Abstract

In this paper, C200 ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC) containing coarse aggregate was prepared. Firstly, four different maximum size and three different type of coarse aggregate having significant differences in strength, surface texture, porosity and absorption were used to prepared the mixtures. Secondly, the effect of maximum size and type of coarse aggregate on the workability of the fresh UHPC and the mechanical behaviour of harden UHPC were investigated. Finally, a series micro-tests including mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP), scanning electron microscope (SEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD) were conducted and the mechanism of the C200 UHPC were discussed.

The results show that the type and maximum size of coarse aggregate have significant effect on the workability and mechanical properties of C200 UHPC. The basalt coarse aggregate with maximum size of 10mm can be used to prepare the C200 UHPC. The compressive strength and flexural strength of the C200 UHPC is 203MPa and 46MPa at 90 day, respectively. Besides, the micro-tests data show that the C200 UHPC has a compacted matrix and strong interface transition zone (ITZ), which make the aggregate potential strength fully used.

1 Introduction

Reactive powder concrete (RPC) is an advanced cement based material, which can be divided into RPC200 and RPC800 [1, 2, 3, 4]. The compressive strength of RPC200 is between 150MPa and 200MPa, flexural strength ranges from 20MPa to 50MPa and fracture energies varies between 15,000J/m2 and 40,000J/m2 [1, 2]. Obviously, RPC possess the ultra-high mechanical properties,which has a great potential prospect in the fields of civil, pavement, bridge and protective shelter of military engineering [5, 6].

It is well known that the RPC is composited of a high dosage of cement (generally over 800kg/m3), very fine powder (such as crushed quartzite and silica fume) and steel fiber [1, 2]. Obviously, these expensive raw materials are responsible for the high production cost. In addition, the rigorous curing regimes usually employed in the fabrication of RPC (200∘C autoclave curing or 90∘C heating curing) result in a low production efficiency and high energy consumption. Moreover, for the enhancement homogeneity, the coarse aggregates are eliminated in RPC [1]. However, the coarse aggregate is the main composite part in normal strength concrete, which is up to approximately 40 percent of the total volume. The elimination of the coarse aggregate means the much higher amount of cementitious dosage in the RPC. This may leads to sharp increase in shrinkage, creep, hydration heat and the production cost of the RPC. Furthermore, increased shrinkage characteristics and high sensitive microcracking may reduce its early age and hardened performance. Therefore, how to reduce production cost and energy consumption, simplify the manufacturing process, eliminating the negative effective caused by the high amount of cementitious dosage are the key problems for the application of RPC in practical engineering.

Our previous studies [6, 7, 8, 9, 10] have been discussed the preparation of C200 ultra-high performance (UHPC) as the following methods. Firstly, a large amount of Portland cement (PC≥ 50%) was replaced by a cheap industrial mineral admixture of fly ash (FA), slag (SL) and silica fume (SF). Secondly, the natural river sand with the maximum diameter of 3mm was substituted for the costly ultra-fine quartz sand. Finally, the standard curing (20 and 100% relative humidity) took the place of 200 autoclave curing or 90 heating curing. According to the above method, the C200 UHPC with lower energy consumption, lower production cost and easier operation was successfully prepared.

In this paper, production of C200 UHPC containing coarse aggregate without any performance loss compared to the conventional RPC was investigated. Firstly, four different maximum size and three different type of coarse aggregate having significant differences in strength, surface texture, porosity and absorption wereused to prepared the mixtures. Secondly, the effect of maximum size and type of coarse aggregate on the workability of the fresh UHPC and the mechanical behaviour of harden UHPC were investigated. Finally, a series micro-tests including mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP), scanning electron microscope (SEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD) were conducted and the mechanism of the green C200 UHPC were discussed.

2 Experimental

2.1 Raw materials

Four types of cementitious materials were used in this study: Portland cement (PC) with 28 days of compressive strength of 68.9MPa, silica fume (SF), fly ash (FA) and slag (SL). Their chemical compositions and physical properties are shown in Table 1.

Chemical composition and physical properties of cementitious materials

| Chemical composition (%) | PC | SF | FA | SL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 20.6 | 94.5 | 55.0 | 34.2 |

| Fe2O3 | 4.4 | 0.8 | 5.9 | 0.4 |

| MgO | 5.0 | 0.3 | 31.3 | 14.2 |

| Al2O3 | 5.0 | 0.3 | 31.3 | 14.2 |

| CaO | 65.1 | 0.5 | 3.9 | 41.7 |

| SO3 | 2.2 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.0 |

| LOI | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.7 |

| Specific surface area (m2/kg) | 417 | 2200 | 686 | 766 |

| Specific gravity (k/cm3) | 3.08 | 1.84 | 2.61 | 2.63 |

The natural river sand with the maximum size of 3mm was used to replace the ultra-fine quartz sand, which is a necessary component to produce RPC reported by published literatures. Three different types of coarse aggregate were used: crushed granitic (CG), crushed basalt (CB) and crushed iron ore (CI). These aggregates were selected because they present significant differences in strength, surface texture, porosity and absorption and bond strength. The CG presents irregular shape, rough texture, and low absorption. The CB also has an irregular shape and rough texture. The CI has a rough surface texture and the highest density. The same particle size distribution was adopted with a maximum aggregate size of 10mm. Compressive strength, relative density, porosity and water absorption ratio index of the aggregate rocks were presented in Table 2.

Properties of coarse aggregates

| aggregate | Compressive | Relative density | Porosity (%) | Maximum size(mm) | water absorption (% of dry mass) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Granitic | 144 | 2.64 | 0.13 | 10 | 0.28 |

| Basalt | 203 | 2.90 | 0.45 | 10 | 0.54 |

| Basalt | 203 | 2.90 | 0.45 | 5 | 0.54 |

| Basalt | 203 | 2.90 | 0.45 | 10 | 0.54 |

| Basalt | 203 | 2.90 | 0.45 | 15 | 0.54 |

| Basalt | 203 | 2.90 | 0.45 | 20 | 0.54 |

| Iron ore | 192 | 4.80 | 0.26 | 10 | 2.20 |

2.2 Mix-design

Seven mixtures, one reference mixture (RM) without coarse aggregate and six mixtures with different coarse aggregates were designed. The water-binder ratio and sand-binder ratio of all mixtures was 0.16 and 1.0, respectively. For cementitious binder, 50% of Portland cement was replaced by ternary mineral admixtures composited of 10% silica fume, 20% fly ash and 20% slag. A polycarboxylic type superplasticizer with water reducing ratio of 40% was adopted to ensure the workability. The dosage of super-plasticizerwas kept at 2.5%weight of total binder. To avoid brittle fracture, 3% by volume brass coated steel fibers with 6mm length and a diameter of 0.15mm were used; the tensile strength of the fibers is 2200Mpa. The mixture proportions are shown in Table 3.

