Abstract

Warm mix asphalt (WMA) is a sustainable innovation in road construction that enables bituminous mixtures to be produced and compacted at lower temperatures than traditional hot mix asphalt (HMA). This reduction in temperature significantly decreases greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and other pollutants, supporting global climate change mitigation efforts. WMA technology enhances energy efficiency while maintaining the performance and durability of road surfaces, offering an environmentally responsible alternative for the construction industry. Its adoption reflects a commitment to reducing the carbon footprint of infrastructure projects. These innovations are anchored in three primary techniques, chemical additives, organic additives, and foaming processes, each of which contributes uniquely to reducing energy consumption while improving pavement performance. Extensive research has revealed the multifaceted advantages of WMA. Mechanically, WMA demonstrates exceptional properties, including enhanced resistance to stripping, fatigue, thermal cracking, and rutting, which collectively contribute to the longevity and resilience of asphalt pavements. Environmentally, the reduced energy demands of WMA production not only reduce emissions but also provide an opportunity to integrate recycled materials and industrial byproducts, further reinforcing its eco-friendly credentials. Economically, the lower production temperatures translate into operational cost savings, although a detailed analysis of long-term cost implications is essential to fully understand its financial viability. This review highlights the historical development, material innovations, and advanced techniques underpinning WMA, providing a thorough evaluation of its rheological and fractured properties. This research aims to support the widespread implementation of WMA in pavement applications. This study also emphasized the critical role of life cycle assessment (LCA) in quantifying the sustainability benefits of WMA mixtures. Moreover, the study explores the emerging trends and challenges in the widespread adoption of WMA, emphasizing the need for robust evaluations of its economic, environmental, and safety aspects. Ultimately, WMA technologies represent a pivotal innovation, offering an integrative solution to modernize the road construction industry while addressing pressing environmental concerns.

1 Introduction

The rapid expansion and modernization of road infrastructure worldwide have posed substantial challenges for the asphalt industry, particularly in terms of resource depletion, environmental sustainability, rising material costs, and the growing need for eco-friendly alternatives. Asphalt pavements serve as a fundamental component of transportation systems, significantly contributing to economic development and daily mobility across nations at varying stages of growth [1]. With increasing traffic volume, there is widespread recognition of the need for enhanced asphalt binders and mixtures that exhibit superior performance characteristics, ensuring the longevity and resilience of road networks [2]. In response to these challenges, the development of ecologically green and energy-efficient pavement technologies has garnered significant attention in recent years [3]. The emergence of WMA technologies can be linked to the global commitment to reducing GHG emissions, which was initially emphasized by the Kyoto Protocol [4]. WMA technologies are commonly categorized into three main classifications on the basis of their approach to lowering production temperatures: foaming techniques, organic modifiers, and chemical additives (Figure 1) [5]. This commitment has been further reinforced through subsequent international climate agreements and initiatives, including the United Nations Climate Summit held in New York in 2014, where world leaders and organizations pledged substantial reductions in carbon emissions [6]. WMAs are produced via specialized techniques and the addition of specific modifiers, allowing them to be manufactured at temperatures between 100 °C and 150 °C, which is considerably lower than the approximately 200 °C required for conventional HMA [7]. This substantial decrease in production temperature results in lower energy demand and a notable reduction in carbon emissions, offering both environmental and economic benefits.

![Figure 1:

WMA technologies (adapted with improvement and permission from [5]).](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0187/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0187_fig_001.jpg)

WMA technologies (adapted with improvement and permission from [5]).

Several comprehensive reviews have recently addressed warm mix asphalt (WMA) technologies, yet their scopes differ from those of the present study (Table 1). These studies concentrated on the environmental emissions and performance of the Evotherm-modified WMA, providing valuable data but limited to a single chemical additive [8]. WMA has been examined primarily from the standpoint of reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) utilization and mix design, without a broad evaluation of other additive classes or sustainability metrics [9]. A detailed review of WMA mix design, performance, and LCA has been presented, but additive-specific effects or barriers to large-scale field implementation [10] have not been analyzed. Design and performance trends are discussed, but an integrative comparison of environmental, mechanical, and economic aspects is lacking [1]. Another study focused solely on foam-mix asphalt, which represents only one subset of WMA technologies [11].

Comparative summary of recent review studies on WMA technologies and the distinct contributions of the present study.

| Ref. | Focus area | Limitations | Distinct contribution of this study |

|---|---|---|---|

| [8] | Emissions and performance of evotherm-based WMA | Limited to one chemical additive | Broader comparison across all additive and process types |

| [9] | RAP utilization and mix design in WMA | Focused on RAP; minimal environmental/economic analysis | Integrates sustainability and life-cycle aspects |

| [10] | Mix design, construction temperature, performance, LCA | Did not discuss additive-specific differences or adoption barriers | Connects LCA findings with implementation challenges |

| [1] | General review on design and performance | Lacked integrated environmental/economic evaluation | Presents multidimensional analysis (mechanical + environmental + economic) |

| [11] | Foam-mix asphalt only | Narrow technological focus | Covers all WMA classifications (chemical, organic, foaming) in one framework |

In contrast, the present review provides a comprehensive synthesis that spans chemical, organic, and foaming WMA technologies (Figure 1), integrating mechanical, rheological, environmental, and economic performance. It further emphasizes LCA and implementation pathways toward large-scale adoption, which have not been systematically discussed in prior works. By combining the classification of WMA technologies with cross-cutting analyses of emissions, energy demand, and sustainability, this paper bridges laboratory findings and field applications, offering actionable insights for researchers and industry practitioners seeking mainstream WMA in modern pavement construction.

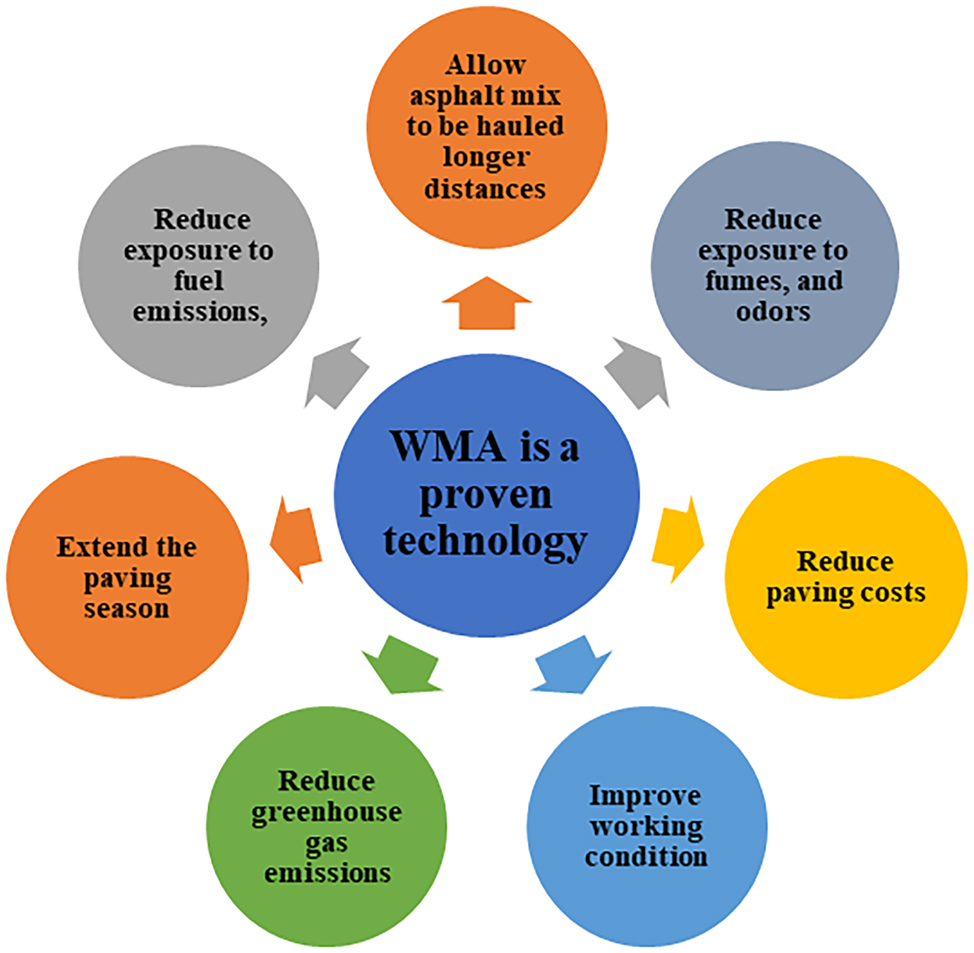

Among the innovative advancements in asphalt production, WMA has gained prominence because of its distinct benefits, including improved workability, lower fuel consumption, reduced GHG emissions, and the ability to facilitate longer transport distances. Under specific conditions, WMA has demonstrated performance that is either comparable to or superior to that of conventional HMA [12]. The extent to which production temperatures can be lowered depends on the specific WMA technology implemented and the type and quantity of additives or processes utilized [13]. Critical insights into the development and optimization of WMA technologies are also provided, offering valuable guidance for researchers in this field [14]. Comparative analyses between WMA and HMA indicate that the integration of WMA additives can lead to energy savings of approximately 5 %–13 %, depending on the degree of temperature reduction achieved during production [15].

