Abstract

The use of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWC-NTs), as excellent mechanical and conductive fibers, for making self-sensing cementitious composites has attracted great interest. However, few researches have focused on the durability of mortar with MWCNTs. This paper attempts to explore the corrosion of embedded steel rebar in cement mortar with different contents of MWC-NTs. Tests for compressive strength, chloride migration coefficient, conductivity, and corrosion behaviors of MWCNT-cement mortar were carried out. The results show that the addition of MWCNTs to the cement mortar accelerated the development of the steel corrosion under chloride environment. The migration behavior of chlorine ions and steel corrosion rate were related to the carbon nanotube content. The increase in carbon nanotube content resulted in higher steel corrosion intensities. Moreover, the rates of chloride transport into the mortar increased with the nanotube content under both accelerated and natural chloride conditions.

1 Introduction

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) is one of the strongest and stiffest nanomaterials with excellent physical properties. Both theoretical and experimental results have shown that the bending modulus is extremely high, larger than 1 TPa (as strong as diamond), and the tensile strength of an individual CNT fiber can reach 100 GPa [1, 2]. Therefore, CNTs can be used to enhance the fracture properties of cement-based composites and to reduce or prevent crack initiation [3] in concrete structures where cracking should be limited, such as dams, tunnels and nuclear plants. Additionally, the specific surface area of CNTs is extraordinarily large, with a value of up to 1,000m2·g-1 [4]. Indeed, owing to the good electrical conductivity of carbon fibers [5, 6], their addition to concrete is one possible solution to producing a composite material with stress-resistance sensitivity, which acts as a smart material in construction for strain monitoring and electromagnetic interference shielding applications [7].

The durability of reinforced concrete structure is a significant issue considering its service life. Chloride penetration is one of the most concerned factors causing the corrosion of reinforced concrete. Moreover, the periodic drying-wetting conditions in tidal zones accelerate the chloride penetration and shortens the service life of reinforced concrete structures significantly. Therefore, designers should be aware of the durability characteristics of cement-based materials with the addition of any novel material (e.g., CNTs) before they are applied to concrete structures in chlorine salt environments.

Chloride-induced steel corrosion is one of the most important durability issues in concrete structures [8, 9]. Chloride ions from the exposed surface transport through the concrete cover and reach the steel surface. When the chloride content near the steel exceeds a threshold value, the passive film of the steel will be damaged and initiation of steel corrosion will possibly occur [10]. The chloride threshold ranges from0.03% to 4 % free chloride by cement mass [11]. The large variation of the threshold value is possibly due to the material mix, the environment conditions and monitoring method for passivation. It was found that the assessment of corrosion initiation was highly sensitive to the uncertainty in the chloride threshold level [12]. On the other hand, systematic study has not been found on the chloride-induced corrosion of embedded steel rebars in CNT-cement composites exposed to a chlorine salt environment. Previous studies have shown that the dispersion of fibers in reinforced cement-based material had an important effect on the levels of corrosion wherein corrosion rates were slightly higher due to a better conductivity of the composite with super conductive CNTs [13, 14, 15, 16, 17]. Konsta-Gdoutos and Aza [18] proved well that dispersed CNTs and carbon nanofibers decreased the electrical resistance of cement paste under loading. Li et al. [19] discovered that the electrical resistance of cement-based materials decreased as treated (SPCNTs) or untreated CNTs (CNTs) were added. Del et al. [20] studied the corrosion development of the steel reinforcement with the addition of CNTs, and the results showed that a higher content of CNTs resulted in a higher corrosion rate due to the higher conductivity. Luo et al. [21] tested the electrical resistance of the cement-based composites with 0.1 and 0.5 wt% multi-walled CNTs (MWC-NTs), and found that the addition of 0.5 wt%MWCNTs had better electrical properties.

The purpose of this paper is to clarify the behavior of chloride migration and corrosion kinetics of reinforced cement mortar with different MWCNT contents under chloride environment. To this end, rapid chloride penetration tests were conducted to obtain chloride migration coefficients of the cement mortar. Additionally, the chloride penetration depths under natural conditions were tested by chloride penetration tests. The conductivity of the mortar with MWCNTs, the corrosion potential, corrosion rate and electrochemical mass loss of steel rebar embedded in the mortar were also tested.

2 Experimental work

2.1 Materials and specimen preparation

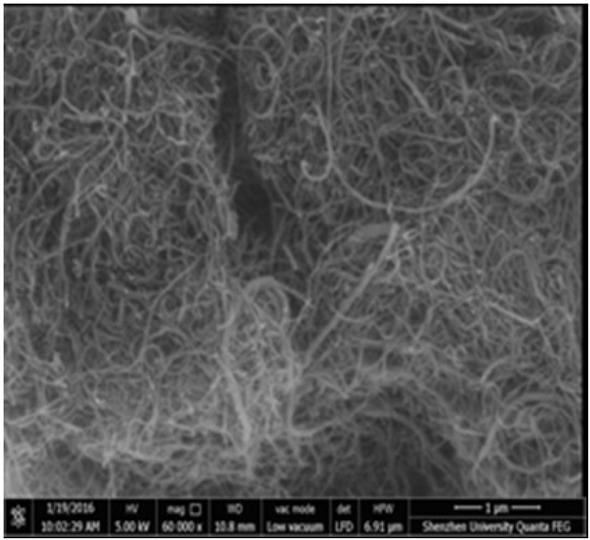

Type I 42.5 Portland cement by the Guangzhou Xinhe Co., Ltd (Guangdong, China) and sand with standard gradation by the China ISO Standard Sand Co., Ltd (Fujian, China) were used. The multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) were provided by Chengdu Institute of Organic Chemistry Research Institute (Sichuan, China). The morphology and physical properties of MWCNTs are shown in Figure 1 and Table 1, respectively. The dispersant used in this study is polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) with a chemical formula of (C6H9NO)n, produced by the Shanghai Jingchun Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd.