Mixtures proportions (kg/m3)

| Mix No | water | Cement | Silica fume | Fly ash | Slag | Sand | Coarse aggregate | Steel fiber | SP | Maximum of aggregate size (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RM | 164 | 512 | 102.4 | 204.8 | 204.8 | 1024 | - | 300 | 25.6 | - |

| AT-G | 128 | 400 | 80 | 160 | 160 | 800 | 728 | 234 | 20 | 10 |

| AT-B | 128 | 400 | 80 | 160 | 160 | 800 | 800 | 234 | 20 | 10 |

| AT-I | 128 | 400 | 80 | 160 | 160 | 800 | 1335 | 234 | 20 | 10 |

| AS-10 | 128 | 400 | 80 | 160 | 160 | 800 | 800 | 234 | 20 | 10 |

| AS-15 | 128 | 400 | 80 | 160 | 160 | 800 | 800 | 234 | 20 | 15 |

| AS-20 | 128 | 400 | 80 | 160 | 160 | 800 | 800 | 234 | 20 | 20 |

The AT-G, AT-B, AT-I were designed to investigate the aggregate type (AT) on the influence of the ultra-high performance cementitious materials. The AS-10, AS-15 and AS-20 were used to study the effect of aggregate size (AS). The three different maximum aggregate size of 10mm, 15mm and 20mm were investigated. As the aim of the study is the effect of aggregate type and maximum aggregate size, the volume fraction of coarse aggregate has to remain constant and has been chosen to a value of 27.5%.

2.3 Specimens preparation

The cementitious materials (Portland cement, silica fume, fly ash and slag) and river sand were first dry-mixed for 1 minute. Then the mixture of water and surperplasticizer was added and mixed for 3 minutes. After that, the steel fiber was sprinkled slowly into cementitious mixture and mixed for another 3 min to make the steel fiber homogenously distributed through the fresh mortar. Finally, the coarse aggregates were poured into cementitious mixture and mixed for another 1 minutes. Then, the fresh C200 UHPC was cast into steel moulds and compacted by a vibrating table. The specimens were de-moulded after 24 hours, and then cured in the condition of 20∘C and 98% relative humidity.

2.4 Testing methods

2.4.1 Slump tests

Fresh UHPC mixture properties were determined using the slump test for workability in accordance with China code of GB/T 50080-2016 [11]. The testing apparatus consisted of a normal slump cone and a steel plate with dimensions of 1000mm×1000mm.

2.4.2 Static tests

A closed-loop servo-controlled material testing machine (MTS) was used to conduct compressive and flexural test. The compressive strength test was performed on 100×100×100mm cubic specimens and the loading rate was 1Mpa/s. Flexural strength test was performed on 100×100×400mm prismatic specimens by using third-point loading and the span length of the specimen was 300mm , which is in accordance with China code of GB/T 50081-2002 [12].

The compressive strength and flexural strength of C200 UHPC were conducted on 7, 14, 28 and 90 days age. Three specimens of each batch were tested and the average value was served as the final compressive strength and flexural strength.

2.4.3 Microscopic test

In order to investigate the detail of the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) between the aggregate and paste, the MIP, SEM and XRD measurement were conducted. After the static test, the sample were obtain from the broken specimens. The hydration reaction of the cement paste was stopped by crushing the specimens into pieces of about 3-5mm size, and then immersing them in acetone for 24h. After that the paste sample was dried at 40∘C for 3h, and next placed in vacuum desiccators for 2 days, and then used for testing.

The specimens for SEM were mounted onto aluminium stubs using double-sided adhesive carbon discs and coated with gold. To ensure that electrical charge surfaces, a line of silver paint was applied connecting the specimen sides to the stub.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Workability

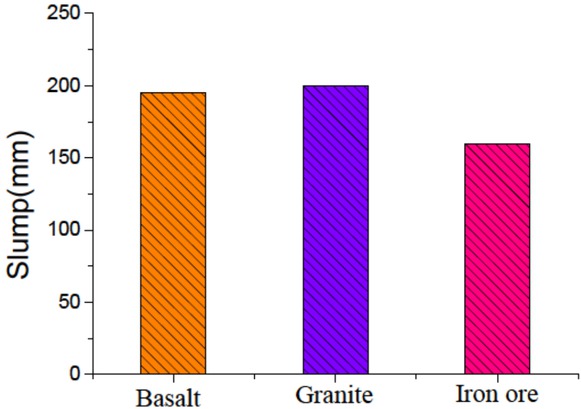

The slump of the ultra-high performance cementitious composite with different type of aggregate are shown in Figure 1. It clearly can be seen in Figure 1 that the AT-B and AT-G has a slump of 195mm and 200mm, respectively. However, AT-I mixture which containing iron ore showed the lowest slump of 160mm. This may be attributed to the fact that iron ore aggregate has the highest water absorption capacity than other coarse aggregate. Just as shown in Table 2, the water absorption of CG, CB and CI is 0.28%, 0.54% and 2.2%, respectively. Therefore, more free water are absorbed into iron ore aggregate, thus reduce slump of AT-I mixture.

Influence of aggregate type on workability

Besides, the density of the iron ore is 4.8g/cm3, which is larger than the density of basalt and granitic. Therefore, the heavy coarse aggregate of iron ore precipitated when conducting the slump test. The precipitation of the iron ore coarse aggregate may block the flow of the mixture.

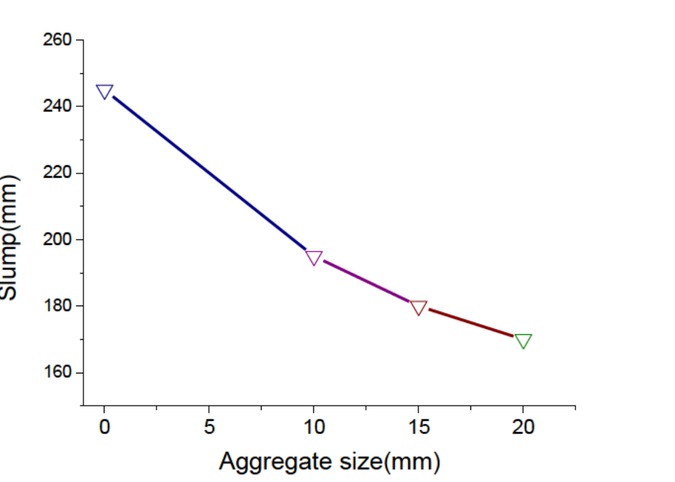

The slump of the mixture with different maximum size of coarse aggregate are shown in Figure 2. The Figure 2 indicates that the slump values of the mixtures with smaller maximum size of coarse aggregates is higher than that with lager maximum size of coarse aggregate. This agrees with the study carried out by Uysal [13] and Szczesniak et al. [14] who investigate the self-compacting concrete (SCC).