Asphalt mixtures are generally categorized on the basis of the temperature required during their production [16]. These classifications consist of four main types, ranked from the highest to the lowest production temperatures: HMA, WMA, half-WMA, and cold mix asphalt [17], 18]. Among these, WMA has garnered significant attention because of its ability to achieve mechanical properties and field performance comparable to those of conventional HMA [19]. The production of HMA involves heating the asphalt binder to elevated temperatures to reduce its viscosity sufficiently, ensuring uniform coating of aggregate particles and strong adhesion [20]. Conversely, WMA employs specialized agents that facilitate adequate adhesiveness at substantially lower temperatures than those required for HMA [14]. These agents fall into three primary technological categories: foaming processes, chemical modifiers, and organic additives [21]. These chemical additives function differently by incorporating a blend of emulsifiers, anti-stripping agents, surfactants, polymers, and performance enhancers [22]. Unlike foaming and organic additives, chemical agents do not directly alter binder viscosity; instead, they improve workability by reducing internal friction between the aggregates and binder, optimizing surface tension, and enhancing adhesion properties [23], 24].

Conventional HMAs are growing concerns over worker health, construction site safety, and environmental sustainability, which have driven significant advancements in asphalt technology. Among these priorities, conserving fossil fuel resources, reducing energy consumption, and minimizing GHG emissions are critical objectives that have spurred the development of WMA technologies [25]. WMA represents a transformative innovation in asphalt materials that is comparable in significance to the introduction of recycling practices. This groundbreaking technology has far-reaching implications for both the asphalt paving industry and environmental stewardship [26]. WMA is a broad term that refers to a range of technologies and additives designed to facilitate the production, placement, and compaction of asphalt mixtures at lower temperatures while maintaining performance and durability standards. By lowering production and application temperatures from 10 °C to 20 °C, WMA offers substantial benefits, including reduced fuel consumption, lower costs, and decreased GHG emissions [1], 27].

WMA technology contributes to minimizing GHG emissions. It also enhances workability, decreases binder aging [28], supports paving in colder weather conditions, and allows for longer haul distances to construction sites [29]. Despite the diverse range of WMA solutions available, all technologies share common goals: lowering binder viscosity, improving workability, and reducing emissions during asphalt mixture production [30]. The rate at which asphalt mixtures cool is primarily determined by the temperature differential between the mixture and its surrounding environment, with a smaller gradient resulting in a slower cooling process [30]. Additionally, RAP, which is derived from the milling or removal of aged and deteriorated pavement during maintenance or rehabilitation, has emerged as a valuable material. The integration of RAP into asphalt mixtures offers substantial economic and environmental benefits, making it a sustainable choice for modern pavement engineering [31]. Figure 2 shows the economic and environmental aspects of WMA mixtures [7].

![Figure 2:

Economic and environmental aspects of WMA products (adapted with permission from [7]).](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0187/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0187_fig_002.jpg)

Economic and environmental aspects of WMA products (adapted with permission from [7]).

However, when used independently, both the RAP and WMA technologies present certain challenges. Combining WMA with RAP has been shown to mitigate these drawbacks, offering a synergistic approach that leverages the strengths of both technologies while addressing their limitations [32]. The economic and environmental advantages of WMA mixtures are illustrated in Figure 2, emphasizing their dual role in advancing sustainability and cost efficiency in asphalt pavement construction [7]. WMA technology offers numerous advantages over conventional HMA, including enhanced workability, reduced fuel consumption [7], lower GHG emissions, and the ability to support longer transport distances. Under similar conditions, WMA has demonstrated performance that matches or even exceeds that of HMA [33]. The extent of temperature reduction achieved varies depending on the specific WMA technology and the amount of additives used. Comprehensive reviews on these technologies are accessible in the literature, offering valuable insights for researchers in the field [34]. By lowering both production and compaction temperatures, WMA technologies yield a variety of benefits, including increased economic efficiency, increased environmental sustainability, improved safety, and superior outcomes in terms of production, paving, and performance [35]. Recent studies have emphasized the economic and ecological advantages of WMA, underscoring its ability to reduce both energy consumption and emissions [36]. Furthermore, the implementation of WMA has been linked to improved working conditions and enhanced safety for construction workers [37]. Reducing production and compaction temperatures is considered the most effective approach for minimizing carbon dioxide emissions during asphalt manufacturing and road construction [34]. In addition, the widespread adoption of WMA is driven primarily by six key benefits: environmental sustainability, improved safety, cost effectiveness, enhanced paving quality, superior performance, and more efficient production processes [38]. Furthermore, Figure 3 displays the chronological distribution of articles on WMAs.

![Figure 3:

Chronological distribution of articles on WMAs (adapted with permission from [39]).](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0187/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0187_fig_003.jpg)

Chronological distribution of articles on WMAs (adapted with permission from [39]).

Although extensive studies have emphasized the environmental, mechanical, and economic advantages of WMA, significant gaps still exist in understanding its long-term performance, especially when it is subjected to diverse climatic conditions and heavy traffic volumes. Moreover, although the use of recycled materials and industrial byproducts in WMA has been investigated, comprehensive studies evaluating their impacts on the rheological and fracture properties of asphalt mixtures are still lacking. This review aims to address these critical gaps by synthesizing and critically examining recent developments in WMA technologies, focusing on material properties, performance metrics, and sustainable applications. Particular attention is given to sustainability indicators, including LCA, to evaluate the environmental and economic implications of WMA. The novelty of this work lies in its integrative approach, which combines technical, mechanical, and economic analyses to generate actionable insights that bridge the gap between academic research and practical implementation. By identifying emerging trends, unresolved challenges, and opportunities for widespread adoption, this review aims to provide valuable resources for researchers, industry stakeholders, and policymakers committed to advancing sustainable road construction practices. The interdisciplinary nature and comprehensive scope of this study underscore its importance as a timely contribution, offering innovative, solution-driven perspectives to support the ongoing evolution of the road construction sector. The work is designed to resonate with both academic reviewers and practitioners seeking impactful, forward-thinking research in this critical area.

2 Structure and evidence-gathering protocol adopted for the collection of literature reviews

This review started searching major scholarly databases (Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, ASCE Library, IEEE Xplore, SpringerLink) and reputable industry and agency sources such as AASHTO/ASTM) for publications from 2000 to 2025, giving extra weight to 2015–2025, when warm mix asphalt (WMA) technologies matured and field use expanded. The search terms combined WMA types (chemical, organic, and foaming, including proprietary names) with outcomes of interest, such as materials and production/compaction practices; laboratory and field properties (rheology, fracture/fatigue, rutting, moisture damage); sustainability and LCA; costs and energy use; safety and performance; practical applications; and adoption barriers and trends. Studies that tested or applied WMA via any of the three main approaches and reported at least one relevant outcome (mechanical/rheological or field performance, environmental indicators such as emissions/energy or LCA, or economic/implementation evidence) were also included. We excluded HMA-only or cold-mix papers without WMA analysis, patents without evaluative data, editorials/news items, and records without accessible full texts. A standardized extraction form captured the WMA class and additive dosage, production and compaction temperatures, binder grade and RAP content, test standards (AASHTO/ASTM), mechanical and durability metrics, environmental indicators (e.g., GHG emissions, energy intensity, LCA scope and assumptions), economic and implementation notes, safety observations, and deployment details. Because studies vary in materials, dosages, boundary conditions, and test methods, they synthesize results narratively and use simple direction-of-effect summaries where fair comparisons exist; a meta-analysis was not performed owing to methodological incompatibilities. Full search strings, screening decisions, and appraisal/extraction templates are archived to ensure transparency and reproducibility. Furthermore, it is believed that this paper can offer a methodologically transparent, practical reference for researchers, practitioners, and transportation-infrastructure designers worldwide.