Scanning electron microscopy image of MWCNTs

Properties of the MWCNTs used in this study.

| Type | Diameter | Length | Purity | Specific surface area | Electric conductivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MWCNTs | 10-20 nm | 10-30 μm | >95% | >150 m2/g | 100 S/cm |

Samples with four different weight percentages of MWCNTs, viz. 0%, 0.02%, 0.1% and 0.2% by cement weight, two different water to cement ratios (w/c), viz. 0.4 and 0.5 were used. They were denoted as “w/c+CT” and “w/c+C+wt% of MWCNTs”, respectively, where the former indicated control sample and the latter indicated specimens with two different w/c ratios and four different contents of MWCNTs. The detailed mix proportions are listed in Table 2.

Mix proportions of specimens

| Specimens | w/c | Cement (g) | Sand (g) | MWCNTs (g) | MPVP/MMWCNTs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.4CT | 0.4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 0.4C0.02 | 0.4 | 1 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| 0.4C0.1 | 0.4 | 1 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| 0.4C0.2 | 0.4 | 1 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.8 |

| 0.5CT | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 0.5C0.02 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| 0.5C0.1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| 0.5C0.2 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.8 |

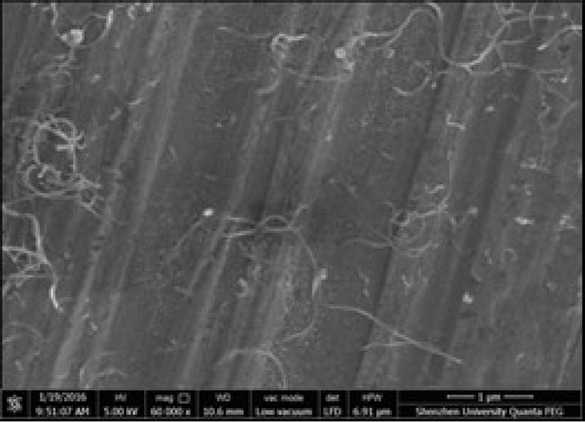

MWCNT dispersion directly influences the properties of the cement composite and thus is an essential procedure for a proper use of MWCNTs in cement-based materials. Currently, surfactants and sonication are commonly used to disperse MWCNTs into water. During sonication, the entangled MWCNTs can be dispersed by the bubbles created by waves through releasing high levels of energy. Besides, surfactant can be adsorbed on the MWCNTs surface and protects MWCNTs from agglomeration. In this study, PVP was selected as surfactant mainly because previous experimental research [22] showed that PVP can effectively disperse carbon nanotubes in aqueous solutions. When the content of PVP is less than 1% (relative to the weight of cement), the PVP influence on the mechanical properties and durability of cement-based materials can be neglected [23, 24]. Therefore, the maximum content of PVP used in this study was below 0.8%. During the preparation, a designated amount of PVP and MWCNTs was added to the water, and the composite was mixed with a magnetic stirrer at a constant low speed for 15 mins. A JY92-IIN Ultrasonic Cell Disrupter (Ningbo Scientz Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Ningbo, China) was used for successive sonication of the aqueous suspension of MWCNTs for 20 mins. During the sonication process, the energy output was controlled at 125 kJ/mL, and it was set in a duration of 3 s cyclic stirring and 3 s standing regime [25]. The resulted dispersion in Figure 2 indicates an excellent dispersion performance of carbon nanotubes after sonication.

SEM image of MWCNTs after dispersion

The aqueous MWCNT suspension was then mixed with water, and they were poured into a standard mortar mixer, followed by mixing cement and sand for 1 min. To test the compressive strength of mortar samples with 0.4 and 0.5 water-cement ratios, fresh specimens were cast into steel molds with dimensions of 160 × 40 × 40 mm. Furthermore, samples with a diameter of 100 mm and lengths of 50 and 100 mm were made for rapid chloride ion migration tests and for natural chloride ion penetration tests, respectively. All samples were cured under a standard curing condition until used. After curing for 28 days, the compressive strength tests were conducted according to ASTM C349. The samples with a water-cement ratio of 0.5 were tested for corrosion potential, corrosion current, conductivity, and mass loss of steel rebar based on the limit size of Φ20.8 mm × 70 mm, which needed better fluidity to compact well.

2.2 Rapid chloride ion migration tests

After curing for 28 days, the cylindrical samples with dimensions of 100 mm in diameter and 50 mm in length were used to test the migration coefficient of chloride ions for the MWCNT mortar. First, the cylindrical samples were vacuum saturated by distilled water. Then, a 3.0% NaCl solution was applied on one side of the cylinder samples, and the other side was exposed to a 0.3 mol/L NaOH solution [26]. During the rapid chloride penetration test, the ambient temperature of the specimens was controlled at 20°C. Based on the test results, the chloride migration coefficient was calculated as follows [27]:

where DRCM is the unsteady chloride migration coefficient of concrete, m2/s; U is the absolute voltage, V; T is the average of the initial and end temperatures of the anodic solution, K; L is the thickness of sample, m; Xd is the average penetration depth of chlorine ions, m.

2.3 Natural chloride diffusion tests

Three cement mortar specimens of 100 mm in diameter and 50 mm in length were prepared for testing the performance of chloride diffusion under natural conditions. The bottom and side faces of the concrete were sealed with epoxy resin on all their surfaces except the top surface as an exposed surface. According to NT Build 443, the exposure time was set as 35 d, 45 d, 55 d, and 65 d. The mean penetration depth of chloride ions was obtained after spraying with silver nitrate solution on the specimen section.

2.4 Conductivity measurements

In this study, the resistivity performance of MWCNT-reinforced mortars after 28 d-curing were determined using an alternating-current (AC) power, following the two-pole method, wherein two titanium electrical contacts were embedded in the two parallel planes of mortar. The electrical resistance was measured with a Galvanostat 283 potentiostat at a 100 kHz frequency [26]. The amplitude of the sinusoidal voltage was chosen to be 2 V. To fully understand the nature and geometry of the mortar containing with MWCNTs, the resistance measurement was converted to resistivity and calculated as resistance per unit length:

where R is the resistance of the cement mortar; S is the cross section of the sample; and L is the distance between the two inner electrodes.

