59. Fordyce, WE. Behavioral methods for chronic pain and illness. St. Loius: Mosby; 1977.10.1016/0304-3959(77)90029-XSearch in Google Scholar

60. Hasenbring, MI, Andrews, NE, Ebenbichler, G. Overactivity in chronic pain, the role of pain-related endurance and neuromuscular activity: an interdisciplinary, narrative review. Clin J Pain 2020;36:162–71. https://doi.org/10.1097/ajp.0000000000000785.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Systematic Review

- Comparison of the effectiveness of eHealth self-management interventions for pain between oncological and musculoskeletal populations: a systematic review with narrative synthesis

- Topical Review

- Shifting the perspective: how positive thinking can help diminish the negative effects of pain

- Clinical Pain Researches

- Pain acceptance and psychological inflexibility predict pain interference outcomes for persons with chronic pain receiving pain psychology

- A feasibility trial of online Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for women with provoked vestibulodynia

- Relations between PTSD symptom clusters and pain in three trauma-exposed samples with pain

- Short- and long-term test–retest reliability of the English version of the 7-item DN4 questionnaire – a screening tool for neuropathic pain

- Chronic post-thoracotomy pain after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study of preoperative risk factors

- Pain sensitivity after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass – associations with chronic abdominal pain and psychosocial aspects

- Barriers in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) management: perspectives from health practitioners

- Observational studies

- Spontaneous self-affirmation: an adaptive coping strategy for people with chronic pain

- COVID-19 and processes of adjustment in people with persistent pain: the role of psychological flexibility

- Presence and grade of undertreatment of pain in children with cerebral palsy

- Sex-related differences in migraine clinical features by frequency of occurrence: a cross-sectional study

- Recurrent headache, stomachache, and backpain among adolescents: association with exposure to bullying and parents’ socioeconomic status

- Original Experimentals

- Temporal stability and responsiveness of a conditioned pain modulation test

- Anticipatory postural adjustments mediate the changes in fear-related behaviors in individuals with chronic low back pain

- The role of spontaneous vs. experimentally induced attentional strategies for the pain response to a single bout of exercise in healthy individuals

- Acute exercise of painful muscles does not reduce the hypoalgesic response in young healthy women – a randomized crossover study

- Short Communications

- Nation-wide decrease in the prevalence of pediatric chronic pain during the COVID-19 pandemic

- A multidisciplinary transitional pain service to improve pain outcomes following trauma surgery: a preliminary report

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Systematic Review

- Comparison of the effectiveness of eHealth self-management interventions for pain between oncological and musculoskeletal populations: a systematic review with narrative synthesis

- Topical Review

- Shifting the perspective: how positive thinking can help diminish the negative effects of pain

- Clinical Pain Researches

- Pain acceptance and psychological inflexibility predict pain interference outcomes for persons with chronic pain receiving pain psychology

- A feasibility trial of online Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for women with provoked vestibulodynia

- Relations between PTSD symptom clusters and pain in three trauma-exposed samples with pain

- Short- and long-term test–retest reliability of the English version of the 7-item DN4 questionnaire – a screening tool for neuropathic pain

- Chronic post-thoracotomy pain after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study of preoperative risk factors

- Pain sensitivity after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass – associations with chronic abdominal pain and psychosocial aspects

- Barriers in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) management: perspectives from health practitioners

- Observational studies

- Spontaneous self-affirmation: an adaptive coping strategy for people with chronic pain

- COVID-19 and processes of adjustment in people with persistent pain: the role of psychological flexibility

- Presence and grade of undertreatment of pain in children with cerebral palsy

- Sex-related differences in migraine clinical features by frequency of occurrence: a cross-sectional study

- Recurrent headache, stomachache, and backpain among adolescents: association with exposure to bullying and parents’ socioeconomic status

- Original Experimentals

- Temporal stability and responsiveness of a conditioned pain modulation test

- Anticipatory postural adjustments mediate the changes in fear-related behaviors in individuals with chronic low back pain

- The role of spontaneous vs. experimentally induced attentional strategies for the pain response to a single bout of exercise in healthy individuals

- Acute exercise of painful muscles does not reduce the hypoalgesic response in young healthy women – a randomized crossover study

- Short Communications

- Nation-wide decrease in the prevalence of pediatric chronic pain during the COVID-19 pandemic

- A multidisciplinary transitional pain service to improve pain outcomes following trauma surgery: a preliminary report