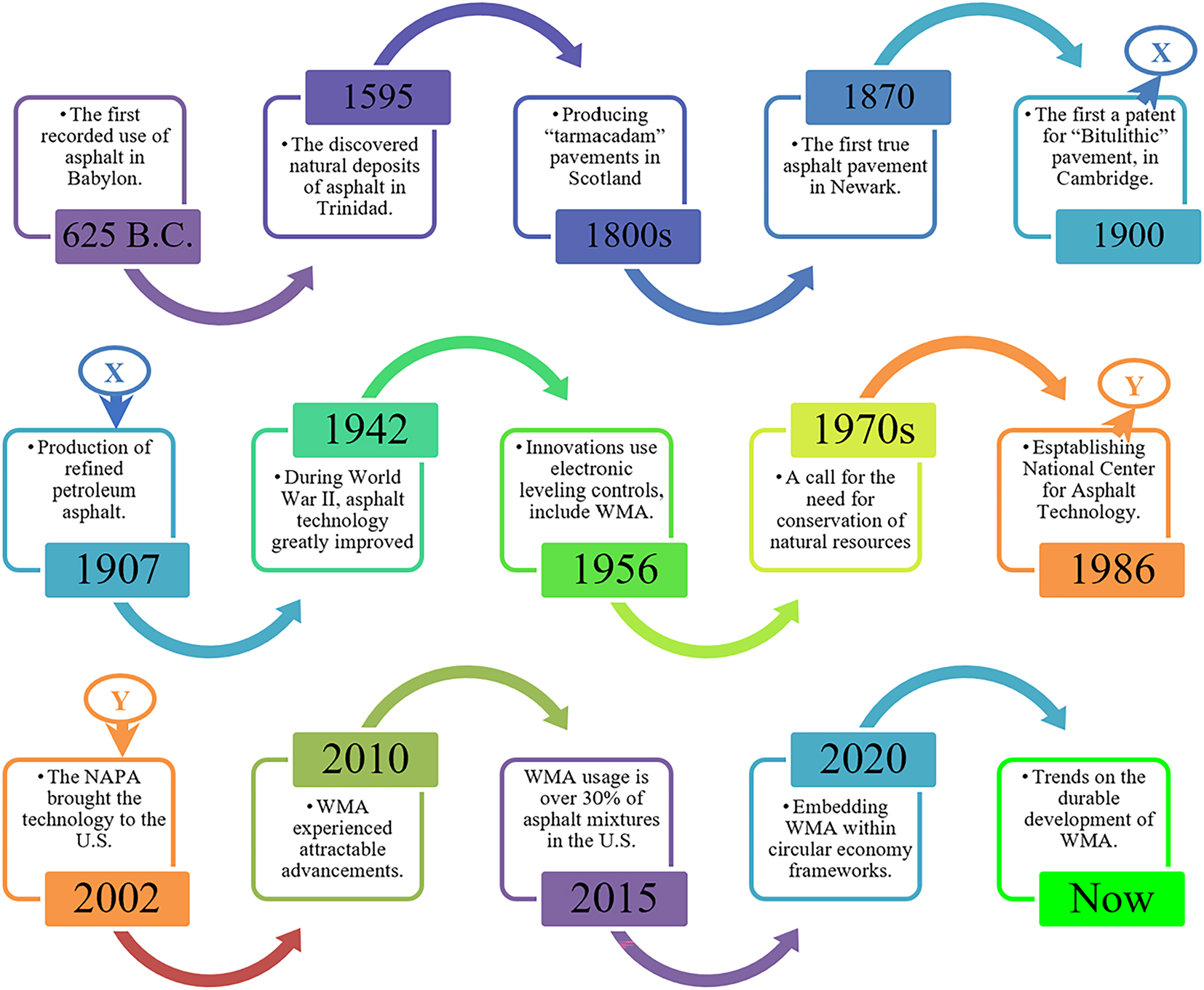

3 Historical development

The first Asphalt was initially used for road building in Babylon. The ancient Greeks, who called it “asphaltos” meaning “secure”, returned to 625 B.C. (Figure 4). Moreover, the development of WMA technology can be traced back to Europe, although the initial concept was pioneered in 1956 by Professor Csanyi at Iowa State University [40]. The first documented WMA trials were conducted in Norway and Germany between 1995 and 1999 [41]. In 1996, regulatory authorities in Germany, specifically the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, introduced new workplace safety standards aimed at reducing exposure to asphalt fumes by decreasing the temperatures of asphalt mixtures [42]. The earliest significant experimentation with WMA technology occurred in 1995, when a German company conducted tests using Aspha-min zeolite to induce foaming in asphalt mixtures.

Historical development trends of WMA.

Concurrently, Norwegian researchers in 1996 experimented with a WAM emulsion, a precursor to WAM foam, which became one of the earliest forms of foaming technology [42]. In 1997, the introduction of wax-modified WMA in Hamburg marked a pivotal development in refining WMA formulations [43]. This innovation was followed by significant progress in 1999, with the first field trials of WMA using foam asphalt (Table 2) and Aspha-min zeolite conducted in Norway and Germany, respectively. The global adoption of WMA grew rapidly during the early 2000s, with the National Asphalt Pavement Association (NAPA) bringing the technology to the United States in 2002 [34] (Figure 4). In the same year, the FHWA, in collaboration with several State Departments of Transportation, initiated WMA trials across the U.S. The incorporation of foaming methods such as WAM-Foam™ from Norway, along with chemical additives such as Evotherm in the U.S., played a crucial role in broadening the range of WMA applications. By 2003, the NCHRP launched comprehensive studies to assess the performance and environmental advantages of WMA, which significantly propelled its widespread adoption in the U.S. market.

Effects of foam asphalt on various properties, as reported by previous researchers.

| Asphalt type | Temperature sensitivity | Low temperature performance | Fatigue resistance | High temperature performance | Rutting resistance | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBS modified bitumen | Increased | Unsignificant change | Increased | Increased | Increased | [44] |

| Latex modified asphalt | Unsignificant change | – | – | – | Unsignificant change | [45] |

| PG70-22, PG64-22 | – | – | – | Increased | – | [46] |

| A 50/70 and 35/50 | Increased | Increased | Unsignificant change | Decreased | – | [47] |

| Epoxy asphalt | Increased | – | – | Decreased | Decreased | [48] |

| 70/100 bitumen | Unsignificant change | Unsignificant change | – | Decreased | Decreased | [49] |

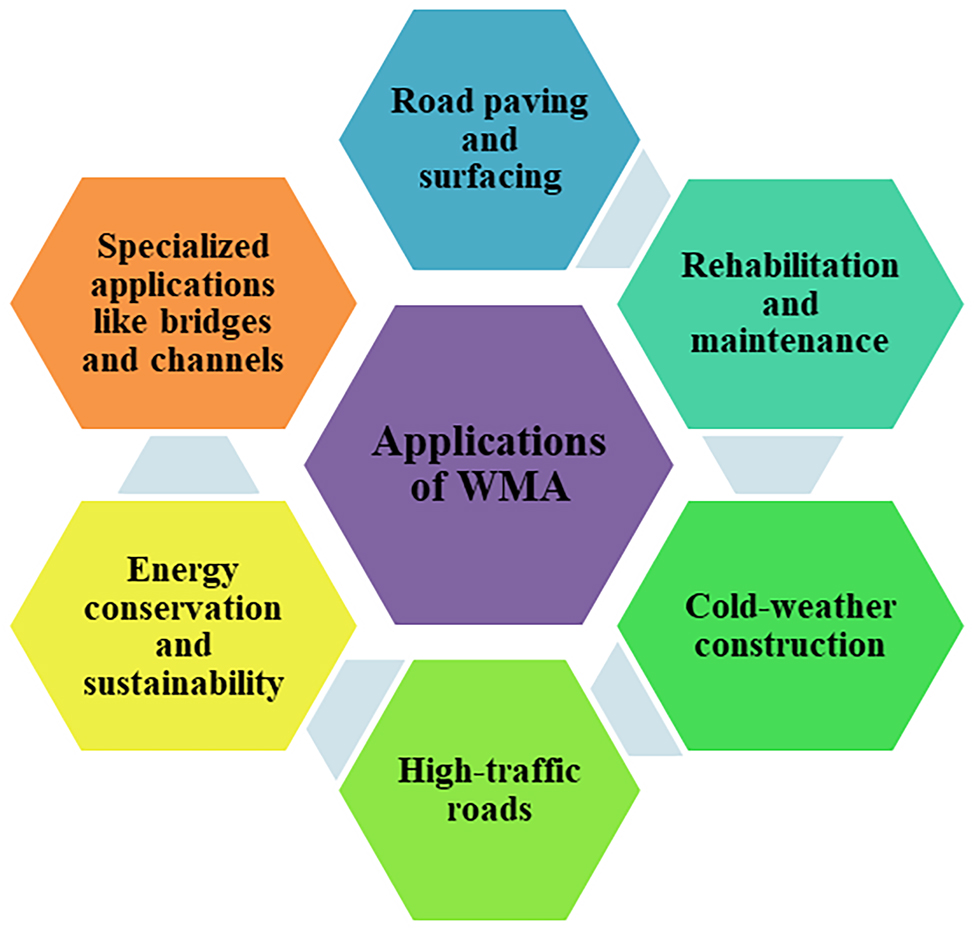

In the early 2000s, amid growing concerns over climate change and tightening environmental regulations, advancements in WMA technologies were directed toward reducing carbon dioxide emissions and energy consumption (Saarinen et al. 2015). This has led to extensive research and innovation, resulting in further enhancements to WMA production methods [50]. By 2010, WMA had gained widespread acceptance as a sustainable alternative to conventional HMA. The introduction of advanced foaming techniques, such as the Double Barrel Green process, significantly improved the temperature reduction efficiency and asphalt mix production. Moreover, comprehensive studies confirmed that WMA maintained or enhanced pavement durability, reduced fuel usage during manufacturing, and minimized worker exposure to hazardous emissions, thereby reinforcing its technological advantages (Figure 6).

From 2010 onward, WMA technologies experienced attractable advancements and widespread adoption, driven by intensified research, technological improvements, and a growing global focus on sustainability [51] (Figure 4). The formalization of WMA specifications by AASHTO marked a pivotal step in standardizing its use across the United States [52]. By this time, state transportation agencies had widely integrated WMA into their infrastructure projects, with the NAPA reporting that WMA accounted for nearly 10 % of total asphalt production in the U.S. [53].