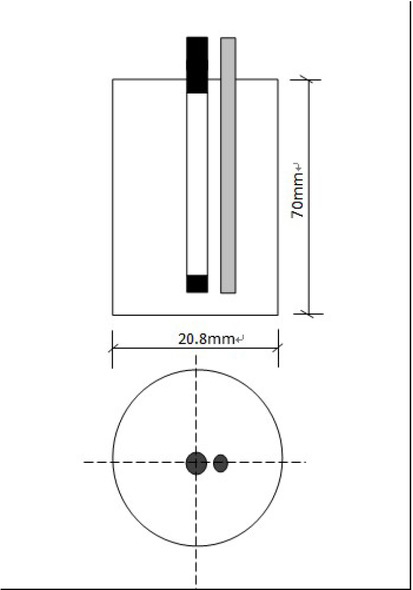

2.5 Electrochemical corrosion tests

Cylindrical specimens of Φ20.8 mm × 70 mm were prepared for corrosion potential and corrosion rate tests. Each specimen contained a 6 mm-diameter cylindrical steel electrode in the middle and a stainless-steel counter electrode beside it. The exposed steel covered an area of 17.27 cm2. Figure 3 shows the layout of the specimens used in the corrosion test, which is similar to that used in previous study [28, 29, 30, 31, 32]. Corrosion potential (Ecorr) and corrosion rate (Icorr) were measured on each steel electrode and two electrodes were measured on each sample.

Dimensions of corrosion test specimen

After curing for 14 days under a standard curing condition, the samples were taken into an electrochemical work-station. The stainless-steel bar was used as counter electrode and saturated calomel was used as reference electrode. The potentiostatic/galvanostatic meter was used to measure the first polarization curve near the corrosion potential of the steel reinforcement. After curing for 28 days, the marine tidal environment was simulated. The specimens were placed in a chloride environment under periodic drying and wetting conditions. In the first curing setup with a temperature of 40°C, the samples were dried for two days in the drying oven; then, they were moved to a vat with saline solution with a salt content of 3.5% (relative to the weight of the water) and remained immersed in the water for 3 days. After one drying-wetting cycle, the samples were removed from the saline solution and moved to the electrochemical workstation where the polarization curve was measured. After that, the samples were put into a drying oven to start the next drying and wetting process. The samples were tested using the polarization resistance method, and the instantaneous corrosion rate Icorr was calculated using Geary and Stern’s equation [33]:

where Icorr is the corrosion rate, μA/cm2; Pr is the polarization resistance, kΩ·cm2; B is a constant, and is assumed to be 26 mV of the steel-cement system [33]. Icorr and Ecorr were tested regularly. All potential values were referenced to the saturated calomel electrode (SCE).

Before the corrosion test, each steel bar was weighed, and after the tests, the internal bar was taken out from the split specimens. The rust on the rebar surfaces was cleaned immediately with a hydrochloric acid solution using an ultrasonic cleaning instrument; then, the cleaned rebar was weighed. Finally, the original weight of the reinforcement minus the residual weight after de-rusting was equal to the specimen’s mass of corrosion on the steel bar reinforcement.

3 Results and Discussion

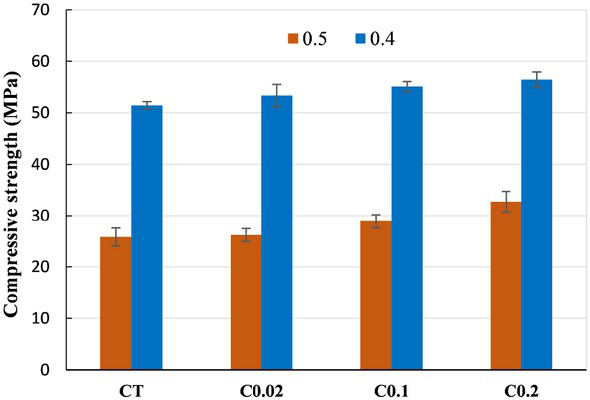

3.1 Compressive Strength

The compressive strength of specimens after 28 days of standard curing is shown in Figure 4. The results showed that the addition of MWCNTs increased the compressive strengths for mortars with w/c ratios of 0.4 and 0.5. For the samples with 0.5 w/c, the strength improvement was observed in the 0.5C0.2 specimens, whose average strength was 26.8% higher than the control sample 0.5CT. For the samples with 0.4w/c, the greatest improvement was found for 0.2wt%MWCNTs. The results also indicated that higher water-cement ratios led to lower compressive strength at different contents of MWCNTs. The results proved that the ultrasonication incorporating surfactant dispersion method is an effective alternative for MWCNTs dispersion in the cement mortar. The compressive strength of cement mortar was enhanced by the addition ofMWCNTs, possibly because the internal stress was redistributed and the propagation of microcracks was inhibited due to the bonding, bridging and filling effects of MWCNTs [34, 35, 36].

Compressive strengths of samples

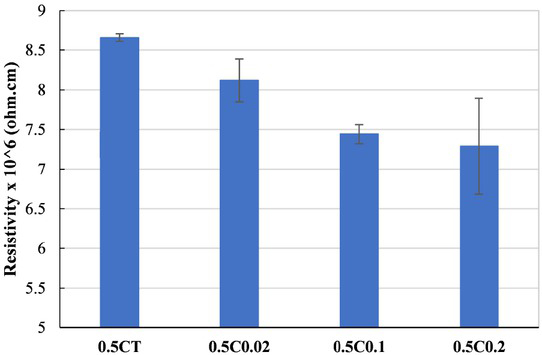

3.2 Electrical resistance

The tested electrical resistance of the cement mortar with 0.02 wt%, 0.1 wt%, and 0.2 wt% MWCNTs is shown in Figure 5. The results showed that the addition of MWCNTs to the cement mortar significantly decreased the electrical resistivity, even with a very low amount of addition (0.02 wt%), which was similar to the previous results [37]. The sample with 0.2 wt% MWCNTs showed the lowest resistivity compared to the other samples with different contents of MWCNTs. Indeed, the resistivity of the cement mortar decreased with the increasing content of MWCNTs. The increased MWCNT content allowed the presence of more electric channels in the mortar matrix with bridging and filling effects of MWCNTs, which in turn benefit the mortar’s electrical conductivity as the same way it improved the compressive strength.