Influence of coarse aggregate size on workability

This phenomenon is reversed with the normal strength concrete (NSC). For a given aggregate fraction in the NSC, the workability improves as the size of the maximum aggregate particles increases, probably because of the decrease in specific surface [15]. This difference may be attributed to the different volume fraction of the paste between the C200 UHPC and NSC. Just as shown in Table 2, the volume fraction of paste in C200 UHPC is about 50%. It is well known that the volume fraction of the paste in NSC is just only 15%. Therefore, there is much excess paste in the C200 UHPC even with the small maximum size of coarse aggregate.

3.2 Compressive strength

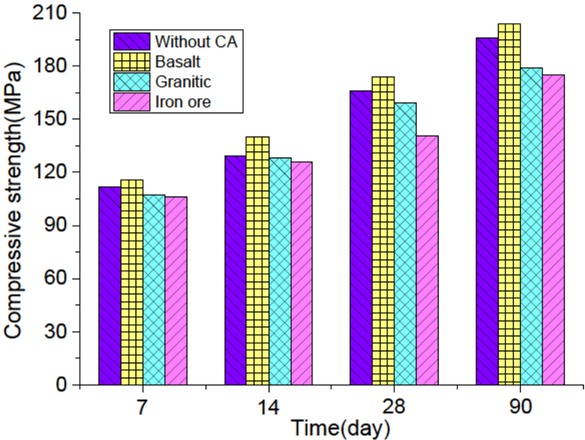

The compressive strength development of UHPC mixtures without and with various types of coarse aggregates are presented in Figure 3. The data in Figure 3 indicates that the use of coarse aggregate have obvious influence on the compressive strength of UHPC. Just as shown in Figure 3, the compressive strength of UHPC with basalt aggregate is 203MPa, which is higher than the 196MPa of UHPC without aggregate.However, the compressive strength of UHPC with granitic and iron ore coarse aggregate is 179MPa and 175MPa, respectively. Therefore, it can be concluded that the basalt coarse aggregate have the positive effect on the compressive strength of UHPC. This phenomenon is different from the normal strength concrete. For normal-strength concrete, the effect of the type of coarse aggregate on the compressive strength is not significant [16].

Influence of coarse aggregate type on compressive strength

It is well known that concrete is a composite, and its properties depend on the properties of the component phases (paste matrix and aggregate) and the inter-facial transition zone (ITZ) between them. For the normal strength concrete, the compressive strength of paste matrix is low and the ITZ is weak [17]. The cracks exist in ITZ is a considerable extent before the concrete subjected to any external load. Under load, these small or microscopic cracks extend and interconnect, until, at ultimate load, the whole internal structure is completely disrupted [16]. The aggregate had, in comparison with concrete, relatively high strength and their potential strength was not fully used. Therefore, the type of the coarse aggregate has not obvious effect on the compressive strength of normal strength concrete. However, in UHPC, the strength of paste matrix and ITZ are extremely improved because of the very low water-to-binder ratio and the use of the mineral admixture including silica fume, fly ash and slag (the enhancement mechanism of UHPC ITZ will be discussed in section 3.4). Under load, the cracks may extend through the aggregate, which make use of the full strength potential of the coarse aggregate particles, just as shown in Figure 4. Therefore, the coarse aggregate presents positive effect in the strength of UHPC.

Fracture of the specimen

Besides, the data in Figure 3 also reveal that the type of coarse aggregate has a significant effect on the compressive strength of UHPC. The highest compressive strength of 203MPa were measured in UHPC mixture presented with basalt aggregate while the lowest compressive strength of 175MPa were noted in mixture prepared with iron ore coarse aggregate at 90d. The highest compressive strength of AT-B may attribute to the hard texture and rough surface of the basalt. For the AT-I, just as the discussion in section 3.1, it is hard to fabricate a homogenous UHPC mixturewhen adding the iron ore aggregate because of its high density.

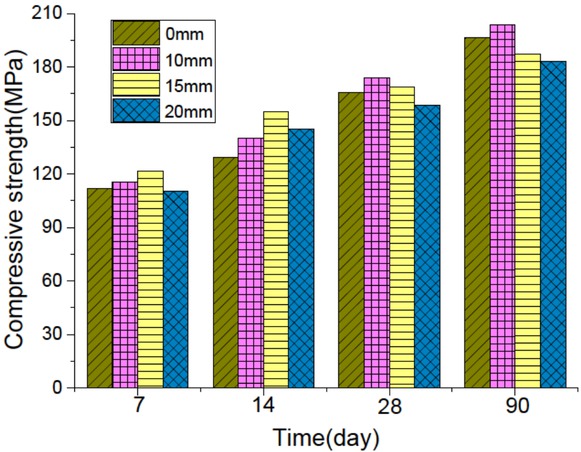

The compressive strength of four UHPC with different maximum size of basalt coarse aggregate are shown in Figure 5, the test results indicate that the maximum size of coarse aggregate has a significant influence on the compressive strength of UHPC. The UHPC with maximum size of 15mm presents the highest compressive strength than other size at early curing age (7d and 14d). However, the UHPC with maximum size of 10mm shows the highest compressive strength at later curing age (28d and 90d). Besides, the compressive strength of the UHPC with 10mm maximum size of coarse aggregate is 4.0% higher than the UHPC without aggregate. But the compressive strength of UHPC with 15mm and 20mm maximum size of aggregate is 4.5% and 6.6% lower than reference mixture, respectively. It can be concluded that the proper maximum size of coarse aggregate is helpful for the compressive strength of UHPC, but too large size of coarse aggregate tends to reduce UHPC strength. This is in agreement with the results of high performance concrete tests conducted by Aulia and Deutschmann [18].