Between 2010 and 2015, the industry saw continuous refinement of WMA methodologies, particularly in foaming systems and chemical additives [54]. Innovations such as the Double Barrel Green system have gained popularity for producing high-quality mixes at significantly reduced temperatures. Concurrently, research has highlighted the compatibility of WMA with higher proportions of recycled materials, such as RAP [55]. By 2015, WMA usage in the U.S. had increased, representing more than 30 % of asphalt mixtures, reflecting confidence in its performance, economic viability, and environmental benefits [52].

From 2016 to 2020, advancements in WMA technology emphasized improving mix durability and broadening its applicability across various climatic conditions [13], 18]. Countries such as India and China accelerated their adoption of WMA through government-led sustainability programs and the development of region-specific technologies. In the United States, federal and state agencies increasingly promoted WMA for high-traffic roads and urban environments to curb energy consumption and mitigate urban heat island effects [34]. Research during this period also explored the integration of WMA with emerging innovations, including biobased additives, nanomaterials, and enhanced reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) utilization [30]. Since 2020, the focus has shifted toward embedding WMA within circular economy frameworks, prioritizing lifecycle sustainability [56]. With global commitments to reduce GHG emissions under agreements such as the Paris Accord, WMA has evolved into a key element of green infrastructure strategies [5]. Innovations include carbon-neutral or carbon-negative additives and the use of smart monitoring systems to assess mix performance during and after construction [57]. Furthermore, WMA is increasingly combined with other sustainable practices, such as cold in-place recycling and low-carbon binders. Presently, WMA accounts for nearly half of the asphalt production in leading markets such as the U.S., signifying its transformation from an emerging technology to a mainstream industry standard.

4 Classification of asphalt mixture technologies

Asphalt mixtures, which are essential for the construction and maintenance of roadways and parking lots, are composed of aggregates, asphalt binder, and filler materials [34]. The aggregate components may include crushed rock, sand, gravel, or industrial byproducts such as slag. Typically, asphalt cement serves as the binding agent, and when combined with heated aggregates, it forms what is commonly known as HMA or conventional asphalt mixtures [58]. The performance characteristics of asphalt mixtures are significantly influenced by temperature variations. Elevated temperatures lead to a considerable reduction in the viscosity of the binder, thereby weakening the adhesive bond between aggregate particles [59]. Simultaneously, the mixture’s stiffness decreases, resulting in increased susceptibility to permanent deformation under repetitive loading conditions [60]. To address these challenges, extensive research efforts have been directed toward developing innovative technologies that allow asphalt mixture production at lower temperatures without altering the mechanical integrity of the mixture.

Several asphalt production technologies, including HMA, WMA, and CMA, have been introduced to improve energy efficiency and environmental sustainability [61]. HMA serves as the conventional benchmark and is produced at high temperatures (typically 150–180 °C) to ensure proper aggregate coating and mixture workability. In contrast, CMA and WMA represent innovations that enable the production and compaction of asphalt at lower temperatures, thereby reducing fuel consumption and emissions. Despite these advantages, both CMA and certain WMA formulations exhibit performance limitations [30]. CMA faces challenges such as inadequate aggregate coating, increased air-void content, and extended curing periods. HMA, on the other hand, while providing excellent mechanical performance, suffers from increased energy demand, increased emissions, and worker safety concerns due to elevated production temperatures [62]. WMA technology offers a balanced alternative by lowering production temperatures while maintaining satisfactory engineering performance [63]. The adoption of WMA presents multiple advantages, including enhanced workability, minimized emissions, reduced fuel consumption, improved occupational safety, and an extended paving season [12]. Despite these benefits, the rigorous assessment and widespread implementation of WMA in pavement construction remain limited [56]. Figure 5 contrasts HMA and WMA technologies across key production and sustainability metrics. HMA operates at relatively high production temperatures (150–180 °C), does not require additives, and is associated with high energy consumption, greenhouse gas emissions (e.g., CO2), and overall cost. By comparison, WMA lowers the production temperature to 110–140 °C using additives, which correspondingly reduces the energy demand, emissions, and cost. Collectively, the diagram underscores WMA’s operational and environmental advantages relative to HMA, notwithstanding the requirement for chemical or foaming additives (Milad et al. 2022).

![Figure 5:

Comparison of WMA and HMA mixture technology (adapted with permission from [64]).](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0187/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0187_fig_005.jpg)

Comparison of WMA and HMA mixture technology (adapted with permission from [64]).

Beneficial-technological characteristics of WMA.

In WMA mixtures, temperature reduction during production is achieved through three primary methods [65]. This includes the foaming process, which mainly introduces water into the asphalt binder, either directly via specialized nozzles or indirectly through water-laden materials such as zeolites [66]. Studies indicate that the addition of water temporarily increases the binder’s volume, lowering its viscosity and allowing for more effective and consistent aggregate coatings, thereby improving the workability [34]. Common foaming techniques include water-based zeolites and water-infused methods such as WAM foam [39]. Organic additives, such as waxes and fatty amides, also contribute to lowering production temperatures by decreasing the viscosity of the asphalt binder. These additives typically melt at temperatures between 80 and 120 °C, facilitating better mixing and compaction during production [27], 30]. As these substances cool below their melting point, they crystallize and form a structural network, which can significantly improve the rheological and mechanical characteristics of the asphalt binder. Organic-based WMA technologies, such as Sasobit, are examples of additives that utilize this crystallization process to enhance binder performance [67].

Chemical additives, primarily composed of surfactants, emulsifiers, polymers, or a combination of these compounds, operate through a mechanism that differs significantly from foaming and organic-based methodologies [56]. These agents contribute to lowering the internal slip resistance, thereby minimizing the surface tension between the asphalt binder and aggregate particles [68]. By reducing surface tension, these additives enhance the coating efficiency of aggregates even at lower production temperatures [13]. A key advantage of chemical WMA technologies is that they do not substantially modify the viscosity or rheological characteristics of the asphalt binder [69]. Some of the most commonly utilized chemical additives in asphalt production include Zycotherm, Rediset, Cecabase, and Evotherm, all of which have been extensively studied and validated for their effectiveness [34]. Further detailed discussions regarding these technologies can be found in the literature [70].

A substantial body of research has investigated the impact of mixing and compaction temperatures on the mechanical properties of asphalt mixtures. When the mixing temperature falls below the required threshold, the binder may fail to adequately coat the aggregate, leading to an increased risk of moisture-induced damage [71]. Conversely, if compaction temperatures are excessively reduced, the densification process of the asphalt mixture in the field may be compromised, resulting in insufficient in-place density [72]. Moreover, excessively high temperatures during asphalt production and placement pose additional performance concerns [73]. Overheating accelerates the aging process of the asphalt binder, promoting oxidative hardening, which in turn facilitates the development of premature pavement cracks [74]. Studies estimate that inadequate compaction accounts for nearly 80 % of early pavement failures [63]. To address these challenges, researchers have explored various methods to determine the optimal mixing and compaction temperatures for asphalt mixtures [75]. While standardized guidelines exist for establishing the production temperatures of HMA, there remains no universally accepted criterion for defining the optimal mixing and compaction temperatures of WMA. Moreover, Figure 5 shows different WMA mixtures containing varying amounts of RAP [1], 23], 39], 57], [76], [77], [78]. However, the beneficial-technological characteristics of the WMA are shown in Figure 6.