Electrical resistivity of specimens

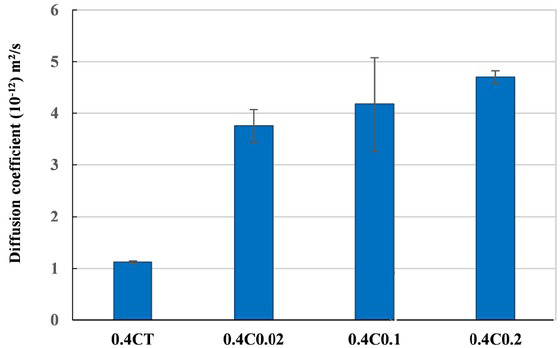

3.3 Chloride ion migration coefflcient

The results in Figure 6 show that the incorporation of MWC-NTs in mortar increased the chloride migration coefficient significantly even with the smallest MWCNT content. The chloride migration coefficient of the mortar with a slight MWCNT content (0.02 wt%) was 3.4 times of that for the control specimen without any MWCNTs. The migration of chloride ions in cement-based materials is essentially the conduction of charged particles in cement-based pore solution. The movement promotion of charged particles in pore solution was due to the presence of unevenly distributed particle chemical potential field and the directional attraction of direct current field to charged particles [18]. The incorporation of MWCNTs, as excellent conductive materials, led to the formation of numerous small electrical pathways between the pore solution and hydration products in the cement mortar, thus reducing the degree of electrical polarization and resulting in the increase of the chloride migration coefficient. Similarly, due to the continuous application of the electrified direct current electric field, the increase of the MWCNT content reduced the degree of electric polarization of cement mortar more significantly. More frequent the electromigration within the cement mortar caused more significant directional movement of chloride ions, which eventually led to the increase of chloride migration coefficient. Therefore, the chloride migration resistance of samples is not expected to take advantage of the bonding, bridging and filling effects provided by MWCNTs.

Chloride migration coefficient of the mortar with MWCNTs

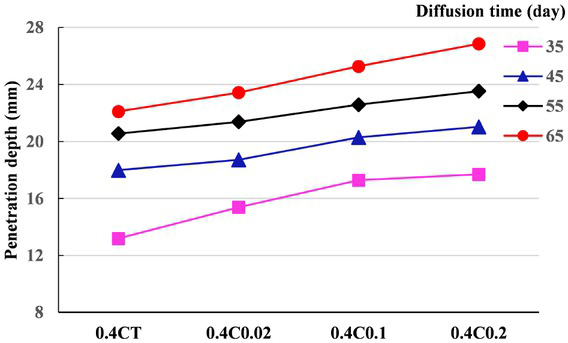

3.4 Chloride ion diffusion under natural conditions

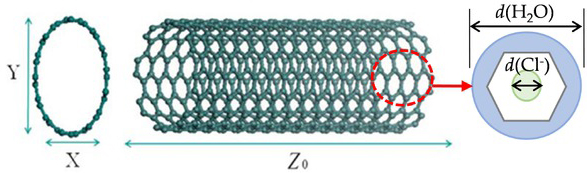

Chloride ions mainly transport into the cement-based materials by means of diffusion, capillary absorption and electromigration. Chloride ion transports usually in one or more means. The chloride diffusion depth was obtained at different diffusion periods by the natural chloride diffusion tests. In this case, chloride transport in the mortar was in the form of pure diffusion due to the water saturated state. The results in Figure 7 show that the chloride ion penetration depth was significantly larger in the mortar with MWCNTs compared to the control sample. It was also found that the chloride ion penetration depth increased with the MWCNT content. The increase was possibly due to the additional diffusion paths provided by the MWCNTs. The inside of the MWCNTs was filled with water molecules. The diameter of the water molecules is 0.4 nm, and the carbon atoms on the surface of the MWCNTs are predominantly sp2 hybridization. Moreover, the hexagonal grid structure has a certain degree of bending and form space topology, which can form a certain sp3 hybridization key [38]. In other words, most of the carbon-carbon bonds between the perfect six-carbon ring structure of carbon nanotubes are tightly connected in the form of C=C or C≡ C. Therefore, the diagonal length d(MWCNTs) = d(C≡ C) ×2 ~ d(C=C) ×2 = 0.120×2 ~ 0.134×2 = 0.240 ~ 0.268 nm, and the diameter of chloride ion is 0.099 nm. The size of the diagonal length, and diameters of water and chloride ions follow: d(Cl−) < d(MWCNTs) < d(H2O), as shown in Figure 8. The water molecules inside the carbon nanotube cannot enter or leave the wall of the carbon nanotube from the carbon six-element ring; yet, it has become the effective carrier of chloride ions for the diffusion. Moreover, the bridging effect of carbon nanotubes in mortar drove the chloride ions into the interior of the mortar matrix by directional movement, which resulted in an increase of diffusion depth with the carbon nanotube contents. However, it was difficult to confirm the theoretical explanation by experimental methods. Further microscopic observation needs to be conducted to explain the results for chloride diffusion by using advanced experimental tools in the future.

Penetration depth of mortar by natural chloride diffusion tests

Microstructure diagram of carbon nanotubes

3.5 Corrosion behavior of embedded steel bars in MWCNT mortar

When the chloride concentration around the steel reaches the critical concentration, the thin passive film on the steel surface will be damaged and the steel corrosion occurs. To investigate the corrosion behavior in the mortar with MWCNTs, two typical nonintrusive measurements—the half–cell potential measurement and the linear polarization technique—were applied in this study to test corrosion potential and corrosion rates, respectively.