Influence of maximum size of aggregate on compressive strength

This is due to the smaller maximum size of coarse aggregate that has the larger surface area that results in a higher bonding strength in the transition zone around aggregate particles when UHPC is under loading [14]. The bond with large particles tends to be weaker than small particle due to smaller surface area-to-volume ratios. The increase in strength with lower diameter can probably be attributed to a change in the stress repartition inside the specimen. Each aggregate, which acts as a rather rigid inclusion inside a deformable matrix, will tend to restrain the contraction of the matrix under compressive load, comparatively to a specimen without rigid inclusions. Consequently, it will lead to a development of a locally non homogenous state of stresses around each inclusion, which depends on the aggregate diameter [19].

3.3 Flexural strength

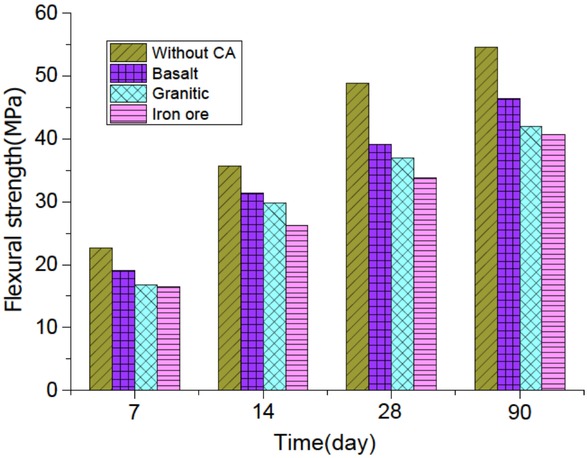

Figure 6 shows the variation of flexural strength with age for the UHPC specimens prepared with the three types of aggregates selected for this study. As expected, the flexural strength increased with age in all of the UHPC specimens. Further, the data in Figure 6 indicate that the addition of coarse aggregate also has a significant effect on the flexural strength of UHPC. However, the effect is negative, which is different from the compressive strength discussed previously. Taking the 90d for example, the compressive strength of UHPC without coarse aggregate is 54.5MPa, which is 15%, 22.9% and 25.3% higher than that with basalt, granitic and iron ore coarse aggregate, respectively. The least flexural strength of specimens is the UHPC prepared with iron ore aggregate. This situation corresponds well with the normal strength concrete. Popovics [20] pointed out that the higher the elastic modulus of aggregate, the lower the flexural strength. Kaplan [21] also found that aside from texture and shape the modulus of elasticity that most affects compressive and flexural strengths of concrete. This may be attributed to the fact that too stiff an aggregate, though improving modulus,may cause stress concentration and initiate more mirocracking causing a decrease in strength [22].

Influence of coarse aggregate type on flexural strength

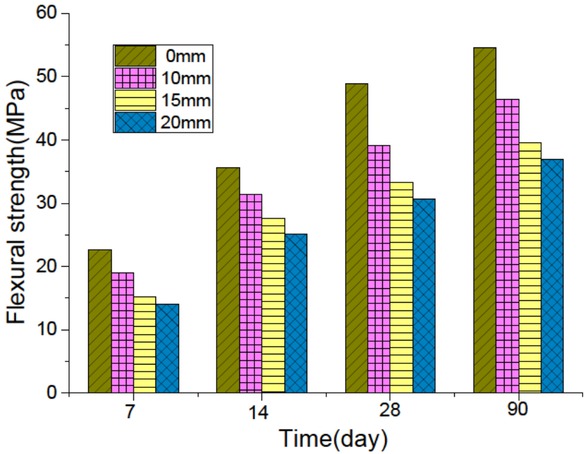

Figure 7 shows the flexural strength of UHPC with different maximum size of basalt coarse aggregate. Note that in all cases, the flexural strength of UHPC with coarse aggregate is lower than without coarse aggregate, and the flexural strength seems to decrease as the aggregate size increases in all curing ages. Take 90d for example, the flexural strength of UHPC without coarse aggregate is 14.9%, 27.5% and 32.1% higher than UHPC with maximum size of 10mm, 15mm and 20mm coarse aggregates, respectively. This situation is different from the effect of maximum size of coarse aggregate on the compressive strength.

Influence of coarse aggregate size on flexural strength

This trend, a decrease of the flexural strength with aggregate size increase, was also observed in normal strength concretes, as reported by Tasdemir et al. [23] and Li et al. [24]. However, tests performed by Chen and Liu [25, 26] on high-strength concretes show a reverse tendency with tensile strength increasing with the aggregate size.

The decrease of UHPC flexural strength as increase of maximum size of coarse aggregate may be explained by the followings. Although larger aggregates require less mixing water than smaller aggregates, the transition zone around larger aggregate is weaker. The larger aggregates provide larger fracture surfaces and more complicated cracking paths. Metha et al. [15] pointed out that the inter-facial transition zone characteristics tend to affect tensile and flexural strength to a greater degree than compressive strength.

Basis on the above discussion of the mechanical properties, it can be concluded that the new UHPC may be prepared without any performance loss by use basalt coarse aggregate with maximum size of 10mm.

3.4 Microstructure of the UHPC

It clearly can be seen from the above discussion that the type and maximum size of coarse aggregate have significant influence on mechanical properties of UHPC. However, those influences are different from it in conventional concrete. In order to reveal the mechanism of UHPC, a series of micro-tests were conducted. For the comparison between UHPC and NSC, the NSC with water-cement ratio of 0.40 was specially prepared.

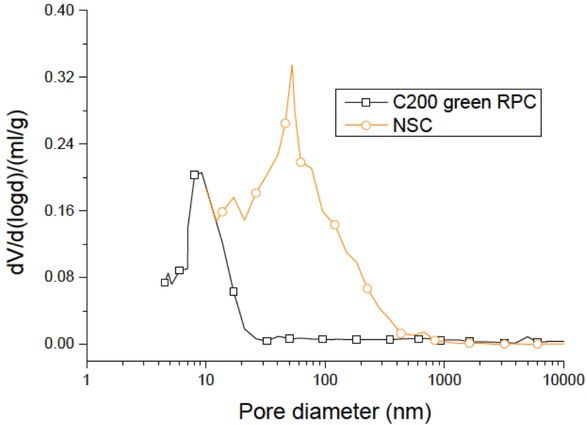

3.4.1 MIP test

The UHPC and NSC specimens were tested by mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) measurement. The pore distribution curves are presented in Figure 8 and the tests data is shown in Table 4. A significant decrease in porosity and average pore diameter was observed in UHPC as compared to the reference NSC concrete. The total porosity and average pore diameter of UHPC obtained is 5.24%and 7.2nm,which is much lower than the reference NSC with the correspondent value of 18.7% and 55.2nm. Therefore, it clearly can be seen from the MIP tests that the UHPC has high dense matrix.