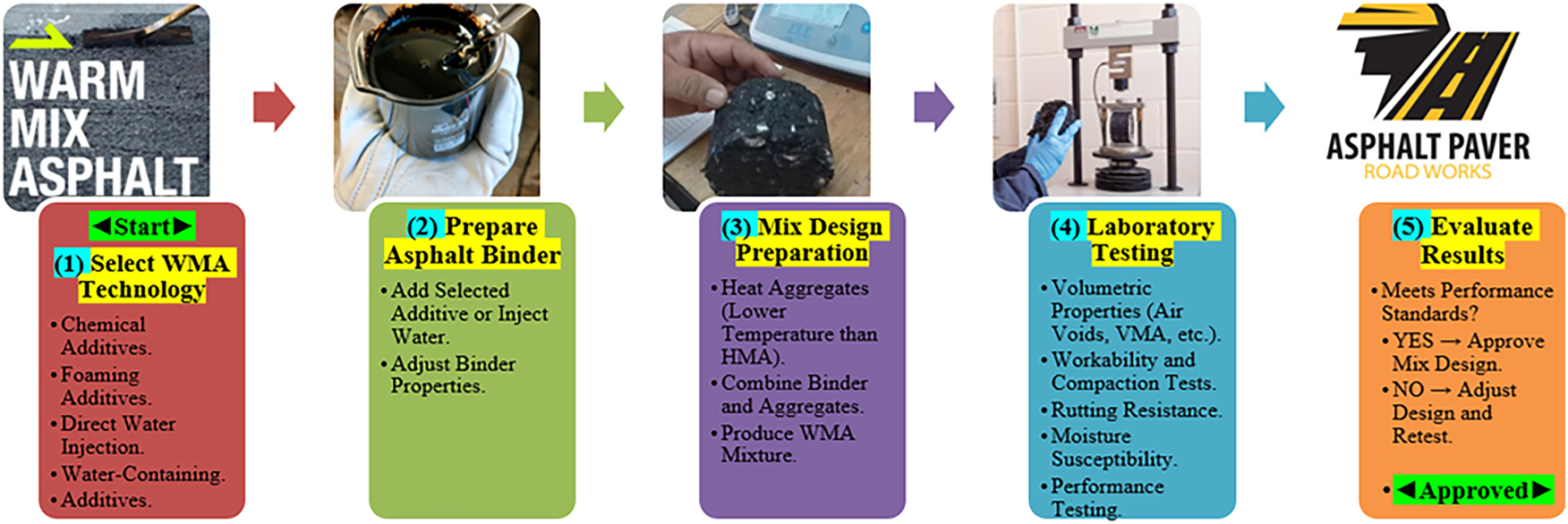

5 Materials in WMA production

WMA has emerged as a groundbreaking and eco-friendly alternative in road construction, delivering significant environmental and economic advantages over conventional HMA [34]. The technical processes employed in WMA design are essential for decreasing both energy consumption and emissions efficiently (Figure 7). The production of WMA utilizes various materials and techniques, each contributing to its overall performance and sustainability [18]. A particularly noteworthy approach is the incorporation of waste materials such as steel slag, which not only helps conserve natural resources but also improves the mechanical properties of asphalt mixtures. Research has shown that the inclusion of steel slag enhances the stiffness and moisture resistance of asphalt, making it a potential solution for increasing the long-term durability of pavements [79].

WMA design technical processes.

Moreover, the additives of organic agents, chemical modifiers, and synthetic zeolites have been demonstrated to increase the environmental benefits of WMA by further lowering the energy requirements for asphalt production. However, findings from LCAs suggest that certain additives may counteract these benefits because of their own environmental footprint, underscoring the importance of selecting additives with sustainability in mind [80]. In addition, the incorporation of recycled materials, such as RAP and industrial byproducts such as zeolite derived from petroleum refining, has proven highly effective in reducing the reliance on virgin aggregates, thereby minimizing the environmental impact of WMA. The synergy between WMA additives and recycled materials not only promotes sustainable resource utilization but also ensures that the mechanical performance and durability of asphalt mixtures remain comparable to or surpass those of conventional HMA [81]. In some instances, the use of WMA with up to 50 % reclaimed asphalt has been found to significantly reduce GHG emissions and overall energy consumption while maintaining superior pavement performance characteristics [82]. Figure 8 shows the influence of the volume of binder used on the rutting temperature of different WMA mixtures, as reported in previous studies [34], 39], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91]. Previous studies related binder volume (left axis, blue) with rutting test temperature (right axis, red) across multiple standard methods (e.g., AASHTO TP 63/T324, EN 12697–22, BS 598–110). The rutting temperatures generally cluster between ∼50 and 65 °C, whereas the average binder volumes span ∼35–65 %, with modest variability indicated by small error bars. Methods reporting higher binder contents (notably EN 12697–22 and AASHTO T324/TP63 in several datasets) also tend to report the upper range of rutting temperatures, implying a positive association between binder content and the temperature regime used to assess rutting susceptibility. Conversely, protocols with lower binder contents (e.g., some AASHTO T63 instances) align with lower rutting temperatures, highlighting that both the mixture composition and the chosen test standard systematically influence the reported rutting behavior of WMA mixtures. Despite the evident advantages of WMA, challenges remain in achieving an optimal balance between the use of additives and their environmental impact. Some additives, while effective at reducing production temperatures, may introduce sustainability concerns that offset their benefits. Furthermore, advancements in WMA technology have led to the development of recycled synthetic fibers and foamed bitumen, which continue to enhance road performance and environmental sustainability at reduced temperatures [92].

A significant body of research has been devoted to assessing the low-temperature performance of WMA containing RAP. One study, which utilized bending beam rheometer tests and asphalt binder cracking devices, explored the effects of Sasobit-modified WMA combined with RAP. The findings indicated that an excessive amount of WMA could compromise the mixture’s resistance to low-temperature cracking [93]. In addition, increasing the RAP content was found to negatively impact the ability of a mixture to resist cracking at low temperatures [94]. However, the use of rejuvenating agents has been identified as an effective method to mitigate the brittleness observed in WMA-RAP blends, significantly enhancing their low-temperature performance [95]. Given the natural stiffness of WMA-RAP mixtures, concerns have arisen about the potential for early cracking in colder climates, with several studies noting a decline in low-temperature performance compared with that of control mixtures [96]. On the other hand, some research suggests that, under specific conditions, WMA-RAP mixtures can perform just as well or even outperform traditional mixtures at cold temperatures [97]. Further investigations into foam WMA with varying levels of RAP binder have confirmed that the binder content in RAP plays a crucial role in determining the low-temperature behavior of recycled asphalt [5]. While WMA mixtures without RAP typically exhibit better flexibility at lower temperatures, the inclusion of RAP increases the mixture’s stiffness and reduces the m value, which could negatively affect its performance in colder environments [36]. Continuous advancements in material science and engineering remain essential for optimizing WMA formulations, ensuring that their environmental advantages align with long-term durability and resilience under diverse climatic conditions.

6 Advanced techniques in WMA compaction

WMA technology, which was originally developed in Europe, has revolutionized asphalt production by addressing key industry challenges. Compared with conventional HMA, this innovation significantly reduces production and compaction temperatures, leading to substantial decreases in energy consumption and emissions [27]. The ability to produce asphalt at lower temperatures not only reduces GHG emissions but also enhances the mixture’s workability, minimizes binder aging [28], facilitates paving in colder climates, and extends the feasible transport distance between mixing facilities and construction sites [21]. The cooling behavior of asphalt mixtures is largely dictated by the temperature differential between the mixture and the surrounding environment, with smaller differentials leading to slower cooling rates. This allows for extended compaction time and improved placement quality [1], 30], 98]. The integration of RAP into new asphalt mixtures offers significant economic and environmental advantages by reducing the reliance on virgin materials and increasing sustainability [99]. However, both the RAP and WMA individually pose certain limitations. Their combined application has proven to be an effective approach for mitigating these challenges, thereby improving the overall performance of the asphalt mixture and increasing pavement longevity [32].

The widespread adoption of WMA technologies in the asphalt industry is largely attributed to their capacity to increase mixture workability while lowering production and compaction temperatures. Among the most effective and commonly utilized WMA methods are (1) organic additives, such as Sasobit, which function by reducing the viscosity of the asphalt binder upon reaching its melting point. This ensures sufficient fluidity throughout production and construction, even at reduced temperatures [18]. (2) Chemical additives, such as evotherms, improve binder‒aggregate adhesion at lower temperatures by modifying interfacial properties, reducing slip forces at the binder‒aggregate interface, and consequently enhancing particle mobility during compaction. This results in improved uniformity and overall compaction performance [100]; and (3) foaming techniques, such as water-based foaming, in which controlled amounts of water are introduced into the asphalt binder during production [101]. The injected water generates steam and forms microbubbles within the binder, leading to expansion and viscosity reduction, thereby enhancing the binder’s ability to coat aggregates effectively at lower temperatures [102]. The integration of WMA technologies has significantly reshaped the asphalt industry, offering a wide range of benefits. One of the primary advantages is the reduction in mixing and compaction temperatures, which prevents premature aging of the asphalt binder. This, in turn, prolongs the material’s service life and improves its resistance to fatigue and thermal cracking during the early service stages [13]. Figure 9 depicts the influence of the volume of binder used on the air voids of different WMA mixtures, as reported in previous studies [34], 39], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91]. Moreover, as WMA mixtures do not require high-temperature storage, transportation, or placement conditions, they provide greater flexibility in field applications, increasing their practicality and sustainability. Prior studies related the binder volume (blue; left axis) to the measured air-void content (red; right axis) in WMA mixtures across several rutting test standards (e.g., BS 598–110, AASHTO TP 63/T324, EN 12697–22). Air voids mostly fall within a narrow 4–7% band, whereas the corresponding average binder volumes span approximately 40–65 %, with modest dispersion indicated by small error bars. A weak inverse tendency is observable: cases employing higher binder contents (60–65 %) often report air voids toward the lower end of the range, whereas lower binder contents (0–50 %) coincide with greater voids. These patterns suggest that increasing the binder volume can marginally improve compactability and mixture densification, although standard-specific procedures also contribute to the observed variability.

The extended paving window facilitated by WMA technologies enables longer paving seasons, granting contractors logistical advantages [42]. Furthermore, WMA mixtures have exhibited improved workability and reduced compaction efforts, even when up to 90 % RAP is incorporated, reinforcing their viability for sustainable asphalt production [103]. Moreover, Figure 10 illustrates the impact of the binder volume on the air void content in various WMA mixtures [34], 39], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91]. It has also been reported that WMA formulations pair different additives with RAP, showing the RAP content (blue; left axis) alongside the dosage of other materials/additives (red; right axis). Across additives such as zeolites/Advera, Sasobit, Kaowax, PAWMA, Zycotherm, and Evotherm, RAP incorporation spans approximately 20–70 %, with zeolitic and wax-based systems (e.g., Sasobit) frequently enabling higher RAP fractions. Additive dosages are comparatively small (generally a few percent by mass), with zeolites typically used at the upper end of this range and amine/surfactant-type agents (e.g., Zycotherm, Evotherm) at the lower end. Collectively, the chart indicates that substantial RAP contents are feasible in WMA, but the achievable level is additive-dependent and reflects trade-offs among workability, foaming efficacy, and mixture performance.