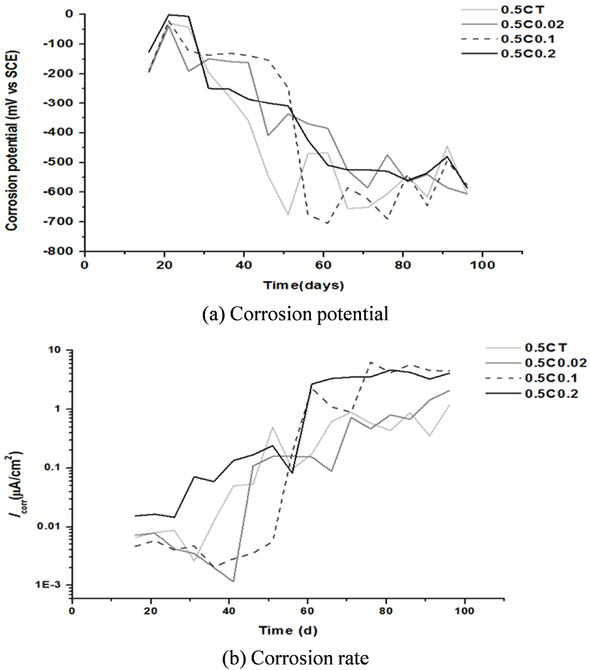

Figure 9 shows the development of the corrosion potential (Ecorr) and the corrosion rate (Icorr) of the reinforcing rebars embedded in the mortar containing 0.02, 0.1 and 0.2 wt% MWCNTs as well as the control sample. As expected, a slight increase in the steel corrosion potential was found during the 28-day curing period, as it consistently forms a passivating layer on the steel rebar surface. A substantial decrease in corrosion potential was observed when the chloride penetration and the depassivation of the steel surface began. Once the passive film of steel was destroyed, no significant differences in corrosion potential were found. The results in Figure 9(b) show that the corrosion rate increased as the corrosion potential decreased. The addition of MWCNTs increased the corrosion rate of the steel, and the increase in MWCNTs contents led to higher final corrosion rates. This was possibly because the addition of MWCNTs accelerated the chloride penetration through the mortar cover and thus the destruction of passive films on the steel surface and later pitting corrosion were more severe. Additionally, galvanic corrosion might form between steel reinforcement andMWCNTs,where corroded spots on the steel rebar acted as anode and MWCNTs acted as cathode [39, 40]. These two conductors formed a macro battery, which generated an electric couple current that increased the dissolution rate of the lower potential steel rebar (anode) and decreased the dissolution rate of the higher potential MWCNTs (cathode). As a result, the increase of MWCNTs accelerated the corrosion rate of steel rebar.

Changes in (a) corrosion potential (Ecorr) and (b) corrosion rate (Icorr) of steel rebars buried in MWCNTs cement mortar under chloride erosion environment

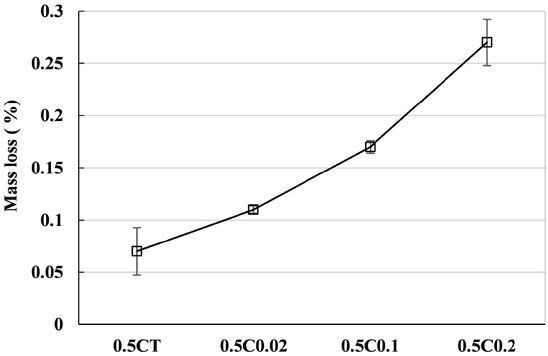

After the corrosion test, the cement mortar cover was removed in order to directly observe the corrosion degree of the reinforcement. The specific images of the corroded reinforcements in cement mortar are shown in Figure 10. As shown in Figure 10, as more carbon nanotubes were used, the corrosion on the surface of steel reinforcement became more serious. The plain bar surface of 0.5CT had a small patch of white area at the bottom of each bar with more of grayish area above, but with little rust. The steel bar’s surface of 0.5C0.02 had a little rust and its color was darker than 0.5CT. As the content of WMCNTs increased, the steel bars had more distinct rust spots on its surface. The mass loss of the steel in Figure 11 showed that the mass loss increased with the addition of MWCNTs in the cement mortar. The result agreed with the results obtained from the electrochemical measurements, showing the addition of MWCNTs presented a promoting effect on the steel corrosion.

Corrosion condition of reinforcement

Mass loss of steel

4 Conclusions

In this study, the influence of MWCNT addition on the durability of cement mortar was analyzed. Both rapid chloride migration and natural chloride diffusion tests were conducted to clarify the chloride transport properties of MWCNT mortar.Moreover, the corrosion potential and corrosion rates of steel rebars embedded in MWCNT cement pastes were studied. Based on the experimental results, the following conclusions can be drawn:

The addition of MWCNTs increases the compressive strength of Portland cement mortar after 28-day curing.

The addition of MWCNTs to cement mortar dramatically increases the chloride transport rates both in the rapid migration and natural diffusion tests.

The electrical resistivity of the mortar decreases with the addition of MWCNTs mainly because of their excellent conductivity.

The incorporation of MWCNTs into the cement mortar causes the development of higher levels of embedded steel corrosion in the chlorine environment, and the corrosion rate increases with the MWCNT content. The mass loss of the steel due to the corrosion agrees with the trend that the addition of MWCNT enhances the steel corrosion.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge the Basic Research Project of Shenzhen Knowledge Innovation Plan (Grant No. JCYJ20170818100641730) for financial support on this study.

References

[1] Salvetat JP, Bonard JM, Thomson N, Kulik A, Forro L, Benoit W, et al. Mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes. Applied Physics A. 1999;69(3):255-60.10.1007/s003390050999Search in Google Scholar

[2] Belytschko T, Xiao S, Schatz GC, Ruoff R. Atomistic simulations of nanotube fracture. Phys Rev B. 2002;65(23):235430.10.1103/PhysRevB.65.235430Search in Google Scholar

[3] Konsta-GdoutosMS, Metaxa ZS, Shah SP.Multi-scale mechanical and fracture characteristics and early-age strain capacity of high performance carbon nanotube/cement nanocomposites. Cement Concrete Comp. 2010;32(2):110-5.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2009.10.007Search in Google Scholar

[4] Kaushik BK, Goel S, Rauthan G. Future VLSI interconnects: optical fiber or carbon nanotube–a review. Microelectron Int. 2007;24(2):53-63.10.1108/13565360710745601Search in Google Scholar

[5] Zhu JH, Chen PY, Su MN, Pei C, Xing F. Recycling of carbon fibre reinforced plastics by electrically driven heterogeneous catalytic degradation of epoxy resin. Green Chem. 2019;21:1635-47.10.1039/C8GC03672ASearch in Google Scholar