Differential pore size distribution curve

Mercury intrusion porosimetry test results

| Pore size distribution (%) | Average pore sie (nm) | Porosity (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d≤20nm | 20nm≤d≤50nm | 50nm≤d≤200nm | d>200nm | ||

| 75.06 | 5.41 | 4.15 | 15.38 | 7.2 | 5.24 |

| 11.82 | 28.13 | 51.37 | 8.68 | 55.2 | 18.7 |

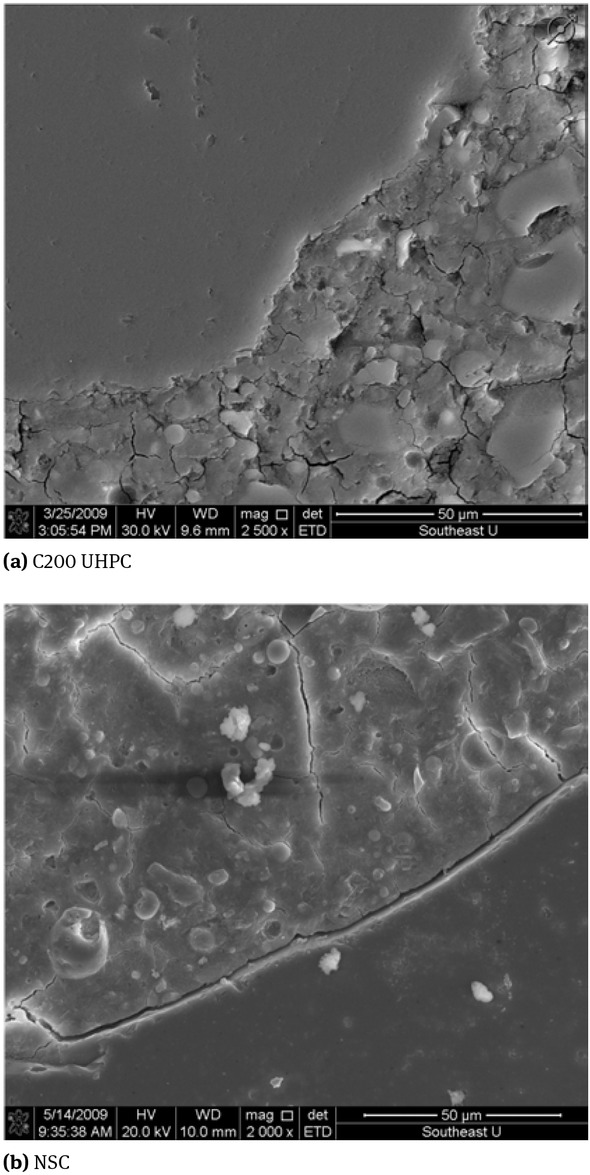

3.4.2 ESEM test

The ITZ of UHPC and normal strength concrete were studied by SEM tests, the picture is shown in Figure 9(a) and Figure 9(b), respectively. In Figure 9(a), the left side of the micrograph shows aggregates and the right presents paste matrix. The situation is reversed in Figure 9(b). It is apparent from Figure 9(a) that the weak ITZ completely vanishes and the bond between the coarse aggregate and UHPC paste is very dense and strong. However, the bond of the coarse aggregate and NSC paste is imperfect, and a gap with several pixels wide can be observed clearly, just as shown in Figure 9(b).

SEM photos of ITZ

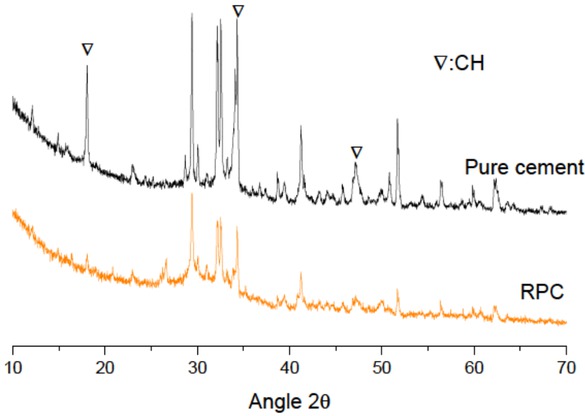

3.4.3 XRD tests

The XRD test were conducted on the specimens of UHPC and NSC. It can be seen that hydration products CH (2θ=18.5, 32.8, 47.5) are formed in the NSC specimen. However, obvious changes were observed in XRD spectrum of UHPC. The intensity of CH peaks is greatly reduced. This indicates pozzolanic reaction between CH and mineral admixtures (fly ash, slag, silica fume) takes place. Large amount of CH is eliminated and much C-S-H gel is formed. This reaction leads to obvious enhancement of the matrix and the ITZ of UHPC.

3.4.4 Mechanism discussion

Based on the micro-tests, the mechanical enhancement mechanism of UHPC are discussed. It is known that concrete is a composite, and its properties depend on the properties of the component phases and the interaction between them. The ITZ of normal strength concrete is a layer up to 50μm wide and characterized by a higher porosity with respect to the bulk cement paste [27]. In an higher contents of CH and ettringite with respect to the bulk cement paste, and much of the CH is considered to be preferentially oriented [28]. Therefore, the interfaces are the weakest link in concrete, playing a very important role in the process of failure.

However, the failure process of UHPC is much different from NSC. The coarse aggregate has much more significant influence on the UHPC mechanical properties than NSC. This phenomenon may be attributed to the following reasons.

Firstly, just as the MIP test results shown in Figure 8 and Table 4, the matrix of the UHPC is very dense and the porosity is low. This because of the use of surperplasticizer, the UHPC can be made with very low water-binder ratio (0.16 in this study) as well as keeping well workability. Besides, the particle size of the mineral admixture is small, which present the micro aggregate effect in the matrix of the paste. The space of the cement particle is highly compacted by the mineral admixture. Therefore, the very low porosity of the matrix leads to high strength of the C200 UHPC.