The evaluation of asphalt mixture workability is typically conducted via three primary techniques, each offering unique benefits and limitations. The first method involves measuring the viscosity of the asphalt binder [63], which has traditionally been used for conventional asphalt binders and viscosity-dependent technologies [14]. However, this approach may not accurately reflect the improvements in workability achieved by certain WMA technologies, such as foaming processes and chemical additives, which have minimal effects on binder viscosity. Consequently, this technique may lead to inaccurate estimations of the required mixing and compaction temperatures, potentially overestimating the actual improvements in workability [13]. A second approach uses specialized instruments, such as a workability meter, to measure torque and resistance during the mixing process [63]. This method is effective in quantifying the resistance encountered while mixing and is highly sensitive to factors such as the binder content, binder stiffness, and aggregate composition, such as RAPs. However, it does not fully account for the impact of chemical additives on binder‒aggregate adhesion. In addition, the results obtained during mixing may not always correlate with the mixture’s performance in terms of ease of placement and compaction during field operations. The third technique assesses mechanical responses during compaction via the Superpave gyratory compactor (SGC) [104]. The SGC provides valuable insights by monitoring volumetric properties under controlled compaction energy and measuring shear resistance during the compaction process. This method is particularly useful for evaluating the workability by simulating real-world compaction conditions.

Advancements in sensing technology have provided deeper insights into the influence of mixture particle kinematics on asphalt compaction [105], 106]. The application of microelectromechanical system devices, such as the SmartRock sensor, has enabled researchers to examine particle-level responses under both laboratory and field conditions [107]. The findings consistently demonstrated a correlation between particle rotation, density development, and compaction behavior during SGC testing. When comparing kinematic parameters, such as particle rotation and acceleration, between the laboratory and field compaction processes, it is evident that the kneading action of the SGC, along with rolling wheel compaction, effectively mimics the actions of pneumatic-tire rollers used in the field. In a similar vein, the vibratory effects generated by the Marshall hammer were found to be comparable to those of field vibratory rollers [108]. Further laboratory experiments utilizing SmartRock sensors have shown that the particle contact stress is a reliable indicator of compaction conditions. Furthermore, variations in stress rates serve as a quantitative measure for evaluating the workability of asphalt mixtures [109]. The combined application of experimental and numerical approaches in assessing asphalt mixture compaction has demonstrated a significant relationship between the particle contact stress and the mixture’s locking point. This relationship underscores the viability of the particle contact stress as a practical measure of compactability [110]. These insights emphasize the significant role of particle kinematics and the mechanical properties of the mixture in influencing both the compactability and overall workability of asphalt mixtures [104]. Investigating the relationship between particle behavior during compaction and mixture workability provides essential knowledge for optimizing WMA technologies. Figure 11 shows the performance of the RAP, WMA and RAP + WMA mixtures [5]. Understanding these interactions enables the selection of materials with improved workability characteristics tailored to specific construction requirements.

![Figure 11:

Performance of WMA, RAP and WMA + RAP mixes (adapted with permission from [5]).](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0187/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0187_fig_011.jpg)

Performance of WMA, RAP and WMA + RAP mixes (adapted with permission from [5]).

7 Rheological properties

WMA can be produced through various techniques that utilize chemical and organic additives, including water-based agents and water-containing processes [30]. Extensive research worldwide has focused on refining WMA applications in pavement engineering to improve performance and sustainability [111]. Selecting the appropriate WMA technology and determining its optimal dosage are crucial for enhancing the rheological properties of asphalt binders, as well as improving the mechanical strength and longevity of asphalt mixtures. To compare the efficiency of different WMA additives, researchers have developed three dimensionless parameters that quantify variations in viscosity, resistance to rutting, and fatigue performance [39]. These parameters were normalized with respect to the base (unmodified) binder to allow direct comparison across additive types and dosages. The parameters are defined in Eqns. (1)–(3) as follows:

Rheological Enhancement Index (REI)

Viscosity Reduction Index (VRI)

Fatigue Performance Ratio (FPR)

where G * is the complex modulus from the DSR test, η is the dynamic viscosity, and G f is the fracture energy from SCB or LAS testing. All values were averaged across replicate measurements and scaled to the interval [0–1] via min–max normalization. Positive REI and FPR values indicate improvements in stiffness and fracture resistance, whereas a positive VRI denotes viscosity reduction and better workability.

As summarized in Table 3, representative WMA additives demonstrate distinct rheological and fracture behaviors when normalized to a control HMA binder. This normalized approach provides a structured way to compare additive performance. Chemical additives such as Evotherm and Rediset show greater viscosity-reduction potential (VRI > 0.35), whereas organic modifiers such as Sasobit achieve greater improvement in stiffness (REI ≈ 0.22). These indices should be interpreted as relative indicators because factors such as binder grade, temperature, and aging can influence the absolute values.

Dimensionless rheological and fracture parameters for representative WMA additives (values normalized to control HMA binder).

| Additive | Type | Dosage (% binder) | REI | VRI | FPR | Reference sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sasobit | Organic (wax) | 1.5 | 0.22 | 0.31 | 0.94 | [112] |

| Evotherm | Chemical (amine surfactant) | 0.4 | 0.18 | 0.42 | 0.98 | [113] |

| Rediset WMX | Chemical | 0.5 | 0.15 | 0.37 | 0.91 | [114] |

| Cecabase RT | Chemical (surfactant–ester blend) | 0.3 | 0.20 | 0.33 | 0.95 | [115]v” |

The impact of WMA additives largely depends on their chemical structure and functional mechanisms. Organic additives, such as wax-based compounds, decrease the binder viscosity once the temperature exceeds the melting point. On the other hand, chemical additives improve binder workability by reducing surface tension without significantly altering rheological characteristics [116]. However, the influence of WMA additives on moisture resistance varies depending on the type of technology used. Water-containing additives, including Aspha-min and Advera, as well as organic additives such as Asphaltan-B and Sasobit, have been reported to lower the moisture resistance of WMA mixtures, increasing their susceptibility to moisture-induced damage [50]. Conversely, chemical additives such as Rediset promote better adhesion between the binder and aggregates, enhancing moisture resistance while minimizing changes in the rheological behavior of the binder [117]. Therefore, the selection of WMA additives must be carefully considered to maintain a balance between workability and moisture resistance.

Owing to their unique molecular properties, surfactants enhance binder‒aggregate adhesion by attracting aggregates with opposite charges [117]. The influence of WMA additives on asphalt binder properties has also been examined via spectroscopic techniques. For example, as shown in Figure 12a, the incorporation of the warm-mix additive RAP-R affects the functional groups in warm-mix recycled asphalt. A newly identified transmittance peak at 3,295 cm−1, corresponding to the stretching vibration of free hydrogen bonds (–OH), was detected in the RAP-R binder but not in the RAP-C binder [118]. Furthermore, as illustrated in Figure 12b, this peak persisted even after both short-term and long-term aging, indicating that the rheological behavior of RAP-R mastics differs from that of other asphalt mastics under various aging conditions. While initial transmittance peaks between 1,000 cm−1 and 1,200 cm−1 were noticeable in the unaged RAP-R binder, these variations diminished with aging. In contrast, Figure 12c shows that the FTIR spectra of the RAP-M and RAP-C binders remained almost identical, indicating that the warm-mix additive M did not significantly alter the bond structure or cause recombination within the asphalt binder [118].

![Figure 12:

FTIR spectra of different WMA additives; a) warm-mix additive R, b) rheological behavior of RAP-R and c) the FTIR spectra of the RAP-M and RAP-C binders (adapted with permission from [118]).](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0187/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0187_fig_012.jpg)

FTIR spectra of different WMA additives; a) warm-mix additive R, b) rheological behavior of RAP-R and c) the FTIR spectra of the RAP-M and RAP-C binders (adapted with permission from [118]).

The FTIR peak identified at 3,295 cm−1 corresponds to the stretching vibration of free hydroxyl (–OH) groups, confirming that hydrogen bonding is induced by the warm-mix additive RAP-R (Xu et al., 2021). The persistence of this peak after both short- and long-term aging indicates a stable chemical modification of the binder that influences its macroscopic rheological behavior. Quantitatively, this modification led to an increase of approximately 11–14 % in the complex shear modulus (G*) at 60 °C and a reduction of approximately 8–10 % in viscosity at 135 °C relative to the control RAP-C binder. The performance-grade (PG) high-temperature limit improved from PG 64–22 to PG 70–22, reflecting enhanced rutting resistance without compromising workability. These changes suggest that the formation and stability of (–OH) bonds strengthen molecular interactions within the binder matrix, resulting in increased stiffness and improved temperature susceptibility, which is consistent with the observed rheological enhancement. Foaming technology in WMA production involves the controlled introduction of small quantities of water to the liquid asphalt binder throughout the mixture. This process leads to a temporary expansion in the binder volume, forming a foam structure at elevated temperatures, which facilitates the coating of aggregates at decreased mixing and compaction temperatures [119], 120]. The ability to increase the workability at lower temperatures makes foaming an efficient and widely adopted technique in asphalt pavement engineering. In addition to foaming technology, polyphosphoric acid (PPA) has gained attention as an economical substitute for polymer modifiers for asphalt modification. Its affordability and capacity to significantly increase binder stiffness in a controlled manner make it a preferred choice for pavement applications [121]. Asphalt binders modified with PPA demonstrate improved resistance to rutting in the early service life of pavements because of increased initial stiffness. Furthermore, PPA modifications contribute to enhanced low-temperature flow properties, potentially reducing susceptibility to fatigue and thermal cracking over time [122].