[6] Sun H, Guo G, Memon SA, Xu W, Zhang Q, Zhu JH, et al. Recycling of carbon fibers from carbon fiber reinforced polymer using electrochemical method. Compos Part A: Appl S. 2015;78:10-7.10.1016/j.compositesa.2015.07.015Search in Google Scholar

[7] Chung DD. Multifunctional cement-based materials: CRC Press; 2003.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Lindvall A. Chloride ingress data from field and laboratory exposure – Influence of salinity and temperature. Cement Concrete Comp. 2007;29(2):88-93.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2006.08.004Search in Google Scholar

[9] da Costa A, Fenaux M, Fernández J, Sánchez E, Moragues A. Modelling of chloride penetration into non-saturated concrete: Case study application for real marine offshore structures. Constr Build Mater. 2013;43:217-24.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.02.009Search in Google Scholar

[10] Angst U, Elsener B, Larsen CK, Vennesland Ø. Critical chloride content in reinforced concrete — A review. Cem Concr Res. 2009;39(12):1122-38.10.1016/j.cemconres.2009.08.006Search in Google Scholar

[11] Kenny A, Katz A. Steel-concrete interface influence on chloride threshold for corrosion – Empirical reinforcement to theory. Constr Build Mater. 2020;244:118376.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118376Search in Google Scholar

[12] Hamidane Hm, Chateauneuf A, Messabhia A, Ababneh A. Reliability analysis of corrosion initiation in reinforced concrete structures subjected to chlorides in presence of epistemic uncertainties. Structural Safety. 2020;86:101976.10.1016/j.strusafe.2020.101976Search in Google Scholar

[13] Chung D. Cement reinforced with short carbon fibers: a multifunctional material. Compos Part B: Eng. 2000;31(6-7):511-26.10.1016/S1359-8368(99)00071-2Search in Google Scholar

[14] Garcés P, Andión LG, Dela Varga I, Catalá G, Zornoza E. Corrosion of steel reinforcement in structural concrete with carbon material addition. Corros Sci. 2007;49(6):2557-66.10.1016/j.corsci.2006.12.009Search in Google Scholar

[15] Garces P, Andrade M, Saez A, Alonso M. Corrosion of reinforcing steel in neutral and acid solutions simulating the electrolytic environments in the micropores of concrete in the propagation period. Corros Sci. 2005;47(2):289-306.10.1016/j.corsci.2004.06.004Search in Google Scholar

[16] Garcés P, Fraile J, Vilaplana-Ortego E, Cazorla-Amorós D, Alcocel EG, Andión LG. Effect of carbon fibres on the mechanical properties and corrosion levels of reinforced portland cement mortars. Cement Concrete Res. 2005;35(2):324-31.10.1016/j.cemconres.2004.05.013Search in Google Scholar

[17] Garcés P, Zornoza E, Alcocel EG, Galao O, Andión LG. Mechanical properties and corrosion of CAC mortars with carbon fibers. Constr Build Mater. 2012;34:91-6.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.02.020Search in Google Scholar

[18] Konsta-GdoutosMS, Aza CA. Self sensing carbon nanotube (CNT) and nanofiber (CNF) cementitious composites for real time damage assessment in smart structures. Cement and Concrete Composites. 2014;53:162-9.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2014.07.003Search in Google Scholar

[19] Li GY, Wang PM, Zhao X. Pressure-sensitive properties and microstructure of carbon nanotube reinforced cement composites. Cement Concrete Comp. 2007;29(5):377-82.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2006.12.011Search in Google Scholar

[20] del Carmen Camacho M, Galao O, Baeza F, Zornoza E, Garcés P. Mechanical properties and durability of CNT cement composites. Materials. 2014;7(3):1640-51.10.3390/ma7031640Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Luo JL, Duan ZD, Zhao TJ, Li QY, editors. Effect of compressive strain on electrical resistivity of carbon nanotube cement-based composites. Key Eng Mater; 2011: Trans Tech Publ.10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.483.579Search in Google Scholar

[22] Konsta-Gdoutos MS, Metaxa ZS, Shah SP. Highly dispersed carbon nanotube reinforced cement based materials. Cement Concrete Res. 2010;40(7):1052-9.10.1016/j.cemconres.2010.02.015Search in Google Scholar

[23] Singh V, Singh R. Effect of Polyvinyl Pyrrolidone on Strength and Some Other Properties of Cement. Trans Indian Ceram Soc. 2006;65(1):41-8.10.1080/0371750X.2006.11012224Search in Google Scholar

[24] Treacy MJ, Ebbesen T, Gibson J. Exceptionally high Young’s modulus observed for individual carbon nanotubes. Nature. 1996;381(6584):678.10.1038/381678a0Search in Google Scholar

[25] LiW, JiW, Torabian Isfahani F,Wang Y, Li G, Liu Y, et al. Nano-silica sol-gel and carbon nanotube coupling effect on the performance of cement-based materials. Nanomaterials. 2017;7(7):185.10.3390/nano7070185Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Azhari F, Banthia N. Cement-based sensors with carbon fibers and carbon nanotubes for piezoresistive sensing. Cement Concrete Comp. 2012;34(7):866-73.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2012.04.007Search in Google Scholar

[27] NORDTEST. Chloride migration coefficient from non-steady-state migration experiments. Finland: Nordtest; 1999.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Alcocel E, Garcés P, Martínez J, Payá J, Andión L. Effect of sewage sludge ash (SSA) on the mechanical performance and corrosion levels of reinforced Portland cement mortars. Mater Construcc. 2006;56(282):31-43.10.3989/mc.2006.v56.i282.25Search in Google Scholar

[29] Zornoza E, Garcés P, Payá J. Corrosion rate of steel embedded in blended Portland and fluid catalytic cracking catalyst residue (FC3R) cement mortars. Mater Construcc. 2008;58(292):27-43.10.3989/mc.2008.39006Search in Google Scholar