Secondly, just as the previous discussion, the ITZ are the weakest link in normal strength concrete, playing a very important role in the process of failure. However, the ITZ of the UHPC are extremely enhanced, just as shown in the SEM picture in Figure 9. The ITZ enhancement could be attributed to the pozzolanic action of mineral admixture includes silica fume, fly ash and slag. The main useful effect of the mineral admixture in UHPC consists of pozzolanic effect and micro aggregate effect. The silica fume, fly ash and slag mainly consist Al2O3 and SiO2 can be activated with calcium hydroxide and water to form compound with cementing properties. The two products of cement hydration are calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) and calcium hydroxide (CH). C-S-H is the major contributor to concrete strength. The mineral admixture of silica fume, fly ash and slag contain the amorphous silica (S) which reacts with calcium hydroxide (CH) to form additional C-S-H thereby improving the strength [13, 29, 30]. The XRDtest results in Figure 10 prove that the content of the CH in C200 UHPC is much lower than pure cement. Besides, the micro aggregate effect of mineral admixture also play important role in the ITZ strength as well the matrix discussion as previous. Therefore, the ITZ in UHPC was enhanced extremely. The aggregate and the matrix works together and their potential strength may be fully used.

XRD patterns of UHPC and pure cement

4 Conclusions

Ultra-high performance concrete containing coarse aggregate with compressive strength of 200MPa (C200 UHPC) is successfully prepared in this study by utilizing composite mineral admixtures consisting of 10% silica fume, 20% fly ash and 20% slag to replace 50% of Portland cement, using natural river sand with the maximal diameter of 3mm to totally replace the ultra fine quartz sand, incorporating 3% volume fraction of small sized steel fibers, addition of the crashed basalt stone with maximum size of 10mm as coarse aggregate, and employing low energy consumption curing regime of 20∘C and 100% RH.

The C200 UHPC with coarse aggregate has many advantages over conventional C200 RPC such as the low production cost, less energy consumption, easier preparation, and without any performance loss.

The absorption of the coarse aggregate influence the workability of the fresh C200 UHPC. Besides, the workability decrease with the increasing of the maximum size of coarse aggregate.

The type and maximum size of coarse aggregate has significant effect on the mechanical properties of C200 UHPC. The basalt coarse aggregate with maximum size of 10mm has positive effect on the enhancement of compressive strength. However, the addition of coarse aggregate shows negative effect on flexural strength.

The excellent properties of C200 UHPC are mainly attributed to proper design of the mixture with quaternary cementitious systems containing Portland cement, silica fume, fly ash and slag. The particle packing and filling effect, pozzolanic effect and micro-aggregate effect of the composites mineral admixtures result in a very compacted matrix and dense ITZ between the matrix and aggregate with low porosity and low CH content. The aggregate and the matrix works together and their potential strength may be fully used.

Acknowledgement

This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51678309, 51978339), State Key Laboratory of Silicate Materials for Architectures(Wuhan University of Technology), Priority Academic Program Development Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD). Thanks Dr Su Fan and Dr Yang Jing of advanced analysis and testing center of Nanjing Forestry University for the help of the XRD and SEM tests.

References

[1] Richard P, Cheyrezy M. Composition of reactive powder concretes. Cement Concrete Res. 1995;25(7):1501-11.10.1016/0008-8846(95)00144-2Search in Google Scholar

[2] Zanni H, Cheyrezy M, Maret V, Philippot S, Nieto P. Investigation of hydration and pozzolanic reaction in Reactive Powder Concrete (RPC) using 29Si NMR. Cement Concrete Res. 1996;26(1):93-100.10.1016/0008-8846(95)00197-2Search in Google Scholar

[3] Bonneau O, Lachemi M, Dallaire E, A I Tcin PC, Dugat J. Mechanical properties and durability of two industrial reactive powder concretes. ACI Mater J. 1997;94(4):286-90.10.14359/310Search in Google Scholar

[4] Cwirzen A, Penttala V, Vornanen C. Reactive powder based concretes: Mechanical properties, durability and hybrid use with OPC. Cement Concrete Res. 2008;38(10):1217-26.10.1016/j.cemconres.2008.03.013Search in Google Scholar

[5] Blais PY, Couture M. Precast, prestressed pedestrian bridge-world’s first reactive powder concrete structure. Pci J. 1999; 44(5):60-71.10.15554/pcij.09011999.60.71Search in Google Scholar

[6] Zhang YS, Sun W, Liu SF, Jiao CJ, Lai JZ. Preparation of C200 green reactive powder concrete and its static–dynamic behaviors. Cement Concrete Comp. 2008;30(9):831-38.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2008.06.008Search in Google Scholar

[7] Zhang WH, Zhang YS, Zhang GR. Single and multiple dynamic impacts behaviour of ultra-high performance cementitious composite. Journal of Wuhan University of Technology-Mater Sci Ed. 2011;26(6):1227-34.10.1007/s11595-011-0395-xSearch in Google Scholar

[8] Zhang WH, Zhang YS, Liu LB, Zhang G, Liu Z. Investigation of the influence of curing temperature and silica fume content on setting and hardening process of the blended cement paste by an improved ultrasonic apparatus. Constr Build Mater. 2012;33(1):32-40.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.01.011Search in Google Scholar

[9] Zhang WH, Zhang YS, Zhang GR. Static, dynamic mechanical properties and microstructure characteristics of ultra-high performance cementitious composites. Sci Eng Compos Mater. 2012;19(3):237-45.10.1515/secm-2011-0136Search in Google Scholar

[10] Zhang YS, Zhang WH, She W, Ma L, Zhu W. Ultrasound monitoring of setting and hardening process of ultra-high performance cementitious materials. NDT & E Int. 2012;47(1):177-84.10.1016/j.ndteint.2009.10.006Search in Google Scholar

[11] GB (2016) GB/T 50081-2016: Standard for test method of performance on ordinary fresh concrete. Ministry of Construction of the People’s Republic of China. Beijing. China. (in Chinese).Search in Google Scholar

[12] GB (2002) GB/T 50081-2002: Standard for test methods of physical and mechanical properties of concrete. Ministry of Construction of the People’s Republic of China. Beijing. China. (in Chinese).Search in Google Scholar

[13] Uysal M. The influence of coarse aggregate type on mechanical properties of fly ash additive self-compacting concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2012;37(1):533-40.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.07.085Search in Google Scholar

[14] Khaleel OR, Al-Mishhadani SA, Abdul Razak H. The Effect of Coarse Aggregate on Fresh and Hardened Properties of Self-Compacting Concrete (SCC). Procedia Engineering. 2011;14:805-13.10.1016/j.proeng.2011.07.102Search in Google Scholar