Furthermore, studies have shown that incorporating PPA, particularly in nonwaxy bitumen, significantly enhances the rheological behavior of asphalt binders at medium and high temperatures while exerting minimal influence on low-temperature performance [123]. Several studies have indicated that incorporating 1 % PPA by binder weight can lead to an increase in high-temperature performance of approximately 10 °C while also improving low-temperature performance by nearly 2 °C. This modification has been recognized as an effective approach for enhancing the thermal stability of asphalt binders [124]. Despite extensive research on WMA binders and PPA-modified binders as separate entities, few studies have explored the combined effects of PPA within WMA systems [117]. Understanding the rheological properties of WMA is crucial for optimizing its performance, as these properties directly influence workability, durability, and resistance to deformation. Technological advancements in WMA formulations have significantly improved viscosity and flexibility, positioning WMA as a viable and sustainable alternative to conventional asphalt. However, further research focusing on the interaction of additives and optimization of binder compositions remains essential to enhance long-term performance and ensure greater reliability in road construction applications.

8 Fracture properties

WMA represents a modern advancement in asphalt technology; reducing production and application temperatures offers several advantages, including lower energy consumption, reduced GHG, and improved working conditions by minimizing exposure to excessive heat and asphalt fumes [125]. While these environmental and occupational health benefits are well established, a comprehensive understanding of WMA’s fracture properties is essential to ensure its long-term durability and structural performance under diverse loading and environmental conditions [126]. Fracture characteristics, including fracture toughness, resistance to thermal and fatigue cracking, and vulnerability to moisture-induced damage, are determined by a range of factors, including binder type, choice of additives, production temperature, and aggregate gradation [127], 128]. The development of asphalt additives and mixture designs has significantly improved the mechanical properties of WMA, enabling it to achieve fracture resistance on par with conventional HMA. As a result, WMA has become a viable, sustainable, and structurally reliable alternative for modern road construction. Recent research underscores the advantages of combining RAP with WMA technologies, showing that this integration enhances both the compatibility and overall performance of asphalt mixtures [129]. Numerous studies have investigated the combined effects of high RAP content and WMA technologies, particularly focusing on sustainability benefits, such as energy reduction and increased recycling rates [130]. Research indicates that incorporating RAP into WMA mixtures helps mitigate additional aging of the reclaimed binder during production, thereby preserving its functional properties and extending the pavement lifespan [39]. The ability of WMA to reduce production temperatures plays a vital role in limiting the secondary aging of the RAP binder throughout the mixing and manufacturing processes. Additionally, the lower viscosity of WMA facilitates the incorporation of more RAP without compromising workability, improving the ease of placement and compaction [131]. This interaction between RAP and WMA presents a promising solution for developing environmentally sustainable pavements with performance characteristics comparable to those of conventional HMAs [5].

Many studies have explored the performance of RAP combined with various WMA additives via both laboratory tests and field assessments [21]. These investigations analyze the mechanical behavior of asphalt mixtures containing different RAP proportions and WMA technologies, focusing on key performance metrics such as cracking resistance, rutting susceptibility, and moisture durability. The findings suggest that combining RAP with WMA results in a synergistic effect, compensating for individual material limitations when used separately [126]. Further research has examined the impact of incorporating high RAP contents with different WMA additives, particularly with respect to the workability of asphalt mixtures. The results indicate that WMA technology significantly reduces the mixing and compaction temperatures, thereby increasing the workability. This improvement not only streamlines construction processes but also aligns with sustainability goals by reducing energy consumption and GHG emissions [85]. The combined application of RAP and WMA offers a strategic approach for optimizing material performance, minimizing environmental impact, and improving the durability and cost-effectiveness of asphalt pavements.

A study was conducted to evaluate the effects of varying RAP proportions (10 %, 30 %, and 50 %) in combination with WMA additives on the cracking resistance of asphalt mixtures under applied loads [121]. The results demonstrated that WMA additives enhanced the cracking resistance of modified mixtures compared with that of conventional HMA, as shown in Figure 13a [133]. However, an inverse correlation was observed between the RAP content and fatigue resistance, with reductions of 44 %, 74 %, and 89 % as the RAP content increased to 10 %, 30 %, and 50 %, respectively. Another study investigated the moisture susceptibility of asphalt mixtures containing RAP at concentrations ranging from 10 % to 50 % in conjunction with WMA additives and revealed that a higher RAP content improved moisture resistance (Figure 13b) [132]. Moreover, the combined effects of RAP and WMA on freeze‒thaw durability were assessed [134]. The results indicated that WMA-modified mixtures presented lower freeze‒thaw resistance than HMA did, indicating potential durability concerns in cold climates. Furthermore, an analysis of the high RAP content in WMA mixtures revealed its impact on rutting resistance [135]. The findings showed that increasing the RAP content in WMA mixtures enhanced the resistance to permanent deformation, with improvements ranging from 15 % to 40 %. However, while WMA mixtures benefit from higher RAP content in terms of load-associated cracking resistance, HMA mixtures exhibited the opposite trend, with increased RAP content reducing cracking resistance [135]. Recent research has increasingly focused on the fracture properties of asphalt mixtures incorporating both RAP and WMA additives [128], 136]. One study specifically examined the combined influence of RAP content and WMA technology on fracture resistance at intermediate temperatures. The findings suggested that higher RAP proportions led to a decline in fracture resistance, raising concerns about potential crack propagation in these mixtures [136]. Conversely, another study reported that incorporating 25 % RAP into WMA mixtures resulted in a fracture strength comparable to or exceeding that of HMA, indicating that optimizing the RAP and WMA compositions can help maintain the structural integrity of asphalt mixtures [125].

![Figure 13:

a) Force versus displacement curve and b) critical strain energy release rate (adapted with permission from [132]).](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0187/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0187_fig_013.jpg)

a) Force versus displacement curve and b) critical strain energy release rate (adapted with permission from [132]).

Studies have also demonstrated that, compared with HMA, incorporating 50 % RAP into WMA leads to a decrease in fracture strength [125]. This reduction is attributed primarily to increased brittleness, which negatively impacts both fracture resistance and fatigue resistance [137]. Another investigation analyzed the effects of different RAP contents in WMA mixtures produced with water-based foaming additives on fracture performance [30]. Using the semicircular bend (SCB) test, key fracture parameters, such as the cracking resistance index, fracture energy, and flexibility index, were evaluated. The results indicated that incorporating up to 50 % RAP improved the fracture strength; however, exceeding this limit negatively affected the fracture performance of the foam-based WMA mixtures. The integration of RAP, WMA additives, rejuvenators, and antistipping agents has become a widely adopted practice in asphalt pavement engineering. This comprehensive approach has led to extensive research on the interactions between WMA additives and RAP, particularly their effects on crucial performance indicators [138]. For example, one study examined the impact of different WMA additives on the workability of asphalt mixtures with varying RAP contents and revealed that WMA additives significantly improved the workability, facilitating better compaction and handling. Another study investigated the combined effects of recycling agents, WMA additives, and RAP on the cracking resistance of flexible pavements, highlighting the potential of these components to enhance overall pavement performance [129].

Experimental studies indicate that incorporating recycling agents and WMA additives can significantly improve the fracture toughness and energy absorption capacity of asphalt mixtures when subjected to various loading conditions at low temperatures. However, the inclusion of RAP has been observed to reduce these properties, highlighting a potential trade-off between the environmental benefits of RAP usage and the cracking resistance of asphalt mixtures [136]. Additional research on the mechanical behavior of WMA mixtures containing RAP underscores the pivotal role of the specific WMA additive in determining the overall performance of the mixture [104]. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that incorporating 50 % RAP into asphalt mixtures leads to substantial improvements in key mechanical properties, such as the flow number, resilient modulus, and resistance to moisture-related damage [129]. The results shown in Figure 14 provide a detailed summary of the direct and indirect tensile strengths of WMA mixtures, as documented by various researchers [34], 72], 83], 87], 91], 116], [139], [140], [141], [142], [143], [144], [145].