[30] Zornoza E, Garcés P, Payá J, Climent M. Improvement of the chloride ingress resistance of OPC mortars by using spent cracking catalyst. Cement Concrete Res. 2009;39(2):126-39.10.1016/j.cemconres.2008.11.006Search in Google Scholar

[31] Zornoza E, Payá J, Garcés P. Chloride-induced corrosion of steel embedded in mortars containing fly ash and spent cracking catalyst. Corros Sci. 2008;50(6):1567-75.10.1016/j.corsci.2008.02.001Search in Google Scholar

[32] Zornoza E, Payá J, Garcés P. Carbonation rate and reinforcing steel corrosion rate of OPC/FC3R/FA mortars under accelerated conditions. Adv Cem Res. 2009;21(1):15-22.10.1680/adcr.2007.00008Search in Google Scholar

[33] Andrade C, González J. Quantitative measurements of corrosion rate of reinforcing steels embedded in concrete using polarization resistance measurements. Mater Corros. 1978;29(8):515-9.10.1002/maco.19780290804Search in Google Scholar

[34] Hawreen A, Bogas J, Dias AJC,Materials B. On the mechanical and shrinkage behavior of cement mortars reinforced with carbon nanotubes. Constr Build Mater. 2018;168:459-70.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.02.146Search in Google Scholar

[35] Lee HS, Balasubramanian B, Gopalakrishna G, Kwon SJ, Karthick S, Saraswathy VJC, et al. Durability performance of CNT and nanosilica admixed cement mortar. Constr Build Mater. 2018;159:463-72.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.11.003Search in Google Scholar

[36] Siddique R, Mehta AJC, Materials B. Effect of carbon nanotubes on properties of cement mortars. Constr Build Mater. 2014;50:116-29.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.09.019Search in Google Scholar

[37] Li WW, Ji WM, Fang GH, Liu YQ, Xing F, Liu YK, et al. Electrochemical impedance interpretation for the fracture toughness of carbon nanotube/cement composites. Constr Build Mater. 2016;114:499-505.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.03.215Search in Google Scholar

[38] Iijima S. Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon. Nature. 1991;354(6348):56.10.1038/354056a0Search in Google Scholar

[39] Del Moral B, Galao O, Antón C, Climent M, Garcés PJMdC. Usability of cement paste containing carbon nanofibres as an anode in electrochemical chloride extraction from concrete. Mater Construcc. 2013;63(309):39-48.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Turhan MC, Li Q, Jha H, Singer RF, Virtanen SJEA. Corrosion behaviour of multiwall carbon nanotube/magnesium composites in 3.5% NaCl. Electrochim Acta. 2011;56(20):7141-8.10.1016/j.electacta.2011.05.082Search in Google Scholar

© 2020 W. Li et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Microstructure and compressive behavior of lamellar Al2O3p/Al composite prepared by freeze-drying and mechanical-pressure infiltration method

- Al3Ti/ADC12 Composite Synthesized by Ultrasonic Chemistry in Situ Reaction

- Microstructure and photocatalytic performance of micro arc oxidation coatings after heat treatment

- The effect of carbon nanotubes on the mechanical and damping properties of macro-defect-free cements

- Toughening Mechanism of the Bone — Enlightenment from the Microstructure of Goat Tibia

- Characterization of PVC/MWCNTs Nanocomposite: Solvent Blend

- Study on Macroscopic and Mesoscopic Mechanical Behavior of CSG based on Inversion of Mesoscopic Material Parameters

- Bearing properties and influence laws of concrete-filled steel tubular arches for underground mining roadway support

- Comparing Test Methods for the Intra-ply Shear Properties of Uncured Prepreg Tapes

- Investigation of Microstructural, Mechanical and Corrosion Properties of AA7010-TiB2 in-situ Metal Matrix Composite

- A Comparative Study of Structural Changes in Conventional and Unconventional Machining and Mechanical Properties Evaluation of Polypropylene Based Self Reinforced Composites

- Research on Influence mechanism of composite interlaminar shear strength under normal stress

- Mechanical properties of geopolymer foam at high temperature

- Synthesis and mechanical properties of nano-Sb2O3/BPS-PP composites

- Multiscale acoustic emission of C/SiC mini-composites and damage identification using pattern recognition

- Modifying mechanical properties of Shanghai clayey soil with construction waste and pulverized lime

- Relationship between Al2O3 Content and Wear Behavior of Al+2% Graphite Matrix Composites

- Static mechanical properties and mechanism of C200 ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC) containing coarse aggregates

- A Parametric Study on the Elliptical hole Effects of Laminate Composite Plates under Thermal Buckling Load

- Morphology and crystallization kinetics of Rubber-modified Nylon 6 Prepared by Anionic In-situ Polymerization

- Effects of Elliptical Hole on the Correlation of Natural Frequency with Buckling Load of Basalt Laminates Composite Plates

- Effect of interphase parameters on elastic modulus prediction for cellulose nanocrystal fiber reinforced polymer composite

- Mixed Matrix Membranes prepared from polysulfone and Linde Type A zeolite

- Fabrication and low-velocity impact response of pyramidal lattice stitched foam sandwich composites

- Design and static testing of wing structure of a composite four-seater electric aircraft

- CSG Elastic Modulus Model Prediction Considering Meso-components and its Effect

- Optimization of spinning parameters of 20/316L bimetal composite tube based on orthogonal test

- Chloride-induced corrosion behavior of reinforced cement mortar with MWCNTs

- Statistical Law and Predictive Analysis of Compressive Strength of Cemented Sand and Gravel

- Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio of the deformable cement adhesives

- Reverse localization on composite laminates using attenuated strain wave

- Impact of reinforcement on shrinkage in the concrete floors of a residential building

- Novel multi-zone self-heated composites tool for out-of-autoclave aerospace components manufacturing

- Effect of notch on static and fatigue properties of T800 fabric reinforced composites

- Electrochemical Discharge Grinding of Metal Matrix Composites Using Shaped Abrasive Tools Formed by Sintered Bronze/diamond

- Fabrication and performance of PNN-PZT piezoelectric ceramics obtained by low-temperature sintering

- The extension of thixotropy of cement paste under vibration: a shear-vibration equivalent theory

- Conventional and unconventional materials used in the production of brake pads – review