[15] Mehta PK, Monteiro PJ. Concrete: Microstructure, Properties and Materials. 2005. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Wu K, Chen B, Yao W, Zhang D. Effect of coarse aggregate type on mechanical properties of high-performance concrete. Cement Concrete Res. 2001;31(10):1421-25.10.1016/S0008-8846(01)00588-9Search in Google Scholar

[17] Beshr H, Almusallam AA, Maslehuddin M. Effect of coarse aggregate quality on the mechanical properties of high strength concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2003;17(2):97-103.10.1016/S0950-0618(02)00097-1Search in Google Scholar

[18] Aulia TB, Deutschmann K. Effect of mechanical properties of aggregate on the ductility of high performance concrete. Lacer Leipzig. 1999;4(1):133-48.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Szczesniak M, Rougelot T, Burlion N, Shao JF. Compressive strength of cement-based composites: Roles of aggregate diameter and water saturation degree. Cement Concrete Comp. 2013;37(1):249-58.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2012.08.001Search in Google Scholar

[20] Popovices S. Concrete Making Materials. McGraw-Hill Book Company. 1979. New York: Hemisphere Publishing Corporation, Washington DC.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Kaplan MF. Flexural and Compressive Strength of Concrete as Affected by the Properties of Coarse Aggregate. National Building Research Institute. South Africa. 1193-1208.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Zhou FP, Lydon FD, Barr BIG. Effect of coarse aggregate on elastic modulus and compressive strength of high performance concrete. Cement Concrete Res. 1995;25(1):177-86.10.1016/0008-8846(94)00125-ISearch in Google Scholar

[23] Tasdemir C, Tasdemir MA, Lydon FD, Barr BIG. Effects of silica fume and aggregate size on the brittleness of concrete. Cement Concrete Res. 1996;26(1):63-68.10.1016/0008-8846(95)00180-8Search in Google Scholar

[24] Li Q, Deng Z, Fu H. Effect of aggregate type on mechanical behavior of dam concrete. ACI Mater J. 2004;101(6):483-92.10.14359/13487Search in Google Scholar

[25] Chen B, Liu J. Effect of aggregate on the fracture behavior of high strength concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2004;18(8):585-90.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2004.04.013Search in Google Scholar

[26] Chen B, Liu J. Investigation of effects of aggregate size on the fracture behavior of high performance concrete by acoustic emission. Constr Build Mater. 2007;21(8):1696-1701.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2006.05.030Search in Google Scholar

[27] Alonso E, Martıńez L, Martıńez W, Villaseñor L. Mechanical properties of concrete elaborated with igneous aggregates. Cement Concrete Res. 2002;32(2):317-21.10.1016/S0008-8846(01)00655-XSearch in Google Scholar

[28] Diamond S, Huang J. The ITZ in concrete – a different view based on image analysis and SEM observations. Cement Concrete Comp. 2001;23(2-3):179-88.10.1016/S0958-9465(00)00065-2Search in Google Scholar

[29] Hale WM, Freyne SF, Bush TD, Russell BW. Properties of concrete mixtures containing slag cement and fly ash for use in transportation structures. Constr Build Mater. 2008;22(9):1990-2000.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2007.07.004Search in Google Scholar

[30] Radlinski M, Olek J. Investigation into the synergistic effects in ternary cementitious systems containing portland cement, fly ash and silica fume. Cement Concrete Comp. 2012;34(4):451-59.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2011.11.014Search in Google Scholar

© 2020 L. Yujing et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Microstructure and compressive behavior of lamellar Al2O3p/Al composite prepared by freeze-drying and mechanical-pressure infiltration method

- Al3Ti/ADC12 Composite Synthesized by Ultrasonic Chemistry in Situ Reaction

- Microstructure and photocatalytic performance of micro arc oxidation coatings after heat treatment

- The effect of carbon nanotubes on the mechanical and damping properties of macro-defect-free cements

- Toughening Mechanism of the Bone — Enlightenment from the Microstructure of Goat Tibia

- Characterization of PVC/MWCNTs Nanocomposite: Solvent Blend

- Study on Macroscopic and Mesoscopic Mechanical Behavior of CSG based on Inversion of Mesoscopic Material Parameters

- Bearing properties and influence laws of concrete-filled steel tubular arches for underground mining roadway support

- Comparing Test Methods for the Intra-ply Shear Properties of Uncured Prepreg Tapes

- Investigation of Microstructural, Mechanical and Corrosion Properties of AA7010-TiB2 in-situ Metal Matrix Composite

- A Comparative Study of Structural Changes in Conventional and Unconventional Machining and Mechanical Properties Evaluation of Polypropylene Based Self Reinforced Composites

- Research on Influence mechanism of composite interlaminar shear strength under normal stress

- Mechanical properties of geopolymer foam at high temperature

- Synthesis and mechanical properties of nano-Sb2O3/BPS-PP composites

- Multiscale acoustic emission of C/SiC mini-composites and damage identification using pattern recognition

- Modifying mechanical properties of Shanghai clayey soil with construction waste and pulverized lime

- Relationship between Al2O3 Content and Wear Behavior of Al+2% Graphite Matrix Composites

- Static mechanical properties and mechanism of C200 ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC) containing coarse aggregates

- A Parametric Study on the Elliptical hole Effects of Laminate Composite Plates under Thermal Buckling Load

- Morphology and crystallization kinetics of Rubber-modified Nylon 6 Prepared by Anionic In-situ Polymerization

- Effects of Elliptical Hole on the Correlation of Natural Frequency with Buckling Load of Basalt Laminates Composite Plates

- Effect of interphase parameters on elastic modulus prediction for cellulose nanocrystal fiber reinforced polymer composite

- Mixed Matrix Membranes prepared from polysulfone and Linde Type A zeolite

- Fabrication and low-velocity impact response of pyramidal lattice stitched foam sandwich composites

- Design and static testing of wing structure of a composite four-seater electric aircraft

- CSG Elastic Modulus Model Prediction Considering Meso-components and its Effect

- Optimization of spinning parameters of 20/316L bimetal composite tube based on orthogonal test

- Chloride-induced corrosion behavior of reinforced cement mortar with MWCNTs

- Statistical Law and Predictive Analysis of Compressive Strength of Cemented Sand and Gravel

- Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio of the deformable cement adhesives

- Reverse localization on composite laminates using attenuated strain wave

- Impact of reinforcement on shrinkage in the concrete floors of a residential building

- Novel multi-zone self-heated composites tool for out-of-autoclave aerospace components manufacturing

- Effect of notch on static and fatigue properties of T800 fabric reinforced composites