The deterioration of asphalt due to aging has a meaningful contribution to pavement durability and service life, making it a critical factor in pavement engineering [129]. To ensure long-lasting performance, it is essential to account for aging effects in the design phase. Research has shown that as asphalt mixtures age, their stiffness increases, but the extent of this change depends on the composition of the mixture [146]. Although higher stiffness may enhance the load-bearing capacity, excessive stiffening leads to brittleness, increasing susceptibility to fatigue, thermal, and block cracking. Experts suggest that integrating aging-related adjustments into the design phase can improve resistance to traffic loads and environmental stressors, thereby enhancing pavement performance [147]. Asphalt aging also weakens the durability of pavements, increasing their vulnerability to moisture infiltration and subsequent deterioration [129]. Over time, aged asphalt mixtures exhibit reduced resistance to abrasion and moisture-induced damage, which accelerates structural degradation [148]. While aging strengthens asphalt concrete by increasing its stiffness, it simultaneously reduces flexibility, compromising the integrity of the mixture and increasing the likelihood of fatigue and thermal cracking [129]. Addressing these aging-related challenges at the design stage is crucial for improving the lifespan and performance of flexible pavements. To assess the long-term behavior of asphalt mixtures, investigators often employ accelerated aging methods in laboratory settings, replicating in-service conditions and monitoring changes in mechanical properties over time [146]. These controlled assessments provide valuable insights into durability and aid in optimizing material formulations for enhanced pavement resilience. Although incorporating RAP and WMA supports sustainability in pavement construction, the mechanical behavior of these materials, particularly their fracture resistance at intermediate temperatures, requires careful examination. The combined use of WMA additives, RAP, and rejuvenators must be carefully balanced to maintain structural strength and ensure that pavement longevity is not compromised. The ability of WMA to resist cracking plays a crucial role in determining its structural reliability under diverse traffic loads and environmental conditions. Advances in material engineering and the development of innovative additives have strengthened WMA resistance to crack initiation and propagation. These improvements contribute to the construction of more durable and environmentally responsible pavements. However, further investigations are necessary to deepen the understanding of fracture mechanisms and refine performance-based mix design approaches. Enhancing these aspects will support the broader adoption of WMA in modern infrastructure while maintaining high standards of sustainability and long-term performance.

9 Sustainability and environmental benefits

WMA has emerged as a transformative advancement in asphalt production, offering a sustainable alternative to conventional HMA. In response to increasing environmental concerns and the need for energy-efficient infrastructure, WMA technology addresses key challenges associated with traditional asphalt production. The underlying mechanism of WMA relies on specialized additives or water-based foaming techniques that enhance asphalt workability at reduced temperatures. This innovation not only improves energy efficiency but also assists the combination of higher proportions of RAP and other reused materials, supporting circular economy principles in construction. Furthermore, lower production temperatures mitigate the effects of thermal aging, which helps preserve the integrity of asphalt binders, extends the pavement lifespan and reduces the frequency of maintenance interventions. Since its introduction, WMA has gained widespread adoption in sustainable road construction due to its multiple environmental and practical benefits. These include a lower carbon footprint, improved air quality, reduced consumption of natural resources, and increased safety for construction workers due to decreased exposure to high temperatures and emissions. The integration of WMA into modern infrastructure projects aligns with global sustainability goals and reflects a commitment to environmentally responsible construction practices. As industry continues to prioritize sustainability, WMA represents a crucial step toward more efficient and eco-friendly road development strategies.

It is reported that WMA can consistently reduce greenhouse-gas and particulate emissions relative to HMA; however, the magnitude and reliability of these gains depend less on nominal temperature reduction and more on two contingencies [149]: long-term field performance and the material system chosen to achieve WMA conditions. Cradle-to-grave assessments that include traffic and end-of-life effects indicate that the embedded burdens of certain WMA technologies (e.g., synthetic zeolites) can erode plant-energy savings, whereas integrating RAP emerges as a robust lever for impact reduction, with even modest RAP shares (15 %) lowering climate and endpoint damages on the order of 13–14 % [150]. Mechanical-environmental studies further show that when WMA is paired with RAP and appropriate recycling agents, mixtures can match or exceed the rutting, cracking, and moisture resistance of virgin counterparts while simultaneously curbing cost and CO2, though performance is highly sensitive to the chemistry of the recycling agent and the contribution of virgin binder, which dominates both cost and emissions [151]. Comparative LCAs focused on midpoint indicators also suggest that WMA’s environmental advantage collapses if durability penalties increase maintenance demands [152]. Taken together, the literature supports WMA as environmentally preferable when (i) durability is preserved or improved, (ii) RAP substitution is maximized within performance limits, and (iii) additives are selected for low upstream burden and compatibilization efficacy; aligning mix-design decisions with cradle-to-grave, uncertainty-aware LCA therefore remains essential to realize dependable sustainability gains [10].

The combination of a higher percentage of RAP in WMA is increasingly recognized as a promising advancement toward sustainability in the paving industry. However, several industry professionals argue that the absence of standardized guidelines for the processing, handling, and characterization of RAP presents a significant challenge. In addition, the Superpave mix design methodology has been criticized for its limited capacity to effectively accommodate high-RAP-content mixtures, thereby constraining the adoption of greater RAP proportions in WMA applications [153]. Another critical aspect to consider when evaluating the sustainability of WMA is the carbon footprint associated with its production and transportation. Some researchers contend that the overall environmental benefits of WMA may be offset by emissions generated during the transportation of additives, particularly when sourced from distant locations rather than local suppliers. This logistical factor could inadvertently increase CO2 emissions and diminish the anticipated positive environmental impact of WMA [4],154]. From an environmental standpoint, extensive research has been conducted on the LCA of WMA. These studies overwhelmingly highlight the significant reduction in environmental burdens associated with WMA compared with HMA. Specifically, WMA technology (Figure 15) [155] has been shown to lower emissions of air pollutants, decrease energy consumption, reduce reliance on fossil fuels, and mitigate global warming potential (GWP) and GHG emissions [4], 155]. The most notable environmental advantage of WMA production is its capacity to curb GHG emissions, which is directly proportional to the energy savings achieved. Research estimates indicate that WMA production can lead to energy savings ranging from 25 % to 50 %, which subsequently results in a decrease of approximately 4.1 kg–5.5 kg of CO2 equivalent emissions per ton of WMA produced [156]. In a broader context, if Germany’s entire asphalt production, amounting to 63 million tons annually, were converted to lower-temperature WMA, the resulting CO2 emissions would decrease by approximately 0.4 million tons per year, reflecting a potential 25 % reduction [157]. Similarly, studies conducted in Australia indicate that WMA contributes to lower plant emissions, although the extent of this reduction varies on the basis of factors such as plant conditions, fuel types, prevailing weather conditions, and the specific WMA technology employed [14]. Furthermore, research suggests that decreasing HMA production temperatures by 20 °C could lead to an approximately 44 % reduction in total CO2 emissions generated from both the fuel and asphalt used in the manufacturing process. Moreover, studies indicate that lowering the production temperature of HMA by 20 °C has the potential to reduce overall CO2 emissions by approximately 44 %. This reduction encompasses emissions originating from both fuel consumption and asphalt materials utilized in the manufacturing process [158].

![Figure 15:

Techniques for reducing fumes and enhancing energy efficiency in the asphalt paving process (adapted with permission from [155]).](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0187/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0187_fig_015.jpg)

Techniques for reducing fumes and enhancing energy efficiency in the asphalt paving process (adapted with permission from [155]).

The environmental benefits of WMA technology are substantial, particularly in terms of pollutant emissions, which are considerably lower than those associated with conventional HMA production [159]. A 2021 report by the NAPA highlighted that switching from HMA to WMA resulted in a reduction of approximately 0.16 million metric tons (MMT) of CO2 equivalent emissions annually [160]. Furthermore, this shift led to a 24 % decrease in air pollutants, a 10 % reduction in smog formation, and a 3 % lower GWP, demonstrating the positive impact of WMA on environmental sustainability [64]. From an environmental standpoint, WMA technology effectively reduces CO2 emissions by lowering production and application temperatures. This reduction in temperature directly enhances the compaction of asphalt mixtures and the workability, which in turn improves the paving efficiency. WMA functions as a compaction aid by reducing the mechanical effort required to achieve optimal density, leading to enhanced pavement performance [14]. Despite its environmental advantages, certain operational challenges may arise when WMA is used. Factors such as the screed angle of attack on the paver, the movement of material between paving equipment [80], and the potential for thermal segregation can be affected by temperature variations during placement. In some cases, inconsistent temperature differentials within the surface mix may lead to undesirable outcomes, potentially impacting the long-term performance of the pavement [34].

WMA presents several advantages over conventional HMA, particularly in its ability to achieve the desired density with less effort, even at significantly lower temperatures [16]. This increased ease of compaction is due primarily to the use of innovative technologies and specialized additives in WMA production, which effectively reduce the viscosity of the asphalt binder. This reduction allows for better workability and compaction of the mixture under cooler conditions. However, the operation and maintenance of asphalt plants specifically designed for WMA production require careful attention to mitigate potential operations [56]. A notable benefit of WMA is its capacity to incorporate high percentages of RAP without negatively impacting workability, offering an environmentally friendly and cost-effective alternative for paving applications [161]. Furthermore, WMA offers significant advantages in colder climates by minimizing the temperature disparity between the asphalt mixture and the ambient environment. This reduction in temperature differential enhances the efficiency of paving operations under low-temperature conditions, ensuring improved workability and compaction. Moreover, the moderate temperature contrast in WMA allows for more consistent paving performance in colder climates, reducing potential issues associated with rapid cooling during placement.