- Inverse Analysis of Concrete Meso-constitutive Model Parameters Considering Aggregate Size Effect

- Finite element model of laminate construction element with multi-phase microstructure

- Effect of Cooling Rate and Austenite Deformation on Hardness and Microstructure of 960MPa High Strength Steel

- Study on microcrystalline cellulose/chitosan blend foam gel material

- Investigating the influence of multi-walled carbon nanotubes on the mechanical and damping properties of ultra-high performance concrete

- Preparation and properties of metal textured polypropylene composites with low odor and low VOC

- Calculation Model for the Mixing Amount of Internal Curing Materials in High-strength Concrete based on Modified MULTIMOORA

- Electric degradation in PZT piezoelectric ceramics under a DC bias

- Cushioning energy absorption of regular polygonal paper corrugation tubes under axial drop impact

- Erratum

- Study on Macroscopic and Mesoscopic Mechanical Behavior of CSG based on Inversion of Mesoscopic Material Parameters

- Effect of interphase parameters on elastic modulus prediction for cellulose nanocrystal fiber reinforced polymer composite

- Statistical Law and Predictive Analysis of Compressive Strength of Cemented Sand and Gravel

- Retraction

- Assessment of nano-TiO2 and class F fly ash effects on flexural fracture and microstructure of binary blended concrete

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Microstructure and compressive behavior of lamellar Al2O3p/Al composite prepared by freeze-drying and mechanical-pressure infiltration method

- Al3Ti/ADC12 Composite Synthesized by Ultrasonic Chemistry in Situ Reaction

- Microstructure and photocatalytic performance of micro arc oxidation coatings after heat treatment

- The effect of carbon nanotubes on the mechanical and damping properties of macro-defect-free cements

- Toughening Mechanism of the Bone — Enlightenment from the Microstructure of Goat Tibia

- Characterization of PVC/MWCNTs Nanocomposite: Solvent Blend

- Study on Macroscopic and Mesoscopic Mechanical Behavior of CSG based on Inversion of Mesoscopic Material Parameters

- Bearing properties and influence laws of concrete-filled steel tubular arches for underground mining roadway support

- Comparing Test Methods for the Intra-ply Shear Properties of Uncured Prepreg Tapes

- Investigation of Microstructural, Mechanical and Corrosion Properties of AA7010-TiB2 in-situ Metal Matrix Composite

- A Comparative Study of Structural Changes in Conventional and Unconventional Machining and Mechanical Properties Evaluation of Polypropylene Based Self Reinforced Composites

- Research on Influence mechanism of composite interlaminar shear strength under normal stress

- Mechanical properties of geopolymer foam at high temperature

- Synthesis and mechanical properties of nano-Sb2O3/BPS-PP composites

- Multiscale acoustic emission of C/SiC mini-composites and damage identification using pattern recognition

- Modifying mechanical properties of Shanghai clayey soil with construction waste and pulverized lime

- Relationship between Al2O3 Content and Wear Behavior of Al+2% Graphite Matrix Composites

- Static mechanical properties and mechanism of C200 ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC) containing coarse aggregates

- A Parametric Study on the Elliptical hole Effects of Laminate Composite Plates under Thermal Buckling Load

- Morphology and crystallization kinetics of Rubber-modified Nylon 6 Prepared by Anionic In-situ Polymerization

- Effects of Elliptical Hole on the Correlation of Natural Frequency with Buckling Load of Basalt Laminates Composite Plates

- Effect of interphase parameters on elastic modulus prediction for cellulose nanocrystal fiber reinforced polymer composite

- Mixed Matrix Membranes prepared from polysulfone and Linde Type A zeolite

- Fabrication and low-velocity impact response of pyramidal lattice stitched foam sandwich composites

- Design and static testing of wing structure of a composite four-seater electric aircraft

- CSG Elastic Modulus Model Prediction Considering Meso-components and its Effect

- Optimization of spinning parameters of 20/316L bimetal composite tube based on orthogonal test

- Chloride-induced corrosion behavior of reinforced cement mortar with MWCNTs

- Statistical Law and Predictive Analysis of Compressive Strength of Cemented Sand and Gravel

- Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio of the deformable cement adhesives

- Reverse localization on composite laminates using attenuated strain wave

- Impact of reinforcement on shrinkage in the concrete floors of a residential building

- Novel multi-zone self-heated composites tool for out-of-autoclave aerospace components manufacturing

- Effect of notch on static and fatigue properties of T800 fabric reinforced composites

- Electrochemical Discharge Grinding of Metal Matrix Composites Using Shaped Abrasive Tools Formed by Sintered Bronze/diamond

- Fabrication and performance of PNN-PZT piezoelectric ceramics obtained by low-temperature sintering

- The extension of thixotropy of cement paste under vibration: a shear-vibration equivalent theory

- Conventional and unconventional materials used in the production of brake pads – review

- Inverse Analysis of Concrete Meso-constitutive Model Parameters Considering Aggregate Size Effect

- Finite element model of laminate construction element with multi-phase microstructure

- Effect of Cooling Rate and Austenite Deformation on Hardness and Microstructure of 960MPa High Strength Steel

- Study on microcrystalline cellulose/chitosan blend foam gel material

- Investigating the influence of multi-walled carbon nanotubes on the mechanical and damping properties of ultra-high performance concrete

- Preparation and properties of metal textured polypropylene composites with low odor and low VOC

- Calculation Model for the Mixing Amount of Internal Curing Materials in High-strength Concrete based on Modified MULTIMOORA

- Electric degradation in PZT piezoelectric ceramics under a DC bias

- Cushioning energy absorption of regular polygonal paper corrugation tubes under axial drop impact

- Erratum

- Study on Macroscopic and Mesoscopic Mechanical Behavior of CSG based on Inversion of Mesoscopic Material Parameters

- Effect of interphase parameters on elastic modulus prediction for cellulose nanocrystal fiber reinforced polymer composite

- Statistical Law and Predictive Analysis of Compressive Strength of Cemented Sand and Gravel

- Retraction

- Assessment of nano-TiO2 and class F fly ash effects on flexural fracture and microstructure of binary blended concrete