- Electrochemical Discharge Grinding of Metal Matrix Composites Using Shaped Abrasive Tools Formed by Sintered Bronze/diamond

- Fabrication and performance of PNN-PZT piezoelectric ceramics obtained by low-temperature sintering

- The extension of thixotropy of cement paste under vibration: a shear-vibration equivalent theory

- Conventional and unconventional materials used in the production of brake pads – review

- Inverse Analysis of Concrete Meso-constitutive Model Parameters Considering Aggregate Size Effect

- Finite element model of laminate construction element with multi-phase microstructure

- Effect of Cooling Rate and Austenite Deformation on Hardness and Microstructure of 960MPa High Strength Steel

- Study on microcrystalline cellulose/chitosan blend foam gel material

- Investigating the influence of multi-walled carbon nanotubes on the mechanical and damping properties of ultra-high performance concrete

- Preparation and properties of metal textured polypropylene composites with low odor and low VOC

- Calculation Model for the Mixing Amount of Internal Curing Materials in High-strength Concrete based on Modified MULTIMOORA

- Electric degradation in PZT piezoelectric ceramics under a DC bias

- Cushioning energy absorption of regular polygonal paper corrugation tubes under axial drop impact

- Erratum

- Study on Macroscopic and Mesoscopic Mechanical Behavior of CSG based on Inversion of Mesoscopic Material Parameters

- Effect of interphase parameters on elastic modulus prediction for cellulose nanocrystal fiber reinforced polymer composite

- Statistical Law and Predictive Analysis of Compressive Strength of Cemented Sand and Gravel

- Retraction

- Assessment of nano-TiO2 and class F fly ash effects on flexural fracture and microstructure of binary blended concrete

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Microstructure and compressive behavior of lamellar Al2O3p/Al composite prepared by freeze-drying and mechanical-pressure infiltration method

- Al3Ti/ADC12 Composite Synthesized by Ultrasonic Chemistry in Situ Reaction

- Microstructure and photocatalytic performance of micro arc oxidation coatings after heat treatment

- The effect of carbon nanotubes on the mechanical and damping properties of macro-defect-free cements

- Toughening Mechanism of the Bone — Enlightenment from the Microstructure of Goat Tibia

- Characterization of PVC/MWCNTs Nanocomposite: Solvent Blend

- Study on Macroscopic and Mesoscopic Mechanical Behavior of CSG based on Inversion of Mesoscopic Material Parameters

- Bearing properties and influence laws of concrete-filled steel tubular arches for underground mining roadway support

- Comparing Test Methods for the Intra-ply Shear Properties of Uncured Prepreg Tapes

- Investigation of Microstructural, Mechanical and Corrosion Properties of AA7010-TiB2 in-situ Metal Matrix Composite

- A Comparative Study of Structural Changes in Conventional and Unconventional Machining and Mechanical Properties Evaluation of Polypropylene Based Self Reinforced Composites

- Research on Influence mechanism of composite interlaminar shear strength under normal stress

- Mechanical properties of geopolymer foam at high temperature

- Synthesis and mechanical properties of nano-Sb2O3/BPS-PP composites

- Multiscale acoustic emission of C/SiC mini-composites and damage identification using pattern recognition

- Modifying mechanical properties of Shanghai clayey soil with construction waste and pulverized lime

- Relationship between Al2O3 Content and Wear Behavior of Al+2% Graphite Matrix Composites

- Static mechanical properties and mechanism of C200 ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC) containing coarse aggregates

- A Parametric Study on the Elliptical hole Effects of Laminate Composite Plates under Thermal Buckling Load

- Morphology and crystallization kinetics of Rubber-modified Nylon 6 Prepared by Anionic In-situ Polymerization

- Effects of Elliptical Hole on the Correlation of Natural Frequency with Buckling Load of Basalt Laminates Composite Plates

- Effect of interphase parameters on elastic modulus prediction for cellulose nanocrystal fiber reinforced polymer composite

- Mixed Matrix Membranes prepared from polysulfone and Linde Type A zeolite

- Fabrication and low-velocity impact response of pyramidal lattice stitched foam sandwich composites

- Design and static testing of wing structure of a composite four-seater electric aircraft

- CSG Elastic Modulus Model Prediction Considering Meso-components and its Effect

- Optimization of spinning parameters of 20/316L bimetal composite tube based on orthogonal test

- Chloride-induced corrosion behavior of reinforced cement mortar with MWCNTs

- Statistical Law and Predictive Analysis of Compressive Strength of Cemented Sand and Gravel

- Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio of the deformable cement adhesives

- Reverse localization on composite laminates using attenuated strain wave

- Impact of reinforcement on shrinkage in the concrete floors of a residential building

- Novel multi-zone self-heated composites tool for out-of-autoclave aerospace components manufacturing

- Effect of notch on static and fatigue properties of T800 fabric reinforced composites

- Electrochemical Discharge Grinding of Metal Matrix Composites Using Shaped Abrasive Tools Formed by Sintered Bronze/diamond

- Fabrication and performance of PNN-PZT piezoelectric ceramics obtained by low-temperature sintering

- The extension of thixotropy of cement paste under vibration: a shear-vibration equivalent theory

- Conventional and unconventional materials used in the production of brake pads – review

- Inverse Analysis of Concrete Meso-constitutive Model Parameters Considering Aggregate Size Effect

- Finite element model of laminate construction element with multi-phase microstructure

- Effect of Cooling Rate and Austenite Deformation on Hardness and Microstructure of 960MPa High Strength Steel

- Study on microcrystalline cellulose/chitosan blend foam gel material

- Investigating the influence of multi-walled carbon nanotubes on the mechanical and damping properties of ultra-high performance concrete

- Preparation and properties of metal textured polypropylene composites with low odor and low VOC

- Calculation Model for the Mixing Amount of Internal Curing Materials in High-strength Concrete based on Modified MULTIMOORA

- Electric degradation in PZT piezoelectric ceramics under a DC bias

- Cushioning energy absorption of regular polygonal paper corrugation tubes under axial drop impact

- Erratum

- Study on Macroscopic and Mesoscopic Mechanical Behavior of CSG based on Inversion of Mesoscopic Material Parameters

- Effect of interphase parameters on elastic modulus prediction for cellulose nanocrystal fiber reinforced polymer composite

- Statistical Law and Predictive Analysis of Compressive Strength of Cemented Sand and Gravel

- Retraction

- Assessment of nano-TiO2 and class F fly ash effects on flexural fracture and microstructure of binary blended concrete